Abstract

Newcastle disease virus (NDV) can modulate cancer cell signaling pathway and induce apoptosis in cancer cells. Cancer cells increase their glycolysis rates to meet the energy demands for their survival and generate ATP as the primary energy source for cell growth and proliferation. Interfering the glycolysis pathway may be a valuable antitumor strategy. This study aimed to assess the effect of NDV on the glycolysis pathway in infected breast cancer cells. Oncolytic NDV attenuated AMHA1 strain was used in this study. AMJ13 and MCF7 breast cancer cell lines and a normal embryonic REF cell line were infected with NDV with different multiplicity of infections (moi) to determine the IC50 of NDV through MTT assay. Crystal violet staining was done to study the morphological changes. NDV apoptosis induction was assessed using AO/PI assay. NDV interference with the glycolysis pathway was examined through measuring hexokinase (HK) activity, pyruvate, and ATP concentrations, and pH levels in NDV infected and non-infected breast cancer cells and in normal embryonic cells. The results showed that NDV replicates efficiently in cancer cells and spare normal cells and induce morphological changes and apoptosis in breast cancer cells but not in normal cells. NDV infected cancer cells showed decreased in the HK activity, pyruvate and ATP concentrations, and acidity, which reflect a significant decrease in the glycolysis activity of the NDV infected tumor cells. No effects on the normal cells were observed. In conclusion, oncolytic NDV ability to reduce glycolysis pathway activity in cancer cells can be an exciting module to improve antitumor therapeutics.

Keywords: Warburg effect, Pyruvate, Virotherapy, Cancer metabolism, Oncolytics

Introduction

Newcastle disease virus (NDV) is belonging to the genus Avulavirus of the family Paramyxoviridae. Viruses from this family are enveloped, nonsegmented, negative-sense RNA viruses that cause the inflammation of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts in a wide variety of poultry species [28]. The virulent NDV strain still inducing outbreaks in different countries, including Iraq, leading to severe economic damages in the poultry industry [11]; yet, attenuated and lentogenic NDV has promising antitumor activity and excellent safety in laboratory animals [26]. The Iraqi NDV strain AMHA1 is an oncolytic virus that is attenuated strain isolated originally from an outbreak [7]. The NDV induces apoptosis in cancer cells through both intrinsic and extrinsic pathways [8], causing DNA fragmentation and FAS ligand expression [13]. Furthermore, AMHA1 NDV strain found to induce apoptosis in cancer cells in caspase-dependent and independent pathways [29]. Oncolytic NDV strain found to interfere with biological processes such as angiogenesis in cancer cells and reduce its expression [5, 6].

Breast cancer cells rely on fermentative glycolysis as the main source of energy [18]. Increased glycolysis is the primary source of energy in cancer cells for ATP generation through the Warburg effect [22]. Cancer cells mainly produce energy by increasing the rate of glycolysis by 200 times that in their normal cells of origin; the increment in glycolysis is followed by lactate fermentation in the cytosol of the cells even if oxygen is plentiful [2]. Cancer cells are highly proliferative relative to normal cells and thus require increased ATP to meet their metabolic demands [16]. Therefore, high energy demands characterize malignant cells [31]. It is found that Influenza virus-infected non-tumor permissive cells have substantial changes in glycolysis and general cell metabolism [17]. Thus, it is interesting to assess the effect of NDV infection on the cancer cell glycolysis pathway and its interference with the proliferation of breast cancer cells.

Materials and methods

NDV propagation

The Experimental Therapy Department provided NDV AMHA1 attenuated strain, Iraqi Center of Cancer and Medical Genetics Research (ICCMGR), Mustansiriyah University. A stock of attenuated NDV was propagated in embryonated chicken eggs (Al-Kindi Company, Baghdad, Iraq), harvested from allantoic fluid, and then purified from debris by centrifugation (at 3000 rpm and 4 °C for 30 min). NDV was quantified through the hemagglutination test, aliquoted, and stored at − 86 °C. Viral titers were determined through a 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) titration on Vero cells following the standard procedure [7].

Cell lines and cell culture

The Cell Bank Unit provided AMJ13 human breast cancer cell line, MCF7 human breast cancer cell line and normal REF cell line, Experimental Therapy Department, ICCMGR, Mustansiriyah University, Baghdad, Iraq. The cell lines were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (US Biological, USA) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Capricorn-Scientific, Germany) and 1% (v/v) penicillin–streptomycin (Capricorn-Scientific, Germany) under a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Exponentially growing cells were used for experiments [9].

MTT cytotoxicity assay

Human breast cancer AMJ13, MCF7, and normal REF cell lines were used. Cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 104 cells in a 96-well microplate and incubated at 37 °C for 72 h until monolayer confluence was achieved. Cytotoxicity was investigated through 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. The cells were exposed to a range of multiplicity of infections (MOI) of NDV (0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, 1.6, 3.2, 6.4, and 12.8). After 72 h of infection, MTT dye solution (2 mg/ml) was added to each well. The incubation was continued for three hours. A total of 100 μl of DMSO was added to each well and incubated for 15 min. The optical density was measured at 492 nm using a microplate reader. Cytotoxicity % was calculated using the following equation:

were ODcontrol is the mean optical density of untreated wells, and ODSample is the optical density of treated wells [12].

Morphological changes

To visualize cell morphology under inverted microscopy, 200 µl of the AMJ13, MCF7, and REF cell suspensions were seeded in 96-well microtitration plates at the density of 1 × 104 cells/ml. The cells were exposed to NDV MOI (2) and compared with the control (untreated cells). The medium was removed, and NDV was added. Then, the plates were stained with 50 µl of crystal violet and incubated at 37 °C for 15 min. The stain was removed through gentle washing with tap water. The cells were observed by using an inverted microscope (Leica Microsystems, Germany) under × 200 magnification and photographed by using a digital camera at four haphazardly selected cultured fields. The images were analyzed using the ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). Percentage (%) of cells stained by crystal violet were calculated, and statistical analysis was performed [3].

Apoptosis assessment (propidium iodide/acridine orange staining)

The propidium iodide/acridine orange (PI/AO) dual staining method was used to quantify the apoptotic death rates of the MCF7 and AMJ13 cell lines. The cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at the density of 7000 cells/well on the night prior to treatment. The cells were treated with NDV MOI (2) at 37 °C in an incubator at 72 h prior to PI/AO staining. Then, 1 ml of the cell suspension was used for conventional PI/AO staining, and 100 μl of the cell suspension was transferred to a 96-well plate for modified PI/AO staining. AO was used (10 μl AO + 1 ml PBS), and PI (10 μl PI + 1 ml PBS) was then added at a 1:1 ratio. A total of 50 μl of the AO/PI stain mixture was added to all of the wells of the 96-well plate. The plates were incubated for 30 s at room temperature. Then, the dye was discarded. PBS (100 μl) was added to all of the wells of the 96-well plate for washing and then discarded. Photographs were taken directly by using a fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems, Germany). Fluorescence intensity was measured using Image J version 1.47 software to count apoptotic cells [1].

Glycolysis pathway and products measurement

Treated and untreated cell samples were prepared. Glycolysis pathway efficiency was examined through measuring hexokinase (HK) activity using the colorimetric method. It was performed by using an HK activity assay kit (ElabScience, USA). Glycolysis products, pyruvate, and ATP were measured. Pyruvate measured using a pyruvate colorimetric method. It was conducted by using a pyruvate assay kit (ElabScience, USA). ATP was measured through a colorimetric method by using an ATP assay kit (ElabScience, USA).

pH measurements

The cell lines were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS and 1% (v/v) penicillin–streptomycin and incubated in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C overnight prior to treatment. Exponentially growing cells were used for experiments. Cancer cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 104 cells in a 96-well microplate and incubated at 37 °C for 72 h until monolayer confluence was achieved as observed under inverted microscopy. Cells were exposed to NDV (MOI 2) and then incubated at 37 °C for 72 h. The cell suspension was collected by thawing. The pH values of AMJ13, MCF7, and REF cell lines were measured by litmus papers and pH meter and compared with those of the control.

Statistical analysis

All results were presented as SD and mean ± SEM. A two-tailed t test was performed, and statistical analysis was conducted with Excel version 10, GraphPad Prism version 7 (USA), and Isobologram version 1. CompuSyn software was used to compare the difference between groups under different conditions. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

NDV induces significant killing rate in cancer cells

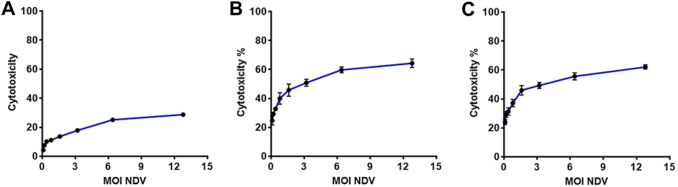

Cytotoxicity percentage was measured at different NDV treatment MOI (0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, 1.6, 3.2, 6.4, and 12.8 MOI) through the MTT cytotoxicity assay. Figure 1 showed that NDV induces significant cytotoxicity % in both cancer cell lines AMJ13 and MCF-7, while there was no significant killing in the normal embryonic cells.

Fig. 1.

NDV induced significant cytotoxicity in breast cancer cells but not in normal cells. a NDV cytotoxicity (CT %) in REF normal cells; b NDV CT % in AMJ13 cell line; c NDV CT % in MCF-7 cell-line

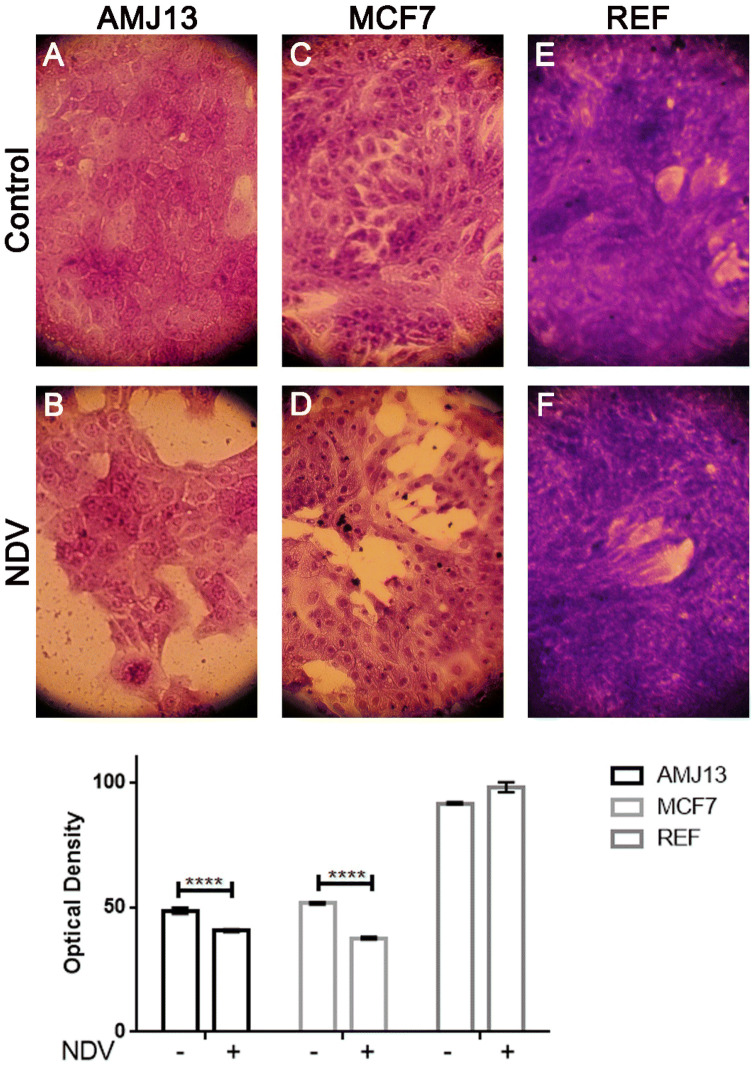

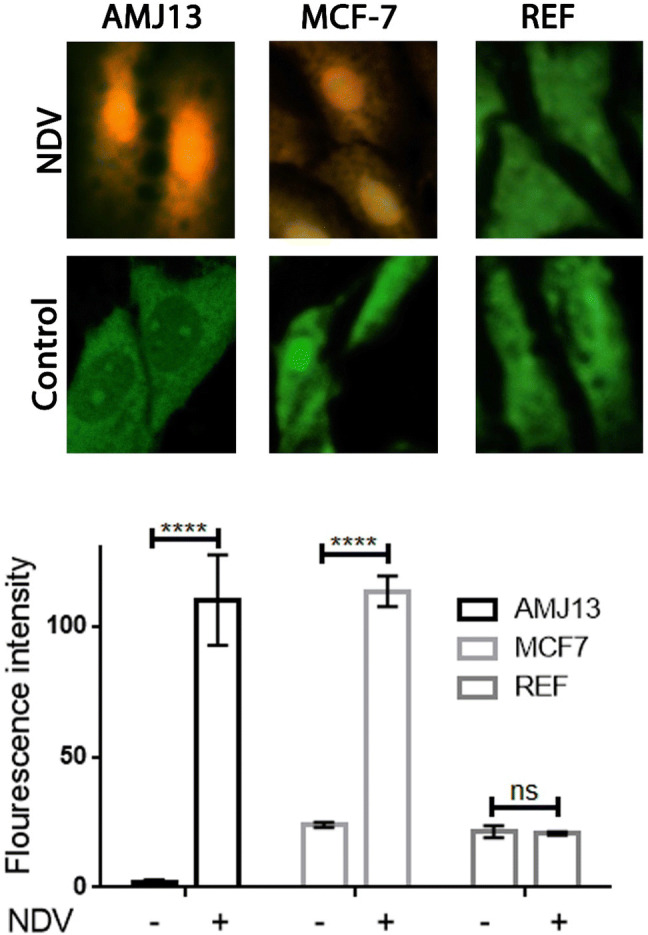

NDV induces morphological changes and apoptosis in the infected cancer cells

The morphological changes in the infected cancer cells within 72 h of treatment were attributed to the NDV induced cytopathic effect. Cell detachment and rounding were observed in the NDV infected cells only (Fig. 2). Quantitative image analysis showed that NDV infected cells have lower cell density, as shown in Fig. 2. AO/PI staining and imaging under fluorescence inverted microscope, showed untreated control cells appeared green, which indicate viable cells, whereas the NDV-treated cells appeared yellow or orange as apoptotic cells, (Fig. 3). In contrast to breast cancer cell lines, normal REF cell lines showed minimal morphological changes and apoptosis after NDV treatment. Quantitative image analysis of the fluorescence intensity revealed significant apoptosis induction by NDV treatment in cancer cells but not in normal cells (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Morphological changes in REF, AMJ13, and MCF7 cell lines treated with NDV for 72 h and stained with crystal violet, photographed under ×40 magnification (a–f). Morphological changes in REF, AMJ13, and MCF7 cell lines after treatment with NDV: untreated cells (control), treated cells with NDV. The quantitative image analysis revealed a significant decrease in treated cell density, which reflects the destructive effect induced by NDV infection, in which there was no decrease in the infected normal cells REF

Fig. 3.

All cells were stained with AO/PI and viewed under fluorescence microscopy at ×40 magnification to determine the NDV induction of apoptosis. Yellow-orange cells are representing apoptosis, and green cells are viable cells. Quantitative image analysis for fluorescence intensity revealed significant apoptosis induction in the NDV infected cells while there was no induction in normal REF cells

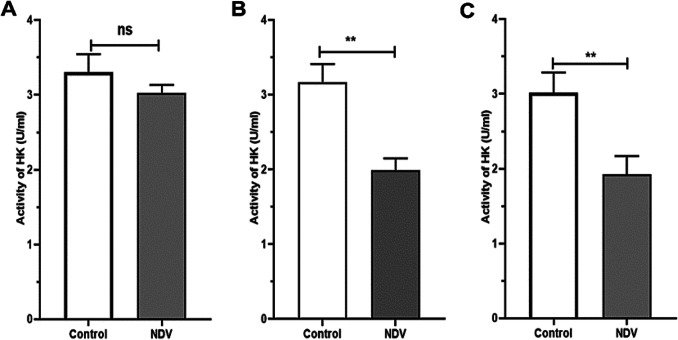

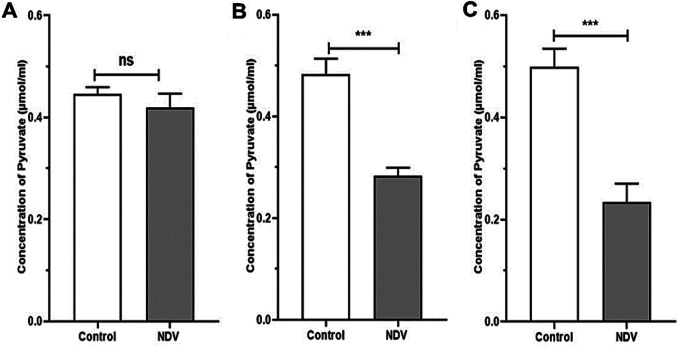

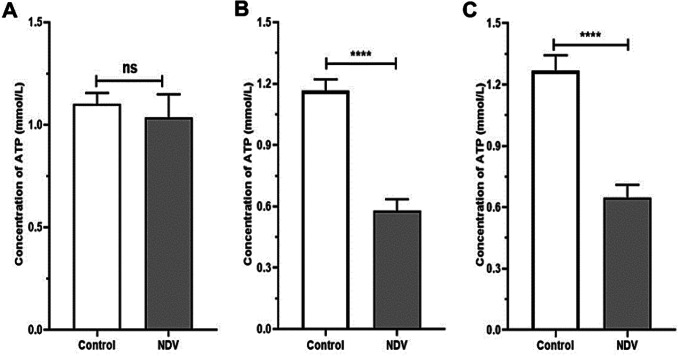

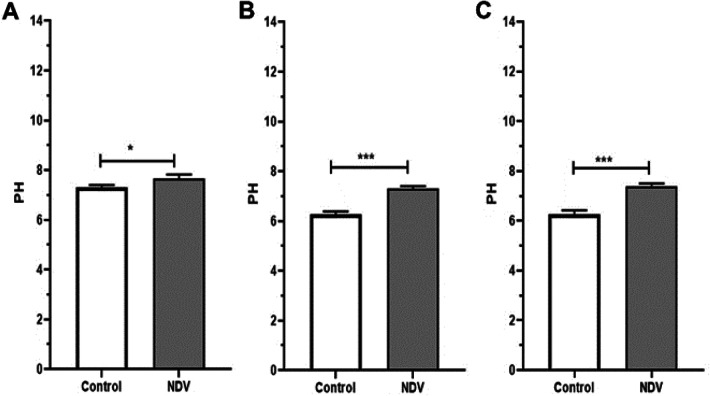

NDV interfere with glycolysis pathway and reduce glycolysis products

NDV treated cancer cells showed a reduction in HK activity. An insignificant reduction was found in the NDV infected normal REF cell line (Fig. 4). The pyruvate and ATP levels were decreased in cancer treated cells significantly when compared to the control untreated cancer cells. Normal embryonic REF cells pyruvate and ATP levels did not decrease significantly when infected with NDV (Figs. 5 and 6). The pH values of the AMJ13 and MCF7 cell lines increased after 72 h of treatment with NDV (MOI 2) because the reduction in lactate concentration attenuated the acidity. A significant difference was observed between NDV and control (Fig. 7). The pH value of the REF cell line non-significantly increased after treatment with NDV.

Fig. 4.

The effect of NDV on glycolysis inhibition. The activity of HK (U/ml) in REF, AMJ13, and MCF7 cell lines after NDV treatment with MOI 2 was compared with that of the control. a REF, b AMJ13, and c MCF7, at values represent the (mean ± SD) at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

Fig. 5.

Effect of NDV on pyruvate. REF, AMJ13 and MCF7 cell lines under NDV treatment (MOI 2) in comparison with that under the control at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001. a REF, b AMJ13, and c MCF7. Pyruvate μmol/ml

Fig. 6.

Effect of NDV on ATP production in REF, AMJ13, and MCF7 cell lines under treatment with NDV (MOI 2) compared with that in cell lines under the control treatment at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001. a REF, b AMJ13, and c MCF7. (ATP mmol/L)

Fig. 7.

Levels of acidity of NDV infected and non-infected cells, normal cells have neutral pH value in both infected and non-infected cells. Non-infected cancer cells showing a high level of acidity, but this situation reversed by NDV infection to show a rise to alkaloid levels. a pH values of the REF cell line, b pH values of the AMJ13 cell line and c pH values of the MCF7 cell line). Values represent the (mean ± SD) at t *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001

Discussion

The in vitro results of this study showed that increasing the MOI of NDV intensified the cytotoxicity and enhanced cytopathic and killing effect against breast cancer cell lines. Our findings are similar to several previously published works confirming that NDV oncolytic to the human breast cancer cells [10, 14, 25]. Exposing normal embryonic REF cells to NDV had no significant cytopathic and killing effect in our experiment, which proves safety that reported by others [4, 30]. The efficient replication and killing inside cancer cells and crippled replication with no killing effect in normal cells explained as selectivity.

The AO/PI apoptosis assay findings of the present work also confirmed that NDV induces apoptosis in cancer cell lines but not in normal cells. NDV triggers both apoptosis pathways in cancer cells [21], in recent work about AMHA1 NDV strain, it is found to induce apoptosis in caspase-dependent and independent pathways [29]. The HK activity in the NDV infection AMJ13 and MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines decreased relative to that in the uninfected control cells, while no changes in infected and non-infected REF cell lines, which again confirm the NDV oncolytics selectivity.

In the present study, we discovered that hexokinase activity reduced significantly after NDV infection. In a previous study by our group, we discovered another glycolytic enzyme is downregulated, which is glyceraldehyde3-phosphate (GAPDH) after cancer cell infection by NDV [10]. Deng et al. [20] conducted a proteomic analysis of chicken peripheral blood mononuclear cells after NDV infection; they found expression reduction of phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK), which suggests that NDV may decrease glycolytic pathway activity in the host. These findings together confirm that NDV negatively interferes with the glycolysis pathway.

To further confirm this negative regulation, we tested the glycolytic pathway products level in infected and non-infected cancer cells. The findings showed that NDV could cause ATP depletion, while insignificant relation was observed between NDV infection and normal REF cell lines. When glycolysis is inhibited, lactate production is completely terminated, and intracellular ATP concentration abruptly decreases [23]. Reduced pyruvate concentration was recorded as well, a significant difference between the effect of NDV and the control in breast cancer cell lines, and an insignificant difference in the REF cell line after treatment with NDV for 72 h was also observed. Pyruvate concentration depends on HK action in the glycolysis pathway [24]. Therefore, the ATP concentration of AMJ13 and MCF7 cell lines became deficient after NDV treatment relative to that of the control.

We found that the pH of breast cancer cell lines was higher than that of the control, and normal REF cell lines showed limited effects after 72 h of treatment with NDV. The reduction in acidity may be attributed to the decreased lactate concentration caused by the depleted pyruvate concentration [27]. Lactate deficiency reduces the acidity of the cell environment. This phenomenon is favorable for preventing the proliferation of cancer cells because tumors or cancer cells grow in acidic environments [19]. This phenomenon is consistent with the results of our study. This provided evidence confirm the decreased glycolysis in the NDV infected cancer cells compared with that in normal cells. Therefore, inhibition of the glycolysis process leads to a decrease in the growth and proliferation of affected cells as described by others [15].

In Conclusion, NDV exerted cytotoxicity, morphological changes, and apoptosis in cancer but not normal cells, which proves a selective oncolytic effect. NDV reduced glycolytic pathway activity by reducing HK activity, pyruvate, ATP, and tumor micro-environmental acidity in cancer but not normal cells, which again confirm the selective oncolytic effect that can be considered as one of therapeutic strategies for breast cancer and other types of cancer cells in the near future.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Experimental Therapy Department, Iraqi Center for Cancer and Medical genetic research, Mustansiriyah University, for their support.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors disclose no potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Abdullah SA, Al-Shammari AM, Lateef SA. Attenuated measles vaccine strain have potent oncolytic activity against Iraqi patient derived breast cancer cell line. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2020;27(3):865–872. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2019.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alfarouk KO, Verduzco D, Rauch C, Muddathir AK, Adil HH, Elhassan GO, et al. Glycolysis, tumor metabolism, cancer growth and dissemination. A new pH-based etiopathogenic perspective and therapeutic approach to an old cancer question. Oncoscience. 2014;1(12):777–802. doi: 10.18632/oncoscience.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alsaraf KM, Mohammad MH, Al-Shammari AM, Abbas IS. Selective cytotoxic effect of Plantago lanceolata L. against breast cancer cells. J Egypt Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;31(1):10. doi: 10.1186/s43046-019-0010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Shammari A, Yaseen N. In vitro synergistic enhancement of Newcastle disease virus to methotrexate cytotoxicity against tumor cells. Al-Anbar J Vet Sci. 2012;5(2):102–109. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines4010003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.AL-Shammari AM, Al-Hilli ZA, Yaseen NY. Molecular microarray study for the anti-angiogenic effect of Newcastle disease virus on Glioblastoma tumor cells. In: Third international scientific conference on nanotechnology, advanced material and their applications. Baghdad: University of Technology; 2011. p. 109–18.

- 6.Al-Shammari AM, Al-Hili ZA, Yaseen NY. 647. Iraqi Newcastle disease virus virulent strain as cancer antiangiogenic agent. Mol Ther. 2013;21:1. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Shammari AM, Al-Nassrawei HA, Kadhim AMA. Isolation and sero-diagnosis of Newcastle disease virus infection in human and chicken poultry flocks in three cities of middle Euphrates. Kufa J Vet Sci. 2014;5(1):16–21. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Shammari AM, Humadi TJ, Al-Taee EH, Al-Atabi SM, Yaseen NY. 439. Oncolytic Newcastle disease virus Iraqi virulent strain induce apoptosis in vitro through intrinsic pathway and association of both intrinsic and extrinsic pathways in vivo. Mol Ther. 2015;23:S173–S174. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(16)34048-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Shammari AM, Alshami MA, Umran MA, Almukhtar AA, Yaseen NY, Raad K, et al. Establishment and characterization of a receptor-negative, hormone-nonresponsive breast cancer cell line from an Iraqi patient. Breast Cancer Targets Ther. 2015;7:223–230. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S74509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Shammari AM, Abdullah AH, Allami ZM, Yaseen NY. 2-Deoxyglucose and Newcastle disease virus synergize to kill breast cancer cells by inhibition of glycolysis pathway through glyceraldehyde3-phosphate downregulation. Front Mol Biosci. 2019;6:90. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2019.00090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Shammari AM, Hamad MA, AL-Mudhafar MA, Raad K, Ahmed A. Clinical, molecular and cytopathological characterization of a Newcastle disease virus from an outbreak in Baghdad, Iraq. Vet Med Sci. 2020;4:5. doi: 10.1002/vms3.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Shammari AM, Al-Saadi H, Al-Shammari SM, Jabir MS. Galangin enhances gold nanoparticles as anti-tumor agents against ovarian cancer cells. AIP Conf Proc. 2020;2213(1):020206. doi: 10.1063/5.0000162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Shammary AM, Hassani HH, Ibrahim UA. Newcastle disease virus (NDV) Iraqi strain AD2141 induces DNA damage and FasL in cancer cell lines. J Biol Life Sci. 2014;5(1):1–11. doi: 10.5296/jbls.v5i1.4081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amin ZM, Ani MAC, Tan SW, Yeap SK, Alitheen NB, Najmuddin SUFS, et al. Evaluation of a recombinant newcastle disease virus expressing human IL12 against human breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):13999. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-50222-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arora R, Schmitt D, Karanam B, Tan M, Yates C, Dean-Colomb W. Inhibition of the Warburg effect with a natural compound reveals a novel measurement for determining the metastatic potential of breast cancers. Oncotarget. 2015;6(2):662–678. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cairns RA, Harris IS, Mak TW. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(2):85. doi: 10.1038/nrc2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng M-L, Chien K-Y, Lai C-H, Li G-J, Lin J-F, Ho H-Y. Metabolic reprogramming of host cells in response to enteroviral infection. Cells. 2020;9(2):473. doi: 10.3390/cells9020473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ciavardelli D, Rossi C, Barcaroli D, Volpe S, Consalvo A, Zucchelli M, et al. Breast cancer stem cells rely on fermentative glycolysis and are sensitive to 2-deoxyglucose treatment. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5(7):e1336. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corbet C, Feron O. Tumour acidosis: from the passenger to the driver’s seat. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17(10):577–593. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deng X, Cong Y, Yin R, Yang G, Ding C, Yu S, et al. Proteomic analysis of chicken peripheral blood mononuclear cells after infection by Newcastle disease virus. J Vet Sci. 2014;15(4):511–517. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2014.15.4.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elankumaran S, Rockemann D, Samal SK. Newcastle disease virus exerts oncolysis by both intrinsic and extrinsic caspase-dependent pathways of cell death. J Virol. 2006;80(15):7522–7534. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00241-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gill KS, Fernandes P, O’Donovan TR, McKenna SL, Doddakula KK, Power DG, et al. Glycolysis inhibition as a cancer treatment and its role in an anti-tumour immune response. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1866(1):87–105. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gonin-Giraud S, Mathieu AL, Diocou S, Tomkowiak M, Delorme G, Marvel J. Decreased glycolytic metabolism contributes to but is not the inducer of apoptosis following IL-3-starvation. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9(10):1147–1157. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gray LR, Tompkins SC, Taylor EB. Regulation of pyruvate metabolism and human disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71(14):2577–2604. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1539-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hartkopf AD, Fehm T, Wallwiener D, Lauer UM. Oncolytic virotherapy of breast cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;123(1):164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hassan SA, Allawe AB, Al-Shammari AM. In vitro oncolytic activity of non-virulent Newcastle disease virus LaSota strain against mouse mammary adenocarcinoma. Iraq J Sci. 2020;61(2):285–294. doi: 10.24996/ijs.2020.61.2.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ippolito L, Morandi A, Giannoni E, Chiarugi P. Lactate: a metabolic driver in the tumour landscape. Trends Biochem Sci. 2019;44(2):153–166. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2018.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mayo MA. A summary of taxonomic changes recently approved by ICTV. Arch Virol. 2002;147(8):1655–1656. doi: 10.1007/s007050200039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohammed MS, Al-Taee MF, Al-Shammari A. Caspase dependent and independent anti-hematological malignancy activity of AMHA1 attenuated newcastle disease virus. Int J Mol Med. 2019;8(3):211–222. doi: 10.22088/ijmcm.bums.8.3.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schirrmacher V. Fifty years of clinical application of Newcastle disease virus: time to celebrate! Biomedicines. 2016;4(3):16. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines4030016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324(5930):1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]