Abstract

Background

Intensive lifestyle interventions (LI) improve outcomes in obesity and type 2 diabetes but are not currently available in usual care.

Objective

To compare the effectiveness and costs of two group LI programs, in-person LI and telephone conference call (telephone LI), to medical nutrition therapy (MNT) on weight loss in primary care patients with type 2 diabetes.

Design

A randomized, assessor-blinded, practice-based clinical trial in three community health centers and one hospital-based practice affiliated with a single health system.

Participants

A total of 208 primary care patients with type 2 diabetes, HbA1c 6.5 to < 11.5, and BMI > 25 kg/m2 (> 23 kg/m2 in Asians).

Interventions

Dietitian-delivered in-person or telephone group LI programs with medication management or MNT referral.

Main Measures

Primary outcome: mean percent weight change. Secondary outcomes: 5% and 10% weight loss, change in HbA1c, and cost per kilogram lost.

Key Results

Participants’ mean age was 62 (SD 10) years, 45% were male, and 77% were White, with BMI 35 (SD 5) kg/m2 and HbA1c 7.7 (SD 1.2). Seventy were assigned to in-person LI, 72 to telephone LI, and 69 to MNT. The mean percent weight loss (95% CI) at 6 and 12 months was 5.6% (4.4–6.8%) and 4.6% (3.1–6.1%) for in-person LI, 4.6% (3.3–6.0%) and 4.8% (3.3–6.2%) for telephone LI, and 1.1% (0.2–2.0%) and 2.0% (0.9–3.0%) for MNT, with statistically significant differences between each LI arm and MNT (P < 0.001) but not between LI arms (P = 0.63). HbA1c improved in all participants. Compared with MNT, the incremental cost per kilogram lost was $789 for in-person LI and $1223 for telephone LI.

Conclusions

In-person LI or telephone group LI can achieve good weight loss outcomes in primary care type 2 diabetes patients at a reasonable cost.

Clinical Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02320253

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-019-05629-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: type 2 diabetes, lifestyle intervention, primary care, cost-effectiveness, weight loss interventions

INTRODUCTION

Intensive, multicomponent behavioral interventions for type 2 diabetes and obesity, also known as lifestyle interventions (LI), improve myriad patient health outcomes.1, 2 The US Preventive Services Task Force Grade B recommendation states that lifestyle interventions should be widely available,3 yet they are not routinely offered in usual care. A recent editorial observed that “A critical priority…is how to promote the implementation and dissemination of evidence-based obesity interventions”.4 The challenge of translation research is to ensure that evidence-based interventions are practical and effective when implemented in clinical practice.

The goal of the REAL HEALTH-Diabetes trial was to adapt the evidence-based LI used in the Look AHEAD trial and the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP), which demonstrated weight losses of 5–10% and numerous other health benefits,5–7 into community health center primary care practices with high diabetes and obesity prevalence to determine its effectiveness and cost-effectiveness in usual care settings. In REAL HEALTH-Diabetes, two group LI modalities, delivered in-person or by telephone conference call, were compared with referral to a registered dietitian for individual medical nutrition therapy (MNT), the current recommended standard of care. We hypothesized that the in-person LI and telephone LI arms would have greater percent weight loss than MNT at 6 months with more sustained weight loss at 12 months. Additionally, we evaluated 1-year diabetes-specific cost-effectiveness from a health system perspective.

METHODS

Trial Design

Details of the study design, intervention, and participant characteristics have been previously reported.8 Briefly, REAL HEALTH-Diabetes is a practice-based, three-arm, randomized trial with 1:1:1 allocation. The trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02320253) and was approved by the Partners HealthCare IRB. All participants gave written, informed consent before any study procedures were performed.

Setting

The trial was conducted primarily at three community health centers and one diabetes specialty practice affiliated with Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). Recruitment was expanded to the entire MGH-affiliated primary care network and three endocrinology practices located near the community health centers.9

Similar to the Look AHEAD trial, eligible participants were adults with type 2 diabetes, BMI > 25 kg/m2 (> 23 kg/m2 if Asian ancestry) but ≤ 159 kg (350 lbs.), HbA1c 6.5 to < 11.5%, systolic/diastolic blood pressure < 160/100 mmHg, willingness to lose 5–7% of body weight, and ability to communicate in English or Spanish. Participants were required to complete a 5–7-day food diary to demonstrate readiness to enroll in an LI program. Exclusion criteria included planned pregnancy, current participation in a weight loss program or MNT, weight change of > 3% in the previous month, previous or planned bariatric surgery, long-term use of medications likely to impact weight (e.g., corticosteroids, atypical antipsychotics), or medical or psychiatric conditions that would interfere with participation in the intervention.

Intervention

The LI was delivered by registered dietitians.8 The adapted program was a 37-session LI with identical content in in-person LI and telephone LI arms. In-person LI took place at clinics during the workday or on weekday evenings. This report includes the first year, which provided a maximum of 25 (14 weekly, then 5 bi-weekly, then 6 monthly) 60–90-min group sessions and up to 3 optional individual sessions. The major adaptations from Look AHEAD were (1) to deliver the content in groups, with very limited individual sessions and (2) one arm delivered entirely by telephone conference call. Content was a curated hybrid of key publicly available English and Spanish DPP and Look AHEAD session materials (Appendix Table 1) minimally modified for delivery in groups of 4–12 participants with decreasing intensity over 2 years. Treatment fidelity was ensured via use of process and content guidelines and direct observation and supervision.

Sample meal replacements (shakes, bars, and prepackaged entrees) were introduced in week 3, and participants were encouraged to purchase and use them to replace 1 to 2 meals per day. Meal replacement use was not formally tracked. Participants were asked to keep diaries of self-monitored glucose levels, food intake, physical activity minutes, and doses of diabetes medications for dietitian review at each session. If hypo- or hyperglycemia criteria were met on dietitian review, the study provider reviewed glucose diaries to adjust diabetes medications and update the electronic health record and primary care provider (PCP) as needed for safety per Look AHEAD protocol.8, 10

MNT participants were referred to a dietitian at their health center or preferred location and were counseled regarding MNT’s proven effectiveness for weight loss and improved diabetes control. As part of the informed consent, all participants were informed that MNT sessions would be billed per usual health insurance coverage. Initial MNT sessions were 45–60 min and follow-up sessions were 15–45 min. The number of MNT visits was determined after the initial visit by the dietitian and the participant as per usual care.

Data and Outcome Measurements

Data and outcome measurements were collected during research visits at baseline, 6, and 12 months by assessor-blinded research assistants. Socioeconomic variables, comorbidities, and medications were obtained by self-report and confirmed by electronic health record review. Trained study staff measured weight, height, and blood pressure. Medication adherence was captured with the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8).11, 12

The primary outcome was percent weight change from baseline, measured on clinically calibrated scales in light clothing. Participants were instructed to fast prior to weighing. To facilitate comparisons with the Look AHEAD trial which reported 12-month outcomes,13 secondary clinical outcomes included changes in other variables at 6 and 12 months compared with baseline, including clinically significant thresholds of 5 and 10% weight loss, HbA1c, medication use, blood pressure, and fasting lipid profiles. Phlebotomy was performed using local clinic procedures with samples processed by the MGH clinical laboratory. In the case of missing data, clinical weight and laboratory data available within a 6-month window of the study visit were used.

We pre-specified that the cost-effectiveness analysis would evaluate short-term costs and health effects relevant to payors to inform the design of payment contracts aligning financial incentives to promote adoption of effective and efficient diabetes care.14 Therefore, the cost analysis focused on diabetes-specific health system costs, specifically the cost of delivering LI or MNT, as well as diabetes medication costs, since these medications are most significantly affected by LI.15 The cost-effectiveness analysis reports the incremental cost per kilogram weight loss, percent weight loss, and additional person with 5% weight loss for each cross-arm comparison. Probabilistic sensitivity analyses used Monte Carlo methods to incorporate the uncertainty in each cost and effectiveness parameter into the uncertainty of the overall cost and cost-effectiveness estimates. Detailed cost-effectiveness analysis methods are described in the Online Supplementary Section.

Session Attendance

Completers were defined as participants who had attended ≥ 70% of LI sessions (≥ 14 sessions by months 6 and ≥ 18 by month 12). MNT utilization was tracked via patient report and the electronic health record.

Sample Size

We powered the study to detect a between-group difference in weight loss of 3.5% of body weight, assuming standard deviation of 5.5. Using the conservative Bonferroni method to adjust for 3-arm multiple comparisons, reducing the nominal two-sided significance level to 0.0167 (0.05/3), REAL HEALTH-Diabetes required 54 subjects per arm to detect a difference with 80% power. Preliminary data indicated the correlation of patients within the same LI group was rarely higher than an intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.01. Therefore, we used a conservative ICC estimate of 0.02 in sample size planning. Allowing for a 10% drop-out rate yielded a final planned sample size of 210, or 70 per arm.

A computer randomization scheme stratified by sex in randomly alternating blocks of 3 and 6 with 1:1:1 ratio within each intervention site was used to promote balance across study arms.8

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were intention-to-treat. We used three-level mixed effect models with two random effects (individual participant and intervention delivery group) to account for the time-within-participant and participants-within-group data structure. We compared change in outcomes over time between the three study arms with significance level set at a two-sided P value ≤ 0.0167.

Our pre-specified primary outcome was percent weight change. We did not attempt any imputation since the number of participants with primary outcome missing was less than 2%. We reported the overall P values combining 6-month and 12-month data since the results from 6- and 12-month results are similar. The individual P values for 6-month and 12-month analyses are presented in Appendix Table 2.

The analysis plan specified the repeated measures at two discrete time points with windows for data collection around each time point. As a sensitivity analysis, we explored using the exact number of days from enrollment at time of measurement as a continuous variable and estimated the responses at months 6 and 12. We also performed sensitivity analyses limited to research data only (excluding data obtained from clinical care), and data within a narrower visit window only (excluding data collected outside of a 2-month window of target follow-up date). We conducted subgroup analyses limited to completers. We also explored models including baseline measurements as an outcome which allowed us to include the few participants who did not have follow-up measurements in the analysis.

RESULTS

Participants

Participants were recruited between January 2015 and July 2017 (Fig. 1). Of 417 who were eligible by telephone screen including 248 who attended an in-person screening visit, 211 were enrolled and randomly assigned to MNT (n = 69), in-person LI (n = 70), and telephone LI (n = 72). Three MNT participants withdrew consent yielding the final study population of 208.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram.

Baseline Characteristics

Baseline characteristics are reported in Table 1. The average age of participants was 62 years; 45% were male; and 77% were non-Hispanic White, 13.5% Hispanic, 4.3% non-Hispanic Black, and 3.4% Asian. Most participants had well-controlled hypertension and hyperlipidemia; 22% had coronary artery disease. The mean BMI was 35 kg/m2 with mean HbA1c of 7.7%. Approximately one-fourth of the cohort was treated with metformin alone. Thirty-one percent of the cohort was treated with sulfonylurea and 33% with insulin.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| All | MNT | In-person LI | Telephone LI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 208 | 66 | 70 | 72 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 61.7 (10.2) | 61.4 (10.7) | 61.3 (10.3) | 62.4 (9.8) |

| Male gender, n (%) | 93 (44.7) | 29 (43.9) | 33 (47.1) | 31 (43.1) |

| Race and ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 160 (76.9) | 47 (71.2) | 55 (78.6) | 58 (80.6) |

| Hispanic | 28 (13.5) | 11 (16.7) | 10 (14.3) | 7 (9.7) |

| Non-Hispanic Black or African American | 9 (4.3) | 5 (7.6) | 2 (2.9) | 2 (2.8) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 7 (3.4) | 2 (3.0) | 3 (4.3) | 2 (2.8) |

| Other | 4 (1.9) | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.2) |

| Primary language: Spanish, n (%) | 17 (8.2) | 6 (9.1) | 5 (7.1) | 6 (8.3) |

| Intervention participation at community health center, n (%) | 128 (61.5) | 42 (63.6) | 42 (60.0) | 44 (61.1) |

| Educational attainment, n (%) | ||||

| Less than 12th grade | 17 (8.2) | 8 (12.1) | 5 (7.1) | 4 (5.6) |

| 12th grade or GED | 43 (20.7) | 12 (18.2) | 13 (18.6) | 18 (25.0) |

| 1–3 years of college | 60 (28.8) | 18 (27.3) | 20 (28.6) | 22 (30.6) |

| 4 or more years of graduate school | 88 (42.3) | 28 (42.4) | 32 (45.7) | 28 (38.9) |

| Employment status, n (%) | ||||

| Employed | 110 (52.9) | 35 (53.0) | 39 (55.7) | 36 (50.0) |

| Unemployed | 11 (5.3) | 5 (7.6) | 3 (4.3) | 3 (4.2) |

| Homemaker | 7 (3.4) | 2 (3.0) | 2 (2.9) | 3 (4.2) |

| Retired | 73 (35.1) | 22 (33.3) | 23 (32.9) | 28 (38.9) |

| Other | 7 (3.4) | 2 (3.0) | 3 (4.3) | 2 (2.8) |

| Annual household income, n (%) | ||||

| Less than $30,000 | 48 (23.1) | 17 (25.8) | 17 (24.3) | 14 (19.4) |

| $30,000–$49,999 | 21 (10.1) | 3 (4.5) | 9 (12.9) | 9 (12.5) |

| $50,000–$99,999 | 68 (32.7) | 17 (25.8) | 23 (32.9) | 28 (38.9) |

| $100,000–$150,000 | 35 (16.8) | 14 (21.2) | 11 (15.7) | 10 (13.9) |

| > $150,000 | 27 (13.0) | 12 (18.2) | 6 (8.6) | 9 (12.5) |

| Missing | 9 (4.3) | 3 (4.5) | 4 (5.7) | 2 (2.8) |

| Insurance, n (%) | ||||

| Commercial | 88 (42.3) | 30 (45.5) | 24 (34.3) | 34 (47.2) |

| Dual Medicare and Medicaid | 26 (12.5) | 10 (15.2) | 8 (11.4) | 8 (11.1) |

| Medicaid | 29 (13.9) | 9 (13.6) | 13 (18.6) | 7 (9.7) |

| Medicare | 59 (28.4) | 14 (21.2) | 23 (32.9) | 22 (30.6) |

| Self-pay | 6 (2.9) | 3 (4.5) | 2 (2.9) | 1 (1.4) |

| Diabetes duration (years), mean (SD) | 10.2 (8.0) | 10.3 (8.0) | 10.6 (7.4) | 9.8 (8.7) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 164 (78.8) | 51 (77.3) | 59 (84.3) | 54 (75.0) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 163 (79.1) | 48 (75.0) | 56 (80.0) | 59 (81.9) |

| Retinopathy | 15 (7.2) | 7 (10.6) | 4 (5.7) | 4 (5.6) |

| Neuropathy | 34 (16.6) | 12 (18.2) | 13 (19.4) | 9 (12.5) |

| Proteinuria | 24 (11.7) | 8 (12.1) | 9 (13.0) | 7 (10.0) |

| Coronary artery disease | 46 (22.1) | 15 (22.7) | 15 (21.4) | 16 (22.2) |

| Congestive heart failure | 9 (4.3) | 4 (6.1) | 1 (1.4) | 4 (5.6) |

| Physical measurements and laboratory results, mean (SD) | ||||

| Weight (kg) | 98.1 (18.9) | 99.7 (21.4) | 98.8 (17.0) | 96.1 (18.2) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 35.0 (5.4) | 35.7 (6.2) | 35.0 (4.9) | 34.5 (5.0) |

| HbA1c | 7.7 (1.2) | 7.8 (1.2) | 7.8 (1.2) | 7.6 (1.1) |

| HbA1c category, n (%) | ||||

| < 7 | 53 (25.5) | 16 (24.2) | 19 (27.1) | 18 (25.0) |

| 7–7.9 | 88 (42.3) | 28 (42.4) | 25 (35.7) | 35 (48.6) |

| 8–8.9 | 35 (16.8) | 8 (12.1) | 15 (21.4) | 12 (16.7) |

| ≥ 9 | 32 (15.4) | 14 (21.2) | 11 (15.7) | 7 (9.7) |

| Blood pressure, mean (SD) | ||||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 124.9 (13.7) | 125.1 (16.5) | 126.0 (13.9) | 123.6 (10.5) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 76.7 (8.3) | 75.8 (10.2) | 76.6 (7.2) | 77.5 (7.5) |

| Lipid panel, mean (SD) | ||||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 163.3 (38.1) | 162.2 (37.6) | 164.7 (37.6) | 162.8 (39.5) |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 165.3 (186.1) | 146.4 (99.2) | 196.5 (289.9) | 152.2 (94.0) |

| HDL (mg/dl) | 43.9 (11.7) | 45.3 (12.6) | 42.7 (10.2) | 43.7 (12.1) |

| LDL (mg/dl) | 88.8 (30.2) | 87.5 (29.7) | 90.4 (31.3) | 88.3 (30.1) |

| Medication, n (%) | ||||

| Glucose-lowering medication | ||||

| Metformin alone | 50 (24.0) | 16 (24.2) | 14 (20.0) | 20 (27.8) |

| Metformin plus other | 116 (55.8) | 36 (54.5) | 43 (61.4) | 37 (51.4) |

| Sulfonylurea | 65 (31.3) | 19 (28.8) | 27 (38.6) | 19 (26.4) |

| GLP-1 receptor agonist | 14 (6.7) | 5 (7.6) | 5 (7.1) | 4 (5.6) |

| SGLT2 inhibitor | 6 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.3) | 3 (4.2) |

| Insulin | 69 (33.2) | 20 (30.3) | 25 (35.7) | 24 (33.3) |

| Alpha-glucosidase inhibitor | 2 (1.0) | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.4) |

| Pioglitazone | 2 (1.0) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| DPP4 inhibitor | 9 (4.3) | 1 (1.5) | 4 (5.7) | 4 (5.6) |

| No glucose-lowering medication | 17 (8.2) | 8 (12.1) | 3 (4.3) | 6 (8.3) |

| Medication for hypertension or hyperlipidemia | ||||

| Blood pressure medication | 174 (83.7) | 53 (80.3) | 59 (84.3) | 62 (86.1) |

| Lipid-lowering medication | 165 (79.3) | 51 (77.3) | 55 (78.6) | 59 (81.9) |

| Statin | 156 (75.0) | 51 (77.3) | 47 (67.1) | 58 (80.6) |

| Medication adherence, mean (SD) | ||||

| Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS)* | 6.6 (1.6) | 6.5 (1.8) | 6.6 (1.3) | 6.7 (1.7) |

MNT medical nutrition therapy compared to in-person lifestyle intervention and telephone conference call lifestyle intervention, MMAS scores of 8, 6, to < 8, and < 6 indicate high, medium, and low adherence, respectively

Session Attendance

In the MNT arm, 83% attended at least one dietitian visit, with a mean of 3.6 (SD 3.3) visits at 12 months; 43.9% completed 4 or more MNT visits, the recommended standard of care, at 12 months. In the in-person LI arm, 99% attended at least one session, with mean 18.0 (SD 6.0) sessions; 66% attended 70% of sessions at 12 months (completers). In the telephone LI arm, 100% participated in at least one session, with mean 18.5 (SD 6.6) sessions; 72% were completers (Appendix Table 4).

Analyses of the Primary Outcome

Percent weight change (95% CI), showed 6-month weight loss of 1.1% (0.2–2.0%) in MNT, 5.6% (4.4–6.8%) in in-person LI, and 4.6% (3.3–6.0%) in telephone LI. The twelve-month weight loss was 2.0% (0.9–3.0%) in MNT, 4.6% (3.1–6.1%) in in-person LI, and 4.8% (3.3–6.2%) in telephone LI. At 12 months, 22% of MNT, 49% of in-person LI, and 44% of telephone LI achieved ≥ 5% weight loss and 3% of MNT, 18% of in-person LI, and 17% of telephone LI achieved ≥ 10% weight loss. Differences between each LI modality and MNT were statistically significant, but there was no difference between in-person and telephone LI (Table 2, Fig. 2, and Appendix Table 2). Sensitivity analyses restricted to participants with research data only or those obtained within 2 months of target follow-up date showed similar results (data not shown). Completers had higher mean weight loss than non-completers in both in-person and telephone LI arms (Appendix Table 5). When time-to-weight measurement was considered as a continuous variable, we observed a slightly smaller intervention effect at 6 months but a slightly larger intervention effect at 12 months. Including baseline measurements as an outcome had almost no impact on the effect estimates (data not shown).

Table 2.

Six- and 12-Month Outcomes of Referral to Medical Nutrition Therapy, In-Person Lifestyle Intervention, or Telephone Lifestyle Intervention

| 6-month follow-up | 12-month follow-up | Overall P value* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MNT | In-person LI | Telephone LI | MNT | In-person LI | Telephone LI | In-person LI vs. MNT | Telephone LI vs. MNT | In-person vs. telephone LI | |

| N | 66 | 69 | 72 | 64 | 69 | 70 | |||

| Weight, kg, mean (SD) | 98.5 (21.0) | 93.3 (16.8) | 91.6 (18.0) | 97.7 (18.0) | 94.4 (17.5) | 91.7 (18.9) | 0.19 | 0.046 | 0.50 |

| Weight change from baseline, %, mean (SD) | − 1.1 (3.7) | − 5.6 (4.9) | − 4.6 (5.8) | − 2.0 (4.1) | − 4.6 (6.1) | − 4.8 (6.1) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.63 |

| Weight change, kg, mean (SD) | − 1.2 (3.7) | − 5.6 (4.9) | − 4.6 (6.0) | − 2.1 (4.7) | − 4.5 (5.5) | − 4.6 (6.3) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.59 |

| Weight loss, ≥ 5%, n (%) | 10 (15.2) | 34 (49.3) | 32 (44.4) | 14 (21.9) | 33 (48.5) | 31 (43.7) | < 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.54 |

| Weight loss, ≥ 10%, n (%) | 1 (1.5) | 13 (18.8) | 12 (16.7) | 2 (3.1) | 12 (17.6) | 12 (16.9) | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.78 |

| HbA1c, mean (SD) | 7.5 (1.2) | 7.2 (1.4) | 7.2 (1.1) | 7.4 (1.1) | 7.4 (1.2) | 7.4 (1.3) | 0.45 | 0.54 | 0.89 |

| HbA1c change from baseline, mean (SD) | − 0.3 (1.1) | − 0.6 (0.8) | − 0.5 (1.2) | − 0.4 (1.2) | − 0.4 (0.8) | − 0.2 (1.3) | 0.39 | 0.98 | 0.43 |

| HbA1c < 8, n (%) | 42 (64.6) | 54 (79.4) | 57 (80.3) | 44 (71.0) | 51 (76.1) | 52 (74.3) | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.92 |

| HbA1c < 7, n (%) | 26 (40.0) | 34 (50.0) | 35 (49.3) | 27 (43.5) | 27 (40.3) | 30 (42.9) | 0.75 | 0.66 | 0.91 |

| Systolic blood pressure change, mmHg, mean (SD) | 0.0 (14.7) | − 4.0 (15.0) | − 2.3 (14.4) | 1.8 (15.8) | − 2.0 (14.9) | − 1.0 (14.7) | 0.09 | 0.28 | 0.54 |

| Diastolic blood pressure change, mmHg, mean (SD) | − 0.9 (7.6) | − 1.3 (8.1) | − 2.0 (8.2) | 1.5 (8.0) | − 0.3 (7.4) | − 1.5 (7.6) | 0.42 | 0.13 | 0.49 |

| Total cholesterol change, mg/dl, mean, (SD) | 0.0 (25.1) | − 6.2 (27.0) | − 4.3 (27.9) | −1.6 (30.4) | − 7.6 (29.4) | 1.1 (28.9) | 0.14 | 0.82 | 0.20 |

| High-density lipoprotein change, mg/dl, mean (SD) | 1.0 (6.0) | 1.7 (7.1) | 2.9 (6.8) | 1.8 (5.7) | 3.7 (6.4) | 3.8 (6.5) | 0.21 | 0.059 | 0.53 |

| Low-density lipoprotein change, mg/dl, mean (SD) | − 3.3 (22.4) | − 3.0 (21.0) | − 3.5 (26.0) | −3.3 (23.5) | − 7.7 (24.4) | − 0.6 (24.7) | 0.57 | 0.78 | 0.39 |

| Triglyceride change, mg/dl, mean (SD) | 12.5 (79.7) | − 56.0 (252.6) | − 21.3 (80.7) | 5.3 (72.9) | − 59.0 (265.4) | −6.5 (107.0) | 0.019 | 0.40 | 0.12 |

| MMAS, change mean (SD) | − 0.08 (1.43) | − 0.08 (1.38) | − 0.04 (1.48) | 0.07 (1.18) | 0.13 (1.17) | 0.03 (1.11) | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.93 |

MNT medical nutrition therapy compared to in-person lifestyle intervention and telephone conference call lifestyle intervention, MMAS Morisky Medication Adherence Scale

*P values for change from baseline from repeated measures analysis combining data from both 6-month and 12-month follow-up; P values for 6- and 12-month time points are individually reported in Appendix Table 2

Figure 2.

One-year weight loss: mean (a), 5% (b), and 10%(c).

Diabetes medication changes are shown in Appendix Figure 1. There was numerically more reduction of insulin and sulfonylurea in the LI groups compared with MNT, but this was not statistically significant.

There was one death due to a mechanical fall in a telephone LI arm participant (who was not taking medication that could cause hypoglycemia; deemed by the DSMB to be unrelated to LI); there were no other serious adverse events or serious hypoglycemia deemed to be related to LI.

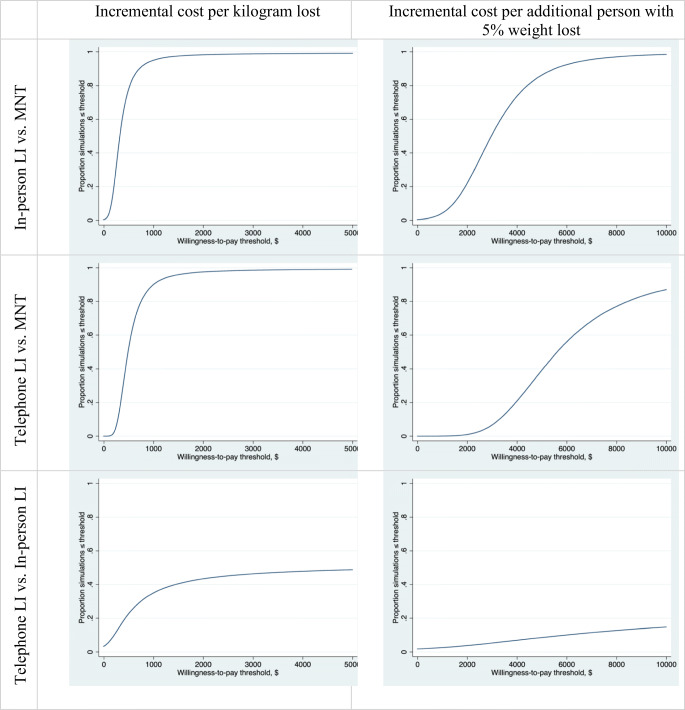

The cost analysis (Table 3) showed 12-month intervention costs per person of $275 for MNT, $1749 for in-person LI, and $1750 for telephone LI. Diabetes medication costs differed among groups at baseline. The change in medication costs per person for the first 12 months of the intervention were $316 for MNT, − $369 for in-person LI, and $64 for telephone LI, figures that incorporate medication initiation, cessation, and dose change. The total incremental 12-month cost per person compared to MNT was $789 for in-person and $1223 for telephone LI. The incremental cost per kilogram weight loss compared to MNT was $321 for in-person and $483 for telephone LI; the cost per percent weight loss was $296 for in-person and $432 for telephone LI. Probabilistic sensitivity analyses are in Figure 2 and Appendix Table 3.

Table 3.

One-Year Cost-effectiveness of In-Person and Telephone Conference Call Lifestyle Intervention from the Payor Perspective

| MNT | In-person LI | Telephone LI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost analysis* | |||

| Intervention cost (95% CI) | $275 (243–308) | $1749 (1622–1876) | $1750 (1624–1876) |

| Change in glucose-lowering medication cost, months 0–12, mean (95% CI) | $316 (−111 to729) | − $369 (− 767 to 3) | $64 (− 348 to 488) |

| Total cost (95% CI) | $591 (162–1005) | $1380 (962–1772) | $1814 (1384–2255) |

| Incremental cost compared to MNT | - | $789 (210–1365) | $1223 (629–1826) |

| Incremental effectiveness compared to MNT | |||

| Incremental weight change (kg) | - | 2.46 | 2.53 |

| Incremental weight change (%) | - | 2.67 | 2.83 |

| Incremental number of patients with 5% weight loss | - | 0.27 | 0.22 |

| Cost-effectiveness compared to MNT | |||

| Incremental cost per kg lost | - | $321 | $483 |

| Incremental cost per 1% weight lost | - | $296 | $432 |

| Incremental cost per additional person with 5% weight loss | - | $2960 | $5613 |

*Costs calculated as changes relative to baseline; per-person cost reported in 2018 US dollars; incremental changes compared to MNT

Assumptions: 140 participants in steady state over 1 year (no explicit startup cost). Personnel costs in the intervention arm include 2 FTE dietitians, 10% oversight time from experienced dietitian or manager, 1 full-time administrative coordinator, and 5% physician FTE for medical management and oversight. Since personnel time is calculated on an FTE equivalent, the FTE allocation was considered to include start-up/training costs

DISCUSSION

In this practice-based translation of an evidence-based group LI, delivered either in person or via telephone conference call, LI yielded clinically significant weight loss compared with MNT with no difference in outcomes between LI delivery formats at 1 year. There was equivalent group attendance in the in-person and telephone LI arms, suggesting that remote delivery can be as engaging as in-person while offering potential for delivery at scale, increasing accessibility. Significantly more LI participants than MNT participants achieved 5% and 10% weight loss at 12 months, with over 40% of LI patients losing 5% and over 15% of LI participants achieving 10% weight loss, a threshold that substantially impacts overall health.16

REAL HEALTH-Diabetes LI yielded ~ 5% 1-year weight loss in a socioeconomically diverse usual care cohort, using a less intensive adaptation of the approach developed in the DPP and Look AHEAD LI programs, which achieved 1-year weight loss results of 7.2% and 8.6%, respectively, among highly screened research participants.17 Other less intensive Look AHEAD translations have been less effective. For example, the I-D Health trial reported 1.2% mean weight loss in a program that used a community-based encouragement design with low intervention enrollment.18 Fit Blue’s phone-based adaptation of Look AHEAD achieved 2.1% weight loss at 12 months in overweight military personnel without diabetes.19 I-D Health and Fit Blue did not employ registered dietitians as the interventionists.18 A randomized trial of Weight Watchers plus online certified diabetes educator counseling in primary care compared with standard care yielded 12-month weight loss of 4.4% with 26% reduction of diabetes medications, compared with 1.9% weight loss and 12% medication reduction for standard care.20 Several components of this intervention were similar to REAL HEALTH-Diabetes, including self-monitoring, use of healthcare professionals, and support for diabetes medication reduction. Overall, a meta-analysis of previous weight loss interventions in primary care reported a mean weight loss of 1.36 kg at 12 months.21

The cost of the REAL HEALTH-Diabetes LI was approximately $1750 per person for 12 months, which is comparable with the cost of other LI programs22, 23 and very similar to a contemporaneous, less intensive, dietitian-delivered VA group medical visit nutrition counseling program (4% mean weight loss at 48 weeks; $1513 per patient per year).24 This compares favorably to the cost of on-patent weight loss or glucose-lowering medications that are recommended to promote weight loss ($3600–$7200 or more per year for lorcaserin, SGLT2 inhibitors, or GLP-1 receptor agonists).25 MNT intervention cost is substantially lower than either LI approach. In this trial, MNT also resulted in weight loss as in many other studies.26, 27 However, cost-effectiveness analyses (Fig. 3 and Appendix Figure 2) demonstrate generally favorable cost-effectiveness of LI compared with MNT due to higher effectiveness.

Figure 3.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves for comparisons across study arms. Likelihood (y-axis) that the first arm would be preferred to the second arm at a given willingness-to-pay threshold (x-axis). Estimates based on 100,000 simulations. LI, lifestyle intervention; MNT, medical nutrition therapy.

Our goal was to understand costs from the payor and health system perspectives, as these will govern whether the program is offered to patients. Patients’ out-of-pocket and indirect costs are beyond the scope of this analysis. However, all participants, many of whom received care at health center sites, faced these costs just as patients would outside the study context. To the extent that such costs had an adverse impact on the reach of the intervention and the engagement of the participants, those costs would be reflected in the effectiveness estimates. By not accounting for other putative health benefits of lifestyle intervention,28–30 this analysis may be a conservative estimate of the cost-effectiveness of LI.

It is important to note several limitations. First, group LI is not for everyone, as indicated by the recruitment flow in the CONSORT diagram (Fig. 1) and description of recruitment for this project.9 Participants must be motivated, committed, and able to participate for it to be effective. While this intervention and medication titration protocol demonstrates scalability within a single healthcare system, results may not generalize beyond a healthcare system. The MNT arm included facilitated referral to a dietitian, but the study did not pay for MNT, and co-pays and deductibles may have precluded some participants from receiving the recommended effective dose of MNT.26, 27 Therefore, this study likely reflected real-world MNT utilization and underestimated the effectiveness of optimal and adequately covered MNT. If lifestyle intervention had also required co-pays, it likely would have reduced participation rates and influenced the outcome. However, the fact that participants did not incur out-of-pocket costs for LI participation and had lower medication costs allows us to assess the potential impact of offering such lifestyle programs without the cost-sharing requirements that further increase the financial burden of diabetes and lead to cost-related non-adherence31 and deterioration of glycemic control.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, REAL HEALTH-Diabetes demonstrated that a behavioral lifestyle intervention could be adapted and delivered effectively in usual care and community health center practices. It achieved clinically significant weight loss in both in-person and scalable telephone conference call group formats compared with MNT, with reasonable cost-effectiveness from the health system perspective. Future reports will evaluate patient-reported and behavioral outcomes, other aspects of the intervention, and long-term effectiveness.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(DOCX 1195 kb)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants for their partnership. In addition, the authors are indebted to Wynne Armand, MD; Elisha Atkins, MD (deceased); Roger Pasinski, MD; Sheila Arsenault, RN; James Morrill, MD, PhD; Lori Hooley, RN; Paul Copeland, MD; Jeanne Steppel-Resnik, MD; Kristin Dalton; Amy Dushkin; and Roshni Singh for their support of and contributions to this project. Finally, the authors gratefully acknowledge consultation from the New York Regional Center for Diabetes Translation Research (P30 DK111022) on the design and implementation of this project.

Guarantor

DJW and LMD had full access to the data in the study and take full responsibility for the work as a whole, including the study design, data integrity, and accuracy of the analysis.

Author Contributions

DJW and LMD conceived of the study and drafted the manuscript. YC and BP performed statistical analyses. DEL, LB, VG, JM, AR, BC, RL, and AW contributed to study design, collection and interpretation of data, and revised the manuscript critically for intellectual content. All authors give approval of the manuscript version to be submitted.

Funding Information

This work is financially supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R18DK102737) to DJW and LMD, under PAR 12-172, Translational Research to Improve Obesity and Diabetes Outcomes.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02320253) and was approved by the Partners HealthCare IRB. All participants gave written, informed consent before any study procedures were performed.

Conflict of Interest

LMD serves on the Advisory Boards of Omada Health, JanaCare, and WW, Inc. DJW serves on two Data Monitoring Committees for clinical trials sponsored by NovoNordisk.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ma C, Avenell A, Bolland M, et al. Effects of weight loss interventions for adults who are obese on mortality, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2017;359:j4849. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pillay J, Armstrong MJ, Butalia S, et al. Behavioral Programs for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(11):848–60. doi: 10.7326/M15-1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U. S. Preventive Services Task Force. Curry SJ, Krist AH, et al. Behavioral Weight Loss Interventions to Prevent Obesity-Related Morbidity and Mortality in Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;320(11):1163–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.13022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haire-Joshu D, Hill-Briggs F. Treating Obesity-Moving From Recommendation to Implementation. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(11):1447–49. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wing RR, Bolin P, Brancati FL, et al. Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(2):145–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1212914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delahanty LM, Dalton KM, Porneala B, et al. Improving diabetes outcomes through lifestyle change--A randomized controlled trial. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015;23(9):1792–99. doi: 10.1002/oby.21172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delahanty LM, Chang Y, Levy DE, et al. Design and participant characteristics of a primary care adaptation of the Look AHEAD Lifestyle Intervention for weight loss in type 2 diabetes: The REAL HEALTH-diabetes study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;71:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2018.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldman V, Dushkin A, Wexler DJ, et al. Effective recruitment for practice-based research: Lessons from the REAL HEALTH-Diabetes Study. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2019;15:100374. doi: 10.1016/j.conctc.2019.100374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wadden TA, West DS, Delahanty L, et al. The Look AHEAD study: A description of the lifestyle intervention and the evidence supporting it. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14(5):737–52. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood M, et al. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008;10(5):348–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07572.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 12.Krousel-Wood M, Islam T, Webber LS, et al. New medication adherence scale versus pharmacy fill rates in seniors with hypertension. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(1):59–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pi-Sunyer X, Blackburn G, Brancati FL, et al. Reduction in weight and cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes: One-year results of the Look AHEAD trial. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(6):1374–83. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanders GD, Neumann PJ, Basu A, et al. Recommendations for Conduct, Methodological Practices, and Reporting of Cost-effectiveness Analyses: Second Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. JAMA. 2016;316(10):1093–103. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.12195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johansen MY, MacDonald CS, Hansen KB, et al. Effect of an Intensive Lifestyle Intervention on Glycemic Control in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017;318(7):637–46. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.10169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evert AB, Dennison M, Gardner CD, et al. Nutrition Therapy for Adults With Diabetes or Prediabetes: A Consensus Report. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(5):731–54. doi: 10.2337/dci19-0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delahanty LM, Nathan DM. Implications of the Diabetes Prevention Program and Look AHEAD clinical trials for lifestyle interventions. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(4 Suppl 1):S66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liss DT, Finch EA, Cooper A, et al. One-year effects of a group-based lifestyle intervention in adults with type 2 diabetes: A randomized encouragement trial. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;140:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2018.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krukowski RA, Hare ME, Talcott GW, et al. Dissemination of the Look AHEAD Intensive Lifestyle Intervention in the United States Military: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2018;26(10):1558–65. doi: 10.1002/oby.22293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Neil PM, Miller-Kovach K, Tuerk PW, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a nationally available weight control program tailored for adults with type 2 diabetes. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2016;24(11):2269–77. doi: 10.1002/oby.21616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Booth HP, Prevost TA, Wright AJ, et al. Effectiveness of behavioural weight loss interventions delivered in a primary care setting: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Fam Pract. 2014;31(6):643–53. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmu064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawlor MS, Blackwell CS, Isom SP, et al. Cost of a group translation of the diabetes prevention program: Healthy living partnerships to prevent diabetes. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(4 Suppl 4):S381–89. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xin Y, Davies A, McCombie L, et al. Within-trial cost and 1-year cost-effectiveness of the DiRECT/Counterweight-Plus weight-management programme to achieve remission of type 2 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(3):169–72. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30346-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yancy WS, Jr., Crowley MJ, Dar MS, et al. Comparison of Group Medical Visits Combined With Intensive Weight Management vs Group Medical Visits Alone for Glycemia in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: A Noninferiority Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(1):70-79.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Davies MJ, D'Alessio DA, Fradkin J, et al. Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes, 2018. A Consensus Report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) Diabetes Care. 2018;41(12):2669–701. doi: 10.2337/dci18-0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evert AB, Boucher JL, Cypress M, et al. Nutrition therapy recommendations for the management of adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(11):3821–42. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franz MJ, MacLeod J, Evert A, et al. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Nutrition Practice Guideline for Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes in Adults: Systematic Review of Evidence for Medical Nutrition Therapy Effectiveness and Recommendations for Integration into the Nutrition Care Process. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2017;117(10):1659–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2017.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haw J, Galaviz KI, Straus AN, et al. Long-term sustainability of diabetes prevention approaches: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1808–17. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.6040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lean MEJ, Leslie WS, Barnes AC, et al. Durability of a primary care-led weight-management intervention for remission of type 2 diabetes: 2-year results of the DiRECT open-label, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(5):344–355. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gregg EW, Chen H, Wagenknecht LE, et al. Association of an intensive lifestyle intervention with remission of type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2012;308(23):2489–96. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.67929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patel MR, Resnicow K, Lang I, et al. Solutions to Address Diabetes-Related Financial Burden and Cost-Related Nonadherence: Results From a Pilot Study. Health Educ Behav. 2018;45(1):101–11. doi: 10.1177/1090198117704683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 1195 kb)