Abstract

The emotional tone of nurses’ voice toward residents has been characterized as overly controlling and less person-centered. However, it is unclear whether this critical imbalance also applies to acutely ill older patients, who represent a major subgroup in acute hospitals. We therefore examined nurses’ emotional tone in this setting, contrasting care interactions with severely cognitively impaired (CI) versus cognitively unimpaired older patients. Furthermore, we included a general versus a geriatric acute hospital to examine the role of different hospital environments. A mixed-methods design combining audio-recordings with standardized interviews was used. Audio-recorded clips of care interactions between 34 registered nurses (Mage = 38.9 years, SD = 12.3 years) and 92 patients (Mage = 83.4 years, SD = 6.1 years; 50% with CI) were evaluated by 12 naïve raters (Mage = 32.8 years, SD = 9.3 years). Based on their impressions of the vocal qualities, raters judged nurses’ emotional tone by an established procedure which allows to differentiate between a person-centered and a controlling tone (Cronbach’s α = .98 for both subscales). Overall, findings revealed that nurses used rather person-centered tones. However, nurses’ tone was rated as more controlling for CI patients and in the geriatric hospital. When controlling for patients’ functional status, both effects lost significance. To our knowledge, this is the first study that examined nurses’ emotional tone in the acute hospital setting. Findings suggest that overall functional status of older patients may play a more important role for emotional tone in care interactions than CI and setting differences.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10433-019-00531-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Inpatient, Cognitive impairment, Functional status, Elderspeak, Person-centered communication

Introduction

The international literature indicates that acute hospitals are not adapted to the needs of older patients, particularly of those with cognitive impairment (George et al. 2013; Mukadam and Sampson 2011). In fact, age discrimination including elderspeak has been identified as underlying factor, which might contribute to inefficient communication, mental health problems, and eventually to adverse outcomes such as longer length of stay, institutionalization, and increased mortality (Digby et al. 2012; George et al. 2013). However, most of the existing studies on elderspeak such as research on the emotional tone of nurses’ voice were derived from care interactions in the nursing home setting (Williams et al. 2012, 2017). Surprisingly, an in-depth examination of elderspeak in the acute hospital setting has not been undertaken so far. However, the identification of potentially controlling tones of voice toward older patients is highly relevant considering their high share in the total patient population in acute hospitals. For example, a recent representative study conducted in Germany has estimated that 65% of the hospital population is older than 65 years, of whom 40% showed cognitive impairment (Hendlmeier et al. 2018). Substantial proportions of acutely ill older patients with cognitive impairment have also been reported for other countries, which are expected to further increase (Mukadam and Sampson 2011). Thus, this paper strives to fill an important gap in the international research by examining differences in nurses’ emotional tone in terms of a controlling versus a person-centered tone toward older patients in the acute hospital setting. As a novel approach, we also considered the role of older patients’ characteristics and different hospital environments for explaining nurses’ emotional tone.

Previous research and conceptual considerations on emotional tone

An imbalance in the emotional tone of voice (i.e., underlying affective qualities of communication) represents one crucial element of elderspeak (Williams et al. 2012, 2017). Studies examining nurses’ emotional tone of voice toward residents with dementia-related disorders in the long-term care setting via proximal percepts (i.e., voice quality ratings of naïve listeners; Bänziger et al. 2015) have demonstrated overly controlling, but less person-centered communication (Williams et al. 2017). More precisely, person-centered communication has been characterized by caring (nurturing, caring, warm, supportive) and respectful (polite, affirming, respectful) tones of voice (Williams et al. 2012, 2017). Furthermore, person-centered communication was negatively correlated with controlling communication, which involves dominating, controlling, directive, bossy, and patronizing tones of voice (Williams et al. 2012).

In the previous literature (Williams et al. 2012), the imbalance in the emotional tone of nurses’ voice toward older residents has been explained via negative age stereotypes relying on the Communication Predicament of Aging Model (CPA; Ryan et al. 1995). The negative feedback loop starts with the recognition of stereotype-consistent cues such as memory deficits, which then trigger controlling tones of voice toward older adults. However, the frequent exposure to controlling tones may restrict meaningful social interactions and reinforce stereotype-consistent behavior of older adults such as withdrawal (Williams and Herman 2011). Particularly in individuals with dementia-related disorders, controlling tones of voice are assumed to have harmful effects. First, studies have shown that controlling tones increased the likelihood of residents’ challenging behavior (Williams and Herman 2011). Second, individuals with cognitive disorders might react more sensitive to controlling tones of voice because the nonverbal communication pathway becomes more important in the course of dementia when compared to the verbal pathway (Kuemmel et al. 2014). The positive effect of person-centered tones of voice has also been indicated by studies showing positive associations between person-centered communication and residents’ cooperation during care (Savundranayagam et al. 2016). This corroborates the general assumption that person-centered communication plays a key role in the care of older adults with dementia-related disorders by affirming personhood (Buron 2008), whereas controlling communication may threaten it (Williams et al. 2017).

Although the CPA model is a well-established framework, it likely underrates factors that might be relevant for nurses’ emotional tone of voice toward older adults. The Age Stereotypes in Interactions Model (ASI; Hummert 1994) points to the importance of three factors, which have not been considered in the empirical research on emotional tone so far: (a) the perceiver’s self-system, (b) the older target person’s characteristics, and (c) the context.

First, in terms of perceiver’s characteristics, advanced age, high cognitive complexity, and high quality of previous contacts with older adults were shown to counteract negative stereotype activation (Hummert 1994).

Second, characteristics of older target persons need to find consideration. Research in German nursing homes, for example, has shown that particularly female and physically vulnerable residents were exposed to patronizing talk (Sachweh 1998). The concept of physical disability comprises functional impairment in terms of a dependency in performing activities of daily living such as dressing or bathing (Fried et al. 2004). Although functional impairment represents a typical feature of cognitively impaired older patients (Pedone et al. 2005), it remains unclear from the previous literature whether the controlling tone of nurses’ voice toward residents with dementia-related disorders is elicited by typical dementia behaviors or rather by cues of disability in general. Furthermore, differences in emotional tone toward severely cognitively impaired versus cognitively unimpaired older adults have not been examined so far.

Third, the context such as different acute hospital environments can be expected to play a role. For example, geriatric hospitals may have more patients with severe functional impairment, but also more psychogeriatrically trained staff (Zieschang et al. 2010). The training may lead to less negative age stereotyping and less controlling tones of geriatric compared to general hospital staff. However, being continuously confronted with vulnerable older patients might also contribute to more negative attitudes (de Almeida Tavares et al. 2015).

Objectives and hypotheses

We examined differences in the (im)balance of nurses’ emotional tone between a cognitively unimpaired group (CU), that is patients with no or minor cognitive impairment, and a severely cognitively impaired group (CI) in a general versus a geriatric acute hospital. We hypothesize that encounters with CI patients are associated with increased negative age stereotyping which may lead to more controlling and less person-centered tones of nurses’ voice when compared to CU patients (Hypothesis 1). In terms of context, we expect a lower discrepancy in emotional tone patterns between CU and CI patients in the geriatric hospital setting, because both typically show a rather low functional status (Hypothesis 2). At the exploratory level, nurses’ characteristics in terms of perceived stress level, self-rated psychogeriatric knowledge, and chronological age will find consideration.

Methods

Recruitment

Data were collected in two academic acute hospitals from September 2017 to March 2018, which were both affiliated with the university. Both hospitals were located in the city center of a medium-sized (> 100.000 inhabitants) southwestern town in Germany, around 4 km apart. For the general acute hospital setting, an internal medicine ward (n = 36 beds, mean length of stay = 4.9 days) of the department for cardiology, angiology, and pulmonology (n = 114 beds) was chosen providing care for younger and older patients. For the geriatric acute hospital setting (n = 105 beds), one ward providing treatment for geriatric patients was selected (n = 35 beds; mean length of stay = 16.5 days). The first author completed a two-month internship in both hospitals to prepare the assessments.

The study was approved by the ethical board of the Faculty of Behavioral and Cultural Studies at Heidelberg University in July 2017, as well as by hospital staff leadership and staff councils. Detailed information on the recruitment procedure is presented in Supplementary Fig. 1. All registered nurses who were willing to participate were eligible for inclusion. Other types of nurses such as nursing aides were excluded in order to analyze a more homogeneous subgroup. In the first step, all patients of the wards were screened for eligibility. Inclusion criteria for patients were a minimum age of 65 years and severe cognitive impairment in 50% of the sample. As medical records did not consistently provide information on patients’ cognitive status, the assignment to the CI group was based on the 10/11 cutoff of the 6-Item Cognitive Impairment Test (6CIT; Hessler et al. 2017). This screening tool was chosen because it represents a validated and time-efficient instrument in the acute hospital setting, with the 10/11 cutoff showing the best sensitivity–specificity ratio (88% and 95%, respectively). For the final recruitment phase, the 6CIT was used as a pre-screening tool. That is, only patients who exceeded the cutoff were included in the study. Exclusion criteria were terminal illness, isolation, insufficient knowledge of the German language, and impending discharge or transfers. All eligible patients were visited in their rooms and informed about the study. Written informed consent (WIC) was obtained by all participants or the legal representatives of CI participants. Furthermore, the WIC of all co-patients in the room was obtained because their utterances might have become part of the audio-recordings. This applies, for example, to younger co-patients in the room. If these steps were successful, registered nurses who were responsible for eligible patient rooms including accompanying nursing aides were asked for their WIC (see Supplementary Fig. 1).

Data collection consisted of three parts: (a) audio-recordings during the morning (49%) or evening care (51%); (b) standardized interviews with patients and nurses; and (c) extracting basic patient information including age, gender, functional status, and length of hospital stay from the medical information system. PCM digital audio-recorders (48 kHz, 16 bits) were placed in the patient rooms and immediately started before the nurse entered the room. Most of the nurses (76%) were recorded during more than one patient interaction, but not more than six times. Each patient was only measured once.

Interviews with patients were conducted by trained research assistants to assess additional sociodemographic (educational level, mother tongue, marital status, housing situation), health-related (subjective health indicators), and hospital-related variables (satisfaction with hospital care, perceived age discrimination) that were not consistently available from the medical information system. The training, for example, included communication strategies for CI patients. Whenever interviewers assumed that the patient was not able to understand the item, the answer was coded as missing. After the first measurement, nurses’ sociodemographic and professional background was examined. Interaction-related interviews focused on nurses’ evaluation of a patient’s cognitive status, nurses’ perceived stress level, and participants’ reactivity.

Measures

Patients’ functional status was evaluated by nurses using the Barthel Index (Mahoney and Barthel 1965). Patients’ communication behavior was examined by trained interviewers using an observational communication behavior assessment tool for dementia patients (CODEM; Kuemmel et al. 2014). This tool showed excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .95) as well as convergent and discriminant validity (Pearson’s R = .88 and .63, respectively). CODEM consists of 15 items rated on a 6-point Likert scale (0 = never and 5 = always) within 3 min. Higher values represent a better functional status as well as a higher extent of communication behavior.

Nurses’ evaluation of a patient’s cognitive status was examined by a single item ranging from 1 (no cognitive impairment) to 4 (severe cognitive impairment; Hessler et al. 2017). This global measure was used because nurses’ evaluation of a patient’s cognitive status might be more strongly linked with nurses’ behavior when compared to the underlying cognitive performance. Nurses were also asked for their current stress level using an 11-point scale from 0 (not at all) to 10 (extremely). Self-rated psychogeriatric knowledge was operationalized by a single item ranging from 1 (very low) to 5 (very high) (Tropea et al. 2017).

Emotional tone rating procedure

Raters’ characteristics

Thirteen raters participated in the study. One was excluded due to unexpected inter-item correlations. The 12 remaining raters were between 25 and 53 years old (Mage = 32.8 years, SD = 9.3 years, 83% female).

Due to data protection requirements, raters were recruited from the local university environment of the first author. Raters provided WIC and received a lottery incentive. Educational level was high, with 92% of raters having a university degree. Individuals with a non-German mother tongue and knowledge of the study’s goals were excluded. In line with previous studies (Williams et al. 2012), there was no specific training, because naïve raters were expected to have sufficient semantic knowledge. In fact, Williams et al. (2012) demonstrated an excellent inter-rater consistency among untrained raters [ICC (2,1) = .95]. We also calculated ICC estimates and their 95% confidence intervals for the two subscale means based on a mean rating (k = 12), consistency, two-way random effects model. According to the guideline of Koo and Li (2016), inter-rater consistency was also excellent in our study with ICC (2,12) = .91 for the person-centered subscale and ICC (2,12) = .90 for the control-centered subscale.

Emotional tone rating scale

The emotional tone of nurses’ voice was operationalized by the emotional tone rating scale (Williams et al. 2012). More precisely, the emotional tone rating scale consists of 12 adjectives rated by naïve listeners on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = not at all and 5 = very). Psychometric analysis of Williams et al. (2012) suggested a two-factor solution with the items “nurturing”, “affirming”, “respectful”, “supportive”, “polite”, “caring”, “warm” belonging to the subscale person-centered communication (α = .98) and the items “directive”, “patronizing”, “bossy”, “dominating”, “controlling” to the subscale control-centered communication (α = .94). According to the guideline of Sousa and Rojjanasrirat (2011), forward translation into German was done by two bilingual, independent translators for whom German was their mother tongue. Both had also excellent knowledge of the English language. Discrepancies in translations were resolved by the first author and a third independent, bilingual individual. In the second step, a native English speaker back-translated the adjectives, revealing a conceptually equivalent version to the original one.

We conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of emotional tone ratings using R (Version 3.5.1) and the lavaan package (Version 0.6-3; Rosseel 2012) to test the fit of the two-factor solution in the current sample. Due to nonnormally distributed data, maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors was used for correction (Rosseel 2012). According to widely used rules of thumb (Schermelleh-Engel et al. 2003), a good fit was defined as follows: Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) and Comparative Fit Index (CFI) ≥ .97; Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA) ≤ .05; and Standard Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) ≤ .05. CFA based on the full dataset of all care interactions and raters (N = 1104 cases) revealed a poor model fit when single indicators were uncorrelated. Modification indices suggested that correlations between two pairs of person-centered indicators (i.e., caring–warm, respectful–polite) should be allowed. This step led to an improved, but still not an acceptable model fit. Further inspection revealed high modification indices for all inter-indicator correlations with bossy as well as double loadings for bossy, and therefore this item was eliminated from the model and all further data analyses. After this step, indices pointed to a rather good model fit, with Robust TLI = .961, CFI = .971, RMSEA = .079 (left boundary of the 90% confidence interval = 0.070), and SRMR = .048.

Furthermore, an exploratory factor analysis supported a strong first factor (eigenvalue = 9.73, explaining 81% of variance) and a weaker second factor (eigenvalue = 1.32, explaining 11% of the variance) as found by Williams et al. (2012). The internal consistency was also excellent in our sample (Cronbach’s α = .98 for both subscales).

Data preparation and material

Material consisted of 106 care interactions varying in conversation time: (a) 0–10 min (56%), (b) 11–20 min (28%), and (c) > 20 min (16%). First, relevant speakers were identified using Audacity (Version 2.1.3; https://www.audacityteam.org/). For instance, utterances of younger co-patients in the room were part of the audio-recording, although they did not belong to the target group. Following the procedure of Williams (2006), a segment was eligible for the rating material when the following criteria were met: (a) dyadic nurse–patient interaction, (b) high quality of audio-signal, (c) length of conversation of at least 1 min, and (d) maximum continuous pause of 15 s. Thirteen percent of the material was excluded resulting in a sample of 92 patients and 34 nurses. Second, one segment was randomly selected from eligible segments of a care interaction to get a representative sample of audio-recordings. According to Williams and Herman (2011), longer segments were limited to the first minute to reduce rater burden. Finally, personal information was removed to ensure the anonymization of participants.

Transcriptions were based on the cGAT conventions using the FOLK EditoR (FOLKER; Schmidt and Schütte 2015). The clips covered typical daily care tasks such as washing (15%), dressing (10%), transferring (15%), using the toilet (4%), monitoring vital signs (24%), task-oriented communication (31%), and interpersonal communication (1%). The broad range of care activities indicates that we were able to capture the full heterogeneity of care interactions by including the morning and evening care.

Rating procedure

Sessions were conducted from May to June 2018 in the morning or the afternoon. Raters underwent three 1-h rating sessions on different days in order to reduce cognitive fatigue, which emerged as manageable from previous research (Williams et al. 2012). Sessions took place in a quiet room in groups of one or two raters. In the first session, raters were familiarized with the material and rating procedure in one test trial. Raters were instructed to carefully listen to audio-recorded clips of care interactions and to evaluate the tone of nurses’ voice for each adjective.

Setting (general vs. geriatric hospital) and cognitive group (CU vs. CI) were counterbalanced across sessions. Within each session, the standardized set of 30–32 clips was randomly presented using OpenSesame (Version 3.2.4; Mathôt et al. 2012). Raters could listen to each clip for a second time. This option was used in 0–15% of cases. Raters were informed about the progress at intervals of five clips to keep motivation high. After half of the trials, there was a break of 5 min to minimize cognitive fatigue.

Data analysis

The main analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS version 24. Emotional tone (im)balance was quantified for each clip by dividing the mean ratings of the person-centered scale by those of the control-centered scale (1 = balance, < 1 = tendency toward a controlling tone of voice, > 1 = tendency toward a person-centered tone of voice). Further analyses were conducted by ratios because this transformation led to normally distributed data and a reduced number of variables.

In order to detect group differences at a medium effect size level (d = 0.50, α = .05; power = .80), a number of at least 50 care interactions with n = 25 CU and n = 25 CI patients per hospital setting were predetermined by an a priori G*Power analysis (Faul et al. 2007). The effects of cognitive group and setting on emotional tone (im)balance were evaluated using a two-factorial analysis of variance. Additionally, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was conducted with patients’ functional status as a covariate. For F tests, partial eta squared (η2p) was considered as an effect size indicator (0.01: small effect; 0.06: medium effect; and 0.14: large effect; Cohen 1988). For pairwise comparisons of parametric and nonparametric data, t tests and Mann–Whitney U tests as well as their respective effect size indicators Cohen’s d (0.20: small effect; 0.50: medium effect; and 0.80: large effect) and Pearson r (0.10: small effect; 0.30: medium effect; and 0.50: large effect) were computed (Cohen 1992).

For analyzing the role of different blocks of predictors (block 1: cognitive group and acute hospital setting; block 2: patients’ functional status; and block 3: nurses’ self-rated psychogeriatric knowledge), a hierarchical regression analysis was performed. Given our relatively small sample size, only those variables were included in the model that were assumed to play a dominant role based on the theoretical framework. A significance level of p < .05 was set throughout.

Results

Sample description

Tables 1 and 2 display the sample characteristics of patients and nurses. For most of the variables, comparisons of patients’ data between the general versus the geriatric hospital setting yielded no group differences. Importantly, patients in the geriatric hospital setting showed a significantly lower functional status in general (CU: M = 61.00, SD = 23.38; CI: M = 40.21, SD = 23.84) when compared to those of the general hospital (CU: M = 86.20, SD = 17.16; CI: M = 52.50, SD = 26.94). Higher functional impairment was also associated with a significantly longer hospital stay (see Table 1). As evident from Table 2, 50% of the nurses had specific geriatric training.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics of the general versus the geriatric acute hospital setting

| Variable | General acute hospital | Geriatric acute hospital | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | M | SD | % | Range | n | M | SD | % | Range | p | |

| Age (years) | 47 | 82.6 | 5.6 | 66–93 | 45 | 84.3 | 6.5 | 71–96 | .173 | ||

| Female/male | 47 | 43/57 | 45 | 71/29 | .006 | ||||||

| Cognitive status (6CIT error scores; 0–28)a | 45 | 10.0 | 7.5 | 0–25 | 38 | 11.7 | 9.5 | 0–28 | .341 | ||

| Cognitive group (CI/CU)b | 47 | 47/53 | 45 | 53/47 | .532 | ||||||

| Normal/specialized care unit | – | – | 45 | 84/16 | – | ||||||

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 47 | 10.5 | 4.5 | 3–23 | 45 | 17.2 | 5.9 | 6–38 | < .001 | ||

| Admission to examination (days) | 47 | 5.2 | 3.5 | 0–17 | 45 | 8.4 | 6.4 | 0–24 | .004 | ||

| Lower/intermediate/upper secondary school | 39 | 82/5/13 | 31 | 55/29/16 | .016 | ||||||

| German/non-German mother tongue | 46 | 98/2 | 44 | 98/2 | .975 | ||||||

| Married/divorced/widowed/unmarried | 31 | 52/0/35/13 | 36 | 42/3/44/11 | .661 | ||||||

| Private/nursing/retirement/residential home | 47 | 94/4/0/2 | 41 | 81/7/3/9 | .242 | ||||||

| Functional status (Barthel Index; 0–100)c | 47 | 70.4 | 27.8 | 0–100 | 45 | 49.9 | 25.6 | 10–100 | < .001 | ||

| Communication behavior (CODEM; 0–5)d | 46 | 4.0 | 1.1 | 1.4–5.0 | 38 | 3.8 | 1.3 | 0.3–5.0 | .509 | ||

| Subjective health (1–5)e | 44 | 2.8 | 0.9 | 1–5 | 37 | 3.1 | 0.9 | 1–5 | .106 | ||

| Subjective hearing (1–5)f | 43 | 2.7 | 0.8 | 1–4 | 35 | 2.7 | 1.2 | 1–5 | .900 | ||

| Satisfaction with hospital care (1–5)g | 42 | 1.8 | 0.7 | 1–3 | 37 | 2.1 | 0.8 | 1–4 | .137 | ||

| Perceived age discrimination (yes/no)h | 41 | 0/100 | 37 | 5/95 | .132 | ||||||

The sample size varies depending on the data source, with the smallest numbers for self-reported data due to refused interviews, transfer to medical intervention, or severe cognitive impairment. p values for interval-scaled variables from t tests and for dichotomous variables from Chi-square tests; p values were adjusted using the Bonferroni–Holm correction for multiple univariate comparisons; significant p values are in boldface

a6CIT = 6-Item Cognitive Impairment Test (Hessler et al. 2017); lower error scores indicate better cognitive performance

bCI = severely cognitively impaired patients (6CIT > 10); CU = cognitively unimpaired patients (6CIT ≤ 10)

cFunctional status was operationalized as the sum score of the Barthel Index (Mahoney and Barthel 1965); higher values indicate better performance

dCommunication behavior was operationalized as the CODEM total mean score (Kuemmel et al. 2014); higher values indicate a higher extent of communication behavior

e–gSubjective health, hearing capacity, and satisfaction with hospital care (Keller et al. 2014) were operationalized by single items ranging from 1 (very good) to 5 (very poor)

hPerceived age discrimination was assessed by use of a dichotomous single item (modified from Hudelson et al. 2010)

Table 2.

Nurses’ characteristics of the general versus the geriatric acute hospital setting

| Variable | General acute hospital | Geriatric acute hospital | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | M | SD | % | Range | n | M | SD | % | Range | p | |

| Age (years) | 16 | 39.3 | 13.4 | 22–59 | 14 | 38.6 | 11.5 | 26–59 | .883 | ||

| Female/male | 18 | 78/22 | 16 | 81/19 | .803 | ||||||

| German/non-German mother tongue | 18 | 67/33 | 15 | 53/47 | .435 | ||||||

| Lower/intermediate/qualification for applied upper secondary studies/upper secondary school | 17 | 0/47/29/24 | 15 | 7/40/20/33 | .620 | ||||||

| Registered nurse/geriatric-trained nurse | 17 | 100/0 | 15 | 47/53 | .001 | ||||||

| Experience as a nurse (< 5/5–10/11–15/> 15 years) | 17 | 24/23/0/53 | 15 | 27/40/7/26 | .360 | ||||||

| Experience in the current ward (years) | 16 | 9.1 | 8.9 | 1–27 | 15 | 5.9 | 9.2 | 0–25 | .334 | ||

| Further education on dementia/geriatric care (no/yes) | 15 | 67/33 | 12 | 33/67 | .085 | ||||||

| Self-rated psychogeriatric knowledge (1–5)a | 17 | 3.4 | 0.8 | 2–5 | 15 | 4.1 | 0.8 | 3–5 | .016 | ||

| Participants’ reactivity (1–5)b | 17 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 1.0–2.8 | 16 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 1.0–3.3 | .759 | ||

The sample size varies due to refused interviews (n = 2) or omitted items. p values for interval-scaled variables from t tests and for dichotomous variables from Chi-square tests; p values were adjusted using the Bonferroni–Holm correction for multiple univariate comparisons; significant p values are in boldface

aSelf-rated psychogeriatric knowledge (Tropea et al. 2017); possible range: 1 (very low) to 5 (very high)

bParticipants’ reactivity was examined by use of a modified version of the iEAR evaluation questionnaire of Mehl and Carey (2014) consisting of six items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all and 5 = a great deal); higher mean values represent a higher tendency toward participants’ reactivity

Effect of cognitive impairment and setting on emotional tone

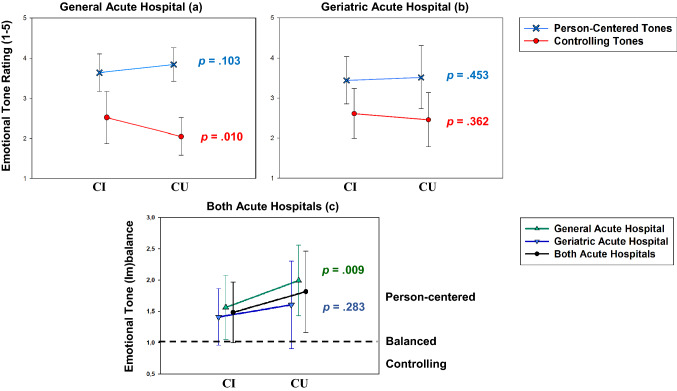

As can be seen in Fig. 1a and b, mean ratings for person-centered tones of voice were consistently higher when compared to controlling tones. In the majority of cases (78%), emotional tone ratios indicated a strong tendency toward person-centered tones (see Fig. 1c). In 15% of cases, ratios pointed toward controlling tones. A balanced emotional tone only appeared in 7% of cases. Ratios did not significantly differ between the morning and the evening care [t(90) = − .14, p > .005].

Fig. 1.

Mean differences in emotional tone ratings between a the general and b the geriatric acute hospital setting. Mean emotional tone ratings for the person-centered (blue line/crosses) and the control-centered subscale (red line/circles) ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very). c Mean emotional tone (im)balance (ratios) for the general (green line, triangle up) and the geriatric acute hospital (blue line, triangle down) as well as for both (black line, circles). 1 = balance, < 1 = tendency toward a controlling tone of voice, > 1 = tendency toward a person-centered tone of voice. Standard deviations are represented by error bars; p values for differences between severely cognitively impaired (CI) patients (n = 46) and cognitively unimpaired (CU) patients (n = 46)

The ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of cognitive group [F(1,88) = 7.10, p = .009, η2p = .075] and setting [F(1,88) = 5.39, p = .023, η2p = .058] on emotional tone (im)balance. Ratios pointed to a stronger tendency toward person-centered tones in CU (M = 1.82) compared to CI patients (M = 1.48). Post hoc Mann–Whitney U tests showed a significant group difference for the control-centered (U = 719.000, p = .008, r = .28), but not for the person-centered subscale (U = 838.500, p = .086).

With respect to hospital setting, a strong use of person-centered tones was observed in the geriatric hospital (M = 1.50), albeit with a lower level when compared to the general hospital setting (M = 1.79). Post hoc Mann–Whitney U tests showed a significant group difference for the control-centered (U = 792.500, p = .038, r = .22), but not for the person-centered subscale (U = 828.500, p = .074). Furthermore, we found a lower imbalance in emotional tone between CI and CU patients in the geriatric hospital [t(34) = 1.01, p = .283], which was only significant in the general hospital [t(45) = 2.72, p = .009, d = 0.80].

Further ANCOVA analyses controlling for differences in functional status revealed a significant main effect of this variable on emotional tone (im)balance [F(1,87) = 11.19, p = .001, η2p = .114]. Indeed, the main effects of cognitive group and setting were no longer significant (p = .502 and .332, respectively).

The role of older target person’s characteristics and perceiver’s self-system

Bivariate correlations on emotional tone (im)balance, older target person’s characteristics, and perceiver’s self-system are displayed in Table 3. Again, patients’ functional status emerged as an important variable showing the highest correlation with the emotional tone ratio (r = .48). Hence, rather person-centered than controlling tones were used in patients with better functional status. Correlations for cognitive status and communication behavior showed moderate effect sizes. For nurses, we found a moderately high correlation between the evaluation of patients’ cognitive status and the emotional tone ratio (r = − .38), but no significant association for the other variables.

Table 3.

Bivariate correlations between emotional tone (im)balance, older target person’s characteristics, and perceiver’s self-system

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Emotional tone ratioa | 1.65 | .59 | – | |||||||

| 2. Patients’ cognitive statusb | 10.75 | 8.44 | − .29* | – | ||||||

| 3. Patients’ functional statusc | 60.39 | 28.54 | .48*** | − .56*** | – | |||||

| 4. Patients’ communication behaviord | 3.93 | 1.21 | .32** | − .82*** | .64*** | – | ||||

| 5. Nurses’ evaluation of cognitive statuse | 1.91 | .94 | − .38*** | .64*** | − .68*** | − .65*** | – | |||

| 6. Nurses’ perceived stressf | 2.28 | 2.65 | − .20 | .21 | − .30** | − .28* | .20 | – | ||

| 7. Nurses’ psychogeriatric knowledgeg | 3.73 | .89 | .16 | − .19 | − .05 | .04 | − .03 | − .12 | – | |

| 8. Nurses’ chronological age | 38.93 | 12.30 | − .03 | − .15 | .11 | .13 | − .16 | − .08 | .19 | – |

n varies between 81 and 92 due to missing data

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

aA higher ratio indicates a stronger tendency toward a person-centered tone of voice

bLower error scores indicate a better cognitive performance

c−dHigher values indicate a better functional status as well as a higher extent of communication behavior

eNurses’ evaluation of patients’ cognitive status; possible range: 1 (no cognitive impairment) to 4 (severe cognitive impairment)

fNurses’ perceived stress level during the care interaction; possible range: 0 (not at all) to 10 (extremely)

gSelf-rated psychogeriatric knowledge; possible range: 1 (very low) to 5 (very high)

As findings of the regression analysis show (see Table 4), cognitive group and setting explained a significant proportion of variance in emotional tone (im)balance (Adjusted R2 = .12, p = .002). Functional status additionally significantly increased the amount of explained variance by 9%. As suggested by ANCOVA results, the factors cognitive group (β = − .07, p = .526) and setting (β = − .13, p = .231) lost significance with the consideration of functional status. Psychogeriatric knowledge accounted for a significant increase of 6% additional variance. Functional status emerged as a strong predictor of emotional tone (im)balance remaining significant after psychogeriatric knowledge was added in Model 3 (β = .36, p = .003). Altogether, the predictors accounted for 25% of the variance in emotional tone (im)balance, which can be considered a moderate effect (Ferguson 2009).

Table 4.

Predicting emotional tone (im)balance: findings of the hierarchical regression analysis

| Block | Predictor | Emotional tone (im)balance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||

| β | β | β | ||

| 1 | Cognitive groupa | − .24* | − .07 | − .03 |

| Acute hospital settingb | − .26* | − .13 | − .25* | |

| 2 | Older target person’s characteristics: functional statusc | .38** | .36** | |

| 3 | Perceiver’s self-system: psychogeriatric knowledged | .28* | ||

| ΔR2 | .14** | .09** | .06* | |

| Adjusted R2 | .12 | .20 | .25 | |

| F | 6.63** | 8.10*** | 8.23*** | |

n = 86; Method = Enter

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

aThe assignment to the cognitive group was based on the 10/11 cutoff of the 6-Item Cognitive Impairment Test (Hessler et al. 2017)

bAcute hospital setting: general acute hospital versus geriatric acute hospital

cA higher sum score of the Barthel Index indicates a better functional performance (Mahoney and Barthel 1965)

dSelf-rated psychogeriatric knowledge (Tropea et al. 2017); possible range: 1 (very low)–5 (very high)

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study investigating differences in emotional tone in the complex acute hospital setting under relatively controlled conditions. Our results partly supported hypothesis 1 in showing more controlling tones of nurses’ voice in CI compared to CU patients across both settings, but comparable levels of person-centered tones. According to the model of Hummert (1994), the increased use of controlling tones in CI patients underpins the fact that negative age stereotyping is more likely in older individuals who trigger cues of functional and mental impairment. Earlier research also revealed a higher use of elderspeak in severely impaired and despondent older adults compared to so-called golden agers, who represent more positive age stereotypes (Hummert et al. 1998). However, our data generally revealed a higher amount of person-centered compared to controlling tones. Although similar findings have been reported in previous research (Williams et al. 2012), results have been differently interpreted as demonstrating an overuse of controlling tones. Nevertheless, substantial positive correlations with challenging behavior at the cross-sectional level suggest that even low levels of controlling tones could have negative effects on older adults (Williams and Herman 2011).

Surprisingly, a comparison between hospital settings revealed more controlling tones in the geriatric compared to the general hospital, which might be explained by patients’ overall low functional status. Thus, it can be assumed that general functional impairment overwhelms the impact of other factors. Indeed, effects for cognitive group and setting did not remain significant when controlling for functional status. In other words, functional impairment seems to be a stronger determinant of controlling tones when compared to cognitive impairment or setting. This finding might be explained by two primary reasons.

The first explanation refers to an increased salience of functional cues. As functional impairment frequently occurs in vulnerable older adults (Fried et al. 2004; Pedone et al. 2005), it may become a salient feature of geriatric patients. Furthermore, functional status represents a key component of geriatric assessments (Fried et al. 2004), which may have raised nurses’ awareness of respective impairments. The dominating role of functional impairment is also supported by the dependency–support script showing a linkage between dependent behaviors of older adults and caregivers’ supportive behavior (Baltes and Wahl 1992).

Second, controlling tones may provide information on nurses’ transient emotions and mental efforts (Frank et al. 2015). To be more precise, controlling tones might reflect a means to cope with task-oriented demands (Hummert and Ryan 1996), which are higher in functionally impaired patients.

In line with our second hypothesis, overall poor functional status was associated with comparable levels of person-centered and controlling tones for both CU and CI patients in the geriatric, but not in the general hospital. This finding again underpins that functional impairment deserves particular attention in terms of negative stereotype activation.

It is important to note that self-rated psychogeriatric knowledge significantly increased the amount of variance in emotional tone (im)balance over and above functional status. This underpins the importance of psychogeriatric education to overcome negative attitudes toward functionally impaired patients. In fact, previous research has shown consistent associations between nurses’ knowledge related to aging and positive attitudes toward older adults (Liu et al. 2013).

Implications

A central finding of this study was that controlling tone was higher toward vulnerable older patients with a lower functional status. Future research should explore critical thresholds of controlling tone and their impact on the mental health of older adults. We also advocate for using new emerging approaches such as comprehensive path models allowing for sophisticated statistical modeling of the whole communication process and its contributing factors (Bänziger et al. 2015). Such models may also help to disentangle the differential role of antecedents of controlling tone.

This study also comes with important practical and organizational implications. Considering the probably positively selected wards in the current study, it can be assumed that controlling tone toward older patients is a frequent occurrence in acute hospitals. Reducing controlling tone through education and training might not only have positive impact on older patients (Williams 2006); it also may have beneficial effects for nurses by reducing challenging behavior, which is considered one of the most distressing events in acute hospitals (Hessler et al. 2018). First interventional studies indicate that it might be possible to reduce controlling tones of nursing home staff for a short time (Williams 2006; Williams et al. 2003). Future studies should extend these findings by considering potential barriers and facilitators of implementation in the acute hospital setting (Tropea et al. 2017). A key practical component may be the exposure of hospital staff to their own audio-recordings. This may help to become more conscious of the negative effects of controlling tones, which are likely to be produced at an implicit level (Frank et al. 2015). The theoretical part should inform about the role of age stereotypes, barriers of communication, characteristics of elderspeak as well as more efficient communication strategies including person-centered approaches.

Limitations

Some limitations have to be mentioned that might affect the interpretation of our results. First, nurses’ awareness of being audio-recorded might have influenced their natural behavior. However, interview data referring to this issue pointed to minor effects of participants’ reactivity.

Second, repeated measurements of some nurses might have caused dependencies in the data. Because such a design is typical for this research area (Williams et al. 2012) and there was a large heterogeneity of patients and care situations, we regarded the 92 care interactions as sufficient and largely independent from each other.

Third, the sample of raters was small and probably positively selected. However, although raters in previous studies (Williams 2006; Williams et al. 2012) were clearly younger compared to our sample, findings were highly comparable.

Finally, the analysis of nurses’ emotional tone was not based on objectively measured acoustic features such as exaggerated intonation and high pitch, which have been identified as nonverbal correlates of highly controlling communication (Hummert and Ryan 1996). Although ratings of voice qualities may reflect subjective impressions from naïve listeners, the high inter-rater reliability demonstrated that distinct qualities of emotional tone can be similarly decoded from the voice.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank all participating patients and nursing staff as well as the directors of both acute hospitals involved in this study for their cooperation. Furthermore, we thank Christina Streib, Sandra Schmitt, and Agnieszka Marciniak for their help in collecting and processing the data. A special thanks goes to Thomas Schmidt, Thomas Spranz-Fogasy, Evi Schedl, and Swantje Westpfahl, Institute of German Language in Mannheim, Germany, for their cooperative role and valuable recommendations in collecting, preparing, and analyzing the linguistic data. We also thank Hannah Stocker and Jonathan Griffiths for proofreading the manuscript with respect to linguistic issues.

Funding

This study was funded by the Robert Bosch Foundation Stuttgart within the Graduate Program People with Dementia in Acute Care Hospitals (GPPDACH), located at the Network Aging Research (NAR), University of Heidelberg, Germany.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in the study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the ethical board of the Faculty of Behavioral and Cultural Studies at Heidelberg University and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Eva-Luisa Schnabel, Email: schnabel@nar.uni-heidelberg.de.

Hans-Werner Wahl, Email: wahl@nar.uni-heidelberg.de.

Anton Schönstein, Email: schoenstein@nar.uni-heidelberg.de.

Larissa Frey, Email: Larissa.Frey@stud.uni-heidelberg.de.

Lea Draeger, Email: L.Draeger@stud.uni-heidelberg.de.

References

- Baltes MM, Wahl H-W. The dependency-support script in institutions: generalization to community settings. Psychol Aging. 1992;7:409–418. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.7.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bänziger T, Hosoya G, Scherer KR. Path models of vocal emotion communication. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0136675. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buron B. Levels of personhood: a model for dementia care. Geriatr Nurs. 2008;29:324–332. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Almeida Tavares JP, da Silva AL, Sá-Couto P, Boltz M, Capezuti E. Portuguese nurses’ knowledge of and attitudes toward hospitalized older adults. Scand J Caring Sci. 2015;29:51–61. doi: 10.1111/scs.12124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digby R, Moss C, Bloomer M. Transferring from an acute hospital and settling into a subacute facility: the experience of patients with dementia. Int J Older People Nurs. 2012;7:57–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2011.00282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A-G, Buchner A. G* Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:175–191. doi: 10.3758/BF03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson CJ. An effect size primer: a guide for clinicians and researchers. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2009;40:532–538. doi: 10.1037/a0015808. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MG, Griffin DJ, Svetieva E, Maroulis A. Nonverbal elements of the voice. In: Kostić A, Chadee D, editors. The social psychology of nonverbal communication. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2015. pp. 92–113. [Google Scholar]

- Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59:255–263. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.3.M255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George J, Long S, Vincent C. How can we keep patients with dementia safe in our acute hospitals? A review of challenges and solutions. J R Soc Med. 2013;106:355–361. doi: 10.1177/0141076813476497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendlmeier I, Bickel H, Hessler JB, Weber J, Junge MN, Leonhardt S, Schäufele M. Demenzsensible Versorgungsangebote im Allgemeinkrankenhaus. Repräsentative Ergebnisse aus der General Hospital Study (GHoSt) [Dementia friendly care services in general hospitals. Representative results of the general hospital study (GHoSt)] Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2018;51:509–516. doi: 10.1007/s00391-017-1339-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessler JB, Schäufele M, Hendlmeier I, Junge MN, Leonhardt S, Weber J, Bickel H. The 6-item cognitive impairment test as a bedside screening for dementia in general hospital patients: results of the General Hospital Study (GHoSt) Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32:726–733. doi: 10.1002/gps.4514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessler JB, Schäufele M, Hendlmeier I, Junge MN, Leonhardt S, Weber J, Bickel H. Behavioural and psychological symptoms in general hospital patients with dementia, distress for nursing staff and complications in care: results of the General Hospital Study. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2018;27:278–287. doi: 10.1017/S2045796016001098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudelson P, Kolly V, Perneger T. Patients’ perceptions of discrimination during hospitalization. Health Expect. 2010;13:24–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2009.00577.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummert ML. Stereotypes of the elderly and patronizing speech. In: Hummert ML, Wiemann JM, Nussbaum JF, editors. Interpersonal communication in older adulthood: interdisciplinary theory and research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1994. pp. 162–184. [Google Scholar]

- Hummert ML, Ryan EB. Toward understanding variations in patronizing talk addressed to older adults: psycholinguistic features of care and control. Int J Psycholinguist. 1996;12:149–169. [Google Scholar]

- Hummert ML, Shaner JL, Garstka TA, Henry C. Communication with older adults: the influence of age stereotypes, context, and communicator age. Hum Commun Res. 1998;25:124–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.1998.tb00439.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keller AC, Bergman MM, Heinzmann C, Todorov A, Weber H, Heberer M. The relationship between hospital patients’ ratings of quality of care and communication. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26:26–33. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzt083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo TK, Li MY. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med. 2016;15:155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuemmel A, Haberstroh J, Pantel J. CODEM instrument. Developing a tool to assess communication behavior in dementia. GeroPsych. 2014;27:23–31. doi: 10.1024/1662-9647/a000100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y-E, Norman IJ, While AE. Nurses’ attitudes towards older people: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50:1271–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index: a simple index of independence useful in scoring improvement in the rehabilitation of the chronically ill. MD State Med J. 1965;14:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathôt S, Schreij D, Theeuwes J. OpenSesame: an open-source, graphical experiment builder for the social sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2012;44:314–324. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0168-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehl MR, Carey AL (2014) The iEAR 2.1 (electronically activated recorder for the iPod touch): a researcher’s guide. OSF Publishing. https://osf.io/2tx35/

- Mukadam N, Sampson EL. A systematic review of the prevalence, associations and outcomes of dementia in older general hospital inpatients. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23:344–355. doi: 10.1017/S1041610210001717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedone C, Ercolani S, Catani M, Maggio D, Ruggiero C, Quartesan R, Senin U, Mecocci P, Cherubini A. Elderly patients with cognitive impairment have a high risk for functional decline during hospitalization: the GIFA Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:1576–1580. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.12.1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel Y. Lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling and more. J Stat Softw. 2012;48:1–36. doi: 10.18637/jss.v048.i02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan EB, Hummert ML, Boich LH. Communication predicaments of aging: patronizing behavior toward older adults. J Lang Soc Psychol. 1995;14:144–166. doi: 10.1177/0261927X95141008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sachweh S. Granny darling’s nappies: Secondary babytalk in German nursing homes for the aged. J Appl Commun Res. 1998;26:52–65. doi: 10.1080/00909889809365491. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Savundranayagam MY, Sibalija J, Scotchmer E. Resident reactions to person-centered communication by long-term care staff. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2016;31:530–537. doi: 10.1177/1533317515622291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schermelleh-Engel K, Moosbrugger H, Müller H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. MPR Online. 2003;8:23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt T, Schütte W (2015) FOLKER Transkriptionseditor für das „Forschungs- und Lehrkorpus gesprochenes Deutsch“(FOLK). Transkriptionshandbuch. [FOLKER transcription editor for the research and teaching corpus of spoken German (FOLK). Transcription manual]. http://agd.ids-mannheim.de/download/FOLKER-Transkriptionshandbuch_preview.pdf. Accessed 12 Au 2019

- Sousa VD, Rojjanasrirat W. Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: a clear and user-friendly guideline. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17:268–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tropea J, LoGiudice D, Liew D, Roberts C, Brand C. Caring for people with dementia in hospital: findings from a survey to identify barriers and facilitators to implementing best practice dementia care. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29:467–474. doi: 10.1017/S104161021600185X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KN. Improving outcomes of nursing home interactions. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29:121–133. doi: 10.1002/nur.20117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KN, Herman RE. Linking resident behavior to dementia care communication: effects of emotional tone. Behav Ther. 2011;42:42–46. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams K, Kemper S, Hummert ML. Improving nursing home communication: an intervention to reduce elderspeak. Gerontologist. 2003;43:242–247. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.2.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KN, Boyle DK, Herman RE, Coleman CK, Hummert ML. Psychometric analysis of the emotional tone rating scale: a measure of person-centered communication. Clin Gerontol. 2012;35:376–389. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2012.702648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KN, Perkhounkova Y, Jao Y-L, Bossen A, Hein M, Chung S, Starykowicz A, Turk M. Person-centered communication for nursing home residents with dementia: four communication analysis methods. West J Nurs Res. 2017;40:1012–1031. doi: 10.1177/0193945917697226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zieschang T, Dutzi I, Müller E, Hestermann U, Grünendahl K, Braun AK, Hüger D, Kopf D, Specht-Leible N, Oster P. Improving care for patients with dementia hospitalized for acute somatic illness in a specialized care unit: a feasibility study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22:139–146. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209990494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.