Abstract

Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is associated with viral malignancy, related to HIV-AIDS. With a wide geographical discrimination in its occurrence, Asian countries shows low to moderate prevalence with higher occurrence in some particular areas. India is one of the largest countries in Asia, having various geographical and cultural variations where KSHV has been considered as an unthinkable entity to cause any of its associated disease. India has been reported as a low prevalent zone for KSHV malignancy till date. Also there are no reports so far, describing the occurrence pattern of this malignancy. So this review approaches towards figuring out the tendency of prevalence pattern of this malignancy and associated risk factors found to be present in Indian population. From this study it is revealed that, KSHV related malignancy is a relatively newly reported and emerging disease in India and may exist in hidden pockets throughout India in association with tuberculosis. India shows prevalence in HIV-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma in regions where socially discriminated LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) groups, unprotected sexual behavior and heterosexuality are the important risk factors for sexually transmitted viral diseases. Anti-retro viral therapy is not sufficient to combat the virus and may act adversely. On a note regarding the clinical representations of Kaposi’s sarcoma, oral, mucosal, pleural and abdominal involvements are observed in worst cases and these can be considered as the main manifesting criteria for this malignancy among Indians.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13337-020-00573-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: KSHV, India, HIV, TB, Risk factors

Introduction

Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is a geographically confined pathogenic member of herpes virus family. KSHV is associated to different malignancies like, Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS), primary effusion lymphoma (PEL), HHV-8-associated multicentriccastleman’s disease (MCD) and KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome [31, 62]. KSHV, the ninth reported member of Herpesviralis order, taxonomically belongs to the Herpesviridae family and subfamily Gammaherpesvirinae, is a double stranded DNA virus, also known as the Human gammaherpesvirus 8 (HHV-8). KSHV possess a biphasic life cycle (latent and lytic phase) both of which are associated with different malignancies. During its latency, the viral genome is maintained in an episome form inside host nucleus and latency associated nuclear antigen (LANA) is the key player which helps to maintain the latency and also regulate the transcriptional activity of several host genes. During lytic cycle KSHV produce successful infective viral particles. There are several cellular homologues has been produced by KSHV during the both phases of its life cycle, which helps the virus to survive, replicate and modulate the host cell machineries which leads to oncogenesis [67].

KSHV related cancers are not very ubiquitous in nature and this virus shows uneven distribution throughout the world [47]. The majority of reports for KSHV infection comes from developed countries like USA, Sweden, Norway, and other parts of Europe whereunder-developed countries were reported to have low prevalence except Africawhich is considered as the main origin of this viral malignancy. The epidemiological justification for the discrete nature of occurrence of this viral malignancy throughout the world has not been revealed well due to lack of population based study and patient sample availability. The main zones of occurrence of this malignancy are the African and Mediterranean continents whereas Asian countries come under moderate to low prevalence zones [14]. Southern Asian countries, mainly China, Japan and Cambodia show moderate to high prevalence (ranging from 10 to 56%). China is the most studied zone in Asia, where Taiwan and Xinjiang regions show maximum KSHV seropositivity. China shows variations in KSHV prevalence depending on its diverse cultural, ethnic, and life style patterns [18, 61, 72]. Other south Asian countries like, Srilanka, Thiland, Vietnam and Malaysia shows low prevalence of KSHV [1]. Notably, Cambodia represents prevalence of about 50% among both men and women with average age group of 13. This prevalence is highly localized and can be characterized with distinctive poor socioeconomic and hygienic conditions among the rural populations. Thus this area can be said as the high risk zone of Asia for KSHV malignancy [50].

Middle, middle-east and west Asian countries show moderate to low prevalence of KSHV based on different indicative factors for example, ethnic variations of Jewish inhabitants in Israel show higher incidence as 9.9% for overall and 22% for HCV-infected subjects, and infection transmits mainly from spouse to spouse and mother to child. Similarly Ethiopian migrants in Israel show a high frequency, 22%, of KSHV infection. Interestingly, Endogenous inhabitants and students of pre-marital age show significantly lower infection of this virus [38, 51]. A recent report shows thatKSHV prevalence also associated with multiple myeloma as found in Jordan [25]. This indicates a much intense role of this virus in cancers, though not all varieties of cancers are studied yet for the presence of KSHV. Blood donors in Turkey and organ transplant patients in Iran and Saudi Arabia shows low (5.3%) to moderate (18–25%) KSHV prevalence [4, 5, 27]. Of note, blood donation and organ transplantation both involves mixing of blood in donors and recipients. Therefore, it can be conferred that such mixing actually is responsible for transfer of KSHV to donor from recipient. The status of the donor and recipients, therefore, must be checked.

This discrepancy of occurrence, even within a continent, is due to several factors like, difference in the sensitivity of assay methods applied for detection of KSHV, ethnicity and different genetic factors among population, poor socioeconomic conditions, HIV-AIDS, cancers, homosexuality, intravenous drug use, and organ transplantation etc which might control the pathogenesis. Therefore if the infectionpattern of KSHV among Asian population cannot be understood well then it will remain ignored and might be evolved and appeared as sudden epidemic outbreak in due course of time [71]. India is the most diversified country in Asia in terms of its huge geographical variation and ethnicities next to China. Though it doesn’t come under prevalent zone of KSHV related malignancies but several reports are coming out in recent days from different parts of India indicating its emerging nature. Thus this review aims to figure out the pattern of KSHV related malignancy in India which might help to understand the total scenario and therefore concerns regarding KSHV associated diseases among Indians can be addressed properly.

India shows prevalence in AIDS related Kaposi’s sarcoma

AIDS and KSHV are much related and different types of KSHV related malignancies are mostly associated with HIV [49]. Parallely in HIV associated cancers, KS and PEL are much common and approximately 4% of HIV related non-hodgkin’s lymphoma is PEL [49]. A study shows 481.54 people per 100,000 HIV positive ones harbour Kaposi’s sarcoma [36]. According to the current epidemiology, Kaposis’ sarcoma is of four different types, classical form, transplant-associated, African or the endemic form, and AIDS-related or epidemic form [22]. Considering the impact of the co-existence of HIV-1 and KSHV, there are several reports suggesting the molecular interactive role of both the viruses in the pathogenesis of diseases. Both KSHV and HIV-1 can increase the susceptibility of host cell for infection, increase viral replication, enhances infectivity of the virus, angiogenesis process and modulation of host–pathogen signaling pathways in a bidirectional talk between them. This cross talk happens between KSHV and HIV-1 by direct interaction of different latency as well as lytic associated KSHV proteins and HIV-1 associated Tat (transcriptional activator), LTR (Long terminal region), and CD4+ T cells [63]

If we globally review the time trend of the occurrence of HIV-AIDS and Kaposis’ sarcoma then it can be said that HIV have been found to occur in pre 1980s and Kaposis’ sarcoma appeared after 1980s. Both of these became contemporary emerged as a sudden occurrence and became epidemic [54]. After the occurrence of both of these entities with their epidemic emergence in the African and Mediterranean countries, they have started to appear in Asian continents too. But in such countries AIDS became the epidemic one, whereas reports of the KSHV associated malignancies are less. Similar pattern was observed in India also, the first reported case of HIV from India came from Chennai, Tamil Nadu in 1986 [60] and the first report of KSHV malignancy was in 1993 [56]. During the periods of HIV and KSHV occurrence, the prevalence of HIV was increased and India became the third largest HIV epidemic region in world and an HIV dominated country in Asia [32]. But in terms of KSHV, as it is not widely revealed, it has been denoted as a rare entity in India based on a few case reports only. HIV-AIDS was unthinkable for Indian population, when it became epidemic in USA few years ago before any single case was reported in India. Actually, the first case report of HIV-AIDS in India was revealed in an article of BBC news, and this virus was detected by chance for the sake of research only. After that population based study begun and it was found to be epidemic one. Keeping this in mind, there is a fair chance that KSHV associated malignancies may also start a sudden emergence as would be shown in reports, because very low population based studies among the risk groups and general population have been available in public domain. Without detailed population-based detection study for KSHV, it cannot be said with confidence that this virus is rarely found in Indian people.

Considering KSHV associated malignancy pattern specifically in India, reports of HIV associated KSHV malignancies have been revealed from different regions of Indian sub-continent. From 1993 to 2019, about 25 cases of Kaposi’s sarcoma have been reported. On average, there is one report of KS is found each year and all of those cases were seropositive for HIV infection also, specifically HHV-1 infection [10]. Currently HIV is approximately 0.22% prevalent among Indian adults and 2.1 million people are living with HIV [45]. As mentioned above, India shows prevalence of AIDS associated Kaposi’s sarcoma compared to the other forms. It indicates that, HIV infected groups are at high risk of HHV-8 infections also. Thus survivors of HIV infections have high risk of getting KSHV infection and conversely, detection of KSHV infection can be considered as the initial representation of HIV infection in Indian scenario [53, 66, 70].

Non HIV associated Kaposi’s sarcoma is rarely found throughout the world and the same pattern is followed in India also. Some reports claim it to be associated with female patients, but some others report for male patients also [26, 28, 34]. Primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) is another malignancy associated with HHV-8. It is a kind of body cavity effusion based non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) associated with KSHV and HIV. HIV associated non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is common in India but association of KSHV with it, is reported in one case report only. Interestingly, there is a rare form of PEL, denoted as extra cavitary primary effusion lymphoma has found to be associated with KSHV and HIV. Castleman’s diseases have also been reported from India but KSHV association has not been reported for that, thus the probability of KSHV association with multi centric castleman’s diseases cannot be stated [2, 21, 42]. But all these other forms of KSHV malignancies are very rare compared to KS from India.

After reviewing the pattern of KSHV in India, it is confirmed that the emergence of KSHV started along with or better said, later to HIV emergence, HIV-AIDS became the main focused area in Indian populations but its association with KSHV malignancies are not revealed well. HIV patients in India are treated with single directional approach not considering other risk factors like KSHV, associated with it. To reveal the real story about this virus and providing better survival opportunities to the AIDS patients in India, a longitudinal study based on screening among HIV positive high risk groups must be done, but to have a definite and compact idea about its spread and emerging pattern, independent focus on KSHV is needed along with its unusual forms of malignancies.

If we consider the molecular interaction of HIV and KSHV, it is quite clear that interaction of these two entities plays important role in the oncogenic progression.

Tuberculosis is the main co-existing agent apart from HIV

Tuberculosis (TB) is the most common opportunistic infection in India. According to Indian government’s TB report published in 2018, India ranks second in HIV-associated TB and accounts for 10% of cases worldwide. KS patients from India have been reported with previous history of tuberculosis which has been reactivated from the latent state during HIV associated KS, where incomplete TB treatment acts as influencing factor. Conversely Tuberculosis may also develop during the period of HIV infection and subsequent development of KS [52]. The HIV-KS-TB patients are reported of to be provided with combined treatment of 1st line or 2nd line anti-tuberculosis and antiretroviral therapy (ART). Prolonged application of ART may result in the development of a clinical complication known as immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) in which the body may restore the previous subclinical condition or may deteriorates the present pathogenic condition. This rare clinical condition may be one of the causes of association of TB with HIV associated KS among Indian patients [37, 41].

Association of TB in HIV patients is a common scenario worldwide, but its association with KSHV is not reported as a common incident. Interestingly association of tuberculosis with KSHV has been found in HIV negative individuals also, indicating its solo role in KSHV malignancy without the involvement of HIV infection [12, 15]. Also different types of tuberculosis have been reported to be associated with KSHV, like abdominal and pulmonary tuberculosis and involvement of this visceral manifestation is a worst scenario for KSHV malignancy in India [15]. The exact pathological role of TB in development of KSHV infection and pathogenesis needs further research. A recent study in Africa shows high mortality of HIV patients is associated with high KSHV viral load with suspected TB but without any microbiological confirmation of the bacteria. As KS symptoms are so much similar with TB, association of KSHV is suspected in case of TB and vice versa and which may also increases the chances of misunderstanding and confusion, which should be avoided with proper detection in every case [11]. TB is a real threat to India and KSHV has been reported as a co-existing factor with almost all the HIV patients in India [56]. Therefore in Indian perspective of KSHV malignancy, TB must be considered as a risk factor and TB-AIDS-KS may be classified as a new form of Kaposi’s sarcoma.

Sexual behavior of the patients with their socio-economic conditions play an important role with LGBT populations being in real threat

Though the percentage of women is high for HIV positivity in India, but the same is not true for KSHV malignancy. Though not concluded in Indian scenario, it is reported worldwide that KSHV infection predominates in males. It is suspected that hormones play an important role for this gender discrepancy in KS [69]. Interestingly, a recent report shows that HIV positive male patients have been identified with HHV-8 infection, and the major route of transmission of this virus is heterosexual [44]. Though KSHV malignancies are common in homosexual men, heterosexuality dominates among Indians. The main route of transmission is by high risk sexual behaviors like unprotected insertive, receptive and anal intercourse, where the patients belong to sex worker, driver, business persons and laborers by profession who are exposed to public interactions and engaged with multiple sexual partners. Few intravenous drug users are reported and in case of married women, their husbands are reported to be addicted to intravenous drugs [35]. Only few cases of blood transfusion recipients are reported to harbor KSHV [52]. As most people have denied or refused the discussion about their sexual behavior it creates lack of information and the complete scenario remains covered in dark. Therefore, any discussion must be confidential and be performed by trained counselor in this regard. Considering the increasing occurrence of KSHV related malignancies, importance should be given emphasizing the detection of KSHV, considering the socio economic condition, age, sexual status, occupational status etc. The main reason for this is, in maximum cases reported from India, scientifically specific and proper report for HHV-8 detection in the patient sample is not done because of the social and financial limitations [70].

It has been noticed that HIV-KSHV patients mainly come from a socioeconomic background, which is not well accepted socially in India. In this regard, a distinct group of population i.e. LGBT group (Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender population) are socially discriminated and it is found that this group of population shows high risk of HIV-AIDS and sexually transmitted diseases, hence comes under high risk groups of KSHV malignancies. The problem is, this group of population is ill reported in terms of health issues and treatment facilities due to their social status which is not prioritized by the government. Though transgender has been legalized as third gender in India, much more legal actions and education is needed in this field so that their health issues could be reported well [64]. The physicians, NGO and drug detention centers should come forward for this. Research programmes focused on the human rights of these people along with the medical interventions should be carried out which will reveal the cohort of KSHV malignancy among AIDS concerned LGBT groups in India [29, 59].

Geographical scenario, environmental factors along with parasitic infection makes a great deal with KSHV

The occurrence of KSHV related malignancies and its seropositivity seemed to appear in a cohort forming manner. Within a highly prevalent continent also, it seems to be geographically isolated in particular areas [47]. KSHV malignancy reports in India are mainly reported from western cost, mainly Mumbai, Chennai, Gujrat, and Karnataka. Few cases are reported in north and north-east India, Delhi and Manipur also. 26.06–33.3% KSHV seropositive HIV-1 positive male patients were detected from north India [3, 44, 56]. In south India the seropositivity rate is 4.5%. No case report has been found from eastern part of India but this zone might bear a high risk as it is highly cancer prone area and also located in close proximity with the east and south East Asian continents where KSHV found to be frequent. The south and south western parts of India are in close proximity with coastal regions of central and east Africa and flooded with immigration, trade interactions and travelling therefore are in very high risk of having KSHV infection as the central and east Africa, which are two of the highest prevalent zone of KSHV malignancies.

Along with afore discussed risk factors, several reports suggest some environmental factors responsible for KSHV infection. Volcanic clay soil containing aluminum and iron as major components contribute to the prevalence of KS infections among rural Africans [46, 57, 58]. In India also, black and red soils are reported in regions of KSHV infections. Specifically, the states of south western parts, where KSHV related malignancies have been reported mostly, the soil is black and red type. Black soil is mainly made up of volcanic rocks and lava, whereas the red soil is named so for its high iron content. Though the exact role of aluminium, or iron, or volcanic rocks overall, is not justified in any report of KSHV infection and/or malignancy, the geographic conditions cannot be overruled as all mineral nutrients eventually come from soil and physical exposure to such kind of soil may also play certain role in the KSHV related malignancy. These environmental factors may be co-related as the enhancing factors for KSHV malignancy, but extensive studies are required for that.

KS has also been reported to be associated with blood sucking insects or arthropods which mainly are those related to malaria. This type of infection weakens the host immune system and can contribute for having KSHV infections. Moreover the insect bite causes a puncture in skin and the blood capillary underneath; therefore and the application of human saliva in the insect bite area in child is a usual home remedy used for getting relief of itching, which might transmit this viral spread through that tiny puncture [7, 68]. Epidemiological study shows that Sub-Saharan Africa which is prevalent zone for KSHV infection is also endemic for malaria. Proportionate KSHV seropositivity and malarial vector density has been found from Italy. There are several study shows the molecular link of malarial infection and KSHV oncogenesis. Subsequent malarial infection leads to anemia and impaired B/T cell immunity which leads to KSHV tumorigenesis by enhancing the reactivation and replication of the virus. Quinine which is the main medicine for malaria has been reported for its immune suppressive function which provoke KSHV to replicate. The anemic condition can reactivate KSHV by tissue hypoxia. Malarial parasite infected RBC (IRBC) express pfEMP-1 (Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1) and binds with specific domain of CD-36 host endothelial cell receptor, this binding is essential for the virulence of the parasite. Interestingly a recombinant peptide derived from CD36 pfEMP receptor, when cross links with CD36 receptor, it can activate KSHV lytic reactivation. Thus it is clear that malarial infection plays a molecular impact on KSHV reactivation [16, 24]. On this note, it must be considered that a wide part of India is surrounded by the Indian ocean and this sub-continents have been well reported for the prevalence of infectious diseases like malaria, chikungunya, encephalitis and dengue from ancient time to current century [43, 57]. The total geographical distribution of KSHV associated malignancy has been described in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Geographical distribution of KSHV related malignancy in India

Clinicopathological conditions

The case reports of KS patients from India clinically presented with cutaneous violaceous patches, plaques, nodules and blanching or non-blanching lesions over different body parts; mainly over the trunk, including upper and lower limbs, chest, face and genital organs. In most of the cases, lesions appears on the trunk in the beginning for the onset of the disease, and later, spread over the upper and lower extremities, or sometimes reverse [17, 40, 55, 66]. The lesions appear with a Christmas tree pattern or sometimes with cobble stone appearance. They might be tender or non-tender to touch with purple, pink or bluish in colour and with 0.2–7 cm in diameter for each [8, 10].

In Indian perspective of KS, oral, facial and mucosal involvement is very common and can appear as the solo clinical presentation of the malignancy. Indian patients show origin of lesions initially in hard palate of mouth or in the oral mucosa, then in soft palate gingiva and lastly in dorsal tongue as reported till date. Indian study reports 61.5% cases of involvement of both cutaneous and oral mucosa and 38.46% of only cutaneous involvement [6, 48]. Interestingly presence of KS nodules on the eyelid has been found [30]. Thus oral as well as facial lesions or nodules can be used as an primary identifying factor for detecting KSHV related malignancy [6, 30].

Apart from the above symptoms common fever, joint pain, diarrhea, weight loss etc. are found as other common symptoms associated with KS. Routine blood profiles like the hemogram analysis and serum biochemistry shows no remarkable change but CD4 count has been found to be low in some cases with damaged renal function and low hemoglobin percentage [10, 17]. Previously it is described that KSHV reactivation has been reported to cause anemic condition. Biopsies from lesions and their histological reports show spindle cell proliferation with slit like congested capillaries [52]. Abnormalities like, pleural effusion, chest fibrosis, post inflammatory changes in lungs, fatty liver with multiple lesion, hepatitis B positivity, liver edema on GI tract, lesion in spleen etc. are the indicative features of metastasis [13, 56, 70]. KS has been found to be a vascular neoplasm, thus with the progression of the diseases, involvement of vascular endothelial linings, lymphatic channels, lymph nodes, gastrointestinal tract and genitalia indicates towards the metastatic tendency with symptoms like lymphadenitis, lymphadenopathy and lymphatic edema [33]. Notably pulmonary involvement is associated with the most aggressive cases with massive pleural effusion [8].

Several interacting infectious agents have been found along with KS whereas tineacorporis and malignant schwannoma in right palm in the same limb of KS appearance has been found as a co-associated pathological conditions among Indians [9, 23]. Molluscumcontagiosum, with past tuberculosis history in a HIV positive patient has been found to be associated with KS showing several small to large central umbelicated facial lesions [65]. There is also a case report of thrombocytopenia to be associated with Kaposi’s sarcoma [55]. VDRL (venereal diseases research laboratory) test has been found normal, whereas hepatitis B antigen reactivity has been found positive in some cases of KS [3, 10].

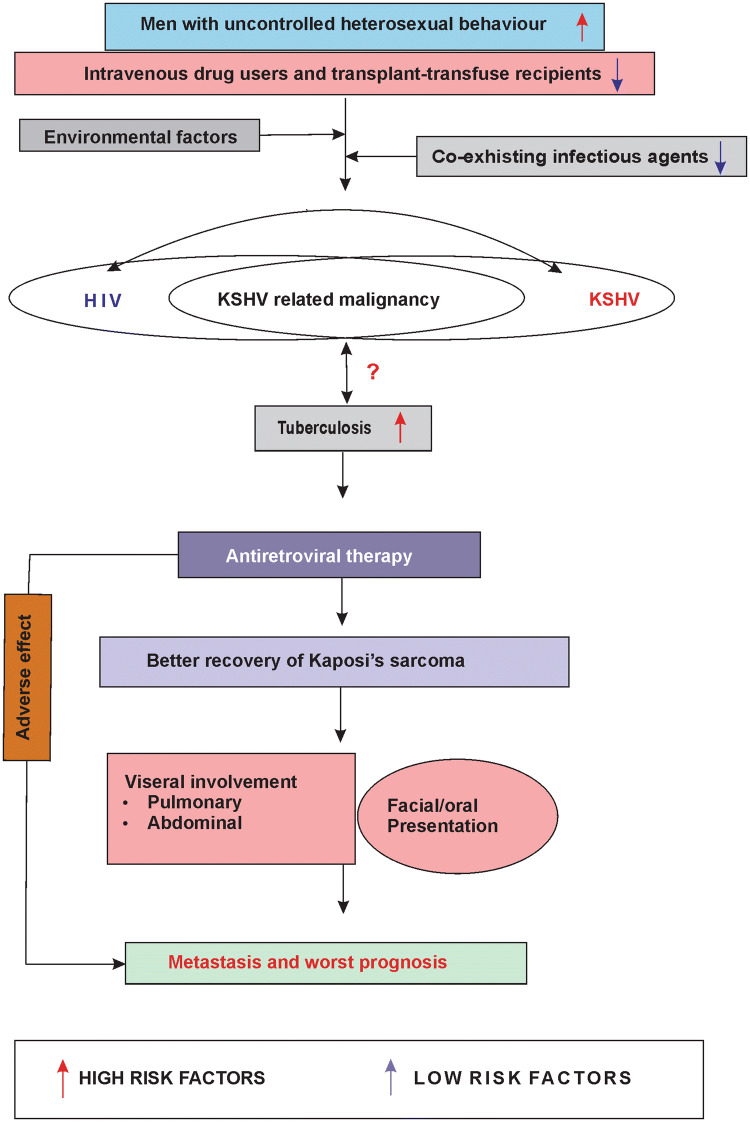

These findings indicate a clear clinical pattern of KSHV malignancy along with its related pathological co-factors (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Clinical pattern of KSHV associated malignancy in India showing the diseases manifestation along with the risk factors

Retroviral therapy is not enough to make up the malignancy

Combined ART and highly active antiretroviral (HAART) therapies, along with 1st line chemotherapeutic drugs (like liposomal doxorubicin), are used as the local therapeutic strategy against KSHV malignancy in India. Intravenous paclitaxel has also been administered but as 2nd line drug for its adverse effects [19]. Other treatment modalities include intralesional vincristine, bleomycin, alpha-interferon etc. [8]. It has been observed in almost all the cases that when individuals suffering from HIV associated KS, have been applied with HAART treatments the KS lesions have appeared to be decreased. Thus direct antiviral effects of the chemotherapeutic drugs on regression of KS incidence can be linked and early detection of KSHV with initiation of HAART is required in that case. Though HAART shows positive results, it should be noted that relapse of KS has been observed in several cases after few months of completion of treatment [10]. As HHV-8 persist in latent phase inside the host cell and modulates the cellular signaling to cause oncogenesis, drug induced KSHV reactivation mechanisms within the host cell must be kept in mind for new therapeutic approaches for hitting the viral latency and therefore, to combat relapse. Only anti-retroviral therapy (ART) or HAART is not sufficient enough for treating KS completely.

Concluding remarks

This review intended to embrace the total scenario of HHV-8 related malignancies in Indian sub-continent. It describes the pattern of KSHV malignancy among Indian population, as new emerging member which may exist as hidden pockets. It aims towards revealing this neglected malignancy in-terms of HIV-TB-KSHV association and its considerable determining factors which gives a new sight to analyze this entity in detail irrespective of its statistics of occurrence so far (Supplementary fig. I). Through the detailed discussion on the published reports, it is clear that incidence of AIDS associated malignancy specifically KSHV associated ones must be anticipated in Indian perspective with new trends for the AIDS patient survival management should be planned. KSHV malignancies should be concerned parallely and along with HIV, tuberculosis, and Non-Hodgkins lymphoma and other co-existing factors in Indian patients. TB associated KSHVcan be classified as a distinct type of KSHV related malignancy where application of ART has been found as possible risk factor for relapse.

As it has been observed from the above study that, Indian KSHV associated malignancy is co-infected with various pathogens, mainly HIV-1, TB and also there are high chance of co-existence and risk of malarial parasitic infection, the impact of this association in KSHV oncogenesis must be analyzed well. Several reports suggest that co-infection may exert beneficial as well as harmful effect in disease progression. Though high risk of mortality is expected in HIV-TB or HIV-KSHV co-infection, there are several other deleterious effects reported like, increased viral load leading to increased chance of transmission, drug interaction and impairment in diagnosis etc. Role of TB is not explored in KSHV malignancy, but bacteria can potentially increases viral infectivity in low viral load condition by binding to multiple virion and adherence to host cell. Moreover bacteria can limit abortive viral infection by inducing recombination between two different virus [20, 39]. Co-infection biology must be an important part for analyzing KSHV malignancy in India otherwise KSHV co-infection with HIV-TB will remain as orthodox phenomena.

Though publication biasness is a considerable factor affecting proper documentation and registration, these are needed along with survival and prognosis data. Sometimes, the same patient has been found to be registered and reported differently, by different healthcare professionals/centers, which may create confusion [17, 70].

Along with the well reported southern parts, the eastern and northeastern parts of India should be kept under immense observation, because these parts have been known for specific ethnicity and have been exposed to several rare and infectious diseases along with various cancers, specifically AIDS and the life style has a great impact over their disease susceptibility.

This is the high time to think about the virus in terms of its pathogenesis, detection, interaction with host and its specific treatment modalities apart from the available ones which are not promising to control its spread. Awareness programmers must be needed to concern public and health experts about these particularly rare diseases, their emerging patterns and risk factors. The campaign should focus on proper management considering the socioeconomic conditions and sexual backgrounds among high and as well as low risk groups, and it should try to provide an open counseling based discussion among the socially isolated populations with unusual sexual characteristics.

Researchers must focus on development of easy detection methods based on opportunities, which are economically favorable and can use genetic and molecular factors associated with this ill-undiagnosed viral oncogenesis associated with known epidemic diseases like HIV and TB in India, which is currently not possible due to financial constraints. The latency associated protein LANA/ORF73 (latency associated nuclear antigen) and lytic associated viral replicative protein K8.1 are the major markers for KSHV detection. Detection methods should identify these markers from KSHV DNA from patient samples like blood, serum, saliva and tissue biopsy. Viral load can be determined by analyzing K8.1 in RTPCR and other antibody based assay targeting those markers may be used for confirmation of the malignancy status [38] In search of the development of this malignancy in India, immunosuppression, sexual behavior, geographical and environmental factors and interactive infectious agents can be easily pointed out to be associated with the disease. But concerning the genetic justification, common markers like HLA (human leukocyte antigen) allotype variation and interleukin-6 polymorphism should also be considered. Immunohistochemistry based assay or polymerase chain reaction for viral DNA/RNA are the confirmatory methods for KSHV presence, therefore all the HIV seropositive patients should be kept under clinical investigation with those methods performed on them. Diagnostic labs, hospitals etc. must be equipped with those methods for early detection. In terms of treatment facilities, the physicians and healthcare experts should be conscious enough about providing the better treatment opportunities as well as proper and consistent follow up treatments of the patients is needed to get a complete track report of this malignancy.

The gradual but limited exploration of KSHV among Indian populations indicates a hidden existence in some pockets of India and presenting a high-risk of its sudden emergence and thus it must be considered as a rare but not to be ignored fetal entity.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Overallcharacterization of Indian KSHV associated malignancy (TIFF 1038 kb)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mr. LaltuHazra, regarding his general laboratory help and CSIR for their financial assistance byCSIR SRF fellowship (Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, Govt. of India, Senior Research Fellowship).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Piyanki Das, Email: piyankidas.rs@visva-bharati.ac.in.

Nabanita Roy Chattopadhyay, Email: mailnabanita@gmail.com.

Koustav Chatterjee, Email: koustavchatterjee.rs@visva-bharati.ac.in.

Tathagata Choudhuri, Email: tathagata.choudhuri@visva-bharati.ac.in.

References

- 1.Ablashi D, Chatlynne L, Cooper H, et al. Seroprevalence of human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8) in countries of Southeast Asia compared to the USA, the Caribbean and Africa. Br J Cancer. 1999;81(5):893–897. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Acharya VK, Rai S, Shirgavi S, Pai RR, Anand R. Multicentric castleman’s disease: “A rare entity that mimics malignancy”. Lung India Off Organ Indian Chest Soc. 2016;33(6):689–691. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.192864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agarwala MK, George R, Sudarsanam TD, Chacko RT, Thomas M, Nair S. Clinical course of disseminated Kaposi sarcoma in a HIV and hepatitis B co-infected heterosexual male. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6(4):280–283. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.160271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Dayel A, Guella A, Alzahrani AJ, et al. Increased seroprevalence of human herpes virus-8 in renal transplant recipients in Saudi Arabia. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20(11):2532–2536. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfi058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Altuglu I, Yolcu A, Ocek ZA, Yazan Sertoz R, Gokengin D. Investigation of human herpesvirus-8 seroprevalence in blood donors and HIV-positive patients admitted to Ege University Medical School Hospital, Turkey. Mikrobiyoloji bulteni. 2016;50(1):104–111. doi: 10.5578/mb.10751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arul AS, Kumar AR, Verma S, Arul AS. Oral Kaposi’s sarcoma: sole presentation in HIV seropositive patient. J Nat Sci Biolmed. 2015;6(2):459–461. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.160041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ascoli V, Senis G, Zucchetto A, et al. Distribution of ‘promoter’ sandflies associated with incidence of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma. Med Vet Entomol. 2009;23(3):217–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2009.00811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Behera B, Chandrashekar L, Thappa DM, Toi P, Vinod KV. Disseminated Kaposi’s sarcoma in an HIV-positive patient: a rare entity in an Indian patient. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61(3):348. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.182466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhagat U, Sharma A, Marfatia YS. Violaceous papulonodular lesions in an AIDS case. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2008;29:51–53. doi: 10.4103/0253-7184.42722. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhatia R, Shubhdarshini S, Yadav S, Ramam M, Agarwal S. Disseminated Kaposi’s sarcoma in a human immunodeficiency virus-infected homosexual Indian man. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83(1):78–83. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.193612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blumenthal MJ, Schutz C, Barr D, et al. The contribution of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus to mortality in hospitalized human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients being investigated for tuberculosis in South Africa. J Infect Dis. 2019;220(5):841–851. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castro A, Pedreira J, Soriano V, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma and disseminated tuberculosis in HIV-negative individual. Lancet. 1992;339(8797):868. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90308-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chandan K, Madnani N, Desai D, Deshpande R. AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma in a heterosexual male—a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2002;8(2):19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chatlynne LG, Ablashi DV. Seroepidemiology of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) Semin Cancer Biol. 1999;9(3):175–185. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1998.0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen YJ, Shieh PP, Shen JL. Orificial tuberculosis and Kaposi’s sarcoma in an HIV-negative individual. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25(5):393–397. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2000.00672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conant K, Kaleeba J. Dangerous liaisons: molecular basis for a syndemic relationship between Kaposi’s sarcoma and P. falciparum malaria. Front Microbiol. 2013 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dhote A, Umap P, Shrikhande A. Fine needle cytology of Kaposi’s sarcoma in heterosexual male. Int J Res Med Sci. 2014;2(2).

- 18.Dilnur P, Katano H, Wang ZH, et al. Classic type of Kaposi’s sarcoma and human herpesvirus 8 infection in Xinjiang, China. Pathol Int. 2001;51(11):845–852. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2001.01293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dongre A, Montaldo C. Kaposi’s sarcoma in an HIV-positive person successfully treated with paclitaxel. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75(3):290–292. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.51254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erickson AK, Jesudhasan PR, Mayer MJ, Narbad A, Winter SE, Pfeiffer JK. Bacteria facilitate enteric virus co-infection of mammalian cells and promote genetic recombination. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23(1):7788.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gatphoh ED, Zamzachin G, Devi SB, Punyabati P. AIDS related malignant disease at regional institute of medical sciences. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2001;44(1):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goncalves PH, Ziegelbauer J, Uldrick TS, Yarchoan R. Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus-associated cancers and related diseases. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2017;12(1):47–56. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gopala A, V Ramana Reddy G. Kaposi’s sarcoma in a follow-up patient of malignant schwannoma after seroconversion. Indian J Surg. 2004;66:110–112. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gowda NM, Wu X, Kumar S, Febbraio M, Gowda DC. CD36 contributes to malaria parasite-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine production and NK and T cell activation by dendritic cells. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e77604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ismail SI, Mahmoud IS, Salman MA, Sughayer MA, Mahafzah AM. Frequent detection of human herpes virus-8 in bone marrow of Jordanian patients of multiple myeloma. Cancer Epidemiol. 2011;35(5):471–474. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jakob L, Metzler G, Chen K-M, Garbe C. Non-AIDS associated Kaposi’s sarcoma: clinical features and treatment outcome. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(4):e18397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jalilvand S, Shoja Z, Mokhtari-Azad T, Nategh R, Gharehbaghian A. Seroprevalence of Human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) and incidence of Kaposi’s sarcoma in Iran. Infect Agents Cancer. 2011;6:5. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-6-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jan RA, Koul PA, Ahmed M, Shah S, Mufti SA, War FA. Kaposi sarcoma in a non HIV patient. Int J Health Sci. 2008;2(2):153–156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jethwani KS, Mishra SV, Jethwani PS, Sawant NS. Surveying Indian gay men for coping skills and HIV testing patterns using the internet. J Postgrad Med. 2014;60(2):130–134. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.132315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joshi U, Ceena DE, Ongole R, et al. AIDS related Kaposi’s sarcoma presenting with palatal and eyelid nodule. J Assoc Phys India. 2012;60:50–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karass M, Grossniklaus E, Seoud T, Jain S, Goldstein DA. Kaposi sarcoma inflammatory cytokine syndrome (KICS): a rare but potentially treatable condition. Oncologist. 2017;22(5):623–625. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karim QA. Current status of the HIV epidemic & challenges in prevention. Indian J Med Res. 2017;146(6):673–676. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1912_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kharkar V, Gutte RM, Khopkar U, Mahajan S, Chikhalkar S. Kaposi’s sarcoma: a presenting manifestation of HIV infection in an Indian. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75(4):391–393. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.53137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kodra A, Walczyszyn M, Grossman C, Zapata D, Rambhatla T, Mina B. Case report pulmonary Kaposi sarcoma in a non-HIV patient. F1000Research. 2015;4:1013. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.7137.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumarasamy N, Solomon S, Yesudian PK, Sugumar P. First report of Kaposi’s sarcoma in an AIDS patient from Madras. India. Indian J Dermatol. 1996;41(1):23–25. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu Z, Fang Q, Zuo J, Minhas V, Wood C, Zhang T. The world-wide incidence of Kaposi’s sarcoma in the HIV/AIDS era. HIV Med. 2018;19(5):355–364. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manion M, Uldrick T, Polizzotto MN, et al. Emergence of Kaposi’s sarcoma herpesvirus-associated complications following corticosteroid use in TB-IRIS. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018;5(10):ofy217. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofy217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Margalith M, Chatlynne LG, Fuchs E, et al. Human herpesvirus 8 infection among various population groups in southern Israel. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;34(5):500–505. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200312150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McArdle AJ, Turkova A, Cunnington AJ. When do co-infections matter? Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2018;31(3):209–215. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mehta S, Garg A, Gupta LK, Mittal A, Khare AK, Kuldeep CM. Kaposi’s sarcoma as a presenting manifestation of HIV. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2011;32(2):108–110. doi: 10.4103/0253-7184.85415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meintjes G, Lawn SD, Scano F, et al. Tuberculosis-associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome: case definitions for use in resource-limited settings. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8(8):516–523. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(08)70184-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Modak D, Ganguly RR, Haldar SN, Samanta PS, Pramanik N, Guha SK. Castlemans disease in HIV infected patient from eastern India. J Assoc Phys India. 2008;56:547–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mukherjee S. Emerging infectious diseases: epidemiological perspective. Indian J Dermatol. 2017;62(5):459–467. doi: 10.4103/ijd.IJD_379_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Munawwar A, Sharma SK, Gupta S, Singh S. Seroprevalence and determinants of Kaposi sarcoma-associated human herpesvirus 8 in Indian HIV-infected males. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2014;30(12):1192–1196. doi: 10.1089/aid.2014.0184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paranjape RS, Challacombe SJ. HIV/AIDS in India: an overview of the Indian epidemic. Oral Dis. 2016;22(S1):10–14. doi: 10.1111/odi.12457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pelser C, Dazzi C, Graubard BI, Lauria C, Vitale F, Goedert JJ. Risk of classic Kaposi sarcoma with residential exposure to volcanic and related soils in Sicily. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19(8):597–601. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perez-Alvarez S, Benavente Y, de Sanjose S, et al. Geographic variation in the prevalence of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus and risk factors for transmission. J Infect Dis. 2009;199(10):1449–1456. doi: 10.1086/598523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Potsangbam G, Surchandra Sharma S, Singh TJ, et al. Intra-lesional injection of vinblastine in a pedunculated oral Kaposi’s sarcoma in a patient of AIDS. JIACM. 2007;8(1):99–100. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qin J, Lu C. Infection of KSHV and interaction with HIV: the bad romance. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1018:237–251. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-5765-6_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sarmati L, Andreoni M, Suligoi B, et al. Infection with human herpesvirus-8 and its correlation with hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus markers among rural populations in Cambodia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;68(4):501–502. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2003.68.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sarov B, Davidovici B, Boshoff C, et al. Seroepidemiology and molecular epidemiology of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus among jewish population groups in Israel. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(3):194–202. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.3.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sehgal VN, Verma P, Sharma S. HIV/AIDS Kaposi sarcoma: the Indian perspective. Skinmed. 2013;11(6):375–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sharma RK, Bhardwaj S. Kaposi sarcoma presenting as an index sign of HIV infection in an Indian. JK Sci. 2012;14(3):158–160. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sharp PM, Hahn BH. Origins of HIV and the AIDS pandemic. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Med. 2011;1(1):a006841-a41. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shenoy VV, Joshi SR, Duberkar D, Kadam KN, Shedge RT, Lanjewar DN. Kaposi’s sarcoma with thrombocytopenia in a heterosexual Asian Indian male. J Assoc Phys India. 2005;53:486–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shroff HJ, Dashatwar DR, Deshpande RP, Waigmann HR. AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma in an Indian female. J Assoc Phys India. 1993;41(4):241–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Simonart T. Iron: a target for the management of Kaposi’s sarcoma? BMC Cancer. 2004;4(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Simonart T. Role of environmental factors in the pathogenesis of classic and African-endemic Kaposi sarcoma. Cancer Lett. 2006;244(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sinha A, Goswami D, Haldar D, Mallik S, Bisoi S, Karmakar P. Sexual behavior of transgenders and their vulnerability to HIV/AIDS in an Urban Area of Eastern India. Indian J Public Health. 2017;61(2):141–143. doi: 10.4103/ijph.IJPH_248_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Solomon S, Solomon SS, Ganesh AK. AIDS in India. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82(971):545–547. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2006.044966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Su CC, Lai CL, Tsao SM, et al. High prevalence of human herpesvirus type 8 infection in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in Taiwan. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21(3):266.e5–266.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sunil M, Reid E, Lechowicz MJ. Update on HHV-8-associated malignancies. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2010;12(2):147–154. doi: 10.1007/s11908-010-0092-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thakker S, Verma SC. Co-infections and pathogenesis of KSHV-associated malignancies. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:151. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.The LancetH. Homosexuality law reform is just a first step for India. The lancet. HIV. 2018;5(10):e537. doi: 10.1016/s2352-3018(18)30260-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.V Singh R, Singh S, Pandey S. Numerous giant mollusca contagiosa and Kaposi’s sarcomas with HIV disease. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1996;62(3):173–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vaishnani JB, Bosamiya SS, Momin AM. Kaposi’s sarcoma: a presenting sign of HIV. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76(2):215. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.60542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Verma SC, Robertson ES. Molecular biology and pathogenesis of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;222(2):155–163. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00261-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wakeham K, Webb EL, Sebina I, et al. Parasite infection is associated with Kaposi’s sarcoma associated herpesvirus (KSHV) in Ugandan women. Infect Agents Cancer. 2011;6(1):15. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-6-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang X, Zou Z, Deng Z, et al. Male hormones activate EphA2 to facilitate Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection: implications for gender disparity in Kaposi’s sarcoma. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13(9):e1006580. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Warpe BM. Kaposi sarcoma as initial presentation of HIV infection. N Am J Med Sci. 2014;6(12):650–652. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.147984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang T, Wang L. Epidemiology of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus in Asia: challenges and opportunities. J Med Virol. 2017;89(4):563–570. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang T, Shao X, Chen Y, et al. Human herpesvirus 8 seroprevalence, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18(1):150–152. doi: 10.3201/eid1801.102070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Overallcharacterization of Indian KSHV associated malignancy (TIFF 1038 kb)