Abstract

Medication‐related problems (MRPs) are an important healthcare problem. This study aimed at reviewing the published literature in Ethiopia to estimate the prevalence of MRPs and to summarize associated factors. A comprehensive systematic search was conducted in PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, Scopus, Google Scholar, and Google databases from inception to April 2020. Articles that addressed MRPs were eligible for inclusion. Article screening, data extraction, and study quality analysis were performed independently by two reviewers. Studies targeting specific disease condition were considered as specific, while the remaining were nonspecific. The prevalence of MRPs was then computed in medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), while associated factors were summarized in a table. Of the thirty‐two studies included in this review, the majority of them (n = 24) targeted MRPs, while the remaining studies (n = 8) investigated adverse drug reactions (ADRs). Studies varied in the study design, study population, and definition of MRPs and ADRs used. The overall median prevalence was 70.8% (IQR = 61.0‐80.2) with a range of 16.0% to 88.7%. The median prevalence of MRPs in specific and nonspecific patients was 71.2% (IQR = 60.7‐71.2) and 69.3% (IQR = 60.7‐82.0), respectively. In addition, a median of 36.6% (IQR = 10.0‐85.7) of patients experienced ADRs. Indication‐related and effectiveness‐related MRPs were commonly reported in both specific and nonspecific patients, while noncompliance MRPs were more prevalent among specific patients than nonspecific patients. Increasing age, presence of co‐morbidity, and an increasing number of drugs were the commonly identified contributing factors of MRPs. The review showed that more than two‐thirds of the study participants developed MRPs. Hence, an integrated approach should be designed to improve the optimal use of pharmacotherapy to reduce the burden of MRPs. Further, future research should be undertaken to prepare cost‐effective and efficient prevention mechanisms to reduce or halt the development of MRPs.

Keywords: adverse drug reaction, Ethiopia., factors, Medication‐related problem

Abbreviations

- ADRs

adverse drug reactions

- MRPs

Medication‐related problems

- NHA

National Health Accounts

- PRISMA‐P

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis Protocols

1. INTRODUCTION

Medicines contribute to the improvement of quality of life and life expectancy by relieving symptoms, delaying disease progression, and curing diseases. However, no drug is entirely harmless and can be associated with emergency department visits, 1 hospitalizations, 2 in‐patient, 3 and outpatient 4 care complications. MRPs are unwanted effects that actually or potentially interfere with health outcomes. 5 They are significant causes of patient morbidity, mortality, economic loss, and contribute to overall pressure on the healthcare system. 6 , 7 , 8 MRPs include medication errors, adverse drug events, and adverse drug reactions.

For the last three decades, medication safety has been the primary research focus in Africa. The recent review of African studies showed that the median (interquartile range) percentage of patients experiencing adverse drug events during hospital admission and as a cause of hospital admission was 8.4% (4.5‐20.1%) and 2.8% (0.7‐6.4%), respectively. Interestingly, a median of 43.5% of these events was deemed to be preventable. 9 Patients living in low‐income countries experience twice as many disability‐adjusted life years lost due to medication‐related harm than those in high‐income countries. 10

Ethiopia's healthcare system has also faced these challenges in similar way with other low‐income countries. In the past two decades, the Government of Ethiopia has invested heavily in the healthcare system and prepared the Health Sector Transformation Plan (HSTP) to improve the health status of Ethiopians. The fifth round of the National Health Accounts (NHA) showed that the overall nominal health expenditure in 2010/11 raised by 138% compared to the 2007/08 total budget. As a result, Ethiopia achieved 67% and 69% reduction in the under‐five mortality and maternal mortality, respectively, that raised the average life expectancy from 45 years in 1990 to 64 years in 2014. 11 Despite these achievements, MRPs remain a major challenge in the healthcare system. A recent systematic review of Ethiopian studies indicated that 36.8% of patients practiced self‐medication. 12 This further increases the occurrence of the problem. There are several MRP studies conducted in Ethiopia; however, the scope of these problems has not been summarized, and their magnitude remains unclear.

1.1. Aim of the review

The aim of this systematic review was to summarize the prevalence of MRPs and associated factors in the Ethiopian healthcare system.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

The systematic review protocol was developed based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis Protocols (PRISMA‐P) 2015 guidance 13 (Online Appendix one).

A systematic search of the literature was conducted to identify relevant published studies from journal inception to 01 April 2020. Studies that reported the prevalence and risk factors of MRPs were reviewed based on the following eligibility criteria.

2.1. Inclusion criteria

Studies on MRPs targeting adult (age ≥ 15 years) in‐patient and outpatient departments were eligible for inclusion in this systematic review. Additionally, studies focused on ADRs and adverse drug events (ADEs) were also included. Further, studies examined events associated with the specific drug(s), class of drug(s), organ(s), or system(s) were included.

2.2. Exclusion criteria

The studies were excluded if they:

Were conference papers, abstracts, editorial reports, or letters to the editors with limited information;

Were case studies, case series, and qualitative studies; or

Focused only in the pediatric population; or

Studies published in other languages than English.

2.3. Information sources

The following databases were used as sources of information:

Electronic databases: Medline via PubMed, EMBASE via Ovid, Scopus, and Cumulative Index to the Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL);

Grey literature was sourced through Google and Google Scholar; and

The reference list of included articles was manually screened for relevant articles.

2.4. Search strategy

The following search terms were used: “medication‐related problem,” “drug therapy problem,” “Drug‐related side effects and adverse reactions,” “medication error,” “medication related problem,” “adverse drug reaction,” “adverse drug event,” “drug toxicit*,” “drug induced problem,” “factor,” “predictor,” and “Ethiopia.” The search results were combined using Boolean operators (“OR” and “AND”). All search results from each database were saved in the individual electronic databases and exported into Endnote referencing software. Studies that were identified using manual searches were exported directly into the Endnote library.

2.5. Study selection and data extraction

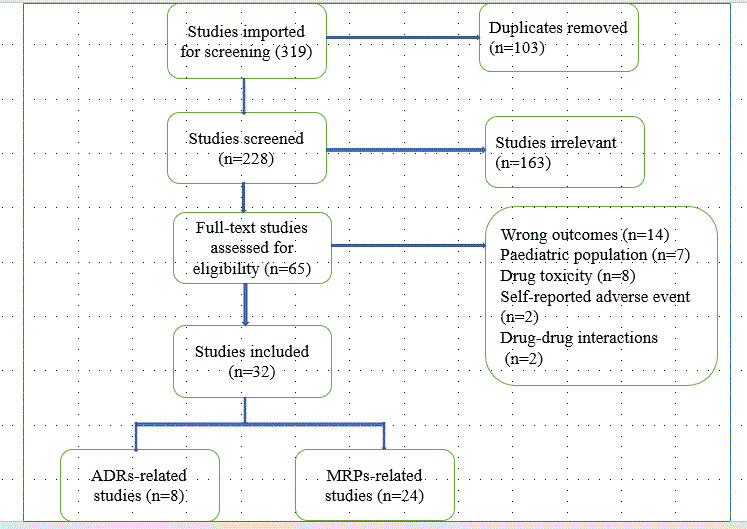

Once all search results were transferred into the Endnote library, duplicates were removed. The remaining studies were exported into Covidence software for the title and abstract screening. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were set in the Covidence software to aid the initial screening. This screening was performed by the two researchers (GTT and AD). Three categories (yes, no, maybe) were used during the selection process. The full text of studies considered “yes” or “maybe” during the screening was then assessed based on the eligibility criteria by two researchers (GTT and BK). The disagreement was resolved by consensus. The quality of included studies was assessed using the Newcastle‐Ottawa quality assessment scale by two researchers (GTT and BK). 14 Quality assessment was undertaken independently by two reviewers (GTT and BK), with any disagreements resolved by discussion (online Appendix two). The overall review process is shown in Figure 1. A data extraction tool was developed by adapting and customizing the “Data collection form for intervention review—RCTs and non‐RCTs” from the Cochrane Collaboration. 14 Data extraction was performed by two independent reviewers (GTT and BK). The following data were extracted from the included articles: study characteristics (author name and year of publication, hospital setting, study design, sample size, and the target population), attributes of MRPs, ADRs or ADEs (components of MRPs, definition, causality, severity, and preventability), and major findings (frequency, risk factors, and clinical outcomes).

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing article screening process.

2.6. Data analysis

The prevalence of MRPs and ADRs was summarized with medians and interquartile ranges, and their attributes were described accordingly. Studies were divided as those targeted specific patients (eg, diabetes, cardiovascular, hypertensive) and nonspecific or general patients (eg, medical ward admitted patients). Components of MRPs were summarized using Cipolle et al 5 classification system, as it is frequently used by Ethiopian researchers. Further, associated risk factors of MRPs (for both specific and nonspecific patients) and ADRs were reported as socio‐demographic, disease, medication, and healthcare‐related using a table.

3. RESULTS

3.1. General description of the included studies

A total of 319 articles were eligible for the article screening process. After the removal of duplicates, 228 articles remained for abstract and title screening. Based on the initial title and abstract screening, 65 articles were eligible for full‐text assessment. Finally, 32 studies were included for the final review based on the eligibility criteria mentioned above. The remaining 33 articles were excluded for various reasons (Figure 1).

A total of 32 studies encompassing 12 792 study participants from most parts of Ethiopia were included. The number of study participants varied from a smaller prospective study of 97 patients 15 to a larger retrospective study involving 3921 study participants. 16 The oldest study was published in 2012, 17 while the most recent was in 2020. 18 Twenty‐four studies were conducted on MRPs, of which 15 studies were conducted in a specific patient population, and the remaining were conducted among general/nonspecific patient populations. 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 In addition, eight studies targeted ADRs.

More than two‐thirds of the included studies used prospective study design, while the remaining seven studies 20 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 employed retrospective design. However, Esayas et al 16 employed both retrospective and prospective study designs. Furthermore, more than half of the included studies (n = 18) were conducted in ambulatory patients, of which one study 34 focused on ADR‐related hospital admissions. Two studies 35 , 36 focused on both in and outpatients (Table 1, 2, 3).

Table 1.

General characteristics of the included studies focused on MRPs in nonspecific patients

| Author | Study setting | Study design | Study population | Sample size | Prevalence of MRPs (%) | Categorization of MRPs | Indication‐related problem (%) | Efficacy‐related problem (%) | Safety‐related problem (%) | Noncompliance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mohammed et al. 22 | TASH | Prospective cross‐sectional study | Medical inpatients | 225 | 52.0 | Cipolle et al. | 16.1 | 6.4 | 24.3 | 23 |

| Yaschilal et al. 23 | DRH | Prospective observational | Medical inpatients | 147 | 75.5 | Cipolle et al. | 66.09 | 15.1 | 13.2 | 9.43 |

| Gashaw et al. 37 | GUCSH | Prospective cross‐sectional | Medical inpatients | 256 | 66.0 | PCNE | 28.5 | 39.1 | 23.1 | 4.7 |

| Berhane et al. 24 , a | JUSH | Prospective cross‐sectional | Medical and surgical inpatients | 200 | 82.0 | Cipolle et al. | 46.6 | 21.0 | 40.1 | 24.2 |

| Kebede et al. 25 | AKEH | Prospective observational | Medical inpatients | 260 | 62.0 | ® | 54.0 | 25.6 | 12.0 | NR |

| Alemayehu et al. 26 | JUSH | Prospective observational | Medical inpatients | 300 | 16.0 | Cipolle et al. | 47.0 | 14.8 | 18.7 | 10.7 |

| Gosaye et al. 21 | JUSH | Prospective observational | Surgery inpatients | 300 | 69.3 | Cipolle et al. | 21.9 | 37.5 | 23.0 | 5.5 |

| Bereket et al. 20 | JUSH | Cross sectional | Medical inpatients | 257 | 73.5 | Cipolle et al. | 47.5 | 27.2 | 15.5 | NR |

| Tadele et al. 19 | JUSH | Prospective observational | Medical inpatients | 152 | 75.7 | Cipolle et al. | 58.5 | 38.1 | 23.7 | 17 |

AKEH Alem Ketema Enat Hospital, DRH Dessie Referral Hospital,

Elderly inpatients, GUCSH, Gondar University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, JUSH, Jimma University Specialized Hospital, ® medication error, NR, not reported, PCNE, Pharmaceutical Care Network of Europe, TASH, Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital.

Table 2.

General characteristics of the included studies focused on MRPs in specific patients

| Author | Study setting | Study design | Study population | Sample size | Prevalence of MRPs | Categorization of MRPs | Indication‐related problem (%) | Efficacy‐related problem (%) | Safety‐related problem (%) | Noncompliance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ousman et al. 35 | GUCSH | Cross sectional | CVD in & out patients | 227 | 63.4 | PCNE | 24.9 | 19.7 | 3.0 | 17.4 |

| Haymen et al. 27 | HFSUH | Retrospective cross sectional |

Ambulatory DM II Patients |

148 | 64.2 | Cipolle et al. | 33.1 | 55.9 | 11.0 | NR |

| Yohanes et al. 28 | HFSUH | Retrospective cross sectional | Ambulatory DM II & HTN patients | 203 | 49.2 | PCNE | 31.8 | NR | 19.0 | NR |

| Abadir et al. 39 | DCRH | Cross sectional | Ambulatory HTN patients | 271 | 71.2 | Cipolle et al. | 63.7 | 2.7 | 0.8 | 32.8 |

| Gebre et al. 43 | TASH | Cross sectional | Ambulatory DM patients | 418 | 42.3 | Cipolle et al. | 34.8 | 54.1 | 11.1 | 24.0 |

| Aster et al. 44 | JUSH | Prospective observational | CKD inpatients | 103 | 78.6 | Cipolle et al. | 35.5 | 28.0 | 16.5 | 20.0 |

| Mohammednur et al. 41 | AHMC | Cross sectional | Ambulatory HTN patients | 192 | 80.7 | Cipolle et al. | 2.2 | 0.9 | 18.6 | 19.5 |

| Tamene et al. 36 | HFSUH | Cross sectional | CVD in & outpatient | 216 | 60.7 | Cipolle et al. | 70.2 | 6.9 | NR | 12.2 |

| Kaleab 45 | GSGH | Prospective cross sectional | Ambulatory CVD patients | 130 | 72.0 | Cipolle et al. | 39.2 | 12.9 | 19.7 | 28.2 |

| Hailu et al. 29 | WSUTRH | Cross sectional | Ambulatory DM II patients | 243 | 83.1 | Cipolle et al. | 63.0 | 30.1 | 10.7 | 51.9 |

| Beshir et al. 18 | TASH | Prospective cross sectional | Ambulatory epileptic patients | 291 | 70.4 | Cipolle et al. | 6.0 | 34.6 | 46.6 | 44.3 |

| Yirga et al. 42 | JUSH | Prospective observational | Ambulatory HF patients | 340 | 83.5 | Cipolle et al. | 31.1 | 55.4 | 4.6 | 9.0 |

| Gobezie et al. 15 | Two hospitalsa | Cross sectional | CVD inpatients | 97 | 88.7 | Cipolle et al. | 58.4 | 11.5 | 22.2 | 46.4 |

| Asgedom et al. 32 | ACSH | Cross sectional | Ambulatory HTN patients | 241 | 55.6 | Cipolle et al. | 28.3 | 29.1 | 2.5 | 40.1 |

| Mohammed et al. 40 | JUSH | Prospective cross sectional | Ambulatory DM II and HTN patients | 300 | 82.0 | Cipolle et al. | 39.7 | 43.2 | 4.4 | 12.2 |

ACSH, Ayder Comprehensive Specialized Hospital; AHMC, Adama Hospital Medical College; CKD, chronic kidney disease, CVD, cardiovascular disease, DCRH, Dil Chora Referral Hospital, DM II, diabetes mellitus type II, FHRH, Felege hiwot referral hospital, GSGH, Gebretsadik Shawo General Hospital; GUCSH, Gondar University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital; HF, heart failure, HFSUH, Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital; HTN, hypertension; JUSH, Jimma University Specialized Hospital.

aJUSH & FHRH; NR, not reported, PCNE, Pharmaceutical Care Network of Europe; TASH, Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital; WSUTRH, Wolaita Sodo University Teaching Referral Hospital.

Table 3.

General characteristics of the included studies focused on ADRs among patients

| Author | Study setting | Study design | Study population |

Sample Size |

ADR Prevalence (%) | ADR definition | Causality of ADR (%) | Severity of ADR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Senbeta et al. 17 | TASH | Prospective observational | HIV Outpatients | 228 | 51.1 | NR | NR | NR |

| Mulugeta et al. 34 | JUSH | Prospective cross sectional | Medical inpatients | 1,001 | 10.3 | WHO | Naranjo: definite (26.1%), probable (73.9%) | NR |

| Woldesellassie et al. 47 | FHRH | Prospective cohort | HIV Outpatients | 211 | 85.7 | WHO | Naranjo: definite (1.7%), probable (31.8%), possible (66.5%) | ¥52.7 (Grade 1), 25.2 (Grade 3), 22.1 (Grade 4) |

| Sewunet et al. 46 | GUCSH | Cross sectional | Cancer patients | 384 | 52.9 | WHO | Naranjo: probable (68.8%), possible (31.4%) | £70.1 (Grade 3‐5), 29.9 (Grade 1‐4) |

| Esayas et al. 16 | Multi‐hospitals a | Prospective cohort | HIV Outpatients | 3,921 | 22.1 | WHO | NR | 43.3 (life‐threatening) |

| Etsegenet et al. 30 | FHRH | Retrospective | HIV Outpatients | 602 | 10.0 (4.3/100PY) | WHO | NR | NR |

| Mehari et al. 31 | Multi‐hospitals a | Retrospective cohort | Drug‐resistant Tuberculosis patients | 570 | 51.2 (5.8/100PM) | ® | NR | NR |

| Fitsum et al. 33 | HFSUH | Retrospective | HIV Outpatients | 358 | 17.0 | WHO | NR | 80.3 (Grade III) |

® Adverse Drug Event, ADR adverse drug reaction, FHRH Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital,

Four hospitals (University of Gondar comprehensive specialized hospital, Debre Markos Referral Hospital, Borumeda primary hospital, and Woldia primary hospital), GUCSH Gondar University Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, HFSUH Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital, HIV human immune virus, NR not reported.

Seven hospitals located in Addis Ababa, Hawassa, Jimma, Haramaya, Mekelle and Gondar towns, TASH, Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital, WHO, World Health Organization, £ National Cancer Institute Common Terminology grade 1–5 toxicity, ¥ DAIDS adverse events severity grading, 100 PM 100 person month, 100PY, 100 persons year

3.2. Studies conducted on MRPs among nonspecific/general patient population

Concerning studies (n = 9) conducted in nonspecific patients, a total of 2,097 (147‐300) patients were involved. All studies used Cipolle et al 5 MRPs categorization system, except Alemayehu et al 37 that used the Pharmaceutical Care Network of Europe. 38 All of them were prospective cross‐sectional studies. Except Berhane et al, 24 which targeted elderly patients (>=60 years), other studies investigated the adult population. Seven out of nine studies 20 , 22 , 23 , 25 , 26 , 37 targeted patients admitted to medical wards. In addition, Berhane et al 24 and Gosaye et al 21 studied surgical and medical inpatients, and surgical inpatients, respectively. Further, Gosaye et al 21 and Tadele et al 19 focused on antibiotic‐related MRPs (Table 1).

The median prevalence of MRPs in studies involving patients from general wards was 69.3% (IQR 60.7‐82.0). MRPs’ prevalence ranged from 16.0% 26 to 82.0%. 24 Frequently identified MRP types were unnecessary drug therapy (23.4%), need additional drug therapy (23.2%), and dose too high (15.1%). In addition, a median of 29.0% MRPs was dose‐related. All of the studies reported the rate of non‐compliance except two studies 22 , 25 . However, none of them used a standardized tool to measure noncompliance (Table 4). Further, only one study 23 reported clinical outcomes of MRPs, and Bereket et al 20 was also the only study that did not report causative agents (drugs) of MRPs.

Table 4.

Prevalence of each component of MRPs in the included studies

| Components of MRPs | Median (range) percentage b | Median (range) percentage a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indication‐related problems | Unnecessary drug therapy | 23.4 (4.3–40.0) | 5.4 (0.9–19.7) |

| Need additional drug therapy | 23.2 (4.9–35.9) | 28.5 (5.1–62.4) | |

| Total | 47.0 (16.1–66.1) | 33.9 (2.2–70.2) | |

| Ineffective drug‐related problems | Ineffective drug therapy | 4.6 (1.9–18.4) | 10.4 (1.9–27.8) |

| Dose too low | 13.9 (3.9–32.9) | 13.2 (0.8–36.2) | |

| Total | 25.6(6.4–39.1) | 23.9 (0.9–55.9) | |

| Safety‐related problems | ADEs/ADRs | 9.4 (2.3–24.2) | 9.4 (1.7–41.5) |

| Dose too high | 15.1 (1.3–20.7) | 2.7 (0.8–14.5) | |

| Total | 23.0(12.0–40.1) | 11.5 (2.5–46.6) | |

| Compliance‐related problems | Noncompliance | 10.7 (4.7–24.2) | 22 (9.0–51.9) |

For a specific group of patients

For nonspecific patients, ADE, adverse drug event; ADRs, adverse drug reactions; MRPs, medication‐related problem.

3.3. Studies conducted on MRPs among the specific patient population

Among 15 studies conducted in specific patient cohorts, a total of 3,420 (97‐418) patients were involved. None of these studies focused on elderly patients. Most studies categorized MRPs using Cipolle et al classification system 5 except two studies, 28 , 35 . In addition, two‐thirds of the studies used prospective designs except for Haymen et al, 27 Yohanes et al, 28 Abadir et al, 39 and Hailu et al 29 studies. More than half (n = 10) of the included studies investigated one or more cardiovascular disease conditions, 15 , 28 , 32 , 35 , 36 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 while Gebre et al, 43 Aster et al 44 and Beshir et al 18 studied ambulatory diabetic patients, hospitalized chronic kidney disease patients, and ambulatory epileptic patients, respectively. Moreover, Haymen et al 27 and Hailu et al 29 targeted ambulatory type II diabetes mellitus patients. Only two studies, Mohammednur et al 41 and Beshir et al, 18 reported clinical outcomes of MRPs (Table 2). Further, seven studies 27 , 28 , 29 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 reported the specific causative agents (drugs) responsible for MRPs.

The median prevalence of MRPs in specific patients was 71.2% (IQR 60.7‐71.2). The prevalence ranged from 42.3% 43 to 88.7%. 15 Need additional drug therapy (28.5%), noncompliance (22%), and dose too low (13.2%) were the frequently identified MRPs. Among studies targeted ADRs, three studies 27 , 28 , 35 did not report the rate of noncompliance. Among the studies that report noncompliance, all except Tegegne et al. 15 did not use a standardized tool (Table 4).

3.4. Studies conducted on ADRS

Among eight studies conducted on ADRs, 7275 (211‐3,921) patients were included. Of these, three studies used retrospective study design, 30 , 31 , 33 while Esayas et al 16 used both prospective and retrospective study designs. The remaining studies used a prospective study design. Except for Sewunet et al that studied ADRs on Cancer patients, 46 other studies focused on ambulatory patients; of these studies, Mehari et al 31 investigated ADRs on drug‐resistant tuberculosis patients and others focused on ambulatory HIV/AIDS patients. 16 , 17 , 30 , 46 , 47 Further, Mulugeta et al 34 investigated ADR‐related hospital admission.

Most studies 16 , 30 , 33 , 34 , 46 , 47 used WHO ADRs definition, while Abdissa et al 17 did not report the definitions they used. In addition, Mehari et al 31 investigated ADEs despite the definitions they used was not reported. All except Etsegenet et al, 30 reported the clinical outcome of ADRs. Further, two studies 34 , 46 reported the causative agents of ADRs.

The overall median prevalence of ADRs was 36.6% (10.0‐85.7), with a range of 10.0% 30 to 85.7%. 47 Only three studies 34 , 46 , 47 used Naranjo et al 48 causality assessment criteria, while others did not report the method of ADRs causality assessment criteria used. All studies 16 , 34 , 46 , 47 did not report the severity and preventability of ADRs except Woldesellassie et al 47 and Mulugeta et al 34 studies. In Woldesellassie et al 47 study, 16.3% of the reactions were preventable, while in Mulugeta et al 34 study, it was reported that 89.1% ADRs (definite 16.0% and probable 73.1%) were preventable. Furthermore, except Abdissa et al study, which reported an 83.2% type A reactions, 17 others did not report ADRs’ classification (Table 3).

3.5. Identified risk factors of ADRs and MRPs among the included studies

Age and gender in both specific 29 , 40 , 42 , 43 and nonspecific patients 20 were the most frequently identified risk factors of MRPs, while age 31 , 46 was the most frequent risk factors of ADRs.

Considering disease‐related variables, the number of diagnoses 24 , 35 and presence of comorbidity 29 , 32 , 39 , 40 , 44 in specific patients were the commonly identified risk factors of MRPs. In addition, the number of drugs in both nonspecific 20 , 21 , 22 , 24 , 25 , 35 and specific patients 18 , 29 , 36 , 39 , 41 , 42 , 44 were the frequently reported risk factor of MRPs, while taking zidovudine regimen 16 , 33 , 47 was the frequent risk factor of ADRs.

Further, concerning healthcare‐related factors, the length of hospital stay 19 , 21 , 25 , 37 in nonspecific patients was the frequent risk factors of MRPs, while there were no statistically significant healthcare‐associated risk factors of ADRs (Table 5).

Table 5.

Summary of the risk factors associated with MRPs and ADRs in Ethiopia

| Category of associated risk factors | Risk factors of MRPs (nonspecific patients) |

Risk factors of MRPs (specific patients) |

Risk factors of ADRs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient‐related | Age 20 , Gender 20 | Age 29 , 40 , 42 , Gender 43 , Place of residence 43 , Marital status 41 , 43 , 44 , Nonadherence 43 | Age 31 , 46 , Unemployment 47 , BMI 34 , Marital status 16 , Occupation 30 , Educational status 30 |

| Disease‐related | Number of diagnoses 24 , 35 , Presence of comorbidity 25 , Overall clinical outcome 21 , CDC wound class 21 , Indication for antibiotic use 21 | Uncontrolled BP 39 , Presence of comorbidity 29 , 32 , 39 , 40 , 44 , Number of diagnoses 41 , 42 , 43 , Presence of DM II 43 , Stage of CKD 44 , Complication 41 , Heart failure 15 | Previous AKI 34 , Liver disease 34 , Number of diagnoses 34 , History of ADRs 34 , HIV clinical stage 30 , Comorbidity 31 , Anaemia 31 |

| Medication‐related | Number of drug 20 , 21 , 22 , 24 , 25 , 35 , Significant DDI 20 , Drug availability 25 , Antibiotic exposure 21 | Number of drugs 18 , 29 , 36 , 39 , 41 , 42 , 44 , Substance use 32 | Number of drugs 34 , 46 , Taking ZDV regimen 16 , 33 , 47 , Taking anti‐TB drugs 16 , OI prophylaxis 30 |

| Healthcare‐related | Length of hospital stay 19 , 21 , 25 , 37 , Type of surgery 21 | History of hospitalization 29 , Negative belief on medication use 42 , Poor involvement of patients on therapeutic decision 42 |

AKI acute kidney disease, BMI body mass index, BP blood pressure, CDC communicable disease control, CKD chronic kidney disease, DDI drug‐drug interaction, DM diabetes mellitus, OI opportunistic infection, TB tuberculosis, ZDV zidovudine

4. DISCUSSION

This systematic review provides an up‐to‐date and comprehensive assessment of the prevalence and risk factors MRPs and ADRs in Ethiopia. Thirty‐two studies, published from journal inception to April 2020, were identified to look at MRPs in the Ethiopian healthcare system. The findings showed that MRPs and ADRs were critical problems of patient care that posed a significant burden to healthcare professionals and the healthcare system in Ethiopia. Hence, appropriate prevention strategies should be designed to reduce their burden.

The overall median percentage of MRPs among included studies was 70.8% (IQR 61.0‐80.2) with the range of 16.0% to 88.7%. In addition, a median prevalence of 71.2% and 69.3% MRPs were identified in the specific and nonspecific patient population, respectively. Higher percentage of MRPs was identified in specific patients than nonspecific patients. Moreover, more than one‐third of patients (a median prevalence of 36.6%) experienced ADRs. Further, despite inconsistencies among studies, several sociodemographic, and disease and medication‐related characteristics were reported to be independently associated with MRPs and ADRs.

In this review, the median prevalence of MRPs is higher than the review conducted among African studies 9 which reported a median prevalence of 8.4% and 2.8% ADEs that were responsible for inpatient complications and a reason for hospital admission, respectively. ADEs are unwanted MRPs involving side effects, ADRs, and toxicities. In addition, the finding of our review is higher than the recent systematic review performed by Ayalew et al 49 which reported a 15.0% medication‐related hospital admissions. This review did not involve MRPs during the hospital stay. Further, our finding is also higher than an international review of studies performed by Wilbur et al. 50 This review reported that 15.4% of hospital visits were drug‐related. 50 Higher prevalence in our review maybe due to the minimal effort made to institutionalize clinical pharmacy service. 51 This was seen in Bilal et al study, which reported that 47% of pharmacists rated their service as poor and their overall satisfaction was about 36%. 51 Despite this, majority of healthcare providers (85.71%) had a positive attitude toward clinical pharmacy service. 52

Despite heterogeneity among the included studies, increasing age, female gender, presence of comorbidity, and increasing number of drugs were consistently reported risk factors of MRPs in both general and specific patients. Higher prevalence of inappropriate medication use and complex prescribing practice makes older patients at a higher risk of MRPs due to age‐related physiological changes, the presence of various chronic diseases, and numbers of medications. 53 , 54 In addition, due to different body compositions, hormonal differences, and blood concentrations of certain metabolic enzymes 55 make females more susceptible to MRPs. Moreover, the existence of comorbidity is often associated with the use of more than one medication. Studies revealed that multiple medication use and drug–drug interactions predispose patients to MRPs. 56 , 57 Moreover, increasing age, number of drugs, and drug regimen containing Zidovudine were the frequently reported predictors of ADRs. This is in line with a review by Mulugeta et al. 58

Based on our findings, the following recommendations are forwarded for future studies. Future studies should use standardized definitions for MRPs and ADRs, and standardized tool for ADRs causality, classification, severity, preventability, and noncompliance assessment. Noncompliance assessment tool indicated by Cipolle et al 5 and Pharmaceutical care network of Europe 38 are not standardized; hence, other tools like the Morisky adherence scale may be used. In addition, researchers ought to focus on a specific disease condition to investigate MRPs and ADRs.

4.1. Strength and limitations

The strengths of our systematic review include complete literature search in more than one relevant database (PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, Scopus, Google, and Google scholar) and proper screening of eligible studies by two independent reviewers. In addition, our review has the following limitations; due to the heterogeneity of studies, it was not possible to undertake a meta‐analysis. As lists of medications responsible for MRPs and ADRs were too many, and the way studies reported these medications were inconsistent, it was challenging to summarize causative agents of MRPs/ADRs. Finally, we acknowledge that we may not have been able to retrieve unpublished data and grey literature.

5. CONCLUSION

Although the prevalence of MRPs and ADRs varied among studies due to the definition, study population and method used more than two‐third and one‐third of patients experienced MRPs and ADRs, respectively. Higher prevalence of MRPs was found in studies targeting specific patients than nonspecific patients. In addition, the review showed that almost half of the study participants had an indication‐related MRPs, while effectiveness and safety‐related MRPs occurred among one in four patients. Further, different socioeconomic, disease‐related, medication‐related, and healthcare‐related variables contribute to the development of MRPs and ADRs. This review found that MRPs and ADRs constitute significant problems in the Ethiopian healthcare system. Hence, healthcare professionals' coordinated effort is necessary and efficient prevention strategies that target the identified risk factors should be designed to lessen the burden of the problem. Furthermore, an efficient healthcare system that involves pharmacists in patient care should be strengthened. Last but not the least, a qualified and sufficient number of pharmacists should be allocated to the different hospital wards and follow‐up clinics.

ETHICS APPROVAL

Not applicable.

CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Not applicable.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

The authors consented to publish this review.

CODE AVAILABILITY

Not applicable.

DISCLOSURE

The authors declared that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

GTT and BK were participated in the review process starting from conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, and writing. In addition, AD was highly involved in methodology, formal analysis, and writing–review & editing.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

Appendix two

Kefale B, Degu A, Tegegne GT. Medication‐related problems and adverse drug reactions in Ethiopia: A systematic review. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2020;8:e00641 10.1002/prp2.641

Funding information

There is no source of funding to undertake this systematic review.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The extracted data are available if required.

REFERENCES

- 1. Zed PJ, Abu‐Laban RB, Balen RM, et al. Incidence, severity and preventability of medication‐related visits to the emergency department: A prospective study. CMAJ. 2008;178(12):1563‐1569. 10.1503/cmaj.071594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Leendertse AJ, Egberts AC, Stoker LJ, Van Den Bemt PM. Frequency of and risk factors for preventable medication‐related hospital admissions in the Netherlands. JAMA Intern Med. 2008;168(17):1890‐1896. 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hoonhout LH, de Bruijne MC, Wagner C, Asscheman H, van der Wal G, Van Tulder MW. Nature, occurrence and consequences of medication‐related adverse events during hospitalization: A retrospective chart review in the Netherlands. Drug Saf. 2010;33(10):853‐864. 10.2165/11536800-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gandhi TK, Burstin HR, Cook EF, et al. Drug complications in outpatients. JGIM. 2000;15(3):149‐154. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.04199.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Strand LM, Morley PC, Cipolle RJ, Ramsey R, Lamsam GD. Drug‐related problems: Their structure and function. DICP. 1990;24(11):1093‐1097. 10.1177/106002809002401114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wysowski DK. Surveillance of prescription drug‐related mortality using death certificate data. Drug Saf. 2007;30(6):533‐540. 10.2165/00002018-200730060-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Leendertse AJ, Van Den Bemt PM, Poolman JB, Stoker LJ, Egberts AC, Postma MJ. Preventable hospital admissions related to medication (HARM): Cost analysis of the HARM study. Value Heal. 2011;14(1):34‐40. 10.1016/j.jval.2010.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gyllensten H, Hakkarainen KM, Jönsson AK, et al. Modelling drug‐related morbidity in Sweden using an expert panel of pharmacists. IJCP. 2012;34(4):538‐546. 10.1007/s11096-012-9641-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mekonnen AB, Alhawassi TM, McLachlan AJ, Brien JE. Adverse drug events and medication errors in African hospitals: A systematic review. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2018;5(1):1‐24. 10.1007/s40801-017-0125-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Medication Without Harm ‐ Global Patient Safety Challenge on Medication Safety . Geneva: World Health Organization, 2017. Licence: CC BY‐NC‐SA 3.0 IGO.

- 11. WHO . Ethiopia Statistics. https://www.who.int/countries/eth/en/. Accessed on April 20, 2020.

- 12. Ayalew MB. Self‐medication practice in Ethiopia: A systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:401‐413. 10.2147/PPA.S131496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta‐analysis protocols (PRISMA‐P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ Br Med J. 2015;349:g7647 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos PT. The Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta‐analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed on April 04, 2020.

- 15. Tegegne GT, Yimamm B, Yesuf EA. Drug therapy problems & contributing factors among patients with cardiovascular diseases in Felege Hiwot Referral and Jimma University Specialized Hospitals, Ethiopia. IGJP Sci. 2015;6(1):26‐39. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gudina EK, Teklu AM, Berhan A, et al. Magnitude of antiretroviral drug toxicity in adult HIV patients in Ethiopia: A cohort study at seven teaching Hospitals. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2017;27:39‐52. 10.4314/ejhs.v27i1.5s [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Abaissa SG, Fekade D, Feleke Y, Seboxa T, Diro E. Adverse drug reactions associated with antiretroviral treatment among adult Ethiopian patients in a tertiary Hospital. Ethiop Med J. 2012;50(2):107‐113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nasir BB, Berha AB, Gebrewold MA, Yifru YM, Engidawork E, Woldu MA. Drug therapy problems and treatment satisfaction among ambulatory patients with Epilepsy in a Specialized Hospital in Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2020;15(1):1‐12. 10.1371/journal.pone.0227359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yadesa TM, Gudina EK, Angamo MT. Antimicrobial use‐related problems and predictors among hospitalized medical in‐patients in Southwest Ethiopia: Prospective observational study. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):1‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tigabu B, Daba D, Habte B. Drug‐related problems among medical ward patients in Jimma University specialized hospital, Southwest Ethiopia. JRPP. 2014;3(1):1 10.4103/2279-042x.132702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tefera GM, Feyisa BB, Kebede TM. Antimicrobial use–related problems and their costs in surgery ward of Jimma University Medical Center: Prospective observational study. PLoS One. 2019;14(5):1‐15. 10.1371/journal.pone.0216770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ayalew M, Megersa T, Mengistu Y. Drug‐related problems in medical wards of Tikur anbessa specialized hospital, Ethiopia . JRPP. 2015;4(4):216‐221. 10.4103/2279-042x.167048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Belayneh YM, Amberbir G, Agalu A. A prospective observational study of drug therapy problems in medical ward of a referral hospital in Northeast Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):1‐7. 10.1186/s12913-018-3612-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hailu BY, Berhe DF, Gudina EK, Gidey K, Getachew M. Drug related problems in admitted geriatric patients: The impact of clinical pharmacist interventions. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):1‐8. 10.1186/s12877-020-1413-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kebede B, Kefale Y. Medication error patients admitted to medical ward in primary hospital, Ethiopia : Prospective observational study pharmaceutical care & health systems. J Pharma Care Heal SYS. 2019;6(20):1‐6. 10.35248/2376-0419.19.6.205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mekonnen AB, Yesuf EA, Odegard PS, Wega SS. Implementing ward based clinical pharmacy services in an Ethiopian University Hospital. Pharmacy Practice (Internet). 2013;11(1):51‐57. 10.4321/s1886-36552013000100009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Abdulmalik H, Tadiwos Y, Legese N. Assessment of drug‐related problems among type 2 diabetic patients on follow up at Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital, Harar, Eastern Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12(1):4‐9. 10.1186/s13104-019-4760-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ayele Y, Melaku K, Dechasa M, Ayalew MB, Horsa BA. Assessment of drug related problems among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with hypertension in Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital, Harar, Eastern Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):1‐5. 10.1186/s13104-018-3838-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Koyra HC, Tuka SB, Tufa EG. Epidemiology and predictors of drug therapy problems among type 2 diabetic patients at Wolaita Soddo University Teaching Hospital, Southern Ethiopia. AJPS. 2017;5(2):40‐48. 10.12691/ajps-5-2-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kindie E, Anteneh ZA, Worku E. Time to development of adverse drug reactions and associated factors among adult HIV positive patients on antiretroviral treatment in Bahir Dar City, Northwest Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2017;12(12):1‐12. 10.1371/journal.pone.0189322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Merid MW, Gezie LD, Kassa GM, Muluneh AG, Akalu TY, Yenit MK. Incidence and predictors of major adverse drug events among drug‐resistant tuberculosis patients on second‐line anti‐tuberculosis treatment in Amhara regional state public hospitals; Ethiopia: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):1‐12. 10.1186/s12879-019-3919-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Weldegebreal AS, Tezeta F, Mehari AT, Gashaw W, Dessale KT, Legesse NY. Assessment of drug therapy problem and associated factors among adult hypertensive patients at Ayder Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Northern Ethiopia. Afr Health Sci. 2019;19(3):2571‐2579. 10.4314/ahs.v19i3.33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Weldegebreal F, Mitiku H, Teklemariam Z. Magnitude of adverse drug reaction and associated factors among HIV‐infected adults on antiretroviral therapy in Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital, Eastern Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;24:1‐11. 10.11604/pamj.2016.24.255.8356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Angamo MT, Curtain CM, Chalmers L, Yilma D, Bereznicki L. Predictors of adverse drug reaction‐related hospitalisation in Southwest Ethiopia: A prospective cross‐sectional study. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):1‐17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Abdela O, Bhagavathula A, Getachew H, Kelifa Y. Risk factors for developing drug‐related problems in patients with cardiovascular diseases attending Gondar University Hospital, Ethiopia. JPBS. 2016;8(4):289‐295. 10.4103/0975-7406.199335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gelchu T, Abdela J. Drug therapy problems among patients with cardiovascular disease admitted to the medical ward and had a follow‐up at the ambulatory clinic of Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital: The case of a tertiary hospital in Eastern Ethiopia. SAGE Open Med. 2019;7:205031211986040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Meknonnen GB, Birarra MK, Tekle MT, Bhagavathula AS. Assessment of drug related problems and its associated factors among medical ward patients in University of Gondar Teaching Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: A prospective cross‐sectional study. JBCP. 2017;8(September):S016‐S021. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe . https://www.pcne.org/who‐are‐we. Accessed May 28, 2020.

- 39. Hussen A, Daba FB. Drug therapy problems and their predictors among hypertensive patients on follow up in Dil‐Chora Referral Hospital, Dire‐Dawa, Ethiopia. Ijpsr. 2017;8(6):2712‐2719. 10.13040/IJPSR.0975-8232.8(6).2712-19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yimama M, Jarso H, Desse TA. Determinants of drug‐related problems among ambulatory type 2 diabetes patients with hypertension comorbidity in Southwest Ethiopia: A prospective cross sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11(1):1‐6. 10.1186/s13104-018-3785-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hussein M. Assessment of drug related problems among hypertensive patients on follow up in Adama Hospital Medical College, East Ethiopia . CPB. 2014;3(2):2‐7. 10.4172/2167-065x.1000122 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Niriayo YL, Kumela K, Kassa TD, Angamo MT. Drug therapy problems and contributing factors in the management of heart failure patients in Jimma University Specialized Hospital, Southwest Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):1‐14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Demoz GT, Berha AB, Woldu MA, Yifter H, Shibeshi W, Engidawork E. Drug therapy problems, medication adherence and treatment satisfaction among diabetic patients on follow‐up care at Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):1‐17. 10.1371/journal.pone.0222985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Garedow AW, Mulisa Bobasa E, Desalegn Wolide A, et al. Drug‐related problems and associated factors among patients admitted with chronic Kidney disease at Jimma University medical center, Jimma Zone, Jimma, Southwest Ethiopia: a hospital‐based prospective observational study. IJN. 2019;2019 10.1155/2019/1504371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gizaw K. Drug related problems and contributing factors among adult ambulatory patients with Cardiovascular diseases at Gebretsadik General Hospital, Bonga, South west Ethiopia. JNSR. 2017;7(1). [Google Scholar]

- 46. Belachew SA, Erku DA, Mekuria AB, Gebresillassie BM. Pattern of chemotherapy‐related adverse effects among adult cancer patients treated at Gondar University Referral Hospital, Ethiopia: A crosssectional study. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2016;8:83‐90. 10.2147/DHPS.S116924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bezabhe WM, Bereznicki LR, Chalmers L, et al. Adverse drug reactions and clinical outcomes in patients initiated on antiretroviral therapy: A prospective cohort study from Ethiopia. Drug Saf. 2015;38(7):629‐639. 10.1007/s40264-015-0295-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30(2):239‐245. 10.1038/clpt.1981.154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ayalew MB, Tegegn HG, Abdela OA. Drug related hospital admissions; A systematic review of the recent literature. Bull Emerg Trauma. 2019;7(4):339‐346. 10.29252/beat-070401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wilbur K, Hazi H, El‐bedawi A. Drug‐related hospital visits and admissions associated with laboratory or physiologic abnormalities: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2013;8(6): 10.1371/journal.pone.0066803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bilal AI, Tilahun Z, Gebretekle GB, Ayalneh B, Hailemeskel B, Engidawork E. Current status, challenges and the way forward for clinical pharmacy service in Ethiopian public hospitals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;1–11: 10.1186/s12913-017-2305-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hambisa S, Abie A, Nureye D, Yimam M. Attitudes, opportunities, and challenges for clinical pharmacy services in Mizan‐Tepi University Teaching Hospital, Southwest Ethiopia : Health Care Providers ’ Perspective. Adv Pharmacol Pharm Sci. 2020;2020:1‐6. 10.1155/2020/5415290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ramanath K, Nedumballi S. Assessment of medication‐related problems in geriatric patients of a rural tertiary care hospital. J Young Pharm. 2012;4(4):273‐278. 10.4103/0975-1483.104372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fialová D, Onder G. Medication errors in elderly people: contributing factors and future perspectives. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;67(6):641‐645. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03419.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Karlsson Lind L, von Euler M, Korkmaz S, Schenck‐Gustafsson K. Sex differences in drugs: the development of a comprehensive knowledge base to improve gender awareness prescribing. Biol Sex Differ. 2017;8(1):32 10.1186/s13293-017-0155-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bethi Y, Shewade DG, Dutta TK, Gitanjali B. Prevalence and predictors of potential drug‐drug interactions in patients of internal medicine wards of a tertiary care hospital in India. Eur J Hosp Pharm Sci Pract. 2018;25(6):317‐321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Snyder ME, Frail CK, Jaynes H, Pater KS, Zillich AJ. Predictors of medication‐related problems among medicaid patients participating in a pharmacist‐provided telephonic medication therapy management program. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34(10):1022‐1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Angamo MT, Chalmers L, Curtain CM, Bereznicki LR. Adverse‐drug‐reaction‐related hospitalisations in developed and developing countries: A review of prevalence and contributing factors. Drug Saf. 2016;39(9):847‐857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material

Appendix two

Data Availability Statement

The extracted data are available if required.