Abstract

Background

Depression is a robust predictor of nonadherence to antiretroviral (ARV) therapy, which is essential to prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT). Women in resource-limited settings face additional barriers to PMTCT adherence. Although structural barriers may be minimized by social support, depression and stigma may impede access to this support.

Purpose

To better understand modifiable factors that contribute to PMTCT adherence and inform intervention development.

Methods

We tested an ARV adherence model using data from 200 pregnant women enrolled in PMTCT (median age 28), who completed a third-trimester interview. Adherence scores were created using principal components analysis based on four questions assessing 30-day adherence. We used path analysis to assess (i) depression and stigma as predictors of social support and then (ii) the combined associations of depression, stigma, social support, and structural barriers with adherence.

Results

Elevated depressive symptoms were directly associated with significantly lower adherence (est = −8.60, 95% confidence interval [−15.02, −2.18], p < .01). Individuals with increased stigma and depression were significantly less likely to utilize social support (p < .01, for both), and higher social support was associated with increased adherence (est = 7.42, 95% confidence interval [2.29, 12.58], p < .01). Structural barriers, defined by income (p = .55) and time spent traveling to clinic (p = .31), did not predict adherence.

Conclusions

Depression and social support may play an important role in adherence to PMTCT care. Pregnant women living with HIV with elevated depressive symptoms and high levels of stigma may suffer from low social support. In PMTCT programs, maximizing adherence may require effective identification and treatment of depression and stigma, as well as enhancing social support.

Keywords: HIV, Vertical transmission, Adherence, Social support, Stigma, Structural barriers, Depression, Pregnancy

Pregnant South African women living with HIV who experienced more depressive symptoms and stigma were less likely to report social support, which may impact antiretroviral medication adherence.

Introduction

Sub-Saharan Africa remains the epicenter of the HIV pandemic, with 25.8 million people living with HIV in the region in 2014, representing 66% of all new HIV infections globally [1]. The highest HIV prevalence and incidence in South Africa in 2012 was among Black African women aged 20–34 (31.6% and 4.5%, respectively) [2]. Data obtained from South African antenatal clinics suggest especially elevated rates of HIV infection among pregnant women, with a national survey documenting rates as high as 42.8% among women presenting for antenatal care [3]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends options to reduce the risk of vertical transmission that include providing antiretroviral (ARV) medications to mothers and infants during pregnancy, labor and the postpartum period, and offering life-long ARV treatment to pregnant women living with HIV regardless of their CD4 count [4]. Using HIV testing, highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), cesarean section (when needed), and education about breastfeeding and pediatric care, the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV has proven to be successful at nearly eliminating vertical transmission in high-income countries [5, 6]. However, in resource-limited settings, it becomes increasingly difficult for pregnant women living with HIV to adhere to PMTCT interventions without falling out of the treatment cascade. Continued efforts are needed to reach women during pregnancy, as South Africa had the greatest number of new infections among women globally between 2009 and 2015 [7].

It is important to understand the role of modifiable, behavioral factors associated with nonadherence to PMTCT to improve the design and uptake of interventions. Approximately 260,000 women living with HIV in South Africa gave birth in 2013 and approximately 20,000 children became infected with HIV [8]. Although South Africa has achieved a significant reduction in new HIV infections among children, these reductions have still fallen short of UNAIDS goals of a 90% decrease in infections by 2015. Modeling studies have proposed that without increasing rates of adherence to PMTCT protocols, we will not see significant reductions in vertical transmission [9]. Alone, depression is a significant barrier to adherence, but for women in the perinatal period, adherence may be compromised further by high levels of stigma and inability to effectively use social support, particularly in a resource-limited setting.

Depression is recognized as a robust predictor of nonadherence to ARVs [10–12], though remains understudied as a barrier to adherence to ARVs during the perinatal period, a time of increased risk for depression [13]. A recent review suggests depression rates of 4%–17% during pregnancy and 3%–48% in the postpartum period in sub-Saharan Africa, with the highest rates reported in South Africa [14]. More recent studies suggest that depression rates may be as high as 47% during pregnancy among women in South Africa [15–17].

Depression has also been associated with negative views about the health care system and fear of stigmatization among a sample of women receiving an HIV test during antenatal care [18]. HIV-related stigma remains present in sub-Saharan Africa and represents yet another factor influencing depression in this setting [19, 20]. A review of the literature found that stigma is a barrier to completing the PMTCT cascade, and models suggest that stigma is significantly related to rates of infant HIV infection [21]. The complexities of managing both pregnancy and a highly stigmatized chronic illness in a resource-limited setting may predispose women to additional vulnerability for mood disturbance. Furthermore, pregnancy and postpartum health care behaviors may be especially susceptible to stigma, as many interventions designed to help protect infants from acquiring HIV (e.g., regular PMTCT appointments, delivering in a hospital, modifications to breastfeeding behavior) may lead to inadvertent disclosure of serostatus.

In addition to stigma, women living with HIV in resource-limited settings must negotiate additional complex barriers to PMTCT adherence including structural barriers to health care and lack of social support. Structural barriers that could result in under attendance may include having to travel significant distances to clinics, expensive transport fare, lack of childcare resources, inability to take time off work, and limited regular availability of ARVs [22, 23]. Social support may yield money to borrow for transport or help with childcare. However, pregnancy discovery often changes relationship dynamics with family members and pregnancy partners, which can negatively affect social support.

Social support is emerging as a critical component of adherence to health behaviors in resource-limited settings and among individuals living with HIV [24, 25]. Bangsberg and Deeks [22] (see Figure 1) suggest that individuals in resource-limited settings need to rely on their social supports to overcome structural barriers to ART adherence. HIV-related stigma may jeopardize one’s ability to leverage social support because individuals may be reluctant to disclose their HIV status to their social network for fear of rejection, discrimination, or violence. Lack of disclosure may thus affect adherence to health care behaviors such as attending clinic appointments and taking ARVs. Symptoms of depression (which we have added to the model given high rates of perinatal depression among women living with HIV, as described earlier), including social isolation, hopelessness, or decreased problem solving, may represent yet another barrier to the utilization of social support. The experience of stigma may contribute to depressive symptoms, and depressive symptoms might heighten the presence of internalized stigma. Previous research suggests that major depression is associated with decreased social support and greater challenges in social relationships, particularly with spouses and relatives [26]. For example, symptoms of depression can result in avoidant coping, versus problem-solving-based strategies. Feelings of hopeless and guilt may also make it difficult to access social support.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for adherence to prevention of mother-to-child transmission (based on work by Bangsberg and Deeks [22]). The original model was expanded to include depression.

Pregnant women living with HIV in low- and middle-income countries are an extremely vulnerable population with specific needs and continue to experience less than optimal health outcomes [27]. Although pregnancy has historically been conceptualized as a time of joy, it is actually a time of great uncertainty for women living with HIV [28]. Women need to tolerate the uncertainty of not learning their infant’s HIV status until several weeks after birth, and maternal and infant mortality rates are high in low- and middle-income countries [29]. More frequent engagement in the health care system or decisions around breastfeeding may inadvertently “out” one’s HIV status; this can be particularly distressing in a setting where HIV stigma is high. Although depression is a powerful predictor of nonadherence in nonpregnant samples, it may function differently in this setting where nonadherence can lead to vertical transmission. Social support may also function differently in pregnant populations, as willingness to provide support or the availability of support may be different in the context of pregnancy. Thus, the need to understand how these variables may operate during pregnancy is crucial to the development of interventions that will support infant and maternal well-being.

These analyses focus on examining relationships among perinatal depression, stigma, social support, structural factors, and adherence to ARV therapy during pregnancy among women living with HIV in the province of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. We hypothesized (i) that participants who met the threshold for depression would have lower rates of ARV adherence; (ii) that social support would moderate the relationship between structural barriers and ARV adherence such that for those participants with high levels of social support, the magnitude of the relationship between structural barriers and adherence to ARVs would be attenuated and for those with low levels of social support, the relationship would be stronger; and (iii) that participants who met the threshold for depression would have lower levels of social support and that participants with greater levels of stigma would have lower levels of social support.

Methods

Participants

From May 10, 2013 through June 2, 2014, project staff recruited participants enrolled in PMTCT at a district hospital in a large urban township in eThekwini District, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Because the aims of the study involved studying adherence among pregnant women, the sample was limited to cisgender women. All women were systematically screened for eligibility by a racially and ethnically concordant female research assistant fluent in English and isiZulu, and written consent was obtained from all study participants. We recruited women who were aged 18–45 and fluent in English or isiZulu; who were in their third trimester of pregnancy (≥28 weeks); who self-reported known HIV-positive status; who were receiving antenatal care at the district hospital; and who had access to a phone and were willing to be contacted by phone. Participants were also interviewed at approximately 6 weeks postpartum; as the focus of these analyses is on adherence during pregnancy, those data are not used here.

Participants were compensated 70 ZAR (approximately $10 USD) for their time at the conclusion of each interview. All study procedures were approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Witwatersrand (Johannesburg, South Africa) and the Partners (Massachusetts General Hospital) Human Research Committee (Boston, MA).

Data Collection

Participants were interviewed at or after 28 weeks of pregnancy and asked to respond to questions about sociodemographics, depression, stigma, social support, structural barriers to PMTCT, and ARV adherence with a racially and ethnically concordant interviewer in a private room at the recruitment site. Interviews lasted approximately 45–60 min. Participants completed a second visit around 6 weeks postpartum, though these analyses are focused on data collected during pregnancy only.

Measures

All measures that were not readily available in isiZulu were translated and back-translated by independent individuals, and piloted before use.

Sociodemographic data included questions about age, length of HIV diagnosis, length of relationship and relationship status with the father of the current pregnancy, partner’s HIV status, fertility desire, education level, employment status, mode of transportation to clinic, time spent traveling to the clinic, and monthly income.

Depression symptom severity was measured using a modified version of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL-15) for depression [30]. Based on previous studies using HSCL in Uganda, we included a 16th item, “Feeling like I don’t care about my health” [31–33]. Each symptom was scored on a 4-item Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (extremely), and the total depression severity score was calculated as the mean of the 16 items, with higher scores indicating greater depression symptom severity. We also used a dichotomous measure of “probable depression” defined as an HSCL score > 1.75, a commonly used threshold for a positive depression screen [30, 33–41]. The depression subscale of HSCL has been used to assess depression in general population samples and among people living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa, including women [30–40, 42, 43].

HIV stigma was measured using the Internalized AIDS-Related Stigma Scale [44]. This six-item scale measures the construct of internalized AIDS-related stigma among people living with HIV. Items reflecting self-defacing beliefs and negative perceptions of people living with HIV/AIDS are scored dichotomously as “Agree” (1) or “Disagree” (0). Total scores are calculated as the sum of the items and range from 0 to 6, with higher scores indicating greater internalized stigma. This scale has been validated in multiple settings, including Cape Town, South Africa [32, 44].

A modified version of the Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire was used to measure social support [45, 46]. This 10-item scale evaluates the availability of emotional and tangible support. Participants were asked to rate how strongly they agree with statements such as “I get useful advice about important things in my life” and “I get help when I need transportation” with responses on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (as much as I would like). Higher scores reflect higher perceived social support. This scale was initially validated in family medicine patients [46] and has been further validated in English and Spanish among patients in primary care settings and patients with severe mental illness [47–49]. It has been employed to measure perceived social support among pregnant and postpartum women in the USA, Europe, and sub-Saharan Africa [45, 50, 51].

Data on structural barriers to care were also collected, which included time spent traveling to clinic and monthly income. Income (in the South African Rand) was defined as a four-category variable (0–499, 500–999, 1,000–1,999, and ≥2,000) for the purposes of summarizing characteristics and analyzed in two categories (0–999 vs. ≥1,000).

The assessment of self-reported ARV adherence was informed by the work of Lu et al. [52] and consisted of four questions that comprised different response formats, including frequency, percent, and rating responses. Participants were asked to rate their ability to take their ARVs as prescribed in the past month on a 6-point Likert-type scale (1 = very poor, 6 = excellent), how often they took their ARVs in the past month on a 6-point Likert-type scale (1 = none of the time, 6 = all of the time), a 30-day visual analog scale to assess overall adherence was administered, and lastly, participants were asked about the last time they missed a dose of ARVs (1 = today, 7 = never). All of these questions rely on a 30-day recall period as this has been shown to better correlate with more “objective” adherence data, such as the medication event monitoring system [52, 53]. Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to create a weighted sum of the responses to the four questions assessing adherence over the past 30 days. These weights were used to create a standardized adherence score ranging from 0 to 100 [54].

Data Preparation

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Partners Health-Care.

Data Analyses

Data analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.4 [55]. One participant was missing the depression score (due to missing a response to question 14 regarding “feeling worthless” from the Hopkins Symptom Checklist) and three were missing the stigma score (due to missing a response to question 4 “I am ashamed that I am HIV positive” from the AIDS-related stigma section). In secondary definitions, we imputed missing responses with the average of non-missing responses and used these imputed responses to calculate the scores; sensitivity analyses repeated the methods described later using the imputed scores, and conclusions were similar (results not shown).

Our primary definition of adherence was an adherence score created as described in Reynolds et al. [54] using PCA on the response to the four self-reported adherence questions [56, 57]. We examined both nonstandardized and standardized PCA and rescaled the standardized PCA to a score ranging from 0 to 100. Depression, social support, income, and time spent traveling were all examined as predictors of the primary adherence score in separate, univariable linear regression models. Path analysis methods were used to combine quantitative results of these linear regression models in the framework designated in Figure 1 [58, 59], first assessing the relationship between depression, stigma, social support, and structural barriers and adherence and then assessing the relationship with stigma and depression directly with social support utilization. Interactions between social support and the structural and economic barriers were also assessed but ultimately dropped because they were found to be not significant (social support interaction with travel time, p = .24, and with income p = .32; analyses not shown). The estimated coefficient for the extraneous variables not included in the model, estimated as , where R2 is the proportion of the variation in the outcome that is accounted for by the variation in the predictor, is also reported.

Power calculations were based on established rates of depression among pregnant (4%–17%) and postpartum women (3%–48%) in resource-limited settings, including South Africa [60]. One hundred and eighty-one participants would be required to detect a minimum hypothesized difference in depression rates between those who were adherent versus nonadherent (20% vs. 30%), with more than 90% power using a one-sided exact Binomial test with a Type I error rate of 0.05. Prior to analyzing the data, we modified the original plan based on Reynolds et al. [54] and derived a continuous adherence score. This is reflected in Methods.

Results

Data were collected from 200 participants (median age [Q1, Q3] = 28 years [24, 31]), meeting the study inclusion criteria. One hundred and ninety-nine participants had complete data on the outcome variable of adherence and thus were included in these analyses. The majority (73%) of participants reported current unemployment, and most were recently diagnosed with HIV (median number of months from interview [Q1, Q3] = 8 [3, 48]). Forty percent of participants desired the current pregnancy now, sooner, or later, whereas the majority were either ambivalent or unsure or reported that the pregnancy was unwanted. Additional descriptive data are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Participants

| Variable | Median (IQR) or |

|---|---|

| Number (%) | |

| Age | 28 (24, 31) |

| Months from HIV diagnosis to interview date | 7.5 (3, 47.5) |

| Length of relationship with father of current pregnancy (in years) | 3.5 (1.9, 5.8) |

| Still in relationship with father of current pregnancy | |

| No | 6 (3%) |

| Yes | 194 (97%) |

| Disclosure to partner | |

| No | 43 (22%) |

| Yes | 154 (77%) |

| Don’t know | 3 (2%) |

| Partners’ HIV status | |

| Positive | 70 (35%) |

| Negative | 30 (15%) |

| Don’t know | 100 (50%) |

| Fertility desire | |

| Did not want, did not care, do not know | 120 (60%) |

| Sooner, later, now | 80 (40%) |

| Fertility desire (disaggregated) | |

| Did not want | 112 (56%) |

| Did not care | 3 (2%) |

| Don’t know | 5 (3%) |

| Sooner | 28 (14%) |

| Later | 41 (21%) |

| Now | 11 (6%) |

| Education | |

| None/primary/secondary | 193 (97%) |

| Matric/post-secondary | 7 (4%) |

| Current employment | |

| Not employed | 145 (73%) |

| Full-time employed | 33 (17%) |

| Part-time employed | 20 (10%) |

| Self-employed | 2 (1%) |

| Mode of transportation | |

| Walking | 64 (32%) |

| Taxi | 133 (66%) |

| Car | 1 (1%) |

| Missing | 2 (1%) |

| Depression | |

| Median depression score | 1.375 (1.25, 1.75) |

| Dichotomous depression score | |

| ≤1.75 | 151 (76%) |

| >1.75 | 48 (24%) |

| Missing | 1 (1%) |

| Social support | |

| I get visits from friends and relatives | 4 (3, 4) |

| I get useful advice about important things in my life | 4 (4, 4) |

| I get chances to talk to someone about problems at work or with my housework | 4 (4, 4) |

| I get chances to talk to someone I trust about my personal and family problems | 4 (4, 4) |

| I have people who care what happens to me | 4 (4, 4) |

| I get love and affection | 4 (4, 4) |

| I get help around the house | 4 (4, 4) |

| I get help with money in an emergency | 4 (3, 4) |

| I get help when I need transportation | 3 (1, 4) |

| I get help when I am sick | 4 (4, 4) |

| Social Support score | 3.6 (3.15, 4) |

| Stigma | |

| Stigma score | 2 (1, 3) |

| Structural barriers | |

| Time spent traveling (min) | 30 (15, 30) |

| Monthly income | |

| 0–499 | 63 (32%) |

| 500–999 | 73 (37%) |

| 1,000–1,999 | 41 (21%) |

| ≥2,000 | 23 (12%) |

| Adherence | |

| Rate ability to take ARVs as prescribed in past 30 days | |

| Very poor | 1 (1%) |

| Poor | 3 (2%) |

| Fair | 2 (1%) |

| Good | 95 (48%) |

| Very good | 52 (26%) |

| Excellent | 46 (23%) |

| Missing | 1 (1%) |

| In the past 30 days did you take all your ARVs | |

| A little of the time | 2 (1%) |

| Some of the time | 1 (1%) |

| A good bit of the time | 4 (2%) |

| Most of the time | 39 (20%) |

| All of the time | 154 (77%) |

| Indicate how much you have taken your ARVs in last 3–4 weeks | |

| ≤80% | 21 (11%) |

| 85%–90% | 38 (19%) |

| 91%–99% | 41 (21%) |

| 100% | 100 (50%) |

| Last missed dose of ARVs | |

| Today | 1 (1%) |

| Yesterday | 6 (3%) |

| Earlier this week | 2 (1%) |

| Last week | 26 (13%) |

| Less than a month ago | 12 (6%) |

| More than a month ago | 5 (3%) |

| Never | 148 (74%) |

IQR, interquartile range; ARV, antiretroviral.

Self-reported Adherence, Depression, Social, Support, Stigma, and Structural Barriers to Care

Self-reported adherence for the sample as a whole was high across all four questions (see Table 1). The result of the PCA for the four self-reported adherence questions is presented in Table 2. The only principal component with an eigenvalue > 1.0 is the first; this principal component explains 56% of the variation among the four adherence questions. As described earlier [54], we rescaled the adherence score to range from 0 to 100 to aid interpretability. Median adherence for the sample was 91.17% (Q1, Q3 = 75.29%, 95.57%). Twenty-four percent of the sample met criteria for elevated depression symptoms using the HSCL score of >1.75. Overall, the sample reported relatively low levels of stigma (median [Q1, Q3] = 2 [1, 3]) and moderate levels of social support (median [Q1, Q3] = 3.6 [3.2, 4.0]). The most common mode of transportation to clinic was taxi (67%). Eighty-two (41%) of participants had a travel time of 25 min or less; the remaining 118 (59%) had a travel time of at least 30 min, with 81 (41%) reporting a travel time from 30 to <40 min, and 15 (8%) reporting a travel time of 40 to <50 min. Most (68%) of the participants reported monthly incomes well below the poverty line at ≤999 Rand ($72).

Table 2.

Result of Principal Component Analysis for Self-reported Adherence Questions

| Factor | Eigenvalue | % of variance | Cumulative % of variance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.23 | 56 | 56 |

| 2 | 0.86 | 21 | 77 |

| 3 | 0.62 | 15 | 93 |

| 4 | 0.30 | 7 | 100 |

Predicting Adherence: Individual Relationships

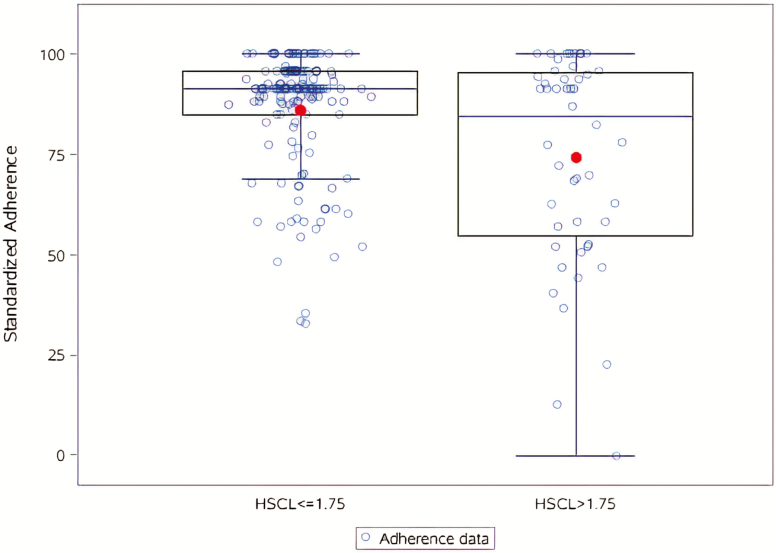

Depression, social support, income, and time spent traveling were all assessed separately as predictors of adherence. As depicted in Figure 2, depression predicted adherence, with participants who met the scoring cutoff for elevated depressive symptoms having significantly lower and greater variability in adherence scores than those not meeting the depression cutoff (est = −11.7, 95% confidence interval [CI] [−17.6, −5.8], p < .01). Sensitivity analyses included depression as a continuous score, rather than dichotomized; conclusions were similar (est = −12.8, 95% CI [−17.4, −8.2]). Increased social support was significantly associated with increased adherence (est = 9.9, 95% CI [5.3, 14.4], p < .01). In these described models, similar amounts of variability are explained (adjusted R2 for the depression cutoff and the social support models were .07 and .08, respectively). The overall association between income and adherence was not significant (est = 1.70, 95% CI [−3.93, 7.34], p = .55), nor was the association between time spent traveling and adherence (est = −0.07, 95% CI [−0.20, 0.06], p = .31).

Figure 2.

The relationship between depressive symptoms, as measured by the depression subscale of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL-15), and adherence. Depression was a predictor of adherence (est = −11.7, 95% confidence interval: −17.6, −5.8, p < .01).

Full Relationships Between All Factors

In the path analysis, social support remained positively associated with adherence (est = 7.43, 95% CI [2.29, 12.58], p < .01), and depression was negatively associated with adherence (est = −8.60, 95% CI [−15.02, −2.18], p < .01), whereas stigma, time spent traveling, and income were not significantly associated with adherence (p = .79, .17, and .99, respectively). Both stigma and depression were significantly associated with social support as well (p < .01, for both). In addition, stigma and depression were positively correlated with each other (r = .25, p < .01). The results of these analyses are mapped onto our original conceptual model (Figure 1) in Figure 3. The path coefficient from extraneous variables to adherence was 0.94, and the path coefficient from extraneous variables to social support was 0.90.

Figure 3.

Quantitative results from path analysis of prevention of mother-to-child transmission adherence barriers.

Discussion

The effectiveness of PMTCT in eliminating vertical transmission of HIV can be compromised by poor adherence. Pregnant women living with HIV experience unique challenges to adherence; thus, it is important to identify modifiable factors that influence PMTCT adherence to develop and implement interventions to optimize the health of mothers with HIV and their children. We tested an expanded model of adherence to PMTCT developed by Bangsberg and Deeks [22]. The original model posited that structural barriers to care can impede adherence to ARVs in resource-limited settings, but accessible social support could mitigate the impact of those barriers. We added depression to the model as depression rates are high in South Africa during pregnancy and postpartum and, in addition to stigma, may make it difficult to access social support [61]. Furthermore, depression as a barrier to adherence to ARVs during pregnancy remains understudied in this population.

In our sample, overall adherence to ARVs was high relative to that observed in other studies in KwaZulu-Natal; for example, 61% of antenatal women in a sample of 94 [62] and 68% of male and female patients in a sample of 146 [63] reported greater than 95% adherence to ARVs. Nevertheless, adherence in our sample was lower than in Peltzer et al. [64], which reported 82.9% of patients endorsing greater than 95% adherence. Twenty-four percent of the sample met our criteria for elevated levels of depressive symptoms, which is consistent with previous literature [15, 18, 65, 66], and represents a substantial negative influence on the well-being of pregnant women in this setting. Also, consistent with previous literature is the relationship between depression and adherence [10–12], with those meeting criteria for elevated depressive symptoms having lower self-reported adherence to ARVs; this reinforces our understanding of psychosocial factors influencing adherence to ARVs among perinatal populations, which has been generally understudied.

Although our hypothesized relationships between structural barriers to care and adherence were not supported by the data, social support alone did predict adherence. The social support scale used in this study measured both emotional and instrumental support. This finding is consistent with recent intervention literature documenting success with promoting ARV adherence in the context of PMTCT by engaging couples [67–70]. The results of couple interventions suggest that engaging pregnant women and their pregnancy partners is effective at improving PMTCT adherence, in part by improving social support [71–73]. Although our study was not prospective in nature, participants with increased depressive symptoms and higher levels of stigma reported less social support, which may suggest that women are less likely to seek or be offered support from their family, friends, and community because they anticipate rejection due to their HIV status, or symptoms of depression make it difficult to identify and access support. The absence of social support coupled with stigma can exacerbate the experience of depression and/or contribute further to symptoms of depression [19, 74, 75], including social isolation and loneliness [66].

Finally, overall levels of HIV-related stigma for the sample were lower than expected given previously documented high rates of stigma in this community [19, 20]. The majority of participants lived below the poverty line and traveled approximately 30 min by taxi to get to clinic. This is notable as the health care system in South Africa is designed, so that individuals can receive health care services proximate to their home. The fact that participants were very likely traveling outside of their catchment area suggests that they may have been worried about stigma and inadvertent disclosure, or were traveling to receive what was perceived as better care. Thus, a measure of internalized stigma may not accurately capture the stigma experience for participants, who may be more concerned about perceived or anticipated stigma.

The present study has some limitations. Our sampling strategy may have caused us to recruit individuals who were more likely to report high adherence to ARVs, and we recruited only women who were at least somewhat engaged in antenatal care; women who do not engage in antenatal care at all may have different outcomes. Second, we lacked an objective measure of adherence to ARVs, and thus our assessment of this construct may have been subject to recall or social desirability biases. The study was originally powered to examine the relationship between depression and adherence, though this is only one of the analyses conducted in this manuscript. Thus, the results of analyses may be best framed as hypotheses generating. Lastly, the absence of relationships between structural barriers to care and adherence may reflect our inability to capture other relevant structural barriers, such as food insecurity. The large path coefficient for extraneous variables in the model for adherence indicated the large amount of variability in adherence that is not accounted for in our current model indicates that work remains to be done in how factors associated with adherence are identified and assessed. Future research should measure structural barriers to care more comprehensively (e.g., work leave policy, cost and availability of transportation, food insecurity) to better understand how structural factors may affect adherence behaviors during the perinatal period in this high-risk population. As noted above, partner engagement is emerging as an important vector by which we may improve adherence to PMTCT. Future studies may also wish to collect data on the experience of stigma, social support, and structural barriers among partners as well. Lastly, our inability to detect certain effects may be due in part to overall low levels of nonadherence, stigma, and structural barriers as reported by the sample.

Conclusions

This study provides evidence that depressive symptoms and lack of social support probably play an important role in managing adherence to ARVs during pregnancy and highlights the intersecting role of depressive symptoms, stigma, and social support in outcomes for this population. Elevated levels of depressive symptoms are commonplace among both individuals living with HIV and reproductive-age women, as are stigma and inadequate social support. High levels of adherence to ARVs during pregnancy are essential to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV and to preserve the health of the mother. In addition to nonadherence to ARVs, the consequences of untreated depression have been associated with inadequate attendance at antenatal care visits, low birth weight, early gestational age, inadequate nutrition, worse overall infant health, maternal disability, and disordered maternal–infant interactions [76–80]. Future studies should examine interventions that target not only depressive symptoms, but also directly address issues associated with low levels of social support and high levels of stigma to support PMTCT adherence, and optimize the health of women living with HIV and their children.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the efforts of our participants and thank them for sharing their experiences with us. We also thank Faith Luthuli and Jocelyn Remmert for their assistance with project coordination, Ross Greener for his assistance with data cleaning, and Georgia Goodman for her assistance with manuscript preparation. We also thank Bethany Hedt, PhD, for her assistance with the analyses.

Funding

The funding for this project is as follows: National Institute of Mental Health (K23MH096651).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Authors’ Statement of Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contributions C.P., J.A.S., and N.M. performed the research. C.P., J.A.S., D.R.B., and S.A.S. designed the research study and contributed to interpretation of data. C.P. and K.B. analyzed the data. C.P. and J.N.C. contributed substantially to manuscript development.

Ethical Approval All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

References

- 1. UNAIDS. Executive Summary: How AIDS Changed Everything—MDG6: 15 Years, 15 Lessons of Hope From the AIDS Response. UNAIDS; 2015. Available at http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/MDG6_ExecutiveSummary_en.pdf. Accessibility verified January 2, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi L, et al. South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence, and Behaviour Survey 2012. Available at http://www.hsrc.ac.za/uploads/pageContent/4565/SABSSM%20IV%20LEO%20final.pdf. Accessibility verified January 2, 2019.

- 3. South Africa National Department of Health. The 2012 National Antenatal Sentinel HIV and Syphilis Prevalence Survey in South Africa. National Department of Health; 2012. Available at http://www.health-e.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/ASHIVHerp_Report2014_22May2014.pdf. Accessibility verified January 2, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization. HIV/AIDS. 2015. Available at http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs360/en/. Accessibility verified January 2, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Granich R, Crowley S, Vitoria M, et al. Highly active antiretroviral treatment as prevention of HIV transmission: Review of scientific evidence and update. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2010;5:298–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Panel on Treatment of HIV-Infected Pregnant Women and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission. Recommendations for Use of Antiretroviral Drugs in Pregnant HIV-1-Infected Women for Maternal Health and Interventions to Reduce Perinatal HIV Transmission in the United States 2015. Available at https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/perinatalgl.pdf. Accessibility verified January 2, 2019.

- 7. UNAIDS. On the Fast-track to an AIDS-Free Generation 2016. Available at http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/GlobalPlan2016_en.pdf. Accessibility verified January 2, 2019.

- 8. UNAIDS. Gap Report. Geneva, Switzerland; 2014. Available at http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/en/media/unaids/ contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2014/UNAIDS_Gap_report_en.pdf. Accessibility verified January 2, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Barker PM, Mphatswe W, Rollins N. Antiretroviral drugs in the cupboard are not enough: The impact of health systems’ performance on mother-to-child transmission of HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56:e45–e48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grant E, Logie D, Masura M, Gorman D, Murray SA. Factors facilitating and challenging access and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a township in the Zambian Copperbelt: A qualitative study. AIDS Care. 2008;20:1155–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Murray LK, Semrau K, McCurley E, et al. Barriers to acceptance and adherence of antiretroviral therapy in urban Zambian women: A qualitative study. AIDS Care. 2009;21:78–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sabin LL, Desilva MB, Hamer DH, et al. Barriers to adherence to antiretroviral medications among patients living with HIV in southern China: A qualitative study. AIDS Care. 2008;20:1242–1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Biaggi A, Conroy S, Pawlby S, Pariante CM. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2016;191:62–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sawyer A, Ayers S, Smith H. Pre- and postnatal psychological wellbeing in Africa: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2010;123:17–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rochat TJ, Tomlinson M, Bärnighausen T, Newell ML, Stein A. The prevalence and clinical presentation of antenatal depression in rural South Africa. J Affect Disord. 2011;135:362–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Manikkam L, Burns JK. Antenatal depression and its risk factors: An urban prevalence study in KwaZulu-Natal. S Afr Med J. 2012;102:940–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rotheram-Borus MJ, le Roux IM, Tomlinson M, et al. Philani Plus (+): A Mentor Mother community health worker home visiting program to improve maternal and infants’ outcomes. Prev Sci. 2011;12:372–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rochat TJ, Richter LM, Doll HA, Buthelezi NP, Tomkins A, Stein A. Depression among pregnant rural South African women undergoing HIV testing. JAMA. 2006;295:1376–1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Simbayi LC, Kalichman S, Strebel A, Cloete A, Henda N, Mqeketo A. Internalized stigma, discrimination, and depression among men and women living with HIV/AIDS in Cape Town, South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:1823–1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Peltzer K, Ramlagan S. Perceived stigma among patients receiving antiretroviral therapy: A prospective study in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2011;23:60–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Turan JM, Nyblade L. HIV-related stigma as a barrier to achievement of global PMTCT and maternal health goals: A review of the evidence. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:2528–2539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bangsberg DR, Deeks SG. Spending more to save more: Interventions to promote adherence. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:54–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Buchan I, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa and North America: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;296:679–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ware NC, Idoko J, Kaaya S, et al. Explaining adherence success in sub-Saharan Africa: An ethnographic study. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Coleman JS. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am J Sociol. 1988;94:S95–120. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wade TD, Kendler KS. The relationship between social support and major depression: Cross-sectional, longitudinal, and genetic perspectives. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2000;188:251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Momplaisir FM, Aaron E, Bossert L, et al. HIV care continuum outcomes of pregnant women living with HIV with and without depression. AIDS Care. 2018;30:1580–1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shannon M, Lee KA. HIV-infected mothers’ perceptions of uncertainty, stress, depression and social support during HIV viral testing of their infants. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2008;11:259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chilongozi D, Wang L, Brown L, et al. ; HIVNET 024 Study Team Morbidity and mortality among a cohort of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected and uninfected pregnant women and their infants from Malawi, Zambia, and Tanzania. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:808–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): A self-report symptom inventory. Behav Sci. 1974;19:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bolton P, Ndogoni L.. Cross-cultural Assessment of Trauma-Related Mental Illness Phase II. A Report of Research Conducted by World Vision Uganda and the Johns Hopkins University. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tsai AC, Weiser SD, Steward WT, et al. Evidence for the reliability and validity of the internalized AIDS-related stigma scale in rural Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:427–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kaida A, Matthews LT, Ashaba S, et al. Depression during pregnancy and the postpartum among HIV-infected women on antiretroviral therapy in Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;67(suppl 4):S179–S187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gupta R, Dandu M, Packel L, et al. Depression and HIV in Botswana: A population-based study on gender-specific socioeconomic and behavioral correlates. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kaaya SF, Fawzi MC, Mbwambo JK, Lee B, Msamanga GI, Fawzi W. Validity of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 amongst HIV-positive pregnant women in Tanzania. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106:9–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Psaros C, Haberer JE, Boum Y 2nd, et al. The factor structure and presentation of depression among HIV-positive adults in Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2015;19:27–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hatcher AM, Tsai AC, Kumbakumba E, et al. Sexual relationship power and depression among HIV-infected women in rural Uganda. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Martinez P, Andia I, Emenyonu N, et al. Alcohol use, depressive symptoms and the receipt of antiretroviral therapy in southwest Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:605–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tsai AC, Bangsberg DR, Frongillo EA, et al. Food insecurity, depression and the modifying role of social support among people living with HIV/AIDS in rural Uganda. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74:2012–2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tsai AC, Wolfe WR, Kumbakumba E, et al. Prospective study of the mental health consequences of sexual violence among women living with HIV in rural Uganda. J Interpers Violence. 2016;31:1531–1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Winokur A, Winokur DF, Rickels K, Cox DS. Symptoms of emotional distress in a family planning service: Stability over a four-week period. Br J Psychiatry. 1984;144:395–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kaaya SF, Blander J, Antelman G, et al. Randomized controlled trial evaluating the effect of an interactive group counseling intervention for HIV-positive women on prenatal depression and disclosure of HIV status. AIDS Care. 2013;25:854–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kagee A, Martin L. Symptoms of depression and anxiety among a sample of South African patients living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2010;22:159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Cloete A, Mthembu PP, Mkhonta RN, Ginindza T. Measuring AIDS stigmas in people living with HIV/AIDS: The Internalized AIDS-Related Stigma Scale. AIDS Care. 2009;21:87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Antelman G, Smith Fawzi MC, Kaaya S, et al. Predictors of HIV-1 serostatus disclosure: A prospective study among HIV-infected pregnant women in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. AIDS. 2001;15:1865–1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Broadhead WE, Gehlbach SH, de Gruy FV, Kaplan BH. The Duke-UNC functional social support questionnaire. Measurement of social support in family medicine patients. Med Care. 1988;26:709–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bellón Saameño JA, Delgado Sánchez A, Luna del Castillo JD, Lardelli Claret P. Validity and reliability of the Duke-UNC-11 questionnaire of functional social support. Atencion Primaria Soc Esp Med Fam Comunitaria. 1996;18(4):158–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. de la Revilla Ahumada L, Bailón E, de Dios Luna J, Delgado A, Prados MA, Fleitas L. Validation of a functional social support scale for use in the family doctor’s office. Atencion Primaria Soc Esp Med Fam Comunitaria. 1991;8(9):688–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mas-Expósito L, Amador-Campos JA, Gómez-Benito J, Lalucat-Jo L. Validation of the modified DUKE-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire in patients with schizophrenia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48:1675–1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gutiérrez-Zotes A, Labad J, Martín-Santos R, et al. Coping strategies and postpartum depressive symptoms: A structural equation modelling approach. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30:701–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Harley K, Eskenazi B. Time in the United States, social support and health behaviors during pregnancy among women of Mexican descent. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:3048–3061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lu M, Safren SA, Skolnik PR, et al. Optimal recall period and response task for self-reported HIV medication adherence. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:86–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wilson IB, Lee Y, Michaud J, Fowler FJ Jr, Rogers WH. Validation of a new three-item self-report measure for medication adherence. AIDS Behav. 2016;20:2700–2708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Reynolds NR, Sun J, Nagaraja HN, Gifford AL, Wu AW, Chesney MA. Optimizing measurement of self-reported adherence with the ACTG Adherence Questionnaire: A cross-protocol analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46:402–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. SAS Software. SAS Institute Inc. SAS, Cary, NC; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Safren SA, Biello KB, Smeaton L, et al. ; PEARLS (ACTG A5175) Study Team Psychosocial predictors of non-adherence and treatment failure in a large scale multi-national trial of antiretroviral therapy for HIV: Data from the ACTG A5175/PEARLS trial. PLoS One. 2014;9:e104178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Safren SA, Mayer KH, Ou SS, et al. ; HPTN 052 Study Team Adherence to early antiretroviral therapy: Results from HPTN 052, a phase III, multinational randomized trial of ART to prevent HIV-1 sexual transmission in serodiscordant couples. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69:234–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Pedhazur E, Kerlinger F.. Multiple Regression in Behavioral Research. 2nd ed. San Diego, CA: Harcourt College Publishers; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wuensch K. An Introduction to Path Analysis 2016. Available at http://core.ecu.edu/psyc/wuenschk/MV/SEM/Path.pdf. Accessibility verified January 2, 2019.

- 60. Sawyer A, Ayers S, Smith H. Pre- and postnatal psychological wellbeing in Africa: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2010;123:17–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hirschfeld RM, Montgomery SA, Keller MB, et al. Social functioning in depression: A review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:268–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mepham S, Zondi Z, Mbuyazi A, Mkhwanazi N, Newell ML. Challenges in PMTCT antiretroviral adherence in northern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2011;23:741–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kitshoff C, Campbell L, Naidoo SS. The association between depression and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-positive patients, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. South Afr Fam Pract. 2012;54(2):145–150. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Peltzer K, Friend-du Preez N, Ramlagan S, Anderson J. Antiretroviral treatment adherence among HIV patients in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Freeman M, Nkomo N, Kafaar Z, Kelly K. Mental disorder in people living with HIV/Aids in South Africa. South Afr J Psychol. 2008;38(3):489–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Myer L, Smit J, Roux LL, Parker S, Stein DJ, Seedat S. Common mental disorders among HIV-infected individuals in South Africa: Prevalence, predictors, and validation of brief psychiatric rating scales. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22:147–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Weiss SM, Peltzer K, Villar-Loubet O, Shikwane ME, Cook R, Jones DL. Improving PMTCT uptake in rural South Africa. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2014;13:269–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Jones D, Peltzer K, Weiss SM, et al. Implementing comprehensive prevention of mother-to-child transmission and HIV prevention for South African couples: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15:417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Farquhar C, Kiarie JN, Richardson BA, et al. Antenatal couple counseling increases uptake of interventions to prevent HIV-1 transmission. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37:1620–1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Dunlap J, Foderingham N, Bussell S, Wester CW, Audet CM, Aliyu MH. Male involvement for the prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission: A brief review of initiatives in East, West, and Central Africa. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2014;11:109–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Jones DL, Peltzer K, Villar-Loubet O, et al. Reducing the risk of HIV infection during pregnancy among South African women: A randomized controlled trial. AIDS Care. 2013;25:702–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Audet CM, Blevins M, Chire YM, et al. Engagement of men in antenatal care services: Increased HIV testing and treatment uptake in a community participatory action program in Mozambique. AIDS Behav. 2016;20:2090–2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kanyuuru L, Kabue M, Ashengo TA, Ruparelia C, Mokaya E, Malonza I. RED for PMTCT: An adaptation of immunization’s Reaching Every District approach increases coverage, access, and utilization of PMTCT care in Bondo District, Kenya. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;130(suppl 2):S68–S73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Seth P, Kidder D, Pals S, et al. Psychosocial functioning and depressive symptoms among HIV-positive persons receiving care and treatment in Kenya, Namibia, and Tanzania. Prev Sci. 2014;15:318–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Brittain K, Mellins CA, Phillips T, et al. Social support, stigma and antenatal depression among HIV-infected pregnant women in South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(1):274–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Alder J, Fink N, Bitzer J, Hösli I, Holzgreve W. Depression and anxiety during pregnancy: A risk factor for obstetric, fetal and neonatal outcome? A critical review of the literature. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007;20:189–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Cooper PJ, Tomlinson M, Swartz L, Woolgar M, Murray L, Molteno C. Post-partum depression and the mother-infant relationship in a South African peri-urban settlement. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175:554–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Patel V, Rahman A, Jacob KS, Hughes M. Effect of maternal mental health on infant growth in low income countries: New evidence from South Asia. BMJ. 2004;328:820–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Rahman A, Harrington R, Bunn J. Can maternal depression increase infant risk of illness and growth impairment in developing countries? Child Care Health Dev. 2002;28:51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Rahman A, Iqbal Z, Harrington R. Life events, social support and depression in childbirth: Perspectives from a rural community in the developing world. Psychol Med. 2003;33:1161–1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]