Abstract

Thrombin is a trypsin-like serine protease with multiple physiological functions. Its role in coagulation and thrombosis is well-established. Nevertheless, thrombin also plays a major role in inflammation by activating protease-activated receptors. In addition, thrombin is also involved in angiogenesis, fibrosis, and viral infections. Considering the pathogenesis of COVID-19 pandemic, thrombin inhibitors may exert multiple potential therapeutic benefits including antithrombotic, anti-inflammatory, and antiviral activities. In this review, we describe the clinical features of COVID-19, the thrombin’s roles in various pathologies, and the potential of argatroban in COVID-19 patients. Argatroban is a synthetic, small molecule, direct, competitive, and selective inhibitor of thrombin. It is approved to parenterally prevent and/or treat heparin-induced thrombocytopenia in addition to other thrombotic conditions. Argatroban also possesses anti-inflammatory and antiviral activities and has a well-established pharmacokinetics profile. It also appears to lack a significant risk of drug–drug interactions with therapeutics currently being evaluated for COVID-19. Thus, argatroban presents a substantial promise in treating severe cases of COVID-19; however, this promise is yet to be established in randomized, controlled clinical trials.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Argatroban, Coagulopathy, Inflammation

Introduction

Coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) continues to evolve as a deadly pandemic with more than 25 million people infected worldwide and more than 840 thousand individuals died because of the disease and/or its associated complications [1]. COVID-19 is a viral infection caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). The pathogen is a single-stranded RNA virus which, upon infecting the respiratory system, can cause pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome. The most common symptoms at the illness onset appear to be fever, cough, fatigue, and myalgia [2, 3]. Nevertheless, the disease is also associated with several extra-pulmonary manifestations. Gastrointestinal symptoms appear to be common and reported in about 40% of patients in some studies [4, 5]. Neurological manifestations such as headache, dizziness, and altered consciousness have also been reported [6]. Some COVID-19 patients also reported skin and ocular symptoms [7, 8] as well as taste or olfactory disorders [9].

Although the initial clinical cases from China involved hospitalized patients with severe pneumonia, yet overall data have suggested that ~ 80% of COVID-19 patients only experience a mild disease [10]. Many reports indicated that patients who require hospital admission initially appear stable, but they rapidly deteriorate with severe hypoxia leading to severe acute distress syndrome which requires ICU admission and mechanical ventilation [2, 11]. Myocardial injury also appears to be high among these patients [12]. The progression of illness in hospitalized patients has been attributed to excessive systemic inflammatory response including the excessive release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which may eventually lead to multiorgan failure and death. Along these lines, the progression of COVID-19 has been found to be associated with a decrease in lymphocytes and an increase in neutrophils. A number of inflammatory markers are reported to significantly increase during the severe stage of the illness including C-reactive protein, ferritin, interleukin-6 (IL-6), interferon gamma-induced protein-10 (IP-10), granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α), and tissue necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) [2, 13–15].

Furthermore, several cardiovascular, hematologic, and thrombotic complications have also been attributed to the (in)direct effects of the viral disease [16–18]. Several studies reported thrombotic complications in COVID-19 patients with rates of venous thromboembolic events as high as 30%, particularly in critically ill and mechanically ventilated patients [19–21]. Cardiovascular and thrombotic complications include intravascular disseminated coagulopathy, pulmonary embolism, stroke, acute limb ischemia, and acute coronary syndromes [22–26]. In fact, the hypercoagulable state of these patients was reflected by the elevated measured levels of D-dimer and fibrinogen as well as the prolonged measured prothrombin time [27]. Similar to the systemic inflammation, the hypercoagulable state appears to be associated with poor clinical outcomes [22–26].

Unfortunately, there are currently neither approved vaccines to protect people against the infection nor highly effective approved therapeutics to treat it. However, the evolving understanding of the virus life cycle and the infection pathogenicity is catalyzing the development of the urgently needed vaccines and therapeutics. In this direction, several viral and host proteins are being considered as drug targets to develop anti-COVID-19 therapeutics. In this review, we put forward thrombin, a trypsin-like serine protease belonging to the coagulation process, as a potential drug target to develop adjunct therapeutics for COVID-19, particularly for the critically ill patients. While the pivotal role of thrombin in coagulation and thrombosis is well established, thrombin also has a documented role in inflammation as well as a significant link to viral infections.

Thrombin in Coagulation, Inflammation, Angiogenesis, Fibrosis, and Viral Infections

Coagulation

Thrombin, also known as factor IIa, is a ~ 36 kD globular, trypsin-like serine protease in the common coagulation pathway. Thrombin is a pivotal protein in both hemostasis and thrombosis. Thrombin initiates the formation of fibrin clots and promotes platelet activation. It is enzymatically generated from its precursor i.e., prothrombin by the action of factor Xa of prothrombinase complex, which also includes phospholipids, calcium, and factor Va. Physiologically, thrombin converts fibrinogen to fibrin which ultimately leads to the formation of blood clot. Thrombin also activates factor XIII which subsequently cross-links fibrin so as to strengthen the formed clot. Thrombin also contributes to the propagation of the coagulation process by providing a positive feedback in which it activates other factors including factors V, VIII, and XI [28–33]. Thrombin can also activate platelets by binding to platelet glycoprotein Ibα [34] and/or protease-activated receptors (PARs) [35]. Thrombin is also reported to activate thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor and eventually downregulates fibrinolysis [36]. Together, thrombin is a key procoagulant protein and its excessive generation often leads to arterial or venous thrombosis. Under certain conditions, thrombin can exhibit an anticoagulant role by forming a complex with thrombomodulin. The resulting complex activates protein C which in turn cleaves factors Va and VIIIa resulting in a feedback inhibition of the coagulation process [37].

Inflammation, Angiogenesis, and Fibrosis

Beyond coagulation, thrombin’s pro-inflammatory effects are also well documented. Thrombin can initiate and amplify inflammation by activating PARs. PARs are G protein-coupled receptors that are expressed in a variety of tissues and cells including platelets, endothelial cells, leukocytes, and fibroblasts. These receptors can be activated by tissue factor: factor VIIa complex, factor Xa, and/or thrombin. Particularly, PARs (1, 3, and 4) modulate a variety of responses to thrombin including thrombosis and inflammation [38–40].

Thrombin was shown to upregulate the expression of cytokines, chemokines, and other proteins in different types of cells. In human adipocytes, thrombin stimulated the secretion of interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, MCP-1, and vascular endothelial cell growth factor [41]. Likewise, thrombin increased the release of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in urothelial cell, which can mediate bladder inflammation [42]. On endothelial cells, thrombin initiated the production of a number of pro-inflammatory mediators including IL-6, IL-8, transforming growth factor-β, MCP-1, platelet-derived growth factor, intracellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1, and P-selectin, mainly through the NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells) pathway. Disrupting this pathway was shown to inhibit the ability of thrombin to induce the expression of adhesion molecules including ICAM-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule and to reduce the thrombin-dependent adhesion of monocytes to endothelial cells [43–45]. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor secretion and ERK phosphorylation were implicated in thrombin effect on endothelium’s NF-κB activation [46]. At high concentrations, thrombin also increased endothelial permeability which is a feature of inflammation [47]. Thrombin has also been shown to induce the expression of IL-6 and C-X-C motif chemokine ligand-8 (aka IL-8) from human aortic smooth muscle cells [48]. With monocytes or monocyte-derived macrophages, thrombin enhanced adhesiveness, increased the production of IL-1, TNF-α, IL-6, MCP-1, and IL-10, and downregulated IL-12 secretion [49, 50]. Earlier, it was also shown that thrombin enhanced IL-1 and TNF-α induced polymorphonuclear leukocyte migration [51]. Likewise, thrombin enhanced the production of MCP-1 and macrophage inflammatory protein-2 in cultured rat glomerular epithelial cells [52]. Along these lines, thrombin inhibition was found to reduce the expression of brain inflammatory markers upon systemic lipopolysaccharide treatment of mice. In this model, inhibition of thrombin activity by a specific inhibitor reported as NAPAP (mostly likely is dabigatran) immediately led to a reduction in the expression of inflammatory markers of TNF-α, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand-9 (CXL9), and C-C motif chemokine ligand-1 (CCL1) and in the expression of the coagulation markers of factor X and PAR-1 in the brain [53].

Furthermore, thrombin can also directly activate the complement components C3 and C5 [54, 55] as well as modulate innate immune responses by altering cytokine secretion and receptor expression by antigen-presenting cells [56]. Thrombin was also found to promote angiogenesis and to increase the expression of angiogenic growth factors including fibroblast growth factor-2, platelet-derived growth factor, and vascular endothelial growth factor in human adipose cells and these effects were prevented by lepirudin, a direct thrombin inhibitor [41]. Thrombin-mediated regulation of platelet-derived growth factor influenced the migration and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells leading to plaque formation [57]. Thrombin was also shown to regulate the expression and release of platelet-derived growth factor activity from cultured renal microvascular endothelial cells, and thus, was proposed to in vivo stimulate mitogen to induce perivascular cell proliferation [58]. Subsequently, thrombin was shown to regulate the expression of proangiogenic cytokines by activating PAR-1 [59].

Importantly, thrombin was also shown to be involved in several experimental animal models of diseases including lipopolysaccharide-induced endotoxemia [39], glomerulonephritis [60], and lung fibrosis [61]. In the lung, thrombin mediated the expression of mucin and stimulated the expression of tissue factor from nasal epithelial cells through PAR-1 activation [62]. Recently, a study also showed that thrombin activates IL-1α, a pro-inflammatory cytokine that mediates innate immune responses and thrombopoiesis, following ectoderm injury in mice. Interestingly, thrombin-cleaved IL-1α was identified in humans with sepsis-associated adult respiratory distress syndrome suggesting a strong link between thrombin and inflammation [63]. Furthermore, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis produced in a vascular leak–dependent mouse model was found to be highly dependent on thrombin activity and its downstream signaling pathways. Inhibition of thrombin by dabigatran, and not by warfarin, significantly inhibited PAR-1 activation, integrin αvβ6 induction, transforming growth factor-β activation, and the development of pulmonary fibrosis in this model [64].

Viral Infections

Considering microbial infections, thrombin has been reported to be involved in the pathogenesis of several viruses by different mechanisms [65–75]. These viruses include hepatitis E virus [66], respiratory syncytial virus [67], human metapneumovirus [67, 71], influenza viruses [65, 72–74], coxsackievirus B3 [65], herpes simplex virus [68], cytomegalovirus [69], human immunodeficiency virus [70], and porcine circovirus-1 [75]. For example, thrombin has been implicated in the replication of hepatitis E virus, nonenveloped positive-sense and single-stranded RNA virus, by facilitating pORF1 polyprotein processing [66]. Data also showed that herpes simplex viruses-1 and -2 initiate thrombin production to increase the susceptibility of cells to infection through a mechanism involving PAR1-mediated cell modulation [68]. Thrombin was also found to increase influenza virus-induced inflammation. In fact, influenza viruses could induce thrombin generation leading to platelet activation-mediated lung inflammation [72–74]. Studies also linked thrombin to human metapneumovirus and respiratory syncytial virus, two enveloped, negative-sense, and single-stranded RNA viruses that cause respiratory infections. In these studies, thrombin was shown to increase the replication of these viruses and to exacerbate the associated inflammation [67, 71].

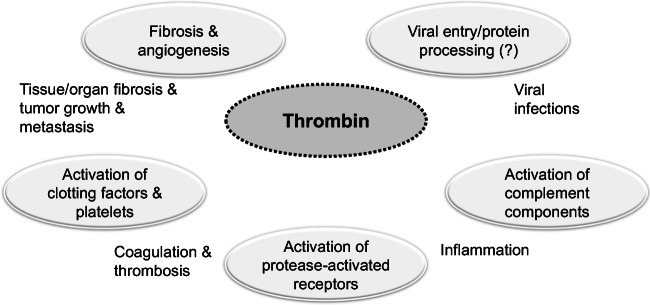

Together, considering thrombin’s roles in thrombosis, inflammation, and viral infections (Fig. 1), it is plausible to expect that inhibiting thrombin activity may eventually promote not only anticoagulant effect, but also anti-inflammatory and antiviral effects. These effects provide a strong rationale for the use of thrombin inhibitors in treating COVID-19 patients.

Fig. 1.

Thrombin plays a pivotal role in thrombosis, inflammation, angiogenesis, fibrosis, and viral infection. Therefore, thrombin inhibitors may eventually promote not only anticoagulant effect, but also anti-inflammatory and antiviral effects. Thrombin’s effect on protein C pathway is not presented

Current Thrombin Inhibitors

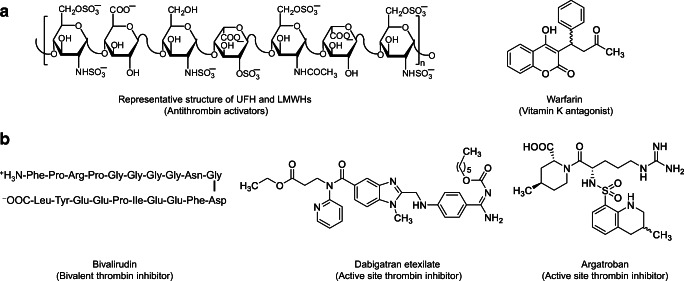

Current drugs that inhibit thrombin are classified into direct and indirect inhibitors (Fig. 2). In one hand, the indirect inhibitors include unfractionated heparin (UFH) and low molecular weight heparins (LMWHs) which activate the endogenous serpin antithrombin to eventually inhibit thrombin in a template- or bridging-based mechanism. UFH and LMWHs also antithrombin-dependently inhibit factor Xa [76, 77]. Warfarin, a vitamin K antagonist, also affects thrombin indirectly by inhibiting the hepatic biosynthesis of its precursor prothrombin by targeting vitamin K epoxide reductase and vitamin K quinone reductase [77]. In the other hand, hirudin, dabigatran etexilate, and argatroban are direct inhibitors of thrombin. Hirudin is a naturally occurring polypeptide isolated from the salivary glands of blood-sucking leeches of Hirudo medicinalis and possesses a blood anticoagulant property. Hirudin inhibits thrombin by binding to its active site as well as its allosteric exosite I, and thus, it is described as a bivalent inhibitor. Hirudin-related drugs that are in clinical use are lepirudin, desirudin, and bivalirudin [77, 78]. Dabigatran and argatroban are small molecule, active site, and selective inhibitors of thrombin [78].

Fig. 2.

The chemical structures of a indirect inhibitors (UFH, LMWHs, and warfarin) and b direct inhibitors of thrombin (bivalirudin, dabigatran etexilate, and argatroban). UFH, LMWHs, bivalirudin, and argatroban are parenterally used anticoagulants, whereas warfarin and dabigatran etexilate are orally used anticoagulants. Argatroban is the focus of this review

Generally, all the above drugs are approved for clinical use as prophylaxis or treatment of thrombotic conditions. Some of them are used parenterally while the others are orally active. UFH and LMWHs are heterogenous mixtures of sulfated glycosaminoglycans that are clinically used via the parenteral route of administration [79]. Lepirudin and desirudin are recombinant hirudins that were developed by recombinant technology in Saccharomyces cerevisiae [80]. Bivalirudin is an engineered 20-amino acid, synthetic analogue of hirudin [81]. All hirudin derivatives are also used parenterally. Argatroban is a synthetic tetrahydroquinolinyl-sulfonyl-L-arginyl-piperidine-carboxylic acid derivative that is also used parenterally. Warfarin is orally active coumarin derivative, whereas dabigatran etexilate is orally active, double prodrug that is derivative of benzimidazole methylamine-benzamidine [77–80].

In the ongoing pandemic, UFH and LMWHs appear to be gaining a momentum in treating COVID-19 [82, 83]. They are widely available and affordable anticoagulants with well-known pharmacological profiles and approved antidote to address potential bleeding events. However, a recent study has documented evidence of heparin resistance in critically ill COVID-19 patients [84]. In many cases, heparin resistance can be attributed to antithrombin deficiency. In fact, another recent study reported that antithrombin values were moderately, yet significantly lower in COVID-19 patients compared with control group [85]. Thus, this review focuses on argatroban which may serve as a potential alternative anticoagulant in COVID-19 patients. In fact, argatroban demonstrates anti-inflammatory and antiviral activities, in addition to its established anticoagulant properties. Argatroban is also associated with a favorable drug–drug interaction profile considering treatments currently under evaluation in COVID-19 patients [86].

Potential Therapeutic Benefits of Argatroban in COVID-19 Patients

Argatroban is a synthetic small molecule and peptidomimetic inhibitor of thrombin with a Ki value of ~ 39 nM. It is a reversible, parenterally used, highly selective, and competitive inhibitor of thrombin. In contrast to heparins, it directly inhibits the physiological function of the free as well as the clot-bound thrombin without the need for antithrombin. It inhibits fibrin formation as well as the thrombin-mediated activation of coagulation factors V, VIII, and XIII. It also inhibits the activation of protein C and platelet aggregation [79, 87]. Argatroban was first approved by the US FDA in 2000 as a prophylaxis or a treatment of thrombosis in adults with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. It is also used as an anticoagulant for percutaneous coronary intervention in adults who have or are at risk of developing heparin-induced thrombocytopenia [79, 87]. Similar indications are approved by the Canadian authorities. However, argatroban has been approved for other thrombotic conditions in Japan and Korea. It was first clinically used in Japan for the treatment of peripheral arterial occlusive disease in the early 1980s. It was then approved for the treatment of arterial thrombosis, acute cerebral thrombosis, and anticoagulation of antithrombin-deficient patients undergoing hemodialysis. Argatroban is also approved in Korea for use in chronic arterial occlusion and acute cerebral thrombosis [88]. Given the high risk of coagulopathy in severe and critically ill COVID-19 patients, the anticoagulant activity of argatroban is of enormous benefit, particularly that anticoagulation has been found to increase survival in these patients [89, 90].

Given the established role of thrombin in inflammation, angiogenesis, and fibrosis, thrombin inhibitors are likely to protect against these pathologies. As mentioned before, lepirudin was found to prevent thrombin-mediated angiogenesis and to prevent thrombin-mediated expression of angiogenic growth factors [41]. Dabigatran reduced the expression of inflammatory markers of TNF-α, CXL9, and CCL1 and the expression of the coagulation markers of factor X and PAR-1 in mouse brain [53]. Dabigatran significantly inhibited PAR-1 activation, integrin αvβ6 induction, transforming growth factor-β activation, and the development of pulmonary fibrosis in a vascular-leak mouse model [64]. Similar to lepirudin [41] and dabigatran [53, 64], argatroban is likely to protect against these pathologies. Furthermore, continuous infusion of argatroban was also found to increase the plasma levels of nitric oxide and nitrosyl hemoglobin in patients with peripheral arterial obstructive disease, and thus, to improve microcirculation compared with a placebo-treated group [91]. Moreover, plasma samples collected from heparin-induced thrombocytopenia patients indicated that treatment with argatroban significantly decreased the circulatory levels of inflammation markers including myeloperoxidase, CD40L, and functional microparticles. Nitric oxide levels measured in platelets were also increased with argatroban treatment [92]. Interestingly, none of the above effects was observed with lepirudin or bivalirudin [92], suggesting a greater potential benefit of argatroban.

In a diabetic cardiomyopathy rat model, argatroban treatment reduced plasma levels of glucose and cholesterol, alleviated ventricular dysfunctions by improving systolic and diastolic functions, decreased cardiac fibrosis, and reduced apoptosis. In this model, argatroban significantly reduced the expression of PAR-1 and PAR-4. Protein kinase B, glycogen synthase kinase-3β, p-65 NF-ĸB phosphorylation, transforming growth factor-β, cyclooxygenase-2, and caspase-3 expression were also reduced significantly in rats treated with argatroban, along with a substantial increase in sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium—ATPase expression suggesting a significant anti-fibrotic, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic potential of argatroban [93]. Argatroban also decreased the production of MCP-1 and macrophage inflammatory protein-2 in cultured rat glomerular epithelial cells [52]. Thrombin inhibition by argatroban also decreased neurodegeneration and cerebral edema following bilateral common carotid artery occlusion and reperfusion in male Mongolian gerbils [94].

Literature has also reported on the antiviral activity of argatroban. Human metapneumovirus, which belongs to the family of Pneumoviridae, is non-segmented, negative-stranded, enveloped RNA virus. It can cause upper and lower respiratory diseases particularly among young children, older adults, and people with compromised immune systems. In mice studies, it was found that immediate injections of argatroban after the virus challenge protected mice against human metapneumovirus infection and substantially reduced mortality, weight loss, viral load, and lung inflammation. In particular, the results showed that there was no weight loss or mortality in the infected mice that received immediate treatment with argatroban post-infection followed by 4 days of treatment. A significant decrease in lung viral titers was detected on day 5 post-infection. Argatroban also significantly reduced thrombin generation and leukocyte recruitment during the infection. It also induced significant decreases in the levels of G-CSF, interferon-γ, IL-3, IL-4, IL-6, IL-12 p70, and MCP-1 in the bronchoalveolar lavage of the infected mice, as compared with controls. It also decreased the virus-induced lung tissue damage [71].

As far as COVID-19, argatroban was recently identified via bioinformatics approach as a potential blocker of angiotensin converting enzyme-2 (ACE2), yet the finding was not experimentally confirmed. ACE2 is the human cell receptor to which the viral spike S protein binds [95]. A homology modeling and virtual screening also identified argatroban as a potential inhibitor of the viral 3-chymotrypsin-like protease (also known as the main protease), a viral protease with an essential role in processing the polyproteins that are translated from the viral RNA [96]. Another computational work identified argatroban as a potential inhibitor of transmembrane protease, serine-2 (TMPRSS2), a serine protease that facilitates the viral fusion and entry into the host cell [97]. Importantly, although promising, the above computational results remain to be theoretical in nature.

Pharmacokinetics, Toxicities, and Potential Drug–Drug Interactions of Argatroban

Because argatroban is administered via IV infusion, it promotes an immediate action. It has a volume of distribution of 174 mL/kg and binds to plasma proteins including albumin (~ 20%) and α1-acid glycoprotein (~ 34%). Its plasma half-life is 39–51 min, which is extended to 181 min in patients with hepatic impairment. The time to reach steady state peak is 1–3 h. Its clearance rate in adults is about 5.1 mL/kg/min, which is decreased to 1.9 mL/kg/min in patients with hepatic impairment. The main route of argatroban metabolism is hydroxylation and aromatization of the tetrahydro-quinoline ring in the liver. The formation of metabolites is catalyzed in vitro by CYP450 3A4/5. Thus, the dosage of argatroban should be decreased in patients with hepatic impairment. Argatroban is excreted primarily in the feces, and thus, no dosage adjustment is necessary in patients with renal dysfunction [78, 88, 98–100].

Argatroban was not genotoxic in a host of tests. Argatroban also had no effect on fertility or reproductive function of male and female rats at IV doses up to 27 mg/kg/day [78, 88, 98–100]. Argatroban’s adverse reactions are generally mild and appear to resolve upon treatment discontinuation. In heparin-induced thrombocytopenia patients, the most common adverse reactions were dyspnea, hypotension, fever, and diarrhea. In percutaneous coronary intervention patients, the most common adverse reactions were chest pain, hypotension, back pain, nausea, vomiting, and headache [98]. As with all anticoagulants, bleeding is also a potential adverse effect of argatroban. There is no specific antidote for argatroban. Given its short-half life, management of bleeding is recommended via the cessation of treatment and general hemostatic measures [100].

Considering drug–drug interactions, the concomitant use of argatroban and warfarin was found to lead to prothrombin time prolongation. If argatroban is to be initiated after cessation of heparin therapy, sufficient time should be allowed prior to initiation of argatroban therapy. No drug–drug interactions have been demonstrated between argatroban and concomitantly administered aspirin, acetaminophen, digoxin, or azithromycin. The safety and effectiveness of argatroban with thrombolytic agents do not appear to have been established [98]. Interestingly, there appear no potential interactions between argatroban and drugs being currently tested for COVID-19 including lopinavir/ritonavir, remdesivir, ribavirin, hydroxychloroquine, tocilizumab, sarilumab, methylprednisolone, and anakinra [86].

Conclusion

The potential therapeutic benefits of argatroban as a treatment for COVID-19 infection and/or its complications can be attributed to its antithrombotic, anti-inflammatory, and antiviral properties. These properties have been supported by a large number of studies in cellular settings, animal models, and humans. Owing to these properties, argatroban could potentially assist in treating the coagulopathy, dampen the excessive inflammation, and halting the viral replication, particularly in severe and critically ill COVID-19 patients. Encouraging aspects also include the worldwide availability of the drug, its well-established pharmacokinetics and safety profiles, and the apparent lack of drug–drug interactions with potential anti-COVID-19 therapeutics under evaluation. In this direction, successful anticoagulation with argatroban was very recently reported in a small number of severely ill COVID-19 patients (N = 10) with acute antithrombin deficiency [101]. Nevertheless, the potential benefits of argatroban in COVID-19 patients remain largely hypothetical and will have to be clinically established via large, randomized, double-blinded, and controlled clinical trials. Currently, argatroban is being studied in a phase 4 trial of anticoagulation in critically ill patients with COVID-19 (NCT04406389).

Acknowledgments

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH.

Authors’ Contribution

RAAH: conceptualized the project; RAAH and KFA: reviewed the relevant literature; KFA: wrote the first draft; RAAH: supervised, revised, and finalized the manuscript; RAAH: provided all resources; RAAH: visualized the project aspect.

Funding

RAAH is supported by NIGMS/NIH under award number SC3GM131986 and by IDeA program from NIGMS/NIH under grant number P20GM103424.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Kholoud F. Aliter, Email: kal-horani@dillard.edu

Rami A. Al-Horani, Email: ralhoran@xula.edu

References

- 1.Dong E, Du H, Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(5):533–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kluytmans-vanden Bergh MFQ, Buiting AGM, Pas SD, et al. Prevalence and clinical presentation of health care workers with symptoms of coronavirus disease 2019 in 2 Dutch hospitals during an early phase of the pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(5):e209673 https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2766228. Accessed 25 Aug 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Liang W, Feng Z, Rao S, Xiao C, Xue X, Lin Z, Zhang Q, Qi W. Diarrhoea may be underestimated: a missing link in 2019 novel coronavirus. Gut. 2020;69(6):1141–1143. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang JJ, Dong X, Cao YY, Yuan YD, Yang YB, Yan YQ, Akdis CA, Gao YD. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China. Allergy. 2020;75(7):1730–1741. doi: 10.1111/all.14238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, Hu Y, Chen S, He Q, Chang J, Hong C, Zhou Y, Wang D, Miao X, Li Y, Hu B. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(6):1–9. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(5):e212–e213. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu P, Duan F, Luo C, Liu Q, Qu X, Liang L, Wu K. Characteristics of ocular findings of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020;138(5):575–578. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giacomelli A, Pezzati L, Conti F, Bernacchia D, Siano M, Oreni L, Rusconi S, Gervasoni C, Ridolfo AL, Rizzardini G, Antinori S, Galli M. Self-reported olfactory and taste disorders in SARS-CoV-2 patients: a cross-sectional study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):889–890. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Epidemiology Working Group for NCIP Epidemic Response Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41(2):145–151. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2020.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, Wang B, Xiang H, Cheng Z, Xiong Y, Zhao Y, Li Y, Wang X, Peng Z. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng YY, Ma YT, Zhang JY, Xie X. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17(5):259–260. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0360-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qin C, Zhou L, Hu Z, Zhang S, Yang S, Tao Y, Xie C, Ma K, Shang K, Wang W, Tian DS. Dysregulation of immune response in patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):762–768. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng M, Gao Y, Wang G, Song G, Liu S, Sun D, Xu Y, Tian Z. Functional exhaustion of antiviral lymphocytes in COVID-19 patients. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17:533–535. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0402-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ, HLH Across Speciality Collaboration, UK COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Driggin E, Madhavan MV, Bikdeli B, Chuich T, Laracy J, Biondi-Zoccai G, Brown TS, der Nigoghossian C, Zidar DA, Haythe J, Brodie D, Beckman JA, Kirtane AJ, Stone GW, Krumholz HM, Parikh SA. Cardiovascular considerations for patients, health care workers, and health systems during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(18):2352–2371. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clerkin KJ, Fried JA, Raikhelkar J, Sayer G, Griffin JM, Masoumi A, Jain SS, Burkhoff D, Kumaraiah D, Rabbani LR, Schwartz A, Uriel N. COVID-19 and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2020;141(20):1648–1655. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bikdeli B, Madhavan MV, Jimenez D, Chuich T, Dreyfus I, Driggin E, Nigoghossian C, Ageno W, Madjid M, Guo Y, Tang LV, Hu Y, Giri J, Cushman M, Quéré I, Dimakakos EP, Gibson CM, Lippi G, Favaloro EJ, Fareed J, Caprini JA, Tafur AJ, Burton JR, Francese DP, Wang EY, Falanga A, McLintock C, Hunt BJ, Spyropoulos AC, Barnes GD, Eikelboom JW, Weinberg I, Schulman S, Carrier M, Piazza G, Beckman JA, Steg PG, Stone GW, Rosenkranz S, Goldhaber SZ, Parikh SA, Monreal M, Krumholz HM, Konstantinides SV, Weitz JI, Lip GYH, Global COVID-19 Thrombosis Collaborative Group, Endorsed by the ISTH, NATF, ESVM, and the IUA, Supported by the ESC Working Group on Pulmonary Circulation and Right Ventricular Function COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(23):2950–2973. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cui S, Chen S, Li X, Liu S, Wang F. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(6):1421–1424. doi: 10.1111/jth.14830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, Arbous MS, Gommers DAMPJ, Kant KM, Kaptein FHJ, van Paassen J, Stals MAM, Huisman MV, Endeman H. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Helms J, Tacquard C, Severac F, et al. High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(6):1089–1098. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06062-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oxley TJ, Mocco J, Majidi S, Kellner CP, Shoirah H, Singh IP, de Leacy RA, Shigematsu T, Ladner TR, Yaeger KA, Skliut M, Weinberger J, Dangayach NS, Bederson JB, Tuhrim S, Fifi JT. Large-vessel stroke as a presenting feature of Covid-19 in the young. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):e60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bangalore S, Sharma A, Slotwiner A, Yatskar L, Harari R, Shah B, Ibrahim H, Friedman GH, Thompson C, Alviar CL, Chadow HL, Fishman GI, Reynolds HR, Keller N, Hochman JS. ST-segment elevation in patients with Covid-19-a case series. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(25):2478–2480. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bellosta R, Luzzani L, Natalini G, et al. Acute limb ischemia in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. J Vasc Surg. 2020;S0741-5214(20):31080–6 https://www.jvascsurg.org/article/S0741-5214(20)31080-6/fulltext. Accessed 10 June 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Bompard F, Monnier H, Saab I, et al. Pulmonary embolism in patients with Covid-19 pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2020;2001365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Tang N, Li D, Wang X, Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(4):844–847. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Demelo-Rodríguez P, Cervilla-Muñoz E, Ordieres-Ortega L, Parra-Virto A, Toledano-Macías M, Toledo-Samaniego N, García-García A, García-Fernández-Bravo I, Ji Z, de-Miguel-Diez J, Álvarez-Sala-Walther LA, del-Toro-Cervera J, Galeano-Valle F. Incidence of asymptomatic deep vein thrombosis in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia and elevated D-dimer levels. Thromb Res. 2020;192:23–26. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Green D. Coagulation cascade. Hemodial Int. 2006;10(Suppl 2):S2–S4. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2006.00119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davie EW, Fujikawa K, Kisiel W. The coagulation cascade: initiation, maintenance, and regulation. Biochemistry. 1991;30:10363–10370. doi: 10.1021/bi00107a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laki K, Gladner JA. Chemistry and physiology of the fibrinogen-fibrin transition. Physiol Rev. 1964;44:127–160. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1964.44.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Versteeg HH, Heemskerk JW, Levi M, et al. New fundamentals in hemostasis. Physiol Rev. 2013;93:327–358. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00016.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.von dem Borne PA, Meijers JC, Bouma BN. Feedback activation of factor XI by thrombin in plasma results in additional formation of thrombin that protects fibrin clots from fibrinolysis. Blood. 1995;86:3035–3042. doi: 10.1182/blood.V86.8.3035.3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al-Horani RA, Kar S. Factor XIIIa inhibitors as potential novel drugs for venous thromboembolism. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;200:112442. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruggeri ZM, Zarpellon A, Roberts JR, Mc Clintock RA, Jing H, Mendolicchio GL. Unravelling the mechanism and significance of thrombin binding to platelet glycoprotein Ib. Thromb Haemost. 2010;104(5):894–902. doi: 10.1160/TH10-09-0578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sambrano GR, Weiss EJ, Zheng YW, Huang W, Coughlin SR. Role of thrombin signalling in platelets in haemostasis and thrombosis. Nature. 2001;413(6851):74–78. doi: 10.1038/35092573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bouma BN, Mosnier LO. Thrombin activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor (TAFI)--how does thrombin regulate fibrinolysis? Ann Med. 2006;38(6):378–388. doi: 10.1080/07853890600852898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Esmon CT. The roles of protein C and thrombomodulin in the regulation of blood coagulation. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:4743–4746. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)83649-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen D, Dorling A. Critical roles for thrombin in acute and chronic inflammation. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7(Suppl 1):122–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ma L, Dorling A. The roles of thrombin and protease-activated receptors in inflammation. Semin Immunopathol. 2012;34(1):63–72. doi: 10.1007/s00281-011-0281-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Popović M, Smiljanić K, Dobutović B, Syrovets T, Simmet T, Isenović ER. Thrombin and vascular inflammation. Mol Cell Biochem. 2012;359(1–2):301–313. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-1024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Strande JL, Phillips SA. Thrombin increases inflammatory cytokine and angiogenic growth factor secretion in human adipose cells in vitro. J Inflamm (Lond) 2009;6:4. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-6-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vera PL, Wolfe TE, Braley AE, Meyer-Siegler KL. Thrombin induces macrophage migration inhibitory factor release and upregulation in urothelium: a possible contribution to bladder inflammation. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15904. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Minami T, Sugiyama A, Wu SQ, Abid R, Kodama T, Aird WC. Thrombin and phenotypic modulation of the endothelium. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:41–53. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000099880.09014.7D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rahman A, Fazal F. Hug tightly and say goodbye: role of endothelial ICAM-1 in leukocyte transmigration. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:823–839. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miho N, Ishida T, Kuwaba N, et al. Role of the JNK pathway in thrombin-induced ICAM-1 expression in endothelial cells. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;68(2):289–298. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wadgaonkar R, Somnay K, Garcia JG. Thrombin induced secretion of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) and its effect on nuclear signaling in endothelium. J Cell Biochem. 2008;105(5):1279–1288. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feistritzer C, Riewald M. Endothelial barrier protection by activated protein C through PAR1-dependent sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor-1 crossactivation. Blood. 2005;105(8):3178–3184. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chung SW, Park JW, Lee SA, Eo SK, Kim K. Thrombin promotes proinflammatory phenotype in human vascular smooth muscle cell. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;396:748–754. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kastl SP, Speidl WS, Katsaros KM, Kaun C, Rega G, Assadian A, Hagmueller GW, Hoeth M, de Martin R, Ma Y, Maurer G, Huber K, Wojta J. Thrombin induces the expression of oncostatin M via AP-1 activation in human macrophages: a link between coagulation and inflammation. Blood. 2009;114:2812–2818. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-200915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Colotta F, Sciacca FL, Sironi M, Luini W, Rabiet MJ, Mantovani A. Expression of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 by monocytes and endothelial cells exposed to thrombin. Am J Pathol. 1994;144(5):975–985. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Drake WT, Lopes NN, Fenton JW, 2nd, Issekutz AC. Thrombin enhancement of interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha induced polymorphonuclear leukocyte migration. Lab Investig. 1992;67(5):617–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fujita T, Yamabe H, Shimada M, Murakami R, Kumasaka R, Nakamura N, Osawa H, Okumura K. Thrombin enhances the production of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and macrophage inflammatory protein-2 in cultured rat glomerular epithelial cells. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(11):3412–3417. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shavit Stein E, Ben Shimon M, Artan Furman A, Golderman V, Chapman J, Maggio N. Thrombin inhibition reduces the expression of brain inflammation markers upon systemic LPS treatment. Neural Plast. 2018;2018:7692182. doi: 10.1155/2018/7692182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huber-Lang M, Sarma JV, Zetoune FS, Rittirsch D, Neff TA, McGuire SR, Lambris JD, Warner RL, Flierl MA, Hoesel LM, Gebhard F, Younger JG, Drouin SM, Wetsel RA, Ward PA. Generation of C5a in the absence of C3: a new complement activation pathway. Nat Med. 2006;12(6):682–687. doi: 10.1038/nm1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clark A, Weymann A, Hartman E, Turmelle Y, Carroll M, Thurman JM, Holers VM, Hourcade DE, Rudnick DA. Evidence for non-traditional activation of complement factor C3 during murine liver regeneration. Mol Immunol. 2008;45(11):3125–3132. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Naldini A, Aarden L, Pucci A, Bernini C, Carraro F. Inhibition of interleukin-12 expression by alpha-thrombin in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells: a potential mechanism for modulating Th1/Th2 responses. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;140(5):980–986. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Noda-Heiny H, Sobel BE. Vascular smooth muscle cell migration mediated by thrombin and urokinase receptor. Am J Phys. 1995;268(5 Pt 1):C1195–C1201. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.5.C1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Daniel TO. Gibbs VC, Milfay DF, Garovoy MR, Williams LT. Thrombin stimulates c-sis gene expression in microvascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1986;261(21):9579–9582. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)67551-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Naldini A, Carney DH, Pucci A, Pasquali A, Carraro F. Thrombin regulates the expression of proangiogenic cytokines via proteolytic activation of protease-activated receptor-1. Gen Pharmacol. 2000;35(5):255–259. doi: 10.1016/S0306-3623(01)00113-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cunningham MA, Rondeau E, Chen X, Coughlin SR, Holdsworth SR, Tipping PG. Protease-activated receptor 1 mediates thrombin-dependent, cell-mediated renal inflammation in crescentic glomerulonephritis. J Exp Med. 2000;191:455–462. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Howell DC, Johns RH, Lasky JA, Shan B, Scotton CJ, Laurent GJ, et al. Absence of proteinase-activated receptor-1 signaling affords protection from bleomycin-induced lung inflammation and fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1353–1365. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62354-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shimizu S, Shimizu T, Morser J, Kobayashi T, Yamaguchi A, Qin L, Toda M, D’Alessandro-Gabazza C, Maruyama T, Takagi T, Yano Y, Sumida Y, Hayashi T, Takei Y, Taguchi O, Suzuki K, Gabazza EC. Role of the coagulation system in allergic inflammation in the upper airways. Clin Immunol. 2008;129:365–371. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Burzynski LC, Humphry M, Pyrillou K, et al. The coagulation and immune systems are directly linked through the activation of interleukin-1α by thrombin. Immunity. 2019;50(4):1033–1042.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Shea BS, Probst CK, Brazee PL, Rotile NJ, Blasi F, Weinreb PH, Black KE, Sosnovik DE, van Cott EM, Violette SM, Caravan P, Tager AM. Uncoupling of the profibrotic and hemostatic effects of thrombin in lung fibrosis. JCI Insight. 2017;2(9):e86608. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.86608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Antoniak S, Owens AP, Baunacke M, Williams JC, Lee RD, et al. PAR-1 contributes to the innate immune response during viral infection. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1310–1322. doi: 10.1172/JCI66125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kanade GD, Pingale KD, Karpe YA. Activities of thrombin and factor Xa are essential for replication of hepatitis E virus and are possibly implicated in ORF1 polyprotein processing. J Virol. 2018;92(6):e01853–e01817. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01853-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lê VB, Riteau B, Alessi MC, Couture C, Jandrot-Perrus M, Rhéaume C, Hamelin MÈ, Boivin G. Protease-activated receptor 1 inhibition protects mice against thrombin-dependent respiratory syncytial virus and human metapneumovirus infections. Br J Pharmacol. 2018;175(2):388–403. doi: 10.1111/bph.14084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sutherland MR, Friedman HM, Pryzdial EL. Thrombin enhances herpes simplex virus infection of cells involving protease-activated receptor 1. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:1055–1061. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Scholz M, Vogel JU, Höver G, Kotchetkov R, Cinatl J, et al. Thrombin stimulates IL-6 and IL-8 expression in cytomegalovirus-infected human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Int J Mol Med. 2004;13:327–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ling H, Xiao P, Usami O, Hattori T. Thrombin activates envelope glycoproteins of HIV type 1 and enhances fusion. Microbes Infect. 2004;6:414–420. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lê BV, Jandrot-Perrus M, Couture C, Checkmahomed L, Venable MC, Hamelin MÈ, Boivin G. Evaluation of anticoagulant agents for the treatment of human metapneumovirus infection in mice. J Gen Virol. 2018;99(10):1367–1380. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.001135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Le VB, Schneider JG, Boergeling Y, Berri F, Ducatez M, et al. Platelet activation and aggregation promote lung inflammation and influenza virus pathogenesis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:804–819. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201406-1031OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Boilard E, Pare G, Rousseau M, Cloutier N, Dubuc I, et al. Influenza virus H1N1 activates platelets through FcgRIIA signaling and thrombin generation. Blood. 2014;123:2854–2863. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-07-515536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Keller TT, van der Sluijs KF, de Kruif MD, Gerdes VEA, Meijers JCM, Florquin S, van der Poll T, van Gorp ECM, Brandjes DPM, Büller HR, Levi M. Effects on coagulation and fibrinolysis induced by influenza in mice with a reduced capacity to generate activated protein C and a deficiency in plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1. Circ Res. 2006;99(11):1261–1269. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000250834.29108.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Marks FS, Reck J, Jr, Almeida LL, Berger M, Corrêa AMR, Driemeier D, Barcellos DESN, Guimarães JA, Termignoni C, Canal CW. Porcine circovirus 2 (PCV2) induces a procoagulant state in naturally infected swine and in cultured endothelial cells. Vet Microbiol. 2010;141(1–2):22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gray E, Mulloy B, Barrowcliffe TW. Heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin. Thromb Haemost. 2008;99(5):807–818. doi: 10.1160/TH08-01-0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Harter K, Levine M, Henderson SO. Anticoagulation drug therapy: a review. West J Emerg Med. 2015;16(1):11–17. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2014.12.22933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lee CJ, Ansell JE. Direct thrombin inhibitors. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;72(4):581–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03916.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Garcia DA, Baglin TP, Weitz JI, Samama MM. Parenteral anticoagulants: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e24S–43S https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(12)60118-4/fulltext. Accessed 10 June 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 80.Alban S. Pharmacological strategies for inhibition of thrombin activity. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14(12):1152–1175. doi: 10.2174/138161208784246135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Steinmetzer T, Stürzebecher J. Von Fibrinogen und Hirudin zu synthetischen Antikoagulanzien. Rationales Design von Thrombinhemmstoffen [From fibrinogen and hirudin to synthetic anticoagulants. Rational design of thrombin inhibitors] Pharm Unserer Zeit. 2004;33(3):196–205. doi: 10.1002/pauz.200400068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lindahl U, Li JP. Heparin-an old drug with multiple potential targets in Covid-19 therapy. J Thromb Haemost. 2020:10.1111/jth.14898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 83.Belen-Apak FB, Sarialioglu F. The old but new: can unfractioned heparin and low molecular weight heparins inhibit proteolytic activation and cellular internalization of SARS-CoV2 by inhibition of host cell proteases? Med Hypotheses. 2020;142:109743. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.White D, MacDonald S, Bull T, Hayman M, de Monteverde-Robb R, Sapsford D, Lavinio A, Varley J, Johnston A, Besser M, Thomas W. Heparin resistance in COVID-19 patients in the intensive care unit. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;50(2):287–291. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02145-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Han H, Yang L, Liu R, Liu F, Wu KL, Li J, Liu XH, Zhu CL. Prominent changes in blood coagulation of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2020;58(7):1116–1120. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2020-0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bikdeli B, Madhavan MV, Gupta A, Jimenez D, Burton JR, der Nigoghossian C, Chuich T, Nouri SN, Dreyfus I, Driggin E, Sethi S, Sehgal K, Chatterjee S, Ageno W, Madjid M, Guo Y, Tang LV, Hu Y, Bertoletti L, Giri J, Cushman M, Quéré I, Dimakakos EP, Gibson CM, Lippi G, Favaloro EJ, Fareed J, Tafur AJ, Francese DP, Batra J, Falanga A, Clerkin KJ, Uriel N, Kirtane A, McLintock C, Hunt BJ, Spyropoulos AC, Barnes GD, Eikelboom JW, Weinberg I, Schulman S, Carrier M, Piazza G, Beckman JA, Leon MB, Stone GW, Rosenkranz S, Goldhaber SZ, Parikh SA, Monreal M, Krumholz HM, Konstantinides SV, Weitz JI, Lip GYH, The Global COVID-19 Thrombosis Collaborative Group Pharmacological agents targeting thrombo-inflammation in COVID-19: review and implications for future research. Thromb Haemost. 2020;120(7):1004–1024. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1713152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Linkins LA, Dans AL, Moores LK, Bona R, Davidson BL, Schulman S, et al. Treatment and prevention of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e495S–530S https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692(12)60130-5/fulltext. Accessed 10 June 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 88.Walenga JM. An overview of the direct thrombin inhibitor argatroban. Pathophysiol Haemost Thromb. 2002;32(Suppl 3):9–14. doi: 10.1159/000069103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tang N, Bai H, Chen X, Gong J, Li D, Sun Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(5):1094–1099. doi: 10.1111/jth.14817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Paranjpe I, Fuster V, Lala A, Russak AJ, Glicksberg BS, Levin MA, Charney AW, Narula J, Fayad ZA, Bagiella E, Zhao S, Nadkarni GN. Association of treatment dose anticoagulation with in-hospital survival among hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(1):122–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ueki Y, Matsumoto K, Kizaki Y, Yoshida K, Matsunaga Y, Yano M, Miyake S, Tominaga Y, Eguchi K. Argatroban increases nitric oxide levels in patients with peripheral arterial obstructive disease: placebo-controlled study. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 1999;8(2):131–137. doi: 10.1023/A:1008963118789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fareed J, Hoppensteadt D, Bansal V, Walenga J, Lale A, Bick R. The anti-inflammatory effects of argatroban can be differentiated from other direct thrombin inhibitors: experimental and clinical observations. Blood. 2006;108(11):4132. doi: 10.1182/blood.V108.11.4132.4132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bulani Y, Sharma SS. Argatroban attenuates diabetic cardiomyopathy in rats by reducing fibrosis, inflammation, apoptosis, and protease-activated receptor expression. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2017;31(3):255–267. doi: 10.1007/s10557-017-6732-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ohyama H, Hosomi N, Takahashi T, Mizushige K, Kohno M. Thrombin inhibition attenuates neurodegeneration and cerebral edema formation following transient forebrain ischemia. Brain Res. 2001;902(2):264–271. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(01)02354-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kim J, Zhang J, Cha Y, Kolitz S, Funt J, Escalante Chong R, et al. Advanced bioinformatics rapidly identifies existing therapeutics for patients with coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19). 2020;18(1):257 https://translational-medicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12967-020-02430-9. Accessed 25 Aug 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 96.Nguyen DD, Gao K, Chen J, Wang R, Wei GW. Potentially highly potent drugs for 2019-nCoV. Preprint. bioRxiv. 2020;2020.02.05.936013. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.02.05.936013v1. Accessed 10 June 2020.

- 97.Sheikh HK, Arshad T, Mohammad ZS, Arshad I, Hassan M. Repurposed single inhibitor for serine protease and spike glycoproteins of SAR-CoV-2. Preprint. chemRxiv. 2020. https://chemrxiv.org/articles/preprint/Repurposed_Single_Inhibitor_for_Serine_Protease_and_Spike_Glycoproteins_of_SAR-CoV-2/12192660/1. Accessed 10 June 2020.

- 98.The U.S. Food and Drug Administration. In: Argatroban label. ARGATROBAN INJECTION. 2011. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/022485lbl.pdf. Accessed on 7 June 2020.

- 99.Swan SK, Hursting MJ. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of argatroban: effects of age, gender, and hepatic or renal dysfunction. Pharmacotherapy. 2000;20(3):318–329. doi: 10.1592/phco.20.4.318.34881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Makris M, Van Veen JJ, Tait CR, Mumford AD, Laffan M, British Committee for Standards in Haematology Guideline on the management of bleeding in patients on antithrombotic agents. Br J Haematol. 2013;160(1):35–46. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Arachchillage DJ, Remmington C, Rosenberg A, et al. Anticoagulation with argatroban in patients with acute antithrombin deficiency in severe COVID-19. Br J Haematol. 2020:10.1111/bjh.16927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]