Abstract

This article reflects on insights from an action research project where we worked with students whose university experience was inhibited by the fear of failure. In contrast to the popular concept of ‘learning from failure’, which involves intellectualizing the experience and distancing ourselves from it, our findings demonstrate the importance of a ‘present tense’ focus on emotions and affects in order to understand the experience of failure for students. Doing so brings us face-to-face with the often painful experience of failure in the present moment which, we argue, is an important and valid part of the university experience. We conclude by reflecting on the kinds of spaces and skills that may be needed to work with this new understanding of failure and show that developing these is a crucial part of resisting neoliberalism and creating a more ‘care-full’ (Mountz et al., 2015) academy.

Keywords: Failure, University, Emotions, Affects, Slow scholarship, Neoliberalism

Highlights

-

•

Fear of failure is an intense affectual experience which many students encounter.

-

•

It is vital to engage with the lived experience of failure in the present tense.

-

•

Neoliberalism can be countered by creating new skills and spaces for working with failure.

1. Introduction

Neoliberalism's focus on individuals and competitiveness breeds constant self-comparison and leads to increasingly narrow definitions of success and failure (Berg et al., 2016; Halberstam, 2011). As a result, fear of failure is a powerful experience for students in contemporary higher education (HE). This paper uses what we call a ‘present tense’ focus on emotions and affects to explore the experience of failure for university students and consider how affectual engagement with failure can provide a form of resistance to neoliberalism. While emotions and affects are key dimensions of failure, our experience is that they are rarely discussed or worked with productively. Instead, there is a tendency to intellectualize failure and mistakes through what Mizrahi (1984) referred to in a medical education context as the ‘three Ds’ (denied, discounted and distanced). Our argument here is that there are four problems with failure in university culture:

-

1.

It is often not talked about at all (or is hidden behind euphemisms such as ‘messy’ (Harrowell et al., 2018).

If it is talked about, then:

-

2.

It tends to be talked about from a position of authority, power or security

-

3.

It is a constructed narrative with a ‘happy’ (or at least ‘resolved’) ending

-

4.

It is retrospective or seen at a distance

We can recognise 2, 3 and 4 in particular in the classic “I learnt from failure and it helped make me the success I am today” story. While there can be merit in ‘stepping back’ from failure, our research shows that analyses which do not engage with the present tense, lived experience of failure – which is deeply affectual and often deeply vulnerable – are in danger of misunderstanding what ‘failure’ really means. In short, our research shows that failure is felt differently, and is not always identifiable within its normative framings (Brown, 2002). Working with these feelings is important since we argue here that an emotional and affectual understanding of failure creates new possibilities for resistance to neoliberalism and, in doing so, makes space for ‘other goals for life’ (Halberstam, 2011).

Our work extends debates on emotion and failure within academia in several directions. Our project, based in a UK university, is one of the first to link a discussion of student affectual experiences to the growing body of critical scholarship which focuses on academic stress and excessive workloads in a context of increasingly neoliberal management approaches (Berg et al., 2016; Maclean, 2016; Mullings et al., 2016; Loveday, 2018; Tight, 2019). We argue that students are experiencing mounting pressure from these same neoliberal processes and that understanding their lived experiences of failure can help us understand how we might practically support them whilst pushing back at neoliberalism through our teaching and pastoral work. Recent literatures on slow scholarship (Mountz et al., 2015), ‘doing geography’ and feminist contributions on cultivating an ethic of care within the academy (Mcdowell, 2004, Askins and Blazek, 2017; Conradson, 2016; Batterbury, 2018; Parizeau et al., 2016; Goerish et al., 2019) have highlighted how we can engage with this challenge through our research and interactions with colleagues. Building on the insights of our research, this article begins to identify the skills and spaces that may be helpful in fostering an ethic of care through our teaching practices too.

We begin by exploring current literatures on failure within universities in a context of neoliberalism. We then bring literatures on emotions and affect into this conversation, to highlight new ways of being within universities that may offer possibilities for resistance.

While the paper's conclusions are relevant internationally, some context on the UK Higher Education landscape within which this research is situated may be helpful. Recent decades have seen UK HE dominated increasingly by marketization and rising levels of debt amongst students, with the average graduate debt – tuition fees plus maintenance costs and high rates of interest – standing at more than £50,000 for a three-year degree (Packham, 2019). Student mental health is also a major topic of concern within the UK at present (Etherson and Smith, 2018; The Guardian, 2019; Shackle, 2019). Understanding the link between failure and politics is crucial here since, as many commentators have pointed out, ideas of success and failure emerge from a very particular context – a capitalist system that is based on competition (Halberstam, 2011; Parry, 2002). Indeed, Berg et al. (2016) argue that neoliberalism constitutes the categories of ‘winner’ and ‘loser’ in the contemporary academy and increases their relevance:

“Some people were very successful in the [older] liberal academy, whilst others were not as successful, but they were usually not constituted as “losers.” Under neoliberalism, it is now very clear who the losers are: they are the ones who never get tenured or permanent jobs, they are the ones who get fired for lack of “productivity” in a system of constant surveillance and measurement of academic “production,” and if they are fortunate enough to avoid precarity, then they are the ones whose salaries stagnate (or drop) in real terms over time.” (p.172).

While we do not subscribe to such logics of ‘winner’ and ‘loser’ we have deliberately not adopted a rigid definition of ‘failure’ in this paper because we were interested in how our participants understood (and often ultimately reframed) the concept for themselves. This reframing is an important political act which may emerge when we work with failure at an affectual level in the supportive company of others through the kind of process described in this article.

2. Power, politics and failure at university

Failure has become a topical subject in universities. Recent years have seen projects creating CVs of failure (Batterbury, 2018; Haushofer, 2016), in addition to conference sessions such as those at the RGS-IBG2 and others,3 alongside academic articles dealing with failure. To date, writing on failure has focused on several key areas, the most prominent of which is the role that failure plays in fieldwork (DeLuca and Maddox, 2015; Klocker, 2015; Nairn et al., 2005; Harrowell et al., 2018).

Why is it so important to talk about failure in universities? We identify two primary rationales: an educational imperative connected to the learning process itself, and a political imperative concerned with the ongoing movement to transform academia from the grip of neoliberalism. These rationales stem from different spheres and hence are often discussed separately. However, bringing them together can create possibilities for radical pedagogies (Freire, 1970) and further resistance to neoliberalism within HE.

From an educational perspective, psychologists and educational researchers have argued that failure, when linked to a safe context of trial and error, is a necessary part of learning. Failure provides feedback on what needs to be done differently next time (see Dweck (2012, 2017) and Hymer and Gershon (2014) on growth mindsets). Contemporary neoliberal HE is anything but a safe context since staff and students are increasingly ranked against each other. For example, the CVs of failure project provided a welcome attempt to bring failure out into the open by telling tales of grants not achieved, promotions turned down and papers rejected (Batterbury, 2018; Haushofer, 2016; Jaschik, 2016). However, the sharing of failures was generally limited to those already well established on the academic career ladder, reminiscent of the reflection that “celebrating failure is the prerogative of the privileged; admitting failure is a risk for most” (Werry and O'Gorman, 2012 p.107).4

Indeed, the often light and humorous tone prevalent in many of the (professors') CVs of failure stands in marked contrast to the darker and more painful accounts of failure written from the perspective of early career researchers on temporary contracts (Peters and Turner, 2014). Such narratives from those in the increasing army of what Macfarlane (2011) terms ‘para-academia’ act as a powerful reminder of the precarious employment practices and structural inequalities present within academia (Mcdowell, 2004; Dowling, 2008).

Accounts drawing attention to the role that emotions and affects play in universities are particularly powerful here since they offer us another way of examining the sinister underbelly of neoliberalism (Askins and Blazek, 2017; Berg et al., 2016; Mullings et al., 2016; Simard-Gagnon, 2016; Loveday, 2018). Such discussions have paved the way for a more explicit discussion of mental health and wellbeing in universities. Crucially, they have connected the emotions experienced around failure to the political inequalities present within neoliberal academia which impact particularly on those at its margins. Here, the literature often focuses on early career academics and those trying to balance insecure employment status with family life. For example Berg et al. (2016) argue that the experience of precarity acts on “affective and somatic registers through constant feelings of anxiety and physical ailments”, and that these affects are deliberately employed as a tool of governance to discipline minds and bodies.

To date, few researchers have considered how such political dynamics relate to undergraduate students. This is unfortunate since explorations of staff wellbeing often cast students in the role of ‘bad guy’ by viewing them as demanding consumers who create extra work, despite mounting evidence that students themselves experience similar pressures (Etherson and Smith, 2018; Houghton and Anderson, 2017; Shackle, 2019). Indeed, a closer examination of the student experience illustrates how students are also failed by neoliberal HE institutions: an average debt of £50,000 at graduation and continued inequalities in access for students from non-privileged backgrounds (e.g. working class, first generation students, students of colour, etc.) are just a few examples of the ways in which many students are systematically marginalized and failed by the system (The Guardian, 2019, Dorling, 2019). So, what is neoliberal HE like for students? Firstly, it is important to acknowledge that students are subject to the creation of neoliberal subjectivities (Rose, 1999a, Rose, 1999b) and the same logics of enhanced competition as described by Berg et al. (2016). For example, recent media narratives around grade inflation (in which universities are purported to unjustly award more degrees at I and II:I level) undermine student achievement (see The Guardian, 2018 for one of many examples).

When universities talk about failure in relation to students, the focus is often narrowly defined in terms of grades (Rogers, 2002). However, this paper adds weight to a plethora of existing studies which show that ‘failure’ for students encompasses a much broader range of concerns including financial worries, perceived social failure and worries about ‘letting the family down’ (The Guardian, 2019). Indeed, even where low grades are concerned there are usually warning signs such as missed lectures and poor grades in coursework or mock exams, reminding us that failure is often a process rather than a one-off event (Rogers, 2002). Such a ‘process-oriented’ view of failure raises many questions, including considering how responsibility for failure is distributed. For example, it might be more accurate to think about the ways in which the university is failing the student, particularly students who come from more marginalized backgrounds (Peelo and Wareham, 2002). Equally, it is vital to recognise that failure is always socially constructed and subjective (Brown, 2002); students might be receiving what the university considers good grades and be perceived as really popular by others and yet their inner experience can still be miserable. Indeed worrying evidence on student mental health and the pressures of perfectionism is currently emerging in the UK (Etherson and Smith, 2018; The Guardian, 2019). Various attempts are being made to address this (Houghton and Anderson, 2017; Vitae, 2018; SMaRteN, 2019), however what is often missing from these otherwise very practical and useful programmes is a more radical engagement with the neoliberal power and politics currently driving these pressures. It is here that it can be particularly insightful to explore how affects and emotions can be used to highlight opportunities for resistance and change.

In this paper, we are inspired by scholarship and initiatives that use affects and emotions to push back against neoliberalism and foreground the importance of caring for self and others (Ahmed, 2004; Lorde, 1984; Vosper, 2016; Bondi, 2005). This ‘two moves in one’ distinction is important. A common critique about wellbeing initiatives is that they are used to shore up neoliberalism and further increase the pressures people experience to ‘fix’ themselves in order to carry on in a broken system (see, for example, Jon Kabat-Zinn's critique of ‘McMindfulness’ in Booth, 2017). However, approaching the issue through a more relational ontology allows us to recognise that self-care and system change often go hand in hand (Jones and Whittle, forthcoming). Indeed, a refusal to see these things as mutually exclusive has been central to arguments calling for a prioritization of care within the academy.

These literatures arise from the foundation that academia, like wider society, is relational (Goerish et al., 2019; Batterbury, 2018; Askins and Blazek, 2017, Jones and Whittle forthcoming). Consequently, their contributions are all about extending, making visible, and valorising those relationships in ways which recognise that “caring needs to come out of hiding” (Mountz et al., 2015, p.1247) and that having needs and being vulnerable are not failings (Simard-Gagnon, 2016).

However, while many of these contributions on care call for teaching and service to be actively embraced (Mcdowell, 2004; Dowling, 2008; Batterbury, 2018), there are few contributions which illustrate what care-full interactions with students might look like in practice – hence the importance of this paper. Indeed, thinking about how a feminist ethics of care can also help our students with the pressures that they face is vital.5

Secondly and equally importantly, literatures on care could benefit from focusing more closely on experiences of failure. The importance of doing so is illustrated by Halberstam's argument that failure is a political project:

“Rather than just arguing for a re-evaluation of these standards of passing and failing, The Queer Art of Failure dismantles the logics of success and failure with which we currently live. Under certain circumstances failing, losing, forgetting, unmaking, undoing, unbecoming, not knowing may in fact offer more creative, more cooperative, more surprising ways of being in the world.” (Halberstam, 2011 p.2/3).

Halberstam claims failure as a queer, feminist project arguing that these scholars and activists have always sought to reject and destabilize the basis of heteronormative capitalism. Doing so invites another perspective on the difficult feelings associated with failure: “while failure certainly comes accompanied by a host of negative affects, such as disappointment, disillusionment, and despair, it also provides the opportunity to use these negative affects to poke holes in the toxic positivity of contemporary life.” (p.3).

Having situated failure in relation to affects, emotions and neoliberalism, we introduce the project on which this article is based.

3. Introducing the project

The ‘Failure to Learn 2019 (FTL)’ project took place at Lancaster University, a university with over 13,000 students which consistently features in the top 10 of all UK league tables. FTL emerged in various ways from intersecting conversations about our interactions with students over the course of our – very different but overlapping – roles in academia. We are two lecturers from different scholarly traditions (*removed for review*), two professional life coaches (*removed for review*), a senior leader in student services (*removed for review*) and an award-winning creative writer (*removed for review*). Across our otherwise very diverse experiences, all of us were concerned about the impact that fear of failure was having on students across a range of spheres, from academic achievement and enjoyment of studies, through to mental and physical wellbeing. Our aim was to find ways of engaging with failure that would help us, our colleagues and, more importantly, our students.

4. Methodology and mistakes

As is fitting for an article about failure, FTL has two stories: the story of what we intended to do and the story of what we actually did (including our failures). Our original intention was to design an action research6 project which developed and piloted a series of innovative, coaching-based workshops and resources for students, teaching staff and student services staff. The resources would focus on reducing fear of failure and bringing attention to creative learning potential, thus delivering benefits for wellbeing, learning and life beyond university. The original project design involved a range of activities with university students and stakeholders (academics, student services staff), each with a parallel research component (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Planned action research process.

| Project activities | Aims | Parallel research component |

|---|---|---|

| A participatory design and consultation workshop with stakeholders currently involved in supporting students e.g. student learning advisors, college wellbeing officers, educational developers. | Present the main ideas and plans for the project. | Participant observation to note the main themes and learning resulting from the discussion. |

| Get input on how the project can be shaped to better support existing related activities. | ||

| 2-h interactive and experiential coaching workshops with the participating students (8 students per workshop). | Engage students to reflect on their experience of failure. | Participant observation to note the main themes and learning resulting from the discussion. |

| Support students to design alternative personal strategies to enhance their learning. | Evaluation activity to ask the participants about their experiences of the learning process. | |

| Research team debriefing session. | Capture key learning emerging from the session | Debriefing taped and analysed as part of the research process. |

| 6 week ‘testing out’ period supported through 2 group coaching calls (in groups of 6 students) to keep students on track and create an environment for peer-sharing. | Students testing out strategies in a supported environment. | Group coaching calls will not be observed or included in the formal research process to give students a ‘free’ space to experiment. |

| Students encouraged to keep a reflexive journal to capture their experiences. | Students will be given the opportunity to have all (or selected parts) of their journal analysed. | |

| Review workshop for students and stakeholders in two halves. First, a protected space for students to capture experiences. | Capture experiences of students using the strategies. Identify lessons for other students. Identify and disseminate key messages to enable staff to work creatively with failure in future. |

First half: Participant observation followed by evaluation activity. |

| The second part of the workshop will be opened up to the stakeholder group to enable the students to share key messages. | Second half: participant observation. | |

| Research team debriefing session | Capture key learning emerging from the session. | Debriefing taped and analysed as part of the research process. |

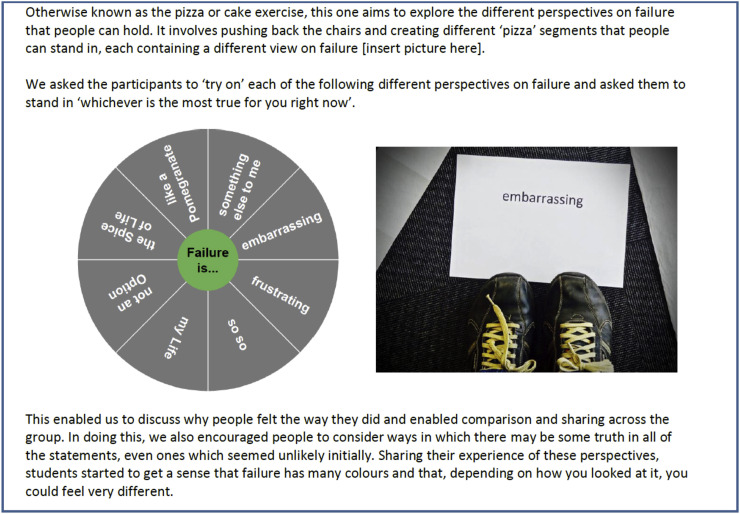

As part of the coaching-based workshops, we conducted different exercises with students (see box 2 for an example7 ). Our aim was to introduce interactive, discussion-based topics based on coaching resources whereby students could share and learn from each other.

Box 2. Alternative views of Failure – the pizza exercise.

Alt-text: Box 2

While the project did, for the most part, align with our intentions, we also experienced some significant failures. We aimed to recruit 96 undergraduate students evenly distributed across four cohorts – from our respective academic departments, students in contact with students services and via an open call.

However, failure number one was that no medical students volunteered to participate. Reflecting on this, we identified three reasons why this might be. The first was practical – medical students have busy timetables and any new activity generally has to displace something else. Second, the university and medical school where the research was located are comparatively small (with a cohort at this time of around ~50 medical students per year). Students may have felt that, due to small cohort size, any failure they experienced was highly visible, much more so than at larger medical schools, and they did not want to be ‘seen’ to be failing. Finally, throughout the recruitment process, we also reflected that the concept of failure may not be one that is part of the medical student identity (Jackman et al., 2011). Medical students may see themselves as high achieving and unwilling to admit that sometimes this may be otherwise.

Failure number two was that, in keeping with what other academics have found, the (action) research process turned out to be ‘messier’ (Harrowell et al., 2018) than anticipated. For example, one of the most basic competencies in research is to know how many people participated and yet, embarrassingly, this is hard to disentangle. Over 110 students responded to the original publicity to express an interest in taking part. However, participation turned out to be quite fluid (with students we thought had dropped out re-joining at a later point) and so keeping track of who participated in each subsequent ‘element’ of the project was difficult.

Equally, trying to strike a balance between the ‘action’ and the ‘research’ elements of the project was tricky. As Table 1 illustrates, with the exception of the sign up and evaluation forms that we quote in the article, our data consisted largely of participant observation and our own reflections as a research team, meaning that we missed out on the kind of detail that might have been possible with individual student interviews, for example. However, we had very limited resources for this work and it was therefore important to ensure that the funding went to things that would directly benefit the students rather than ‘separate’ research activities. Also, we feared that approaching individuals for interview would have perpetuated the shame and stigma that often come up around failure in a neoliberal context – in contrast, the following sections show that creating a safe shared context actively contributed to reframing these perceptions.

5. The shadowy world of failure

One of the most interesting insights emerged before our project had even begun. In talking about the project with colleagues, some welcomed it and said how much it was needed. Others reacted differently; while they could see how the project responded to the university's aim of improving student retention, they felt that a focus on failure was inappropriate for a ‘top 10’ institution.8 Could we not reframe it as focusing on success? Such reactions illustrate the political pressures discussed earlier in the paper as neoliberalism's insistence on competition makes failure both inevitable and unmentionable at the same time (Halberstam, 2011; Berg et al., 2016).

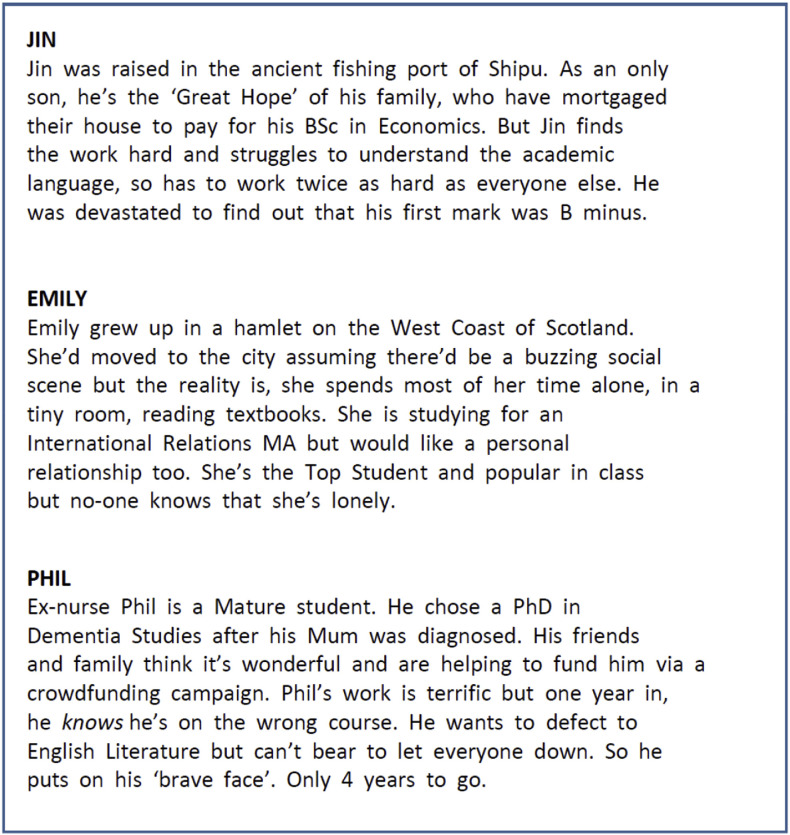

As our project progressed and we worked more with staff and students, we uncovered further support for what many educational researchers have argued, which is that success and failure cannot only be defined by external metrics; they are also inherently subjective and mean different things to different people (Brown, 2002). Our creative writer, (*removed for review*), created (fictional) portraits (box 3 ) to illustrate how failure was present in the student experience.

Box 3. Student portraits.

Alt-text: Box 3

The fictional portraits illustrate how the felt experience of failure is different to any normative understanding of the concept, thus contributing to the invisibility of failure within the student landscape. Most of the students participating in our programme were not ‘failing’ in any way that the institution might understand; they were getting good grades, attending lectures, handing in work regularly and continuing with their studies. And yet, as the portraits illustrate, failure – or, more accurately, the fear of failure – was a dominant feature of their university experience. Feeling like an imposter, not living up to your own – or others' – high expectations, loneliness or harbouring a secret fear that you are on the wrong course were just some examples of the kinds of failure experienced by the students that we worked with. These failures, which perhaps indicate the extent to which neoliberal subjectivities have taken hold within staff and students (Loveday, 2018; Rose, 1999a, Rose, 1999b), remain invisible according to many of the measures traditionally used to capture failure within HE.

Our argument in this paper is that these hidden fears are a prominent feature of the university experience and, as a result, they are just as worthy of attention and support as more ‘visible’ failures such as poor exam performance or falling retention rates. In response, we propose a focus on emotions, affects and ‘present tense’ experience to help us identify ways in which we can create new spaces of care that account for failure (Mcdowell, 2004; Askins and Blazek, 2017; Mountz et al., 2015).

6. The (deeply affectual) lived experience of failure

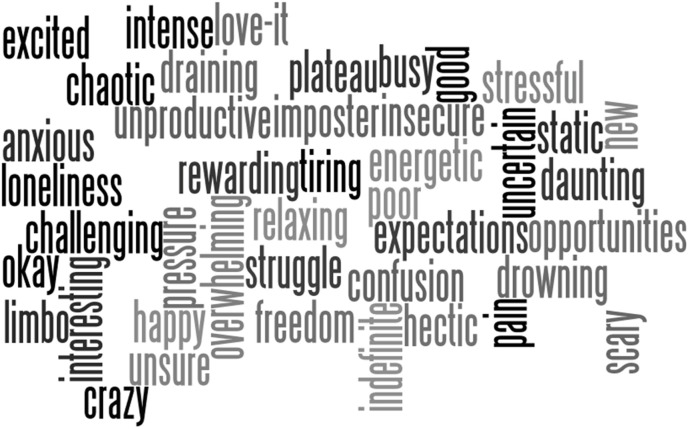

The basis for our work is the recognition that university is an acutely affectual experience for students. In workshops, we asked students to write just one word describing what they felt their university experience was like now (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Representation of students' university experience.

Fig. 1 reveals the variety of students’ affectual experiences. There are many positive adjectives which might be familiar from university prospectuses. But there are also different versions of the university experience. While some terms are ambiguous (crazy, intense, okay), others imply an altogether more difficult reality (overwhelming, scary, stressful, anxious). Being a student is clearly an intensely affectual experience which evokes a wide range of emotional responses. Negative or ambivalent feeling states are as much a part of the university experience as the more positive affects that we may be more comfortable expressing.

Acknowledging these more uncomfortable aspects of the university experience is key to supporting students experiencing fear of failure. As previously noted, many popular narratives intellectualize or distance failure by providing a different space and place from which to reframe the experience: it was horrible at the time but it's ok now because you've learnt from it, grown from it, it's made you what you are today etc. The ability to reframe failure in this way can be immensely important. Indeed, in the workshops we sometimes shared narratives of past failure which helped show how difficult experiences were often the entry point to something different and unexpected.

However there is a risk that, in reviewing failure in this way, we distance ourselves from the lived experience of it. We also risk reinforcing the neoliberal rationale behind such judgements as the implication of the example we've just discussed is that admitting to failure is only acceptable if you have overcome that condition to be successful right now (Halberstam, 2011; Berg et al., 2016). In doing so, we alienate those who are unable to find another perspective on their own experience right now. In contrast our project demonstrated that, if we are serious about helping people with fear of failure, then we need to find ways of working with it as a valid and intensely affectual experience. We also need to help people to challenge neoliberal subjectivities so that they can realise that they do not need to solve something or get to somewhere else, as they are still wholly and deeply ok right now, even though the experience of failure can be extremely confusing and painful. Thus our project needed to develop ways of relating to failure that were sophisticated enough to keep hold of these complexities.

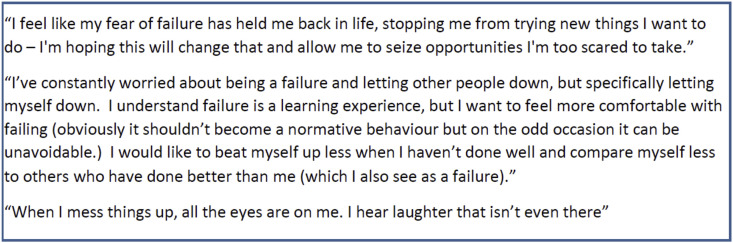

It is for this reason that we focus on failure in the present tense. Although some students presented their rationale for participating in the failure programme in positive terms, others were open about the rawness of fear of failure in their lives right now (box 4 ).

Box 4. Student reasons for signing up to the programme gathered via email.

Alt-text: Box 4

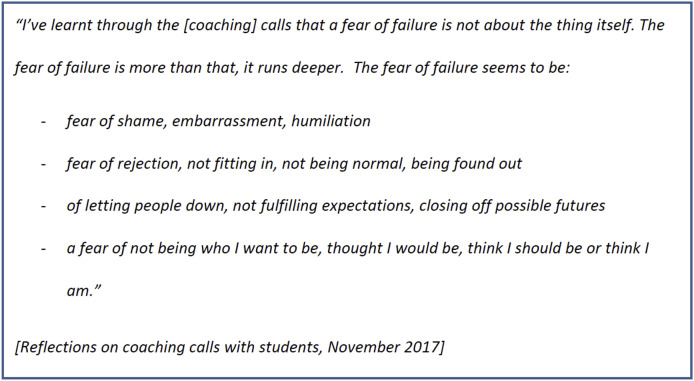

The explicit and implicit references to fear, guilt, shame, embarrassment and self-accusation were re-encountered in the workshops. We found a need not just to be able to critique and think beyond failure, but also to acknowledge the embodied and ‘in the moment’ affectual qualities of its experience. One powerful realisation was the importance of creating safe spaces for the more vulnerable affective experience of failure to be shared. In an email to the project team, lead coach (*removed for review*) reflected on what he learnt from the students about the experience of failure:

As (*removed for review*) highlights here, it is not so much the failure itself but the meaning we attach to it. Again, it is pertinent to reflect on these meanings in a context of neoliberalism (recall Berg et al.‘s earlier comments that, while relative success and failure have always existed, neoliberalism's focus on winners and losers has made them matter more). Crucially, however, this perceived meaning is an affectual experience: if we don't recognise this then we miss a big piece of what the experience is like (Brown, 2010, 2012).

Thinking about these meanings highlighted another key finding regarding the language we use to talk about failure. At our first workshop with stakeholders, it became apparent that we would be missing something if we did not engage directly with the discomforting experience of failure itself. As a result, the publicity that we used for the project (Fig. 2 ) placed failure centre stage.

Fig. 2.

Project publicity.

We found that using this approach meant that a different set of students came to the workshops: some stated explicitly that they would not have come to a workshop on success. (*removed for review*), our creative writer, commented that there was a vulnerability and fragility to the group that would not have had space to breathe in a workshop on success. Although language use is complex, it has a role in creating room for a ‘present tense’ experience of failure.

7. Failure as socially shared

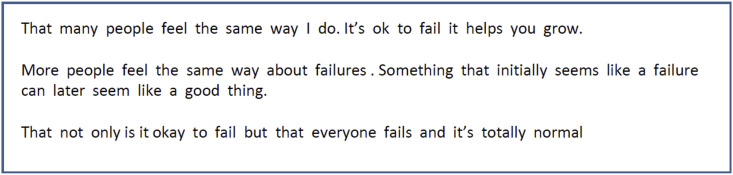

So far, we have presented a picture of failure that feels intensely personal. This framing explains why failure is hidden within HE: because failure under neoliberalism is often experienced as shameful and indicative of individual flaw, it feels dangerous to share (Brown, 2010, 2012). Our project demonstrated that, while the affectual and emotional experience of failure is deeply personal, it is also socially shared. One of the most powerful conclusions from the workshops – for both us and the students – was a realisation that the affectual experience of failure was not a shaming personal secret but common to many across the university.

One could argue that there is nothing very surprising about this observation since there is a rich body of work which conceptualises emotions and affects as relational and circulating, particularly within the workplace (Whittle, 2015; Rafaeli and Worline, 2001). Nevertheless, we found that the actual experience of sharing with others within a safe space was different from just knowing intellectually that others probably feel the same. This became a prominent feature for us as participant observers in the workshops; we observed that as people opened up during the workshops and trust levels grew, the sense of relief at discovering that others felt the same way was palpable. Equally, in project feedback forms, students said that it was helpful to know that other people experienced the same feelings as they did (box 5 ).

Box 5. Student evaluation forms showing relating differently to failure.

Alt-text: Box 5

Creating a safe space in which the socially-shared nature of failure could be explored was, in itself, a powerful intervention. The sharing process we witnessed had strong parallels with Mountz et al.'s (2015) work, where sharing personal experience was an important prerequisite to systemic change: “Early iterations of the manuscript had many uses of the term “I” as we shared individual stories with one another. As our writing progressed, we moved together from the isolating effects of the work conditions analysed here (paralysis, guilt, shame, distress) to a more collective form of response and action” (p.1239).

We next explore the implications of these findings and consider how to develop meaningful spaces of failure within HE.

8. Discussion: What does it mean to create spaces for failure within the university?

Our focus on failure as socially shared supports previous work which stresses the link between the intense pressure of failure and neoliberalism's insistence on winners and losers (Berg et al., 2016). Halberstam's (2011) critique, for example, draws on Gramsci to argue that what counts as ‘success’ within late capitalism/neoliberalism has become increasingly narrowly defined:

“Heteronormative common sense leads to the equation of success with advancement, capital accumulation, family, ethical conduct, and hope. Other subordinate, queer, or counterhegemonic modes of common sense lead to the association of failure with nonconformity, anti-capitalist practices, non-reproductive life styles, negativity, and critique”. P.89.

Under this system it is perhaps unsurprising that institutions under increasing pressure to be successful might relegate anything which disputes these narratives to the margins, placing ‘the individual’ at the centre of failure. Such analyses might explain the discomfort that some felt on hearing of our project. In developing this line of thinking further, we could ask whether the same process of externalising responsibility for failure which leads to staff being singled out for discrimination (Berg et al., 2016) is also responsible for struggling students being quietly siphoned off to student support services. Of course, student support services play a hugely valuable role in creating spaces of care within academia; but if we are serious about acknowledging failure as a valid shared experience then it is important to be aware of systemic pressures which externalise the costs of an increasingly narrow definition of success by relegating those who do not conform to the margins. For these are the ways in which failure becomes pathologized, individualised and hidden.9

If failure creates important spaces for resistance (Halberstam, 2011), how do we practice that resistance? Following Harrowell et al. (2018) and Mcdowell (2004), we argue that this involves creating spaces for failure in our work and cultivating an ethic of care in the university (Goerisch et al., 2019; Batterbury, 2015). For some academics, this was exemplified in the 2018 UCU strike, in which new networks and connections were formed online and ‘teach-out’ meetings opened new discussions on what it meant to be an academic in the neoliberal academy (Davies, 2019). Based on our work with students, we make two general observations before providing some more specific examples of what such spaces might look like.

First, we call for an increased focus on the affectual and emotional dimensions of experience within HE. There is a growing literature on the importance of emotions within organizations but, in reality, emotional and affectual experiences continue to be side-lined not seen as a central and valid part of engagement with work and study. Even where emotional and affectual dimensions are actively embraced, more ‘positive’ emotions are courted (Rafaeli and Worline, 2001). Dealing with the more discomforting aspects of experience – shame, fear, anger – is altogether harder. Our work illustrates the importance of acknowledging and valuing the diversity of affectual experience in contrast to the increased focus on marketing in the neoliberal university which makes it harder to acknowledge a student experience which is not 100 per cent positive. Parallel observations can also be made about the relentlessly public performance of success on social media. Nevertheless, in reality, many aspects of the student experience can be intensely difficult. We need to find ways in which uncomfortable affectual experiences can be acknowledged, held and worked with. Doing this is key to working positively with failure since, as we have argued, if we focus only on externally-defined markers such as failed exams, we will misunderstand the significance of failure for our students.

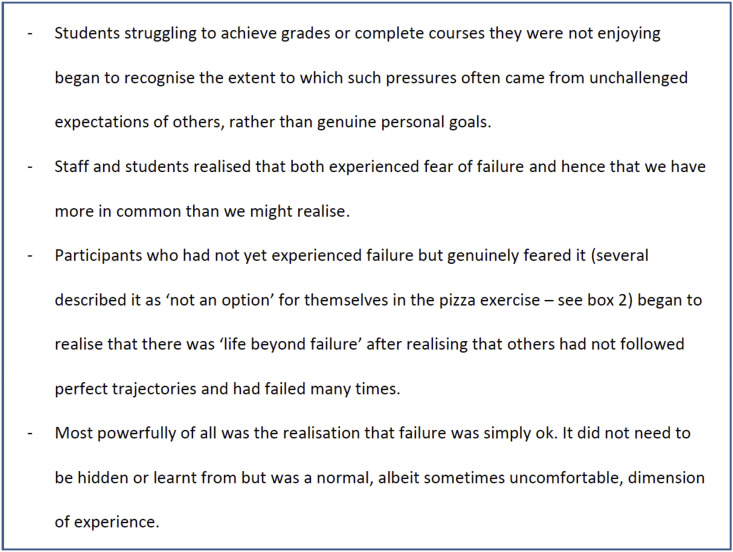

Second, we need to recognise the shared nature of lived experience. Building on literature exploring emotions and affects as relational, we have argued that a practical contribution of our project was the creation of safe spaces to share fears of failure. In so doing, students could begin to reframe it from something individual and shaming to something that we all experience, particularly in the shared context of a neoliberal, highly-competitive university environment. Many of the prominent critiques made of approaches which involve learning from affectual experience (coaching, counselling, reflection, mindfulness) is that they extend the logic of neoliberalism by encouraging people to work on themselves (Rose, 1999a, Rose, 1999b) in ways which seem liberating for the individual but fail to counter the dominant political and social structures that have contributed to their alienation (Simard-Gagnon, 2016). However, our work supports an alternative perspective which argues that, while emotions can become a vehicle for self-governance (Whittle, 2015), they can also become a powerful route to resistance, particularly through the discovery of the ways in which they are shared with others.

While more research would be required to say this with certainty, our observations of the student workshops appeared to show this process in action whereby instances of sharing led to ‘lightbulb’ moments for many of the participants (including ourselves). For example:

These small examples emphasise the shared nature of the experience and how the ability to find new perspectives on situations allowed students to tell themselves new stories. They began to think differently about ‘failure’ and its relationship to the wider institutional, social and economic context in ways which seemed to indicate the beginnings of resistance. Above all, then, we would argue that both failure itself and the exercises that we trialled in our workshops need to be experienced in the present tense rather than just intellectualized, before the real impacts become clear.

What might this actually look like in practice, with spaces for failure created and an ethic of care in HE? We conclude with suggestions we might try and incorporate into university life at different levels. They might fail (of course!) but, if they do, this provides a basis for further learning and experimentation. Indeed, we would argue that going beyond critique to active and generative experiments is crucial, as Bengtsen and Barnet (2019) argue: “Critiquing the current status and shape of the university is one thing but reaching into vistas and pathways that might lie on the other side of the present is an entirely different thing.” (p.4).

9. Conclusion: Covid and beyond – new spaces and skills for failure?

If we are serious about normalising failure and bringing it into the mainstream of academic departments we will need to create physical and temporal spaces where failure – and all its affectual baggage – is safe to emerge. In considering ‘hidden’ failure, we recognised that while students do often take advantage of ‘official’ routes for sharing difficulties (e.g. counselling services), sharing was most likely to take place in ‘informal’ spaces where trusted interpersonal relationships had time and space to develop.

For students, this might be flatmates, administrative staff (to whom students submit coursework) or a lecturer that they saw regularly. For staff, this might be trusted colleagues rather than a line manager. Such conclusions are important since many of these informal spaces are becoming eroded in the time and space pressures on the university day, with no formal lunch breaks or genuine social space in academic departments. Meanwhile, shifts towards online submission of coursework and increased fragmentation of teaching across modules may reduce face-to-face contact and the chance to build relationships with students and colleagues over weeks or months. Again, the 2018 UCU strike vividly exemplified this lack, when many re-discovered the delight of conversation with staff and students on the picket line and realised that these interactions are largely absent from the university day.

Thinking creatively about these spaces – and what it is that makes them safe and effective for the kinds of sharing that we discuss in this paper – is particularly important and challenging right now. As we completed the revisions to this paper in June 2020, the world was still coming to terms with what the Covid-19 pandemic means for the ways in which we live our lives going forwards. Clearly, the repercussions will be immense across so many different areas of life and yet, amidst all the chaos, care in all its forms has never been more important to our ability to recover and restore in progressive ways.

Thinking beyond space, however, working with the affectual dimensions of failure may also require new skills that are not routinely taught or practiced within contemporary HE. In particular, what we do with the painful ‘present tense’ experience of failure? Working productively with these affects is a crucial part of the process which may require not just an intellectual embracing of failure but an emotional and relational wisdom for relating to it differently.

Working with coaches and a creative writer encouraged us to work with failure experientially, in the present moment, rather than intellectualizing (and therefore distancing it), which has led to the learning captured in this paper. Consequently, we are keen to explore how approaches which focus on being and experience, rather than narratives of progress, doing or achievement, might be relevant. Many possible approaches may be appropriate to explore, but based on the experiences of our project team, we think that a coaching approach based on techniques from mindfulness and yoga that offer ways to engage with difficult experiences whilst also retaining perspective could be a useful starting point. We have not had space here to engage with the wealth of research that examines coaching (Lovell, 2018), or that which underpins the coaching approach taken (Gill and Medd, 2013, 2015), but investigations of mindfulness have concluded that there are benefits for conditions including anxiety and depression (Kabat Zinn, 2003; Teasdale et al., 2000), and emerging research on yoga nidra suggests similar outcomes (iRest, 2019). However, most studies only capture outcomes for individuals, rather than reflecting the way that these approaches are based on relational ontologies. Consequently, further research should exploring their potential for wider social and political change, particularly if taught as part of a group setting where sharing and peer support is encouraged. In this way, we can explore the potential contribution that such diverse approaches could have in building a more inclusive and care-full academy.

Acknowledgements

Huge thanks to Lancaster University Friends Programme for funding the work on which this project was based. Especial thanks to the project team, the student participants, the editor and anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Footnotes

Reclaiming failure in geography: academic honesty in a neoliberal world. Convened by Thom Davies, Eleanor Harrowell and Tom Disney, RGS-IBG (2018).

For example, the BSA Early Career Forum Event: Imposter Syndrome as a Public Feeling in Higher Education at the School of Education, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, UK (2018) and the 16th Durham Blackboard Users Conference: Learning from Failure (2016).

Other relevant examples include the Museum of Failure (2019) and examples from medical education in which senior leaders in the General Medical Council and British Medical Association share their ‘worst’ failures (National Patient Safety Agency, 2005).

As a reviewer of this paper wisely pointed out, “academia may exist in higher education but higher education is not just about academics”.

This project received approval from the university's research ethics committee.

Further examples can be found in the guide that we produced for students following the project: Failure: A Guide for Students http://www.failuretolearn.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Failure-A-guide-for-students-5.pdf and in (*removed for review*).

(*removed for review*).

See also: narratives of personal resilience and the need to redeem it (DeVerteuil and Golubchikov, 2016) and ‘grit’ (Duckworth, 2017).

References

- Ahmed S. Routledge; New York: 2004. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. [Google Scholar]

- Askins K., Blazek M. Feeling our way: academia, emotions and a politics of care. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2017;18(8):1086–1105. doi: 10.1080/14649365.2016.1240224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Batterbury S. Who are the radical academics today? The Winnower. 2015 https://thewinnower.com/papers/327-who-are-the-radical-academics-today [Google Scholar]

- Batterbury S. Academic resume of failures. 2018. http://simonbatterbury.net/Resume%20of%20failures.pdf [Accessed 21 August 2018]

- Bengtsen S.E., Barnet R. vol. 1. 2019. pp. 1–8. (Gimpsing the Future University in Philosophy and Theory in Higher Education). 3. [Google Scholar]

- Berg L., Huijbens E., Gutson Larsen H. Producing anxiety in the neoliberal university. Can. Geogr. 2016;60(2):168–180. [Google Scholar]

- Bondi Liz. Working the spaces of neo-liberal subjectivity: psychotherapeutic technologies, professionalisation and counselling. Antipode. 2005;37(3):497–514. [Google Scholar]

- Booth R. 2017. Interview. Master of Mindfulness, Jon Kabat-Zinn: ‘People Are Losing Their Minds. That Is what We Need to Wake up to’ the Guardian.https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2017/oct/22/mindfulness-jon-kabat-zinn-depression-trump-grenfell [Accessed 30 April 2019] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. Student counselling and student failure. In: Peelo M., Wareham T., editors. Failing Students in Higher Education. Open University Press; Buckingham: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Brown B. Hazelden; Center City: 2010. The Gifts of Imperfection: Letting Go of Who We Think We Should Be and Embracing Who We Are. [Google Scholar]

- Brown B. Penguin/Gotham; 2012. Daring Greatly: How the Courage to Be Vulnerable Transforms the Way We Live, Love, Parent, and Lead. [Google Scholar]

- Conradson D. Fostering student mental well-being through supportive learning communities. Can. Geogr. 2016;60(2):239–244. [Google Scholar]

- Davies G. Goodwill hunting after the USS strike. USS briefs. 2019 https://medium.com/ussbriefs/goodwill-hunting-after-the-uss-strike-3b2e302d0dc7 [accessed 2 May 2019] [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca J.R., Maddox C.B. Tales from the ethnographic field navigating feelings of guilt and privilege in the research process. Field Methods. 2015;28(3):284–299. [Google Scholar]

- DeVerteuil G., Golubchikov O. vol. 20. 2016. pp. 143–151. (Can Resilience Be Redeemed? Resilience as a Metaphor for Change, Not against Change. City). [Google Scholar]

- Dorling D. Kindness: a new kind of rigour for British Geographers. Emotion, Space and Society. 2019;33 [Google Scholar]

- Dowling R. Geographies of identity: labouring in the “neoliberal” university. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2008;32(6):812–820. [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth A. Vermilion; London: 2017. Grit : Why Passion and Resilience Are the Secrets to Success. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck C. 2012. Mindset: How You Can Fulfil Your Potential. (Robinson) [Google Scholar]

- Dweck C. 2017. Mindset Online.https://mindsetonline.com/ [Accessed 20 January 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Etherson M., Smith M. The Conversation; 2018. How Perfectionism Can Lead to Depression in Students.https://theconversation.com/how-perfectionism-can-lead-to-depression-in-students-97719 [Accessed 30 April 2019] [Google Scholar]

- Failure to Learn Failure to learn. failure to grow. 2019 www.failuretolearn.com [Accessed 30 April 2019] [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. Herder and Herder; New York: 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. [Google Scholar]

- Gill J., Medd W. Open University Press; Maidenhead: 2013. Your PhD Coach: How to Get the PhD Experience You Want. [Google Scholar]

- Gill J., Medd W. Palgrave Study Skills; London: 2015. Get Sorted: How to Make the Most of Your Student Experience. [Google Scholar]

- Goerisch D., Basiliere J., Rosener A., McKee K., Hunt J., Parker T.M. Mentoring with: reimagining mentoring across the university. Gend. Place Cult. 2019;26(12):1740–1758. [Google Scholar]

- Halberstam J. Duke University Press; Durham, NC: 2011. The Queer Art of Failure. [Google Scholar]

- Harrowell E., Davies T., Disney T.( Making space for failure in geographic research. Prof. Geogr. 2018;70(2):230–238. doi: 10.1080/00330124.2017.1347799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haushofer S. Johannes Haushofer: CV of failures. 2016. https://www.princeton.edu/»joha/Johannes_Haushofer_C V_of_Failures.pdf (accessed 6 December 2016)

- Houghton A.M., Anderson J. Embedding mental wellbeing in the curriculum: maximising success in higher education. The Higher Education Academy. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- Hymer B., Gershon M. Teacher’s Pocketbooks; Alresford, Hants: 2014. The Growth Mindset Pocketbook. [Google Scholar]

- iRest Yoga Nidra Research 2019. https://www.irest.org/irest-research [Accessed 30 April 2019.

- Jackman K., Wilson I., Seaton M., Craven R. Big Fish in a Big Pond: a study of academic self concept in first year medical students. BMC Med. Educ. 2011;11 doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-11-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaschik S. Princeton academic’s ‘failure CV’ sparks debate on success. High Educ. 2016 https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/princeton-academics-failure-cv-sparks-debate-success [Accessed 1 May 2019] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C.H. and Whittle, R. (forthcoming) Researcher Self Care and Caring in the Research Community. Area.

- Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness‐based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2003;10(2):144–156. [Google Scholar]

- Klocker N. Participatory action research: the distress of (not) making a difference. Emotion, Space and Society. 2015;17:37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lorde A. Ten Speed Press; 1984. Sister Outsider. [Google Scholar]

- Loveday V. The neurotic academic: anxiety, casualisation, and governance in the neoliberalising university. Journal of Cultural Economy. 2018;11(2):154–166. [Google Scholar]

- Lovell B. What do we know about coaching in medical education? A literature review. Med. Educ. 2018;52:376–390. doi: 10.1111/medu.13482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane B. The morphing of academic practice: unbundling and the rise of the para-academic. High Educ. Q. 2011;65(1):59–73. [Google Scholar]

- Maclean K. Sanity, “madness,” and the academy. Can. Geogr. 2016;60(2):181–191. [Google Scholar]

- Mcdowell Linda. Work, workfare, work/life balance and an ethic of care. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2004;28(2):145–163. April 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mizrahi T. Managing medical mistakes: ideology, insularity and accountability among internists-in-training. Soc. Sci. Med. 1984;19(2):135–146. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(84)90280-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountz Alison, Bonds Anne, Mansfield Becky, Loyd Jenna, Hyndman Jennifer, Walton-Roberts Margaret, Basu Ranu, Whitson Risa, Hawkins Roberta, Hamilton Trina, Curran Winifred. For slow scholarship: a feminist politics of resistance through collective action in the neoliberal university. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies. 2015;14(4):1235–1259. https://www.acme-journal.org/index.php/acme/article/view/1058 [Google Scholar]

- Mullings B., Peake L., Parizeau K. Cultivating and ethic of wellness in Geography. Can. Geogr. 2016;60(2):161–167. [Google Scholar]

- Nairn K., Munro J., Smith A.B. A counter-narrative of a ‘failed’ interview. Qual. Res. 2005;5(2):221–244. [Google Scholar]

- National Patient Safety Agency Medical error. 2005. https://docs.google.com/file/d/0B91IZUXz1ohXWG4zdXVJSHlpTkk/edit [accessed 1 May 2019]

- Packham A. The Guardian; 2019. Is a British University Degree Really Worth it Anymore?https://www.theguardian.com/news/2019/aug/12/is-a-british-university-degree-really-worth-it-any-more [Accessed 25th March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Parizeau K., Shillington L., Hawkins R., Sultana F., Mountz A., Mullings B., Peake L. Breaking the silence: a feminist call to action. Can. Geogr. 2016;60(2):192–204. [Google Scholar]

- Parry G. A short history of failure. In: Peelo M., Wareham T., editors. Failing Students in Higher Education. Open University Press; Buckingham: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Peelo M., Wareham T., editors. Failing Students in Higher Education. Open University Press; Buckingham: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Peters K., Turner J. Fixed-term and temporary: teaching fellows, tactics, and the negotiation of contingent labour in the UK higher education system. Environ. Plann. 2014;46(10):2317–2331. [Google Scholar]

- Rafaeli A., Worline M. Individual emotion in work organizations. Soc. Sci. Inf. 2001;40:95–123. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers C. Developing a positive approach to failure. In: Peelo M., Wareham T., editors. Failing Students in Higher Education. Open University Press; Buckingham: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rose N. Self Routledge; London: 1999. Governing the Soul: the Shaping of the Private. [Google Scholar]

- Rose N. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1999. Powers of Freedom: Reframing Political Thought. [Google Scholar]

- Shackle S. 2019. ‘’The Way Universities Are Run Is Making Us Ill’: inside the Student Mental Health crisis'The Guardian.https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/sep/27/anxiety-mental-breakdowns-depression-uk-students [02.11.2019] [Google Scholar]

- Simard-Gagnon L. Everyone is fed, bathed, asleep, and I have made it through another day: problematizing accommodation, resilience, and care in the neoliberal academy. Can. Geogr. 2016;60(2):219–225. [Google Scholar]

- SMaRteN . 2019. Student Mental Health Research Network.https://www.smarten.org.uk/ [Accessed 30 April 2019] [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale J.D., Segal Z.V., Williams J.M.G., Ridgeway V.A., Soulsby J.M., Lau M.A. Prevention of relapse/recurrence in major depression by mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2000;68:615–623. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.4.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Guardian UK universities face grade inflation crackdown. 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2018/oct/22/uk-universities-face-grade-inflation-crackdown [Accessed 1 May 2019]

- The Guardian . A University Crisis; 2019. Mental Health.https://www.theguardian.com/education/series/mental-health-a-university-crisis [Accessed 30 April 2019] [Google Scholar]

- The Museum of Failure 2019. https://failuremuseum.com/ [accessed 1 May 2019]

- Tight M. The neoliberal turn in Higher Education. High Educ. Q. 2019;73:273–284. [Google Scholar]

- Vitae . 2018. Exploring Wellbeing and Mental Health and Associated Support Services for Postgraduate Researchers.https://re.ukri.org/documents/2018/mental-health-report/ [Accessed 30th April 2019] [Google Scholar]

- Vosper N. The Guardian; 2016. What Makes Me Tired when Organising with Middle Class Comrades.https://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2016/jun/08/burnout-activism-working-class-organising-with-middle-class-comrades [Accessed 30th April 2019] [Google Scholar]

- Werry M., O'Gorman R. The anatomy of failure: an inventory. Perform. Res. 2012;17(1):105–110. doi: 10.1080/13528165.2012.651872. [DOI] [Google Scholar]