Abstract

Microtubule associated protein Tau (MAPT) is a phospho-protein within neurons of the brain. Aggregation of tau is the leading cause of tauopathies such as Alzheimer’s disease. Tau undergoes several post-translational modifications of which phosphorylation and O-GlcNAcylation are key chemical modifications. Tau aggregates into paired helical filaments and neurofibrillary tangles upon hyperphosphorylation whereas O-GlcNAcylation stabilizes the soluble form of Tau. How specific phosphorylation and/or O-GlcNAcylation events influence Tau conformations remains largely unknown due to the disordered nature of Tau. In this study, we have investigated the phosphorylation and O-GlcNAcylation induced conformational effects on a Tau segment (Tau225–246) from the proline-rich domain (P2), by performing metadynamics simulations. We studied two different phosphorylation patterns; Tau225–246 phosphorylated at T231 and S235, and Tau225–246 phosphorylated at T231, S235, S237, and S238. We also study O-GlcNAcylation at T231 and S235. We find that phosphorylation leads to the formation of strong salt-bridge contacts with adjacent lysine and arginine residues, which disrupts the native β-sheet structure observed in Tau225–246. We also observe the formation of a transient α-helix (238SAKSRLQ244) when Tau225–246 is phosphorylated at four sites. In contrast, O-GlcNAcylation showed only modest structural effect and resembles the native form of the peptide. Our studies suggest the opposing structural effects of both PTMs and the importance of salt-bridges in governing the conformational preferences upon phosphorylation, highlighting the role of proximal Arginine and Lysine upon hyper-phosphorylation.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Protein posttranslational modification (PTM) is among the key phenomenon in regulating protein activity as well as its diversity in structure and function. To date, phosphorylation is the highly explored PTM as it can be detected in vivo and in vitro effortlessly.1 Introducing a charged, anionic/dianionic tetrahedral phosphate group on Ser/Thr/Tyr side chain induces altered conformations in protein microenvironments, primarily due to the formation of salt bridges.2 Another PTM analogous to protein phosphorylation is O-Glycosylation, which also targets the alcoholic side chains of Ser/Thr/Tyr. Amongst various O-glycosylation’s, the addition of β-linked N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) is the only PTM which is observed within the nucleo-cytoplasmic compartments of all metazoans. O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation are involved in a complex interplay involving cell-signaling pathways, protein transcription and cytoskeletal regulatory proteins activity.3,4 Protein phosphatase (an enzyme that removes O-phosphate) is found in a dynamic complex with O-GlcNAc transferase (an enzyme that attaches O-GlcNAc), indicating that, in many cases, this enzyme complex both removes O-phosphate and concomitantly attaches O-GlcNAc to serine and threonine.4 Many cellular functions are phosphoregulated. O-GlcNAcylation at these sites may interfere with critical control mechanisms due to reciprocal relationship with phosphorylation. Both modifications have been observed in a reciprocal relationship for tumor-associated SV-40 Large T antigen.5–7 Several experimental studies have shown opposing structural and functional effects as well as cross-regulation of phosphorylation and O-GlcNAcylation.6,8–10 Hence it is important to understand phosphorylation and O-GlcNAcylation induced structural effects on biologically crucial pathways such as cell signaling and etiology of the disease.

Tau (tubulin-associated unit), identified in 1975, is a family of microtubule (MT)-associated proteins which are expressed predominantly within neurites and axons in the adult brain.11,12 The largest tau isoform (htau40) in the brain contains 441 amino acids comprising of two N-terminal inserts, proline-rich domain and four repeat domains that bind to MT (Figure 1).13 Tau interact with microtubules and stabilize the cytoskeleton of neurons.14 The short sequence 225KVAVVR230 localized to the second proline-rich region (P2) and the two hexapeptide motifs (275VQIINK280 and 306VQIVYK311) in repeats R2 and R3 shows the strongest interaction with MTs.15–17 It has been found that the basic residues in these regions K225, R230, K274, and K281 are critical for MT binding and polymerization.18,19

Figure 1.

Pictorial representation of tau protein, isoform htau40 (441 residues)45. N1 and N2 are the two 29-residue inserts near the N-terminus; P1:I151-Y197 and P2: S198-L243 are proline-rich domain; R1-R4: Q244-N368, are the four repeats in the C-terminal half; R’ is 5th repeat domain K369-S400 and C-terminal tail G401-L441. Definition of domains41: Projection domain (MI-Y197, does not bind to microtubules by itself), Assembly domain (S198-L441, binds to microtubules).

The neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) found in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) brains are composed primarily of the protein tau in a hyper-phosphorylated state, which disrupts microtubule assembly. Phosphorylation is the most common tau post-translational modification.20 Tau protein consists of approximately 85 known phosphorylation sites among which there are 45 serine, 35 threonine, and only 5 tyrosine sites.21–24 It is well documented that an increase in tau phosphorylation reduces its affinity for microtubules, which results in neuronal cytoskeleton destabilization depending on the number and location of phosphorylation sites.25–28 Tau phosphorylation at key sites involving T231, S235, and S262 have a major role in dissociation of tau from microtubules. It was found that Tau phosphorylated at T231, S235 and S262 reduced their binding to microtubules by a factor of 26%, 9%, and 33% respectively when compared to native un-phosphorylated Tau.29 Amniai et al. showed that phosphorylation of both Ser202/Thr205 and Thr231/Ser235 in the proline-rich domain of tau do not allow tubulin to polymerize into MT.30 Phosphorylation at Thr231 and S235 is established as a valid biochemical marker for AD diagnosis.31–33 Hyperphosphorylation of tau in AD is a direct result of it’s reduced O-GlcNAcylation.34,35 AD is characterized by an inverse relation between tau phosphorylation and O-GlcNAcylation 36–38 and in vitro, the de-glycosylation of tau tangles converts them into bundles of straight filaments and restores their accessibility to microtubules.34 These studies suggest that O-glycosylation protects tau from hyper-phosphorylation and consequently is expected to prevent NFT formation.

Structurally Tau has been classified to belong to the family of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDP). The full-length crystal structure of Tau has not been solved. Solution studies of Tau and small fragments of Tau using predominantly NMR techniques have observed transient secondary structure elements, like α-helix and PPII, in specific regions of the sequence. Schwalbe et. al. performed NMR studies to gauge the structural impact of phosphorylation on the proline-rich region P2 (Tau225–246) of tau which contains the T231 PTM site, which has been implicated in the binding of Tau with MT. As per the “jaws” microtubule-binding model proposed by Mandelkow et. al. and global hairpin structural model of tau, structural changes in the proline-rich regions could have a major effect on microtubule binding affinity.31,39–41 Tau225–246 also corresponds to a known recognition sequence of the WW domain of Pin1, which binds tau protein in a PPII conformation upon phosphorylation.42 These results suggest that hyperphosphorylation of proline-rich sequences in tau may lead to its global reorganization.

With this in mind, in this study, we investigate the effect of phosphorylation and O-GlcNAcylation on the proline-rich P2 domain (Tau225–246) of Tau. Tau225–246 is a 22-residue fragment of tau protein from the P2 (198–243) proline-rich domain just before the R1-R4 repeat units (Figure 1). In addition to T231, Tau225–246 contains three additional PTM sites S235, S237, and S238. This allows us to study the influence of multiple PTMs on the overall structure of Tau225–246. Additionally the availability of structural information from NMR experiments for native Tau225–246, Tau225–246 phosphorylated at two-sites (T231 and S235) and Tau225–246 phosphorylated at four-sites (T231, S235, S237, and S238) allows us to compare the simulations directly to the experimental data. Owing to the disordered nature of the Tau peptides we perform molecular dynamics (MD) simulations using enhanced sampling techniques to improve the conformational sampling efficiency. We also explore the efficiency of the Amber ff99SBws43 and CHARMM36m44 force fields in describing the conformational dynamics of the IDPs and the influence of PTMs on the structure of the disordered peptides used in the study.

Methods

Systems

We study five systems as described in Table 1: (i) Tauff99SBws - Unmodified Tau225–246 simulated with Amber ff99SBws force field (ii) TauC36m - Unmodified Tau225–246 simulated with CHARMM36m force field (iii) Tau2p - phosphorylated Tau225–246, phosphorylated at residues T231 and S235 (iv) Tau4p - phosphorylated Tau225–246, phosphorylated at residues, T231, S235, S237 and S238 and (v) TauO-GlcNAc - O-GlcNAcylated Tau225–246, O-GlcNAcylated at residues T231 and S235. All the phosphorylated and O-GlcNAcylated systems were studied using the CHARMM36m force field as described in detail in the simulation protocol section. Hereafter unmodified tau225–246 simulated with Amber ff99SBws and CHARMM36m force fields will be referred to as tauff99SBws and tauC36m respectively. Phosphorylated tau will be referred to as tau2p (2 sites phosphorylated) and tau4p (4 sites phosphorylated), and O-GlcNAcylated tau will be referred to as tauO-GlcNAc. The choice of the systems was based on experimental work by Brister et al6. and Schwalbe et al.16 and the availability of NMR data for direct comparison with the simulation studies. It must also be noted that phosphorylation at residues T231 and S235 is observed in normal as well as AD brain, whereas S237 and S238 are found phosphorylated only in the AD brain.20

Table 1:

Tau225–246 peptide ensembles simulated.

| System | PTM sites | Force Field | Water model | No of water molecules |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tauff99SBws | Unmodified | Amber ff99SBws | TIP4P/2005 | 5350 |

| TauC36m | Unmodified | CHARMM36m | TIP3P | 5212 |

| Tau2p | T231, S235 | CHARMM36m | TIP3P | 5216 |

| Tau4p | T231, S235, S237, S238 | CHARMM36m | TIP3P | 5213 |

| TauO-GlcNAc | T231, S235 | CHARMM36m | TIP3P | 5159 |

Simulation protocol

For this study, we used Amber ff99SBws (an adaptation of Amber ff99SB to use TIP4P/2005 with scaled water interactions) and the CHARMM36m force field designed especially for simulating intrinsically disordered proteins. We perform our simulations for the unmodified peptide by employing both the force fields; Amber ff99SBws and CHARMM36m along with the TIP4P/200546 and TIP3P47 water model respectively, whereas for phosphorylated and O-GlcNAcylated peptides only the CHARMM36m force field was used for the simulations. The CHARMM protein and carbohydrate force fields were used to account for the phosphate and carbohydrate PTMs for the simulation of modified peptides.44,48 The starting geometry was set up by generating a random coil configuration of Tau225–246 peptide. The dihedral values for the initial random coil are given in Table S1 of supplementary information file. The system is solvated in a truncated octahedron box with 6 nm spaced face and NaCl ions are added to neutralize the system charges. This was followed by 5000 steps of steepest descent to minimize the system followed by 100 ps of NVT and NPT equilibration at stochastic dynamics. Sixteen replicas are generated within a temperature range of 300 to 518.4 K. To adjust replica temperatures between 300 K and the highest temperature of interest geometric spacing is used to obtain uniform acceptance probability (~20%) between all adjacent replica pairs. All the replicas in each simulation are initiated from extended coil structures (Table S1). Each temperature replica was equilibrated for 200 ps to equilibrate the potential energy of the replicas. The potential energy was biased using 500 kJ/mol Gaussian widths, 1.2 kJ/mol initial Gaussian heights, with Gaussian potentials added every 2000 steps, with a bias factor of 36 to conduct simulations in the well-tempered ensemble (WTE). All metadynamics parameters are implemented in the plugin for free energy calculation, PLUMED v2.4.0.49 The system dynamics were propagated using leapfrog stochastic dynamics with a 1ps friction coefficient. The replica exchange was attempted every 500 steps. A 12 Å cutoff was used for Lennard-Jones interactions.50 Electrostatic interactions are calculated using the Particle-Mesh Ewald (PME) method with 1.0 nm real space cutoff.51 Each temperature replica was simulated for 200 ns NVT production simulations performed with the GROMACS52 version 2016.4 simulation package for a total simulation time of 3.2 μs, using a time step of 2 fs.

Only the 300 K temperature replica was used for analysis. The convergence of the simulations was checked by measuring the radius of gyration (Rg) and end-to-end (E2E) distance of the peptide. Based on the convergence analysis the last 100 ns of the production simulations were used for analyzing the results. Structural RMSD clustering analysis is performed based on the gromos method using a distance cutoff of 0.35 nm.

Results

For the present study, we simulate a 22 residue long fragment from the proline-rich domain of tau protein, Tau225−246. The effect of phosphorylation on this fragment was also experimentally studied using NMR spectroscopy by Schwalbe et al.16 Here, we analyzed equilibrium ensembles of Tau225−246 in its unmodified as well as post-translationally modified (phosphorylated and O-GlcNAcylated) forms.

Radius of Gyration and End-to-End Distances

To gain insight into the characteristics of the chain dimensions we calculate the distribution of the radius of gyration (Rg) for all systems as shown in Figure 2. For the unmodified peptides both the force fields predict similar behavior, albeit with significant differences. For TauC36m we observe a bimodal distribution with a peak around ~ 1 nm and ~ 1.5 nm respectively, while for Tauff99SBws we observe a prominent peak in the distribution around 1.35 nm which is intermediate to the peaks observed for TauC36m. For Tauff99SBws we also observe a slight shoulder around 1 nm. Upon examining the structures corresponding to these peaks we find that the lower peak corresponds to a loop conformation while the higher peak corresponds to an extended conformation. However, we note that the relative population distributions around these two peaks are reversed, with Amber ff99SBws favoring extended structures and CHARMM36m favoring the loop conformations. Upon phosphorylation at T231 and S235 (Tau2p), we observe that the Rg peak at 1.5nm is diminished with the systems favoring a loop conformation. However upon additional phosphorylation at S237 and S238 (Tau4p) we find a reappearance of the peak at 1.5 nm. The peak at 1 nm observed for the unmodified system is shifted to ~ 0.8 nm indicative of a further collapse in the geometry. Upon O-GlcNAcylation (TauO-GlcNAc) we observe a shift towards random coil structures with the distribution overlapping the Rg distribution of the unmodified peptide (TauC36m).

Figure 2.

Normalized radius of gyration (Rg) and end-to-end (E2E) distance distributions of Tauff99SBws, TauC36m, Tau2p, Tau4p, and TauO-GlcNAc. Peptide conformations corresponding to the peaks observed in the Rg distributions are also presented.

End-to-end (E2E) distance distributions, which provide insight into extended versus collapsed conformations, are also shown in Figure 2. The distributions follow a similar pattern as observed for Rg. For the simulation with the Amber ff99SBws force field, we observe a peak in the distribution around 3.5 nm, while for CHARMM36m we observe a peak around 1.5 nm followed by a broad distribution from 2nm - 6nm. Upon phosphorylation, we observe shifts towards collapsed conformations, with prominent peaks around 1.75 nm for both Tau2p and Tau4p. Upon O-GlcNAcylation we observe a broad distribution profile from 1nm – 6nm indicative of native-like random coil structures.

Secondary Structure Analysis

Gaining insights into the secondary structure preferences of the Tau225–246 region are important to understand the binding of Tau with MT and the influence of PTMs. NMR, as well as circular dichroism (CD) studies, show that Tau225–246 remains mostly disordered in solution. Some evidence of α-helix propensity has been observed in residues A239-R242 based on NMR chemical shift analysis. For this region, it has been observed that the fraction of α-helical content increases from 5% to 15% upon combined phosphorylation at T231 and S235 with additional phosphorylation at S237 and S238 resulting in a further increase in the helical content in the region. In contrast with PTM influenced changes in the downstream region the head region of Tau225–246 peptide (225KVAVVR230) remains largely unaffected by phosphorylation. This observation is of interest as 225KVAVVR230 has been implicated in MT binding.

To gain insight into the secondary structure preferences of Tau225–246 we performed secondary structure analysis to measure populations of common secondary structure elements using the DSSP algorithm.53 The algorithm classifies the secondary structure of peptide based on hydrogen bonding interactions between backbone carbonyl and NH groups. Helices are characterized by (i, i+3), (i, i+4), and (i, i+5) hydrogen bond contacts as 310-helix, α-helix, and π-helix respectively. The average fraction of secondary structures for each system is presented in Figure 3. The coil state is the dominant conformation for every peptide ensemble, with population in the range of (61% −73%). This is followed by the bend conformations (14% - 24%). This observation is in line with the NMR and CD studies which have observed Tau225–246 to remain predominantly disordered. Among the ordered structure, we find a slight preference for helical structures, α-helix (6%) and 310-helix (4%), exhibited by the Amber ff99SBws force field for the native peptide. While the CHARMM36m force field favors the β-sheet structure (6%) for the native peptide. This highlights slight differences arising due to the underlying force field. Upon PTM we observe slight shifts in the populations, but no drastic overall changes.

Figure 3.

DSSP based fraction of secondary structure for Tauff99SBws, TauC36m, Tau2p, Tau4p and TauOGlcNAc.

To further elaborate the picture, we also show per-residue secondary structure fractions in Figure S1 of the supporting information (SI) file. The residue-specific analysis allows us to identify regions that may adopt secondary structure elements. For the native peptide, we observe that the random coil state remains the most dominant conformation for both the Amber ff99SBws and CHARMM36m force fields, however, the tail regions of the peptide Tau235–245 shows a preference for α-helical conformation in the Amber ff99SBws simulations. For the CHARMM36m simulations, we observe a slight preference for β-sheet geometries in the head (Tau225–232) and tail (Tau240–245) regions. This is also reflected in the representative structures presented in Figure 2 corresponding to the Rg peaks (b) and (c) for Tauff99SBws and TauC36m simulations respectively. Upon PTM we observe a reduction in the preference of β-sheet structure for Tau2p and Tau4p, and a reappearance of the preference for TauO-GlcNAc. These conformational preferences are consistent with the Rg analysis, with TauO-GlcNAc exhibiting a similar distribution to the unmodified system TauC36m. We also observe that Tau4p exhibits a slight preference for α-helical conformation in the tail region Tau236–245.

The availability of experimental NMR coupling constants and chemical shifts for the native wild peptide (Tauwt) and the phosphorylated peptides, Tau2P and Tau4P allows us to analyze residue-specific structural features and compare the same with experimental observations.

1JCαHα coupling constants

Deviations in 1JCαHα coupling constants values from random coil values can provide useful insights into structural preferences. It has been found that residues in α-helical conformations exhibit positive deviations in the order of 4–5 Hz. The availability of experimental 1JCαHα coupling constants for Tau225–246, Tau2P, and Tau4P allows us to calculate the deviations in the coupling constants (Δ1JCαHα) between the phosphorylated systems and the native peptide. The Δ1JCαHα values provide insight into the structural changes upon PTM. Significant Δ1JCαHα values available for the head region (Tau225–231) and tail region (Tau237–245) from the experimental study by Schwalbe et al.16 are also presented in Figures 4a and 4b respectively. 1JCαHα coupling constants can also be calculated from ϕ and ψ dihedral data obtained from MD simulations using Equation 1 proposed by Vuister et. al.54

| (1) |

Figure 4:

Residue specific differences (Δ1JCαHα) between 1JCαHα couplings of Tau2p/TauC36m, Tau4p/TauC36m, and TauO-GlcNAc/TauC36m obtained from MD simulations. Δ1JCαHα values calculated from the experimental study by Schwalbe et al.16 for Tau2p and Tau4p are also presented for comparison. Δ1JCαHα values are presented for the (a) head region Tau225–231 and (b) tail region Tau237–245 of Tau225–246.

Where, A = 140.3, B = 1.4, C = −4.1, D = 2.0

The Δ1JCαHα values evaluated from MD simulations are also presented in Figure 4.

The experimental Δ1JCαHα profiles reveal that upon phosphorylation at T231 and S235 (Tau2P) the major changes with significant positive deviations (~1Hz) are observed for T231, S237 and K240 with minor positive deviations (0.5Hz) being observed for S238 and L243. These positive deviations are indicative of α-helical secondary structure preferences. The CHARMM C36m MD simulations capture the trend for the shift in the secondary structure preference at T231, S238, and L243, while we see no shift from the native conformations at S237 and K240. For Tau4P, which is phosphorylated at T231, S235, S237, and S238 we observe shifts towards α-helical conformations at T231 and nearly all the tail residues from S238-Q244. This is also captured in the simulations with all the residues in the tail region from S238-Q244 exhibiting positive Δ1JCαHα deviation. The only exception to the trend being the large negative deviation observed for L243. In figure 4 we also present Δ1JCαHα values from the native peptide upon O-GlcNAcylation obtained from MD simulation. We do not observe any significant deviations in the head region of the peptide. In the tail region, we observe significant positive deviations at A239, L234, and T245. These residues do not exhibit any significant changes for phosphorylation, clearly indicating differences upon phosphorylation versus O-GlcNAcylation.

Chemical shift analysis

From all the MD simulations we also calculated the Cα, Cβ, Hα secondary chemical shift values using the SPARTA+55 program. In Figure 5 we present the Δδ13Cα−Δδ13Cβ chemical shift data, which allows us to comment on regions of contiguous secondary structure. The Δδ13Cα and Δδ13Cβ values are calculated relative to random coil values extracted from Tamiola et al.56 Positive deviations from random coil values are indicative of α-helical propensity while negative values are indicative of β-sheets. From the experimental data we observe that there is a tendency for the head region of the peptide to adopt a β-sheet structure (Tau225–230), while the tail region adopts the α-helical conformation especially upon phosphorylation (Tau236–242). We also evaluate the secondary structure propensity score (SSP) using the chemical shift data. The same is compared with the experimental data and plotted in Figure 5. On comparing the TauC36m, Tau2P and Tau4P SSP scores we observe a shift towards α-helical preferences in the tail region, however, the absolute values are lower in comparison with the experimental data. Both the experimental and simulation data reveal that PTMs do not affect the 225KVAVVR230 region of the Tau peptide, which has been implicated in MT binding.

Figure 5:

Left Panel: Chemical shift calculated from simulated ensembles for unmodified Tau (ff99SBws and CHARMM36m) and Tau2p compared with experimental data (from Schwalbe et al.16). Right Panel: Secondary structure propensity (SSP) score for unmodified Tau (ff99SBws and CHARMM36m) and Tau2p and Tau4p calculated using the SSP program (Marsh et al.57) compared with the SSP score obtained from experimental data (from Schwalbe et al.16).

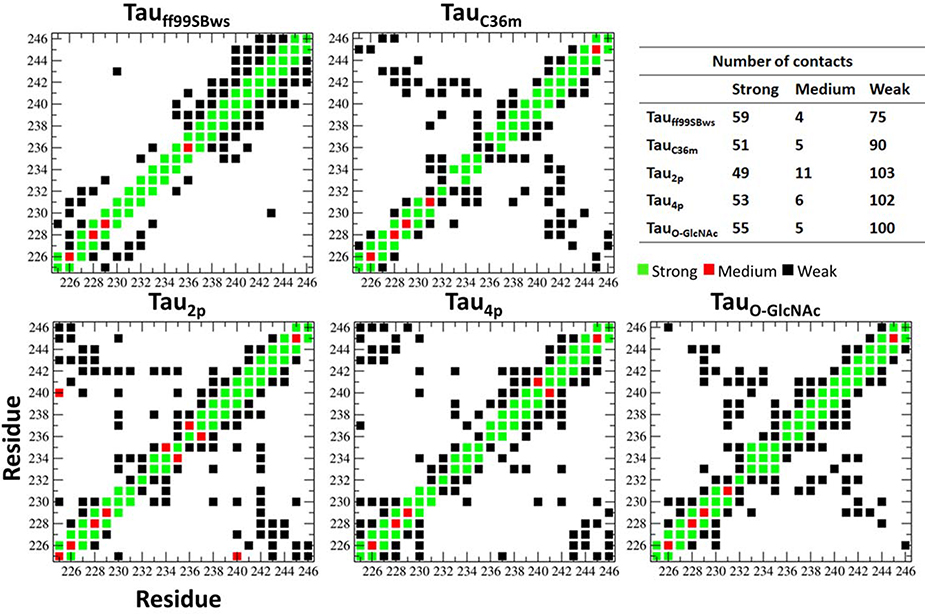

NOE Analysis

Nuclear Overhauser Effect (NOE) provides distance information from NMR experiments. NMR studies report an increase in the medium-range NOEs especially around residues near the phosphorylation sites. In Figure 6 we present the mean proton-proton distances between the various amino acids from MD simulations. The proton-proton distances are calculated as an average dHH = 〈r−6〉−1/6. The distances are classified as strong (0 Å < dHH < 2.7 Å), medium (2.7 Å < dHH < 3.5 Å) and weak (3.5 Å < dHH < 5.0 Å). Only the shortest dHH distance between the sets of amino acids is used to classify the interactions presented in the figure. From the Tauff99SBws simulations for the native peptide, we observe dHH i, i+2 and i, i+3 interactions between the amino acids in the tail region of the Tau peptide favoring an α-helical conformation. This pattern is not observed in the TauC36m simulations of the native peptide. For the simulations with the CHARMM C36m force fields, we observe weak interactions between the head and the tail regions of the peptide, indicated by the cross-peaks. These interactions are intensified upon phosphorylation and correspond to a bent/hairpin conformation for the peptide. Upon O-GlcNAcylation we observe an interaction pattern similar to the native peptide. As observed in the NMR experiments the interactions between the amino acids far removed from each other are pronounced for the residues near the phosphorylation sites. The NOE analysis reveals that there is are strong interactions between the head and the tail regions of Tau225–246 upon both phosphorylation and O-GlcNAcylation. However, the interaction pattern differs in the two PTMs. To gain further insight into these effects we investigate the system for residue-specific interactions, especially the formation of salt bridges and H-bonding interactions.

Figure 6:

Mean proton-proton distances between the various amino acids from MD simulations. The proton-proton distances are calculated as an average dHH = 〈r−6〉−1/6. The distances are classified as strong (0 Å < dHH < 2.7 Å), medium (2.7 Å < dHH < 3.5 Å) and weak (3.5 Å < dHH < 5.0 Å).

Salt bridges

Electrostatic interactions are known to play a crucial role in protein stability. Interactions between the charged phosphate group of phosphoserine/phosphothreonine and neighboring basic amino acids (Arginine (R), Lysine (K) and Histidine (H)) residues can enhance the stability of the protein. An example of such stabilization was reported by Errington et. al.58 who observed enhanced stabilization of α-helices by inducing a secondary salt-bridge sidechain interaction between phosphoserine and lysine placed in a i, i+4 arrangement. The tau peptide segment used in this study contains five basic epitopes (K225, R230, K234, K240, and R242) within the peptide. Site-directed mutagenesis study by Goode et al.19 indicated that K224, K225, and R230 are important for MT-binding and assembly. We investigate the ability of these basic residues to form salt bridges in Tau2p and Tau4p.

In Figure 7(a) and 7(b), we present the probability distribution of the possible salt-bridge interactions formed in both Tau2p and Tau4p respectively. For Tau2p we observe that both pT231 and pS235 interact with R230, K234, K240, and R242, forming stable salt-bridges. pS235 exhibits a preference for forming a very stable salt bridge with R242, which is present in the tail region of the peptide sequence. The formation of these stable salt bridges explains the off-diagonal interactions observed in the NOE NMR experiments. In Figure S2 of the SI file, we present the simulation time-series of the possible salt bridge interactions. We observe a concomitant formation of all the observed salt bridges.

Figure 7:

Normalized probability distribution of (a) salt-bridge interaction for phosphorylated T231 and S235 (Tau2p) and (b) T231, S235, S237 and S238 (Tau4p) with basic residues: K225, R230, K234, K240 and R242. (c) and (d) representative structures of the salt-bridges for Tau2p and Tau4p respectively, only representative portion of the peptide have been shown for clarity.

Contrary to Tau2p for Tau4p, we observe the formation of selective salt bridges. pT231 and pS235 selectively interact with R230 and K234, respectively. While both pS237 and pS238 interact favorably with R242. In addition to the strong salt bridge with R242, we also observe interactions between pS237 and R230, K234 and K240, while pS238 interacts with R230 and K240. In Figure S2 of the SI, we present the simulation time series for these salt bridge interactions. We observe differences between the interaction patterns between Tau2p for Tau4p. The salt bridges in Tau4p appear to be localized in comparison to Tau2p. In Figure 7 (c) and (d) we present the representative structures of the salt-bridges. We observe that the unique turn/bend conformation of the Tau225–246 peptide is brought about by the formation of the phosphate-lysine/arginine salt bridges. This highlights the structural influence of phosphorylation on Tau.

H-bonding

In the TauC36m and TauO-GlcNAc simulations we observe β-strand conformations in the head (226VAVVR230) and tail regions (241SRLQT245) of the Tau225–246 peptide segment. These β-strands arrange themselves into an anti-parallel β-sheet conformation via the formation of H-bonds between the backbone amide atoms of following pairs of amino acid pairs, A227-Q244, A227-L243, V229-S241, and R230-R242. The H-bond distributions corresponding to these pairs of H-bonds are presented in Figure 8a. For both the native (TauC36m) and the O-GlcNAcylated (TauO-GlcNAc) peptides the most significant H-bond pair is observed between R230 and R242. We note that both these arginine residues form salt bridges with the phosphate group in Tau2p and Tau4p. Thus, it is observed that the formation of the bend/loop conformation in the native and O-GlcNAcylated peptides is controlled by the formation of an anti-parallel β-sheet while the same in Tau2p and Tau4p is controlled by the formation of salt bridges. The involvement of R230 and R242 in the formation of salt bridges in Tau2p and Tau4p disrupts the formation of β-strands in these regions. We did not observe the formation of β-strands in Tauff99SBws simulations highlighting subtle differences between the Amber ff99SBws43 and CHARMM36m44 force fields. The observance of β-sheet structures especially in the N-terminal 225KVAVVRT231 motif is in line with the NMR studies which report an 18% probability of this motif adopting a β-sheet structure.17 In addition to the H-bonds involved in the formation of the anti-parallel β-sheet, we also observe the formation of a significant H-bond between the free hydroxyl (-CH2OH) group at C6 in GlcNAc with the backbone carbonyl oxygen of the adjacent amino acid (Figure 8b). O-GlcNAc at T231 interacts with the carbonyl oxygen of both P232 and R230, while the O-GlcNAc at S235 interacts only with the carbonyl oxygen of K234. These H-bonds control the orientation of the carbohydrate (GlcNAc) relative to the peptide backbone. In Figure S3 of the SI, we present the simulation time series corresponding to these H-bonding interactions. Moreover for Tau4p we also found presence of transient helix in the tail regions of the peptide (235–240). The presence of the transient helix is a direct result of formation of backbone carbonyl-amide i-i+4 hydrogen-bonds between S235 (O)…A239 (HN), S237 (O)…S241 (HN) and S238 (O)…R242 (HN) (Figure S4 of SI).

Figure 8:

(a) Main-chain carbonyl and amide hydrogen bond contact responsible for antiparallel β-sheet formation. (b) H-bond between the free hydroxyl (-CH2OH) group at C6 in GlcNAc with the backbone carbonyl oxygen of the adjacent amino acid. Representative structures have been presented to illustrate the H-bonding interactions.

Discussion

In this study, we have explored the conformational space of the Tau225–246 segment belonging to the proline-rich domain (P2) of the tau protein and its post-translationally modified forms using enhanced conformational sampling WTE metadynamics simulations. The proline-rich domain of tau serves as a linker between the N-terminal sequence and the tubulin-binding domains.6 Structurally the proline-rich domain has largely been characterized as being in a random coil state. Our simulations show that although the coiled state remains the most dominant conformation for the native peptide, we do observe a force field dependent influence on the short segments of the peptide. We observed a preference for α-helical conformation for the tail regions Tau235–245 in the Amber ff99SBws simulations, while for the CHARMM36m force field simulation we observed a preference for β-strand formation for both the head (Tau225–232) and tail (Tau240–245) regions of the peptide. The analysis of the radius of gyration (Rg) and end-to-end distances (Ree) reveal a preference for extended conformations for the native and O-GlcNAcylated peptides while phosphorylation induces collapsed bent conformations.

The secondary structure analysis revealed that PTMs (phosphorylation or O-GlcNAcylation) do not influence the conformation of the 225KVAVVR230 region, with no appreciable change in chemical shifts being observed in the simulations which agrees with the NMR derived chemical shifts data. However, closer inspection of the atomic level interactions reveals crucial binding interactions involving R230 in both phosphorylation and O-GlcNAcylation. Upon phosphorylation, R230 forms a stable salt bridge interaction with pT231 and pS235 in Tau2p, while in Tau4p the interaction is more selective to pT231. We note that this salt bridge does not influence the conformation of the preceding 225KVAVV229 region. Both these observations are in agreement with the NMR experiments by Schwalbe et. al. which alluded to the importance of the R230 forming a stable salt bridge with phosphorylated T231 in controlling the binding of Tau225–246 segment to MTs.16 However, upon O-GlcNAcylation R230 forms a intramolecular H-bond with R242 which results in the formation of an anti-parallel β-sheet between 226VAVVR230 and 241SRLQT245. Experimental studies on native Tau have found that 225KVAVVRT231 and 243LQTA246 show a strong affinity to bind to MTs. This observation has provided credence to the “Jaws” model of MT binding, wherein the flanking proline-rich regions in Tau are also involved in binding with MT in addition to the MT binding domain.

Thus we observe that our results indicate the unique “on-off” behavior of R230 and R242 in controlling the conformation of these short peptide sequences. In the native peptide as well as upon O-GlcNAcylation R230 and R242 are responsible for the stabilization of the antiparallel β-sheet structure, however, upon phosphorylation (Tau2p), both these Arginines are involved in salt bridges with pT231 and pS235 that results in a conformational change. Upon additional phosphorylation (Tau4p) at S237 and S238 we observe a change in the interaction pattern with the formation of selective salt-bridges. We note that while T231 and S235 phosphorylation sites have been established as a valid biochemical marker for AD diagnosis, the same is not true for S237 and S238. It could be that only selective sites are targeted for phosphorylation. One of the unique features of both T231 and S235 is the presence of a preceding basic amino acid R230 and K234 and being followed by a proline P232 and P236, ie 230RTP232 and 234KSP236. The R230-T231 bond is also targeted by calpain and caspase family of proteases which results in 20–22 kDa Tau fragments which have been observed in the patients with AD, highlighting the importance of this region of the Tau peptide and T231. 59,60

Our detailed investigation into the influence of phosphorylation on the conformational preferences of Tau could also provide insights for the development of phospho-specific antibodies. Shih et. al. reported the development of one of the first phospho-specific antibody which could detect the pathological form of Tau in patients with AD. 61 The study specifically targeted the pT231 and pS235 phosphorylation sites. To gain insight into the specificity they also reported the crystal structure of a Fab fragment co-crystallized with 224KKVAVVR(pT231)PPK234 at a resolution of 1.9 Å. In the crystal structure, six residues 224KKVAVVR(pT231) were found to directly interact with the Fab fragment, with the remainder of the structure adopting a random coil conformation. A significant salt bridge was observed between the Arginine side-chain of Fab (R53) with the pT231 phosphate. Additionally, a water-mediated interaction was observed between pT231 and the side chain of R230. These observations highlight the importance of Phosphate-Lysine interactions in antibody recognition.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we find that both phosphorylation and O-GlcNAcylation influence the secondary structure of the Tau peptide segment. However, different effects govern the conformational preferences. The conformational transition upon phosphorylation is a direct influence of the formation of strong salt bridges with nearby lysine and arginine. For O-GlcNAcylation we did not find a direct influence on the conformational preference, however, the formation of strong H-bonds between the free –CH2OH group and backbone amide carbonyl’s does not rule out the perturbative influence of O-GlcNAcylation. It is evident the phosphorylation induces a strong structural transition with Tau225–246 favoring a bent conformation due to the formation of strong salt-bridges. These results are also in agreement with the NMR studies by Brister et. al. who observed opposing structural and functional effects for various short segments of the Tau protein.6 In terms of composition, the Tau peptide contains 3% Arginine sites and 10% Lysine sites, which can interact with phosphorylated threonine/serine. Additional simulation studies on longer constructs of the Tau peptide could provide significant information on the conformational preferences of native Tau and Tau fragments observed in Tauopathies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

SSM thanks Department of Science and Technology, INDIA for INSPIRE fellowship (IFA-13 CH-104) and Department of Biotechnology, INDIA for Research grant (BT/PR15143/BID/7/553/2015). LR thanks University Grants Commission, INDIA for Rajiv Gandhi National Fellowship (RGNF-2015-17-SC-DEL-15206). J.M. acknowledges funding from the National Institutes of Health through Award Nos. R01GM120537 and R01GM118530. Use of the high-performance computing capabilities of the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), which is supported by the National Science Foundation, project no. TG-MCB120014 is also gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Residue specific comparative DSSP analysis, Simulation time-series of the possible salt bridge interactions observed in Tau2p and Tau4p, Simulation time-series of the possible H-bonding interactions observed in TauO-GlcNAc.

References

- (1).Hunter T The age of crosstalk: phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and beyond. Mol. Cell. 2007, 28, 730–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Johnson LN; Lewis RJ Structural basis for control by phosphorylation. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 2209–2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Hart GW Dynamic O-linked glycosylation of nuclear and cytoskeletal proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1997, 66, 315–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Hart GW; Akimoto Y: The O-GlcNAc modification In Essentials of Glycobiology. 2nd edition; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Comer FI; Hart GW O-Glycosylation of Nuclear and Cytosolic Proteins Dynamic Interplay Between O-GlcNAc and O-Phosphate. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 29179–29182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Brister MA; Pandey AK; Bielska AA; Zondlo NJ OGlcNAcylation and phosphorylation have opposing structural effects in tau: phosphothreonine induces particular conformational order. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 3803–3816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Medina L; Grove K; Haltiwanger RS SV40 large T antigen is modified with O-linked N-acetylglucosamine but not with other forms of glycosylation. Glycobiology 1998, 8, 383–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Hart GW; Slawson C; Ramirez-Correa G; Lagerlof O Cross talk between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation: roles in signaling, transcription, and chronic disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2011, 80, 825–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Liu F; Iqbal K; Grundke-Iqbal I; Hart GW; Gong C-X O-GlcNAcylation regulates phosphorylation of tau: a mechanism involved in Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004, 101, 10804–10809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Copeland RJ; Bullen JW; Hart GW Cross-talk between GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation: roles in insulin resistance and glucose toxicity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2008, 295, E17–E28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Weingarten MD; Lockwood AH; Hwo S-Y; Kirschner MW A protein factor essential for microtubule assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1975, 72, 1858–1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Cleveland DW; Fischer SG; Kirschner MW; Laemmli UK Peptide mapping by limited proteolysis in sodium dodecyl sulfate and analysis by gel electrophoresis. J. Biol. Chem. 1977, 252, 1102–1106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Lin YT; Cheng JT; Liang LC; Ko CY; Lo YK; Lu PJ The binding and phosphorylation of Thr231 is critical for Tau’s hyperphosphorylation and functional regulation by glycogen synthase kinase 3β. J. Neurochem. 2007, 103, 802–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Kosik KS The molecular and cellular biology of tau. Brain Pathology 1993, 3, 39–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Kadavath H; Jaremko M; Jaremko Ł; Biernat J; Mandelkow E; Zweckstetter M Folding of the tau protein on microtubules. Angew. Chem. 2015, 54, 10347–10351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Schwalbe M; Kadavath H; Biernat J; Ozenne V; Blackledge M; Mandelkow E; Zweckstetter M Structural impact of tau phosphorylation at threonine 231. Structure 2015, 23, 1448–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Mukrasch MD; Bibow S; Korukottu J; Jeganathan S; Biernat J; Griesinger C; Mandelkow E; Zweckstetter M Structural polymorphism of 441-residue tau at single residue resolution. PLoS Biology 2009, 7, e1000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Goode BL; Feinstein SC Identification of a novel microtubule binding and assembly domain in the developmentally regulated inter-repeat region of tau. J. Cell Biol. 1994, 124, 769–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Goode BL; Denis PE; Panda D; Radeke MJ; Miller HP; Wilson L; Feinstein S Functional interactions between the proline-rich and repeat regions of tau enhance microtubule binding and assembly. Molecular biology of the cell 1997, 8, 353–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Martin L; Latypova X; Terro F Post-translational modifications of tau protein: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem. Int. 2011, 58, 458–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Buée L; Bussière T; Buée-Scherrer V; Delacourte A; Hof PR Tau protein isoforms, phosphorylation and role in neurodegenerative disorders. Brain Res. Rev. 2000, 33, 95–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Sergeant N; Bretteville A; Hamdane M; Caillet-Boudin M-L; Grognet P; Bombois S; Blum D; Delacourte A; Pasquier F; Vanmechelen E Biochemistry of Tau in Alzheimer’s disease and related neurological disorders. Expert review of proteomics 2008, 5, 207–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Hanger DP; Anderton BH; Noble W Tau phosphorylation: the therapeutic challenge for neurodegenerative disease. Trends in molecular medicine 2009, 15, 112–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Sergeant N; Delacourte A; Buée L Tau protein as a differential biomarker of tauopathies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease 2005, 1739, 179–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Alonso A.d. C.; Zaidi T; Grundke-Iqbal I; Iqbal K Role of abnormally phosphorylated tau in the breakdown of microtubules in Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994, 91, 5562–5566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Kolarova M; García-Sierra F; Bartos A; Ricny J; Ripova D Structure and pathology of tau protein in Alzheimer disease. International journal of Alzheimer’s disease 2012, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Kiris E; Ventimiglia D; Sargin ME; Gaylord MR; Altinok A; Rose K; Manjunath B; Jordan MA; Wilson L; Feinstein SC Combinatorial Tau Pseudophosphorylation Markedly Different Regulatory Effects on Mirotubule Assembly and Dynamic Instability than the Sum of the Individual Parts. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 14257–14270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Liu F; Li B; Tung EJ; Grundke-Iqbal I; Iqbal K; Gong CX Site-specific effects of tau phosphorylation on its microtubule assembly activity and self-aggregation. Eur. J. Neurosci 2007, 26, 3429–3436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Sengupta A; Kabat J; Novak M; Wu Q; Grundke-Iqbal I; Iqbal K Phosphorylation of tau at both Thr 231 and Ser 262 is required for maximal inhibition of its binding to microtubules. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1998, 357, 299–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Amniai L; Barbier P; Sillen A; Wieruszeski J-M; Peyrot V; Lippens G; Landrieu I Alzheimer disease specific phosphoepitopes of Tau interfere with assembly of tubulin but not binding to microtubules. FASEB J. 2009, 23, 1146–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Daly NL; Hoffmann R; Otvos L; Craik DJ Role of Phosphorylation in the Conformation of τ Peptides Implicated in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 9039–9046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Hoffmann R; Lee VM-Y; Leight S; Varga I; Otvos L Unique Alzheimer’s disease paired helical filament specific epitopes involve double phosphorylation at specific sites. Biochemistry 1997, 36, 8114–8124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Brici D; Götz J; Nisbet RM A novel antibody targeting tau phosphorylated at serine 235 detects neurofibrillary tangles. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 61, 899–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Wang J-Z; Grundke-Iqbal I; Iqbal K Glycosylation of microtubule–associated protein tau: An abnormal posttranslational modification in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Med. 1996, 2, 871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Takahashi M; Tsujioka Y; Yamada T; Tsuboi Y; Okada H; Yamamoto T; Liposits Z Glycosylation of microtubule-associated protein tau in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Acta Neuropathologica 1999, 97, 635–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Lefebvre T; Ferreira S; Dupont-Wallois L; Bussiere T; Dupire M-J; Delacourte A; Michalski J-C; Caillet-Boudin M-L Evidence of a balance between phosphorylation and O-GlcNAc glycosylation of Tau proteins—a role in nuclear localization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-General Subjects 2003, 1619, 167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Liu F; Shi J; Tanimukai H; Gu J; Gu J; Grundke-Iqbal I; Iqbal K; Gong C-X Reduced O-GlcNAcylation links lower brain glucose metabolism and tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2009, 132, 1820–1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Robertson LA; Moya KL; Breen KC The potential role of tau protein O-glycosylation in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis 2004, 6, 489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Jeganathan S; von Bergen M; Brutlach H; Steinhoff H-J; Mandelkow E Global hairpin folding of tau in solution. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 2283–2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Gamblin TC Potential structure/function relationships of predicted secondary structural elements of tau. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Molecular Basis of Disease 2005, 1739, 140–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Gustke N; Trinczek B; Biernat J; Mandelkow E-M; Mandelkow E Domains of tau protein and interactions with microtubules. Biochemistry 1994, 33, 9511–9522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Verdecia MA; Bowman ME; Lu KP; Hunter T; Noel JP Structural basis for phosphoserine-proline recognition by group IV WW domains. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2000, 7, 639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Best RB; Zheng W; Mittal J Balanced protein–water interactions improve properties of disordered proteins and non-specific protein association. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2014, 10, 5113–5124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Huang J; Rauscher S; Nawrocki G; Ran T; Feig M; de Groot BL; Grubmüller H; MacKerell AD Jr CHARMM36m: an improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Goedert M; Spillantini M; Jakes R; Rutherford D; Crowther R Multiple isoforms of human microtubule-associated protein tau: sequences and localization in neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 1989, 3, 519–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Abascal JL; Vega C A general purpose model for the condensed phases of water: TIP4P/2005. J. Chem. Phys. 2005, 123, 234505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Jorgensen WL; Chandrasekhar J; Madura JD; Impey RW; Klein ML Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 79, 926–935. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Guvench O; Mallajosyula SS; Raman EP; Hatcher E; Vanommeslaeghe K; Foster TJ; Jamison FW; MacKerell AD Jr CHARMM additive all-atom force field for carbohydrate derivatives and its utility in polysaccharide and carbohydrate–protein modeling. J. Chem. Theory Comput 2011, 7, 3162–3180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Tribello GA; Bonomi M; Branduardi D; Camilloni C; Bussi G PLUMED 2: New feathers for an old bird. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2014, 185, 604–613. [Google Scholar]

- (50).Steinbach PJ; Brooks BR New spherical-cutoff methods for long-range forces in macromolecular simulation. J. Comput. Chem. 1994, 15, 667–683. [Google Scholar]

- (51).Darden T; York D; Pedersen L Particle mesh Ewald: An N⋅ log (N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys 1993, 98, 10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- (52).Abraham MJ; Murtola T; Schulz R; Páll S; Smith JC; Hess B; Lindahl E GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- (53).Joosten RP; Te Beek TA; Krieger E; Hekkelman ML; Hooft RW; Schneider R; Sander C; Vriend G A series of PDB related databases for everyday needs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 39, D411–D419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Vuister GW; Delaglio F; Bax A The use of 1 J CαHα coupling constants as a probe for protein backbone conformation. J. Biomol.NMR 1993, 3, 67–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Shen Y; Bax A SPARTA+: a modest improvement in empirical NMR chemical shift prediction by means of an artificial neural network. J. Biomol.NMR 2010, 48, 13–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Tamiola K; Acar B; Mulder FA Sequence-specific random coil chemical shifts of intrinsically disordered proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 18000–18003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Marsh JA; Singh VK; Jia Z; Forman-Kay JD Sensitivity of secondary structure propensities to sequence differences between α-and γ-synuclein: Implications for fibrillation. Protein Sci. 2006, 15, 2795–2804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Errington N; Doig AJ A phosphoserine− lysine salt bridge within an α-helical peptide, the strongest α-helix side-chain interaction measured to date. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 7553–7558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Amadoro G; Ciotti MT; Costanzi M; Cestari V; Calissano P; Canu N NMDA receptor mediates tau-induced neurotoxicity by calpain and ERK/MAPK activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006, 103, 2892–2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Amadoro G; Corsetti V; Atlante A; Florenzano F; Capsoni S; Bussani R; Mercanti D; Calissano P Interaction between NH2-tau fragment and Aβ in Alzheimer’s disease mitochondria contributes to the synaptic deterioration. Neurobiology of Aging 2012, 33, 833.e831–833.e825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Shih HH; Tu C; Cao W; Klein A; Ramsey R; Fennell BJ; Lambert M; Ní Shúilleabháin D; Autin B; Kouranova E; Laxmanan S; Braithwaite S; Wu L; Ait-Zahra M; Milici AJ; Dumin JA; LaVallie ER; Arai M; Corcoran C; Paulsen JE; Gill D; Cunningham O; Bard J; Mosyak L; Finlay WJJ An ultra-specific avian antibody to phosphorylated tau protein reveals a unique mechanism for phosphoepitope recognition. J Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 44425–44434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.