Abstract

We previously proposed that three metacognitive processes – meta-awareness, disidentification from internal experience, and reduced reactivity to thought content – together constitute decentering. We review emerging methods to study these metacognitive processes and the novel insights they provide regarding the nature and salutary function(s) of decentering. Specifically, we review novel psychometric studies of self-report scales of decentering, as well as studies using intensive experience sampling, novel behavioral assessments, and experimental micro-interventions designed to target the metacognitive processes. Findings support the theorized inter-relations of the metacognitive processes, help to elucidate the pathways through which they may contribute to mental health, and provide preliminary evidence of their salutary roles as mechanisms of action in mindfulness-based interventions.

Keywords: Behavioral Assessment, Cognitive Defusion, Decentering, Experience Sampling, Identification, Meta-Awareness, Metacognitive Processes, Micro-Intervention, Mindfulness, Reactivity, Self-Distanced Perspective

Introduction

Decentering reflects the capacity to shift experiential perspective – from within one’s subjective experience, onto that experience. It is theorized to function as a malleable causal mediating process underlying salutary effects of various psychological interventions [1–5]. Decentering has been a particular focus of mindfulness mechanisms research for over two decades due to its explicit therapeutic role in Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy [6] as well as its theorized salutary and curative role as a mediating mechanism of action across a variety of MBIs [7–12].

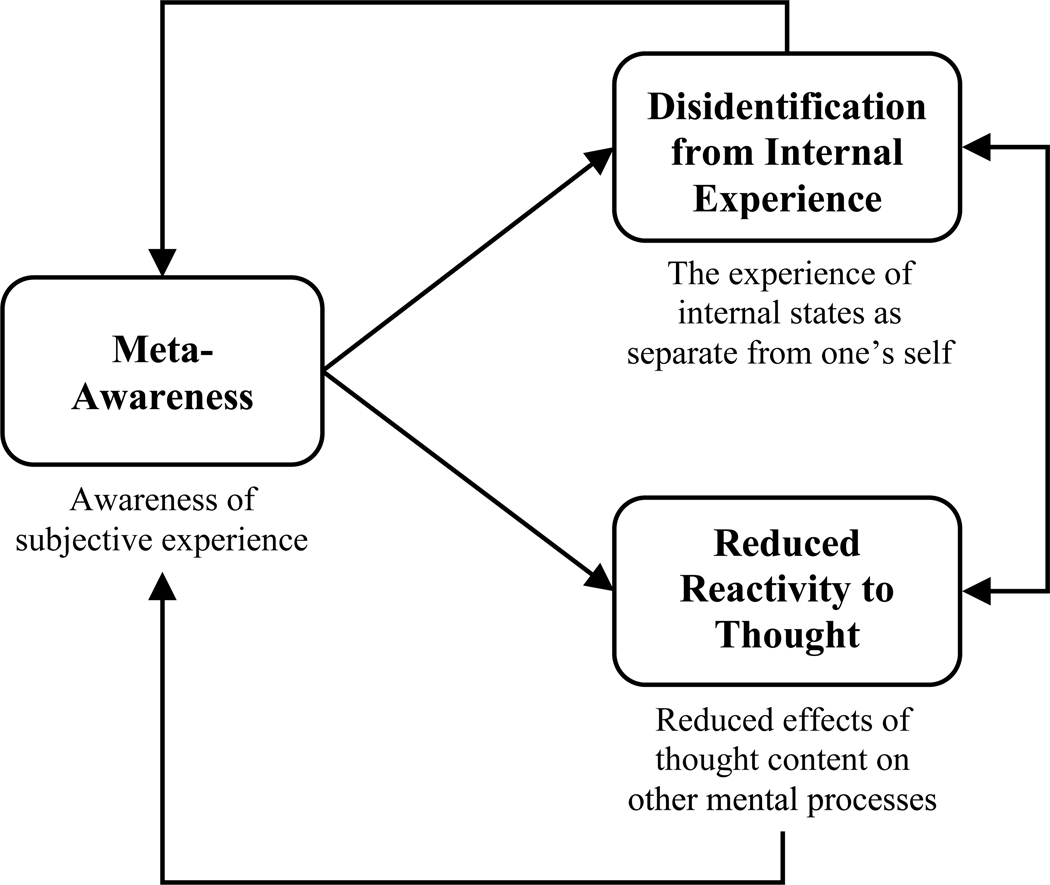

In the hopes of better understanding and advancing the study of decentering, we proposed the Metacognitive Processes Model of Decentering [7]. Through this model, we proposed that three interrelated metacognitive processes – Meta-Awareness, Disidentification from Internal Experience, and Reduced Reactivity to Thought Content – together constitute decentering (see Figure 1) [7]. Meta-awareness is awareness of subjective experience (i.e., awareness of the processes occurring in consciousness such as thinking, feeling, sensing) [10,13]. It is distinguished from awareness of the contents of thoughts (i.e., mental representations) without concurrent meta-awareness of the thinking process. For example, a person may be aware of the contents of his worried thoughts (e.g., “I will get injured”) or a person may be meta-aware of his worrying as a thought processes (e.g., “I am having an apprehensive thought”). Disidentification from internal experience is the experience of internal states as separate from one’s self. For example, a person may identify with the experience of sadness (e.g., “I am sad”) or she/he may experience that sadness but without identification (e.g., “I am having a feeling of sadness”). Reduced reactivity to thought content refers to the reduced effects of thought content on other mental processes (e.g., attention, emotion, cognitive elaboration, motivation, motor planning) and is expressed in a number of ways such as reduced belief in thought content. For example, low levels of reactivity to the thought “I am a bad mother” may not trigger the same degree of self-critical rumination and feelings of guilt or shame as elevated reactivity to this type of thought content.

Figure 1.

The Metacognitive Processes Model of Decentering

Note. Meta-awareness is theorized to engender disidentification from internal experience and reduced reactivity to thought content, which in turn affect one another, and feedback to reinforce meta-awareness. Figure adapted from [7].

In our previous paper on the metacognitive processes model of decentering we described how these metacognitive processes may affect on one another based on theory and a growing body of findings (see Figure 1) [7]. We proposed that disidentification from internal experience and reduced-reactivity to thought content are initiated by meta-awareness. Meta-awareness may engender disidentification from internal experience because observing subjective experience creates a distinction (i.e., disidentification) between the observing self or consciousness, and the observed subjective experience. Likewise, meta-awareness may engender reduced-reactivity to thought content by disengaging attention from thought content to present moment experiences. Furthermore, meta-awareness of thinking processes may lead to construal of thought content as an interpreted representation, rather than a factual representation, of present/past/future situations and experiences. In turn, disidentification from experience and reduced-reactivity to thought content affect one another, and likely feedback to further potentiate meta-awareness (see Figure 1). Notably, meta-awareness is fundamental to mindful awareness [12,14,15]. We thus proposed that it is through meta-awareness that mindfulness practices may engender disidentification from internal experience and reduced-reactivity to thought content and, thereby, decentering.

Furthermore, we reviewed extant research on decentering and related constructs through the prism of the proposed metacognitive processes model (see Table 1) [7]. Of particular relevance to this paper, we concluded that extant decentering science was limited primarily by reliance on empirically modest methods (e.g., retrospective self-report, cross-section designs). The development of methods to more rigorously and precisely measure and experimentally target the specified metacognitive processes of decentering could significantly contribute to advancing our understanding of the nature and function of decentering, its roles in mental health and as a mechanism of action in MBIs; and in turn, our capacity to more optimally therapeutically target decentering to promote mental health.

Table 1.

Proposed Metacognitive Processes Across Decentering-Related Constructs

| Decentering-Related Constructs | Metacognitive Processes | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Meta-Awareness | Disidentification from Internal Experience | Reduced Reactivity to Thought Content | |

| Decentering [47] | x | x | x |

| Metacognitive Awareness [3] | x | x | x |

| Cognitive Distancing [1] | x | x | x |

| Metacognitive Mode [4] | x | x | x |

| Detached Mindfulness [48] | x | x | x |

| Reperceiving [11] | x | x | |

| Mindfulness [49] | x | ||

| Cognitive Defusion [2] | x | ||

| Self-as-Context [2] | x | ||

| Self-Distanced Perspective [50] | x | ||

| Dereification [51] | x | ||

Note. An X denotes the metacognitive process(es) proposed to sub-serve various decenter-related constructs. Table adapted from [7].

Accordingly, in the present commentary, we briefly review recent methodological advances in the science of decentering and related constructs and, in turn, the substantive insights that they are beginning to provide with respect to decentering, mental health, and mindfulness mechanisms research. Specifically, we review the following: (I) recent psychometric studies of self-report scales of decentering and related constructs, (II) intensive experience sampling study of the metacognitive processes of decentering, (III) behavioral assessment studies of the metacognitive processes, and (IV) research using experimental micro-interventions designed to target the metacognitive processes.

I. Self-Report Scales: Measurement Structure

At least seven published self-report scales of decentering and related constructs include items reflecting one or more of the metacognitive processes [16–24]. Recently, two independent psychometric studies focused on better understanding the construct validity and latent dimensional structure of these scales [16,17]. Despite methodological differences, both studies reported a two-factor solution that was conceptually and empirically similar. One factor reflecting disidentified and non-reactive meta-awareness of experience – labeled “Intentional Decentered Perspective”[16] and “Observer Perspective”[17]. A second factor reflecting reduced reactivity to thought content – labeled “Automatic Reactivity to Thought Content” [16] and “Reduced Struggle with Inner Experience” [17].

Findings from these psychometric studies [16,17] have numerous implications for self-report study of decentering. First, no single or group of existing self-report scales assesses all three proposed metacognitive processes comprehensively. Indeed, measures to-date were not grounded theoretically in this model and the metacognitive processes perspective on decentering. Second, extant self-report scales of decentering and related constructs are not interchangeable and differ in their psychometric performance and the process(es) they measure (for scales with better psychometrics performance see [16,17]). Third, several measures demonstrated low internal consistencies, and a large number of items from studied measures did not load on observed factors. Consistent with the metacognitive processes model and conceptualization of decentering, items reflecting self-compassion or acceptance, were empirically excluded from the final factor solutions. Accordingly, further self-report scale development is needed and may be guided by the metacognitive processes model.

II. Intensive Experience Sampling

Experience sampling (ES) methods help to address key limitations of traditional retrospective self-report assessment of subjective experience (e.g., retrospective recall bias). ES methods entail repeated sampling of subjects’ current behaviors, experiences, and contexts in real time, in subjects’ real-world environment, providing measurement data with high temporal and contextual resolution [25]. Accordingly, Shoham et al (2017) conducted intensive ES of meta-awareness (mindfulness), disidentification from internal experience, reduced reactivity to thought content, among other processes, over the course of an MBI [26]. Findings indicate that in daily living and meditative states, participants displayed cumulative elevation in all three metacognitive processes over the course of the intervention. Moreover, as predicted by the metacognitive processes model, the greater the degree to which participants were meta-aware of their experience, the more disidentified they were from that experience and the less reactive they were to their thought content. Although these effects were observed in daily living, they were significantly stronger in experience samples during mindfulness meditation practice. Importantly, in line with the metacognitive processes model, greater levels of meta-awareness were related to greater positive emotional valence and reduced emotional arousal. Moreover, to study reactivity to negative thought content, Shoham et al (2018) used ES to present participants with their own distressing personal negative self-referential thought content (e.g., “I’m a failure”; individual thought content collected pre-intervention) [27]. As predicted by the metacognitive processes model, mindfulness meditation, in which participants intentionally cultivated meta-awareness, was associated with reduced reactivity to negative self-referential thought content, in the form of greater willingness to experience these thoughts. This finding may be noteworthy as the degree of distress elicited by the thoughts remained elevated and unchanged over the course of the intervention.

III. Behavioral Assessment

Meta-Awareness

Several behavioral assessment methods have been developed to study meta-awareness. For a review of extant behavioral measures of mindfulness and meta-awareness see Hadash and Bernstein in this issue [28]. Here, we focus on findings from studies utilizing three behavioral methods relevant for the metacognitive processes model of decentering. One method entails probe- and self-caught real time ES during performance of cognitive tasks (e.g., go/no-go task) and during mindfulness meditation to assess meta-awareness of mind wandering [13,28–30]. Interestingly, mind wandering with and without meta-awareness, measured using these methods, are differentiated processes with distinct neural and cognitive correlates [13, 30–32]. Moreover, findings indicate that meta-awareness of mind wandering may reduce the occurrence of mind wandering [13], and meta-awareness during mind wandering may buffer the detrimental effects of mind wandering on attentional/executive dysregulation (e.g., response inhibition, capacity to construct mental models) [33]. Of relevance to the metacognitive processes model of decentering, the latter effects and set of findings may reflect the theorized effects of meta-awareness on reduced reactivity to thought content (i.e., reduced reactivity to the content of mind wandering).

A second approach to measure meta-awareness applies the first and third person correspondence method [28]. This approach entails comparison of subjective (i.e., first-person) reports of present moment experience with objective (i.e., third-person; e.g., physiological, behavioral) markers, or experimental manipulations, of that experience. This method is used to measure accurate meta-awareness of subtle changes in interoceptive and mental experience (see also interoceptive sensitivity/accuracy tasks [34,35]). Based on this methodology, Ruimi et al (2018) developed the Probe-Caught Meta-Awareness of Bias task, to quantify accurate meta-awareness of biased or dysregulated attention [36]. Probe-caught ES are applied to estimate real-time subjective reports of biased attention (i.e., first person reports), concurrent with the objective trial-level expressions of biased attention in a probe detection or similar task (i.e., third-person performance data). A signal detection methodology is applied to quantify accurate detection or meta-awareness of biased attention through agreement between subjective ES reports of biased attention with objective performance data. Ruimi et al found that momentary micro-expressions of biased attention without meta-awareness were more likely followed by attentional dysregulation; whereas momentary micro-expressions of biased attention with accurate meta-awareness were more likely followed by more balanced attentional expression or greater attentional regulation. Consistent with the metacognitive processes model, findings suggest that accurate meta-awareness effects attentional regulation, and important processes related to mental health.

A third approach to measure and study meta-awareness is implemented in the Mindful Awareness Task – a behavioral measure of meta-awareness during mindfulness meditation (see Hadash & Bernstein in this issue for details) [28]. In the MAT participants provide real-time self-caught reports (behavioral markers) of their meta-awareness during mindfulness meditation, by verbally stating a label describing each experience they notice (e.g., “hearing”, “thinking”) and by pressing a button when they notice their inhalation and exhalation. Meta-awareness of different types of experience (e.g., bodily sensations, mental events, pleasant or unpleasant experience) is measured via manualized qualitative coding of the content of participant’s verbal labels. In addition, the precise timing and order of all reports of mindful awareness (i.e., labels and button presses) are analyzed to compute indices related to the time-course of meta-awareness (e.g., latency to re-engagement in meta-awareness after mind wandering). Findings suggest that meta-awareness of different objects of experience during mindfulness meditation are differentially associated with mental health outcomes (e.g., meta-awareness of mental experience predicted higher levels of self-regulation, and meta-awareness of pleasant experience predicted positive affect). Moreover, faster re-engagement in meta-awareness following the onset of mind wandering predicted higher levels of self-regulation and lower levels of depression symptoms (Y Hadash, L Ruimi, O Harel, & A Bernstein, presentation in International Symposium for Contemplative Research, Phoenix AZ, November 2018).

Disidentification from Internal Experience

To study disidentification from internal experience (and related processes), Hadash, Plonsker, Vago and Bernstein (2016) developed the Single Experience & Self-Implicit Association Test [37,38]. This paradigm involves the experimental elicitation of a subjective experience (e.g., using videos and audio) and the concurrent measurement of participant’s cognitive association between self and the elicited subjective experience by means of an Implicit Association Test. Hadash et al tested one variant of this paradigm to measure individual differences in identification with and negative judgments of fear [37]. Consistent with the metacognitive processes model of decentering, they found that lower levels of (implicit) identification with fear were associated with greater levels of self-reported meta-awareness of emotions and trait decentering.

Reduced Reactivity to Thought Content

To measure reactivity to one’s own thought content, Amir, Ruimi and Bernstein (Amir, Ruimi, & Bernstein, submitted; I Amir, L Ruimi, & A Bernstein, presentation in International Conference on Mindfulness, Amsterdam, July 2018) developed the Simulated Thoughts Paradigm. To do so, the Simulated Thoughts Paradigm presents idiographic negative or neutral self-referential thought content via audio stimuli in the participant’s own (recorded) voice, to experimentally elicit an experience that feels like thinking one’s thoughts. This paradigm was implemented during an external (visual) Digit Categorization Task (odd vs. even) [39]. The task required participants to, repeatedly, disengage internal attention from the experimentally controlled simulated thought stimuli so that they could allocate that attention externally to the digit categorization task and stimulus. Using the Simulated Thoughts Paradigm, Amir et al found that ES negative emotional reactivity to idiographic negative self-referential thought content predicted difficulty disengaging internal attention from their negative self-referential thoughts to the external task; this difficulty disengaging attention predicted degree of self-reported negative repetitive thinking and related measures of cognitive vulnerability; which, in turn, predicted degree of depression and anxiety symptom levels. These findings are consistent with the metacognitive processes model of decentering that implicates emotional and attentional reactivity to thought content in mental health problems, and helps specify pathways through which reduced reactivity to thought content may affect mental health.

IV. Experimental Micro-Interventions

Micro-interventions or brief experimental methods designed to target and manipulate the metacognitive processes can help test causal relations between the processes and between the processes and mental health outcomes. Such methods may also have therapeutic implications and applications. One recent micro-intervention approach – Attentional Feedback Awareness & Control Training – delivers real-time feedback on moment-to-moment (i.e., trial-level) expressions of attention to train meta-awareness of biased or dysregulated attention and thereby self-regulatory control of (biased) attention [40]. Randomized controlled experimental studies found that, among anxious adults, real-time feedback was associated with improved regulation of covert (reaction time) attentional processing of threatening information as well as reduced emotional reactivity to, and facilitated recovery following, an anxiogenic stressor [40,41]. More recently, Ruimi, Hendren, Amir, Zvielli, and Bernstein (L Ruimi et al., under review) found that real-time feedback on attention led to elevated meta-awareness of biased attention (via Probe-Caught Meta-Awareness of Bias methodology; see Section III above), greater regulation of overt (eye-movement) attentional processing of threat, and that greater levels of meta-awareness following training predicted greater capacity to regulate attention. Consistent with the metacognitive processes model, findings provide preliminary experimental evidence that meta-awareness contributes to attentional and emotional regulatory processes implicated in mental health.

A second recent micro-intervention approach used language-based, first- and third-person self-talk to experimentally manipulate self-distancing, defined in the metacognitive processes model as disidentification from internal experience [42,43]. Building on seminal imaginal self-distancing and self-immersion experimental micro-intervention research by Kross and colleagues [44], participants were instructed to use third-person (i.e., first name) vs. first-person (i.e., I) in written self-talk regarding a particular topic (e.g., worries about Ebola). Consistent with the metacognitive processes model, Kross et al (2017) found that, among participants worried about Ebola, disidentification from internal experience elicited via third-person self-talk about Ebola (vs. first-person) was associated with more rational thought about Ebola, reduced Ebola worry, and reduced perceived risk [42].

Conclusions and Future Directions

We reviewed studies adopting novel methods to study decentering. These include psychometric studies of self-report scales, intensive experience sampling, behavioral assessments, and experimental micro-interventions. These studies and methods are beginning to provide support for the metacognitive processes model of decentering, including: (1) the theorized inter-relations between meta-awareness, disidentification from internal experience, and reduced reactivity to thought content; (2) the pathways through which these metacognitive processes contribute to mental health; and (3) the theorized salutary role of these processes as mechanisms of action in MBIs. We also identified a number of methodological limitations of extant decentering research, including: (1) the limited scale and scope of decentering research to-date using emerging behavioral methods (cf. self-report measurement); (2) the limited capacity of extant self-report scales to measure the theorized metacognitive processes of decentering; and (3) the relatively limited number of tools to measure and study disidentification from internal experience and reduced reactivity to thought content, in contrast to the growing number of tools to measure and study meta-awareness.

We foresee that research developing and utilizing such methods to study decentering may also have promising translational implications. By advancing our understanding, capacity to measure, and to experimentally manipulate the metacognitive processes that may subserve decentering, we may be better able to design and deliver therapeutic interventions (e.g., MBIs) targeting these processes. Such efforts may be useful to improve the efficacy of interventions designed to reduce psychological vulnerability and improve mental health by means of cultivating decentering. For example, it may be useful to apply novel micro-intervention therapeutic technologies targeting individual metacognitive processes, and to deliver these micro-interventions in the moments and contexts in which a person may be most likely to benefit and learn from them. Such a therapeutic approach may, for example, be well-suited for Sequential Multiple Assignment Randomized Trial and Just-In-Time Adaptive Intervention designs used effectively to-date for process-focused micro-interventions targeting health behaviors [45,46]. As another example, emerging behavioral measurement methods may be augmented to develop novel mental training technologies to target and train the metacognitive processes with high temporal- and contextual-resolution (e.g., real-time feedback to train meta-awareness of biased attentional processing [40]). In summary, by guiding the development and testing of measurement and experimental methods, the Metacognitive Processes Model of Decentering may have notable implications for advancing the science and practice of decentering.

Highlights.

We previously proposed that three metacognitive processes constitute decentering

Experience sampling and behavioral tasks advance knowledge of decentering

Micro-interventions advance experimental study of decentering

Findings provide empirical support for the metacognitive model of decentering

Findings elucidate pathways through which decentering contributes to mental health

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Israel Science Foundation (2046/17, Bernstein), a Mind and Life Institute Varela Award (2015-Varela, Hadash) and a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant (1R01HL119977, Fresco) & National Institute of Nursing Research Grant (1P30NR015326, Fresco).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

None declared

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G, Cognitive therapy of depression, Guilford press, New York, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG, Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change (2nd ed), Guilford Press, New York, NY, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Teasdale JD, Moore RG, Hayhurst H, Pope M, Williams S, V Segal Z, Metacognitive awareness and prevention of relapse in depression: Empirical evidence, J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 70 (2002) 275–287. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.70.2.275.*Seminal study of decentering as a candidate mediating mechanism of action in MBCT for depression relapse.

- [4].Wells A, Emotional disorders and metacognition: Innovative cognitive therapy, John Wiley & Sons, West Sussex, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Farb N, Anderson A, Ravindran A, Hawley L, Irving J, Mancuso E, Gulamani T, Williams G, Ferguson A, Segal ZV, Prevention of relapse/recurrence in major depressive disorder with either mindfulness-based cognitive therapy or cognitive therapy., J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 86 (2018) 200–204. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Teasdale JD, Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression (2nd ed). (2013). Guilford Press: New York. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bernstein A, Hadash Y, Lichtash Y, Tanay G, Shepherd K, Fresco DM, Decentering and Related Constructs: A Critical Review and Metacognitive Processes Model, Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 10 (2015) 599–617. doi: 10.1177/1745691615594577.**Paper laying out a metacognitive processes model of decentering and related constructs and reviewing research linking these constructs and respective metacognitive processes to mental health.

- [8].Brown KW, Ryan RM, Creswell JD, Mindfulness: Theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects, Psychol. Inq. 18 (2007) 211–237. doi: 10.1080/10478400701598298. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Creswell JD, Mindfulness Interventions, Annu. Rev. Psychol. 68 (2017) 491–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-042716-051139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Dahl CJ, Lutz A, Davidson RJ, Reconstructing and deconstructing the self: Cognitive mechanisms in meditation practice, Trends Cogn. Sci. 19 (2015) 515–523. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2015.07.001.*Review paper proposing a novel framework to classify meditation practices into attentional, constructive, and deconstructive families as a function of their respective cognitive mechanisms.

- [11].Shapiro SL, Carlson LE, Astin JA, Freedman B, Mechanisms of mindfulness J Clin. Psychol. 62 (2006) 373–386. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Vago DR, Silbersweig DA, Self-awareness, self-regulation, and self-transcendence (S-ART): A framework for understanding the neurobiological mechanisms of mindfulness, Front. Hum. Neurosci. 6 (2012) 1–30. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Smallwood J, Schooler JW, The science of mind wandering: Empirically navigating the stream of consciousness, Annu. Rev. Psychol. 66 (2015) 487–518. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015331.*Review paper of the phenomenology and function of mind wandering and interaction between meta-awareness and mind wandering.

- [14].Carmody J, Evolving conceptions of mindfulness in clinical settings, J. Cogn. Psychother. 23 (2009) 270–280. doi: 10.1891/0889-8391.23.3.270. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Jankowski T, Holas P, Metacognitive model of mindfulness, Conscious. Cogn. 28 (2014) 64–80. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hadash Y, Lichtash Y, Bernstein A, Measuring Decentering and Related Constructs: Capacity and Limitations of Extant Assessment Scales, Mindfulness. 8 (2017) 1674–1688. doi: 10.1007/s12671-017-0743-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Naragon-Gainey K, DeMarree KG, Structure and validity of measures of decentering and defusion., Psychol. Assess. 29 (2017) 935–954. doi: 10.1037/pas0000405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Forman EM, Herbert JD, Juarascio AS, Yeomans PD, Zebell JA, Goetter EM, Moitra E, The Drexel defusion scale: A new measure of experiential distancing, J. Context. Behav. Sci. 1 (2012) 55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2012.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Fresco DM, Moore MT, van Dulmen MHM, Segal ZV, Ma SH, Teasdale JD, Williams JMG, Initial Psychometric Properties of the Experiences Questionnaire: Validation of a Self-Report Measure of Decentering, Behav. Ther. 38 (2007) 234–246. doi: 10.1016/J.BETH.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gillanders DT, Bolderston H, Bond FW, Dempster M, Flaxman PE, Campbell L, Kerr S, Tansey L, Noel P, Ferenbach C, Masley S, Roach L, Lloyd J, May L, Clarke S, Remington B, The Development and Initial Validation of the Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire, Behav. Ther. 45 (2014) 83–101. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Herzberg KN, Sheppard SC, Forsyth JP, Credé M, Earleywine M, Eifert GH, The Believability of Anxious Feelings and Thoughts Questionnaire (BAFT): A psychometric evaluation of cognitive fusion in a nonclinical and highly anxious community sample, Psychol. Assess. 24 (2012) 877–891. doi: 10.1037/a0027782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Lau MA, Bishop SR, V Segal Z, Buis T, Anderson ND, Carlson L, Shapiro S, Carmody J, Abbey S, Devins G, The Toronto mindfulness scale: Development and validation, J. Clin. Psychol. 62 (2006) 1445–1467. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Teasdale JD, Scott J, Moore RG, Hayhurst H, Pope M, Paykel ES, How does cognitive therapy prevent relapse in residual depression? Evidence from a controlled trial., J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 69 (2001) 347–357. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.69.3.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Zettle RD, Hayes SC, Dysfunctional control by client verbal behavior: The context of reason-giving, Anal. Verbal Behav. 4 (1986) 30–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR, Ecological Momentary Assessment, Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 4 (2008) 1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Shoham A, Goldstein P, Oren R, Spivak D, Bernstein A, Decentering in the process of cultivating mindfulness: An experience-sampling study in time and context., J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 85 (2017) 123–134. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000154.*Study of intensive experience sampling of decentering over the course of a multi-session mindfulness training intervention.

- [27].Shoham A, Hadash Y, Bernstein A, Examining the Decoupling Model of Equanimity in Mindfulness Training: An Intensive Experience Sampling Study, Clin. Psychol. Sci. 6 (2018) 704–720. doi: 10.1177/2167702618770446. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hadash Y, Bernstein A, Behavioral Assessment of Mindfulness: Defining Features, Organizing Framework, and Review of Emerging Methods, Current Opinion in Psychology (2019), this issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Schooler JW, Smallwood J, Christoff K, Handy TC, Reichle ED, Sayette MA, Meta-awareness, perceptual decoupling and the wandering mind, Trends Cogn. Sci. 15 (2011) 319–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Christoff K et al. Mind-wandering with and without awareness: An fMRI study of spontaneous thought processes. Proc. Ann. Mtg. of the Cog. Sci. Soc. Vol. 28 No. 28 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- [31].Christoff K, Gordon AM, Smallwood J, Smith R, Schooler JW, Experience sampling during fMRI reveals default network and executive system contributions to mind wandering, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106 (2009) 8719–8724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900234106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hasenkamp W, Wilson-Mendenhall C, Duncan E, Barsalou LW, Mind wandering and attention during focused meditation: A fine-grained temporal analysis of fluctuating cognitive states, Neuroimage. 59 (2012) 750–760. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Smallwood J, McSpadden M, Schooler JW, The lights are on but no one’s home: Meta-awareness and the decoupling of attention when the mind wanders, Psychon. Bull. Rev. 14 (2007) 527–533. doi: 10.3758/BF03194102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Garfinkel SN, Seth AK, Barrett AB, Suzuki K, Critchley HD, Knowing your own heart: Distinguishing interoceptive accuracy from interoceptive awareness, Biol. Psychol. 104 (2015) 65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kleckner IR, Wormwood JB, Kyle SW, Barrett LF, Quigley KS, Methodological recommendations for a heartbeat detection based measure of interoceptive sensitivity, Psychophysiology. 52 (2015) 1432–1440. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Ruimi L, Hadash Y, Zvielli A, Amir I, Goldstein P, Bernstein A, Meta-awareness of dysregulated emotional attention, Clin. Psychol. Sci. 6 (2018) 658–670. doi: 10.1177/2167702618776948.*Study proposing a novel approach to the measurement and study of meta-awareness of biases of attentional processing as they unfold dynamically from moment-to-moment in time.

- [37].Hadash Y, Plonsker R, Vago DR, Bernstein A, Experiential self-referential and selfless processing in mindfulness and mental health: Conceptual model and implicit measurement methodology, Psychol. Assess. 28 (2016) 856–869. doi: 10.1037/pas0000300.*Study testing a novel paradigm to measure and study disidentification from internal experience.

- [38].Hadash Y, Bernstein A, Measuring self-referential and selfless processing of experience: The Single Experience and Self-Implicit Association Test (SES-IAT), in: Medvedev ON, Krägeloh CU, Siegert RJ, Singh NN (Eds.), Handbook of assessment in mindfulness, (2019), Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Sudevan P, Taylor DA, The cuing and priming of cognitive operations., J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 13 (1987) 89–103. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.13.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Bernstein A, Zvielli A, Attention Feedback Awareness and Control Training (A-FACT): Experimental test of a novel intervention paradigm targeting attentional bias, Behav. Res. Ther. 55 (2014) 18–26. doi: 10.1016/J.BRAT.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Zvielli A, Amir I, Goldstein P, Bernstein A, Targeting Biased Emotional Attention to Threat as a Dynamic Process in Time, Clin. Psychol. Sci. 4 (2016) 287–298. doi: 10.1177/2167702615588048.*Study of a computerized cognitive training therapeutic technology to train meta-awareness of biased attentional processing as it unfolds dynamically from moment-to-moment in time.

- [42].Kross E, Vickers BD, Orvell A, Gainsburg I, Moran TP, Boyer M, Jonides J, Moser J, Ayduk O, Third-Person Self-Talk Reduces Ebola Worry and Risk Perception by Enhancing Rational Thinking, Appl. Psychol. Heal. Well-Being. 9 (2017) 387–409. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12103.*Study of novel third-person self-talk micro-intervention to influence cognition and psychological vulnerability

- [43].Kross E, Bruehlman-Senecal E, Park J, Burson A, Dougherty A, Shablack H, Bremner R, Moser J, Ayduk O, Self-talk as a regulatory mechanism: How you do it matters., J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 106 (2014) 304–324. doi: 10.1037/a0035173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Kross E, Ayduk O, Making Meaning out of Negative Experiences by Self-Distancing, Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 20 (2011) 187–191. doi: 10.1177/0963721411408883. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Collins LM, Nahum-Shani I, Almirall D, Optimization of behavioral dynamic treatment regimens based on the sequential, multiple assignment, randomized trial (SMART), Clin. Trials J. Soc. Clin. Trials. 11 (2014) 426–434. doi: 10.1177/1740774514536795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Nahum-Shani I, Smith SN, Spring BJ, Collins LM, Witkiewitz K, Tewari A, Murphy SA, Just-in-Time Adaptive Interventions (JITAIs) in Mobile Health: Key Components and Design Principles for Ongoing Health Behavior Support, Ann. Behav. Med. 52 (2016) 446–462. doi: 10.1007/s12160-016-9830-8.*Review of rationale for and methodological features of just-in-time adaptive mobile micro-interventions to promote health behaviors.

- [47].Safran J, V Segal Z, Interpersonal process in cognitive therapy, Basic Books, New York, NY, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Wells A, The Metacognitive Model of GAD: Assessment of Meta-Worry and Relationship With DSM-IV Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Cognit. Ther. Res. 29 (2005) 107–121. doi: 10.1007/s10608-005-1652-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Bishop SR, Lau M, Shapiro S, Carlson L, Anderson ND, Carmody J, V Segal Z, Abbey S, Speca M, Velting D, Devins G, Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition, Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 11 (2004) 230–241. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bph077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Kross E, Ayduk O, Mischel W, When Asking “Why” Does Not Hurt: Distinguishing Rumination From Reflective Processing of Negative Emotions, Psychol. Sci. 16 (2005) 709–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Lutz A, Jha AP, Dunne JD, Saron CD, Investigating the phenomenological matrix of mindfulness-related practices from a neurocognitive perspective, Am. Psychol. 70 (2015) 632–658. doi: 10.1037/a0039585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]