Abstract

Phosphorylation of the N‐terminal domain of the huntingtin (HTT) protein has emerged as an important regulator of its localization, structure, aggregation, clearance and toxicity. However, validation of the effect of bona fide phosphorylation in vivo and assessing the therapeutic potential of targeting phosphorylation for the treatment of Huntington's disease (HD) require the identification of the enzymes that regulate HTT phosphorylation. Herein, we report the discovery and validation of a kinase, TANK‐binding kinase 1 (TBK1), that efficiently phosphorylates full‐length and N‐terminal HTT fragments in vitro (at S13/S16), in cells (at S13) and in vivo. TBK1 expression in HD models (cells, primary neurons, and Caenorhabditis elegans) increases mutant HTT exon 1 phosphorylation and reduces its aggregation and cytotoxicity. We demonstrate that the TBK1‐mediated neuroprotective effects are due to phosphorylation‐dependent inhibition of mutant HTT exon 1 aggregation and an increase in autophagic clearance of mutant HTT. These findings suggest that upregulation and/or activation of TBK1 represents a viable strategy for the treatment of HD by simultaneously lowering mutant HTT levels and blocking its aggregation.

Keywords: autophagy, huntingtin phosphorylation, Huntington's disease, reducing aggregation, TBK1

Subject Categories: Molecular Biology of Disease, Neuroscience

Phosphorylation of the N‐terminal domain of Huntingtin (HTT) by TANK‐binding kinase 1 (TBK1) promotes its autophagic clearance and reduce its aggregation and cytotoxicity, suggesting new strategies for neuroprotective therapies.

Introduction

Huntington's disease (HD) is an autosomal dominant, progressive neurodegenerative disease caused by a CAG triplet repeat expansion (> 35) in the huntingtin gene. This translates into a polyglutamine (polyQ) repeat immediately following the first 17 amino acids (N17) in the Huntingtin protein (HTT). PolyQ repeats in the disease range (> 36, hereafter denoted as mutant HTT) render HTT more susceptible to misfolding, thus leading to the formation of HTT aggregates in cells and neurons (Scherzinger et al, 1999; Caron et al, 2013; Cui et al, 2014; Fodale et al, 2014; Daldin et al, 2017). Increasing evidence from human studies has shown that expansion of the polyQ repeat is the causative mutation of HD but not the only contributor to disease onset, duration, and severity (Wexler et al, 2004; Andresen et al, 2007; Lee et al, 2019). This suggests that other factors may play important roles in modifying the course of the disease and potentially the patient response to therapies.

Post‐translational modifications (PTMs), particularly within the N17 of the HTT protein, have emerged as key regulators of HTT stability, clearance, localization, proteolysis, aggregation, and toxicity in different models of HD (Ehrnhoefer et al, 2011; Saudou & Humbert, 2016), including mouse HD models (Gu et al, 2009). These studies were largely based on the mutation of PTM‐targeted residues to mimic or abolish the presence of relevant PTMs. Among all the putative PTMs that have been identified in the HTT protein, phosphorylation at the N‐terminal serine residues S13 and S16 is the most studied for the following reasons: (i) It occurs on several residues in close proximity to the polyQ domain and within the N17 domain, which has been shown to play important roles in regulating HTT structure, aggregation, and subcellular localization (Rockabrand et al, 2007; Gu et al, 2009; Thompson et al, 2009); (ii) mimicking phosphorylation at these residues in the context of the full‐length mutant HTT protein (S13D/S16D) in mice was sufficient to ameliorate HD phenotypes, including motor and psychiatric‐like behavioral deficits, mutant HTT aggregation, and selective neurodegeneration (Gu et al, 2009); and (iii) the levels of phosphorylation at T3 and S13/S16 are reduced in HD models (Thompson et al, 2009; Atwal et al, 2011; Cariulo et al, 2019). These observations suggest that targeting HTT PTMs at N17 represents a viable strategy for developing novel disease‐modifying therapies for HD. The first step towards assessing the therapeutic potential of targeting N17 PTMs for the treatment of HD is the identification of the enzymes that regulate these PTMs. This is important because increasing evidence shows that phosphorylation‐mimicking mutations (e.g., serine (S) or threonine (T) to aspartate (D) or glutamate (E)) used to investigate the effects of protein phosphorylation may not fully phenocopy the effects of the bona fide modifications (Szczepanowska et al, 1998; Paleologou et al, 2008; Dephoure et al, 2013; Chiki et al, 2017; Deguire et al, 2018) and do not faithfully reproduce the dynamic nature of phosphorylation.

We and others have shown that phosphorylation or introduction of phosphomimicking mutations at S13 and/or S16 inhibit the aggregation of mutant HTTex1 or HTTex1 model peptides (Gu et al, 2009; Mishra et al, 2012; Deguire et al, 2018) and increases HTTex1 conformational flexibility in vitro (Daldin et al, 2017). A direct comparison of the effect of phosphomimetics and bona fide phosphorylation at these sites showed that the phosphomimetic (S13D/S16D) only partially reproduced the effect of phosphorylation on HTTex 1 aggregation in vitro and did not reproduce the effect of single and double phosphorylation at these residues on the helical conformation of N17 peptides (Deguire et al, 2018). Moreover, a recent study using a Drosophila model of HD expressing HTTex1 97Q showed that both S13D and S16D increase aggregation (Branco‐Santos et al, 2017), in contrast to observations in mammalian cell models of HD showing that the N‐terminal fragments of HTT 1‐171 142Q, HTTex1 97Q, or HTTex1 82Q with S13D and S16D with S13D and S16D exhibit decreased aggregation and toxicity (Atwal et al, 2011; Arbez et al, 2017; Branco‐Santos et al, 2017). These findings show that PTMs, such as single or double phosphorylation, are sufficient to modify mutant HTT levels, aggregation, and toxicity, but also emphasize the importance of identifying the natural kinases involved in regulating HTT phosphorylation to assess the biological relevance and therapeutic potential of bona fide phosphorylation at these residues.

In the current study, we sought to identify the natural kinases that efficiently phosphorylate HTT at S13 and S16, with the aim of using these kinases to assess the therapeutic potential of phosphorylation at these residues by investigating its effect on mutant HTT aggregation, clearance, and toxicity in cellular and animal models of HD. Using an in vitro screen of ~300 serine and threonine kinases, we identified TANK‐binding kinase 1 (TBK1) as one of the most promising candidate kinases. In an in vitro phosphorylation assays, TBK1 induced site‐specific and quantitative phosphorylation of both wild‐type and mutant HTT at both residues S13 and S16. TBK1 is known to regulate the innate immune response and belongs to the IκB kinase family that includes other kinases such as IKKβ. Previously, IKKβ was shown to phosphorylate HTT at these residues (Thompson et al, 2009) as well as at residue T3 (Bustamante et al, 2015), and was recently shown to increase HTT S13 phosphorylation in HD and wild‐type mice (Ochaba et al, 2019). In this work, the specificity and efficiency of TBK1 for phosphorylating full‐length and N‐terminal fragments of HTT (HTTex1, HTTN548, HTT‐fl) were validated in vitro using recombinant proteins, in mammalian cells, in primary neuronal culture and in vivo via overexpression of the wild‐type and kinase‐dead variant of TBK1. Next, we assessed the effect of TBK1‐mediated phosphorylation on HTT levels, subcellular localization, aggregation, and toxicity in cellular, neuronal, and Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) models of HD. In all these model systems, we observed that TBK1 phosphorylated the HTT protein at S13, decreased its levels, inhibited its aggregation, and suppressed its toxicity. Furthermore, mechanistic studies showed that these effects were mediated by both TBK1‐dependent phosphorylation of HTT, which stabilized the protein and blocked its aggregation, and TBK1‐mediated increased autophagic flux, which also promoted the clearance of HTT, leading to a decrease in HTT aggregation. Together, our results show that increasing phosphorylation at S13 and/or TBK1 activation or upregulation represent viable therapeutic strategies for the treatment of HD.

Results

Identification of TBK1 as a kinase that efficiently phosphorylates HTT at S13 in cellular models of HD

To discover kinases responsible for phosphorylating HTT at S13 and S16, we used a commercial in vitro kinase screening assay (Kinexus in vitro kinase and phospho‐peptide testing (IKPT) services), which includes ~300 kinases (Binukumar et al, 2016). The screen was carried out using two HTT substrates: a peptide that comprises the first 17 N‐terminal residues of HTT (N17), and the first exon of the HTT protein (HTTex1) (Fig 1A–C). After an extensive in vitro validation using the top kinase hits from the screen, which included monitoring of the extent of phosphorylation using mass spectrometry as well as by the use of previously validated phospho‐antibodies against T3 (pT3), S13 (pS13), and S16 (pS16) (Bustamante et al, 2015; Deguire et al, 2018; Cariulo et al, 2019), TBK1 was identified as the only kinase that selectively and robustly phosphorylated HTTex1 in vitro at S13 and S16 (Figs 1C and EV1A–E). Additionally, TBK1‐mediated phosphorylation of the longer N‐terminal fragments resulted predominantly in diphosphorylation at both S13 and S16, along with a small amount of tri‐phosphorylated and traces of tetra‐phosphorylated species for some of the longer N‐terminal HTT fragments (Fig EV1A and B). For these substrates and HTTex1, a signal was observed for only the pS13 and pS16 antibodies, demonstrating that TBK1 did not phosphorylate HTTex1 at T3 (Fig EV1A and B lower panel). Consistent with these data, we did not observe any phosphorylation of a HTTex1 mutant in which both residues were mutated to aspartate (S13D/S16D), even after extended periods of incubation with TBK1 (Fig EV1C–E).

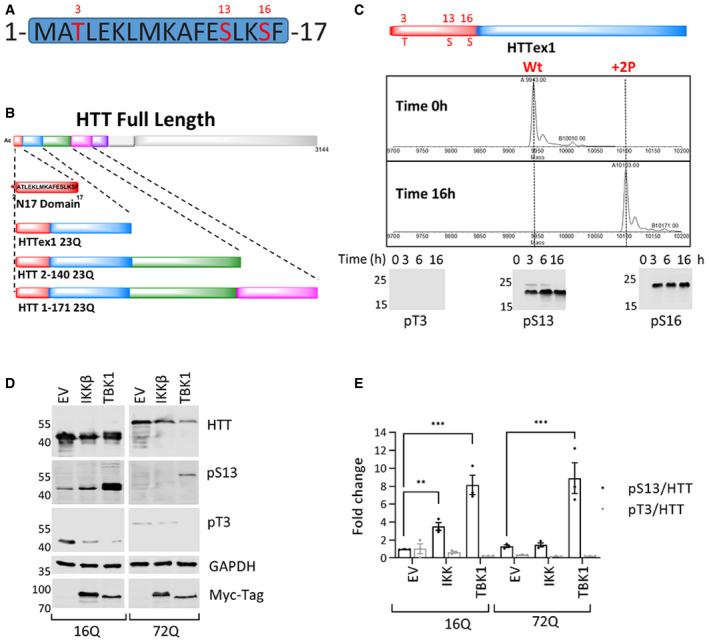

Figure 1. Identification of TBK1 as a kinase that efficiently phosphorylates HTT at S13 in cellular models of HD .

- Potential phosphorylation sites in the HTT N17 domain (T3, S13, and S16).

- List of all the different substrates used for the in vitro kinase validation: Nt17, HTTex1, and HTT longer fragments.

- Mass spectra of recombinant HTTex1 23Q after 16 h of co‐incubation with TBK1 showing complete phosphorylation of S13 and S16. The lower panel is a representative Western blot of the same phosphorylation reaction (upper panel) using anti‐pT3 (CHDI‐90001528‐1), pS13 HTT (CHDI‐90001039‐1), and pS16 (ZCH11020 generated in house) antibodies (ab) after the indicated phosphorylation reaction times.

- Representative Western blot of HTT (ab‐MAB5492), HTT pS13 (ab‐CHDI-90001039‐1), and HTT pT3 (ab‐CHDI-90001528‐1) upon coexpression of HTTex1 16Q and 72Q eGFP with the indicated kinases for 48 h in HEK293 cells.

- Quantification of the fold changes in the HTT pS13 and pT3 ratios to total HTT compared to empty vector (EV) control upon coexpression of the indicated kinase from the experiments like in D.

Figure EV1. (Related to Fig 1): TBK1 phosphorylates longer fragments of HTT at S13 and S16 in vitro .

- Mass spectra of recombinant HTT 2‐140 23Q after the indicated times of phosphorylation by TBK1. The lower panel is a representative Western blot using anti‐pT3 (CHDI‐90001528‐1), pS13 HTT (CHDI‐90001039‐1), and pS16 (ZCH11020 generated in house) antibodies of HTT 1–140 23Q after its phosphorylation with TBK1 according to the indicated reaction time.

- Mass spectra of recombinant HTT 1‐171 23Q after the indicated times of phosphorylation by TBK1. The lower panel is a representative Western blot using anti‐pT3 (CHDI‐90001528‐1), pS13 HTT (CHDI‐90001039‐1), and pS16 (ZCH11020 generated in house) antibodies of HTT 1‐171 23Q after its phosphorylation with TBK1 according to the indicated reaction time.

- Representative mass spectra of HTTex1 23Q after 16 h of phosphorylation by TBK1 (* salt adducts, + Sinapinic acid matrix adduct).

- Representative mass spectra of HTTex1 23Q pT3 after 16 h of phosphorylation by TBK1 (* salt adducts, + Sinapinic acid matrix adduct).

- Representative mass spectra of HTTex1‐23Q S13D/S16D after 16 h of phosphorylation by TBK1 (* salt adducts, + Sinapinic acid matrix adduct).

Source data are available online for this figure.

The TBK1 family kinase IKKβ was previously reported to phosphorylate HTT at S13/S16 (Thompson et al, 2009). Therefore, we sought to compare the efficiency of TBK1‐ and IKKβ‐mediated phosphorylation of HTTex1. To this end, we compared the kinetics and efficiency of HTTex1 phosphorylation by these two kinases. As shown in Appendix Fig S1A–D, we observed significantly faster phosphorylation by TBK1 than by IKKβ at both S13 and S16 residues. IKKβ seemed to require a longer time to phosphorylate HTT. After 6 h, TBK1 resulted in almost complete diphosphorylation, whereas IKKβ showed predominantly mono‐phosphorylated HTT even after 16 h, with a significant amount of non‐phosphorylated HTT remaining (Appendix Fig S1B and D). This observed difference may also be due to the difference in activity of TBK1 and IKKβ as efficient activity of the later may need IKK complex subunits IKKα and IKKγ. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that TBK1 efficiently and site‐specifically phosphorylates recombinant HTT at S13 and S16 in vitro, suggesting that it could be one of the natural kinases that may regulate HTT phosphorylation and cellular properties in vivo.

Next, to determine whether TBK1 phosphorylates the N‐terminal domain of HTT in cells, we assessed the level of phosphorylation at S13 upon coexpression of wild‐type (16Q) or mutant (72Q) HTTex1 with TBK1 in HEK293 cells by Western blot (WB) using the phospho‐antibodies against T3 (pT3) and S13 (pS13). We observed that TBK1 coexpression for 48 h led to a strong ~5‐ to 10‐fold increase in phosphorylation at S13 (Fig 1D and E) compared to empty vector (EV) control. Before this study, IKKβ was reported to phosphorylate HTT at S13/S16 with a preference for HTT containing unexpanded polyQ repeats (Thompson et al, 2009). Therefore, we sought to compare the phosphorylation efficiency of TBK1 and IKKβ on mutant and wild‐type HTTex1. As shown in Fig 1D and E, IKKβ indeed phosphorylated HTTex1 16Q more efficiently than 72Q, but the phosphorylation levels were much lower than the levels achieved upon coexpression with TBK1, consistent with our in vitro data (Appendix Fig S1A and D). However, this comparison may not be accurate as the activity of IKKβ could be influenced by IKKα and IKKγ, which may work together within the IKK complex.

In our in vitro assay, we observed that TBK1 phosphorylated HTT at both S13 and S16, but due to the lack of a specific antibody that recognizes phosphorylation at S16 in cell lysates, we could not directly evaluate whether TBK1 phosphorylated S16 in cellular models by WB. To confirm the sites of phosphorylation in cells, we performed MS/MS analysis of HTTex1 immunoprecipitated from TBK1 and TBK1 KD coexpressing wild‐type 16Q HTTex1 HEK293 cells. While we detected the phosphorylation at S13, we did not observe any phosphorylation at S16 on HTT under these conditions (Fig EV2A and B). These results suggest that TBK1 phosphorylates HTT at S13 but not at S16 in cells, whereas both sites are efficiently phosphorylated in vitro (Fig 1C).

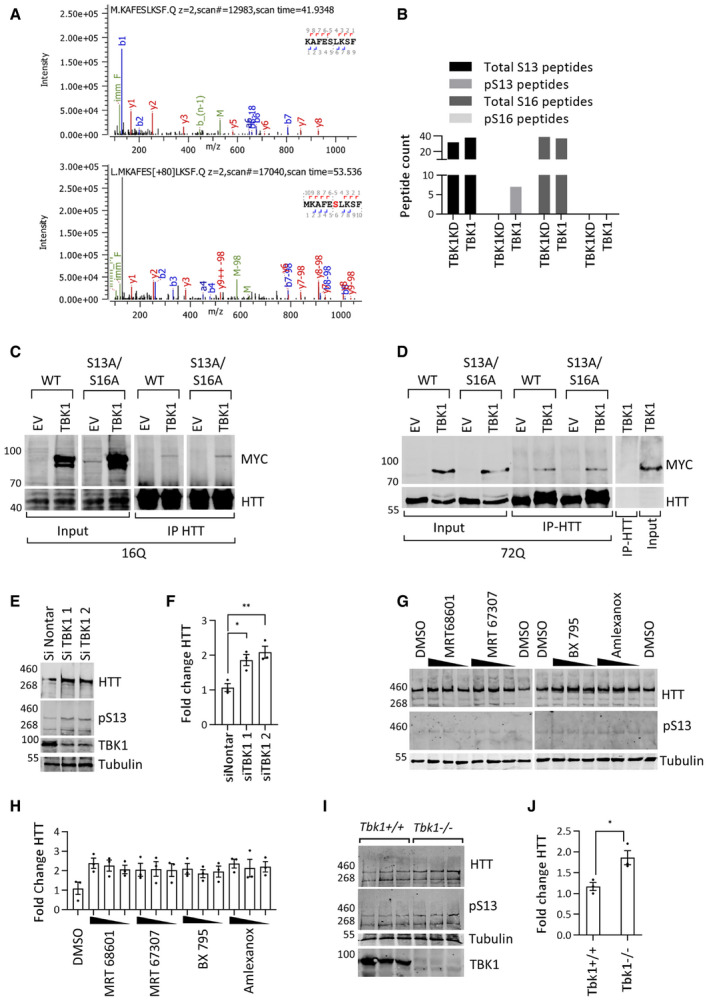

Figure EV2. (Related to Fig 2): TBK1 phosphorylates HTT at S13 in cellular models and regulates endogenous HTT levels.

- MS/MS spectra of the S13/S16 amino acids containing peptides from HTT immunoprecipitated (IP) from HEK293 cell lysates after coexpression of HTTex1 16Q eGFP with TBK1 KD (upper panel) or TBK1 (lower panel).

- Spectral counting of the total WT peptide compared to S13 and S16 peptides from the coexpression with TBK1 or TBK1 KD (n = 1).

- Representative Western blot of the indicated kinase (ab‐anti-Myc) from the immunoprecipitation (using anti‐GFP antibody) of HTTex1 16Q eGFP coexpressed with kinase for 48 h in HEK293 cells (n = 3).

- Representative Western blot of the indicated kinase (ab‐anti-Myc) from the immunoprecipitation (using anti‐GFP antibody) of HTTex1 72Q eGFP coexpressed with kinase for 48 h in HEK293 cells (n = 3).

- Representative Western blot of endogenous HTT (anti‐HTT-D7F7) and HTT pS13 (ab‐CHDI-90001039‐1) after treatment with TBK1 siRNA for 72 h in rat primary striatal neuronal cells.

- Quantification of the fold change in HTT normalized to the HTT levels in non‐targeting siRNA normalized to tubulin from the experiments like in E (n = 3).

- Representative Western blot of endogenous HTT (ab‐MAB2166) and HTT pS13 (ab‐CHDI-90001039‐1) after treatment with the indicated TBK1 inhibitors (concentrations of 2, 1, and 0.5 μM) for 48 h in rat primary striatal neuronal cells.

- Quantification of the fold change in HTT compared to DMSO treatment normalized to tubulin from the experiments like in G (n = 3).

- Western blot of HTT (anti‐HTT-D7F7) and HTT pS13 (ab‐CHDI-90001039‐1) levels in cortex tissue lysates from Tbk1 −/− and Tnf‐α −/− mice (n = 3).

- Quantification of the fold change in HTT compared to Tbk1 +/+ normalized to tubulin from I.

Next, we asked whether the kinase activity of TBK1 was required for the phosphorylation of HTT. To answer this question, we compared the level of phosphorylation at S13 upon coexpression of HTTex1 16Q or 72Q with wild‐type TBK1 or a TBK1 kinase‐dead (TBK1 KD) mutant (K38A; Richter et al, 2016). While WT TBK1 increased S13 phosphorylation, no significant increase in phosphorylation was detected upon expression of TBK1 KD (Fig 2A and B). This confirms that HTT S13 phosphorylation is dependent on the catalytic activity of TBK1. Next, we sought to verify the site specificity of TBK1 phosphorylation of HTT in cells. To this end, we coexpressed HTT with alanine mutations at residue 3 (T3A) or residues 13/16 (S13A/S16A) with TBK1 or TBK1 KD. We observed that TBK1 did not phosphorylate HTTex1 S13A/S16A but phosphorylated S13 on HTTex1 T3A (Fig 2A and B), confirming that TBK1 specifically phosphorylates S13 on HTTex1. Interestingly, we observed residual phosphorylation at S13 in TBK1 KD, which could be due to other endogenous kinases, including but not limited to IKKβ. In contrast to previous reports (Thompson et al, 2009) and our observations for IKKβ in this study, TBK1 phosphorylated both wild‐type and mutant HTTex1 with the same efficiency (Figs 1D and E and 2A and B). These findings suggest that the polyQ expansion does not significantly influence TBK1‐dependent phosphorylation of S13.

Figure 2. TBK1 phosphorylates HTT in cellular models.

- Representative Western blot of HTT (ab‐MAB5492), HTT pS13 (ab‐CHDI-90001039‐1), and HTT pT3 (ab‐CHDI-90001528‐1) upon coexpression of HTTex1 16Q eGFP mutants with S to A substitutions at T3 or S13/S16 or HTTex1 72Q eGFP with TBK1 or TBK1 kinase‐dead (KD) for 48 h in HEK293 cells (the additional high molecular weight HTTex1 and HTT pS13 band is possibly due to the co‐occurrence of phosphorylation at both S13 and T3).

- Quantification of the fold changes in the HTT pS13 (upper panel) and pT3 (lower panel) ratio to total HTT compared to those of the kinase‐dead mutant from the experiments like in A (n = 3).

- Representative Western blot of HTT (ab‐MAB2166) and HTT pS13 (ab‐CHDI-90001039‐1) upon coexpression of HTT N543 55Q with the indicated kinase for 24 h in HEK293T cells.

- Quantification of HTT pS13 using the Singulex assay (using ab‐MW1 as capture and CHDI‐90001039 or 2B7 as detection antibodies for pS13 or total HTT) upon coexpression of HTT N543 55Q with the indicated kinase for 24 h in HEK293T cells from the experiment in C (representative of 3 repeats).

- Representative Western blot of HTT (ab‐MAB2166) and HTT pS13 (ab‐CHDI-90001039‐1) upon coexpression of HTT‐fl 48Q or HTT‐fl 48Q S13A/S16A with the indicated kinase for 24 h in HEK293T cells.

- Quantification of HTT pS13 using the Singulex assay (using ab‐MW1 as capture and CHDI‐90001039 or 2B7 as detection antibodies for pS13 or total HTT) upon coexpression of HTT‐fl 48Q or HTT‐fl 48Q S13A/S16A with the indicated kinase for 24 h in HEK293T cells from the experiments like in E (n = 3).

- Representative Western blot of immunoprecipitated (IP) HTT (ab‐MAB2166) and HTT pS13 (ab‐CHDI-90001039‐1) after lentivirus (LV)‐mediated overexpression of TBK1 or TBK1 KD for 72 h in rat primary striatal neuronal cells.

- Quantification of the fold changes in the HTT pS13 ratio to total HTT compared to those of the kinase‐dead mutant from the experiments like in G (n = 3).

Having established that TBK1 phosphorylated HTTex1 and other fragments in different cellular models, we sought to determine whether TBK1 interacts directly with its HTT substrates. To this end, we coexpressed TBK1 or TBK1 KD with wild‐type HTTex1 16Q or HTTex1 72Q or bearing the S13A/S16A mutation for 48 h in HEK293 cells and immunoprecipitated HTT. We observed that TBK1 specifically co‐immunoprecipitated with HTTex1 irrespective of the presence or absence of the S13A/S16A mutation (Fig EV2C and D). These results suggest that both wild‐type and mutant HTTex1 may interact with TBK1 in cells and that the phosphorylation‐blocking mutations at S13 and S16 do not influence the HTT‐TBK1 interaction.

Under physiological conditions, HTT exists as a mixture of different N‐terminal fragments and full‐length HTT (Mende‐Mueller et al, 2001). Therefore, we sought to examine whether TBK1 could phosphorylate longer N‐terminal fragments and full‐length HTT proteins. We coexpressed either the mutant HTTN548 (55Q) fragment or a full‐length mutant HTT (HTT‐fl 48Q) with TBK1 or TBK1 KD in HEK293T cells and analyzed S13 phosphorylation by WB using an HTT pS13 antibody and using a new, sensitive Singulex assay (Cariulo et al, 2019). We observed by WB that TBK1 phosphorylated both the HTTN548 55Q fragment (Fig 2C) and HTT‐fl 48Q at S13 (Fig 2E). Quantitative Singulex immunoassay analysis of cell lysates showed that TBK1 coexpression led to approximately 60‐ and 20‐fold increases in phosphorylation at S13 of HTTN548 55Q (Fig 2D) and HTT‐fl 48Q (Fig 2F), respectively. As expected, we did not observe any significant increase in phosphorylation upon coexpression of TBK1 or TBK1 KD with HTT‐fl 48Q bearing the S13A and S16A mutations (Fig 2F). We further assessed whether TBK1 could phosphorylate endogenous HTT in neurons. We overexpressed TBK1 or TBK1 KD using lentivirus‐mediated transduction in rat primary striatal neuronal cultures. Striatal medium spiny neurons are most affected in HD (Ehrlich, 2012), and striatal cells have been used as a model for HD studies (Trettel et al, 2000). We immunoprecipitated endogenous HTT from these striatal culture lysates using the HTT antibody D7F7, followed by immunoblotting with an anti‐pS13 antibody. We observed an increased level of HTT pS13, but not pT3 upon TBK1 expression. This confirmed that TBK1 phosphorylated endogenous HTT at S13 (Fig 2G and H). Next, to investigate whether TBK1 is one of the endogenous enzymes involved in regulating the levels of endogenous phosphorylation of HTT at S13, we assessed S13 phosphorylation after a genetic knockdown or pharmacological inhibition of TBK1 in primary neurons. We treated rat primary striatal neurons with TBK1 kinase inhibitors for 48 h or with siRNA for 72 h and assessed the effects on HTT and HTT pS13 levels using specific antibodies. As shown in Figure EV2E and F TBK1 knockdown did not lead to a significant change in HTT pS13 levels, but increased endogenous HTT levels by approximately 1.5‐ to 2‐fold. We observed no change in pS13 levels but there was a trend toward an increase in endogenous HTT levels in the inhibitor‐treated striatal neuronal cells (Fig EV2G and H). While these results clearly demonstrate that TBK1 is involved in regulating the turnover of endogenous HTT, no significant change in HTT pS13 levels caused by either inhibitor treatment or siRNA treatment was observed. This might be due to residual TBK1 kinase activity that could phosphorylate endogenous HTT. Alternatively, it is also possible that other kinases like IKKβ may phosphorylate HTT at S13 (Ochaba et al, 2019).

To clarify whether endogenous TBK1 phosphorylated HTT at S13 in the mammalian brain, we used a mouse model of Tbk1 −/− on the Tnf‐α −/− background (Hemmi et al, 2004). We dissected the cortices of P0 mouse pups from the Tbk1 +/+, Tnf‐α +/+ and Tbk1 −/−, Tnf‐α −/− strains, lysed the tissues, and subjected the total protein extract to WB analysis to determine HTT and HTT pS13 levels. This double knockout model was previously used to investigate the function of TBK1 (Hemmi et al, 2004) because Tbk1 knockout was embryonic lethal (Perry et al, 2004). Consistent with the knockdown and inhibitor experiments, we observed no change in pS13 HTT levels but there was an increase in the total HTT level (Fig EV2I and J). These observations may be explained by compensatory mechanisms involving other kinases, or homeostatic mechanisms involving downregulation of relevant phosphatases. However, the increased levels of HTT upon silencing or inhibition of TBK1 indicated an S13 phosphorylation independent role of TBK1 in HTT clearance. Moreover, we observed residual phosphorylation at S13 on HTT in our coexpression experiments which could also be due to IKKβ (Ochaba et al, 2019) or other kinases. These data collectively indicate that TBK1 regulates HTT levels, but there may be other kinases involved in the regulation of HTT phosphorylation at S13.

TBK1 overexpression affects HTT subcellular localization and reduces its aggregation and cytotoxicity

It has been reported that the first 17 amino acids of HTT have multiple roles in regulating the cellular properties of HTT, including its subcellular localization (Steffan et al, 2004; Atwal et al, 2007; Rockabrand et al, 2007). The HTT N17 domain was shown to contain a translocated promoter region (TPR)‐dependent nuclear export signal (Steffan et al, 2004; Benn et al, 2005; Cornett et al, 2005; Atwal et al, 2007; Rockabrand et al, 2007; Maiuri et al, 2013). Mimicking phosphorylation at S13 and S16 (S13D/S16D) increased the localization of the HTT N17 peptide, HTTex1, or longer N‐terminal HTT fragments to the nucleus (Thompson et al, 2009; Atwal et al, 2011; Havel et al, 2011; Zheng et al, 2013; Arbez et al, 2017). Moreover, we recently reported that single or double phosphorylation at S13 and/or S16 significantly enhanced the targeting of mutant HTTex1 fibrils to the nuclear compartment (Deguire et al, 2018). As TBK1 increased S13 phosphorylation, we hypothesized that this could also increase the nuclear localization of HTT. To test this hypothesis, we coexpressed wild‐type or mutant HTTex1 and TBK1 or TBK1 KD in HEK293 cells and then comparatively assessed the levels of nuclear and cytosolic HTT by immunocytochemistry (ICC). We observed increased nuclear intensity of wild‐type or mutant HTTex1 eGFP upon TBK1 coexpression (Fig EV3A and B). We also assessed the levels of HTT proteins biochemically in purified nuclear and cytosolic fractions. Confirming the imaging results, nuclear levels of wild‐type or mutant HTTex1 were increased upon TBK1 coexpression (Fig EV3C and D). These observations show that TBK1‐mediated phosphorylation of HTT increased its nuclear localization, in line with previous reports (Thompson et al, 2009; Atwal et al, 2011).

Figure EV3. (Related to Fig 3): TBK1 overexpression phenocopies effects of HTT S13/S16 phosphomimetic mutations on subcellular localization.

- Immunofluorescence images of the coexpression of HTTex1 16Q eGFP or 72Q eGFP and the indicated kinases for 48 h in HEK293 cells (scale bar 10 μm).

- Quantification of the fold change in nuclear localization upon coexpression of the indicated kinase from experiments like in A (n = 3).

- Representative Western blot of HTT (anti‐HTT-D7F7), HTT pS13 (ab‐CHDI-90001039‐1), lamin‐B1, and β‐tubulin from nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions coexpressing HTTex1 16Q eGFP or 72Q eGFP with the indicated kinases for 16 h in HEK293 cells.

- Quantification fold change of the ratio of nuclear HTTex1 to cytosolic HTTex1 upon coexpression of the indicated kinase compared to HTTex116Q eGFP or 72Q eGFP from the experiments like in C normalized to respective nuclear and cytosolic lamin‐B and tubulin (n = 3).

- Representative Western blot of soluble HTT and insoluble aggregates (ab‐MAB5492), HTT pS13 (ab‐CHDI-90001039‐1), and pT3 (CHDI‐90001528‐1) upon coexpression of HTTex1 72Q eGFP or HTTex1 72Q S13A/S16A eGFP with the TBK1 or TBK1 KD for 48 h in HEK293 cells.

- Quantification of soluble and HTT aggregates indicating the fold change compared to TBK1 KD‐expressing HTTex1 from the experiments like in E (n = 3).

- Representative immunoblot of HTT (ab‐MAB5492) and HTT pS13 (ab‐CHDI-90001039‐1) from a filter retardation assay of HTTex1 43Q fibrils phosphorylated for the indicated times with TBK1 and IKKβ (n = 2).

- Representative Western blot of soluble HTT (ab‐MAB2166) and HTT pS13 (ab‐CHDI-90001039‐1) from the zQ175 HD mouse model whole‐brain lysate at 24 weeks of age.

- Representative immunoblot of insoluble (ab‐MAB5374) and HTT pS13 (ab‐CHDI-90001039‐1) from a filter retardation assay of whole‐brain lysate from the zQ175 HD mouse model at 24 weeks of age (n = 3 per group).

Previous studies indicated that phosphorylation or the introduction of phosphomimetic mutations at both S13 and S16 (Gu et al, 2009; Arbez et al, 2017; Branco‐Santos et al, 2017; Chiki et al, 2017; Deguire et al, 2018) suppress mutant HTT aggregation in vitro and in cellular models. However, the effects of bona fide phosphorylation on mutant HTTex1 aggregation were evaluated only in vitro using semisynthetic proteins (Gu et al, 2009; Daldin et al, 2017; Deguire et al, 2018). Therefore, we tested whether TBK1‐induced phosphorylation influences the aggregation of mutant HTT in HEK293 cells. We used HTTex1 72Q eGFP as a surrogate model of mutant HTT aggregation because the overexpression of this protein has consistently been shown to lead to extensive inclusion formation in different mammalian cells (Arrasate et al, 2004). We coexpressed either phosphorylation‐deficient T3A and S13/S16A or phosphorylation‐competent HTTex1 containing 72Q or 16Q repeats with TBK1 in HEK293 cells for 48 h. Then, we performed a WB analysis of soluble protein extracts and a filter retardation assay to assess the level of aggregated mutant HTT. In parallel, we also evaluated the number of TBK1‐expressing cells presenting cytoplasmic and nuclear aggregates using ICC. Figure 3A and B show that TBK1 coexpression significantly reduced the levels of soluble wild‐type or mutant HTTex1 in an HTT S13/S16 phosphorylation‐independent manner, as evidenced by the decrease in the levels of HTTex1 mutants in which phosphorylation at T3 (T3A) or S13/S16 (S13A/S16A) was prevented by mutation to alanine (Fig 3A and B). Interestingly, we observed a stronger effect for TBK1 than for IKKβ on lowering the levels of soluble wild‐type and mutant HTTex1. The filter retardation assay also showed a phosphorylation‐independent reduction in HTTex1 72Q aggregates in the insoluble cellular fractions (Fig 3C and D). Interestingly, we also observed that similar to TBK1, IKKβ could decrease HTTex1 levels and mutant HTTex1 aggregates in a phosphorylation‐independent manner (Fig 3C and D). Using ICC, we observed that 35–45% of cells expressing phosphorylation‐competent HTTex1 72Q or the phosphorylation‐deficient mutants S13/S16A and T3A formed aggregates, whereas only ~10% of cells coexpressing the same constructs with TBK1 showed aggregate formation (Fig 3E and F). A similar reduction in aggregated mutant HTT levels was observed for the phosphorylation‐deficient HTTex1 mutants S13A/S16A and T3A (Fig 3E and F). These results indicate that the TBK1‐induced reduction of soluble HTTex1 and HTT aggregates could be mediated by mechanisms that do not require phosphorylation of N17 at S13.

Figure 3. TBK1 overexpression affects subcellular localization and reduces aggregation and cytotoxicity of HTT .

- Representative Western blot of soluble HTT (ab‐MAB5492), HTT pS13 (ab‐CHDI-90001039‐1), and HTT pT3 (ab‐CHDI-90001528‐1) upon coexpression of HTTex1 16Q eGFP or 72Q eGFP or its phosphorylation‐incompetent mutants with the indicated kinases for 48 h in HEK293 cells.

- The graph indicates the fold change in HTT in samples like illustrated in A, relative to empty vector controls normalized to GAPDH.

- Representative immunoblot of the HTT (ab‐MAB5492) after filter retardation assay from the insoluble cellular fraction upon expression of HTTex1 16Q eGFP or 72Q eGFP or its phosphorylation‐incompetent mutants with the indicated kinases for 48 h in HEK293 cells.

- Quantification of the fold change in HTT aggregates compared to EV expressing HTTex1 16Q from the experiments like in C.

- Representative immunofluorescence images of HTT aggregates (eGFP) and TBK1 (ab‐anti-MYC) upon coexpression of HTTex1 72Q eGFP or its phosphorylation‐incompetent mutants with the indicated kinases for 48 h in HEK293 cells (scale bar 20 μm).

- Quantification of the percentage of co‐transfected cells presenting aggregates upon expression of the indicated kinase, from the experiments like in E.

- Quantification of the percentage of cells presenting nuclear aggregates from the experiments like in E.

- Representative Western blots of HTT (ab‐MAB5492) and HTT pS13 (ab‐CHDI-90001039‐1) in soluble fraction and aggregates from HEK293 cells transfected first with HTTex1 72Q eGFP and then after 48 h (to enable the formation of aggregates before the kinase expression); with TBK1; cells were lysed at the indicated time after kinase transfection.

- Quantification of the percentage of cells presenting aggregates and kinase expression from the experiments in H.

HEK293T cells transfected with HTTex1 72Q showed the formation of nuclear HTTex1 aggregates in approximately 10% of cells at the indicated time point. Therefore, we further examined the effect of TBK1 coexpression on nuclear aggregates. We observed that TBK1 expression also reduced the level of nuclear aggregates formed by HTTex1 72Q eGFP (Fig 3G).

Next, we sought to determine whether the decrease in the levels of soluble and aggregated mutant HTTex1 was dependent on TBK1 kinase activity. To test this hypothesis, we coexpressed phosphorylation‐competent HTTex1 72Q and phosphorylation‐deficient S13/S16A or the T3A mutant with TBK1 or its TBK1 KD in HEK293 cells. WB analysis of soluble protein extracts and quantification of aggregated mutant HTT by a filter retardation assay showed that TBK1 but not TBK1 KD decreased the levels of both soluble and aggregated HTTex1 72Q (Fig EV3E and F). These results establish that TBK1 coexpression lowers HTT levels in an S13/S16 phosphorylation‐independent manner, suggesting that TBK1 may be involved in regulating HTT clearance largely via other mechanisms.

To determine whether TBK1‐induced reduction of HTT aggregate formation could be mediated by its interaction or phosphorylation of HTT aggregates or inclusions, we assessed whether TBK1 or IKKβ could phosphorylate in vitro‐generated HTTex1 fibrils or mutant HTTex1 aggregates in cells. Toward this aim, we first assessed the ability of TBK1 and IKKβ to phosphorylate preformed HTTex1 43Q fibrils in an in vitro assay and monitored the extent of phosphorylation at S13 by filter retardation immunoblot and mass spectrometry analysis. Interestingly, we observed that neither TBK1 nor IKKβ could phosphorylate preformed HTTex1 43Q fibrils, suggesting that the S13 residue is not readily accessible in the fibrillar conformation or that the kinase does not interact with HTTex1 fibrils (Fig EV3G). We also did not observe any disaggregation or release of HTTex1 43Q monomers during the in vitro phosphorylation reaction as evidenced by the absence of change in the levels of HTTex1 43Q fibrils in the filter retardation assay (Fig EV3G).

To determine whether TBK1 could phosphorylate already formed HTT aggregates in cells, we expressed mutant HTTex1 72Q in HEK293 cells for 48 h. At this time point, ∼40% cells showed mutant HTTex1 aggregates. Then, we transfected TBK1 and monitored the levels of soluble HTT, HTT aggregates, and pS13 HTT over time by WB and the filter retardation assay. First, we did not observe phosphorylation at S13 in the HTTex1 72Q aggregates retained in the filter retardation assay (Fig 3H). Second, there was no increase in the pS13 levels of HTT aggregates upon overexpression of TBK1 after HTT aggregate formation (Fig 3H). These observations suggest that TBK1 phosphorylates monomeric or soluble HTT but not fibrils or inclusions of mutant HTTex1 in a cellular context, consistent with the data obtained in our in vitro phosphorylation assays (Fig EV3G).

Next, we examined whether TBK1 expression enhances the clearance of aggregated forms of mutant HTT. Consistent with our observation in Fig 3A and B, we observed that soluble HTT levels were reduced and S13 phosphorylation was increased upon TBK1 expression at various time points (Fig 3H). The levels of HTT aggregates were not reduced upon TBK1 overexpression at any given time point, suggesting the limited role of TBK1 in the phosphorylation or clearance of mutant HTT aggregates once they were formed. We observed a decrease in soluble HTT, kinase levels, and HTT aggregates at late time points, possibly due to the transient transfection. Accordingly, when testing whether TBK1 could induce clearance of HTT inclusions by ICC, we observed no reduction in the number of HTT inclusions upon overexpression of TBK1 (Fig 3I). These results indicate that the TBK1‐induced reduction in HTT levels and aggregate formation is mediated by TBK1 kinase activity‐dependent processes that act at the level of soluble HTT or during the early stages of its oligomerization, before HTT fibrilization and inclusion formation.

It was previously shown that mutant HTT from HD mouse model‐derived cells shows less phosphorylation at S13/S16 than wild‐type HTT (Atwal et al, 2011) and that pS13 HTT levels in a mouse striatal cell HD model as well as in HD knock‐in mice are lower relative to wild‐type controls (Cariulo et al, 2019). To assess the role of phosphorylation in HTT pathology, we examined S13 phosphorylation levels in the brain of the zQ175 mouse model (Menalled et al, 2012). We extracted the detergent (Triton X‐100)‐soluble and insoluble protein fractions from 6‐month‐old homozygous zQ175 and heterozygous HD mice along with wild‐type control mice and subjected these samples to filter retardation assays and WB. We observed very low levels of soluble HTT in homozygous zQ175 mice, and there were no significant differences in the levels of soluble or pS13 HTT between control and heterozygous mice, at least as detected by WB (Fig EV3H). Analysis of the insoluble protein fractions revealed high levels of HTT in homozygous zQ175 mouse samples. Consistent with our previous observations, the mutant HTT proteins in the insoluble protein fraction were devoid of any pS13‐phosphorylated HTT (Fig EV3I). Together, these results combined with the previous observations that phosphorylation within N17 (pT3, pS13, pS16) inhibited mutant HTTex1 aggregation (Cariulo et al, 2017; Chiki et al, 2017; Deguire et al, 2018) indicate that reduced phosphorylation at these residues may facilitate HTT aggregation. In summary, our findings show that the TBK1‐induced reduction in HTT levels and aggregation is mediated by its ability to promote the clearance or prevent the aggregation of monomeric or soluble HTT species, rather than by the phosphorylation and disaggregation of HTT fibrils or inclusions.

The expression of mutant HTT has been shown to induce cytotoxicity in neuronal models of HD (Atwal et al, 2011; Arbez et al, 2017). Having shown that TBK1 overexpression reduced mutant HTTex1 aggregates in HEK293 cells, we sought to determine whether this would also lead to suppression of mutant HTTex1‐induced cytotoxicity. We used a previously established cytotoxicity (cell death) assay based on the measurement of nuclear condensation (Cummings & Schnellmann, 2004) during neuronal cell death induced by the expression of mutant HTT (Arbez et al, 2017). We co‐transfected neurons with TBK1 or a TBK1 KD variant along with 16Q or 72Q HTTex1 or HTTN586 22Q or 82Q. Consistent with our previous studies (Arbez et al, 2017), we found that HTTex1 72Q or HTTN586 82Q expression induced significant cell death as assessed by nuclear condensation, compared to HTTex1 16Q or HTTN586 22Q (Fig 4A and B). TBK1 but not TBK1 KD coexpression partially rescued HTTex1 72Q‐ and HTTN586 82Q‐induced toxicity (Fig 4A and B). We also observed a partial rescue of cell death induced by HTTex1 72Q upon TBK1 but not TBK1 KD coexpression in rat primary neuronal cultures using TUNEL assay (Fig 4C). To confirm the neuroprotection mediated by overexpression of TBK1 and the dependence on its kinase activity, we repeated the HTTN586 22Q and 82Q toxicity experiments in the presence of TBK1 kinase inhibitors. We observed that treatment with the TBK1 kinase inhibitor MRT68601 (McIver et al, 2012) blocked the neuroprotective effects induced by overexpression of TBK1 (Fig 4D). Next, we also tested whether the absence of TBK1 influences HTTex1 72Q‐induced toxicity in Tbk 1 −/− , Tnf‐α −/− knockout (Hemmi et al, 2004) mouse primary striatal neurons. We observed increased toxicity in the absence of TBK1 (Fig 4E). These findings suggest that TBK1 expression or activation may represent a viable strategy to suppress mutant HTT‐induced toxicity, whereas TBK1 inhibition may further exacerbate HTT toxicity.

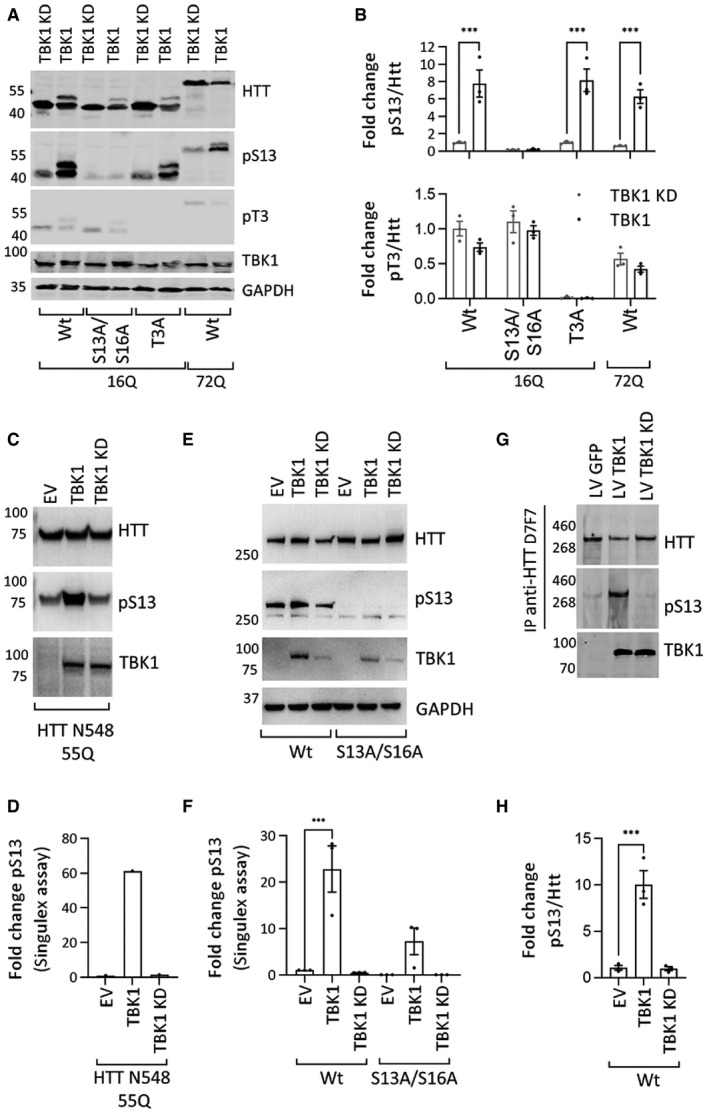

Figure 4. TBK1 expression leads to suppression of mutant HTT induced cytotoxic effects.

-

A, BQuantification of cell death by a nuclear condensation assay, cells were fixed and the nuclei were stained with Hoechst dye, and cells with a nuclear intensity higher than the average intensity plus two standard deviations are considered dead. (A) The percentage of cell death at DIV14, after co‐transfection of indicated kinases and HTTex1 plasmid in rat primary striatal neurons at DIV9 (n = 3), (B) The percentage of cell death at DIV7, after co‐transfection of indicated kinases and HTT N586 plasmid in mouse primary striatal neurons at DIV5 (n = 8).

-

CQuantification of cell death by a TUNEL assay in rat primary striatal neurons transfected with the indicated kinases at DIV9 with the indicated HTT plasmid. The cells were fixed at DIV14, and the percentage of TUNEL‐positive neurons was counted and plotted (n = 3).

-

DThe percentage of cell death, quantification by a nuclear condensation assay in mouse primary cortical neurons co‐transfected with the indicated HTT N586 and kinases at DIV5, and cells were treated with TBK1 inhibitor MRT 68601 at DIV5 till DIV7. Cells were fixed, and the nuclei were stained with Hoechst dye (n = 3). (E) Quantification of cell death by a TUNEL assay in mouse primary striatal neurons transfected with the indicated kinases at DIV9 with the indicated HTT plasmid. The cells were fixed on DIV14, and the percentage of TUNEL‐positive neurons was counted and plotted (n = 3).

TBK1 overexpression modulates HD pathology in Caenorhabditis elegans

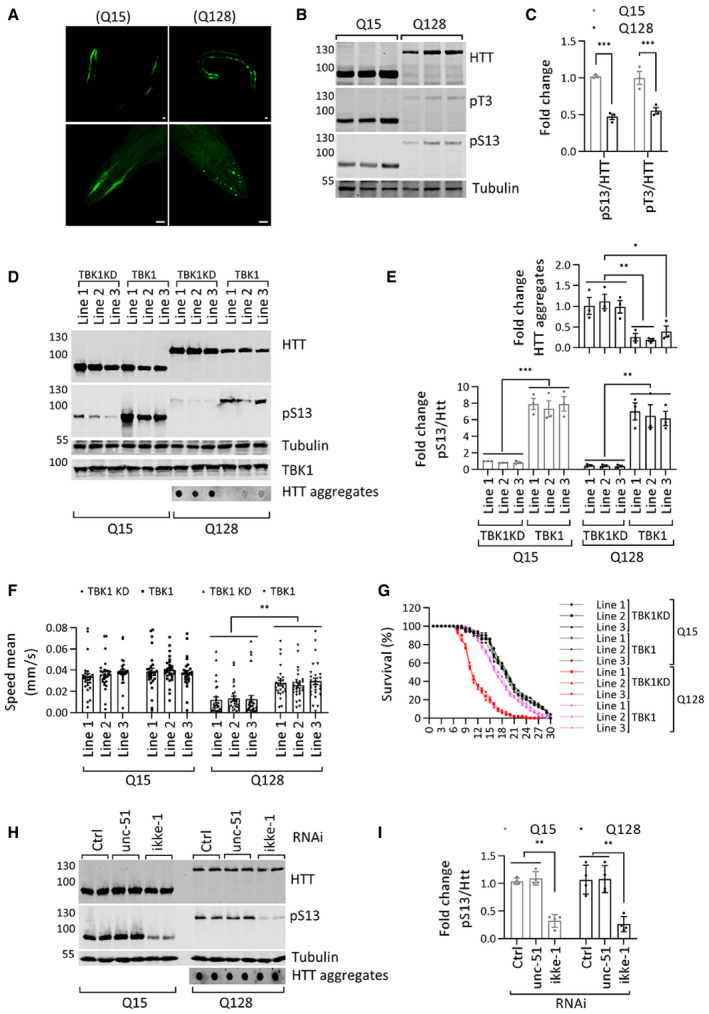

Considering the ability of TBK1 to modulate HTT levels and its propensity to form cellular inclusions, we sought to determine whether overexpression of TBK1 could prevent mutant HTT aggregation and toxicity in a recently developed C. elegans model of HD (Lee et al, 2017). This model expresses the HTT N‐terminal fragment up to residue 513 with 15 (Q15) or 128 glutamines (Q128) tagged with YFP in the muscle cells of the C. elegans body wall. In worms expressing HTTN513‐YFP (Q15), HTT appeared soluble and diffusely localized to the cytosol, whereas HTT aggregates could be readily detected in the cytosol of the worms expressing mutant HTTN513‐YFP (Q128) (Fig 5A). Using these in vivo models, we investigated the effect of TBK1 on mutant HTTN513 aggregation and toxicity. First, we assessed whether the N17 of HTTN513 was endogenously phosphorylated in C. elegans. To this end, we performed a biochemical analysis of protein lysates from this model with phospho‐specific antibodies against HTT S13 and T3. We observed that worms expressing mutant HTTN513‐YFP (Q128) showed less phosphorylation at T3 and S13 compared to worms expressing wild‐type HTTN513‐YFP (Q15) (Fig 5B and C), consistent with previous findings in animal models of HD and patient‐derived cells (Aiken et al, 2009; Atwal et al, 2011; Cariulo et al, 2017, 2019). Importantly, the detection of pT3 and pS13 HTT in C. elegans indicates that this organism expresses kinases capable of phosphorylating HTT at these residues.

Figure 5. TBK1 overexpression modulates HD pathology in C. elegans .

- Representative immunofluorescence image of C. elegans overexpressing HTT N513 Q15 and HTT N513 Q128 (scale bar 20 μm). Top panel complete worm, lower panel head region.

- Western blot showing HTT (ab‐MAB5492), HTT pS13 (ab‐CHDI-90001039‐1), and HTT pT3 (ab‐CHDI-90001528‐1) levels in C. elegans overexpressing HTT N513 Q15 and HTT N513 Q128.

- Quantification of the fold changes in ratios of HTT pS13 and pT3 to total HTT in C. elegans overexpressing HTT N513 Q15 and HTT N513 Q128 from the experiments like in B (n = 3).

- Representative Western blots showing the HTT (ab‐MAB5492) and HTT pS13 (ab‐CHDI-90001039‐1) levels from the detergent soluble fraction and HTT aggregates (ab‐MAB5492) from the detergent‐insoluble fraction in three different transgenic C. elegans lines overexpressing TBK1 or the TBK1 KD.

- The bottom graph indicates the fold change in the HTT pS13 (ab‐CHDI-90001039‐1) ratios to total HTT (ab‐MAB5492) compared to those in the kinase‐dead mutant line 1 from the experiments like in D. The top graph indicates the fold change in HTT aggregates (ab‐MAB5492) compared to that in the kinase‐dead mutant the experiments like in D (n = 3).

- Mobility of the Q15 and Q128 C. elegans lines upon overexpression of TBK1 or TBK1 KD (n = 26–29).

- Survival graph of the Q15 and Q128 C. elegans lines upon overexpression of TBK1 or TBK1 KD (n = 30).

- Representative Western blots showing HTT (ab‐MAB5492) and HTT pS13 (ab‐CHDI-90001039‐1) from the detergent soluble fraction and HTT aggregates (ab‐MAB5492) from the detergent‐insoluble fraction in TBK1 orthologue (ikke‐1 or unc‐51) RNAi‐treated C. elegans lines expressing HTT N513 Q15 and HTT N513 Q128.

- Quantification of the fold change in the ratio of pS13 HTT to total HTT compared to non‐targeting RNAi from the experiments like in H (n = 4).

Approximately 81% of human kinases have orthologues in C. elegans (Manning, 2005; Lehmann et al, 2013). It was previously shown that transgenic overexpression of human kinases in C. elegans could be used to determine their effects on pathogenic disease mechanisms (Miyasaka et al, 2005; Branco‐Santos et al, 2017). Therefore, we sought to determine the effect of the expression of human TBK1 in the muscle cells of the C. elegans HD model on HTTN513 phosphorylation, protein levels, and aggregation. We generated three different transgenic lines of HTTN513‐YFP (Q15) and HTTN513‐YFP (Q128) worms overexpressing TBK1 or TBK1 KD (fivefold to 15‐fold) and quantified HTT levels, phosphorylation at S13, aggregate load, and worm motility, a functional phenotype affected by polyQ expansion in HTT (Lee et al, 2017). As shown in Fig 5D and E, we observed that all three lines of worms overexpressing TBK1 but not TBK1 KD showed increased phosphorylation of HTTN513‐YFP at S13 in both the Q15 and Q128 models, with significantly reduced aggregate formation in the three different transgenic lines of the HTT513‐YFP (Q128) model.

Expression of HTTex1 or HTTN513 with expanded polyQ in C. elegans muscle cells in the body wall leads to aggregation‐related cytotoxicity, resulting in motility defects (Wang et al, 2006; Lee et al, 2017). Moreover, the HTTN513‐YFP (Q128) C. elegans model was shown to exhibit sustained mutant HTT‐mediated toxicity and motility defects irrespective of the age of the worms (Lee et al, 2017). Therefore, we next assessed the effect of TBK1 on mutant HTT‐induced toxicity and motility defects in this model. We examined the motility of HTTN513‐YFP Q15 and Q128 worms coexpressing TBK1 or TBK1 KD in three transgenic lines. As shown in Fig 5F, there was no significant difference in motility between worms coexpressing TBK1 or TBK1 KD with HTTN513‐YFP (Q15). In contrast, the motility defect observed in worms expressing HTTN513‐YFP (Q128) was significantly rescued upon coexpression of TBK1 but not the TBK1 KD mutant (Fig 5F). These results suggest that TBK1 coexpression suppresses mutant HTT‐induced toxicity.

Overexpression of HTTN513 Q128 within muscle cells in the body wall of C. elegans was shown to impair their muscle function and shorten their lifespan (Lee et al, 2017). Therefore, we examined the lifespan of HTT N513 Q15 and Q128 worms coexpressing TBK1 or TBK1 KD in three different transgenic lines. As shown in Fig 5G, all three lines coexpressing TBK1 KD with HTTN513‐YFP (Q128) displayed a shortened lifespan (mean lifespan of ~10 days) compared to that of three different lines coexpressing TBK1 KD with HTTN513‐YFP (Q15) (mean lifespan of ~19 days). We observed that coexpressing TBK1 in HTTN513‐YFP (Q128) worms suppressed the lifespan defect in all three lines (mean lifespan of ~17 days) (Fig 5G). These results show that TBK1 overexpression led to a significant reduction in mutant HTT aggregation and rescued mutant HTT‐induced toxicity in C. elegans.

Next, we asked whether worm orthologues of TBK1 were involved in phosphorylating HTT at residue S13 in worms. Therefore, we tested the effect of downregulating the activity of the worm orthologues of TBK1 on HTT phosphorylation and aggregation. The worms were fed siRNAs targeting the TBK1 orthologues ikke‐1 and unc‐51 for 5–6 days. RT–PCR analysis of RNA from treated animals showed an efficient knockdown of their target kinases (Appendix Fig S2). We observed that knockdown of ikke‐1 decreased pS13 levels in HTTN513‐YFP (Q15) and HTTN513 ‐YFP (Q128) worms (Fig 5H and I) but had no significant effect on the levels of total HTT or HTT aggregates in the Q128‐expressing model. These findings suggest that at least one of the C. elegans TBK1 orthologues, namely ikke‐1, contributes to pS13 HTT levels in these transgenic animals, thus further validating TBK1 as one of the kinases regulating phosphorylation of HTT at S13 in vivo.

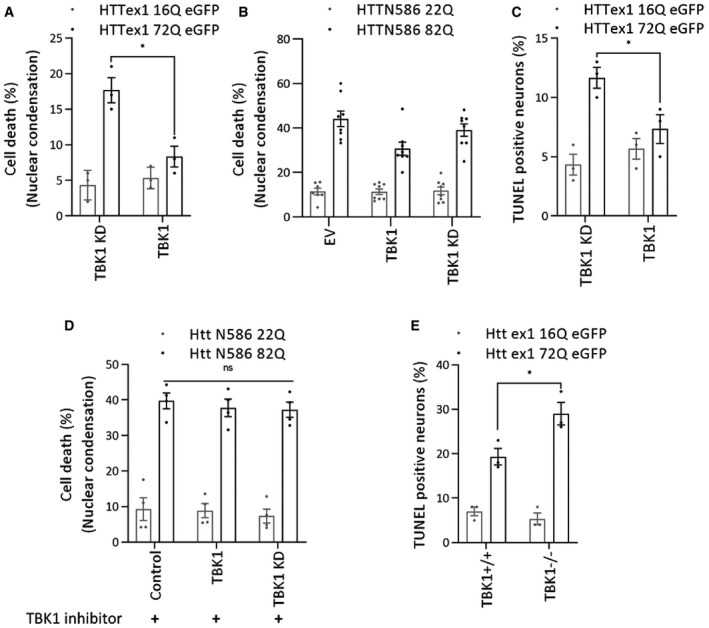

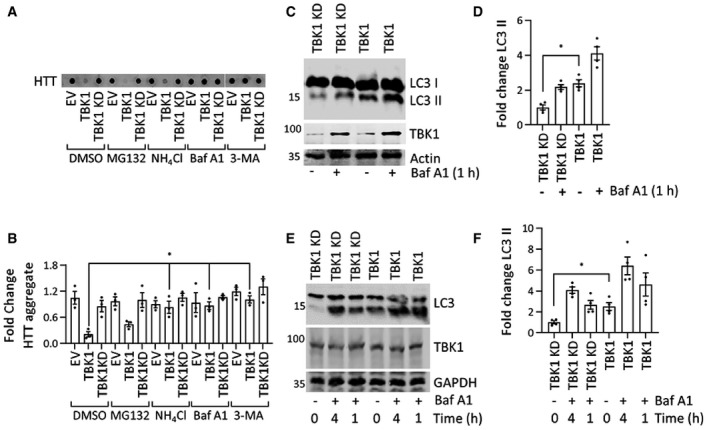

TBK1‐induced reduction of HTTex1 72Q aggregates is dependent on autophagy

Our observation that TBK1 overexpression resulted in the reduction of HTTex1 levels and inclusion formation, independent of its ability to phosphorylate the protein suggests that TBK1 plays a role in regulating the degradation of soluble HTT. TBK1 is known to play key roles in autophagy, including the phosphorylation of several autophagy adaptors, which enhances their ability to engage LC3‐II and ubiquitinated cargo (Weidberg et al, 2011; Kiriyama & Nochi, 2015; Ahmad et al, 2016; Richter et al, 2016) and to promote autophagosome maturation (Pilli et al, 2012; Oakes et al, 2017). To determine whether the TBK1‐induced reduction in HTT levels was mediated by proteasome‐ or autophagy‐related mechanisms, we assessed the effects of proteasome and autophagy inhibitors on HTT levels and aggregation in HEK293 cells coexpressing HTTex1 72Q with TBK1 or a TBK1 KD mutant. As shown in Fig 6A and B, we observed that autophagy/lysosome inhibitors but not proteasome inhibitor blocked the TBK1‐mediated reduction of both soluble and aggregated forms of HTTex1 72Q (Fig EV4A).

Figure 6. Autophagy inhibition blocks the HTTex1 72Q aggregate‐reducing effect of TBK1.

- Representative immunoblot of a filter retardation of HTT (ab‐MAB5492) from the insoluble cellular fraction; HEK293 cells coexpressed HTTex1 72Q eGFP and TBK1 or TBK1 KD for 48 h, and for the last 16 h, they were treated with the indicated proteasome inhibitor (MG132, 5 μM) or autophagy inhibitor (Baf A1, 200 nM, NH4Cl, 10 mM, 3‐MA,5 mM).

- Quantification of the fold change in HTT aggregates compared to TBK1 KD treated with DMSO from the blots like in A (n = 3).

- Immunoblot of LC3 (ab48394) from soluble HEK293 cellular fractions overexpressing TBK1 or TBK1 KD for 24 h; for the last hour, Baf A1 (500 nM) was added as indicated.

- Fold change in LC3‐II levels (lower band) relative to the respective untreated kinase‐dead mutant normalized to actin from the blots like in C (n = 3).

- Immunoblot of LC3 (ab48394) from soluble rat primary neuronal cells overexpressing lentivirus‐mediated TBK1 and TBK1 KD for 96 h. For the last 1 or 4 h, Baf A1 (500 nM) was added as indicated.

- Quantification of the fold change in LC3‐II levels (lower band) compared to the kinase‐dead mutant, which was untreated, normalized to GAPDH from the blots like in E (n = 3).

Figure EV4. (Related to Figs 6 and 7): TBK1 overexpression regulates autophagy.

-

ARepresentative immunoblot of soluble HTT (ab‐MAB5492) and HTT pS13 (ab‐CHDI-90001039‐1) from the HEK293 cellular fraction, cells were coexpressing HTTex1 72Q eGFP and TBK1 or TBK1 KD for 48 h, and for the last 16 h, they were treated with indicated proteasome inhibitor (MG132,5μM) or autophagy inhibitors (Baf‐A, 200 nM; NH4Cl, 10 mM; 3‐MA, 5 mM). Quantification of the fold change of HTT from the soluble fraction compared to TBK1 KD treated with DMSO normalized to GAPDH from the blots (n = 3).

-

BRepresentative immunoblot of p62 from soluble fraction HEK293 cells overexpressing TBK1 or TBK1 KD for 24 h, and cells were treated for last 1 or 4 h before cell lysis with Baf A1 (500 nM) as indicated.

-

CQuantification of the fold change p62 compared to untreated TBK1 KD at time 0 normalized to GAPDH from the experiments like in B (n = 3).

-

DRepresentative immunoblot of p62 from soluble rat primary striatal cellular fraction overexpressing TBK1 or TBK1 KD for 5 days, and cells were treated for last 1 or 4 h before cell lysis with Baf A1 (500 nM) as indicated.

-

EQuantification graph of the fold change p62 compared to untreated TBK1 KD at time 0 normalized to GAPDH from the experiments like in D (n = 3).

-

F–IRepresentative immunofluorescence image showing the colocalization of TBK1 with LC3 (F), ubiquitin (G), HTT (H), and p62 (I) in rat primary striatal cells at DIV14 (scale bar 5 μm). Arrows indicate the colocalizing puncta.

-

JRepresentative Western blot of phospho‐OPTN, phospho‐p62, and LC3 from HEK293 cells coexpressing HTTex1 72Q eGFP and TBK1 KD, TBK1, or TBK1 Δ 690–713 for 48 h.

To determine whether TBK1 overexpression could increase autophagy, we overexpressed TBK1 or TBK1 KD in HEK293 cells and primary neuronal cells and assessed the autophagic flux by monitoring changes in the levels of LC3B (Klionsky et al, 2016) in the cell lysates. We observed that TBK1 expression increased LC3B‐II levels compared to TBK1 KD (Fig 6C and D). Bafilomycin A1 treatment resulted in a further increase in LC3B‐II levels, consistent with this kinase's ability to increase autophagy (Fig 6C and D). An increase in autophagic flux is usually accompanied by increased clearance of the autophagy receptor p62 (Klionsky et al, 2016). Hence, we assessed p62 levels in TBK1 and TBK1 KD‐expressing HEK293 cells and observed a significant decrease in p62 levels upon TBK1 overexpression compared to TBK1 KD (Fig EV4B and C). In primary striatal neuronal cultures, the expression of TBK1, but not TBK1 KD, resulted in a significant increase in LC3B‐II levels (Fig 6E and F), with an associated decrease in p62 levels (Fig EV4D and E), indicating that TBK1 overexpression could increase autophagy in neuronal cells in a catalytic activity‐dependent manner.

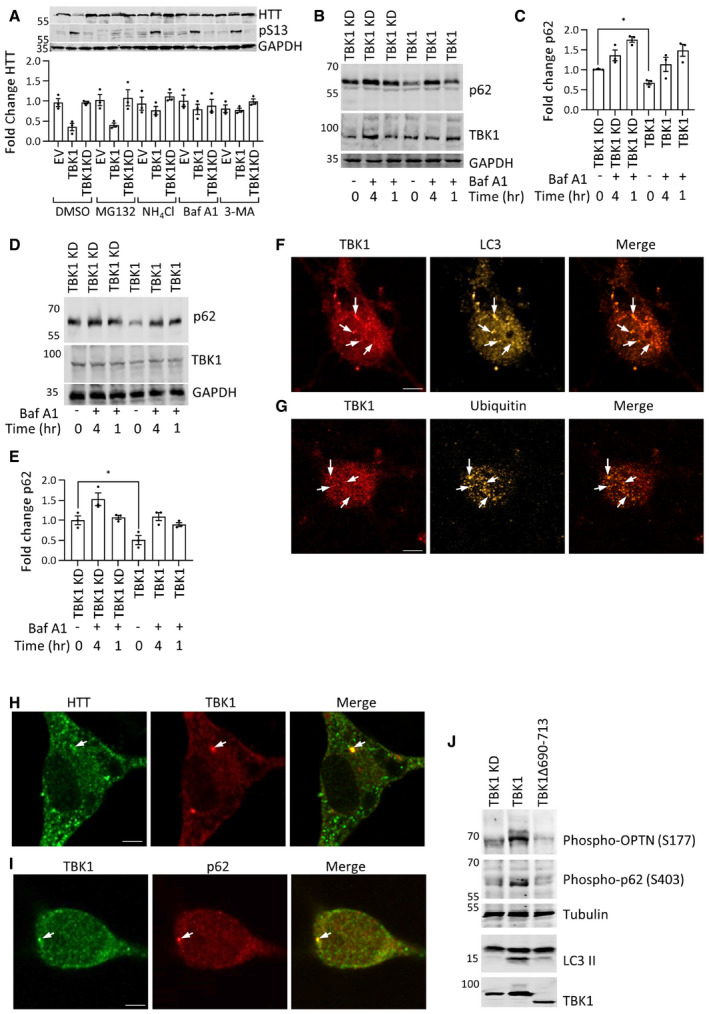

TBK1 was reported to phosphorylate the autophagy receptors optineurin (OPTN) and p62 (SQSTM1), ubiquilin‐2, and the autophagy regulator RAB8B (Richter et al, 2016). Once phosphorylated, autophagy adaptors bind to ubiquitinated substrates and target these substrates for autophagy (Richter et al, 2016; Oakes et al, 2017). To validate the observed TBK1‐mediated autophagy‐inducing effects, we assessed whether HTT, TBK1, and autophagy adaptors co‐localize in primary neurons by immunocytochemistry. We observed that endogenous, active TBK1 (phospho‐serine 172; Richter et al, 2016) co‐localized with HTT, LC3B, and ubiquitin in a subpopulation of punctate structures (Fig EV4F and G). We also observed that active TBK1 co‐localized with the autophagy adaptor p62 in a few puncta in the cytosol (Fig EV4H and I). Taken together, our data suggest that TBK1 expression promotes the general cellular clearance mechanism of soluble HTT and prevents its accumulation and aggregation by enhancing autophagy.

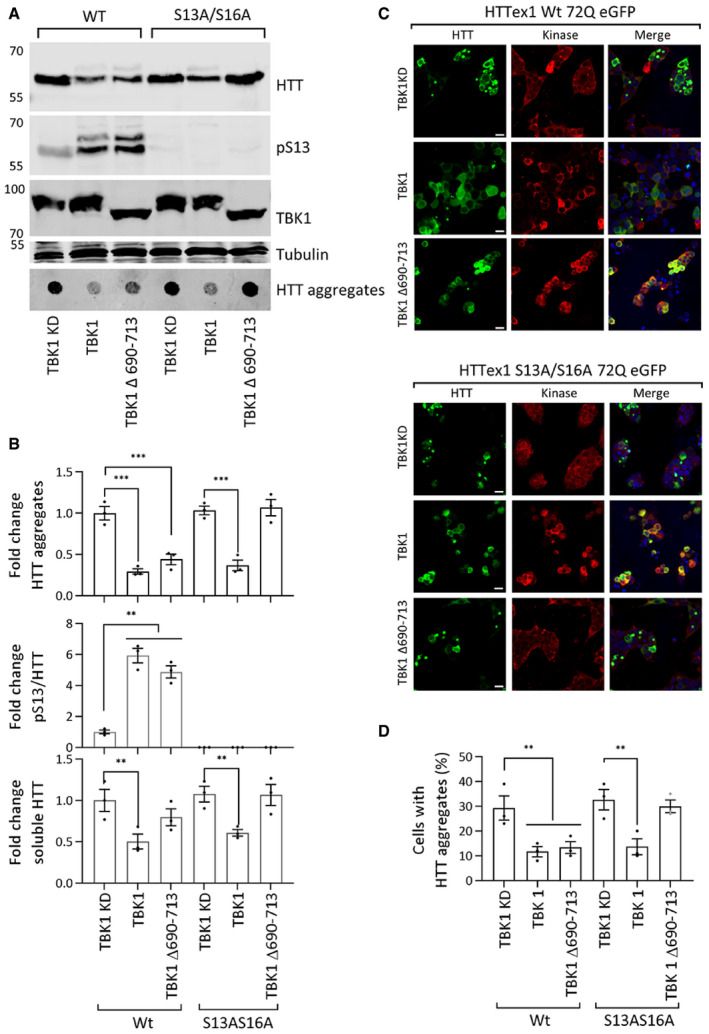

Upon disruption of TBK1 binding to autophagy adaptor proteins, its effects on HTT levels and aggregate formation become strongly dependent on the phosphorylation state of HTT

To uncouple the effects of phosphorylation‐dependent changes and TBK1‐induced enhancement of autophagy on HTT turnover and aggregation, we investigated the effect of expressing a well characterized TBK1 mutant that is incapable of binding to autophagy adaptors (lacking amino acids 690–713, within the coiled‐coil domain; Oakes et al, 2017). It has been shown that Δ690–713 TBK1 mutant could still phosphorylate known substrates, such as IRF3 (Freischmidt et al, 2015, 2017). Next, we examined the effects of the expression of TBK1 Δ690–713, TBK1 wild type, or TBK1 KD on the levels and aggregation of phosphorylation‐competent and phosphorylation‐deficient S13A/S16A mutant HTTex1 72Q in HEK293 cells. Fig 7A and B shows that both TBK1 Δ690–713 and TBK1 wild type could phosphorylate HTTex1 72Q resulting in a significant reduction in HTTex1 72Q aggregates. However, blocking phosphorylation at S13 and S16 prevented the ability of TBK1 Δ690–713 to reduce HTTex1 72Q aggregation (Fig 7A–D). Unlike wild‐type TBK1, coexpression of TBK1 Δ690–713 had minimal effects on the levels of soluble HTT. These results indicate that the TBK1‐mediated reduction of mutant HTT aggregates was dependent on its autophagy adaptor‐binding function and this mechanism was the primary contributor to the phosphorylation‐independent reduction of HTT aggregates upon coexpression of TBK1. The removal of the 690–713 region interfered with the ability of TBK1 to phosphorylate p62 and OPTN, and its ability to activate autophagic flux (Fig EV4J). Under these conditions, TBK1 mediated effect on HTT aggregation was dependent on the phosphorylation state of HTT at S13/S16. Importantly, these data show that phosphorylation at S13 was sufficient to prevent mutant HTT aggregation in the absence of TBK1 mediated enhancement of autophagy and lowering of mutant HTTex1 levels. These results are consistent with our recent in vitro studies (Deguire et al, 2018) and previous studies using phosphomimetics (S13D/S16D) in a mouse model of HD (Gu et al, 2009) and cell lines (Thompson et al, 2009; Atwal et al, 2011; Branco‐Santos et al, 2017).

Figure 7. TBK1 deficient in the autophagy adaptor‐binding domain does not reduce HTTex1 72Q eGFP S13A/S16A aggregates.

- Western blot of soluble HTT (ab‐MAB5492), HTT pS13 (ab‐CHDI-90001039‐1), and HTT aggregates (ab‐MAB5492), upon coexpression of the HTTex1 72Q eGFP or HTTex1 72Q eGFP S13A/S16A variant with TBK1 KD, TBK1, or TBK1 Δ690–713 for 48 h in HEK293 cells.

- The graph indicates the calculated fold changes in HTT, HTT pS13 ratio to total HTT, and HTT aggregates all compared to the levels in TBK1 KD from the experiments like in A (bottom panel normalized to tubulin, n = 3).

- Representative immunofluorescence images of eGFP HTTex1 72Q or its phosphorylation‐deficient variant S13A/S16A upon coexpression with TBK1 KD or TBK1 or TBK1 Δ690–713 (ab-anti‐Myc) with for 48 h in HEK293 cells (scale bar 20 μm).

- The graph indicates the percentage of co‐transfected cells presenting aggregates upon expression of the indicated kinase, from the experiments like in C (n = 3).

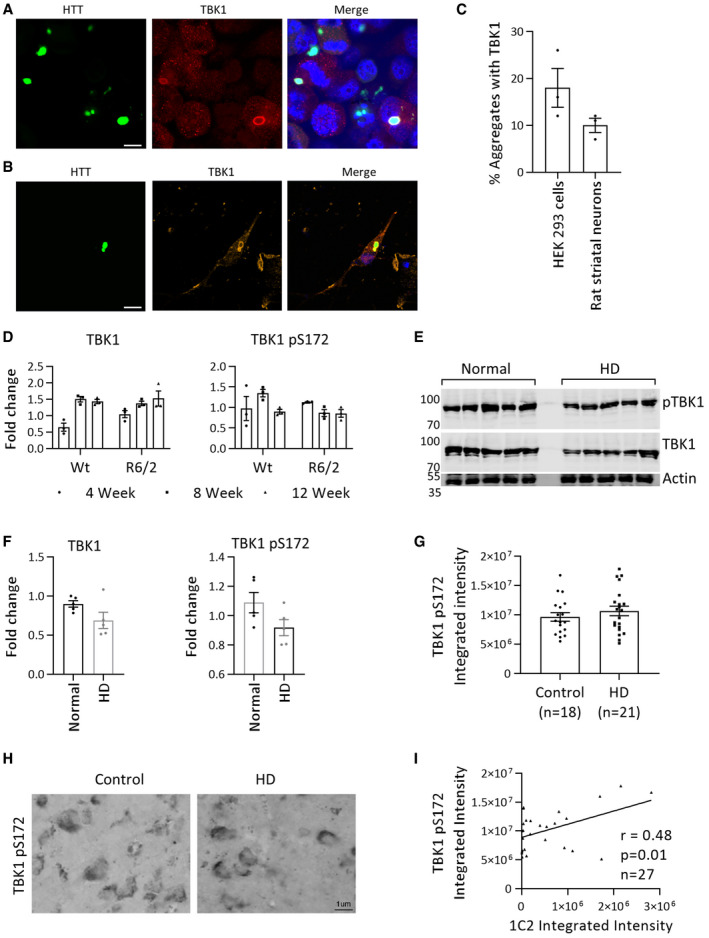

TBK1 levels are not altered in R6/2 transgenic HD mouse model and HD patients brain

To determine whether the levels of TBK1 are altered in HD and HD models, we examined the levels of active TBK1 (phospho S172 = pS172) and total TBK1 in R6/2 transgenic HD mouse model, human postmortem brain tissues, and in HD patient brain tissue microarray (active TBK1 pS172). We observed no change in TBK1 or TBK1 pS172 levels in R6/2 transgenic HD mouse brain tissue lysates at time points up to 12 weeks (4, 8, 12 weeks) compared to age‐matched wild type (Fig EV5D). Next, we obtained five HD and five non‐HD postmortem cortical brain tissues and analyzed TBK1 level. We observed a trend of decrease in both the total and active TBK1 levels in these tissues, which was not statistically significant (Fig EV5E and F). This led us to examine the levels of both TBK1 and active TBK1 in a larger set of human samples. For this, we chose to use the tissue microarray approach. As shown in Fig EV5G and H, we did not observe any significant changes in active TBK1 pS172 levels in 21 HD samples compared with 18 control samples from the middle temporal gyrus tissue microarray (total TBK1 antibody was not suitable for immunohistochemistry on paraffin tissue microarrays). Moreover, there was no apparent correlation between the expression levels of active TBK1 and HTT stained by TBK1 pS172 and HTT 1C2 antibodies, respectively (Fig EV5I). These results suggest TBK1 levels may not be drastically changed in HD cases.

Figure EV5. (Related to discussion): TBK1 levels are not affected in HD models and HD patient brain tissue.

- Representative immunofluorescence image showing the localization of TBK1 with HTTex1 72Q eGFP in HEK293 cells after 48 h of co‐transfection (scale bar 10 μm).

- Representative immunofluorescence image showing the localization of TBK1 with HTTex1 72Q eGFP in rat primary striatal cells at DIV14 after 5 days of co‐transfection (scale bar 10 μm).

- Quantification of TBK1‐positive aggregates in HEK293 cells and rat primary striatal cells from immunofluorescence images similar to those in A and B (n = 3).

- Quantification of the fold changes in TBK1 and pS172 TBK1 from control and R6/2 brain lysates at 4, 8, and 12 weeks of age compared to Wt 4‐week control normalized to HSP90 (n = 3 per group).

- Representative Western blot showing TBK1 or pTBK1 from postmortem cortical tissue from normal controls and HD patients.

- Quantification of the fold changes in TBK1 and pS172 TBK1 compared to the first normal tissue normalized to actin from E (n = 5 per group).

- Quantification of the expression (integrated intensity) of TBK1 pS172 immunoreactivity from middle temporal gyrus tissue microarray containing n = 18 control and n = 21 HD postmortem tissue samples.

- Representative images of control and HD postmortem tissue showing TBK1 pS172 immunoreactivity from middle temporal gyrus tissue microarray.

- Graph comparing the integrated intensities of TBK1 pS172 and HTT polyQ‐specific 1C2 immunostaining from middle temporal gyrus tissue microarray of HD and control cases.

Discussion

Increasing evidence from in vitro, cellular, and animal model studies show that phosphorylation or mimicking phosphorylation at S13 and/or S16 attenuates mutant HTT aggregation and toxicity (Thompson et al, 2009; Atwal et al, 2011; Arbez et al, 2017; Branco‐Santos et al, 2017; Deguire et al, 2018). However, whether inhibiting mutant HTT aggregation is the primary mechanism underlying the protective effects of phosphorylation at these residues remains unknown. This is in part because the majority of previous studies aimed at dissecting the role of S13/S16 phosphorylation in cellular and animal models were based primarily on approaches relying on the use of mutations to mimic or block phosphorylation, rather than bona fide phosphorylation and thus did not account for the dynamic nature of phosphorylation. To address this knowledge gap and elucidate the role of phosphorylation at S13 and S16 in HTT aggregation, turnover, and toxicity, we set out to identify kinases capable of increasing S13 HTT phosphorylation and identified TBK1 kinase.

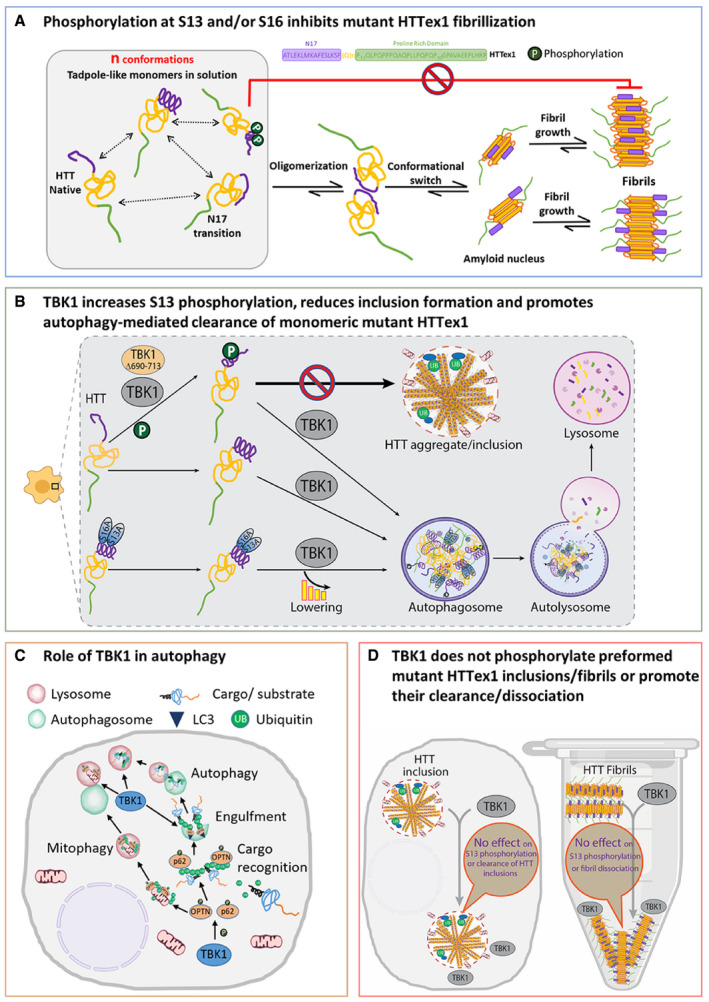

Herein, we showed that TBK1 co‐incubation with wild‐type or mutant HTTex1 or longer N‐terminal HTT fragments resulted in phosphorylation of both S13 and S16 (Figs 1C and EV1A and B). In contrast to IKKβ, which was shown previously to preferentially phosphorylate wild‐type HTTex1 at residue S13 (Thompson et al, 2009). In our hands, IKKβ phosphorylated both S13 and S16, although much less efficiently than TBK1 (Fig EV2A and B). TBK1 possesses robust autophosphorylation and dimerization capacity (Oakes et al, 2017) that may lead to its high activation compared to IKKβ, which requires two other subunits for its full activation. This could also be one reason for the observed difference in the efficiency of the two kinases toward HTT S13 phosphorylation in vitro. TBK1 coexpression/overexpression robustly and efficiently increased S13 phosphorylation of both wild‐type and mutant HTT in cells by approximately 5‐fold to 10‐fold compared to 3‐fold to 4‐fold by IKKβ (Fig 1D and E) and led to stronger HTT‐lowering effects, especially for mutant HTTex1. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating that HTT is a substrate of TBK1. The discovery of TBK1 provides an efficient tool for manipulating HTT phosphorylation levels in cells and enabled us to systematically determine how modulating phosphorylation at these residues influence HTT aggregation (Fig 8A), clearance, and toxicity in different models of HD.

Figure 8. Schema of the effect of HTT phosphorylation and TBK1 on aggregation.

- Effect of S13 and/or S16 phosphorylation on HTTex1 aggregation. HTTex1 forms a tadpole‐like monomer structure, and N17‐driven interaction may further drive HTTex1 oligomerization and fibril formation. Phosphorylation at S13 and S16 destabilizes the helix at N17 that leads to inhibition of the formation of HTTex1 fibrils.

- Effect of TBK1 on HTT in the cellular HD model. TBK1 and TBK1 Δ690–713 both phosphorylate monomeric or soluble HTTex1 72Q at S13 residue leading the reduction of the aggregation, but TBK1 also reduces the aggregation of both HTTex1 and HTTex1 S13A/S16A through the lowering of the HTT levels at the monomeric stage by enhancing the autophagic degradation. TBK1 Δ690–713 only reduces the aggregation of phosphorylation‐competent HTTex1 but does not reduce the aggregation of HTTex1 S13A/S16A highlighting the role of S13 phosphorylation in aggregation inhibition.

- TBK1 effects on different stages of autophagy. TBK1 is known to phosphorylate autophagy adaptors p62 and OPTN that bind ubiquitinated substrates like proteins or damaged mitochondria and recruit LC3 and increase the autophagic clearance of substrates.

- TBK1 does not phosphorylate HTTex1 in inclusion/fibrils or promote their clearance/disaggregation. When HTT was already aggregated in cells or when in fibril form in vitro, possibly S13 residue is not accessible for TBK1 phosphorylation as N17 was shown to be collapsed on fibrillar core or it is near the core. Also, TBK1‐mediated autophagy flux was not able to induce the lowering of HTTex1 inclusion. There was no disaggregation of fibrils up on TBK1 kinase in vitro.

TBK1 regulates the autophagy‐mediated clearance of monomeric HTT

Our results demonstrate that TBK1 modifies HTT aggregation and toxicity through autophagy‐mediated regulation of HTT clearance. TBK1 overexpression in cells reduced the levels of soluble HTTex1 and prevented the accumulation of mutant HTTex1 inclusions in a kinase activity‐dependent manner, whereas TBK1 knockdown, knockout, or inhibition resulted in increased HTT levels. These observations suggest that TBK1 regulates mutant HTT levels and inclusion formation by activating clearance mechanisms such as proteasome‐ or autophagy‐mediated protein clearance.

TBK1 levels and activity have been implicated in regulating many aspects of autophagy. For example, TBK1 gene duplication in human iPSC‐derived retinal cells or overexpression of TBK1 in RAW264.7 cells lead to increased LC3II and increased autophagy (Pilli et al, 2012; Ritch et al, 2014). TBK1‐mediated phosphorylation of the autophagy adaptor proteins OPTN and p62 represents a rate‐limiting step in the autophagic degradation of misfolded protein aggregates. Several studies have also shown that TBK1 acts as a scaffolding protein and plays an important role in regulating autophagic activity by regulating protein targeting to autophagosomes, autophagosome formation, autophagosome engulfment of substrates (Matsumoto et al, 2011; Korac et al, 2013), and fusion of autophagosomes to autolysosomes (Pilli et al, 2012). TBK1 depletion negatively impacts all of these processes and causes decreased autophagic activity (Oakes et al, 2017). Defects in autophagy and autophagosome formation and clearance have been implicated in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases (Nixon, 2013; Scrivo et al, 2018).

Consistent with its role in autophagy (Oakes et al, 2017), we observed that TBK1 was localized surrounding the HTTex1 inclusions in HEK293 cells and rat striatal primary neurons (Fig EV5A–C). TBK1 overexpression in HEK293 cells led to an increase in autophagic flux and the phosphorylation of the autophagy adaptors OPTN and p62 (Fig EV4J). To determine whether TBK1‐mediated enhanced clearance or reduced aggregation of HTT was due to its interaction with and/or phosphorylation of HTT monomers, aggregates or both, we assessed the effect of TBK1 overexpression on HTT levels and aggregation in different HD models. Interestingly, we observed that TBK1‐mediated reduction in HTT levels and aggregation were strongly dependent on TBK1 kinase activity and its ability to bind to the autophagy adaptor OPTN, but occurred independently of phosphorylation at S13 (Fig 8B). However, upon disruption of TBK1 interactions with the autophagy adaptors OPTN and p62, the effects of TBK1 on HTT levels and aggregation became strongly dependent on both its kinase activity and HTT phosphorylation at S13. These findings suggest that the primary mechanism underlying the beneficial effects of TBK1 is mediated by its ability to enhance autophagy, possibly through phosphorylation of the autophagy adaptors OPTN and p62 (Fig 8C). Preliminary studies from our group (Maharjan et al, unpublished) investigating the PTM‐dependent interactome of soluble monomeric HTT showed that phosphorylation at S13 and S16 promoted interactions between mutant HTT and many autophagy, folding, and endocytic pathway components, suggesting that phosphorylation at these residues could also regulate HTT levels by promoting its interactions with key mediators of cellular proteostasis mechanisms. The proposed role of HTT as an autophagy scaffold protein (Ochaba et al, 2014) is also consistent with this hypothesis.

The aggregation inhibitory and protective effects of TBK1‐mediated phosphorylation at S13 are consistent with previous findings demonstrating that reduction of HTT S13 phosphorylation by IKKβ knockout in striatum resulted in a significant increase in HTT levels in wild‐type or R6/1 HD mouse (Ochaba et al, 2019) and further enhanced the behavior defect and increased neurodegeneration and microglial activation in R6/1 mice. We also previously showed that phosphorylation of mutant HTT at S13/S16 significantly reduced the helical propensity of N17 and the rate and extent of HTTex1 aggregation in vitro (Deguire et al, 2018). Together, these observations further support the hypothesis that enhancing phosphorylation at S13 is sufficient to induce a significant reduction in HTT levels, aggregation, and inclusion formation.

TBK1 does not phosphorylate or reduce preformed HTT aggregates or inclusions

Interestingly, TBK1 does not phosphorylate mutant HTTex1 fibrils in vitro or HTT in cellular inclusions and overexpression of TBK1 does not result in the clearance of mutant HTT aggregates once they were formed (Fig 8D). Whether TBK1 promotes the clearance of HTT monomers, oliogomers or both remains unknown. Unfortunately, the existing models of HTT aggregation and inclusion formation did not allow for investigating the effect of TBK1‐mediated phosphorylation on early aggregation events and its effect on HTT oligomerization. HTT oligomers are usually short‐lived and difficult to monitor and isolate from cells. Therefore, further studies are required to determine whether TBK1 acts on pre‐fibrillar/inclusions intermediates and promote their autophagic clearance. Our observation that TBK1 was not able to induce the clearance of HTT post‐aggregation is consistent with previous studies showing that autophagy induction by rapamycin treatment had no effect on the levels of HTT aggregates once mature aggregates were formed but reduced HTT aggregate formation and cell death when applied at the earlier stages of the aggregation process (Ravikumar et al, 2002). Together, these findings suggest that the beneficial effects of TBK1 are mediated by its activity‐dependent regulation of the phosphorylation and degradation of monomeric or soluble forms, but not aggregated forms of HTT.

These observations also suggest that the N17 domain adopts a different conformation in the aggregated state of mutant HTT and/or that TBK1 does not interact with aggregated forms of HTT. Indeed, previous solid‐state NMR studies on HTTex1 fibrils showed that N17 was less mobile and engaged in interactions with the amyloid core or PRD domain in the fibrillar state (Fig 8A; Bugg et al, 2012; Lin et al, 2017). The inaccessibility of N17 in the fibril state suggests that post‐aggregation phosphorylation or potentially other PTMs in the N17 domain N17 are less likely to occur post‐aggregation (Fig 8D). These findings imply that the N17 PTM‐dependent regulation of HTT aggregation and clearance is likely mediated by the aggregation inhibitory effects of PTMs at the monomer level or their ability to selectively target monomeric or soluble HTT species for degradation. Several lines of evidence support this hypothesis: (i) We failed to detect phosphorylation at S13 in insoluble HTT fractions and aggregates from cellular and animal models of HD, whereas phosphorylation at S13 was readily detectable in the soluble fractions; (ii) several studies reported reduced phosphorylation at T3 and S13/S16 on mutant HTT compared to wild‐type HTT in cell, mouse, and HD patient iPSC derived models (Aiken et al, 2009; Atwal et al, 2011; Cariulo et al, 2017); and 3) previous and recent studies from our group showed that the majority of the N17 modifications at the monomeric level (phosphorylation at T3, S13, S16, and S13/S16; ubiquitination; SUMOylation; methionine oxidation) inhibit mutant HTTex1 aggregation (Steffan et al, 2004; Thompson et al, 2009; Chiki et al, 2017; Deguire et al, 2018).

Therapeutic implications

The discovery of TBK1 as a kinase that efficiently phosphorylates HTT at S13 presents unique opportunities to directly assess the effect of phosphorylation at these residues and/or selective autophagic degradation of monomeric HTT as therapeutic targets for the treatment of HD. Several lines of evidence support the feasibility of these approaches: (i) Small molecules such as GM1 (Di Pardo et al, 2012) and N6‐furfuryladenine (Bowie et al, 2018) were shown to increase S13/S16 phosphorylation and restore normal motor behavior in the YAC128 HD mouse model; (ii) a BACHD mouse model expressing S13D/S16D HTT showed reduced aggregate formation and suppression of HD pathology, such as motor deficits (Gu et al, 2009); (iii) in cellular models, HTTex1 S13D/S16D levels were reduced compared to HTTex1 (Thompson et al, 2009); and (iv) our results in C. elegans showed that TBK1‐mediated increased phosphorylation at S13 resulted in a significant reduction of HTT aggregates and improved worm lifespan and motility. Furthermore, we showed that increasing TBK1 levels or activity resulted in a robust increase of HTT phosphorylation and enhancement of autophagy, leading to reduced HTT levels and suppression of HD pathology and toxicity, suggesting that targeting TBK1 represents a viable strategy for the treatment of HD.

Increasing evidence suggests that dysfunction in autophagy and other protein clearance mechanisms play central roles in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases, including HD (Nixon, 2013). HTT has also been demonstrated to function as a scaffold protein for selective macroautophagy and to promote selective autophagy through its ability to interact with p62 and ULK1 simultaneously, thus suggesting a role in both cargo recognition efficiency and autophagosome formation initiation (Ochaba et al, 2014; Rui et al, 2015). Herein, we showed that TBK1 expression/activation helped to overcome the autophagy defects induced by HTT misfolding and aggregation in HD models. Our data suggest that TBK1 expression/activation increases the phosphorylation of the cargo/substrate recognition adaptors OPTN and p62. Phosphorylation of OPTN or p62 was shown to facilitate the autophagy‐dependent clearance of damaged or dysfunctional mitochondria (Matsumoto et al, 2015; Richter et al, 2016), and misfolded proteins and aggregates of proteins linked to neurodegenerative diseases, such as mutant SOD1 (Korac et al, 2013) and HTT (Matsumoto et al, 2011). TBK1‐mediated enhancement of cargo/substrate recognition by the adaptors OPTN and p62, and OPTN mRNA levels were shown to be partially reduced in HD patient brain tissues (Hodges et al, 2006). In cellular models of HD (expressing HTTex1 103Q), OPTN knockdown led to an increase in HTT aggregation (Korac et al, 2013). Although the role of OPTN in the progression of HD is currently unknown, reducing OPTN activity or levels may confer susceptibility to HTT aggregation because of its role in autophagic clearance of protein aggregates. Therefore, pharmacological enhancement of the TBK1 pathway could activate the available pool of OPTN, which may, in turn, increase the recognition and clearance of HTT. Previous studies suggested that general autophagy induction in HD mouse models reduces aggregate load and improves motor performance and lifespan (Ravikumar et al, 2004; Tanaka et al, 2004; Rose et al, 2010). Our results suggest that TBK1 is a strong candidate for activating specific steps involved in the autophagy cascade (Fig 8D), and for the reduction of the autophagy substrates.