A novel bat alphaherpesvirus, Pteropus lylei-associated alphaherpesvirus (PLAHV), was isolated from urine of the fruit bat Pteropus lylei in Vietnam. The whole-genome sequence was determined and was predicted to include 72 open reading frames in the 144,008-bp genome. PLAHV is circulating in a species of fruit bats, Pteropus lylei, in Asia. This study expands the knowledge on bat-associated alphaherpesvirology.

KEYWORDS: bat alphaherpesvirus, Pteropus lylei, Vietnam

ABSTRACT

Herpesviruses exist in nature within each host animal. Ten herpesviruses have been isolated from bats and their biological properties reported. A novel bat alphaherpesvirus, which we propose to name “Pteropus lylei-associated alphaherpesvirus (PLAHV),” was isolated from urine of the fruit bat Pteropus lylei in Vietnam and characterized. The entire genome sequence was determined to be 144,008 bp in length and predicted to include 72 genes. PLAHV was assigned to genus Simplexvirus with other bat alphaherpesviruses isolated from pteropodid bats in Southeast Asia and Africa. The replication capacity of PLAHV in several cells was evaluated in comparison with that of herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1). PLAHV replicated better in the bat-originated cell line and less in human embryonic lung fibroblasts than HSV-1 did. PLAHV was serologically related to another bat alphaherpesvirus, Pteropodid alphaherpesvirus 1 (PtAHV1), isolated from a Pteropus hypomelanus-related bat captured in Indonesia, but not with HSV-1. PLAHV caused lethal infection in mice. PLAHV was as susceptible to acyclovir as HSV-1 was. Characterization of this new member of bat alphaherpesviruses, PLAHV, expands the knowledge on bat-associated alphaherpesvirology.

IMPORTANCE A novel bat alphaherpesvirus, Pteropus lylei-associated alphaherpesvirus (PLAHV), was isolated from urine of the fruit bat Pteropus lylei in Vietnam. The whole-genome sequence was determined and was predicted to include 72 open reading frames in the 144,008-bp genome. PLAHV is circulating in a species of fruit bats, Pteropus lylei, in Asia. This study expands the knowledge on bat-associated alphaherpesvirology.

INTRODUCTION

Herpesviruses are enveloped viruses with a double-stranded linear DNA genome ranging from 124 to 295 kbp in length (1, 2). The viral genome is encapsulated in an icosahedral protein cage called a capsid, which is surrounded by a protein layer called the tegument, and a lipid bilayer, the envelope, derived from host membrane with viral membrane glycoproteins (1, 2). Herpesviruses are widely disseminated in nature and coexist with each of their hosts, with more than 100 species making up the large order Herpesvirales (International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses [https://talk.ictvonline.org/taxonomy/]) (1, 2). Mammalian herpesviruses are assigned to the family Herpesviridae, which is subdivided into 3 subfamilies, Alphaherpesvirinae, Betaherpesvirinae, and Gammaherpesvirinae, based on biological properties and genome sequence similarities (1, 2).

Numerous species of viruses belonging to a variety of families are hosted in bats, some of which show high pathogenicity to humans and livestock and threaten global public health (3). Lyssaviruses, including rabies virus, are maintained in and geographically distributed with some species of bats and cause diseases in humans (3–5). Henipaviruses are harbored in some species of pteropodid bats and have repeatedly spilled over to livestock and humans (3–6). Other species of viruses, including filoviruses, coronaviruses, and reoviruses, have sporadically spilled over from bats and caused human infection (3–5).

Herpesviruses have been isolated from several species of bats and their characteristics have been elucidated. To date, 5 kinds of alphaherpesviruses have been isolated from 6 species of frugivorous bats: Eidolon helvum, Eidolon dupraenum, Pteropus lylei, Pteropus hypomelanus-related bat, Lonchophylla thomasi, and one unassigned species (7, 8). Two kinds of betaherpesviruses have been isolated from 2 species (Miniopterus fuliginosus and Miniopterus schreibersii) (9, 10), whereas 3 gammaherpesviruses have been isolated from 3 species of bats (Myotis velifer incautus, Eptesicus fuscus, and Rhinolophus ferrumequinum) (11–13). Whole-genome sequencing was performed on 1 alphaherpesvirus isolated from P. hypomelanus-related bat (8), one betaherpesvirus isolated from M. schreibersii (10), and 3 gammaherpesviruses (11–13). Their biological properties, such as replication capacity in cell cultures and virulence in mice, were analyzed (8, 10–12). Bat alphaherpesvirus and gammaherpesviruses could replicate in bat and other mammalian cells, but the replication of the bat betaherpesvirus was restricted in specific types of cells (8, 10–12). Infection of mice with the bat alphaherpesvirus could be lethal (8). The other 4 alphaherpesviruses and 1 betaherpesvirus were characterized for their partial gene sequences and molecular phylogeny (7, 9). The herpesvirus reports of bat origin are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Summary of the herpesviruses isolated from bats

| Reference | Sampling information |

Virus information |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Bat species | Specimen | Subfamily | Genus | Genome sequence | Accession no. | |

| Inagaki et al. (this study) | Vietnam | Pteropus lylei | Urine | Alphaherpesvirinae | Simplexvirus | Complete (144,008 bp) | LC492974.1 |

| Razafindratsimandresy et al. (7) | Madagascar | Eidolon dupraenum | Throat swab | Alphaherpesvirinae | Simplexvirus | Partial (465 bp) | FJ040879.1 |

| Cameroon | Eidolon helvum | Organs | Alphaherpesvirinae | Simplexvirus | Partial (465 bp) | FJ040890.1 | |

| Central African Republic | Unknown | Salivary gland | Alphaherpesvirinae | Simplexvirus | Partial (465 bp) | FJ040888.1 | |

| Cambodia | Pteropus lylei | Throat swab | Alphaherpesvirinae | Simplexvirus | Partial (465 bp) | FJ040877.1 | |

| Brazil | Lonchophylla thomasi | Blood | Alphaherpesvirinae | Simplexvirus | Partial (465 bp) | FJ040887.1 | |

| Sasaki et al. (8) | Indonesia | Pteropus hypomelanus-related bat | Spleen | Alphaherpesvirinae | Simplexvirus | Complete (149,459 bp) | NC_024306.1 |

| Watanabe et al. (9) | Japan | Miniopterus fuliginosus | Spleen | Betaherpesvirinae | Unassigned | Partial (5,737 bp) | AB517983.1 |

| Zhang et al. (10) | Australia | Miniopterus schreibersii | Lymph node | Betaherpesvirinae | Unassigned | Complete (222,870 bp) | JQ805139.1 |

| Shabman et al. (11) | United States | Myotis velifer incautus | Skin tumor | Gammaherpesvirinae | Unassigned | Subcomplete (129,563 bp) | KU220026.1 |

| Subudhi et al. (12) | Canada | Eptesicus fuscus | Lung | Gammaherpesvirinae | Rhadinovirus | Complete (166,748 bp) | MF385016.1 |

| Noguchi et al. (13) | Japan | Rhinolophus ferrumequinum | Spleen | Gammaherpesvirinae | Percavirus | Complete (147,790 bp) | LC333428.1 |

In the present study, the properties of the sixth bat alphaherpesvirus newly isolated from P. lylei, which we propose to name “Pteropus lylei-associated alphaherpesvirus (PLAHV),” were explored. The characteristics of PLAHV were evaluated in comparison with those of another bat alphaherpesvirus, Pteropodid alphaherpesvirus 1 (PtAHV1), isolated from P. hypomelanus-related bats inhabiting Indonesia (8), and of herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) of humans.

RESULTS

Isolation of PLAHV.

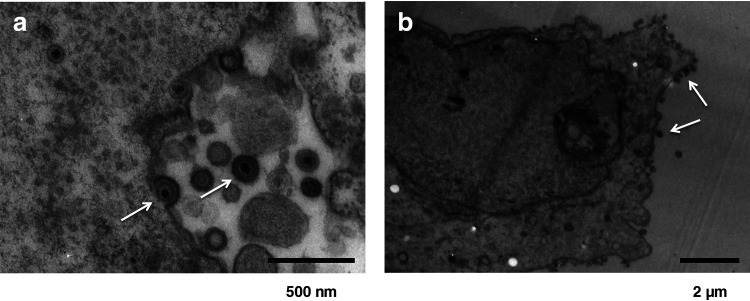

In total, 10 urine and 206 fecal samples were collected from fruit bats of P. lylei. Cytopathic effect (CPE) appeared in Vero cells inoculated with 3 of 10 urine samples but not with any fecal samples. Electron microscopy imaging revealed the capsid structure surrounded by a membrane (Fig. 1). Next-generation sequencing and a proteomics-based virus detection system detected nucleotide sequences related to herpesvirus UL30 and UL31 genes and peptide sequences related to herpesvirus UL19 and UL46 genes, respectively (Table 2 and data not shown). These CPE agents were confirmed to be a member of the herpesviruses by the whole-genome sequencing as described in next section. The single clone isolated from 1 of the 3 urine samples was established by a three-round plaque purification procedure in Vero cells.

FIG 1.

Electron microscopic appearance of PLAHV virion cultured in Vero cells. Exocytosis of virions with a diameter of approximate 160 nm (a, left arrowhead) and whole virions in a cytoplasmic vacuole (a, right arrow) are shown. The micropraph (b) shows virions possibly in the final stage of egress at the cell surface (b, arrow).

TABLE 2.

Genes predicted in the PLAHV genome

| Gene | Product | Positions | Orientationa | % amino acid sequence identity to: |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PtAHV1 | HSV-1 | ||||

| RL1 | ICP34.5 | 1405–2292 | + | 80.4 | 34.6 |

| RL2 | Ubiquitin E3 ligase; ICP0 | + | Not calculated | 17.6 | |

| Exon 1 | 3297–3686 | Not calculated | Not calculated | ||

| Exon 2 | 4936–5529 | Not calculated | Not calculated | ||

| UL1 | Envelope glycoprotein L | 7226–7933 | + | 74.6 | 36.6 |

| UL2 | Uracil-DNA glycosylase | 8328–8990 | + | 89.1 | 46.4 |

| UL3 | Nuclear protein | 9074–9742 | + | 82.9 | 53.8 |

| UL4 | Nuclear protein | 9789–10421 | − | 89.7 | 44.4 |

| UL5 | Helicase-primase helicase subunit | 10455–13076 | − | 95.1 | 78.4 |

| UL6 | Capsid portal protein | 13075–15120 | + | 94.0 | 64.1 |

| UL7 | Tegument protein | 15071–15958 | + | 92.9 | 61.1 |

| UL8 | Helicase-primase subunit | 16077–18083 | − | 77.8 | 42.8 |

| UL9 | DNA replication origin-binding helicase | 18436–20985 | − | 96.7 | 78.0 |

| UL10 | Envelope glycoprotein M | 20942–22297 | + | 94.9 | 58.3 |

| UL11 | Myristylated tegument protein | 22917–23174 | − | 88.2 | 44.8 |

| UL12 | DNase | 23099–25069 | − | 80.4 | 50.4 |

| UL13 | Tegument serine/threonine protein kinase | 25072–26619 | − | 96.7 | 66.2 |

| UL14 | Tegument protein | 26379–26891 | − | 90.6 | 49.5 |

| UL15 | DNA packaging terminase subunit 1 | + | 97.3 | 82.7 | |

| Exon 1 | 27110–28135 | Not calculated | Not calculated | ||

| Exon 2 | 31526–32701 | Not calculated | Not calculated | ||

| UL16 | Tegument protein | 28183–29274 | − | 92.9 | 57.9 |

| UL17 | DNA packaging tegument protein | 29306–31465 | − | 87.9 | 57.7 |

| UL18 | Capsid triplex subunit 2; VP23 | 32805–33761 | − | 96.2 | 78.3 |

| UL19 | Major capsid protein; VP5 | 33904–38049 | − | 95.9 | 82.8 |

| UL20 | Envelope protein | 38218–38880 | − | 92.7 | 62.6 |

| UL21 | Tegument protein | 39328–40893 | + | 91.2 | 59.9 |

| UL22 | Envelope glycoprotein H | 40993–43563 | − | 89.9 | 48.8 |

| UL23 | Thymidine kinase | 43733–44722 | − | 84.2 | 41.9 |

| UL24 | Nuclear protein | 44802–45593 | + | 83.7 | 58.8 |

| UL25 | DNA packaging tegument protein | 45792–47540 | + | 95.0 | 76.3 |

| UL26 | Capsid maturation protease | 47619–49502 | + | 84.7 | 55.5 |

| UL27 | Envelope glycoprotein B | 49833–52052 | − | 94.7 | 59.0 |

| UL28 | DNA packaging terminase subunit 2 | 52477–54837 | − | 91.3 | 71.4 |

| UL29 | Single-stranded DNA-binding protein; ICP8 | 54976–58566 | − | 95.9 | 81.1 |

| UL30 | DNA polymerase catalytic subunit | 59282–62989 | + | 92.2 | 73.5 |

| UL31 | Nuclear egress lamina protein | 62916–63848 | − | 95.8 | 74.0 |

| UL32 | DNA packaging protein | 63841–65592 | − | 92.1 | 70.2 |

| UL33 | DNA packaging protein | 65591–65980 | + | 94.6 | 65.6 |

| UL34 | Nuclear egress membrane protein | 66042–66872 | + | 87.7 | 57.6 |

| UL35 | Small capsid protein | 66957–67286 | + | 92.7 | 56.6 |

| UL36 | Large tegument protein | 67381–75249 | − | 76.1 | 46.9 |

| UL37 | Tegument protein | 76461–79718 | − | 93.5 | 62.0 |

| UL38 | Capsid triplex subunit 1 | 80085–81473 | + | 83.3 | 59.6 |

| UL39 | Ribonucleotide reductase subunit 1 | 81831–85625 | + | 82.5 | 52.9 |

| UL40 | Ribonucleotide reductase subunit 2 | 85661–86668 | + | 94.9 | 73.8 |

| UL41 | Tegument host shutoff protein | 86793–88286 | − | 94.6 | 64.5 |

| UL42 | DNA polymerase processivity subunit | 88701–90164 | + | 74.7 | 46.1 |

| UL43 | Envelope protein | 90326–91510 | + | 78.9 | 36.3 |

| UL44 | Envelope glycoprotein C | 91687–93075 | + | 81.4 | 44.0 |

| UL45 | Membrane protein | 93186–93698 | + | 86.5 | 44.8 |

| UL46 | Tegument protein VP11/12 | 93778–96186 | − | 86.9 | 49.9 |

| UL47 | Tegument protein VP13/14 | 96249–98378 | − | 87.7 | 55.8 |

| UL48 | Transactivating tegument protein VP16 | 98738–100186 | − | 91.9 | 65.5 |

| UL49 | Tegument protein VP22 | 100578–101447 | − | 77.2 | 39.4 |

| UL49A | Envelope glycoprotein N | 101767–102012 | − | 81.5 | 30.8 |

| UL50 | Deoxyuridine triphosphatase | 102025–103089 | + | 89.8 | 41.3 |

| UL51 | Tegument protein | 103210–103899 | − | 90.4 | 59.6 |

| UL52 | Helicase-primase primase subunit | 103975–107115 | + | 87.0 | 63.1 |

| UL53 | Envelope glycoprotein K | 107085–108092 | + | 93.7 | 64.8 |

| UL54 | Multifunctional expression regulator; ICP27 | 108732–110366 | + | 77.7 | 54.1 |

| UL55 | Nuclear protein | 110705–111256 | + | 97.3 | 61.8 |

| UL56 | Membrane protein | 111957–112835 | − | 67.5 | 26.8 |

| RL2 | Ubiquitin E3 ligase; ICP0 | − | Not calculated | 17.6 | |

| Exon 1 | 116672–117061 | Not calculated | Not calculated | ||

| Exon 2 | 114829–115422 | Not calculated | Not calculated | ||

| RL1 | ICP34.5 | 118066–118953 | − | 80.4 | 34.6 |

| RS1 | ICP4 | 121128–124547 | − | 85.4 | 56.4 |

| US1 | Regulatory protein ICP22 | 126048–127286 | + | 68.3 | 37.0 |

| US2 | Virion protein | 127413–128315 | − | 89.3 | 59.2 |

| US3 | Serine/threonine protein kinase | 128549–129946 | + | 90.3 | 58.6 |

| US4 | Envelope glycoprotein G | 130039–132231 | + | 54.2 | 11.1 |

| US5 | Envelope glycoprotein J | 132460–133098 | + | Not calculated | 14.7 |

| US6 | Envelope glycoprotein D | 133385–134557 | + | 88.0 | 57.6 |

| US7 | Envelope glycoprotein I | 134720–136102 | + | 60.8 | 35.6 |

| US8 | Envelope glycoprotein E | 136322–137989 | + | 71.7 | 39.9 |

| US8A | PtAHV1 US8A-like protein | 137931–138221 | + | 55.6 | 22.8 |

| RS1 | ICP4 | 139854–143273 | + | 85.4 | 56.4 |

+ and −, forward and reverse directions, respectively.

Whole-genome sequence of PLAHV.

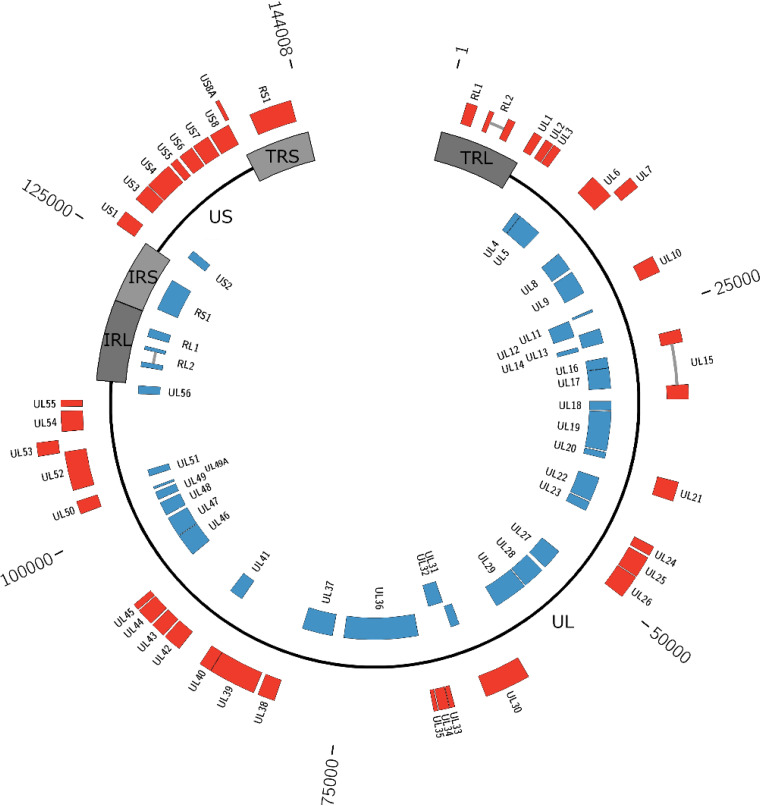

The plaque-purified virus, PLAHV, was subjected to whole-genome sequencing, in which 130,302 reads with an average of 164 bases in length were generated with Ion PGM and were assembled and connected with the nucleotide sequences determined with the Sanger sequencing to generate 2 contig sequences (nucleotides 1007 to 22354 and 22871 to 143355 of the whole genome). Because the gap of 516 bp between the 2 contig sequences could not be determined, another high-throughput sequencer, MinION, was used. MinION generated 3,353 reads with an average of 6,852 bases in length, making it possible to fill the gap region. The complete genome sequence of PLAHV was thus determined to be 144,008 bp in length. The GC content was 62.087%. Compared with the genome structure of PtAHV1, the PLAHV genome had 2 unique nucleotide sequence regions (UL and US), both of which were flanked by 2 inverted repeat sequence regions (TRL and IRL and IRS and TRS, respectively) (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

Schematic diagram of the genome structure of PLAHV. The whole-genome sequence of PLAHV of 144,008 bp in length was determined, and 72 genes were predicted. The genomic sequence is depicted as black lines and dark and light gray boxes, which indicate unique regions (UL and US), repeat regions flanking UL (TRL and IRL), and those flanking US (IRS and TRS), respectively. The linear genome is depicted in a circular manner. Genes predicted are shown in red (forward direction) and in blue (reverse direction) boxes labeled with each name. The nucleotide position is shown outside the diagram.

The PLAHV genome was predicted to carry 72 genes, including duplication of RL1, RL2, and RS1 in the repeat regions (Fig. 2 and Table 2). The mRNA sequences of the RL2 and US15 genes, which each have an intron within their open reading frames (ORFs), were sequenced and their splicing sites were determined. The expression of US5 gene was further confirmed, because PtAHV1 has no such gene, by sequencing their mRNAs using 5′-GGCCACGCGTCGACTAGTACTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT-3′ as the primer for reverse transcription. The cDNA was synthesized by PCR using primers flanking the poly(A) sequence and sequenced. US9, which was carried in the PtAHV1 genome (NC_024306.1), could not be annotated, but US5, which was not carried in the PtAHV1 genome, was shown in the PLAHV genome.

The amino acid sequence identity of each PLAHV gene with the corresponding gene of PtAHV1 and HSV-1 strain 17 (NC_001806.2) was calculated and ranged from 54.2 to 97.3% and 11.1 to 82.8%, respectively. Thirty of 69 proteins were highly similar (>90% identity) to the corresponding PtAHV1 proteins, whereas 5 proteins had a similarity of <70% (Table 2).

The UL23, UL30, and US4 genes of isolates from the other 2 urine samples were determined by Sanger sequencing and were confirmed to be identical to these genes in the complete genome sequence (data not shown).

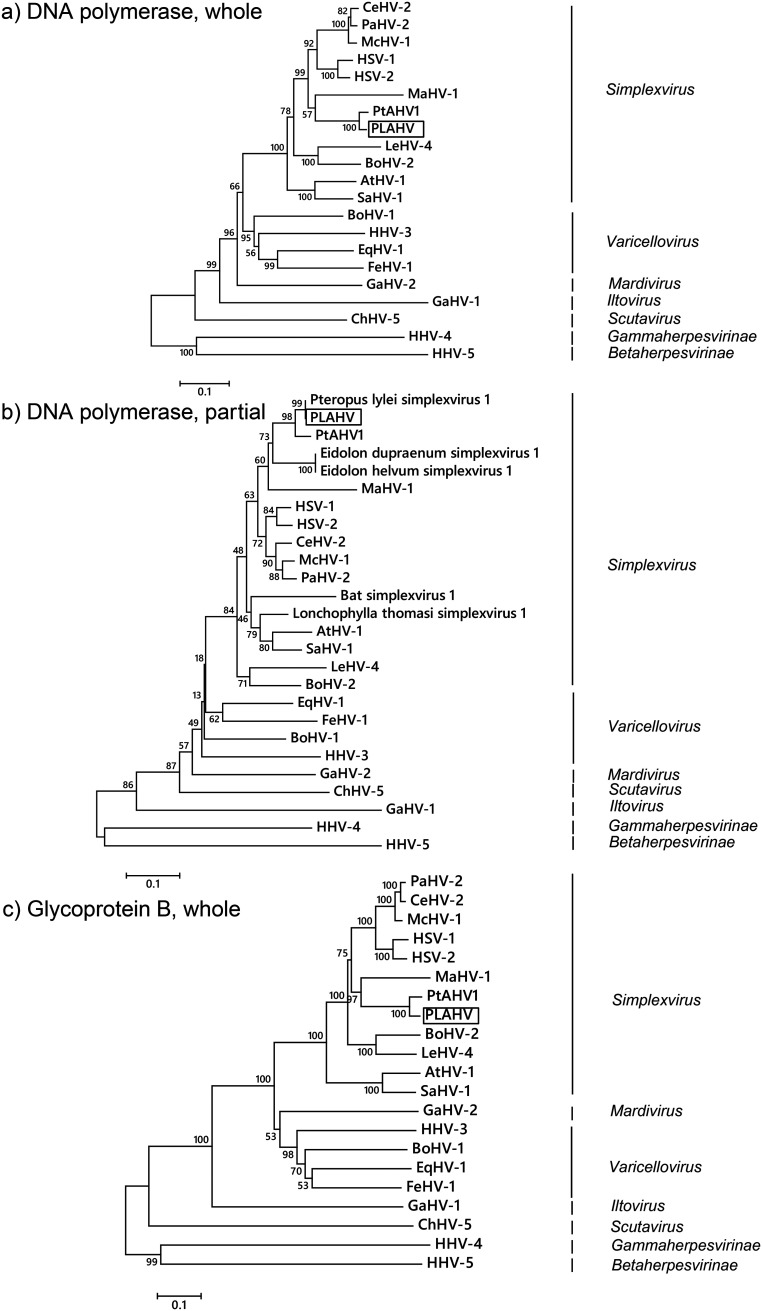

Phylogenetic analyses.

Phylogenetic trees were constructed based on the amino acid sequences corresponding to the UL27 and UL30 genes, which encoded glycoprotein B and the DNA polymerase catalytic subunit, respectively (Fig. 3 and Table 2). PLAHV was assigned to genus Simplexvirus within subfamily Alphaherpesvirinae in all of the trees constructed (Fig. 3). PLAHV was clustered with other simplexviruses isolated from pteropodid bats, which branched from the common ancestor of the present human and Old World primate simplexviruses (Fig. 3b and Table 1). The clade for pteropodid simplexviruses was subdivided into two branches, one of which was for the isolates from bats in Southeast Asia and the other of which was for those in Africa (Fig. 3b and Table 1). The amino acid sequence corresponding to the UL30 gene of PLAHV was identical to that of an isolate from P. lylei in Cambodia (GenBank accession number FJ040877.1) (Fig. 3b and Table 1) (7).

FIG 3.

Phylogenetic trees of herpesviruses. The phylogenetic trees were constructed based on the amino acid sequences of whole viral DNA polymerase (encoded in UL30) (a), partial viral DNA polymerase (b), and whole glycoprotein B (encoded in UL27) (c) using the neighbor-joining method. Scale bars indicate the branch length representing the number of amino acid substitutions per site. The bootstrap percentage of 1,000 replicate calculations is shown next to each branch. Viruses used to construct the trees are listed in Table 3.

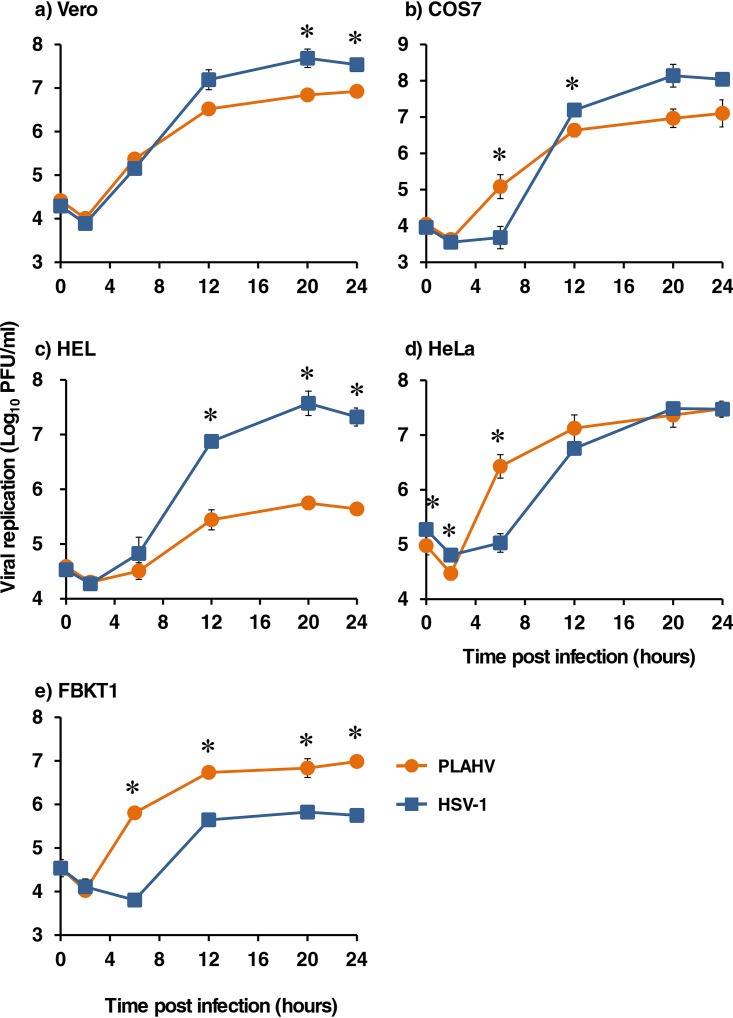

In vitro replication of PLAHV in mammalian cells.

The replication capacities of PLAHV in several mammalian cells were compared to those of HSV-1. PLAHV replicated in all of the cells tested, although the replication capacities were different depending on the cell types (Fig. 4). PLAHV replicated less efficiently than HSV-1 F in Vero cells (Fig. 4a). PLAHV replicated as well in COS7 and HeLa cells as HSV-1 F did, although PLAHV generated more progeny at early time points (Fig. 4b and d). PLAHV replicated more efficiently in FBKT1 cells (established from kidney of Pteropus dasymallus yayeyamae [14]) than HSV-1 F but less efficiently in human embryonic lung (HEL) cells (Fig. 4c and e).

FIG 4.

Replication kinetics of PLAHV (orange) and HSV-1 (blue) in Vero (a), COS7 (b), HEL (c), HeLa (d), and FBKT1 (e) cells. These cells were inoculated with PLAHV or HSV-1 F at a multiplicity of infection of 5 and were cultured with maintenance medium. The cells with culture medium were harvested at 0, 2, 6, 12, 20, and 24 h postinfection, and the infectious dose of each sample was measured with the standard plaque assay. Means and SDs from 3 independent experiments are shown. *, statistical significance with a P value of <0.05 as calculated by Student’s t test.

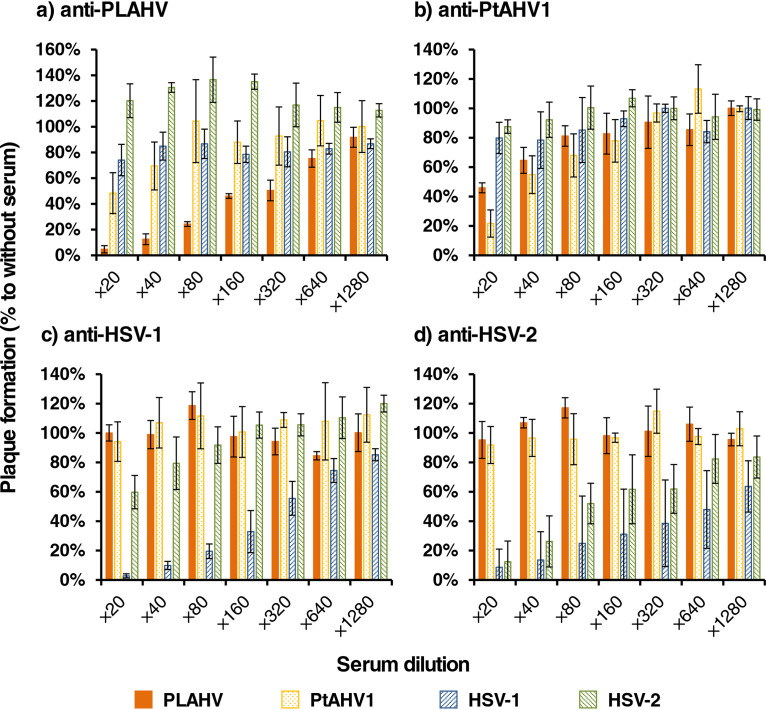

Serological relationship between bat and human simplexviruses.

Anti-PLAHV sera inhibited the plaque formation of both PLAHV and PtAHV1, but the inhibitory efficacy against PLAHV was stronger than that against PtAHV1 (Fig. 5a). Anti-PLAHV sera did not inhibit plaque formation by HSV-1 F or HSV-2 186. Similar phenomena were seen in the neutralization activities of anti-PtAHV1 sera (Fig. 5b). In contrast, sera raised against each of HSV-1 F and HSV-2 186 did not inhibit the plaque formation of either PLAHV or PtAHV1, whereas they did inhibit the plaque formation of both HSV-1 F and HSV-2 186 (Fig. 5c and d).

FIG 5.

Serological analyses between bat and human alphaherpesviruses. The target virus was mixed with DMEM (control) or each serum sample serially diluted with DMEM and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The mixtures were then inoculated in triplicate to Vero cells, and the inoculated cells were incubated for 2 days to form plaques. The neutralization activities of mouse sera raised against PLAHV (a), PtAHV1 (b), HSV-1 (c), and HSV-2 (d) to each virus are shown as the percentage of the plaque numbers to the control. Percentages are shown as means ± SDs calculated from 3 independent experiments.

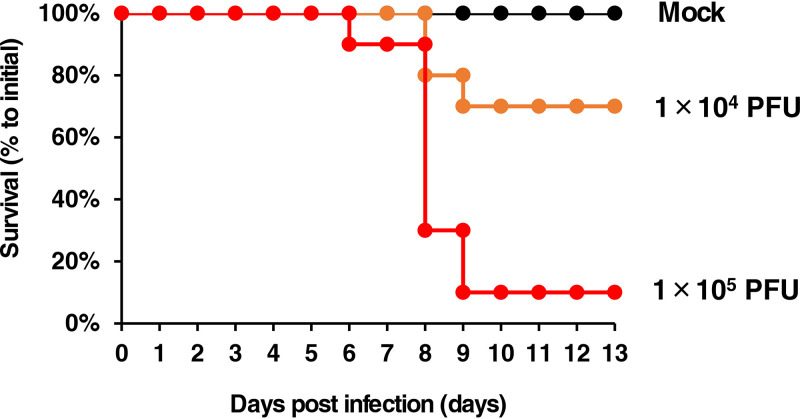

Pathogenicity of PLAHV to mice.

The body weight of BALB/c mice decreased when the mice were intranasally inoculated with PLAHV in an infectious dose-dependent manner. Some mice showed ulcerative skin lesions around their eyes from 5 days postinfection. The 50% lethal dose (LD50) values of PLAHV for mice were calculated to be 2.0 × 104 PFU/mouse at 13 days postinfection (Fig. 6).

FIG 6.

Experimental infection of mice with PLAHV. Five and 4 mice were inoculated through the nasal cavity with virus solution containing 1 × 104 or 1 × 105 PFU of PLAHV, respectively, and the medium without virus as the control group (mock). Survival percentages of each group on each day are shown. The experiments were conducted twice independently.

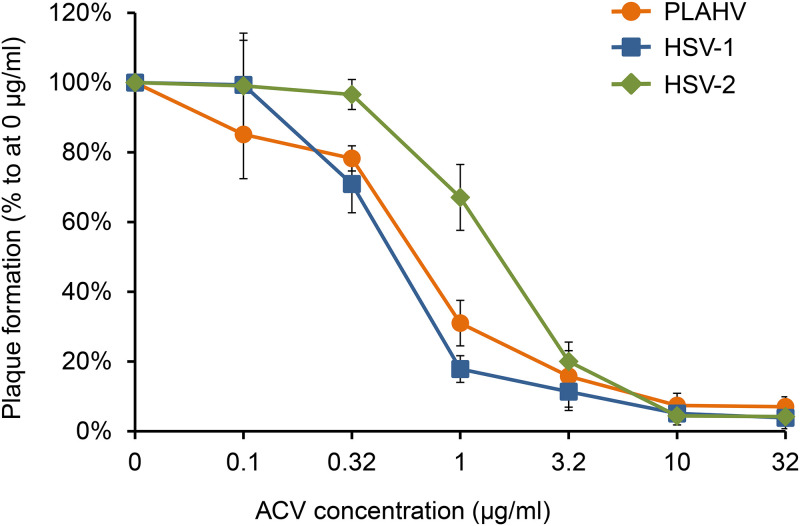

Sensitivity of PLAHV to acyclovir.

Acyclovir (ACV) inhibited the replication of PLAHV in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 7). The inhibitory effect of ACV on PLAHV was parallel to that on HSV-1 F. The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of ACV for PLAHV, HSV-1 F, and HSV-2 186 were 0.64 μg/ml, 0.50 μg/ml, and 1.5 μg/ml, respectively. There was no significant difference in IC50 values between PLAHV and HSV-1 F (P = 0.20, Student’s t test).

FIG 7.

Sensitivities of PLAHV, HSV-1, and HSV-2 to acyclovir (ACV) as determined with plaque reduction assay in Vero cells. Vero cells cultured in 24-well culture plates were inoculated with PLAHV, HSV-1, or HSV-2 in triplicate and were cultured for 2 days in DMEM-1FBS containing 1% (wt/vol) methylcellulose and the designated concentration of ACV. Data are shown as the means and SDs from 3 independent reactions.

DISCUSSION

PCR and high-throughput sequencing have made it possible to elucidate the genetic diversity of herpesviruses in bats in detail (15–25). In addition, infectious viruses were isolated from specimens of bats, and their characteristics, such as the genome sequence (7–13), replication capacity in several human and other mammalian cell lines (8, 10–12), and virulence in mice (8), were studied. Five bat alphaherpesviruses have been isolated (7, 8). However, their virologic properties have not been analyzed in detail except for PtAHV1 (8).

The complete genome sequence of PLAHV was determined, and 72 genes were predicted (Fig. 2 and Table 2). PLAHV included the US5 gene, whose respective gene was absent in PtAHV1, whereas PtAHV1 included the US9 gene, whose respective gene was absent in PLAHV. Furthermore, the identities in some viral proteins were relatively small (e.g., US4), suggesting that PLAHV and PtAHV1 can be considered independent species from each other. The partial genomic sequence (465 bp encoding 155 amino acid residues of the UL30 gene) of the isolate from P. lylei in Cambodia (GenBank accession number FJ040877.1) was reported previously (7). The corresponding gene sequence of PLAHV (nucleotides 61463 to 61927) was almost identical to that of the Cambodian isolate. The GC content in the PLAHV genome was 62.087%, while those in PtAHV1 (GenBank accession number NC_024306.1), macropodid herpesviruses 1 (MaHV-1; NC_029132.1), HSV-1 (NC_001806.2), HSV-2 (NC_001348.1), and varicella zoster virus were 60.856%, 52.920%, 68.301%, 70.379%, and 46.020%, respectively. MaHV-1 is an alphaherpesvirus of marsupial population origin. It was confirmed that PLAHV has a similar characteristic in terms of the GC content to that of bat-originated PtAHV1.

Several types of human cells were well competent for infection by a bat alphaherpesvirus (8). The present study showed, however, that the replication of PLAHV in HEL cells was severely impaired compared to that of HSV-1 (Fig. 4c). In contrast, PLAHV replicated more efficiently in bat kidney-derived FBKT1 cells than did HSV-1 (Fig. 4e). It is noteworthy that PtAHV1 efficiently replicated in CHO-K1 cells (8), in which HSV-1 cannot replicate because the cells lack HSV-1 entry receptors (26, 27). Future comparative studies are expected to reveal the replication mechanism of bat alphaherpesviruses and those of HSV-1.

Pteropodid bats are associated with the human community, in which they are recognized as a source of meat and medicines, and have been killed as agricultural pests and for sport hunting (28, 29). Thus, it is possible that humans are being exposed to bat alphaherpesviruses, including PLAHV. Herpesviruses rarely infect unnatural hosts, but some herpesviruses, such as Macacine alphaherpesvirus 1 (herpes B virus) and Suid alphaherpesvirus 1 (pseudorabies virus), cause severe disease when they do infect them (30, 31). Therefore, further studies about infection of humans by bat herpesvirus are needed. The neutralizing test using infectious PLAHV, HSV-1, and HSV-2 in parallel may differentiate PLAHV infections from infections caused by HSV-1 or HSV-2 (Fig. 5). PLAHV was sensitive to ACV (Fig. 7), suggesting that ACV might be a drug of choice if humans are infected with PLAHV.

The complete genome of PLAHV was determined. The genome-wide differences in sequences from another bat alphaherpesvirus, PtAHV1, the serological relationship between bat and human alphaherpesviruses, and the sensitivity of PLAHV to ACV were revealed for the first time. The virulence of PLAHV in BALB/c mice was elucidated. PLAHV lethally infected the mice as PtAHV1 did (8). There might be numbers of other alphaherpesviruses in geographically dispersed and diverse species of bats other than the 6 isolates documented in this and other studies (7, 8). The accumulation of knowledge on the genome and characteristics of bat alphaherpesviruses might unveil the evolutional history of simplexviruses in bats and other mammals and lead to a comprehensive understanding of herpesvirology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Samples (urine and feces) collected from fruit bats in Vietnam.

Urine and feces samples of fruit bats were collected at Ma Toc or Mahutup pagoda, in which the Mahutup pagoda temple known as Doi (Bat) pagoda is located, in Soc Trang province, Mekong Delta, Vietnam, between February 2012 and March 2013. Thousands of flying foxes (P. lylei) inhabit the forest in the precincts of the Mahutup pagoda temple. The bat species was identified through morphological observation and determination of the cytochrome b gene sequence in specimens from bats (data not shown). Clean plastic sheets were used for collection of samples as reported previously (32). Fresh samples were collected using cotton swabs. The swab samples were mixed with viral transport medium (KCl 5.37 mM, 0.44 mM KH2PO4, 4.17 mM NaHCO3, 136.89 mM NaCl, 0.33 mM Na2HPO4, 5.55 mM dextrose, 0.05 mM phenol red, 10 g/liter of bovine albumin, 20,000 U/liter of penicillin G, and 10 mg/liter of streptomycin [pH 7.4]) and kept at –80°C until use.

Cells.

Vero and human rhabdomyosarcoma (RD) cells were used for virus isolation from urine samples. Vero, HeLa, COS7, and FBKT1 cells and human embryonic lung (HEL) fibroblasts were used for the characterization of PLAHV. Vero, RD, and HeLa cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s minimal essential medium (DMEM; Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd., Osaka, Japan) supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Biological Industries, Beit Haemek, Israel), 100 U/ml of penicillin, and 100 μg/ml of streptomycin (both antibiotics from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). FBKT1 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Wako) with 10% FBS and the antibiotics. COS7 and HEL cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS and the antibiotics.

Virus isolation from samples of fruit bats and identification.

The urine samples were subjected to virus isolation. The samples soaked in the transport medium were centrifuged at 3,500 rpm for 10 min, and the supernatants were filtered through a 0.22-μm membrane. Vero and RD cells were inoculated with the supernatant fraction of each sample and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 1% FBS and the antibiotics (DMEM-1FBS) for 7 days. A blind passage procedure was introduced twice.

When CPE appeared in Vero cells and/or RD cells, the cells with CPE were analyzed for virion structure with transmission electron microscopy (JEM1010; JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The culture fluid was also subjected to both next-generation sequencing analysis and a proteomics-based virus detection system using liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-ESI/MS/MS) (33) to detect nucleotide or peptide traces of viruses, respectively.

Transmission electron microscopy.

Twenty-four and 48 h after infection, the cells were detached from the culture flask with a cell scraper, and the cell suspension was centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 5 min. The cell pellet was resuspended and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) and kept overnight at 4°C. The sample was then rinsed carefully in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) several times. The final pellet was fixed with 1% OsO4 in the same buffer for 60 min, then rinsed carefully in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) several times, subsequently dehydrated in graded ethanol (50 to 100%), washed in propylene oxide, and infiltrated for 6 h in a 1:1 mixture of propylene oxide and epoxydic resin. The cells were then embedded in the resin. Thin sections were obtained with an ultramicrotome (Ultracut UC6; Leica Microsystems GmbH, Germany) and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate. The ultrathin section was then observed through a transmission electron microscope operating at 80 kV.

Viruses.

PLAHV used in this study was a novel alphaherpesvirus isolated from P. lylei as described in Results. PtAHV1, another bat-originated alphaherpesvirus, was also used (8), as were HSV-1 strain F and HSV-2 strain 186. All viruses were propagated and titrated in Vero cells cultured in DMEM-1FBS and stored at –80°C until use.

Whole-genome sequencing of PLAHV.

The viral DNA was obtained by lysing Vero cells infected with PLAHV using a QIAmp DNA minikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and sequenced with Ion PGM (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturers’ instructions. The read was de novo assembled using SPAdes assembler to make the contig sequences (34). The gap sequences were amplified by PCR and sequenced with the designated primer sets using an ABI PRISM 3130 genetic analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The nucleotide sequence, which could not be determined with high-throughput next-generation sequencing and the Sanger sequencing method, was determined with another high-throughput sequencer, the MinION (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford Science Park, UK), which generated long read sequences. The culture supernatant of Vero cells infected with PLAHV was centrifuged at 20,000 rpm for 2 h at 4°C. The viral pellet obtained was gently suspended in phosphate-buffered saline solution and lysed with a mixture of phenol, chloroform, and isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1). The viral DNA was subjected to sequencing with MinION following the manufacturer’s instructions. The sequence data were de novo assembled with Canu software (35) and used for filling in the missing gaps. The reads from the PLAHV genome obtained with both sequencing methods were mapped onto the draft genome using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner software (36) and merged by extracting the consensus nucleotide sequence automatically using the Unipro Ugene platform (37). The consensus nucleotide sequence was validated with Sanger sequencing if needed to complete the genome sequence of PLAHV. Due to the structure of PLAHV genome (Fig. 2), nucleotide sequences from genome termini were obtained, but the terminal nucleotides were not determined. The genome termini were determined as follows. The genome termini of PLAHV were blunt ended with T4 DNA polymerase and ligated with a DNA fragment whose nucleotide sequence was known using T4 DNA ligase. The genome termini were amplified by PCR and sequenced with primers flanking the genome termini.

Genome analyses.

The PLAHV genome sequence was annotated referring to the PtAHV1 genome sequence (GenBank accession number NC_024306.1) using GATU software (38). Homologs of the RL2, US5, US10, US11, and US12 genes of HSV-1 strain 17 (NC_001806.2) were searched in the open reading frames of the PLAHV genome sequence detected by GATU software with the BLASTP program using those genes as query sequences. The UL15, RL2, and US5 genes of PLAHV that were predicted were further confirmed by Sanger sequencing of their mRNAs. Briefly, Vero cells were inoculated with PLAHV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5 per cell and harvested at 12 h after infection. The RNA in the infected cells was extracted using an RNeasy Plus minikit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and single-stranded cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript IV reverse transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with the primers 5′-TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT-3′ and 5′-GGCCACGCGTCGACTAGTACTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT-3′. The cDNAs of the UL15, RL2, and US5 genes were amplified with PCR and sequenced with the appropriate designed primers.

The amino acid sequence identities corresponding to each gene predicted in PLAHV to its homolog in PtAHV1 and HSV-1 strain 17 were calculated using the Needle program with default parameters (http://www.bioinformatics.nl/cgi-bin/emboss/needleall).

Phylogenetic analyses.

The phylogenetic trees were constructed using amino acid sequences of herpesviral proteins, including those of PLAHV predicted with the neighbor-joining method using the MEGA 7 program (39). The Poisson model was used as the amino acid substitution model and the alignment gaps were completely removed. The viral species and their GenBank accession numbers included in the analyses are listed in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Viruses and their accession numbers included in the phylogenetic analysis

| Virus | Abbreviation | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|

| Ateline alphaherpesvirus 1 | AtHV-1 | NC_034446.1 |

| Bovine alphaherpesvirus 1 | BoHV-1 | NC_001847.1 |

| Bovine alphaherpesvirus 2 | BoHV-2 | |

| DNA polymerase | AF181249.1 | |

| Glycoprotein B | M21628.1 | |

| Cercopithecine alphaherpesvirus 2 | CeHV-2 | NC_006560.1 |

| Chelonid alphaherpesvirus 5 | ChHV-5 | HQ878327.2 |

| Equid alphaherpesvirus 1 | EqHV-1 | NC_001491.2 |

| Felid alphaherpesvirus 1 | FeHV-1 | NC_013590.2 |

| Pteropodid alphaherpesvirus 1 | PtAHV1 | NC_024306.1 |

| Gallid alphaherpesvirus 1 | GaHV-1 | NC_006623.1 |

| Gallid alphaherpesvirus 2 | GaHV-2 | NC_002229.3 |

| Human alphaherpesvirus 1 | HSV-1 | NC_001806.2 |

| Human alphaherpesvirus 2 | HSV-2 | NC_001798.2 |

| Human alphaherpesvirus 3 | HHV-3 | NC_001348.1 |

| Human betaherpesvirus 5 | HHV-5 | NC_006273.2 |

| Human gammaherpesvirus 4 | HHV-4 | NC_007605.1 |

| Leporid alphaherpesvirus 4 | LeHV-4 | NC_029311.1 |

| Macacine alphaherpesvirus 1 | McHV-1 | NC_004812.1 |

| Macropodid alphaherpesvirus 1 | MaHV-1 | NC_029132.1 |

| Papiine alphaherpesvirus 2 | PaHV-2 | NC_007653.1 |

| Saimiriine alphaherpesvirus 1 | SaHV-1 | NC_014567.1 |

| Eidolon dupraenum simplexvirus 1 | FJ040879.1 | |

| Eidolon helvum simplexvirus 1 | FJ040890.1 | |

| Bat simplexvirus 1 | FJ040888.1 | |

| Pteropus lylei simplexvirus 1 | FJ040877.1 | |

| Lonchophylla thomasi simplexvirus 1 | FJ040887.1 |

In vitro replication assay (one-step growth).

Vero, COS7, HEL, HeLa, and FBKT1 cells were inoculated with PLAHV or HSV-1 F at an MOI of 5 and incubated for 1 h at 37°C and 5% CO2 for adsorption. The cells were then washed 3 times with phosphate-buffered saline solution and cultured for the desired times. Vero, COS7, HeLa, and HEL cells were cultured with DMEM-1FBS, whereas the FBKT1 cells were cultured with RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 1% FBS. The cells with culture medium were harvested at the desired time points, and the infectious dose of each sample was measured as described previously (40), with some modifications.

Virulence of PLAHV in mice.

Four-week-old female BALB/c mice (Japan SLC, Inc., Shizuoka, Japan) were intranasally inoculated with 5 μl of DMEM containing the desired dose of PLAHV under anesthesia using isoflurane and monitored daily for their survival and body weight for 13 days. Mice were euthanized under excess CO2 gas when they lost more than 20% of their initial body weight. Five mice were used for each infectious dose group, and the LD50 was calculated by the Reed and Muench method (41).

Production of mouse anti-PLAHV, PtAHV1, HSV-1 F, or HSV-2 serum.

Four-week-old female BALB/c mice (Japan SLC, Inc.) were inoculated with either PLAHV, PtAHV1, HSV-1 F, or HSV-2 186 as described above at the respective dose of 1.0 × 104, 1.0 × 102, 1.0 × 102, or 1.0 × 102 PFU/mouse. Two weeks later, mice of each group were again intraperitoneally inoculated with 200 μl of DMEM containing the respective virus at the respective dose of 1.0 × 105, 1 × 105, 1 × 103, or 1 × 103 PFU. The mice of the PtAHV1-inoculated group were euthanized under excess CO2 gas, and their blood was collected and pooled 1 month after the second infection, whereas the mice in the other groups were intraperitoneally inoculated with the respective virus at the dose of 1 × 105 PFU/mouse, and their blood was collected 2 weeks after the third inoculation. The condition of these mice was monitored until the day of blood collection. Each blood pool was stored at 4°C overnight and centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The serum fractions were stored at –25°C until use.

Neutralization antibody assay.

Each serum sample obtained was incubated at 56°C for 30 min for heat inactivation and stored at –25°C until use. The serum samples were 2-fold serially diluted with DMEM. Then, 35 μl of each serum sample was mixed with 315 μl of virus solution containing 50 PFU of each virus/90 μl and incubated for 1 h at 37°C under a 5% CO2 humidified condition. Vero cells in 24-well culture plates were then inoculated with 100 μl of each mixture in triplicate, and the number of plaques was counted as described above 2 days after inoculation.

Determination of PLAHV sensitivity to acyclovir.

Sensitivities of PLAHV, HSV-1 F, and HSV-2 186 to acyclovir (Tokyo Chemical Industry, Tokyo, Japan) in Vero cells were evaluated with the standard plaque reduction assay as described previously (40, 42).

Statistical analyses.

The differences in replication kinetics and antiviral sensitivity of PLAHV to those of HSV-1 were assessed using Student’s t test. All statistical calculations and data visualizations were performed with Microsoft Excel software.

Ethics statement.

All of the animal experiments in this study were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Institute of Infectious Diseases (no. 116112) and conducted in compliance with animal husbandry and welfare regulations of Japan.

Data availability.

The genome sequence information for PLAHV was deposited in GenBank with accession number LC492974. All the materials and data on this study will be distributed if requested.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Hirofumi Sawa (Hokkaido University), Ken Maeda (Yamaguchi University), and Yasushi Kawaguchi (University of Tokyo) for providing us with PtAHV1, the FBKT1 cell line, and HSV-1 F and HSV-2 186, respectively. We thank Yoshiko Fukui and Mihoko Tsuda for their assistance with this study.

This work was funded by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (grant number 18K07894) and by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development under grant numbers JP19fm0108001 and JP20wm0125006 (Japan Initiative for Global Research Network on Infectious Diseases).

We declare that there are no conflicts of interest with regard to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pellett PE, Roizman B. 2013. Herpesviridae, p 1802–1822. In Knipe DM, Howley PM, Cohen JI, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Racaniello VR, Roizman B (ed), Fields virology, 6th ed, vol 2 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davison AJ. 2010. Herpesvirus systematics. Vet Microbiol 143:52–69. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calisher CH, Childs JE, Field HE, Holmes KV, Schountz T. 2006. Bats: important reservoir hosts of emerging viruses. Clin Microbiol Rev 19:531–545. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00017-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuzmin IV, Bozick B, Guagliardo SA, Kunkel R, Shak JR, Tong S, Rupprecht CE. 2011. Bats, emerging infectious diseases, and the rabies paradigm revisited. Emerg Health Threats J 4:7159. doi: 10.3402/ehtj.v4i0.7159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith I, Wang LF. 2013. Bats and their virome: an important source of emerging viruses capable of infecting humans. Curr Opin Virol 3:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ksiazek TG, Rota PA, Rollin PE. 2011. A review of Nipah and Hendra viruses with an historical aside. Virus Res 162:173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Razafindratsimandresy R, Jeanmaire EM, Counor D, Vasconcelos PF, Sall AA, Reynes JM. 2009. Partial molecular characterization of alphaherpesviruses isolated from tropical bats. J Gen Virol 90:44–47. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.006825-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sasaki M, Setiyono A, Handharyani E, Kobayashi S, Rahmadani I, Taha S, Adiani S, Subangkit M, Nakamura I, Sawa H, Kimura T. 2014. Isolation and characterization of a novel alphaherpesvirus in fruit bats. J Virol 88:9819–9829. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01277-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watanabe S, Maeda K, Suzuki K, Ueda N, Iha K, Taniguchi S, Shimoda H, Kato K, Yoshikawa Y, Morikawa S, Kurane I, Akashi H, Mizutani T. 2010. Novel betaherpesvirus in bats. Emerg Infect Dis 16:986–988. doi: 10.3201/eid1606.091567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang H, Todd S, Tachedjian M, Barr JA, Luo M, Yu M, Marsh GA, Crameri G, Wang LF. 2012. A novel bat herpesvirus encodes homologues of major histocompatibility complex classes I and II, C-type lectin, and a unique family of immune-related genes. J Virol 86:8014–8030. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00723-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shabman RS, Shrivastava S, Tsibane T, Attie O, Jayaprakash A, Mire CE, Dilley KE, Puri V, Stockwell TB, Geisbert TW, Sachidanandam R, Basler CF. 2016. Isolation and characterization of a novel gammaherpesvirus from a microbat cell line. mSphere 1:e00070-15. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00070-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Subudhi S, Rapin N, Dorville N, Hill JE, Town J, Willis CKR, Bollinger TK, Misra V. 2018. Isolation, characterization and prevalence of a novel gammaherpesvirus in Eptesicus fuscus, the North American big brown bat. Virology 516:227–238. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2018.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noguchi K, Kuwata R, Shimoda H, Mizutani T, Hondo E, Maeda K. 2019. The complete genomic sequence of Rhinolophus gammaherpesvirus 1 isolated from a greater horseshoe bat. Arch Virol 164:317–319. doi: 10.1007/s00705-018-4040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maeda K, Hondo E, Terakawa J, Kiso Y, Nakaichi N, Endoh D, Sakai K, Morikawa S, Mizutani T. 2008. Isolation of novel adenovirus from fruit bat (Pteropus dasymallus yayeyamae). Emerg Infect Dis 14:347–349. doi: 10.3201/eid1402.070932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wibbelt G, Kurth A, Yasmum N, Bannert M, Nagel S, Nitsche A, Ehlers B. 2007. Discovery of herpesviruses in bats. J Gen Virol 88:2651–2655. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anthony SJ, Epstein JH, Murray KA, Navarrete-Macias I, Zambrana-Torrelio CM, Solovyov A, Ojeda-Flores R, Arrigo NC, Islam A, Ali Khan S, Hosseini P, Bogich TL, Olival KJ, Sanchez-Leon MD, Karesh WB, Goldstein T, Luby SP, Morse SS, Mazet JAK, Daszak P, Lipkin WI. 2013. A strategy to estimate unknown viral diversity in mammals. mBio 4:e00598-13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00598-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baker KS, Leggett RM, Bexfield NH, Alston M, Daly G, Todd S, Tachedjian M, Holmes CE, Crameri S, Wang LF, Heeney JL, Suu-Ire R, Kellam P, Cunningham AA, Wood JL, Caccamo M, Murcia PR. 2013. Metagenomic study of the viruses of African straw-coloured fruit bats: detection of a chiropteran poxvirus and isolation of a novel adenovirus. Virology 441:95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paige Brock A, Cortés-Hinojosa G, Plummer CE, Conway JA, Roff SR, Childress AL, Wellehan JF Jr. 2013. A novel gammaherpesvirus in a large flying fox (Pteropus vampyrus) with blepharitis. J Vet Diagn Invest 25:433–437. doi: 10.1177/1040638713486645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jánoska M, Vidovszky M, Molnár V, Liptovszky M, Harrach B, Benko M. 2011. Novel adenoviruses and herpesviruses detected in bats. Vet J 189:118–121. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2010.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watanabe S, Ueda N, Iha K, Masangkay JS, Fujii H, Alviola P, Mizutani T, Maeda K, Yamane D, Walid A, Kato K, Kyuwa S, Tohya Y, Yoshikawa Y, Akashi H. 2009. Detection of a new bat gammaherpesvirus in the Philippines. Virus Genes 39:90–93. doi: 10.1007/s11262-009-0368-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Molnár V, Jánoska M, Harrach B, Glávits R, Pálmai N, Rigó D, Sós E, Liptovszky M. 2008. Detection of a novel bat gammaherpesvirus in Hungary. Acta Vet Hung 56:529–538. doi: 10.1556/AVet.56.2008.4.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng X, Qiu M, Chen S, Xiao J, Ma L, Liu S, Zhou J, Zhang Q, Li X, Chen Z, Wu Y, Chen H, Jiang L, Xiong Y, Ma S, Zhong X, Huo S, Ge J, Cen S, Chen Q. 2016. High prevalence and diversity of viruses of the subfamily Gammaherpesvirinae, family Herpesviridae, in fecal specimens from bats of different species in southern China. Arch Virol 161:135–140. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2614-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sano K, Okazaki S, Taniguchi S, Masangkay JS, Puentespina R Jr, Eres E, Cosico E, Quibod N, Kondo T, Shimoda H, Hatta Y, Mitomo S, Oba M, Katayama Y, Sassa Y, Furuya T, Nagai M, Une Y, Maeda K, Kyuwa S, Yoshikawa Y, Akashi H, Omatsu T, Mizutani T. 2015. Detection of a novel herpesvirus from bats in the Philippines. Virus Genes 51:136–139. doi: 10.1007/s11262-015-1197-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wada Y, Sasaki M, Setiyono A, Handharyani E, Rahmadani I, Taha S, Adiani S, Latief M, Kholilullah ZA, Subangkit M, Kobayashi S, Nakamura I, Kimura T, Orba Y, Sawa H. 2018. Detection of novel gammaherpesviruses from fruit bats in Indonesia. J Med Microbiol 67:415–422. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu Z, Yang L, Ren X, He G, Zhang J, Yang J, Qian Z, Dong J, Sun L, Zhu Y, Du J, Yang F, Zhang S, Jin Q. 2016. Deciphering the bat virome catalog to better understand the ecological diversity of bat viruses and the bat origin of emerging infectious diseases. ISME J 10:609–620. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montgomery RI, Warner MS, Lum BJ, Spear PG. 1996. Herpes simplex virus-1 entry into cells mediated by a novel member of the TNF/NGF receptor family. Cell 87:427–436. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81363-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicola AV, McEvoy AM, Straus SE. 2003. Roles for endocytosis and low pH in herpes simplex virus entry into HeLa and Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Virol 77:5324–5332. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.9.5324-5332.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fujita MS, Tuttle MD. 1991. Flying foxes (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae): threatened animals of key ecological and economic importance. Conserv Biol 5:455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.1991.tb00352.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Epstein JH, Olival KJ, Pulliam JRC, Smith C, Westrum J, Hughes T, Dobson AP, Zubaid A, Rahman SA, Basir MM, Field HE, Daszak P. 2009. Pteropus vampyrus, a hunted migratory species with a multinational home-range and a need for regional management. J Appl Ecol 46:991–1002. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2009.01699.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tischer BK, Osterrieder N. 2010. Herpesviruses—a zoonotic threat? Vet Microbiol 140:266–270. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woźniakowski G, Samorek-Salamonowicz E. 2015. Animal herpesviruses and their zoonotic potential for cross-species infection. Ann Agric Environ Med 22:191–194. doi: 10.5604/12321966.1152063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chua KB. 2003. A novel approach for collecting samples from fruit bats for isolation of infectious agents. Microbes Infect 5:487–490. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(03)00067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okamoto K, Endo Y, Inoue S, Nabeshima T, Nga PT, Guillermo PH, Yu F, Loan DP, Trang BM, Natividad FF, Hasebe F, Morita K. 2010. Development of a rapid and comprehensive proteomics-based arboviruses detection system. J Virol Methods 167:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, Lesin VM, Nikolenko SI, Pham S, Prjibelski AD, Pyshkin AV, Sirotkin AV, Vyahhi N, Tesler G, Alekseyev MA, Pevzner PA. 2012. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol 19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koren S, Walenz BP, Berlin K, Miller JR, Bergman NH, Phillippy AM. 2017. Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res 27:722–736. doi: 10.1101/gr.215087.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li H, Durbin R. 2009. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okonechnikov K, Golosova O, Fursov M, UGENE team. 2012. Unipro UGENE: a unified bioinformatics toolkit. Bioinformatics 28:1166–1167. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tcherepanov V, Ehlers A, Upton C. 2006. Genome Annotation Transfer Utility (GATU): rapid annotation of viral genomes using a closely related reference genome. BMC Genomics 7:150. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. 2016. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol 33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saijo M, Suzutani T, Mizuta K, Kurane I, Morikawa S. 2008. Characterization and susceptibility to antiviral agents of herpes simplex virus type 1 containing a unique thymidine kinase gene with an amber codon between the first and the second initiation codons. Arch Virol 153:303–314. doi: 10.1007/s00705-007-1096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reed LJ, Muench H. 1938. A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. Am J Hyg 27:493–497. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a118408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Inagaki T, Satoh M, Fujii H, Yamada S, Shibamura M, Yoshikawa T, Harada S, Takeyama H, Saijo M. 2018. Acyclovir sensitivity and neurovirulence of herpes simplex virus type 1 with amino acid substitutions in the viral thymidine kinase gene, which were detected in the patients with intractable herpes simplex encephalitis previously reported. Jpn J Infect Dis 71:343–349. doi: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2018.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The genome sequence information for PLAHV was deposited in GenBank with accession number LC492974. All the materials and data on this study will be distributed if requested.