Abstract

Pathogen–host cell interactions play an important role in many human infectious and inflammatory diseases. Several pathogens, including Escherichia coli (E. coli), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tb), and even the recent 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV), can cause serious breathing and brain disorders, tissue injury and inflammation, leading to high rates of mortality and resulting in great loss to human physical and mental health as well as the global economy. These infectious diseases exploit the microbial and host factors to induce serious inflammatory and immunological symptoms. Thus the development of anti-inflammatory drugs targeting bacterial/viral infection is an urgent need. In previous studies, YojI-IFNAR2, YojI-IL10RA, YojI-NRP1,YojI-SIGLEC7, and YojI-MC4R membrane–protein interactions were found to mediate E. coli invasion of the blood–brain barrier (BBB), which activated the downstream anti-inflammatory proteins NACHT, LRR and PYD domains-containing protein 2(NLRP2), using a proteomic chip conjugated with cell immunofluorescence labeling. However, the studies of pathogen (bacteria/virus)–host cell interactions mediated by membrane protein interactions did not extend their principles to broad biomedical applications such as 2019-nCoV infectious disease therapy. The first part of this feature article presents in-depth analysis of the cross-talk of cellular anti-inflammatory transduction signaling among interferon membrane protein receptor II (IFNAR2), interleukin-10 receptor subunit alpha (IL-10RA), NLRP2 and [Ca2+]-dependent phospholipase A2 (PLA2G5), based on experimental results and important published studies, which lays a theoretical foundation for the high-throughput construction of the cytokine and virion solution chip. The paper then moves on to the construction of the novel GPCR recombinant herpes virion chip and virion nano-oscillators for profiling membrane protein functions, which drove the idea of constructing the new recombinant virion and cytokine liquid chips for HTS of leading drugs. Due to the different structural properties of GPCR, IFNAR2, ACE2 and Spike of 2019-nCoV, their ligands will either bind the extracellular domain of IFNAR2/ACE2/Spike or the specific loops of the GPCR on the envelope of the recombinant herpes virions to induce dynamic charge distribution changes that lead to the variable electron transition for detection. Taken together, the combined overview of two of the most innovative and exciting developments in the immunoinflammatory field provides new insight into high-throughput construction of ultrasensitive cytokine and virion liquid chips for HTS of anti-inflammatory drugs or clinical diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory diseases including infectious diseases, acute or chronic inflammation (acute gouty arthritis or rheumatoid arthritis), cardiovascular disease, atheromatosis, diabetes, obesity, tissue injury and tumors. It has significant value in the prevention and treatment of these serious and painful diseases.

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Bacterial/viral infection, Signaling cross-talk, Anti-inflammatory, High-throughput construction, Cytokine/virion liquid

Introduction

Infectious diseases such as bacterial meningitis induced by E. coli are accompanied by serious inflammation and are an important cause of mortality and morbidity in neonates and children. In infants, the rate of mortality from these serious diseases is as high as 10–30% [1, 2], and mortality rates are even higher in deadly viral diseases such as that seen with the COVID-19 pandemic.

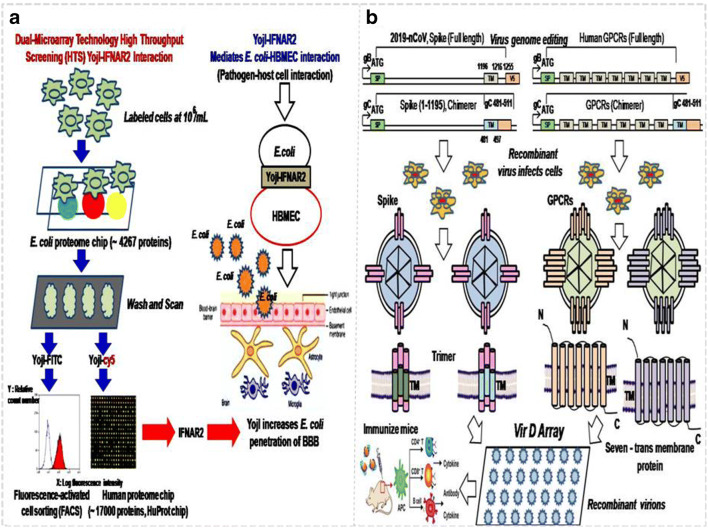

E. coli invasion of the blood–brain barrier, which exploits microbial and host factors, is the essential step for bacterial meningitis to occur. Although such diseases are usually accompanied by a serious inflammatory response, which has received much attention, the detailed molecular mechanism related to the inflammatory and immunological symptoms has not yet been revealed. In a previous study, we found that YojI-IFNAR2, YojI-IL10RA, YojI-NRP1, YojI-SIGLEC7 and YojI-MC4R membrane–protein interactions mediated the E. coli–human brain microvascular endothelial cell (HBMEC) interaction, through the use of human and E. coli proteomic chips [HuProtarray (version II)] conjugated cell labeling, fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) flow cytometry separation technology, and confocal immunofluorescence techniques at Johns Hopkins University medical school (Fig.1, Table 1) [1–5] It was further reported that invasion of HBMEC by E. coli causing meningitis also requires outer-membrane protein A (OmpA), invasion of IbeA, IbeB, IbeC and cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 (CNF1) and rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton. It has also been shown that surface-exposed loops of OmpA contribute to E. coli binding to HBMECs and that OmpA interacts with HBMECs through N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) residues [6]. However, both the IFNAR2 and 1L10RA binding the YojI of E. coli activated the downstream NLRP2 protein (NLR protein family), which induced the anti-inflammatory response of HBMEC. It is speculated that it is involved in the type 2 interferon signaling pathway and suppression of autophagy to inhibit the secretion of IL-1β and IL-18 cytokines [3–5, 7–13]. The newly discovered NLRP2 protein induced by E. coli infection and the NLR protein family are important molecular mechanisms for in vivo inflammation and cytokine secretion [1–7].

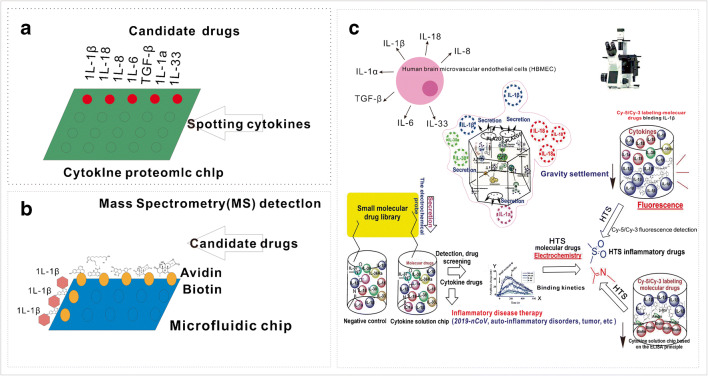

Fig. 1.

The applications of the proteomic chip and virion display array in the pathogen (bacteria/virus)–host cell interaction field: a High-throughput chip assay for investigating E. coli interaction with the blood–brain barrier using microbial and human proteomic microarrays. b Construction of the virion display array for profiling functional membrane proteins and HTS of molecular drugs. The recombinant virions can be immunized mice for further antibody and cytokine production

Table 1.

List of the highlighted hits of human membrane proteins identified by YojI on the HuProt chip (*denotes membrane proteins which bind to both YojI and IbeC)

| Gene symbol | Protein size (a.a.) | Function |

|---|---|---|

| *IFNAR2 | 515 | Interferon alpha/beta receptor 2; associated with IFNAR1 to form the type I interferon receptor. Receptor for interferons alpha and beta. Involved in IFN-mediated association of STAT1, STAT2 and STAT3 activation [1, 2, 5, 6, 14]. |

| *IL10RA | 578 | Cell surface receptor for the cytokine IL10 that participates in IL10-mediated anti-inflammatory functions, limiting excessive tissue disruption caused by inflammation. Upon binding to IL10, induces a conformational change in IL10RB, allowing IL10RB to bind IL10 as well. In turn, the heterotetrameric assembly complex, composed of two subunits of IL10RA and IL10RB, activates the kinases JAK1 and TYK2 that are constitutively associated with IL10RA and IL10RB, respectively. These kinases then phosphorylate specific tyrosine residues in the intracellular domain in IL10RA, leading to the recruitment and subsequent phosphorylation of STAT3. Once phosphorylated, STAT3 homodimerizes, translocates to the nucleus and activates the expression of anti-inflammatory genes. In addition, IL10 RA-mediated activation of STAT3 inhibits starvation-induced autophagy [1, 2]. |

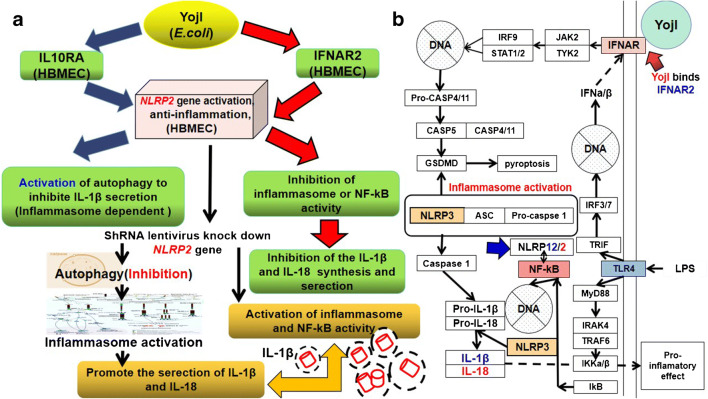

However, the identification of IFNAR2 and IL10RA as a YojI-interacting protein receptor is a very interesting discovery, and the type II interferon signaling pathway (IFN-α/β) which binds IFNAR2 is the most important antiviral cellular defense mechanism (Table 1) [1]. Both IFNAR2 and IL10RA may inhibit autophagy to increase the cytokine secretion of IL-1β and IL-18, because autophagy can target pro-IL-1β for degradation, and inhibition of autophagy prevents degradation of pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18, leaving more cytokines freely available in the cytosol for processing and secretion. In addition, inhibition of autophagy leads to activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and caspase-1-dependent processing of IL-1β and IL-18 cytokines [3–5, 7, 8, 15, 16].

Interleukins (IL) are a group of cytokines secreted by many cell types and can act on a variety of cells by activating and regulating immune cells and mediating the activation, proliferation and differentiation of T and B lymphocytes. They can eliminate infectious pathogens through the induction of secondary mediators and the recruitment of additional immune cells to the site of infection, leading to pyroptosis of the infected cells. Interleukins can also induce the assembly of cytokines, enzymes that regulate local and systemic inflammation responses. IL-1β and IL-18 can induce IFN-γ in T cells and natural killer (NK) cells, and assemble pro-inflammatory cytokines and cell adhesion molecules to amplify the inflammatory response, which is referred to as cytokine storm. It activates the expression of a large number of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) to inhibit viral replication, and performs the tumor-killing function by immune cells and cellular autophagy. It has recently been found that the IL-18 cytokine is a potential immunotherapy target for tumors, which can be directionally engineered by synthetic biology and yeast assembly to become IL-18 mutant (decoy-resistant IL-18, DR-18). It does not bind the natural pseudoreceptor (IL-18BP) that is secreted by many tumor types, which can serve as a tumor marker, but maintains the signaling transduction function to bind the receptor (IL-18Ra/Rβ) to activate NK and CD8 T cells, and replication of immune cells to clear away tumor cells [7, 15]. As such, IL-1β and IL-18 are important proinflammatory cytokines and inflammatory markers, which can be engineered as new targets of immunotherapy for cancer (Fig. 2). Cytokines play a direct role in the rapid activation of the immune system to respond to emergency signals, and were the first immunotherapy drug approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [15].

Fig. 2.

Anti-inflammatory mechanism triggered by YojI-IFNAR2 and YojI-IL10RA membrane protein interactions. a YojI-IFNAR2 and YojI-IL10RA membrane protein interaction induces the anti-inflammatory responses of HBMECs, because the NLRP2 gene inhibits inflammasome-dependent autophagy. NLR oligomerization activates NF-kB activity for the transcription of IL-1β, and mediates caspase-1 cleavage of pro-inflammatory factor IL-1β to the mature IL-1β. b IFN-α/β binding to IFNAR triggers inflammasome activation and inflammatory responses

To date, thirty-eight members are known. IL is the most common and powerful cytokine factor family and includes IL-1β, IL-1a, IL-18, IL-18BP, IL-33, IL-36Ra, IL-36β, IL-36γ, IL-37 and IL-38. IL-1β and IL-18 are the main secreted forms of IL-1 and play an important role in infectious (bacteria/virus), inflammatory and autoimmune diseases (Table 2) [6–8, 14–19]. If these cytokines are subjected to ionized fragments, due to their different mass/charge (m/z) ratios, they will run to form distinct semicircle trajectories in an applied magnetic field, which can be differentiated by high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Protein sequences and functions of the main cytokines IL-1 β, IL-18, IL-6 and IL-8

| Gene name | Protein name | Sequence | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL1β |

Interleukin-1 beta (mature form: 117-269, 153AA) |

APVRSLNCTLRDSQQKSLVMSGPYELKALHLQGQDMEQQVVFSMSFVQGEESNDKIPVALGLKEKNLYLSCVLKDDKPTLQLESVDPKNYPKKKMEKRFVFNKIEINNKLEFESAQFPNWYISTSQAENMPVFLGGTKGGQDIT DFTMQFVSS | Potent proinflammatory cytokine. Initially discovered as a major endogenous pyrogen, induces prostaglandin synthesis, neutrophil influx and activation, T-cell activation and cytokine production, B cell activation and antibody production, and fibroblast proliferation and collagen production. Promotes Th17 differentiation of T cells. Synergizes with IL12/interleukin-12 to induce IFNγ synthesis from T-helper 1 (Th1) cells [3–6]. |

| IL18 | Interleukin-18 (mature form: 37-193aa, 117AA) | YFGK LESKLSVIRNLNDQVLFI DQ GNRPLFEDMT DSDCRDNAPR TIFIISMYKD SQPRGMAVTI SVKCEKISTL SCENKIISFK EMNPPDNIKD TKSDIIFFQR SVPGHDNKMQ FESSSYEGYF LACEKERDLF KLILKKEDEL GDRSIMFTVQNED | A proinflammatory cytokine primarily involved in polarized T-helper 1 (Th1) and natural killer (NK) cell immune responses to perform the tumor-killing effect. Upon binding to IL18R1 and IL18RAP, forms a signaling ternary complex which activates NF-kappa-B, triggering synthesis of inflammatory mediators. It can be applied for immunotherapy for cancer. Synergizes with IL12/interleukin-12 to induce IFNγ synthesis from T-helper 1 (Th1) cells and natural killer (NK) cells [18]. |

| IL6 | Interleukin-6 (mature form: 30-212aa, 183AA) | VPPGEDSKDVA APHRQPLTSS ERIDKQIRYI LDGISALRKE TCNKSNMCES SKEALAENNL NLPKMAEKDG CFQSGFNEET CLVKIITGLL EFEVYLEYLQ NRFESSEEQA RAVQMSTKVL IQFLQKKAKN LDAITTPDPT TNASLLTKLQ AQNQWLQDMT THLILRSFKEFLQSSLRALRQM | Cytokine with a wide variety of biological functions. It is a potent inducer of the acute phase response. Plays an essential role in the final differentiation of B-cells into Ig-secreting cells Involved in lymphocyte and monocyte differentiation. Acts on B and T cells, hepatocytes, hematopoietic progenitor cells and cells of the CNS. Required for the generation of T(H)17 cells. Also acts as a myokine. It is discharged into the bloodstream after muscle contraction and acts to increase the breakdown of fats and to improve insulin resistance. It induces myeloma and plasmacytoma growth and induces nerve cell differentiation [6, 19]. |

| IL8 |

Interleukin-8 (99AA) |

MTSKLAVALL AAFLISAALC EGAVLPRSAK ELRCQCIKTY SKPFHPKFIKELRVIESGPH CANTEIIVKL SDGRELCLDP KENWVQRVVE KFLKRAENS | IL-8 is a chemotactic factor that attracts neutrophils, basophils and T cells, but not monocytes. It is also involved in neutrophil activation. It is released from several cell types in response to an inflammatory stimulus. IL-8(6-77) has a 5–10-fold higher activity on neutrophil activation, IL-8(5-77) has increased activity on neutrophil activation and IL-8(7-77) has a higher affinity to receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 as compared to IL-8(1-77) [6, 19]. |

Table 3.

Comparison of molecular chemical approaches for analyzing secreted cytokines

| Analytical approaches | Working principle | Applied field | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPLC-MS | Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry, which uses liquid chromatography as separation system and mass spectrometry as detection system. After the sample is separated from the mobile phase in the mass spectrum, the ion fragments are separated according to the mass number by the mass analyzer of the mass/charge (m/z) spectrum, which is obtained by the detector. | Drug metabolism, cytokines, antibody, enzyme, polypeptide, polysaccharide, polymer analysis and molecular biology | Can analyze multiple cytokines and drugs at the same time. Analyzes biological macromolecular compounds with very large molecular weight; the determination range of protein analysis molecular weight is more than 105 [1, 2, 20, 21]. | |

| FACS | After being dyed with specific fluorescent dye, the cells to be tested are put into the sample tube and enter the flow chamber filled with sheath fluid under gas pressure. Under the restriction of sheath fluid, cells are arranged in a single row and ejected from the nozzle of the flow chamber to form a cell column. The latter intersects the incident laser beam vertically, and the cells in the liquid column are excited by the laser to produce fluorescence. A series of optical systems (lenses, apertures, filters, detectors, etc.) in the instrument collect signals of fluorescence, light scattering, light absorption or cell electrical impedance. The computer system collects, stores, displays and analyzes various signals, and generates statistical analysis of various indicators. | Cell surface protein analysis, immune cytochemical typing, exogenous and endogenous gene expression, membrane potential and cell permeability | Can analyze multiple components of cytokines and drugs at the same time, with strong fluorescence signal [1, 2, 20]. | |

| ELISA, Char MII | Sandwich principle of molecular hybridization | High-precision detection of single drug, proteins and cytokines [1, 2] | It cannot provide molecular structure, and it is difficult to detect and analyze multiple components of drugs at the same time; cannot effectively exclude a false positive, so it has certain limitations. | |

| 8%–12% SDS-PAGE | Polyacrylamide gel as a support medium for a common electrophoresis technology. It has a molecular sieve effect, which is used to separate cytokines and oligonucleotides. | In this method, the mobility of cytokines is determined mainly by their molecular weight, not by charge and molecular shape [1]. | It cannot determine the specific cytokine. |

In the downstream events, YojI binding of the IL10RA receptor activates NLRP2 gene expression, as identified by the microarray assay. According to the reported literature, the NLRP2 protein belongs to the NOD-like receptor (NLR) signaling family, along with NLRP1, NLRP3 and NLRP7, but its function is speculated to be contrary to NLRP1,3,7 in a few cell types [8, 16]. The NLR proteins, which lead to NF-kB activation of both transcription of IL-1β and cleavage of pro-1β by caspase-1, can be spontaneously oligomerized to form NLR1,3,7-ASC-caspase-1 inflammasomes, which promote the secretion of IL-1β. We have conducted a pre-experiment that has already knocked down the NLRP2 gene in HBMEC to promote a large quantity of IL-1β secretion (data not shown here). Thus, IFNAR2 and IL10RA inhibit autophagy to increase cytokine secretion, possibly through an NLRP2 protein-mediated inflammasome inhibition mechanism (Fig. 2a) [6–8, 14–19].

In our recent experiment, results confirmed that knockdown of the NLRP2 gene by ShRNA lentivirus combined with low-concentration puromycin (8 μg/mL) treatment induced HBMEC secretion of a large quantity of IL-1β. The NLRP2 protein, in contrast to NLRP3, can inhibit the cellular inflammatory response. Therefore, studies on the ligand–membrane protein interactions associated with an intracellular anti-inflammatory mechanism are very meaningful for the development of recombinant virion and cytokine chips for clinical inflammatory disease detection and therapy (Fig. 2b) [20, 22–26].

Membrane protein virion chips and virion nano-oscillators have been constructed for profiling membrane protein functions and HTS of small-molecule drugs

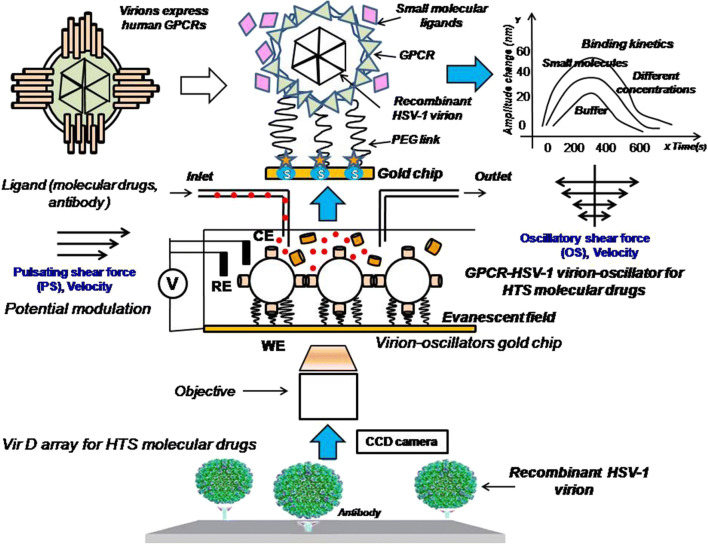

In previous studies, CD4 and G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) virion chips and virion nano-oscillators for profiling membrane protein functions were constructed by the author of the present study and Hu et al. in the USA (Fig. 3) [1, 2]. Both single (i.e., CD4) and multi-pass (i.e., GPCRs) membrane proteins were exquisitely displayed on the envelopes of herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1) with correct orientation and conformation [1, 2, 20]. Single recombinant virion (~185 nm diameter) reacted with polyethylene glycol (PEG) linkers (63 nm in length) to form the virion-PEG complex to be tethered to a gold-coated chip via PEG linkers. With a similar constructive method, a total of 332 (98.5%) GPCR open reading frames (ORFs) of a total of 337 non-odorant GPCRs were sub-cloned into the UL27 locus (gB) of the herpes virus genome and used to fabricate the VirD-GPCR array for high-content study of their pharmacological activity and preferred drug targets (Fig. 3) [2, 21]. Among the 1400 FDA-approved drugs, 475 (34%) drugs targeting 108 non-odorant GPCRs have been identified. Although there are about 70% known to have the ligand, 30% of the GPCRs are still without an identified ligand [20, 21, 26–31]. Thus, the structure of un-characterized GPCRs and the abovementioned membrane proteins including IFNAR2 and IL10RA or Spike/ACE2 of 2019-nCoV can be further incorporated into the herpes virus envelope or highly expressed extracellular transmembrane domain to induce synthetic antibody to block bacterial/viral infection [1, 2, 9, 27, 29–31]. These recombinant virions are versatile players in the biomedical field. Various methods using a combined proteomics and genomics approach are rapidly being developed; however, utilization of the recombinant membrane protein herpes virions for inflammatory disease diagnosis and treatment has not yet been reported. In order to construct a new recombinant virion solution chip to establish a multi-task platform for clinical biomedical applications, we proposed the recombinant virion solution chip integrated with the properties of an electrochemical sensor for use in clinical diagnosis of inflammatory diseases as well as HTS of anti-inflammatory drugs [20, 23–26]. Because the molecular drug-receptor interactions on these recombinant virions will trigger charge distribution and electron transition to produce electrochemical signaling, IFNAR2 and IL10RA membrane proteins can be applied with detection of electrical signals for HTS of anti-inflammatory molecular drugs (Fig. 3) [1, 6, 14, 20, 21]. Different shear forces such as pulsating (PS) and oscillatory shear force (OS) can also be loaded to gain variable binding kinetics to characterize the drug activity (Fig. 3) [6, 20].

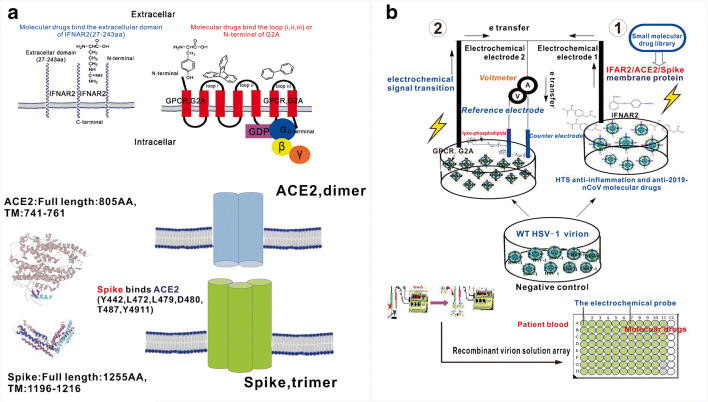

Fig. 3.

Application of the single (IFNAR2) and multi-transmembrane protein (G protein-coupled receptor, GPCR) recombinant herpes virions (IFNAR2-HSV-1 and GPCR-HSV-1) to construct virion nano-oscillators with the perfusion system of a microfluidic device for HTS of molecular drugs. Pulsating shear force (PS) and oscillatory shear force (OS) can be loaded to gain variable binding kinetics to characterize the drug activity

TheNLRP2 gene can be knocked down by ShRNA lentivirus for high-throughput construction of a cytokine solution chip

It is reported that the NLRP2 protein can suppress inflammation [3–5, 16, 32]; thus knockdown of the NLRP2 gene in HBMECs may activate the inflammasome and transcription factor NF-kB and autophagosome to promote the expression and secretion of the IL-1β, IL-18, IL-1α, IL-6, TGFβ, IL-8 and IL-33 cytokines.

There are two steps in IL-1β secretion. First, inflammatory signals, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), stimulate synthesis and promote accumulation of the cytosol of pro-IL-1β. Additional signals, such as ATP, ion, membrane perturbations or reactive oxygen species (ROS), are also required for inflammasome activation and assembly, leading to caspase-1 activation and processing of pro-IL-1β and eventual secretion of the active cytokines.

Findings showed that autophagy has a positive contribution to the biogenesis and secretion of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β via an export pathway that depends on Atg5 and inflammasomes, and at least one of the two mammalian Golgi reassembly stacking protein 55(GRASP55) and Ras-related protein Rab-8a (Rab8a) is required [9–13, 33]. Additionally, PLA2G5 is required for phospholipid hydrolysis and release of IL-1β and IL-18. Knockdown of the NLRP2 gene induces autophagy to promote inflammasome-dependent IL-1β secretion [9–12, 33, 34]. IL-1β lacks any known signal sequence, and the pathways of its secretion in HBMECs are speculated to be mainly through an inflammasome-dependent autophagy mechanism (Table 2, Fig. 2) [9–13, 33, 34].

Based on the results of previous experiments, several unconventional secretion mechanisms are proposed for the secretion of cytokines.

Secretion via secretory lysosome. IL-1β may be incorporated into secretory lysosomes that undergo [Ca2+]-dependent exocytosis with the release of the mature IL-1β with the help of the PLA2G5.

Secretory autophagy: IL-1β-autophagosome may fuse with the plasma membrane to release soluble IL-1β, which is inflammasome-dependent [11–13].

Secretion via exosomes: P2RX7 that is activated by ATP leads to the formation of multivesicular bodies (MVBs) containing exocytosis with IL-1β, caspase-1 and other inflammasome components. These MVBs undergo exocytosis with the release of IL-1β after the lysis of the exosome membrane.

Secretion via microvesicle shedding. P2RX7 induces immediate shedding of membrane-derived microvesicles containing IL-1β and inflammasome components. These cytokines are then released extracellularly after microvesicle lysis.

Release by translocation through permeabilized plasma membrane, which occurs in cells undergoing pyroptosis, due to the sustained activation of the inflammasome.

IL-1β and IL-18 induce the expression of secondary mediators that attract immune cells to the site of the infection. Although IL-1β and IL-18 have a beneficial role in promoting inflammation and eliminating infectious pathogens, mutations that result in constitutive inflammasome activation and the over-production of IL-1β and IL-18 have been linked to auto-inflammatory and autoimmune disorders.

For these reasons, mechanisms that inhibit IL-1β and IL-18 signaling are of great interest to us. Decoy or soluble receptors that sequester IL-1β and IL-1β antagonists and disrupt IL-1 receptor heterodimerization are intrinsic pathways that inhibit IL-1β signaling. Similarly, naturally occurring IL-18 binding protein (IL-18 BP) can prevent IL-18 from binding to its receptor. Based on this bio-analysis of the secretion signaling pathway of IL, three approaches are proposed to increase the extracellular release of cytokines and high-throughput construction of the cytokine solution chip for HTS of molecular drugs.

Knockdown of the NLRP2 gene, along with highly expressed PLA2G5 for hydrolysis of the phospholipid monolayer to promote the local release of IL-1β, IL18, etc., in HBMECs.

Knockdown of the NLRP2 gene and activation of probable G protein-coupled receptor 132 (G2A) gene expression to inhibit cell proliferation and promote inflammation to obtain a high quantity of IL-1β and IL-18.

Knockdown of both the NLRP2 gene and cell adhesion molecule gene (VCAM-1) to promote cell suspension and local inflammation to obtain a high titer of IL-1β, IL-18 and other cytokines in HBMECs.

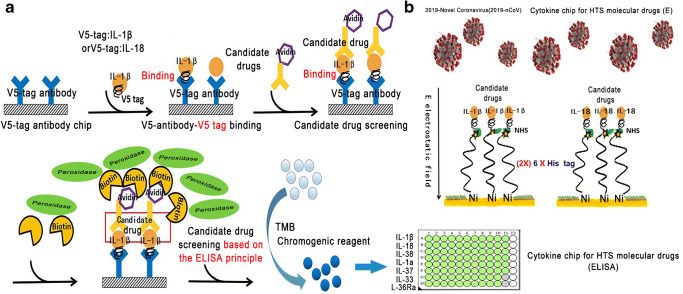

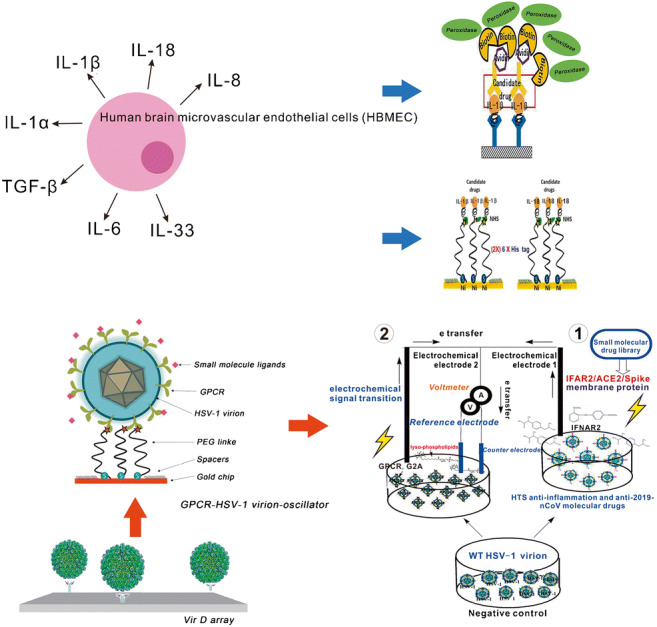

High-throughput construction of new ultrasensitive solid cytokine chips for HTS of anti-inflammatory drugs

Because the binding of small-molecule drugs with cytokines will present different binding kinetics and electrochemical signaling, the cytokine solution chip can employ an electrochemical three-electrode system for detecting the electron transfer between the drugs and cytokines, and the effective lead drugs can be screened [20, 22–26, 34–36]. If the IL-1β and IL-18 ae expressed as chimera IL-1β-V5 tag and IL-18-V5 tag, the cytokines can be loaded on the solid glass slide through V5 antibody binding for HTS of molecular drugs based on the ELISA principle. That is, the lead drugs conjugated to the biotin can be screened out by binding the peroxidase-conjugated avidin, which can catalyze the TMB chromogenic reagent to present a blue color for ultrasensitive identification of the lead drugs (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

Construction of new ultrasensitive cytokine and virion chips for HTS of anti-inflammatory drugs or clinical diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory diseases. a Chimera cytokine IL-1β-V5 tag and IL-18-V5 tag were highly expressed and were loaded on the solid chip through V5 antibody for HTS of molecular drugs based on the ELISA principle. b Chimera protein IL-1β-6 × His tag (2×) and IL-18-6 × His tag (2×) were expressed and loaded on the Ni-coated solid chip for HTS of molecular drugs of IL-1β cytokines

Remarkably, these cytokines can be tethered to the Ni-coated chip via chelation of (2×) 6 × His tag: Ni, if they expressed as chimera IL-1β-6 × His tag (2×) and IL-18-6 × His tag (2×) (Fig. 4b). By applying an alternating electric field perpendicular to the Ni-coated surface, the variation of the amplitude can characterize the pharmacodynamic activity of the lead drugs (Fig. 4b).

High-throughput construction of the liquid and microfluidic cytokine chips for HTS of anti-inflammatory drugs

If the cytokines were secreted as a cytokine storm, these massive cytokines can be purified individually (Tables 2 and 3). Because lysine is widely present in peptide chains of proteins, the active agent of bovine serum albumin (BSA) can react with these lysines to make them anchor on the BSA-coated glass slide, which exposes the corresponding active groups for HTS of molecular drugs (Fig. 5a).

Fig. 5.

High-throughput construction of the cytokine solution chip for HTS of anti-inflammatory drugs. The drug activity can be characterized either by the settlement of micro-fluid, microgravity condition, Cy-5/Cy-3 labeling or ELISA principle

On the contrary, if the candidate drugs were anchored on the chip surface through the avidin–biotin interaction, the microfluidic chip could be made to let the IL-1β cytokine solution flow through the fixed molecular drugs for HTS of candidate drugs, and identify the lead drugs by mass spectrometry (MS) detection, because a high molecular ion peak can be generated according to charge/mass (m/z) of highly ionized cytokines (Table 2, Fig. 5b).

The candidate drugs can also be labeled by CY-5/CY-3 fluorescent dye for HTS of effective drugs by applying a microgravity field [26]. IL-1β/IL-18 cytokine drug screening has broad application for the diagnosis and treatment of inflammasome-related diseases, including auto-inflammatory disorders, Crohn’s disease, vitiligo, gout, asbestosis, Alzheimer’s disease and even tumors (Fig. 5c).

Recombinant herpes virion liquid electrochemical sensor can be fabricated by high-throughput construction for HTS of anti-inflammatory drugs or clinical diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory diseases

Different molecular drug targets will generate variable electrochemical signaling for monitoring, due to the different structural properties of single transmembrane (IFNAR2) and multi-transmembrane protein (GPCR)

As just mentioned above, YojI binds IFNAR2 and triggers the intracellular anti-inflammatory signaling related to the synthesis and secretion of cytokines IL-1β/IL-18 [1, 2, 7, 8, 15–19]. Thus, the IFNAR2 receptor should retain the anti-inflammatory properties, which can be utilized for molecular drug docking and screening. A model can be used to explain the drug effectiveness: If the drug binds the single transmembrane protein IFNAR2, it mostly binds the extracellular chain (27-243aa) of IFNAR2 to exert its pharmacological activity. However, if the drug binds GPCR with seven-transmembrane domains, it can bind different loops of GPCR or the N-terminal of this protein receptor to perform its pharmacological activity (Fig. 6a). The different binding sites between the IFNAR2 and GPCR will generate different electrochemical signaling for monitoring, which is our primary interest.

Fig. 6.

High-throughput construction of a liquid electrochemical sensor integrated with recombinant membrane protein virions for HTS of anti-infective and anti-inflammatory drugs (2019-novel coronavirus/human/bacteria) and clinical diagnosis of inflammatory diseases. a Molecular drugs target different sites of transmembrane proteins: small drugs bind the extracellular domain of IFNAR2, N-terminal domain or different loops of seven-transmembrane domain protein receptor G2A (loop i, loop ii, loop iii); the membrane protein interaction between Spike (trimer) and ACE2 (dimer). b The IFNAR2/ACE2/Spike and GPCR-recombinant herpes virion solution (IFNAR2/ACE2/Spike-HSV-1 and GPCR-HSV-1) can be applied to fabricate the new virion liquid electrochemical sensor for HTS of anti-inflammatory drugs or clinical diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory diseases, especially for the prevention and cure of 2019-novel coronavirus pneumonia

(IFNAR2/ACE2/Spike)-HSV-1 and (GPCR)-HSV-1 can be rapidly replicated for high-throughput construction of the recombinant virion liquid electrochemical sensor

Due to the similar single-transmembrane structure between Spike of 2019-nCoV, ACE2 of alveolar epithelial cells II (ATII) and IFNAR2 of HBMEC, the (IFNAR2/IL10RA/ACE2/Spike)-HSV-1 and (GPCR)-HSV-1 can be fabricated and rapidly replicated for high-throughput construction of the recombinant virion liquid sensor. Because the detected solution is a non-aqueous solution, and the IR [Deviation caused by I (current) and R (resistance) of the liquid] is much larger, such as blood and virion liquid, a three-electrode system should be applied, comprising a working electrode, an Ag wire as the quasi-reference electrode and a Pt coil as the counter electrode (Fig. 6b). The electrochemical signal will load on the working electrode and counter electrode which are linked to an electrical access loop for detection of the electron transition and electric current passing through [20, 22–25, 37, 38].

The high-throughput construction of a recombinant virion liquid electrochemical sensor is shown in (Fig. 6) [20, 22–25].

Because the single-transmembrane protein IFNAR2 presents a very long extracellular domain (27–243aa), which is similar to CD4 and IFNAR2, Spike (14–1195aa) of 2019-nCoV and ACE2 (18-740aa) of alveolar epithelial cells II, they can be very easily incorporated into the envelope of HSV-1 under the glycoprotein B promotor of the HSV-1 genome to make the IFNAR2/ACE2/Spike-HSV-1 and GPCR recombinant virions (www.uniprot.org) [1, 2, 20, 21, 26]. Therefore, the IFNAR2/ACE2/Spike and GPCR-recombinant herpes virions (IFNAR2/ACE2/Spike-HSV-1 and GPCR-HSV-1) can be created through high-throughput construction to obtain a new virion solution electrochemical sensor for probing drug activity. The applied electrochemical sensor is very sensitive for monitoring electron transition of IFNAR2/IL10RA/ACE2/Spike/GPCR-molecular drug interaction in a small area of the virion solution, which can be compared with the electrical signal of the negative control virions (wild-type virions without IFNAR2/IL10RA/ACE2/Spike or GPCR incorporation) to gain electrical signaling of clinical diagnosis and to identify effective drugs (Fig. 6b) [2, 9, 10, 21, 26–32].

In previous studies, recombinant purified virions were arrayed in a 384-well plate and spotted on FAST slides (Whatman) in a 4 × 4 pattern to fabricate the virion display (VirD) array in order to profile functional membrane proteins using the Cy5-labeled antibody, ligand and lectin to detect immunofluorescence intensity for characterization of their structure and activity (Fig. 1) [2, 20, 21]. Next, virion nano-oscillators were made to allow us to measure mobility and charge changes associated with molecular binding strength on each recombinant virion, characterized by the variation in binding kinetics and amplitude (Fig. 3). These novel analytical characterization approaches and real-time photoelectric measurement techniques provide us a new reference of theoretical analysis for the construction of the recombinant virion liquid electrochemical sensor. It can be applied not only in the detection of infectious diseases (patient blood sample that has been immunized with antibodies of bacteria/virus/2019-nCoV), but also in the detection of diabetes, obesity, tissue injury, acute or chronic inflammation (pancreatitis or rheumatoid arthritis), cardiovascular disease and tumors (Fig. 6b). Subsequently, the screened drugs can be docked to the protein receptors on the virion envelope for designing highly effective anti-inflammatory drugs based on their crystal structure with computer-aided drug design. Because of the flexibility of the VirD platform, we can co-infect human cells with more than one type of VirD-GPCR to produce chimera, heterodimer or multimer VirD-GPCRs to establish the multifunctional virion liquid electrochemical platform for HTS of molecular drugs and the clinical diagnosis and treatment of infectious and inflammatory diseases.

Anti-inflammatory and anti-2019-nCoV drugs can be developed

If we have identified the drugs with strong effectiveness by the virion and cytokine liquid chips, we can obtain the drug-recombinant virion crystal structures to design and modify the drugs based on the membrane protein receptor structure and their electronic binding properties [39–41]. Both the membrane protein receptors (Fig. 6a) and the transcription factor NF-kB and NLRP2 proteins can be designed as drugs for blocking the membrane protein interactions or blocking the protein aggregation and DNA binding properties to suppress inflammation in the human body [36, 42].

Conclusions

We have discovered that the YojI-IFNAR2 and YojI-IL10RA membrane protein interactions mediate anti-inflammatory signaling cross-talk, which is related to the NLRP2 protein inhibition of inflammasome-mediated synthesis and secretion of IL-1β and IL-18. This novel unrevealed anti-inflammatory cellular signaling was applied to investigate the high-throughput construction of liquid cytokine chips and for the development of the single (IFNAR2/IL10RA/ACE2/Spike) and multi-transmembrane protein (GPCR) recombinant herpes virion liquid electrochemical sensor (IFNAR2/IL10RA/ACE2/Spike-HSV-1 and GPCR-HSV-1) for HTS of anti-inflammatory drugs or clinical diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory diseases. Recently, the RNA coronavirus 2019-nCoV has posed a serious global public health threat, with death rates increasing every day. The infection occurs mainly through the membrane protein interaction of Spike with ACE2. Because the Spike protein is a trimer and ACE2 is a dimer (Fig. 6a), immune response is of tremendous importance for the production of synthetic antibodies to eliminate the 2019-nCoV pathogen. Thus, the molecular and protein drugs, vaccines (the single-transmembrane protein of Spike and ACE2 which removed the transmembrane domain) and antibodies can be developed to block the Spike and ACE2 membrane protein interaction to inhibit the 2019-nCoV infection (Fig. 1) [34–36, 39–41], which can be gained through recombinant herpes virion-immunized mice. Recently, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) has received much attention. It has been identified as a functional receptor that is related to vasoconstriction, which plays a vital role in the development of hypertension, atherosclerosis and kidney disease, and which requires our further investigation (Fig. 6a). Interestingly, we can knock down the NLRP2 gene to monitor the dynamic conformation variation of ACE2 in response to blood rheology [39]. As a result, studies on the interactions between 2019-nCoV, ACE2 and the host innate immune system, and NLRP2 gene function are critical for infectious, cardiovascular and even tumor disease therapy, and to control serious epidemics. In the future, in addition to microfluidic and electrochemical devices, other advanced physical techniques such as field spectroscopy, quartz microbalance (QCM) and sonic waves can be applied for HTS of drugs. The newly constructed cytokine and virion liquid sensors have significant value for clinical diagnosis and treatment of infectious and inflammatory diseases (Figs. 5 and 6) [27, 36, 42].

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Chengbo Hu, Ying Tang, Liujun He, Yan Tang, Xuelian Lan, Kepeng Ou, Donglin Yang, Yajun Zhang, Min Li and Yue Feng for their advice on this manuscript. We also thank Xinni Jiang, Zhongbin Li, Chaozhong Guo, Zheng Huang and Yafei Luo for providing language editing and technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- 2019-nCoV

2019 Novel coronavirus

- (BBB)

Blood–brain barrier

- BSA

Bovine serum albumin

- CNF1

Cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1

- DR-18

Decoy-resistant IL-18

- E. coli

Escherichia coli

- FACS

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- G2A

G protein-coupled receptor 132

- GlcNAc

N-acetylglucosamine

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- GRASP55

Golgi reassembly stacking protein 55

- HBMEC

Human brain microvascular endothelial cells

- HPLC-MS

High-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

- HSV-1

Herpes simplex virus-1

- HTS

High-throughput screening

- IFNAR2

Interferon alpha/beta receptor subunit 2

- IL

Interleukin

- IL-10RA

Interleukin-10 receptor subunit alpha

- IL-18 BP

IL-18 binding protein

- ISGs

Interferon-stimulated genes

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- M. tb

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- MS

Mass spectrometry

- m/z

Mass/charge

- Ni

Nickel

- NK

Natural killer

- NLRP2

NACHT, LRR and PYD domains-containing protein 2

- OmpA

Outer-membrane protein A

- ORF

Open reading frame

- OS

Oscillatory shear force

- PEG

Polyethylene glycol

- PLA2G5

[Ca2+]-dependent phospholipase A2

- PS

Pulsating shear force

- QCM

Quartz microbalance

- Rab8a

Ras-related protein Rab-8a

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- Th1

T-helper 1

- VCAM-1

Vascular cell adhesion molecule

Biographies

Yingzhu Feng

holds a joint PhD from Chongqing University and Johns Hopkins University (USA), and is Associate Professor (researcher) of the College of Pharmacy & International Academy of Targeted Therapeutics and Innovation (IATTI) at Chongqing University of Arts and Sciences. His work is mainly focused on the construction of the human membrane protein recombinant virus chip for high-throughput screening (HTS) of drugs, and he uses the proteomic chip to carry out research on the interaction between pathogenic bacteria and host cells, and new targeted therapy for tumor.

Jiuhong Huang

is Assistant Professor at the College of Pharmacy & International Academy of Targeted Therapeutics and Innovation (IATTI), Chongqing University of Arts and Sciences. He has been working for several years on molecular signaling pathways in tumor biology. He is experienced in high-throughput drug screening of novel targeted therapy for tumors.

Chuanhua Qu

received his Ph.D. degree in 2017 from Nanjing University. In 2018, he joined Chongqing University of Arts and Sciences. His research interests are mainly focused on visible light-mediated reaction methodology and metal organic synthesis methodology.

Mengjun Huang

is a researcher of College of Pharmacy & International Academy of Targeted Therapeutics and Innovation (IATTI), International Academy of Targeted Therapeutics and Innovation (IATTI) at Chongqing University of Arts and Sciences. He has been working for several years on the development of high-throughput screening technologies (chips, microarray and sequencing) from analyzing gene expression data to discovering potential targets of anti-inflammatory drugs.

Zhencong Chen

is research assistant of the First Hospital Affiliated to AMU in Chongqing, China. He has been working for several years on the development of nano-drug delivery in vivo based on the preparation of nano-spheres and targeting nano-spheres. He is also studying physical and chemical parameters including morphology, size and NMR of nanospheres.

Dianyong Tang

is Professor and doctor of science, Vice President of the College of Pharmacy & International Academy of Targeted Therapeutics and Innovation (IATTI) at Chongqing University of Arts and Sciences. He is also the Vice Director of Chongqing Engineering Laboratory of Innovative Targeted Drugs, a candidate for academic and technical leaders of Chongqing, and member of the Academic Committee of Chongqing University of Arts and Sciences. He is now engaged in computer-aided drug design, molecular simulation and theoretical study of nano-catalytic reaction mechanisms.

Zhigang Xu

is Co-Director of the National & Local Joint Engineering Research Center of Targeted and Innovative Therapeutics, and he is also Co-Director of Chongqing Key Laboratory of Kinase Modulators as Innovative Medicine in Chongqing University of Arts and Sciences. He has been working on small-molecule drug design and chemical methodologies to enable expedited drug development.

Bochu Wang

is Professor and doctoral supervisor of Chongqing University, and an national candidate of the One Million Talents Project in the New Century. He is an expert who enjoys the special allowance of the State Council, and is the Chief expert of Chongqing Expert Studio. He has been awarded a batch of discipline leaders of Biomedical Engineering in Chongqing, and he is also the Head of National Key Discipline of Biomedical Engineering. He now serves as the Director of the Institute of Pharmacy, Chongqing University, Deputy Director of Key Laboratory of Biological Rheology Science and Technology of the Ministry of Education; and Major Director of Chongqing Brain Science Collaborative Innovation Center. He has been working in the biomechanics and biopharmaceutical engineering field for many years, and he is honored to serve as a member of the editorial boards of international magazines such as Coroids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces and Current Pharmaceutical Design.

Zhongzhu Chen

is Head of the College of Pharmacy & International Academy of Targeted Therapeutics and Innovation (IATTI) at Chongqing University of Arts and Sciences, and Director of the National and Local Joint Engineering Research Center of Targeted and Innovative Therapeutics. He serves on the Editorial Board of Molecular Diversity, and is a special expert of the Chongqing Overseas Chinese Federation. He has been engaged in new drug development for many years. He has published more than 40 SCI papers in journals including Cell and Angewandte Chemie International Edition, and he holds more than ten invention patents authored at home and abroad. His research group has revealed the inhibition mechanism on the innate immune RLR signaling pathway by lactate that can effectively promote the production of IFN type I for eliminating RNA virus, and the paper was published in Cell.

Funding

This work was funded by the Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Science and Technology Special Natural Science Fund, Yongchuan district, Chongqing City (YCSTC, 2020nb0219), Talent Introduction Project of College of Pharmacy & International Academy of Targeted Therapeutics and Innovation (IATTI), Chongqing University of Arts and Sciences (R2019SXY12), and Key Laboratory of Biorheological Science and Technology (Chongqing University), Ministry of Education (CQKLBST-2020-004).

Compliance with ethical standards

No animal experiments were performed in this work. It is in compliance with ethical standards.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yingzhu Feng, Email: hnxtfyz123@163.com, Email: 20190029@cqwu.edu.cn.

Bochu Wang, Email: wangbc2000@126.com.

Zhongzhu Chen, Email: 389404093@qq.com.

References

- 1.Feng Y, Chen CS, Ho JD, Pearce D, Hu SH, Wang BC, Desai P, Kim KS, Zhu H. High-throughput chip assay for investigating Escherichia coli interaction with the blood-brain barrier using microbial and human proteome microarrays (dual-microarray technology) Anal Chem. 2018;90(18):10958–10966. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b02513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu S, Feng Y, Henson B, Wang B, Huang X, Li M, Desai P, Zhu H. VirD: a virion display array for profiling functional membrane proteins. Anal Chem. 2013;85(17):8046–8054. doi: 10.1021/ac401795y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laela MB, Hal MHCAPS. NLRP3. J Clin Immunol. 2019;39(3):277–286. doi: 10.1007/s10875-019-00638-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swanson KV, Deng M, Ting JP. The NLRP3 inflammasome: molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nat Rev Immunol. 2019;19:477–489. doi: 10.1038/s41577-019-0165-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Novick D, Cohen B, Tal N, Rubinstein M. Soluble and membrane-anchored forms of the human IFN-alpha/beta receptor. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;57(5):712–728. doi: 10.1002/jlb.57.5.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwang SK. Mechanisms of microbial traversal of the blood-brain barrier. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6(8):625–634. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piccioli P, Rubartelli A. The secretion of IL-1β and options for release. Semin Immunol. 2013;25(6):425–429. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of pro IL-1β. Mol Cell. 2002;2:417–426. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dupont N, Jiang S, Pilli M, Ornatowski W, Bhattacharya D, Deretic V. Autophagy-based unconventional secretory pathway for extracellular delivery of IL-1β. EMBO J. 2011;30(23):4701–4711. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eisenbarth SC, Colegio OR, Connor W, Sutterwala FS, Flavell A. Crucial role for the NALP3 inflammasome in the immunostimulatory properties of aluminium adjuvants. Nature. 2008;198(453):1122–1126. doi: 10.1038/nature06939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Junji E, Naomi M, Mitsue TE, Masaaki K, Katsuyuki T, Yuka H, Hikari T, Tsutomu F, Kenji T, Mitsutaka Y, Junichi I, Isei T, Norihiko F, Dong-Mei Z, Norihiro T, Keiji T, Eiki K, Takashi U. Liver autophagy contributes to the maintenance of blood glucose and amino acid levels. Autophagy. 2011;7:727–736. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.7.15371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gee HY, Noh SH, Tang BL, Kim KH, Lee MG. Rescue of DeltaF 508-CFTR traffificking via a GRASP-dependent unconventional secretion pathway. Cell. 2011;146(5):746–760. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peter D, Hajime K, Katey JR, Cherilyn MS, Gregory V, Franz GB, George SA, Luigi F, Gabriel N, Max S, Terje E, Egil L, Katherine AF, Kenneth LR, Kathryn JM, Samuel DW, Veit H, Eicke L. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature. 2010;464(7293):1357–1361. doi: 10.1038/nature08938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duncan CJA, Mohamad SMB, Young DF, Skelton AJ, Leahy TR, Munday DC, Butler KM, Morfopoulou S, Brown JR, Hubank M, Connell J, Gavin PJ, McMahon C, Dempsey E, Lynch NE, Jacques TS, Valappil M, Cant AJ, Breuer J, Engelhardt KR, Randall RE, Hambleton S. Human IFNAR2 deficiency: lessons for antiviral immunity. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(307):307ra154. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac4227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou T, Damsky W, Weizman O, McGeary MK, Hartmann KP, Rosen CE, Fischer S, Jackson R, Flavell RA, Wang J, Sanmamed MF, Bosenberg MW, Ring AM. IL-18BP is a secreted immune checkpoint and barrier to IL-18 immunotherapy. Nature. 2020;583:609–614. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2422-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ana F, Olga G, Jose L, Fernandez L. NLRP2, an inhibitor of the NF-kB pathway, is transcriptionally activated by NF-kB and exhibits a nonfunctional allelic variant. J Immunol. 2007;179:8519–8524. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.12.8519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andrei C, Margiocco P, Poggi A, Lotti LV, Torrisi MR, Rubartelli A, Phospholipases C. A2 control lysosome-mediated IL-1β secretion: implications for inflammatory processes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(26):9745–9750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308558101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsutsumi N, Kimura T, Arita K, Ariyoshi M, Ohnishi H, Yamamoto T, Zuo X, Maenaka K, Park Enoch Y, Kondo N, Shiraka AM, Tochio H, Kato Z. The structural basis for receptor recognition of human interleukin-18. Nat Commun. 2014;15(5):5340. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6340.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schett G, Dayer JM, Bernhard M. Interleukin-1 function and role in rheumatic disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2016. 10.1038/nrrheum.166. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Ma GZ, Syu GD, Shan X, Henson B, Wang S, Desai PJ, Zhu H, Tao N. Measuring ligand binding kinetics to membrane proteins using virion nano-oscillators. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140(36):11495–11401. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b07461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Syu GD, Wang SC, Ma G, Liu S, Pearce D, Prakash A, et al. Development and application of a high-content virion display human GPCR array. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1) 1997. 10.1038/s41467-019-09938-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Seenaa V, Rajorya A, Pant P, Mukherji S, Rao VR. Polymer microcantilever biochemical sensors with integrated polymer composites for electrical detection. Solid State Sci. 2009;11:1606–1611. doi: 10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2009.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li MR, Deng CY, Xie QJ. Electrochemical quartz crystal impedance study on immobilization of glucose oxidase in a polymer grown from dopamine oxidation at an au electrode for glucose sensing. Electrochim Acta. 2006;51:5478–5486. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2006.02.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mao X, Jiang JH, Luo Y. Copper-enhanced gold nanoparticle tags for electrochemical sriipping detection of human lgG. Talanta. 2007;73:420–424. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manso J, Mena ML, Yaez-Sedeo P, Pingarrón J. Electrochemical biosensors based on colloidal gold-carbon nanotubes composite electrodes. J Electroanal Chem. 2007;603:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2007.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feng Y, Wang B, Chu X, Wang Y, Zhu L. The development of protein chips for high throughput screening (HTS) of chemically labeling small molecular drugs. Mini-Rev Med Chem. 2016;16(10):846–850. doi: 10.2174/1389557515666150511152922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feng Y, Xie Z, Jiang X, Li Z, Shen Y, Wang B, Liu J. The applications of promoter-gene-engineered biosensors. Sensors. 2018;18(9):2823. doi: 10.3390/s18092823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cai WZ, Person S, DebRoy C. Gu BH. Functional regions and structural features of the gB glycoprotein of herpes simplex virus type 1. An analysis of linker insertion mutants. J Mol Biol. 1988;201(3):575–588. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90639-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Desai P, Sexton GL, Huang E, Person S. Localization of herpes simplex virus type 1 UL37 in the Golgi complex requires UL36 but not capsid structures. J Virol. 2008;82(22):11354–11361. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00956-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Desai PJ, Pryce EN, Henson BW, Luitweiler EM, Cothran J. Reconstitution of the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus nuclear egress complex and formation of nuclear membrane vesicles by coexpression of ORF67 and ORF69 gene products. J Virol. 2012;86(1):594–598. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05988-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wells AD, Walsh MC, Sankaran D, Turka LA. T cell effector function and anergy avoidance are quantitatively linked to cell division. J Immunol. 2000;165(5):2432–2443. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fernandez GM, Moore CD, Schulz KN, Alberto O, Donague G, Harrison MM, Zhu H, Zaret KS. Structural features of transcription factors associating with nucleosome binding. Mol Cell. 2019;75:30442–30443. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamaguchi M, Samuchiwal SK, Quehenberger O, Boyce JA, Balestrieri B. Macrophages regulate lung ILC2 activation via Pla2g5-dependent mechanisms. Mucosal Immunol. 2018;11:615–626. doi: 10.1038/mi.2017.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fraser DA, Laust AK, Nelson EL, Tenner AJ. C1q differentially modulates phagocytosis and cytokine responses during ingestion of apoptotic cells by human monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2009;183(10):6175–6185. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fan XD, White IM, Shopove SI, Zhu H, Suter JD, Sun Y. Sensitive optical biosensors for unlabeled for unlabeled targets: a review. Anal Chim Acta. 2008;620(1-2):8–26. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2008.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Usacheva A, Kotenko S, Witte MM, Colamonici OR. Two distinct domains within the N-terminal region of Janus kinase 1 interact with cytokine receptors. J Immunol. 2002;169(3):1302–1308. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.3.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosengren B, Jonsson-Rylander AC, Peilot H, Camejo G, Camejo EH. Distinctiveness of secretory phospholipase A2 group IIA and V suggesting unique roles in atherosclerosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761(11):1301–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barbara B, Arm JP, Group V sPLA2: classical and novel functions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1761(11):1280–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yan RH, Zhang YY, Li YL, Xia L, Guo YY, Zhou Q. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science. 2020;367(6485):1444–1448. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang C, Shang G, Gui X, Zhang X, Bai XC, Chen ZJ. Structural basis of STING binding with and phosphorylation by TBK1. Nature. 2019;567:394–398. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1000-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li S, Zheng S, Tang S, Pan Y, Zhang S, Fang H, Qiao JJ. Autoinflammatory pathogenesis and targeted therapy for adult-onset Still’s disease. Clin Rev Allerg Immu. 2020;58:71–81. doi: 10.1007/s12016-019-08747-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu Y, Wei Q, Yu J. The cGAS/STING pathway: a sensor of senescence-associated DNA damage and trigger of inflammation in early age-related macular degeneration. Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14:1277–1283. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S200637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]