Abstract

Background: One of the many debated topics in inflammation research is whether this scenario is really an accelerated form of human wound healing and immunity-boosting or a push towards autoimmune diseases. The answer requires a better understanding of the normal inflammatory process, including the molecular pathology underlying the possible outcomes. Exciting recent investigations regarding severe human inflammatory disorders and autoimmune conditions have implicated molecular changes that are also linked to normal immunity, such as triggering factors, switching on and off, the influence of other diseases and faulty stem cell homeostasis, in disease progression and development.

Methods: We gathered around and collected recent online researches on immunity, inflammation, inflammatory disorders and AMPK. We basically searched PubMed, Scopus and Google Scholar to assemble the studies which were published since 2010.

Results: Our findings suggested that inflammation and related disorders are on the verge and interfere in the treatment of other diseases. AMPK serves as a key component that prevents various kinds of inflammatory signaling. In addition, our table and hypothetical figures may open a new door in inflammation research, which could be a greater therapeutic target for controlling diabetes, obesity, insulin resistance and preventing autoimmune diseases.

Conclusion: The relationship between immunity and inflammation becomes easily apparent. Yet, the essence of inflammation turns out to be so startling that the theory may not be instantly established and many possible arguments are raised for its clearance. However, this study might be able to reveal some possible approaches where AMPK can reduce or prevent inflammatory disorders.

Keywords: IL-1β, immunity, inflammation, NF-κB and AMPK, TNF-α, autoimmune diseases, inflammatory disorders

1. INTRODUCTION

World population is increasing at an alarming rate; therefore, new problems have been created in many areas, including jobs, shelter and, most importantly, foods. To fulfill the demand for food, the planting or cultivation of genetically modified foods is being encouraged, which may create some new health-related problems [1, 2]. Owing to break- throughs in technology, many people play and work at home nowadays. In addition, most of the corporate offices are filled with lifts and air conditioners, which make people engage in less physical exertion [3, 4]. Altogether, these are factors that contribute to several dysfunctions, including obesity, diabetes, vascular dysfunction, related metabolic syndrome and several inflammatory disorders [5].

Evidences suggest that inflammatory responses are highly correlated with many diseases. Over-activation of the immune cells and pro-inflam- matory cytokines can lead a subject to become diabetic. In addition, harmful cytokines aggravate the situation of an already diabetic subject and make treatment approach more complex [6]. In obesity, factors such as adipocytes, adiponectin and adipokines work as a gland to produce and secrete several soluble components that have direct and indirect connections with the inflamma- tory response. Inflammatory cascades may be invited, which then develop in the gathering of the foam cells and ultimately engage in the major role of complicating the scenario through processes such as coronary arterial calcification, atherosclerosis progression and heart failure [7]. Besides, every infection does some damage in the body and these damages invite immune cells and harmful inflammatory cytokines in the respective areas [8] On the other hand, aging has been blamed as a major phenomenon where the body tends to become less responsive to endoplasmic stress, apoptosis, oxidative stress and autophagy, making the body find it difficult to control hyperglycemia, visceral fats, metabolic syndromes and, most importantly, inflammation. Chronic inflammation depletes several necessary components such as Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)/ SKiNhead-1 (SKN1), Sirtuin (SIRT1), Unc-51 Like Autophagy Activating Kinase 1 (ULK1), Sestrins, p53, Heme oxygenase (HO-1), Forkhead box protein O (FoxO)/Aafachronic Acids (DAF) 16, Liver kinase (LK) B1, Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMKK) β and Transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1). On the contrary, the levels of harmful components and pathways, for instance, Protein phosphatase 2Cα (PP2Cα), Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), CREB-regulated transcription coactivator 1 (CRTC1) and Nuclear Factor (NF)-κB are always activated [9]. Overproduction of inflammatory cells and pro-inflammatory cytokines are often reported in chronic illnesses such as Parkinson’s disease, stroke, thrombosis, hypertension, cirrhosis, Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), skin disorders, edema, fibrosis, iron overload, Alzheimer’s and cancers [10, 11].

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a prime energy sensor as a whole-body level, activated under conditions of glucose deprivation, heat shock, oxidative stress, and ischemia. It is also responsible for immune response, cell growth and polarity. Once activated, AMPK suppresses the necessary enzymes involved in ATP-consuming anabolic pathways and enhances cellular ATP supply [12, 13]. There are several bodily ways to trigger AMPK, such as regular and intense exercises, intermittent fasting and being stress-free, hence, the expressions of AMPK have been noticed in various cells, including hepatocytes, adipocytes, macrophages, smooth muscle cells, microglia cells, endothelial cells, glioma cells, cardiomyocytes and various cancer cells [14]. Resveratrol from either red wine or grape; Quercetin from many plants including fruits, vegetables, and grains; epigallocatechin-3-gallate from green tea and fatty fish like cod liver oil, salmon and trout fish are all-natural resource that, taken together, also stimulate AMPK [15]. Several anti-inflam- matory mechanisms of AMPK have been proposed so far, and it is mostly believed that AMPKα2 provides its anti-inflammatory effects through PARP-1 and Bcl-6 in the molecular levels [16]. On the other hand, exploring the appliance of genetic methods, mapping and a plethora of AMPK enhancers, rapid progress has demonstrated AMPK as an attractive therapeutic target for several human ailments, such as end-stage renal diseases, atherosclerosis, hepatitis, myocardial ischemia/re- perfusion injury, cancer and neurodegenerative disease [17]. Activation of AMPK can facilitate bacterial eradication in sepsis and related inflammatory conditions associated with the inhibition of neutrophil activation and chemotaxis [18]. Activation of AMPK also inhibits NF-κB signaling and inflammation although the mechanism is not direct; hence, it has a positive impact on health and lifespan [19]. Furthermore, inflammatory pathways are highly interconnected; therefore, inhibiting one cascade may be associated with blocking other inflammatory pathways, which makes the anti-inflammatory activity entirely dependent on other factors. In this study, we outlined the major molecular and biochemical pathways that contribute to the crosstalk between AMPK and inflammatory mediators. Our hypothetical figure legends and tables may correlate and establish interaction between AMPK and inflammation. This review outlines the principal mechanisms that govern the effects of inflammation, immunity and tumor development. It discusses attractive new targets for cancer therapy and prevention.

2. METHODOLOGIES

An interesting question that remains to be answered is whether or not AMPK can inhibit inflammatory pathways and responsible cytokines. The answer requires extended literature searching and establishes the various direct and indirect correlation between pathophysiology and AMPK interaction in human health and improving life-span. Therefore, our aim was to find molecular mechanisms responsible in inflammation research and to inhibit the pathways by AMPK inducers; therefore, the current study was designed depending on latest literatures which were published since January 2010 and of course with some exceptions. To collect the literatures, PubMed, Google Scholar, Science Direct and Scopus were basically searched and retrieved. A lot of short keywords like AMPK, neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, inflammatory cytokines, myocarditis, diabetes, nephritis, hepatitis, obesity, vasculitis and fat metabolizing genes were used to investigate the literatures. Both the natural and synthetic sources have been shown in Tables 1 and 2 to correlate the possible AMPK inducers or enhancers. Several possible biochemical pathways have been hypothesized to find out the possible pathophysiology and treatment approach between inflammatory disorders and applications of AMPK in various conditions. We included all qualitative and quantitative study types, including animal model and cell culture. Meta-analysis was not used as this review was primarily designed to provide a comprehensive overview of the field.

Table 1.

Natural sources of AMPK enhancers.

| Treatment Name | Applications/Outcomes of the Experiment | References |

|---|---|---|

|

Common Name: Yuja or Yuzu Scientific Name: Citrus junos Used parts: Peel extract |

-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activities were increased by Ethanol extract of yuja peel (YPEE) in a dose-dependent manner inside in both cell culture and mouse models. | [60] |

|

Name of the Plant: Korean red pepper Scientific Name: Capsicum annuum Used parts: An ethanol (70%) extract of Korean red pepper (Ekrp) |

-Ethanol (70%) extract of Korean red pepper enhances AMPK phosphorylationin 3T3-L1 adipocyte. | [61] |

|

Common Name: Hsiao Scientific Name: Astragalus membranaceus Bunge var. mongholicus Used parts: Astragalus polysaccharide extract |

-Astragalus polysaccharide interacted with AMPK activity in palmitate-induced RAW264.7 cells. | [62] |

|

Common Name: Thymoquinone Scientific Name: Nigella sativa Used parts: Seeds |

-Thymoquinone enhanced the phosphorylation adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in male Kunming mice. | [63] |

|

Name of the Plant: Bitter melon Scientific Name: Momordica charantia Used parts: 5β,19-epoxy-25-methoxy-cucurbita-6,23-diene-3β,19-diol (EMCD) |

-EMCD was found to have activated AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in TNF-α-induced inflammation in FL83B cells. | [64] |

|

Name of the Plant: Berberis and Coptis Scientific Name: Berberis aquifolium and Coptis chinensis Used parts: Raw Berberine |

-Berberine increased AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)/gluconeogenesis pathway in diabetic rat and HepG2 hepatocytes. | [65] |

|

Name of the Plant: Licochalcone Scientific Name: Glycyrrhiza inflata (G. inflata) Used parts: Licochalcone root |

-Licochalcone increased AMPK phosphorylation and Sirt1 expression in HepG2 cells. | [66] |

|

Name of the Plant: Sasa (bamboo) Scientific Name: Sasa borealis Used parts: Sasa borealis leaf extract |

-Sasa borealis leaf extract helped in the activation of the AMP-activated protein kinase in STZ-induced diabetic mice. | [67] |

|

Name of the Plant: Glabridin Scientific Name: Glycyrrhiza glabra Used parts: Raw Glabridin |

-AMPK activation with Glabridin was reported in (C57BL/6J strain) mice. | [68] |

|

Common Name: Tea Scientific Name: Cyclocaryapaliurus Used parts: Cyclocaric acid B and Cyclocarioside H |

-Cyclocaric acid B and Cyclocarioside H showed AMPK underlying mechanisms in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. | [69] |

|

Name of the Plant: Black ginseng Scientific Name: Panax ginseng C. A. Meyer Used parts: Black ginseng ethanol extract |

-Black ginseng extract improved AMPK protein activity in db/db mice. | [70] |

|

Name of the Plant: Katsura or Caramel Scientific Name: Cercidiphyllum japonicum Used parts: N/A |

-Dihydromyricetin improved AMPK signaling pathway in high fat diet-fed rats. | [71] |

|

Common Name: N/A Scientific Name: Boussingaultigracilis Miers var. pseudobaselloides Bailey Used parts: N/A |

-BEG increased phosphorylation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in high-fat diet-induced obese rats. | [72] |

|

Name of the Plant: Wormwood Scientific Name: Artemisia scoparia and Artemisia santolinaefolia Used parts: Artemisia scoparia and Artemisia santolinaefolia extract |

-The extracts increased phosphorylation of AMPK α1 and AMPK activity significantly in DIO C57/B6J mice. | [73] |

|

Common Name: Exopolysaccharides Scientific Name: Enterobacter cloacae (E. cloacae) Z0206 Used parts: Selenium-enriched exopolysaccharides |

-Selenium-enriched Exopolysaccharides interacted with AMPK/SirT1 pathway in high-fat-diet induced diabetic KKAy mice. | [74] |

|

Name of the Plant: Compositae Scientific Name: Atractylodes Macrocephala Koidz Used parts: The dried rhizome of Baizhu |

-The compounds of Baizhu were associated with activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) and PI3K/Akt pathways in mouse skeletal muscle C2C12 cells. | [75] |

|

Name of the Plant: Cucurbitaceae Scientific Name: Bryonia alba. L. Used parts: Cucurbitacin E |

-Cucurbitacin E induced autophagy via upregulating AMPK activity in ATG5-knocked down cells and DU145 cells. | [76] |

|

Name of the Plant: Figor Nopal or Prickly-pear cactus Scientific Name: Opuntia ficus-indica var. saboten Used parts: Fruit |

-Opuntia ficus-indica var. saboten improved peripheral glucose uptake through activation of AMPK/p38 MAPK pathway in db/db mice. | [77] |

|

Name of the Plant: Bitter Orange Scientific Name: Citrus aurantium Used parts: Polymethoxy flavonoids (Nobiletin and Tangeretin) |

-Citrus aurantium extract (Nobiletin and Tangeretin) enhanced phosphorylation of AMP‐activated protein kinase (AMPK) in male C57BL/6 mice. | [78] |

|

Name of the Plant: Ellis fruit Scientific Name: Gardenia jasminoides Ellis Used parts: Geniposide |

-Geniposide activated AMPK production in HepG2 Cells. | [79] |

|

Common Name: Chitin Source: Shrimps, Crabs and Insects Used parts: Chitosan oligosaccharide |

-Chitosan oligosaccharide prevented the development of aberrant crypt foci in a mouse model of colitis-associated colorectal cancer via a mechanism involving AMPK activation. | [80] |

|

Name of the Plant: Sophocarpine Source: Foxtail-like sophora herb and seed Used parts: Seeds |

-Sophocarpine alleviated hepatocyte steatosis through activating AMPK signaling pathway in pathogen-free male SD rats. | [81] |

|

Name of the Plant: Wild Hop Scientific Name: Humulus japonicus Used parts: Humulus japonicus extract |

-Humulus japonicus activated AMPK-SIRT1 pathway in Yeast and human fibroblast cells | [82] |

|

Name of the Plant: Rosemary Scientific Name: Rosmarinus officinalis L. Used parts: Rosmarinus officinalis L. extract |

-Rosemary extract triggered activating AMPK and PPAR pathways in HepG2 cells. | [83] |

|

Name of the Plant: Bitter Melon Scientific Name: Momordica charantia Used parts: Bitter Melon Triterpenoids |

-Activation of AMPK was noticed by Bitter Melon Triterpenoids in L6 myoblasts. | [84] |

|

Common Name: Quercetin Source: Onions, Apples, Tea, Berries, Cauliflower, and Red wine Used parts: Quercetin-3-O-glucuronide |

-Quercetin was involved in a manner dependent on AMPKα1/2 pathway activation in high fat diet mice. | [85] |

|

Common Name: Naringin Source: Citrus fruits Used parts: Fruit’s Albedo, membrane and pith |

-Naringin was associated via Interacting with AMPK activation in osteoblast-like UMR-106 cells | [86] |

Table 2.

Synthetic molecules which enhance AMPK activation.

| Used Components | Applications/Outcomes of the Experiment | References |

|---|---|---|

| Name of the Chemical: A-769662 | -AMPK-α1 was activated. | [56] |

| Name of the Chemical: AA005 | -AMPK activation was noticed causing by 2-deoxyglucose regulation. |

[112] |

| Name of the Chemical: AICAR | -The treatment resulted in significant induction AMPK inside melanoma cells. | [113] |

| Name of the Chemical: TSC2-pS1387 | -AMPK is induced upon insulin induction in Raptor knockdown cells. | [114] |

| Name of the Chemical: Rb2 and Rd | -The phosphorylation of AMPK was increased by Rb2 in HepG2 cells. | [115] |

| Name of the Chemical: Baicalin | -Baicalin activated CaMKKβ/AMPK/ACC pathway in a dose-response pattern in high fat diet-induced obese animal. | [116] |

| Name of the Chemical: Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids | -Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids activation of AMPK/SIRT1 pathway was noticed in Macrophage. | [117] |

| Name of the Chemical: Tangeretin | -Regulation of AMPK signaling pathways in C2C12 myotubes was reported in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. | [118] |

| Name of the Chemical: Oleuropein | - Oleuropein activated AMPK in C2C12 muscle cells. | [119] |

| Name of the Chemical: Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analog Liraglutide | -Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analog Liraglutide induced AMPK dependent mechanism Endothelial cell. | [120] |

| Name of the Chemical: Sildenafil | - Sildenafil enhanced mechanism in a demyelination model. | [121] |

| Name of the Chemical: Curcumin | -Curcumin induced AMPK–SREBP signaling pathway in Streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetic rats. | [122] |

| Name of the Chemical: Metformin and Telmisartan | -Activation of the AMPK-PARP1 cascade was observed by Metformin and Telmisartan. | [123] |

| Name of the Chemical: Lipoic acid | -Lipoic acid triggered AMPK production in adipose tissue of low- and high-fat-fed rats. | [124] |

| Name of the Chemical: Mangiferin | -Activation of AMPK was reported by Mangiferin in hyperlipidemic rats. | [125] |

| Name of the Chemical: Capsaicin | -Capsaicin interacted with reactive oxygen species (ROS)/AMPK/p38 MAPK pathway. | [126] |

| Name of the Chemical: ETC-1002 | -ETC-1002 responded LKB1-dependent activation of macrophage AMPK. | [127] |

|

Name of the Chemical: CTRP1 Protein |

-CTRP1 protein enhanced AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activation in diet-induced weight gain in mice. | [128] |

| Name of the Chemical: Compound K | -Compound K interacted with AMPK/JNK pathway in type 2 diabetic mice and in MIN6 β-cells. | [129] |

| Name of the Chemical: Ramipril | -Ramipril interacted with CaMKKβ/AMPK and Heme Oxygenase-1 activation in cultured human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs) and a type-2 diabetic animal model. | [130] |

| Name of the Chemical: Compounds designated as 4a, 4b, 4h, 4j, 4k, 4z, 4aa, 4bb | -Compounds potently activated AMPK against colorectal cancer stem cells. | [131] |

| Name of the Chemical: Imiquimod | -Imiquimod activated AMPK in skin cancer cells. | [132] |

| Name of the Chemical: Tris (1, 3-dichloro-2-propyl) phosphate (TDCIPP) | -TDCIPP promoted AMPK/mTOR/ULK1 pathways in SH-SY5Y cells. | [133] |

| Name of the Chemical: Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) | -FGF21 activates AMPK signaling in hepatic cells. | [134] |

| Name of the Chemical: Pterostilbene | -Activation of AMPK was found by Pterostilbene in human prostate cancer cells. | [135] |

| Name of the Chemical: Thalidezine | -Thalidezine acted as AMPK activator in apoptosis-resistant cells. | [136] |

| Name of the Chemical: Rutaecarpine and its novel analogues (R17 and R18) | -Rutaecarpine analogues helped in AMPK activation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. | [137] |

| Name of the Chemical: Nitroxoline | -Nitroxoline showed a crucial role on AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway in both hormone-sensitive (LNCaP) and hormone-refractory prostate cancer cells (PC-3 and DU-145). | [138] |

| Name of the Chemical: Fidarestat | -Fidarestat regulated mitochondrial Nrf2/HO-1/AMPK pathway in colon cancer cells. | [139] |

| Name of the Chemical: Methylisoindigo | -Meisoindigo activated AMPK cascade in primary PDAC cell line. | [140] |

| Name of the Chemical: (E)-3-(4-chlorophenyl)-N-(7-hydroxy-6-methoxy-2-oxo-2H-chromen-3-yl) acrylamide (SC-III3) | -SC-III3 activated AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway by acting on mitochondria in human hepatoma HepG2 cells. | [141] |

| Name of the Chemical: Betulinic acid | -AMPK siRNA was observed in the microglial polarization. | [142] |

3. IMMUNITY, INFLAMMATION AND AUTOIMMUNE DISEASES

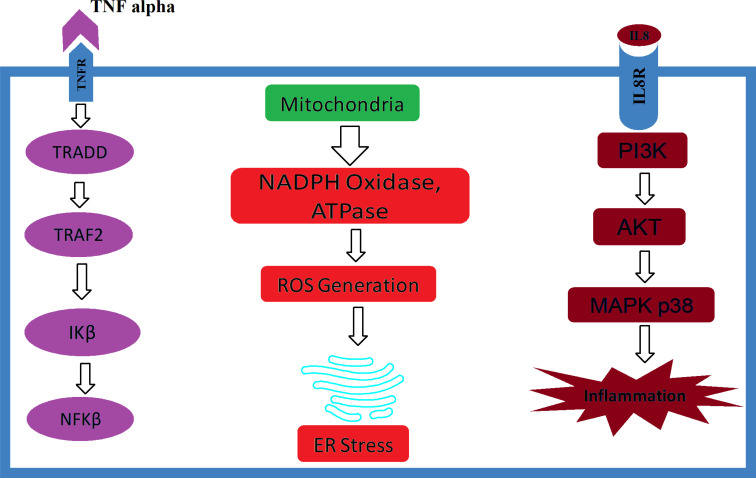

Having any kind of inflammatory response in a biological system explains the ultimate preventive and protective mechanisms that keep the body safe and active in response to harmful stimuli. Inflammatory defenses can be initiated either against live organisms or dead components [20, 21]. However, a disease may be initiated when an inflammatory cascade system persists for a longer time in a particular tissue or an organ. The acute scenario generally ends with necrosis of the tissue; conversely, chronic inflammation may eventually be responsible for end-stage organ dysfunctions [6, 22]. Followed by systemic exposure, cardiovascular inflammation is the most common reason for cardiac failure. Vascular inflammatory responses often initiate several pathological conditions such as myocardial infarction, systemic hypertension, atherosclerosis, cardiomyopathy, myocarditis and, in extreme cases, heart failure. Biological investigations show increased cardiac markers, for instance, uric acid, creatine kinase (CK)-MB, α-troponin, Xanthine oxidase (XO), inducible NOS, Lactase dehydrogenase (LDH), Myoglobin and Protein kinase C [23, 24]. Inflammatory components like macrophages, monocytes, T-lymphocytes, natural killer cells, mast cells, helper cells and dendritic cells are reported in end-stage renal diseases. Harmful cytokines such as activator protein-1, transforming growth factors-β, interferon-γ, nuclear factor-κB, tumor necrosis factor-α, and various clusters of differentiation (Fig. 1) are evaluated in the kidney dysfunction subjects [6]. Elevated markers such as Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST), Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP), Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT), Bilirubin and Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase (iNOS) have been associated with Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH) and NAFLD subjects. Besides, Toll-Like Receptor (TLR), Interleukin (IL), Transforming Growth Factor (TGF), Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) and Activator Protein (AP) also have been reported in liver damage models [25]. Cytotoxic T-cells and natural killer cells have been linked with pancreatic damage, making the subject to become diabetic [26]. Brain inflammation, on the other hand, is very specific and has been associated with cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease, as well as Parkinson’s disease when excess inflammatory cytokines are reported in the central nervous system [27]. Inside the bone, overexpression of harmful immune cytokines such as uric acid, Xanthine oxidase TNF-α, Macrophage Inflammatory Protein (MIP) and IL-6 has been associated with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, which lead to osteoporosis [28]. In the alimentary tract, stimulations like Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs), foods and microorganisms may be involved in inducing several health-related issues, for instance, gastritis, inflammatory bowel syndrome, ulcers and esophagitis [29]. Chronic inflammation may turn into cancers in the longer run. Unwanted immune cells and cytokines are seen in the tumor’s surroundings and are more likely to accord with tumor growth progression, and immune-suppression than they are to mount an effective host anti-tumor response. Around the tumor environment, inflammatory cells serve as “fuel that feeds the flames,” which helps the tumor cells to be resistant and survive. Cancer severity and susceptibility may be linked with fundamental polymorphisms of inflammatory cytokine mRNA or genes, and inhibition or deletion of inflammatory cytokines prevents the development of experimental cancer [30]. Furthermore, inflammatory cells have also been reported to reject an organ immediately after the transplant or in the long run [31].

Fig. (1).

Role of inflammatory cytokines on various cellular components.

On the other hand, overexpression of inflammatory cells and cytokines can also get worse in other diseases, which can make other therapies less effective. Investigations suggested that immune cells are highly migratory, causing excess cells and cytokines to move around and interfere with other systems and thereby start a new problem in the migratory area. Besides, antibodies can be life-threatening for the host when they fight against their own host. Both innate and adaptive immunities are responsible for developing autoimmune diseases [32]. There are hundreds of autoimmune diseases that have been reported so far and have emerged as a serious headache for contemporary healthcare practitioners. Chronic inflammation is the most common factor and might accelerate in the progression of various autoimmune diseases, including psoriasis [33], lupus erythematosus [34], Addison’s disease [35], Graves' disease [36], Hashimoto's thyroiditis [37], autoimmune hepatitis [38], type-1 diabetes [39], rheumatoid arthritis [40], celiac disease [41], Sjögren syndrome [42], polymyositis [43], Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma [44] and many more.

4. IS INFLAMMATION GOOD OR BAD?

Immunity, inflammation and inflammatory diseases have been recognized since the beginning of recorded medical knowledge and practice. Inflammation is a process of complex biological representation to cellular damage caused either by necrosis or infection or lysis, in which the feedback system by the immune system endeavors to neutralize or eliminate injurious stimuli and starts wound healing and regenerative processes [21, 25]. For instance, interleukin-6, a key tumor-pro- moting inflammatory marker generated by innate immunity, signals, at least, three regeneration-promoting transcription factors such as Notch protein, yes-associated protein 1 (YAP), and Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), which are also involved in stem cell activation in both autocrine and paracrine systems. However, it has been found that inflammation is more evolutionarily ancient and is triggered by foreign invaders such as viral structures, known as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), or normal cellular constituents secreted upon injury and cell death, known as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). Both DAMPs and PAMPs are identified by pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs); most of these belong to the toll-like receptor family [45, 46]. To initiate a wound-healing mechanism in the injured area, the recruitment of immune cells and related soluble factors must be accumulated. This process may be accelerated with the involvement of cell cytokines and related markers. Along with leukocyte migration at almost any site of inflammation, monocyte recruitment around the wounds involves the chronological steps of trans-migration, endothelial cell activation and cell-to-cell interaction through the endothelium into the extra-vascular space although sometimes monocytes became a resident cell in tissues and not suffer migration. As monocytes represent only about three percent of circulating leukocytes, the rate of monocyte influx around wounds is far from stochiometric. Initially, monocytes like antigen-presenting cells and neutrophils may be recruited by factors produced rapidly once the injury occurred. From the wound, many soluble factors from the coagulation cascade, markers released from platelet degranulation, and related activated complement components. Another significant group of chemoattractants that are generated from the wound is the chemokines, a group of related small and soluble proteins that display highly conserved cysteine amino acid residues. Chemokines can be released by many cell types and individual chemokines may preferentially recruit particular populations [47, 48]. All these cells have the ability to invade the injury site by squeezing their sizes. Vascular permeability is increased due to heat generation in the area. Similarly, fluid retention may be more as more cells are recruited. Owing to increasing heat or fever, the antibody might be produced faster and transported into the injured area. Wound healing may be possible due to the onset of the accumulation of immune cells and the initiation of inflammation; hence, sometimes the situation can be deleterious if the production and recruitment are not switched off after the healing of the injury (Fig. 1). Abnormal and uncontrolled immune cells may be responsible for enhancing autoimmune diseases [49].

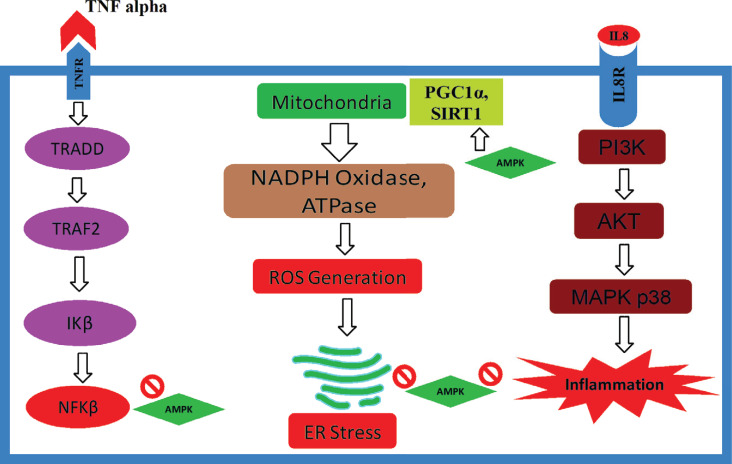

5. AN INTRODUCTION OF AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is also known as a cellular and biochemical energy sensor and is activated when intracellular energy is reported to be insufficient or low. It has also drawn numerous attentions for organismal metabolism and central regulator key source that promotes ATP generation by inducing the expression of many proteins that are involved in the catabolism process during preserving energy while utilizing biosynthetic pathways. Along with regulating metabolic energy balance, AMPK plays a prominent role in maintaining growth and reprogramming metabolism, and recent reports have suggested new connections to biochemical processes like those involving cell polarity and autophagy, which opens new doors in unexplored cellular mechanisms [14, 50]. Among the many beneficial properties of AMPK, free fatty acid, which is synthesized by fatty acid synthase (FAS), is also significantly regulated by AMP-activated protein kinase [51, 52]. It is also known to regulate the energy metabolism counting lipid and glucose metabolism by providing an intracellular energy sensor. This master regulator is basically a heterotrimer that consists of a catalytic subunit α (Alpha) and two regulatory subunits β (Beta) and γ (Gamma) functions [14, 50]. The process is activated by the phosphorylation of Thr172 within α subunit, which is catalyzed by several kinase, for instance, Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase-kinase β (CaMKKβ) and liver kinase B1 (LKB1/STK11) [53]. Sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c) has been identified as a coordinator of fatty acid synthase (FAS) and can be suppressed by the AMPK. SREBP-1c is being considered as a good target owing to have controlling expression of several lipogenic enzymes, that persuade the suppression of FFA synthesis to manage obesity [51, 54]. AMPK signaling has been involved in enhanced stress resistance, energy metabolic homeostasis, and qualified cellular housekeeping, which are the hallmarks of upgraded health and extended lifespan. In addition, AMPK-mediated stimulations such as SIRT1, FoxO/DAF-16 and Nrf2/SKN-1 signaling pathways also improve cellular stress resistance during cellular survival and prevent aging. Moreover, they also control autophagy via mTOR and ULK1 signaling, which improves the quality of cellular housekeeping genes. Furthermore, studies suggest that Protein kinase B (AKT), a prime protein kinase in insulin/IGF pathway, can inhibit AMPK signaling, which demonstrated that AKT increased the phosphorylation of AMPKα1 at Ser485/Ser491, which subsequently prevented the phosphorylation of AMPK at Thr172 by LKB1 and thus suppressed the activation of AMPK [9, 55]. In spite of being the main energy sensor, activation of AMPK enhances heme oxygenase-1 gene expression, which shows the anti-apoptotic effect of AMPK, and this might provide an important adaptive response during survival [56]. The antioxidant effect of AMPK was noticed in several experiments, which may often have the potential of helping the cellular components against free radical-mediated oxidative stress (Tables 1 and 2). AMP-activated protein kinase also significantly reduced free radical components and enhanced the expression of the antioxidant enzymes such as manganese (Mn) superoxide dismutase (SOD), selenium, glutathione and catalase in phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted from chromosome 10 (PTEN) pathways [57]. Involvement of AMKP is also connected with retinal vasodilator by enhancing eNOS and NO-mediated pathway [58]. Taken together, different subunits of AMPK have also been reported to be localized at lysosomes to promote autophagy; activate many upstream kinases such as LKB1, STRAD and CAMKKβ; inhibit several anabolic pathways like the acetyl-CoA carboxylases (ACC1 and ACC2), glycogen synthases (GYS1 and GYS2) and HMGCR; stimulate various catabolic pathways, for instance, TXNIP, PFKFB3 and TBC1D1; promote mitochondrial biogenesis by improving PGC1 family. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) family, TFEB and ULK1 complex; regulate mitochondrial dynamics by interacting with Mitochondrial fission factor (MFF), ETC and dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1); monitor autophagy and mitophagy by interfering with mTORC1, ATG14L, Beclin1 and AMBRA1; and regulate several other related protein and enzymes (Fig. 2) [59].

Fig. (2).

. Preventive role of AMPK against various cytokines.

6. REGULATION AND ACTIVATION OF AMPK

In all eukaryotes, AMPK serves the essential function of conserving cellular energy levels and catalyzing several key elements and their production. Since the last couple of decades, the focus-on AMPK has been thoroughly implemented, as it is considered a new potential target for various diseases, including obesity, diabetes, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and diabetic nephropathy. Many investigations and advances have been made in the arena of AMPK structural biology, and they are beginning to provide detailed molecular understanding into the overall topology of these intriguing enzymes and how the binding of small components elicit subtle conformational changes leading to their opening and protection from dephos- phorylation. However, AMPK structure and function on specific molecular interactions are yet to be properly disclosed while applying direct natural or synthetic AMPK activators of enhancers [50, 87].

The processes of regulating mammalian AMPK exists as a heterotrimeric complex consisting of 3 subunits that transpire as multiple isoforms. The catalytic α-subunits (α1/ α2) and the structurally crucial β- subunits (β1/β2) and γ-subunits (γ1/γ2/γ3) are encoded by 7 different genes. The catalytic subunit preserves a highly conserved Ser/Thr kinase domain close to the N-terminus in the activation ring. These isoforms are encoded by diverse genes that are separately expressed and have exclusive tissue-specific expression outlines, creating the prospect of producing 12 distinct heterotrimer amalgamations. Phosphorylation of Thr-172 within this circle is critical for enzyme activity [88]. Phosphorylation of Thr-172 within this loop is critical for enzyme activity. In addition to regulation through phosphorylation, AMPK- subunit activity has been found to be self-regulated by a region identified as C-terminal to the kinase domain (Fig. 2) [89, 90]. This auto-inhibitory sequence (AIS) is similar to ubiquitin connected domains, which are mostly conserved sequences inside the AMPK sub-family of kinases. Investigations performed using AIS deletion constructs demonstrate a larger than 10-fold enlargement in kinase property as compared with constructs containing the AIS [91, 92]. The AMPK-subunits normally do not display catalytic activity, but they have emerged to be complex for AMPK α-β-γ complex assemblage and glycogen sensing in the cell [93]. Phosphorylation of AMPK α-subunit helps in the phosphorylation of MKP1, ULK1 and mTORC1 and regulates lipolysis, insulin resistance and Mitophagy [94]. Domains located close to the C-terminus of the -subunit have been revealed to interrelate with regions on the α- and γ-subunits, which recommends that the β-subunit, in part, may participate as a scaffold to sustain AMPK heterotrimeric complex assemblage. The β-subunits also restrain glycogen-binding domains (GBD) that arbitrate AMPK’s connection with glycogen and could assist the colocalization of AMPK with its component glycogen synthase (GS). This phenomenon may permit the cell to coordinate the maintenance of glycogen production with glycogen concentration and energy accessibility [95, 96]. In addition to these, a potential role for β-subunit myristoylation has been incorporated to be important for suitable AMPK cell membrane activation and localization [97]. Activation of β-subunit helps in the phosphorylation of MFF, which is responsible for mitochondrial fission [89]. The AMPK γ-subunits control enzyme activity by sensing comparative intracellular AMP, ADP and ATP concentrations. This is achieved by the complex interactions of adenine nucleotide with 4 frequent cystathionone-β-synthase (CBS) motifs occurring in pairs known as Bateman domains [98, 99]. Activation of γ-subunit helps in the phosphorylation of PGC1α, which further regulates mitochondrial biogenesis [89]. It is now hypothesized that the CBS motifs assemble in an approach that results in the formation of 4 adenine binding sites. In the binding sites, site 4 has a comparatively very high affinity for AMP and generally does not readily exchange for ADP or ATP, whereas sites 1 and 3 bind AMP, ADP, and ATP competitively [100]. Site 2 seems to be mostly unoccupied, and its role in maintaining AMPK action has not been properly elucidated [101, 102]. In the beginning, AMPK inauguration was believed to be mediated mainly by AMP binding; however, new research has shown that both ADP and AMP binding result in conformational changes that trigger AMPK in 2 ways: by promoting Thr-172 phosphorylation by upstream kinases; and by antagonizing its dephos- phorylation with protein phosphatase(s) [103, 104]. Conversely, only AMP has been demonstrated to, in a straight line, increase phosphorylated AMPK (Thr172) property via a mainly allosteric mechanism. Research on kinetic enzyme assays has shown that allosteric commencement by AMP results in a greater than 10-fold enhancement in activity, while the activation resulting from Thr-172 phosphorylation of the α-subunit is bigger than 100-fold. In combination, these 2 triggering mechanisms produce a greater than 1000-fold increase in activity [105].

Several AMPK kinases have been implicated in mediating AMPK Thr-172 phosphorylation in vitro; hence, only 2 have been reported to be physiologically appropriate in in vivo studies. The major AMPK kinase is the ubiquitously produced tumor suppressor liver kinase B1 (LKB1) [106, 107]. Even though LKB1 activity is not reliant on the phosphorylation of its activation ring, significant enhancement requires binding of the scaffold protein MO25 and stabilization by Ste20-mediated adaptor (STRAD) protein interaction [108]. Taken together, these 3 proteins form an inherently dynamic trimeric LKB1-STRAD-MO25 complex that has been shown to mediate-AMPK Thr-172 phosphorylation in different mammalian physiology. Since the discovery of LKB1 as an AMPK kinase, with the interaction of Ca2+ /calmodulin-dependent kinase (CaMKK), which phosphorylates Thr-172 in response to induced cytosolic Ca2+ levels autonomous of changes in adenine nucleotides [109]. It is hypothesized that this interaction may couple ATP-requiring developments, which is frequently activated through enhancement in cytosolic Ca2+, with AMPK-dependent restoration of energy change before a noteworthy reduction in ATP concentrations take place. The physiological significance of another important AMPK kinase, TAK1, continues to be established [110, 111].

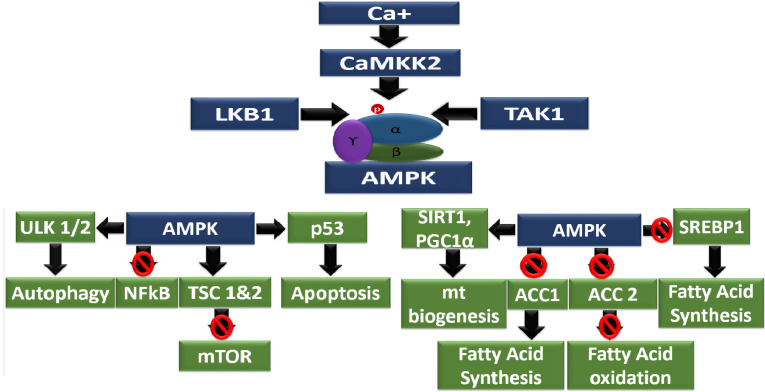

7. OXIDATIVE STRESS AND INFLAMMATION

The term oxidative stress is often described as oxidant-mediated cell damage, for example, by free radicals (reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen species). In the environment, several oxidants are present, including water containing arsenic, which is responsible for many life-threatening diseases like hepatic damage, kidney failure, heart dysfunctions and neurodegeneration [143]. Like environmental oxidants, fried or over-cooked food sometimes generates many oxidants like advanced glycation end products (AGEs) that may lead to diabetes and cardiovascular complications [26, 144]. On the other hand, cellular metabolism and reproduction sometimes produce unnecessary and unwanted byproducts that can act as oxidants and furthermore help in cellular necrosis and apoptosis. In addition, dying cells or cancer cells might secrete several oxidants which further interfere in many biochemical pathways, leading to the progression of pathophysiology [145, 146]. Free radicals are mostly generated during energy production in mitochondria. As the liver is the main source of mitochondrial generation, it suffers more from free radicals. In patients with Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH), the hepatic mitochondria exhibit ultrastructural lesions and reduced activity of the respiratory chain complexes [147]. This phenomenon decreases the activity of the respiratory chain, resulting in the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) that oxidize fat accumulations to form lipid peroxidation products, which in turn, cause necrosis, steatohepatitis, hepatitis, fibrosis and cirrhosis. Overproduction of mitochondrial ROS formation in cirrhotic and steatohepatitis could directly damage mitochondrial DNA and related respiratory chain polypeptides, trigger NF-κB activation and the hepatic synthesis of TNF-α and ILs (Fig. 3) [148]. Glomerulonephritis has also been connected in animal models when levels of free radicals, such as malondialdehyde, advanced oxidation protein products, thiobarbiturates, 15-f2t-isoprostane and hydrogen peroxide, are exceeded due to chemical treatment [149]. Similarly, Xanthine oxidase (XO), α-troponin, creatine kinase-MB, uric acid and hydroxyl ion have been correlated with myocarditis, vasculitis, cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis [6, 23]. Neurodegeneration and neurodermatitis have also been associated when free radical-mediated oxidative stress; this was induced in rats [150]. Natural oxidants such as arsenic and aflatoxins often induce oxidative stress and have been associated with skin inflammation [143]. Besides, having little or no antioxidants such as superoxide dismutase, catalase, α-tocopherol, β-carotene, ascorbate and glutathione in the body can lead to inflammation (Fig. 1) [20, 151].

Fig. (3).

Anti-inflammatory property of AMPK on inflammatory cytokines.

8. DIABETES AND INFLAMMATION

Both type-1 and type-2 diabetes mellitus are the leading causes of morbidity and mortality nowadays. Prevention of diabetes mellitus and its associated risk factors, mainly cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, have become major health concerns throughout the world. Along with obesity, the pathophysiology of so-called “diabesity”, that is, diabetes mellitus in the milieu of obesity has recently gained significant awareness [152]. The exact cause of diabetes is yet to be explored; however, the relationship between type-2 diabetes and inflammation is more complex than what has been reported so far by the animal and human studies. First, inflammation possibly underlies also the development of insulin resistance and not only of pancreas dysfunction but also responsible with adipose tissue, brain, liver and kidney that eventually resulting of obesity and a critical contributing factor to the development of metabolic disease [153, 154]. Other studies have also suggested that infection from cytomegalovirus (CMV) is also responsible for damaging the pancreas [26]. In addition, excess glucose accelerates the formation and production of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), interacting with its receptor named RAGE, which further generates reactive oxygen species and initiates inflammatory signaling cascades. Consequently, AGEs have significant roles in the pathogenesis of diabetic complications. It is reported that RAGE is also expressed on monocytes T-lymphocytes and macrophages, which complicates the phenomenon [155]. Similar theories have also been proposed by other investigations, where the authors showed that cytokines released by both activated macrophages and T-lymphocytes, especially interleukin-1 (IL-1), have been compromised as immunological effector molecules that both prevent insulin release from the pancreatic β-cell and accelerate β-cell destruction that can lead to hyperglycemia [156]. Moreover, nitric oxide (NO) produced by iNOS directly encourages the activities of both the inducible and constitutive isoforms of COX, further augmenting the overactivation of these pro-inflammatory markers, NO and prostaglandins, which may be necessary in maintaining or initiating the inflammatory signaling and knocking down the β cell related with autoimmune diabetes [157]. Furthermore, insulin resistance keeps the excess sugar in the blood, which signals diacylglycerol (DAG) that interacts with mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and Inositol triphosphate (IP3). This situation results in harmful immune cytokine transcription factors being transcribed in the nucleus, which worsens the diabetes and starts attracting other intact organs [158]. It has also been reported that during the progression of diabetes a number of biochemical pathways and mechanical factors come together in the endothelium, leading to endothelial damages, vascular inflammation and macrovascular diseases [159].

9. OBESITY AND INFLAMMATION

Obesity has been a sober concern as it is becoming an epidemic with its vast health consequences. Not only are physicians worried but nutritionists and physiotherapists are also facing difficulties managing the situation, especially in the Western world and urban areas. Molecules to treat obesity are very few in the market and pipeline. Medicinal chemists are also trying to discover newer components, as obesity contains several other complicated factors in its pathophysiology. Obesity is often conveyed by excess fat storage in tissues other than adipose tissues, including the skeletal muscle and liver, which may initiate to local insulin resistance and could trigger inflammation, as in steatohepatitis [160]. Similarly, in the vascular system, excess fat deposition may trigger vasculitis, which further accumulates foam cells, and the patient might ultimately end-up with atherosclerosis [7]. In addition, studies also found that patients with central obesity are at risk for chronic kidney disease such as obesity-related glomerulopathy, which may turn into end-stage renal diseases [161]. High-fat and high-sugar diet have also been associated with myocarditis and cardiac hypertrophy by AGE-RAGE interaction [162]. On the other hand, the immune system’s prime role is maintaining or regaining homeostasis upon external or internal threats. Inflammation is an evolutionary perpetuated danger control program that steers from host defense against stimuli as inflammation can prevent pathogens from entering and spreading at disrupted barriers [163]. Recent studies suggest that adipocytes are now considered as a gland since they secrete various factors such as vaspin, adiponectin, hepcidin, omentin, chemerin, visfatin, apelin and many inflammatory and pro-inflammatory cytokines. Following the discovery of tumor necrosis factor-α and leptin as soluble/secretory products of adipose tissues in the early 1990s, consequently, obesity research has focused on the new functional role of adipocytes, as an active endocrine gland/organ. Many more inflammatory peptides have been linked to adiposity, with obesity ultimately characterized as a state of low-grade metaflammation or systemic inflammation, which may connect obesity to its co-morbidities [164]. Obesity also aggravates several other phenomenons such as thrombosis, nephritis, atherosclerosis, stroke, diabetes, vasculitis, systemic hypertension, allergies, osteoarthritis, NAFLDs, alzheimer’s disease, insulin resistance, rheumatic carditis and fibrosis; therefore, controlling and managing obesity can play a pivotal role in preventing non-communicable diseases and other co-morbid situations [165].

10. INFLAMMATION AND CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASES

The human heart is the most important organ that pumps blood throughout the body passing through the circulatory system, supplying necessary oxygen and nutrients to the tissues and removing excess carbon dioxide and other waste materials. In spite of several advancements in medical science, cardiologists recommend that hepatic subjects visit hepatologists and vice versa as both the pathophysiologies interfere with each other [7, 166]. There are several factors that have been considered for cardiovascular diseases and one of them is cardiovascular inflammation, for example, mechanical stress, smoke exposure, hypercholesterolemia, hyperhomocysteinemia and chronic infection leading to atherothrombotic cardiovascular disease (CVD), coronary arterial disease (CAD), stroke, and peripheral arterial disease [7]. Among all the common risk factors, obesity is a highly prevalent condition and is heterogeneous, which has the highest impact on developing cardiovascular disease (CVD)s and related complications. Laboratory investigations and epidemiological reports have consistently demonstrated that the assembling of excess visceral fat is related to the huge risk of CVD as well as several metabolic and inflammatory perturbations. Since the beginning of the 2000’s, reports from multiple investigations have served to emphasize that arterial calcification and atherosclerosis have several correlations between inflammatory components and vascular dysfunctions that may serve as a vital element to discover pathophysiological processes and to unveil a new therapeutic approach [167]. Clinical evidence has also highlighted the finding that the expanded visceral fat is infiltrated by macrophages, which are then enhanced in the process of producing foam cells. These cells are responsible for conducting “cross-talk” with adipose tissue through numerous significant mechanisms [168]. In recent times, cytokines such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α soluble, as well as adhesion molecules, for example, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, have been considered with both risk factors and diseases and may serve as potential therapeutic targets for the nonspecific “anti-inflammatory” treatment of arterial disease [8, 169]. There have been a series of cases where heart failure subjects were diagnosed with extreme concentration of inflammatory markers [170]. On the other hand, Reg3β, a cardiac marker, has been responsible for the acute inflammatory response, often found higher in serum concentration in patients with acute coronary syndrome and also found connected in myocardial infarction [171]. Prior investigations suggested that the serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase (SGK1) play a key role in inflammation and cardiac remodeling. A different correlation has also been established between SGK1 and cardiac angiotensin, which often potentiates the damaging property of the heart [172]. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP)-4, on the other hand, known as a potent cardiac inflammatory marker has also been found in cardiac damage subjects [6]. Besides, xanthine oxidase (XO), α-troponins and creatine kinase-MB have also been blamed and reported in various heart research works as inflammatory cytokines [23].

11. INFLAMMATION AND HEPATIC DYSFUNCTIONS

Hepatic damages can be initiated with a viral infection, smoking, chronic alcoholism, substance abuse and poly-pharmacy, which can be worsened by diabetes, obesity, aging, chronic diseases and sedentary lifestyle. Inflammations are the pathogenic outcomes of various types of acute and chronic liver insults and stimulations, and these facilitate the progression of liver diseases like hepatitis, steatosis, cirrhosis and fibrosis [173, 174]. Components of the innate immune system instigate and maintain hepatic inflammation through mediator generation, resulting in the activation of their pathogen-derived products perceived by pattern recognition receptors on the cell surface [174]. Dendritic cells, which are part-innate immune cells, play a prime role in sensing pathogens and initiating adaptive immune responses by the activation and regulation of T-lymphocytes [175]. Unfortunately, liver inflammation is the most complicated phenomenon as no particular therapy is recommended other than taking a rest and eating healthy [176]. Both non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) are mediated through various inflammatory stimulations and have recently been epidemic, especially in Western countries, because they have very few effective drug treatments, as the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying their hepato-protective functions remain largely uncharacterized. Concurrently, owing to the presence of obesity, is quite difficult to achieve weight reduction or a reduction of central obesity or visceral fat with the treatment of NAFLD in the perspective of ‘gold standard’. Early diagnosis and management of the underlying condition remain the mainstay of treatment to avoid chronic inflammation [177, 178]. In many investigations of NAFLD, the risks of progressing metabolic and cardiovascular morbidities are much higher than the risks of developing hepatic disorders. In fact, NAFLD is connected as the liver manifestation of the metabolic syndrome, which passes on to a cluster of cardiovascular risk factors linked with insulin resistance, including visceral or central obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia and type-2 diabetes mellitus [179-181].

12. INFLAMMATION AND RENAL DAMAGES

In a human body, the kidneys play a major role in producing lifesaving hormones, regulating blood pressure, monitoring fluid and electrolyte balance and excreting body wastes [149]. Inflammation in the kidney is more common in females than males since males benefit from the advantages of the activity of testosterone [182, 183]. Hypertension, urinary infection, diabetes, proteinuria and renin-angiotensin system (RAS) have been primarily identified as risk factors for renal inflammation. Similarly, cardiovascular dysfunctions and hepatic damages also play a significant role in the progression and development of kidney inflammation. The involvement of reactive oxygen spices is equally responsible for the inflammatory pathways [6]. Apoptosis and inflammation are prime causes of organ damage in the course of renal injury. General aspects of renal inflammation can be unwanted apoptosis, kidney morphology, injury induction, and activity of the glomerulus function. Activated caspases, the typical effector enzymes of apoptosis, are able to initiate not only apoptosis but also inflammation after renal injury of ischemia-reperfusion in experimental models [184]. Along with the secretion of IL-1β, secretion of IL-18 and a programmed form of cell death, toll-like receptor (TLR)-driven danger signaling in kidney disease, evolving reports now suggest a similar involvement in various inflammasome in renal inflammation subjects [185]. Since the last two decades, basic science has brought up a new perceptive of how pathogens prompt inflammation, mainly by the discovery of RIG-like receptors, NOD-like receptors (NLRs), toll-like receptors (TLRs), and C-type lectin receptors (CLRs). Especially, the toll-like receptors (TLRs) have spurred interest in kidney inflammation outside infectious disease research. It was a groundbreaking discovery that is not only pathogen-associated but also demonstrates that sterile damage-asso- ciated molecular patterns (PAMPs and DAMPs) stimulate TLRs to signal pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that further trigger inflammation. The latest entry into this concept is the inflammasomes in renal inflammation, which increases research interest in the nephrologists [186, 187]. Inflammation in the kidney may reduce the activity of tubular secretion, fluid and electrolytes re-absorption, and waste elimination, causing the subject to be dependent on regular dialysis. Besides, inflammatory cells damage and reduce cell wall integrity, enhance endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, prevent mitochondrial biogenesis and interfere with the normal DNA duplication, which pushes the subject toward serious health issues [23, 149].

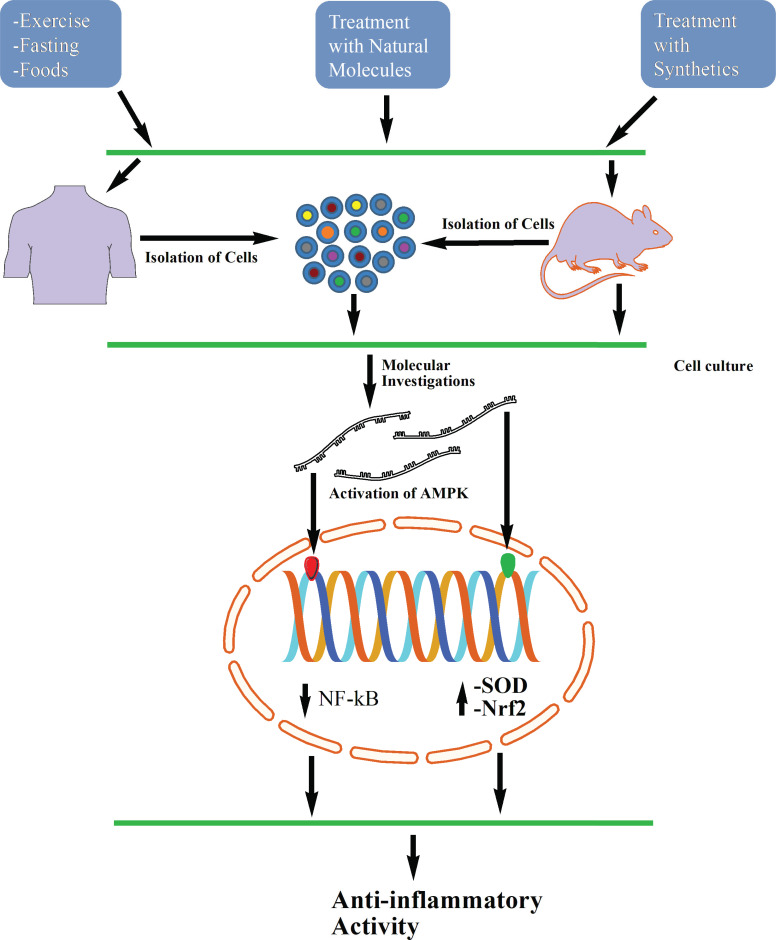

13. MOLECULAR MECHANISMS OF AMPK ON INFLAMMATION

The etiology of inflammation inside the body is a mystery and the exact mechanisms are yet to be explored. Besides, inflammatory pathways trigger many incidents of biochemical signaling; therefore, other treatment strategies may be less effective to achieve their proper goals. In addition, immunity will show differently with individual subjects as inflammatory responses vary from each other. Moreover, no one can predict how the body will react with foods, weather, medications and foreign invaders [169, 181]. Both the naturally derived and synthetic components (Fig. 4) have been proven effective by activating AMPK to minimize inflammation in both animals and cell cultures (Tables 1 and 2).

Fig. (4).

Proposed hypothetical figure where AMPK can participate to inhibit various diseases.

14. EFFECT OF AMPK ON VARIOUS KINASES

AMPK shows a potential capacity to reduce the inflammatory stages but direct preventive mechanisms are yet to be seen. However, recent investigations show several anti-inflammatory activities of AMPK in in-vitro and in-vivo models where researchers found that pharmacological activation of AMPK instantly inhibited the Janus kinase (JAK)-signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway in various cells, including in cultured vascular endothelial cells and fibroblasts. Relatively very few studies have investigated how the JAK-STAT pathway is controlled by AMPK and exerts anti-inflammatory property as this is a predominantly important concern to address given the pathophysiological roles of enhanced JAK-STAT signaling in multiple chronic inflammatory circumstances, for instance, hepatitis, nephritis, atherosclerosis, colitis and rheumatoid arthritis, as well as various cancers and hematological disorders driven by mutational activation of JAK isoforms. In vitro kinase assays showed that AMPK directly phosphorylated 2 residues (Ser515 and Ser518) within the Src homology 2 domain of JAK1, and activation of AMPK enhanced the interaction between JAK1 and 14-3-3 proteins; therefore, suppression of inflammatory signaling may be achieved [188]. Furthermore, activation of macrophages and increased cytokine infiltration have been experimented in adipose tissue from wild-type mice transplanted with bone marrow from AMPKβ1-/- mice, and taken as a whole, it has been proven clearly that AMPK can limit inflammatory cell infiltration and activation in multiple settings (Table 3) [189].

Table 3.

Role of AMPK enhancers/inducers on inflammation and related disorders.

| AMPK Enhancers | Experimental Design | Applications/Outcomes of the Experiment | References |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Name of the Component: Xanthohumol Dose: 10 or 50 mg/kg |

Model: Wild-type (WT) and Nrf2−/− (knockout) C57BL/6 mice | -Induction of AMPK reduced ROS and cytokine secretion. -Txnip/NLRP3 inflammasome and NF-κB signaling pathways were also found to be inhibited. |

[206] |

|

Name of the Component: Metformin Dose: 200 mg/kg |

Model: Six months older male Wister rats | -The treatment reduced cellular levels of nuclear factor-κB, Tumor Necrosis Factor-α and Cyclooxygenase-2 through AMPK pathway. | [203] |

|

Name of the Component: AICAR Dose: 11 pM |

Model: Endothelial cells | -Induction of AMPK demonstrated an anti-inflammatory pathway linking with PARP-1, and Bcl-6 pathways. | [16] |

|

Name of the Component: Retinoic acid Dose: 10 µM |

Model: BALB/c mice | -The treatment inhibited tissue factor and HMGB1 via modulation of AMPK activity in TNF-α activated endothelial cells and LPS-injected mice. | [194] |

|

Name of the Component: Cilostazol Dose: 0.1% Cilostazol with chow food |

Model: Sprague Dawley rats |

-Induction of AMPK inhibited NF-κB activation, as well as the induction of iNOS mRNA and protein expression, within the aortas of LPS-treated rats. | [227] |

|

Name of the Component: 2,3,4’,5-tetrahydroxystilbene-2-O-β-d-glucoside (THSG) Dose: 10, 20, 40, 80, and 100 µM |

Model: Mouse primary microglia and cell culture | -LPS-induced NF-κB activation and neuro-inflammatory response (TNF-α, IL-6, and PGE2) activating AMPK/Nrf2 pathways. | [215] |

| Name of the Component: Ginseng Saponin Metabolite Rh3 | Model: N/A | -Rh3 exerts an anti-inflammatory effect in microglia by modulating AMPK and its downstream signaling pathways such as phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt and JAK1/STAT1. | [228] |

|

Name of the Component: Quercetin, Luteolin and EGCG Dose: 10 µmol/l each |

Model: EA.hy-926 cells | -The treatment inhibited ER stress-associated TXNIP and NLRP3 inflammasome activation, and therefore protected endothelial cells from inflammation and apoptosis. | [207] |

|

Name of the Component: Luteolin Dose: 100 µM |

Model: HepG2 hepatocarcinoma cells | -AMPK activity was found to be critical for the inhibition of intracellular ROS in turn mediate NF-κB signaling. | [216] |

|

Name of the Component: Methotrexate and A769662 Dose: N/A |

Model: Human monocytes and bone marrow-derived macrophages | -Methotrexate-induced AMPK activation was associated with a reduction in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1 β, and TNF-α) in response to LPS and TNF stimulation. | [198] |

|

Name of the Component: Metformin Dose: 5 µM |

Model: Wild type C57/Bl6 mice | -Metformin specifically inhibited LPS-induced IL-1β production and boosts IL-10 induction via AMKPα1- and or AMPKβ1 pathways. | [199] |

|

Name of the Component: LY294002 and or CP-690550 Dose: 20 µM |

Model: C57BL/6J mice | - AMPKα1 is required for IL-10 activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTORC1 and STAT3-mediated anti-inflammatory pathways. | [200] |

|

Name of the Component: Lindenenyl acetate Dose: 20 µM |

Model: The immortalized HPDL cell line | -Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) derived nitric oxide (NO) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) derived prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) production were found to be downregulated with the association with AMPK induction. | [202] |

|

Name of the Component: Emodin Dose: 0-80 µM |

Model: Mouse primary microglia and cell culture | -The approach effectively inhibited the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, TNF-α and IL-6, and reduced the level of IκBα phosphorylation with the involvement of AMPK/Nrf2 Activation. | [229] |

|

Name of the Component: Monascin and Ankaflavin Dose: 10 µM |

Model: Mouse liver cell FL83B | -AMPK suppressed the production of inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, TNF-α, and TGF-β. | [195] |

|

Name of the Component: Flufenamic Acid Dose: 50 µM |

Model: NRK-52E cells | -The strategy significantly suppressed nuclear factor- activity and inducible nitric-oxide synthase expression triggered by interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor- α. | [230] |

|

Name of the Component: Xanthohumol Dose: 5 µM |

Model: CHO-ARE-LUC cells | -Inhibition of GSK3β or mTOR is not involved in the observed AMPK boost, and -AMPK also enhanced the activity of the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway. | [209] |

|

Name of the Component: Genetically induced or Ghrelin Dose: 100 nM |

Model: GHS-R knockout mice | -Ghrelin induction activated AMPK in primary endothelial cells showed potential activity in atherosclerosis by reducing inflammatory and proinflammatory cytokines. | [226] |

|

Name of the Component:AMP mimetic ZMP Dose: 100 µM |

Model: Vascular endothelial cells | -AMPK-mediated JAK-STAT signaling inhibition suppressed either by the IL-6Rα or in IL-6. | [231] |

|

Name of the Component: Berberine and SB203580 Dose: 10 µM and 10 µM |

Model: Sprague-Dawley rats | -The therapy reduced cleaved caspase 3, iNOS, Collagen-II, chondrocyte apoptosis and ameliorated cartilage degeneration via activating AMPK signaling and suppressing p38 MAPK activity. | [204] |

|

Name of the Component: trans-caryophyllene (TC) Dose: 50 µM |

Model: Rat cortical neurons/glia | -TC reduced cerebral ischemic injury via activation of the AMPK-CREB pathway. | [232] |

|

Name of the Component: Mangiferin Dose: 0.1, 1, 10 μmol/L |

Model: EA.hy926 cells | -The treatment ameliorated endothelial dysfunction by inhibition of ER stress-associated TXNIP/NLRP3 inflammasome activation and increased IL-1β secretion. in the endothelial cells | [208] |

|

Name of the Component: Wogonin Dose: 10–100 μM |

Model: Human glioma cell lines |

-The strategy blocked cell cycle progression at the G1 phase and induced apoptosis by inducing p53 expression and further upregulating p21 expression. | [233] |

|

Name of the Component: Ilexgenin A Dose: 80 mg/kg |

Model: Sprague-Dawley rats and ICR male mice | -The treatment prevented NLRP3 inflammasome activation by down-regulation of NLRP3 and cleaved caspase-1 induction, and -reduced IL-1β secretion was also noticed associate with AMPK activation. |

[234] |

|

Name of the Component: CRPE55IB Dose: 40 µM |

Model: Isolated primary microglia cultures | -CRPE55IB inhibited LPS-induced NF-κB activation and neuro-inflammatory response in microglia upregulating AMPK/Nrf2 pathways. | [210] |

|

Name of the Component: Resveratrol Dose: 0.1 or 10 µM |

Model: RAW 264.7 macrophage cells | -Enhancement of AMPK suppressed LPS-induced NF-κB-dependent COX-2 activation in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells. | [12] |

|

Name of the Component: RSVA314 and RSVA405 Dose: 3 μM each |

Model:C57BL/6 females cell cultures | -Enhancers of AMPK potently inhibited mTOR signaling, activated autophagy, and triggered Aβ clearance by the lysosomal system. | [235] |

|

Name of the Component: Ursolic Acid Dose: 2.5 mM to 10 mM dose-dependently |

Model:3T3-L1 pre-adipocytes | -Ursolic Acid inhibited CEBPα and β-actin in the fat cells via LKB1/AMPK pathways. | [51] |

|

Name of the Component: Nitric oxide (NO) Dose: 100 mmol/L |

Model: Human endothelial cells | - An inhibition of the IKK kinase and decreased NF-κB activation and TNF-α expression were observed with AMPKα2 phosphorylation. | [236] |

15. EFFECT OF AMPK ON TUMOR NECROSIS FACTORS

One of the major inflammatory cytokines is tumor necrosis factor (TNF), which has been associated with many disease conditions like hepatitis that leads to changes in the normal liver architecture, which could lead to liver failure [190]. TNF-α is also responsible for excess bleeding in the kidney, hampers homeostasis, leading to anemia, and finally, triggers renal failure [190, 191]. The presence of TNF-α is often evaluated in heart failure subjects as well [192]. This protein is found highly responsible for pancreatic β-cell damage, which ultimately triggers insulin resistance and type-I diabetes mellitus [193]. Taken together, inhibiting TNF from releasing macrophages can be a very effective approach to minimizing several diseases. To investigate the role of TNF-α on an endothelial cell (EC), mice were performed on LPS-injected subjects, and Retinoic acid (0, 0.01, 0.1, 1 and 10 mM) was applied on EC. It was observed that the introduction of Retinoic acid reduced cellular damages by activating the AMPK pathway [194]. Another investigation noticed that providing high-fat diet C57BL/6 to mice may lead to an inflammatory marker such as TNF-α, which ultimately causes nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. When AMPK enhancers, i.e. Monascin and Ankaflavin were given to mice, AMPK inducers promoted AMPK phosphorylation and inhibited the steatosis-related mRNA expression and inflammatory cytokines secretion like tumor necrosis factor-α and, thereby, improved nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (Table 3) [195].

16. EFFECT OF AMPK ON INTERLEUKINS

Interleukins (ILs) not only play a role in hereditary auto-inflammatory diseases but also strongly participate in atherosclerosis, chronic kidney disease and advanced metastatic colorectal cancer. The IL family consists of 11 different cytokines and 10 receptors although these are alienated into three subfamilies. The major sources of IL are macrophages, β-cells, monocytes, dendritic cells, Th2 cells, just activated naive CD4+ cell, memory CD4+ cells, mast cells and many more which generally bind with CD121α/IL1R1, CD121β/IL1R2, CD25/IL2RA, CD122/IL2RB, CD132/IL2RG, CD126/IL6RA, CD130/IR6RB and many others that mainly target activated T cells, NK cells, macrophages, oligodendrocytes, hematopoietic stem cells, T helper cells and β-cells to trigger their responsible cascade systems. It is also established that blocking IL and TNF can be a very good solution to controlling and minimizing inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, of course, with some exceptions such as gout and uric acid and Xanthine oxidase-mediated phenomenon [196, 197]. Human monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM) and mou- se bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) along with AICAR and A769662 were investigated to observe the role of inflammation and AMPK interactions and it was noticed that both AMPK-enhancers were able to reduce IL-6 and IL-1 β levels in response to LPS and TNF stimulation; thereby, the authors strongly suggested that these agents can be a good target for the development of new anti-inflammatory drugs [198]. Another study showed that Metformin prevented the production of ROS from NADH: Ubiquinone oxidoreductase to limit induction of IL-1β in LPS-activated macrophages. The study further proved that Metformin was able to boost IL-10 to enhance anti-inflam- matory activity since the activation of AMPK in the cell culture of wild-type C57/Bl6 mice; thereby, this molecule can be a good target for reducing diabetes-associated inflammations [199]. AMPK is a conserved serine/threonine kinase with a decisive function in playing an additional role as a regulator of inflammatory activity, especially in leukocytes. IL-10-induced gene expression and the anti-inflammatory function of AMPK phosphorylated both Tyr705 and Ser727 residues of STAT3 in an AMPKα1-dependent manner, and this phosphorylation signaling was blocked by the reticence of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase β, an upstream enhancer of AMPK, and by the mTORC1 blocker rapamycin, respectively. The impaired STAT3 phosphorylation in response to IL-10 observed in AMPKα1-deficient macrophages was accompanied by a decreased suppressor of inflammatory signaling 3 expression and the insufficiency of IL-10 to suppress LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine production (Table 3) [200].

17. EFFECT OF AMPK ON CYCLOOXYGENASES FAMILY MEMBERS

Eicosanoids and endocannabinoids, the metabolites of arachidonic acid, have miscellaneous functions in the regulation of immunity and inflammation. Arachidonic acid (AA) is one of the major polyunsaturated ω-6 fatty acids. AA is metabolized by three groups of oxygenases, namely lipoxygenases (LOX), cyclooxygenases (COX), and cytochrome P450s (CYP) to a number of biologically active eicosanoids, which lead to the productions of several inflammatory mRNA, including iNOS, leukotrienes, COX-1, COX-2, COX-3 and many more, which are responsible for several inflammatory diseases [201]. Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) derived nitric oxide (NO) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) often play a major role in initiating inflammatory cascade by the activation of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) production, which is often connected with several diseases; therefore, blocking this pathway may be effective in preventing inflammation. When Lindenenyl acetate was given in the immortalized HPDL cell line, it blocked LPS-induced inflammatory NO, PGE2, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-12 production via heme oxygenase-1 and AMPK-dependent pathways [202]. A study has shown that when Metformin (200 mg/kg) was applied to ischemia subjects, it diminished inflammatory cascade by reducing COX-2/β-actin signaling through the induction of AMPK-independent activation [203]. Osteoarthritis subjects often suffer more as the pathophysiology is really complex and the treatment approach is really difficult. When Berberine was applied on nitric oxide-induced rat chondrocyte, it down-regulated expressions of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), Type II collagen (Col II) at protein levels and caspase-3, which were accompanied by improved adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) phosphorylation and reduced phosphorylation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) (Table 3) [204].

18. EFFECT OF AMPK ON INFLAMMASOME

The inflammasome is a complex of proteins paradox that through the activity of caspase-1 and the downstream substrates gasdermin D, IL-18 and IL-1β execute an inflammatory form of cell death termed pyroptosis. Activation of this complex phenomenon sometimes involves the adaptation (Inflammasome Adaptor Protein Apoptosis-Associated Speck-Like Protein Containing CARD) and up-regulation of sensors, including NLRP3, NLRC4, NLRP1, AIM2, and pyrin, which are triggered by different stimulating factors such as infectious agents, xenobiotics and changes in cell homeostasis [205]. Cytokine secretion and the inhibition of inflammasomes can play a major role in preventing inflammatory cascades. Xanthohumol inhibited lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced acute lung injury by preventing the reduction of Txnip/NLRP3 inflammasome by up-regulating AMPK/GSK3β-Nrf2 signal axis [206]. Another experiment evaluated that quercetin, luteolin and epigallocatechin gallate (10mmol/L each) were found to be anti-inflammatory when applied on endothelial cells. These molecules reduced TXNIP and NLRP3-mediated inflammation and apoptosis with the regulation of AMPK [207]. Endoplasmic reticulum stress has been associated with various inflammatory markers, which further initiate apoptosis in normal cells; therefore, unwanted and immature cell death occurred. To prevent the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and associated inflammation, endothelial cells were treated with high glucose (25 mmol/L) exposure, which resulted in higher levels of IL-1β and IL-6 production, which ultimately triggered TXNIP and NLRP3-mediated inflammasome. However, when Mangiferin (0.1, 1, 10 μmol/L) was applied on EA.hy926 cells, it prevented TXNIP and NLRP3 inflammasome activation via regulation of AMPK (Table 3) [208].

19. EFFECT OF AMPK ON OXIDATIVE STRESS

Free radicals, including reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen species, sometimes interact with the cell membrane, cell cytoplasm, mitochondria and genetic codes, leading to cell damage where local inflammatory cells are attracted and invited, which aggravates the situation. Antioxidant genes, on the contrary, play a vital role in protecting the cellular components and help in cell survival; therefore, these genes can fight against inflammatory cytokines either directly or indirectly. Induction of heme oxygenase, superoxide desmutase, catalase, Nrf-2 and glutathione can be a very innovative approach to preventing inflammatory diseases. A study suggested that Xanthohumol leads to AMPK activation via transcription of HO-1 mRNA in an LKB1-dependent manner and thus observed subsequent AMPK-mediated enhancement of the Nrf2/HO-1 response in MEF and CHO-ARE-Luc were cultured cells [209]. [209]. When a novel compound from Polygonum multiflorum (CRPE55IB) was applied in the culture of primary microglia of mice, it was found that CRPE55IB activated Nrf2-mediated anti-neuroinflammation and also influenced AMPK pathway in microglia (Table 3) [210].

20. EFFECT OF AMPK ON NUCLEAR FACTOR- κB