Abstract

National data on patient characteristics, treatment, and outcomes of critically ill coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) solid organ transplant (SOT) patients are limited. We analyzed data from a multicenter cohort study of adults with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 admitted to intensive care units (ICUs) at 68 hospitals across the United States from March 4 to May 8, 2020. From 4153 patients, we created a propensity score matched cohort of 386 patients, including 98 SOT patients and 288 non-SOT patients. We used a binomial generalized linear model (log-binomial model) to examine the association of SOT status with death and other clinical outcomes. Among the 386 patients, the median age was 60 years, 72% were male, and 41% were black. Death within 28 days of ICU admission was similar in SOT and non-SOT patients (40% and 43%, respectively; relative risk [RR] 0.92; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.70-1.22). Other outcomes and requirement for organ support including receipt of mechanical ventilation, development of acute respiratory distress syndrome, and receipt of vasopressors were also similar between groups. There was a trend toward higher risk of acute kidney injury requiring renal replacement therapy in SOT vs. non-SOT patients (37% vs. 27%; RR [95% CI]: 1.34 [0.97-1.85]). Death and organ support requirement were similar between SOT and non-SOT critically ill patients with COVID-19.

KEYWORDS: clinical research/practice, complication: infectious, infection and infectious agents - viral, infectious disease, kidney transplantation/nephrology, organ transplantation in general, patient survival

Abbreviations: ACE2, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; AKI, acute kidney injury; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CI, confidence interval; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; ICU, intensive care units; IQR, interquartile range; OR, odds ratio; PS, propensity score; RECOVERY, Randomised Evaluation of COVid-19 thERapY; RRT, renal replacement therapy; SOT, solid organ transplant; STOP-COVID, Study of the Treatment and Outcomes in critically ill Patients with COVID-19

1. INTRODUCTION

Since December 2019, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has spread from Wuhan, China to the rest of the world, leading to more than 20 million confirmed cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) with more than 738,000 deaths as of August 11th, 2020.1 The spectrum of clinical disease from COVID-19 varies from a mild febrile illness to critical illness, including acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and multiorgan failure, which are associated with high morbidity and mortality. Identified risk factors for adverse outcomes from COVID-19 include older age, obesity, male sex, and comorbid conditions, including diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic lung disease, and malignancy.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

Solid organ transplant (SOT) patients are considered high risk for complications from COVID-19 because of their immunosuppressed status.8 , 9 They are more susceptible to infections with ribonucleic acid respiratory viruses in general and have a higher risk of complications such as bacterial and fungal superinfection.10 However, because the manifestations of severe COVID-19, including ARDS and organ dysfunction, may be propagated by a proinflammatory state due to cytokine release syndrome,11 , 12 immunosuppressive therapy could potentially mitigate some of these effects and thereby help prevent severe complications in SOT patients.

Current data on the clinical course of COVID-19 in immunocompromised patients are limited predominantly to case reports and single-center studies. Among hospitalized SOT patients with COVID-19 in New York City, acute mortality rates varied between 13%-29%.8 , 13, 14, 15 A similar case fatality rate of 20%-28% was reported in hospitalized SOT recipient cohorts from Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands.9 , 16, 17, 18 A cohort study from Switzerland that included 20 hospitalized SOT patients reported a lower mortality rate of 10%, which was similar to the mortality observed in the general population with COVID-19.19 Small case series from the United States have also reported similar mortality rates in SOT patients with COVID-19 that have been observed in the general population.20, 21, 22, 23 In addition, there is no data available for outcomes of COVID-19 infected SOT patients admitted in intensive care units. Our paper is aimed to address this knowledge gap.

Previously published studies focusing on SOT patients and COVID-19 lack comparison with a control group to ascertain their risk as compared to the general population.8 , 9 , 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 To address this knowledge gap, we compared outcomes in SOT versus non-SOT patients with COVID-19 who were admitted to intensive care units (ICUs) throughout the United States, using data from a multicenter cohort study. We hypothesized that SOT patients would have similar risk of death and organ support requirement compared to non-SOT patients.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study design and oversight

We used data from the Study of the Treatment and Outcomes in critically ill Patients with COVID-19 (STOP-COVID). STOP-COVID is a multicenter cohort study that enrolled adults with COVID-19 admitted to participating ICUs at 68 hospitals across the United States. The study was approved by the institutional review board at each participating site with a waiver of informed consent and registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04343898).

2.2. Study sites and patient population

We included consecutive adult patients (≥18 years old) with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 (detected by nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swab) admitted to a participating ICU for illness related to COVID-19 between March 4 and May 8, 2020. We followed patients until the first of hospital discharge, death, or June 5, 2020 – the date on which the database for the current analysis was locked. A complete list of participating sites is shown in Table S1.

2.3. DATA collection

We collected detailed information about demographics, coexisting conditions, home medications (including immunosuppressive medications), symptoms prior to ICU admission, vital signs on ICU admission, and longitudinal data on laboratory values, physiologic parameters, medications, treatments, and organ support in the first 14 days following ICU admission. Definitions of baseline characteristics, comorbidities, treatments, and outcomes are shown in Table S2. A detailed description of the data collection and validation process has been previously published.24

2.4. Exposure variable

The primary exposure was SOT at baseline.

2.5. Clinical outcomes assessment

The primary outcome was death within 28 days of ICU admission. We also assessed the following secondary outcomes: ICU length of stay, defined as the time between ICU admission until death, discharge from the ICU, or end of follow-up (if still in the ICU at the end of follow-up); receipt and duration of invasive mechanical ventilation; receipt and duration of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO, including veno-venous ECMO, veno-arterial ECMO and veno-arterio-venous ECMO); acute kidney injury (AKI) requiring renal replacement therapy (RRT) and the number of days of RRT; ARDS, ascertained by manual chart review; secondary infection, defined as a suspected or confirmed new infection other than COVID-19 that developed after admission to the ICU based on microbiology cultures or strong clinical suspicion; thromboembolic event, including deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, stroke, or other thromboembolic event; receipt of vasopressors and the number of days on vasopressor therapy.

2.6. Statistical analysis

We summarized baseline patient characteristics according to SOT status and presented them as count and percentage for categorical variables and median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables.

We used a propensity score to account for differences in clinical and demographic characteristics of SOT and non-SOT patients. We identified variables associated with SOT status using logistic regression and used them to calculate propensity scores. We used STATA’s “psmatch2” command suite to generate the propensity score-matched cohort by 1-to-4 nearest neighbor matching with replacement. The following variables were included in the logistic regression model to create the propensity score: age; gender; race; ethnicity; body mass index; comorbidities – diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary artery disease (includes any history of angina, myocardial infarction, or coronary artery bypass graft surgery), congestive heart failure (includes both heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction), atrial fibrillation/flutter, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, other lung disease, chronic kidney disease (defined as a baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR]< 60 mL/min/1.73m2 on at least 2 consecutive occasions at least 12 weeks apart prior to hospital admission or per medical history), chronic liver disease (includes cirrhosis, alcohol related liver disease, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, autoimmune hepatitis, hepatitis B or hepatitis C, primary biliary cirrhosis), active malignancy (defined as any malignancy, other than nonmelanoma skin cancer, treated in the prior year), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), smoking status (nonsmoker/current/former smoker/unknown); and medication use prior to hospital admission (renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, β-blockers, statins, aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs). Differences in patient characteristics between groups were assessed using standardized differences before and after propensity score matching. Figure S1 shows the distribution of the propensity score in the 2 groups pre- and postmatching. The associations between SOT status and clinical outcomes were assessed using binomial generalized linear models (log-binomial model) with reporting of relative risks.

Differences in other variables, such as symptoms prior to ICU admission, receipt of immunosuppressive medications, vital signs, laboratory results, and receipt of invasive mechanical ventilation on ICU admission, as well as treatments and outcomes, were assessed by Student’s t test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and chi-square-test (or Fisher’s exact test) for categorical variables.

We conducted several sensitivity analyses to evaluate the robustness of our main findings. We separately analyzed kidney transplant recipients and their controls in the propensity matched cohort. In addition, we repeated all analyses in the entire cohort. In these analyses, we performed log-binomial unadjusted and multivariable regression, where we adjusted for the same variables included in the calculation of the propensity score. Moreover, we repeated all analyses after creating a different propensity score-matched cohort by 1-to-1 nearest neighbor matching without replacement.

A total of 5% of the data were missing. We did not impute missing values because of the relatively low proportion of missingness. Reported P values are 2 sided and reported as significant at <.05 for all analyses. All analyses were conducted using STATA/MP Version 13.1 (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Tennessee Health Science Center (20-07289-XP).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Baseline characteristics

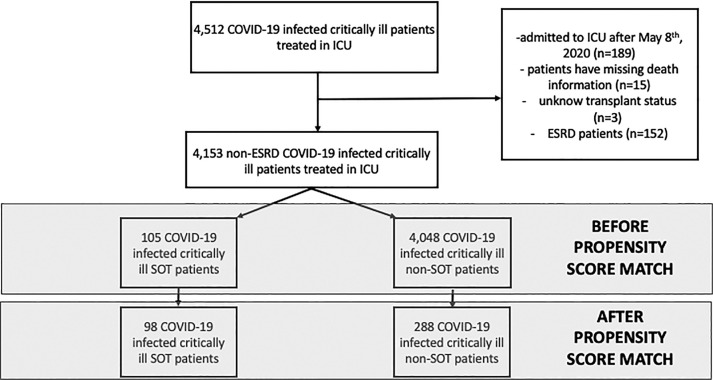

A total of 4512 critically ill patients with COVID-19 were identified as the source population. The flow chart for the cohort is shown in Figure 1. We excluded patients who were admitted to ICUs after May 8, 2020, to allow 28 days follow-up (n = 189). We also excluded patients missing data on death (n = 15) or SOT status (n = 3) and patients with end-stage renal disease (n = 152), which resulted in a study population of 4153 patients, including 105 SOT patients. Our propensity score-matched cohort included 386 patients (98 SOT and 288 non-SOT patients). The distribution of the 98 SOT patients included 67 kidney, 13 liver, 13 heart, 4 lung, and 1 pancreas transplant recipient. Among the 67 kidney transplant patients, there was 1 combined kidney/liver, 4 combined kidney/heart, and 3 combined kidney/pancreas transplant patients.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of patient selection. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; SOT, solid organ transplantation; ICU, intensive care unit; ESRD, end-stage renal disease

In the overall cohort of 4153 patients (before applying the propensity matching), the median age was 62 years (IQR, 52-71 years), 64% were male, and 30% were black (Table S3). The SOT patients were younger are were more likely to be male, black, and to have diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and chronic liver disease. SOT patients were also more likely to be receiving a beta blocker, statin, or aspirin prior to hospital admission as compared to non-SOT patients (Table S3).

In the propensity score matched cohort, SOT and non-SOT patients had similar baseline characteristics ( Table 1). The median age was 60 years, 72% were male, and 41% were black (Table 1). The SOT and non-SOT groups were well-balanced, as evidenced by the small standardized differences between groups (Table 1). Immunosuppressive medications were present almost exclusively in SOT patients prior to admission (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of solid organ transplant and nontransplant patients after propensity score matching

| Postmatch | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Cohort (n = 386) | Non-SOT patients (n = 288) | SOT patients (n = 98) | St Diff |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years) median (IQR) | 60 (51-70) | 61 (51-70) | 58 (52-69) | −0.004 |

| Sex (male) – no. (%) | 277 (72) | 205 (71) | 72 (73) | −0.051 |

| Race – no. (%) | 0.078 | |||

| White | 128 (33) | 99 (34) | 29 (30) | |

| Black | 159 (41) | 116 (40) | 43 (44) | |

| Asian/other | 99 (26) | 73 (25) | 26 (27) | |

| Ethnicity – no. (%) | 0.036 | |||

| Hispanic | 68 (18) | 48 (17) | 20 (20) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 287 (74) | 221 (77) | 66 (67) | |

| Unknown | 31 (8) | 19 (7) | 12 (12) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), mediana (IQR) | 29 (25-33) | 29 (26-34) | 29 (25-33) | −0.103 |

| Coexisting conditions – no. (%) | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 253 (66) | 189 (66) | 64 (65) | −0.007 |

| Hypertension | 317 (82) | 235 (82) | 82 (84) | 0.055 |

| Coronary artery disease | 104 (27) | 78 (27) | 26 (27) | −0.012 |

| Congestive heart failure | 71 (18) | 51 (18) | 20 (20) | 0.069 |

| Atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter | 48 (12) | 35 (12) | 13 (13) | 0.033 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 21 (5) | 15 (5) | 6 (6) | 0.039 |

| Asthma | 23 (6) | 17 (6) | 6 (6) | 0.009 |

| Other pulmonary disease | 50 (13) | 37 (13) | 13 (13) | 0.012 |

| Smoking statusb | −0.029 | |||

| Nonsmoker | 240 (62) | 180 (63) | 60 (61) | |

| Former smoker | 109 (28) | 78 (27) | 31 (32) | |

| Current smoker | 8 (2) | 8 (3) | 0 (0) | |

| Unknown | 29 (8) | 22 (8) | 7 (7) | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 198 (51) | 143 (50) | 55 (56) | 0.129 |

| Chronic liver disease | 35 (9) | 23 (8) | 12 (12) | 0.141 |

| HIV/AIDS | 10 (3) | 7 (2) | 3 (3) | 0.038 |

| Active malignancy | 25 (6) | 18 (6) | 7 (7) | 0.036 |

| Home medications – no. (%) | ||||

| ACE-I | 75 (19) | 59 (20) | 16 (16) | −0.107 |

| ARB | 80 (21) | 59 (20) | 21 (21) | 0.023 |

| Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist | 9 (2) | 7 (2) | 2 (2) | −0.026 |

| Beta blocker | 223 (58) | 162 (56) | 61 (62) | 0.122 |

| Statin | 229 (59) | 171 (59) | 58 (59) | −0.004 |

| NSAID | 2 (1) | 1 (0) | 1 (1) | 0.081 |

| Aspirin | 186 (48) | 138 (48) | 48 (49) | 0.021 |

Abbreviations: ACE-I, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; HIV/AIDS, human immunodeficiency virus infection/acquired immune deficiency syndrome; IQR, interquartile range; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; SOT, solid organ transplant; St Diff: standardized differences.

3.2. Symptoms prior to admission and clinical characteristics on the day of ICU admission

Table 2 shows symptoms, vital signs, laboratory values, and data on receipt of invasive mechanical ventilation on ICU admission. SOT patients experienced nasal congestion and diarrhea more frequently as symptoms of COVID-19 infection, and had longer time elapsed between the start of symptoms and ICU admission, than non-SOT patients; other symptoms were similar between the groups. SOT patients had lower temperature, higher systolic blood pressure, lower white blood cell count, lower absolute lymphocyte count, and higher serum ferritin compared to non-SOT patients in the propensity score matched cohort. Interestingly, the C-reactive protein was similar between the 2 groups (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Clinical characteristics on the day of ICU admission in solid organ transplant patients and nontransplant patients in the propensity score matched cohort

| Clinical characteristics | Cohort (N = 386) | Non-SOT (N = 288) | SOT (N = 98) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms prior to ICU admission – no. (%) | ||||

| Cough | 269 (70) | 196 (68) | 73 (74) | .23 |

| Sputum production | 46 (12) | 32 (11) | 14 (14) | .40 |

| Hemoptysis | 7 (2) | 6 (2) | 1 (1) | .50 |

| Sore throat | 35 (9) | 27 (9) | 8 (8) | .72 |

| Nasal congestion | 31 (8) | 18 (6) | 13 (13) | .03 |

| Headache | 33 (9) | 24 (8) | 9 (9) | .80 |

| Fever | 236 (61) | 177 (61) | 59 (60) | .83 |

| Chills | 83 (22) | 60 (21) | 23 (23) | .58 |

| Dyspnea | 272 (70) | 198 (69) | 74 (76) | .21 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 76 (20) | 59 (20) | 17 (17) | .50 |

| Diarrhea | 92 (24) | 58 (20) | 34 (35) | <.01 |

| Myalgia or arthralgia | 97 (25) | 70 (24) | 27 (28) | .52 |

| Confusion or altered mental status | 46 (12) | 35 (12) | 11 (11) | .81 |

| Fatigue or malaise | 143 (37) | 111 (39) | 32 (33) | .30 |

| Days from symptom onset to ICU admission median (IQR)a | 7 (4-10) | 7 (4-10) | 7 (6-11) | <.01 |

| Days from symptom onset to hospital admission median (IQR)b | 5 (3-8) | 5 (3-7) | 6 (3-8) | .04 |

| Immunosuppressive medications 30 days prior to ICU admission – no. (%) | ||||

| Corticosteroidsc | 29 (8) | 14 (5) | 15 (15) | <.01 |

| Calcineurin inhibitor | 82 (21) | 1 (0) | 81 (83) | <.01 |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 69 (18) | 2 (1) | 67 (68) | <.01 |

| Azathioprine | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | .31 |

| Rituximab | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | N/A |

| Other major ISU therapy | 20 (5) | 7 (2) | 13 (13) | <.01 |

| Vital signs on the day of ICU admission – median (IQR) | ||||

| Temperature – ⁰Cd | 37.8 (37.1-38.6) | 37.9 (37.2-38.8) | 37.4 (36.9-38.2) | <.01 |

| Lowest systolic blood pressure – mm Hg | 99 (88-114) | 98 (86-112) | 105 (92-117) | .03 |

| Highest heart rate – beats per min | 103 (90-118) | 103 (91-118) | 101 (88-116) | .32 |

| Laboratory findings on the day of ICU admission – median (IQR) | ||||

| White blood cell count – per mmd | 7.5 (5.5-10.5) | 7.9 (5.6-11.2) | 6.6 (4.9-8.5) | <.01 |

| Lymphocyte percentage – per mmf | 0.70 (0.45-1.05) | 0.79 (0.52-1.15) | 0.50 (0.30-0.81) | <.01 |

| Hemoglobin – g/dlg | 11.8 (10.0-13.8) | 11.7 (9.9-13.6) | 11.9 (10.6-13.6) | .47 |

| Serum creatinine – mg/dlh | 1.6 (1.0-2.8) | 1.5 (1.0-2.9) | 1.7 (1.0-2.7) | .42 |

| C-reactive protein – mg/Lj | 156 (88-223) | 159 (91-224) | 143 (84-208) | .49 |

| Serum albumin – g/dlk | 3.3 (2.8-3.6) | 3.3 (2.8-3.6) | 3.2 (2.9-3.6) | .55 |

| D-dimer - ng/mll | 1,254 (620-2,975) | 1,332 (610-3,402) | 1,140 (640-2,390) | .60 |

| Interleukin-6 - pg/mlm | 51 (15-184) | 68 (13-195) | 37 (15-84) | .61 |

| Serum ferritin – ng/mln | 1,132 (541-2,112) | 998 (450-1,983) | 1,429 (657-2,957) | .03 |

| Type of ventilation - no. (%): | ||||

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 226 (59) | 171 (59) | 55 (56) | .34 |

| BIPAP or CPAP | 7 (2) | 6 (2) | 1 (1) | |

| High-flow nasal cannula or nonrebreather mask | 88 (23) | 68 (24) | 20 (20) | |

| None of the above | 65 (17) | 43 (15) | 22 (22) | |

Note: All other variables had no missing data.

Abbreviations: BiPAP, bilevel positive airway pressure ventilation; IQR, interquartile range; ISU, immunosuppressive; N/A, not applicable; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure ventilation; SOT, solid organ transplant.

e Data regarding white-cell count were missing for total 16 patients (4%), 3 SOT patient and 13 non-SOT patients.

i Data regarding estimated glomerular filtration rate were missing for total 13 patients (3.4%), 3 SOT patient and 10 non-SOT patients.

Data regarding days from symptom onset to ICU admission were missing for total 4 patients (1%), 1 SOT patient and 3 non-SOT patients.

Data regarding days from symptom onset to hospital admission were missing for total 14 patients (3.6%), 3 SOT patient and 11 non-SOT patients.

Corticosteroids: >10 mg prednisone/day (or equivalent).

Data regarding temperature were missing for total 2 patients (0.5%), 1 SOT patient and 1 non-SOT patients.

Data regarding lymphocyte percentage were missing for total 76 patients (19.6%), 18 SOT patient and 58 non-SOT patients.

Data regarding hemoglobin were missing for total 16 patients (4%), 3 SOT patient and 13 non-SOT patients.

Data regarding serum creatinine were missing for total 13 patients (3.4%), 3 SOT patient and 10 non-SOT patients.

Data regarding C-reactive protein were missing for total 150 patients (38.8%), 40 SOT patient and 110 non-SOT patients.

Data regarding serum albumin were missing for total 63 patients (16.3%), 14 SOT patient and 49 non-SOT patients.

Data regarding D-dimer were missing for total 194 patients (50%), 40 SOT patient and 154 non-SOT patients.

Data regarding interleukin-6 were missing for total 304 patients (79%), 75 SOT patient and 229 non-SOT patients.

Data regarding serum ferritin were missing for total 163 patients (42%), 34 SOT patient and 129 non-SOT patients.

3.3. Medications in the 14 days following ICU admission

Table 3 describes the treatments received in the 14 days after ICU admission. A higher proportion of SOT patients received corticosteroids (SOT: 65% vs. non-SOT: 38%, P < .001) and a lower proportion received nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (SOT: 0% vs non-SOT: 5%, P = .03) in the propensity score matched cohort. The use of other medications, including hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, remdesivir, tocilizumab, and anticoagulants, was similar between groups (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Treatments in the first 14 days after intensive care unit admission of nontransplant patients and solid organ transplant patients in the propensity score matched cohort

| Treatments | All patients (N = 386) | Non-SOT (N = 288) | SOT (N = 98) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotics/antivirals – no. (%) | ||||

| Chloroquine | 3 (1) | 1 (0) | 2 (2) | .10 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 258 (67) | 196 (68) | 62 (63) | .38 |

| Azithromycin | 199 (52) | 150 (52) | 49 (50) | .72 |

| Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin | 307 (80) | 233 (81) | 74 (76) | .25 |

| Remdesivir | 26 (7) | 20 (7) | 6 (6) | .78 |

| Ribavirin | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | .56 |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir (Kaletra) | 14 (4) | 11 (4) | 3 (3) | .73 |

| Therapeutic anticoagulation – no. (%)a | ||||

| Any | 176 (46) | 130 (45) | 46 (47) | .78 |

| Heparin drip | 132 (34) | 96 (33) | 36 (37) | .54 |

| Enoxaparin | 41 (11) | 35 (12) | 6 (6) | .09 |

| Bivalirudin | 4 (1) | 1 (0) | 3 (3) | .02 |

| Argatroban | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | .56 |

| Anti-inflammatory medications – no. (%) | ||||

| Corticosteroids | 173 (45) | 109 (38) | 64 (65) | <.01 |

| NSAIDs | 13 (3) | 13 (5) | 0 (0) | .03 |

| Aspirin | 128 (33) | 94 (33) | 34 (35) | .71 |

| Statin | 132 (34) | 92 (32) | 40 (41) | .11 |

| Tocilizumab | 70 (18) | 47 (16) | 23 (23) | .11 |

| Other interleukin-6 inhibitor or interleukin-6 receptor inhibitor | 2 (1) | 1 (0) | 1 (1) | .42 |

| Vitamin C | 32 (8) | 28 (10) | 4 (4) | .08 |

| Other medications – no. (%) | ||||

| Convalescent plasma | 12 (3) | 7 (2) | 5 (5) | .19 |

| ACE-I | 12 (3) | 10 (3) | 2 (2) | .48 |

| ARB | 14 (4) | 11 (4) | 3 (3) | .73 |

| Tissue plasminogen activator | 5 (1) | 4 (1) | 1 (1) | .78 |

| Specific interventions for hypoxemia – no. (%) | ||||

| Neuromuscular blockade | 142 (37) | 105 (36) | 37 (38) | .82 |

| Inhaled epoprostenol | 18 (5) | 13 (5) | 5 (5) | .81 |

| Inhaled nitric oxide (iNO) | 22 (6) | 14 (5) | 8 (8) | .22 |

| Prone position | 126 (33) | 92 (32) | 34 (35) | .62 |

| Enrolled in a clinical trial – no. (%)b | 75 (19) | 55 (19) | 20 (20) | .79 |

Note: Each of the above interventions was assessed during the 14 days following ICU admission. All other variables had no missing data.

Abbreviations: ACE-I, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; ICU, intensive care unit; N/A: not applicable; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; SOT, solid organ transplant.

Data on therapeutic anticoagulation were missing for 1 non-SOT patient (0.3%).

Data on enrollment in a clinical trial were missing for 1 non-SOT patient (0.3%).

3.4. Clinical outcomes and organ support

Tables 4 and 5 and Figure S2 show the clinical outcomes and organ support requirements in SOT and non-SOT patients. Death within 28 days of ICU admission was similar in SOT and non-SOT patients (40% and 43%, respectively; relative risk [RR] 0.92; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.70-1.22). Other outcomes and requirement for organ support were also similar between groups, including receipt of mechanical ventilation, development of acute respiratory distress syndrome, receipt of ECMO and receipt of vasopressors (TABLE 4, TABLE 5 and Figure S2). There was a trend toward higher risk of AKI requiring RRT in SOT vs. non-SOT patients (37% vs. 27%; RR [95% CI]: 1.34 [0.97-1.85]). Figure S3 shows the clinical outcomes and organ support requirements in SOT and non-SOT patients using the 1:1 PS matched cohort as a sensitivity analysis. Death within 28 days of ICU admission and requirement for organ support were also similar between groups (Figure S3). In addition, clinical outcomes, and organ support requirements were similar between kidney transplant patients versus nontransplant propensity score (PS) matched controls (Tables S4 and Figures S4).

TABLE 4.

Clinical outcomes and organ support requirement in nontransplant patients and solid organ transplant patients in the propensity score matched cohort

| Primary outcomes | Non-SOT (n = 288) | SOT (n = 98) | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Death within 28 days, n (%) | 124 (43) | 39 (40) | .57 |

| Cause of death, n (%)** | .50 | ||

| ARDS/respiratory failure | 39 (29) | 13 (30) | |

| Heart failure | 5 (4) | 1 (2) | |

| Septic shock | 16 (12) | 10 (23) | |

| Kidney failure | 42 (32) | 13 (30) | |

| Liver failure | 10 (8) | 2 (5) | |

| Other | 21 (16) | 4 (9) | |

| Days of ICU stay, median (IQR) | 11 (5-21) | 11 (7-19) | .42 |

| Mechanical ventilation (days 1-14) | |||

| Received mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 223 (77) | 78 (80) | .66 |

| Days of mechanical ventilation, median (IQR) | 11 (6-14) | 9 (6-13) | .18 |

| ECMO (days 1-14) | |||

| Received ECMO, n (%) | 9 (3) | 1 (1) | .26 |

| Days of ECMO, median (IQR) | 8 (5-9) | 14 (14-14) | .16 |

| Acute RRT (days 1-14) | |||

| Received acute RRT, n (%) | 79 (27) | 36 (37) | .08 |

| Days of acute RRT, median (IQR) | 7 (3-10) | 6 (3-9) | .76 |

| ARDS (days 1-14), n (%) | 205 (71) | 73 (74) | .56 |

| New infection (days 1-14), n (%) | 99 (34) | 24 (24) | .07 |

| New thromboembolic event (days 1-14), n (%) | 23 (8) | 9 (9) | .71 |

| Vasopressor (days 1-14) | |||

| Received vasopressor, n (%) | 201 (70) | 62 (63) | .23 |

| Days on vasopressor, median (IQR) | 5 (3-9) | 5 (3-9) | .52 |

Abbreviations: ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; RRT, renal replacement therapy; SOT, solid organ transplantation.

P values for continuous variables with median (IQR) are result of Mann-Whitney test and categorical variables are chi-square test.

Patients could have had more than one cause of death.

TABLE 5.

Relative risk of clinical outcomes and organ support in nontransplant patients and solid organ transplant patients in the propensity score matched cohort using binomial generalized linear model (log-binomial model) (SOT versus non-SOT [reference] patients)

| Primary outcomes | Relative risk | 95% confidence interval of relative risk | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Death within 28 days, n (%) | 0.92 | 0.70-1.22 | .58 |

| Mechanical ventilation (days 1-14) | 1.03 | 0.91-1.16 | .65 |

| ECMO (days 1-14) | 0.33 | 0.04-2.54 | .29 |

| Acute RRT (days 1-14) | 1.34 | 0.97-1.85 | .07 |

| ARDS (days 1-14), n (%) | 1.04 | 0.91-1.20 | .55 |

| New infection (days 1-14), n (%) | 0.71 | 0.48-1.04 | .08 |

| New thromboembolic event (days 1-14), n (%) | 1.15 | 0.55-2.40 | .71 |

| Vasopressor (days 1-14) | 0.91 | 0.77-1.07 | .26 |

Abbreviations: ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; RRT, renal replacement therapy; SOT, solid organ transplant.

3.5. Clinical outcomes and organ support requirements in the entire cohort

Table S5 and Figure S5 shows the clinical outcomes and organ support requirement in SOT and non-SOT patients in the entire cohort (n = 4,153). Similar to the propensity score matched cohort, death within 28 days, mechanical ventilation, ECMO requirement, development of ARDS, secondary infection, thromboembolic events, and requirement for vasopressors were all similar between groups. The risk of AKI requiring RRT was higher in SOT patients compared to non-SOT patients (36% in SOT vs. 19% in non-SOT, RR unadjusted model [95% CI]: 1.89 [1.46-2.46], RR adjusted model [95% CI]: 1.43 [1.09-1.87]) (Table S5 and Figure S5).

4. DISCUSSION

We used data from a large, nationally representative, multicenter cohort study of critically ill adults with COVID-19 to compare outcomes of SOT patients with non-SOT patients. We present 3 major findings. First, 28-day mortality in SOT patients was similar to non-SOT patients. Second, there was no difference between groups in the duration of ICU length of stay, risk of ARDS, secondary infection, thromboembolic events, vasopressor use, or receipt or duration of invasive mechanical ventilation. Finally, SOT patients had a trend toward higher rates of AKI requiring RRT. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study assessing outcomes of COVID-19 infection in SOT patients using a control group of nontransplant patients as comparator in ICU patients.

Our study suggests that SOT status is not associated with a higher risk of mortality in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Our observed mortality rate of 40% in SOT patients and 43% in the non-SOT group is lower than the 62% mortality rate reported among critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan3 and the 50% mortality rate reported in the Seattle region.5 It was, however, higher than other cohorts from Italy (26%) 7 and New York City (15%-21%).4 , 6 These comparisons are limited by different risk profile of patients, ICU admission criteria, and follow-up. Similarly, the case fatality rate of COVID-19 in hospitalized SOT patients reportedly varies between 10%-33%,8 , 9 , 13, 14, 15, 16 but among critically ill SOT patients it may be as high as 50%.8 Previous experience with respiratory viruses suggests a higher mortality in SOT patients compared to non-SOT patients, yet we report no difference in the 28-day mortality risk in our cohort. One potential explanation is that there was a higher use of corticosteroid treatment in SOT patients compared to non-SOT patients. The recent “Randomised Evaluation of COVid-19 thERapY (RECOVERY)” study indicated that dexamethasone therapy reduces death by up to one third in hospitalized patients with severe respiratory complications of COVID-19.25 We hypothesize that immunosuppressive medications may have mitigated proinflammatory cytokine activation in SOT patients, which might result in lower risk of developing cytokine release syndrome. Since the earliest reports of COVID-19 infection, cytokine release syndrome has been identified as a primary contributor to the pathophysiology of severe COVID-19 infection, including ARDS and organ dysfunction.26 , 27 Coronavirus infection results in the activation of monocyte, macrophage, and dendritic cells, which in turn release interleukin-6 (IL-6) and other cytokines, contributing to the clinical manifestations of severe infection. Ensuing endothelial injury can lead to multiorgan involvement. However, in our dataset C-reactive protein levels and IL-6 levels were similar between the 2 groups despite the immunosuppression, which does not support our hypothesis. In addition, serum ferritin level was higher in SOT patients. Further studies are needed to clarify the potential role of cytokine release syndrome in this population.

SOT patients had a nonsignificant trend toward a more than 30% higher risk of AKI requiring RRT compared to their non-SOT counterparts similar to what was reported in a recent single-center study.23 Initial reports of AKI in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 varied from 15% to 50%9 , 13 , 18 , 19 and has been reported to be as high as 90% among mechanically ventilated patients.28 A multicenter cohort study of more than 5000 hospitalized patients from New York City reported a 36% incidence of AKI, with 14% of those with AKI (5% of all patients) requiring RRT.28 In another large study of 3235 hospitalized patients from New York City with 815 ICU patients, the need for RRT was present in 34% of ICU patients,29 which is similar to our reported results. Similarly, the reported incidence of AKI in SOT patients varies according to the type of organ transplant and severity of disease.30 In the first report of US kidney transplant patients, 40% (6/15) of the patients had AKI and 2 patients required RRT.15 The mechanisms of AKI in transplant patients are multifactorial. Virus particles can directly infect the renal tubular epithelium and podocytes through an angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2)-dependent pathway and cause mitochondrial dysfunction and acute tubular necrosis. Endothelial dysfunction due to endothelial injury increases the risk of microthrombi and contributes to AKI.11 In addition to AKI associated with ARDS and critical illness, use of calcineurin inhibitors as the predominant immunosuppression could increase the risk of endothelial injury in these patients; especially in the setting of higher rate of diarrhea.

There was a significant difference in symptoms at presentation between SOT and non-SOT patients. Fever and cough were the most common symptoms in both groups, consistent with previous description of COVID-19 symptoms. Interestingly, SOT patients presented with more nasal congestion and diarrhea compared to non-SOT patients. Although other case reports and cohorts of SOT patients presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms exist,20 , 31 this has not been consistently shown in other studies, where the presenting symptoms in SOT patients were similar to the general population.18 , 22 , 32 Our findings are important, as diarrhea in SOT patients is common and can be multifactorial, related to medications or other viral infections. Given the myriad of clinical manifestations that have been described in patients with COVID-19, the index of suspicion for COVID-19 should be high in SOT patients who present with gastrointestinal symptoms.

Our study has several strengths. First, we included patients from geographically diverse sites from across the United States, thereby maximizing generalizability. Second, we used propensity score matching to create comparable groups to assess the risk of SOT status with several clinically relevant outcomes. Third, all data were captured by manual chart review, which allowed us to include detailed and reliable data on both clinical characteristics and outcomes. Fourth, to the best of our knowledge our study included the highest number of SOT ICU patients from the United States. Finally, all patients had follow-up until the first of hospital discharge, death, or at least 28 hospital days.

Our study also has its limitations. First, the transplant vintage of SOT patients was not available in this dataset and hence, the effect of duration of immunosuppression and time since transplantation on outcomes cannot be determined. Second, although we captured data on the use of immunosuppressive medications prior to hospital admission, we did not capture data on their use following ICU admission. Thus, our study does not address the important question of whether, and how, immunosuppression should be decreased in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Third, our study collected data in the first 14 days of ICU stay, so our study does not address the potential association with data after first 2 weeks of ICU stay. Finally, these observations are restricted to ICU patients and may not be applicable for non-ICU or ambulatory SOT patients.

5. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, SOT patients with critical illness due to COVID-19 infection have a similar risk of death, ARDS, and requirement for organ support as non-SOT patients. Further studies are needed to assess the effect of specific immunosuppression and other therapeutic regimens on clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgments

DISCLOSURE

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from The Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Inc. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available from Dr Miklos Z Molnar with the permission of The Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Inc.

Footnotes

David E. Leaf and Csaba P. Kovesdy contributed equally to this manuscript.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section.

REFERENCES

- 1.Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center. August 11th, 2020. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu

- 2.Wang D, Yin Y, Hu C, et al. Clinical course and outcome of 107 patients infected with the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, discharged from two hospitals in Wuhan, China. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):188. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02895-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(5):475–481. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goyal P, Choi JJ, Pinheiro LC, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Covid-19 in New York City. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(24):2372–2374. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2010419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhatraju PK, Ghassemieh BJ, Nichols M, et al. Covid-19 in Critically Ill Patients in the Seattle Region - Case Series. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):2012–2022. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2004500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting Characteristics, Comorbidities, and Outcomes Among 5700 Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19 in the New York City Area. JAMA. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline Characteristics and Outcomes of 1591 Patients Infected With SARS-CoV-2 Admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1574. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pereira MR, Mohan S, Cohen DJ, et al. COVID-19 in solid organ transplant recipients: Initial report from the US epicenter. Am J Transplant. 2020;20(7):1800–1808. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alberici F, Delbarba E, Manenti C, et al. A single center observational study of the clinical characteristics and short-term outcome of 20 kidney transplant patients admitted for SARS-CoV2 pneumonia. Kidney Int. 2020;97(6):1083–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manuel O, Estabrook M. American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of P. RNA respiratory viral infections in solid organ transplant recipients: Guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin Transplant. 2019;33(9):e13511. doi: 10.1111/ctr.13511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ronco C, Reis T, Husain-Syed F. Management of acute kidney injury in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(7):738–742. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30229-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jin Y, Yang H, Ji W, et al. Virology, Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Control of COVID-19. Viruses. 2020;12(4):372. doi: 10.3390/v12040372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akalin E, Azzi Y, Bartash R, et al. Covid-19 and Kidney Transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(25):2475–2477. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2011117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nair V, Jandovitz N, Hirsch JS, et al. COVID-19 in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2020;20(7):1819–1825. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Columbia University Kidney Transplant Program Early Description of Coronavirus 2019 Disease in Kidney Transplant Recipients in New York. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(6):1150–1156. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020030375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernández-Ruiz M, Andrés A, Loinaz C, et al. COVID-19 in solid organ transplant recipients: A single-center case series from Spain. Am J Transplant. 2020;20(7):1849–1858. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Banerjee D, Popoola J, Shah S, Ster IC, Quan V, Phanish M. COVID-19 infection in kidney transplant recipients. Kidney Int. 2020;97(6):1076–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoek RAS, Manintveld OC, Betjes MGH, et al. Covid-19 in solid organ transplant recipients: A single center experience. Transpl Int. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Tschopp J, L’Huillier AG, Mombelli M, et al. First experience of SARS-CoV-2 infections in solid organ transplant recipients in the Swiss Transplant Cohort Study. Am J Transplant. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Yi SG, Rogers AW, Saharia A, et al. Early Experience With COVID-19 and Solid Organ Transplantation at a US High-volume Transplant Center. Transplantation. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Travi G, Rossotti R, Merli M, et al. Clinical outcome in solid organ transplant recipients with COVID-19: A single-center experience. Am J Transplant. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Fung M, Chiu CY, DeVoe C, et al. Clinical Outcomes and Serologic Response in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients with COVID-19: A Case Series from the United States. Am J Transplant. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Chaudhry ZS, Williams JD, Vahia A, et al. Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of COVID-19 in Solid Organ Transplant Recipients: A Case-Control Study. Am J Transplant. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Gupta S, Hayek SS, Wang W, et al. Factors Associated With Death in Critically Ill Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 in the US. JAMA. Intern Med. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Low-cost dexamethasone reduces death by up to one third in hospitalised patients with severe respiratory complications of COVID-19. 2020 [cited 2020 June 17th, 2020]; >http://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2020-06-16-low-cost-dexamethasone-reduces-death-one-third-hospitalised-patients-severe#

- 26.Ronco C, Reis T. Kidney involvement in COVID-19 and rationale for extracorporeal therapies. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16(6):308–310. doi: 10.1038/s41581-020-0284-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang C, Wu Z, Li JW, Zhao H, Wang GQ. Cytokine release syndrome in severe COVID-19: interleukin-6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab may be the key to reduce mortality. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55(5):105954. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirsch JS, Ng JH, Ross DW, et al. Acute kidney injury in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Chan L, Chaudhary K, Saha A., Baweja M et al. Acute Kidney Injury in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19. medRxiv. 2020.

- 30.Williams C, Borges K, Banh T, et al. Patterns of kidney injury in pediatric nonkidney solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2018;18(6):1481–1488. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guillen E, Pineiro GJ, Revuelta I, et al. Case report of COVID-19 in a kidney transplant recipient: Does immunosuppression alter the clinical presentation? Am J Transplant. 2020;20(7):1875–1878. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akdur A, karakaya E, Ayvazoglu soy EH, et al. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) in Kidney and Liver Transplant Patients: A Single-Center Experience. Exp Clin Transplant. 2020;18(3):270–274. doi: 10.6002/ect.2020.0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from The Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Inc. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available from Dr Miklos Z Molnar with the permission of The Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Inc.