Abstract

Objective

To provide a quick, in the moment analysis of the social and political aspects of the COVID‐19 pandemic to preserve the possibly ephemeral aspects that might be overlooked in future historical studies.

Methods

Qualitative and a statistical analyses of real time information.

Results

The clustering of former imperial powers as states suffering extreme initial impacts, combined with a brief qualitative commentary on the domestic politics related to the pandemic response, suggests that colonial imperialism has lingering domestic political effects.

Conclusion

The domestic political power bases that enabled colonial imperialism may be a significant and previously unrecognized factor in politics both in the context of disaster response and more broadly.

While it is always a challenge, and an intellectual risk, to analyze political and social events as they occur, particularly when they are unfolding on a global scale, there are several aspects of the 2020 COVID‐19 pandemic that may well be difficult to understand if only examined in hindsight. From the challenge that leaders faced in securing reliable data and interpreting them in the moment when decisions had to be made, all the way down to the emergence, growth, and sometimes deadly consequences of snake‐oil scams and conspiracy theories, there are countless, often intangible, aspects of the pandemic that could be lost to the academic perspective as “the fog of war” dissipates and the clarity of hindsight alters our perspectives.

Of all the ephemeral vagaries inherent in the experience of an extreme crisis, the psychology of the moment is a particularly challenging element for the study of the social and political facets of disaster risk reduction (DRR), crisis management, and disaster response. By definition, a disaster is a catastrophic event that is beyond a community's ability to respond to, and that displacement into what might only be described as communal helplessness can defy even the most concerted and determined analytical efforts. For example, the irrational local resistance to building DRR elements into postdisaster rebuilding efforts was a puzzle that persisted for nearly half a century before an accidental observation led to a possible explanation. It was the “in the heat of the moment” language used by the most passionate and vocal opponents of the DRR efforts being included in the recovery from the 2011 Christchurch earthquake that was the key. The wording indicated that the psychology of loss‐framing and the instincts behind prospect theory (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979) were a huge factor. Building the way that loss‐framing would lead a significant minority of individuals to overvalue the previous status quo into an aggregated rational choice model then offered an explanation for the phenomenon where affected communities resist including even externally funded DRR efforts in the rebuilding process (Van Belle, 2015).

Those “in the moment” elements of crisis can also be ephemeral. They either do not appear in post hoc recollections or people's memories of those moments are reframed or rationalized in ways that obscure or transform them. For example, a variation of Coser's social psychology of the group response to threats (Coser, 1956) is probably the best explanation for why Hollywood's obsession with the drama of panic and looting is simply not found in the reality of a disaster (Van Belle, 2012). Many who have personally experienced those first few hours after a catastrophe strikes can offer anecdotes of unexpected combinations of people coming together in amazing ways to act as a group, but it has so far proven impossible to find a way to measure and analyze that group response outside of those real‐time observations.

This brief analysis, and the discussion that follows, are offered as a way to engage the context from within the moment of crisis, with the hope that it might help contextualize future academic studies by providing a foundation for at least some degree of comparison between post hoc and in vivo perspectives. The idea is to provide the social science equivalent of the real‐time modeling and analysis of epidemiological data that many expect will provide a panacea for future study. The currently available data are a mess, the analysis is simplistic, and the discussion is highly speculative, but we still offer them as a representation of how theories, ideas, and our backgrounds in the social and political aspects of disaster response and DRR enable our understanding of the pandemic as it unfolds, on May 8, 2020.

The Extreme Impact of COVID‐19 on Former Colonial Empires

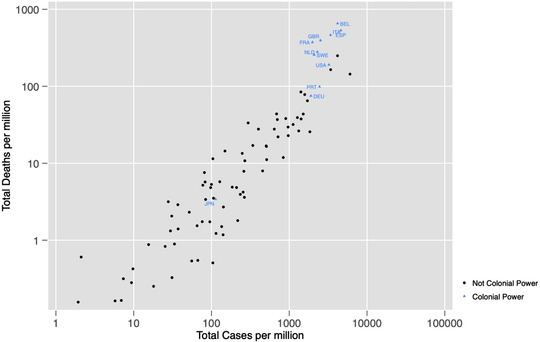

No matter how you examine the currently available data, the first wave of the COVID‐19 pandemic has had a disproportionately severe impact upon the states that were once colonial imperial powers, with Japan as the only one showing anything close to a median experience (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Total Deaths per Million and Total Cases per Million in Democratic States (Log Scale)

Figure 1 1 charts reported deaths per Million population against confirmed cases per Million for democracies (6 or higher in the 2015 Polity 2 data) on logarithmic scales as of May 8, 2020. We use countries that built empires through the active colonization of external territory, starting with Portugal in the 17th century, as our definition of colonial empires. Sweden might be considered a borderline case. The use of democracies rather than all states reflects what is the most appropriate set of cases for the discussion. Using all states changes little. It adds Russia as an imperial power, but Russia is right up among the colonial empires that have become democratic powers, and it adds a significant number of additional data points in the lower left quadrant, but what is visually apparent here is just as clear in that more cluttered chart of the data. A chart with a logarithmic scale is offered here as an example because it best shows how Japan lies right in the middle of the scatter of noncolonial democracies, but the pattern shown here is clear regardless of how the data are charted.

Similarly, the relationship between a history of imperial colonialism and pandemic impact thus far is clear in a simple OLS analysis (Table 1). As is the case with visually charting the currently available data, the simple correlation is robust and substantial regardless of whether all, or just democratic, states are examined. This confirms what is apparent in charting the data, but the R 2 of 0.589 also quantifies just how much of the variation is explained by this single factor. While clarifications and refinements of the data are expected, and other factors are undoubtedly going to be found to be statistically significant, the odds are that a history of imperial colonialism, or some close proxy measure, is going to be a critical element in understanding this first wave of the pandemic.

TABLE 1.

Colonial Powers and Deaths per Million in Democratic States

| Colonial power | 281.458*** |

| (59.350) | |

| Constant | 20.360*** |

| (4.645) | |

| Observations = 85 | |

| R 2 = 0.589 |

note: Standard errors are in parentheses;

*** p < 0.001.

Both the visualization and correlation confirm the qualitative impression created by the real‐time observation of the unfolding responses to the pandemic. From flirting with or even attempting some variation of pursuing herd immunity through widespread infection, to significant domestic resistance and defiance of measures employed to limit or slow the infection, to the fact that it is actually difficult to imagine that the U.S. federal government could have offered a more catastrophic response if it tried, most of these former colonial powers are the states that many, even casual, observers would expect to see as the most heavily impacted by the first wave of infection.

The question is why; and that is where the perspective of an analysis from within the moment might offer potential insights valuable for those conducting post hoc analyses. While a variety of explanations related to the lingering effects of colonial imperialism will have to be explored, what is most striking for those working with DRR issues and watching things unfold is what might best be referred to as the social psychology of colonialism. It is both a dramatic and salient factor in this group of states and it is apparent in all of the different ways that they seem to be struggling to respond to the pandemic.

Economic Dehumanization as a Necessary Condition for Colonial Imperialism

One thing that seems apparent to a pair of scholars who both are deeply familiar with the countries that have arguably offered the best (New Zealand) and the worst (the United States) responses to the pandemic to date, is that there seems to be a profound difference in what might be called the sociopsychological makeup of these two countries. In the United States, the Republican Party has found significant and salient political support for prioritizing wealth over human life. In stark contrast, in New Zealand a similar call to risk, or indeed sacrifice, lives to quickly reopen the economy fell flat and was ridiculed to such an extent that it immediately stoked speculation in the news media that the leader of the largest conservative political party, the National Party, would be ousted for even suggesting that path forward, and shortly after this article was written, he was replaced.

More broadly, the fundamental philosophical premise of prioritizing lives over wealth has resonated throughout New Zealand (Jamieson, 2020). Public approval for that approach to the pandemic response, which has been clearly, repeatedly, and pointedly expressed by Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, has found support of over 90 percent in polling. Voluntary public compliance with one of the most extreme lockdowns in the world has been extremely high, and the extent of the peer‐policing of the lockdown rules has been notable, leading to a near elimination of lockdown defiance after only a few days. Both support and compliance have remained so high that after six weeks of lockdown, even minor incidents of rule breaking are newsworthy. The contrast to the United States, where the president openly encouraged heavily armed mobs to storm state houses to demand the end of far less restrictive measures, could not have been greater. Clearly, there is a significant, politically powerful, and highly motivated set of powerbases in the United States that do not just prioritize the pursuit of wealth over human life, they do so to an extreme. While it may not be as extreme in other former colonial powers, something similar does seem to be at work even in Sweden, which can only be considered a marginal case as a colonial imperial power.

The theoretical foundations of the literature examining mass dehumanization of the opponent as a necessary condition for lethal international conflict (Hunt, 1997; Van Belle, 1997) suggests that there may have been a similar necessary condition related to imperialism. We posit that a significant and empowered political base that prioritized wealth over human life was a necessary condition for the domestic political embrace of colonial imperialism. A secondary element of this would be a proclivity to embrace casting groups as “the other” as a normal aspect of political discourse, further discounting the value of their lives in relation to economic considerations.

Should it be the case that establishing a significant domestic political powerbase prioritizing wealth over life is a necessary condition for colonial imperialism, it also seems likely that once established, that powerbase would persist as a coherent political force. In the process of adapting to the end of colonial empire, those who hold that prioritization would be a potent powerbase in a democratic society and would not only be part of the transition into postcolonial economic structures and relationships, but the political and economic elites that benefit from their support would be motivated to sustain them and that critical core philosophical orientation as a coherent group to be exploited. In contrast, countries that were never colonizing powers would have offered far less economic and political reward for those who hold that prioritization of wealth over life and would have fewer or limited structures to empower them as a coherent force in the political or economic arenas as the world moved past colonial imperialism.

What Might This Explain?

While the domestic politics of having a potent domestic political power base that prioritizes wealth over life is posited as an explanation for why former colonial powers have been impacted so heavily by the first wave of COVID‐19, and why so many of them seem to be examples of poor or troubled national responses to the pandemic, there are other aspects of what we are seeing in the current situation that fit with that dynamic.

Japan could be explained as an imperial outlier that has so far only seen a roughly median impact of the outbreak because of its crushing defeat in WWII. The democratic political structure that was imposed by the United States after the war effectively removed that element as a significant aspect of its domestic politics. A similar explanation could be offered for why Germany, while still suffering far more than the norm, is toward the lower end of the former imperial powers. While the allies may have tried to eliminate the wealth‐over‐life mindset of imperialism from Germany's domestic politics, Germany's place in the Cold War, combined with the persistence of Nazi idolizers around the world, may have sustained the way that mindset motivates just enough individuals to create more difficulties than noncolonial democracies have faced.

The most powerful and economically successful of the colonial empires, the United States and the United Kingdom, are also the examples of what most would qualitatively argue are the worst responses, and the U.S. version of colonial imperialism, where most of the processes fell under the rubric of manifest destiny and westward expansion across the continent, might also explain why Brazil is an outlier among the noncolonial powers. Brazil's “conquest of the Amazon” is effectively an internal colonization of indigenous lands within their internationally recognized borders, and would likely produce a domestic powerbase similar to those that arose in countries that colonized externally.

We can take that notion of a group prioritizing wealth over human life as a political power base further and look at one obvious aspect of the situation in the United States. If we consider the politics and economics of slavery in the U.S. South as the ultimate manifestation of that prioritization, it should not be surprising that the armed mobs that stormed statehouses demanding that efforts to limit the spread of the virus be halted, as well as the protestors who did not resort to terrorism in their demand that lives be sacrificed for the good of the economy, sported Confederate flags.

These causal explanations are obviously quite speculative. Just as obviously, there is a great deal of room for disputing and debating the premise that establishing a significant domestic political powerbase that values wealth over human life was a necessary condition for colonial imperialism, or that it would persist as such a potent force in these nations. However, we believe that the basic point—that this appears to be a significant factor from within the crisis as it unfolds and develops—will prove valuable to those who study the COVID‐19 pandemic as a historical event.

Footnotes

Data are from Roser et al. (2020); retrieved on May 8, 2020 from 〈https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus〉.

REFERENCES

- Coser, L. A. 1956. The Functions of Social Conflict (Vol.). Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, W. B. 1997. Getting to War: Predicting International Conflict with Mass Media Indicators. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson, T. 2020. “‘Go Hard, Go Early’: Preliminary Lessons from New Zealand's Response to COVID‐19.” The American Review of Public Administration. Omaha: University of Nebraska; 50:6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D. , and Tversky, A. 1979. “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk.” Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society 47:263–91. [Google Scholar]

- Roser, M. , Ritchie, H. , Ortiz‐Ospina, E. , and Hasell, J. 2020. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID‐19) . Available at 〈https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus〉.

- Van Belle, D. A. 1997. “Press Freedom and the Democratic Peace.” Journal of Peace Research 34(4):405–14. [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2012. "Science Fiction and the Human Response to Disasters." Paper presented at the Science Fiction and Society, Oral Roberts University, Tulsa, OK. [Google Scholar]

- ———. 2015. “Media's Role in Disaster Risk Reduction: The Third‐Person Effect.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 14:9. [Google Scholar]