Abstract

Objectives

The primary aim of the study is to provide recommendations for the investigation and management of patients with new onset loss of sense of smell during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Design

After undertaking a literature review, we used the RAND/UCLA methodology with a multi‐step process to reach consensus about treatment options, onward referral, and imaging.

Setting and participants

An expert panel consisting of 15 members was assembled. A literature review was undertaken prior to the study and evidence was summarised for the panellists.

Main outcome measures

The panel undertook a process of ranking and classifying appropriateness of different investigations and treatment options for new onset loss of sense of smell during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Using a 9‐point Likert scale, panellists scored whether a treatment was: Not recommended, optional, or recommended. Consensus was achieved when more than 70% of responses fell into the category defined by the mean.

Results

Consensus was reached on the majority of statements after 2 rounds of ranking. Disagreement meant no recommendation was made regarding one treatment, using Vitamin A drops. Alpha‐lipoic acid was not recommended, olfactory training was recommended for all patients with persistent loss of sense of smell of more than 2 weeks duration, and oral steroids, steroid rinses, and omega 3 supplements may be considered on an individual basis. Recommendations regarding the need for referral and investigation have been made.

Conclusion

This study identified the appropriateness of olfactory training, different medical treatment options, referral guidelines and imaging for patients with COVID‐19‐related loss of sense of smell. The guideline may evolve as our experience of COVID‐19 develops.

Keywords: corona virus, COVID‐19, loss of sense of smell, olfactory training, RAND/UCLA

Key points.

Patients with isolated loss of smell for less than 3 months may be managed by their GP.

Smell training should be recommended for all patients with loss of smell persisting for more than 2 weeks.

When ENT referral is necessary, remote ENT consultation may be offered instead of a face‐to‐face consultation depending on duration of symptoms and associated nasal symptoms.

An MRI of brain is not recommended for patients with loss of smell associated with COVID‐19 infection regardless of loss of smell duration.

Olfactory training is recommended to patients with LOS more than 2 weeks.

1. INTRODUCTION

At the time of writing (12 May 2020), there have been 226 000 confirmed cases of COVID‐19 in the UK. Using data available through the COVID‐19 Symptom tracker which is monitoring over 2.5 million members of the public, it is estimated that there have been in excess of 2 million cases.

The British Rhinological Society (BRS) and ENTUK were the first to report that loss of smell or taste may be an important symptom. There has been a rapid growth in the evidence base supporting the initial observations made by the BRS/ENTUK that an apparent rise in incidence of loss of sense of smell reflected the onset of the COVID‐19 pandemic. 1 , 2 , 3

A previously published systematic review suggests a prevalence of self‐reported loss of sense of smell in 50% of patients 4 with COVID‐19. Emerging data suggest a high rate of early recovery, but at 4‐6 weeks after onset, approximately 10% patients have not experienced any recovery and still self‐report severe loss of sense of smell. Applying the prevalence and recovery rates to estimated cases in the UK, there are likely already more than 100 000 new cases of severe loss of sense of smell persisting beyond the first few weeks of COVID‐19infection. We do not yet know the potential for long‐term recovery, but we anticipate that both GPs and ENT doctors will see an increase in the number of patients presenting for advice.

As there is a high rate of spontaneous recovery reported across all studies within 2 weeks of onset of symptoms, therefore we will consider only patients where duration of loss or reduction of sense smell (LOS), with or without loss of sense of taste, is longer than 14 days or more. Furthermore, respiratory deterioration typically occurs between day 7‐12 after onset of symptoms, and this period should be allowed to pass before considering specific treatments, particularly as the safety of treatments in the setting of severe COVID‐19 has yet to be fully established for any treatments considered.

Self‐reported loss of taste may be caused by either loss of flavour due to loss of retronasal olfactory function or true loss of gustatory function. However, we will not attempt to differentiate or address this in this guidance, which will focus on self‐reported loss of sense of smell.

The aim of this guidance is to provide evidence‐based recommendations for the management of patients with COVID‐19 related loss of sense of smell, while at the same time trying to optimise use of resources but ensuring those with alternative pathologies are identified in a timely manner. As no COVID‐19 specific evidence yet exists we formed an expert panel and asked them to apply their experience in interpreting the current evidence base on the management of post‐viral olfactory loss. We considered both investigation of patients presenting with loss of sense of smell during the COVID‐19 pandemic and management of post‐COVID‐19 loss of sense of smell.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Ethical considerations

No formal ethical approval was required. Only CH and MA could access individual responses and group responses and comments were anonymised prior to recirculation.

2.2. Participants

An expert panel of 15 members was assembled, comprising of members of the BRS Council, members of an ENTUK taskforce charged with developing guidance for outpatient practice in ENT and representatives of the Global Consortium of Chemosensory Research.

The guidelines were initiated by and have been endorsed by the BRS.

2.3. Setting

A comprehensive literature review has been undertaken, by CH and MA, using Medline, Cochrane databases. We searched MEdRxIv, a preprint server for evidence specific to COVID‐19 but did not find any relevant studies. Evidence was summarised for the panellists (Appendix S1), and this was largely derived from systematic reviews which were circulated in full to the panel with the questions in order to minimise risk of bias being introduced through the summaries produced. Studies were considered if they included any patients with post‐viral olfactory loss, or idiopathic loss. Some treatments identified by the literature review were excluded if included in a systematic review and shown to be ineffective, if the treatment was unavailable in the UK or if the mode of administration could not be supported during the pandemic (for example, repeated intravenous administration), or if regular face to face contact was required for administration or monitoring (Appendix S2).

2.4. Study design

We used the RAND/UCLA methodology, a modified Delphi communication method, where a group of experts using a multi‐step process reach consensus over a series questions based on clinical scenarios. Questions were designed by CH and MA, and the evidence summaries and questions were circulated for comments to a subgroup of the panel to ensure that all important aspects were addressed and the questions were clearly presented prior to scoring.

Our expert panel undertook a process of ranking and classifying appropriateness of different investigations and treatment options. Using a 9‐point Likert scale, panellists scored whether a treatment was:

Not recommended: should not be undertaken or prescribed based on current evidence base as risks outweigh likely benefits, 1 , 2 , 3

Optional: could be undertaken or prescribed based on discussion with individual patient based on likely risks versus benefits, 4 , 5 , 6

Recommended: should be undertaken or prescribed in all patients unless there are contraindications as benefits outweigh likely risks. 7 , 8 , 9

Free text comments were encouraged if greater context was required, if questions were ambiguous, or if any intervention or investigation had been overlooked. For each intervention or investigation, several options were given in terms of timings (eg commencing treatment at 2, 4 weeks or later). A question was posed for each intervention to ask if the time points given should be amended for the next round.

Specific combinations of treatments were not considered as the evidence base does not currently have sufficient data to evaluate for any enhanced effectiveness when used in combination. However, multiple options could be considered and recommended, and none of the treatments would be considered a contra‐indication to use of any others.

Upon receiving the results, the classification of recommendation was based on the mean ranking scores collated from each clinical scenario provided that there was consensus.

Consensus was defined as the requirement for more than 70% of responses to fall into the category defined by the mean, and when the mean score sits in ‘recommended’, less than 15% of responses fall into not recommended, and vice versa. Where consensus was not reached, items were reconsidered in a further round.

Disagreement was declared if more than 30% of responses fell in both recommended and not recommended; in this setting, no recommendation could be given.

Where a recommendation was made to start treatments at several time points, the earliest point was given as a recommendation.

Panellists were given 72 hours to return their answers. The scores at the end of round 1 were analysed and represented to the group, with each individual receiving a copy of their own initial evaluation. The panel was then asked to repeat the scoring for any items where consensus had not been reached. After the second round, any remaining items that had not reached consensus were further reviewed.

3. RESULTS

Six items reached consensus at the end of round 1. Some questions were amended for the second round in response to comments from panellists; for example, many panellists requested information on COVID‐19 status and endoscopy findings in order to make recommendations. Steroid rinses were identified as a missing treatment and added.

All panellists completed both rounds of the Delphi process.

After the second round, consensus had been achieved on most items. There was disagreement on the use of Vitamin A drops, and therefore, no recommendations have been made in the guideline.

In 4 areas, consensus could not be achieved at the 70% threshold, but was met at 60%. Further discussion lead to consensus regarding imaging. The remaining items related to treatment using oral corticosteroids, steroid drops or rinses and omega‐3 supplements. The mean score for these items was 5, and 60‐67% considered these an option, and less than 15% would not recommend. They have been included as an option, but the uncertainty regarding the balance of risk and benefit should be discussed with the patient, and a decision made on an individual basis.

3.1. Recommendations

3.1.1. ENT referral

Isolated loss of smell (LOS)

-

Patients who have had COVID‐19 infection based on history (eg known contacts), PCR or serology

-

LOS less than three months:

The patient may be managed by their GP.

Loss of sense of smell advice sheets provided and treatment discussed (smell training and optional treatments outlined below)

-

LOS more than three months:

ENT referral.

Remote ENT consultation should be offered initially instead of a face‐to‐face consultation.

-

-

Patients with no known prior COVID‐19 infection based on history (eg known contacts), PCR or serology

-

LOS more than 4‐6 weeks:

ENT referral.

Remote ENT consultation may be offered instead of a face‐to‐face consultation.

-

LOS more than 3 months:

ENT referral.

A face‐to‐face ENT consultation should be considered to exclude other pathologies.

-

Loss of smell (LOS) associated with nasal symptoms

All patients with LOS more than 4‐6 weeks associated with nasal symptoms should be referred to ENT for consideration of a face‐to‐face consultation ± nasendoscopy to exclude other pathologies.

Endoscopy findings should direct decisions regarding further imaging if possible.

3.1.2. Investigatons

COVID‐19 status should be established through history/PCR/serology in patients if possible.

Isolated loss of smell (LOS)

-

Patients who have had COVID‐19 infection based on history (eg known contacts), PCR or serology (regardless of LOS duration)

An MRI scan of brain is not recommended

-

Patients with no prior COVID‐19 infection based on history (eg known contacts), PCR or serology (LOS more than 3 months)

An MRI scan of brain is recommended if endoscopy is normal

Loss of smell for more than 4‐6 weeks associated with persistent nasal symptoms (regardless of COVID‐19 status)

Nasal endoscopy should be performed prior to imaging. However, given the risks surrounding endoscopy and limited availability, imaging may be requested first in selected cases.

If endoscopy is normal, further imaging is recommended (either MRI or CT).

Unilateral lesions or suspicion of malignancy on endoscopy needs urgent investigation with MRI/CT.

Benign findings (eg nasal polyps) should be treated medically before considering imaging.

Loss of smell associated with neurological symptoms (excluding gustatory dysfunction)

All patients with LOS more than 4‐6 weeks with additional neurological symptoms should have an MRI scan of brain regardless of prior COVID‐19 status.

3.1.3. Management

COVID‐19 status should be established through history/PCR/serology in patients if possible.

The recommendation is divided into:

1) Recommended, 2) Not Recommended, and 3) Optional*.

Olfactory training and support

Olfactory training is recommended to patients with LOS more than 2 weeks.

It is recommended that loss of sense of smell advice is provided to the patients.

It is recommended that patients are directed to AbScent and Fifth Sense for further support.

Intranasal corticosteroid sprays

It is recommended in patients with LOS more than 2 weeks associated with nasal symptoms.

Intranasal corticosteroid drops or rinses

It is optional to recommend intranasal steroid drops or rinses in patients with LOS more than 2 weeks associated with nasal symptoms.

Oral corticosteroids

It is not recommended to prescribe oral corticosteroids for a patient with LOS more than 2 weeks with persistent COVID‐19 symptoms.

It is optional to recommend oral corticosteroids for a patient with LOS more than 2 weeks as an isolated symptom or following resolution of any other COVID‐19 symptoms.

Vitamin A drops

Due to disagreement within the group, it was not possible to make a recommendation regarding the use of Vitamin A drops.

Alpha‐lipoic acid

It is not recommended for a patient with LOS more than 2 weeks as an isolated symptom or following resolution of any other COVID‐19 symptoms.

Omega‐3 supplements

It is optional for a patient with LOS more than 2 weeks as an isolated symptom or following resolution of any other COVID‐19 symptoms.

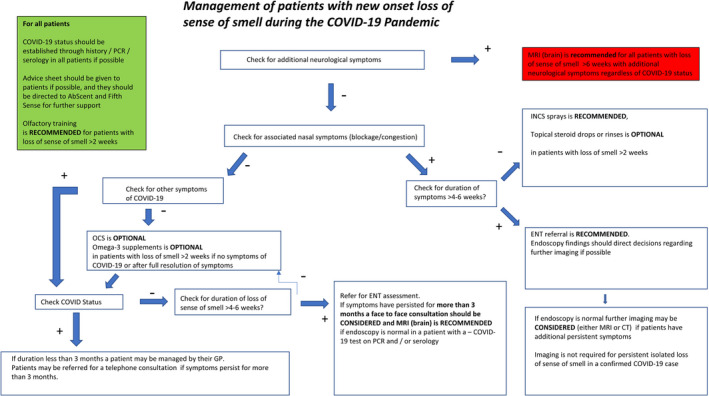

The flow chart (Figure 1) summarizes key points in relation to treatment, investigations and management of new onset loss of sense of smell during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart for management of new onset loss of sense of smell during the COVID‐19 pandemic. INCS, intranasal corticosteroids; OCS, oral corticosteroids. Optional indicates that consensus was achived at the 60% and not the 70% threshold, highlighting ongoing uncertainty regarding the usage

We therefore suggest that decisions regarding usage should be made at an individual patient level, considering the risks in view of comorbidities and individual patient preferences.

4. DISCUSSION

Post‐viral olfactory loss (PVOL) is one of the most common causes of olfactory dysfunction. Pathogens include those viruses causing the common cold comprising influenza‐, parainfluenza‐, rhino‐, and coronavirus. 5 Olfactory dysfunction can have a significant negative impact on quality of life. 6 COVID‐19 has been shown to be associated with a high prevalence of loss of sense of smell and taste, and early reports on recovery suggest that while this may be transient in many cases, resolving in 7‐14 days, at least 10% will have severe deficits lasting beyond the first 4‐6 weeks. 7 Longer‐term data are not yet available. Historical reports of spontaneous recovery following post‐viral loss likely exclude patients with transient loss due to under‐reporting, but instead capture those with loss persisting at least in beyond the first few weeks. Nevertheless, two retrospective studies, including 791 and 262 patients, respectively, indicate that between one third to two thirds of patients with PVOL will experience a clinically relevant improvement. 6 , 8 , 9 However, recovery can sometimes take several years. Given the high incidence of COVID‐19 it is anticipated that both primary care and ENT specialists will see a surge in patients seeking advice.

4.1. Clinical applicability

The applied RAND/UCLA methodology allowed for timely development of appropriateness criteria for the medical management, referral guidelines, endoscopy and strategies for imaging of patients with new onset loss of sense of smell. Indeed, time was the essence in this study as many doctors including general practitioners and ENT surgeons are expected to meet a significant number of patients with post‐COVID‐19 loss of sense of smell in the near future or in subsequent outbreaks. 8 The created flow chart should assist with overview and appropriate management. This methodology combined the best available evidence with the cooperative judgment of experts in the field.

4.2. Key findings and comparison with the existing literature

There exists solid evidence for the use of olfactory training in the treatment of PVOL. 5 , 6 , 7 Smell training is also recommended by the expert panel in this study for the management of new onset loss of sense of smell during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Many different medications have been proposed to treat PVOL, including oral corticosteroids, topical corticosteroids, zinc sulphate, alpha lipoic acid, theophylline, caroverine, vitamin A, Ginkgo biloba, sodium citrate and minocycline. However, the evidence to support use of these medical treatments for PVOL is limited and no large randomized controlled trials (RCT) exist. The expert panel only recommended use of INCS in patients with loss of sense of smell and concomitant nasal symptoms and made recommendations against the use of alpha lipoic acid.

We were unable to reach consensus at the 70% threshold determined a priori but did achieve consensus at a 60% threshold for 3 treatments; topical steroid rinses, omega‐3 supplements and oral corticosteroids (but only if no symptoms of COVID‐19 or after full resolution of symptoms). We did agree that these could be considered as optional medical treatments, but after discussion with patients regarding the uncertainty surrounding usage and assessment of risks at an individual level.

Delivery of ENT care will be challenging as we undertake a graduated return to elective practice. In particular, use of nasal endoscopy needs to be carefully considered due to its potential to be an aerosol generating procedure. Waiting times for ENT care will likely significantly increase. For many patients with confirmed COVID‐19 infection and loss of sense of smell, specialist review and further investigation will not be required; however, serology testing will be required for those who had been unable to access testing at the time of active infection. We have identified those who will benefit from specialist review, and also provided supporting material to assist primary care doctors, who may have had quite limited experience in this area. We plan to develop further educational material for both GP’s and ENT surgeons. Patient groups including AbScent and Fifth Sense will play an important role in patient support, we are delighted to be partnering with both groups to provide patient information leaflets (Appendix S3) and further support through a variety of different media.

4.3. Strengths and limitations of the study

The strength of the method was to give each panellist an equal voice in the Delphi process, and maintaining anonymity throughout the scoring process. The methodology is also ideally suited to the social distancing requirements of the current pandemic in place of nominal group techniques where face‐to‐face discussion is required. A limitation is that the guidelines are based on the panellist's interpretation of the best available evidence and may be influenced by their own training and clinical experience. Another limitation may be the group composition as it is generally recommended that the group is multidisciplinary 10 ; it would have benefited from the inclusion of both primary care doctors and patient representatives.

Limitations of the study are that the evidence base considered is not specific to COVID‐19. There is a risk that bias could be introduced in the evidence summaries produced, but in order to minimise this the systematic reviews upon which these were based were circulated in full. Some treatments that are shown to be ineffective in the systematic reviews were not considered, and others were excluded if they were not available in the UK or safe to administer during a time of restricted access to health care (eg iv infusions, or treatments needing regular monitoring of blood levels); however, these may be available in other settings outside of the UK and as this decision was not made as part of the Delphi process it may have introduced a potential source of bias.

We make no treatment recommendations for loss of less than 2 weeks – in part as many patients show rapid improvement and treatment may not be required, but patients may still seek advice and support from patient groups and there would be no harm in starting smell training at an earlier point should they wish to do so.

Recommendations may need to change in the face of new evidence. We originally included a suggestion that patients with unknown COVID‐19 status should have serology testing, but more recent evidence showing limitations with both false positive and false negative results. 11 Furthermore, recent evidence has shown that antibody levels decline by 70% during convalescence, such that in mild cases such that 12% who initially sero‐converted did not have detectable antibodies at 8 weeks. 12 As antibody testing is not yet widely available in the UK and this delay will further affect the value of serological testing, we have removed this recommendation.

Finally, the term ‘loss of sense of smell’ was used in the clinical scenarios, and the panel were not asked to consider differing severity of loss. Unpublished studies show very high rates of recovery in those with mild to moderate loss at the onset of olfactory dysfunction, but these guidelines could be applied in these cases as well as patients with complete loss of smell. Future updates may consider complete and partial loss separately.

4.4. Perspectives and areas for future research

We look forward to a time when the COVID‐19 pandemic will pass – and these guidelines no longer be needed. They have been developed for a time when the prevalence of COVID‐19 related loss of smell is high, but they will need to be reconsidered when the relative likelihoods of differential diagnoses increase—particularly with regard to indications for further imaging. Although considered with regard to COVID‐19 related loss of sense of smell, the recommendations on treatments may be applied to all post‐viral loss of sense of smell, although the risk – benefit analysis may need to be modified. Finally, it should be noted that as our experience of COVID‐19 grows, our guideline will likely need to evolve. We hope that the newfound spotlight on loss of sense of smell and taste will drive clinical research and lead to the development of novel treatment options for patients with post‐viral loss, and that greater understanding exists for those who do not recover.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors report no conflicts of interest in relation to this publication. There exists no competing financial interest.

Supporting information

Appendix S1

Appendix S2

Appendix S3

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None.

Hopkins C, Alanin M, Philpott C, et al. Management of new onset loss of sense of smell during the COVID‐19 pandemic ‐ BRS Consensus Guidelines. Clin Otolaryngol. 2021;46:16–22. 10.1111/coa.13636

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data generated and analysed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Spinato G, Fabbris C, Polesel J, et al. Alterations in smell or taste in mildly symptomatic outpatients With SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. JAMA. 2020;323:2089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lechien JR, Chiesa‐Estomba CM, Place S, et al. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of 1,420 European patients with mild‐to‐moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J Intern Med. 2020;288(3):335‐344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Menni C, Valdes AM, Freidin MB, et al. Real‐time tracking of self‐reported symptoms to predict potential COVID‐19. Nat Med. 2020;26:1037‐1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Borsetto D, Hopkins C, Philips V, et al. Self‐reported alteration of sense of smell or taste in patients with COVID‐19: a systematic review and meta‐analysis on 3563 patients. Rhinology. 2020. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hummel T, Whitcroft KL, Andrews P, et al. Position paper on olfactory dysfunction. Rhinology. 2016;56(1):1‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cavazzana A, Larsson M, Munch M, Hahner A, Hummel T. Postinfectious olfactory loss: a retrospective study on 791 patients. Laryngoscope. 2018;128(1):10‐15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hopkins C, Surda P, Whitehead E, Kumar BN. Early recovery following new onset loss of sense of smell during the COVID‐19 pandemic ‐ an observational cohort study. Journal of otolaryngology ‐ head & neck surgery = Le Journal d'oto‐rhino‐laryngologie et de chirurgie cervico‐faciale. 2020;49(1):26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reden J, Mueller A, Mueller C, et al. Recovery of olfactory function following closed head injury or infections of the upper respiratory tract. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132(3):265‐269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Duncan HJ, Seiden AM. Long‐term follow‐up of olfactory loss secondary to head trauma and upper respiratory tract infection. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121(10):1183‐1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fraser GM, Pilpel D, Kosecoff J, Brook RH. Effect of panel composition on appropriateness ratings. Int J Qual Health Care. 1994;6(3):251‐255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, Takwoingi Y, et al. Antibody tests for identification of current and past infection with SARS‐CoV‐2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;6:CD013652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Long QX, Tang XJ, Shi QL, et al. Clinical and immunological assessment of asymptomatic SARS‐CoV‐2 infections. Nat Med. 2020;26:1200‐1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1

Appendix S2

Appendix S3

Data Availability Statement

The data generated and analysed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.