In this multicenter study, interviews with parents of children with cancer revealed evidence for 8 communication functions; these communication functions manifested in the context of building relationships.

Abstract

Video Abstract

BACKGROUND:

When children are seriously ill, parents rely on communication with their clinicians. However, in previous research, researchers have not defined how this communication should function in pediatric oncology. We aimed to identify these communication functions from parental perspectives.

METHODS:

Semistructured interviews with 78 parents of children with cancer from 3 academic medical centers at 1 of 3 time points: treatment, survivorship, or bereavement. We analyzed interview transcripts using inductive and deductive coding.

RESULTS:

We identified 8 distinct functions of communication in pediatric oncology. Six of these functions are similar to previous findings from adult oncology: (1) building relationships, (2) exchanging information, (3) enabling family self-management, (4) making decisions, (5) managing uncertainty, and (6) responding to emotions. We also identified 2 functions not previously described in the adult literature: (7) providing validation and (8) supporting hope. Supporting hope manifested as emphasizing the positives, avoiding false hopes, demonstrating the intent to cure, and redirecting toward hope beyond survival. Validation manifested as reinforcing “good parenting” beliefs, empowering parents as partners and advocates, and validating concerns. Although all functions seemed to interact, building relationships appeared to provide a relational context in which all other interpersonal communication occurred.

CONCLUSIONS:

Parent interviews provided evidence for 8 distinct communication functions in pediatric oncology. Clinicians can use this framework to better understand and fulfill the communication needs of parents whose children have serious illness. Future work should be focused on measuring whether clinical teams are fulfilling these functions in various settings and developing interventions targeting these functions.

What’s Known on This Subject:

When a child is seriously ill, high-quality communication has been associated with parental peace of mind, hopefulness, greater trust in physicians, and feelings of acknowledgment and comfort. However, in no studies have researchers sought to identify communication functions in pediatric oncology.

What This Study Adds:

Interviews with parents of children with cancer revealed evidence for 8 distinct functions of communication. Clinicians can use this model to better understand and fulfill the communication needs of parents. Additionally, this model can inform development of robust measures and communication interventions.

In pediatric oncology, reports of “high-quality” communication have been associated with parental peace of mind,1 hopefulness,2,3 greater trust in physicians,4,5 and feelings of acknowledgment6 and comfort.7 Similarly, parents report feeling better prepared for self-management8 and decision-making9 when clinicians provide “high-quality” information. Although these studies have provided important insights into current communication practices, they have not explored or identified how communication is actually functioning in these clinician-family relationships. An understanding of the unique functions of communication is needed to guide the development of communication measures and interventions in the future.

In adult oncology, the report from a National Cancer Institute consortium proposed a functional model of communication between clinicians and adult oncology patients, which was focused on outcomes of unique communication interactions rather than the specific processes of communication.10,11 Such a model is consistent with the “equifinality nature of communication,” meaning that multiple approaches and patterns of communication can achieve the same outcomes.10 In the report, 6 core functions of communication were identified: exchanging information, making decisions, fostering healing relationships, enabling self-management, managing uncertainty, and responding to emotions.11 The authors proposed that these functions were interdependent and supported patient-centered care. In a preliminary study, using published narratives, we previously explored whether this functional communication model applies to pediatrics, finding evidence of unique functions in the pediatric context.12 Beyond this work, in no studies have researchers sought to identify the functions of communication in pediatric oncology.

To improve communication, we need to know how it functions, how to measure it, and what aspects of communication to target with interventions. In this multicenter qualitative study, we aimed to identify the functions of communication in pediatric oncology from parental perspectives. Given the unique emotional and social contexts of pediatrics, we hypothesized that communication in pediatric oncology would have functions not represented in adult oncology.

Methods

We report this study following Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research guidelines.13

Participants and Recruitment

We interviewed parents of children with cancer from Washington University School of Medicine (St Louis, MO), St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (Memphis, TN), and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (Boston, MA) between October 2018 and March 2020. We employed stratified sampling with the following strata, aiming for 12 to 15 parents per stratum14: time point (treatment ≥1 month, survivorship ≥6 months, or bereavement ≥6 months), child’s age at diagnosis (≤12 or ≥13 years), and study site. Parents were eligible if they (1) were most involved in communication with clinicians; (2) had a child with cancer younger than 18 years at the time of enrollment or child’s death; (3) spoke English. We focused on the parent most involved in communication to ensure parents had meaningful communication experiences to relate. We excluded participants who had clinical relationships with any authors. We recruited participants via telephone, mail, and in person. Institutional review boards at all sites approved this study.

Data Collection

We conducted semistructured telephone interviews using an interview guide informed by our previous work12,15,16 and 2 pilot interviews (Supplemental Information). All interviews were conducted by 1 of 2 authors (B.A.S. and L.J.B.). Both were clinical fellows with qualitative research training. Interviews were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed.

Data Analysis

We used thematic analysis,17 employing Epstein and Street’s11 functional communication model as an a priori framework but remained open to novel functions. In consultation with all authors, 2 authors (B.A.S. and L.J.B.) developed a codebook for communication functions through iterative consensus coding of 26 transcripts. We defined “communication functions” as processes within communication interactions that achieve important goals for parents. We reached thematic saturation for communication functions after consensus coding 16 transcripts (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Codebook for Communication Functions in Pediatric Oncology

| Communication Function | Definition |

|---|---|

| Building relationships | Healing relationships provide emotional support, guidance, and understanding. Such relationships are built on trust, rapport, and mutual understanding of each other’s roles and responsibilities. Clinicians can facilitate a healing relationship by engaging in partnership building, eliciting goals and values of the patient and family, and displaying warmth and empathy in communication. |

| Exchanging information | Parents seek information about the cause, diagnosis, treatment, prognosis, and lasting effects of cancer and its treatment. Fulfilling information needs not only helps families to gain important knowledge about a child’s illness but also aids the development of a strong clinician-family relationship and supports decision-making, among other outcomes. Patients and families also have information that they want to share with clinicians, so exchanging information seeks a bidirectional understanding between clinicians and families. |

| Enabling family self-management | Parents must manage complex medical, logistic, and emotional challenges within their families. Communication that enables parents to address these ongoing challenges can support family self-management. |

| Providing validation | Many parents doubt their quality as a parent or feel a sense of guilt or shame when their child has cancer. Effective communication can validate the current experiences and concerns of the parent while also reaffirming their role in the treatment of their child. |

| Managing uncertainty | Parents and patients experience many types of uncertainty after a diagnosis of cancer. This uncertainty can pertain to prognosis, side effects, frequency of hospitalization, and long-term effects, among others. Family-centered communication should help to communicate clinical uncertainty when it exists, dispel uncertainty when there is an answer, and help patients and families manage unavoidable uncertainties. Parents and patients also identify uncertainties about possible future outcomes and communicate bidirectionally with clinicians to obtain anticipatory guidance for these uncertainties. |

| Responding to emotions | Parents can experience a range of emotions, including fear, sadness, anger, anxiety, and depression. Effective communication can respond to emotions that are apparent or anticipate emotional responses likely to develop. |

| Supporting hope | Hope is essential for parents as they live with the terrifying possibility that their child might die or have significant impairments because of cancer or its treatment. Effective communication can bolster a parent’s sense of hope. |

| Making decisions | Effective decision-making requires effective communication. Such communication can support decision-making in a number of ways: raising the clinician’s awareness of the family’s needs, values, and fears; clarifying clinical reasoning and treatment options; and alerting the clinician to the family’s preferred role in decision-making. At other times, decisions might be presented by the clinician as strong recommendations. |

We define communication functions as processes within communication interactions that achieve important goals for parents.

Two authors (B.A.S. and A.B.F.) subsequently coded all transcripts using Dedoose qualitative software. These authors initially consensus-coded transcripts for training purposes and then coded independently and established interrater reliability using the Dedoose training center at 4 time points, achieving κ scores ranging from 0.79 to 0.96.

Results

Parent Characteristics

We interviewed 78 parents, with interviews ranging from 24 to 108 minutes (Table 2). Parents were predominantly white (91%) and female (85%). The diagnoses were leukemia or lymphoma (45%), solid tumors (38%), and brain tumors (17%) (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Distribution of Sampling for Parent Interviews

| Treatment | Survivorship | Bereavement | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≤12 y | |||

| St Louis | 7 | 4 | 8 |

| Boston | 9 | 8 | 1 |

| Memphis | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| Age ≥13 y | |||

| St Louis | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Boston | 3 | 5 | 1 |

| Memphis | 4 | 3 | 3 |

Each cell indicates the number of parents recruited from each academic center.

TABLE 3.

Patient and Parent Characteristics (N = 78)

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Parent age, y | |

| 21–29 | 4 (5) |

| 30–39 | 25 (32) |

| 40–49 | 30 (39) |

| ≥50 | 19 (24) |

| Parent sex | |

| Female | 66 (85) |

| Male | 12 (15) |

| Relation to child | |

| Parent | 77 (99) |

| Grandparent | 1 (1) |

| Parent race and/or ethnicitya | |

| White | 68 (91) |

| Black | 7 (9) |

| Asian American | 2 (3) |

| Hispanic | 2 (3) |

| Other | 1 (1) |

| Parent education | |

| High school graduate or less | 7 (9) |

| Some college or technical school | 15 (19) |

| College or technical school graduate | 36 (46) |

| Graduate or professional school | 20 (26) |

| Parent marital status | |

| Married and/or living as married | 61 (78) |

| Other | 17 (22) |

| Child age at diagnosis, y | |

| ≤12 | 51 (65) |

| ≥13 | 27 (35) |

| Child sex | |

| Male | 41 (53) |

| Female | 37 (47) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Leukemia or lymphoma | 35 (45) |

| Solid tumor (not in brain) | 30 (38) |

| Brain tumor | 13 (17) |

| Time point in cancer trajectory | |

| Treatment | 30 (38) |

| Survivorship | 27 (35) |

| Bereavement | 21 (27) |

| Site | |

| St Louis | 27 (35) |

| Boston | 27 (35) |

| Memphis | 24 (30) |

Not mutually exclusive.

Communication Functions

We identified 8 communication functions. Two functions (supporting hope and providing validation) were not previously identified in the adult oncology literature.

Building Relationships

“Building relationships” was identified in every transcript and manifested as demonstrating clinical competence, reliability, care, and concern; advocating; engendering solidarity; and maintaining open and reassuring nonverbal communication (Table 4). Clinicians demonstrated clinical competence and reliability by addressing medical problems swiftly and thoroughly, remaining available to parents, projecting confidence, advocating for the family, and having the child’s best interests at heart: for example, “We just felt safe and reassured by the way that they projected how they were going to take care of him. At no time did we worry that they were not gonna do everything in their powers to make sure that he was safe at all times” (father, treatment). Parents often linked the concepts of reliability and competence: for example, “For the most part, at least in the cancer treatment, we got a response in less than 24 hours, which just lets you know that they’re on top of it, and they’re listening, and they’re problem solving” (mother, survivorship).

TABLE 4.

Operationalizations of Communication Functions

| Communication Function | Operationalization of Function |

|---|---|

| Building relationships | |

| Demonstrating clinical competence and reliability: “She knows everything. You can say we’re doing this, this, and this. This is our symptoms. She’s like, ‘All right. Well, I’m gonna run this test, this test, and this test. Let me get blood.’ She just knows everything. [Nurse] is amazing” (mother, treatment). | |

| Demonstrating care and concern: “Well, the family feel, it really makes you feel like an individual, not a number, not just a patient, which I think it’s easy to get lost, but I think the family feel makes you just feel safe, secure, and just loved, I guess, I don’t know” (mother, survivorship). | |

| Advocating: “I think the [palliative care] team was probably who was with us during those meetings. It was nice to have somebody that I had known from previous experiences was gonna be on my side, no matter what I was thinking. They were going to be that person who was my advocate. I really appreciated that. Being in those meetings is terrifying. You’re not entirely sure of what’s going on, and you have that person who does know what’s going on, and they know how you feel about it. They can be that bridge between the parents and the doctors not quite understanding each other” (mother, bereavement). | |

| Engendering solidarity: “I think one of the best things is they brought us to [clinic] to have our meetings and to sit down with our team so that even though at the time it seems super overwhelming. We could at least see that we weren’t alone. We could see dozens and dozens of other kids and their families there with cancer. That made my husband feel a lot better. He actually felt like we weren’t alone anymore and he told me that. That was something that they did really well on the diagnosis” (mother, treatment). | |

| Using an open and reassuring tone and nonverbal communication: “Nonverbal communication plays a large role in that too. If you look disinterested or perturbed, or as if it’s above you to have to answer such questions, that’s all poor communication” (mother, treatment). | |

| Exchanging information | |

| Offering consistent, accurate, and timely information: “Well, I mean, they always communicated well—it seemed—after MRIs. Although, sometimes I had to wait too long—I thought—for results” (mother, bereavement). | |

| Engaging in bidirectional information exchange: “They would always come in and just ask how she was doing, how her appetite was, always get a weight, how her activity level was, if she was having any new pains or anything. They would always discuss the lab values, always make sure she wasn’t having any signs of infection, latent signs, where they couldn't really pick up on it right away, something like that” (father, bereavement). | |

| Explaining rationale for medical care: “No. The biggest thing really is communication, just letting me know where their thinking is heading or what’s important that needs to be done. That’s really always been the most important thing. I like to be kept in the loop” (mother, treatment). | |

| Meeting individual’s unique information needs: “Anything and everything. They were really good about—they always gave us information, as far as scan results and things like that. They were always very straight and to the point because they—and they asked us at the beginning, how do you want us to approach this? Do you want [patient] to know everything? Do you just want to know, and then you tell her?” (mother, bereavement). | |

| Providing understandable information and checking for understanding: “They always call us after procedures. They call us to make sure he's doing okay. They come in and do our paperwork, one on one with us. It's not just you get handed discharge papers. They sit down, they talk to you about it. They make sure you understand” (mother, treatment). | |

| Offering transparent disclosure of difficult news: “Well, things you didn’t want the answer to. Right? It was a tough situation. It was a very hard situation. I feel like they were always very easy to talk to even about the tough decisions that we had to make. There were two bad situations. The initial diagnosis was awful. Right? In the first couple appointments as we found out what was going on were really, really hard” (father, survivorship). | |

| Enabling family self-management | |

| Providing anticipatory guidance and planning in advance: “Just their overall plan of getting her better. They were looking at long-term and spreading out the goal instead of just today. They would tell us today we’re gonna do this, tomorrow we’re gonna do this and the next day we’ll do this, so we kinda knew what to look forward to” (mother, treatment). | |

| Training in technical skills: “They were very good at explaining to us what we needed to monitor, and I think we’re also pretty good at making sure we knew everything. We knew what we had to monitor ‘cause we didn’t know what we were dealing with” (mother, survivorship). | |

| Identifying needs and directing toward resources: “To just listen to the family and offer support, offer ways that they can get some respite or help with this, either psychological—‘cause it’s very stressful—or respite care, like somebody to help out—give a hand when the work is hard. Luckily, I have a husband, but some families don’t. It’s just a mom or a dad. They don’t have a spouse to rely on. That’s what I would say is just tell them ways that they can get help. Make things easier for them” (mother, bereavement). | |

| Providing guidance during acute illness: “I would call about small concerns like that. Here, recently, I’ve had to start calling the [clinic], ‘Hey, we have a fever of this,’ and they would give us instructions to ‘Check it 30 minutes later,’ or ‘Go ahead and head this way; we’re waiting on you’” (mother, treatment). | |

| Providing validation | |

| Empowering parents as partner and advocate: “I would say that it was very clear from the beginning as well, especially with my wife, that it was acceptable to be an active part of the team. In fact, it was potentially going to be very necessary that we be strong advocates. That was great to hear. I think if all parents hopefully hear something like that, it’s true. I think that that’s a great thing” (father, survivorship). | |

| Reinforcing good parenting beliefs: “They said it previously as well, but, in those moments, that meant a lot to hear because, yes, my daughter is dying, but the communication said, ‘But as her mom, as her caregiver, from your point of view, you've done a really good job’” (mother, bereavement). | |

| Validating concerns: “Just understanding, listening to things, and being listened to in that way, even if they were going to do the same thing, no matter what, knowing that they did hear what you had to say and your concerns and address them” (mother, bereavement). | |

| Managing uncertainty | |

| Exploring unknowns and/or developing contingency plans: “So, to me, ‘being comforting’ is part of that being reassuring of the information you’re delivering, the experience that that team has with this particular condition…and then understanding and acknowledging that fact that we’re in unchartered territory and it’s okay that we don’t understand things” (mother, treatment). | |

| Making educated guesses based on evidence: “I would wanna know like, hey, in these particular types of cancer, in this particular situation where there was a similar thing that happened where the margins weren't cleaned, and this is what we did. Like what, what does that actually end up? How did that end up working out? Getting that kind of information, maybe. But what I’m always told is, ‘Every case is different. We could tell you a bunch of statistics, but what really matters is your daughter's case’” (mother, treatment). | |

| Reassuring with presence, close follow-up, tests, or procedures: “In terms of doing a blood test, see if any of her markers have changed, they’ve just responded immediately. It’s given me kind of a peace of mind throughout this whole process. If the results are good, then I know that probably it’s okay and I shouldn’t worry as much as I worry. It’s made the whole thing a little bit easier” (mother, treatment). | |

| Responding to emotions | |

| Anticipating emotional needs: “They always came in and checked up on us just to make sure we were okay. One of the nurses, “Hey, do you need to go take a shower? Go take a break for a minute.” She didn’t have to do that on her lunch break, but she gave me a minute to go and do that. It was beyond grateful for what they did. They did above and beyond to help me and my family” (mother, survivorship). | |

| Recognizing and adapting to emotions: “Some of ‘em maybe kinda cried with us a little bit. They would actually sit there and talk to us. Even after the fact, we would get calls from ‘em just regularly just to check up on her and calls from random people at the hospital to see how we were doing as well and stuff like that” (father, bereavement). | |

| Supporting hope | |

| Emphasizing the positives: “Then you put your child through those things, but you’re hopeful. They were very good at assuring us that ‘Everybody’s bodies are slightly different. This could be that one-in-a-million chance’” (mother, bereavement). | |

| Demonstrating intent to treat and/or cure: “Just kind of, I guess, not necessarily relax, but just feel like she was well taken care of and that we’re just gonna figure out what to do next. It made me feel like they were trying, they were actually trying to put her care and her future—make it the best as possible, from what they can do” (mother, treatment). | |

| Avoiding false hopes: “Yeah. Don’t sugarcoat it. Don't make — I mean, don’t — obviously, don't just tell something bad, but we need to know what to be prepared for. We need to know what to watch for on the bad parts” (mother, treatment). | |

| Redirecting toward hopes in addition to survival: “[The doctor] said, ‘The tumors are all over the ventricles. It’s down here. It’s in the brainstem.’ I said, ‘You have to give me something like [other doctor] does, something hopeful.’ He said, ‘Well, look at him. He’s walking around. He’s going to school. That’s what you need to hold onto.’ I said, ‘Okay.’ Live every day” (mother, bereavement). | |

| Making decisions | |

| Involving parents in the decision-making process: “They always made it clear that it was totally our choice, whatever we chose to do. It was very reassuring. Just the way that they spoke to us, it was—we felt really secure in putting him or placing him in the trial and just, overall, in general, felt really good about how hard everyone was going to work on his treatment” (father, treatment). | |

| Offering opinions: “If this was your child, I think I asked her that once. If this was yours, what would you do? She was, well, I would pick this one. Yeah” (mother, bereavement). | |

| Providing strong recommendations: “It didn’t seem like I had much choice in what was going on. It was, ‘Well, this seems to have worked or helped, and we’re gonna go with this.’ It didn’t seem like we really had much choice. It was important that they explain all that” (mother, bereavement). |

We define operationalization as the ways in which each function manifests in clinical encounters.

Medical errors and inaccurate communication had a negative effect on this relationship, and parents expressed the importance of acknowledging mistakes. Clinical teams also demonstrated competence by having seamless communication within their team and with other specialists.

Clinicians demonstrated care and concern by showing empathy, compassion, and kindness, creating a “family-like feel,” engaging the child, and creating a “positive atmosphere.” After a child died, clinicians also showed their compassion by remembering the child and attending funerals.

Parents also identified the importance of the clinician advocating for them or their child. This took the form of problem solving and taking additional steps on behalf of the family: for example, “We also had some nurses that were fierce advocates for us too… They were just always very willing to help, again, put us in a position where [patient] was receiving the highest level of care that he could possibility receive” (father, bereavement). Clinicians engendered solidarity by reminding parents that they were not alone in their journey, they were part of a larger team, and many other parents had experienced similar situations in the past: “It does help when you realize that this isn't just a struggle that you’re going through alone. There are other people that can empathize with you and understand the path that you’ve taken and the hardships that you’ve dealt with” (father, bereavement). Lastly, many parents identified the importance of open and reassuring nonverbal cues, such as sitting, making eye contact, smiling, and maintaining an open posture: “She was always again, very caring and she would come in and she would sit down. She wouldn’t just stand at the bedside” (mother, bereavement).

Exchanging Information

“Exchanging information” was identified in every transcript and manifested as providing consistent, accurate, and timely information; explaining the rationale for recommendations; meeting unique information needs; providing understandable information; and transparently disclosing difficult information. Additionally, several parents noted that clinicians engaged in bidirectional information exchange by seeking information from them about their child’s wellbeing (Table 4). Nearly all parents commented on the importance of consistent, accurate, and timely information that is understandable. Parents also highlighted the importance of meeting their unique information needs, especially related to the level of detail, pacing of information, and setting of the conversation.

Interestingly, some parents desired transparent disclosure of difficult news, although others preferred these conversations to be tempered or delayed. One parent commented, “His doctor, his fellow, his nurse practitioner, his nurses, right down the line, I felt like, didn’t sugarcoat anything. That was very, very important to me” (mother, survivorship). Yet, another parent commented, “I had asked her to be honest with me; but let her know that my husband did not want to hear things. Let me know first and then I’ll talk with him and then we can kind of go from there” (mother, bereavement).

Enabling Family Self-management

“Enabling family self-management” was identified in 75 of 78 transcripts (28 of 30 active treatment, 27 of 27 survivorship, and 20 of 21 bereavement) and manifested as providing anticipatory guidance, training in technical skills, identifying needs and directing toward resources, and providing guidance during acute illness (Table 4). Many parents noted the importance of knowing what to expect: “I know that helped with me having a clear-cut diagnosis and a clear-cut plan of okay, this is what we’re gonna do” (mother, bereavement). Some parents noted the need for training in technical skills to care for their child. When children were acutely ill, clinicians also supported families by providing medical guidance.

Additionally, clinicians supported self-management by identifying needs and directing toward resources: “They hooked me up with resources, a psychosocial clinician right away for support. If you need any religious support, they hook you up with that as well right away, make sure you feel welcome and that you’re important.” (mother, survivorship).

Providing Validation

“Providing validation” was identified in 65 of 78 transcripts (25 of 30 active treatment, 23 of 27 survivorship, and 17 of 21 bereavement) and manifested as empowering parents as partners, reinforcing “good parenting” beliefs, and validating concerns (Table 4). Many parents noted the importance of being empowered: “It made you feel like you were a team with the doctors and you’re working together to help your child go through this. It was not like you were just told what to do. It was a team effort” (mother, survivorship). Parents also described the importance of having their concerns taken seriously: “There was another resident physician that, again, completely ignored my concerns. This is when we were inpatient… I was like, ‘Please listen to me’” (mother, treatment). Lastly, parents felt validated when clinicians reinforced their “good parent” beliefs: “I blamed myself because I thought maybe I could have caught it earlier before the tumor was so large. I felt like a bad mom because I didn’t. Hearing that [I wasn’t] made me feel better” (mother, treatment).

Managing Uncertainty

“Managing uncertainty” was identified in 59 of 78 transcripts (24 of 30 active treatment, 23 of 27 survivorship, and 12 of 21 bereavement) and manifested as exploring unknowns, making educated guesses, and providing reassurance (Table 4). Parental uncertainty mostly pertained to prognosis, side effects, logistics, and long-term effects. When faced with uncertainty, many parents wanted clinicians to explore these unknowns and develop contingency plans: “They were honest. They were like, ‘Well, we don’t know. We don’t know if this is gonna work, but we’re gonna try to—we’re gonna do this and then as we see the result that it’s not working, then we’re gonna change it to something else that might work’” (mother, survivorship).

Clinicians sometimes offered guesses when facing uncertainty, which was sometimes helpful: “Our joke throughout our whole treatment process was, “There’s no crystal ball.” You don’t know what’s going to happen. You don’t know exactly how this patient might react to X, Y, and Z. If you can take the time to just sit with a family for even 5 minutes and say, ‘This is typically what we see,’ or ‘This is what we’re expecting of your child’ (mother, survivorship). At other times, guesses were frustrating: “I think a lot of it is when they guess and they don’t actually know and they kinda give you their educated guess, but it turns out that it’s completely wrong” (mother, treatment). To reassure parents, some clinicians promised close follow-up or additional testing.

Responding to Emotions

“Responding to emotions” was identified in 55 of 78 transcripts (23 of 30 active treatment, 16 of 27 survivorship, and 16 of 21 bereavement) and manifested as anticipating emotional needs and recognizing and/or adapting to emotions (Table 4). Some parents advised clinicians to provide support in anticipation of emotional needs: “Hopefully, [clinicians] understand how gut wrenching and life changing that conversation is gonna be... Understanding that you give them this info, and it is like they just got pushed off a cliff. Making sure that they have support” (mother, bereavement). Parents also described how clinicians reacted to their emotional state: “I think she picked up on definitely body language, me crossing my arms and just looking into space because I would just start to tune out or me physically just crying and so she would stop and say, ‘We’ll take a break now and give you a few minutes’” (mother, bereavement).

Supporting Hope

“Supporting hope” was identified in 47 of 78 transcripts (16 of 30 active treatment, 18 of 27 survivorship, and 13 of 21 bereavement) and manifested as emphasizing positives, demonstrating curative intent, avoiding false hopes, and redirecting toward hopes other than survival (Table 4). Many parents expressed that hope was essential for their coping and wellbeing, but they varied in their preferences for how clinicians should support hope. Some parents preferred clinicians to emphasize positives: “[Our doctor] would always tell us what was going on, but then he’d always tell us something positive. That meant a lot to me, because I don’t always wanna hear all the bad things. Then he’d put something on the end that was positive, and I could take that with me. I could take that hope and live for the next week” (mother, bereavement). For some parents, clinicians supported hope by expressing an intention to cure their child, even if curing was unlikely. Contrarily, other parents emphasized the importance of avoiding false hopes: “I need to be able to trust my child’s team to be honest with me, to be open. If I ask a question, I want the honest truth. I don’t want to just hear what you think I need to hear” (mother, bereavement).

Making Decisions

“Making decisions” was identified in 46 of 78 transcripts (13 of 30 active treatment, 18 of 27 survivorship, and 15 of 21 bereavement) and manifested as involving parents, offering opinions, and providing strong recommendations (Table 4). Many parents indicated a preference for involvement in decision-making and expressed frustration when they were not involved: “They just kind of come up with a plan and don’t ask. They ask afterwards how I feel about it and not incorporate right then and there. Do you feel like this is best? Obviously they’re the doctors, but it’s also my child” (mother, treatment). Parents often wanted the clinician’s opinion, asking what clinicians would choose for their own children: “[Saying] what they think would be the best way to go, especially viewing it as maybe being one of their own kids, is one of the things I did respect about the doctors” (father, bereavement). Other parents preferred their clinicians to provide strong recommendations: “There was things that I would’ve done if somebody would’ve said to me in a much more hardline sort of way, ‘This is what could happen. Yes, he may have more time than that, but he also may have a lot less time than that. This is what I recommend. You should probably talk to this person’” (mother, bereavement).

Central Role of Relationship

The strength of the clinician-family relationships provided the context in which other communication functions manifested. For example, trust emanating from this relationship affected decision-making: “We trusted the doctor that he would pick the best protocol of treatment for her, knowing her medical history and knowing her current history and just that he would pick what was best for her. We didn’t spend a lot of time just talking about different options or alternative options to the protocol for treatment that he selected for her” (mother, survivorship). Relationships also influenced hope: “It made me feel really, really good, ‘cause I knew she would be focused on our child. She just gave us so much hope” (mother, survivorship). Relationships even influenced information exchange because parents believed information if the clinician had credibility. We identified similar effects of relationships on all communication functions.

Discussion

In this multicenter study, we identified 8 communication functions in pediatric oncology. Together, these 8 functions represent the breadth of parental communication experiences during treatment, survivorship, and bereavement. Interestingly, 2 functions were not previously identified in the National Cancer Institute consortium monograph11: providing validation and supporting hope. We will focus our discussion on these 2 novel functions.

The identification of “providing validation” as a communication function reinforces the importance of clinicians validating “good parenting” beliefs.18–21 In previous work, parents have defined these “good parent” roles as making informed decisions, remaining at the child’s side, showing the child that he is loved, advocating for the child, and promoting the child’s health, among others.21 Fulfilling these roles is especially important if a child dies, when parents might regret past decisions or blame themselves for their child’s suffering.18 Our findings suggest that clinicians can support these “good parent” beliefs by acknowledging parental concerns and empowering parents as team members. For example, a clinician might ask the parent of a sick child, “What have you noticed at home? I know a lot about medicine and diseases, but you know more about your child than anybody.” Clinicians can also recognize how parents are fulfilling “good parenting” roles by reassuring parents that they have made informed, well-reasoned decisions guided by love for their child.

Our results also highlight the varying conceptions of hope that parents hold and the complexity of supporting hope. “Hope” is a term that has commonly been conflated with hope for a cure in the past, although a growing body of work has shown that parents often maintain several hopes simultaneously.20,22–26 Furthermore, some parents will “regoal” to focus on more appropriate or attainable hopes over time.27 Despite this growing complexity in the literature, most parents in our study mentioned hope in the context of survival. Few parents discussed hopes for other goals. Furthermore, although many parents identified hope as critically important, parents differed in their beliefs about how clinicians can support hope. Some parents desired optimism when facing dire news; others demanded stark facts so they could better prepare. Although past work has revealed that most parents want prognostic information,2,28–33 our findings highlight the difficulty of communicating prognosis in a way that meets each parent’s unique needs. To facilitate this process, clinicians should elicit communication preferences from families early and often throughout the child’s illness.

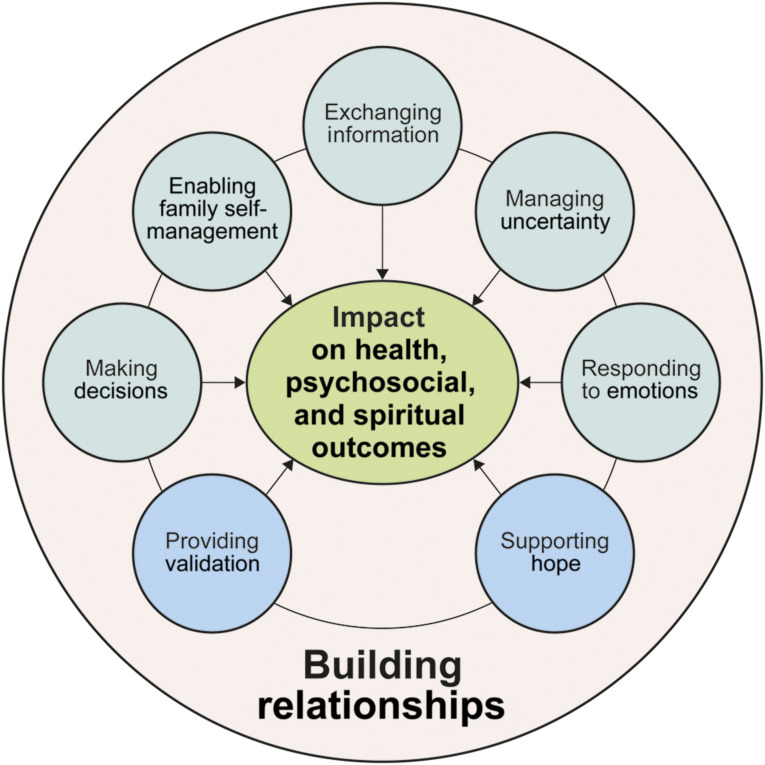

Lastly, our results suggest that “building relationships” provides a relational context in which all interpersonal communication occurs. As such, we propose a functional model of communication in which the nature of the clinician-parent relationship can either expand or limit the operationalization of other communication functions (Fig 1). For example, parents who trust in their clinician’s competence will likely believe information they receive, have confidence in medical decisions, and follow clinicians’ medical advice.34 Contrarily, clinicians will be less effective in responding to emotions, supporting hope, or providing validation if parents do not believe they care about their family. Furthermore, we propose that effective facilitation of these communication functions can have positive effects on health, psychosocial, and spiritual outcomes. However, in future studies, researchers will need to confirm the link between these outcomes and communication functions.

FIGURE 1.

Functional model of communication in pediatric oncology. In this model, we propose that all functions of interpersonal communication are affected by the strength of the clinician-family relationship. Furthermore, we hypothesize that facilitating these communication functions might have positive effects on health, psychosocial, and spiritual outcomes for the patient and family. Factors within green circles are similar to findings from past studies in adult oncology. Factors within blue circles were newly identified in this study.

This functional communication model might guide clinicians as they strive to support the communication needs of parents whose children have cancer; however, future studies are needed to verify these functions. We anticipate that this functional model can also be applied to other serious childhood illnesses. Our previous exploratory study of pediatric patient and parent narratives supported this conjecture,12 but further study is necessary in other childhood illnesses.

This model can also inform the development of future communication measures. In a recent review of communication interventions in pediatric and adult oncology, in 88 studies, researchers employed 188 different outcome measures, and 156 of these measures were only used in single studies.15 By developing and disseminating a robust measure based on this model, we could better compare outcomes across studies and truly know which interventions work.

Beyond measuring outcomes, our results could also inform the development of communication interventions, an area in which pediatrics lags behind adult oncology. In the previously mentioned review article, no studies specifically targeted communication in pediatric oncology.15 To support improvements in communication, this field needs to develop and test data-driven interventions in pediatric settings. Our findings can inform these interventions and help to fill this gap.

These results, however, should be interpreted in light of limitations. First, the parents were predominantly well-educated, white mothers. Also, children with brain tumors and older children were underrepresented. As such, our findings might not represent the experiences of all parents. Future studies should purposively sample to ensure more diverse representation. Additionally, we performed telephone interviews, and we might have missed parents’ nonverbal cues. Furthermore, parents might have been affected by recall bias or conformity bias. Lastly, we did not evaluate the perspectives of pediatric patients. This important question should be addressed in future studies.

Conclusions

Parental interviews revealed evidence for 8 communication functions in pediatric oncology. The strength of the clinician-family relationship seemed to affect the fulfillment of all functions. Clinicians can use this model to better understand and fulfill the communication needs of parents. Additionally, these findings can potentially be applied to other serious childhood illnesses, but this needs further study. Future work should be focused on measuring whether clinical teams are fulfilling these functions and developing communication interventions targeting these functions.

Footnotes

Dr Sisk participated in conceptualization, design, and implementation of the study, participated in formal analysis, and drafted the initial manuscript; Ms Friedrich and Dr Blazin participated in formal analysis; Drs Baker, Mack, and DuBois participated in the conceptualization and design of the study and formal analysis; and all authors reviewed and revised the manuscript, approved the final manuscript as submitted, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Funded by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (UL1 TR002345) and the Conquer Cancer Foundation of the American Society of Clinical Oncology Young Investigator Award. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Mack JW, Wolfe J, Cook EF, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Peace of mind and sense of purpose as core existential issues among parents of children with cancer. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(6):519–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mack JW, Wolfe J, Cook EF, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Hope and prognostic disclosure. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(35):5636–5642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nyborn JA, Olcese M, Nickerson T, Mack JW. “Don’t try to cover the sky with your hands”: parents’ experiences with prognosis communication about their children with advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(6):626–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El Malla H, Kreicbergs U, Steineck G, Wilderäng U, Elborai YES, Ylitalo N. Parental trust in health care--a prospective study from the Children’s Cancer Hospital in Egypt. Psychooncology. 2013;22(3):548–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.von Essen L, Enskär K, Skolin I. Important aspects of care and assistance for parents of children, 0-18 years of age, on or off treatment for cancer. Parent and nurse perceptions. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2001;5(4):254–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arabiat DH, Alqaissi NM, Hamdan-Mansour AM. Children’s knowledge of cancer diagnosis and treatment: Jordanian mothers’ perceptions and satisfaction with the process. Int Nurs Rev. 2011;58(4):443–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young B, Hill J, Gravenhorst K, Ward J, Eden T, Salmon P. Is communication guidance mistaken? Qualitative study of parent-oncologist communication in childhood cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(4):836–843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stinson JN, Sung L, Gupta A, et al. Disease self-management needs of adolescents with cancer: perspectives of adolescents with cancer and their parents and healthcare providers. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6(3):278–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mack JW, Wolfe J, Cook EF, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Parents’ roles in decision making for children with cancer in the first year of cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(15):2085–2090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Street RL Jr., Mazor KM, Arora NK. Assessing patient-centered communication in cancer care: measures for surveillance of communication outcomes. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(12):1198–1202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Epstein RM, Street RL Jr. Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering [NIH Publication No. 07-6225]. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sisk BA, Friedrich AB, Mozersky J, Walsh H, DuBois J. Core Functions of Communication in Pediatric Medicine: An Exploratory Analysis of Parent and Patient Narratives In: J Cancer Edu, vol. 35 2020:256–263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sisk BA, Schulz GL, Mack JW, Yaeger L, DuBois J. Communication interventions in adult and pediatric oncology: a scoping review and analysis of behavioral targets. PLoS One. 2019;14(8):e0221536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sisk BA, Mack JW, Ashworth R, DuBois J. Communication in pediatric oncology: state of the field and research agenda. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(1):e26727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Björk M, Sundler AJ, Hallström I, Hammarlund K. Like being covered in a wet and dark blanket - parents’ lived experiences of losing a child to cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2016;25:40–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feudtner C, Walter JK, Faerber JA, et al. Good-parent beliefs of parents of seriously ill children. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(1):39–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill DL, Faerber JA, Li Y, et al. Changes over time in good-parent beliefs among parents of children with serious illness: a two-year cohort study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;58(2):190–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hinds PS, Oakes LL, Hicks J, et al. “Trying to be a good parent” as defined by interviews with parents who made phase I, terminal care, and resuscitation decisions for their children. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(35):5979–5985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sisk BA, Kang TI, Mack JW. Sources of parental hope in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(6):e26981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hill DL, Nathanson PG, Fenderson RM, Carroll KW, Feudtner C. Parental concordance regarding problems and hopes for seriously ill children: a two-year cohort study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(5):911–918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hill DL, Nathanson PG, Carroll KW, Schall TE, Miller VA, Feudtner C. Changes in parental hopes for seriously ill children. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20173549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feudtner C, Carroll KW, Hexem KR, Silberman J, Kang TI, Kazak AE. Parental hopeful patterns of thinking, emotions, and pediatric palliative care decision making: a prospective cohort study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(9):831–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feudtner C. The breadth of hopes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(24):2306–2307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hill DL, Miller V, Walter JK, et al. Regoaling: a conceptual model of how parents of children with serious illness change medical care goals. BMC Palliat Care. 2014;13(1):9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mack JW, Cronin AM, Uno H, et al. Unrealistic parental expectations for cure in poor-prognosis childhood cancer. Cancer. 2020;126(2):416–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sisk BA, Kang TI, Mack JW. Prognostic disclosures over time: parental preferences and physician practices. Cancer. 2017;123(20):4031–4038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ilowite MF, Cronin AM, Kang TI, Mack JW. Disparities in prognosis communication among parents of children with cancer: the impact of race and ethnicity. Cancer. 2017;123(20):3995–4003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamihara J, Nyborn JA, Olcese ME, Nickerson T, Mack JW. Parental hope for children with advanced cancer. Pediatrics. 2015;135(5):868–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaye E, Mack JW. Parent perceptions of the quality of information received about a child’s cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(11):1896–1901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mack JW, Cook EF, Wolfe J, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Understanding of prognosis among parents of children with cancer: parental optimism and the parent-physician interaction. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(11):1357–1362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baker JN, Barfield R, Hinds PS, Kane JR. A process to facilitate decision making in pediatric stem cell transplantation: the individualized care planning and coordination model. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13(3):245–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]