Abstract

The COVID‐19 crisis is having a significant impact on the quality of life and future of young people; it can also lead to disruption in education. A disruption would pose a severe threat to the entire society in the postcrisis period. Therefore, educational institutions must respond quickly and ensure the continuity of the educational processes. Our research goal has been to develop and implement a model enabling a rapid transition from the traditional to the distance learning model in a state of emergency. Our focus has been on conceiving technical, organizational, and pedagogical changes that educational organizations need to implement to enable different interaction methods, ensure continuity, and provide high‐quality education. We have defined and implemented a model, which is described in detail in this paper, thus giving guidelines for a rapid transition to distance learning, which is not restricted to the crisis times only. We have evaluated our approach by monitoring the IT solutions and surveying students and teachers at the School of Computing, Union University of Belgrade. The results indicate the high satisfaction of these participants in the educational processes. They imply the acceptability of prolonged distance learning, if needed, and embrace the hybrid education model for the next generation of students.

Keywords: computer science education, crisis, distance learning, transition planning, virtual classroom

1. INTRODUCTION

The crisis caused by the appearance of the COVID‐19 virus is significantly affecting the future and quality of life of all the inhabitants of the planet, especially young people. Millions of people are infected and the rest of the people are in various forms of quarantine, to prevent further spread of the infection and reduce mortality rates [17]. Educational institutions must quickly adapt to the new situation and apply the distance education model, allowing remote access to computer infrastructure and resources. Disruption in the education of young people would be a significant threat to the quality of their lives in a postcrisis society. The uneducated and, it can be said freely, the "lost generation" would not be ready to renew economic, educational, and overall social flows at the end of the crisis.

Only the transition from the traditional to the distance learning model can enable the continuity of the educational process in partial or complete isolation. Information and communications technology (ICT) plays a crucial role, enabling the deployment of virtual classrooms, web‐based access to computer infrastructure in labs, virtual discussions, and other forms of teacher–student interaction [6, 48]. The speed of transition depends on the efficiency of the educational institutions' information system. Circumstances in which the education process takes place, the availability of resources, and the complete infrastructure of the educational institution, as well as the possibility of applying specific ICT solutions at students' location, impose the need to make a constructive adjustment immediately and precisely for every module, course, and program [5]. The student‐centric approach includes defining the goals for the knowledge and methods that should help students to acquire specific knowledge and develop appropriate skills.

This paper aims to introduce a model for a rapid transition from the traditional to distance learning model in a state of emergency. For this reason, our research focused on defining organizational and technical solutions and applying different interaction methods to ensure continuity and preserve the quality of teaching. We hypothesize that the results obtained during the evaluation phase will improve education in the postcrisis period.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides an overview of the research in the field of distance learning with a focus on transition in a crisis. In Section 3, we describe the proposed model of transition, with its implementation being elaborated in Section 4. Section 5 provides an evaluation of the proposed approach from an educational and technical standpoint. Section 6 concludes the paper, summarizing the main contributions.

2. RELATED WORK

2.1. Transition to online learning

Online learning is becoming an integral part of the secondary and high education process. Leading universities have indicated that online learning is critical to their long‐term growth and reported that the increase in demand for online courses or programs was higher than that for the face‐to‐face mode [28] long before the crisis. A substantial classification of online courses separates asynchronous from synchronous courses. Asynchronous courses provide students with a flexible environment that is self‐paced [51], which means that students can access the recorded multimedia course content when it is most convenient for them. The asynchronous courses can facilitate modern learning paradigms, for example, flipped classroom [54]. Whereas convenience is the most cited reason for satisfaction, the lack of interaction with the instructor as well as with other students is the most cited reason for dissatisfaction with the asynchronous courses [10]. Despite many advantages of asynchronous courses, synchronous courses are often preferable, owing to the immediate feedback, increased level of motivation, and an obligation to be present and participate [9].

Furthermore, the courses labeled as hybrid, blended, or mixed describe any combination of the face‐to‐face, asynchronous, and synchronous paradigms, for example, face‐to‐face lab exercises, recorded lessons, and synchronous office hours and tests. Hybrid courses mixing synchronous and face‐to‐face delivery methods are somewhat more satisfactory than fully online courses [10]. A balanced hybrid course should include a so‐called right mix of traditional instruction and online delivery [7].

The perception of online support service quality is a significant predictor of online learning acceptance and satisfaction for students [30]. The e‐learning service quality involves three subdimensions:

E‐learning system quality.

E‐learning instructor and course material quality (the instructor quality being the most influential of all [42]).

E‐learning administrative and support service quality [41].

The preparation of fully online educational programs is quite a huge step. The following set of guidelines well summarizes the principles of organization of online university programs: A strategic, whole‐institution approach; an early engagement of stakeholders; a vital role of teacher presence in online classes; redesign of content, curriculum, and delivery method for online learning; institutional framework for stakeholder interventions; student support services based on collaboration, and learning analytics [52].

When it comes to the transition to online learning, universities should not just assume that faculty can teach effectively online but should instead provide faculty with instructional courses and workshops [25, 56]. The instructional activities are usually on so‐called staff teaching faculty bases. Other models also exist, including faculty teaching faculty, early‐career faculty teaching faculty, and student teaching faculty [4]. There is a challenge for lecturers to shift from this passive to active learning strategies [44], and this challenge becomes even more significant in the context of a transition toward online teaching.

Although making a choice of online education delivery and support platforms, commonly known as learning management systems (LMS), might seem focal in this transition, quantitative studies have repeatedly shown this choice to be quite insignificant [10, 14]. Preparing useful instruction guides can also be crucial, but the experience has shown that students do not pay much attention to the content of such guides [45].

University educational systems are generally so complicated and convoluted that it is challenging to tie a measured outcome and a single controlled factor, e.g., a level of knowledge that students have gained and a better feedback from the instructor. A learning experience is typically less tangible, straightforward, and measurable than, say, a software application designed by programmers [22].

The transition to the online courses relies, thus, on trust and subjective impressions, at least to some extent.

A virtual classroom is a teaching and learning environment designed using software by the teachers in a way that should support collaborative learning among students, even though they can attend this classroom in times and places of their choosing [20]. However, how to enable interaction online remains a central question. Thinking of online feedback is essential due to the usual lack of face‐to‐face communication in an online course [1]. Online courses offer new types of interactions, such as computerized feedback [57]. The student‐to‐student interaction, sometimes overlooked by teachers, has an essential impact on the overall success of distance learning. It is a subject of research in the field of computer‐supported collaborative learning. Some students attend graduate school not only to learn, but also to build professional and social networks for their first or next job, or for the opportunity to begin their own start‐up company [14]. This should not be forgotten in a transition to distance learning.

The lecturers' role is not a simple one in an online setting, as lecturers must engage the students in a variety of cognitive tasks, such as responding to questions, making questions, thinking, reasoning, analyzing information, and rehearsing and retrieving information [26]. Lecturers are being transformed from mere information delivery specialists to guides and facilitators of learning [35] in the whole education system, and even more so in an online context with all its possibilities of recording, searching, and streaming content such as open courses, wikis, and vlogs.

2.2. Education in a time of crisis

Education in a time of crisis is a process that relates to the formation of the population being affected by natural disasters and armed conflict [50]. Numerous reports by various UN bodies have highlighted the importance of young people for the development of postcrisis society. It is imperative to react rapidly and respond to the students' needs early in the process of education restructuring, regardless of the problems with providing educational resources.

The education process in a crisis, for some people, is a short‐term solution that should bridge the gap to overall normalization in society. The authors in Reference [43] dispute this concept, because it ignores the role of education as a social and cultural institution used by society to instill attitudes, values, and certain types of knowledge. Crises can produce an environment where current changes in the education system can be much more accessible than in regular times. Authors in Reference [55] clearly state that crises provide an opportunity to transform education based on the model adopted at Jomtien World Conference on Education for All.

In Reference [43], the authors emphasize that any transition of the educational system in the state of emergency must be developmental. They suggest starting with simple solutions and continually change over time with the use of new teaching methods. Regardless of the state of emergency, they believe it is necessary to restore educational institutions' work and to implement profound changes in the educational process. Moreover, a well‐designed educational model with smart solutions can help students in crises to overcome situations like fear, loss, stress, violence, and to learn tolerance, risk reduction, and life skills [27].

3. THE MODEL FOR A RAPID TRANSITION

The model of distance learning, in its modern form, mainly develops within a specific pedagogical, technological, social, and economic context, and its realization is a big challenge. For this reason, the transition from traditional to distance learning model is not a simple task, and educational institutions sometimes begin implementation without thoroughly examining the academic soundness of this approach [34]. In contrast, some universities and high schools have approached this study earnestly. They have actively worked on changes in organizing and functioning. These changes are being driven by the combined forces of demographics, globalization, economic restructuring, and ICT technology—forces that will, over the coming decade, lead us to adopt new conceptions of educational markets, organizational structures, how we teach, and what we teach [39].

Some universities have already reformed the traditional educational process, and the distance learning method is applied. A large number of universities have gradually introduced changes through the blended learning approach to education, combining online educational materials and online interaction opportunities with traditional place‐based classroom methods [40]. These universities implement some frameworks for blended learning using various solutions (such as LMS Moodle and Canvas) within the primary educational programs' disciplines. Their goal is to ensure that the blend involves each learning environment's strengths and reduces its weaknesses. Unfortunately, there are still many universities that have not yet begun any process of distance learning adaptation. The fact is that universities around the world are beginning the transition from different starting points.

The main objective of this study is to develop a model for a rapid transition to distance learning, which should provide continuity and the appropriate quality of the education process in crisis times. For new education methods to succeed, teachers need to focus on designing new learning activities and helping students acquire specific knowledge by adopting and integrating distance learning tools and technologies in the best way. It is important to emphasize that distance learning should be student‐centric and to know the characteristics of students to identify potential barriers to learning, such as motivation, costs, learning feedback, communication with teachers, student support and services, sense of isolation, and training [16]. Understanding this, teachers can create a strategy that removes or reduces these barriers and increases students' motivation for distance learning. For this strategy, teachers must possess specific pedagogical knowledge and skills and be ready to change their teaching process concerning the change of learning methodology. Teachers should apply the following methodologies:

activity‐oriented teaching methodologies (e.g., active learning, flipped classroom, and project‐based learning) [18] and

technology‐oriented teaching methodologies (e.g., online courses, teaching support via websites and social media, game‐based learning) [24, 31, 38].

Using distance learning technology, teachers have the freedom to do their best and inspire, give creative answers, express critical thinking, provide contextual feedback, assess, and provide individual support. At the same time, technological networking re‐establishes classrooms in a virtual form where the teacher is a moderator, providing support, guidance, and orchestrating learning [23]. His/her task is to find the best way to encourage and motivate students to be more actively involved in the teaching process and more engaged in the knowledge acquisition process.

Students must also be prepared to accept the change of pedagogical paradigm. Distance learning technology increases student autonomy and the possibility of choosing a suitable learning mode according to their learning styles. It is important to emphasize that there is no strict association between learning and the classroom. The main idea is to provide students with the necessary guidance and skills for self‐learning, not only to complete the current course but also for their further professional development [23].

We find it necessary to provide particular prerequisites, such as appropriate IT infrastructure and a well‐organized learning resource basis. However, in case of emergency, this is very difficult, as a prompt and effective response is necessary.

Emergency remote teaching [21] is a temporary solution that needs to provide an alternate teaching delivery model implemented in crisis times. The speed of transition becomes the most significant parameter. It mainly depends on the readiness of the participants, especially the teachers, to accept new learning methods and tools that already exist.

Once the crisis is over, some educational institutions will return to the previous teaching delivery methods, such as face‐to‐face or blended learning. For this reason, the goal of our research is to:

investigate the effects of modern teaching methods on all participants in the teaching process during the state of emergency and

recommend future use of these methods in the postcrisis period.

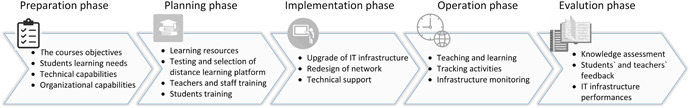

This study focuses on identifying the fundamental mechanisms that should enable a rapid transition to the distance learning model. As shown in Figure 1, the process of transition to the distance learning model consists of five phases: (a) preparation phase, (b) planning phase, (c) implementation phase, (d) operation phase, and (e) evaluation phase.

Figure 1.

The model of transition from a traditional to a distance learning model

3.1. Preparation phase

Distance learning in a time of crisis requires thinking out of the box to solve transition challenges creatively. It is a way to find suitable delivery methods in circumstances when the focus must be on rapidly changing needs and limitations of resources, such as faculty support and training [19].

The emphasis on a prompt shift to distance learning in a time of crisis potentially carries the risk of reducing the quality of delivered courses and requires the faculty to take greater control over the design, development, and implementation of courses. The need to immediately "get it online" is in contradiction to the time and effort dedicated to developing a quality course in regular situations [21]. Usually, the educational institutions start their transition to distance learning from the different starting points, that is, with different levels of digital skills and previous knowledge about digital technologies. Some of them (as computing schools) are dealing with digital technologies, and their teachers have significant expertize in this field. Other educational institutions, especially those in nontechnical fields of studies, will have to invest much more effort and time. The educational institution support teams must find ways to provide teaching continuity, focusing on helping teachers and students to develop skills for work in an online environment (e.g., preparation of learning materials and access to the virtual classrooms).

The first step in the preparation phase is to assess whether the redefinition of course objectives is necessary, taking into account the need for a rapid transition to distance learning. It is necessary to consider students' learning needs and available technical resources and organizational capabilities. This process may result in the alteration of the original course objectives, but the goal of educational institutions and teachers must be to maintain course integrity (e.g., to keep maintain course integrity, hands‐on labs are often replaced by computer simulation). For this reason, the educational institutions must find an effective way to support students and to meet their needs as much as possible, taking into account the global crisis, availability of technologies, costs, and geographical constraints [49]. The main challenge is to ensure a high level of interaction between teachers and students and the students themselves, and to provide students' services such as access to a learning resources database, on‐site support, and timely student feedback [8]. The interaction can alleviate the effects of living in isolation during a state of emergency.

Considering this, the following aspects are highlighted.

Virtual classrooms (similar to the traditional synchronous method of teaching in the classroom).

Access to infrastructure with prepared and well‐organized teaching materials (presentations, video and audio content, electronic literature) and easy retrieval of required content.

Remote access to and work with equipment in laboratories, which is vital for gaining engineering knowledge and hands‐on experience in roughly realistic conditions.

Virtual discussion groups to provide students with the necessary explanations, supporting their independent work and logical thinking, and carefully examining opinions that can improve the quality of the course.

Methods for knowledge assessment (homework, project, and quiz).

Besides human aspects of distance learning programs [16], it is necessary to consider the organizational and technical potentials for the transition carefully. In this sense, administrative structures and technical support are areas that must be organized differently and adequately harmonized with the new technical environment. Therefore, special administrative structures committed to the success of the transition to distance learning [36] must be established within educational institutions. Technical capabilities are related to technology possibilities and are usually associated with problems such as financing new technology solutions, hardware and software issues, Internet connectivity, and staff that supports them.

3.2. Planning phase

Educational institutions must pay special attention to the quality of material prepared for distance learning courses. It must take into account course standards, curriculum development and support, course content, and course pacing in the process of planning distance learning programs. In the planning phase, the educational institutions should immediately begin with testing teachers' knowledge in preparing teaching materials (recorded lectures, multimedia materials, and other e‐contents in the learning resource databases).

A well‐organized and efficient LMS is essential, as it should allow access to the knowledge bases and easy retrieval of the desired material. Educational institutions must make effective use of the limited resources available to harmonize with the environment to reduce financial problems. For this reason, it is necessary to:

examine the capabilities of different platforms, including their integration with existing IT infrastructure,

assess the financial capacity of an educational institution, and

conduct training of teaching staff and students for using the selected platform.

Training and support for teaching staff are mainly needed to preserve the continuity of teaching according to the schedule in this rapidly changing situation. The training should be well thought out, as many teachers resist changing traditional teaching methods. Teachers should take an intermediary role between students and learning resources. Their task is to make the learning process easier for students, but they must have a certain level of skills in the technology they will use. This is the main prerequisite for them to be capable of recognizing diverse learning needs and applying concrete solutions to deliver material in many different formats [3].

To acquire the knowledge needed to conduct online teaching effectively, teachers must have the necessary training, mentoring, and support in work with tools they will use. In teacher education, we have used computer‐based technology, which includes the following functions at a minimum:

availability of administrative and support services,

techniques for encouraging interaction,

development of backup and contingency plans, and

copyright and other policy issues.

Courses via the Internet have existed since 1994, and students often use advanced Internet services [32]. However, some students are not ready to work in this environment, and they can disrupt other students and teachers in the virtual classroom [12]. Training with written instructions for work in a distance learning environment and active support has great importance for students.

3.3. Implementation phase

In the process of rapid implementation of distance learning, the educational institutions meet with a range of academic and administrative issues. Faculty working conditions, redefinition of course objectives, and student support services are some of the challenges that follow this process. In the implementation phase, it is necessary to address these challenges and the accompanying institutional changes carefully.

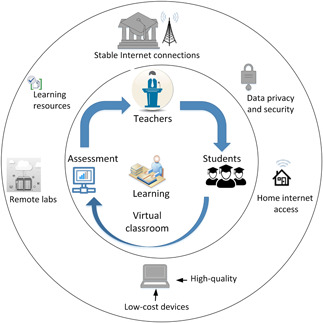

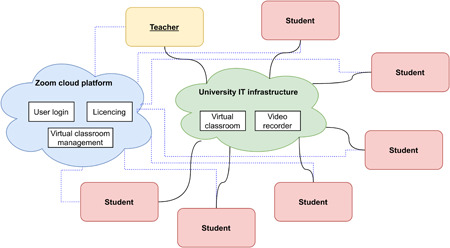

For a successful implementation of distance learning, the educational institution must have a robust and flexible IT infrastructure that supports different types of engagement and provides ubiquitous access to technology tools that allow students to learn and research [53]. It primarily includes a stable Internet connection that facilitates communication and collaboration between students and teachers, and provides access to learning resources stored in the organizations' network or a cloud (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

IT infrastructure that supports distance learning

To successfully implement the transition to distance learning, it is necessary to examine the capabilities of existing IT infrastructure and examine the possibilities for applying new learning technologies. Presumably, in most cases, there are no necessary technical prerequisites. Therefore, it is necessary to upgrade the infrastructure to connect the cloud platform and support work in virtual space. Implementations of these technologies imply the transition of information any time, anywhere, through networks. For these reasons, it is often necessary to redesign the network to provide optimal network resource utilization.

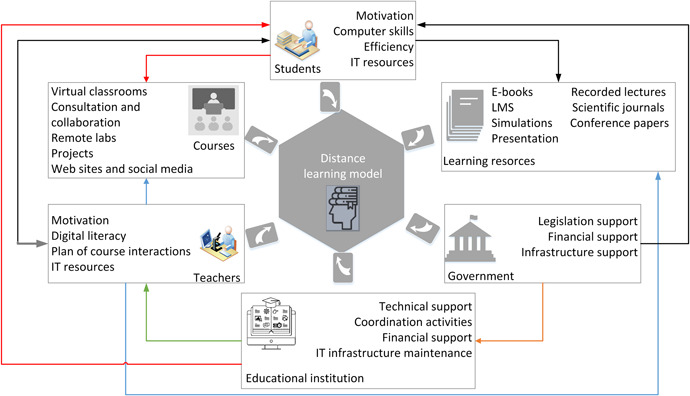

3.4. Operation phase

In the operation phase, teachers and students use teaching materials and network infrastructure for distance learning. Figure 3 shows the distance learning model for high education institutions. After defining course objectives, teachers create teaching materials and define the necessary hardware, software, and network resources. The next step is the reservation and allocation of resources necessary for the course realization in a virtual environment. It implies the usage of different solutions, such as virtual classrooms, remote labs, and various social media. Considering the different needs and habits of students, the existence of a good base of e‐learning resources is of great importance. Besides LMS, it is necessary to provide high‐quality presentations, recorded lectures, scientific papers, and e‐books. Generally speaking, educational institutions have an integrative role and must provide a certain level of coordination, technical, and financial support to enable continuity and quality of education process.

Figure 3.

A distance learning model

3.5. Evaluation phase

The evaluation phase is the final stage in developing a model of the rapid transition to distance learning. This phase has both educational and technical aspects, and it consists of students' knowledge assessments and gathering the students' and teachers' opinions about the applied teaching methods. The knowledge assessment consists of tests and oral presentations of the project.

At the end of the courses, students' and teachers' opinions about the courses obtained through the surveys should provide valuable information and present an excellent basis for analyzing the proposed model. The data collected provide a reliable basis for a solution that the university could implement in the postcrisis period. This solution includes the modifying of existing methods or the implementation of new teaching methods, as well as the upgrading of existing curricula.

Technical evaluation is based primarily on monitoring network performance, as well as on the parameters on which the functionality of distance learning services and the entire IT infrastructure depend. Therefore, it is necessary to continuously monitor the consumption of resources, such as virtual machines with hosted meeting points and leased resources (the number of virtual classrooms used simultaneously and the number of students who can participate in each one).

4. MODEL IMPLEMENTATION

The proposed model has been implemented in the School of Computing, Belgrade, and the High School of Computing as its partner institution. The School of Computing is known for having students who often win medals at international competitions in various fields of computer science. One of the reasons for their success lies in the fact that they learn and research on a very complex IT infrastructure.

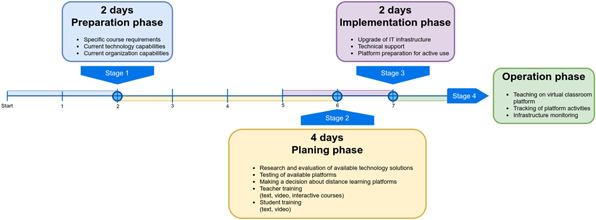

4.1. Preparation phase

To adequately respond to the challenges posed by education in isolated living conditions, we performed the first three phases of the proposed model of transition to distance learning through a short period of 7 days (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The timeline of the first three phases

The transition started while the teaching process was still in the physical classrooms. We followed the step‐by‐step model presented in this paper thoroughly. As some of the steps were independent, we performed them in parallel, with overlapping (e.g., while planning some activities, we could already implement some other). Although we succeeded in switching the complete teaching to the distance mode within one week, it did not mean that our transition was over. The first several weeks of distance teaching were support‐intensive, with much fine‐tuning of the new model. For example, we had to respecify the rules of the scheduling for virtual classes, to help colleagues with software and hardware issues, to document different procedures and to persuade some of our colleagues and students to accept the online classes.

4.2. Planning phase

Educational institutions have their IT infrastructures built in different technologies and technical capabilities, and the choice of a distance learning platform depends on it. However, crisis management requires a swift and efficient process of transition. The educational institutions need to investigate the platforms offered in the market quickly (e.g., Zoom, Google Meet, Cisco WebEx, and Microsoft Teams) and check the possibility of their integration with the existing IT infrastructure and the achievement of the goals defined in the preparation phase [11]. Following the requirements and objectives defined in the preparation phase, we performed testing and selection of the platform in a short time (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of virtual classroom platforms and a result of testing in the School of Computing, Union University in Belgrade

| Criteria\platform | Zoom | Google Meet | Cisco WebEx | Microsoft teams |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nr. reviews [15] | 23,497 | 3,840 | 10,339 | 6,307 |

| Available for free limited use [15] | Yes, 40 min for more than 2 participants | Yes, limited features | Yes, limited features | Yes, limited features |

| Ease of use [15] | 9.0/10 | 9.1/10 | 8.6/10 | 8.6/10 |

| Easy to set up [15] | 8.9/10 | 9.1/10 | 8.3/10 | 8.5/10 |

| Easy to admin [15] | 8.9/10 | 8.9/10 | 8.4/10 | 8.3/10 |

| Quality of support [15] | 8.7/10 | 8.4/10 | 8.4/10 | 8.3/10 |

| Screen sharing | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Recurring meetings | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Waiting room | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Mute on entry | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Rise‐a‐hand signaling | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Whiteboard | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Recording | Cloud/local | Cloud | Cloud/local | Cloud |

| Annotation | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Chat | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Supported platforms | Windows/Mac/Linux/Android | Android | Windows/Mac/Linux/Android | Windows/Mac/Linux/Android |

| Web‐based client | Yes, limited | Yes | Yes | Yes, limited |

| On‐premise hosting | Yes, meeting connector and recorder | No | Yes | No |

| Price | 20$/mo/host | 25$/mo/hosta | 27$/mo/host | 12.5$/mo/hostb |

| Special offer for educational organizations | 1,800$ for 20 hosts/year | Free with G‐suit for education | Not publicly available | Free with Office 365 for education |

With all G‐suit features.

With all Office 365 features.

The main criteria for choosing the platform was the potential for easy and fast implementation. The first choice was Google Meet, as our school already uses G Suite for Education. However, lack of functionality, such as mute on entry or divided roles of teachers and students, has led to the decision to find alternatives. WebEx and Zoom both offered all we needed, but WebEx did not offer an easily calculable cost for its services, its cost was higher, and we were afraid of hidden costs. The Zoom offered a clear licensing solution for educational organizations and included exact specifications of what is in the offer.

For a smooth and rapid transition to new learning methods using virtual classrooms and Moodle, the School of Computing had prepared written and video tutorials for students and teachers. Tutorials with a step‐by‐step approach provided detailed instructions, even for users with no previous experience with similar tools. Besides these tutorials, the technical support team was highly engaged in communication with less technology‐skilled teachers and students to help them resolve individual issues in tools' adaptation.

4.3. Implementation phase

A part of infrastructure is on‐premises, whereas a large amount of teaching material and other educational resources, as well as some of the services, are stored on the cloud. Given the circumstances and the importance of the transition, the faculty upgraded its IT infrastructure and leased a service on the Zoom cloud platform. The result of this integration is the hybrid cloud infrastructure. This approach ensures partial independence from the operation on the Zoom cloud platform. It gives us a chance to optimize network traffic, as the location of most students and teachers is within the country and optimize Internet access links. We chose the solution shown in Figure 5 to avoid the excessive load of international Internet links that could occur during the crisis.

Figure 5.

Integration of existing infrastructure with the Zoom cloud platform

Upon the implementation of this solution, we have maximized the utilization of faculty IT resources. Figure 5 shows a part of the server infrastructure, with virtual machines hosting the meeting points. The administrators have created additional virtual machines on existing servers, for recording, processing, and archiving the teaching activities in virtual classrooms. Access to these virtual machines allows students and teachers to watch recorded classes on demand. With this approach, we have avoided the additional costs we could have had if we had decided to lease storage space on the Zoom cloud.

4.4. Operation phase

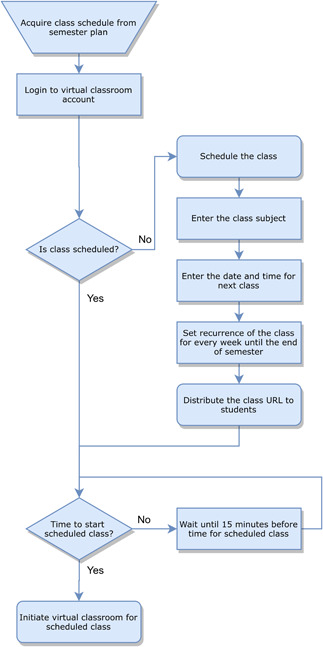

Maintaining teaching continuity requires a systematic transition to online teaching. Therefore, from an organizational point of view, the decision was made to lease the number of licenses for virtual classrooms that matched the current number of traditional classrooms. This decision has kept the existing teaching calendar, the class schedule, and the organization of students in groups. The teachers reserve virtual classrooms according to the timetable, thus creating unique URLs (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

A diagram of the class scheduling process

The distribution of URL addresses is critical to form a virtual classroom, as students access the virtual classroom at the appropriate time. For a more efficient URL distribution, we have created a central register. Some teachers and students do not have experience working in virtual classrooms, and providing quality material with detailed instructions and video presentations is of great importance. The distribution of the materials with information about technical support and organization must be complete as soon as possible.

The continuity and quality of the teaching process are essential goals in a state of emergency. The educational institution needs to establish a certain level of control (whether the classes are going on and whether the students are present). Therefore, it should access log files in CSV format and analyze these files. The recorded material is available for students in the learning process, who can access it through a dedicated portal.

The implementation of virtual classrooms does not exclude the need for an asynchronous interaction between teacher and student through a forum or an email dialog. A forum is a form of group communication that is not limited in time and has been organized according to thematic units. It is available to all students, and we have used it to encourage the creative discussion that should lead to the improvement of existing courses. We have implemented forums through the Moodle platform on the existing IT infrastructure and used this platform to upload projects, parts of teaching material, homework, and test knowledge. Moodle has been selected as an adequate solution for mass testing by applying different types of tests, as virtual classrooms can only be used for oral presentations of students' projects. Some teachers have had a resistance to accept Moodle as an assessment tool, because they are accustomed to traditional testing methods. Therefore, the preparation of instructions and their interactive training were required.

5. THE EVALUATION OF THE RAPID TRANSITION MODEL

We have evaluated the proposed model in the School of Computing in Belgrade as an integral part of the model development process. The model was closely followed by the High School of Computing, our partner institution, formally, but not essentially separate from our institution. The evaluation should help us improve the model of a rapid transition to distance learning in times of crisis and assess some of the methods that can be applied in the education process in case of a prolonged crisis or after the crisis.

5.1. Method

We have evaluated both the main aspects of the proposed model, the technical and the educational ones. First, it was necessary to analyze the performances of the IT infrastructure, so it has been monitored closely. Second, it was necessary to collect the stakeholders' feedback from communication, conduct surveys, and analyze the obtained information.

The goal of this evaluation is to get answers for the three research questions.

-

RQ1.

What is the impact of the rapid transition to distance learning on the educational process and students' knowledge in crisis times?

-

RQ2.

What are the students' attitudes toward distance learning that we have implemented using the described approach, and how is their overall satisfaction with it?

-

RQ3.

What are the key teachers' and students' impressions about the implemented rapid transition, and how do they differ?

We have collected four different types of data to validate our model and explore its characteristics with visualizations, descriptive statistics, and inferential statistics. (a) Technical data have been collected, leveraging the tools of used platforms to monitor the realization of the online classes according to the schedule, the attendance at the online classes, and the exploitation of the virtual classrooms and network resources. (b) The objective measures of the success of distance learning transition were described by these technical data, as well as by the outcomes of learning processes, especially by the results of the knowledge assessment activities. (c) To measure the subjective perception of the transition, extensive surveys were conducted. (d) Furthermore, we have also obtained valuable semi‐structured information via emails and support talks with the stakeholders.

5.2. Survey and participants

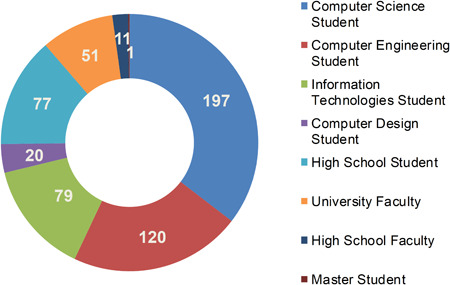

Overall, 416 university and 77 high‐school students, as well as 51 university and 11 high‐school teachers, have completed the anonymous questionnaires. They have all been either studying or teaching computer‐related programs (Figure 7). They have participated in the transition to distance learning since the state of emergency was declared.

Figure 7.

The structure of the participants in distance learning courses who have completed the survey

The questionnaires consisted of 56 statements for students and 47 statements for teachers (Appendix A and B). The participants in the survey had to express their level of agreement with the statements on a Likert‐type scale from 1 (fully disagree) to 5 (fully agree). The statements were organized into three main groups on the basis of a time aspect:

statements about the transition to distance learning (concerning the past),

statements about current distance learning (concerning the present state), and

statements about distance learning after the end of the state of emergency (concerning the future).

The statements concerning the present state had been further organized into five subgroups. Most of the statements were either the same for students and teachers, or symmetrically formulated, and several statements appeared only in one of the two questionnaires. The students got a subgroup of statements concerning their general digital competence and their style of use of digital technologies, which the teachers did not get. Cronbach's α reliability coefficient is .630 for the whole students' questionnaire, which is acceptable.

To check whether a stakeholders' role in the education process—“student” or “teacher”—affects the level of agreement with a statement, we have conducted the one‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests. To compare all participants' levels of agreements for two selected statements, we have conducted the correlation tests. We have also performed several machine learning analyses.

5.3. Analysis of results

5.3.1. Results of the monitoring of IT performances

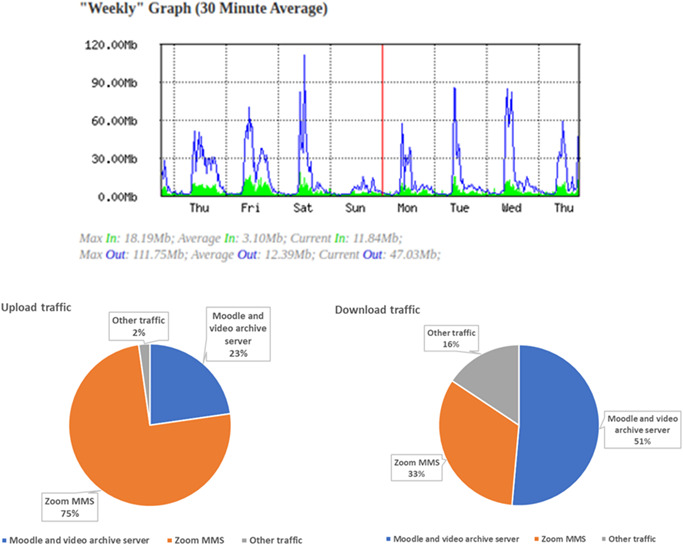

In a situation where students and teachers are in quarantine or with minimal mobility, the availability and reliability of educational services are crucial. Therefore, it is necessary to monitor the network performances of underlying IT infrastructure and traffic structure to respond in case of any incident situation promptly (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Weekly measurement of Internet traffic and its structure

Considering that we have decided on and implemented a hybrid cloud infrastructure (Figure 3), it is imperative to monitor the load of the private part of the cloud infrastructure (primarily the availability of bandwidth). Any occurrence of congestion would lead to a decrease in the quality of communication and would inevitably lead to a decline in the quality of teaching.

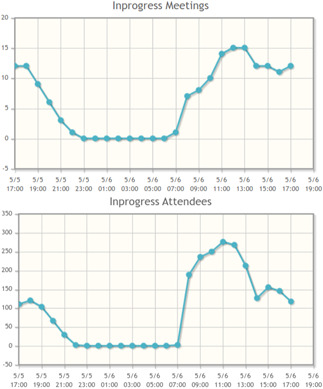

It is also necessary to monitor the consumption of public cloud resources continuously. For these reasons, we keep track of a daily number of virtual classrooms used simultaneously and the number of students who participate (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

The daily overview of the number of active virtual classrooms and participants simultaneously

5.3.2. Educational process and students' knowledge

To obtain the answer for RQ1, that is, to assess the success of the transition to distance learning in crisis, we must evaluate the aspects of continuity and quality of the education. Succeeding to maintain an uninterrupted flow of the educational process, we believe we have proved that it is feasible that a transition to distance learning does not affect this continuity. In addition to the speed of transition, which is crucial for achieving the continuity of education, it is necessary to consider the quality of knowledge that students have acquired during distance learning.

Being a primary purpose of an educational institution, the assessment of knowledge is also challenged with the distance paradigm. A widespread belief that it is easier for students to cheat online might provoke an increased temptation and could be considered as insulting to students; nevertheless, it has been suggested that cheating should not be a problem if a course is well designed, which usually means that professors have to provide a large pool of questions [46].

We have assessed the students' knowledge after our rapid transition through the organization of tests, control tasks, and other similar activities. Overall, we have two main conclusions: the level of students' knowledge is satisfactory, and there is a polarization in opinions about the distance assessments.

The points obtained by the students sometimes vary from the points obtained in physical classrooms in the previous school year, as can be seen for a random sample of courses (Table 2), whose results are normalized on a 0–100 scale. Altogether, the results from this year are similar, or slightly less satisfying, than those from the last year, but still satisfactory. It would be highly difficult to infer a general rule or trend concerning these variations for several reasons. The selection of courses taught in one school year differs from that of the previous year, as teachers change, the methods of knowledge assessment change, and some of the points are hidden. Also, the differences in students' results, even if none of the listed problems occur, can be attributed to numerous factors other than distance learning, for example, differences between the students' generations.

Table 2.

The analysis of the results of assessments on a random sample of courses

| The year 2019: On the premises | The year 2020: Distance learning | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Course | Worst result | Best result | Average result | Standard deviation | Number of students taking the test | Worst result | Best result | Average result | Standard deviation | Number of students taking the test |

| “Machine learning”—classical test | 32 | 100 | 73.7 | 20.9 | 27 | 4 | 100 | 54.8 | 19.8 | 42 |

| “Object‐oriented programming”—test in the form of the programming on a computer | 2 | 100 | 51.9 | 29.5 | 213 | 0 | 91.7 | 30.0 | 23.8 | 246 |

| “Mathematical analysis”—classical test | 0 | 96 | 23.3 | 24.1 | 156 | 10.7 | 96 | 56.8 | 17.5 | 327 |

| “Data compression”—classical test | 29 | 100 | 68.0 | 19.0 | 34 | 0 | 100 | 47.43 | 27.1 | 15 |

| “Design and analysis of algorithms”—classical test | 0 | 96.7 | 37.8 | 19.9 | 143 | 6.67 | 100 | 47.41 | 22.7 | 132 |

| “English language”—classical test | 0 | 100 | 70.8 | 26.0 | 180 | 30 | 100 | 68.6 | 15.0 | 154 |

For these methodological reasons, we must consider the conclusion that the results are satisfying as debatable and open to further analyses. If it were true, it would be in line with the previous research [13, 33, 37, 47] and in contrast with the expectations that the points would be extremely lower due to inherent disadvantages of distance learning, problems with the used technology, and stressfulness of the crisis, or that the points would be higher due to cheating. Interestingly, some teachers firmly oppose the assessments based on distance learning technologies, reasoning somewhat paradoxically that even though they have been getting the distributions of points similar to those of previous years, the assessments in physical classrooms are more objective.

5.3.3. The students' attitudes

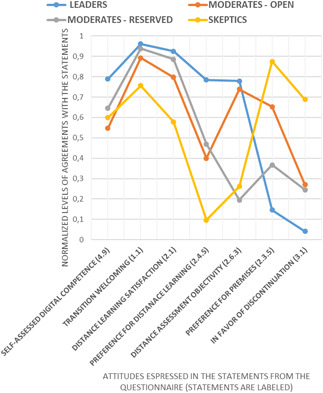

Multiple clustering procedures that we have performed to answer RQ2 lead to the conclusion that several basic subgroups of students could be detected regarding their attitudes toward our rapid transition model. To perform clustering that we will present here, we have used the k‐means algorithm with k = 4, on seven statements from our questionnaire, for 471 students who had expressed their levels of agreement with all these seven statements. The statements were selected as representative for understanding the students' attitudes (Statements 1.1, 2.1.1, 2.3.5, 2.4.5, 2.6.3, 3.1, and 4.9 in Appendix A).

A group obtained through clustering, distinguished by the highest level of self‐assessed digital competences, the most positive attitudes toward the transition, and the strong opposition to the idea of discontinuation of distance learning, gathers the students who we can describe as leaders of our transition. In contrast, another group gathers those students who firmly agree with the statement: "2.3.5 I learn more efficiently in the physical classroom than at home." They would like to see an end to distance learning after the crises, even though their self‐assessed digital competences are not the worst, so we could describe them as skeptics. The students who are somewhere in between these leaders and skeptics can be described as moderates when it comes to our transition. They can further be divided into a more open group and a reserved group, distinguished mainly by their openness toward online assessments and their preference for physical premises. The clusters do not differ significantly in their sizes, with 103, 114,i 149, and 105 students, respectively (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Clusters of students, based on their self‐assessed digital competence and their attitudes toward the distance learning

This insight into the differences in students' attitudes toward distance learning can be useful in organizing the further learning process. For example, while organizing a collaborative group project, teachers might want to include students with different attitudes, hoping for a transition of skills and more positive attitudes from leaders to the other students, or the cluster of skeptics could ask for the most attention of university management in a future online teaching strategy.

We have constructed a Bayesian model to predict the students' overall satisfaction with distance learning. With an accuracy of 44.6% and a Cohen's κ of .188, this model makes a prediction based on a students' digital competency, sex, and program.

5.3.4. The students' versus teachers' attitudes

To answer RQ3, the one‐way ANOVA, comparing the experience of teachers and that of students, shows statistically significant differences for many statements of the questionnaire, especially for those concerning the transition to online teaching and the control of technical aspects. The teachers have agreed more than students with the statement declaring that it is good that the classes immediately switched to the online teaching via Zoom (x̄ = 4.84, δ = 0.412 vs. x̄ = 4.54, δ = 0.833; F(1,553) = 7.53; p = .006). Working with Zoom was a bigger challenge for teachers than for students (x̄ = 2.85, δ = 1.19 vs. x̄ = 1.99, δ = 1.25; F(1,553) = 28.7; p < .001). The same is valid for Moodle (x̄ = 3.08, δ = 1.38 vs. x̄ = 2.67, δ = 1.30; F(1,553) = 4.99; p = .026), which can be explained with more effort and responsibility that the teachers had to invest in the use of these platforms, rather than with the teachers' shortage in technical skills.

Although there has been a statistically significant difference between teachers and students in the perception of how well did students switch to virtual classrooms (x̄ = 4.56, δ = 0.643 vs. x̄ = 4.05, δ = 0.952; F(1,553) = 17.3; p < .001), there has not been such a difference regarding the same switch performed by teachers. The teachers have generally been more satisfied with the online courses than students (x̄ = 4.69, δ = 0.531 vs. x̄ = 4.18, δ = 1.03; F(1,553) = 14.7; p ≤ .001). There has been no significant difference between the two groups in terms of the perception of technical problems and interruptions.

Saving the time needed to reach the premises of university is more valued by students (x̄ = 3.89, δ = 1.37 vs. x̄ = 3.35, δ = 1.52; F(1,553) = 8.10; p = .005). The students appreciate somewhat more the possibilities for interaction in online courses (x̄ = 2.59, δ = 1.44 vs. x̄ = 2.18, δ = 1.25; F(1,553) = 4.66; p = .031), and there is no statistically significant difference when it comes to the perception of more efficient learning in online settings. The students, being at ease in their homes, are more prone than the teachers to believe that they can forget a scheduled term and miss a class (x̄ = 2.42, δ = 1.50 vs. x̄ = 2.00, δ = 1.31; F(1,553) = 4.38; p = .037).

The students perceive the online assessments of knowledge as accurate to a higher degree than the teachers (x̄ = 3.02, δ = 1.37 vs. x̄ = 2.51, δ = 1.39; F(1,553) = 7.62; p = .006), and when it comes to concerns about cheating, they state that they perceive online assessments as more regular (x̄ = 0.30, δ = 1.31 vs. x̄ = 1.85, δ = 1.26; F(1,553) = 22.9; p < .001). The less an actor in the learning process experiences difficulties in working with the Moodle platform, the more that actor appreciates the objectivity of online tests (r(542) = .220; p < .001), the regularity of online tests (r(541) = .196; p < .001), and the time given to solve tests (r(486) = .259; p < .001).

5.3.5. About the future steps

According to the one‐way ANOVA test, the statistically significant differences exist when it comes to five statements concerning the future use of distance learning in light of a possible end of the state of emergency and a dilemma about a return to physical classrooms (Table 3). As shown in the table, while students, on average, disagree that upon the termination of the state of emergency, all online classes should be discontinued, teachers neither agree nor disagree. Among the other statistically significant differences between the two groups, it is interesting that students, on average, agree that all teaching should be held simultaneously in a physical classroom, transmitted live, and recorded. At the same time, teachers tend not to be prone to such an idea.

Table 3.

The future steps related statements that have produced statistically significant differences among the students and the teachers (x̄—mean value, from 1 to 5; δ—standard deviation; F(between groups df, within groups df) = ANOVA F value; p value)

| Statements | Students | Teachers | One‐way ANOVA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x̄ | δ | x̄ | δ | ||

| Upon the termination of the state of emergency, all online classes should be discontinued | 2.29 | 1.36 | 2.69 | 1.37 | F(1,553) = 4.96; p = .026 |

| All classes, except practical exercises, should be continued only online | 2.86 | 1.42 | 2.26 | 1.30 | F(1,553) = 10.1; p = .002 |

| Within a course, it makes sense for a part of the classes to be held in physical classrooms and for the other part online | 3.06 | 1.34 | 3.57 | 1.30 | F(1,553) = 7.84; p = .005 |

| All teaching should be held simultaneously in a physical classroom, transmitted live, and recorded | 3.90 | 1.3 | 2.68 | 4.49 | F(1,553) = 43.0; p < .001 |

| Tests and exams must return to physical classrooms, so that students have fewer opportunities for cheating | 3.19 | 1.46 | 4.21 | 1.07 | F(1,553) = 28.2; p < .001 |

Abbreviation: ANOVA, analysis of variance.

Some results of the correlation tests give us more insight into the attitudes toward future steps. The statement that all online classes should discontinue, once the state of emergency is over, is strongly negatively correlated with the statement about the importance of saving the time needed to reach the university premises (r(549) = −.538; p < .001). Furthermore, those students who take more classes online than they would in physical classrooms are also against this discontinuation (r(488) = −.471; p < .001). The same is valid for those participants in the learning process who find that the online courses have increased the level of interaction among the actors as compared with the courses in physical classrooms (r(551) = −.446; p < .001).

However, those students who think that all the classes, except practical exercises, should continue exclusively online find that the level of knowledge gained through the online courses is higher than that gained in physical classrooms (r(484) = .442; p < .001). The saving of the time needed to reach university premises could be a reason behind the agreement with the statement that it makes sense for part of classes within one course to be in physical classrooms and for the other part to be online. In other words, there is a correlation between the importance of the saving of time and the support for this idea (r(543) = .250; p < .001).

It is interesting to note that preferences for learning in physical classrooms and the worry of forgetting a scheduled term and missing a class while being at home not only have a positive correlation (r(551) = .323; p < .001) but also exhibit a similar pattern of correlations with the other statements. This is peculiar, considering the critical importance of the first statement, and we might explain it by the different personal self‐efficiency styles.

6. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The rapid transition from the traditional to the distance learning model provides the continuity of the educational process in times of crisis. Designing and preparing for this transition is not a simple task, mainly due to the difficulties associated with the necessity to consider the needs for course objectives' redefinition immediately and to identify students' needs. The selection and employment of different and, if necessary, new pedagogical methods are among the main challenges in the effort to preserve and, if possible, improve the quality of education in times of crisis.

Additionally, there also exist preconditions of a technical and organizational nature, such as appropriate IT infrastructure, well‐organized educational processes, and necessary learning resources. After examining these prerequisites, it is possible that the typical university IT infrastructure might not support the transition. It can be necessary to integrate new educational applications and tools into existing IT infrastructure to provide high availability of resources with limited financial costs. Considering this, we suggest the process of a rapid transition to a distance learning model, realized through the implementation of a virtual classroom platform proposed in this paper. The proposed solution is reliable and scalable, and our research pointed out that it is highly suitable for teaching and learning in times of crisis.

A key contribution of our study is a conclusion that, if needed in times of crisis, it is possible to shift the complete educational process of a medium‐sized educational institution, including both lectures and a variety of testing activities, to the distance learning paradigm in a rapid manner and without pauses in the educational process. We emphasized here two important points:

Transitions to distance learning do not need vast preparation and long implementation cycles, and certainly do not need to be year‐long processes.

A transition to a blended distance learning model, which seems to be more attractive for most educational institutions, is less extensive than a complete transformation and, as such, also should not imply a significant period.

In our transition, the points earned in the knowledge assessments do not vary substantially from those obtained in physical classrooms in previous school years. We can conclude that a transition to distance learning does not harm the continuity of the education process and does not substantially endanger its quality. Moreover, the data obtained after the transition show that in distance learning, teachers can get more complex information about the knowledge, potentials, and habits of students, as well as about the factors that influence the active acquisition of knowledge, generally and in the situations of stress, than they could obtain before.

It is easy to check the attitudes and satisfaction of students using the surveys, which are becoming more accessible to conduct than ever before. The obtained results have shown that the majority of students can recognize the benefits of the methods we have applied within the distance learning model and are ready to use them in the postcrisis period actively. However, some students can not fully adapt, which requires more attention to understand the needs and attitudes of these students.

A comparative analysis of the results of the surveys, conducted among students and teachers, has shown that working with distance learning platforms was more challenging for teachers. We have summarized the key implications of this paper in Table 4.

Table 4.

Key implications

| Rapid transition |

|

| Educational institution |

|

| Teachers |

|

| Students |

|

Abbreviations: ICT, information and communications technolog; LMS, learning management systems.

The development of the so‐called backend functions, which would further integrate the current LMS with other university software, would be a significant step forward, boosting the current solution. It would include integration with solutions for student evidence, courses, account administration, and teaching process quality monitoring.

Another challenge might be to include some computer game elements in our solution, making it a gamified learning environment. More computer graphics, levels, points, or competition in an online course could increase its interactivity for users, leading to a higher degree of enjoyment and challenge [2]. Similarly, our solution might, at some point, include more attractive elements of social networking. The students like features such as top‐voted comments that appear in future sessions [29], and we should ensure that they use them more often.

As data collected in distance learning will evolve to big data, we will have to consider the use of business intelligence, data warehousing, predictive analytics, data science, and artificial intelligence to handle these data efficiently.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was financially supported by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia, through Projects No. III 45003 and III 44003.

Biographies

Živko Bojović is an Associate Professor in the Department of Electrical Engineering at University of Novi Sad, Serbia. His research interests include computer networks, e‐learning, cloud computing, and Internet technologies. Bojović received a Ph.D. in telecommunications and signal processing at Faculty of Technical Sciences, University of Novi Sad, Serbia. He is a member of the Centre for Intelligent Communications, Networking and Information Processing from Novi Sad and IEEE and the IEEE Communications Society.

Petar D. Bojović is an Associate Professor at the School of Computing Union University in Belgrade. As the researcher and teacher, he is covering the courses in computer networks and network security. He received the Ph.D. degree in Computer Engineering from the University of Novi Sad in 2019. Currently, he works in the area of computer network security and software‐defined networking.

Dušan Vujošević is Associate Professor and Vice‐Dean for education affairs at the School of Computing, Union University, Belgrade. He received his Ph.D. at Faculty of Organizational Sciences, University of Belgrade in 2012. Working on many commercial projects, he has got the experience with project management and business intelligence technologies. He was an employee at the Stuttgart University, postdoctoral researcher at the Bucharest University of Economic Studies and guest lecturer at the UNAM University, Mexico City. His research interests include human–computer interaction, information management, and decision support systems.

Jelena Šuh is an engineer for technology strategy in “Telekom Srbija” and lecturer at the School of Computing, Union University in Belgrade, Serbia. Šuh received a Diploma degree from the Faculty of Electrical Engineering, University of Belgrade, Serbia and a Ph.D. from the Faculty of Organizational Sciences, University of Belgrade, Serbia. Her research interests include computer networks, software‐defined networking, Internet technologies, and e‐education.

APPENDIX A. STUDENTS' SURVEY

Questionnaire for students about the transition to online teaching, online teaching, and future teaching

The questionnaire consists of four parts. Completing the questionnaire takes about 10 min. You should indicate the extent to which you agree with the statements in the questionnaire. The scale used is interpreted as follows:

1—strongly disagree

2—disagree

3—neutral

4—agree

5—strongly agree

The focus of this questionnaire is on the attitudes of students, which are to be considered in the planning of further teaching. The last, fourth, part of the questionnaire aims to give a broader picture of how students approach network and digital technologies. No question in the questionnaire is mandatory, which means that the student does not have to answer every question. The questionnaire is completely anonymous.

1. TRANSITION TO ONLINE LEARNING

1.1 It is good that the classes immediately transitioned to the online teaching with Zoom.

1.2 The instructions for transition to the Zoom online classes were clear to me.

1.3 From the beginning, I had network and computer resources for online learning.

1.4 I had previous experience of attending online courses.

1.5 Working with the Zoom platform for online learning was a challenge for me.

1.6 Working with the Moodle platform used for online testing was a challenge for me.

1.7 The educational institution has successfully managed the transition to the Zoom online classes.

1.8 Teachers have successfully managed the transition to the Zoom online classes.

1.9 Students have successfully managed the transition to the Zoom online classes.

2. CURRENT ONLINE CLASSES

2.1 General impression about online classes

2.1.1 I am satisfied with how I cope with online learning.

2.2 Technical‐technological aspects of online teaching

2.2.1 I have all necessary network and computer resources for online learning.

2.2.2 Occasional interruptions and technical problems hinder my online learning.

2.2.3 I use a smartphone for online learning.

2.2.4 I use a desktop computer for online learning.

2.2.5 I use a laptop for online learning.

2.2.6 I use a tablet for online learning.

2.2.7 To attend online classes, I connect to the Internet via Wi‐Fi.

2.2.8 To attend online classes, I connect to the Internet via a network cable.

2.3 The difference between physical and online classrooms

2.3.1 At home, more than in the university premises, I am concerned about missing my class.

2.3.2 The saving of the commuting time, which was brought by online learning, is important to me.

2.3.3 I attend more classes online than I would in a physics classroom.

2.3.4 I think that the online teaching has increased the degree of interaction with teachers and other students, compared with the teaching in physical classrooms.

2.3.5 I learn more efficiently in the physical classroom than at home.

2.4 Quality of teaching

2.4.1 I rather watch class recordings than attend live online classes.

2.4.2 I watch a recorded lecture more than once.

2.4.3 It is important for me to see the teacher's face during the online classes.

2.4.4 It is good that the teacher uses an electronic whiteboard for some courses.

2.4.5 I think that the level of knowledge gained through online learning is higher than that gained in the physical classroom.

2.4.6 The applicability of online learning varies drastically from course to course.

2.4.7 Online teaching has stimulated my interest in network technologies.

2.5 Group studying

2.5.1 I regularly coordinate learning and assignments with my fellow students.

2.5.2 I sometimes follow online classes with the family members who are not students.

2.6 Online knowledge assessment

2.6.1 I feel more anxious before an online knowledge test than before a knowledge test in the physical classroom.

2.6.2 I think that the regularity of online knowledge assessment is ensured.

2.6.3 I think that online assessments are an objective way of knowledge evaluation.

2.6.4 I think that the time allotted for online tests is sufficient.

3. RETURN TO PHYSICAL CLASSROOMS

3.1 Upon termination of the state of emergency, all online classes should be discontinued.

3.2 All classes except practical exercises should be continued exclusively online.

3.3 I think that lectures for some courses should be in physical classrooms and online for the other.

3.4 Within one course, it makes sense that a part of the lecture is in physical classrooms and another part online.

3.5 All classes should be held in physical classrooms, broadcasted live, and recorded at the same time.

3.6 Colloquia and exams must be returned to physical classrooms, so that students are less tempted to cheat.

3.7 In the future, I will use teleconferencing more.

OTHER

Year of study:

1

2

3

4

Master

Study program:

Information Technology

Computer Engineering

Computer Science

Master study programs

Gender:

Female

Male

ENTER ADDITIONAL SUGGESTIONS AND COMMENTS (optional):

4 ATTITUDES AND STYLE OF USING NETWORK AND INFORMATION TECHNOLOGIES

4.1 I am well acquainted with the functioning of the Internet, its standards and technological concepts.

4.2 Sometimes I act like I'm an internet addict.

4.3 I implement security measures for the various digital devices I use, including the access passwords and the antivirus protection.

4.4 I think that there is a lot of information that cannot be properly shared digitally.

4.5 It happens to me that I permanently lose some digital information that I saved earlier.

4.6 I use social networks to share important information and content with colleagues.

4.7 I have accepted the algorithmic programming way of thinking and I use it in learning as well.

4.8 I organize my digital content efficiently.

4.9 I am usually the one who advises the others on how to solve technical problems concerning their digital devices.

4.10 I believe that society can be changed if enough people sign online petitions.

4.11 I think I can find a good balance between online and offline life.

APPENDIX B. TEACHERS SURVEY

Questionnaire for teachers about the transition to online teaching and future teaching

The questionnaire consists of three parts. Completing the questionnaire takes about 10 min. You should indicate the extent to which you agree with the statements in the questionnaire. The scale used is interpreted as follows:

1— strongly disagree

2—disagree

3—neutral

4—agree

5—strongly agree

The focus of the questionnaire is on the attitudes of teachers, that are to be considered when planning further teaching. The questionnaire is completely anonymous.

1. TRANSITION TO ONLINE TEACHING

1.1 It is good that the classes immediately transitioned to the online teaching with Zoom.

1.2 The instructions for transition to the Zoom online classes were clear to me.

1.3 From the beginning, I had network and computer resources for online teaching.

1.4 I had previous experience in teaching online courses.

1.5 Working with the Zoom platform for online teaching was a challenge for me.

1.6 Working with the Moodle platform used for online testing was a challenge for me.

1.7 The educational institution has successfully managed the transition to Zoom online classes.

1.8 Teachers have successfully managed with the transition to Zoom online classes.

1.9 Students have successfully managed with the transition to Zoom online classes.

2. CURRENT ONLINE CLASSES

2.1 General impression of online classes

2.1.1 I am satisfied with how I cope with online teaching.

2.2 Technical‐technological aspects of online teaching

2.2.1 I have all necessary network and computer resources for online teaching.

2.2.2 Occasional interruptions and technical problems interfere with my online teaching.

2.2.3 I use a smartphone for online teaching.

2.2.4 I use a desktop computer for online teaching.

2.2.5 I use a laptop for online teaching.

2.2.6 I use a tablet for online teaching.

2.2.7 To teach online classes, I connect to the Internet via Wi‐Fi.

2.2.8 To teach online classes, I connect to the Internet via a network cable.

2.3 The difference between physical and online classrooms

2.3.1 The preparation of teaching materials requires more time for the online classes than for the teaching in physical classrooms.

2.3.2 At home, more than in the university premises, I am concerned about missing my class.

2.3.3 Before every online class, I ask myself whether the technology will work.

2.3.4 I feel less anxious before online classes than before classes in the physical classroom.

2.3.5 I go through the educational content more slowly in the classes I teach online as compared with the classes I teach in physical classrooms.

2.3.6 The saving of the commuting time, which was brought by the online teaching, is important for

me.

2.3.7 I think that the online teaching has increased the degree of interaction with students as compared with teaching in the physical classroom.

2.3.8 I teach more efficiently in the physical classroom than from home.

2.4 Quality of teaching

2.4.1 It is important for me to use an electronic whiteboard.

2.4.2 I chat with students and use the forum.

2.4.3 I allow students to record online lessons or I record my lessons.

2.4.4 My camera is on while I am teaching online.

2.4.5 I give students assignments to solve in virtual groups.

2.4.6 I organize online mentoring or consultations for students.

2.5 Online knowledge assessment

2.5.1 The time spent on the evaluation of students' results is higher in online teaching as compared with teaching in physical classrooms.

2.5.2 The accuracy of the evaluation of students' results is higher in online teaching as compared with teaching in physical classrooms.

2.5.3 The doubt that students did not do assignments on their own is greater for online knowledge assessment than for knowledge assessment in physical classrooms.

2.5.4 I think that the level of knowledge obtained in online classes is higher than the level obtained in physical classrooms.

2.5.5 The applicability of online teaching varies drastically from one course to the other.

3. RETURN TO PHYSICAL CLASSROOMS

3.1 Upon termination of the state of emergency, all online classes should be discontinued.

3.2 All classes, except practical exercises, should be continued exclusively online.

3.3 I think that lectures for some courses should be in physical classrooms and online for the other.

3.4 Within one course, it makes sense that a part of the lecture is taught in physical classrooms and another part is presented online.

3.5 All classes should be held in physical classrooms, broadcasted live, and recorded at the same time.

3.6 Colloquia and exams must be returned to physical classrooms, so that students are less tempted to cheat.

3.7 Online teaching successfully complements physical classroom teaching.

3.8 Online teaching degrades the teacher's role, showing that a teacher can be replaced by recorded lessons.

3.9 I would like to receive instructions, time, tools, and support for the production of more graphically advanced video lessons.

3.10 In the future, it will be easier for me to opt for teleconferencing with colleagues instead of live meetings.

OTHER

Years of work experience in education (approximately, optionally):

ENTER ADDITIONAL SUGGESTIONS AND COMMENTS (optional):

Bojović Ž, Bojović PD, Vujošević D, Šuh J. Education in times of crisis: Rapid transition to distance learning. Comput Appl Eng Educ. 2020;28:1467–1489. 10.1002/cae.22318

REFERENCES

- 1. Alqurashi E., Predicting student satisfaction and perceived learning within online learning environments, Distance Educ. 40 (2019), 133–148. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aparicio M. et al., Gamification: A key determinant of massive open online course (MOOC) success , Inf. Manag. 56 (2019), 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beaudoin M., The instructor's changing role in distance education, Am. J. Distance Educ. 4 (1990), 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Belt E. and Lowenthal P., Developing faculty to teach with technology: Themes from the literature, TechTrends 64 (2020), 248–259. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Biggs J., and Tang C., Teaching for quality learning at university: What the student does, McGraw‐Hill Education, Berkshire, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bower B. L., Distance education: Facing the faculty challenge, Online J. Distance Lear. Adm. 4 (2001), 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Callaway S. K., Implications of online learning: Measuring student satisfaction and learning for online and traditional students, Insights Changing World J. 35 (2012), 345–359. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen L., Distance delivery systems in terms of pedagogical considerations: A revolution, Educ. Technol. 37 (1997), 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen N. S. et al. Synchronous learning model over the Internet, Proc. IEEE Internat. Conf. Adv. Learn. Technol., IEEE, Joensuu, Finland, 2004, pp. 505–509. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/1357466

- 10. Cole M. T., Shelley D. J., and Swartz L. B., Online instruction, e‐learning, and student satisfaction: A three year study, Int. Rev. Res. Open Distance Learn. 15 (2014), 111–131. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dagger C. D. et al., Service‐oriented e‐learning platforms: From monolithic systems to flexible services, IEEE Internet Comput. 11 (2007), 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Earley M. A., Developing a syllabus for a mixed‐methods research course, Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 10 (2007), 145–162. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fowler R. C., The effects of synchronous online course orientation on student attrition, Ph.D. Thesis, Univ. of South Carolina, 2019.

- 14. Freeman L. and Urbaczewski A., Critical success factors for online education: Longitudinal results on program satisfaction, Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 44 (2019), 30–645. [Google Scholar]

- 15. G2, Compare Zoom, Google Hangouts Meet, Cisco Webex Meetings, and Microsoft Teams, availabe at https://www.g2.com/compare/zoom-vs-google-hangouts-meet-vs-cisco-webex-meetings-vs-microsoft-teams