Abstract

Purpose

This study reports the effect of disease-modifying therapies for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) on systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP, DBP) over 6 months and incident hypertension over 3 years in a large administrative database.

Methods

We used administrative Veterans Affairs databases to define unique dispensing episodes of methotrexate, leflunomide, sulfasalazine, hydroxychloroquine, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, and prednisone among patients with RA. Changes in SBP and DBP in the 6 months before disease-modifying antirheumatic drug initiation were compared with changes observed in the 6 months after initiation. The risk of incident hypertension within 3 years (new diagnosis code for hypertension and prescription for antihypertensive) was also assessed. Multivariable models and propensity analyses assessed the impact of confounding by indication.

Results

A total of 37,900 treatment courses in 21,216 unique patients contributed data. Overall, there were no changes in SBP or DBP in 6 months prior to disease-modifying antirheumatic drug initiation (all P > 0.62). In contrast, there was a decline in SBP (β = −1.08 [−1.32 to −0.85]; P < 0.0001) and DBP (β = −0.48 [−0.62 to −0.33]; P < 0.0001) over the 6 months following initiation. The greatest decline was observed among methotrexate and hydroxychloroquine users. Methotrexate users were 9% more likely to have optimal blood pressure (BP) after 6 months of treatment. Patients treated with leflunomide had increases in BP and a greater risk of incident hypertension compared with patients treated with methotrexate (hazard ratio, 1.53 [1.21–1.91]; P < 0.001).

Conclusions

Blood pressure may improve with treatment of RA, particularly with methotrexate or hydroxychloroquine. Leflunomide use, in contrast, is associated with increases in BP and a greater risk of incident hypertension.

Keywords: blood pressure, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, rheumatoid arthritis

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) have a high prevalence of hypertension, which is often undertreated.1 Chronic systemic inflammation may impact blood pressure (BP) through a number of mechanisms including arterial stiffness, sodium retention, metabolic regulation, and central adiposity.2–4 Previous studies have identified associations between endothelial function, BP, and RA disease activity.5,6 Systemic cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), may have direct effects on arterial stiffness, although the evidence is conflicting.7

The impact of the initiation of disease-modifying therapies on BP has been of interest in RA, a disease with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality.8 There is some evidence that inhibition of TNF-α may reduce BP among patients with RA.5,9 However, the variability in BP over time and many potential confounding factors have made it difficult to assess the influence of different disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) on BP. Large observational studies to assess BP changes following DMARD initiation are lacking because of the unavailability of BP measures in many large administrative databases and registries.10

There is reason to believe that different DMARDs may have distinct effects on BP. For example, leflunomide has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of hypertension in several studies, one recently using a claims database.10 The same study, using a case definition based on administrative diagnosis codes and medication dispensing, noted no difference in the incidence of hypertension among TNF inhibitor (TNFi) users compared with methotrexate. However, a limitation of this study was the lack of assessment of actual BP changes because these were not available. The Veterans Affairs (VA) electronic medical record databases provide a unique opportunity to assess actual alterations in BP occurring after the initiation of individual DMARDs in a real-world setting.

We assessed the changes in BP over 6 months before and after initiation of DMARD therapy in a large observational cohort using VA administrative data, which allowed linkage to vital signs packages and the direct study of actual BP values. The specific aims were (1) to estimate the overall impact of initiation of DMARD treatment on BP, (2) to compare changes in BP across common DMARDs, and (3) to assess important determinants of BP change over 6 months after DMARD initiation.

METHODS

To establish an analytic data set, we used national administrative VA databases: The Corporate Data Warehouse, the Decision Support System, National Pharmacy Extract, and the Pharmacy Benefits Management database between 2000 and 2014. These databases were accessed and linked via the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure.11 Algorithms were used to integrate the information from these 3 sources and to define each dispensing episode of each drug for each patient as previously described.12–14 Treatment courses that did not represent the initial exposure to the drug or were missing values for BP at any time point were excluded (Supplementary Figure 1, http://links.lww.com/RHU/A90).

For this study, we focused on incident courses (first identified in VA records) of 6 commonly prescribed DMARDs, namely, methotrexate, prednisone, leflunomide, TNFi, sulfasalazine, and hydroxychloroquine, among patients with prevalent RA (at least 1 diagnosis code for RA in the preceding 12 months [International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, 714.xx]). Similar definitions of RA have demonstrated an 81% to 97% positive predictive value when using administrative data.15 Each initial prescription fill of a drug was defined as a dispensing episode and a unique observation.12 For each episode, the amount of the drug dispensed, the expected duration of the treatment episode, and the length of the treatment course were determined. The primary exposure for each prescription fill was the type of drug with comparison to methotrexate as the reference. Concurrent overlapping treatment courses were identified to assess the impact of combination therapy with multiple drugs. Patients were considered to have discontinued methotrexate in the prior 6 months if the estimated course end date occurred within that period. Prescriptions for any antihypertensive medications in the 6 months prior to the course start date and in the 6 months after the course start date were also identified from pharmacy databases.

Ascertainment of Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressure

Vital sign packages were queried, and the closest actual values for systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) (as measured and recorded during routine clinical encounters) were linked if they fell within 30 days of the date of interest. These dates included the course start date, 6 months prior to, and 3 and 6 months after the course start date. The change in SBP and DBP was operationalized as the absolute change (in mm Hg) between time points. We also assessed the proportion of patients with adequate BP control (SBP <130 and DBP <90 mm Hg) at each time point. A significant increase in BP from baseline was defined as an increase in SBP greater than 20 mm Hg or DBP greater than 10 mm Hg as previously described.16 Incident hypertension was defined based on the presence of the first documented International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision code for hypertension17,18 falling after the course start date with concurrent use of antihypertensive drugs within the 3-year follow-up. Similar definitions have been observed to have 93% specificity for hypertension in administrative data.19

Other Covariables

Height and weight were also extracted from vital sign packages. Body mass index (BMI) was determined (weight [in kg]/height [in m]2), and values were linked if they fell within 30 days of the date of interest. Results of testing for C-reactive protein (CRP, in mg/dL) were extracted from laboratory packages and similarly linked as a measure of systemic inflammation and disease activity. The most recent positive or negative results at any time for testing for anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies (ACPAs) and rheumatoid factor (RF) were recorded. Comorbid conditions of interest were identified at the start of the treatment course or any time prior, extending back to the start of the relevant administrative database. Coding of comorbidities was based on previously validated algorithms,17,18 or algorithms appearing in peer-reviewed publications.20–24 Comorbidity was assessed using the Rheumatic Disease Comorbidity Index, a validated quantitative measure of comorbid illness in RA.25

Current smoking was considered to be present when recorded as a health factor up to 3 years prior to the course start date. Rheumatoid arthritis disease duration was estimated by searching for the earliest diagnosis code in the medical record. A disease duration of more than 5 years was considered to be present if the first diagnosis code occurred more than 5 years prior. If the diagnosis code occurred less than 5 years prior and more than 1 year after the first available data in the VA system, this was considered to reflect disease duration of less than 5 years. Other scenarios were considered missing/unknown.

Statistical Analysis

Differences in patient characteristics across treatments were tested using analysis of variance or Kruskal-Wallis tests for nonparametric data. To avoid dropping observations, multiple imputations (multivariate normal regression, 5 imputations) were performed to account for missing values for CRP (78%), ACPA antibody status (30%), RF status (16%), and disease duration (>5 or ≤5 years) (30%). Imputation was performed using the following variables: date, age, sex, race, smoking, BMI, comorbid conditions (diabetes, malignancy, congestive heart failure [CHF], lung disease, coronary artery disease, hypertension, interstitial lung disease, lung cancer, colon cancer, prostate cancer), drug course, concurrent medications, use of hypertensive medications, and BP (at all time points). Sensitivity analyses utilizing other imputation methods for CRP demonstrated similar results.

Changes in SBP and DBP were graphed prior to and after the initiation of therapies in the overall sample and in a subsample of individuals who did not receive antihypertensives at any point. The differences in SBP and DBP and the differences in the slope of change in SBP and DBP before and after treatment initiation were assessed using paired t tests.

The propensity to receive a new prescription for prednisone, leflunomide, TNFi, sulfasalazine, or hydroxychloroquine compared with methotrexate was determined for each treatment course using logistic regression with the following independent variables as predictors: course start date, age, sex, race, baseline SBP/DBP, change in SBP/DBP in the preceding 6 months, BMI, CRP, comorbidity score, hypertension, diabetes, interstitial lung disease, other lung disease, any malignancy, lung cancer, prostate cancer, CHF, history of myocardial infarction, chronic kidney disease, concurrent RA therapies (methotrexate, prednisone, leflunomide, TNFi, sulfasalazine, hydroxychloroquine), antihypertensive use in the past 6 months, ACPA/RF seropositivity, disease duration greater than 5 years, and current smoking. Linear and logistic regression models were adjusted for propensity using matched-weighting techniques as previously described.14,26 The standardized difference between treatment groups was assessed over all variables before and after matched weighting to assess for adequate balance. Variables that were not balanced were included in multivariable models.

Multivariable linear regression models assessed the change in SBP and DBP observed with individual DMARDs compared with methotrexate as the reference group. The association between DMARDs and the odds of a significant increase in BP and odds of optimal BP at 6 months was assessed using logistic regression. The risk of incident hypertension within 3 years of the course start date was assessed using Cox proportional hazards regression. Clustering on patient was not performed in the primary analysis because few patients contributed multiple observations, and clustering did not impact estimates. All analyses were performed using Stata 14.0 software (StataCorp, LP, College Station, TX) within the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure.

RESULTS

A total of 37,900 unique dispensing episodes among 21,216 unique patients were identified and included in the analyses. Detailed characteristics of the study population are shown in Supplementary Table 1, http://links.lww.com/RHU/A91. There were a number of statistically significant differences in patient characteristics between those who received different RA therapies that were considered in the analyses. Most notably, there were differences in age, comorbid illnesses, ACPA/RF seropositivity, disease duration, and smoking status.

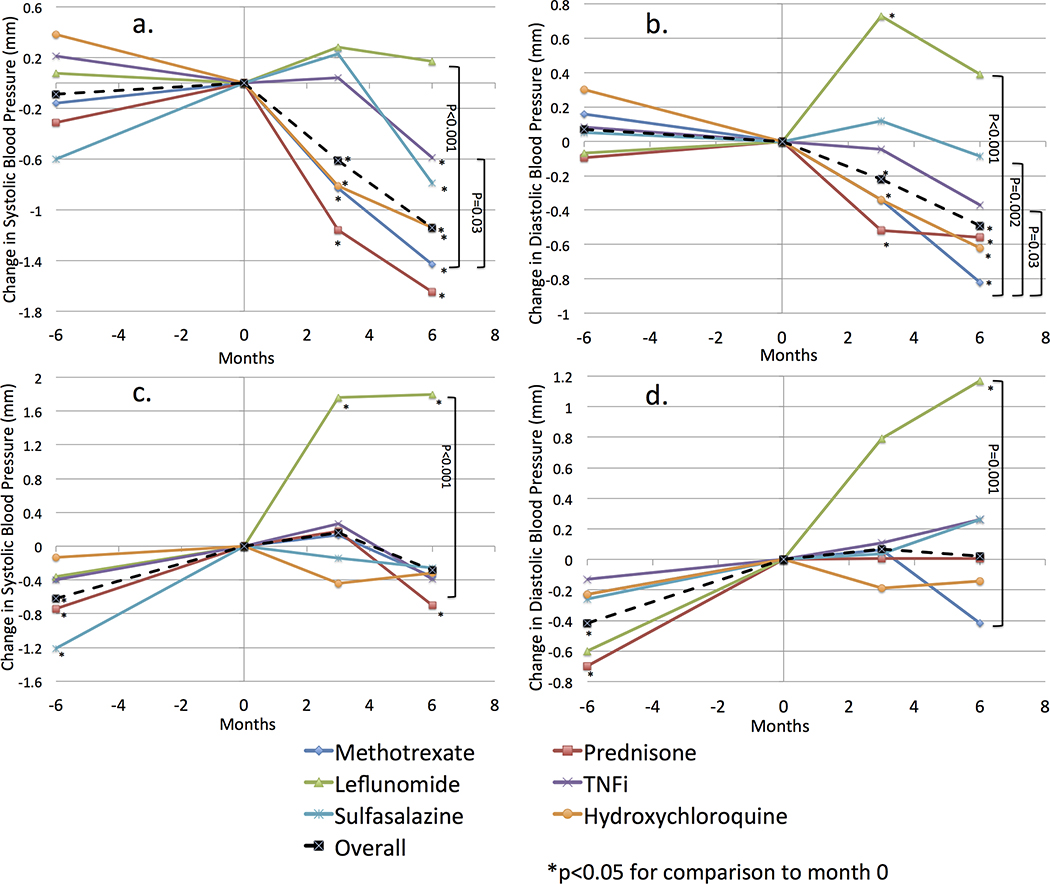

Actual changes in SBP and DBP in the 6 months prior to the initiation of new therapies and in the 6 months after their initiation are illustrated in Figure 1. Among all courses studied, there was no significant overall change in SBP or DBP in the 6 months prior to the initiation of new medications. However, there was a significant overall decline in both SBP and DBP in the 6 months after initiation of therapy (P < 0.0001). The change in BP after therapy initiation was significantly different from the change before initiation (difference in ΔSBP = −1.17 mm Hg, P < 0.001; difference in ΔDBP = −0.41 mm Hg, P < 0.001). Overall, the proportion of patients with optimal BP did not change over the 6 months prior to baseline (P > 0.05), but was greater at 6 months after initiation of therapy (50.0% vs. 47.3%, P < 0.001).

FIGURE 1.

Actual change in BP (unadjusted) in the 6 months before and after initiation of therapies for RA. A and B illustrate change in SBP and DBP, respectively, among all subjects. C and D illustrate change in SBP and DBP, respectively, among individuals who did not receive antihypertensives in the 6 months prior or subsequent to initiation of therapy. Color online-figure is available at http://www.jclinrheum.com.

The change in BP varied by the specific therapy initiated. There was a decline in SBP and DBP after initiation of prednisone, methotrexate, and hydroxychloroquine and a more modest decline after initiation of sulfasalazine and TNFi (Fig. 1). Among those who initiated methotrexate, a greater proportion had optimal BP at 6 months compared with baseline (51.0% vs. 46.8%, P < 0.001). Similar associations were observed for prednisone, TNFi, and hydroxychloroquine (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Proportion of Patients With Optimal BP at Different Time Points

| Proportion With Optimal BP |

Relative Risk |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior | Baseline | 6 mo | Baseline to Prior | 6 mo to Baseline | ARR | NNT | |

| Methotrexate | 0.48 | 0.47 | 0.51 | 0.97 | 1.09a | 0.043 | 23 |

| Prednisone | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.50 | 0.98 | 1.08a | 0.036 | 28 |

| Leflunomide | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.47 | 0.98 | 0.97 | −0.014 | −71 |

| TNFi | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.49 | 0.99 | 1.05b | 0.023 | 43 |

| Sulfasalazine | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.99 | 1.00 | −0.001 | −1000 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 0.50 | 0.49 | 0.53 | 0.99 | 1.07a | 0.036 | 28 |

Also provided are the RR before and after initiation of therapy, the absolute risk reduction, and the number needed to treat.

P < 0.0001.

P < 0.05.

ARR indicates absolute risk reduction; NNT, number needed to treat; RR, relative risk.

In contrast, there was a numerical but nonsignificant increase in SBP and DBP 6 months after leflunomide initiation and a significant increase in DBP at 3 months. The change in BP was numerically but not statistically greater in the 6 months after initiation of leflunomide compared with the 6 months before initiation (difference in ΔSBP = +0.39 mm Hg, P = 0.43; difference in ΔDBP = +0.28 mm Hg, P = 0.38). These increases were statistically different from the reductions seen with methotrexate (P < 0.001). A numerically lower proportion had optimal BP at 6 months among those taking leflunomide (46.5% vs. 48.0%, P = 0.28).

In a subgroup analysis of 8521 individuals who did not receive antihypertensive medications during the study period, there was a significant increase in mean SBP in the 6 months prior to drug initiation (Δ = +0.51 mm Hg, P = 0.003) and DBP (Δ = +0.36 mm Hg, P = 0.002). This slope was significantly reduced in the 6 months after RA therapy initiation (difference in ΔSBP = −0.78 mm Hg, P = 0.001; difference in ΔDBP = −0.32 mm Hg, P = 0.054) (Fig. 1). In contrast, leflunomide was associated with a significant increase in SBP and DBP in the 6 months after initiation and a numerical increase in the ΔSBP and ΔDBP compared with the 6 months prior to initiation of therapy (difference in ΔSBP = +1.44 mm Hg, P = 0.10; difference in ΔDBP = +0.57 mm Hg, P = 0.35).

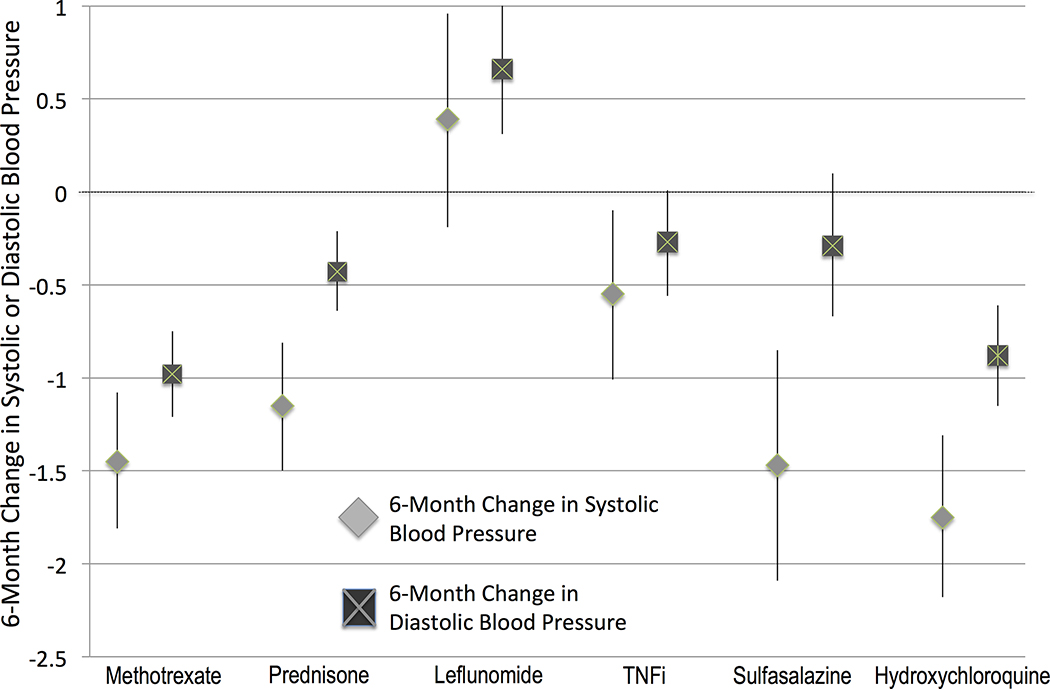

In multivariable models, both leflunomide and TNFi initiation were associated with significantly less improvement in SBP and DBP in the 6 months after initiation compared with that observed for methotrexate (Table 2). Based on this model, only leflunomide would be expected to have an increase in BP at 6 months (rather than a decrease for all other therapies) (Fig. 2). Sulfasalazine and prednisone initiation were associated with less improvement in DBP but similar improvement in SBP, whereas hydroxychloroquine initiation was associated with similar improvement in SBP and DBP compared with methotrexate (Table 2, Fig. 2).

TABLE 2.

Multivariable Models Evaluating Actual Changes In SBP and DBP Associated With the Initiation of RA Therapiesa

| Δ in Systolic BP at 6 mo |

Δ in Diastolic BP at 6 mo |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (95% CI) | P | B (95% CI) | P | |

| Methotrexate | (Reference) | (Reference) | ||

| Prednisone | 0.30 (−0.20 to 0.81) | 0.24 | 0.55 (0.24 to 0.87) | 0.001 |

| Leflunomide | 1.82 (1.15 to 2.50) | <0.001 | 1.63 (1.22 to 2.06) | <0.001 |

| Anti-TNF | 0.88 (0.29 to 1.48) | 0.003 | 0.70 (0.33 to 1.07) | <0.001 |

| Sulfasalazine | −0.030 (−0.77 to 0.71) | 0.94 | 0.69 (0.23, b1.15) | 0.003 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | −0.31 (−0.88 to 0.26) | 0.28 | 0.098 (−0.26 to 0.45) | 0.59 |

| Age (per 1 y) | 0.059 (0.042 to 0.076) | <0.001 | −0.13 (−0.14 to −0.12) | <0.001 |

| Female | 0.73 (0.21 to 1.25) | 0.006 | 1.64 (1.32 to 1.96) | <0.001 |

| Black | 1.28 (0.83 to 1.72) | <0.001 | 0.99 (0.71 to 1.27) | <0.001 |

| BMI (per 1 kg/m2) | 0.13 (0.097 to 0.16) | <0.001 | 0.020 (0.002 to 0.038) | 0.03 |

| Current smoking | 0.28 (−0.16 to 0.72) | 0.21 | 0.59 (0.31 to 0.86) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 2.84 (2.37 to 3.31) | <0.001 | 1.11 (0.82 to 1.40) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 0.23 (−0.16 to 0.61) | 0.23 | −0.89 (−1.13 to −0.66) | <0.001 |

| History of heart attack | −1.76 (−2.37 to −1.15) | <0.001 | −0.75 (−1.12 to −0.37) | <0.001 |

| Interstitial lung disease | −1.06 (−1.55 to −0.57) | <0.001 | −0.24 (−0.54 to 0.067) | 0.07 |

| CHF | −2.21 (−2.73 to −1.68) | <0.001 | 1.03 (1.36 to −0.70) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidity score (per unit) | −0.25 (−0.37 to −0.11) | <0.001 | −0.22 (−0.31 to −0.14) | <0.001 |

| Concurrent sulfasalazine | 1.20 (0.62 to 1.78) | <0.001 | 0.27 (−0.089 to 0.63) | 0.14 |

| Concurrent methotrexate | −0.66 (−1.17 to −0.16) | 0.01 | −0.15 (−0.46 to 0.16) | 0.35 |

| Concurrent TNF | 0.0061 (−0.53 to 0.54) | 0.98 | 0.29 (−0.042 to 0.62) | 0.09 |

| Concurrent leflunomide | 1.65 (0.95 to 2.36) | <0.001 | 1.02 (0.58 to 1.47) | <0.001 |

| Disease >5 y | −0.10 (−0.45 to 0.25) | 0.20 | −0.41 (−0.63 to −0.19) | <0.001 |

| Baseline SBP | −0.54 (−0.55 to −0.53) | <0.001 | — | |

| Baseline DBP | — | −0.49 (−0.50 to −0.48) | <0.001 | |

| Prior ΔSBP | −0.20 (−0.21 to −0.19) | <0.001 | — | |

| Prior ΔDBP | — | −0.23 (−0.24 to −0.22) | <0.001 | |

| Antihypertensives (no use) | (Reference) | (Reference) | ||

| Prior and current use | −0.57 (−1.05 to −0.081) | 0.02 | −0.64 (−0.94 to −0.34) | <0.001 |

| New Use | −0.96 (−1.71 to −0.21) | 0.01 | −0.37 (−0.84 to 0.093) | 0.12 |

Also included in the models but non-significant and not shown in tables (P > 0.05): concurrent prednisone, concurrent HCQ, concurrent TNFi, CKD, any malignancy, lung cancer, other lung disease, ACPA positivity, RF positivity, and CRP.

CI indicates confidence interval; CKD, chronic kidney disease; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine.

FIGURE 2.

Adjusted change in SBP (gray diamonds) and DBP (dark gray squares) at 6 months among patients initiating different therapies for RA. Changes are predicted from multivariable regression models (expected change at the average value of the covariables in the multivariable regression model).

In analyses that considered the propensity for receiving the drug, similar associations were observed as in multivariable models (Table 3). The odds were greater for a significant increase in BP for leflunomide, TNFi, and prednisone users compared with methotrexate users. Optimal BP was significantly less likely at 6 months among those using leflunomide compared with methotrexate (odds ratio, 0.81 [0.74–0.86]; P < 0.001). These results were similar in sensitivity analyses comparing users of prednisone, leflunomide TNFi, sulfasalazine, and hydroxychloroquine who did not use concurrent methotrexate to methotrexate users who did not use these therapies (Supplementary Table 2, http://links.lww.com/RHU/A91).

TABLE 3.

Associations Between Prednisone, Leflunomide, TNFi, Sulfasalazine, and Hydroxychloroquine and BP Outcomes

| Δ SBP |

Δ DBP |

Odds of a Significant Increase |

Odds of Optimal BP |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Methotrexate | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Prednisone | 0.11 (−0.46 to 0.68) | 0.48 (0.12 to 0.83)a | 1.18 (1.10 to 1.27)b | 0.97 (0.92 to 1.03) |

| Leflunomide | 1.76 (0.89 to 2.62)b | 1.51 (0.98 to 2.05)b | 1.37 (1.24 to 1.451)b | 0.81 (0.74 to 0.86)b |

| TNFi | 0.87 (0.20 to 1.54)c | 0.60 (0.18 to 1.03)a | 1.18 (1.08 to 1.28)b | 0.94 (0.87 to 1.01) |

| Sulfasalazine | 1.08 (0.31 to 1.84)a | 0.86 (0.40 to 1.33)a | 1.11 (1.01 to 1.22)c | 0.88 (0.83 to 0.97)c |

| Hydroxychloroquine | −0.31 (−0.98 to 0.37) | 0.010 (−0.38 to 0.40) | 1.01 (0.94 to 1.10) | 1.04 (0.98 to 1.11) |

Outcomes studied include 6-month change in systolic and diastolic BP, risk of a significant increase in BP, and odds of optimal BP. All therapies are compared with methotrexate after matched weighting for the propensity of receiving the therapy. A significant increase in BP is defined as 20-mm Hg increase in SBP or 10-mm Hg increase in DBP. Optimal BP is defined as <130/90 mm Hg.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001.

P < 0.05.

OR indicates odds ratio.

Tumor necrosis factor inhibitor, prednisone, and especially leflunomide initiation were associated with an increased risk of incident hypertension compared with methotrexate in multivariable models (Table 4). Sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine users had similar risk of incident hypertension when compared with methotrexate.

TABLE 4.

Cox Proportional Hazards Model Comparing the Risk of Incident Diagnosis of Hypertension Among Individuals Initiating New Medications for RAa

| Incident Hypertension Total Obs = 6881 Person-Years = 19,583 |

||

|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P | |

| Methotrexate | Reference | — |

| Prednisone | 1.30 (1.08–1.56) | 0.006 |

| Leflunomide | 1.52 (1.21–1.91) | <0.001 |

| TNFi | 1.36 (1.11–1.67) | 0.003 |

| Sulfasalazine | 1.03 (0.78–1.35) | 0.84 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 0.86 (0.69–1.08) | 0.20 |

Adjusted for age, sex, race, BMI, CRP, Rheumatic Disease Comorbidity Index, current smoking, lung disease, interstitial lung disease, diabetes mellitus, any malignancy, lung cancer, CHF, CKD, history of myocardial infarction, disease duration greater than 5 years, ACPA seropositivity, RF seropositivity, concurrent RA drug use, current SBP and DBP, and prior change in SBP and DBP.

In multivariable models (Table 2), factors that were associated with greater increases in BP included female sex, black race, a history of hypertension, concurrent use of sulfasalazine or leflunomide, current smoking, and greater BMI. Factors associated with reductions in BP included greater baseline BP, use of antihypertensives, greater comorbidity score, history of myocardial infarction, history of interstitial lung disease, greater disease duration, and greater increase in BP prior to the course start date. Older age was associated with increases in SBP and reductions in DBP. Recently having stopped methotrexate within the prior 6 months was not associated with subsequent change in SBP or DBP. When included in multivariable models, an increase in BMI (per 1 kg/m2) in the 6 months after RA initiation was associated with greater increases in SBP (B = 1.00 [0.91–1.10]; P < 0.001) and DBP (B = 0.39 [0.32–0.45]; P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first real-world observational study to evaluate actual BP change in the setting of DMARD initiation in a large population of patients with RA. Overall, BP was reduced over 6 months after therapy initiation. Only the use of leflunomide was associated with increases in BP at 3 and 6 months. Even among individuals who did not receive antihypertensives throughout the observation periods, the trend upward in BP observed prior to therapy plateaued after therapy initiation. Overall, this study supports the hypothesis that treatment of RA has beneficial effects on BP. This observation has implications for understanding the biologic effects of the inflammatory disease.9

It is important to note that the changes were small, on average. While this is of interest in understanding the biologic impact of inflammation on BP, the clinical relevance of these observations is arguable. Although the average changes were small, the variation in change is wide, suggesting that some patients might improve dramatically, whereas others will not demonstrate any improvement. Future study to determine which patients may be most likely to demonstrate clinically important improvements in BP with treatment are of interest. In multivariable models, drug-related changes were similar in magnitude to the effects observed for other important risk factors for hypertension such as smoking, greater weight, and comorbid conditions. This suggests that treatment initiation is as important to predicting BP change at 6 months as other well-described clinical risk factors.

Another way to interpret the clinical relevance is to evaluate the number needed to treat. The number needed to treat for methotrexate suggests that for every 23 patients treated, 1 patient will achieve optimal BP at 6 months who otherwise would not have. Thus, a clinically relevant benefit is not common but is certainly not rare.

In contrast to the generally favorable change in BP observed following initiation of other DMARDs, this study corroborates previous evidence suggesting that leflunomide may raise BP and increase the risk of hypertension.10,27–29 Leflunomide use, as compared with use of methotrexate, was associated with a 20% lower odds of achieving optimal BP at 6 months in this study. The mechanism through which leflunomide raises BP is not known. However, others have suggested a potential impact of increased sympathetic tone.29

Overall, other DMARDs were similar to methotrexate in terms of reductions in BP, with somewhat less reduction in BP being observed for TNFi and prednisone compared with methotrexate. This study also suggests that there is a small but statistically significant difference in the change in BP after treatment and an increased 3-year risk of incident hypertension for TNFi use compared with methotrexate. This observation conflicts somewhat with one previous report suggesting no increased risk of hypertension for TNFi compared with methotrexate.10 Overall, the between-drug differences here are modest. It is also important to note that these results do not suggest that TNFi use is expected to raise BP, but rather that the reduction observed with TNFi might be less than that seen with methotrexate. As noted below, it is possible that this may have more to do with its tendency to be used later in the course of the disease.

Surprisingly, prednisone users also demonstrated reductions in BP, although more modest compared with those observed with methotrexate. Compared with methotrexate, there was less improvement in DBP at 6 months, a greater risk of a significant BP increase, and a greater risk of incident hypertension compared with methotrexate. Overall, it seems likely that anticipated direct adverse impacts of initiating prednisone on BP are perhaps generally offset by better control of the chronic inflammatory disease. These data suggest that prednisone use in patients with active RA is not likely to contribute to an adverse impact on BP.

This study identified a number of factors associated with increases in BP among patients with RA who are initiating therapy. Many of these factors are known to correlate with elevated BP, including black race, diagnosed hypertension, current smoking, and greater and increasing BMI. The use of antihypertensives was associated with reductions in BP, as might be expected. In addition, greater comorbidity and specific diagnoses associated with more aggressive BP management were also generally associated with reductions in BP. The confirmation of these anticipated findings provides support for the validity of the noted effects for DMARD initiation. However, associations noted here should be considered hypothesis generating, as they were not the primary focus of the analysis.

Better concurrent management of comorbid conditions, direct effects of DMARDs on other metabolic pathways, improvements in endothelial dysfunction,6 reductions in pain, and improvements in physical activity may all be implicated as explanations for BP improvement with DMARD therapy. Understanding the impact of these pathways is an important next step.

Although administrative data from the VA provide an ideal opportunity to assess actual BP on a large scale, the lack of longitudinal composite disease activity measures and markers of disease severity limits our ability to fully understand the underlying mechanisms (biologic or otherwise) contributing to BP modification. While traditional disease activity measures were not available, the current study is an advance over existing literature by the incorporation of CRP levels from laboratory databases, as well as BMI from vital signs packages. Low availability of CRP in follow-up limited assessment of relationships between improvements in inflammatory activity and BP over time. Despite advances over previous studies by the inclusion of these data points in the analysis, confounding by indication may still be present. For example, some of the relatively greater reduction in BP observed with methotrexate may reflect its tendency to be used as first-line therapy in individuals with more early and active disease. Finally, the approach using administrative data makes it difficult to directly assess medication dose effects or to assess the impact of initial combinations of therapies.

The use of real-world BP measurements and the natural variability in BP over time may have biased the study toward the null. The large sample size is an important strength to overcome this limitation and provide greater generalizability. Finally, this study did not directly assess the potential impact of closer clinical follow-up and greater access to health care in the setting of RA management. This includes a lack of granular assessment of changes to doses of antihypertensive drugs and the medical reasoning for their initiation or lack thereof.

There are a number of important strengths to the current study including (1) the large sample size, (2) the accurate pharmacy algorithms used to define new treatment initiations, (3) the use of actual BP values as an outcome before and after exposure (as opposed to future diagnosis codes alone), and (4) the robust clinical data from the VA electronic medical record, including a biomarker of disease activity (CRP). Thus, this study was able to identify small but potentially important average changes in BP (a quantitative outcome that is variable over time) while simultaneously characterizing risk of incident hypertension (an important clinical outcome) in RA patients initiating DMARDs.

In summary, RA patients who initiate DMARDs tend to demonstrate reductions in BP over the following 6 months that are modest, on average. While most therapies showed similar improvements in BP, leflunomide was associated with a small but significantly greater increase in BP and a greater risk of incident hypertension compared with methotrexate.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

J.F.B. is funded by a Veterans Affairs Clinical Science Research&Development Career Development Award (IK2 CX000955). S.I. is supported by the National Institutes of Musculoskeletal and Skin Disorders (award 1K24AR055259-01). T.R.M. is funded by a Veterans Affairs Merit Award (CX000896) and a grant from NIH/NIGMS (U54GM115458). L.C. is supported, in part, by VA HSR&D IIR 14-048-3. The contents of this work do not represent the views of the Department of the Veterans Affairs or the US Government. This work was also supported by Specialty Care Center of Innovation, Veterans Health Administration, Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citation appears in the printed text and is provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.jclinrheum.com).

REFERENCES

- 1.Van Breukelen-van der Stoep DF, van Zeben D, Klop B, et al. Marked underdiagnosis and undertreatment of hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55:1210–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giles JT, Allison M, Blumenthal RS, et al. Abdominal adiposity in rheumatoid arthritis: association with cardiometabolic risk factors and disease characteristics. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3173–3182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dinh QN, Drummond GR, Sobey CG, et al. Roles of inflammation, oxidative stress, and vascular dysfunction in hypertension. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:406960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison DG, Guzik TJ, Lob HE, et al. Inflammation, immunity, and hypertension. Hypertension. 2011;57:132–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klarenbeek NB, van der Kooij SM, Huizinga TJ, et al. Blood pressure changes in patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis treated with four different treatment strategies: a post hoc analysis from the BeSt trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1342–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Groot L, Jager NA, Westra J, et al. Does reduction of disease activity improve early markers of cardiovascular disease in newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis patients? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54:1257–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramseyer VD, Garvin JL. Tumor necrosis factor-α: regulation of renal function and blood pressure. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2013;304: F1231–F1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaplan MJ. Cardiovascular complications of rheumatoid arthritis: assessment, prevention, and treatment. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2010;36:405–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshida S, Takeuchi T, Kotani T, et al. Infliximab, a TNF-alpha inhibitor, reduces 24-h ambulatory blood pressure in rheumatoid arthritis patients. J Hum Hypertens. 2014;28:165–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desai RJ, Solomon DH, Schneeweiss S, et al. Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Inhibitor Use and the Risk of Incident Hypertension in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Epidemiology. 2016;27:414–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Department of Veterans Affiars. VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure. 2014. Cited 2014. Available at: http://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/vinci/cdw.cfm. Accessed January 24, 2018.

- 12.Cannon GW, Mikuls TR, Hayden CL, et al. Merging Veterans Affairs rheumatoid arthritis registry and pharmacy data to assess methotrexate adherence and disease activity in clinical practice. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63:1680–1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cannon GW, DuVall SL, Haroldsen CL, et al. Persistence and dose escalation of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in US veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:1935–1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baker JF, Sauer BC, Cannon GW, et al. Changes in body mass related to the initiation of disease modifying therapies in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:1818–1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh JA, Holmgren AR, Noorbaloochi S. Accuracy of Veterans Administration databases for a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:952–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aiyer AN, Kip KE, Mulukutla SR, et al. Predictors of significant short-term increases in blood pressure in a community-based population. Am J Med. 2007;120:960–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43:1130–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birman-Deych E, Waterman AD, Yan Y, et al. Accuracy of ICD-9-CM codes for identifying cardiovascular and stroke risk factors. Med Care. 2005;43:480–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bullano MF, Kamat S, Willey VJ, et al. Agreement between administrative claims and the medical record in identifying patients with a diagnosis of hypertension. Med Care. 2006;44:486–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szeto HC, Coleman RK, Gholami P, et al. Accuracy of computerized outpatient diagnoses in a Veterans Affairs general medicine clinic. Am J Manag Care. 2002;8:37–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis LA, Cannon GW, Pointer LF, et al. Cardiovascular events are not associated with MTHFR polymorphisms, but are associated with methotrexate use and traditional risk factors in US veterans with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2013;40:809–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michaud K, Wolfe F. The development of a rheumatic disease research comorbidity index for use in outpatients with RA, OA, SLE, and fibromyalgia (FMS). Arthritis Rheumatol. 2007;56 suppl:S596. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolfe F, Michaud K, Li T, et al. Chronic conditions and health problems in rheumatic diseases: comparisons with rheumatoid arthritis, noninflammatory rheumatic disorders, systemic lupus erythematosus, and fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:305–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mulla ZD, Simons FE. Concomitant chronic pulmonary diseases and their association with hospital outcomes in patients with anaphylaxis and other allergic conditions: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2013;3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.England BR, Sayles H, Mikuls TR, et al. Validation of the Rheumatic Disease Comorbidity Index. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2015;67: 865–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li L, Greene T. A weighting analogue to pair matching in propensity score analysis. Int J Biostat. 2013;9:215–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smolen JS, Kalden JR, Scott DL, et al. Efficacy and safety of leflunomide compared with placebo and sulphasalazine in active rheumatoid arthritis: a double-blind, randomised, multicentre trial. European Leflunomide Study Group. Lancet. 1999;353:259–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strand V, Cohen S, Schiff M, et al. Treatment of active rheumatoid arthritis with leflunomide compared with placebo and methotrexate. Leflunomide Rheumatoid Arthritis Investigators Group. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159: 2542–2550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rozman B, Praprotnik S, Logar D, et al. Leflunomide and hypertension. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:567–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.