Abbreviation

- ED

emergency department

1. INTRODUCTION

The novel coronavirus that results in COVID‐19 has significantly impacted the global healthcare system and economy since first reported in December 2019. 1 Many countries and states have enacted stay‐at‐home orders and implemented social distancing guidelines to mitigate disease transmission. One recent Italian study described delays in seeking paediatric emergency care for fear of COVID‐19 infection, resulting in potentially avoidable intensive care unit admissions and deaths. 2 Emergency department (ED) utilisation for paediatric mental health in the United States has seen dramatic increases over the last several years, with over 1.2 million visits annually. 3 Anecdotally, paediatric and adult EDs have experienced decreased censuses during the pandemic. The objective of this study was to evaluate the overall paediatric ED volume relative to mental health‐specific volume since the Oregon stay‐at‐home order was implemented on 3/23/20.

2. METHODS

This study was performed at a tertiary care children's hospital in Portland, Oregon, from April 1, 2019, to April 29, 2020, following the Oregon stay‐at‐home order on March 23, 2020. Data were obtained from the electronic medical system (EPIC 2019) and internal quality improvement databases. No specific patient data or demographics were obtained that would require institutional review board approval. Paediatric mental health patients were defined in this study using the most common subgroups of patients: suicidal or aggressive. This cohort was identified by chief complaints that included suicidal, suicide attempt, depression, overdose, self‐harm, aggression and violent behaviour. Analysis consisted of simple descriptive statistics. Suicidal patient volumes were separated from aggressive behavioural patient volumes as these are two unique populations.

3. RESULTS

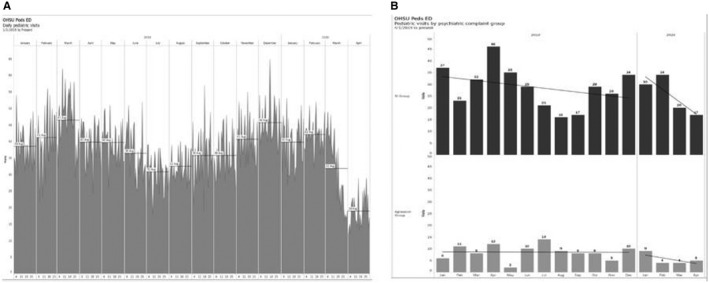

The overall annual paediatric emergency department volume at this single centre was 14,108 patients in 2019. Figure 1A shows that after 3/23/2020 there is a sharp decline to slightly under half the normal volume for late March and early April. Paediatric mental health visits, Figure 1B, show a higher decrease in March and April 2020 after the stay‐at‐home order. April 2020 showed the fewest number of suicidal patients with 16 relative to 46 the same time one year ago, representing a 65.2% drop.

Figure 1.

Paediatric emergency department census. A, Overall paediatric emergency department census. B, paediatric mental health census

4. DISCUSSION

Emergency departments increasingly provide urgent mental health care for youth. 3 This study demonstrates a dramatic decrease in utilisation of a paediatric ED for paediatric mental health following a COVID‐19 stay‐at‐home order. This is in stark contrast to a publication from the same tertiary care centre analysing paediatric mental health presentations to the emergency department in the decade prior. 4 During 2009‐2013, there was a statistically significant increase in presentations which nationally has persisted. 3 Paediatric mental health utilisation is particularly notable given that this group of patients have been shown to have longer lengths of stay and greater overall resource use in a paediatric ED. 5 To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the impact of a COVID‐19 stay‐at‐home order on mental health utilisation in a paediatric ED.

These results raise important questions and have significant implications for research and policy. Most importantly, does the trend of decreased paediatric mental health presentations to EDs reflect decreased paediatric mental health crises? If so, why would this trend occur during a pandemic? A number of factors could be hypothesised to account for this. Stay‐at‐home orders have increased the ability of many caregivers to monitor their children, potentially increasing connectivity and decreasing safety risks, although this clearly varies by household. School closures could be resulting in decreased stress and suicidality, although school settings may also be protective for some youth. Youth and families may be relying more on outpatient mental health and educational supports, averting crises before utilising EDs.

If decreased paediatric ED mental health presentations do not reflect the reality of how children and adolescents are doing, we have cause for concern. Youth and families may simply not be seeking care due to the pandemic, potentially leading to higher acuity and more severe outcomes. If youth are utilising more outpatient mental health supports, are these adequate for their needs? Are other factors at play? Will this trend reverse, and if so, when? These questions highlight the need for better tracking of mental health indicators for youth, on both an outpatient and inpatient level, to help identify which youth are most vulnerable during this time, to develop strategies to support them, and to develop more effective and coordinated systems of care.

Specific work in Oregon aims to transition patients from the ED to outpatient care with promising results and may be an important consideration in the future. Larger scale, national and longitudinal studies will be needed to assess longer term outcomes of these changes in volume and the impact of improved outpatient capacities.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lazzerini M, Barbi E, Apicella A, Marchetti F, Cardinale F, Trobia G. Delayed access or provision of care in Italy resulting from fear of COVID‐19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(5):e10‐e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Burstein B, Agostino H, Greenfield B. Suicidal attempts and ideation among children and adolescents in US emergency departments, 2007–2015. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(6):598‐600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sheridan DC, Spiro DM, Fu R, et al. Mental health utilization in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31(8):555‐559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mapelli E, Black T, Doan Q. Trends in pediatric emergency department utilization for mental health‐related visits. J Pediatr. 2015;167(4):905‐910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]