Abstract

The objective of this study was to examine the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effects of an intervention, Skills to Enhance Positivity (STEP) that aims to increase attention to positive emotions and experiences and to decrease suicidal events. STEP involves four in-person individual sessions delivered during an inpatient psychiatric admission, followed by one month of weekly phone calls and daily text messages with mood monitoring and skills practice. A pilot randomized controlled trial of STEP vs. enhanced treatment as usual (ETAU) was conducted with 52 adolescents. Results indicated that on average 83% of sessions were completed and that on 70% of days, participants engaged with the text-messaging component of the intervention. Acceptability for both in-person and text-messaging components were also high, with satisfaction ratings averaging between good and excellent. STEP participants reported fewer suicide events than ETAU participants (6 vs. 13) after six months of follow-up.

Keywords: Adolescents, Suicidal Behaviors, Positive Affect, Mindfulness, Gratitude, Savoring, Text Message Intervention, Digital Health

Suicide attempts and related behaviors are alarmingly high in adolescents and have been increasing in recent years. Data from high school students in the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance show an increase in the suicide attempt rate from 6.3% in 2009 to 8.6% in 2015 (Kann et al., 2016). The trend is particularly alarming for girls, who have experienced a three-fold increase in suicide deaths since 1999 (Curtin, Warner, & Hedegaard, 2016). Adding to this concern, interventions aimed to decrease suicidal behavior are not particularly effective in adolescents (O’Connor, Gaynes, Burda, Soh, & Whitlock, 2013; Tarrier, Taylor, & Gooding, 2008). Prior interventions for adolescent suicidality have focused on crisis intervention, psychiatric symptomatology, regulating negative affect, and reducing cognitive distortions. Alternative approaches to reduce suicidal behaviors, particularly in adolescents, are warranted.

One alternative approach is to augment treatment with a focus on building resiliency through increasing attention to positive affect. Low levels of positive affect have been found to uniquely contribute to suicide risk in adolescents. In a 6-month follow-up study of adolescent inpatients hospitalized due to suicide risk, low positive affect was a significant prospective predictor of time to suicide events (attempts or readmissions) after controlling for depression severity, anhedonia and childhood sexual abuse (Yen et al., 2013). In a cross-sectional study of over 1000 adolescents, gratitude was associated with lower suicidal ideation and less suicide attempts (Li, Zhang, Li, Li, & Ye, 2012). Low positive affect has also been able to distinguish between suicide ideators from nonideators in older primary care patients, even after controlling for age, gender, depression, negative affect, illness burden, activity, sociability, cognitive functioning, and physical functioning (Hirsch, Duberstein, Chapman, & Lyness, 2007).

Nonetheless, few positive psychology interventions have specifically been applied to patients with suicidal behavior. Two meta-analyses of positive psychology interventions found that these interventions have small to moderate effects in enhancing well-being and decreasing depressive symptoms (Bolier et al., 2013; Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009). However, the vast majority of these interventions were with nonclinical populations, with nearly half of these studies conducted on college students. Only a handful of studies recruited from clinical or hospital settings (Emmons & McCullough, 2003; Fava, Rafanelli, Cazzaro, Conti, & Grandi, 1998; Fava et al., 2005; Seligman, Rashid, & Parks, 2006). The few studies conducted with suicidal populations (not included in the meta-analyses) have yielded mixed findings. One recent study of 201 inpatient adults randomized to a 7-day program of either gratitude diary or food diary found significant between group differences on suicidal ideation, psychological pain, hopelessness and optimism, favoring those in the gratitude condition (Ducasse et al., 2019). However, in another study in which 65 adult inpatients were randomized to positive psychology exercise (e.g., gratitude letter) vs. a cognition focused intervention (e.g., recalling daily events) found that contrary to hypothesis, those randomized to the cognition focused intervention had significantly greater improvement in depression, suicidal ideation, optimism, and gratitude, compared to the positive psychology intervention (Celano et al., 2017). No positive psychology intervention to our knowledge have been piloted in suicidal adolescents.

Thus, we developed the Skills to Enhance Positivity (STEP) program to provide adjunctive support to adolescents admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit due to suicide risk (Yen et al., 2017). STEP is based on Fredrickson’s empirically-supported Broaden and Build theory, which asserts that one function of positive affect may be to broaden attentional scope to help individuals be more open to novel stimuli and social supports, which in turn, broadens and builds psychological and social resources (Fredrickson, 2001; Fredrickson & Branigan, 2005; Fredrickson, Cohn, Coffey, Pek, & Finkel, 2008; Fredrickson & Joiner, 2002; Fredrickson & Losada, 2005; Fredrickson, Tugade, Waugh, & Larkin, 2003). Laboratory studies have shown that inducing positive emotions results in improved problem solving and increased social support (Fredrickson et al., 2003); both of these areas are critical to suicide prevention. Thus, based on Fredrickson’s Broaden and Build theory of positive emotions, we developed an intervention that focuses on teaching specific exercises, such as mindfulness, gratitude, and savoring, that may increase attention to positive affect and experiences which may otherwise be discounted, with the goal of decreasing suicidal behaviors.

STEP also borrows heavily from preceding positive psychology interventions, such as Seligman’s positive psychotherapy (PPT) (Seligman et al., 2006), by including various gratitude and savoring exercises. However, in STEP, the focus is not on happiness, optimism, or meaning, which may feel unattainable or invalidating to patients in acute distress, but rather on increasing attention and awareness to positive emotions and experiences that may easily get discounted by the cognitive constriction that often accompanies a depressive episode. Furthermore, the focus on specific exercises that can increase attention and awareness (i.e., psychoeducation on functions of emotions, mindfulness, gratitude, and savoring) is more compatible with acceptance-based approaches to treating depression, which have become increasingly more common.

STEP includes an in-person phase to deliver positive affect exercises and strategies and to personalize the intervention, as well as a remote delivery phase of weekly phone calls and daily text messages to extend the reach of the intervention into participants’ home environments. A text-messaging enhanced intervention can potentially reach segments of the clinical population that may be less inclined or able to remain engaged in in-person outpatient therapy after discharge from higher levels of care. Since texting is a low cost and preferred form of communication for adolescents (Lenhart et al., 2015; Ranney, Choo, Spirito, & Mello, 2013; Ranney et al., 2016), delivering skills coaching and mood monitoring via texting may have the potential to provide adolescents with daily support to help them remain engaged in treatment, increase exercise and skills use and generalization to their natural environments, and lend providers important information regarding daily risk levels. STEP delivered six text messages of mood assessment and one skill practice daily, with the objective of reinforcing brief and daily practice, akin to an exercise model.

An earlier report described the development of STEP (Yen et al., 2017). In the present report, we describe results from a pilot randomized clinical trial examining feasibility, acceptability, and some preliminary outcomes of STEP versus an enhanced treatment as usual (ETAU) condition.

Methods

Participants

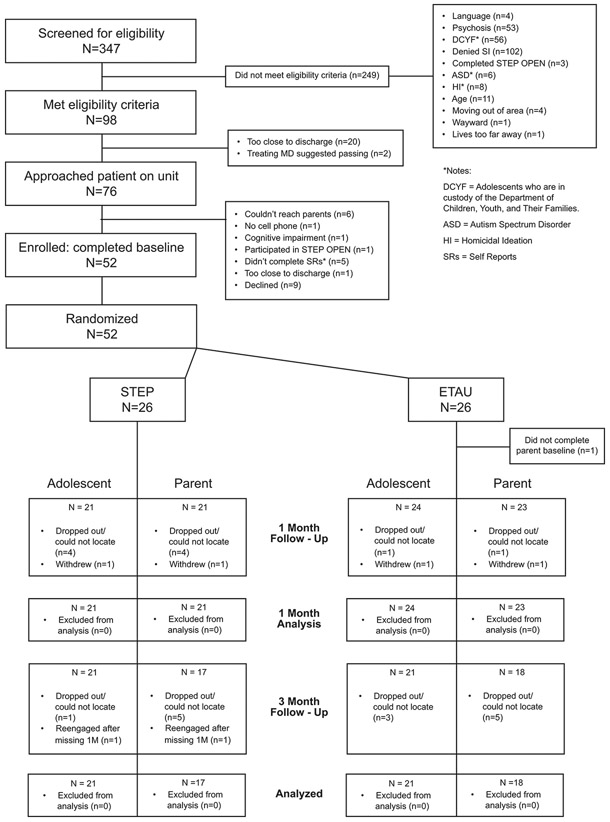

Participants were 52 patients recruited from an adolescent psychiatric inpatient unit in the Northeast region of the United States, who were admitted due to concerns of suicide risk (i.e., suicide attempt or suicidal ideation). Recruitment occurred from March 2015 to January 2016. Of the 98 participants who were deemed potentially eligible based on chart review, 76 patient/parent pairs were approached, and of those, 52 (68%) enrolled and signed parental consent and adolescent assent (see Figure 1 for flow of participants through study procedures).

Figure 1.

STEP-RCT CONSORT Diagram

Procedures

Potential participants were initially identified through chart review. Medical record notes from consecutive admissions were reviewed, and prospective participants were approached if the precipitating event from their current admission was reported to be a suicide attempt or suicidal ideation. To be eligible, adolescents had to be between the ages of 12 to 18, living at home, English speaking, and have access to text messaging. Participants were not eligible to participate if they were diagnosed with a psychotic disorder or exhibited cognitive or intellectual disabilities that precluded understanding of study materials. Finally, adolescents who were a ward of the state were not eligible.

If participants were eligible and interested, parents were informed of the study procedures, and parental consent and adolescent assent were obtained. For those who were 18 years old, informed consent was obtained from the patient. In addition, release of information forms for all area emergency departments were obtained so investigators could ascertain whether any re-admissions due to suicide risk occurred during the follow-up interval, mitigating loss of data due to attrition. Following consent and assent, participants were administered the baseline assessment protocol and then randomized. All procedures were approved by the hospital’s Institutional Review Board.

Randomization was stratified by sex assigned at birth and occurred in variable blocks of four and six. Two research assistants worked on the research protocol for the duration of the study, one of whom was blind to randomization and conducted all adolescent follow-up assessments. Participants were randomized to either STEP or ETAU in a 1:1 ratio, which resulted in 26 participants in each intervention group. Although this sample size is not adequately powered to find significant between group effects, it is appropriate for a Stage 1 Clinical Trial (Rounsaville, Carroll, & Onken, 2001).

Adherence and Competency.

The Principal Investigator trained a psychology post-doctoral fellow with a Ph.D. in counseling psychology to conduct the STEP intervention. Training included review of the treatment manual, listening to audio-recordings of the PI conducting the intervention, and individual meetings with the PI weekly. Supervision involved the PI reviewing recorded sessions and providing feedback. Ten percent of sessions were independently rated by two trained coders for adherence to the treatment protocol and competency of the interventionist, using a yes/no scale to evaluate adherence to treatment protocol, as well as a 7-point Likert-style scale (0 = “poor” to 6 = “excellent”) to evaluate competency. For adherence, there was 96% agreement between coders on whether protocol components were administered, and on average 97% of the expected elements of the intervention were delivered (range 95–100%). For competency, all treatment components were rated above the expected level of 3 (“satisfactory”), with mean ratings for components ranging from 4.50 to 6.00 (across all components, M = 5.41, SD = 0.13).

Measures

Baseline assessments occurred on the inpatient unit prior to randomization. A post-treatment assessment (after one month of daily text messages) was conducted with adolescent participants and parents separately. An in-person follow-up assessment, which took place three months post-treatment, was also conducted. In addition, participants and parents received a six-month (post-discharge) follow-up phone call to assess for the primary clinical outcomes of the study, i.e., suicide attempts and hospital readmissions. Participants and parents were each compensated $40 for completion of the baseline assessment, $60 for completion of the 1-month post-treatment assessment, $50 for completion of the 3-month follow-up assessment, and $10 for completion of the follow-up phone call at six months post-discharge. If participants and parents completed the post-treatment and/or follow-up assessments within one month of their due date, they received an additional $10 for each on-time assessment, with a possible total of $180 for the entire battery of assessments. The ETAU participants received the same assessment schedule and protocol as those randomized to STEP.

At baseline only, demographic information including sex, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, living arrangements, parents’ level of education and income, and clinical information such as treatment history, abuse history, and family history of psychiatric disorders, were assessed using the KSADS-PL Screen Interview (Kaufman et al., 1997). Patients’ psychiatric diagnoses were ascertained through medical chart review.

Feasibility and Acceptability.

Feasibility of recruitment and randomization, defined by the percentage of eligible participants and parents who consented to participation was assessed to inform future trials. Feasibility of the intervention delivery was based on the percentage of in-person session completed, and percentage of days in which participants engaged with the text messaging protocol, i.e., percent days in which they responded to any of the text prompts, and percent days in which they responded to all of the text prompts. To assess acceptability, a modified version of the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ) was administered to adolescent participants and parents (Attkisson & Zwick, 1982). Modifications were made to examine specific components of the STEP intervention including modality (i.e., individual session, family session, phone sessions, text messaging) and content (i.e., functions of positive affect, mindfulness, gratitude, and savoring). Responses were on a 4-point Likert scale with higher scores corresponding to greater satisfaction. Cronbach’s alpha of the modified CSQ based on the present sample ranged between 0.80 (adolescent post-treatment) to 0.94 (parent post-treatment).

Attention Bias Assessment (Positive Affect).

Participants completed dot probe tasks to assess attentional bias toward positively and negatively valenced stimuli (MacLeod, Mathews, & Tata, 1986). The first task presented happy/neutral and sad/neutral face pairs. The second task presented positive/neutral and negative/neutral valenced word pairs. In each trial, a fixation cross was presented (1000ms), followed by the face/word pair display with one stimulus on the right side of the screen and one on the left (1500ms), followed by the probe (* or **). The probe remained on screen until participants indicated how many stars were present by pressing either the number ‘1’ or ‘2’ located on the letters ‘j’ or ‘l’ on the keyboard. Response was followed by a varying inter-trial interval (750ms or 1250ms). Participants sat 60 cm from the 12-inch wide monitor with a resolution of 1440 X 900. Vertical angle was approximately 4 degrees.

For each task, participants completed 96 trials. Emotional location (right/left), probe location (right/left), probe type (* or **), and actor/word (valence or neutral) were fully counterbalanced in presentation. In each task (faces and words), the valence was blocked such that participants first completed the positive vs. neutral stimulus pairs, followed by the negative vs. neutral stimulus pairs.

The face stimuli were photographs of 6 different individuals (3 male, 3 female) taken from the NimStim stimulus set (Tottenham et al., 2009). Two different pictures of each individual, depicting happy and neutral (or sad and neutral) expressions, were selected in part based on Joorman and colleagues (2007) (Joormann & Gotlib, 2007) prior work. Faces were 128 X 198 pixels, with inner edges separated by 198 pixels. The word stimuli were selected from a word set normed on high school students (Doost, Moradi, Taghavi, Yule, & Dalgleish, 1999). Six positive words and six negative words were selected, as well as neutral words matched on frequency and length. Words were presented in 28-point Courier New font, inner edges separated by 198 pixels. Participants’ reaction time to identify the probe and accuracy were recorded. Standard attention bias scores were calculated such that higher scores reflect more attention toward the emotional stimuli. For example, “happy face bias score” = reaction time on trials on which probe replaced the neutral face, minus the reaction time on trials in which probe replaced the happy face. We eliminated inaccurate trials and applied a Winsor approach to eliminate reaction time outliers for each assessment and for each dot probe task (faces/words) and block (positive/ negative), following recent guidelines for enhancing the reliability of the dot probe task (Price et al., 2014).

Self-report of Positive Affect.

To obtain subjective indices of positive affect, we administered the Modified Differential Emotions Scale (mDES). The 19-item mDES assesses short-term state positive and negative emotions, along a 5-point Likert scale. Each item consists of three related terms to describe a particular discrete emotion (e.g., glad, happy, joyful). Participants were asked to rate each set of emotions based on how they were feeling “right now”. The Positive Emotions subscale is a composite of 10 items, while the Negative Emotions subscale is a composite of 9 items. The scale has psychometric support (Fredrickson et al., 2003) and in the present sample, Cronbach’s α was = .855 and .915 for the positive and negative emotions subscales respectively. The full version was administered at baseline, post-treatment, and follow-up; six items from the mDES were administered as mood monitoring prompts in the daily text messaging protocol for the STEP participants.

Suicide Events and Ideation.

Suicidal behavior characteristics were assessed at baseline, post-treatment, and follow-up intervals using the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) (Posner, Oquendo, Gould, Stanley, & Davies, 2007), a semi-structured interview that assesses for frequency and intensity of behaviors including suicide attempts, aborted and interrupted attempts, preparatory acts, and suicidal ideation, in the week prior and lifetime. The C-SSRS was administered to both adolescent and parent; each interview was reviewed in consensus meetings with raters and the research team. Where there were discrepancies between child and parent ratings, consensus ratings were made based on all available data including hospital admission notes.

The main clinical outcome in this study, suicide events, was operationalized as either a suicide attempt or emergency intervention to intercede before an attempt occurred. Suicide events were assessed using all available information, which included the C-SSRS, a treatment history interview for follow-up, the 6-month follow-up phone call, and medical records.

Suicidal ideation was also assessed using the C-SSRS. Active suicidal ideation was operationalized as suicidal ideation with either intent, method or plan. Assessments at baseline probed for the week prior to baseline, and the worst week during their lifetime. Assessments during follow-up probed for the most recent week, and the worst period since their last assessment (either baseline or post-treatment).

Secondary Clinical Outcomes.

Secondary clinical outcomes include depression and functional impairment. Depression was assessed by the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) administered to both the adolescent and the parent (about child). The BDI-II is a widely used 21-item measure with excellent psychometric properties (Dozois, Dobson, & Ahnberg, 1998). Cronbach’s α in the present sample was 0.90 in adolescents and 0.89 in adults. The Columbia Impairment Scale (CIS) is a 13-item scale that derives a total score based on functioning in children and adolescents in four areas: interpersonal, psychopathology, school/work, and leisure (Bird, Shaffer, Fisher, & Gould, 1993). The CIS also has good psychometric properties (Bird et al., 1996); Cronbach’s α in the present sample ranged from 0.74 in adolescents to 0.82 in parents.

Intervention Conditions

STEP Intervention

The STEP intervention is described in detail elsewhere (Yen et al., 2017). There were two phases of STEP, an in-person phase consisting of three individual sessions and one family session delivered on the inpatient unit or shortly after discharge, followed by a remote-delivery phase, which consisted of one month of daily text messaging and weekly phone calls to facilitate practice of mood monitoring and positive affect exercises.

STEP provides psychoeducation on the function of positive emotions and three sets of exercises to increase attention to positive affect: mindfulness meditation, gratitude, and savoring. Psychoeducation was used to explain the rationale of the intervention, specifically the function of positive affect, and to increase buy-in on the importance of attention and awareness. Mindfulness meditation was introduced to enhance mood monitoring and attentional awareness. Gratitude and savoring exercises were taught to increase attentional awareness to positive affect and experiences. Participants were introduced to three ways to practice each of the three skill sets: 1) mindfulness meditation (i.e., breathing mindfulness exercise, compassion meditation, mantra meditation); 2) gratitude (i.e., three good things, gratitude expression, random acts of kindness); and 3) savoring (i.e., sharing good things, mindfully attending to positive moments, journaling of positive experiences).

In-person Phase.

The in-person sessions were completed on the adolescent inpatient unit during the participants’ hospital admission. As the STEP program is adjunctive, all participants received usual care on the inpatient unit, which included individual sessions with the psychiatrist and therapy groups throughout the day. Based on a prior similar experience (S. Yen et al., In press) we structured the program such that the majority of the intervention content (e.g., psychoeducation, rationale, exercises) was delivered in the first two adjunctive in-person sessions. In general, sessions ranged between 30–60 minutes. As sessions were delivered on the inpatient unit, they were designed to maximize flexibility such that if not all of the content were delivered in one session, it would be delivered in the following session.

Session 1 focused on building rapport and assessment of participants’ suicide risk and protective factors, including a discussion of the precipitating factors to their admission. In Session 1, interventionists also provided psychoeducation on the functions of positive and negative affect, the importance of both, and the rationale for the STEP program.

In Session 2, three sets of strategies (mindfulness meditation, gratitude, and savoring) and specific exercises within each strategy were introduced (see (Yen et al., 2017) for additional information regarding strategies and exercises). Participants selected at least one exercise from each set of strategies to practice. The interventionist practiced these exercises with the participant and asked them to practice each of their selected exercises the next day.

Session 3 focused on reviewing the exercises selected in the prior session and whether the participant was able to do the exercise independently, and identifying any anticipated obstacles to practicing these exercises in their home environment. If exercises were not practiced, the interventionist guided the participant through another practice. If an exercise did not appear to be working, participants were encouraged to try a different one, with an explanation that there is individual variability in the effectiveness of exercises and that there are multiple ways of achieving one’s goal. Finally, the interventionist reviewed with the participant what they should expect during the remote delivery phase of the intervention.

Session 4, the family session, was designed to provide the parent with an overview and rationale of the program and to enlist their support to reinforce practice of the positive affect exercises.

Remote-Delivery Phase.

The remote delivery phase of STEP began the day after discharge. Daily password-protected text messages were sent through an automated system, at a time of day selected by the study participant, for one-month post-discharge. The first set of messages asked the participant to rate their mood on a 5-point Likert scale (e.g., “How glad, happy, joyful, do you feel RIGHT NOW? Enter any # from 1 to 5 (1 = not at all, 5 = extremely)”), followed by a request for the participant to select the type of exercise (i.e., mindfulness meditation, gratitude, or savoring) that they would like to practice (“Choose the type of message you would like to receive right now: 1 = mindfulness; 2 = gratitude; 3 = savoring”). In response, the participant received an exercise to practice (e.g., “share something positive with a friend or family member”). Participants were also asked if they had practiced a positive affect exercise the preceding day. If the participant did not respond to the daily text query after 30 minutes, a random exercise practice reminder would be automatically sent from a bank of text messages. Therefore, participants always received a text message reminder to practice a positive affect exercise regardless of whether or not they responded to any of the text messages. STEP interventionists logged on to the text-messaging portal to review responses on a daily basis. Responses which were outside of the expected range of numeric values (e.g., any non-numerical entry for mood ratings and exercise selection) or that were of particular concern (e.g., text messages indicating distress), prompted a telephone call to the participant and/or parent. In addition to the daily text messages, weekly phone calls by the interventionist were scheduled to check in on exercise practice and, if necessary, to guide any adjustments to their practice. After one month of daily text messages, participants were given the option to extend text messages on a tapered schedule of three times per week for an additional three months.

Enhanced Treatment-As-Usual

All patients discharged from the inpatient unit were referred to follow-up psychiatric care (e.g., intensive outpatient program, appointment with a therapist and/or psychiatrist). Participants randomized to the enhanced treatment-as-usual (ETAU) received daily text messages for one month on health habits (e.g., “Reminder: Most teenagers need at least 7 to 9 hours of sleep”) to control for attention received through text messaging, but they did not receive mood monitoring as that is an active intervention that overlaps with STEP. They also did not receive the adjunctive in-person sessions, the family session or phone calls.

Data Analysis Plan

As this is a treatment development pilot study, it is not sufficiently powered for hypothesis testing or to estimate an effect size (Leon, Davis, & Kraemer, 2011). The goal of a treatment development pilot study is mainly to assess feasibility and acceptability of the intervention. Thus, descriptive data is presented on the feasibility of recruitment, randomization, and the intervention protocol, as well as acceptability operationalized as means and standard deviations for satisfaction items, with mean satisfaction ratings 3 (“good”) or higher (per each item), defined as good acceptability. Additionally, we will provide descriptive statistics on clinically meaningful outcomes such as number of participants who experienced suicide attempts, suicide events (a composite measure of suicide attempts and emergency intervention), or active suicide ideation over the six-month follow-up interval.

While a pilot study does not provide a meaningful effect size estimates, it has become standard to report on effect sizes even in pilot trials. Thus, for normally distributed clinical scales, we will conduct linear regression analyses, with treatment condition as the independent variable and covarying for the standardized baseline value of that scale, to obtain effect sizes and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals.

However, data from the attentional bias task will be analyzed per usual convention for these tasks. Thus, data were subjected to repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with treatment group (STEP vs ETAU) as the between-subjects factor and the following within-subjects factors: time (baseline, post-treatment, and 3 month follow-up), stimulus type (faces, words), and valence (positive, negative).

Results

Table 1 presents the demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample. Participants were between the ages of 12–18 (M = 15.63; SD = 1.47), predominantly female (69.2%) and White (76.9%). Nearly half had a gross annual family income of less than $50,000. About half reported they were LGBTQ and about one-third a racial or ethnic minority. Approximately half of our participants reported a prior psychiatric hospitalization, a lifetime suicide attempt, and a history of abuse. The large majority were diagnosed with a mood disorder.

Table 1:

Sample Participant Characteristics.

| Total Sample (n=52) | STEP Group (n=26) | ETAU Group (n=26) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean (SD) or Frequency (%) | Mean (SD) or Frequency (%) | Mean (SD) or Frequency (%) |

| Demographic Characteristics at Baseline | |||

| Age | 15.63 (1.47) | 15.69 (1.72) | 15.58 (1.21) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 16 (30.8%) | 8 (30.8%) | 8 (30.8%) |

| Female | 32 (61.5%) | 14 (53.8%) | 17 (65.4%) |

| Transgender | 4 (7.7%) | 3 (11.5%) | 1 (3.8%) |

| Sexual Orientation | |||

| Gay/ Lesbian | 2 (3.8 %) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (7.7%) |

| Bisexual | 16 (30.8%) | 8 (30.8%) | 8 (30.8%) |

| Heterosexual | 25 (48.1%) | 12 (46.2%) | 13 (50.0%) |

| Other | 9 (17.3%) | 6 (23.1%) | 3 (11.5%) |

| Parental Income ($50,000+) | 23 (50.0%) | 11 (47.8%) | 12 (52.2%) |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic or Latino) | 13 (25.0%) | 6 (23.1%) | 7 (26.9%) |

| Race | |||

| Black or African American | 2 (3.8%) | 1 (3.8%) | 1 (3.8%) |

| White | 40 (76.9%) | 19(73.1%) | 21 (80.8%) |

| Other | 10 (19.2%) | 6 (23.1%) | 4 (15.4%) |

| Clinical Characteristics At Baseline | |||

| Lifetime Suicide Attempts | 27 (51.9%) | 15 (57.7%) | 12(46.2%) |

| Any History of NSSI | 50 (96.2%) | 26 (100.0%) | 24 (92.3%) |

| Prior Hospitalization | 25 (48.1%) | 14 (53.8%) | 11(42.3%) |

| Age of 1st Hospitalization | 14.62 (2.15) | 14.42(2.4) | 14.81(1.9) |

| Any Past Abuse* | 29 (55.8%) | 10 (38.5%) | 19 (73.1%) |

| Childhood Sexual Abuse | 9 (17.3%) | 5 (19.2%) | 4 (15.4%) |

| Number of Diagnoses at Baseline | 1.88 (1.08) | 2.0 (1.10) | 1.77 (1.07) |

| Any Mood Disorder | 48 (92.3%) | 24 (92.3%) | 24 (92.3%) |

| Any Anxiety Disorder | 23 (44.2%) | 12 (46.2%) | 11 (42.3%) |

| Any Trauma Disorder | 2 (3.8%) | 1 (3.8%) | 1 (3.8%) |

| Substance Use Disorder | 8 (15.4%) | 6 (23.1%) | 2 (7.7%) |

Notes: There were no significant differences on any demographic or clinical characteristics between treatment groups except for any history of abuse (χ2 = 6.32; p = 0.01).

Any Past Abuse = Any past history of sexual, physical and/or emotional abuse.

Feasibility

As 68% of those approached were enrolled and none refused randomization, recruitment and randomization appears to be feasible. Twenty-six participants were randomized to each group but one from each group dropped out immediately after completion of the baseline assessment. Thirty-six participant/parent pairs (69%) completed all follow-up assessments. Assessment data were collected through multiple modalities (i.e., in-person computer task, interviews, self-report instruments, six-month follow-up phone call, chart reviews). This resulted in different sample sizes across instruments and time points. All adolescents and 98% of parents completed all components of the baseline assessment, 87% of adolescents and 91% of parents completed all components of the post-treatment assessment, and 77% of adolescents and 74% of parents completed all components of the follow-up assessment. There were no significant differences in attrition between treatment groups. Of the 26 participants that were randomized to STEP, 96% completed in-person sessions 1 and 2, 85% completed session 3, and 65% completed session 4 (family session). The reason for incomplete sessions was always due to the participant being discharged from the inpatient unit. However, participants and parents were open to continuing with the remote delivery phase of the intervention.

With regard to the remote delivery phase, 60% of telephone sessions were completed, with 24 out of 25 (96%) participants engaging in any phone sessions. All participants engaged in the text messaging intervention. The treatment group had a daily response rate of 70% (i.e., responded to at least one prompt), and 58% of text messaging sessions were completed (i.e., responded to every prompt for each day). The text-message response rate to at least one prompt was significantly higher for the STEP group (70%) than the ETAU group (49%) (p = 0.038). Also, 14 (54%) of the STEP participants opted for the text messaging extension in which we offered text messages to continue in a tapered schedule of three times per week for three additional months.

Acceptability

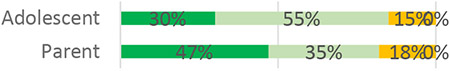

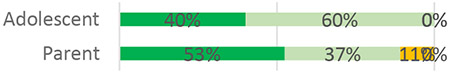

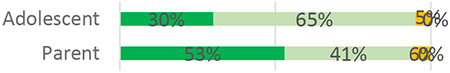

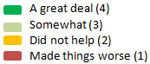

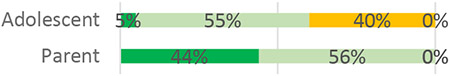

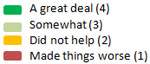

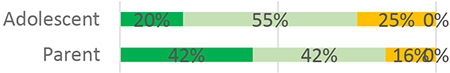

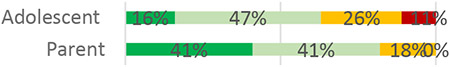

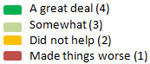

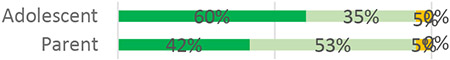

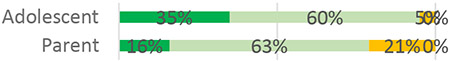

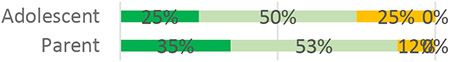

STEP had high acceptability ratings from adolescents and parents at both post-treatment and follow-up, with the vast majority rating the quality of services as good or excellent (100% parents and 85% adolescents at 1-month post-treatment, and 85% parents and 82% adolescents at 3-month follow-up; see Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient and Parent Satisfaction with STEP.

| Post Treatment | Follow-Up | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question | Response Options | Mean (SD) | Ratings of Services | Mean | Ratings of Services |

| How would you rate the quality of services you received? |  |

3.35 (0.75)A 3.63 (0.496)P |

|

3.15 (0.67)A 3.29 (0.77)P |

|

| How helpful was it to learn about the possible functions of positive emotions? |  |

3.40 (0.50)A 3.42 (0.69)P |

|

3.25 (0.55)A 3.47 (0.62)P |

|

| How helpful was it to have a joint parent and adolescent meeting to review the exercises? |  |

2.95 (0.69)A 3.37 (0.68)P |

|

2.65 (0.59)A 3.44 (0.51)P |

|

| How helpful was it to have weekly phone calls? |  |

2.95 (0.69)A 3.26 (0.73)P |

|

2.68 (0.89)A 3.24 (0.75)P |

|

| How helpful was it to have the text messages? |  |

3.30 (0.80)A 3.26 (0.65)P |

|

3.20 (0.89)A 3.35 (0.49)P |

|

| How helpful were the mindfulness exercises? |  |

3.55 (0.61)A 3.37 (0.597)P |

|

3.50 (0.61)A 3.18 (0.73)P |

|

| How helpful were the gratitude exercises? |  |

3.30 (0.57)A 2.95 (0.62)P |

|

3.00 (0.73)A 3.24 (0.66)P |

|

| How helpful were the savoring exercises? |  |

3.25 (0.79)A 3.00 (0.75)P |

|

3.10 (0.72)A 3.18 (0.73)P |

|

| In an overall, how satisfied are you with the service you have received? |  |

3.60 (0.598)A 3.68 (0.58)P |

|

3.55 (0.51)A 3.59 (0.62)P |

|

Note: Percentages based on valid responses. STEP = Skills to Enhance Positivity.

= Adolescent

= Parent

With regard to the specific modalities through which the intervention was delivered, text messaging was rated most highly with the majority reporting that the text messages were either somewhat or a great deal helpful (range: 70% adolescents at 3-month follow-up – 100% parents at 3-month follow-up). The phone calls were rated as less helpful (range: 63% adolescents at 3-month follow-up – 84% parents at 1-month post-treatment), with two adolescents reporting at follow-up, that the calls made things worse. The acceptability of the joint adolescent-parent in-person session was variable; parents reported them to be much more helpful (89% at 1-month post-treatment and 100% at 3-month follow-up) compared to adolescents (75% at 1-month post-treatment and 60% at 3-month follow-up).

With regard to the intervention content, each of the four main content areas of psychoeducation on the functions of positive affect, mindfulness meditation, gratitude and savoring were highly rated by adolescents and parents at both post-treatment and follow-up. Specific breakdown by group and assessment is depicted in Table 2. Data from the daily intervention indicate that based on 400 days of complete responses, on 55% of days participants requested a mindfulness practice, 20% of days in which gratitude was the preferred exercise, and 25% of days in which savoring was requested.

Dot Probe Attention Bias Assessment

Accuracy was high for all assessment points and tasks on the Dot Probe Attention Bias task (97% - 99%). Following reaction time trimming procedures, we removed four participants from analyses due to having too few reaction times per trial type (due to either extreme errors or reaction times). Thirty-nine participants had complete and high-quality dot probe data at all three assessment points.

The ANOVA did not reveal any significant interaction effects involving treatment and time. Although this overall 4-way interaction was not significant, we explored whether there were treatment X time interactions within any of the 4 task blocks (happy faces, sad faces, happy words, sad words), as we were specifically interested in the effect size for positive valence stimuli, given the focus of the intervention. For happy words, this analysis revealed a time X treatment interaction, F(1.45,68) = 3.55, p = .050, (Greenhouse-Geisser corrected p-value). Groups did not differ at baseline or immediately post treatment, but the STEP group showed more attention biased toward happy words at the 3-month follow-up compared to the ETAU group, t(34) = 2.06, p = .048, η2 = .04. There was no significant time X treatment interaction for happy faces, sad faces, or sad words (p’s > .2).

Positive Affect Measure

Table 3 depicts means and standard deviations for scores from the MDES, positive and negative subscales, and Table 4 depicts the estimated effect sizes and corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Mean scores on the positive subscale was quite stable across time for both STEP and ETAU. Both groups experienced a decrease in reporting of negative emotions after baseline, though there are no observable differences between groups.

Table 3.

Means, standard deviations on self-report and parent-report assessments by time and intervention condition.

| STEP | ETAU | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Post-Tx | Follow-up | Baseline | Post-Tx | Follow-up | |||||||

| N | M (SD) | N | M (SD) | N | M (SD) | N | M (SD) | N | M (SD) | N | M (SD) | |

| mDES Pos | 26 | 1.95 (0.72) | 21 | 1.95 (0.60) | 21 | 1.96 (0.78) | 26 | 2.05 (0.68) | 24 | 2.21 (0.89) | 21 | 2.08 (0.82) |

| mDES Neg | 26 | 2.54 (1.06) | 21 | 1.73 (0.97) | 21 | 1.74 (0.73) | 26 | 2.39 (0.99) | 24 | 1.80 (0.82) | 21 | 1.66 (0.68) |

| BDI-A | 26 | 34.71 (11.12) | 21 | 21.52 (17.89) | 21 | 21.05 (17.24) | 26 | 34.63(12.56) | 24 | 23.25 (14.90) | 21 | 19.67 (12.56) |

| BDI-P | 24 | 28.67 (13.06) | 21 | 11.86 (11.35) | 21 | 11.88 (10.90) | 22 | 30.29 (8.31) | 23 | 21.52 (11.34) | 18 | 17.65 (12.56) |

| CIS-A | 26 | 24.38 (7.65) | 21 | 14.86 (11.69) | 21 | 15.57 (8.89) | 26 | 25.08 (9.44) | 24 | 18.71 (11.53) | 21 | 15.62 (9.33) |

| CIS-P | 24 | 25.79 (10.14) | 21 | 17.33 (10.21) | 17 | 13.82 (7.23) | 22 | 26.68 (9.17) | 23 | 20.88 (7.82) | 18 | 19.8 (8.9) |

Notes. mDES Pos = Modified Differential Emotions Scale, Positive Emotions; mDES Neg = Modified Differential Emotions Scale, Negative Emotions; BDI-A = Beck Depression Inventory, Adolescent Report; BDI-P = Beck Depression Inventory, Parent Report of Child; CIS-A = Columbia Impairment Scale – Adolescents; CIS-P = Columbia Impairment Scale – Parents Report of Child.

Table 4.

Effect sizes and confidence intervals by time.

| Post-Tx | Follow-up | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohen’s d | 95% CI | Cohen’s d | 95% CI | |

| mDES Pos | .13 | −0.42, 0.68 | −.01 | −0.59, 0.56 |

| mDES Neg | .18 | −0.42, 0.78 | −.06 | −0.70, 0.58 |

| BDI-A | .11 | −0.41, 0.63 | −.12 | −0.63, 0.40 |

| BDI-P | .76 | 0.21, 1.30 | .42 | −0.27, 1.11 |

| CIS-A | .31 | −0.15, 0.77 | .05 | −0.55, 0.65 |

| CIS-P | .42 | −0.05, 0.89 | .79 | 0.20, 1.38 |

Notes. mDES Pos = Modified Differential Emotions Scale, Positive Emotions; mDES Neg = Modified Differential Emotions Scale, Negative Emotions; BDI-A = Beck Depression Inventory, Adolescent Report; BDI-P = Beck Depression Inventory, Parent Report of Child; CIS-A = Columbia Impairment Scale – Adolescents; CIS-P = Columbia Impairment Scale – Parents Report of Child.

Mood responses based on the six mDES items delivered as part of the daily intervention suggested that in 400 total days of full reporting (58% of surveyed days), 84% of STEP participants reported more days in which their positive emotions outweighed their negative emotions. ETAU did not receive daily mDES items as they were conceptualized as part of the mood monitoring intervention.

Clinical Outcomes

Over 6 months of follow-up, five participants in the STEP condition (19%) and ten participants in the ETAU condition (38%) had a suicide event. With regard to total number of events, six events were reported among STEP participants and 13 events were reported among ETAU participants. The frequency counts were too low for statistical testing but this corresponds to a small to medium effect size ϕ of .21. At baseline, 80.8% of STEP participants and 69.2% of ETAU participants reported active suicidal ideation in the week preceding hospitalization. The percentages for the worst week during follow-up dropped for both groups, with 31.8% in STEP vs. 50% in ETAU.

Secondary Clinical Outcomes

Table 3 depicts means and standard deviations for both adolescent self-report and parent report of adolescents on depression (BDI) and impairment (CIS); Table 4 depicts estimated effect sizes and corresponding 95% CI. With respect to parent ratings about their adolescent’s depression, a linear regression model found a significant effect for treatment condition (favoring STEP) in predicting post-treatment BDI after covarying for baseline BDI (t = 2.78; p = .008), corresponding with a medium to large effect size (Table 4). This effect was no longer significant at follow-up. There were no statistically significant differences on the adolescent self-report on the BDI.

With regard to parents’ ratings about their adolescent’s impairment, measured by the CIS, there were no significant between group differences at post-treatment. However, at follow-up, a linear regression model found a significant effect for treatment condition favoring STEP (t = 2.73; p = .01) corresponding with a medium to large effect size (Table 4). There were no statistically significant differences on the adolescent self-report on the CIS.

Discussion

The Skills to Enhance Positivity (STEP) program appears to be both feasible and acceptable for delivery in an acute care setting. The supplemental boosters of text messages to extend the reach of the intervention after discharge were particularly well received as evidenced by the relatively high engagement rate and the fact that over half the sample opted to continue to receive messages for an additional three months. Furthermore, preliminary data show those who received STEP reported fewer suicide events by nearly 50% compared to participants in the ETAU condition.

Feasibility and Acceptability

This is the first time to our knowledge that a positive affect-based intervention has been studied in this type of acute care setting for adolescents who are particularly vulnerable and at-risk for recurrent suicidal behavior. We found the individual sessions of STEP to be feasible to administer to adolescents during an inpatient hospital stay, with lower feasibility for the family session. We also found the post-discharge text messaging delivery to be feasible and desirable with over 50% opting for an extension of the messages beyond the one month. However, post-discharge phone sessions were found to be less feasible and acceptable, consistent with what has been reported in other studies (Ranney et al., 2013). Inpatient populations are at risk of treatment disengagement from outpatient services, either through a lapse in the continuity of care, referrals to other intensive forms of treatment, or treatment noncompliance (Knesper, 2011). A text or app-based program has several distinct benefits. First, as in STEP, an exercise practice reminder can be sent regardless of engagement with the program. Second, mood monitoring prompts can serve as a powerful intervention in and of itself. Finally, providers can receive important information about daily risk levels. Thus, the feasibility of delivering a post-discharge adjunctive intervention that can be reinforced through text messaging, with accessibility to participants of all backgrounds and socioeconomic status, is encouraging.

Nonetheless, our experience demonstrated that it is difficult to complete the four in-person sessions within one hospital admission, with a typical duration of one week. Research requirements, however, such as obtaining informed consent and administering baseline assessments that would not be part of standard clinical care, significantly add to this burden. It is possible that modifying STEP for a group format and integrating STEP into an inpatient treatment program would greatly enhance feasibility; however, meta-analyses have shown that positive psychology intervention effects are stronger when delivered individually as opposed to a group or self-help format (Bolier et al., 2013; Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009). Regardless, it will be important for future iterations of this intervention to preserve the most well-rated aspects of the program (e.g., exercises, automated text messaging), and eliminate the less feasible and less acceptable aspects (e.g., family session, telephone calls). Given the high satisfaction ratings and that 54% of participants opted for the optional 3-month tapered extension of text messages, retention of the text-messaging component in STEP, which is cost-effective and utilizes minimal resources, is crucial.

Positive Affect Outcomes

The exercises taught in STEP aim to increase attention to positive emotions and experiences that may otherwise be discounted, an aim that is consistent with the Broaden and Build theory. There is preliminary data to suggest that STEP may have engaged this target, as assessed by implicit cognitive tasks, though the results are based on a very small sample size. Results from the dot probe task found that STEP participants experienced a greater increase in attentional bias to positive words at follow-up, compared to ETAU participants. However, there was no effect for faces, which may require a different type of processing, and no effect for negative valence stimuli, though the latter is unsurprising as decreasing attentional bias to negative stimuli was not the target of intervention. Thus, results should be viewed cautiously and require replication with larger samples.

Self-report of positive emotions was remarkably stable over time in both groups, while self-report of negative emotions seemed to decrease in both groups. It is possible that this is a function of the clinical severity of this sample, such that the negative emotions experienced during hospitalization are so strong that most patients, regardless of intervention, are likely to experience a decrease of such emotions naturalistically. The high proportion of STEP participants who reported more days in which their positive emotions outweighed their negative emotions was encouraging, but should be interpreted cautiously particularly as the ETAU did not receive an mood monitoring texts.

Clinical Outcomes

While the sample size and total number of events was low, it was encouraging that those in the STEP condition reported 50% fewer suicide events (attempts and/or emergency intervention) compared to ETAU. The rate of suicide events in ETAU group (38%) is near identical to what we have found in naturalistic studies of inpatient suicidal adolescents (Yen et al., 2013); thus the lower rate of 19% suicide events in STEP over six months is promising. While there were no discernable differences between groups on suicide attempts, the rate in both groups were slightly lower (12% in STEP; 15% in ETAU) compared to historical controls (18%) using the same recruitment procedures and site as the present study (Yen et al., 2013). Furthermore, an earlier trial of STEP found a very low rate of suicide attempts in this high-risk population (Yen et al., 2017). Collectively, these trials suggest that STEP may have potential in reducing suicidal behaviors in recently discharged suicidal adolescents, though these findings need to be replicated in larger trials.

In general, we found that clinical self-report measures indicated improvement for both STEP and ETAU. This may represent a gradual return to baseline, or regression to the mean, that follows an acute crisis. Nonetheless, there is preliminary support to indicate that STEP resulted in improvements in depressed mood and functional impairment, per parent report. However, it is important to note that these group differences in improvements were not observed consistently throughout follow-up. It is possible that more services, such as continuing daily text messages for a longer duration for all participants, would yield gains that are more robust.

Limitations

This was a pilot study to examine the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of the STEP intervention. Thus, it was not adequately powered to observe between group differences, and effect sizes are known to be unstable in small sample sizes. Nor did we have enough power to examine mediators (e.g., increased social support or resources, improved problem-solving) that might explain the relationship between positive affect and reduced suicidal behaviors. However, the preliminary data from this trial supports the need for a larger intervention study, incorporating many of the lessons learned from conducting the present trial to make additional improvements in feasibility and acceptability.

Due to the limited available time to conduct the interventions, as well as the limited attention span of youth during acute psychiatric crises, most of our baseline clinical characteristics were obtained via chart review. A more robust assessment of psychiatric disorders and personality characteristics could reveal meaningful data on who might benefit from this type of program. In addition, as the mood monitoring questions of the daily text messaging intervention was conceptualized as an part of the intervention, we did not administer those items to the ETAU participants, thus limiting our ability to know whether the emotion responses from the daily text messaging (i.e., days in which positive emotions outweighed negative) differed across groups.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that a brief adjunctive in-person, text-message, and phone call intervention to teach exercises to increase attention to positive emotions and experiences could be successfully administered to suicidal adolescents on an inpatient psychiatric unit, and has the potential to increase positive affect as well as decrease suicidal behavior. The daily text messages prompting mood monitoring and exercise practice were especially well received and illustrate the promise of these types of interventions to extend the reach of treatment beyond hospitalization, which is particularly important for individuals who struggle with access to care. A larger clinical trial will be necessary to determine the effectiveness of this program.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health under Grant R34 MH101272 to Dr. Yen. We would like to thank all the study participants and their families for participating in this research, the doctors and staff from our recruitment site for their support of our work, and research assistants (Adam Chuong, Hye In (Sarah) Lee) that helped make this study possible.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Attkisson CC, & Zwick R (1982). The client satisfaction questionnaire. Psychometric properties and correlations with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Eval Program Plann, 5(3), 233–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, & Brown GK (1996). Beck depression inventory-II. San Antonio, 78(2), 490–498. [Google Scholar]

- Bird HR, Andrews H, Schwab-Stone M, Goodman S, Dulcan M, Richters J, . . . Hoven C (1996). Global measures of impairment for epidemiologic and clinical use with children and adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. [Google Scholar]

- Bird HR, Shaffer D, Fisher P, & Gould MS (1993). The Columbia Impairment Scale (CIS): Pilot findings on a measure of global impairment for children and adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. [Google Scholar]

- Bolier L, Haverman M, Westerhof GJ, Riper H, Smit F, & Bohlmeijer E (2013). Positive psychology interventions: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC public health, 13(1), 119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celano C, Beale E, Mastromauro C, Stewart J, Millstein R, Auerbach R, . . . Huffman J (2017). Psychological interventions to reduce suicidality in high-risk patients with major depression: a randomized controlled trial. Psychological medicine, 47(5), 810–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin SC, Warner M, & Hedegaard H (2016). Increase in suicide in the United States, 1999–2014. NCHS data brief, 241, 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doost HTN, Moradi AR, Taghavi MR, Yule W, & Dalgleish T (1999). The development of a corpus of emotional words produced by children and adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 27(3), 433–451. [Google Scholar]

- Dozois DJ, Dobson KS, & Ahnberg JL (1998). A psychometric evaluation of the Beck Depression Inventory–II. Psychological assessment, 10(2), 83. [Google Scholar]

- Ducasse D, Dassa D, Courtet P, Brand‐Arpon V, Walter A, Guillaume S, . . . Olié E (2019). Gratitude diary for the management of suicidal inpatients: A randomized controlled trial. Depression and anxiety. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons RA, & McCullough ME (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: an experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. J Pers Soc Psychol, 84(2), 377–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava GA, Rafanelli C, Cazzaro M, Conti S, & Grandi S (1998). Well-being therapy. A novel psychotherapeutic approach for residual symptoms of affective disorders. Psychol Med, 28(2), 475–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava GA, Ruini C, Rafanelli C, Finos L, Salmaso L, Mangelli L, & Sirigatti S (2005). Well-being therapy of generalized anxiety disorder. Psychother Psychosom, 74(1), 26–30. doi: 10.1159/000082023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am Psychol, 56(3), 218–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, & Branigan C (2005). Positive emotions broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires. Cogn Emot, 19(3), 313–332. doi: 10.1080/02699930441000238 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Cohn MA, Coffey KA, Pek J, & Finkel SM (2008). Open hearts build lives: positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. J Pers Soc Psychol, 95(5), 1045–1062. doi:2008–14857-004 [pii] 10.1037/a0013262 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, & Joiner T (2002). Positive emotions trigger upward spirals toward emotional well-being. Psychol Sci, 13(2), 172–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, & Losada MF (2005). Positive affect and the complex dynamics of human flourishing. Am Psychol, 60(7), 678–686. doi:2005–11834-001 [pii] 10.1037/0003-066X.60.7.678 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Tugade MM, Waugh CE, & Larkin GR (2003). What good are positive emotions in crises? A prospective study of resilience and emotions following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11th, 2001. J Pers Soc Psychol, 84(2), 365–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch JK, Duberstein PR, Chapman B, & Lyness JM (2007). Positive affect and suicide ideation in older adult primary care patients. Psychology and Aging, 22(2), 380–385. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.2.380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joormann J, & Gotlib IH (2007). Selective attention to emotional faces following recovery from depression. Journal of abnormal psychology, 116(1), 80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, McManus T, Harris W, Shanklin S, Flint K, Hawkins J, & Zaza S (2016). Youth risk behavior surveillance-United States, 2015. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 65 Suppl 6, 1–174. In. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, . . . Ryan N (1997). Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 36(7), 980–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knesper DJ (2011). Continuity of care for suicide prevention and research: suicide attempts and suicide deaths subsequent to discharge from an emergency department or an inpatient psychiatry unit: Suicide Prevention Resource Center.

- Lenhart A, Duggan M, Perrin A, Stepler R, Rainie H, & Parker K (2015). Teens, social media & technology overview 2015: Pew Research Center [Internet & American Life Project]. [Google Scholar]

- Leon AC, Davis LL, & Kraemer HC (2011). The role and interpretation of pilot studies in clinical research. Journal of psychiatric research, 45(5), 626–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Zhang W, Li X, Li N, & Ye B (2012). Gratitude and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among Chinese adolescents: Direct, mediated, and moderated effects. Journal of adolescence, 35(1), 55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod C, Mathews A, & Tata P (1986). Attentional bias in emotional disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 95(1), 15–20. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.95.1.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor E, Gaynes BN, Burda BU, Soh C, & Whitlock EP (2013). Screening for and treatment of suicide risk relevant to primary care: a systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Annals of internal medicine, 158(10), 741–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner K, Oquendo MA, Gould M, Stanley B, & Davies M (2007). Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment (C-CASA): classification of suicidal events in the FDA’s pediatric suicidal risk analysis of antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry, 164(7), 1035–1043. doi:164/7/1035 [pii] 10.1176/appi.ajp.164.7.1035 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranney ML, Choo EK, Spirito A, & Mello MJ (2013). Adolescents’ preference for technology-based emergency department behavioral interventions: does it depend on risky behaviors? Pediatric emergency care, 29(4), 475–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranney ML, Freeman JR, Connell G, Spirito A, Boyer E, Walton M, . . . Cunningham RM (2016). A depression prevention intervention for adolescents in the emergency department. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(4), 401–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM, & Onken LS (2001). A stage model of behavioral therapies research: Getting started and moving on from stage I. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 8(2), 133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman ME, Rashid T, & Parks AC (2006). Positive psychotherapy. Am Psychol, 61(8), 774–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sin NL, & Lyubomirsky S (2009). Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: a practice-friendly meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol, 65(5), 467–487. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20593 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarrier N, Taylor K, & Gooding P (2008). Cognitive-behavioral interventions to reduce suicide behavior: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav Modif, 32(1), 77–108. doi:32/1/77 [pii] 10.1177/0145445507304728 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tottenham N, Tanaka JW, Leon AC, McCarry T, Nurse M, Hare TA, . . . Nelson C (2009). The NimStim set of facial expressions: judgments from untrained research participants. Psychiatry Res, 168(3), 242–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen, Ranney ML, Tezanos KM, Chuong A, Kahler CW, Solomon JB, & Spirito A (2017). Skills to Enhance Positivity in Suicidal Adolescents: Results From an Open Development Trial. Behav Modif, 145445517748559. doi: 10.1177/0145445517748559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen, Weinstock L, Andover M, Sheets E, Selby E, & Spirito A (2013). Prospective predictors of adolescent suicidality: 6-month post-hospitalization follow-up. Psychological medicine, 43(05), 983–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen S, Spirito A, Weinstock LM, Tezanos K, Kolobaric A, & Miller I (In press). Coping Long Term with Active Suicide in Adolescents: Results from a Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Clinical Child Psychiatry and Psychology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]