Abstract

The management of carbapenem-resistant infections is often based on polymyxins, tigecycline, aminoglycosides and their combinations. However, in a recent systematic review, we found that Gram-negative bacteria (GNB) co-resistant to carbapanems, aminoglycosides, polymyxins and tigecycline (CAPT-resistant) are increasingly being reported worldwide. Clinical data to guide the treatment of CAPT-resistant GNB are scarce and based exclusively on few case reports and small case series, but seem to indicate that appropriate (in vitro active) antimicrobial regimens, including newer antibiotics and synergistic combinations, may be associated with lower mortality. In this review, we consolidate the available literature to inform clinicians dealing with CAPT-resistant GNB about treatment options by considering the mechanisms of resistance to carbapenems. In combination with rapid diagnostic methods that allow fast detection of carbapenemase production, the approach proposed in this review may guide a timely and targeted treatment of patients with infections by CAPT-resistant GNB. Specifically, we focus on the three most problematic species, namely Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii. Several treatment options are currently available for CAPT-resistant K. pneumonia. Newer β-lactam-β-lactamase combinations, including the combination of ceftazidime/avibactam with aztreonam against metallo-β-lactamase-producing isolates, appear to be more effective compared to combinations of older agents. Options for P. aeruginosa (especially metallo-β-lactamase-producing strains) and A. baumannii remain limited. Synergistic combination of older agents (e.g., polymyxin- or fosfomycin-based synergistic combinations) may represent a last resort option, but their use against CAPT-resistant GNB requires further study.

Keywords: Pandrug resistant, Treatment, Carbapanemase, Acinetobacter, Klebsiella, Pseudomonas

Introduction

For the management of carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria (GNB), clinicians often resort to combination therapy based on polymyxins (including colistin or polymyxin B), aminoglycosides and tigecycline [1, 2]. However, in a recent systematic review of the literature, we found that GNB with simultaneous resistance to carbapenems, aminoglycosides, polymyxins and tigecycline (CAPT-resistant), are increasingly being reported worldwide [3]. The CAPT-resistance phenotype is predominantly encountered in Acinetobacter baumannii, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. It typically affects severely ill patients and patients in intensive care units, but the potential for hospital-wide dissemination or between health-care facilities has been well documented [3].

All-cause mortality of patients with infections by CAPT-resistant GNB is high (ranging from 20 to 71%) [3]. The limited available clinical evidence, based on case reports and small case series, seems to indicate that appropriate treatment (based on in vitro susceptibility) with newer antibiotics or synergistic combinations may reduce mortality [3]. However, guidance about treatment options for CAPT-resistant bacteria is lacking.

This review aims to consolidate the available literature to inform clinicians dealing with CAPT-resistant GNB about the available treatment options by considering the mechanisms of carbapenem resistance of the three most problematic GNB species, namely K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa [3–5].

Rationale for treatment selection based on the mechanisms of carbapenem resistance for CAPT-resistant GNB

The mechanisms of resistance to carbapenems (predominantly carbapenemase production, as discussed later) are independent of the mechanisms of resistance to last resort antibiotics such as polymyxins (resistance predominantly mediated by plasmid- or chromosomally mediated modification of the lipopolysaccharide [6–9]), aminoglycosides (predominantly mediated by aminoglycoside modifying enzymes or 16S ribosomal RNA methyltransferases [10]), and tigecycline (predominantly mediated by overexpression of efflux pumps [8, 11, 12]). Therefore, newer β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor antibiotics and combinations that can overcome resistance mediated by carbapenemase production are still useful for CAPT-resistant GNB.

The usefulness of an approach based on the mechanism of resistance becomes clearer when laboratory methods to rapidly determine the mechanism of resistance are available to the clinician [13–16]. Delays in determining antimicrobial susceptibility with traditional growth-based laboratory methods, such as broth microdilution, disk diffusion, gradient tests and agar dilution, may result in inappropriate empirical therapy, which may be associated with prolonged hospital stay and increased mortality [3, 17–19]. Rapid diagnostic methods, such as nucleic acid-based tests that detect carbapenemase genes, phenotypic assays that detect hydrolysis of carbapenems including MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, and immunochromatographic assays, allow faster detection of carbapenemase production and many methods can even determine the most prevalent types of carbapenemases (e.g., KPC, VIM, NDM, OXA-48-like) [15, 16, 20–23]. Many of these methods can be implemented directly on spiked blood cultures [23, 24], allowing even earlier identification of the mechanisms of resistance and targeted treatment in a timely manner.

However, considering the limitations of some rapid diagnostic methods regarding the detection of rare or novel β-lactamase variants [23, 25–27], susceptibility to the selected treatment regimen should always be confirmed with traditional growth-based methods. Pending such confirmation (and taking into consideration local epidemiological data), it may be reasonable to use combination empirical therapy for severely ill patients at risk for carbapenem-resistant infections [17].

Brief overview of the mechanisms of resistance to carbapenems

Understanding the molecular mechanisms of resistance to carbapenems is the most useful first step to guide the treatment of CAPT-resistant GNB. Several mechanisms can result in resistance to carbapenems [28]: (1) production of carbapenemases, (2) mutation of porins resulting in reduced outer membrane permeability, (3) overexpression of efflux pumps, (4) target modification (rare). A combination of these mechanisms is also possible. The mechanisms used by each of the three species reviewed here vary significantly in prevalence, not only between different species but also between different countries or regions [10, 29–33].

Carbapenem resistance in K. pneumoniae

Production of carbapenemases, which are typically acquired by horizontal gene transfer, is the predominant mechanism responsible for carbapenem resistance in K. pneumoniae [10, 34]. The type of carbapenemase is highly variable in different geographical regions [10, 29, 30]. Metallo-beta lactamases (MBL) appear to be substantially more prevalent in Asia (especially the Indian subcontinent) and in some European countries [29, 30], with an increasing prevalence following the introduction of ceftazidime/avibactam [35]. In contrast, OXA-48-like carbapenemases are most prevalent in countries of the Mediterranean Basin, especially Turkey [10, 29]. In the USA, Canada, Latin America, China and some European countries (mainly Italy and Greece), KPCs are the most prevalent carbapenemases [10, 29, 36]. The frequency of carbapenemase-negative carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae is also highly variable in different countries and continents [10, 30, 34]. Porin mutations or efflux pump overexpression (often combined with the production of beta-lactamases) appear to be responsible for the resistance in carbapenemase-negative K. pneumoniae [37–40].

Carbapenem resistance in P. aeruginosa

In contrast to K. pneumoniae and other Enterobacterales that acquire carbapenem resistance predominantly by horizontal gene transfer of carbapenemases, resistance in P. aeruginosa is predominantly mediated by chromosomal mutations resulting in loss or reduction of porin OprD, overexpression of the cephalosporinase AmpC and overexpression of efflux pumps [41–43]. For example, only about 20% of carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa in Europe [41] and 4.3% in Canada [44] produced carbapenemases, predominantly metallo-β-lactamases (specifically VIM and IMP). However, the prevalence of MBL among carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa is rising [41] and in some settings the majority (70–88%) of carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa isolates are MBL producers [32, 33]. Furthermore, GES-type carbapenemases are increasingly being reported in P. aeruginosa [44–47].

Carbapenem resistance in A. baumannii

Similar to P. aeruginosa, reduced membrane permeability and upregulation of efflux pumps are important mechanisms of resistance in A. baumannii [48, 49]. However, production of Class D carbapenemases (OXA-23 being by far the most widespread in most countries), and less commonly Class A (including KPC and GES) and Class B (MBL) carbapenemases, is the major mechanism of carbapenem resistance in A. baumannii [49–51]. In contrast to OXA-48 carbapenemases of Enterobacterales which are inhibited by avibactam, A. baumannii’s oxacillinases are resistant to all beta-lactamase inhibitors currently in clinical use, including vaborbactam, relebactam, and avibactam [52–55]. Notably, carbapenem resistance in A. baumannii is rising and in many regions, especially in Europe and the Middle East, the vast majority of A. baumannii are resistant to carbapenems [56]. For example, about 80% of A. baumannii associated with hospital-acquired infections in Europe are carbapenem-non-susceptible [57, 58].

Options for CAPT-resistant K. pneumoniae

Several treatment options are available for non-MBL carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae. Ceftazidime/avibactam [59, 60] is active against both Class A (KPC) and Class D (especially OXA-48-like) carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae, whereas meropenem/vaborbactam [61] and imipenem/relebactam [62] are only active against Class A carbapenemases. A limitation of ceftazidime/avibactam is the potential for emergence of resistance during treatment due to KPC mutations [63–67]. These mutations may reverse the susceptibility to carbapenems [65, 67, 68], but switching to carbapenem monotherapy in such cases may re-select for carbapenem resistance [69]. Meropenem/vaborbactam [70] and imipenem/relebactam [62] remain active against some KPC variants conferring resistance to ceftazidime/avibactam, and against the recently described VEB-25 extended spectrum β-lactamase that has been associated with ceftazidime/avibactam resistance [26]. Furthermore, emergence of resistance may be less likely compared to ceftazidime/avibactam [66, 71]. Finally, several case reports and small series have reported successful treatment of CAPT-resistant KPC-producing K. pneumoniae with a double carbapenem combination [72–75]. The rationale of this combination is that ertapenem due to its higher affinity with the carbapenemase enzyme acts as a suicide inhibitor, allowing higher levels of the second carbapenem (typically meropenem or doripenem) [72–75].

On the other hand, options for MBL-producing K. pneumoniae are limited. The novel β-lactam–β-lactamase inhibitor combinations, including ceftazidime/avibactam [59], ceftolozane/tazobactam [76], meropenem/vaborbactam [77] and imipenem/relebactam [55], are inactive against MBL-producing GNB [78]. In contrast, the combination of aztreonam with avibactam may restore activity against MBL-producing isolates [60, 79], because aztreonam is not hydrolyzed by MBLs and avibactam effectively inhibits other beta-lactamases (ESBL, KPC and OXA-48) that can hydrolyze aztreonam. The combination aztreonam–avibactam is not currently available, but the combination of ceftazidime–avibactam plus aztreonam has been used successfully against infections by MBL-producing bacteria [80–83].

Plazomicin is more active compared to alternative aminoglycosides against carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales regardless of the mechanism of carbapenem resistance [10], and is active against polymyxin-resistant Enterobacterales, regardless of the mechanism of polymyxin resistance [84]. However, production of 16S-rRNA-methyltransferases (which confer resistance to plazomicin) is encountered in up to 60% of MBL-producing K. pneumoniae [10].

Several options are also available for carbapenemase-negative carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae. Plazomicin is active against the majority (95%) of carbapenemase-negative carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales [10]. Isolates with outer membrane permeability changes (typically OmpK35 and OmpK36 porin mutations) often remain susceptible to ceftazidime/avibactam [85–87], meropenem/vaborbactam [88] and imipenem/relebactam [62, 89], albeit with higher MICs. A theoretical concern in such cases is that with an MIC closer to the susceptibility breakpoint, emergence of resistance may be more likely by stepwise accumulation of multiple chromosomally mediated resistance mechanisms, including mutations resulting in reduced membrane permeability, overexpression of efflux pumps, overexpression of β-lactamases or mutations attenuating the effect of β-lactamase inhibitors [87, 90].

Other potential options for CAPT-resistant K. pneumoniae include eravacycline, fosfomycin and cefiderocol. Eravacycline is more potent compared to tigecycline and may be active against some tigecycline-resistant strains (especially considering the current EUCAST susceptibility breakpoint for tigecycline) [91, 92]. Successful use of fosfomycin against extensively drug-resistant K. pneumoniae has been reported in small case series, often in combination with other antimicrobials [93, 94]. Despite concerns about development of resistance during treatment, this does not appear to be a problem in clinical practice possibly because fosfomycin resistance may carry a biological fitness cost [95, 96].

Finally, synergistic combinations, such as colistin-based combinations [97, 98] or combination of fosfomycin with carbapenems [94, 99], may prove useful last-resort options, but pharmacodynamic/pharmacokinetic (PK/PD) and clinical studies are lacking, especially against isolates co-resistant to all components of the combinations [3]. Synergistic combinations based on ceftazidime/avibactam (combined with fosfomycin + aztreonam or meropenem) have also been reported for the treatment of ceftazidime/avibactam-resistant strains [26]. Combinations exploiting multiple heteroresistance is another interesting option and may be effective against pan-resistant K. pneumoniae based on in vitro and in vivo animal data [100].

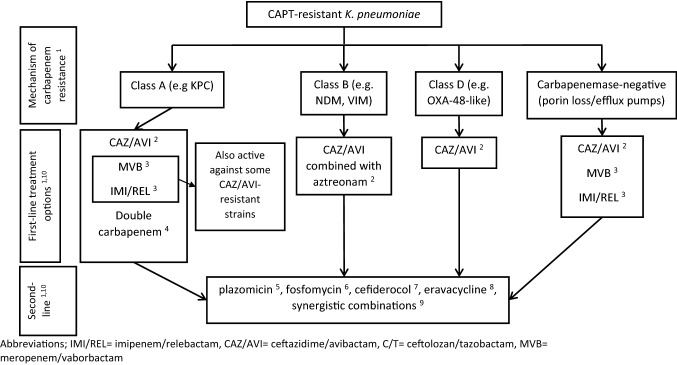

Based on the above evidence synthesis, treatment options for CAPT-resistant K. pneumoniae are summarized in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 .

Treatment options for CAPT-resistant K. pneumoniae depending on the mechanism of resistance to carbapenems. 1 Several rapid methods are available or under development that can detect both the production and the type of carbapenemases [20–23]. Because rare or novel β-lactamase variants may not be detectable by some methods [23, 25–27], susceptibility should always be confirmed with traditional growth-based methods and combination therapy may be reasonable pending such confirmation, especially in severe infections [17]. 2 CAZ/AVI is active against both Class A and some Class D carbapenemases [59] and is less affected by outer membrane permeability changes (porin mutations or efflux pumps) [85, 86]. CAZ/AVI can be combined with aztreonam to overcome resistance to MBL [80–82]. Notable, however, is the potential for emergence of resistance during treatment due to KPC mutations [63–66] and due to the recently described VEB-25 extended spectrum β-lactamase [26]. 3 MVB and IMI/REL are active against Class A (KPC) carbapenemase producers, but not against Class B or Class D carbapenemase producers [61, 62]. Both remain active against some KPC variants that confer resistance to CAZ/AVI [70] and against the recently described VEB-25 extended spectrum β-lactamase that has been associated with CAZ/AVI resistance [26]. MVB and IMI/REL may also be active against isolates with porin mutations, but major OmpK35 or OmpK36 disruptions may be associated with resistance [62, 88]. Emergence of resistance may be less likely compared to CAZ/AVI monotherapy [66, 71]. 4 Double carbapenem combinations may be useful if CAZ/AVI, MVB and IMI/REL are not available (or not an option due to higher cost) and have been used effectively against KPC-producing CAPT-resistant K. pneumoniae [72–75]. 5 Plazomicin is active against 93% of KPC-producing, 42% of MBL-producing (co-production of 16S-rRNA-methyltransferases), 87% of OXA-producing, and 95% of carbapenemase-negative carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales [10]. 6 Fosfomycin has been shown to be effective against XDR/PDR K. pneumoniae [93, 94], but its activity is highly variable [96]. 7 Cefiderocol is stable against hydrolysis by all carbapenemases (including MBL) and its mechanism of bacterial cell entry is independent of porin channels and efflux pumps. Therefore, cefiderocol appears to be a useful option when no other antibiotic is active [114, 115]. 8 Eravacycline is more potent compared to tigecycline and may be active against some tigecycline-resistant strains [91, 92]. 9 Options include combinations based on colistin [97, 98], fosfomycin [94, 99] and ceftazidime/avibactam [26], and combinations exploiting multiple heteroresistance [100]. 10 Beta-lactam-based regimens (double carbapenem, newer β-lactams–β-lactamases and the combination of CAZ/AVI with aztreonam) have been better studied compared to other options, and have been associated with better outcomes compared to older agents and their combinations [66, 166–169, 171, 172]

Options for CAPT-resistant P. aeruginosa

In contrast to CAPT-resistant K. pneumoniae, meropenem–vaborbactam and plazomicin are not useful for CAPT-resistant P. aeruginosa. The activity of meropenem–vaborbactam is similar to that of meropenem alone [61] and plazomicin is not better than older aminoglycosides against P. aeruginosa [10].

On the other hand, ceftazidime/avibactam and ceftolozane/tazobactam may retain activity against selected CAPT-resistant P. aeruginosa strains. Both are less prone to outer membrane permeability changes (porin loss/efflux pumps) and neither is affected by AmpC (ceftolozane is stable against AmpC and avibactam restores the activity of ceftazidime by inhibition of AmpC) [101, 102]. Therefore, both ceftazidime/avibactam and ceftolozane/tazobactam remain highly active (81–92% [101, 103–106]) against non-MBL carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa, but susceptibility may be much lower (41–48% [45, 103]) in isolates co-resistant to multiple anti-pseudomonal beta-lactams (ceftazidime, piperacillin/tazobactam and cefepime). Generally, ceftolozane/tazobactam appears to be more potent than ceftazidime/avibactam in non-carbapenemase-producing P. aeruginosa [101, 102], and has been used successfully against ventilator-associated pneumonia by CAPT-resistant P. aeruginosa [107].

Resistance to ceftazidime/avibactam and ceftolozane/tazobactam is usually the result of structural modifications of AmpC (in addition to overexpression) or horizontally acquired carbapenemases [108, 109]. Imipenem-relebactam, another option against non-MBL producing P. aeruginosa [110], is not affected by AmpC mutations that confer resistance to ceftazidime/avibactam and ceftolozane/tazobactam [110]. However, GES-producing P. aeruginosa strains are resistant to both imipenem/relebactam [46, 47] and ceftolozane/tazobactam [45, 111], but may be susceptible against ceftazidime/avibactam [45, 111].

Neither imipenem/relebactam nor ceftolozane/tazobactam or ceftazidime/avibactam is active against MBL-producing P. aeruginosa [55, 59, 76]. Furthermore, in contrast to MBL-producing K. pneumoniae, aztreonam/avibactam cannot overcome resistance against most MBL-producing P. aeruginosa due to mechanisms of resistance to aztreonam independent of beta-lactamases [112]. Nevertheless, the combination of ceftazidime/avibactam with aztreonam may be useful against selected strains, with intermediate/borderline MICs to aztreonam or ceftazidime/avibactam [81, 113]. Cefiderocol on the other hand is stable to hydrolysis by all carbapenemases (including MBL and OXA) and is not affected by porin/efflux pumps mutations [114–116]. It is therefore a useful option when everything else is ineffective.

Fosfomycin has also been used successfully against CAPT-resistant P. aeruginosa [93]. However, fosfomycin monotherapy should be avoided in P. aeruginosa infections given the risk of emergence of resistance during treatment [117–119]. Finally, various synergistic combinations (e.g., based on colistin [120, 121], fosfomycin [122, 123] or aminoglycosides [45]) may represent a last resort treatment option. The combination of ceftolozane–tazobactam with amikacin [45] or fosfomycin [122] may also be effective based on in vitro evidence.

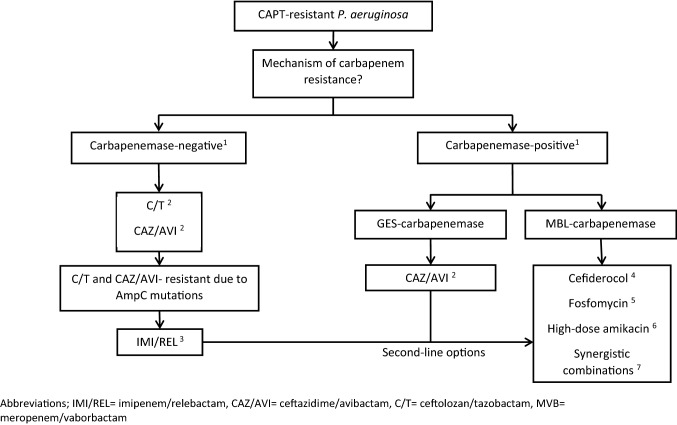

Based on this evidence synthesis, treatment options for CAPT-resistant P. aeruginosa are summarized in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2 .

Treatment options for CAPT-resistant P. aeruginosa depending on the mechanism of resistance to carbapenems. 1 The prevalence of carbapenemases varies substantially in different regions, but may be very high in some settings [31–33, 41]. MBL are the predominant carbapenemases in P. aeruginosa, but GES carbapenemases are increasingly being reported [45–47] Neither IMI/REL nor CAZ/AVI or C/T is active against MBL-producing P. aeruginosa [55, 59, 76], while GES carbapenemases may inactivate IMI/REL [46, 47] and C/T [45, 111] but not CAZ/AVI [45, 111]. Because rare or novel β-lactamase variants may not be detectable by some rapid methods [23, 25–27], susceptibility should always be confirmed with traditional growth-based methods and combination therapy may be reasonable pending such confirmation, especially in severe infections [17]. 2 Both CAZ/AVI and C/T are unaffected by the most common mechanism of resistance in P. aeruginosa (OprD porin mutations, overexpression of efflux pumps, overexpression of AmpC) [101, 102]. Resistance to CAZ/AVI and C/T is usually the result of structural modifications of AmpC (+ overexpression of AmpC) or horizontally acquired carbapenemases [108, 109]. GES-type carbapenemases may confer resistance to C/T but not to CAZ/AVI [45]. 3 IMI/REL is unaffected by the most relevant mutation-driven β-lactam resistance mechanisms of P. aeruginosa [110]. Moreover, IMI/REL is not affected by AmpC mutations that confer resistance to ceftazidime/avibactam and ceftolozane/tazobactam [110]. IMI/REL is ineffective against MBL- and GES-producing P. aeruginosa strains [46, 47]. 4 Cefiderocol is stable against hydrolysis by all carbapenemases (including MBL) and its mechanism of bacterial cell entry is independent from porin channels and efflux pumps. Therefore, cefiderocol appears to be a useful option when no other antibiotic is active [114, 115]. 5 Alternative antibiotics (if available) may be preferable taking into account the concerns for emergence of resistance during treatment with fosfomycin [96, 117]. When fosfomycin is used it should be combined with a second antibiotic. 6 High-dose aminoglycoside therapy (such as amikacin 50 mg/kg/day) may be a useful option for CACT-resistant P. aeruginosa with borderline MIC (e.g., amikacin MIC = 16 mg/dl) and can be combined with hemodialysis to reduce nephrotoxicity [184, 186, 187]. 7 Until cefiderocol becomes widely available, synergistic combinations (e.g., based on colistin [120, 121], fosfomycin [122, 123], aminoglycosides [45] and C/T [45, 122]) may sometimes represent the only treatment option, but PK/PD and clinical studies are needed. Other options are ineffective for CAPT-resistant P. aeruginosa: The activity of MVB against P. aeruginosa is similar to that of meropenem alone [61].: Plazomicin is no better than other aminoglycosides against P. aeruginosa [10].: Similar to other tetracyclines, P. aeruginosa is resistant to eravacycline [91].: Aztreonam/avibactam cannot overcome resistance against most MBL-producing P. aeruginosa [112], but may be useful against selected strains with borderline/intermediate MICs to aztreonam or ceftazidime/avibactam [81, 113]

Options for CAPT-resistant A. baumannii

Options for CAPT-resistant A. baumannii are limited. This is reasonable considering the multiple concurrent mechanisms of resistance in A. baumannii, including reduced membrane permeability, increased efflux and Class B and D carbapenemase production. None of the new β-lactam–β-lactamase inhibitor combinations (meropenem/vaborbactam, imipenem/relebactam, ceftazidime/avibactam, ceftolozane/tazobactam, aztreonam/avibactam) are active against carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii [61, 124–127]. Furthermore, plazomicin does not have better activity compared to alternative aminoglycosides [10], and A. baumannii appears to be intrinsically resistant to fosfomycin [96, 128].

Potential currently available options for CAPT-resistant A. baumannii include minocycline, eravacycline and cefiderocol. Eravacycline is more potent compared to tigecycline and may be an option against some tigecycline-resistant A. baumannii strains [92, 129–131]. Minocycline has also been proposed as an option and has been used against carbapenem-resistant isolates [132], but its role and activity against CAPT-resistant isolates is unclear, especially considering that its susceptibility breakpoints are unclear [133] and the lack of modern PK/PD studies and randomized controlled trials [134]. Finally, cefiderocol is active against most A. baumannii, but cefiderocol-resistant strains have already been reported [114, 135]. Ampicillin/sulbactam and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole have been used against carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii [131, 136–138], but their role and activity against CAPT-resistant isolates are less clear.

Until cefiderocol or other new antibiotics (such as combinations with Class D carbapenemase inhibitors [52]) become widely available, or in cases of cefiderocol resistance, synergistic combinations may represent the only option for CAPT-resistant A. baumannii. Polymyxin-based synergistic combinations (e.g., with rifampicin, carbapenems, ampicillin/sulbactam, fosfomycin, glycopeptides, tigecycline and minocycline) are the most studied, but have been tried predominantly against carbapenem-resistant polymyxin-susceptible A. baumannii, and clinical benefit has not yet been found in most studies [2, 139–144]. Differences between in vitro and in vivo conditions, such as insufficient drug concentrations, insufficient exposure time to synergistic concentrations, host immune-pathogen interactions and fitness cost associated with polymyxin resistance have been proposed as potential explanations [140, 141, 145]. Furthermore, most studies on polymyxin-based combinations have been conducted with colistin [146]. However, polymyxin B has important pharmacokinetic advantages and is less nephrotoxic [147–149], and according to a recent international consensus should be preferred over colistin except for lower urinary tract infections [146]. Therefore, clinical data are needed to assess the impact of polymyxin B-based combination regimens [146].

Despite the above limitations, polymyxin-based combinations may be useful for the management of CAPT-resistant A. baumannii based on in vitro and animal studies [120, 144, 150–152] and limited clinical data [153–158]. For example, the combination of colistin with rifampicin has been used successfully against colistin-resistant A. baumannii pneumonia [154] and colistin-resistant A. baumannii postsurgical meningitis [156, 157]. Notable is the synergy between colistin and agents that are not active against Gram-negative bacteria (such as linezolid and vancomycin), suggesting that colistin may exert a sub-inhibitory permeabilizing effect that allows increased entry of other drugs into the bacteria [150, 159].

High-dose ampicillin–sulbactam combined with meropenem and polymyxins is another promising combination [153, 160, 161], and has been used successfully against CAPT-resistant A. baumannii ventilator-associated pneumonia [153]. Furthermore, based on a recent in vitro study, the combination sulbactam/avibactam (which can be currently achieved by combining ampicillin/sulbactam with ceftazidime/avibactam) may be useful against non-MBL-producing A. baumannii [162]. The rationale of this combination is that avibactam can inhibit most of the beta-lactamases that can affect the activity of sulbactam [162].

Tigecycline-based combinations have also been proposed, but have predominantly been studied against tigecycline-susceptible strains, or in combination with an in vitro active agent (predominantly colistin) [163]. Although data regarding tigecycline-based combinations against CAPT-resistant GNB are limited, such combinations are often used in clinical practice given the lack of other options [158, 164]. Synergistic combinations with minocycline may also prove useful [144], but currently available data are very limited.

In summary, older agents (including minocycline, ampicillin/sulbactam and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole) may be an option against CAPT-resistant A. baumannii if in vitro active and have been used mainly in combination with other agents. Among newer (currently approved) agents, eravacycline and cefiderocol are other options. If none of the above options are active, or where newer agents are not yet available, polymyxin-, tigecycline- and sulbactam-based synergistic combinations may prove useful, but their role against CAPT-resistant strains remains understudied.

Selecting between the different options

Randomized controlled trials providing robust evidence to guide the selection of one agent over the other are lacking [3, 66, 165]. Approval of newer antimicrobials is usually based on non-inferiority trial designs, which have several limitations including insufficient power to assess the superiority of one antimicrobial over the other and even the possibility of bias favoring non-inferiority [165]. Furthermore, trials of new antimicrobials are often conducted in patients with carbapenem-susceptible infections and their results are extrapolated to patients with more resistant infections based on in vitro susceptibility data [14, 165]. Post-marketing adaptive randomized controlled trial designs have been proposed to assess newer antimicrobials for patients with multidrug-resistant GNB infections, who were not included in earlier phase studies [165]. Use of rapid diagnostic methods, combined with utilization of algorithms guided by mechanisms of resistance (such as those proposed here), may guide a more efficient targeting of newer antimicrobials in clinical trials [14, 165].

The available evidence, predominantly based on real rife observational data, suggests the superiority of beta-lactam-based therapy (i.e., double-carbapenem [166] or newer β-lactam–β-lactamase combination regimens such as ceftazidime/avibactam [66, 167–170], meropenem/vaborbactam [66, 171] or imipenem/relebactam [172]) over older antimicrobial options (including polymyxins, aminoglycosides, tigecycline and their combinations) against carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales. Furthermore, in a recent multicenter observational study, the combination of ceftazidime/avibactam with aztreonam was associated with significantly lower clinical failure, mortality and length of stay compared to other active agents (including combinations of polymyxins, tigecycline, aminoglycosides and fosfomycin) for bloodstream infection by MBL-producing Enterobacterales (predominantly K. pneumoniae) [83]. Moreover, ceftazidime/avibactam has been used successfully as salvage therapy against infections by carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae that have failed various combination regimens [173]. Ceftazidime/avibactam and meropenem/vaborbactam appear to have similar efficacy, although emergence of resistance during treatment is more common with ceftazidime/avibactam monotherapy [71]. Nevertheless, based on limited available data, ceftazidime/avibactam monotherapy and combination therapy are associated with similar outcomes [170, 174].

Clinical data for other options (including fosfomycin, eravacycline, minocycline, plazomicin, cefiderocol, synergistic combinations) against carbapenem-resistant bacteria are still limited. The results of the prematurely terminated CARE trial seem to favor plazomicin over colistin-based combinations, although the number of patients enrolled was very small [175]. Eravacycline appears to be a good option extrapolating from trials of carbepenem-susceptible infections [177], but data against carbapenem-resistant infections are limited [176]. Minocycline has shown favorable efficacy against carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii [132, 178], but the activity of minocycline against tigecycline-resistant strains is unclear considering the lack of modern PK/PD studies and unclear susceptibility breakpoints [133, 134]. Intravenous fosfomycin has been used successfully against extensively drug-resistant and CAPT-resistant GNB in small case series [93, 94]. Cefiderocol has been used successfully as a last resort option, but the limited available data against carbapenem-resistant bacteria are conflicting [179]. Finally, several in vitro studies have evaluated synergistic combinations, but clinical data against isolates co-resistant to all components of the combinations are limited to small series or case reports [3, 153, 154, 156–158].

Treatment regimen for the combination of ceftazidime/avibactam with aztreonam

With the currently recommended treatment regimen for ceftazidime/avibactam (2 + 0.5 g every 8 h by 2 h intravenous infusion, adjusted for renal function) a high probability (> 90%) of target attainment against MIC ≤ 8 mg/l can be achieved regardless of older age, obesity, augmented renal clearance, or severity of infection [180, 181]. Prolonged or continuous infusion of ceftazidime/avibactam does not seem to improve PD target attainment compared to the standard 2 h infusion [182]. However, the optimal regimen for the combination of ceftazidime/avibactam with aztreonam for MBL-producing Enterobacterales remains unclear [13, 83]. In the largest cohort, the regimen used was: ceftazidime/avibactam 2 + 0.5 g every 8 h (administered as a prolonged 8 h infusion in half of the patients and as a 2 h infusion in the rest) and aztreonam 2 g every 8 h (administered as a 2 h infusion) [83]. Based on a recent study using a hollow-fiber infection model comparing the effect of various regimens on bacterial killing and suppression of resistance, the following were proposed [183]: (1) simultaneous administration of ceftazidime/avibactam with aztreonam is preferred to staggered administration (ceftazidime/avibactam first, followed by aztreonam), (2) continuous infusion and standard 2 h infusion appear to be equally effective, (3) a total daily dose of 8 g aztreonam may be superior to 6 g. However, only two NDM-1-producing E. coli and K. pneumoniae strains were used in the study and validation of these results in more strains is necessary [183].

PK/PD considerations and dosing strategies for overcoming resistance

Reviewing the dosing regimens and PK/PD considerations for each of the antimicrobials discussed in this manuscript is beyond the scope of this review. However, it is worth highlighting the potential of attaining PD targets in selected cases when the MIC is above the susceptibility breakpoint with higher dose (for concentration-dependent antimicrobials) or prolonged/continuous infusion regimens (for time-dependent antimicrobials). For example, two patients with renal failure and sepsis by pandrug-resistant P. aeruginosa were successfully treated with high-dose amikacin monotherapy (25 and 50 mg/kg/day, respectively) despite an MIC of 16 mg/L [184]. Continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration was used to enhance extrarenal clearance of amikacin and achieve low trough concentrations to reduce the risk of otherwise unavoidable nephrotoxicity [185]. In both patients, the peak amikacin concentration was eight to ten times the MIC and renal function was preserved [184]. Combining high-dose aminoglycosides (to achieve PD targets) with hemodialysis (to increase clearance and decrease nephrotoxicity) is an interesting option [186, 187], especially when no alternatives are available, but requires further study.

Based on PK/PD modeling with Monte Carlo simulations, optimized prolonged infusion treatment regimens to overcome resistance have been proposed for a variety of time-dependent antimicrobials whose efficacy is best predicted by the time that the antibiotic’s concentration is above the MIC (% T > MIC, or % f T > MIC considering the free, unbound drug concentration). For example, two-step administration of meropenem (1.5 g administered intravenously over 5 min followed by a 6 h infusion of 0.5 g, repeated every 8 h) can achieve a > 90% probability of target attainment for carbapenem-resistant isolates with MIC up to 128 mg/L (considering a target 50% f T > MIC), or up to 32 mg/L (considering a higher target of 50% f T > 5 × MIC) [188]. Regarding ceftolozane/tazobactam, an extended (4–5 h) infusion may perform better compared to shorter or longer infusions, especially in patients with augmented renal clearance, and has been proposed to achieve target attainment (40% fT > MIC) for P. aeruginosa strains with MIC up to 32 mg/dl [189]. Furthermore, prolonged or continuous infusion of sulbactam may allow target attainment (60% T > MIC) against A. baumannii strains with sulbactam MIC up to 32 mg/L [190, 191]. Finally, administration of fosfomycin as prolonged infusion (6 h infusions of 8 g every 8 h) may allow target attainment (70% T > MIC in this study) for P. aeruginosa with MIC up to 128 mg/L, while continuous infusion of 16 g/day may allow target attainment for strains with MIC up to 96 mg/L [192]. However, fosfomycin-resistant subpopulations rapidly emerge, especially from strains with higher baseline MIC and fosfomycin heteroresistance [118, 119, 193, 194]. Therefore, the benefits of prolonged or continuous fosfomycin infusion may be more apparent when used in synergistic combination regimens [118, 192], especially when the second antibiotic can counterselect resistance amplification by exploiting multiple heteroresistance [100]. Clinical data for the use the above options are not available.

Direct delivery at the site of infection may also be an option to achieve sufficient antibiotic concentration and attain PD targets. For example, a case of meningitis by pandrug-resistant P. aeruginosa (with amikacin MIC 32 mg/L) was successfully treated with intraventricular amikacin [195]. PK/PD considerations for intrathecal administration of antibiotics are discussed in detail in a recent review [196]. Intravesical administration of antibiotics (e.g., colistin or aminoglycosides [197, 198]) may also be an option for lower urinary tract infections, but clinical data against CAPT-resistant GNB are lacking.

Conclusions

Understanding the molecular mechanisms of resistance and the local epidemiology of these mechanisms is crucial in guiding decision-making when selecting appropriate (in vitro active) antimicrobials for the management of CAPT-resistant GNB. This understanding becomes particularly useful in the presence of laboratory methods that can rapidly determine the molecular mechanisms of resistance. Several such methods are available, including lower-cost phenotypical assays, and are suitable for microbiology laboratories of any capacity. This review shows that several treatment options are available against CAPT-resistant K. pneumoniae and against non-MBL CAPT-resistant P. aeruginosa, but controlled trials to guide the selection of one agent over the other are still lacking. On the contrary, options for MBL-producing P. aeruginosa and CAPT-resistant A. baumannii are limited. Cefiderocol and other novel agents under development are promising future options. Until new agents become widely available in clinical practice, more research (including PK/PD and outcome studies) on the effectiveness of synergistic combinations or optimized prolonged infusion regimens might help.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Compliance with ethical standards

Competing interests

None.

References

- 1.Papst L, Beović B, Pulcini C, Durante-Mangoni E, Rodríguez-Baño J, Kaye KS, et al. Antibiotic treatment of infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacilli: an international ESCMID cross-sectional survey among infectious diseases specialists practicing in large hospitals. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24:1070–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piperaki ET, Tzouvelekis LS, Miriagou V, Daikos GL. Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: in pursuit of an effective treatment. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;25:951–957. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karakonstantis S, Kritsotakis EI, Gikas A. Pandrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria: a systematic review of current epidemiology, prognosis and treatment options. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;75:271–282. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boucher HW, Talbot GH, Bradley JS, Edwards JE, Gilbert D, Rice LB, et al. Bad bugs, no drugs: no ESKAPE! An update from the infectious diseases society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1–12. doi: 10.1086/595011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tacconelli E, Carrara E, Savoldi A, Harbarth S, Mendelson M, Monnet DL, et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:318–327. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30753-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aghapour Z, Gholizadeh P, Ganbarov K, Bialvaei AZ, Mahmood SS, Tanomand A, et al. Molecular mechanisms related to colistin resistance in Enterobacteriaceae. Infect Drug Resist. 2019;12:965–975. doi: 10.2147/idr.S199844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elyed AG, Zhong LL, Shen C, Yang Y, Doi Y, Tian GB. Colistin and its role in the era of antibiotic resistance: an extended review (2000–2019) Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):868–885. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1754133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karakonstantis S. A systematic review of implications, mechanisms, and stability of in vivo emergent resistance to colistin and tigecycline in Acinetobacter baumannii. J Chemother. 2020 doi: 10.1080/1120009X.2020.1794393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karakonstantis S, Saridakis I. Colistin heteroresistance in Acinetobacter spp; systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence and discussion of the mechanisms and potential therapeutic implications. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;56:106065. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castanheira M, Deshpande LM, Woosley LN, Serio AW, Krause KM, Flamm RK. Activity of plazomicin compared with other aminoglycosides against isolates from European and adjacent countries, including Enterobacteriaceae molecularly characterized for aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes and other resistance mechanisms. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73:3346–3354. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shankar C, Nabarro LEB, Anandan S, Veeraraghavan B. Minocycline and tigecycline: what is their role in the treatment of carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative organisms? Microb Drug Resist. 2017;23:437–446. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2016.0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pournaras S, Koumaki V, Spanakis N, Gennimata V, Tsakris A. Current perspectives on tigecycline resistance in Enterobacteriaceae: susceptibility testing issues and mechanisms of resistance. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2016;48:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yasmin M, Fouts DE, Jacobs MR, Haydar H, Marshall SH, White R, et al. Monitoring Ceftazidime–avibactam (CAZ-AVI) and Aztreonam (ATM) concentrations in the treatment of a bloodstream infection caused by a multidrug-resistant Enterobacter sp. Carrying both KPC-4 and NDM-1 carbapenemases. Clin Infect Dis. 2019 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bassetti M, Ariyasu M, Binkowitz B, Nagata TD, Echols RM, Matsunaga Y, et al. Designing a pathogen-focused study to address the high unmet medical need represented by carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative pathogens—the international, multicenter, randomized, open-label, phase 3 CREDIBLE-CR Study. Infect Drug Resist. 2019;12:3607–3623. doi: 10.2147/idr.S225553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Banerjee R, Humphries R. Clinical and laboratory considerations for the rapid detection of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Virulence. 2017;8:427–439. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2016.1185577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dortet L, Tandé D, de Briel D, Bernabeu S, Lasserre C, Gregorowicz G, et al. MALDI-TOF for the rapid detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: comparison of the commercialized MBT STAR®-Carba IVD Kit with two in-house MALDI-TOF techniques and the RAPIDEC® CARBA NP. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73:2352–2359. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gutierrez-Gutierrez B, Salamanca E, de Cueto M, Hsueh PR, Viale P, Pano-Pardo JR, et al. Effect of appropriate combination therapy on mortality of patients with bloodstream infections due to carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (INCREMENT): a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:726–734. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(17)30228-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zilberberg MD, Nathanson BH, Sulham K, Fan W, Shorr AF. Carbapenem resistance, inappropriate empiric treatment and outcomes among patients hospitalized with Enterobacteriaceae urinary tract infection, pneumonia and sepsis. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17:279. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2383-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Du X, Xu X, Yao J, Deng K, Chen S, Shen Z, et al. Predictors of mortality in patients infected with carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Infect Control. 2019;47:1140–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2019.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tamma PD, Simner PJ. Phenotypic detection of carbapenemase-producing organisms from clinical isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2018 doi: 10.1128/jcm.01140-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mentasti M, Prime K, Sands K, Khan S, Wootton M. Rapid detection of IMP, NDM, VIM, KPC and OXA-48-like carbapenemases from Enterobacteriales and Gram-negative non-fermenter bacteria by real-time PCR and melt-curve analysis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38:2029–2036. doi: 10.1007/s10096-019-03637-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoyos-Mallecot Y, Cabrera-Alvargonzalez JJ, Miranda-Casas C, Rojo-Martin MD, Liebana-Martos C, Navarro-Mari JM. MALDI-TOF MS, a useful instrument for differentiating metallo-beta-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas spp. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2014;58:325–329. doi: 10.1111/lam.12203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baeza LL, Pfennigwerth N, Greissl C, Gottig S, Saleh A, Stelzer Y, et al. Comparison of five methods for detection of carbapenemases in Enterobacterales with proposal of a new algorithm. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;25(10):1286.e9–e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meier M, Hamprecht A. Systematic comparison of four methods for detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales directly from blood cultures. J Clin Microbiol. 2019;57(11):e00709–e719. doi: 10.1128/jcm.00709-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaibani P, Lombardo D, Foschi C, Re MC, Ambretti S. Evaluation of five carbapenemase detection assays for Enterobacteriaceae harbouring blaKPC variants associated with ceftazidime/avibactam resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2020 doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galani I, Karaiskos I, Souli M, Papoutsaki V, Galani L, Gkoufa A, et al. Outbreak of KPC-2-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae endowed with Ceftazidime–avibactam resistance mediated through a VEB-1-mutant (VEB-25), Greece, September to October 2019. Euro surveill. 2020;25(3):2000028. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gill CM, Lasko MJ, Asempa TE, Nicolau DP. Evaluation of the EDTA-Modified Carbapenem inactivation method for detecting metallo-β-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58(6):e02015–e2019. doi: 10.1128/jcm.02015-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eichenberger EM, Thaden JT. Epidemiology and mechanisms of resistance of extensively drug resistant Gram-negative bacteria. Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland) 2019;8:37. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics8020037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Duin D, Doi Y. The global epidemiology of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Virulence Orgo. 2017;8(4):460–469. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2016.1222343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grundmann H, Glasner C, Albiger B, Aanensen DM, Tomlinson CT, Andrasevic AT, et al. Occurrence of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli in the European survey of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (EuSCAPE): a prospective, multinational study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:153–163. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(16)30257-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kazmierczak KM, de Jonge BLM, Stone GG, Sahm DF. In vitro activity of ceftazidime/avibactam against isolates of Pseudomonasaeruginosa collected in European countries: INFORM global surveillance 2012–15. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73:2777–2781. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karampatakis T, Tsergouli K, Politi L, Diamantopoulou G, Iosifidis E, Antachopoulos C, et al. Molecular epidemiology of endemic carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria in an intensive care unit. Microb Drug Resist. 2019;25:712–716. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2018.0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saharman YR, Pelegrin AC, Karuniawati A, Sedono R, Aditianingsih D, Goessens WHF, et al. Epidemiology and characterisation of carbapenem-non-susceptible Pseudomonasaeruginosa in a large intensive care unit in Jakarta. Indonesia Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2019;54:655–660. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2019.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galani I, Karaiskos I, Karantani I, Papoutsaki V, Maraki S, Papaioannou V, et al. Epidemiology and resistance phenotypes of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Greece, 2014 to 2016. Eurosurveillance. 2018;23:1700775. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.30.1700775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Papadimitriou-Olivgeris M, Bartzavali C, Lambropoulou A, Solomou A, Tsiata E, Anastassiou ED, et al. Reversal of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae epidemiology from blaKPC- to blaVIM-harbouring isolates in a Greek ICU after introduction of ceftazidime/avibactam. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74:2051–2054. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Munoz-Price LS, Poirel L, Bonomo RA, Schwaber MJ, Daikos GL, Cormican M, et al. Clinical epidemiology of the global expansion of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:785–796. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70190-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baroud M, Dandache I, Araj GF, Wakim R, Kanj S, Kanafani Z, et al. Underlying mechanisms of carbapenem resistance in extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli isolates at a tertiary care centre in Lebanon: role of OXA-48 and NDM-1 carbapenemases. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2013;41:75–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doumith M, Ellington MJ, Livermore DM, Woodford N. Molecular mechanisms disrupting porin expression in ertapenem-resistant Klebsiella and Enterobacter spp. Clinical isolates from the UK. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63(4):659–667. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pulzova L, Navratilova L, Comor L. Alterations in outer membrane permeability favor drug-resistant phenotype of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microb Drug Resist. 2017;23:413–420. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2016.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dupont H, Gaillot O, Goetgheluck A-S, Plassart C, Emond J-P, Lecuru M, et al. Molecular characterization of carbapenem-nonsusceptible Enterobacterial isolates collected during a prospective interregional survey in france and susceptibility to the novel Ceftazidime–avibactam and aztreonam–avibactam combinations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;60:215–221. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01559-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Castanheira M, Deshpande LM, Costello A, Davies TA, Jones RN. Epidemiology and carbapenem resistance mechanisms of carbapenem-non-susceptible Pseudomonasaeruginosa collected during 2009–11 in 14 European and Mediterranean countries. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:1804–1814. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Botelho J, Grosso F, Peixe L. Antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonasaeruginosa–mechanisms, epidemiology and evolution. Drug Resist Updat. 2019;44:100640. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2019.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Castanheira M, Mills JC, Farrell DJ, Jones RN. Mutation-driven β-lactam resistance mechanisms among contemporary ceftazidime-nonsusceptible Pseudomonasaeruginosa isolates from U.S. hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(11):6844–6850. doi: 10.1128/aac.03681-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCracken MG, Adam HJ, Blondeau JM, Walkty AJ, Karlowsky JA, Hoban DJ, et al. Characterization of carbapenem-resistant and XDR Pseudomonasaeruginosa in Canada results of the CANWARD study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019 doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Galani I, Papoutsaki V, Karantani I, Karaiskos I, Galani L, Adamou P, et al. In vitro activity of ceftolozane/tazobactam alone and in combination with amikacin against MDR/XDR Pseudomonasaeruginosa isolates from Greece. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2020 doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karlowsky JA, Lob SH, Kazmierczak KM, Hawser SP, Magnet S, Young K, et al. In vitro activity of imipenem/relebactam against Gram-negative ESKAPE pathogens isolated in 17 European countries: 2015 SMART surveillance programme. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73:1872–1879. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Young K, Painter RE, Raghoobar SL, Hairston NN, Racine F, Wisniewski D, et al. In vitro studies evaluating the activity of imipenem in combination with relebactam against Pseudomonasaeruginosa. BMC Microbiol. 2019;19:150. doi: 10.1186/s12866-019-1522-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wong D, Nielsen TB, Bonomo RA, Pantapalangkoor P, Luna B, Spellberg B. Clinical and pathophysiological overview of acinetobacter infections: a century of challenges. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017;30:409–447. doi: 10.1128/cmr.00058-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bonnin RA, Nordmann P, Poirel L. Screening and deciphering antibiotic resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii: a state of the art. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2013;11:571–583. doi: 10.1586/eri.13.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pournaras S, Dafopoulou K, Del Franco M, Zarkotou O, Dimitroulia E, Protonotariou E, et al. Predominance of international clone 2 OXA-23-producing-Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates in Greece, 2015: results of a nationwide study. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2017;49:749–753. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hamidian M, Nigro SJ. Emergence, molecular mechanisms and global spread of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Microbial genomics. 2019;5:e000306. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mohd Sazlly Lim S, Sime FB, Roberts JA. Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections: current evidence on treatment options and the role of pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics in dose optimisation. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2019;53(6):726–745. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2019.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mushtaq S, Vickers A, Woodford N, Livermore DM. WCK 4234, a novel diazabicyclooctane potentiating carbapenems against Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter with class A, C and D β-lactamases. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72:1688–1695. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Barnes MD, Kumar V, Bethel CR, Moussa SH, O’Donnell J, Rutter JD, et al. Targeting multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter spp: sulbactam and the diazabicyclooctenone β-Lactamase inhibitor ETX2514 as a novel therapeutic agent. MBio. 2019;10:e00159–e219. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00159-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhanel GG, Lawrence CK, Adam H, Schweizer F, Zelenitsky S, Zhanel M, et al. Imipenem-relebactam and meropenem-vaborbactam: two novel carbapenem-beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations. Drugs. 2018;78:65–98. doi: 10.1007/s40265-017-0851-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lob SH, Hoban DJ, Sahm DF, Badal RE. Regional differences and trends in antimicrobial susceptibility of Acinetobacter baumannii. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2016;47:317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Suetens C, Latour K, Kärki T, Ricchizzi E, Kinross P, Moro ML, et al. Prevalence of healthcare-associated infections, estimated incidence and composite antimicrobial resistance index in acute care hospitals and long-term care facilities: results from two European point prevalence surveys, 2016 to 2017. Euro Surveill. 2018;23:1800516. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.46.1800516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Karampatakis T, Antachopoulos C, Tsakris A, Roilides E. Molecular epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in Greece: an extended review (2000–2015) Future Microbiol. 2017;12:801–815. doi: 10.2217/fmb-2016-0200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Karlowsky JA, Kazmierczak KM, Bouchillon SK, de Jonge BLM, Stone GG, Sahm DF. In Vitro activity of Ceftazidime–avibactam against clinical isolates of Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonasaeruginosa collected in Latin American countries: results from the INFORM global surveillance program, 2012–2015. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019 doi: 10.1128/aac.01814-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jayol A, Nordmann P, Poirel L, Dubois V. Ceftazidime/avibactam alone or in combination with aztreonam against colistin-resistant and carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73:542–544. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Castanheira M, Huband MD, Mendes RE, Flamm RK. Meropenem-vaborbactam tested against contemporary Gram-negative isolates collected worldwide during 2014, including carbapenem-resistant, KPC-producing, multidrug-resistant, and extensively drug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61:e00567–e617. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00567-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Haidar G, Clancy CJ, Chen L, Samanta P, Shields RK, Kreiswirth BN, et al. Identifying spectra of activity and therapeutic niches for Ceftazidime–avibactam and Imipenem-relebactam against carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017 doi: 10.1128/aac.00642-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Winkler ML, Papp-Wallace KM, Bonomo RA. Activity of ceftazidime/avibactam against isogenic strains of Escherichia coli containing KPC and SHV beta-lactamases with single amino acid substitutions in the omega-loop. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:2279–2286. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Livermore DM, Warner M, Jamrozy D, Mushtaq S, Nichols WW, Mustafa N, et al. In vitro selection of Ceftazidime–avibactam resistance in Enterobacteriaceae with KPC-3 carbapenemase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:5324–5330. doi: 10.1128/aac.00678-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shields RK, Chen L, Cheng S, Chavda KD, Press EG, Snyder A, et al. Emergence of Ceftazidime–avibactam resistance due to plasmid-borne blakpc-3 mutations during treatment of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017 doi: 10.1128/aac.02097-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pogue JM, Bonomo RA, Kaye KS. Ceftazidime/avibactam, meropenem/vaborbactam, or both? clinical and formulary considerations. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:519–524. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mueller L, Masseron A, Prod'Hom G, Galperine T, Greub G, Poirel L, et al. Phenotypic, biochemical and genetic analysis of KPC-41, a KPC-3 variant conferring resistance to Ceftazidime–avibactam and exhibiting reduced carbapenemase activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019 doi: 10.1128/aac.01111-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Haidar G, Clancy CJ, Shields RK, Hao B, Cheng S, Nguyen MH. Mutations in blaKPC-3 that confer Ceftazidime–avibactam resistance encode novel KPC-3 variants that function as extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017 doi: 10.1128/aac.02534-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shields RK, Nguyen MH, Press EG, Chen L, Kreiswirth BN, Clancy CJ. In vitro selection of meropenem resistance among Ceftazidime–avibactam-resistant, meropenem-susceptible Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates with variant KPC-3 carbapenemases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017 doi: 10.1128/aac.00079-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wilson WR, Kline EG, Jones CE, Morder KT, Mettus RT, Doi Y, et al. Effects of KPC variant and porin genotype on the in vitro activity of meropenem-vaborbactam against carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019;63:e02048–e2118. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02048-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ackley R, Roshdy D, Meredith J, Minor S, Anderson WE, Capraro GA, et al. Meropenem-vaborbactam versus Ceftazidime–avibactam for treatment of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020 doi: 10.1128/aac.02313-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oliva A, D'Abramo A, D'Agostino C, Iannetta M, Mascellino MT, Gallinelli C, et al. Synergistic activity and effectiveness of a double-carbapenem regimen in pandrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:1718–1720. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Souli M, Karaiskos I, Masgala A, Galani L, Barmpouti E, Giamarellou H. Double-carbapenem combination as salvage therapy for untreatable infections by KPC-2-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;36:1305–1315. doi: 10.1007/s10096-017-2936-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Emre S, Moroğlu Ç, Yıldırmak T, Şimşek F, Arabacı Ç, Özkaya Ö, et al. Combination antibiotic therapy in pan-resistant klebsiella pneumoniae infection: a report of two cases. Klimik Dergisi. 2018;31:169–172. doi: 10.5152/kd.2018.40. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Oliva A, Mascellino MT, Cipolla A, D'Abramo A, De Rosa A, Savinelli S, et al. Therapeutic strategy for pandrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae severe infections: short-course treatment with colistin increases the in vivo and in vitro activity of double carbapenem regimen. Int J Infect Dis. 2015;33:132–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2015.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Garcia-Fernandez S, Garcia-Castillo M, Bou G, Calvo J, Cercenado E, Delgado M, et al. Activity of ceftolozane–tazobactam against Pseudomonasaeruginosa and Enterobacterales isolates recovered in intensive care units in Spain: the SUPERIOR multicentre study. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2019.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pfaller MA, Huband MD, Mendes RE, Flamm RK, Castanheira M. In vitro activity of meropenem/vaborbactam and characterisation of carbapenem resistance mechanisms among carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae from the 2015 meropenem/vaborbactam surveillance programme. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2018;52:144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Karaiskos I, Galani I, Souli M, Giamarellou H. Novel beta-lactam-beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations: expectations for the treatment of carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative pathogens. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2019;15:133–149. doi: 10.1080/17425255.2019.1563071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kazmierczak KM, Bradford PA, Stone GG, de Jonge BLM, Sahm DF. In Vitro Activity of Ceftazidime–avibactam and aztreonam–avibactam against OXA-48-carrying enterobacteriaceae isolated as part of the international network for optimal resistance monitoring (INFORM) global surveillance program from 2012 to 2015. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62:e00592–e618. doi: 10.1128/aac.00592-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shaw E, Rombauts A, Tubau F, Padulles A, Camara J, Lozano T, et al. Clinical outcomes after combination treatment with ceftazidime/avibactam and aztreonam for NDM-1/OXA-48/CTX-M-15-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73:1104–1106. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Davido B, Fellous L, Lawrence C, Maxime V, Rottman M, Dinh A. Ceftazidime–avibactam and aztreonam, an interesting strategy to overcome beta-lactam resistance conferred by Metallo-beta-Lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonasaeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61:e01008–e1017. doi: 10.1128/aac.01008-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Emeraud C, Escaut L, Boucly A, Fortineau N, Bonnin RA, Naas T, et al. Aztreonam plus clavulanate, tazobactam or avibactam for the treatment of metallo-beta-lactamase-producing-Gram negative related infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019;63:e00010–19. doi: 10.1128/aac.00010-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Falcone M, Daikos GL, Tiseo G, Bassoulis D, Giordano C, Galfo V, et al. Efficacy of Ceftazidime–avibactam plus aztreonam in patients with bloodstream infections caused by MBL-producing Enterobacterales. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Denervaud-Tendon V, Poirel L, Connolly LE, Krause KM, Nordmann P. Plazomicin activity against polymyxin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, including MCR-1-producing isolates. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72:2787–2791. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pages JM, Peslier S, Keating TA, Lavigne JP, Nichols WW. Role of the outer membrane and porins in susceptibility of beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae to Ceftazidime–avibactam. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;60:1349–1359. doi: 10.1128/aac.01585-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shields RK, Clancy CJ, Hao B, Chen L, Press EG, Iovine NM, et al. Effects of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase subtypes, extended-spectrum beta-lactamases, and porin mutations on the in vitro activity of Ceftazidime–avibactam against carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(9):5793–5797. doi: 10.1128/aac.00548-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Castanheira M, Doyle TB, Hubler C, Sader HS, Mendes RE. Ceftazidime–avibactam activity against a challenge set of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales: Ompk36 L3 alterations and β-lactamases with ceftazidime hydrolytic activity lead to elevated MIC values. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;56:106011. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yasmin M, Marshall S, Jacobs M, Rhoads DD, Rojas LJ, Perez F, et al. 610 Meropenem-vaborbactam (MV) In vitro activity against carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKP) isolates with outer membrane porin gene mutations. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019 doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofz360.679. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Canver MC, Satlin MJ, Westblade LF, Kreiswirth BN, Chen L, Robertson A, et al. Activity of Imipenem-relebactam and comparator agents against genetically characterized isolates of carbapenem-resistant. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019;63:e00672–e719. doi: 10.1128/aac.00672-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dulyayangkul P, Douglas EJA, Lastovka F, Avison MB. Resistance to ceftazidime/avibactam plus meropenem/vaborbactam when both are used together achieved in four steps from metallo-β-lactamase negative Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020 doi: 10.1128/aac.00409-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhanel GG, Baxter MR, Adam HJ, Sutcliffe J, Karlowsky JA. In vitro activity of eravacycline against 2213 Gram-negative and 2424 Gram-positive bacterial pathogens isolated in Canadian hospital laboratories: CANWARD surveillance study 2014–2015. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2018;91:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2017.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Morrissey I, Olesky M, Hawser S, Lob SH, Karlowsky JA, Corey GR, et al. In vitro activity of eravacycline against Gram-negative bacilli isolated in clinical laboratories worldwide from 2013 to 2017. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020;64:e01699–e1719. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01699-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pontikis K, Karaiskos I, Bastani S, Dimopoulos G, Kalogirou M, Katsiari M, et al. Outcomes of critically ill intensive care unit patients treated with fosfomycin for infections due to pandrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative bacteria. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2014;43:52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Perdigao Neto LV, Oliveira MS, Martins RCR, Marchi AP, Gaudereto JJ, da Costa L, et al. Fosfomycin in severe infections due to genetically distinct pan-drug-resistant Gram-negative microorganisms: synergy with meropenem. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019;74:177–181. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kaye KS, Rice LB, Dane AL, Stus V, Sagan O, Fedosiuk E, et al. Fosfomycin for Injection (ZTI-01) Versus piperacillin-tazobactam for the treatment of complicated urinary tract infection including acute pyelonephritis: ZEUS, a phase 2/3 randomized trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2019 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Falagas ME, Athanasaki F, Voulgaris GL, Triarides NA, Vardakas KZ. Resistance to fosfomycin: mechanisms, frequency and clinical consequences. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2019;53:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Brennan-Krohn T, Pironti A, Kirby JE. Synergistic activity of colistin-containing combinations against colistin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62:e00873–e918. doi: 10.1128/aac.00873-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.MacNair CR, Stokes JM, Carfrae LA, Fiebig-Comyn AA, Coombes BK, Mulvey MR, et al. Overcoming mcr-1 mediated colistin resistance with colistin in combination with other antibiotics. Nature Communications. 2018;9:458. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-02875-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Erturk Sengel B, Altinkanat Gelmez G, Soyletir G, Korten V. In vitro synergistic activity of fosfomycin in combination with meropenem, amikacin and colistin against OXA-48 and/or NDM-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Chemother. 2020 doi: 10.1080/1120009x.2020.1745501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Band VI, Hufnagel DA, Jaggavarapu S, Sherman EX, Wozniak JE, Satola SW, et al. Antibiotic combinations that exploit heteroresistance to multiple drugs effectively control infection. Nature Microbiology. 2019;4:1627–1635. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0480-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Buehrle DJ, Shields RK, Chen L, Hao B, Press EG, Alkrouk A, et al. Evaluation of the in vitro activity of Ceftazidime–avibactam and ceftolozane–tazobactam against meropenem-resistant Pseudomonasaeruginosa isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60:3227–3231. doi: 10.1128/aac.02969-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wi YM, Greenwood-Quaintance KE, Schuetz AN, Ko KS, Peck KR, Song J-H, et al. Activity of ceftolozane–tazobactam against carbapenem-resistant, non-carbapenemase-producing Pseudomonasaeruginosa and associated resistance mechanisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;62:e01970–e2017. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01970-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mirza HC, Hortac E, Kocak AA, Demirkaya MH, Yayla B, Guclu AU, et al. In vitro activity of ceftolozane–tazobactam and Ceftazidime–avibactam against clinical isolates of meropenem-non-susceptible Pseudomonasaeruginosa: a two-center study. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2019.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Grupper M, Sutherland C, Nicolau DP. Multicenter evaluation of Ceftazidime–avibactam and ceftolozane–tazobactam inhibitory activity against meropenem-nonsusceptible Pseudomonasaeruginosa from blood, respiratory tract, and wounds. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017 doi: 10.1128/aac.00875-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sader HS, Mendes RE, Pfaller MA, Shortridge D, Flamm RK, Castanheira M. Antimicrobial activities of aztreonam–avibactam and comparator agents against contemporary (2016) clinical Enterobacteriaceae isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62:e01856–e1917. doi: 10.1128/aac.01856-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Asempa TE, Nicolau DP, Kuti JL. Carbapenem-nonsusceptible Pseudomonasaeruginosa isolates from intensive care units in the United States: a potential role for new beta-lactam combination agents. J Clin Microbiol. 2019 doi: 10.1128/jcm.00535-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Alvarez Lerma F, Munoz Bermudez R, Grau S, Gracia Arnillas MP, Sorli L, Recasens L, et al. Ceftolozane–tazobactam for the treatment of ventilator-associated infections by colistin-resistant Pseudomonasaeruginosa. Rev Esp Quimioter. 2017;30:224–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Fraile-Ribot PA, Cabot G, Mulet X, Perianez L, Martin-Pena ML, Juan C, et al. Mechanisms leading to in vivo ceftolozane/tazobactam resistance development during the treatment of infections caused by MDR Pseudomonasaeruginosa. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73:658–663. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Cabot G, Bruchmann S, Mulet X, Zamorano L, Moya B, Juan C, et al. Pseudomonasaeruginosa ceftolozane–tazobactam resistance development requires multiple mutations leading to overexpression and structural modification of AmpC. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:3091–3099. doi: 10.1128/aac.02462-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Fraile-Ribot P, Zamorano L, Orellana R, Barrio-Tofino ED, Sanchez-Diener I, Cortes-Lara S, et al. Activity of imipenem/relebactam against a large collection of Pseudomonasaeruginosa clinical isolates and isogenic beta-lactam resistant mutants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019 doi: 10.1128/aac.02165-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Poirel L, Ortiz De La Rosa JM, Kieffer N, Dubois V, Jayol A, Nordmann P. Acquisition of extended-spectrum β-lactamase ges-6 leading to resistance to ceftolozane–tazobactam combination in Pseudomonasaeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019 doi: 10.1128/aac.01809-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Karlowsky JA, Kazmierczak KM, de Jonge BLM, Hackel MA, Sahm DF, Bradford PA. In vitro activity of aztreonam–avibactam against Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonasaeruginosa isolated by clinical laboratories in 40 countries from 2012 to 2015. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61:e00472–e517. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00472-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Mikhail S, Singh NB, Kebriaei R, Rice SA, Stamper KC, Castanheira M, et al. Evaluation of the synergy of Ceftazidime–avibactam in combination with meropenem, amikacin, aztreonam, colistin, or fosfomycin against well-characterized multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonasaeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019 doi: 10.1128/aac.00779-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yamano Y. In vitro activity of cefiderocol against a broad range of clinically important Gram-negative bacteria. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69:S544–S551. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sato T, Yamawaki K. Cefiderocol: discovery, chemistry, and in vivo profiles of a novel siderophore cephalosporin. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69:S538–S543. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Dobias J, Dénervaud-Tendon V, Poirel L, Nordmann P. Activity of the novel siderophore cephalosporin cefiderocol against multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;36:2319–2327. doi: 10.1007/s10096-017-3063-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Walsh CC, McIntosh MP, Peleg AY, Kirkpatrick CM, Bergen PJ. In vitro pharmacodynamics of fosfomycin against clinical isolates of Pseudomonasaeruginosa. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:3042–3050. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Louie A, Maynard M, Duncanson B, Nole J, Vicchiarelli M, Drusano GL. Determination of the dynamically linked indices of fosfomycin for Pseudomonasaeruginosa in the hollow fiber infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62:e02627–e2717. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02627-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Abbott IJ, van Gorp E, Wijma RA, Dekker J, Croughs PD, Meletiadis J, et al. Efficacy of single and multiple oral doses of fosfomycin against Pseudomonasaeruginosa urinary tract infections in a dynamic in vitro bladder infection model. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2020;75:1879–1888. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]