Abstract

In recent years, significant development milestones have been reached in the areas of facilitated transport membranes and ionic liquids for CO2 separations, making the combination of these materials an incredibly promising technology platform for gas treatment processes, such as post-combustion and direct CO2 capture from air in buildings, submarines, and spacecraft. The developments in facilitated transport membranes involve consistently surpassing the Robeson upper bound for dense polymer membranes, demonstrating a high CO2 flux across the membrane while maintaining very high selectivity. This mini review focuses on the recent developments of facilitated transport membranes, in particular discussing the challenges and opportunities associated with the incorporation of ionic liquids as fixed and mobile carriers for separations of CO2 at low partial pressures (<1 atm).

Keywords: ionic liquid, facilitated transport membrane, carbon dioxide separation, aprotic heterocyclic anion, mixed matrix membrane, direct air capture

Introduction

To reduce CO2 emissions and mitigate the adverse effects of CO2-induced climate change (Ballantyne et al., 2018), removal of CO2, from atmosphere (Siriwardane et al., 2005) and pre-/post-process streams (Chen et al., 2012; Chen and Ho, 2016), has been a focus of research. The most common technologies to separate CO2 include adsorption (e.g., zeolites), absorption (e.g., liquid amines), and membranes in pre- and post-combustion CO2 capture. Pre-combustion capture is the removal of CO2 from pre-process gas mixtures (%CO2 > 20) such as syngas or biogas and typically involves separation pairs such as CO2/H2 and CO2/CH4, respectively. Post-combustion capture is the removal of CO2 from flue gas (5 < %CO2 <15) and typically involves a CO2/N2 separation pair. The energy demand is highest for adsorption and lowest for membrane separations. Zeolites are physisorption-based porous solid materials that are typically used in adsorption such as the removal of CO2 from air in spacecraft (Knox et al., 2017). Zeolites have high CO2 capacity, but suffer from extreme sensitivity to moisture (Chue et al., 1995; Cmarik and Knox, 2018). Membranes are energy-efficient, but struggle with the permeability/selectivity trade-off as described by Robeson (1991).

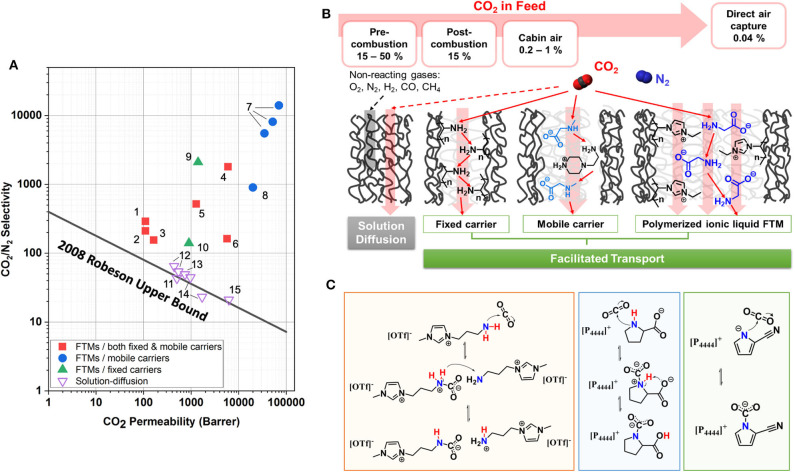

The inherent limitation of polymeric membranes was defined in 1991, demonstrating the upper bound for the CO2/CH4 separation pair (Robeson, 1991). In 2008, Robeson redefined the upper bound in consideration of improvements in membrane technology. He also included CO2/H2 and CO2/N2 separations (Robeson, 2008). Most polymeric membranes operate on a pressure-driven solution–diffusion model and are limited in performance by the Robeson upper bound. Recently, facilitated transport membranes (FTMs) have been shown to surpass the Robeson upper bound. FTMs achieve high permeabilities without sacrificing selectivity, or vice versa. Figure 1A provides a perspective of FTMs in comparison to common membranes; this Robeson plot demonstrates the relation between CO2/N2 selectivity and CO2 permeability.

Figure 1.

(A) FTMs with ILs in comparison to solution–diffusion membranes on Robeson plot for CO2/N2 separation. References for data: (1) (Chen and Ho, 2016), (2) (Chen et al., 2016), (3) (Han et al., 2018), (4) (Zou and Ho, 2006), (5) (El-Azzami and Grulke, 2009), (6) (Han et al., 2018), (7) (Moghadam et al., 2017a), (8) (Moghadam et al., 2017b), (9) (Kamio et al., 2020), (10) (McDanel et al., 2015), (11) (Teodoro et al., 2018), (12) (Tomé et al., 2018), (13) (Tomé et al., 2014), (14) (Scovazzo, 2009), (15) (Jindaratsamee et al., 2012). The selectivity and permeability data of FTMs shown in this figure are available in Table 1. (B) Schematics of CO2 transport in solution–diffusion membranes (feed with >15% CO2) and FTMs (feed with <15% CO2). Specific examples of polyvinylamine studied by Tong and Ho (2017) and amino acid salt by Chen and Ho (2016) illustrate the fixed carrier and mobile carrier FTMs, respectively. As an example to FTM with a polymerized IL, polymerized imidazolium with glycinate counter ion studied by Kamio et al. (2020) is also shown. (C) Reaction schemes for CO2-reactive ILs. Left: n-(3-aminopropyl)-n-methyl-imidazolium triflate. A zwitterion (-) forms by the formation of the CN bond in the first step, followed by the transfer of proton from the zwitterion complex to another amine, thus forming ammonium and carbamate ions. Middle: tetrabutyl phosphonium prolinate, [P4444][Pro]. Zwitterion formation in the first step is followed by an intramolecular hydrogen transfer that results in carbocylic acid. Right: tetrabutyl phosphonium 2-cyanopyrrolide, [P4444][2-CNpyr]. Nucleophilic addition of CO2 to AHA nitrogen forming carbamate with no hydrogen transfer involved.

FTMs incorporate a reactive component that acts as a CO2 carrier, such as an amine-bearing polymer or a small molecule embedded within the polymer matrix. Earlier examples of FTMs based on polyamines and alkanolamines can be found in the review by Tong and Ho (2016). Very recent applications of FTMs include the CO2 capture from flue gas in pilot scale as demonstrated by Salim et al. (2018), Han et al. (2019), and Chen et al. (2020). The review here focuses on the incorporation of ionic liquids (ILs) to polymeric films. In particular, this review focuses on FTMs with ILs studied in the last 4 years, since the review by Tome and Marrucho (2016) on the IL-based materials for CO2 separations. ILs are versatile solvents with high CO2 solubilities that have been incorporated into a number of host materials. A brief background to FTMs and ILs is provided, followed by a review of the most recent FTMs with ILs either as fixed or mobile carriers, emphasizing the existing challenges and opportunities.

Gas Transport Mechanism In FTMs

FTMs combine the selection capability of reactive processes with the reduced mass, volume, and energy advantages of membranes (Tong and Ho, 2016). The reactive component of the membrane, known as a carrier, reversibly reacts with CO2 to produce a CO2 carrier complex with its own concentration gradient across the membrane. At the permeate side, the CO2 complexation reaction is reversed as a result of low partial pressure of CO2 and the carrier is regenerated by releasing the captured CO2. Figure 1B illustrates the CO2 transport mechanism in FTMs in comparison to other polymeric membranes that achieve separations by solution–diffusion.

In solution–diffusion membranes, gas molecules diffuse through the free volume of the membrane that is created by the chain-to-chain spacing. The steady-state flux of CO2 is related to the segmental chain motion of the polymer and is expressed by Equation (1) (Zolandz and Fleming, 1992):

| (1) |

where JCO2 is the steady-state CO2 flux, DCO2 is the diffusion coefficient of CO2 in the membrane material, CCO2,f and CCO2,p are the feed and permeate CO2 concentrations, respectively, and l is the thickness of the membrane. For an FTM, an additional term is added to account for carrier-mediated transport of CO2 as in Equation (2) (Rea et al., 2019):

| (2) |

where DCO2−C is the “effective diffusivity” modeling the combination of transmembrane CO2 complex diffusion and the CO2 hopping mechanism across the carriers. CCO2−C,f and CCO2−C,p are the CO2 complex concentration at the feed and permeate site, respectively. FTMs have two subgroups: mobile carrier and fixed carrier. For fixed carrier FTMs, the carrier is immobilized and the DCO2−C only represents the hopping mechanism, where CO2 hops from one active site to another down the concentration gradient, as illustrated in Figure 1B (Cussler et al., 1989). For mobile carrier FTMs, the combination of Fickian (solution–diffusion mechanism), hopping, and complex diffusion (vehicular motion) pathways greatly enhances CO2 permeation as opposed to fixed carrier FTMs and conventional solution–diffusion membranes.

Permeability, PCO2, of a membrane is determined by Equation (3) (Zolandz and Fleming, 1992):

| (3) |

where ΔPCO2 is the pressure drop of CO2 across the membrane. SCO2 is the solubility of CO2 in the membrane matrix that, along with diffusivity, governs the permeability of a membrane. With CO2 having the ability to complex with carriers, this additional chemical pathway greatly enhances the diffusivity and especially the solubility in FTMs in comparison with conventional solution–diffusion-based membranes. For thin films, and often for FTMs, the membrane thickness is difficult to define, and therefore, the permeance is often reported instead of permeability. Permeance is the flux of gas (i.e., CO2) per unit permeation driving force with units of GPU (gas permeation unit), equivalent to 1 × 10−6 cm3 (STP)·cm−2·s−1·(cm Hg)−1. Permeability has units of Barrers (1 Barrer = 1 GPU·μm).

Selectivity, α, is estimated by Equation (4) (Zolandz and Fleming, 1992):

| (4) |

where i represents CO2 and j represents the other non-CO2 component of the separation pair.

Developments Toward The Il-Based FTMs

ILs are salts that melt below 100°C. It is shown that increased alkyl chain length and fluorination significantly improve CO2 solubility in some ILs. The free volume of the liquid, originating from the weak anion–cation interactions and bulky structure, promotes CO2 solvation (Anthony et al., 2002). ILs are amenable to chemical functionalization to improve CO2 capacity. ILs with an amine-functionalized cation are reported to have CO2 capacities in the range of 0.5 mol CO2 per mol of IL (Bates et al., 2002). Most ILs with amino acid anions (AAs) (Ohno and Fukumoto, 2007; Gurkan B.E. et al., 2010) and aprotic heterocyclic anions (AHAs), (Gurkan B. et al., 2010) achieve equimolar CO2 capacities. More recently, dual functionalized ILs composed of diethylenetriamine cation and AHAs such as imidazolide, pyrazolide, and triazolide exceeded equimolar (~2 mol CO2 per mol IL), (Wu et al., 2019). Figure 1C illustrates the CO2 reactions with functionalized ILs. It should be emphasized that reaction enthalpy and most physical properties, not just the CO2 absorption capacity, can be tuned in ILs. Lastly, ILs have negligible volatility and higher thermal stabilities than molecular solvents. Therefore, ILs are considered promising alternatives to amines in absorptive CO2 separation, due to energy-efficient solvent regeneration, non-corrosivity, and high degradation temperature.

The main challenge using ILs to separate CO2 has been their high viscosity, usually caused by Coulombic interactions and hydrogen bonding. In this regard, the relatively low viscosity AHA ILs are the most promising, as they lack hydrogen bonding. Li et al. (2019) reported protic ILs with low viscosities (2–27 cP at 30°C) that achieve similar CO2 absorption capacities, especially in the presence of water. ILs have also been studied in the context of supported IL membranes (SILM). Cowan et al. (2016) and Bara et al. (2010) provide comprehensive reviews of SILMs for CO2 separations. ILs are especially advantageous for SILMs as they do not evaporate. However, the stability of SILMs under high transmembrane pressures remains to be a challenge as the IL may get pushed out of the micropores over time. A thicker membrane support (50–150 μm) is generally adopted to suppress this potential leakage; however, CO2 flux is significantly reduced due to the increased length of diffusion. One potential solution to this problem is to confine the IL media in nanopores, as the capillary force holding the ILs is high and far exceeding the pressure gradient imposed on the membrane. This resolves the leakage issue, and still renders a high CO2 flux through the membrane. Among various nanomaterials, graphene oxide (GO) nanosheets received great attention due to their high flexibility, good mechanical strength, and easy processability. Lin et al. (2019) confined a deep eutectic solvent that is selective to CO2, similar to ILs, into GO nanoslits as a highly CO2-philic GO-SILM. The group reported a structural change in the liquid that better promotes CO2 transport, even though the liquid is not reactive with CO2. This idea of ultrathin GO-SILMs greatly shortens the diffusion pathway of CO2 within the membrane, providing promise for the use of viscous ILs in membranes. Alternative strategies of utilizing ILs in membrane separations focused on polymer-IL composite, gelled IL, and polymerized IL membranes (Tome and Marrucho, 2016). A detailed review on the IL-based materials for CO2 separations by Tome and Marrucho (2016) discusses the prospects of these materials. The majority of these studies focus on CO2 separations for coal-fired power plants. In applications where CO2 needs to be separated from air, such as cabin air in submarines, spacecraft, or buildings, the partial pressure of CO2 is not sufficient for most of these membranes to efficiently perform. The only type of membrane that may meet the needs for such dilute separations are FTMs. Reactive ILs are promising to incorporate into FTMs because they provide tunable reaction chemistry and CO2 diffusivity with no vapor pressure.

FTMs With Fixed Carriers

Polymers with CO2-reactive groups such as polyallylamine (Cai et al., 2007; Yegani et al., 2007; Zhao and Ho, 2012a; Prasad and Mandal, 2018), polyethyleneimine (Matsuyama et al., 1999; Xin et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2020), and poly(vinyl amine) (Qiao et al., 2015; Chen and Ho, 2016; Chen et al., 2016; Tong and Ho, 2017) have attracted particular attention as materials for FTMs. In fixed carrier FTMs, the reactive functional groups are anchored to the polymer backbone, which provides better structural integrity compared to FTMs with mobile carriers. In an effort to combine the high CO2 solubilities of ILs and improve the mechanical stability over SILMs, polymerized IL (PIL) membranes have been considered. Earlier examples of PILs demonstrated CO2/N2 selectivities comparable to SILMs, but with lower permeabilities. Several strategies improving CO2 transport in PILs include PIL/IL composites, PIL copolymers, and PIL/IL/inorganic particle mixed matrix membranes (MMMs). Out of these, MMMs are considered the most promising as they combine (i) the gas separation capability, (ii) thermal stability, and (iii) durability of inorganic filler materials with (iv) the good mechanical properties combined with (v) the processability of polymeric materials (Seoane et al., 2015; Tome and Marrucho, 2016).

Inorganic fillers such as zeolites (Shindo et al., 2014), hydrotalcite (Liao et al., 2014), mesoporous silica, and silica particles (Xing and Ho, 2011; Xin et al., 2016); organic fillers such as carboxylic acid nanogels (Li et al., 2015), polyaniline rods (Zhao et al., 2012, 2013; Li et al., 2015), carbon nanotubes (CNTs) (Deng and Hagg, 2014; Han et al., 2018), amine functionalized CNTs (Zhao et al., 2014), and graphene (Wang et al., 2016); and hybrid materials such as metal organic frameworks (MOFs) (Shen et al., 2016) and zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (ZIFs) (Zhao et al., 2015) have been used to date in MMMs and facilitated transport MMMs (FTMMMs) mainly for CO2/N2 and CO2/CH4 separations. The poor interfacial adhesion between fillers and polymers remains a challenge in this field, as this poor adhesion often results in gas percolation at defects, leading to a decrease in selectivity (Chung et al., 2007; Rezakazemi et al., 2014). Compared with inorganic fillers, hybrid porous materials such as MOFs and ZIFs that consist of metal ions or clusters and organic linkers show improved interfacial interaction with the polymeric matrix (Zhao et al., 2015).

Ma et al. (2016) reported three-component FTMMMs: (i) a porous MOF filler, NH2-MIL-101(Cr); (ii) a cation-functionalized reactive IL confined within the MOF; and (iii) polydioxane with intrinsic microporosity (PIM-1) as the matrix. With loading of the IL-filled MOFs at 5 wt.%, this novel fabrication led to excellent separation performance with a permeability of 2,979 Barrer and a CO2/N2 selectivity of 37 (Ma et al., 2016). Recently, Wang et al. (2020) fabricated FTMMMs from pyridine-based porous cationic polymers (PIPs) with Ac−, BF4−, and Cl− anions as fillers in PIM-1. Owing to the π − π interactions between PIP and PIM-1, membranes with minimal defective voids were obtained. CO2 permeabilities in the order of 6,200 Barrer and CO2/N2 selectivities of 40 to 60 were measured. The purposes of ILs in MMMs are as follows: (1) to act as a glue, ensuring good adhesion between the filler and the polymer matrix; (2) to add tunability in CO2 affinity (solubility, diffusivity, and selectivity); and (3) to allow modulation of filler pore structure.

To date, the majority of the studies in CO2 separations with IL-incorporated membranes relied on the physical dissolution of CO2 in non-reactive ILs. Most recent examples include ionic polyimides that incorporate imidazolium-based ILs (Mittenthal et al., 2017). Szala-Bilnik et al. (2019, 2020) studied the impact of the anion in ionic polyimide–IL composite membranes, where the imidazolium functionality is present in both the polymer backbone and the plasticizer. They showed that the ion mobility in pure ILs does not translate to cationic membranes, due to ion coordination with the fixed cation. Nevertheless, the CO2 diffusivity in the membrane can still be tuned by the choice of the anion. Overall, ILs are exciting building blocks for polymeric membranes, with the promise of tunable separation performance for CO2 and even other target gas molecules.

In the context of FTMs, there are no examples for fixed carriers made of an amine-bearing polymerized IL cation. McDanel et al. (2015) reported an IL-based epoxy-amine ion gel FTM. However, the amine moiety was for crosslinking and required moisture to serve as a fixed carrier. Kamio et al. (2020) also reported PIL based FTM, where the counterion of the PIL, glycinate, is CO2 reactive as shown in Figure 1B. This is the first example to date of a fixed carrier made from a CO2-reactive PIL. These gel-type FTMs cannot be fabricated into stand-alone films due to the fragility of the gel, so a porous support or secondary gel network is used for mechanical support. In this study, the group used a new fabrication method that involves creating a gel suspension of the PIL and pressurizing the suspension through a hollow fiber support membrane. The solvent passes through the support layer, leaving behind a thin film of the reactive polymer around the inside of the hollow fiber support. This hollow fiber configuration is highly valuable in industrial applications due to its high membrane area-to-volume ratio. To prevent gel propagation into the pores of the support and clogging, Matsuyama and coworkers used dialysis to remove low-molecular-weight polymer and unreacted monomer from the gel suspension. Design and scalable fabrication of support membranes with pore structure that minimizes clogging remains an interest.

FTMs With Mobile Carriers

Differing from FTMs with fixed carriers, the incorporation of reactive ILs as mobile carriers results in increased CO2 mobility due to both vehicular and hopping transport mechanisms (Doong, 2012). The idea of an IL mobile carrier was pioneered by Matsuyama et al. (1999) amid their developments in liquid absorber-based FTMs in the mid-1990's (Teramoto et al., 1996). They have been active in developing FTMs with liquid absorbers, such as aqueous amines (Teramoto et al., 1996), amino acid salts (Yegani et al., 2007), cation-functionalized ILs (Hanioka et al., 2008), AA ILs (Kasahara et al., 2012), and AHA ILs (Kasahara et al., 2014a; Otani et al., 2016). While the studied FTMs overcome the Robeson upper bound, the measured CO2 flux is limited by slow CO2 diffusion, a result of the high viscosity of the mobile carriers. Therefore, maintaining a reactivity–mobility balance of CO2 is crucial in designing the molecular structure of the mobile carrier.

Kasahara et al. (2014b) reported an IL-impregnated double-network ion gel membrane. One network of the ionomer gel immobilizes the IL mobile carrier, and the other provides mechanical support. These FTMs have stable separation performance with CO2 feed pressures as low as 0.1 kPa. However, the low diffusivity of CO2 necessitates operations under humid conditions and well above room temperature. While the high viscosity of the IL is advantageous against leaching and loss of the liquid, it hinders CO2 diffusivity (Moghadam et al., 2017a,b). Moghadam et al. (2017b) reported the highest CO2 permeability and selectivity to date in an AHA IL-based FTM ([P2221O1][Inda]): 20,000 Barrer and CO2/N2 selectivity of 900 under a feed of 2.5 kPa CO2 and 0% RH at 373K.

Otani et al. (2016) performed molecular dynamics simulations to predict the most effective AHA IL with a phosphonium cation for FTMs based on their viscosity. Preliminary calculations suggested that a pyrrolide or pyrazolide anion would improve transmembrane CO2 transport. However, the authors also emphasized that the anions have large CO2 binding energies, potentially hindering the desorption of CO2, which is a critical design parameter upon designing practical FTMs.

FTMs With Both Mobile and Fixed Carriers

While there are limited examples of FTMs with both the mobile and fixed CO2 carriers, we are not aware of IL-based FTMs under this category. Studies by the Ho group are the only representatives of FTMs with both fixed and mobile carrier to the best of our knowledge. These thin-film composite membranes are made of polyallylamine fixed carrier and solid amine salts as the mobile carrier and studied for CO2 separation from flue gas (Zhao and Ho, 2012b; Chen and Ho, 2016; Chen et al., 2016; Han et al., 2018). High temperatures (>50°C) and humidity are essential factors for these membranes to facilitate transport of CO2, but these factors also promote penetration of the active layer into the support layer. To mitigate this, the Ho group incorporated high-molecular-weight polymers and multiwall carbon nanotubes (MWNTs) in their FTMs (Han et al., 2018). Such amine-bearing FTMs with both fixed and mobile carriers by the Ho group are among the very few FTMs that have been fabricated and tested at pilot scale (Salim et al., 2018; Han et al., 2019).

Table 1 summarizes the CO2 permeabilities and CO2/N2 selectivities of FTMs, specifically those with reactive ILs reported since 2015. It is suggested in both Figure 1A and Table 1 that FTMs with mobile carriers yield the highest permeability and selectivity, in comparison to FTMs with fixed carriers and FTMs with combined fixed and mobile carriers. While these FTMs were specifically designed for CO2 separation from flue gas, they are ideal platforms to work from for CO2 separation from dilute feed streams such as cabin air or atmospheric air. It is very likely that the next-generation FTMs will incorporate reactive ILs into the framework for performances like high permeability and selectivity.

Table 1.

FTMs with superior CO2 permeabilities (PCO2) in units of Barrer and CO2/N2 selectivities (α) reported in the literature within 2015–2020, comparing FTMs with IL or PIL carrier components (shaded) to others with no IL.

| Membrane properties | Experimental conditions | Measured properties | References | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTM type | Composition | D (μm) | Feed CO2:N2 | Pfeed (bar) | T (°C) | RH | PCO2 (Barrer) | α | |

| Mobile carriers | DN gel/ [P4444][Pro] | 150 | 0.1:99.9 | 1 | 30 | 30 | 35,000 | 5,500 | Moghadam et al., 2017a |

| 70 | 52,000 | 8,100 | |||||||

| 0.05:99.95 | 70 | 70,000 | 14,000 | ||||||

| DN gel/[P2221O1] [Inda] | 80 | 2.5:97.5 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 20,000 | 900 | Moghadam et al., 2017b | |

| Fixed carriers | Poly([Veim] [Gly]) on PSf | 4a | 0.1:99.9 | 1 | 50 | 80 | 5600* (1400) | 2,100 | Kamio et al., 2020 |

| Amine-crosslinked poly-[Im][TFSI] epoxy resin/[Emim] [DCA] | 50 | 2.5:97.5 | 1.02 | 20 | 95 | 900 | 140 | McDanel et al., 2015 | |

| Combined fixed and mobile carriers | PVAm/piperazine glycinate on PES | 0.1 | 20:80 | 1.1 | 57 | 100 | 110* (1100) | 290 | Chen and Ho, 2016 |

| PVAm/piperazine glycinate on zeolite Y on PES | 0.1 | 20:80 | 1.1 | 57 | 100 | 110* (1100) | 210 | Chen et al., 2016 | |

| MWNT-reinforced PVAm/PZEA-Sar | 0.17 | 20:80 | 1 | 57 | 100 | 166* (975) | 155 | Han et al., 2018 | |

The symbol

represents the permeabilities calculated from the reported permeance given in parenthesis in units of GPU.

Value includes 3 μm diffusion resistance layer; PVAm, poly(vinylamine); PES, poly(ether sulfone); [PZEA][Sar], 2-(1-piperazinyl)ethylamine sarcosine; PTFE, poly(tetrafluoroethylene); DN, double network; [P2221O1][Inda], triethylmethoxymethyl phosphonium indazolide; [Veim][Gly], 1-vinyl-3-ethylimidazolium glycinate; PSf, poly(sulfone); [Im][TFSI], imidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl) imide; [Emim][DCA], 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium dicyanamide.

Conclusions

FTMs have shown incredible promise for efficient gas separations at low CO2 partial pressures, with both mobile and fixed carriers achieving permeabilities and selectivities beyond the Robeson upper bound. The future of FTMs for CO2 separations from air is likely to involve incorporation of both fixed and mobile carriers simultaneously. The key takeaways from the reviewed literature on FTMs with ILs are summarized below:

FTMs with liquid components like IL carriers generally give higher permeability and selectivity in contrast to their solid-based carrier FTM counterparts.

When designing IL carriers, CO2 binding enthalpy is a critical property to tune, as it impacts the likelihood of CO2 desorption to regenerate the carrier. For mobile carriers, viscosity is also important, as most current FTMs are originally designed to function at high temperature and humidity, making them non-ideal for CO2 separations from air.

For low CO2 partial pressure environments like cabin air, FTMs provide a promising technology platform, and perhaps the only type of membranes, to replace state-of-the-art zeolites for more efficient and continuous CO2 separations. However, FTMs still have a low CO2 flux at low partial pressures and struggle to process large volumes of gas. It will be important to study the amount of gas processable in practical timeframes, since this metric will highly depend on the CO2 diffusivity and hopping rate.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

BG would like to acknowledge NASA Early Career Faculty Award #80NSSC18K1505.

References

- Anthony J. L., Maginn E. J., Brennecke J. F. (2002). Solubilities and thermodynamic properties of gases in the ionic liquid 1-n-butyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate. J. Phys. Chem. B 106, 7315–7320. 10.1021/jp020631a [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne A. P., Ciais P., Miller J. B. (2018). Cautious optimism and incremental goals toward stabilizing atmospheric CO2. Earth's Future 6, 1632–1637. 10.1029/2018EF001012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bara J. E., Camper D. E., Gin D. L., Noble R. D. (2010). Room-temperature ionic liquids and composite materials: platform technologies for CO2 capture. Acc. Chem. Res. 43, 152–159. 10.1021/ar9001747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates E. D., Mayton R. D., Ntai I., Davis J. H. (2002). CO2 capture by a task-specific ionic liquid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 926–927. 10.1021/ja017593d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y., Wang Z., Yi C., Bai Y., Wang J., Wang S. (2007). Gas transport property of polyallylamine–poly(vinyl alcohol)/polysulfone composite membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 310, 184–196. 10.1016/j.memsci.2007.10.052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. Z., Li P., Chung T. S. (2012). PVDF/ionic liquid polymer blends with superior separation performance for removing CO2 from hydrogen and flue gas. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 37, 11796–11804. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2012.05.111 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Zhao L., Wang B., Dutta P., Winston Ho W. S. (2016). Amine-containing polymer/zeolite Y composite membranes for CO2/N2 separation. J. Memb. Sci. 497, 21–28. 10.1016/j.memsci.2015.09.036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. X., Ho W. S. W. (2016). High-molecular-weight polyvinylamine/piperazine glycinate membranes for CO2 capture from flue gas. J. Memb. Sci. 514, 376–384. 10.1016/j.memsci.2016.05.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K. K., Salim W., Han Y., Wu D., Ho W. S. W. (2020). Fabrication and scale-up of multi-leaf spiral-wound membrane modules for CO2 capture from flue gas. J Memb. Sci. 595:117504 10.1016/j.memsci.2019.117504 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chue K. T., Kim J. N., Yoo Y. J., Cho S. H., Yang R. T. (1995). Comparison of activated carbon and zeolite 13X for CO2 recovery from flue gas by pressure swing adsorption. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 34, 591–598. 10.1021/ie00041a020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T. S., Jiang L. Y., Li Y., Kulprathipanja S. (2007). Mixed matrix membranes (MMMs) comprising organic polymers with dispersed inorganic fillers for gas separation. Prog. Polym. Sci. 32, 483–507. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2007.01.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cmarik G. E., Knox J. C. (2018). Co-adsorption of carbon dioxide on zeolite 13X in the presence of preloaded water, in International Conference on Environmental Systems (Albuquerque, NM: NASA; ). [Google Scholar]

- Cowan M. G., Gin D. L., Noble R. D. (2016). Poly(ionic liquid)/ionic liquid ion-gels with high “Free” ionic liquid content: platform membrane materials for CO2/light gas separations. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 724–732. 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cussler E. L., Aris R., Bhown A. (1989). On the limits of facilitated diffusion. J. Memb. Sci. 43, 149–164. 10.1016/S0376-7388(00)85094-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L. Y., Hagg M. B. (2014). Carbon nanotube reinforced PVAm/PVA blend FSC nanocomposite membrane for CO2/CH4 separation. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control 26, 127–134. 10.1016/j.ijggc.2014.04.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doong S. J. (2012). Membranes, adsorbent materials and solvent-based materials for syngas and hydrogen separation, in Functional Materials for Sustainable Energy Applications, eds Kilner J. A., Skinner S. J., Irvine S. J. C., Edwards P. P. (Cambridge, UK: Woodhead Publishing; ), 179–216. 10.1533/9780857096371.2.179 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-Azzami L. A., Grulke E. A. (2009). Carbon dioxide separation from hydrogen and nitrogen facilitated transport in arginine salt–chitosan membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 328, 15–22. 10.1016/j.memsci.2008.08.038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gurkan B., Goodrich B. F., Mindrup E. M., Ficke L. E., Massel M., Seo S., et al. (2010). Molecular design of high capacity, low viscosity, chemically tunable ionic liquids for CO2 capture. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 1, 3494–3499. 10.1021/jz101533k [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gurkan B. E., de la Fuente J. C., Mindrup E. M., Ficke L. E., Goodrich B. F., Price E. A., et al. (2010). Equimolar CO2 absorption by anion-functionalized ionic liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 2116–2117. 10.1021/ja909305t [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y., Salim W., Chen K. K., Wu D., Ho W. S. W. (2019). Field trial of spiral-wound facilitated transport membrane module for CO2 capture from flue gas. J. Memb. Sci. 575, 242–251. 10.1016/j.memsci.2019.01.024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y., Wu D., Ho W. S. W. (2018). Nanotube-reinforced facilitated transport membrane for CO2/N2 separation with vacuum operation. J. Memb. Sci. 567, 261–271. 10.1016/j.memsci.2018.08.061 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanioka S., Maruyama T., Sotani T., Teramoto M., Matsuyama H., Nakashima K., et al. (2008). CO2 separation facilitated by task-specific ionic liquids using a supported liquid membrane. J. Memb. Sci. 314, 1–4. 10.1016/j.memsci.2008.01.029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jindaratsamee P., Ito A., Komuro S., Shimoyama Y. (2012). Separation of CO2 from the CO2/N2 mixed gas through ionic liquid membranes at the high feed concentration. J. Memb. Sci. 423–424, 27–32. 10.1016/j.memsci.2012.07.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kamio E., Tanaka M., Shirono Y., Keun Y., Moghadam F., Yoshioka T., et al. (2020). Hollow fiber-type facilitated transport membrane composed of a polymerized ionic liquid-based gel layer with amino acidate as the CO2 carrier. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59, 2083–2092. 10.1021/acs.iecr.9b05253 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara S., Kamio E., Ishigami T., Matsuyama H. (2012). Effect of water in ionic liquids on CO2 permeability in amino acid ionic liquid-based facilitated transport membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 415, 168–175. 10.1016/j.memsci.2012.04.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara S., Kamio E., Otani A., Matsuyama H. (2014a). Fundamental investigation of the factors controlling the CO2 permeability of facilitated transport membranes containing amine-functionalized task-specific ionic liquids. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 53, 2422–2431. 10.1021/ie403116t [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara S., Kamio E., Yoshizumi A., Matsuyama H. (2014b). Polymeric ion-gels containing an amino acid ionic liquid for facilitated CO2 transport media. Chem. Commun. 50, 2996–2999. 10.1039/C3CC48231F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox J. C., Watson D. W., Giesy T. J., Cmarik G. E., Miller L. A. (2017). Investigation of desiccants and CO2 sorbents for exploration systems 2016–2017, in International Conference on Environmental Systems (Charleston, SC: NASA; ). [Google Scholar]

- Li F. F., Bai Y. E., Zeng S. J., Liang X. D., Wang H., Huo F., et al. (2019). Protic ionic liquids with low viscosity for efficient and reversible capture of carbon dioxide. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control 90:102801 10.1016/j.ijggc.2019.102801 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. Q., Jiang Z. Y., Wu Y. Z., Zhang H. Y., Cheng Y. D., Guo R. L., et al. (2015). High-performance composite membranes incorporated with carboxylic acid nanogels for CO2 separation. J. Memb. Sci. 495, 72–80. 10.1016/j.memsci.2015.07.065 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liao J. Y., Wang Z., Gao C. Y., Li S. C., Qiao Z. H., Wang M., et al. (2014). Fabrication of high-performance facilitated transport membranes for CO2 separation. Chem. Sci. 5, 2843–2849. 10.1039/C3SC53334D [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H., Gong K., Ying W., Chen D., Zhang J., Yan Y., et al. (2019). CO2-Philic separation membrane: deep eutectic solvent filled graphene oxide nanoslits. Small 15:1904145. 10.1002/smll.201904145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J., Ying Y. P., Guo X. Y., Huang H. L., Liu D. H., Zhong C. L. (2016). Fabrication of mixed-matrix membrane containing metal organic framework composite with task specific ionic liquid for efficient CO2 separation. J. Mater. Chem. A 4, 7281–7288. 10.1039/C6TA02611G [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama H., Terada A., Nakagawara T., Kitamura Y., Teramoto M. (1999). Facilitated transport of CO2 through polyethylenimine/poly(vinyl alcohol) blend membrane. J. Memb. Sci. 163, 221–227. 10.1016/S0376-7388(99)00183-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDanel W. M., Cowan M. G., Chisholm N. O., Gin D. L., Noble R. D. (2015). Fixed-site-carrier facilitated transport of carbon dioxide through ionic-liquid-based epoxy-amine ion gel membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 492, 303–311. 10.1016/j.memsci.2015.05.034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mittenthal M. S., Flowers B. S., Bara J. E., Whitley J. W., Spear S. K., Roveda J. D., et al. (2017). Ionic polyimides: hybrid polymer architectures and composites with ionic liquids for advanced gas separation membranes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 56, 5055–5069. 10.1021/acs.iecr.7b00462 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moghadam F., Kamio E., Matsuyama H. (2017a). High CO2 separation performance of amino acid ionic liquid-based double network ion gel membranes in low CO2 concentration gas mixtures under humid conditions. J. Memb. Sci. 525, 290–297. 10.1016/j.memsci.2016.12.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moghadam F., Kamio E., Yoshioka T., Matsuyama H. (2017b). New approach for the fabrication of double-network ion-gel membranes with high CO2/N2 separation performance based on facilitated transport. J. Memb. Sci. 530, 166–175. 10.1016/j.memsci.2017.02.032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno H., Fukumoto K. (2007). Amino acid ionic liquids. Acc. Chem. Res. 40, 1122–1129. 10.1021/ar700053z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otani A., Zhang Y., Matsuki T., Kamio E., Matsuyama H., Maginn E. J. (2016). Molecular design of high CO2 reactivity and low viscosity ionic liquids for CO2 separative facilitated transport membranes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 55, 2821–2830. 10.1021/acs.iecr.6b00188 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad B., Mandal B. (2018). Preparation and characterization of CO2-selective facilitated transport membrane composed of chitosan and poly(allylamine) blend for CO2/N2 separation. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 66, 419–429. 10.1016/j.jiec.2018.06.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao Z., Wang Z., Yuan S., Wang J., Wang S. (2015). Preparation and characterization of small molecular amine modified PVAm membranes for CO2/H2 separation. J. Memb. Sci. 475, 290–302. 10.1016/j.memsci.2014.10.034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rea R., Angelis M. G., Baschetti M. G. (2019). Models for facilitated transport membranes: a review. Membranes 9:26. 10.3390/membranes9020026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezakazemi M., Amooghin A. E., Montazer-Rahmati M. M., Ismail A. F., Matsuura T. (2014). State-of-the-art membrane based CO2 separation using mixed matrix membranes (MMMs): an overview on current status and future directions. Prog. Polym. Sci. 39, 817–861. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2014.01.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robeson L. M. (1991). Correlation of separation factor versus permeability for polymeric membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 62, 165–185. 10.1016/0376-7388(91)80060-J [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robeson L. M. (2008). The upper bound revisited. J. Memb. Sci. 320, 390–400. 10.1016/j.memsci.2008.04.030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salim W., Vakharia V., Chen Y., Wu D., Han Y., Ho W. S. W. (2018). Fabrication and field testing of spiral-wound membrane modules for CO2 capture from flue gas. J. Memb. Sci. 556, 126–137. 10.1016/j.memsci.2018.04.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scovazzo P. (2009). Determination of the upper limits, benchmarks, and critical properties for gas separations using stabilized room temperature ionic liquid membranes (SILMs) for the purpose of guiding future research. J. Memb. Sci. 343, 199–211. 10.1016/j.memsci.2009.07.028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seoane B., Coronas J., Gascon I., Etxeberria Benavides M., Karvan O., Caro J., et al. (2015). Metal-organic framework based mixed matrix membranes: a solution for highly efficient CO2 capture? Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 2421–2454. 10.1039/C4CS00437J [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J., Liu G. P., Huang K., Li Q. Q., Guan K. C., Li Y. K., et al. (2016). UiO-66-polyether block amide mixed matrix membranes for CO2 separation. J. Memb. Sci. 513, 155–165. 10.1016/j.memsci.2016.04.045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shindo R., Kishida M., Sawa H., Kidesaki T., Sato S., Kanehashi S., et al. (2014). Characterization and gas permeation properties of polyimide/ZSM-5 zeolite composite membranes containing ionic liquid. J. Memb. Sci. 454, 330–338. 10.1016/j.memsci.2013.12.031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siriwardane R. V., Shen M. S., Fisher E. P. (2005). Adsorption of CO2 on zeolites at moderate temperatures. Energy Fuels 19, 1153–1159. 10.1021/ef040059h [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Szala-Bilnik J., Abedini A., Crabtree E., Bara J. E., Turner C. H. (2019). Molecular transport behavior of CO2 in ionic polyimides and ionic liquid composite membrane materials. J. Phys. Chem. B 123, 7455–7463. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.9b05555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szala-Bilnik J., Crabtree E., Abedini A., Bara J. E., Turner C. H. (2020). Solubility and diffusivity of CO2 in ionic polyimides with [C(CN)(3)](x)[oAc](1-x) anion composition. Comput. Mater. Sci. 174:109468 10.1016/j.commatsci.2019.109468 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teodoro R. M., Tomé L. C., Mantione D., Mecerreyes D., Marrucho I. M. (2018). Mixing poly(ionic liquid)s and ionic liquids with different cyano anions: membrane forming ability and CO2/N2 separation properties. J. Memb. Sci. 552, 341–348. 10.1016/j.memsci.2018.02.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teramoto M., Nakai K., Ohnishi N., Huang Q., Watari T., Matsuyama H. (1996). Facilitated transport of carbon dioxide through supported liquid membranes of aqueous amine solutions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 35, 538–545. 10.1021/ie950112c [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomé L. C., Florindo C., Freire C. S. R., Rebelo L. P. N., Marrucho I. M. (2014). Playing with ionic liquid mixtures to design engineered CO2 separation membranes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 17172–17182. 10.1039/C4CP01434K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomé L. C., Guerreiro D. C., Teodoro R. M., Alves V. D., Marrucho I. M. (2018). Effect of polymer molecular weight on the physical properties and CO2/N2 separation of pyrrolidinium-based poly(ionic liquid) membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 549, 267–274. 10.1016/j.memsci.2017.12.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tome L. C., Marrucho I. M. (2016). Ionic liquid-based materials: a platform to design engineered CO2 separation membranes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 2785–2824. 10.1039/C5CS00510H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Z., Ho W. S. W. (2016). Facilitated transport membranes for CO2 separation and capture. Sep. Sci. Technol. 52, 156–167. 10.1080/01496395.2016.1217885 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Z., Ho W. S. W. (2017). New sterically hindered polyvinylamine membranes for CO2 separation and capture. J. Memb. Sci. 543, 202–211. 10.1016/j.memsci.2017.08.057 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. H., Guo F. Y., Li H., Xu J., Hu J., Liu H. L., et al. (2020). A porous ionic polymer bionic carrier in a mixed matrix membrane for facilitating selective CO2 permeability. J. Memb. Sci. 598:117677 10.1016/j.memsci.2019.117677 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S. F., Wu Y. Z., Zhang N., He G. W., Xin Q. P., Wu X. Y., et al. (2016). A highly permeable graphene oxide membrane with fast and selective transport nanochannels for efficient carbon capture. Energy Environ. Sci. 9, 3107–3112. 10.1039/C6EE01984F [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J. H., Lv B. H., Wu X. M., Zhou Z. M., Jing G. H. (2019). Aprotic heterocyclic anion-based dual-functionalized ionic liquid solutions for efficient CO2 uptake: quantum chemistry calculation and experimental research. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 7, 7312–7323. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b00420 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xin Q., Wu H., Jiang Z., Li Y., Wang S., Li Q., et al. (2014). SPEEK/amine-functionalized TiO2 submicrospheres mixed matrix membranes for CO2 separation. J. Memb. Sci. 467, 23–35. 10.1016/j.memsci.2014.04.048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xin Q. P., Zhang Y., Shi Y., Ye H., Lin L. G., Ding X. L., et al. (2016). Tuning the performance of CO2 separation membranes by incorporating multifunctional modified silica microspheres into polymer matrix. J. Memb. Sci. 514, 73–85. 10.1016/j.memsci.2016.04.046 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xing R., Ho W. S. W. (2011). Crosslinked polyvinylalcohol–polysiloxane/fumed silica mixed matrix membranes containing amines for CO2/H2 separation. J. Memb. Sci. 367, 91–102. 10.1016/j.memsci.2010.10.039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yegani R., Hirozawa H., Teramoto A., Himei H., Okada O., Takigawa T., et al. (2007). Selective separation of CO2 by using novel facilitated transport membrane at elevated temperatures and pressures. J. Memb. Sci. 291, 157–164. 10.1016/j.memsci.2007.01.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y., Wang J., Wang Y., Pan W., Liu C., Liu P., et al. (2020). Polyethyleneimine-functionalized phenolphthalein-based cardo poly(ether ether ketone) membrane for CO2 separation. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 83, 20–28. 10.1016/j.jiec.2019.10.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J., Wang Z., Wang J., Wang S. (2012). High-performance membranes comprising polyaniline nanoparticles incorporated into polyvinylamine matrix for CO2/N2 separation. J. Memb. Sci. 403–404, 203–215. 10.1016/j.memsci.2012.02.048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S., Cao X., Ma Z., Wang Z., Qiao Z., Wang J., et al. (2015). Mixed-matrix membranes for CO2/N2 separation comprising a poly(vinylamine) matrix and metal–organic frameworks. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 54, 5139–5148. 10.1021/ie504786x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S., Wang Z., Qiao Z., Wei X., Zhang C., Wang J., et al. (2013). Gas separation membrane with CO2-facilitated transport highway constructed from amino carrier containing nanorods and macromolecules. J. Mater. Chem. A 1, 246–249. 10.1039/C2TA00247G [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Ho W. S. W. (2012a). CO2-Selective membranes containing sterically hindered amines for CO2/H2 separation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 52, 8774–8782. 10.1021/ie301397m [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Ho W. S. W. (2012b). Steric hindrance effect on amine demonstrated in solid polymer membranes for CO2 transport. J. Memb. Sci. 415–416, 132–138. 10.1016/j.memsci.2012.04.044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Jung B. T., Ansaloni L., Ho W. S. W. (2014). Multiwalled carbon nanotube mixed matrix membranes containing amines for high pressure CO2/H2 separation. J. Memb. Sci. 459, 233–243. 10.1016/j.memsci.2014.02.022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zolandz R. R., Fleming G. K. (1992). Theory, in Membrane Handbook, eds Ho W. S. W., Sirkar K. K. (Boston, MA: Springer US; ), 954 10.1007/978-1-4615-3548-5_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zou J., Ho W. S. W. (2006). CO2-selective polymeric membranes containing amines in crosslinked poly(vinyl alcohol). J. Memb. Sci. 286, 310–321. 10.1016/j.memsci.2006.10.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]