Abstract

Background: Little research to date has investigated the spectrum of bladder health in women, including both bladder function and well-being. Therefore, we expanded our previous baseline analysis of bladder health in the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey to incorporate several additional measures of bladder-related well-being collected at the 5-year follow-up interview, including one developed specifically for women.

Methods: At follow-up, participants reported their frequency of 15 lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), degree of life impact from and thought related to urinary symptoms or pelvic/bladder pain/discomfort, and perception of their bladder condition. Prevalence ratios were calculated by generalized linear models with robust variance estimation, adjusting for LUTS risk factors and individual LUTS. The BACH Survey was approved by the New England Research Institutes Institutional Review Board and all participants provided written informed consent.

Results: Generally similar findings were observed in the 5-year cross-sectional analysis as at baseline, irrespective of how we categorized LUTS or measured bladder-related well-being. Approximately one in five women (16.2%–18.0% of 2527 eligible women) reported no LUTS and no diminished bladder-related well-being, the majority (55.8%–65.7%) reported some LUTS and/or diminished well-being, and a further one in five (16.9%–26.6%) reported the maximum frequency, number, or degree of LUTS and/or diminished well-being. Measures of storage function (urinating again after <2 hours, perceived frequency, nocturia, incontinence, and urgency) and pain were independently associated with bladder-related well-being.

Conclusions: Our similar distribution of bladder health and consistent associations between LUTS and bladder-related well-being across multiple measures of well-being, including a female-specific measure, lend confidence to the concept of a bladder health spectrum and reinforce the bothersome nature of storage dysfunction and pain.

Keywords: bladder, health, women

Introduction

As the medical and public health research communities have increasingly adopted a more holistic view of health,1 a growing number of fields have developed or revised their definitions of organ-specific health to include not only the absence of disease or infirmity but also the presence of well-being and/or absence of disease risk factors.2,3 Consistent with this trend, the Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (PLUS) Research Consortium developed the following working research definition of bladder health: “A complete state of physical, mental, and social well-being related to bladder function and not merely the absence of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). Healthy bladder function permits daily activities, adapts to short-term physical or environmental stressors, and allows optimal well-being (e.g., travel, exercise, social, occupational, or other activities).”4 The Consortium also applied this working research definition to the three main bladder functions (“storage,” “emptying,” and “bioregulatory”) and described unhealthy characteristics of each function.5

To begin to inform and quantify the spectrum of this new concept, we recently performed a secondary analysis of existing data from the baseline interview of the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey, taking advantage of its extensive collection of information on LUTS and its rare, universal collection of information on interference with activities from urinary experiences in adult women. Although these two sets of measures—LUTS and interference from urinary experiences—do not capture all constructs described in our working bladder health definition, we used these two measures to begin to approximate the spectrum of bladder health. In our previous analysis, we found that approximately one in five women might be considered to have optimal bladder health (no LUTS and no interference), three in five to have good to intermediate health (intermediate frequencies of LUTS or interference), and the remaining one in five to have worse or poor bladder health (constant LUTS or interference), supporting a spectrum of bladder health in women.6 We also found that measures of storage function, such as urinary urgency and frequency, were independently associated with prevalent interference. However, each of these findings was limited by its reliance on a measure of well-being or bother (i.e., interference) developed for men with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) rather than for women. Therefore, to determine the sensitivity of our findings to this male- or BPH-specific measure, we repeated the analyses (both for the cross-sectional distribution of bladder health and associations between prevalent LUTS and bladder-related well-being) using data from a female-specific measure of well-being collected at the BACH follow-up interview. As secondary objectives, we also repeated the analyses using several additional single-item measures of well-being collected at the follow-up interview to determine whether similar findings could be generated with more brief measures.

Methods

Study population and design

The BACH survey is a population-based, longitudinal study of community-dwelling residents from Boston (n = 5506). Participants were recruited from 2002 to 2005 using a two-stage cluster design, with stratification by sex (male and female), race/ethnicity (equally distributed across black, Hispanic, and white), and age (30–39, 40–49, 50–59, and 60–79 years; 63.4% completion rate). At baseline, consented participants completed an in-home interview and self-administered questionnaire (>2 hours), provided an early-morning blood sample, and had their height, weight, blood pressure, hip and waist circumference, pulse rate, and blood pressure measured.7 Participants were recontacted ∼5 years later for a follow-up visit in 2008–2010.

For this analysis, we limited the analytic sample to female participants who completed the follow-up interview, as well as at least one LUTS item, one item on the female-specific well-being measure, and each single-item well-being measure collected at follow-up. For association analyses, women were additionally required to provide complete information on all covariates.

The BACH Survey was approved by the New England Research Institutes Institutional Review Board and all participants provided written informed consent.

LUTS assessment

At the follow-up interview, participants completed questions about their frequency of several measures of storage, emptying, and bioregulatory function.5 These included LUTS such as urgency, nocturia, and pain with bladder filling to capture unhealthy storage; LUTS such as hesitancy, incomplete emptying, and pain with urination to capture unhealthy emptying; and urinary tract infections to capture unhealthy bioregulatory function. As most of these measures are symptoms, we refer to them hereafter as “LUTS” for simplicity. LUTS were assessed by several validated questionnaires, including the American Urological Association Symptom Index (AUASI),8 Sandvik Incontinence Severity Scale,9 and Interstitial Cystitis Symptom Index,10 as well as by items written specifically for BACH.

We collapsed the 26 LUTS items assessed into 15 combined LUTS, as several used either similar wording or captured similar LUTS.6 For each combined LUTS, we used a criterion of ≤20% disagreement across responses to combine items (Appendix Table A1) and the maximum response from any of the contributing items to capture LUTS frequency. Missing values for individual LUTS items were assigned a value of “none” (n = 707 participants had 1 missing item and 74 had 2–4 missing items). For analyses describing the spectrum of bladder health, we used the full range of LUTS frequency categories, whereas for analyses investigating LUTS associated with well-being, we defined LUTS as a frequency of “rarely” or more (vs. “none”) to allow us to explore the lower end of the LUTS frequency distribution closest to what might represent optimal bladder health.

Well-being assessment

At the follow-up interview, bladder-related well-being or bother was assessed in all women irrespective of LUTS by five measures: the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ),11 three separate well-being related items, and the interference with activities domain of the Epstein Quality of Life Questionnaire for BPH.12 The first four scales/items were assessed in all participants for the first time at follow-up, whereas the Epstein scale was also administered at baseline and incorporated into our previous baseline analysis.6

The first scale, the IIQ, was developed and validated specifically for women with incontinence.11 It queries the degree to which experiences with “urine leakage” affect seven daily activities or aspects of life, including the ability to do household chores, such as cooking, housecleaning, laundry, or yard work; physical recreational activities, such as walking, swimming, or other exercise; entertainment activities, such as going to a film or concert; the ability to travel by car or bus for distances greater than 30 minutes away from home; participation in social activities outside the home; and emotional health. It also queries the degree to which urine leakage causes participants to experience frustration. This scale was modified for the BACH follow-up interview to expand “urine leakage” to “urinary symptoms and pain or discomfort in [their] pelvic or bladder area.”

The three single-item measures of bladder-related well-being were as follows: (1) “How much did you think about your urinary symptoms and/or pelvic pain during the last month?” (modified from the National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index13); (2) “If you were to spend the rest of your life with your urinary and/or pelvic pain condition the way it has been over the last month, how would you feel about that?” (modified from the AUASI8); and (3) “Which of the following statements best describes your bladder condition best at the moment?” (a validated item on patients' perception of their bladder condition developed for individuals with overactive bladder14).

Finally, the Epstein scale, a scale developed and validated for men with BPH,12 queries the frequency of interference from urinary “problems” in the past month with five daytime activities (drinking fluids before travel, driving for 2 hours without stopping, going to places that may not have a toilet, playing sports outdoors such as golf, and going to movies, shows, and church), and two nighttime activities (drinking fluids before bed and getting enough sleep at night). The Epstein scale was modified for BACH to refer to urinary “problems” as “symptoms” and to include interference due to pain or discomfort in the pelvic or bladder area.

For the IIQ and Epstein scale, missing values were assigned a value of “none” (n = 3 participants for the IIQ and 6 for the Epstein scale). Analyses describing the distribution of bladder health used the full range of well-being categories, whereas those investigating LUTS associated with well-being dichotomized these variables as “none” or “never” versus any degree or frequency of impact/problems/interference to allow us to explore the lower end of the distribution farthest away from symptomatic urologic disease and closest to what might represent optimal bladder health.

Statistical analysis

To account for the BACH sampling design, we weighted all observations inversely proportional to their probability of selection, with further poststratification to the Boston population using the 2000 US Census.7

Cross-sectional distribution of bladder health at follow-up

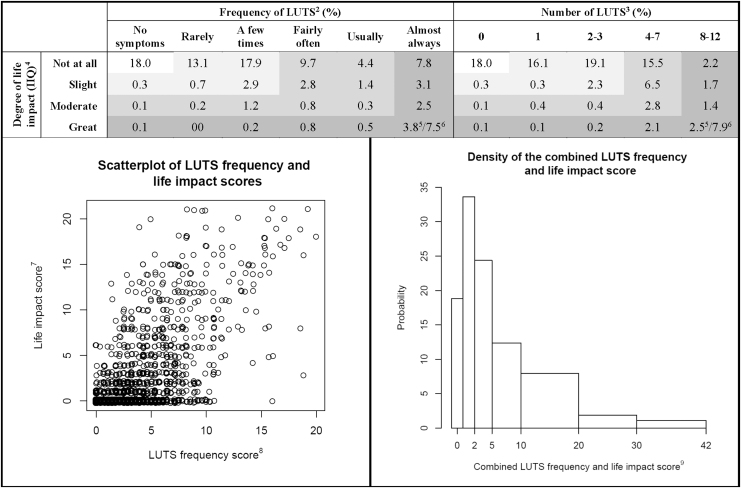

Similar to our previous analysis of bladder health at baseline,6 we used several approaches to explore and quantify the cross-sectional distribution of bladder health at follow-up. The first were cross-tabulations of the maximum frequency of LUTS (out of 12 LUTS, using any incontinence in the past year rather than individual types of incontinence in the past week) or number of LUTS and the maximum degree of life impact, using data from the IIQ. In these cross-tabulations, we included women with self-reported past or current bladder conditions (i.e., use of current LUTS medications, previous incontinence or bladder surgery, chronic indwelling catheterization, and bladder cancer) in the highest LUTS/impact category to acknowledge their poorer bladder health and to avoid misclassifying them as having better bladder health because of the influence of treatment on their current self-reported LUTS and life impact.

Additional approaches used to describe the distribution of bladder health were as follows: (1) a scatter plot of IIQ life impact and LUTS frequency scores and (2) a histogram of a combined life impact and LUTS frequency score. The life impact score was calculated by summing the degree of impact (0–3) with each of the five activities and two emotional health items (range: 0–21).11 The LUTS frequency score was calculated by summing the frequency (0–5, except for any incontinence: 0–4) of the above-described 12 LUTS (range: 0–59) and then by standardizing to a range of 21. Finally, we calculated a combined life impact and LUTS frequency score by summing the individual life impact and LUTS scores (range: 0–42).

In secondary analyses, we performed cross-tabulations of the maximum frequency and number of LUTS with the single-item measures of well-being.

Prevalent associations between LUTS and well-being

To determine whether previously observed associations between prevalent LUTS and decreased well-being using the Epstein interference scale at baseline6 could also be observed using the female-specific IIQ scale, we examined the relationship between prevalent LUTS and well-being at follow-up. Potential confounding was investigated by comparing proportions of demographic, lifestyle, and clinical variables by LUTS and well-being status at follow-up. Associations were investigated by calculating crude and multivariable-adjusted prevalence ratios, using log-link generalized linear models with robust variance estimation. Our first set of multivariable-adjusted models included terms for follow-up age; race/ethnicity; menopausal status; parity; smoking status; alcohol intake; health-related limitations in activities; self-reported physician diagnoses of high blood pressure, types I or II diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and arthritis; depressive symptoms15; and measured body mass index and waist circumference. Our second set included the aforementioned variables, as well as all individual LUTS, to identify those independently associated with diminished well-being.

Secondary analyses repeated the analyses using the single-item measures of well-being.

Sensitivity analyses

To ensure that any observed difference between our previous baseline findings6 and those from this analysis was specific to the new scales/items rather than to changes in the BACH population over time, we repeated all of the analyses using the 5-year follow-up Epstein interference scale data (as opposed to the baseline data). Additional sensitivity analyses for the cross-sectional bladder health distribution analysis were as follows: (1) exclusion of women with known past or current bladder conditions (i.e., current LUTS medications, previous incontinence or bladder surgery, chronic indwelling catheterization, and bladder cancer), as their exact position on the LUTS/well-being distribution could not be determined based on their untreated LUTS/well-being; and (2) exclusion of women with non-bladder conditions that might contribute to LUTS or diminished well-being due to urinary symptoms or pelvic/bladder pain or discomfort (i.e., genitourinary cancers besides bladder cancer, prolapse of the uterus, “bladder, or rectum,” congenital urinary tract abnormalities [a large proportion of which are renal16,17], endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, chronic pelvic pain, vulvodynia, and diabetes). These women were excluded because their LUTS and diminished well-being might not reflect poor bladder health, but instead poor health in other organs besides the bladder. For analyses investigating LUTS associated with well-being, sensitivity analyses were as follows: (1) exclusion of women with histories of bladder and non-bladder-related conditions potentially associated with LUTS and/or well-being and (2) use of higher cutoff points for LUTS (at least “a few times”) and well-being (at least “moderate”) to determine whether associations observed at lower ends of the LUTS and well-being spectrums were also observed at higher ends. Analyses were performed using R v3.5.18–20

Results

Distribution of bladder health at follow-up

Of the 3205 female participants interviewed at baseline, 2534 were interviewed ∼5 years later at the follow-up interview, and 2527 provided information on at least one LUTS, one IIQ item, and each single-item well-being measure. These 2527 women were similar to those in our previous baseline bladder health distribution analyses,6 with the majority being perimenopausal or postmenopausal, parous, overweight, or obese, and not limited in activities by their health (Table 1). Eighty-one percent of women reported LUTS at least rarely and 23.9% reported at least slight bladder-related, diminished well-being. When compared by LUTS and well-being status, women with LUTS or diminished well-being tended to be older, have undergone surgical menopause, be former smokers, and have limitations in their activities and self-reported comorbidities, including high blood pressure, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, arthritis, and depressive symptoms. Women with LUTS also tended to be non-Hispanic white, and women with diminished well-being were less likely to consume alcohol and more likely to be obese and have a large waist circumference.

Table 1.

Demographic, Lifestyle, and Clinical Characteristics of Women by Frequency of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms and Degree of Life Impact from Urinary Symptoms, Pain or Discomfort in the Pelvic or Bladder Area; Boston Area Community Health Survey, 2008–2010

| All participants (N = 2527) | Frequency of LUTSa |

Degree of life impactb |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (N = 528) | Ever (N = 1999) | p | None (N = 1841) | Any (N = 686) | p | ||

| Age, years, % | |||||||

| 26–44 | 32.5 | 42.9 | 30.0 | 34.0 | 27.7 | ||

| 45–64 | 42.1 | 42.4 | 42.1 | <0.001 | 41.3 | 44.6 | 0.217 |

| ≥65 | 25.4 | 14.7 | 28.0 | 24.7 | 27.7 | ||

| Race, % | |||||||

| Black | 28.8 | 34.6 | 27.5 | 29.1 | 27.9 | ||

| Hispanic | 12.2 | 14.2 | 11.8 | 0.032 | 11.3 | 15.1 | 0.230 |

| White | 58.9 | 51.2 | 60.8 | 59.5 | 57.0 | ||

| Menopausal status, % | |||||||

| Premenopausal/Undetermined | 28.2 | 35.7 | 26.4 | 30.2 | 21.7 | ||

| Perimenopausal | 17.5 | 19.6 | 17.0 | 0.004 | 18.0 | 15.7 | 0.003 |

| Postmenopausal | 32.2 | 31.6 | 32.3 | 32.1 | 32.4 | ||

| Surgical | 22.2 | 13.1 | 24.3 | 19.6 | 30.2 | ||

| Parity, %c | |||||||

| 0 pregnancies | 19.3 | 21.8 | 18.6 | 20.6 | 15.1 | ||

| 1–3 pregnancies | 46.3 | 48.8 | 45.7 | 0.260 | 46.3 | 46.4 | 0.126 |

| ≥4 pregnancies | 34.3 | 29.0 | 35.6 | 33.0 | 38.6 | ||

| Cigarette smoking status, % | |||||||

| Never smoker | 47.4 | 54.2 | 45.8 | 50.3 | 38.3 | ||

| Former smoker | 31.6 | 23.4 | 33.5 | 0.064 | 29.9 | 36.9 | 0.008 |

| Current smoker | 18.5 | 19.5 | 18.3 | 17.4 | 22.0 | ||

| Alcohol use, average drinks/day, %c | |||||||

| <1 drink | 39.6 | 42.7 | 38.8 | 37.3 | 46.6 | ||

| 1–2 drinks | 45.2 | 40.8 | 46.3 | 0.450 | 47.8 | 36.9 | 0.019 |

| ≥3 drinks | 11.2 | 12.3 | 10.9 | 11.3 | 10.9 | ||

| Body mass index, kg/m2, %c | |||||||

| <25 | 27.5 | 29.5 | 27.0 | 31.2 | 15.6 | ||

| 25–29 | 30.7 | 33.6 | 30.0 | 0.559 | 31.1 | 29.2 | <0.001 |

| ≥30 | 41.1 | 35.6 | 42.4 | 36.9 | 54.3 | ||

| Waist circumference, cm, %c | |||||||

| <65 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 1.1 | ||

| 65–89 | 51.8 | 54.1 | 51.3 | 0.427 | 55.2 | 41.1 | <0.001 |

| 90–114 | 36.3 | 37.6 | 36.0 | 34.9 | 41.0 | ||

| ≥115 | 9.2 | 6.6 | 9.8 | 7.0 | 16.0 | ||

| Health-related limitations in activities, %d | |||||||

| Not limited at all | 52.2 | 72.3 | 47.4 | 59.9 | 27.9 | ||

| Limited a little | 28.9 | 19.6 | 31.1 | <0.001 | 26.7 | 35.7 | <0.001 |

| Limited a lot | 18.9 | 8.1 | 21.5 | 13.3 | 36.5 | ||

| Self-reported physician diagnosis of, % | |||||||

| High blood pressure | 37.1 | 25.8 | 39.7 | <0.001 | 34.5 | 45.3 | 0.002 |

| Type I diabetes | 4.1 | 3.1 | 4.3 | 0.333 | 2.5 | 8.9 | <0.001 |

| Type II diabetes | 10.8 | 6.7 | 11.8 | 0.001 | 8.9 | 17.0 | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular diseasee | 27.1 | 19.8 | 28.8 | 0.006 | 24.9 | 34.1 | 0.004 |

| Arthritis or rheumatism | 41.5 | 24.8 | 45.5 | <0.001 | 37.6 | 54.1 | <0.001 |

| Depressive symptoms, %f | 17.0 | 7.4 | 19.3 | <0.001 | 12.4 | 31.8 | <0.001 |

All values were weighted according to the sampling weights of the Boston Area Community Health Survey.

Includes 15 LUTS in the past month (urinating again after <2 hours; perceived frequency; nocturia; stress incontinence [in the past week]; urgency incontinence [in the past week]; nonstress, nonurgency incontinence [in the past week]; any incontinence [in the past year]; dribbling/wet clothes after urination; urgency/difficulty postponing urination; pain, burning, discomfort in the pubic/bladder area; straining/difficult to begin voiding; weak stream; intermittency; incomplete emptying; and urinary tract infection [in the past year]). “None” was defined as no LUTS in the past month and “ever” was defined as any LUTS experienced at least rarely in the past month.

Assessed by a modified version of the IIQ. “None” was defined as no impact with any of the seven activities/aspects of life assessed and “any” was defined as at least slight impact with any activity/aspect of life.

Numbers may not sum to 100% because of missing values.

Examples for participants included moving a table, pushing a vacuum cleaner, softball, or playing golf.

Includes coronary artery bypass, myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, congestive heart failure, transient ischemic attack, stroke, carotid artery surgery, intermittent claudication, pulmonary embolus, aortic aneurysm, heart rhythm disturbance, Raynaud's disease, and peripheral vascular disease.

Defined as an affirmative response to at least five of eight items on a revised version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies of Depression Scale.15

IIQ, Incontinence Impact Questionnaire; LUTS, lower urinary tract symptom.

With respect to LUTS, a similar distribution was observed at the follow-up interview as at baseline: 19.3% of women reported never experiencing LUTS, 61.4% rarely to usually, and 19.2% almost always, for a total of 80.6% with any frequency of LUTS in the past month (Table 2). With respect to well-being, the degree of impact reported on the IIQ was slightly less than that the frequency of interference reported on the Epstein scale at baseline (and follow-up): 76.2% reported no impact at all, 18.4% slight to moderate impact, and 5.5% great impact, for a total of 23.9% with any degree of impact (Table 3). This distribution was generally similar across each of the different life impact domains. When other single-item measures of well-being were examined, 32.2% reported thinking about their urinary symptoms or pelvic pain at least “a little” of the time, 65.3% felt “pleased” or less than pleased about their current urinary and/or pelvic pain condition (47.4% using a threshold of “mostly satisfied”), and 40.8% reported at least “very minor” problems with their bladder condition (22.0% using a threshold of “minor” problems). Overall, high agreement was observed between measures of well-being (% agreement = 63.1%–76.8%).

Table 2.

Frequency of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in the Past Month in a Community-Based Sample of 2527 Women; Boston Area Community Health Survey, 2008–2010

| Frequency in the past month, %a |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Rarely | A few times | Fairly often | Usually | Almost always | Ever | |

| Urinating again after <2 hours | 43.1 | 13.9 | 19.2 | 12.8 | 4.2 | 6.7 | 56.8 |

| Perceived frequency | 62.6 | 6.9 | 10.5 | 9.1 | 4.0 | 6.9 | 37.4 |

| Nocturia | 58.0 | 11.2 | 10.8 | 5.1 | 3.7 | 11.2 | 42.0 |

| Stress incontinenceb | 89.4 | 2.7 | 3.9 | 2.8 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 10.7 |

| Urgency incontinenceb | 91.3 | 3.3 | 2.9 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 8.7 |

| Nonstress, nonurgency incontinenceb | 93.4 | 1.6 | 2.9 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 6.5 |

| Dribbling/wet clothes after urination | 82.2 | 7.9 | 5.1 | 2.5 | 0.5 | 1.7 | 17.7 |

| Urgency/difficulty postponing urination | 63.3 | 11.9 | 10.4 | 6.6 | 2.4 | 5.4 | 36.7 |

| Pain, burning, discomfort in the pubic/bladder area | 88.1 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 11.8 |

| Straining/difficult to begin voiding | 90.8 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 1.2 | 9.2 |

| Weak stream | 86.9 | 5.7 | 4.1 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 13.1 |

| Intermittency | 83.8 | 6.3 | 4.2 | 2.6 | 2.1 | 1.0 | 16.2 |

| Incomplete emptying | 70.2 | 10.1 | 13.4 | 3.6 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 29.7 |

| Any incontinencec | Degree in the past year |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Very severe | Any | |

| 66.1 | 18.4 | 11.7 | 2.2 | 1.5 | 33.8 | |

| Number in the past year |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2–3 | 4–5 | 6–7 | ≥8 | Any | |

| Urinary tract infectiond |

89.5 |

7.2 |

2.7 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

10.5 |

| Any LUTS | 19.3 | 14.7 | 23.9 | 15.0 | 7.8 | 19.2 | 80.6 |

All values were weighted according to the sampling weights of the Boston Area Community Health Survey.

Assessed in the past week and categorized into the following frequencies: 0, 1, 2–3, 4–5, 6–7, and ≥8 times.

Assessed in the past year and categorized into the following groups: none, mild, moderate, severe, and very severe, according to methods described previously.22

Assessed in the past year and categorized into the following frequencies: 0, 1, 2–3, 4–5, 6–7, and ≥8 times.

Table 3.

Degree of Life Impact from Urinary Symptoms, Pain or Discomfort in the Pelvic or Bladder Area in a Community-Based Sample of 2527 Women; Boston Area Community Health Survey, 2008–2010

| Activity/aspect of life | Degree of life impact (IIQ), %a |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not at all | Slight | Moderate | Great | Any | |

| Ability to do household chores | 91.5 | 5.1 | 2.7 | 0.7 | 8.5 |

| Physical recreational activities | 88.6 | 6.8 | 2.7 | 1.9 | 11.4 |

| Entertainment activities | 89.8 | 5.5 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 10.1 |

| Ability to travel by car or bus for >30 minutes | 86.2 | 7.3 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 13.7 |

| Participation in social activities outside of home | 89.6 | 4.7 | 4.0 | 1.7 | 10.4 |

| Emotional health | 89.4 | 6.0 | 2.9 | 1.6 | 10.5 |

| Experience frustration | 84.7 | 8.8 | 3.5 | 2.9 | 15.2 |

| Any impact | 76.2 | 12.3 | 6.1 | 5.5 | 23.9 |

| |

Degree of thought, %a |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Only a little | Some | A lot | Any | |

| 67.9 | 19.4 | 8.0 | 4.8 | 32.2 | |

| |

Degree of life impact (AUASI), %a |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delighted | Pleased | Mostly satisfied | Mixed | Mostly dissatisfied | Un-happy | Terrible | Any | |

| 34.7 | 17.9 | 20.8 | 13.9 | 7.4 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 65.3 | |

| |

Patients’ perception of bladder condition (% with a problem)a |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Very minor | Minor | Moderate | Severe | Many severe | Any | |

| 59.2 | 18.8 | 12.1 | 7.0 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 40.8 | |

| Activity | Frequency of interference in the past month (Epstein scale), %a |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | A little | Some | Most | All | Any | |

| Drinking fluids before travel |

78.2 |

8.8 |

4.5 |

3.7 |

4.8 |

21.8 |

| Driving for 2 hours without stopping |

82.6 |

6.4 |

3.8 |

3.5 |

3.7 |

17.4 |

| Going to places that may not have a toilet |

76.2 |

8.2 |

6.1 |

3.6 |

5.8 |

23.7 |

| Playing sports outdoors such as golf |

93.4 |

2.3 |

1.5 |

0.7 |

2.0 |

6.5 |

| Going to movies, shows, church, etc. |

90.0 |

3.5 |

2.9 |

1.7 |

1.9 |

10.0 |

| Drinking fluids before bed |

74.5 |

10.1 |

6.8 |

3.3 |

5.3 |

25.5 |

| Getting enough sleep at night |

76.1 |

9.5 |

5.9 |

4.1 |

4.4 |

23.9 |

| Interference with any activity | 57.5 | 14.3 | 10.1 | 7.4 | 10.7 | 42.5 |

All values were weighted according to the sampling weights of the Boston Area Community Health Survey.

AUASI, American Urological Association Symptom Index.

When we cross-classified LUTS and bladder-related well-being as assessed by the IIQ, the joint distribution of these two measures was similar to that observed at baseline (and follow-up) using the Epstein interference scale: 18.0% reported no LUTS and no impact, 34.9% reported LUTS rarely or a few times and/or slight impact, 20.9% reported LUTS fairly often or usually and/or moderate impact, and 26.3% reported LUTS almost always and/or great impact, with 3.8% reporting both (Fig. 1 and Appendix Table A3). Eight percent (7.5%) of women were classified in the highest category because of their current or past bladder conditions. Interestingly, the largest subgroup within each of these groups was always the group with LUTS, but without impact (combined prevalence = 52.9%), similar to our observation at baseline. Generally similar distributions were also observed when the number of LUTS was examined rather than the maximum frequency of LUTS (18.0% no LUTS or impact, 63.8% some LUTS or impact, and 18.2% ≥ 8 LUTS or the worst degree of impact). Results shifted slightly more toward lower LUTS frequencies and impact when women with bladder conditions and those who might contribute to bladder symptoms were excluded and when younger women were examined (data not shown and Appendix Table A2). Finally, when we investigated LUTS and life impact as continuous scores, a greater density of values was observed at the lower ends of the LUTS and life impact distributions, and a right-skewed distribution was observed when the LUTS and life impact scores were summed.

FIG. 1.

Joint distribution1 of LUTS in the past month and degree of impact from urinary symptoms, pain or discomfort in the pelvic or bladder area in a community-based sample of 2527 women; Boston Area Community Health Survey, 2008–2010. 1All values were weighted according to the sampling weights of the Boston Area Community Health Survey. 2Maximum frequency of LUTS across 12 LUTS (urinating again after <2 hours; perceived frequency; nocturia; any incontinence [in the past year]; dribbling/wet clothes after urination; urgency/difficulty postponing urination; pain, burning, discomfort in the pubic/bladder area; straining/difficult to begin voiding; weak stream; intermittency; incomplete emptying; and urinary tract infection [in the past year]). 3Number of LUTS experienced at least rarely in the past month (out of the 12 LUTS described above). 4Maximum degree of impact across seven activities or aspects of life. 5Represents the percentage of women who reported the highest category of LUTS and impact. 6Represents the percentage of women with self-reported current or past bladder conditions (i.e., use of current LUTS medications, previous incontinence or bladder surgery, chronic indwelling catheterization, or bladder cancer). 7Calculated by summing the degree of life impact (0–3) with each of the five activities and two emotional health items (range: 0–21). 8Calculated by summing the frequency (0–5, except for incontinence in the past year = 0–4) of 12 LUTS (range: 0–59) and then multiplying by 21/59 to obtain the same range as the impact score (range: 0–21). 9Calculated as the sum of the LUTS and life impact scores (range: 0–42). IIQ, Incontinence Impact Questionnaire; LUTS, lower urinary tract symptom.

Similar distributions of bladder health were observed when we explored single-item measures of well-being as when we included the IIQ (using the maximum frequency of LUTS: 16.2%–17.7% no LUTS or impact, 56.6%–57.8% some LUTS or impact, and 24.7%–26.6% LUTS almost always and the worst degree of impact; and using the number of LUTS: 16.2%–17.7%, 64.3%–65.7%, and 16.9%–18.7%, respectively; Appendix Table A3).

Prevalent LUTS associated with well-being

In analyses investigating LUTS associated with well-being, we observed generally similar findings using the IIQ as in our previous baseline analysis using the Epstein interference scale. Specifically, we found that several measures of storage function (urinating again after <2 hours, perceived frequency, nocturia, urgency and any incontinence, and urgency), pain in the pubic/bladder area, and incomplete emptying were independently, positively associated with prevalent life impact (Table 4). In addition, straining to begin urination was inversely associated with prevalent impact, and stress and nonstress/nonurgency incontinence were positively associated with impact. Each of these new associations was specific to use of the IIQ rather than the Epstein interference scale, except for positive findings for stress incontinence; these new findings were related to slight changes in the analytic sample at follow-up, as they were also observed when the analyses were repeated using the Epstein scale at follow-up (Appendix Table A4). Similar findings were also observed in sensitivity analyses excluding women with known bladder conditions, as well as non-bladder conditions that might contribute to LUTS or pain/discomfort in the pubic area. Finally, positive associations persisted for perceived frequency, all types of incontinence, and pain when we increased the thresholds for LUTS and impact, whereas those for other LUTS did not (data not shown).

Table 4.

Associations Between Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in the Past Month and Life Impact from Urinary Symptoms, Pain or Discomfort in the Pelvic or Bladder Area in a Community-Based Sample of 2292 Women; Boston Area Community Health Survey, 2008–2010

| LUTS (at least rarely in the past month) | Women with LUTS, N | Women without LUTS, N | Prevalence of at least slight impact, %a |

PR of at least slight impact (95% CI) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women without LUTS | Women with LUTS | Unadjusted | Adjustedb | p | Adjustedc | p | |||

| Urinating again after <2 hours | 1273 | 1017 | 8.4 | 34.4 | 4.1 (3.0–5.6) | 3.2 (2.3–4.3) | <0.001 | 1.9 (1.2–3.0) | 0.007 |

| Perceived frequency | 884 | 1407 | 11.9 | 42.5 | 3.6 (2.7–4.8) | 2.8 (2.1–3.7) | <0.001 | 1.4 (1.1–1.7) | 0.012 |

| Nocturia | 1054 | 1238 | 11.5 | 40.5 | 3.5 (2.7–4.6) | 2.7 (2.1–3.6) | <0.001 | 1.3 (1.1–1.7) | 0.016 |

| Stress incontinenced | 209 | 1871 | 15.7 | 79.4 | 5.1 (4.1–6.2) | 3.3 (2.7–4.1) | <0.001 | 2.1 (1.7–2.7) | <0.001 |

| Urgency incontinenced | 172 | 1824 | 19.6 | 69.8 | 3.6 (2.8–4.5) | 2.7 (2.3–3.2) | <0.001 | 1.6 (1.3–1.9) | <0.001 |

| Nonstress, nonurgency incontinenced | 149 | 2139 | 19.6 | 81.5 | 4.2 (3.4–5.1) | 2.5 (2.2–3.0) | <0.001 | 1.6 (1.3–1.9) | <0.001 |

| Dribbling/wet clothes after urination | 407 | 1883 | 17.2 | 51.8 | 3.0 (2.4–3.8) | 2.2 (1.8–2.7) | <0.001 | 0.9 (0.8–1.2) | 0.570 |

| Any incontinencee | 735 | 1554 | 12.6 | 44.2 | 3.5 (2.8–4.5) | 2.8 (2.2–3.6) | <0.001 | 1.9 (1.5–2.4) | <0.001 |

| Urgency/difficulty postponing urination | 815 | 1477 | 10.3 | 46.4 | 4.5 (3.5–5.9) | 3.7 (2.9–4.6) | <0.001 | 1.4 (1.1–1.9) | 0.015 |

| Pain, burning, discomfort in the pubic/bladder area | 320 | 1972 | 18.4 | 60.0 | 3.3 (2.5–4.2) | 2.2 (1.8–2.7) | <0.001 | 1.5 (1.2–1.9) | 0.001 |

| Straining/difficult to begin voiding | 235 | 2057 | 20.0 | 59.4 | 3.0 (2.3–3.7) | 1.9 (1.6–2.3) | <0.001 | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 0.040 |

| Weak stream | 313 | 1979 | 18.5 | 55.8 | 3.0 (2.4–3.9) | 2.2 (1.8–2.7) | <0.001 | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) | 0.491 |

| Intermittency | 398 | 1894 | 17.8 | 52.9 | 3.0 (2.3–3.8) | 2.1 (1.7–2.6) | <0.001 | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 0.838 |

| Incomplete emptying | 694 | 1598 | 14.6 | 43.8 | 3.0 (2.3–3.8) | 2.2 (1.7–2.8) | <0.001 | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) | 0.029 |

| Urinary tract infectione | 214 | 1817 | 21.4 | 40.1 | 1.9 (1.4–2.6) | 1.6 (1.2–2.0) | 0.001 | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 0.893 |

| Any LUTS | 1821 | 471 | 2.8 | 28.3 | 10.0 (4.8–20.8) | 7.0 (3.2–15.5) | <0.001 | — | — |

All values were weighted according to the sampling weights of the Boston Area Community Health Survey.

Adjusted for age (26–44, 45–64, or ≥65 years); race/ethnicity (black, Hispanic, or white); menopausal status (premenopausal/undetermined, perimenopausal, postmenopausal, or surgical); parity (0, 1–3, or ≥4 pregnancies); smoking status (current, former, or never smoker); alcohol intake (<1, 1–2, or ≥3 drinks); body mass index (<25, 25–29, or ≥30 kg/m2); waist circumference (<65, 65–89, 90–114, or ≥115 cm); health-related limitations in activities (not at all, a little, or a lot); self-reported physician diagnoses of high blood pressure, types I or II diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and arthritis; and depressive symptoms (yes or no).

Additionally adjusted for other LUTS individually, as appropriate.

Assessed in the past week.

Assessed in the past year.

CI, confidence interval; PR, prevalence ratio.

In analyses investigating each of the other single-item measures of well-being, generally similar findings were observed as for the IIQ, at least with respect to measures of storage function (urinating again after <2 hours, perceived frequency, nocturia, all types of incontinence, and urgency) and pain. Findings were less consistent for measures of emptying function (straining to begin voiding and incomplete emptying; Appendix Table A4).

Discussion

In this large, regionally representative analysis of bladder health in adult American women, we observed generally similar findings as in our previous analysis of bladder health that was limited to a well-being measure (i.e., interference scale) developed for men with BPH. Specifically, in this analysis, we observed that approximately one in five women might be considered to have optimal bladder health (i.e., no LUTS or diminished well-being; 16.2%–18.0%), three in five to have intermediate bladder health (i.e., some LUTS or diminished well-being; 55.8%–65.7%), and one in five to have poor bladder health (i.e., the maximum frequency, number, or degree of LUTS or diminished well-being; 16.9%–26.6%). These findings were observed irrespective of how we classified LUTS or assessed well-being. We also observed a right-skewed bladder health distribution when we modeled bladder health as a continuous score, indicating a greater density of scores at the lower end of the LUTS/well-being continuum. Finally, measures of storage dysfunction and pain tended to be independently associated with diminished well-being.

In addition to the consistency of our distributions of bladder health across all five well-being measures included in BACH, our estimates are also similar to those calculated in the Epidemiology of LUTS (EpiLUTS) study, the only other study, to our knowledge, to have published data on the joint distribution of LUTS and bladder-related well-being in women unselected for LUTS.21 In that multinational, population-based study of American, British, and Swedish women, 19.9%–21.3% of women ≥40 years of age reported no LUTS (using a cutoff point of “sometimes”), no problems with urinary symptoms, and/or being “delighted” or “pleased” with their current urinary symptoms; 51.0%–52.1% reported one to two types of LUTS (storage, voiding, or postmicturition), “some very minor” to “moderate” problems, and/or being “mostly satisfied” to “mostly dissatisfied” with their current symptoms; and 26.6%–29.1% reported three types of LUTS, “severe” to “many severe” problems, and/or feeling “unhappy” to “terribly” about their symptoms. These analyses used the same well-being measures as in our analysis (AUASI and bladder condition perception items), but a different categorization of LUTS (0, 1, 2, or 3 types of LUTS; all estimates calculated from Ref. 21).

We believe the similarity of these values to our estimates (16.2%–18.0%, 55.8%–65.7%, and 16.9%–26.6%, respectively) lends confidence to the overall concept of a spectrum of bladder health, as it does not appear to depend on study population (Boston area vs. entire United States, United Kingdom, and Sweden), method of categorizing LUTS (maximum frequency, type, or number), or type and length of bladder-related well-being or bother measures (degree of life impact, degree of thought, perception of bladder condition, and frequency of interference). Furthermore, our findings suggest that even brief and non-sex-specific measures of well-being may be sufficient to estimate crude distributions of bladder health. More refined measures will still, however, be necessary to estimate accurate distributions, taking into account other aspects of bladder health, such as adaptation to short-term stressors.4

With respect to LUTS associated with diminished well-being, we observed generally similar findings as in our previous baseline analysis using the Epstein interference scale,6 as well as in the EpiLUTS study.21 Specifically, each of these analyses observed that several individual measures of storage function (or dysfunction, e.g., frequency, perceived frequency, nocturia, and urgency incontinence) were independently associated with decreased well-being. These findings suggest that symptoms that are difficult to defer (i.e., frequent or urgent urination) tend to contribute to greater diminished well-being than those related to voiding once it has begun.

In summary, our similar findings to those from our previous baseline analysis of bladder health in the BACH Survey, as well as to those in the EpiLUTS Study, lend confidence to the overall concept of a spectrum of bladder health and reinforce the bothersome nature of storage dysfunction and pain. Future studies should investigate the distribution of bladder health in additional populations using more refined bladder health-specific measures, as well as the distribution of changes in bladder health over time to help support bladder health promotion and LUTS prevention efforts in women.

Acknowledgments

We thank the BACH Survey team for designing and implementing the BACH Survey, and Sarah Lindberg for assisting with data management and cleaning. We also thank Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (PLUS) research personnel at each PLUS center:

Loyola University Chicago—2160 South 1st Avenue, Maywood, IL 60153-3328.

Multiprincipal Investigators: Linda Brubaker, MD; and Elizabeth R. Mueller, MD, MSME.

Investigators: Colleen M. Fitzgerald, MD, MS; Cecilia T. Hardacker, MSN, RN, CNL; Jeni Hebert-Beirne, PhD, MPH; Missy Lavender, MBA; and David A. Shoham, PhD, MSPH.

University of Alabama at Birmingham—1720 2nd Avenue South, Birmingham, AL 35294.

Principal Investigator: Kathryn L. Burgio, PhD.

Investigators: Cora E. Lewis, MD, MSPH; Alayne D. Markland, DO, MSc; Gerald McGwin, Jr., MS, PhD; Camille P. Vaughan, MD, MS; and Beverly Rosa Williams, PhD.

University of California San Diego—9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, CA 92093-0021.

Principal Investigator: Emily S. Lukacz, MD.

Investigators: Sheila Gahagan, MD, MPH; D. Yvette LaCoursiere, MD, MPH; and Jesse Nodora, DrPH.

University of Michigan—500 South State Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48109.

Principal Investigator: Janis M. Miller, PhD, APRN, FAAN

Investigators: Lawrence Chin-I An, MD; and Lisa Kane Low, PhD, CNM, FACNM, FAAN.

University of Minnesota—3 Morrill Hall, 100 Church Street S.E., Minneapolis, MN 55455.

Multiprincipal Investigators: Bernard L. Harlow, PhD; and Kyle D. Rudser, PhD.

Investigators: Sonya S. Brady, PhD; Haitao Chu, MD, PhD; John Connett, PhD; M.L. Constantine, PhD, MPAff; Cynthia S. Fok, MD, MPH; and Todd Rockwood, PhD.

University of Pennsylvania—Urology, 3rd FL West, Perelman Bldg, 34th and Spruce Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104.

Principal Investigator: Diane K. Newman, DNP FAAN.

Investigators: Amanda Berry, MSN, CRNP; C. Neill Epperson, MD; Kathryn H. Schmitz, PhD, MPH, FACSM, FTOS; Ariana L. Smith, MD; Ann E. Stapleton, MD; and Jean F. Wyman, PhD.

Washington University in St. Louis—600 South Taylor Avenue, Saint Louis, MO 63110-1035.

Principal Investigator: Siobhan Sutcliffe, PhD, ScM, MHS.

Investigators: Aimee S. James, PhD, MPH; Jerry L. Lowder, MD, MSc; and Melanie R. Meister, MD, MSCI (July 2019).

Yale University—PO Box 208058 New Haven, CT 06520-8058.

Principal Investigator: Leslie M. Rickey, MD, MPH.

Investigators: Deepa R. Camenga, MD, MHS; Shayna D. Cunningham, PhD; Toby C. Chai, MD (July 2015 to July 2019); and Jessica Lewis, PhD.

Steering Committee Chair: Mary H. Palmer, PhD, RN; University of North Carolina.

NIH Program Office: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Division of Kidney, Urologic, and Hematologic Diseases, Bethesda, MD.

NIH Project Scientist: Tamara Bavendam MD, MS; Project Officer: Ziya Kirkali, MD; Scientific Advisors: Chris Mullins, PhD and Jenna Norton, MPH.

Appendix

Appendix Table A1.

Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Assessed in the Boston Area Community Health Survey at baseline and 5 Years Later at Follow-Up, 2002–2010

| Items collected in the BACH Survey | Collapsed items |

|---|---|

| Number of times you accidentally leaked urine without any particular physical activity or warning in the past 7 days | Nonstress, nonurgency incontinence in the past week |

| Number of bladder infections in the past yeara | Urinary tract infection in the past year |

| Number of kidney infections in the past yeara | |

| Push or strain to begin urination in the past monthb | Straining/difficult to begin voiding |

| Difficulty starting to urinate in the past monthb | |

| Pain or burning during urination in the past monthc | Pain, burning, discomfort in the pubic/bladder area in the past month |

| Pain, burning, discomfort, or pressure in your pubic or bladder area in the past monthc | |

| Pain or discomfort in your urethra in the past monthc | |

| Pain increasing when your bladder fills in the past monthc | |

| Pain relieved by urination in the past monthc | |

| Weak urinary stream in the past month | Weak stream in the past month |

| Number of times you accidentally leaked urine when you had the strong feeling that you needed to empty your bladder but you could not get to the toilet fast enough in the past 7 days | Urgency incontinence in the past week |

| Baseline: Dribbling after urination in the past monthd | Dribbling/wet clothes after urination in the past month |

| Follow-up: Urine leakage almost immediately after you have finished urinating and walked away from the toilet in the past month?e | |

| Follow-up: A prolonged trickle or dribble at the end of your urine flow in the past month?e | |

| Baseline: Wet clothes because of dribbling after urination in the past monthd | |

| Stop and start again several times while you urinate in the past month | Intermittency in the past month |

| Number of times you accidentally leaked urine when you were performing some physical activity such as coughing, sneezing, lifting, or exercise, in the past 7 days | Stress incontinence in the past week |

| Sensation of not emptying your bladder completely after you have finished urinating in the past month | Incomplete emptying in the past month |

| Leaked even a small amount of urine in the past 12 months, including frequency and amount | Any incontinence in the past year |

| Difficulty postponing urination in the past monthf | Urgency/difficulty postponing urination in the past month |

| Strong urge or pressure to urinate immediately, with no, or little warning in the past monthf | |

| Get up to urinate more than once during the night in the past month | Nocturia in the past month |

| Frequent urination during the day in the past monthg | Perceived frequency in the past month |

| Urinate again less than 2 hours after you finished urinating in the past monthg | Urinating again after <2 hours in the past month (frequency) |

| Strong urge or pressure that signaled the need to urinate immediately, whether or not you urinated or leaked urine in the past 7 days | —h |

Percent disagreement at baseline (comparing those without a particular LUTS to those who reported experiencing it at least rarely) = 7.2%.

Percent disagreement at baseline = 6.2%.

Percent disagreement at baseline = 4.3%–7.9%.

Percent disagreement at baseline = 5.8%.

Percent disagreement at follow-up = 14.7%.

Percent disagreement at baseline = 18.9%.

Percent disagreement at baseline = 25.8%.

Not included in the analysis.

BACH, Boston Area Community Health Survey; LUTS, lower urinary tract symptom.

Appendix Table A2.

Joint Distribution of Prevalent Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in the Past Month and Degree of Impact from Urinary Symptoms, Pain or Discomfort in the Pelvic or Bladder Area in Women by Age Group; Boston Area Community Health Survey, 2008–2010

|

All values were weighted according to the sampling weights of the Boston Area Community Health Survey.

Maximum frequency of LUTS across 12 LUTS (urinating again after <2 hours; perceived frequency; nocturia; any incontinence [in the past year]; dribbling/wet clothes after urination; urgency/difficulty postponing urination; pain, burning, discomfort in the pubic/bladder area; straining/difficult to begin voiding; weak stream; intermittency; incomplete emptying; and urinary tract infection [in the past year]).

Maximum degree of impact across seven activities or aspects of life.

Represents the percentage of women who reported the highest category of LUTS and impact.

Represents the percentage of women with self-reported current or past bladder conditions (i.e., use of current LUTS medications, previous incontinence or bladder surgery, chronic indwelling catheterization, or bladder cancer).

IIQ, Incontinence Impact Questionnaire.

Appendix Table A3.

Joint Distribution of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in the Past Month and Well-Being Related to Urinary, Bladder, and/or Pelvic Pain Symptoms/Condition in a Community-Based Sample of 2527 Women; Boston Area Community Health Survey, 2008–2010

|

All values were weighted according to the sampling weights of the Boston Area Community Health Survey.

Maximum frequency of LUTS across 12 LUTS (urinating again after <2 hours; perceived frequency; nocturia; any incontinence [in the past year]; dribbling/wet clothes after urination; urgency/difficulty postponing urination; pain, burning, discomfort in the pubic/bladder area; straining/difficult to begin voiding; weak stream; intermittency; incomplete emptying; and urinary tract infection [in the past year]).

Number of LUTS experienced at least rarely in the past month (out of the 12 LUTS described above).

Represents the percentage of women who reported the highest category (or categories) of LUTS and diminished well-being.

Represents the percentage of women with self-reported current or past bladder conditions (i.e., use of current LUTS medications, previous incontinence or bladder surgery, chronic indwelling catheterization, or bladder cancer).

AUASI, American Urological Association Symptom Index.

Appendix Table A4.

Prevalence Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals of Diminished Well-Being Related to Urinary Symptoms, Pain or Discomfort in the Pelvic or Bladder Area in a Community-Based Sample of 2292 Women; Boston Area Community Health Survey, 2008–2010

| LUTS (at least rarely in the past month) | At least only a little thought |

Mostly satisfied or worse life impact (AUASI) |

Very minor or worse problems |

Interference at least a little of the time |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusteda | p | Adjusteda | p | Adjusteda | p | Adjusteda | p | |

| Urinating again after <2 hours | 1.3 (1.0–1.8) | 0.095 | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 0.033 | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 0.004 | 1.9 (1.4–2.4) | <0.001 |

| Perceived frequency | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) | 0.021 | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 0.001 | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) | 0.258 | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | <0.001 |

| Nocturia | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | 0.323 | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 0.003 | 1.2 (1.1–1.5) | 0.004 | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) | <0.001 |

| Stress incontinenceb | 1.7 (1.5–2.0) | <0.001 | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) | <0.001 | 1.2 (1.1–1.4) | 0.002 | 1.2 (1.1–1.4) | 0.001 |

| Urgency incontinenceb | 1.5 (1.3–1.8) | <0.001 | 1.2 (1.1–1.4) | <0.001 | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | <0.001 | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 0.261 |

| Nonstress, nonurgency incontinenceb | 1.5 (1.3–1.7) | <0.001 | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 0.063 | 1.2 (1.1–1.4) | <0.001 | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) | 0.308 |

| Dribbling/wet clothes after urination | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) | 0.235 | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 0.546 | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 0.611 | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 0.118 |

| Any incontinenceb | 1.7 (1.4–2.0) | <0.001 | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | <0.001 | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | <0.001 | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 0.573 |

| Urgency/difficulty postponing urination | 1.8 (1.3–2.4) | <0.001 | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 0.006 | 1.6 (1.3–2.0) | <0.001 | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 0.002 |

| Pain, burning, discomfort in the pubic/bladder area | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) | 0.001 | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 0.073 | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 0.002 | 1.1 (0.9–1.2) | 0.416 |

| Straining/difficult to begin voiding | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) | 0.005 | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 0.281 | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 0.995 | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 0.309 |

| Weak stream | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 0.004 | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.710 | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 0.149 | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 0.636 |

| Intermittency | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 0.904 | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 0.295 | 1.0 (0.8–1.1) | 0.646 | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.991 |

| Incomplete emptying | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 0.659 | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 0.116 | 1.0 (0.8–1.1) | 0.797 | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | 0.010 |

| Urinary tract infectionc | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 0.294 | 1.0 (0.8–1.1) | 0.514 | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 0.357 | 1.1 (0.9–1.2) | 0.447 |

| Any LUTS | 8.8 (4.2–18.6) | <0.001 | 3.7 (2.5–5.6) | <0.001 | 6.0 (3.6–10.1) | <0.001 | 6.6 (4.1–10.7) | <0.001 |

All values were weighted according to the sampling weights of the Boston Area Community Health Survey.

Adjusted for age (26–44, 45–64, or ≥65 years); race/ethnicity (black, Hispanic, or white); menopausal status (premenopausal/undetermined, perimenopausal, postmenopausal, or surgical); parity (0, 1–3, or ≥4 pregnancies); smoking status (current, former, or never smoker); alcohol intake (<1, 1–2, or ≥3 drinks); body mass index (<25, 25–29, or ≥30 kg/m2); waist circumference (<65, 65–89, 90–114, or ≥115 cm); health-related limitations in activities (not at all, a little, or a lot); self-reported physician diagnoses of high blood pressure, types I or II diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and arthritis; depressive symptoms (yes or no), and other LUTS individually, as appropriate.

Assessed in the past week.

Assessed in the past year.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Prevention of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Research Consortium, Linda Brubaker, Elizabeth R. Mueller, Cecilia T. Hardacker, Jeni Hebert-Beirne, Missy Lavender, Kathryn L. Burgio, Cora E. Lewis, Gerald McGwin, Jr., Camille P. Vaughan, Beverly Rosa Williams, Emily S. Lukacz, D. Yvette La-Coursiere, Jesse Nodora, Janis M. Miller, Lawrence Chin-I An, Lisa Kane Low, Bernard L. Harlow, Sonya S. Brady, Haitao Chu, John Connett, M.L. Constantine, Cynthia S. Fok, Todd Rockwood, Amanda Berry, Kathryn H. Schmitz, Ann E. Stapleton, Jean F. Wyman, Aimee S. James, Jerry L. Lowder, Melanie R. Meister, Leslie M. Rickey, Deepa R. Camenga, Shayna D. Cunningham, Toby C. Chai, Jessica Lewis, Mary H. Palmer, Ziya Kirkali, Chris Mullins, and Jenna Norton

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) by cooperative agreements (Grants U01DK106786, U01 DK106853, U01 DK106858, U01 DK106898, U01 DK106893, U01 DK106827, U01 DK106908, and U01 DK106892). Additional funding was from National Institute on Aging, NIH Office on Research in Women's Health and the NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Science.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Constitution of the World Health Organization. Basic Doc, 45th ed., Geneva: WHO, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, et al. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: The American Heart Association's strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation 2010;121:586–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gorelick PB, Furie KL, Iadecola C, et al. Defining optimal brain health in adults: A presidential advisory from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2017;48:e284–e303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lukacz ES, Bavendam TG, Berry A, et al. A novel research definition of bladder health in women and girls: Implications for research and public health promotion. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2018;27:974–981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lowder JL, Bavendam TG, Berry A, et al. Terminology for bladder health research in women and girls: Prevention of lower urinary tract symptoms transdisciplinary consortium definitions. Neurourol Urodyn 2019;38:1339–1352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sutcliffe S, Bavendam T, Cain C, et al. The spectrum of bladder health: The relationship between lower urinary tract symptoms and interference with activities. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2019;28:827–841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McKinlay JB, Link CL. Measuring the urologic iceberg: Design and implementation of the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey. Eur Urol 2007;52:389–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barry MJ, Fowler FJ Jr., O'leary MP, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol 1992;148:1549–1557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sandvik H, Seim A, Vanvik A, Hunskaar S. A severity index for epidemiological surveys of female urinary incontinence: Comparison with 48-hour pad-weighing tests. Neurourol Urodyn 2000;19:137–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. O'Leary MP, Sant GR, Fowler FJ Jr., Whitmore KE, Spolarich-Kroll J.. The interstitial cystitis symptom index and problem index. Urology 1997;49:58–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Uebersax JS, Wyman JF, Shumaker SA, McClish DK, Fantl JA. Short forms to assess life quality and symptom distress for urinary incontinence in women: The Incontinence Impact Questionnaire and the Urogenital Distress Inventory. Continence Program for Women Research Group. Neurourol Urodyn 1995;14:131–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Epstein RS, Deverka PA, Chute CG, et al. Validation of a new quality of life questionnaire for benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:1431–1445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Litwin MS, Mcnaughton-Collins M, Fowler FJ, et al. The National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis symptom index: Development and validation of a new outcome measure. Chronic Prostatitis Collaborative Research Network. J Urol 1999;162:369–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Coyne KS, Matza LS, Kopp Z, Abrams P. The validation of the patient perception of bladder condition (PPBC): A single-item global measure for patients with overactive bladder. Eur Urol 2006;49:1079–1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Turvey CL, Wallace RB, Herzog R. A revised CES-D measure of depressive symptoms and a DSM-based measure of major depressive episodes in the elderly. Int Psychogeriatr 1999;11:139–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wiesel A, Queisser-Luft A, Clementi M, et al. Prenatal detection of congenital renal malformations by fetal ultrasonographic examination: An analysis of 709,030 births in 12 European countries. Eur J Med Genet 2005;48:131–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Postoev VA, Grjibovski AM, Kovalenko AA, et al. Congenital anomalies of the kidney and the urinary tract: A murmansk county birth registry study. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2016;106:185–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna. Austria: R Core Team, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lumley T. Survey: Analysis of complex survey samples. R package version 3.32. 2017

- 20. Lumley T. Analysis of complex survey samples. J Stat Softw 2004;9:1–19 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Coyne KS, Wein AJ, Tubaro A, et al. The burden of lower urinary tract symptoms: Evaluating the effect of LUTS on health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression: EpiLUTS. BJU Int 2009;103(Suppl 3):4–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wu JM, Matthews CA, Vaughan CP, Markland AD. Urinary, fecal, and dual incontinence in older U.S. Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63:947–953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]