Abstract

Mutations in the DEPDC5 gene can cause epilepsy, including forms with and without brain malformations. The goal of this study was to investigate the contribution of DEPDC5 gene dosage to the underlying neuropathology of DEPDC5-related epilepsies. We generated induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from epilepsy patients harboring heterozygous loss of function mutations in DEPDC5. Patient iPSCs displayed increases in both phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6 and proliferation rate, consistent with elevated mTORC1 activation. In line with these findings, we observed increased soma size in patient iPSC-derived cortical neurons that was rescued with rapamycin treatment. These data indicate that human cells heterozygous for DEPDC5 loss-of-function mutations are haploinsufficient for control of mTORC1 signaling. Our findings suggest that human pathology differs from mouse models of DEPDC5-related epilepsies, which do not show consistent phenotypic differences in heterozygous neurons, and support the need for human-based models to affirm and augment the findings from animal models of DEPDC5-related epilepsy.

Keywords: Induced pluripotent stem cells, disease modeling, mTOR, epilepsy, molecular genetics, neurodevelopment, neuronal differentiation

1. Introduction

Despite numerous available antiseizure medications, over one-third of patients with epilepsy are refractory to treatment (Chen et al., 2018). Epilepsies due to pathogenic mutations in DEP domain-containing protein 5 (DEPDC5) have even higher rates of drug-resistance, often greater than 50% (Baldassari et al., 2019a; Picard et al., 2014). While initially described in autosomal dominant familial focal epilepsies, DEPDC5 mutations have also been described in other epilepsy types, including epilepsies with focal cortical dysplasia (FCD) (Baulac et al., 2015; D'Gama et al., 2015; Dibbens et al., 2013; Ishida et al., 2013; Kaur, 2013; Lal et al., 2014; Martin et al., 2014; Scerri et al., 2015; Scheffer et al., 2014). Notably, FCD is highly associated with medically refractory epilepsy further accentuating the need for improved understanding of disease pathogenesis due to DEPDC5 mutations (Crino, 2015).

DEPDC5 encodes an essential component of the GATOR1 complex, a negative regulator of the mTOR (mammalian/mechanistic target of rapamycin) pathway (Bar-Peled et al., 2013). mTOR kinase is a key regulator cell size and protein translation and exists in at least two distinct complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2. As a negative regulator of mTORC1, experimental knockdown of DERDC5 leads to hyperactive mTORC1 signaling (Bar-Peled et al., 2013; Iffland et al., 2018). In the central nervous system, mTORC1 plays a role in the differentiation of neural stem cells, drives the proliferation of neuroprogenitor cells, and is required for dendrite formation (Li et al., 2018; Lipton and Sahin, 2014; Saxton and Sabatini, 2017). Dysregulation of mTORCI signaling due to DEPDC5 mutation likely has numerous consequences for brain development and neuronal function, ultimately resulting in epilepsy.

The underlying mechanisms of how DEPDC5 mutations result in dysplastic neurons and epilepsies are not clear. In cases of epilepsies with FCD, acquisition of a somatic “second hit” is likely. Indeed, several case reports and a recent cohort study support a model of a mutation gradient of biallelic DEPDC5 mutation in epilepsies with associated FCD (Baldassari et al., 2019b; Baulac et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2019; Ribierre et al., 2018). Similarly, rodent models with mosaic homozygous brain inactivation of Depdc5 have a FCD-like phenotype with focal seizures (Hu et al., 2018; Ribierre et al., 2018). While these studies provide important evidence to explain how a germline loss-of-function mutation can cause focal epilepsies, only about 25% of patients with epilepsy due to DEPDC5 mutations have reported malformations of cortical development, including FCD (Baldassari et al., 2019a). In DEPDC5-related epilepsies without FCD, it is unknown if areas of FCD exist that are not apparent with current imaging sensitivity or whether other mechanisms lead to epilepsy in these cases. Specifically, potential consequences of a heterozygous mutation in DEPDC5 are not definitively known. When studied in rodent models, consequences of Depdc5 haploinsufficiency have been variable. For example, rats lacking one copy of Depdc5 demonstrated enlarged neurons with abnormal electrophysiological properties (Marsan et al., 2016). In heterozygous mice, one model reported no changes in neuronal size or mTORC1 activation, while another model found increased mTORC1 activation in cortical neurons with no corresponding increase Pre-proofin neuronalsize (Hughes et al., 2017;De Fusco et al., 2020). No Depdc5 heterozygous animal models have displayed seizures, suggesting that haploinsufficiency alone does not cause epilepsy in rodents (Hughes et al., 2017; Marsan et al., 2016; Yuskaitis et al., 2018; Klofas et al., 2020 ).However, the impact of heterozygous loss of DEPDC5 has not been characterized in human patient-derived cell lines. Neuronal cultures derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) thus provide a promising complementary experimental approach to animal models. As most studies in immortalized human cell lines have been done in the context of homozygous loss or knockdown of DEPDC5, it is unclear how heterozygous loss of DEPDC5 might affect patient-derived stem cells and derivative neurons (Bar-Peled et al., 2013; Iffland et al., 2018).

This study aims to determine the effects of heterozygous DEPDC5 mutation on mTOR pathway activation and neuronal size in patient-derived cell lines. To better understand the effects of DEPDC5 haploinsufficiency in humans, we generated iPSCs and neurons from epilepsy patients with inactivating mutations in DEPDC5. We found that heterozygous mutations in DEPDC5 allow increased mTORC1 signaling activity in iPSCs and derivative neurons. Corresponding changes in neuronal size were responsive to chronic treatment with rapamycin. These results reveal a potential role for DEPDC5 haploinsufficiency in contributing to neuronal dysfunction by driving increased mTORC1 signaling.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Generation of iPSCs from epilepsy patients with DEPDC5 mutations

After obtaining informed consent from patients or their legal guardians under Vanderbilt Institutional Review Board protocol #080369, fibroblasts were isolated by 3 mm skin punch biopsies from patients and control donors with no history of epilepsy. Fibroblasts from the biopsies were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. iPSCs were generated from fibroblasts as previously described, either via transduction with non-integrating Sendai virus-based reprogramming vectors or Pre-proof via electroporation with episomal vectors (Armstrong et al., 2017). Sendai reprogramming was performed using the CytoTune iPS 2.0 Sendai Kit (ThermoFisher) in feeder-free conditions according to the manufacturer‘s instructions. After one week, nascent stem cells were passed to Matrigel and grown in mTeSR1 media (Corning; Stem Cell Technologies). iPSCs were confirmed to be Sendai vector-free after 5–10 passages using RT-PCR. Fibroblasts were also reprogrammed by transfection of cells using the Neon system (Invitrogen) with plasmids expressing KLF4, SOX2, OCT4, L-MYC and LIN28 (Addgene #27076, 27077, 27078, 27080) according to previously published protocols (Okita et al., 2011). Cells were switched to TeSR-E7 media (Stem Cell Technologies) 48 h post-transfection. After three weeks, emerging defined iPSC-like colonies were manually picked and transferred to plates coated with a 1:25 dilution of Matrigel (Corning/BD Sciences 354277) in DMEM/F12 (ThermoFisher 11320033). iPSCs were maintained in feeder-free conditions with daily media changes with m TeSR1 (Stem Cell Technologies 85850). iPSCs were passaged once per week for maintenance using ReLeSR (Stem Cell Technologies 05873) at a ratio of 1:25. All experiments were performed within 50 passages of the original iPSC generation.

2.2. Validation of iPSCs

iPSCs colonies had typical morphology (Fig. S1C). New iPSC lines were validated through trilineage differentiation assays, pluripotency marker immunostaining, and karyotype analysis. For trilineage immunostaining, iPSCs were differentiated as embryoid bodies for ten to fourteen days in DMEM/F12 GlutaMax with 20% knockout serum replacement, 1X non-essential amino acids and 55 μM β-mercaptoethanol, and then probed for lineage markers defining ectoderm (Sox1, β-III-Tubulin), mesoderm (smooth muscle actin, brachyury, and/or desmin), and endoderm (GATA4, Sox17) (Fig. S1D). Immunostaining was performed for pluripotency markers Oct4, Nanog, TRA-1–60, and SSEA3 (Fig. S1E). Karyotype analysis of iPSC clones was performed using standard techniques; all lines used in experiments had normal karyotypes (Genetic Associates, Inc., Nashville, TN) (Fig. S1F). DEPDC5 gene mutations in iPSC lines were confirmed by direct DNA sequencing (Fig. S1G). Genomic DNA was extracted via DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA extracts were amplified by PCR using Phusion Flash (F-548S) and the resultant PCR products sequenced via Sanger sequencing (GenHunter). Sequencing primers are listed in Supplemental Table 2. PluriTest analysis (ThermoFisher) demonstrated high pluripotency scores for all iPSC lines(Fig. S1H).

2.3. mRNA quantification

Total RNA was extracted from iPSCs and neurons using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen #74134) and QIAShredder columns (Qiagen #79654) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA digestion was performed using either on-column DNA digestion (Qiagen #79254) or gDNA wipeout buffer (Qiagen #205311). cDNA was synthesized using random primers with the SuperScript VILO cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen #11754) or Quantitect Reverse Transcription kit (Qiagen #205311). Real-time PCR was then performed with Taqman assays (ThermoFisher) using a CFX96 Touch (Bio-Rad). Primers with overlapping exon-exon boundaries were selected to prevent amplification of genomic DNA. Reactions were run in quadruplicate and expression data were normalized to the mean of housekeeping gene HPRT1 to control for the variability in expression levels and analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Assays used are listed in Supplemental Table 2.

2.4. Immunoblotting

Cultured cells were rinsed twice with 1X D-PBS, collected by scraping, and lysed by sonication in RIPA buffer (PBS with 1% NP40, 0.5% Na deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Sigma), then clarified via centrifugation at 10,000×g for 10 min at 4°C. Protein concentrations were calculated using the Bradford method (Bio-Rad). Samples were diluted with 3× loading buffer (0.25 MTris-HCl, 40% glycerol, 8%SDS, 15% BME, 0.008% bromophenol blue) and separated by electrophoresis on 4–12% Bis-Tris gels, followed by tank transfer to polyvinylidene difluoridemembrane (Pall Corp., Pensacola, FL, USA). Membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature in Odyssey blocking buffer (LI-COR927–40000 or 927–0001), then incubated with primary antibody at 4°C overnight in 5% BSA in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20 Journal(TBS-T). Blots were washed with TBS-T and then probed with fluorescent-tagged secondary antibodies diluted in TBS-T with 5% BSA and 0.01% SDS. Fluorescent-conjugated secondary antibodies were visualized using an Odyssey fluorescence scanner set at default intensity, high quality, with 84 μm resolution. After visualization, digitized band densities were quantified using the Odyssey quantification software ImageStudio Lite. The integrated intensities of bands were measured using default settings with the 3-pixel-width border mean average background correction method. Bands that were measured for quantification are indicated by the red boxes in the supplemental material. If possible, phosphoproteins were normalized to total protein. Specifically, p-S6 S240/244 was normalized to total S6 protein, p-AKT S473 was normalized to total AKT, and p-4E-BP1 was normalized to total 4EBP1. NPRL2 was normalized to β-actin as an internal reference protein. Following normalization of all samples, data were then compared to % average control. See Supplemental Table 3 for antibody dilutions and manufacturers.

2.5. Doubling time assays

100,000 cells per well were seeded in 12-well plates in mTeSR1 and Rock inhibitor. After 24 hours, treatment (10 nM rapamycin or vehicle − 60% PBS/40% DMSO) was applied. Cells were dissociated to single cells using Accutase and counted at 24, 48, 72, 96, 120, and 144 hours. A Nexelcom Cellometer Auto T4 was used for counting. Growth curves were plotted and population doubling time was calculated from the linear portion of the growth curve (days 3–5) using the equation (t2 – t1)/3.32 × (logn2 -logn1).

2.6. Flow cytometry - iPSCs

Cultured iPSCs were collected for flow cytometry experiments using previously described protocols (Rushing et al., 2019). Media was removed from the dish and iPSCs were treated with Accutase with ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 for 10 minutes at 37°C with 5% CO2, then quenched with their original conditioned media (mTeSR1) and triturated into a single-cell suspension. Cells were pelleted at 200 × g and resuspended in their original conditioned media (mTeSR1), then rested 75 minutes, with Alexa Fluor 700-SE dye (A-20010; Life Technologies) added for the last 15 min of incubation to label non-intact cells. Subsequently, the cells were fixed with a final concentration of 1.6% PFA for 20 min at room temperature, washed with 1× PBS, and spun for 5 min at 800 × g at room temperature. Supernatant was decanted and cells were resuspended in the void volume using vigorous vortexing. 100% cold methanol was added to permeabilize cells. Cells were stored in methanol at −80°C until staining. After fixation and permeabilization, intracellular staining was conducted for 1 hour at room temperature using directly-labeled primary antibodies in PBS with 1% bovine serum albumin. All antibody clones and dilutions are listed in Supplemental Table 3. Following staining, cells were run on a BD LSR || 5-laser cytometer. Single fluorophore–labeled beads and unstained cell lines were used as compensation and sizing controls. For signal quantification, the arcsinh transformed median fluorescence intensity of per-cell phosphoprotein of stained samples was compared to unstained samples from the same experiment. The inverse hyperbolic sine (arcsinh) with a cofactor was used to measure signaling intensity in samples as previously described (Irish et al., 2010). The arcsinh median of intensity value × with cofactor c was calculated as arcsinhc(x) = ln(x/c + √((x/c)2 + 1)). The cofactor (c) is a fluorophore-specific correction for signal variance. All analyses were completed using Cytobank software (Kotecha et al., 2010).

2.7. Generation of cortical neural progenitor cells and neurons from iPSCs

iPSCs were neuralized using a dual-SMAD inhibition protocol described by Shi et al. with minor modifications (Shi et al., 2012)(Fig.S4A). Briefly, iPSCs were plated at a concentration of 1×106 per well in 12-well plates coated with Matrigel. At day 0, the culture medium was changed to neural induction medium (50/50 mix of Neurobasal and DMEM/F12) with small-molecule inhibitors of SMAD (SB-431542, 10 μM; LDN-193189, 100 nM). Once uniform (day 10), the neuroepithelial sheet was passed using Dispase (StemCell Technologies 07923). On day 11, the medium was changed to neural maintenance medium without SMAD inhibitors. 20 ng/mL FGF2 was added to the medium for three days (days 16–18) upon the appearance of neural rosettes. Neural rosettes were passed with Dispase on day 20. Cells were expanded a final time at day 30 using Accutase and maintained in neuronal maintenance medium.

2.8. Neuronal size analysis

Neuroprogenitor cells were dissociated to single cells at differentiation day 10 using Accutase and plated sparsely in order to distinguish individual cells (1.5×104 cells/cm2). After 24 hours, cells were fixed and immunostained with p-S6 S240/244 (mTORC1 target), nestin (neuroprogenitor cells), and phalloidin to label filamentous actin (F-Actin). F-Actin+ soma area was quantified using ImageJ (NIH, version 1.51n). In a blinded fashion, soma area of >50 cells per experimental group was measured in patient and control lines, with n=3 differentiations per experiment. Overlapping cells with unclear borders were excluded from measurement. Mean area and standard deviation were calculated from each differentiation and results were compared for statistical significance. For p-S6 (S240/244) intensity analysis in NPCs, p-S6+ soma size was measured and the integrated density was divided by soma area to obtain mean p-S6 fluorescence intensity. For early neurons, cells were dissociated and sparsely replated on differentiation day 20 and fixed for immunostaining 24 hours later. Post-mitotic neurons were replated after differentiation day 65 and fixed after 72 hours. For early neurons and post-mitotic neurons, MAP2+ soma area was quantified.

2.9. Starvation assays

Ten to fourteen days before the experiment, neurons were plated in 6-well plates containing Matrigel at a concentration of 1 million cells per well. Two hours prior to starvation, media was changed to fresh neuronal maintenance media (NMM) containing B27 and N2 supplements. Fresh baseline media (NMM) or nutrient-limited media (NLM, consisting of DMEM lacking amino acids (USBiological D9800–13)) was added at time zero. Cells were harvested and lysed for protein after 1 hour, then analyzed via immunoblot.

2.10. Statistical analysis and controls

We used cell lines from two individual healthy controls and three individual patients with DEPDC5-related epilepsy. Multiple iPSC clones derived from each fibroblast patient line were generated and initial experiments were performed using multiple clones from each line to ensure reproducibility. Multiple differentiations were performed to control for variability between differentiations. Each clone or differentiation was considered statistically as a biological replicate. The number of clones and specific clones used for each set of experiments is provided in Supplemental Table 4. Data from continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD. Two-group comparisons were performed using a t test or Mann-Whitney U test for non-parametric data. Three-group or greater comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons for experiments with one independent variable or two-way ANOVA for experiments with two independent variables. For two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s multiple comparisons was used when comparing all means and Sidak’s multiple comparisons was used when a set of means was selected. p<.05 was considered statistically significant.GraphPad Prism 8 was used to complete statistical tests. See Supplementary Table 5 for complete statistics and sample sizes for all experiments.

3. Results

3.1. Generation of iPSCs from epilepsy patients with DEPDC5 mutations

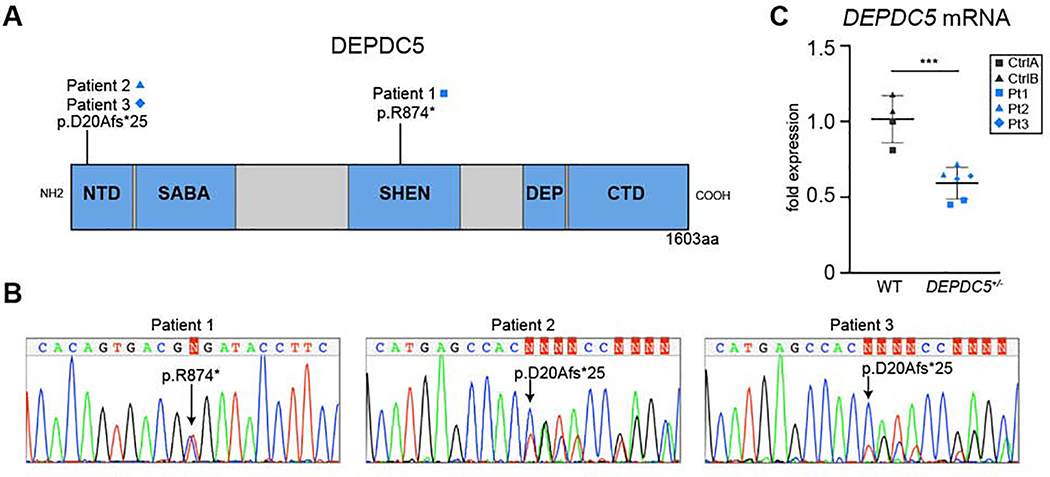

To determine the consequences of DEPDC5 haploinsufficiency in patient-derived neurons, we generated iPSC lines from three patients (Pt1, Pt2, and Pt3) with epilepsy and DEPDC5 loss of function mutations. The patient lines were generated from individuals with epilepsy and family histories suggestive of autosomal dominant nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy (ADNFLE) syndrome (Fig. S1A–B). Genetic testing of Pt1 revealed a pathogenic DEPDC5 mutation (c.2620C>T, p.Arg874X) occurring in the SHEN domain (Fig. 1A) (D'Gama et al., 2017; Lal et al., 2014; Shen et al., 2018). In Pt2 and Pt3, who were first-degree relatives, targeted genomic sequencing revealed a 1291 base pair deletion in DEPDC5, including exon 2 and portions of the surrounding introns (c.59–493_146+710), resulting in a frameshift truncation (D20Afs*25) (Fig. 1A). All three patients had normal brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans suggesting absence of detectable focal cortical dysplasia (data not shown). Additional patient characteristics are detailed in Supplemental Table 1. Control lines were generated from healthy first-degree relatives or unrelated volunteers (CtrlA, CtrlB) who did not have epilepsy or DEPDC5 mutations.

Figure 1. iPSCs generated from patients with epilepsy and DEPDC5 mutations have decreased DEPDC5 expression.

(A) Cartoon structure of DEPDC5 protein domains indicating the locations of patient mutations. NTD: N-Terminal Domain, SHEN: Steric Hindrance for Enhancement of Nucleotidase-activity, SABA: Structural Axis for Binding Arrangement, DEP: Dishevelled, EGL-10, and Pleckstrin, CTD: C-Terminal Domain. (B) Sequencing of representative patient-derived iPSC lines showing a single base pair mutation in patient 1 (c.2620C>T; p.R874*) and 1291 bp deletion in patients 2 and 3 (c.59–493_146+710; p.D20Afs*25). (C) mRNA expression inpatient-derived cell lines heterozygous for DEPDC5 mutations. Experiments represent the average of three technical replicates, n=2 controls and n=3 patients, two clones each. Unpaired t-test, p=.0009. Bars represent mean ± SD. See Figure S1, S2, and Table S1 for additional patient characteristics, iPSC validation, and DEPDC5 mRNA expression of individual patient lines.

To functionally validate iPSC lines, trilineage differentiation assays were performed which demonstrated that all clones were pluripotent and able to differentiate into all three embryonic germ layers (Fig. S1C). DNA sequencing was performed to confirm the patient mutations in each clone (Fig. 1B, S1D). Because of limitations in the specificity of available antibodies directed against DEPDC5, we measured DEPDC5 mRNA levels to determine if loss of a single copy of DEPDC5 altered mRNA expression. The majority of DEPDC5 mutations associated with focal epilepsies cause premature truncations of the transcript, likely leading to nonsense-mediated decay (Baldassari et al., 2016). Evidence of nonsense-mediated decay has been experimentally confirmed for several DEPDC5 disease variants (Picard et al., 2014). Our patient lines had reduced levels of DEPDC5 mRNA transcripts, suggesting that these DEPDC5 truncation mutations similarly caused nonsense-mediated decay (Fig. 1C).

3.2. Increased mTORC1 signaling iniPSCs from patients with DEPDC5-related epilepsy

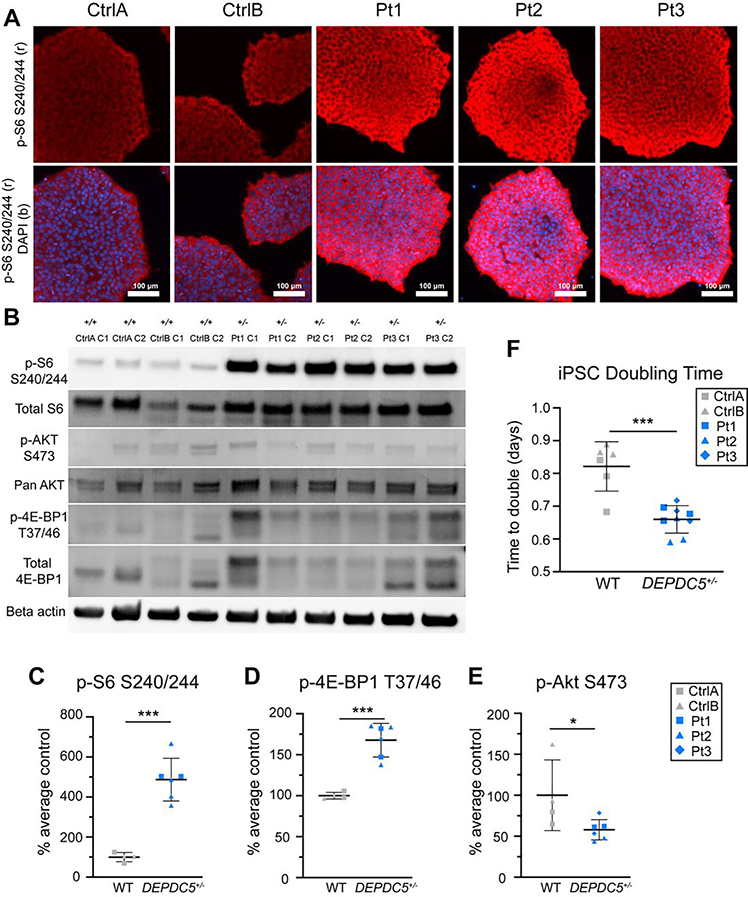

Knockdown of DEPDC5 has been associated with increased mTORC1 signaling activation, demonstrated by elevated phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6 (Iffland et al., 2018). Studies examining heterozygous mutations in TSC1 and TSC2, which are also upstream regulators of mTORC1, have reported variable results regarding dysregulation of mTOR signaling in iPSCs (Armstrong et al., 2017; Blair et al., 2018; Li et al., 2017; Winden et al., 2019). We hypothesized that haploinsufficiency of DEPDC5 caused by heterozygous inactivating mutations (DEPDC5+/−) would allow increased mTORC1 activity in patient-derived iPSCs. We first evaluated the phosphorylation of ribosomal S6 (Ser240/244), a downstream target of mTORC1, by immunofluorescence. DEPDC5+/− iPSCs demonstrated a uniformly increased p-S6 (S240/244) signal intensity when compared to control iPSCs (Fig. 2A), suggesting mTORC1 activity elevation. To further characterize mTOR signaling pathway activation in iPSCs, we measured phosphorylation of downstream targets of mTORC1 signaling, including ribosomal S6 (p-S6, mTORC1), 4E-BP1 (p-4E-BP1), and mTORC2 with AKT S473 (p-AKT) using protein immunoblotting (Fig. 2B). DEPDC5+/− iPSCs showed significantly increased ratios of p-S6 (S240/244)/total S6 and p-4E-BP1 (T37/46)/total 4E-BP1 compared to controls, indicating hyperactive mTORC1 signaling (Fig. 2C–D). p-AKT(S473)/total AKT ratio was variable between cell lines (Fig. 2E). Immunoblot data are provided for individual cell lines in Fig. S2A–C with all blots shown uncropped in Fig. S2F.

Figure 2. Elevated mTORC1 signaling in DEPDC5+/− patient iPSCs.

(A) Immunofluorescence images demonstrating p-S6 Ser240/244 (red) expression in control and DEPDC5+/− patient iPSCs with DAPI nuclear staining (blue). Scale bar = 100 μm. (B) Representative immunoblot of protein lysates from n=2 control and n=3 DEPDC5+/− patient iPSC lines (2 clones per line) evaluating mTOR signaling. Blots were cropped to show the relevant bands. Dots represent the average of 2–3 experimental replicates from different passages. Different symbols indicate different individuals, with each dot representing a unique clone. (C) Quantification of immunoblot results for p -S6 (Ser240/244) in iPSCs, p=.0001. (D) Quantification of immunoblot results for p-4E-BP1 (Thr37/46) in iPSCs, p=.0002. (E) Quantification of immunoblot results for p-AKT (Ser473) in iPSCs, p=.0494. (F) iPSC population doubling time during the logarithmic growth phase. n=3 experimental replicates per each cell line, each dot represents one replicate, p=.0001). Data were analyzed using unpaired t-tests. Bars represent mean ± SD. See Figure S2 for uncropped immunoblots and comparisons of individual control and patient cell lines.

Given the effects of mTORC1 activation on cellular proliferation, we assessed the growth rate of control and DEPDC5+/− iPSCs. We used cell counting assays to calculate population doubling time and found that heterozygous mutant DEPDC5 iPSCs had a more rapid doubling time compared to wild-type iPSCs, indicating a faster rate of growth (Fig. 2F, Fig. S2D). Treatment with rapamycin attenuated the growth rate (Fig. S2E). These data further support increased mTORC1 activation in iPSCs with heterozygous DEPDC5 mutations.

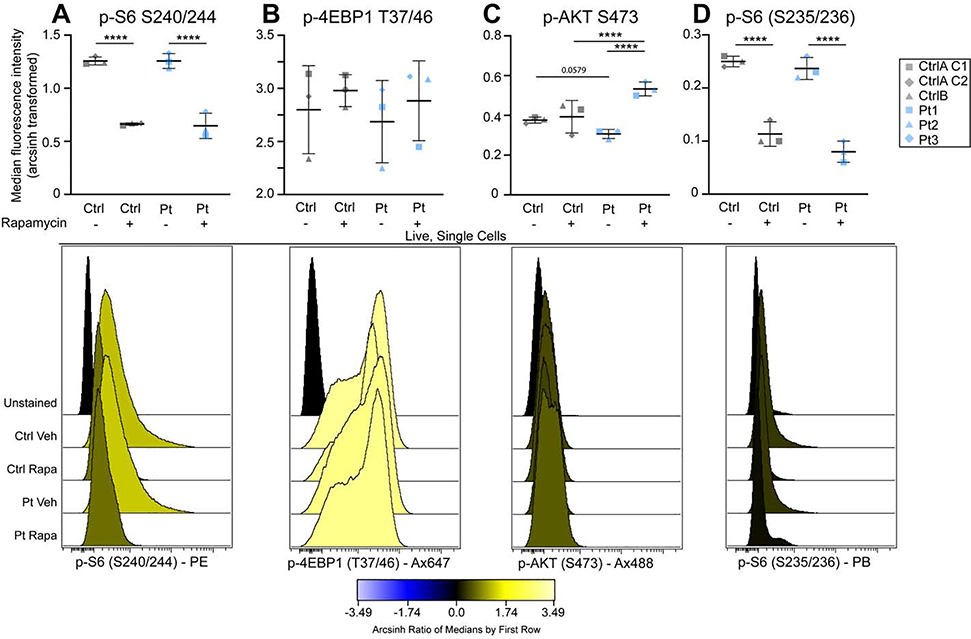

3.3. mTOR signaling in response to rapamycin differs in DEPDC5-mutant cells

To further characterize the phosphorylation events downstream of mTORC1 and mTORC2, cultured iPSCs were analyzed by flow cytometry (see Fig. S3A–B for experimental and gating strategy). Based on immunofluorescent staining results, we hypothesized that two populations of control iPSCs were present, comprising both low and high p-S6 (S240/244) intensity, as opposed to a single population of high p-S6 signal in DEPDC5+/− iPSCs. In contrast to the immunoblot results, no significant differences in phosphorylation status of the known mTORC1 targets p-S6 (S240/244) or p-4E-BP1 (T37/46), mTORC2 target p-AKT (S473), or p-S6 (S235/236) were detected in baseline conditions, although DEPDC5+/− iPSCs had a trend toward reduced p-AKT and significant variation existed in p-4E-BP1 (Fig. 3A–D). Following 24 hours of rapamycin treatment (20 nM), attenuation of the rapamycin-sensitive p-S6 signal occurred in patient and control lines, while there was no change in p-4E-BP1. DEPDC5+/− iPSCs also demonstrated increased p-AKT (S473) signal following rapamycin treatment compared to controls, which did not show changes in p-AKT after rapamycin.

Figure 3. Divergent responses to rapamycin and nutrient stimulation in DEPDC5+/− iPSCs.

Graphs and representative histograms of median fluorescence intensity, relative to unstained samples, of phosphorylated proteins measured by flow cytometry. (A-D) Scale indicates transformed arcsinh scale comparing intensity to unstained cells for each line. A difference of 0.4 on the arcsinh scale represents an approximately twofold difference in total phosphorylated epitope levels per cell. Each dot represents the median of three experimental replicates from a single individual. Histograms represent the median of control or DEPDC5+/− lines. Groups were compared using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons, with significant differences indicated by *p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001, ****p<.0001. All bars represent mean ± SD. See Figure S3 for gating strategy and biaxial plots.

Biaxial plots were generated to determine the relationship betweenp-S6 (S240/244) and p-4E-BP1 signals (Fig. S3C). The population of cells high for both p-4E-BP1 and p-S6 decreased following rapamycin treatment in both controls and patient-derived lines (Fig. S3D). However, the population of cells high in p-4E-BP1 but low for p-S6 increased in DEPDC5+/− lines following rapamycin treatment (Fig.S3E). This population of cells thus had attenuation in S6 phosphorylation in response to rapamycin but hyperphosphorylation of 4E-BP1. Biaxial plots were also generated to determine if 4E-BP1 phosphorylation correlated with AKT phosphorylation (Fig. S3F). Cells with high p-4E-BP1 signal in DEPDC5+/− lines following rapamycin treatment were generally also high for p-AKT, with DEPDC5+/− lines having a greater percentage of high p-4E-BP1/high p-AKT cells than controls (Fig. S3G). These data indicate that while the p-S6 signal in DEPDC5+/− iPSCs can be attenuated with rapamycin, DEPDC5+/− lines differ from controls in mTOR signaling pathway activation patterns after rapamycin treatment.

3.4. Cytomegaly and increased mTORC1 activation in DEPDC5-mutant neuroprogenitor cells

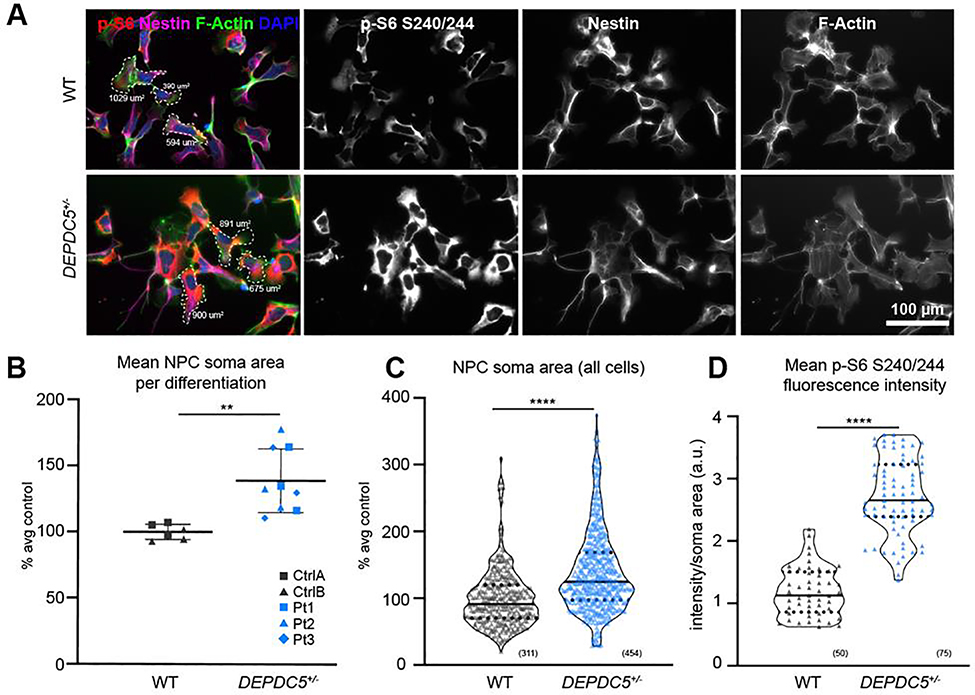

To investigate the hypothesis that DEPDC5 haploinsufficiency alters cell morphology and mTOR activation in human neural progenitor cells (NPCs), two control lines and three patient lines were used for neuronal differentiation experiments. iPSCs were differentiated toward a cortical neuronal fate by dual-SMAD inhibition based on modifications of the differentiation protocol initially described by Shi et al. (Fig. S4A) (Shi et al., 2012). iPSCs subjected to this differentiation protocol undergo a series of morphological changes (Fig. S4B), first going through a neuroepithelial sheet stage, a neural rosette stage, then forming post-mitotic neurons in a developmentally appropriate layer-specific manner. By day 16, nearly 100% of cells of both genotypes are dually positive for Pax6 and Nestin expression (Fig. S4C). Both control and DEPDC5+/− patient neurons generated greater than 80% neurons at day 60 (data not shown), based on β-III-Tubulin-positive cells analyzed by flow cytometry. We did not quantify neuronal proportions for each differentiation and instead relied on immunostaining to identify neuroprogenitor cells and neurons. Neurons generated by this protocol develop excitatory synapses, demonstrated by colocalization of Synapsin1 and PSD95, (Fig. S4D) and display electrical activity (Shi et al., 2012).

To determine if haploinsufficiency alters development of neuroprogenitor cells, we examined NPCs for cell size changes and differences in mTORC1 signaling (Fig. 4A). NPCs were defined as Pax6+/Nestin+ cells prior to the formation of neural rosettes (Fig. S4C) and were sparsely plated in order to identify individual cell borders. NPC soma size was measured by filamentous actin staining. The two control lines did not have significantly different NPC soma sizes from one another (Fig. S5A), however we found that DEPDC5+/− NPCs had larger soma areas than control cells (Fig. 4B–C). DEPDC5+/− NPCs also had higher intensity of p-S6 (S240/244) (Fig. 4D). Larger soma sizes and increased phospho-S6 intensity were consistently seen in all patient lines (Fig. S5B–D). These data indicate that DEPDC5 haploinsufficiency results in increased mTORC1 signaling and cell size during early neurodevelopment.

Figure 4. DEPDC5+/− patient neuroprogenitor cells (NPCs) are cytomegalic with increased mTORC1 signaling.

(A) Representative images of control and DEPDC5+/− patient NPCs (differentiation day 10) showing expression of p-S6 S240/244 (red), nestin (neuroprogenitor cells, magenta), F-actin (cytoskeleton, green), and DAPI (nuclei, blue). Representative cell size measurements identified with dashed border. (B) Plot of mean soma area in control (grey) or DEPDC5+/− patient (blue) neuroprogenitor cells. These plots represent data from two control clones and three patient clones, each with 3 separate differentiations. Each dot indicates an average of 50 cells counted per differentiation. Unpaired t-test, p=.002. (C) Violin plots of F-actin+ soma size of patient and control NPCs. Plots represent data from 311 control or 454 DEPDC5+/− cells pooled from 3 separate differentiation experiments. Mann-Whitney test, p<.0001. (D) Violin plot of p-S6 S240/244 fluorescence intensity divided by soma area in DEPDC5+/− and control NPCs. Data is pooled from three separate wells of one differentiation, 25 cells per line. Mann-Whitney test, p<.0001. For violin plots, solid line represents mean value and dotted lines represent 25th and 75th percentiles. See also Figure S4 and S5.

3.5. Cytomegaly in neurons heterozygous for DEPDC5 mutation is ameliorated by rapamycin

To determine if the cell size phenotype persisted as neurons developed, we examined early neurons following the rosette stage. Soma size of immature neurons was measured using neuron-specific microtubule-associated protein (MAP2), a protein expressed first in neural precursor cells with subsequent increased expression upon neuronal maturation (Dehmelt and Halpain, 2005). We found that cells at this stage are smaller than NPCs, though immature neurons haploinsufficient for DEPDC5 continued to demonstrate a larger cell size than control neurons (Fig. 5A).

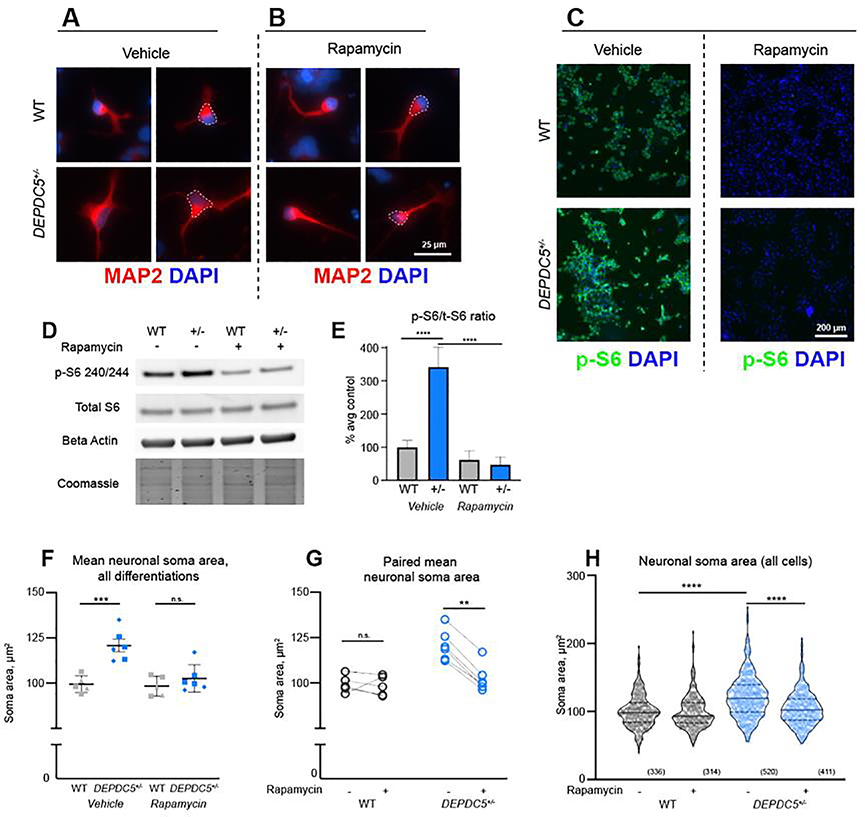

Figure 5. Cytomegalic DEPDC5+/− neurons are sensitive to mTORC1 inhibition.

(A, B) Neuronal cell size of MAP2+ (red) neurons following vehicle (A) orrapamycin( B) treatment, with DAPI nuclear staining (blue). ( C) Chronic treatment with 20 nM rapamycin throughout neuronal differentiation attenuates p-S6 S240/244 (green) expression in DEPDC5+/− and control neurons. (D) Representative protein immunoblots of lysates from control and DEPDC5+/− patient neurons. Blots were cropped to show the relevant bands. (E) Quantification of p-S6 S240/244 to total S6 ratio with and without rapamycin treatment. Data represent two control lines and one DEPDC5+/− line from two separate differentiations. Bars indicate mean ± SD. Groups were compared using two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons, p<.0001. (F) Plot of mean neuronal soma size of control (gray) and DEPDC5+/− (blue) early neurons with or without chronic treatment with 20 nM rapamycin. These plots represent data from two control clones and two patient clones, each with 2–3 separate differentiations. Each dot indicates an average of 50 cells counted per differentiation. Groups were compared using two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons, p=.0001. (G) Paired plots of mean neuronal soma size. Each pair of points represents the mean soma size of a single differentiation with or without rapamycin. Groups were compared using paired t -tests: WT veh vs. rapa, p=.7157; DEPDC5+/− veh vs. rapa, p<.0001. (H) Violin plots of control (gray) and DEPDC5+/(blue) early neuronal soma size; plots represent data from 336 WT-veh, 314 WT-rapa, 520 DEPDC5+/−-veh, and 411 DEPDC5+/−-rapa cells pooled from 2–3 separate differentiation experiments. Solid line represents mean value and dotted lines represent 25th and 75th percentiles. Groups were compared using two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons. See Figure S6 for soma areas of each cell line and uncropped immunoblots.

To confirm that the changes in neuronal size were due to increased mTORC1 activity, rapamycin or vehicle was added to culture media on day 1 of differentiation and continued until cells were fixed for analysis at day 21 (Fig. 5A–B, Fig. S6A). Rapamycin was sufficient to attenuate p-S6 (S240/244) intensity in both wild-type control and DEPDC5 haploinsufficient neurons (Fig. 5C). This finding was confirmed with immunoblot (Fig. 5D–E, Fig. S6D). Rapamycin treatment decreased soma size of DEPDC5+/− neurons to a level comparable to controls (Fig. 5F–H, Fig. S6B–C). The size of control neurons was not significantly altered by treatment with rapamycin. Altogether, these data indicate that the increase in neuronal soma size upon heterozygous DEPDC5 mutation can be prevented by inhibition of mTORC1. However, the addition of long-term rapamycin did impair the percentage of cells that survived the neuronal differentiation in both control and DEPDC5+/− cell lines.

3.6. Cytomegaly persists in post-mitotic neurons heterozygous for DEPDC5 mutation

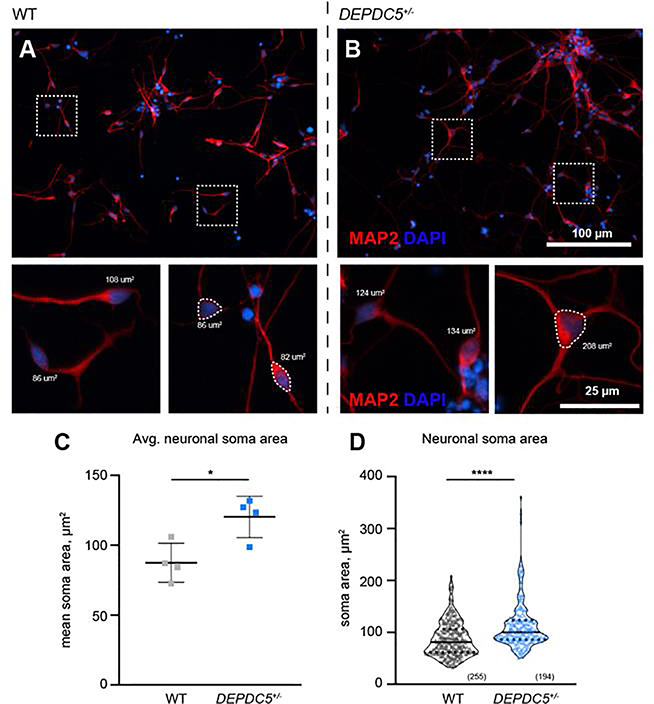

Since each DEPDC5+/− patient line displayed both increased mTORC1 signaling and increased cell size in NPCs and immature neurons, we selected one set of patient clones (Pt1) for the evaluation of mature neuronal morphology. To address cell autonomous phenotypes and limit possible confounding effects of glia, we focused on post-mitotic neurons (after day 65 of differentiation) prior to the emergence of significant glial populations (Shi et al., 2012). Both control and DEPDC5+/− lines formed β-tubulin-III+/MAP2+ neurons with well-defined neuronal processes (Fig. 6A–B, data not shown). The increase in soma size first seen in NPCs persisted in post-mitotic neurons with DEPDC5 heterozygous mutant neurons demonstrating significantly larger MAP2-positive soma sizes than control neurons (Fig. 6C–D). These findings support that DEPDC5 haploinsufficiency results in dysregulated and increased mTORC1 activity throughout neuronal development.

Figure 6. Post-mitotic neurons haploinsufficient for DEPDC5 continue to display larger cell size.

(A-B) Neuronal soma size of post-mitotic neurons identified with immunocytochemistry for MAP2 (red) in control (A) and DEPDC5+/− patient (B) neurons, with DAPI nuclear staining (blue). Representative cell size measurements identified with dashed border. (C) Mean neuronal soma size of patient and control neurons. Each dot represents the mean soma size of a separate differentiation; 1–3 differentiations per clone; n=2 clones per genotype; at least 25 cells per differentiation were counted. Unpaired t-test, p=.0179. Bars represent mean ± SD. (D) Violin plots of neuronal soma size of wild-type and DEPDC5+/patient neurons. Plots represent data from 255 control or 194 DEPDC5+/− cells pooled from separate differentiation experiments. Mann-Whitney test, p<.0001. Solid line represents mean value and dotted lines represent 25th and 75th percentiles.

3.7. Post-mitotic neurons have elevated mTORC1 activity that persists after amino acid deprivation

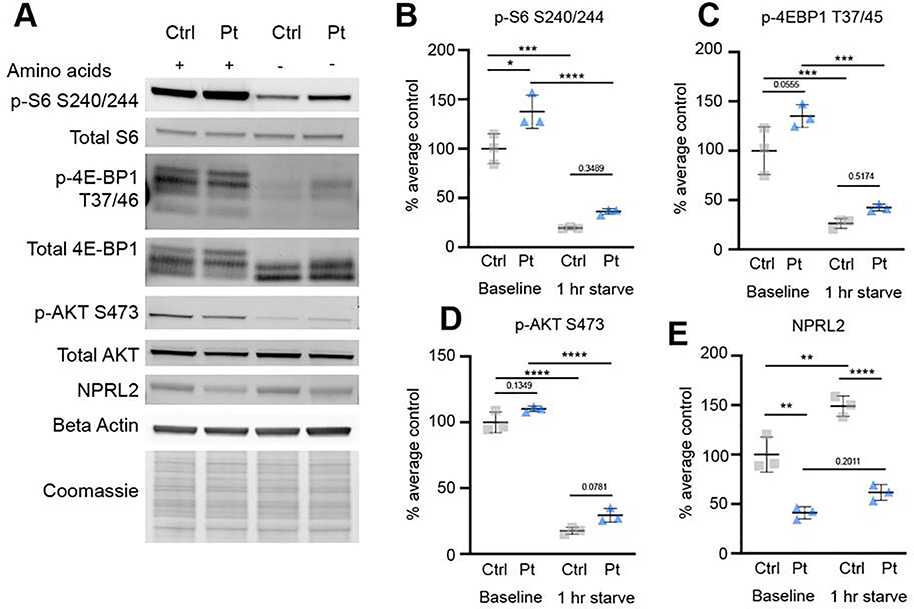

To confirm that elevated mTORC1 signaling persisted in mature neurons, we performed protein immunoblots to evaluate markers of mTOR pathway activation (Fig. 7A, Fig. S7A). Similar to the findings in NPC and immature neurons, S6 phosphorylation (S240/244) was elevated in older DEPDC5+/− neurons (Fig. 7B). Statistically significant differences in p-4E-BP1 or p-AKT were not detected, although there was a trend toward increased p-4E-BP1 (Fig. 7C–D).

Figure 7. DEPDC5+/− neurons have elevated mTORC1 activity at baseline but remain sensitive to starvation.

(A) Representative protein immunoblots of lysates from control and DEPDC5+/− patient neurons probed for markers of mTOR signaling and NPRL2. Western blots were cropped to show the relevant bands. (B) Quantification of immunoblot results for p-S6 (Ser240/244). (D) Quantification of immunoblot results for p-4E-BP1 (Thr37/46). (E) Quantification of immunoblot results for p-AKT (Ser473). (E) Quantification of NPRL2. Groups were compared using two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001. Each dot represents a biological replicate. See also Figure S7.

Because the GATOR1 complex functions as part of the nutrient-sensing arm of the mTOR signaling pathway, we hypothesized that DEPDC5+/− neurons may have an impaired response to nutrient starvation, a response which would ordinarily suppress mTOR activity (Bar-Peled et al., 2013; Wolfson and Sabatini, 2017). GATOR1 knockdown has previously been shown to result in an inappropriate persistence of mTORC1 activation in response to amino acid deprivation in transformed human cell lines and in homozygous, but not heterozygous, Depdc5-mutant rodent embryonic fibroblasts (Hughes et al., 2017;Iffland et al., 2018;Marsan et al., 2016). In patient neurons, one hour of amino acid deprivation. resulted in decreased S6 phosphorylation in all lines, but p-S6 expression trended toward persistent elevation in DEPDC5+/− neurons versus controls. By two hours of amino acid deprivation, p-S6 expression was further reduced in all lines (Fig. S7B).

As noted above, DEPDC5 is a constituent of the GATOR1 complex that also includes nitrogen permease regulator-like 2 and 3(NPRL2 and NPRL3). Loss of DEPDC5 has been shown to result in decreased levels of NPRL2 in animal models, but not when DEPDC5 mutants are transfected in human cells (van Kranenburg et al., 2015; Yuskaitis et al., 2019). Given the role of NPRL2 as the catalytic subunit responsible for the GTPase-activating protein (GAP) function of the GATOR1 complex toward RagA/B, which prevents recruitment of mTORC1 to the lysosome when GDP-bound, we sought to determine the extent to which heterozygous loss of DEPDC5 altered NPRL2 expression (Shen et al., 2019). Quantitation of NPRL2 expression by immunoblot demonstrated decreased expression in patient lines with heterozygous DEPDC5 mutation in both iPSCs and neurons (Fig.7E, Fig.S7C). Furthermore, while control neurons showed a significant elevation in NPRL2 after one hour of starvation, DEPDC5heterozygous mutant lines did not show a similar increase in NPRL2.

4. Discussion

Mutations in the component proteins of the GATOR1 complex (DEPDC5, NPRL2, and NPRL3) are increasingly appreciated as causes of focal epilepsies. In epilepsies with focal cortical dysplasia (FCD), accumulating evidence suggests that acquisition of a second-hit drives pathogenesis. For these epilepsies and for the majority of DEPDC5-related epilepsies without FCD, it is not known whether other mechanisms may lead to or contribute to epilepsy. Specifically, the consequences of a heterozygous mutation in DEPDC5 have not been characterized in a human model. To better understand the effects of DEPDC5 haploinsufficiency in humans, we generated iPSCs and neurons from epilepsy patients with inactivating mutations in DEPDC5 but without evidence of FCD. We found that heterozygous mutations in DEPDC5 allow increased mTORC1 signaling activity in iPSCs and derivative neurons. Corresponding increases in neuronal size were responsive to chronic treatment with rapamycin. These results reveal a potential role for DEPDC5 haploinsufficiency in contributing to neuronal dysfunction by driving increased mTORC1 signaling.

A major finding of our study is the presence of a mTORC1-hyperactivation phenotype in cells heterozygous for DEPDC5. We analyzed mTORC1 activation using a variety of methods and found increased phosphorylation of the mTORC1 targets S6 (S240/244) and 4E-BP1 (T37/46) in DEPDC5+/− patient lines via immunofluorescence and immunoblot. The magnitude of increased mTORC1 activation was substantially greater in DEPDC5+/− iPSCs than in DEPDC5+/neurons, which could reflect cell-type specific differences in signaling activation. DEPDC5+/patient iPSC lines had a faster rate of cell growth consistent with increased mTORC1 activity. DEPDC5+/− iPSCs also showed decreased p-AKT (S473), which is consistent with the well-described compensatory feedback in mTORC2 activity (reviewed in Rozengurt et al., 2013). However, significant variation in p-AKT existed between control iPSC lines by immunoblot, potentially due to relatively low basal expression of p-AKT/AKT in iPSCs combined with variable activity of other upstream mediators of PI3K/AKT signaling (Hossini et al., 2016; Fruman et al., 2017).

We also analyzed mTOR activation in iPSCs by flow cytometry. Due to the contrasting methods of sample preparation for flow cytometry and immunoblotting, differing modes of signaling may be detected. For immunoblots, cells are lysed directly in the wells with phosphatase inhibitors allowing for preservation of the state of the cell. However, for flow cytometry, cells are by necessity dissociated to single cells, then allowed to equilibrate for an hour. Dissociation of cells prior to analysis creates the potential to alter signaling dynamics in the cell. By both techniques, we observed a trend toward decreased p-AKT in DEPDC5+/iPSCs, while the extent of phosphorylation of S6 and 4E-BP1 diverged between the two methods. DEPDC5+/− iPSCs treated with 24 hours of rapamycin and analyzed by flow cytometry recapitulated known differences in susceptibility of downstream mTORC1 targets to inhibition by rapamycin (Thoreen et al., 2009). Specifically, p-S6 was robustly inhibited by rapamycin, whereas p-4E-BP1 had a variable response consistent with its known role in mediating some of the rapamycin-resistant functions of mTORC1 (Choo et al., 2008).

DEPDC5+/− iPSCs also demonstrated higher levels of p-AKT S473 after rapamycin treatment. Taken together with the baseline trend toward decreased p-AKT seen by immunoblot and flow cytometry, this further supports that p-AKT S473 is repressed by mTORC1 to a greater extent in DEPDC5+/− iPSCs, an effect that is relieved with rapamycin. However, this result is tempered by the variability of p-AKT as assessed by immunoblots. Phosphorylation of AKT is regulated indirectly by mTORC1 through feedback on mTORC2, in addition to other inputs through PI3K signaling, and differences in these additional upstream mediators may be responsible for the p-AKT variability (Manning and Toker, 2017; Fruman et al., 2017 ). Collectively, these approaches support increased mTORC1 activation in DEPDC5+/− iPSCs, most specifically assessed by measuring p-S6 S240/244 expression (Roux et al., 2007; Hutchinson et al., 2011). Future studies may examine whether the changes observed via immunoblot are due to subpopulations of cells with high mTORC1 activation or an more generalized increase in overall mTORC1 activation in all cells.

The finding of increased mTORC1 activation and resultant increased soma size in neurons heterozygous for DEPDC5 mutations was surprising given that no heterozygous phenotype has been observed in existing Depdc5 mouse models (Hughes et al., 2017; Yuskaitis et al., 2018). Interestingly, increased neuronal size was noted in a heterozygous rat model, suggesting that species-specific differences may influence the effects of the heterozygous state (Marsan et al., 2016). However, all described heterozygous models seem to retain sensitivity to nutrient-starvation, including our iPSC-derived neurons. DEPDC5+/− neurons attenuated p-S6 S240/244 after nutrient starvation to a significant extent compared to their baseline, although DEPDC5+/− neurons trended toward higher p-S6 S240/244 than controls after nutrient starvation, an effect that may prove to be statistically significant with a larger sample size. This is in opposition to cells with complete loss of DEPDC5, which show near-complete insensitivity to nutrient starvation (Bar-Peled et al., 2013; Hughes et al., 2017; Marsan et al., 2016). The subunit of the GATOR1 complex with GA). activity for RagA/B, NPRL2, is decreased in DEPDC5+/− neurons to half that of controls. Our results thus suggest that this decreased level of NPRL2 is sufficient for the response to nutrient deprivation. This is consistent witha study identifying the catalytic residue of NPRL2, which showed that even low concentrations of GATOR1 were sufficient to significantly accelerate GTP hydrolysis by the Rags (Shen et al, 2019). Heterozygous cells thus retain some ability to sense changes in nutrient conditions. The functional relevance of a potential defect in nutrient-sensing remains to be determined. However, from these data, it seems likely that not all mTORC1 functions are equally affected by DEPDC5 heterozygosity. Even though DEPDC5+/− neurons remained somewhat sensitive to starvation, they had elevated mTORC1 activity at baseline, which is likely responsible for driving the increased neuronal size.

Our findings of mTORC1-dependent cell size differences in neuroprogenitor cells (NPCs) and neurons suggest possible mechanisms by which heterozygous DEPDC5 mutation may contribute to the pathogenesis of epilepsy. The persistence of cytomegaly in DEPDC5+/neurons may have functional significance with respect to epilepsy. As a result of the larger soma size, heterozygous neurons are likely to have an increased membrane capacitance and may respond differently than wild-type neurons to action potentials and aberrant electrical activity. While we describe a model of DEPDC5 haploinsufficiency resulting in abnormal cell signaling, growth, and morphology, evidence is accumulating to support the requirement of a “second hit” for the development of FCD. Our data presented here do not address how a second mutation would impact specific neurons or the surrounding heterozygous neuronal population, but this model does provide a framework for further studies incorporating detailed electrophysiologic analysis.

While iPSC technology offers a unique opportunity to study DEPDC5 haploinsufficiency in human neurons, our model does have some caveats. One is the potential for genetic variability in unaffected control lines. To control for this, one of our control lines (Control B) was generated from the healthy parent of one of the epilepsy patients (Patient 2). The control lines used in the study displayed significantly different patterns of mTORC1 signaling from DEPDC5+/patient lines. Patient lines comparatively displayed increased mTORC1 activation and resultant increased cell size; however, a larger set of unaffected control samples would be useful to further control for the inherent genetic variability present in unrelated individuals. Additionally, for future studies, the application of CRISPR-Cas9 genomic editing to create matched sets of isogenic control, heterozygous, and homozygous cell lines represents an ideal strategy to definitively isolate the effects of DEPDC5 gene dosage.

Due to a lack of availability of a specific DEPDC5 antibody, we were limited in our evaluation of DEPDC5 protein expression and instead evaluated mRNA levels as a proxy to assess for functionally relevant changes resulting from DEPDC5 mutations. While the results of the rapamycin rescue experiments support the conclusion that increased neuronal size is dependent on mTORC1 activation, translating these results to patient care requires caution. Although treatment of cells with rapamycin throughout the entire differentiation rescued the cytomegalic phenotype, it also somewhat impaired the survival of cells throughout the neuronal differentiation process, both in control and DEPDC5+/− patient cell lines. Because of this and the possibility of other effects of long-term rapamycin treatment (reviewed in Tran and Zupanc, 2015), prolonged rapamycin treatment during neurodevelopment is unlikely to be clinically feasible. Future experiments exploring the potential efficacy of targeted treatment windows of mTORC1 suppression to modulate the disease phenotype will be valuable.

The findings from the flow cytometry studies are limited by their lack of concordance with our findings via immunoblot. Additionally, p-4E-BP1 was evaluated to reinforce the findings seen using p-S6, which is a more specific mTORC1 target (Roux et al., 2007; Hutchinson et al., 2011). The antibody we used for immunoblotting detects multiple bands of mTORC1-mediated 4E-BP1 phosphorylation, which could be considered a limitation. Multiple phosphorylation states exist for 4E-BP1, with an initial priming step mediated by mTORC1 on T37 and T46 that then allows subsequent C-terminal phosphorylation events to occur (Gingras et al., 2001; Qin et al., 2016; Gingras et al., 1999). The predominance of the higher molecular weight band in the patient samples is most consistent with the doubly phosphorylated 4EBP1 at T37 and T46. Given that this antibody does not discriminate them TORC1 phosphorylation sites from one another, we included them all in the quantitation. The inability to discriminate between these different mTORC1-mediated phosphorylation states using this immunoblot technique could be considered a limitation. Overall, the findings of increased p-4E-BP1 expression in DEPDC5+/cells agree with the findings of increased p-S6 expression (S240/244), supporting increased mTORC1 activation.

In our study, we chose to evaluate two iPSC clones per line for initial experiments in iPSCs to ensure the reproducibility of our findings. Some have argued that treating iPSC clones from the same patient as biological replicates without statistically accounting for the interdependence of the clones can produce spurious results in transcriptomic analysis (Germain & Testa, 2017). At the same time, it is important to confirm that effects are consistent in patient-derived cells and not due to potential genetic changes present in a single clone. In subsequent neuronal differentiations, one clone per individual was used to balance the potential for spurious findings with the cost and throughput limitations inherent in extended iPSC differentiation timelines. Overall, our findings consistently show evidence of mTORC1 activation in iPSCs, NPCs, and neurons, and increased cell size in NPCs and neurons.

Future studies explicitly focused on the evaluation of changes in the electrical activity of human neurons with DEPDC5 mutations will be essential. Studies that combine neurons with both heterozygous and homozygous DEPDC5 mutations as well as glia will further provide invaluable information on network effects and the contributions of heterozygous mutant neurons to epilepsy. As such, determination of the contributions of different central nervous system cell types and their interactions remains vital. Non-cell-autonomous interactions between various cell types may contribute to disease, as has recently been demonstrated in cultures of variably TSC-mutant neurons and oligodendrocytes (Nadadhur et al., 2019). Mixed neuronal and glial cultures, ideally in three-dimensional cerebral organoids or “brain-on-a-chip” culture systems, will be particularly relevant Journal tosuchstudies. Our iPSC-derived neuronal model can also be utilized to confirm the characterization of potentially-pathogenic DEPDC5 variants such as that by Dawson et al. (2020). Overall, iPSC-derived neurons and cortical organoids provide a unique milieu in which to study the impact of genetic alterations on neurobiology and disease pathogenesis in the human brain.

5. Conclusion

In summary, we differentiated neurons from iPSCs generated from three patients with epilepsy due to loss-of-function mutations in DEPDC5 in order to determine if DEPDC5 haploinsufficiency contributes to epilepsy pathology in a human disease model. We found that loss-of-function of one allele of DEPDC5 is sufficient to cause increased mTORC1 signaling in iPSCs and neurons as well as development of cytomegalic neuroprogenitor cells and neurons. These results suggest that germline haploinsufficiency may play a role in the pathogenesis of epilepsy with DEPDC5 mutation. Our findings suggest that human disease may differ from rodent models, which do not consistently show differences in heterozygous Depdc5-mutant neurons. These findings support the need for human-based models to expand and verify discoveries in animal models of DEPDC5 mutations and epilepsy.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

iPSCs were generated from epilepsy patients harboring mutations in DEPDC5

DEPDC5+/− iPSCs and neurons showed mTORC1 hyperactivation and reduced NPRL2 protein

DEPDC5+/− neurons had enlarged somas, a phenotype rescued with mTORC1 inhibition

DEPDC5 haploinsufficiency may contribute to disease by driving increased mTORC1 signaling

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the thoughtful comments on this manuscript from Dr. Cary Fu and Dr. Krystian Kozek. The content herein is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors had no conflicts of interest to declare related to this work.

Funding sources:

This work was supported Jo by National Institutes of Health grants NS083710, TR002097-03, and NS096238. L.K.K. and J.P.S. were supported by training grant T32-GM007347, J.S. by training grant T32- HD007502, and G.V.R. by training grant 2T32-CA009592 and predoctoral fellowship F31-NS096908. R.A.I. was also supported by the CDMRP/DOD grant TS-150037, the Michael David Greene Brain Cancer Fund, a VICC Ambassadors award, and the Southeastern Brain Tumor Foundation. The VUMC Flow Cytometry Shared Resource is supported by the Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center (P30-CA68485) and the Vanderbilt Digestive Disease Research Center (DK058404).

Abbreviations

- DEPDC5

DEP domain-containing protein 5

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- FCD

focal cortical dysplasia

- FGF2

fibroblast growth factor 2

- GAP

GTPase activating protein

- GATOR1

GAP activity toward Rags

- iPSC

induced pluripotent stem cell

- mTOR

mechanistic target of rapamycin

- mTORC1

mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1

- NPRL2

nitrogen permease regulator-like 2

- NPRL3

nitrogen permease regulator-like 3

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PFA

paraformaldehyde

- p-4E-BP1

phosphorylated eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E (eIF4E)-binding protein 1

- p-AKT

phosphorylated AKT

- p-S6

phosphorylated S6 ribosomal protein

- TSC

tuberous sclerosis complex

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Armstrong LC, Westlake G, Snow JP, Cawthon B, Armour E, Bowman AB, and Ess KC (2017). Heterozygous loss of TSC2 alters p53 signaling and human stem cell reprogramming. Hum. Mol. Genet. 26, 4629–4641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldassari S, Licchetta L, Tinuper P, Bisulli F, and Pippucci T(2016). GATOR1 complex: the common genetic actor in focal epilepsies. I. Med. Genet. 53, 503–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldassari S, Picard F, Verbeek NE, vanKempen M, Brilstra EH, Lesca G, Conti V, Guerrini R, Bisulli F, Licchetta L, et al. (2019a). The landscape of epilepsy-related GATOR1 variants. Genet. Med. 21, 398–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldassari S, Ribierre T, Marsan E, Adle-Biassette H, Ferrand-Sorbets S, Bulteau C, Dorison N, Fohlen M, Polivka M, Weckhuysen S, et al. (2019b). Dissecting the genetic basis of focal cortical dysplasia: a large cohort study. Acta Neuropathol. 21, 92–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Peled L, Chantranupong L, Cherniack AD, Chen WW, Ottina KA, Grabiner BC, Spear ED, Carter SL, Meyerson M, and Sabatini DM (2013). A Tumor suppressor complex with GAP activity for the Rag GTPases that signal amino acid sufficiency to mTORC1. Science 340, 1100–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baulac S, Ishida S, Marsan E, Miquel C, Biraben A, Nguyen DK, Nordli D, Cossette P, Nguyen S, Lambrecq V, et al. (2015). Familial focal epilepsy with focal cortical dysplasia due to DEPDC5 mutations. Annals of Neurology 77, 675–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair JD, Hockemeyer D, and Bateup HS (2018). Genetically engineered human cortical spheroid models of tuberous sclerosis. Nat. Med. 24, 1568–1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Brodie MJ, Liew D, and Kwan P (2018). Treatment Outcomes in Patients With Newly Diagnosed Epilepsy Treated With Established and New Antiepileptic Drugs: A 30-Year Longitudinal Cohort Study. JAMA Neurol. 75, 279–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choo AY, Yoon S, Kim SG, Roux PP, and Blenis J (2008). Rapamycin differentially inhibits S6Ks and 4E-BP1 to mediate cell-type-specific repression of mRNA translation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105, 17414–17419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crino PB(2015). Focal Cortical Dysplasia. Semin. Neurol. 35, 201–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Gama AM, Geng Y, Couto JA, Martin B, Boyle EA, LaCoursiere CM, Hossain A, Hatem NE, Barry BJ, Kwiatkowski DJ, et al. (2015). Mammalian target of rapamycin pathway mutations cause hemimegalencephaly and focal cortical dysplasia. Annals of Neurology 77, 720–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Gama AM, Woodworth MB, Hossain AA, Bizzotto S, Hatem NE, LaCoursiere CM, Najm I, Ying Z, Yang E, Barkovich AJ, et al. (2017). Somatic Mutations Activating the mTOR Pathway in Dorsal Telencephalic Progenitors Cause a Continuum of Cortical Dysplasias. Cell Reports 21, 3754–3766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson RE, Nieto Guil AF, Robertson LJ, Piltz SG, Hughes JN, and Thomas PQ. (2020). Functional screening of GATOR1 complex variants reveals a role for mTORC1 deregulation in FCD and focal epilepsy. Neurobiol. Dis. 134, 104640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Fusco A, Cerullo MS, Marte A, Michetti C, Romei A, Castroflorio E, Baulac S, and Benfenati F, et al. (2020). Acute knockdown of Depdc5 leads to synaptic defects in mTOR-related epileptogenesis. Neurobiol, Dis. 139, 104822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehmelt L, and Halpain S (2005). The MAP2/Tau family of microtubule-associated proteins. Genome Biol. 6, 204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibbens LM, de Vries B, Donatello S, Heron SE, Hodgson BL, Chintawar S, Crompton DE, Hughes JN, Bellows ST, Klein KM, et al. (2013). Mutations in DEPDC5 cause familial focal epilepsy with variable foci. Nat. Genet. 45, 546–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruman DA, Chiu H, Hopkins BD, Bagrodia S, Cantley LC, Abraham RT (2017) The PI3K pathway in human disease. Cell 170, 605–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain PL, and Testa G (2017). Taming Human Genetic Variability: Transcriptomic Meta-Analysis Guides the Experimental Design and Interpretation of iPSC-Based Disease Modeling. Stem Cell Rep. 8, 1784–1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingras A, Gygi SP, Raught B, Polakiewicz RD, Abraham RT, Hoekstra MF, Aebersold R, Sonenberg N (1999). Regulation of 4E-BP1 phosphorylation: a novel two-step mechanism. GenesDev. 13, 1422–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingras AC, Raught B, Gygi SP, Niedzwiecka A, Miron M, Burley SK, Polakiewicz RD, Wyslouch-Cieszynska A, Aebersold R, Sonenberg N (2001) Hierarchical phosphorylation of the translation inhibitor 4E-BP1. Genes Dev. 15, 2852–2864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossini AM, Quast AS, Plötz M, Grauel K, Exner T, Küchler J, Stachelscheid H, Eberle J, Rabien A, Makrantonaki E, & Zouboulis CC (2016). PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathway Is Essential for Survival of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. PloS one, 11(5), e0154770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S, Knowlton RC, Watson BO, Glanowska KM, Murphy GG, Parent JM, and Wang Y (2018). Somatic Depdc5 deletion recapitulates electroclinical features of human focal cortical dysplasia type IIA. Annals of Neurology 84, 140–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes J, Dawson R, Tea M, McAninch D, Piltz S, Jackson D, Stewart L, Ricos MG, Dibbens LM, Harvey NL, et al. (2017). Knockout of the epilepsy gene Depdc5 in mice causes severe embryonic dysmorphology with hyperactivity of mTORC1 signalling. Scientific Reports 2017 7:1 7, 12618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson JA, Shanware NP, Chang H, Tibbetts RS(2011). Regulation of ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation by casein kinase1 and protein phosphatase 1. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 8688–8696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iffland PH, Baybis M, Barnes AE, Leventer RJ, Lockhart PJ, and Crino PB (2018). DEPDC5 and NPRL3 modulate cell size, filopodial outgrowth, and localization of mTOR in neural progenitor cells and neurons. Neurobiol. Dis. 114, 184–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irish JM, Myklebust JH, Alizadeh AA, Houot R, Sharman JP, Czerwinski DK, Nolan GP, and Levy R(2010). B-cell signaling networks reveal a negative prognostic human lymphoma cell subset that emerges during tumor progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107, 12747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida S, Picard F, Rudolf G, Noé E, Achaz G, Thomas P, Genton P, Mundwiller E, Wolff M, Marescaux C, et al. (2013). Mutations of DEPDC5 cause autosomal dominant focal epilepsies. Nat. Genet. 45, 552–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur A (2013). Novel DEPDC5 mutations causing familial focal epilepsy with variable foci identified. Clin. Genet. 84, 341–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klofas LK, Short BP, Zhou C, Carson RP (2020) Prevention of premature death and seizures in a Depdc5 mouse epilepsy model through inhibition of mTORC1. Hum. Mol. Genet. ddaa068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotecha N, Krutzik PO, and Irish JM(2010). Web-Based Analysis and Publication of Flow Cytometry Experiments. Current Protocols in Cytometry 53, 10.17.1–10.17.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal D, Reinthaler EM, Schubert J, Muhle H, Riesch E, Kluger G, Jabbari K, Kawalia A, Bäumel C, Holthausen H, et al. (2014). DEPDC5 mutations in genetic focal epilepsies of childhood. Annals of Neurology 75, 788–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WS, Stephenson SEM, Howell KB, Pope K, Gillies G, Wray A, Maixner W, Mandelstam SA, Berkovic SF, Scheffer IE, et al. (2019). Second-hit DEPDC5 mutation is limited to dysmorphic neurons in cortical dysplasia type IIA. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 6, 1338–1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Yu JSL, Tilgner K, Ong SH, Koike-Yusa H, and Yusa K(2018). Genome-wide CRISPR-KO Screen Uncovers mTORC1-Mediated Gsk3 Regulation in Naive Pluripotency Maintenance and Dissolution. Cell Reports 24, 489–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Cao J, Chen M, Li J, Sun Y, Zhang Y, Zhu Y, Wang L, and Zhang C(2017). Abnormal Neural Progenitor Cells Differentiated from Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells Partially Mimicked Development of TSC2 Neurological Abnormalities. Stem Cell Reports 8, 883–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton JO, and Sahin M(2014). The Neurology of mTOR. Neuron 84, 275–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, and Schmittgen TD (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using realtime quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25, 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manifava M, Smith M, Rotondo S, Walker S, Niewczas I, Zoncu R, Clark J, and Ktistakis NT (2016). Dynamics of mTORC1 activation in response to amino acids. Elife 5, 142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning BD, and Toker A(2017). AKT/PKB Signaling: Navigating the Network. Cell 169, 381–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsan E, Ishida S, Schramm A, Weckhuysen S, Muraca G, Lecas S, Liang N, Treins C, Pende M, Roussel D, et al. (2016). Depdc5 knockout rat: A novel model of mTORopathy. Neurobiol. Dis. 89, 180–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C, Meloche C, Rioux MF,Nguyen DK,Carmant L, Andermann E, Gravel M, and Cossette P (2014). A recurrent mutation in DEPDC5 predisposes to focal epilepsies in the French-Canadian population. Clin. Genet. 86, 570–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadadhur AG, Alsaqati M, Gasparotto L, Cornelissen-Steijger P, vanHugte E, Dooves S, Harwood AJ, and Heine VM (2019). Neuron-Glia Interactions Increase Neuronal Phenotypes in Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Patient iPSC-Derived Models. Stem Cell Reports 12, 42–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okita K, Matsumura Y, Sato Y, Okada A, Morizane A, Okamoto S, Hong H, Nakagawa M, Tanabe K, Tezuka K -I., et al. (2011). A more efficient method to generate integration-free human iPS cells. Nat. Methods 8, 409–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard F, Makrythanasis P, Navarro V, Ishida S, de Bellescize J, Ville D, Weckhuysen S, Fosselle E, Suls A, De Jonghe P, et al. (2014). DEPDC5 mutations in families presenting as autosomal dominant nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy. Neurology 82, 21012106–21012106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin X, Jiang B, & Zhang Y (2016). 4E-BP1, a multifactor regulated multifunctional protein. Cell Cycle 15, 781–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribierre T, Deleuze C, Bacq A, Baldassari S, Marsan E, Chipaux M, Muraca G, Roussel D, Navarro V, Leguern E, et al. (2018). Second-hit mosaic mutation in mTORC1 repressor DEPDC5 causes focal cortical dysplasia-associated epilepsy. J. Clin. Invest. 128, 2452–2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux PP, Shahbazian D, Vu H, Holz MK, Cohen MS, Taunton J, Sonenberg N, Blenis J (2007). RAS/ERK signaling promotes site-specific ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation via RSK and stimulates cap-dependent translation. J. Biol.Chem. 282, 14056–14064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozengurt E, Soares H, and Sinnet-Smith J (2014). Suppression of feedback loops mediated by PI3K/mTOR induces multiple overactivation of compensatory pathways: an unintended consequence leading to drug resistance. Mol. Cancer. Ther. 13, 2477–2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushing GV, Brockman AA, Bollig MK, Leelatian N, Mobley BC, Irish JM, Ess KC, Fu C, and Ihrie RA (2019). Location-dependent maintenance of intrinsic susceptibility to mTORC1-driven tumorigenesis. Life Sci. Alliance 2, e201800218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton RA, and Sabatini DM (2017). mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. Cell 169, 361–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scerri T, Riseley JR, Gillies G, Pope K, Burgess R, Mandelstam SA, Dibbens L, Chow CW, Maixner W, Harvey AS, et al. (2015). Familial cortical dysplasia type IIA caused by a germline mutation in DEPDC5. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2, 575–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffer IE, Heron SE, Regan BM, Mandelstam S, Crompton DE, Hodgson BL, Licchetta L, Provini F, Bisulli F, Vadlamudi L, Gecz J, Connelly A, Tinuper P, Ricos MG, Berkovic SF, and Dibbens LM (2014). Mutations in mammalian target of rapamycin regulator DEPDC5 cause focal epilepsy with brain malformations. Ann Neurol 75, 782–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen K, Huang RK, Brignole EJ, Condon KJ, Valenstein ML, Chantranupong L, Bomaliyamu A, Choe A, Hong C, Yu Z, et al. (2018). Architecture of the human GATOR1 and GATOR1-Rag GTPases complexes. Nature 556, 64–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen K, Valenstein ML, Gu X, and Sabatini DM (2019). Arg-78 of Nprl2 catalyzes GATOR1-stimulated GTP hydrolysis by the Rag GTPases. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 2970–2975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Kirwan P, and Livesey FJ (2012). Directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells to cerebral cortex neurons and neural networks. Nat Protoc 7, 1836–1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Yan H, Frost P, Gera J, and Lichtenstein A (2005). Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors activate the AKT kinase in multiple myeloma cells by up-regulating the insulin-like growth factor receptor/insulin receptor substrate-1/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase cascade. Mol. Cancer Ther. 4, 1533–1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan A, Hassan-Abdi R, Renault S, Siekierska A, Riché R, Liao M, de Witte PAM, Yanicostas C, Soussi-Yanicostas N, Drapeau P, et al. (2018). Non-canonical mTOR-Independent Role of DEPDC5 in Regulating GABAergic Network Development. Curr. Biol. 28, 1924–1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoreen CC and Sabatini DM (2009). Rapamycin inhibits mTORC1, but not completely. Autophagy 5, 725–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran LH and Zupanc ML (2015). Long-Term Everolimus Treatment in Individuals With Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: A Review of the Current Literature. Pediatr. Neurol. 53, 23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vanKranenburg M, Hoogeveen-Westerveld M, and Nellist M (2015). Preliminary functional assessment and classification of DEPDC5 variants associated with focal epilepsy. Hum. Mutat. 36, 200–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winden KD, Sundberg M, Yang C, Wafa SMA, Dwyer S, Chen P, Buttermore ED, and Sahin M (2019). Biallelic Mutations in TSC2 Lead to Abnormalities Associated with Cortical Tubers in Human iPSC-Derived Neurons. J. Neurosci. 39, 9294–9305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson RL, and Sabatini DM (2017). The Dawn of the Age of Amino Acid Sensors for the mTORC1 Pathway. Cell Metabolism 26, 301–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuskaitis CJ, Jones BM, Wolfson RL, Super CE, Dhamne SC, Rotenberg A, Sabatini DM, Sahin M, and Poduri A (2018). A mouse model of DEPDC5-related epilepsy: Neuronal loss of Depdc5 causes dysplastic and ectopic neurons, increased mTOR signaling, and seizure susceptibility. Neurobiol. Dis. 111, 91–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuskaitis CJ, Rossitto LA, Gurnani S, Bainbridge E, Poduri A, and Sahin M (2019). Chronic mTORC1 inhibition rescues behavioral and biochemical deficits resulting from neuronal Depdc5 loss in mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 28, 2952–2964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.