Abstract

Chlorpyrifos (CPF) [O, O-diethyl -O-3, 5, 6-trichloro-2-pyridyl phosphorothioate] is an organophosphate insecticide widely used for agricultural and urban pest control. Trichloropyridinol (TCP; 3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridinol), the primary metabolite of CPF, is often used as a generic biomarker of exposure for CPF and related compounds. Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK 293) cells were exposed to CPF and TCP with varying concentrations and exposure periods. Cell cultures enable the cost-effective study of specific biomarkers to help determine toxicity pathways to predict the effects of chemical exposures without relying on whole animals. Both CPF and TCP were found to induce cytotoxic effects with CPF being more toxic than TCP with EC50 values of 68.82 μg/mL and 146.87 μg • ml−1 respectively. Cell flow cytometric analyses revealed that exposure to either CPF or TCP leads to an initial burst of apoptotic induction followed by a slow recruitment of cells leading towards further apoptosis. CPF produced a strong induction of IL6, while TCP exposure resulted in a strong induction of IL1α. Importantly, the concentrations of CPF and TCP required for these cytokine inductions were higher than those required to induce apoptosis. These data suggest CPF and TCP are cytotoxic to HEK 293 cells but that the mechanism may not be related to an inflammatory response. CPF and TCP also varied in their effects on the HEK 293 proteome with 5 unique proteins detected after exposure to CPF and 31 unique proteins after TCP exposure.

Keywords: adverse outcome, apoptosis, biomarkers, CPF, chlorpyrifos, TCP

1. Introduction

Toxicological risk assessments have traditionally focused on apical endpoints rather than the biologic changes leading to an adverse health outcome. These studies can be expensive, rely heavily on animals and require species extrapolation for human health risk assessment (NRC, 2007). The traditional toxicological approach of relying solely on whole animal testing to assess the effects of xenobiotics on human and ecological health cannot keep pace with the thousands of chemicals already in existence or the new chemicals constantly being introduced. The National Academy of Sciences report, Toxicity Testing in the 21st Century laid the foundation for a paradigm shift toward the use of other scientific tools to expand in vitro pathway-based toxicity testing and minimize whole animal approaches (NRC, 2007). These alternative methods such as bioinformatics analyses of exposed human cell cultures are gaining acceptance at predicting in vivo toxicity using a bottom-up-approach (Adeleye et al., 2015; Grafstrom et al., 2015; Rouquie et al, 2015), assisting in adverse outcome pathway (AOP) development (Ankley et al., 2010; OECD, 2013; Groh et al., 2015) and to identify biomarkers of exposure and effect. Biomarkers of exposure are used to assess the amount of a chemical that is present and may also provide information on the relative importance of different exposure pathways and associated risk. Biomarkers of effect are indicators of a change in biologic function in response to a chemical exposure and may provide direct insight into the potential for determining adverse health effects and pathways.

Chlorpyrifos (CPF) [O, O-diethyl O-(3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridyl) phosphorothioate] is a broad-spectrum organophosphate (OP) insecticide used for many years for the control of economically important agricultural and urban pests (Eaton et al., 2008). CPF has served a key role in safeguarding food and feed crops, protecting public and veterinary health, and maintaining ornamentals and turf grasses around homes and public areas. Residential uses of CPF products were eliminated in the United States in 2000, with the exception of ant and roach baits in child resistant packaging and fire ant mound treatments (Grube et al., 2011; Stone et al., 2009). Prior to the ban, Dursban (20% CPF a.i.) was the most widely used household pesticide in the United States. In 2007, CPF was the most commonly used OP in the United States (Grube et al., 2011). Lorsban (15 – 75% CPF a.i.) is still in use for agricultural and urban turf purposes.

Direct dietary exposure to trace levels of CPF in foods (estimated to be 0.009 μg/kg body weight) is the main exposure route in the U.S. since the ban of indoor sprays (Trunnelle et al., 2014). Upon ingestion, CPF quickly passes from the intestines to the bloodstream and is distributed throughout the body and may be stored in fat tissues (Chaou et al., 2013). Acute poisoning from CPF results mainly from interference with the acetylcholine neurotransmission pathway (Ethan et al., 2008). CPF may also affect other neurotransmitters, enzymes and cell signaling pathways, potentially at doses below those that substantially inhibit acetylcholinesterase activity. The extent and mechanism of these effects remain to be fully characterized. CPF also passes quickly to the bloodstream after an inhalation exposure. Dermal exposure is not as problematic as only a small amount (3% of applied test dose) has been shown to be able to penetrate the skin.

Chlorpyrifos-oxon is formed by the bioactivation of CPF through the family of cytochromes P450 and is responsible for cholinergic toxicity and the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (Eathan at al., 2008; Timchalk et al., 2006; Clegg and van Gemert, 1999). Detoxification of the oxon is through the A-esterases, as well, as the cytochromes P450 leading to the primary metabolite 3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridinol (TCP) with subsequent glucuronidation for urinary elimination (Timchalk et al., 2006; US. EPA, 1986). Studies indicate that >90% of CPF is eliminated from the body within 48 hours although clinical signs of CPF–induced toxicity may persist for several weeks after exposure depending on the dose (ATSDR, 1997; Koch et al., 2001). The oral lethal dose (LD50) for CPF ranges from 32 to 1,000 mg/kg body weight in a variety of species (Eathan et al., 2008; ATSDR, 1997)

A major degradation pathway of CPF in the environment is the hydrolysis of the phosphorous ester bond to produce TCP (Racke, 1993). TCP is more persistent in the environment than CPF itself (U.S. EPA, 2002). Due to its high water solubility TCP may persist in soils and in aquatic systems (Amer et al., 1992; Yücel et al., 1999; Racke et al., 1988) posing exposure risks. TCP is also a marker of exposure and the environmental degradate for the foliar herbicide triclopyr (3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridinyloxyacetic acid) and CPF-methyl, a grain fumigant.

Population based studies conducted between 1995 and 2001, found average urinary concentrations of 3 – 5 ppb TCP; however, concentrations 10–20 times higher have frequently been found (Ethan et al., 2008). TCP is not a specific biomarker of CPF exposure as residues of TCP can appear on fruits and vegetables, often at higher concentrations than CPF and the use of CPF-methyl on grains and the herbicide triclopyr may also contribute to the TCP levels in humans leading to overestimates of CPF exposure by up to 20-fold.

CPF and its metabolism may be linked to a number of serious health impacts dependent upon the species, dose and exposure period. Reports indicate that CPF and TCP exposure to various species may lead to DNA damage (Wang et al., 2014), altered gene expression (Estevan et al., 2013; Abdelaziz et al., 2010), increased apoptosis (Li et al., 2007; Li et al., 2009; Nakadai et al., 2006), increased number of micronuclei during embryonic development (Tian and Yamauchi, 2003), and an increased frequency of chromosomal aberrations and sister chromatid exchanges (Amer and Aly, 1992). Chronic human exposure to CPF may lead to acute renal failure (Cavari et al., 2013). CPF can also affect protein synthesis in brains of young rats (Slotkin et al., 2009) and has been shown to affect the proteome of the model organism Dictyostelium discoideum (Boatti et al., 2012). Zebrafish embryos exposed to CPF showed an increase in proteins associated with detoxification and stress response and a decrease for proteins related to cytoskeleton structure, protein translation, signal transduction and lipoprotein metabolism (Liu et al., 2015). CPF toxicity can also act through other mechanisms such as inflammation and oxidative stress (Salyha, 2013). Chlorpyrifos-induced brain injury may be mediated through pro-inflammatory pathways as indicated in mice given various dosages (20 – 140 mg/kg) of chlorpyrifos over exposure periods up to 24 hours. Expression of the pro-inflammatory mediators TNF-alpha, IL-6, MCP-1 and E-selectin were observed in several brain regions (Hirani et al., 2007). Exposure of human neuronal SH-SY5Y cells to CPF showed elevated expression of COX-2 with a subsequent increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNA-alpha, indicating oxidative stress and inflammation (Lee et al., 2014). It has recently been reported that CPF resulted in DNA breaks leading to apoptosis in human kidney cells (Li et al., 2015). We expand on these findings by demonstrating the effects of dosage and exposure duration on human embryonic kidney (HEK 293) cells to both CPF and TCP and our preliminary findings on the effects of CPF and TCP on the HEK293 proteome.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell culture

HEK 293 cells were from the American Type Culture Collection (A.T.C.C., Manassas, VA). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C, with 5% CO2 in tissue culture flasks. The cell cultures were observed daily with an inverted microscope. When a culture was 70–80% confluent, the cells were washed with 1X Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (DPBS) and trypsinized by addition of 0.25% trypsin and 0.53 mM EDTA to foster cell detachment from the flask. The suspended cells were stained with trypan blue, counted with a TC10 automated cell counter (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and used to seed new culture flasks.

2.2. CPF and TCP Dosage Experiments

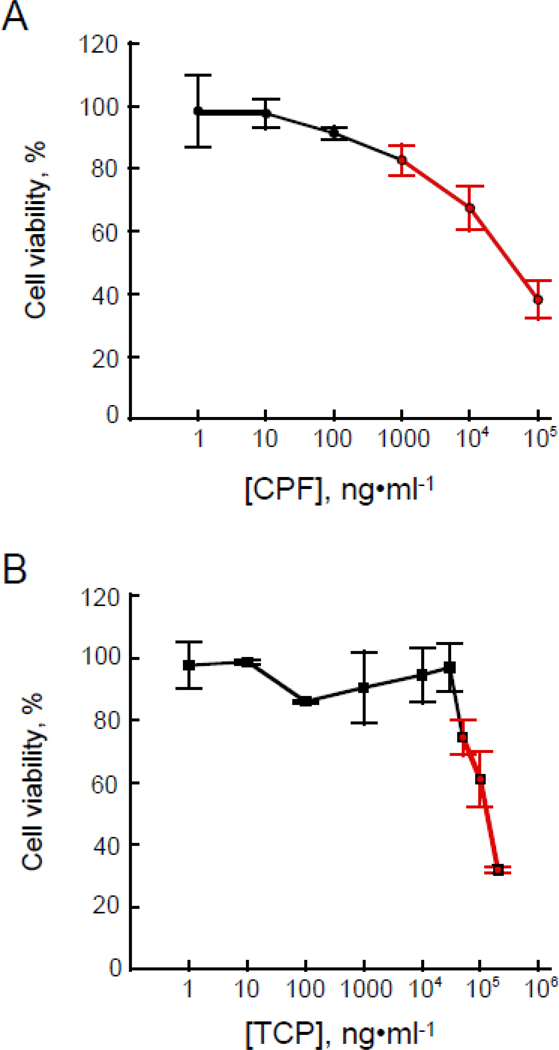

Cells were seeded at 27,000 cells per well in 96-well tissue culture plates and cultured overnight in growth media. The cells in 2 mL growth media, were treated with either CPF in methanol over the concentration ranges of 1–100,000 ng/mL CPF (as indicated Fig. 1A) or with TCP in methanol over the concentrations ranges of 1–250,000 ng/mL TCP (as indicated in Fig. 1B). The QA controls of growth media alone and growth media with 5 μL methanol were always included as controls to verify the non-effects of methanol. After a 24 h exposure period, cellular viability was estimated using a Cell Counting Kit-8 assay (CCK-8; Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan). The procedure is based on the conversion of a tetrazolium salt to a formazan dye upon reduction by dehydrogenases in the presence of an electron carrier (Ishiyama et al., 1997; Tominaga et al., 1999). A CCK-8 solution (10 μl) was added to each well of the 96-well tissue culture plates, followed by incubation for 4 h at 37 °C, with 5% CO2. Absorbance (Abs) values at 450 nm were obtained using a microplate spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices). Dose response curves illustrating cell viability are shown in Figures 1a for CPF and 1b for TCP. As per the manufacturer’s suggestion, cell viability was determined using the equation:

Fig. 1.

Effects of A) Chlorpyrifos (O, O-diethyl O-(3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridyl) phosphorothioate; CPF) and B) its primary metabolite, 3,5,6-trichloro pyridine-2-phenol (TCP) on cell viability as measured using the CCK-8 assay in cultured human embryonic kidney (HEK 293) cells. The red line indicates the portion of the graph used to determine the effective dose concentration as indicated in the text. Values represent means ± SE of n = 3 separate and independent cell culture preparations.

2.3. Flow cytometry

Concentrations of CPF and TCP observed to cause cell death were determined from the above range finding experiments (red lines in Fig. 1). For flow cytometry analyses, cells were plated at 270,000 cells per well in 2 ml growth media in 6-well culture plates and incubated overnight at 37 °C, with 5% CO2. Cells were exposed to CPF (0, 10, 30, 60, and 90 μg/mL) or TCP (0, 50, 100, 150, and 200 μg/mL) in 5 μL methanol along with the methanol control. After 24 h of exposure, cells were observed using phase-contrast microscopy to characterize cell morphological changes as well as cellular distribution over the growth area and then imaged for analysis. Exposure duration data were obtained by exposing cells for 24, 48, and 72 h to either CPF (0, 30, and 60 μg/mL) or TCP (0, 50, or 150 μg/mL) with the methanol QA control. After each time point, cells were washed off the culture plates with DPBS and trypsin. An aliquot (10 μL) of suspended cells was stained with trypan blue and counted using a TC10 automated cell counter.

Cells were next labeled with annexin V and propidium iodide to detect the level of apoptotic cells during the exposure timeframe. Annexin V is an indicator for early apoptosis as it binds phosphatidylserine that is exposed to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane during apoptosis while propidium iodide stains DNA indicating a later apoptotic phase (Vermes et al., 1995). The suspended cells were centrifuged at 150 x g for 5 min and the supernatant was removed. One million cells were washed twice with 5 mL of cold 1x PBS (phosphate-buffered saline, 10 mM PO43-, 137 mM NaCl, and 2.7 mM KCl, pH 7.4) and centrifuged at 300 x g for 5 min. Cells were suspended with the addition of 1 mL binding buffer (0.01 M Hepes, 0.14 M NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4). Cells were then incubated in the dark for 15 min at room temperature following the addition of 5 μl of FITC-annexin V (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and 5 μL of propidium iodide. Subsequently, 400 μL of binding buffer was added to each tube before detection by flow cytometry (BD FACS Calibur, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Flow cytometry was performed as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The QA control of cell media alone without methanol was used to normalize the flow cytometry gating for the exposure duration experiments to allow comparisons between days.

An antibody approach was used for detection of the cytokines, interleukins 1α (IL1α) and 6 (IL6). IL1α is expressed in HEK 293 cells where it is associated with inflammatory reactions (Luheshi et al., 2009). IL6 is also expressed by HEK 293 cells and has an active role in mediating febrile and acute phase responses (Spiegel and Weber, 2006; Mihara et al., 2012). One million cells were washed twice with 5 mL of cold 1x PBS and centrifuged at 300 x g for 5 min at 4 °C. Cells were resuspended in 100 μL cold 1x PBS and fixed by adding 900 μL of 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at 37 °C. Cells were chilled on ice for 1 min before being washed twice with 1 mL cold 1x PBS and centrifuged at 300 x g for 5 min at 4 °C. Cells were resuspended in 100 μL of cold 1x PBS and permeabilized by slowly adding 900 μL of 100% cold methanol to a final concentration of 90% methanol for 30 min on ice. Cells were centrifuged at 300 x g for 5 min at 4 °C and the supernatant was discarded. The cell pellet was washed twice using 1 ml of incubation buffer (0.5 g bovine serum albumin in 100 mL of 1x PBS) and then centrifuged at 300 x g for 5 min at 4 °C. Cells were resuspended and blocked for non-specific binding in 100 μL incubation buffer for 10 min at room temperature. 1 μL of either IL1 α or IL6 specific antibodies conjugated to FITC (Cat. Nos. 11–7118-41 and BMS130FI, eBiosciences, San Diego, CA) was added and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were rinsed twice by adding 1 mL of incubation buffer and centrifuging at 300 x g for 5 min at room temperature. Cells were suspended in 0.5 mL of 1x PBS and analyzed on the flow cytometer.

2.4. Enzymatic Digestion of Cell Culture Fluid for LC/MS-MS Analysis

Cell culture fluid from the CPF (30 μg/mL) and TCP (100 μg/mL) 24-hour exposure period was used as these compound levels yielded a median response for cell viability. Cells were centrifuged at 13,336 x g for 10 minutes. The supernatants were discarded and 50 mL of 0.2% RapiGest, an acid-labile surfactant (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA), in a 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate:1 mM calcium chloride digestion buffer, pH10, was added to the cell pellets and vortexed to mix. Tubes containing the disrupted cells were incubated at 99 °C for 10 minutes, centrifuged at 21,000 x g for 10 minutes, and the resulting supernatants collected. An enzymatic digestion was performed with sequence grade trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The treated cell lysates and trypsin (~50 pmol) in digestion buffer (ammonium bicarbonate) were incubated at 37 °C for 16 hrs. The filtrates were hydrolyzed using 1.2 M HCl (10 μL) and dried using an Eppendorf vacuum-centrifuge with no heat. The dried digests were reconstituted to a final volume of 50 μL with 0.1% formic acid (FA), vortexed and centrifuged at 21,000 x g for 10 minutes. The supernatants containing the peptides were frozen at −70 °C if not used immediately.

2.5. LC/MS-MS Analyses, Blasting and Database Search

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) was performed on the digested cell lysates using a nUPLC system (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA), coupled to a linear ion trap (LTQ)-Velos Orbitrap tandem MS instrument (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA). Peptides were separated using a nUPLC system directly coupled on-line to the MS instrument through an Advance Captive Spray source from Michrom Bioresources (Auburn, CA, USA). The spray voltage was set at 1500 V, and the capillary temperature was 200 °C. The nUPLC separation was performed using a Symmetry C18 trapping column and a BEH C18 analytical column (100 μm ID x 100 mm long with 1.7 μm packing) as described in (Moura et al., 2011 and 2013). The mobile phase consisted of: (solvent A) 0.2% FA, 0.005% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in water, and (solvent B) 0.2% FA, 0.005% TFA in acetonitrile (ACN). The gradient was set at 5% B for 5 min, followed by a ramp to 40% B over 90 min, then a ramp to 95% B in 1 min. The gradient was then held at 95% B for 5 min before returning to 5% B in 2 min, followed by re-equilibration at 5% B for 5 min. The flow rates were 5 μL/min for 5 min for trapping and 600 nL/min to complete the analytical run.

The MS instrument was programmed to perform data-dependent acquisition by scanning the mass range from m/z 400 to 1400 at a nominal resolution setting of 60,000 FMHM for parent ion acquisition in the Orbitrap as previously used in Moura et al, 2013. Tandem mass spectra of doubly charged and higher charged state ions were acquired for the top 15 most intense ions in each survey scan. All tandem mass spectra were recorded by use of the linear ion trap. This process cycled continuously throughout the duration of the nUPLC gradient. All tandem mass spectra were extracted from the raw data file using Mascot Distiller (Matrix Science, London, UK; version 2.2.1.0), and searched using Mascot (version 2.2.0). Mascot calculates the theoretical mass for each peptide using rules for enzyme cleavage, and was setup to search the entire National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nonredundent (nr) database in which trypsin is used as the digestion agent. Scaffold (v3.01, Proteome Software Inc., Portland, OR, USA) was used to further validate MS/MS-based peptide and protein identifications. The reported data represent three technical replicates and three analytical replicates. Mascot and Scaffold search parameters were used as described by Moura et al., 2011 and 2013, to yield a >95% protein identification probability. The BLAST-2-GO program (BioBam Bioinformatics S.L., Valencia, Spain, version 3.1) was used for protein blasting, mapping, annotating, and for the statistical assessment of annotation differences between sequence sets for further visualizing the MS/MS data.

2.6. Statistical analyses

Cell toxicity data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey multiple comparisons tests. Results with P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. R software was used for all data analyses (R Development Core Team, 2008). The Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) was used to calculate the sequence similarity of proteins determined from the three exposure scenarios. The BLAST algorithm enables a comparison of protein sequences which can be used to determine the proteomic effects of exposure (Altschul, et al., 1990). The process compares protein sequences to known sequence databases and calculates the statistical significance of matches.

3. Results & Discussion

3.1. Effects of CFP and TCP exposure on HEK 293 cell viability and morphology

HEK 293 cells were exposed for 24 h to either CPF (0, 10, 30, 60 and 90 μg/mL) or TCP (0, 50, 100, 150 and 250 μg/mL) and the QA methanol control. Cell viability was measured using a CCK-8 assay (Fig. 1). Loss of viability occurred as the dose concentration of either compound was increased (Fig.1). Linear regression equations across the effective dose range (red lines in Fig.1) revealed EC50 = 68.82 μg/mL for CPF and 146.87 μg/mL for TCP. A linear regression was used since a log-logistic concentration effect analysis would require additional data points that were not available in our experimental paradigm (Focke, et al., 2017). Untreated cells exhibited the characteristic flattened shape of adherent cells with round boundaries and tight cell junctions (data not shown). Distressed cells oftentimes swell or shrink resulting in irregular boundaries, or detach and aggregate into clusters floating in the medium. At the highest doses for both CPF and TCP, many cells appeared dead.

3.2. Effects of CPF and TCP exposure on apoptosis for HEK 293 cells

Cells exposed to CPF (0, 10, 30, 60, and 90 μg/mL) or TCP (0, 50, 100, 150, 250 μg/mL) for 24 h along with the QA methanol control were analyzed by flow cytometry to determine the extent of apoptosis. Representative data are shown in Fig. 2 and explained in the figure legend. Flow cytometry was able to effectively discriminate viable cells from those that were either undergoing apoptosis or that were dead. In summary, as the concentration of the compound increased (Fig. 2 D–F), the number of viable cells decreased while those that were either dead or that were undergoing apoptosis increased. These data are summarized in Fig. 3 (for CPF) and Fig. 4 (for TCP). There was no statistical difference between the cell culture media and methanol QA controls on cell viability or on the apoptotic state for either CPF or TCP exposure (ANOVA, P > 0.05), indicating that the methanol vehicle did not affect cell viability. In contrast, a 24 h exposure to 30 μg/mL CPF resulted in a decrease in viability and the onset of apoptosis (ANOVA, P < 0.05). Increased concentrations of CPF also resulted in greater decreases in viability and increased involvement of apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner (ANOVA, P < 0.05). Similarly, a 24h exposure to 50 μg/mL TCP resulted in decreases in viability and onset of apoptosis (ANOVA, P < 0.05). Increased concentrations of TCP also resulted in decreases in viability and increased involvement of apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner (ANOVA, P < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Exemplary flow cytometry data for the apoptosis experiments. A) Key to the gating windows for the flow cytometry e.g. cells that had low entry of propidium iodide and low binding of annexin V were deemed viable. B) Color map for the flow cytometry data. Blue dots represent few cells while red dots represent larger numbers of cells. C) Flow cytometry data for cells exposed to 5 μl methanol (QA control with vehicle). Raw flow cytometry data for a single replicate of 1,000,000 cells exposed to D) 10, E) 30, or F) 90 μg • ml−1 CPF in 5 μl methanol.

Fig. 3.

Summary data for three independent flow cytometry replicates for the effects of increasing doses of CPF on: A) percentage of cells not experiencing apoptosis or dead, B) percentage of cells that are dead; C) percentage of cells that are early in the apoptotic signaling process; and D) percentage of cells that are late in the apoptotic process. Analyses were performed as per Fig. 2. Data are means ± S.E. Statistical differences are indicated by different letters. Each replicate represents an independent culture, preparation, and flow cytometry assay.

Fig. 4.

Summary data for three independent flow cytometry replicates for the effects of increasing doses of TCP on apoptotic induction. Details as per Fig 3.

Data analysis for early versus late apoptosis for the CPF exposure duration experiments showed the data are consistent with an initial bolus of cells entering apoptosis in response to high doses of CPF and TCP (Supplemental Figs. S1 and S2). Interestingly, there was no expected recruitment of additional late apoptotic cells following this initial bolus. Instead at the high dose of 60 μg/mL CPF, the percentage of cells in late apoptosis, although still high, is actually reduced in comparison to the value at 24 h for cells exposed to CPF for 48 and 72 h. This finding is consistent with a model of an initial bolus of cells entering apoptosis and perhaps slow attrition of the remaining cells. We note that our preparation wherein cells were washed prior to flow cytometry may have washed away dead cells. We believe this step may help explain why there is no accumulation of dead cells (Figs. S1–S2B) over the time course despite few cells at the highest dosages not being involved in apoptosis or being already dead (Figs. S1–S2A and labeled as viable cells).

3.3. Effects of CPF and TCP on the expression of IL1α or IL6

We examined if CPF and TCP exposure would lead to inflammatory responses as indicated by the expression of the cytokines, IL1α or IL6. There was no statistical difference between the QA controls for either IL1α or IL6 expression in the CPF or TCP 24 h exposure experiments (ANOVA, P > 0.05). While lower doses of CPF and TCP elicited involvement of apoptosis (Figs. 3–4), the number of cells expressing greater IL1α was only increased when cells were exposed for 24h to 90 μg/mL CPF (Fig. 5; ANOVA, P < 0.05). The number of cells with increased IL6 expression increased when cells were exposed to 60 μg/mL CPF (Fig. 6). Interestingly, this pattern was not evident for IL1α or IL6 expression in response to TCP exposure. Here, expression of IL1α increased with 150 μg/mL TCP but IL6 did not increase until the dose was 250 μg/mL TCP for a 24 h exposure. These data might suggest a secondary effect wherein the large numbers of apoptotic and dead cells elicited an inflammatory response. We also examined how longer periods of exposure might influence the interleukin expression patterns at different concentrations (Figs. S3–S4). At higher compound doses longer periods of exposure resulted in more cells expressing IL1α (Fig. S3) and IL6 (Fig. S4).

Fig. 5.

Effects of A) CPF or B) TCP on the percentage of cells with elevated concentrations of interleukin protein 1α (IL1α) during a 24-hour exposure period. Cells were deemed positive for IL1α using flow cytometry as detailed in the methods section. Values represent means ± S.E. for n = 3 independent culture, preparation, and assay replicates. Statistical differences are indicated by different letters.

Fig. 6.

Effects of CPF (A) and TCP (B) concentrations on the production of interleukin protein 6 604 (IL6) during a 24-hour exposure period. Details as in Fig. 5.

3.4. Effects of CPF and TCP on the HEK 293 Proteome

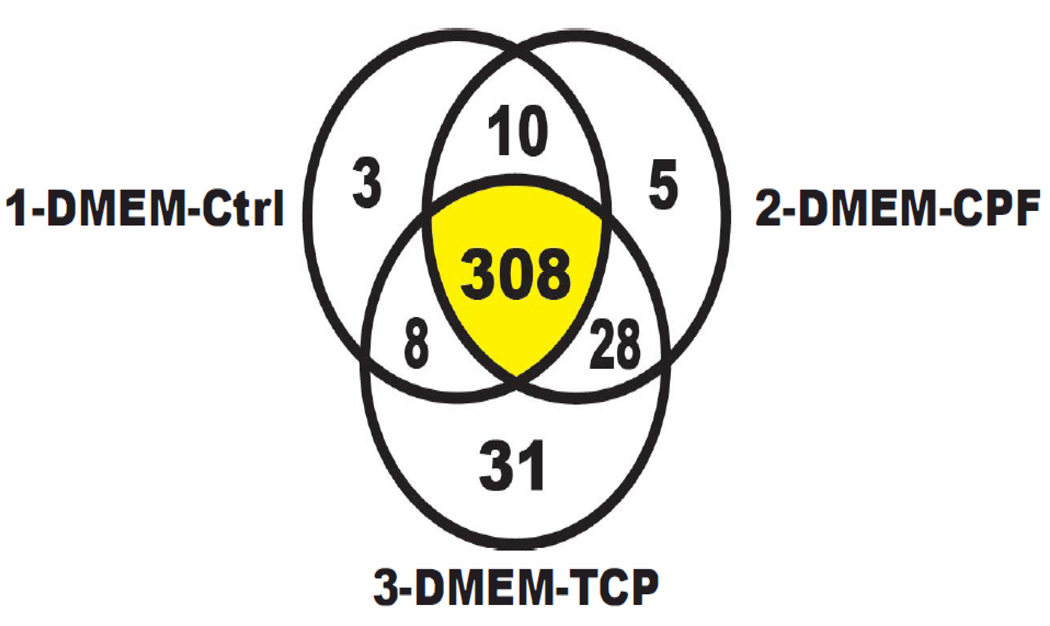

Protein sequence similarity among the three exposure conditions of CPF, TCP and the QA control were calculated using the BLAST algorithm. The BLAST results were compared to the NCBI nr data base for human and trypsinized proteins. Using this proteomic approach, over 518 peptides were identified using HR-MS and assigned to 308 proteins common to all three exposure conditions (Supplementary Table S1). Groups of proteins consistently appeared only after cell exposure to the compounds. An in depth analysis of this large protein pool will identify proteins that are either up-regulated or down-regulated in response to CPF or TCP exposure. The identification of these proteins was out of the scope of this project as our interest was in the unique proteins seen after the different exposure scenarios. It is significant that 64 proteins were detected after exposure to CPF and TCP of which 55 were identified with high confidence. Five were unique to CPF exposure, thirtyone from TCP, and five were from the control (Fig 7). Twenty-eight proteins were common to both CPF and TCP exposures. The 39 proteins are listed in Supplementary Table S-1 with their accession numbers and descriptions which can be used for further study such as biomarker determination. Links to the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) records are given for proteins that were definitely identified. OMIM summaries provide data to help understand gene function, although deeper searches of data bases and other sources are often warranted. The validated proteins were analyzed using BLAST-2-GO. The resulting pie charts (Figure 8A–C) represent the impacts of the unique proteins detected under exposure to both CPF and TCP as related to: (A) Biological Processes, (B) Molecular Function and (C) Cellular Components. Sequences for biological processes included metabolic and developmental processes, biological regulation, and response to stimulus (Fig 8A). A molecular function gene ontology analysis within the BLAST-2-GO program indicated that the majority of sequences found were for binding proteins (Fig 8B). Sequences in the GO analysis for cellular components ranged from those relating to membrane, organelle, and extracellular regions (Fig 8C). Sequences for six major enzyme classes (i.e., oxidoreductases, transferases, hydrolase, lyases, isomerases, and ligases) were also found (data not shown).

Fig. 7.

Effects of CPF (30 μg/mL), TCP (100 μg/mL) and the QA control on the HEK293 proteome during a 24-hour exposure.

Fig. 8.

Blast2GO analysis of new proteins found after CPF and TCP exposure. The validated proteins were analyzed using Blast2GO. The pie charts represent the impacts of the unique proteins detected under both exposure conditions as related to: (A) Biological Processes, (B) Molecular Processes and (C) Cellular Components. The level refers to the distance from the GO term to the root term.

4. Conclusions

The effects of CPF and TCP exposure on human cells have been addressed previously for immune cells, hepatocytes, and very recently kidney cells (Nakadai et al., 2006; Li et al., 2009, Das et al., 2011; Li et al., 2015). Consistent with our findings, Li et al. (2015) found similar concentrations to those used here to induce apoptosis in HEK 293 cells. Exploiting a comet assay, these authors determined that there were DNA breaks as a result of exposure to CPF. What was not determined is whether prolonged exposure and/or exposure to TCP, the primary metabolite for CPF elimination, affected cells in the same manner, or if such exposures lead to changes in the protein profile as indicated in this study.

Our results demonstrate that both CPF and its primary metabolite, TCP, are toxic to HEK 293 cells (Fig. 1). Large scale changes in cellular morphology are evident and this toxicity appears to be mediated through induction of apoptosis as evidenced by presentation of phosphatidylserine on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane following both CPF and TCP exposure (Figs. 3–4). Our data on prolonged exposure to these compounds suggest that there is an initial burst of apoptotic induction followed by a slowed attrition of the cells (Figs. S1–S2). These data may be indicative of the variation in cell vigor in a population. Less vigorous cells enter apoptosis early while more vigorous cells resist the pro-apoptotic effects of CPF and TCP.

Our data on the important cytokines, IL1α (Fig. 5) and IL6 (Fig. 6) reveal an intriguing outcome. Exposure to CPF appeared to elicit a greater IL1α and a somewhat blunted IL6 induction. However, exposure to TCP resulted in the opposite pattern. Both IL1α and IL6 have important roles in immune responses and inflammatory reactions (Luheshi et al., 2009, Spiegel and Weber, 2006, Mihara et al., 2012). Our data also suggest that while there is an apparent pro-inflammatory response as indicated by an increased numbers of cells expressing both IL1α and IL6, the dosage required to elicit these responses varies for these cytokines and is higher than the dose required to elicit entrance into apoptosis (Figs. 3 and 4). Such a finding suggests that apoptosis is initiated by an inflammation-independent mechanism. Only after a number of cells have been involved in apoptosis, does the inflammatory response become evident.

In conclusion, our results support those involving other cell types that CPF and TCP are toxic to human cells. A primary mechanism appears to be the induction of apoptosis. However, inflammatory responses appear to be a secondary outcome which may obfuscate elucidation of the mechanism. We further show that CPF and TCP can affect protein expression in human embryonic kidney cells resulting in 64 unique proteins. The differentiating effects of CPF and TCP exposures may be resolved through in depth omic analyses of data mining to assess the functional meaning of CPF and TCP exposures, particularly when applied within a systems toxicology approach, furthering the understanding of CPF and TCP toxicity and the identification of biomarkers exposure and effects (Tollefsen et al, 2014; and Willett et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2015) while minimizing the use of whole animals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Instrumentation that supported this project was made available by a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P20GM103440). Although the research described in this article has been funded in part by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency through contracts EP-W-09-024 and EP-D-04-068, it has not been subjected to Agency review. Therefore, it does not necessarily reflect the views of the Agency. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use.

We gratefully acknowledge the collaborations of Dr. Hercules Moura and Doris Ash of the Centers for Disease Control for their participation in this project.

References

- Abdelaziz KB, El Makawy AI, Elsalam AZE-AA, Darwish AM, 2010. Genotoxicity of Chlorpyrifos and the Antimutagenic Role of Lettuce Leaves in Male Mice. Comunicata Scientiae. 1 (2), 137–145. [Google Scholar]

- Adeleye Y, Andersen M, Clewell R, Davies M, Dent M, Edwards S, Fowler P, Malcomber S, Nicol B, Scott A, Scott S, Sun B, Westmoreland C, White A, Zhang Q, Carmichael PL, 2015. Implementing Toxicity Testing in the 21st Century (TT21C): Making safety decisions using toxicity pathways, and progress in a prototype risk assessment. Toxicology. 332, 102–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), United States Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service. 1997. Toxicological profile for chlorpyrifos. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albers JW, Garabrant DH, Schweitzer SJ, Garrison RP, Richardson RJ, Berent S, 2004. The effects of occupational exposure to chlorpyrifos on the peripheral nervous system: a prospective cohort study. Occup. Environ. Med. 61, 201–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ, 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amer SM, Aly FAE, 1992. Cytogenetic effects of pesticides. IV. Cytogenetic effects of the insecticides Gardona and Dursban. Mutat. Res. 279, 165–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankley GT, Bennett RS, Erickson RJ, Hoff DJ, Hornung MW, Johnson RD, Mount DR, Nichols JW, Russom CL, Schmieder PK, Serrrano JA, Tietge JE, Villeneuve DL, 2010. Adverse outcome pathways: a conceptual framework to support ecotoxicology and risk assessment. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 29 (3), 730–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boatti L, Robotti E, Marengo E, Viarengo A, Marsano F, 2012. Effects of nickel, chlorpyrifos and their mixture on the Dictyostelium discoideum proteome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 13, 15679–15705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavari Y, Landau D, Sofer S, Leibson T, Lazar I, 2013. Organophosphate poisoning-induced acute renal failure. Pediatr. Emerg. Care. 29 (5), 646–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers JE, Chambers HW, 1989. Oxidative desulfuration of chlorpyrifos, chlorpyrifos-methyl, and leptophos by rat brain and liver. J. Biochem. Toxicol. 4 (1), 201–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaou CH, Lin CC, Chen HY, Lee CH, Chen THH, 2013. Chlorpyrifos is associated with slower serum cholinesterase recovery in acute organophosphate-poisoned patients. Clin. Toxicol. 51, 402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clegg DJ, van Gemert M, 1999. Determination of the reference dose for chlorpyrifos: proceedings of an expert panel. J. Toxicol. Env. Heal. B. 2, 211–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das PC, Cao Y, Rose RL, Cherrington N, Hodgson E, 2011. Enzyme induction and cytotoxicity in human hepatocytes by chlorpyrifos and N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide (DEET). Drug. Metab. Drug. Interact. 23 (3–4), 237–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton DL, Daroff RB, Autrup H, Bridges J, Buffler P, Costa LG, Coyle J, McKhann G, Mobley WC, Nadel L, Neubert D, Schulte-Hermann R, Spencer PS, 2008. Review of the toxicology of chlorpyrifos with an emphasis on human exposure and neurodevelopment. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. S2, 1–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estevan C, Vilanova E, Sogorb MA, 2013. Chlorpyrifos and its metabolites alter gene expression at non-cytotoxic concentrations in D3 mouse embryonic stem cells under in vitro differentiation: considerations for embryotoxic risk assessment. Toxicol. Lett. 217 (1), 14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Focke WW, van der Westhuizen I, Musee N, Loots MT, 2017. Kinetic interpretation of log-logistic dose-time response curves. Sci. Rep-UK. 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grafström RC, Nymark P, Hongisto V, Spjuth O, Ceder R, Willighagen E, Hardy B, Kaski S, Kohonen P, 2015. Toward the replacement of animal experiments through the bioinformatics-driven analysis of ‘omics’ data from human cell cultures. Altern. Lab. Anim. 43 (5) 325–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groh KJ, Carvalho RN, Chipman JK, Denslow ND, Halder M, Murphy CA, Roelofs D, Rolaki A, Schirmer K, Watanabe KH, 2015. Development and application of the adverse outcome pathway framework for understanding and predicting chronic toxicity: II. A focus on growth impairment in fish. Chemosphere. 120, 778–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grube A, Donaldson D, Kiely T, Wu L, 2011. Pesticides Industry Sales and Usage: 2006 and 2007 Market Estimages. United States Environmental Protection Agency. [Google Scholar]

- Hirani A, Lee WH, Kang S, Ehrich M, Lee YW, 2007. Chlorpyrifos induces pro-inflammatory environment in discrete regions of mouse brain. FASEB J. 21 (6), 785.4. [Google Scholar]

- Ishiyama M, Miyazono Y, Sasamoto K, Ohkura Y, Ueno K, 1997. A highly water-soluble disulfonated tetrazolium salt as a chromogenic indicator for NADH as well as cell viability. Talanta. 44, 1299–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch HM, Hardt J, Angerer J, 2001. Biological monitoring of exposure of the general population to the organophosphorus pesticides chlorpyrifos and chlorpyrifos-methyl by determination of their specific metabolite 3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridinol. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health. 204, 175–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JE, Park JH, Jang SJ, Koh HC, 2014. Rosiglitazone inhibits chlorpyrifos-induced apoptosis via modulation of the oxidative stress and inflammatory response in SH-SY5Y cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharm. 278, 159–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JW, Won E-J, Raisuddin S, Lee J-S, 2015. Significance of adverse outcome pathways in biomarker-based environmental risk assessment in aquatic organisms. J. Environ. Sci. 35, 115–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Huang Q, Lu M, Zhang L, Yang Z, Zong M, Tao L, 2015. The organophosphate insecticide chlorpyrifos confers its genotoxic effects by inducing DNA damage and cell apoptosis. Chemosphere. 135, 387–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Kobayashi M, Kawada T, 2009. Chlorpyrifos induces apoptosis in human T cells. Toxicology. 255, 53–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Kobayashi M, Kawada T, 2007. Organophosphorus pesticides induce apoptosis in human NK cells. Toxicology. 239, 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Xu Y, Xu L, Wang J, Wu W, Xu L, Yan Y, 2015. Analysis of differentially expressed proteins in zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos exposed to chlorpyrifos. Comp. Biochem. Phys. C 167, 183–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luheshi NM, Rothwell NJ, Brough D, 2009. Dual functionality of interleukin-1 family cytokines: implications for anti-interleukin-1 therapy. Brit. J. Pharmacol. 157, 1318–1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihara M, Hashizume M, Yoshida H, Suzuki M, Shiina M, 2012. IL-6/IL-6 receptor system and its role in physiological and pathological conditions. Clin. Sci. 122 (4), 143–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moura H, Terilli RR, Woolfitt AR, Gallegos-Candela M, McWilliams LG, Solano MI, Pirkle JL, Barr JR, 2011. Studies on botulinum neurotoxins type /C1 and mosaic/DC using endopep-MS and proteomics. FEMS. Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 61, 288–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moura H, Terilli RR, Woolfitt AR, Williamson YM, Wagner G, Blake TA, Solona MI, Barr JR, 2013. Proteomic analysis and label-free quantification of the large Clostridium difficile toxins. Int. J. Proteom. 2013, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakadai A, Li Q, Kawada T, 2006. Chlorpyrifos induces apoptosis in human monocyte cell line U937. Toxicology. 224, 202–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council, 2007. Committee on Toxicity Testing, Assessment of Environmental Agents, Board on Environmental Studies, Toxicology, Institute for Laboratory Animal Research. Toxicity Testing in the 21st Century. A Vision and a Strategy. National Academies Press, Washington D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2013. Series on Testing and Assessment. No. 184. Guidance document on developing and assessing adverse outcome pathways. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2013). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria: URL http://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Racke KD, 1993. Environmental fate of chlorpyrifos. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 131, 1–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racke KD, Coats JR, Titus KR, 1988. Degradation of chlorpyrifos and its hydrolysis product, 3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridinol, in soil. J. Environ. Sci. Heal. B. 23 (6), 527–539. [Google Scholar]

- Rouquié D, Heneweer M, Botham J, Ketelslegers H, Markell L, Pfister T, Steiling W, Strauss V, Hennes C, 2015. Contribution of new technologies to characterization and prediction of adverse effect. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 45 (2), 172–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salyha YT, 2013. Chlorpyrifos leads to oxidative stress-induced death of hippocampal cells in vitro. Neurophysiology+. 45 (3), 193–199. [Google Scholar]

- Simon D, Helliwell S, Robards K, 1998. Analytical chemistry of chlorpyrifos and diuron in aquatic ecosystems. Anal. Chim. Acta. 360, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA, Seidler FJ, 2009. Oxidative and excitatory mechanisms of developmental neurotoxicity: transcriptional profiles for chlorpyrifos, diazinon, dieldrin, and divalent nickel in PC12 cells. Environ. Heal. Perspect. 117 (4), 587–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel M, Weber F, 2006. Inhibition of cytokine gene expression and induction of chemokine genes in non-lymphatic cells infected with SARS coronavirus. Virol. J. 3 (17), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone DL, Sudakin DL, Jenkins JJ, 2009. Longitudinal trends in organophsphate incidents reported to the National Pesticide Information Center, 1995–2007. Environ. Health. 8 (18). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y, Yamauchi T, 2003. Micronucleus formation in 3-day mouse embryos associated with maternal exposure to chlorpyrifos during the early preimplantation period. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 17, 401–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timchalk C, Poet TS, Kousba AA, 2006. Age-dependent pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic response in preweanling rats following oral exposure to the organophosphorus insecticide chlorpyrifos. Toxicol. 220, 13–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollefsen KE, Scholz S, Cronin MT, Edwards SW, de Knecht J, Crofton K, Farcia-Reyero N, Hartung T, Worth A, Patlewicz G, 2014. Applying adverse outcome pathways (AOPs) to support Integrated Approaches to Testing and Assessment (IATA). Regul. Toxicol. Pharm. 70, 629–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga H, Ishiyama M, Ohseto F, Sasamoto K, Hamamoto T, Suzuki K, Watanabe M, 1999. A water-soluble tetrazolium salt useful for colorimetric cell viability assay. Anal. Commun. 36, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Trunnelle KJ, Bennett DH, Tulve NS, Clifton MS, Davis MD, Calafat AM, Moran R, Tancredi DJ, Hertz-Picciotto I, 2014. Urinary pyrethroid and chlorpyrifos metabolite concentrations in Northern California families and their relationship to indoor residential insecticide levels, part of the Study of Use of Products and Exposure Related Behavior (SUPERB). Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 1931–1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2002. Interim registration eligibility decision for chlorpyrifos. EPA 738-R-01–007. [Google Scholar]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Office of Water Regulations and Standards. Criteria and Standards Division. Washington D.C., 1986. Ambient water quality criteria for chlorpyrifos – 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Vermes I, Haanen C, Steffens-Nakken H, Reutelingsperger C, 1995. A novel assay for apoptosis Flow ytometric detection of phosphatidylserine expression on early apoptotic cells using fluorescein labelled Annexin V. J. Immunol. Methods. 184, 39–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Wang J, Zhu L, Xie H, Shao B, Hou X, 2014. The enzyme toxicity and genotoxicity of chlorpyrifos and its toxic metabolite TCP to zebrafish Danio rerio. Ecotoxicology. 23, 1858–1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willett C, Caverly Rae J, Goyak KO, Landesmann B, Minsavage G, Westmoreland C, 2014. Pathway-based toxicity: history, current approaches and liver fibrosis and steatosis as prototypes. Altex. 31, 407–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yücel Ü, Ýlim M, Gözek K, Helling CS, Sarýkaya Y, 1999. Chlorpyrifos degradation in Turkish Soil. J. Environ. Sci. Health. B. 34 (1), 75–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.