Abstract

Introduction

Both recessive and dominant genetic forms of Parkinson’s disease have been described. The aim of this study was to assess the contribution of several genes to the pathophysiology of early onset Parkinson’s disease in a cohort from central Spain.

Methods/patients

We analyzed a cohort of 117 unrelated patients with early onset Parkinson’s disease using a pipeline, based on a combination of a next-generation sequencing panel of 17 genes previously related with Parkinson’s disease and other Parkinsonisms and CNV screening.

Results

Twenty-six patients (22.22%) carried likely pathogenic variants in PARK2, LRRK2, PINK1, or GBA. The gene most frequently mutated was PARK2, and p.Asn52Metfs*29 was the most common variation in this gene. Pathogenic variants were not observed in genes SNCA, FBXO7, PARK7, HTRA2, DNAJC6, PLA2G6, and UCHL1. Co-occurrence of pathogenic variants involving two genes was observed in ATP13A2 and PARK2 genes, as well as LRRK2 and GIGYF2 genes.

Conclusions

Our results contribute to the understanding of the genetic architecture associated with early onset Parkinson’s disease, showing both PARK2 and LRRK2 play an important role in Spanish Parkinson’s disease patients. Rare variants in ATP13A2 and GIGYF2 may contribute to PD risk. However, a large proportion of genetic components remains unknown. This study might contribute to genetic diagnosis and counseling for families with early onset Parkinson’s disease.

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra. It is a chronic and progressive disorder of multifactorial etiology, in which causative and susceptibility genetic factors are involved. Emerging evidence has provided support for the hypothesis that PD is the result of complex interactions among genetic abnormalities, environmental toxins, mitochondrial dysfunction, and other cellular processes.

Since Polymeropoulos et al. identified a causative variant in gene encoding Alpha synuclein (SNCA) [1], many efforts have been made to identify genes involved in the development of PD. Mutations in SNCA, Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2), and Vacuolar Protein Sorting 35 (VPS35) genes have been linked to autosomal dominant forms of PD (ADPD) [2, 3]. In fact, the mutations in LRRK2 are the most common cause of ADPD. In addition, the Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 4 Gamma 1 (EIF4G1), was initially related to ADPD, but subsequent studies have failed to replicate this association [4]. Furthermore, genes related to autosomal recessive forms of PD (ARPD) have also been discovered. Thus, the genes coding for Parkin (PARK2), PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1), and the Protein deglycase DJ1 (PARK7) have been related to typical early-onset PD (EOPD; age at onset <50 years old). Other genes, such as those coding for the ATPase Cation Transporting 13A2 (ATP13A2), the Phospholipase A2 Group VI (PLA2G6), the F-Box Protein 7 (FBXO7), HSP40 Auxilin (DNAJC6) and the Synaptojanin-1 (SYNJ1), have been related to atypical PD with juvenile onset (age at onset <35 years old) [4]. On the other hand, the gene GIGYF2 (encoding Grb10-Interacting GYF Protein 2) has been described as responsible for typical autosomal dominant PD [5]. Its pathogenic contribution to PD is still not clear but it has been suggested that some variations are risk factors for PD in Caucasians [6].

Nevertheless, monogenic mutations are not a very common cause of PD. Indeed, risk variants with a moderate effect size are more usual.

Variations in genes such as GBA (encoding glucocerebrosidase) or SMPD1 (encoding sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase 1) constitute risk factors for PD. In fact, variants in GBA have been proposed as the most important risk factor for idiopathic PD [7].

To date, genome wide association studies (GWAS) have allowed identification of several PD risk loci [8]. However, a large proportion of genetic heritability remains unknown. Nowadays, next generation sequencing (NGS) of whole genome (WGS) or just the exome (WES) are expected to contribute to elucidating the missing heritability through the identification of new risk variants related to PD.

Since genetic background has a higher impact on PD with early disease onset, the aim of this study was to assess the contribution of seven genes previously related to PD, and unconfirmed genes, to the pathophysiology of the EOPD in a cohort of patients from central Spain. For that purpose a combination of NGS-based targeted sequencing and Multiplex Ligation-Dependent Probe Amplification (MLPA) were applied.

Patients and methods

Subjects and clinical assessments

We included 117 unrelated EOPD (age at onset younger than 50 years old) patients. Among them, thirty-three reported a family history of PD. The demographic characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1. Patients were Caucasian and recruited from the Neurology outpatient clinic at different hospitals in the Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid (Spain) and clinically evaluated. An extensive set of clinical features was obtained. PD was diagnosed by Movement Disorders neurologists according to the United Kingdom Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank criteria [9]. After clinical diagnosis, peripheral blood samples were collected from each subject.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of PD patients.

| Sex (M/F) | Age ± SD (y) | AO ± SD (y) | N | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EOPD | Total | 64/53 | 51.7 ± 9 | 40.2 ± 5.3 | 117 |

| Familial PD | 17/16 | 52.2 ± 9.2 | 39.2 ± 5.5 | 33 | |

| Sporadic PD | 47/37 | 51.5 ± 9 | 40.8 ± 5 | 84 | |

EOPD: early-onset Parkinson's disease (age at onset <50 years old); PD: Parkinson's disease; M: males; F: females; y: years; AO: age at onset; SD: standard deviation; N: number of samples.

Ethics statements

The study was approved by the CEIs (Comités de Ética en Investigación) from all participating centers (S1 Methods), and it was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Helsinki Declaration. Each individual who participated in the study signed a written informed consent form prior to blood withdrawal.

Genetic analysis

DNA isolation

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood samples from each subject according to established protocols, by manual and automated commercial procedures (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA). The quantity and purity of the DNA were determined by Qubit 3.0 fluorometer (Invitrogen) and NanoDrop2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Florida, USA), respectively.

Targeted gene enrichment and next-generation sequencing (NGS)

Targeted re-sequencing was performed using a customized Haloplex Target Enrichment Panel, which was designed using Agilent's online Sure Design tool, following the manufacturer’s protocol (Agilent Technologies, Inc. Santa Clara, CA). This customized panel covered all coding exons, exon-intron boundary regions, and 3' and 5' untranslated regions of 17 selected genes. These genes were those related to dominant and recessive forms of PD, as well as risk genes, and unconfirmed genes: SNCA, LRRK2, PINK1, PARK2, ATP13A2, FBXO7, VPS35, DJ1, PLA2G6, EIF4G1, DNAJC6, HTRA2, SMPD1, SYNJ1, UCHL1, GIGYF2, and GBA.

Sample preparation was carried out according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The concentration of the enriched and amplified samples was determined using a Bioanalyzer High Sensitivity chip (Agilent Technologies). Then, samples were pooled in equimolar amounts and sequenced at the Illumina NextSeq platform (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Bioinformatics analysis for NGS results

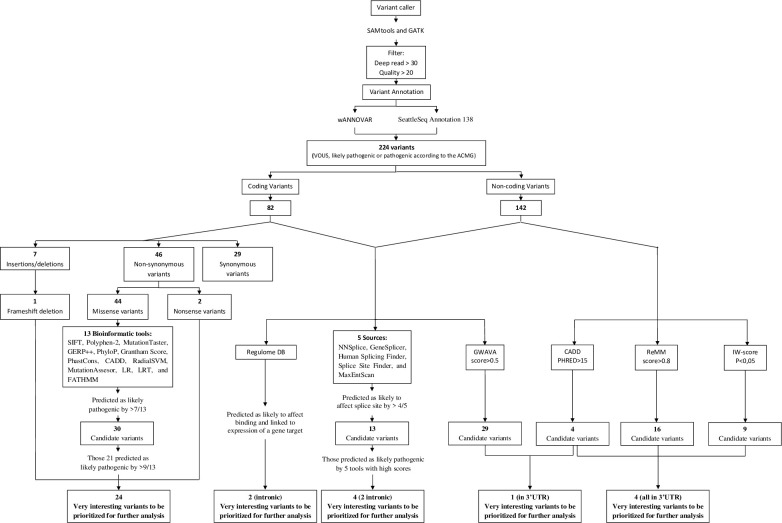

Data analysis and prioritization of variants were performed using the workflow summarized in Fig 1.

Fig 1. Flowchart of sequencing data analysis.

Horizontal boxes represent steps in the workflow. In silico analysis were carried out in 224 SNVs. SIFT: Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant. Polyphen-2: Polymorphism Phenotyping 2. GERP: Genomic Evolutionary Rate Profiling. CADD: Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion. RadialSVM: Radial Support Vector Machine. LR: Logistic Regresion. LRT: Likelihood Ratio Test. FATHMM: Functional Analysis Through Hidden Markov Models. GWAVA: Genome Wide Annotation of Variants. ReMM: Regulatory Mendelian Mutation. IW-score: Integrative Weighted score (with an associated p-value<0.5).

Briefly, sequenced reads quality were examined by FastQC (Babraham Bioinformatics, Cambridge, UK) and poor quality bases were trimmed by Cutadapt v1.9.1. The reference genome was downloaded from NCBI, version GRCh37/hg19. The Burrows-Wheeler Aligner v0.7.12 was used to align the remaining clean reads. All variants, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) and small indels, were detected using SAMtools v1.2. Variants were filtered by Bcftools v1.2 and GATK v4.0, and only those with depth read over 30 and quality over 20 remained. Subsequently, variants were annotated using SeattleSeq Annotation 138 (http://snp.gs.washington.edu/SeattleSeqAnnotation138/) and wANNOVAR (http://wannovar.wglab.org/index.php). The variants where the fraction of non-reference reads was <0.3 were rejected. In addition, a scoring and priorization analysis of deleterious alleles were performed using the software Expert Variant Interpreter (eVAI), from enGenome (www.engenome.com/product) and variants were categorized according to the international guidelines of American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) [10].

For the selection of candidate variants we followed the combination of several criteria (S1 Methods). Missense variants were analyzed with a total of 13 bioinformatic tools. Furthermore, all variants were analyzed using the Batch version of the annotation software package Alamut (Interactive Biosoftware, Rouen, France) for splicing predictions. A threshold was set for each tool above, in which the variant was classified as damaging (S1 Table). The impact was interpreted in relation to all known isoforms of each gene. To restrict the analysis, allele frequencies on population databases were also taken into account.

Sanger resequencing

Filtered variants predicted as pathogenic were validated by Sanger sequencing. Exons containing each selected variant were amplified using standard PCR protocol. Amplicons were sequenced on both strands using the BigDye terminator cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystem, Foster City, CA, USA) and, subsequently, they were resolved on an ABI3500 genetic analyzer and analyzed by software Variant Reporter v1.1 (Applied Biosystem).

In order to avoid the amplification of the neighboring pseudogene, GBA was first amplified in four large fragments that only and specifically amplified the functional gene but not the nearby pseudogene, specific exons were then amplified and sequenced.

Copy Number Variation (CVN) analysis

Multiplex ligation-Dependent Probe Amplification (MLPA) was carried out using two commercially available SALSA MLPA kits (P051 and P052; MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Data were analyzed with the Coffalyser.Net software (MRC-Holland). Analysis of NGS data for CNV identification was performed with VisCap software. Losses were defined by a maximum log2 ratio of -0.55 and a minimum log2 ratio of 0.4 for gains [11].

Results

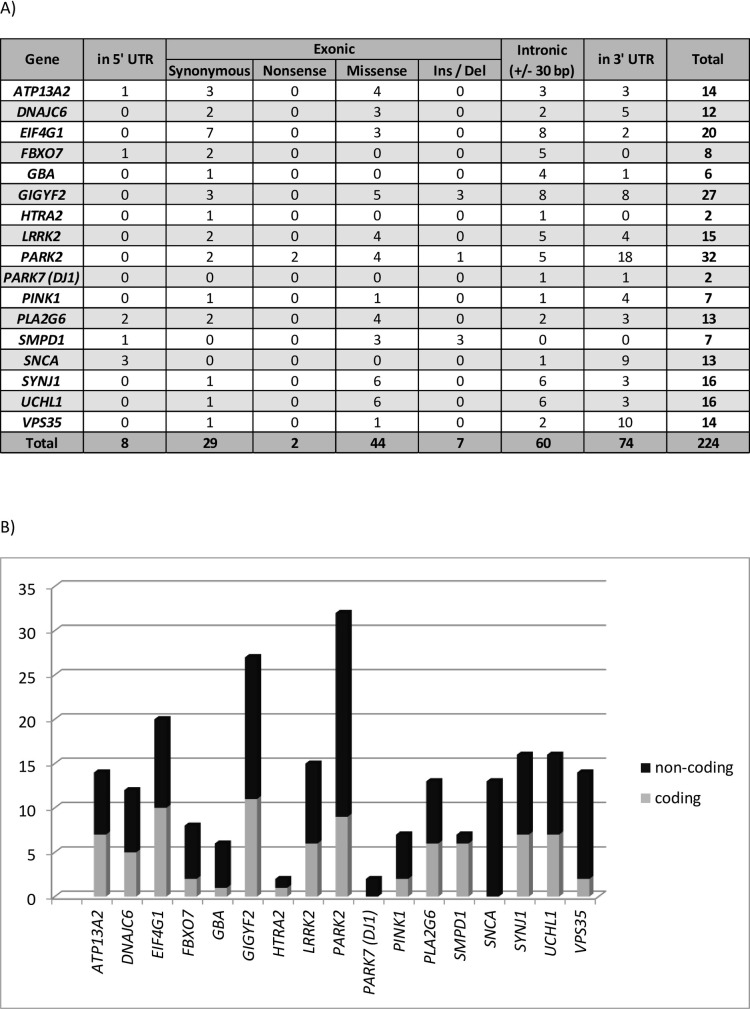

In this study, a total of 224 variants (categorized as variant of unknown significance, likely pathogenic or pathogenic according to the ACMG) were detected by bioinformatics analysis of NGS data, with 82 coding variants and 142 non-coding variants (Fig 2). Subsequently, all of them were further characterized using several algorithms, following the aforementioned analysis, to analyze their putative functional impact (Fig 1). In addition, in CNV analysis, only deletion affecting to exons of PARK2 were detected.

Fig 2. Number and distribution of detected variants in our population using a 17-gene sequencing panel.

Variants in all 17 genes were evaluated and only those described a priori as a variant of unknown significance, likely pathogenic or pathogenic, according to ACMG, are shown. Genes with variants and the variant distribution are displayed (A), and the proportions of coding and non-coding variants are shown for all genes (B).

Identification of the most interesting variants

Firstly, 32 variants, that included the nonsense variants and those missense variants, were kept. These variants were predicted as likely pathogenic at 54% (7 out of 13) of the bioinformatics tools (S2 Table). However, due to prediction tools, in general, have a tendency of over-predicting deleterious impacts, only those variants with >69% in silico predictions in favor of pathogenicity, and/or described as pathogenic in ClinVar were considered as very interesting variants to be prioritized for further analysis (S3 Table).

Three variants, all of them in PARK2, were directly assigned as loss-of-function because they disrupt the protein: two of them were nonsense variants, and one was a deletion of one nucleotide resulting in a frameshift (S3 Table).

In addition, four different deletions affecting to entire exons (all of the gene PARK2) were identified: three single-exon deletions and one affecting four consecutive exons (S3 Table).

Deeper analysis of intronic nsertions or deletions of a few bases and those variations located in the untranslated regions were considered for further analysis.

Thirteen variants were predicted bioinformatically to have a putative effect on splicing (S4 Table). Of them, four variants (rs560897844, rs112019125, rs148944108, and rs41286476) were predicted as likely pathogenic by all tools with high scores, and they presented allele frequencies higher than those in databases (S4 Table).

Two intronic variants had a score of 1f (those that are known eQTLs for genes and have TF binding or a DNase peak) in the RegulomeDB scoring system: rs6437074 (in GIGYF2) and rs2298298 (in PINK1). However, their allele frequencies in our population were very high and similar to those previously described in databases, thus they were excluded.

Lastly, we kept only those variants that were in a heterozygous state in dominant genes, and in homozygous or compound heterozygous states for recessive ones.

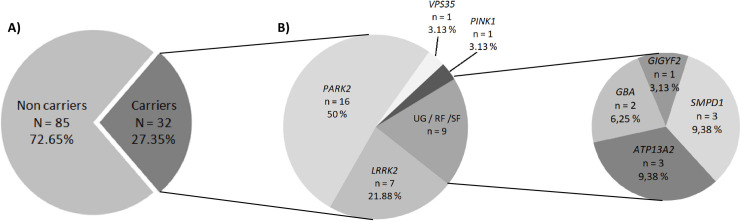

In this way, we identified 32 of the 117 studied patients (27.35%) to be carrying potentially pathogenic variants across 8 genes (Fig 3). Seven patients carried likely pathogenic variations, in LRRK2, 16 in PARK2, 1 in VPS35, and 1 in PINK1. In addition, 9 patients carried likely pathogenic variations in the risk factors: 3 in ATP13A2, 3 in SMPD1, 2 in GBA, and 1 in GIGYF2 (Table 2).

Fig 3. Pie plot showing the distribution and frequencies of likely pathogenic variants found.

In our population, we identified 32 patients carrying likely pathogenic variants (A), of which more than a half presented variations in PARK2 (50%) or LRRK2 (21.88%) (B). UG: Unconfirmed genes. RF: Risk factor. SF: Susceptibility factor. N: number of subjects. n: number of carriers subjects with pathogenic variations in each gene.

Table 2. Patients carrying likely pathogenic variants.

Genotype-phenotype correlations.

| Patient | Gene | Variation (HGVS) | Zigosity | VAF | Coverage (Alt/Ref) | Sex | Age at onset | Family history | Dopaminergic complications (AAOS) | Non-motor symptoms | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDS | AA | MF | DK | N-MF | Depression | CI | VH | ||||||||

| EP-1 | ATP13A2 | c.649G>A | p.Gly217Ser | Het | 0.467 | 353 (165/188) | F | 48 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| EP-2 | ATP13A2 | c.2234G>A | p.Arg745His | Het | 0.466 | 562 (262/300) | F | 45 | Yes | Yes (8) | Yes (8) | No | No | No | No |

| EP-5 | SMPD1 | c.441G>A | p.Val147Val | Het | 0.469 | 1453 (681/772) | M | 45 | No | Yes (4) | Yes (5) | No | Yes | No | No |

| EP-6 | SMPD1 | c.441G>A | p.Val147Val | Het | 0.497 | 1264 (628/636) | M | 49 | No | Yes (4) | Yes (1) | Yes | No | No | No |

| EP-7 | VPS35 | c.1960G>T | p.Ala654Ser | Het | 0.323 | 563 (182/381) | F | 45 | - | Yes | Yes | Yes | yes | No | Yes |

| EP-8 | GBA | c.1040T>C | p.Ile347Thr | Het | 0.490 | 1117 (547/570) | M | 36 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| EP-9 | GBA | c.1208G>A | p.Ser403Asn | Het | 0.462 | 764 (353/411) | M | 40 | Yes | Yes (3) | Yes (4) | Yes (2) | No | No | No |

| EP-10 | PINK1 | c.1040T>C | p.Leu347Pro | Hom | 0.981 | 1776 (1743/33) | M | 25 | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| EP-11 | PARK2 | c.79A>T | p.Lys27Stop | Hom | 0.997 | 567 (565/2) | F | 41 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| EP-12 | PARK2 | c.155delA | p.Asn52Metfs | Hom | 0.985 | 1092 (1076/16) | M | 35 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| EP-13 | PARK2 | c.155delA | p.Asn52Metfs | Hom | 1 | 450 (450/0) | F | 32 | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| EP-14 | PARK2 | c.155delA | p.Asn52Metfs | Hom | 0.985 | 391 (385/6) | F | 37 | - | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| EP-15 | PARK2 | c.155delA | p.Asn52Metfs | Hom | 0.983 | 591 (581/10) | F | 31 | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| EP-16 | PARK2 | c.155delA | p.Asn52Metfs | Hom | 0.998 | 875 (873/2) | F | 42 | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| EP-17 | PARK2 | c.155delA | p.Asn52Metfs | Hom | 0.997 | 387 (386/1) | F | 24 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| ATP13A2 | c.2762+21T>C | - | Het | 0.531 | 443 (235/208) | ||||||||||

| EP-18 | PARK2 | c.155delA | p.Asn52Metfs | Het | 0.336 | 935 (314/621) | F | 37 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| PARK2 | Del ex 7 | - | Het | - | - | ||||||||||

| EP-19 | PARK2 | c.155delA | p.Asn52Metfs | Het | 0.318 | 1407 (447/960) | F | 37 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| PARK2 | Del ex 7 | - | Het | - | - | ||||||||||

| EP-20 | PARK2 | c.155delA | p.Asn52Metfs | Het | 0.348 | 811 (282/529) | F | 28 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| PARK2 | c.719C>T | p.Thr240Met | Het | 0.413 | 1532 (632/900) | ||||||||||

| EP-21 | PARK2 | c.766C>T | p.Arg256Cys | Het | 0.525 | 1959 (1029/930) | M | 44 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| PARK2 | Del ex 7 | - | Het | - | - | ||||||||||

| EP-22 | PARK2 | c.1205G>A | p.Arg402His | Het | 0.512 | 1256 (643/613) | M | 40 | No | Yes (12) | Yes (13) | Yes (10) | No | No | No |

| PARK2 | Del ex 7 | - | Het | - | - | ||||||||||

| EP-23 | PARK2 | Del ex 3 | - | Hom | - | - | F | 33 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| EP-24 | PARK2 | Del ex 3-4-5-6 | - | Hom | - | - | M | 34 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| EP-25 | PARK2 | Del ex 3-4-5-6 | - | Hom | - | - | F | 47 | Yes | Yes (9) | Yes (7) | - | - | - | - |

| EP-26 | PARK2 | c.1334G>A | p.Trp445Stop | Het | 0.520 | 321 (167/154) | F | 34 | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| PARK2 | Del ex 3-4-5-6 | - | Het | - | - | ||||||||||

| EP-27 | LRRK2 | c.6055G>A | p.Gly2019Ser | Het | 0.442 | 981 (434/547) | M | 29 | No | Yes (3) | Yes (4) | No | No | No | No |

| EP-28 | LRRK2 | c.6055G>A | p.Gly2019Ser | Het | 0.393 | 1011 (397/614) | M | 40 | Yes | Yes (12) | No | No | No | No | No |

| EP-29 | LRRK2 | c.6055G>A | p.Gly2019Ser | Het | 0.442 | 1025 (453/572) | F | 39 | No | Yes (4) | Yes (5) | - | No | No | No |

| EP-30 | LRRK2 | c.6055G>A | p.Gly2019Ser | Het | 0.369 | 1154 (426/728) | F | 42 | No | Yes (1) | Yes (1) | - | No | No | No |

| EP-31 | LRRK2 | c.6055G>A | p.Gly2019Ser | Het | 0.419 | 1046 (438/608) | F | 40 | No | Yes (2) | Yes (2) | Yes (2) | No | No | No |

| EP-32 | LRRK2 | c.4321C>T | p.Arg1441Cys | Het | 0.524 | 708 (371/337) | M | 45 | No | Yes (4) | Yes (5) | Yes (4) | No | No | No |

| EP-33 | LRRK2 | c.4536+3A>G | - | Het | 0.460803 | 523 (241/282) | M | 45 | Yes | Yes | Yes | - | No | Yes | No |

| GIGYF2 | c.3673C>T | p.Arg1225Cys | Het | 0.500606 | 825 (413/412) | ||||||||||

| EP-34 | SMPD1 | c.1132C>T | p.Arg378Cys | Het | 0.500808 | 1857 (930/927) | F | 46 | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

HGVS: Human Genome Variation Society (Variants have been described using HGVS nomenclature). CDS: Coding sequence. AA: Amino acid. Het: Heterozygous. Hom: Homozygous. VAF: Variant allele frequency. Alt: Alternate allele. Ref: Reference allele. M: Male. F: Female. MF: Motor fluctuations. NMF: Non-motor fluctuations. DK: Dyskinesia. AAOS: Age at onset of symptom. CI: Cognitive impairment. VH: Visual hallucinations.

Findings in PD-associated genes

Twenty-six patients carried likely pathogenic variants in PARK2, LRRK2, PINK1, or GBA.

PARK2 was the gene most frequently mutated (Fig 3; Table 2). Therefore, 16 patients presented pathogenic variants in PARK2, 8 of them carried deletions of entire exons of PARK2. The most often pathogenic variant in PARK2 was a previously described frameshift variation (p.Asn52Metfs*29). To the best of our knowledge, all carriers for this variation are unrelated patients.

Seven patients carried previously described pathogenic variations in LRRK2. Of them, 5 patients carried the variation p.Gly2019Ser, 1 patient carried the variation p.Arg1441Cys, and 1 patient carried the intronic variation c.4536+3A>G.

No significant difference (P = 0.205) was shown between age at onset of patients with pathogenic variants in LRRK2 (age at onset 40.1±5.6 years old) and those with pathogenic variants in PARK2 (age at onset 36.7±5.7 years old).

We found one patient carrying a homozygous pathogenic variant in PINK1 (p.Leu347Pro) and another patient with a heterozygous pathogenic variant in VPS35 (p.Ala654Ser). Therefore, variations in these genes are a rare cause of disease in our population.

Finally, two patients carried two non-previously described likely pathogenic variants in GBA (p.Ile347Thr and p.Ser403Asn).

No pathogenic variant was observed in SNCA, and PARK7, illustrating their rarity in our population.

Findings in other genes

A total of 6 variants in ATP13A2 (p.Gly217Ser, p.Arg745His; and c.2762+21T>C), GIGYF2 (p.Arg1225Cys), and SMPD1 (p.Val147Val and p.Arg378Cys), were found as putatively contributing to PD (Table 2).

Pathogenic variants were not observed in EIF4G1, SYNJ1, FBXO7, DNAJC6, PLA2G6, HTRA2, and UCHL1.

Discussion

In this study, a pipeline, based on a combination of a next-generation sequencing panel of 17 genes and MLPA, has been applied to detect PD-related variations in a Caucasian population with EOPD from Central Spain. Twenty-seven patients out of 117 (23.08%) showed likely pathogenic variants in known PD-associated genes.

Pathogenic variants in the PARK2 gene were the most common genetic cause of early-onset ARPD, with a variable prevalence in previous studies in EOPD [12–14]. Therefore, PARK2 variants were the most frequently identified explanation for PD in our cohort also (13.68%; 16 patients out of 117); with the most frequent pathogenic variant (6.4%; 15/234) being a previously described frameshift variation (p.Asn52Metfs*29) [15]. This result is different in comparison to a study with PD patients from northern Spain, which described this variation, in homozygous, in one patient from a population of 72 EOPD patients (1.4%; 2/144) [16]. However, in another previous study, that variation was found in 2 patients (in a homozygous and heterozygous state) from a 26 EOPD patient cohort (5.8%; 3/52) from southern Spain [17], similar to what it was obtained in our population. Those results suggest that, although p.Asn52Metfs*29 is geographically widespread, it is less prevalent in the Basque Country and it could be associated with a founder effect and subsequent dispersion of the variation.

Interestingly, one patient (EP-17) to be carrying the pathogenic variation p.Asn52Metfs*29 in PARK2 in a homozygous state, also carried a variation in ATP13A2 (c.2762+21T>C), which was predicted by the bioinformatic tools as affecting splicing due the apparition of a stronger cryptic 5' donor site. This patient had an age at onset that was younger than the other carriers of the same variation p.Asn52Metfs*29, suggesting a cumulative effect between both genes on age at onset. The ATP13A2 gene has been found mutated in some types of early-onset Parkinsonism [18]. Although the pathogenicity of single heterozygous variations is a matter of debate, the reduction of functional ATP13A2 has been related to the development of PD as a risk factor. Moreover, it has been suggested that dopaminergic neurons expressing higher ATP13A2 protein levels are less susceptible to cell death [19]. Given the rarity of ATP13A2 pathogenic variations, confirmation of this point will require sequencing of much larger sample sizes.

On the other hand, to date, pathogenic variations in LRRK2 (a multi-domain protein with both GTPase and kinase functionality) are the most common genetic determinant of ADPD. The most frequent pathogenic variation described is p.Gly2019Ser, although its prevalence varies considerably [17, 20, 21]. We found this variation in 5 patients, which represents the 4.27% of the 117 studied samples. This frequency is consistent with the prevalence in Caucasians. In total, in this study 6.84% of the studied patients carried pathogenic variants in LRRK2. Therefore, our results provide a very important role for LRRK2 in typical EOPD in our Spanish population. This is according with recent studies in other populations, such a large UK population based study where it has been shown that LRRK2 mutations are present at a significant rate in patients under 50 years [22].

Pathogenic variants in the GIGYF2 gene have been related to familial PD [5], but some studies in diverse populations showed that there is no correlation between the presence of variants in this gene with the disease [23–25]. In this analysis, we found a patient (EP-33) with co-occurrence of c.4536+3A>G (predicted affecting splicing) in LRRK2 and p.Arg1225Cys in GIGYF2 pathogenic variants. This patient presented cognitive impairment, as previously described in a Spanish family featuring late-onset PD and cognitive impairment and with a genetic variant, in GIGYF2, identified as potential disease-causing variation [26]. It is interesting to note that both genes (LRRK2 and GIGYF2) have been described as playing some roles in the autophagy process [27]. As such, this kind of co-occurrence involving both genes has been previously described and associated with an earlier age at onset of PD, suggesting additive effects [5]. Further genetic studies and functional analysis are necessary to conclude the implications in PD of variants located in GIGYF2.

In any case, although these two cases could indicate a modifying effect, this cannot be determinate in this study, as this is still on an exploratory level.

Among risk factors in PD, GBA is well known [28]. Variantss in this gene are present in multiple ethnicities [29]. Heterozygous pathogenic variants are dominantly inherited, and the penetrance is high, related to EOPD [30]. Importantly, the frequency of GBA pathogenic variants in our population is rather low. Indeed, our GBA mutational spectrum did not include the most frequent pathogenic variants L444P and N370S [31]. Technical reasons or variant filtering could explain this. Therefore, GBA sequencing using targeted next generation sequencing is difficult because the existence of the pseudo-GBA, with very similar sequence. In addition, it has been shown that GBA variants have a different impact on the PD phenotype according to their pathogenicity (both deleterious and benign). Because of preselecting for pathogenic, likely pathogenic or VOUS (variant of unknown significance) variants, it may very well be an underestimate of the true yield of variants in GBA affecting Parkinson’s disease in our population.

This study focused on exonic and intronic variants; however, most of the variants found were located in the untranslated regions (mainly in 3’UTR). Interestingly, heterozygous pathogenic variants in recessive genes were detected in some patients that also presented variants in untranslated regions. Therefore, it will be important to perform further deeper analysis in order to study their contribution to disease pathogenesis.

Finally, although Pool-seq is a cost-effective alternative to individual sequencing, there are some limitations to consider; in particular, the presence of false positives and/or false negatives. It has been described that the accuracy of Pool-seq increases with the number of individuals included in the pool and with a high sequencing depth [32, 33]. However, increasing sequencing depth could give rise to other problems, such as to confound sequencing errors with very rare alleles that could lead to an increase of the false positive rate. We think that our approach using, among others, a high number of individuals included in each pool, a high depth of coverage, and a threshold on the minimum percentage of reads of alternative alleles, minimizes the errors and produces data with satisfactory precision and accuracy.

Conclusions

This study, in terms of cohort size, number of included genes and applied methods is the first systematic study of genetic variability in PD-related genes in EOPD patients from Spain. Our results provide a comprehensive genetics profile of EOPD. In addition, further evidence for gene interaction involving ATP13A2 and PARK2, and LRRK2 and GIGYF2, are provided with co-occurrence of pathogenic variations in both genes. Moreover, our study suggests a greater role for LRRK2 in typical, idiopathic EOPD than previously believed in the Spanish population. Thus, our results could weight utility in personalized genetic counselling.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(PDF)

Nonsense variants and those missense variants which were predicted as likely pathogenic by at least 53’9% (seven of thirteen) of the bioinformatics tools.

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank patients who participated in this study. We also thank Raquel Gómez (Multiple Uses Laboratory), and Juan Antonio Cordero (Bioinformatic and Computational Biology Service), both of them from the Instituto de Biomedicina de Sevilla (IBiS), for their technical support, and the HUVR-IBiS Biobank (Andalusian Public Health System Biobank and ISCIII-Red de Biobancos PT13/0010/0056) for the human specimens used in this study.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by grants from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness [PI14/01823, PI16/01575, PI18/01898] co-founded by ISCIII (Subdirección General de Evaluación y Fomento de la Investigación) and by Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER), the Consejería de Economía, Innovación, Ciencia y Empleo de la Junta de Andalucía [CVI-02526, CTS-7685], the Consejería de Salud y Bienestar Social de la Junta de Andalucía [PI-0437-2012, PI-0471-2013], the Sociedad Andaluza de Neurología, the Fundación Alicia Koplowitz, the Fundación Mutua Madrileña. Pilar Gómez-Garre was supported by the "Miguel Servet" (from ISCIII-FEDER) and “Nicolás Monardes” (from Andalusian Ministry of Health) programs. Silvia Jesús Maestre was supported by the "Juan Rodés" program (from ISCIII-FEDER). Cristina Tejera was supported by VPPI-US from the Universidad de Sevilla. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Polymeropoulos MH, Lavedan C, Leroy E, Ide SE, Dehejia A, Dutra A, et al. Mutation in the alpha-Synuclein Gene Identified in Families with Parkinson's Disease. Science. 1997;276(5321):2045–7. 10.1126/science.276.5321.2045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paisan-Ruiz C, Jain S, Evans EW, Gilks WP, Simon J, van der Brug M, et al. Cloning of the gene containing mutations that cause PARK8-linked Parkinson's disease. Neuron. 2004;44(4):595–600. 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.023 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimprich A, Benet-Pages A, Struhal W, Graf E, Eck SH, Offman MN, et al. A mutation in VPS35, encoding a subunit of the retromer complex, causes late-onset Parkinson disease. American journal of human genetics. 2011;89(1):168–75. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonifati V. Genetics of Parkinson's disease–state of the art, 2013. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. 2014;20:S23–S8. 10.1016/s1353-8020(13)70009-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lautier C, Goldwurm S, Durr A, Giovannone B, Tsiaras WG, Pezzoli G, et al. Mutations in the GIGYF2 (TNRC15) gene at the PARK11 locus in familial Parkinson disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82(4):822–33. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.01.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, Sun QY, Yu RH, Guo JF, Tang BS, Yan XX. The contribution of GIGYF2 to Parkinson's disease: a meta-analysis. Neurol Sci. 2015;36(11):2073–9. 10.1007/s10072-015-2316-9 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trinh J, Farrer M. Advances in the genetics of Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9(8):445–54. 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.132 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang D, Nalls MA, Hallgrimsdottir IB, Hunkapiller J, van der Brug M, Cai F, et al. A meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies 17 new Parkinson's disease risk loci. Nat Genet. 2017;49(10):1511–6. 10.1038/ng.3955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibb W, Lee A. The relevance of the Lewy body to the pathogenesis of idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 1988;51(6):745–52. 10.1136/jnnp.51.6.745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genetics in medicine: official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2015;17(5):405–24. 10.1038/gim.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pugh TJ, Amr SS, Bowser MJ, Gowrisankar S, Hynes E, Mahanta LM, et al. VisCap: inference and visualization of germ-line copy-number variants from targeted clinical sequencing data. Genet Med. 2016;18(7):712–9. 10.1038/gim.2015.156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Macedo MG, Verbaan D, Fang Y, van Rooden SM, Visser M, Anar B, et al. Genotypic and phenotypic characteristics of Dutch patients with early onset Parkinson's disease. Movement Disorders. 2009;24(2):196–203. 10.1002/mds.22287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koziorowski D, Hoffman-Zacharska D, Sławek J, Jamrozik Z, Janik P, Potulska-Chromik A, et al. Incidence of mutations in the PARK2, PINK1, PARK7 genes in Polish early-onset Parkinson disease patients. Neurologia i Neurochirurgia Polska. 2013;47(4):319–24. 10.5114/ninp.2013.36756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alcalay RN, Caccappolo E, Mejia-Santana H, Tang MX, Rosado L, Ross BM, et al. Frequency of known mutations in early-onset Parkinson disease: implication for genetic counseling: the consortium on risk for early onset Parkinson disease study. Archives of neurology. 2010;67(9):1116–22. 10.1001/archneurol.2010.194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spataro N, Roca-Umbert A, Cervera-Carles L, Valles M, Anglada R, Pagonabarraga J, et al. Detection of genomic rearrangements from targeted resequencing data in Parkinson's disease patients. Mov Disord. 2017;32(1):165–9. 10.1002/mds.26845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorostidi A, Marti-Masso JF, Bergareche A, Rodriguez-Oroz MC, Lopez de Munain A, Ruiz-Martinez J. Genetic Mutation Analysis of Parkinson's Disease Patients Using Multigene Next-Generation Sequencing Panels. Mol Diagn Ther. 2016;20(5):481–91. 10.1007/s40291-016-0216-1 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bandres-Ciga S, Mencacci NE, Duran R, Barrero FJ, Escamilla-Sevilla F, Morgan S, et al. Analysis of the genetic variability in Parkinson's disease from Southern Spain. Neurobiology of aging. 2016;37:210 e1–5. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.09.020 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramirez A, Heimbach A, Grundemann J, Stiller B, Hampshire D, Cid LP, et al. Hereditary parkinsonism with dementia is caused by mutations in ATP13A2, encoding a lysosomal type 5 P-type ATPase. Nat Genet. 2006;38(10):1184–91. 10.1038/ng1884 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ysselstein D, Shulman JM, Krainc D. Emerging links between pediatric lysosomal storage diseases and adult parkinsonism. Mov Disord. 2019. 10.1002/mds.27631 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lill CM. Genetics of Parkinson's disease. Molecular and cellular probes. 2016;30(6):386–96. 10.1016/j.mcp.2016.11.001 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hernandez DG, Reed X, Singleton AB. Genetics in Parkinson disease: Mendelian versus non-Mendelian inheritance. J Neurochem. 2016;139 Suppl 1:59–74. 10.1111/jnc.13593 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan MMX, Malek N, Lawton MA, Hubbard L, Pittman AM, Joseph T, et al. Genetic analysis of Mendelian mutations in a large UK population-based Parkinson's disease study. 2019;142(9):2828–44. 10.1093/brain/awz191 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bras J, Simon-Sanchez J, Federoff M, Morgadinho A, Januario C, Ribeiro M, et al. Lack of replication of association between GIGYF2 variants and Parkinson disease. Human molecular genetics. 2009;18(2):341–6. 10.1093/hmg/ddn340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guella I, Pistocchi A, Asselta R, Rimoldi V, Ghilardi A, Sironi F, et al. Mutational screening and zebrafish functional analysis of GIGYF2 as a Parkinson-disease gene. Neurobiology of aging. 2011;32(11):1994–2005. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.12.016 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonetti M, Ferraris A, Petracca M, Bentivoglio AR, Dallapiccola B, Valente EM. GIGYF2 variants are not associated with Parkinson's disease in Italy. Movement Disorders. 2009;24(12):1867–8. 10.1002/mds.22640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruiz-Martinez J, Krebs CE, Makarov V, Gorostidi A, Marti-Masso JF, Paisan-Ruiz C. GIGYF2 mutation in late-onset Parkinson's disease with cognitive impairment. J Hum Genet. 2015;60(10):637–40. 10.1038/jhg.2015.69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim M, Semple I, Kim B, Kiers A, Nam S, Park HW, et al. Drosophila Gyf/GRB10 interacting GYF protein is an autophagy regulator that controls neuron and muscle homeostasis. Autophagy. 2015;11(8):1358–72. 10.1080/15548627.2015.1063766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jesus S, Huertas I, Bernal-Bernal I, Bonilla-Toribio M, Caceres-Redondo MT, Vargas-Gonzalez L, et al. GBA Variants Influence Motor and Non-Motor Features of Parkinson's Disease. PloS one. 2016;11(12):e0167749 10.1371/journal.pone.0167749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sidransky E, Nalls MA, Aasly JO, Aharon-Peretz J, Annesi G, Barbosa ER, et al. Multicenter analysis of glucocerebrosidase mutations in Parkinson's disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;361(17):1651–61. 10.1056/NEJMoa0901281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferreira M, Massano J. An updated review of Parkinson's disease genetics and clinicopathological correlations. Acta neurologica Scandinavica. 2016. 10.1111/ane.12616 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao F, Bi L, Wang W, Wu X, Li Y, Gong F, et al. Mutations of glucocerebrosidase gene and susceptibility to Parkinson's disease: An updated meta-analysis in a European population. Neuroscience. 2016;320:239–46. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.02.007 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schlötterer C, Tobler R, Kofler R, Notle V. Sequencing pools of individuals-mining genome-wide polymorphism data without big funding. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:749–63. 10.1038/nrg3803 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fracassetti M, Griffin PC, Willi Y. Validation of pooled whole-genome re-sequencing in Arabidopsis lyrata. PloS One.2015;10(10):e0140462 10.1371/journal.pone.0140462 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(PDF)

Nonsense variants and those missense variants which were predicted as likely pathogenic by at least 53’9% (seven of thirteen) of the bioinformatics tools.

(PDF)

(PDF)

(PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.