Abstract

α-Branched amines are present in hundreds of pharmaceutical agents and clinical candidates and are important targets for synthesis. Here we show the convergent synthesis of α-branched amines from three readily accessible starting materials: aromatic C–H bond substrates, terminal alkenes, and aminating agents. This reaction proceeds by an intermolecular formation of C–C and C–N bonds at the sp3 carbon branch site through an uncommon 1,1-alkene addition pathway. The reaction is carried out under mild conditions and has high functional group compatibility. Ethylene and propylene feedstock chemicals are effective alkene inputs with ethylene in particular providing for the one step synthesis of α-methyl branched amines, a motif prevalent in drug structures. The reaction is scalable, and 1% loading of an air stable dimeric rhodium precatalyst is effective for several different types of products. The use of chiral catalysts also enables the asymmetric synthesis of α-branched amines.

Graphical Abstract

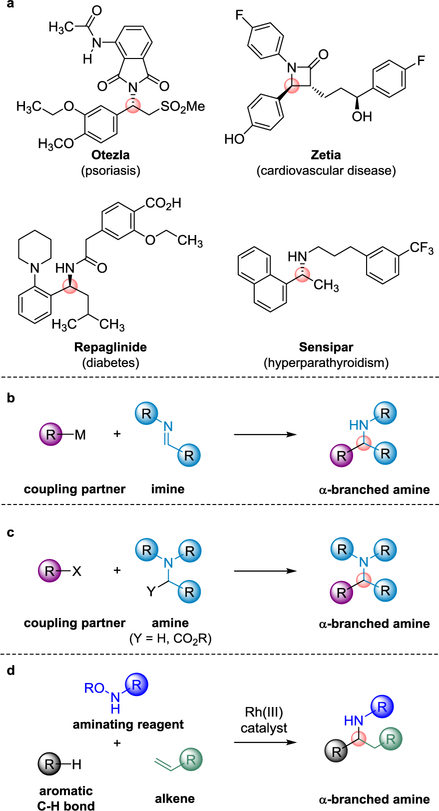

α-Branched amines displaying an exceedingly broad range of functionality have been incorporated into many approved pharmaceuticals and clinical candidates (Fig. 1a)1–7. The synthesis of α-branched amines by formation of a C–C bond at the sp3 carbon branch site is strategic because it enables a convergent preparation from smaller precursors with simultaneous introduction of a stereogenic centre8. Indeed, one of the most powerful approaches for the preparation of this class of compound is the addition of nucleophiles such as organometallic reagents to imines, with new methods for catalysing this process continuing to be developed (Fig. 1b)9–16. Recently, C–C bond formation at the α-position of a preexisting amine has been applied to the synthesis of α-branched amines also with simultaneous introduction of a stereocentre at the branch site (Fig. 1c)17–20.

Fig. 1. α-Branched amines.

a, Representative examples of hundreds of approved pharmaceuticals that contain α-branched amine motifs (branch site highlighted by pink spheres). b, α-Branched amine synthesis with C–C bond formation at the branch site by addition of organometallic reagents to imines. c, α-Branched amine synthesis with C–C bond formation at the branch site from preexisting amines. d, Single step method to form α-branched amines from readily available C–H bond substrates, alkenes and aminating agents with formation of both C–C and C–N bonds at the branch site.

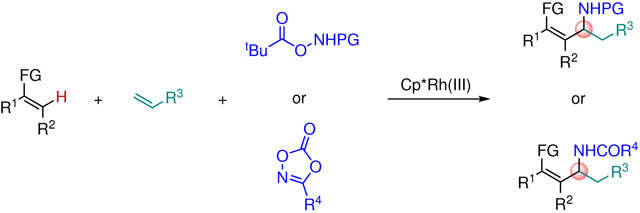

We sought a new approach for the synthesis of α-branched amines by simultaneous C–C and C–N bond formation at the branch site from three rather than two inputs, specifically, readily available C–H bond substrates, aminating agents, and alkenes (Fig. 1d). Because the approach does not involve organometallic reagents and should not require strongly acidic or basic conditions, we anticipated that it would be compatible with functionalities present in pharmaceuticals that interfere with many of the other C–C bond forming reactions for α-branched amine synthesis. However, to implement this method, a new mode of catalysis needed to be developed for the ordered intermolecular 1,1-addition of a C–H bond and an aminating agent to the C–C π-bond of an alkene. The requisite 1,1-addition pathway is in stark contrast to much more common 1,2-additions with a bond formed at each carbon of the reacting C–C π-bond21,22.

Herein we report the synthesis of α-branched amines by Cp*Rh(III)-catalysed 1,1-addition of C–H bonds and aminating agents to terminal alkenes. Different aminating agents were used to directly prepare α-branched amines protected with the common Boc, Cbz, Fmoc and toluenesulfonyl protecting groups and also as alkyl, aryl and heteroaryl amide derivatives. In addition to terminal alkenes displaying a large variety of functionality, the bulk chemical feedstocks ethylene and propylene were also effective inputs. For several different α-branched amine products, a 1% loading of an air stable dimeric rhodium precatalyst was effective, and at this catalyst loading, the reaction was shown to be scalable. The asymmetric synthesis of α-branched amines was also achieved with chiral catalysts. Finally, through information obtained from reactions with isotopically labelled substrates, we propose a mechanism that explains the uncommon 1,1-alkene addition observed for this three-component transformation.

Results

Optimization studies.

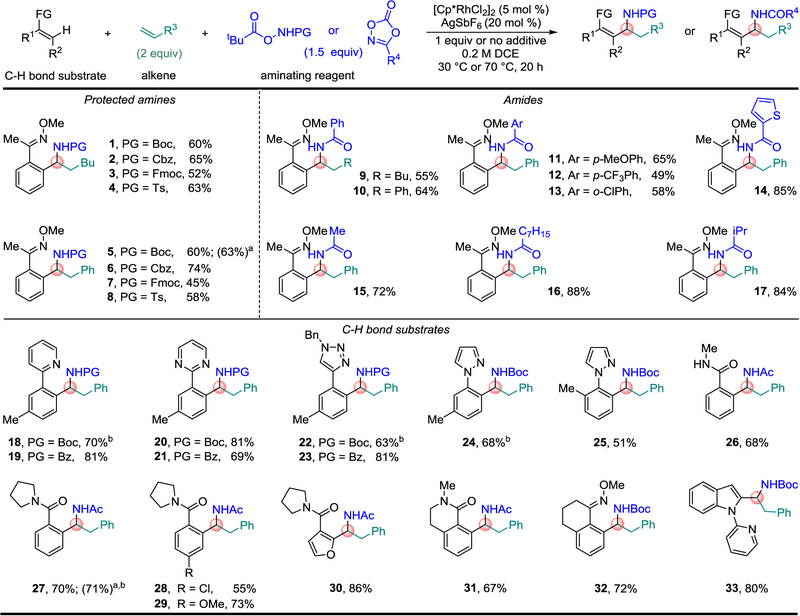

Two types of aminating agents were carefully chosen to provide useful derivatives of α-branched amine products (Fig. 2). O-Acyl hydroxamic acids were selected to give the carbamates and sulfonamides that represent the most extensively used protected amine classes and can be readily cleaved to access free amines23–25. Dioxazolones were selected to directly provide diverse amides given that a high percentage of α-branched amines present in drugs and drug candidates are incorporated within amide structures25,26.

Fig. 2. Aminating agent and C–H bond substrate scope for α-branched amine synthesis.

Reactions were performed on 0.3 mmol scale at [0.2 M] with respect to C–H bond substrates. Ratio of C–H bond substrate: aminating agent: alkene (1:1.5:2). One equivalent of NaHCO3 was used as an additive for oxime C–H bond substrates and one equivalent of pivalic acid (PivOH) was used as an additive for triazole and amide C–H bond substrates. Isolated yields of product after purification by chromatography are reported. See Supplementary Methods for experimental details. a Reactions performed with 1 mol % of [Cp*RhCl2]2 and 4 mol % of AgSbF6. b Reactions performed at 70 °C.

To optimize the reaction, we focused on the preparation of α-branched amine 1 protected with the most popular and extensively used tert-butyloxycarbonyl (Boc) protecting group (Fig. 2). A cationic Cp*Rh(III) catalyst was determined to be the most effective after extensive investigation of a number of different transition metal catalysts and variations of reaction parameters (see Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Under the optimal reaction conditions, [Cp*RhCl2]2 was employed as an air and water stable precatalyst with AgSbF6 as the halide abstracting agent. The reaction was performed at 0.2 M in the limiting C–H bond substrate with dichloroethane (DCE) as solvent at 30 °C. For oxime C–H bond substrates the addition of one equivalent of NaHCO3 resulted in 10–15% higher yields than the reaction performed in the absence of the additive. However, for amide and triazole C–H bond substrates, pivalic acid (PivOH) was found to be a more effective additive27. Significantly, undesired 1,2-addition products were not observed.

Scope and limitations of the reaction.

The transformation could be broadly applied to the direct, one-step preparation of α-branched amines protected with other common amine protecting groups (Fig. 2, 1-4). In addition to α-branched amine 1 protected with the acid labile Boc-group, we also prepared amine 2 protected with the hydrogenolytically labile carbobenzoxy (Cbz) group, amine 3 protected with the base labile 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc) group, and amine 4 protected with the robust toluenesulfonyl (Ts) group.

We next explored styrene as the alkene, which provided protected amines 5-8 in comparable yields to that observed for hexene as the alkene input. While the stabilizing nature of the phenyl substituent in styrene might be expected to facilitate formation of 1,2-addition products, only the desired α-branched amine product resulting from 1,1-addition was observed. Although the scope of the reaction was broadly explored with 5 mol % of the [Cp*RhCl2]2 precatalyst, much lower catalyst loadings could be used in some cases. Indeed, when only 1 mol % of [Cp*RhCl2]2 and 4 mol % of AgSbF6 were employed at a 1 M concentration in the limiting C–H bond substrate, N-Boc amine 5 was obtained in 63% isolated yield, which compares favorably to the 60% yield obtained at 5 mol % catalyst loading.

To directly obtain diverse α-branched amide derivatives in a single step, 1,4,2-dioxazol-5-ones were used as the aminating agents (9-17). By using different 1,4,2-dioxazol-5-ones, aromatic and heteroaromatic amides as well as linear and branched alkyl amides were prepared.

An attractive feature of the approach presented here is the opportunity to vary all three inputs to obtain a broad range of α-branched amine products. This beneficial aspect was highlighted by successful inclusion of different C–H bond substrates. Commonly encountered nitrogen heterocycles such as pyridine (18 and 19), pyrimidine (20 and 21), triazole (22 and 23) and pyrazole (24 and 25) were effective directing groups to provide the desired α-branched amines. For the pyrazole directing group, an example of a sterically challenging ortho-substituted arene was investigated and coupled efficiently to give 25. Interestingly, both secondary (26) and tertiary (27–31) amides were also effective directing groups. For amide product 27 the yield was maintained at 1 mol % precatalyst simply by increasing the reaction temperature to 70 °C. The synthesis of α-branched amine 30 is notable because it required activation of a heteroaromatic C–H bond, and amine product 31 is of interest as an example of a fused bicyclic amide motif. Branched amines were also obtained in good yields for a related fused bicyclic oxime (32) and for the fused heterocycle N-pyrimidinyl indole (33).

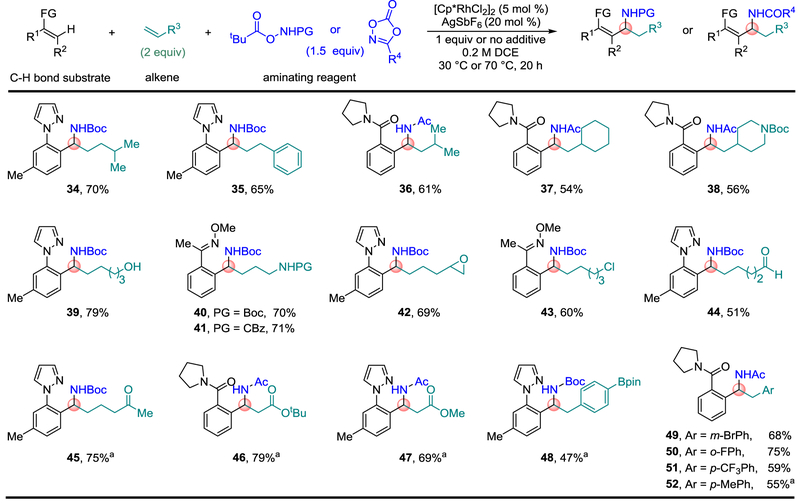

The broad availability and low cost of terminal alkenes enables straightforward introduction of diverse functionality (Fig. 3). A β-branched alkene (34), allylbenzene (35), and sterically more demanding α-branched alkenes (36 to 38) provided the desired products under the standard conditions. The reaction showed very broad functional group compatibility, including for acidic primary alcohol (39) and carbamate (40 and 41) functionality, and for electrophilic epoxide (42), primary alkyl halide (43), aldehyde (44), ketone (45) and ester (46 and 47) functionality. Many of these functional groups are not compatible with the organometallic reagents that have traditionally been used for imine additions (see Fig. 1b). It is also notable that the highly electron deficient α,β-unsaturated acrylate esters are effective alkene inputs with only the 1,1-addition products, β-amino esters 46 and 47, obtained despite the potential for stabilization of 1,2-addition intermediates by the ester group28. Styrenes substituted at the para-, meta- and ortho-positions also provided the desired products (48 to 52), including for organoboron (48) and bromo (49) substituted products amenable to further elaboration by cross-coupling. Not all of the alkenes that were investigated were effective inputs. For example, vinyl chlorides and ethers and a variety of disubstituted alkenes did not undergo three-component addition (Supplementary Figure 1 depicts unsuccessful alkene inputs).

Fig. 3. Alkene scope for the modular synthesis of α-branched amines.

Reactions were performed on 0.3 mmol scale at [0.2 M] with respect to C–H bond substrates. Ratio of C–H bond substrate: aminating agent: alkene (1:1.5:2). One equivalent of NaHCO3 was used as an additive for oxime C–H bond substrates and one equivalent of pivalic acid (PivOH) was used as an additive for amide C–H bond substrates. Isolated yields of product after purification by chromatography are reported. See Supplementary Methods for experimental details. a Reactions performed at 70 °C.

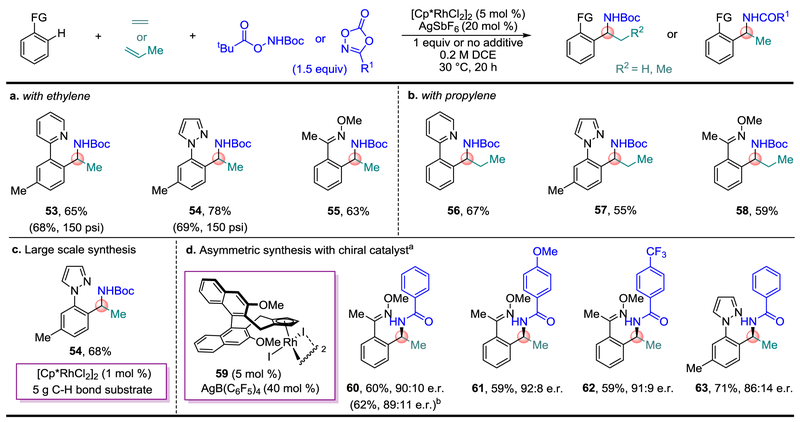

Use of Feedstock Alkenes.

The bulk commodity chemicals ethylene and propylene are also effective inputs and can readily be introduced to the reaction flask simply by sparging these gaseous alkenes over several minutes (Fig. 4a and b)29. Ethylene is particularly useful because it provides α-methyl branched amines (Fig. 4a), a sub-class of α-branched amines present in many pharmaceuticals. For this reason, performing the reaction under a pressurized ethylene atmosphere, which is readily applicable to larger reaction scales, was also carried out (see 53 and 54). The scalability of this approach was demonstrated by the preparation of α-methyl branched amine 54 from 5 g of the C–H bond substrate at 1 M concentration with only 1 mol % loading of the precatalyst [Cp*RhCl2]2 (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4. Use of Feedstock Alkenes and Asymmetric Synthesis.

a and b, Synthesis of α-methyl and α-ethyl branched amines from the feedstock chemicals ethylene and propylene, respectively. c, Large scale (> 5 g) modular synthesis of Boc-protected α-methyl branched amine with 1 mol % [Cp*RhCl2]2 loading. d, Asymmetric catalysis with chiral catalyst 59. One equivalent of NaHCO3 was used as an additive for oxime C–H bond substrates. a Reactions performed on 0.05 mmol scale. b Reaction performed on 0.2 mmol scale.

Catalytic Asymmetric Reactions.

Given the recent advances in asymmetric C–H bond functionalization with chiral Rh(III) catalysis30–33, we also investigated a number of chiral catalysts for the asymmetric synthesis of α-methyl branched amines (see Supplementary Table 3). The Rh-complex 59 employing Cramer’s elegantly designed chiral ligand34, gave the most promising initial results with 86:14 to 92:8 enantiomer ratios obtained for α-methyl branched amines 60-63 incorporating different directing groups and both electron-poor and electron rich aromatic amides7 (Fig 4d).

Mechanistic Studies.

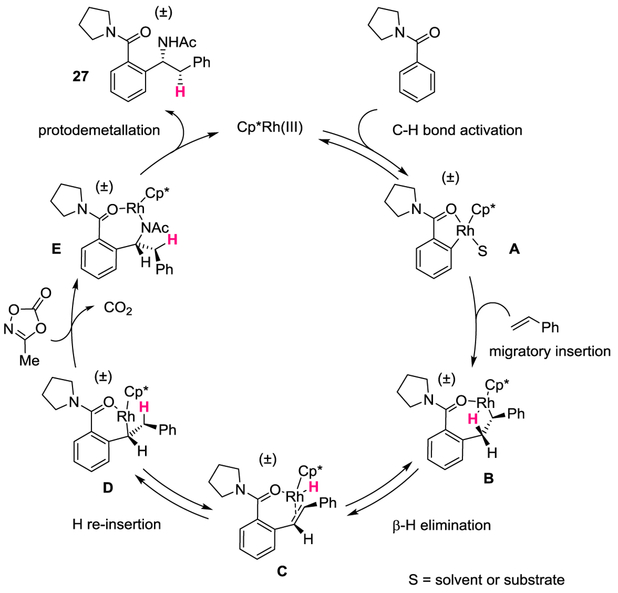

A catalytic cycle is proposed in Fig. 5 based upon the bond connectivity of the α-branched amine products and is supported by a series of mechanistic studies (Fig. 6a–d). The reaction is initiated by reversible ortho C–H bond activation by concerted metalation deprotonation to give A (See Supplementary Figure 2). Alkene coordination and subsequent migratory insertion leads to seven-membered rhodacycle B, which undergoes syn β-H elimination to generate alkene-bound Rh-H intermediate C. An exocyclic, syn H-reinsertion of the alkene generates six-membered rhodacycle D. Rigorous stoiochiometric studies on the related conversion of a seven- to a more stable six-membered Cp*Rh(III) rhodacycle via a β-H elimination and reinsertion sequence provide support of the proposed pathway from B to D35. Coordination of the amidating agent followed by C–N bond formation with retention of configuration and simultaneous release of CO2 provides the seven-membered rhodacycle E25. Subsequent protodemetallation leads to α-branched amine 27 while ensuring catalytic turnover.

Fig. 5. Proposed catalytic cycle.

The transformation proceeds through a reversible C–H bond activation (A), followed by migratory insertion into styrene to give B. Syn β-hydride elimination and hydride re-insertion lead to the species D, which coordinates with the dioxazolone and inserts into it to give E. Protodemetallation provides the product 27 and releases the Rh(III) species to maintain catalytic turnover.

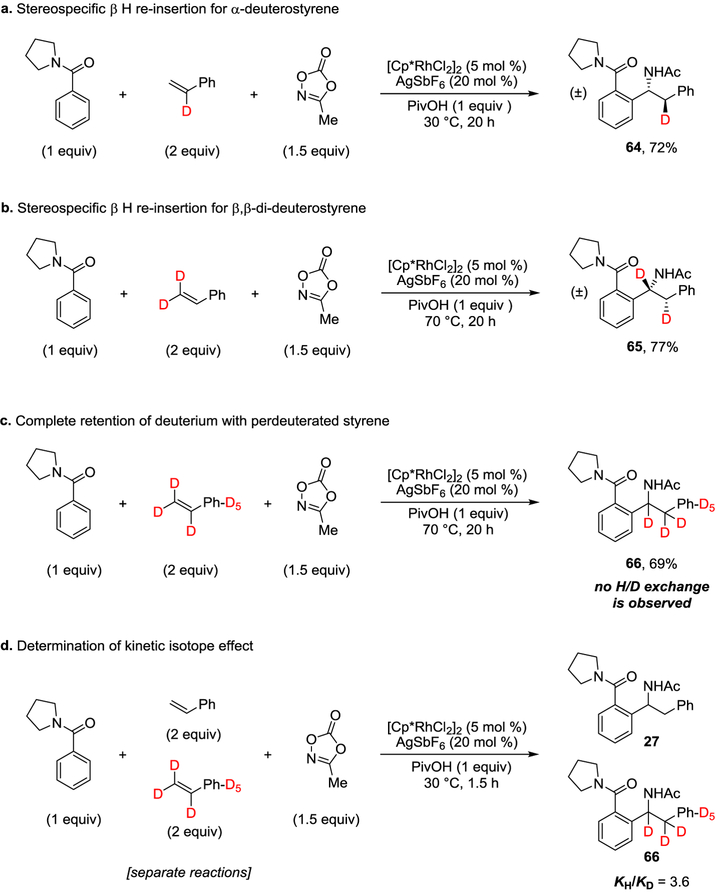

Fig. 6. Mechanistic experiments.

a, Stereospecific H re-insertion demonstrated with α-deuterostyrene. b, Stereospecific H re-insertion verified with β,β-dideuterostyrene. c, Migration of β-deuterium to the α-position with perdeuterated styrene. d, Relative initial rates of reactions with styrene and perdeuterated styrene.

The stereospecific nature of the β-H elimination, re-insertion and amidation steps were established by employing α-deuterostyrene, which provided 64 as a single stereo- and regioisomer (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Figure 3). The stereospecific nature of the reaction was further confirmed by employing β,β-di-deuterostyrene, which similarly provided 65 as a single stereo- and regioisomer (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Figure 4). When perdeuterated styrene was employed, intramolecular migration of deuterium to give 66 was observed consistent with the proposed β-hydride elimination and reinsertion steps (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Figure 5). However, this reaction proceeded more slowly with an extended reaction time or elevated temperature necessary to achieve high conversion to 66, suggesting that cleavage of a bond to deuterium might be involved in the rate determining step. Indeed, determination of the relative initial rates of reaction for styrene and perdeuterated styrene provided a kinetic isotope effect of KH/KD = 3.6, confirming that β-H elimination and/or reinsertion are rate determining step(s) for this reaction (Fig. 6d, Supplementary Figure 7, 8 and Supplementary Tables 4–6)36.

The interplay of all three components in the catalytic cycle is an essential feature of this transformation. When only two out of the three components are submitted to Rh(III) catalysis, different products result in each case. It is well-documented that reaction of the C–H bond substrate solely with an alkene results in C–H bond addition to the alkene14, whereas reaction solely with the dioxazolone results in C–H bond amidation25. Alkenes, including terminal alkenes, have also recently been reported to readily undergo Rh(III)-catalysed reaction with dioxazolones via allylic C–H insertion to give allylic amines37–39. Nevertheless, when all three of the components are present under appropriate conditions, reaction to give the α-branched amine product outcompetes all of the two component reactions.

Conclusion

In summary, we have described a multicomponent approach for the convergent synthesis of α-branched amines that proceeds under mild conditions from three readily accessible starting materials. The high functional group compatibility, potential for asymmetric synthesis, and scalability are additional desirable features. The complete selectivity for 1,1-addition regardless of the electronic properties of the alkene provides an avenue for the development of other intermolecular C–H bond addition reactions that proceed with this type of bond connectivity.

Methods

General procedure:

In a N2-filled glove box, a 2–5 mL microwave vial was charged with [Cp*RhCl2]2 (9.3 mg, 0.015 mmol, 0.050 equiv), AgSbF6 (21 mg, 0.060 mmol, 0.20 equiv), and, if indicated, an additive (0.300 mmol, 1 equiv). 1,2-Dicholoroethane (1.5 mL, 0.2 M) was added followed by the indicated C–H bond substrate (0.300 mmol, 1.0 equiv), alkene (0.600 mmol, 2 equiv), and amine substrate (0.450 mmol, 1.50 equiv). The reaction vial was equipped with a magnetic stir bar, sealed with a microwave cap, and taken outside the glove box. The reaction mixture was stirred at 30 or 70 °C in a preheated oil bath. After 20 h, the reaction mixture was allowed to cool to room temperature. The reaction mixture was filtered through a small celite plug, (1 cm long in a pipette), which was washed with ethyl acetate. The resulting mixture was then concentrated and purified by the corresponding chromatographic method to afford the desired product.

Data availability:

Much of the data that support the results of this study are available in the Supplementary Information. Additional data is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.. X-ray crystal data for structure 62 that established its absolute configuration is shown in Supplementary Figure 9, Supplementary Tables 7–13 and is available free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/) under reference number CCDC 1903974.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NIH (R35GM122473). We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Brandon Mercado (Yale University) for solving the crystal structure of 62 and Dr. Eric Paulson (Yale University) for stereochemical assignment of 64 using NMR methods.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables, Supplementary Figures, Supplementary Methods, Supplementary References.

Compound 62

Crystallographic data for compound 62.

References:

- 1.Maciejewski A et al. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, D1074–D1082 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nugent TC & El-Shazly M Chiral amine synthesis – recent developments and trends for enamide reduction, reductive amination, and imine reduction. Adv. Synth. Catal 352, 753–819 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 3.“Stereoselective formation of amines”: Topics in current chemistry, Vol. 343 (Eds.: Li W, Zhang X). Springer, Berlin: (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang Y, Shi S-L, Niu D, Liu P & Buchwald SL Catalytic asymmetric hydroamination of unactivated internal olefins to aliphatic amines. Science 349, 62–66 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blakemore DC et al. Organic synthesis provides opportunities to transform drug discovery. Nat. Chem 10, 383–394 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roizen JL, Harvey ME & Du Bois J Metal-catalyzed nitrogen-atom transfer methods for the oxidation of aliphatic C–H bonds. Acc. Chem. Res 45, 911–922 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou Y, Engl OD, Bandar JS, Chant ED & Buchwald SL CuH-Catalyzed asymmetric hydroamidation of vinylarenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 57, 6672–6675 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lovering F, Bikker J & Humblet C Escape from flatland: Increasing saturation as an approach to improving clinical success. J. Med. Chem 52, 6752–6756 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmidt F, Stemmler RT, Rudolph J & Bolm C Catalytic asymmetric approaches towards enantiomerically enriched diarylmethanols and diarylmethylamines. Chem. Soc. Rev 35, 454–470 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robak MT, Herbage MA & Ellman JA Synthesis and applications of tert-butanesulfinamide. Chem. Rev 110, 3600–3740 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsai AS, Tauchert ME, Bergman RG & Ellman JA Rhodium(III)-catalyzed arylation of Boc-imines via C−H bond functionalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc 133, 1248–1250 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Y et al. Rhodium-catalyzed direct addition of aryl C–H bonds to N-sulfonyl aldimines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 50, 2115–2119 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang Y, Perry IB & Buchwald SL Copper-catalyzed enantioselective addition of styrene-derived nucleophiles to imines enabled by ligand-controlled chemoselective hydrocupration. J. Am. Chem. Soc 138, 9787–9790 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hummel JR, Boerth JA & Ellman JA Transition-metal-catalyzed C–H bond addition to carbonyls, imines, and related polarized π bonds. Chem. Rev 117, 9163–9227 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heinz C et al. Ni-Catalyzed carbon–carbon bond-forming reductive amination. J. Am. Chem. Soc 140, 2292–2300 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trowbridge A, Reich D & Gaunt MJ Multicomponent synthesis of tertiary alkylamines by photocatalytic olefin-hydroaminoalkylation. Nature 561, 522–527 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McNally A, Prier CK & MacMillan DWC Discovery of an α-amino C–H arylation reaction using the strategy of accelerated serendipity. Science 334, 1114–1117 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zuo Z et al. Merging photoredox with nickel catalysis: Coupling of α-carboxyl sp3 carbons with aryl halides. Science 345, 437–440 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaw MH, Shurtleff VW, Terrett JA, Cuthbertson JD & MacMillan DWC Native functionality in triple catalytic cross-coupling: sp3 C–H bonds as latent nucleophiles. Science 352, 1304–1308 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jain P, Verma P, Xia G & Yu J-Q Enantioselective amine α-functionalization via palladium-catalysed C–H arylation of thioamides. Nat. Chem 9, 140 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liao L, Jana R, Urkalan KB & Sigman MS A palladium-catalyzed three-component cross-coupling of conjugated dienes or terminal alkenes with vinyl triflates and boronic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc 133, 5784–5787 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson HM, Williams BD, Miró J & Toste FD Enantioselective 1,1-arylborylation of alkenes: Merging chiral anion phase transfer with Pd Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 137, 3213–3216 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guimond N, Gorelsky SI & Fagnou K Rhodium(III)-catalyzed heterocycle synthesis using an internal oxidant: Improved reactivity and mechanistic studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc 133, 6449–6457 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel P & Chang S N-Substituted hydroxylamines as synthetically versatile amino sources in the iridium-catalyzed mild C–H amidation reaction. Org. Lett 16, 3328–3331 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park Y, Kim Y & Chang S Transition metal-catalyzed C–H amination: Scope, mechanism, and applications. Chem. Rev 117, 9247–9301 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park Y, Park KT, Kim JG & Chang S Mechanistic studies on the Rh(III)-mediated amido transfer process leading to robust C–H amination with a new type of amidating reagent. J. Am. Chem. Soc 137, 4534–4542 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lafrance M & Fagnou K Palladium-catalyzed benzene arylation: Incorporation of catalytic pivalic acid as a proton shuttle and a key element in catalyst design. J. Am. Chem. Soc 128, 16496–16497 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piou T & Rovis T Rhodium-catalysed syn-carboamination of alkenes via a transient directing group. Nature 527, 86–90 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weissermel K & Arpel HJ Olefins (Chapter 3), industrial organic chemistry. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 59–89 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ye B & Cramer N Chiral cyclopentadienyl ligands as stereocontrolling element in asymmetric C–H functionalization. Science 338, 504–506 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hyster TK, Knörr L, Ward TR & Rovis T Biotinylated Rh(III) complexes in engineered streptavidin for accelerated asymmetric C–H activation. Science 338, 500–503 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trifonova EA et al. A planar-chiral rhodium(III) catalyst with a sterically demanding cyclopentadienyl ligand and its application in the enantioselective synthesis of dihydroisoquinolones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 57, 7714–7718 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Satake S et al. Pentamethylcyclopentadienyl rhodium(III)–chiral disulfonate hybrid catalysis for enantioselective C–H bond functionalization. Nat. Catal 1, 585–591 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Newton CG, Kossler D & Cramer N Asymmetric catalysis powered by chiral cyclopentadienyl ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc 138, 3935–3941 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li L, Jiao Y, Brennessel WW & Jones WD Reactivity and regioselectivity of insertion of unsaturated molecules into M−C (M = Ir, Rh) bonds of cyclometalated complexes. Organometallics 29, 4593–4605 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simmons EM & Hartwig JF On the interpretation of deuterium kinetic isotope effects in C-H bond functionalizations by transition-metal complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 51, 3066–3072 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lei H & Rovis T Ir-Catalyzed Intermolecular Branch-Selective Allylic C–H Amidation of Unactivated Terminal Olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc 141, 2268–2273 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knecht T, Mondal S, Ye J-H, Das M & Glorius F Intermolecular, Branch-Selective, and Redox-Neutral Cp*IrIII-Catalyzed Allylic C−H Amidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 58, 7117–7121 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burman J, Harris R, Farr C, Bacsa J & Blakey SB Rh(III) and Ir(III)Cp* Complexes Provide Complementary Regioselectivity Profiles in Intermolecular Allylic C-H Amidation Reactions. ACS Catal., 9, 5474–5479 (2019). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Much of the data that support the results of this study are available in the Supplementary Information. Additional data is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.. X-ray crystal data for structure 62 that established its absolute configuration is shown in Supplementary Figure 9, Supplementary Tables 7–13 and is available free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/) under reference number CCDC 1903974.