Abstract

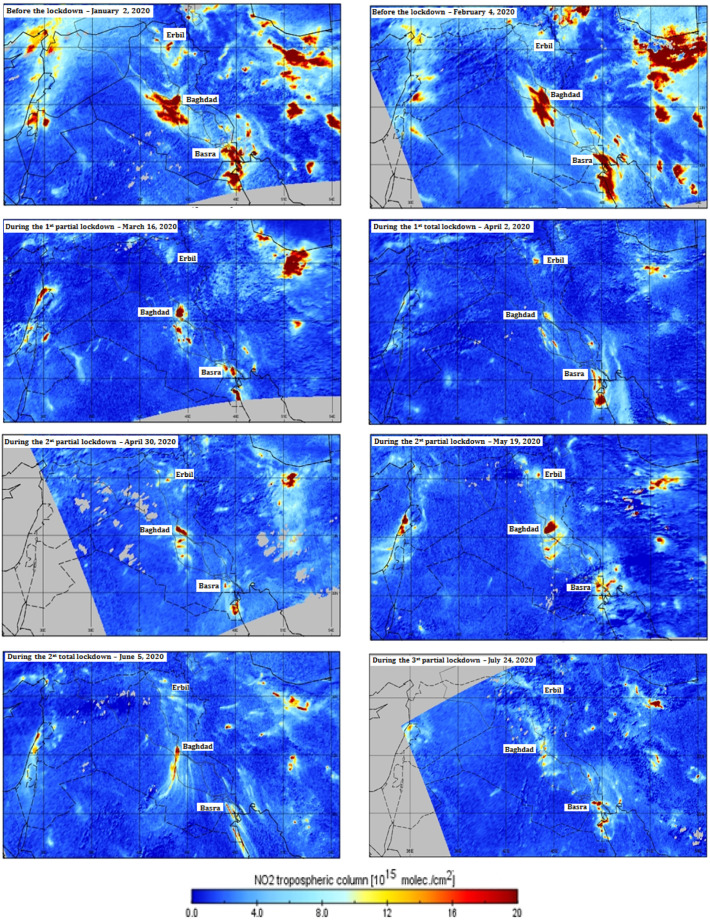

Covid-19 was first reported in Iraq on February 24, 2020. Since then, to prevent its propagation, the Iraqi government declared a state of health emergency. A set of rapid and strict countermeasures have taken, including locking down cities and limiting population's mobility. In this study, concentrations of four criteria pollutants, NO2, O3, PM2.5 and PM10 before the lockdown from January 16 to February 29, 2020, and during four periods of partial and total lockdown from March 1 to July 24, 2020, in Baghdad were analysed. Overall, 6, 8 and 15% decreases in NO2, PM2.5, and PM10 concentrations, respectively in Baghdad during the 1st partial and total lockdown from March 1 to April 21, compared to the period before the lockdown. While, there were 13% increase in O3 for same period. During the 2nd partial lockdown from June 14 to July 24, NO2 and PM2.5 decreases 20 and 2.5%, respectively. While, there were 525 and 56% increase in O3 and PM10, respectively for same period. The air quality index (AQI) improved by 13% in Baghdad during the 1st partial lockdown from March 1 to April 21, compared to its pre-lockdown. The results of NO2 tropospheric column extracted from the Sentinel-5P satellite shown the NO2 emissions reduced up to 35 to 40% across Iraq, due to lockdown measures, between January and July, 2020, especially across the major cities such as Baghdad, Basra and Erbil. The lockdown due to COVID-19 has drastic effects on social and economic aspects. However, the lockdown also has some positive effect on natural environment and air quality improvement.

Keywords: COVID-19, Lockdown, Air pollution, AQI, Iraq, TROPOMI

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

On December 31, 2019, China alerted the World Health Organization (WHO) of several cases of unusual pneumonia in Wuhan, a city in the central Hubei Province. On January 7, 2020, the identification of a new virus, named SARS-CoV-2, was announced (WHO, 2020a). On January 30, WHO declared worldwide public health emergency. In February, outbreaks begin in Iran, Italy and other countries around the globe. Subsequently, the epidemic turns into pandemic and by end of March half of the world population was under some form of lockdown (Tosepu et al., 2020). The recent outbreak of coronavirus disease, termed as COVID-19, has raised global concerns and led to total lockdown in many countries (WHO 2020a; Gautam and Trivedi, 2020; Bherwani et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). The disease is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus2 (SARS-CoV-2) (Gautam and Hens, 2020b). This fatal and novel coronavirus is likely to spread rapidly in humans with close contact to already infected people (Cascella et al., 2020; Bherwani et al., 2020). The spread of the virus may be contained by maintaining proper social distance, personal hygiene, avoiding gatherings, and visiting places like hospitals, meetings, and public transportations, which have a high risk of such virus contamination (WHO, 2020b; Bherwani et al., 2020; Gautam, 2020). Preliminary investigations on the origin of COVID-19 caused by the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus suggests a zoonotic origin (Lu et al., 2020) because other coronavirus- related diseases, such as Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) created outbreaks due to human–animal interactions.

COVID-19 is an acute respiratory disease which may lead to pneumonia with symptoms such as fever, cough and dyspnea (Jiang et al., 2020) and has an approximate fatality rate of 2–3% (Rodriguez-Morales et al., 2020). As of July 24, 2020, there have been more than 15 million confirmed cases and around 628,000 deaths reported globally (www.covid19.who.int, 2020). As the cases spread, most of the countries adopted restrictions to the transportation, commerce and cultural activities, schools and universities were closed and exams were cancelled, and social distancing was imposed (Dantas et al., 2020).

The first confirmed case of Virus COVID-19 in Iraq appeared on February 24, 2020 in Najaf, southern Baghdad (WHO, situation report-36). To control the spread of the COVID-19 in Iraq, the Iraqi government announced a series of partial and total lockdown measures from 1 March, which included closing schools, universities, restricting transportation and the movement of people between provinces (Jebril, 2020). The total number of confirmed cases in Iraq was 104,711 and 4212 deaths from February 24 to July 24, 2020 (Ministry of Health, 2020).

The COVID-19 affects the world economy negatively, due to a sharp increase in the doubt of economic development, and due to the stop of economic activities as a result of restriction movement and transportation to control the spread of the pandemic. It is well-known that air pollution reduces with decreasing economic activities (Wang and Su, 2020).

The lockdown measures have shut down industries, halted vehicular traffic and have had a huge impact on the daily routine of the people. Due to this, considerable improvement in air quality levels of countries such as Spain (Tobías et al., 2020), India (Gautam, 2020), Brazil (Nakada and Urban, 2020), and China (Sharma et al., 2020) has been reported. The plummet in pollutant concentration is obvious, due to the restriction in anthropogenic activities.

The air is a vital element for the survival of all living beings; hence, it is necessary to keep it clean and safe. The anthropogenic activities are a major cause of ambient air pollution, due to emission of many harmful pollutants in high concentration, which are health damaging (Gautam and Hens, 2020a; Ghorani-Azam et al., 2016). The main causes of air pollution include economic development, urbanization, energy consumption, transportation and motorization, as well as the rapid increase of urban population (Kaplan et al., 2019). The biggest air pollutants encountered in our daily life are particulate matter (PM), sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), ozone (O3), carbon monoxide (CO), and carbon dioxide (CO2) (Chen et al., 2007). NO2 is an important component of urban air pollution and a precursor to ground level ozone, particulate matter, and acid rain (Bechle et al., 2013). The main sources of NO2 in the ambient atmosphere are the burning of fossil fuels such as coal, oil and gas. NO2 is a highly reactive pollutant and emitted, especially from the combustion of fossil fuels. Transportation is considered as the major source of NO2 emissions (Muhammad et al., 2020).

PM is a major pollutant, emitted from vehicles, residential, energy, industrial and dust (Guo et al., 2017; Guo et al., 2019). PM is responsible for respiratory infections, lung disease, and importantly compromised immune system (Kim et al., 2018). PM2.5 specifically, has an impact as it passes through the respiratory system and provides high chances of getting deposited in lungs (Kim et al., 2018; Li et al., 2018). O3 is a common oxidant gas in urban air, and exposure to ozone can induce oxidative stress causing airway inflammation and increased respiratory morbidities (Adhikari and Yin, 2020). Surface O3 concentration depends on the magnitude and ratio of the emissions of precursor gases (e.g. NOx, and VOCs), photochemical reactions, atmospheric conditions (weather), removal processes at the earth's surface and hence on local, regional, seasonal factors. In most regions O3 declines with decreasing NOx emissions; however, in some traffic-intensive urban regions dominated by high-NOx emissions, O3 may initially increase in response to declining NOx emissions, but after transport of the urban plume to rural areas O3 will eventually decrease (Dentener et al., 2020).

The energy sector (crude oil production) represents the backbone of the Iraqi economy and its exports. Iraq relies heavily on the use of fossil fuels for electricity production, which has increased from recent years, due to population growth and growing electricity consumption (Hashim et al., 2020). Electricity production, oil refining, natural gas flaring, transportation and population are among the most important sources of air pollution in Iraq (IEA, 2012). The absence of a reliable national electrical power network has led to the spread of different kinds of generators of various sizes servicing homes, farms, factories, and various governmental and non-governmental institutions. These sources led to the low air quality in Iraq, especially in large cities such as Baghdad and Basra (Ministry of Environment, 2016). A lot of sites in Iraq can be regarded as high density traffic sites especially in the capital Baghdad. An excess of pollution and high levels of emission of various pollutants due various reasons are produced. One of the major reasons is pollution, due to automobile fuel consumption which led to a negative impact on the economy and environment (Jassim et al., 2014).

Air quality changes due to the COVID-19 lockdown quickly became a new topic of recent research studies. Kerimray et al. (Kerimray et al., 2020) analyze the effect of the lockdown from March 19 to April 14, 2020, on the concentrations of air pollutants in Almaty, Kazakhstan. Daily concentrations of PM2.5, NO2, SO2, CO and O3 were compared between the periods before and during the lockdown. During the lockdown, the PM2.5 concentration was reduced by 21%. There were also substantial reductions in CO and NO2 concentrations by 49% and 35%, respectively, but an increase in O3 levels by 15% compared to the prior 17 days before the lockdown. Otmani et al. (2020) evaluated the changes in levels of some air pollutants, PM10, NO2 and SO2 in Salé city, Morocco, during the lockdown measures. The obtained results showed that the difference between the concentrations recorded before and during the lockdown period were respectively 75%, 49% and 96% for PM10, SO2 and NO2.

Satellite instruments afford a global view of the planet's air pollution. The Sentinel-5Precursor/Tropospheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI) sensor is a part of the European Space Agency (ESA) space Program for earth monitoring; the main objectives are to provide operational space-borne observations in support to the operational monitoring of Air Quality (Borsdorff et al., 2018). Using spectral bands from the ultraviolet, visible and near-infrared wavelength range, TROPOMI measures O3, NO2, SO2, bromate (BrO3 −), formaldehyde (HCHO) and water vapor (H2O) tropospheric columns from the ultraviolet, visible and near-infrared wavelength, and CO and methane (CH4) tropospheric columns are measured from the short-wave infrared wavelength range (Veefkind et al., 2017). The S-5P/TROPOMI data used in several air pollution studies during outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic around the world. Gautam, 2020 studied NO2 column observations to compare the air quality data released by international agencies before and after the novel coronavirus pandemic over India, China, Spain, France and Italy. The significant reduction in the percentage of NO2 in India and China by using S-5P/TROPOMI reached 70% and 20–30% NO2 reduction in India and China, respectively. The NO2 reduced 20–30% in European countries (i.e., Spain, Italy, and France).

Finally, in an attempt to point out the main changes in NO2, O3, PM2.5, PM10 concentrations and Air Quality Index (AQI) in Baghdad, their daily averages were calculated for the periods before the lockdown from January 16 to February 29, 2020, and during four periods of partial and total lockdown from (March 1 to July 24, 2020). The objective was to evaluate the relative variation (in %) and the difference in the mean concentration (in μg/m3) between the five periods (before and during the lockdown). Study of NO2 tropospheric column data derived from TROPOMI over Iraq from January to July 2020, and calculates reduction in the percentage of NO2 before and during the lockdown. This study aims to assess the impacts of COVID-19 lockdown conditions on the air quality of Baghdad, which is one of the most polluted large cities in the Middle East.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study area

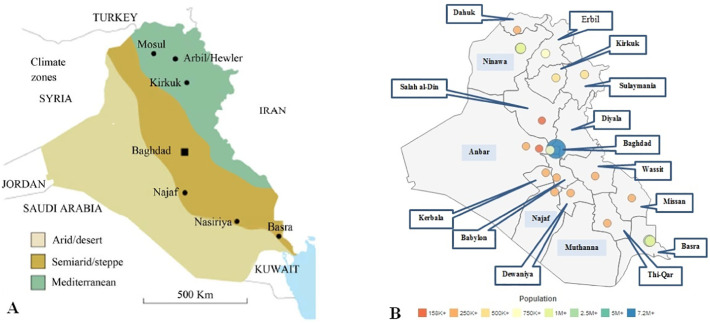

Iraq is located in the eastern part of the Middle East and North African countries (MENA region). It is surrounded by Iran in the east, Turkey to the north, Syria, and Jordan to the west, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait to the south and the Gulf to the southeast (Al-Ansari, 2013). Iraq has a narrow coastal strip on the Arabian Gulf with a length of about 58 km (El Raey, 2010). The climate in Iraq is mainly of the continental, subtropical semi-arid type, with the north and north-eastern mountainous regions having a Mediterranean climate (FAO, 2003). Iraq is shaped like a basin containing the great Mesopotamian plain of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, as shown in Fig. 1A (Al-Ansari, 2013). The current population of Iraq is about 40 million, shown in Fig. 1B based on projections of the latest United Nations data. Iraq is currently growing at a rate of 2.32% per year. Nearly 70% of Iraq's population lives in urban areas, and they have several large cities that reflect that. The largest by far is the nation's capital, Baghdad, with a population of 7.5 million. The cities of Basra and Mosul both have populations exceeding 2 million derived from Iraq population data (https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/iraq-population/). Baghdad city is located in central Iraq. The borders of the municipality of Baghdad encompass fourteen administrative units, eight in Rusafa (east of Tigris River) and six in Karkh (west of Tigris River). The area of the municipality of Baghdad reached 870 km2. Advantages of the characteristics of study area are: essentially great extremism in temperature, little precipitation, low relative humidity and high brightness of the sun (Hashim and Sultan, 2010).

Fig. 1.

(A) Climate zones of Iraq; (B) Iraq population in 2020.

2.2. Data sources

Due to the technical damage of automatic monitoring stations for air pollutants of the Ministry of Environment in Baghdad during the previous period, air pollution data were collected from an online platform (https://air.plumelabs.com/en/) monitoring and analyzing the air quality (World Air Map, 2020). Daily concentrations of four air pollutants were measured, including NO2, O3, PM2.5 and PM10 for Baghdad before and during the lockdown, in addition to the air quality index (AQI) for the same time period. NO2, O3, PM2.5 and PM10 concentration values were not available for the previous years. In this work, used S-5P/TROPOMI global daily gridded data at 0.05° × 0.05° derived from the near-real-time operational product (Van Geffen et al., 2019), obtained via the Copernicus open data access hub derived from European Space Agency (ESA), (https://s5phub.copernicus.eu) for NO2 tropospheric column data. Table 1 shows dates of data acquisition of S-5P/TROPOMI that cover the period from January 02, 2020, before the lockdown in Iraq until July 24, 2020.

Table 1.

Dates of data acquisition of S-5P/TROPOMI that covers the period from January 02, 2020, before the lockdown in Iraq until July 24, 2020 in current study.

| Situation | Dates of data acquisition from TROPOMI |

|---|---|

| Before COVID-19 pandemic (business as usual) | January 02, 2020 |

| Before COVID-19 pandemic (business as usual) | February 04, 2020 |

| During partial lockdown | March 16, 2020 |

| During total lockdown | April 02, 2020 |

| During partial lockdown | April 30, 2020 |

| During partial lockdown | May 19, 2020 |

| During total lockdown | June 05, 2020 |

| During partial lockdown | July 24, 2020 |

2.3. AQI calculation

To understand the overall improvement in air quality, AQI was detailed. AQI uses NO2, O3, PM2.5 and PM10, of which minimum concentrations three pollutants should be available. The concentrations are converted to a number on a scale of 0–500. The sub index AQI (AQIi) for each pollutant (i) is calculated using Eq. (1)

| (1) |

where, Ci is the concentration of pollutant ‘i’; BHI and BLO are breakpoint concentrations greater and smaller to Ci and INHI and INLO are corresponding AQI values. The overall AQI is the maximum AQIi, and the corresponding pollutant is the dominating pollutant. The AQI is divided into six categories: good, satisfactory, moderate, poor, very poor and severe depending on whether the AQI falls between 0–50, 51–100, 101–200, 201–300, 301–400 and 401–500, respectively (Sharma et al., 2020).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Air pollution assessment during COVID-19

Lockdown due to COVID-19 reduced transportation activities, which results in less energy consumption and lower oil demand. These changes in transport activities and oil demand exert a significant impact on the environmental quality.

3.1.1. NO2 concentration

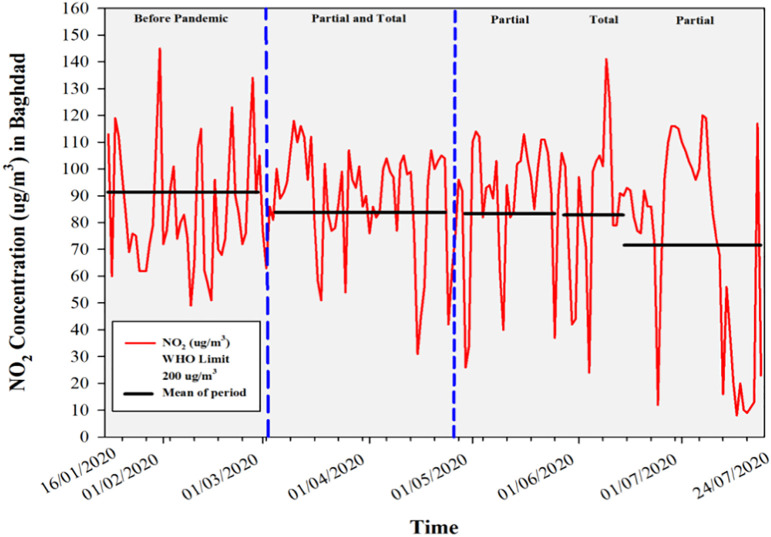

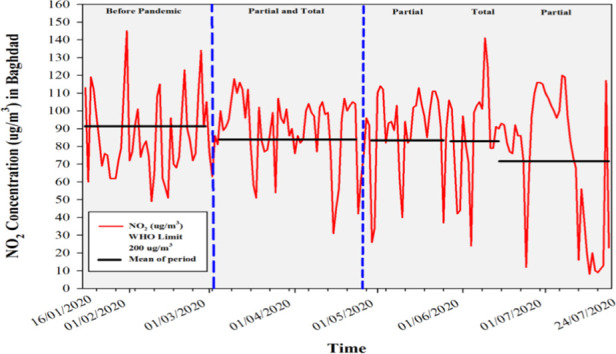

Fig. 2 represents the NO2 concentrations (μg/m3) in Baghdad, before and during the lockdown from January 16 to July 24, 2020. The results showed that average of NO2 concentration before lockdown from January 16 to February 29 was 91 μg/m3. During the 1st partial and total lockdown from March 1 to April 21; daily NO2 concentrations reduced in Baghdad, due to the slowdown in transportation activity and social distancing measures, and average of NO2 of this period was 86 μg/m3. The NO2 average continued to decline during the period of April 22 to May 23, during the 2nd partial lockdown, reached 85 μg/m3. As a result of high number of confirmed cases of Covid-19 in Iraq, the total lockdown was imposed again from May 24 to June 13. The average of NO2 concentration in Baghdad during this period reached 84 μg/m3. The concentration of NO2 continued to fluctuate with a tendency to decrease in Baghdad from June 14 to July 24 during the 3rd partial lockdown. The average of NO2 concentration during this period reached 73 μg/m3, that is confirms decrease NO2 concentration in Baghdad during the lockdown, relative to same levels in January 2020. From Fig. 2, noted the daily concentrations and averages of NO2 did not exceed the WHO limit 200 μg/m3, before and after lockdown.

Fig. 2.

NO2 concentrations (μg/m3) in Baghdad, before and during the lockdown from January 16 to July 24, 2020.

3.1.2. O3 concentration

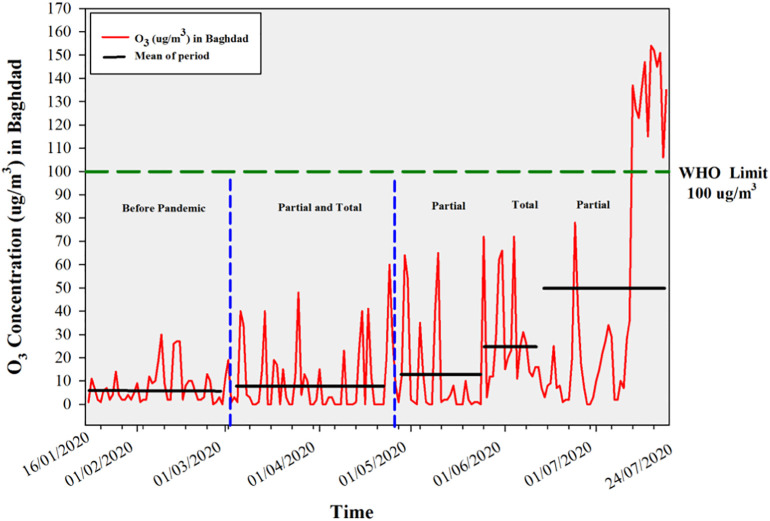

Fig. 3 represents daily O3 concentrations (μg/m3) in Baghdad from January 16 to July 24, 2020. The average of O3 before the pandemic from January 16 to February 29 reached 8 μg/m3. Daily O3 concentrations rose during the 1st partial and total lockdown from March 1 to April 21, the average of O3 recorded 9 μg/m3. After the 1st total lockdown, the average of O3 from April 22 to May 23 increased again to 14 μg/m3. Daily O3 concentrations continued to rise in Baghdad during May and early June, reaching an average from May 24 to June 13, 26 μg/m3. In mid-July, the daily O3 concentration exceeded WHO limit 100 μg/m3 for the first time in 2020, due to high temperatures and low NO2 concentrations. The average of O3 from June 14 to July 24 reached 50 μg/m3. The increase in O3 concentrations in Baghdad was associated with a decrease in NO2 concentrations, due to the inverse relationship between them.

Fig. 3.

O3 concentrations (μg/m3) in Baghdad from January 16 to July 24, 2020.

3.1.3. PM2.5 concentration

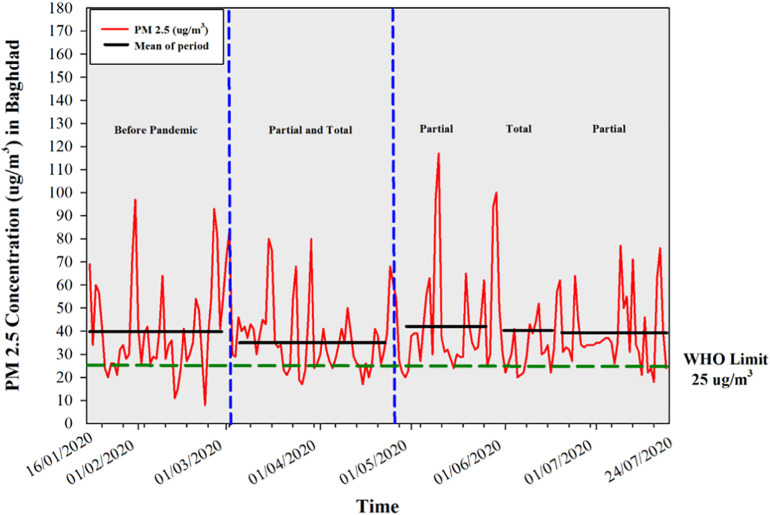

Fig. 4 represents the daily concentrations (μg/m3) of PM2.5 in Baghdad from January 16 to July 24, 2020. The results showed that the average of PM2.5 concentration before the pandemic, from January 16 to February 29, was 40 μg/m3. During the 1st partial and total lockdown from March 1 to April 21, the average of PM2.5 concentration dropped to 37 μg/m3. Daily concentrations of PM2.5 increased at the end of April and beginning of May, reaching a maximum value of 117 μg/m3. The average of PM2.5 from April 22 to May 23, reached 42 μg/m3. During the 2nd total lockdown from May 25 to June 13, the average of PM2.5 decreased slightly to 40 μg/m3. From June 14 to July 24, the period characterized by fluctuating daily PM2.5 concentrations during the 3rd partial lockdown, bringing the average of PM2.5 to 39 μg/m3. Although daily concentrations of PM2.5 in Baghdad recorded few values less than the WHO limit 25 μg/m3, but during the study period most of the PM2.5 concentration exceeded this limit, especially in May and June, due to drought and high temperature.

Fig. 4.

PM2.5 concentrations (μg/m3) in Baghdad from January 16 to July 24, 2020.

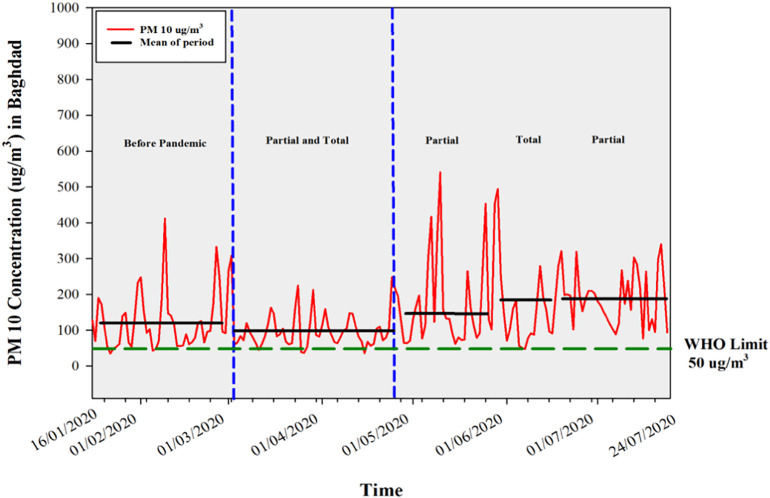

3.1.4. PM10 concentration

Fig. 5 represents the daily concentrations of PM10 (μg/m3) in Baghdad from January 16 to July 24, 2020. The results showed that the average of PM10 concentration before the pandemic, from January 16 to February 29, was 119 μg/m3. During the 1st partial and total lockdown from March 1 to April 21, the average of PM10 concentration dropped to 101 μg/m3. Daily concentrations of PM10 increased at the end of April and beginning of May, reaching a maximum value of 541 μg/m3. The average of PM10 from April 22 to May 23, reached 160 μg/m3. During the 2nd total lockdown from May 25 to June 13, the average of PM10 increased to 185 μg/m3. From June 14 to July 24, the period characterized by fluctuating daily of PM10 concentrations during the 3rd partial lockdown, the average of PM10 increased slightly to 186 μg/m3. The summer in Iraq lead to activity in the movement of wind, which raises dust, which increases the concentration of PM in Baghdad; in addition to the influence of transportation and fuel combustion activities. Almost all daily recorded concentrations of PM10 in Baghdad exceeded the WHO limit 50 μg/m3, during the study period.

Fig. 5.

PM10 concentrations (μg/m3) in Baghdad from January 16 to July 24, 2020.

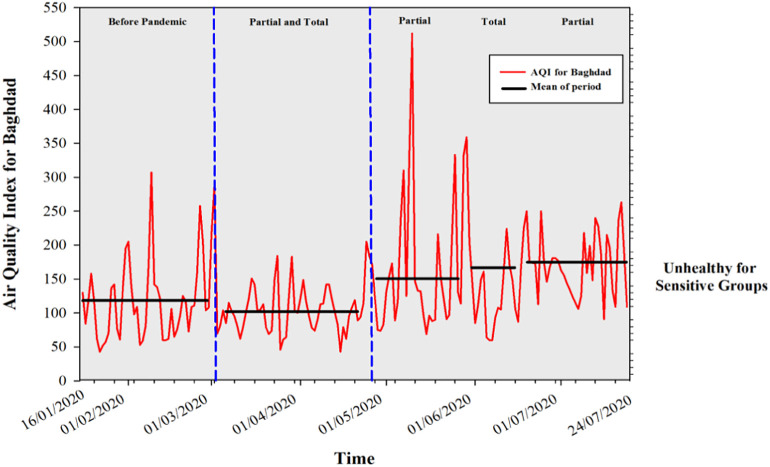

3.2. AQI for Baghdad

For the purpose of studying the air quality of Baghdad before and during the lockdown, according to the recorded values of air pollutants, Fig. 6 represents the AQI for Baghdad from January 16 to July 24, 2020. Before the pandemic, from January 16 to February 29, AQI values ranged between 50 and 300, with an average of 120; meaning that AQI located within the third level (unhealthy for sensitive groups). From March 1 to April 21, AQI values improved in Baghdad, and the average for this period reached 105. The reduction average of AQI before and during this period reached around 13%. AQI of Baghdad declined during the 2nd partial lockdown from April 22 to May 23, with highest daily value reached 512. The average for this period increased to 151. AQI of Baghdad continued to record poor numbers. The average for the total and partial lockdown periods from May 24 to July 24, 2020 recorded 161 and 167, respectively. The above results confirm that the AQI for Baghdad recorded the lowest values during the 1st partial and total lockdown period in March and April 2020. This period represented the lowest daily concentrations of air pollutants recorded in the current study. It also recorded the lowest average of pollutants compared to the pre-pandemic and post-pandemic period, due to citizen's commitment to lockdown measures, slow transportation, closures of universities and schools, and restrictions on the movement of employees. These measures contributed to a large extent to the decrease in the air pollutants emission in Baghdad during the 1st partial and total lockdown.

Fig. 6.

AQI of Baghdad before and during the lockdown from January 16 to July 24, 2020.

3.3. Percentage changes of NO2, O3, PM2.5, PM10 concentrations and AQI

The concentrations of NO2, O3, PM2.5 and PM10 were not available from the used sources for the previous years; therefore, the values were compared between the periods before the lockdown (January 16, 2020) and during the lockdown (March 1 to July 24, 2020). There was a reduction average concentrations of PM10, PM2.5 and NO2 by 15%, 8% and 6%, respectively, compared to the period before the lockdown, as shown in Table 2 . There was a substantial reduction in the average concentrations of NO2 in lockdown periods by 7%, 8% and 20%, respectively, compared to the period before the lockdown. There was a reduction average concentrations PM2.5 by 2.5% during June 14 to July 24, compared to the period before the lockdown. There was an increase in PM10 by 34%, 55% and 56%, respectively, during the periods of lockdown. The natural sources of suspended particles in Iraq are dust and suspended in the air. This phenomenon reaches its top activity in spring and summer, due to the arrival of depressions coming from north of the Arabian Gulf and from central Asia causing northwesterly winds with a varying severity according to the depression's severity (1st National Communication, Ministry of Health and Environment (MoHE), 2016). As for the industrial sources, represented by power plants and transportation, as well as the spread of different kinds of generators of various sizes servicing homes, farms, factories, and various governmental and non-governmental. This leads to increased air pollutants in the atmosphere, and environmental pollution (Hashim et al., 2020). On the other hand, there was an increase in O3 by 13%, 75%, 225% and 525%, between the periods before the lockdown (January 16 to February 29, 2020) and during the lockdown (March 1 to July 24, 2020). That's can be explained by the higher levels of solar activity during the period of the lockdown, especially in June and July. The AQI improved in Baghdad during the 1st lockdown, compared to its pre-lockdown average of −13%. However, this temporary improvement diminished in the subsequent periods, reaching 39% during the June and July. The poor air quality of Baghdad is due to the presence of most industrial and commercial activities there, in addition to high population density and traffic pollution. Also, the climate of Iraq in general is dry and hot in summer, which led to increase the concentration of pollutants and deteriorate the air quality (Ministry of Environment, 2016).

Table 2.

Percentage changes of average concentrations of (NO2, O3, PM2.5, PM10 Concentrations and AQI) between January 16, 2020 (before the lockdown) and during the lockdown periods.

| Time period | Average of NO2 | Average of O3 | Average of PM2.5 | Average of PM10 | Average of AQI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January 16–February 29 (before the lockdown) | 91 | 8 | 40 | 119 | 120 |

| March 1–April 21 (during the 1st partial and total lockdown) | 86 | 9 | 37 | 101 | 105 |

| Percent reduction | −6% | 13% | −8% | −15% | −13% |

| April 22–May 23 (during the 2nd partial lockdown) | 85 | 14 | 42 | 160 | 151 |

| Percent reduction | −7% | 75% | 5% | 34% | 26% |

| May 25–June 13 (during the 2nd total lockdown) | 84 | 26 | 40 | 185 | 161 |

| Percent reduction | −8% | 225% | 0% | 55% | 34% |

| June 14–July 24 (during the 3rd partial lockdown) | 73 | 50 | 39 | 186 | 167 |

| Percent reduction | −20% | 525% | −2.5% | 56% | 39% |

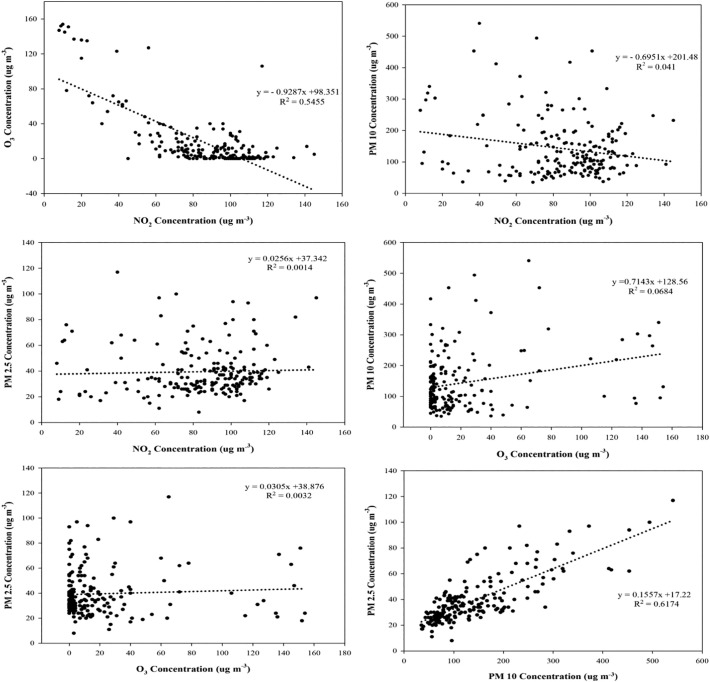

Fig. 7 presents the correlation coefficients between air pollutants (NO2, O3, PM2.5 and PM10) in air of Baghdad before and after the lockdown. Air pollutants had significant correlations with each other. The PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations correlated well (R2 = 0.6174), which could indicate that PM2.5 and PM10 originated from common sources. On the other hand, NO2 had negatively correlated with O3 and PM10. The concentration of surface O3 decreases substantially with increased concentration of NO2. When the nitric oxide (NO) emissions are sufficiently large, NO released in the atmosphere converts a large fraction of O3 into NO2 (Monks et al., 2015).

Fig. 7.

The correlation coefficients between air pollutants (NO2, O3, PM2.5 and PM10) in air of Baghdad before and after the lockdown.

3.4. NO2 tropospheric column from S-5P/TROPOMI

Fig. 8 represents NO2 emission in Iraq before, and during the COVID-19, based on dates of data acquisition derived from S-5P/TROPOMI, as shown in Table 1. According to these data, the NO2 emissions reduced up to 35 to 40% across Iraq due to lockdown, between January and July 2020, especially across the major cities such as Baghdad, Basra, Najaf, and Erbil. Fig. 8 showed that Baghdad recorded the highest NO2 emission before the lockdown, compared to other cities, due to high population density, traffic pollution and industrial activities. The region located southern Baghdad, such as Babylon, Najaf and Karbala, contained high NO2 emissions, due to industrial activities and power plants. Basra in southern Iraq has hotspots of NO2, because it is the largest city in the south of Iraq contains oil fields and associated gas burning activities. The effect of the lockdown is apparent on the reduction of NO2 emission in Baghdad, Basra and Erbil. Transportation restriction, industry emission slowdown, led to a clear decrease in NO2 emission, compared to previous periods, before and during the COVID-19 lockdown. Due to the high incidence of confirmed cases of COVID-19, the Iraqi government announced the 2nd total lockdown again on May 24, 2020, to control the spread of the pandemic. As a result, NO2 emission decline almost to the lowest levels on June 5, 2020 in all parts of Iraq. On June 14, up to July 24, 2020 Iraq has returned and announced the partial lockdown for the third time. NO2 emission decline slightly, especially in Baghdad, Basra and Erbil, compared to the levels in the beginning of April. The results showed that the NO2 tropospheric column over Iraq revealed a major hotspot of high concentration, especially in the Baghdad and Basra before the lockdown, and these hotspots receded significantly during the lockdown on April, June and July 2020.

Fig. 8.

NO2 emissions in Iraq before, and during the COVID-19 lockdown, based on data acquisition derived from S-5P/TROPOMI.

4. Conclusions

In this study, the influences of emission reductions due to reduced anthropogenic activities, mainly on transportation and industry during the COVID-19 lockdown in Iraq on air pollution were investigated. There was a substantial reduction in the NO2 concentration by 6, 7, 8 and 20% in Baghdad during four periods of partial and total lockdown, compared to the period before the lockdown. There was 8 and 15% reduction in PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations, respectively, in Baghdad, during the 1st partial and total lockdown. Even under the low-traffic pollution in Baghdad, the PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations before and during the lockdown period exceeded the WHO daily limit values, providing evidence of the high contribution from non-traffic related sources, such as natural sources and local dust. On the other hand, there was an increase in O3 by 13%, 75%, 225% and 525%, between the periods before the lockdown (January 16 to February 29, 2020) and during the lockdown (March 1 to July 24, 2020), which could be due to the decrease in NO2 and increase PM10 concentrations. The AQI improved in Baghdad during the 1st lockdown, average of 13%, compared to its pre-lockdown. However, this temporary improvement diminished in the subsequent periods, during the June and July. Data of NO2 tropospheric column derived from Sentinel-5P/TROPOMI shown clearly reduction up to 35 to 40% across Iraq, during the lockdown; due to transportation restriction and industry emission slowdown. Transportation and industrial activities have significantly been affected due to COVID-19 lockdowns, as there are less energy consumption and less oil demand. The outcomes of the lockdown can be easily identified as an improvement of the environmental and air quality; despite the economic and social consequences associated with the lockdown.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This research was carried out according to the resources available in the Ministry of Science and Technology in Iraq, in cooperation with Dr. Nadir Al-Ansari from the Lulea University.

Editor: Scott Sheridan

References

- Adhikari A., Yin J. Short-term effects of ambient ozone, PM2.5, and meteorological factors on COVID-19 confirmed cases and deaths in Queens, New York. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health, MDPI. 2020;17:4047. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17114047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ansari N. vol. 5. 2013. Management of Water Resources in Iraq: Perspectives and Prognoses Engineering, Scientific Research; pp. 667–684. [Google Scholar]

- Bechle M.J., Millet D.B., Marshall J.D. Remote sensing of exposure to NO2: satellite versus ground-based measurement in a large urban area. Atmos. Environ. 2013;69:345–353. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bherwani H., Gupta A., Anjum S., Anshul A., Kumar R. Exploring dependence of COVID-19 on environmental factors and spread prediction in India. Res. Square. 2020 doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-25644/v1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borsdorff T., de Brugh J., Hu H. Mapping carbon monoxide pollution from space down to city scales with daily global coverage. Atmos. Meas. Technol. 2018;11:5507–5518. doi: 10.5194/amt-11-5507-2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cascella M., Rajnik M., Cuomo A., Dulebohn S., Di Napoli R. Statpearls [Internet] StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Features, evaluation and treatment coronavirus (COVID-19) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T.M., Kuschner W.G., Gokhale J., Shofer S. Outdoor air pollution: nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, and carbon monoxide health effects. Am J Med Sci. 2007;333(4):249–256. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31803b900f. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantas G., Siciliano B., França B., Silva da, Cleyton M., Arbilla G. The impact of COVID-19 partial lockdown on the air quality of the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Sci. Total Environ. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139085. Elsevier. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dentener F., Emberson L., Galmarini S., Capelli G., Irimescu A., Mihailescu D., Van Dingenen R., van den Berg M. Lower air pollution during COVID-19 lock-down: improving models and methods estimating ozone impacts on crops. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A. 2020 doi: 10.1098/rsta.2020.0188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Raey M. University of Alexandria, Arab Academy of Science Technology and Maritime; 2010. Impact of Sea-level Rise on the Arab Region.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266454174_Impact_of_Sea_Level_Rise_on_the_Arab_Region [Google Scholar]

- ESA (European Space Agency) 2020. https://s5phub.copernicus.eu Available online. Accessed on 8.10.20.

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization) The Transition from Relief, Rehabilitation, and Reconstruction to Development. 2003. Towards sustainable agricultural development in Iraq; p. 222. [Google Scholar]

- Gautam S. COVID-19: air pollution remains low as people stay at home. Air Qual. Atmos. Health. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11869-020-00842-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam S., Hens L. SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in India: what might we expect? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020;22:3867–3869. doi: 10.1007/s10668-020-00739-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam S., Hens L. COVID-19: impact by and on the environment, health and economy. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10668-020-00818-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam S., Trivedi U.K. Global implication of bioaerosol in pandemic. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020;22:3861–3865. doi: 10.1007/s10668-020-00704-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghorani-Azam A., Riahi-Zanjani B., Balali-Mood M. Effects of air pollution on human health and practical measures for prevention in Iran. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2016;21:65. doi: 10.4103/1735-1995.189646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H., Kota S.H., Sahu S.K., Hu J., Ying Q., Gao A. Source apportionment of PM2.5 in North India using source-oriented air quality models. Environ. Pollut. 2017;231:426–436. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H., Kota S.H., Sahu S.K., Zhang H. Contributions of local and regional sources to PM2.5 and its health effects in North India. Atmos. Environ. 2019;214 [Google Scholar]

- Hashim B., Sultan M. Using remote sensing data and GIS to evaluate air pollution and their relationship with land cover and land use in Baghdad City. Iran. J. Earth Sci. 2010;1(2):120–124. [Google Scholar]

- Hashim B.M., Sultan M.A., Al Maliki A.A., Al-Ansari N. Estimation of greenhouse gases emitted from energy industry (oil refining and electricity generation) in Iraq using IPCC methodology. Atmosphere. 2020;11:662. doi: 10.3390/atmos11060662. mdpi. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- IEA (International Energy Agency), 2012. Iraq Energy Outlook: World Energy Outlook Special Report, p. 142. Available online: http://www.worldenergyoutlook.org (Accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Iraq Population, 2020. World population review. Available online:https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/iraq-population/.

- Jassim H., Ibraheem F., Zangana B. Energy and Sustainability V, WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment. 2014. Environmental issues caused by the increasing number of vehicles in Iraq; p. 186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jebril N. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the environment—a case study of Iraq. SSRN Electron. J. 2020 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3597426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang F., Deng L., Zhang L., Cai Y., Cheung C.W., Xia Z. Review of the clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05762-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan G., Avdan Z.Y., Avdan U. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, Proceedings, MDPI; 2019. Spaceborne Nitrogen Dioxide Observations from the Sentinel-5P TROPOMI over Turkey. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kerimray A., Baimatova N., Ibragimova O., Bukenov B., Kenessov B., Plotitsyn P., Karaca F. Assessing air quality changes in large cities during COVID-19 lockdowns: the impacts of traffic-free urban conditions in Almaty, Kazakhstan. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;730 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D., Chen Z., Zhou L.F., Huang S.X. Air pollutants and early origins of respiratory diseases. Chron. Dise. Transl. Med. 2018;4(2):75–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cdtm.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Hu R., Chen Z., Li Q., Huang S., Zhu Z. Fine particulate matter (PM2.5): the culprit for chronic lung diseases in China. Chron. Dis. Transl. Med. 2018;4(3) doi: 10.1016/j.cdtm.2018.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R., Zhao X., Li J., Niu P., Yang B., Wu H., Wang W., Song H., Huang B., Zhu N. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Environment (MoEN) 2016. Environment Situation in Iraq: Baghdad, Iraq; p. 282. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health Daily situations of COVID-19 in Iraq. 2020. www.moh.gov.iq

- Ministry of Health and Environment (MoHE) 2016. Initial National Communication to the UNFCCC: Baghdad, Iraq; p. 240. [Google Scholar]

- Monks P., Archibald A., Colette A., Cooper O., Coyle M., Derwent R. Tropospheric ozone and its precursors from the urban to the global scale from air quality to short-lived climate forcer. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015;15(15):8889–8973. doi: 10.5194/acp-15-8889-2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad S., Long X., Salman M. Covid-19 pandemic and environmental pollution: a blessing in disguise? Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakada L., Urban R.C. COVID-19 pandemic: impacts on the air quality during the partial lockdown in São Paulo state, Brazil. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;730:5. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139087. 139087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otmani A., Benchrif A., Tahri M., Bounakhla M., Chakir E.L., El Bouch M., Krombi M. Impact of Covid-19 lockdown on PM10, SO2 and NO2 concentrations in Salé City (Morocco) Sci. Total Environ. 2020;735 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Morales A.J., Bonilla-Aldana D.K., Tiwari R., Sah R., Rabaan A.A., Dhama K. COVID-19, an emerging coronavirus infection: current scenario and recent developments — an overview. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2020;9 [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S., Zhang M., Gao J., Zhang H., Kota S. Effect of restricted emissions during COVID-19 on air quality in India. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobías A., Carnerero C., Reche C., Massagué J., Via M., Minguillón M.C., Alastuey A., Querol X. Changes in air quality during the lockdown in Barcelona (Spain) one month into the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;726 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosepu R., Gunawan J., Effendy S.D., Ahmad A.I., Lestari H., Bahar H., Asfian P. Correlation between weather and Covid-19 pandemic in Jakarta, Indonesia. Sci. Total Environ. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Geffen, J., Boersma, K.F., Eskes, H., Sneep, M., ter Linden, M., Zara, M. &Veefkind, J.P., 2019. S5P/TROPOMI NO2 slant column retrieval: method, stability, uncertainties, and comparisons against OMI. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques Discussions. doi: 10.5194/amt2019-471, in review. [DOI]

- Veefkind J.P., Kleipool Q., Ludewig A., Stein-Zweers D., Aben I., De Vries J., Loyola D.G., Nett H., Van Roozendael A.M. 2017. Early Results from TROPOMI on the Copernicus Sentinel 5 Precursor. AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Su M. Drivers of decoupling economic growth from carbon emission—an empirical analysis of 192 countries using decoupling model and decomposition method. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2020;106356:81–92. [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Horby P.W., Hayden F.G., Gao G.F. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):470–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (World Health Organization), 2020a. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report-36, February 25, 2020. World Health Organization Geneva. Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default- source/coronaviruse/situationreports/20200225-sitrep-36-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=2791b4e0_2.

- WHO (World Health Organization) Coronavirus disease (covid-19) dashboard, global situation. 2020. http://who.covid19.int/

- World Air Map 2020. https://air.plumelabs.com/en/ Available online. (Accessed on 8.5.20)