Abstract

In the wake of the Covid-19 phenomenon, a new world economic order is emerging. This upheaval is unprecedented in the collective memory with as a result, profound social changes.

The first sign appears in human behaviour, lucidity is increasingly an elite sport that few people practice. This leaves more and more room for conformism, the illusion of free will, and the irrational and impulsive crowd reasoning that was exploited during this pandemic by politicians and pharmaceutical industries.

Strong and strange correlations result, on which we shed light in this work and that links the prescription of hydroxychloroquine, the behaviour of populations, their political prejudices, and their fatality rates.

The urgency imposes rigid communication between rulers and governed. The pandemic brings to light the contradictions of this liaison.

Keywords: Case fatality rate, conflicts of interest, COVID-19, Donald Trump, hydroxychloroquine, politics, social changes, Spearman correlation

Highlights

-

•

In the USA, the higher Trump’s net approval, the lower the Covid19 Fatality Rate.

-

•

The impact of a large-scale use of Hydroxychloroquine is observable after a few days in the CFR’s evolution.

-

•

Data used in this study is public.

Résumé

Dans le sillage du phénomène Covid-19, il y a émergence d’un nouvel ordre économique mondial. Ce bouleversement est inédit dans la mémoire collective, avec en conséquence des mutations sociales profondes.

Le premier signe apparait dans le comportement humain, la lucidité est de plus en plus un sport d’élite que peu de gens pratiquent. Ce qui laisse de plus en plus place au conformisme, à l’illusion du libre arbitre et au raisonnement de foule, irrationnel et impulsif et qui a été exploité durant cette pandémie par les politiques et les industries pharmaceutiques.

De fortes et étranges corrélations en résultent, sur lesquels nous mettons la lumière dans ce travail et qui lient la prescription de l’hydroxychloroquine, les comportements des populations, leurs préjugés politiques et leurs taux de létalité.

L’urgence impose communication rigide entre gouvernants et gouvernés. La pandémie met au grand jour les contradictions de cette liaison.

Introduction

Several studies have demonstrated the influences to which health professionals are exposed on the part of pharmaceutical cartels [1], the judgments of doctors and citizens are also prey to mainstream thinking and/or their own political prejudices and beliefs. For example, it has been shown that Democratic and Republican doctors in the United States provide different care on politicized health problems [2]. It has also been shown that citizens’ behaviours towards the current health crisis are influenced by their own political orientations [3].

In times of crisis, this herd behaviour, divergences, and lack of lucidity lead to confusion. This can only be fully controlled by a firm and rigid communication from competent authorities.

In the United States, Trump's favorable opinion of HCQ [4] and the politicization of the pandemic have led to a strange and irrational connection in American opinion: the acceptance of HCQ-based treatment is strongly linked to Trump's approval. This common belief manifests itself in individuals consciously, unconsciously, or spontaneously.

In order to quantify the consequences, knowing that the acceptance of HCQ in the USA is indicated to us by the degree of approval of D. Trump, we matched the latter with the fatality rate in the USA. Surprising discovery: there is a strong correlation between the degree of approval of D. Trump and the fatality rate. Specifically: in the U.S., the more you approve of Trump, the less likely you are to die of Covid19.

In order to rule out some biases and in order to check whether this correlation is indeed due to the prescription of the HCQ. Knowing it’s effectiveness [5,6], we wanted to see its impact, as a first-line treatment, before the epidemic peak, on the whole of a given population, against Covid19.

To do this, we studied the countries where the free will of the doctor and patient was restricted, where HCQ was imposed (or prohibited), simultaneously for the entire population. The countries corresponding to the criteria are Algeria, Brazil, Egypt, France, Iran, and Morocco. These are countries where strong directives have been issued by the supervisory authorities, regarding HCQ's prescription, at a known date.

Result: We found a very strong correlation between the issue dates of these directives and the dates of change in the evolution trend of the fatality rate. More specifically, a sudden trend change can be observed on the tracings of the fatality rate evolution, a few days after the issuance of said directives, for all said countries.

In order to provide some counter-examples and compare the different trends of the fatality rates, 4 other countries were included in this study, where the population had relative ease of choice of medical treatment. These are Germany, Belgium, Spain, and the United Kingdom. This will identify the similarities/dissimilarities between these 10 countries.

Materials and methods

To calculate the CFR as of June 25, 2020 for all the US states, data were collected from Worldometer, a website which tracks global coronavirus data [7]. Data on Trump's net approval were collected from the Morning Consult website [8], which provides the measurements used for Trump's net approval variable for February 2020. We used the Spearman correlation to demonstrate the correlation between the CFR of the 50 states and Trump's net approval in each of these states.

Data used to calculate the daily CFR for the ten countries studied were collected from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control [9]. The daily CFR was calculated and plotted in each country from the day the number of deaths reached 30 or more in each country until 25 June 2020.

Calculation of the CFR was performed as follows:

| (1) |

We divided the abovementioned ten countries into two groups. Group A comprised Algeria, Brazil, Egypt, Iran and Morocco. This group of countries issued government decisions and guidelines favouring the use of HCQ, with a strong impact on that use. Group B comprised Germany, Belgium, France, Spain and England. This group did not issue government decisions on HCQ; they did not authorize its use without giving guidelines; and/or they restricted its use. We emphasized government decisions made before each country's pandemic peak.

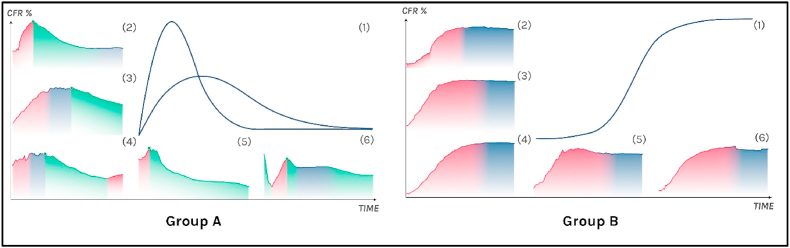

We then noted significant differences between groups A and B in terms of the patterns of CFR development. In particular, when we graphed the group A data, they were distinguished by a form similar to a Rayleigh distribution, while group B data graphs had a sigmoid shape (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Visualization of differences in evolution of case fatality rate (CFR). Group A: (1) Rayleigh distribution, (2) Algeria, (3) Brazil, (4) Egypt, (5) Morocco, (6) Iran. Group B: (1) Sigmoid form, (2) France, (3) Belgium, (4) Germany, (5) England, (6) Spain.

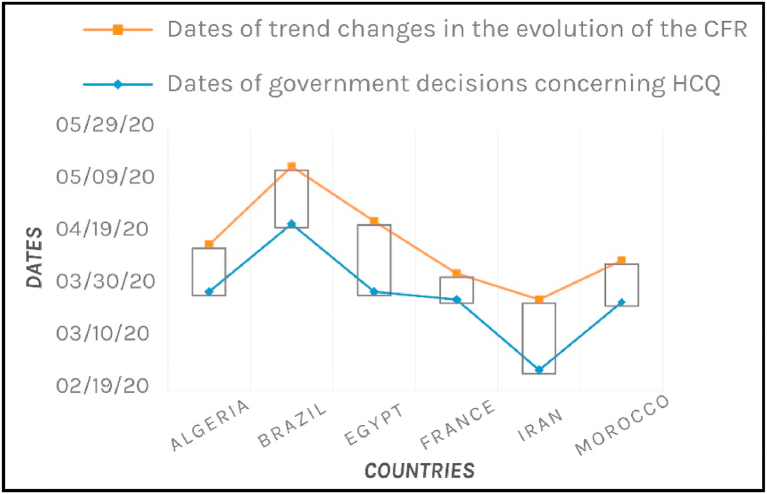

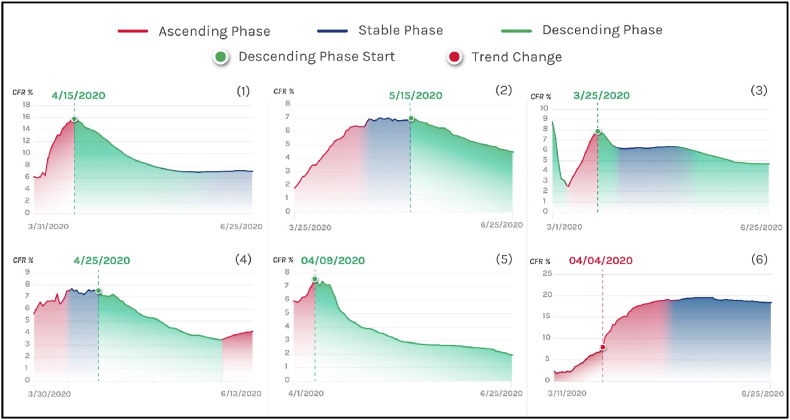

We therefore focused on the dates of government decisions (in favour or not in favour of HCQ treatment) as well as the dates of trend changes in the CFR evolutions. We identified six countries that imposed strict directives concerning the use of HCQ before the peak of the pandemic: Algeria, Brazil, Egypt, France, Iran, and Morocco (Fig. 2). We then studied the Spearman correlation between the ranks of the dates recorded (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Curves of evolution of case fatality rates (CFR) and dates of trend changes for (1) Algeria, (2) Brazil, (3) Iran, (4) Egypt, (5) Morocco and (6) France.

Table 1.

Dates of government decisions addressing HCQ therapy for COVID-19 for each country

| Country | Decision | Date (2020) [study] | Date of trend change (2020) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Algeria | + | 28 March [10] | 15 April |

| Brazil | + | 23 April [11] | 15 May |

| Egypt | + | 26 March [12] | 25 April |

| France | − | 25 March [13] | 4 April |

| Iran | + | 27 February [14] | 25 March |

| Morocco | + | 24 March [15] | 9 April |

+ indicates in favour of HCQ therapy; −, against. Dates of trend indicate changes in evolution of case fatality rate (CFR) for each country. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine.

Results

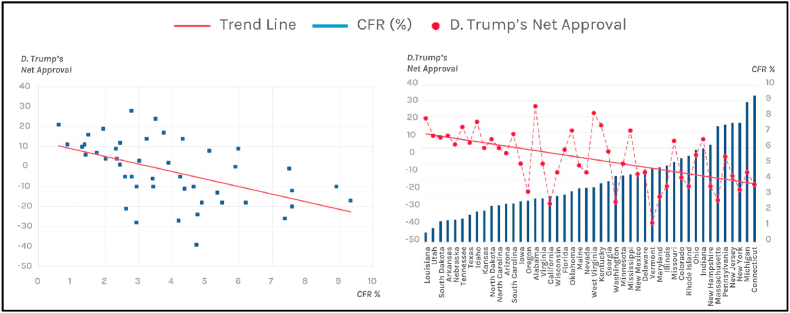

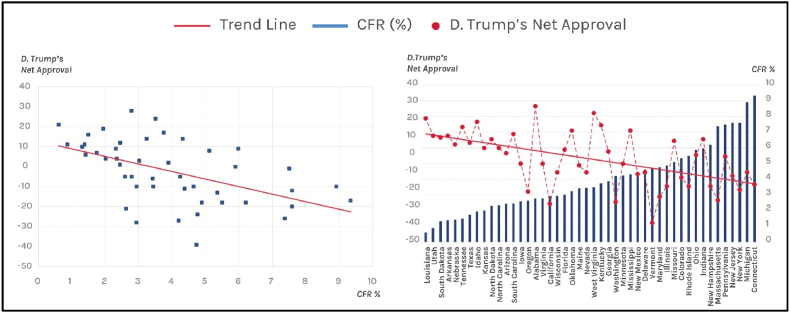

We found a negative and significant correlation at the 0.01 (bilateral) level between Trump's net approval and the [fx]CFR (r = −0.52; P = 0,000114)—in particular, the higher Trump's net approval, the lower the CFR (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Visualization of correlation between Donald Trump's net approval and case fatality rate (CFR). (Left) Net approval as function of CFR. (Right) Net approval and CFR as function of the 50 states of the United States.

We also found a significant correlation (Fig. 4) at the 0.05 (bilateral) level between the ranks of the decisions' dates related to HCQ and the ranks of the dates of the CFR trend changes (ρ = 0.886; p 0.019).

Fig. 4.

Visualization of correlation between hydroxychloroquine (HCQ)-related announcement dates and trend change dates in evolution of case fatality rate (CFR) of each of country.

Discussion

In this research, we sought to highlight several types of correlations. They result from the emergence of several societal behaviour changes, which are particularly noticeable in the United States. We found that Trump's net approval rating has become an indicator of the level of acceptance of HCQ treatment. This political–health interaction explains the correlation observed: The higher the Trump's net approval, the lower the CFR.

Of the ten countries surveyed, more than half (n = 6) made clear-cut decisions regarding the use of HCQ. Algeria, Brazil, Egypt, Iran and Morocco have adopted guidelines in favour of the use of HCQ. This explains, in the pandemic's descending phase, the common trends in the CFRs for these countries. France has restricted the use of HCQ. Ten days after this measure was introduced, the CFR's trend changed to an upward trend.

There is a strong correlation between the ranks of the dates of these decisions and the delay of trend changes of the CFR evolutions for these 6 countries. The other four countries did not issue any definitive decisions. This explains why the forms of CFR evolution are similar in these countries, without sudden variation.

We therefore infer that the the use of HCQ on the whole population of a country affects directly the evolution of the CFR of that country. In particular, the number of deaths depends heavily on the nature of the care, which thus influences the CFR. The CFR also depends on the number of tests performed and the population's demographics [16,17].

Our study indicates that the combination of politics and information on public opinion, the judgement of doctors and individual behaviour are all interrelated. Indeed, earlier studies have referred to the dual psychological and societal risks in times of crisis [[18], [19], [20]].

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Introduction

Plusieurs études ont démontré les influences auxquelles sont exposés les professionnels de santé de la part des cartels pharmaceutiques [1], les jugements des médecins et des citoyens sont également proie à la pensée dominante et/ou à leurs propres préjugés et convictions politiques. Il a par exemple été démontré que les médecins démocrates et républicains aux USA dispensent des soins différents sur les problèmes de santé politisés [2]. Il a également été démontré que les comportements des citoyens vis-à-vis de la crise sanitaire actuelle sont influençables par leurs propres orientations politiques [3].

En temps de crise, ces comportements grégaires, ces divergences et ce manque de lucidité conduisent à la confusion. Celle-ci ne peut être complétement maitrisée que par une communication ferme et rigide de la part des autorités compétentes.

Aux USA, l’avis favorable de D. Trump à propos de l’HCQ [4] et la politisation de la pandémie ont conduit à une liaison étrange et irrationnelle dans l’opinion américain: l’acceptation d’un traitement à base d’HCQ est fortement liée l’approbation de D. Trump. Cette croyance commune se manifeste chez les individus de façon consciente, inconsciente ou spontanée.

Afin d’en quantifier les conséquences, sachant que l’acceptation de l’HCQ aux USA nous est indiquée par le degré d’approbation de D. Trump, nous avons matché ce dernier avec le taux de létalité aux USA. Surprenante découverte, il existe une forte corrélation entre le degré d’approbation de D. Trump et le taux de létalité. Plus précisément: aux USA, plus on approuve D. Trump, moins on a de chances de mourir du Covid19.

Afin d’écarter quelque biais et dans le but de vérifier si cette corrélation est bien due à la prescription de l’HCQ. Sachant son efficacité [5,6], nous avons voulu voir son impact, en tant que traitement de première intention, sur l’ensemble d’une population donnée, contre la Covid19.

Pour ce faire, nous avons étudié les pays ou le libre arbitre du médecin et du patient a été restreint, ou l’HCQ été imposée (ou interdite), simultanément pour l’ensemble d’une population. Les pays correspondants aux critères sont: L’Algérie, le Brésil, l’Egypte, la France, l’Iran et le Maroc. Ce sont des pays ou des directives tranchées ont été émises par les autorités de tutelle, concernant la prescription de l’HCQ, à une date connue.

Résultat: Nous avons découvert une très forte corrélation entre les dates d’émission desdites directives et les dates de changement de tendance de l’évolution du taux de létalité. Plus précisément, un changement de tendance brusque est observable sur les tracés des évolutions du taux de létalité, quelques jours après l’émission desdites directives, pour la totalité desdits pays.

Dans le but d’apporter quelques contre-exemples et de comparer les différentes évolutions des taux de létalité, 4 autres pays ont été inclus dans cet article, ou la population avait une relative aisance de choix du traitement médical. Il s’agit de l’Allemagne, la Belgique, l’Espagne et le Royaume Uni. Ceci permettra de relever les similitudes/dissimilitudes entre ces 10 pays.

Matériel et méthodes

Afin de calculer le taux de létalité au 25 juin 2020 des 50 états des états unis d’Amérique, les données ont été collectés du site web www.worldometers.info [7].

Les données sur le degré d’approbation de D.Trump ont été collectées sur le site web de l’entreprise américaine Morning Consult www.morningconsult.com [8], les mesures utilisées pour la variable d’approbation de D.Trump sont les mesures relatifs à février 2020.

Nous avons utilisé la corrélation de Spearman pour démontrer la corrélation entre le taux de létalité des 50 états des USA et le degré d’approbation de D.Trump dans chacun de ces états.

Les données utilisées pour calculer le CFR journalier des 10 pays qui font l’objet de cette étude ont été collectés du site web www.ecdc.europa.eu [9].

Le taux de létalité journalier a été calculé et tracé dans chaque pays à partir du jours ou le nombre de décès a atteint ou a dépassé 30 décès dans chaque pays, jusqu’au 25 juin 2020.

Calcul du taux de létalité :

Nous avons divisé les 10 pays susmentionnés en deux groupes :

Groupe A : Algérie, Brésil, Egypt, Iran, Maroc. C’est le groupe de pays ayant émis des décisions gouvernementales et des lignes directives favorables a fort impact de l’utilisation de l’HCQ sur le territoire.

Groupe B : Allemagne, Bélgique, France, Espagne, Angleterre. C’est le groupe de pays n’ayant pas émis des décisions gouvernementales sur l’HCQ ou l’ayant autorisé sans donner de lignes directives ou ont restreint son utilisation.

Nous nous sommes intéressés aux décisions gouvernementales qui ont été émises avant le pic épidémique de chaque pays.

Nous avons ensuite relevé des différences notables entre les pays du groupe A et les pays du groupe B au niveau des tracés des évolutions du CFR, notamment, les graphes du groupe A se distinguent par une forme analogue à celle de Rayleigh, tandis que les graphes du groupe B ont une forme sigmoïde (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Visualisation des différences des évolutions du CFR. Groupe A: (1) Forme de Rayleigh, (2) Algérie, (3) Brésil, (4) Egypte, (5) Maroc, (6) Iran. Groupe B: (1) Forme Sigmoïde, (2) France, (3) Bélgique, (4) Allemagne, (5) Angleterre, (6) Espagne.

On s’est donc focalisés sur les dates des décisions, favorables ou pas au traitement, ainsi que sur les dates des changements de tendance dans les évolutions du CFR, 6 pays ont été identifiés, ce sont des pays qui ont imposé des directives concernant la prescription de l'HCQ, avant le pic épidémic., L’Algérie, Le Brésil, l’Egypte, la France, l’Iran et le Maroc, (Fig. 2). Nous avons étudié ensuite la corrélation de Spearman entre les rangs des dates relevés (Tableau 1).

Tableau 1.

Dates des décisions gouvernementales sur l’HCQ de chaque pays, leur nature (Favorable (+), Défavorable (-)). Et les dates de changement de tendance de l’évolution du CFR respectivement de chacun des pays.

Fig. 2.

Courbes des évolutions des taux de létalité ainsi que les dates de changement de tendance pour les pays : (1) Algérie, (2) Brésil, (3) Iran, (4) Egypte, (5) Maroc, (6) France.

Résultats

Nous avons décuvert une corrélation négative et significative au niveau 0.01 (bilatéral) entre le degré d’approbation de D.Trump et le taux de létalité, (r = -0.52; P = 0,000114), notamment, plus le degré d’approbation de D.Trump est important plus le taux de létalité est faible (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Visualisation de la corrélation entre le degré d’approbation de D.Trump et le CFR. A gauche : DA en fonction du CFR. A droite : DA et CFR en fonction des 50 états des USA.

Nous avons également démontré une corrélation (Fig. 4) significative au niveau 0.05 (bilatéral) entre les rangs des dates des décisions concernant l’HCQ avec les rangs des dates de changements de tendance des évolutions du CFR .

Fig. 4.

Visualisation de la corrélation entre les dates d’annonces qui concernent l’HCQ et les dates de changement de tendance dans l’évolution du CFR de chacun des pays mentionnés.

Discussion

Dans ce travail nous avons cherché à mettre en évidence plusieurs types de corrélations. Elles résultent d’un certain nombre d’émergences sociales. Ces comportements nouveaux sont particulièrement marqués aux USA. Ainsi le degré d’approbation du Président D. Trump est devenu un indicateur sur le niveau d’acceptation du traitement HCQ. Cette interaction politico-sanitaire explique la corrélation constatée : Plus le degré d’approbation de D.Trump est important, plus le taux de létalité est faible.

Parmi les dix pays étudiés, plus de la moitié (6) ont pris des décisions tranchées concernant l’utilisation de l’HCQ :

- L’Algérie, le Brésil, l’Egypte, l’Iran et le Maroc ont adoptés des directives favorables à l’utilisation de l’HCQ. Ceci explique, en phase descendante, les évolutions communes des taux de létalité pour ces pays.

- La France a restreint l’utilisation de l’HCQ. Dix jours après instauration de cette mesure, le CFR a changé de tendance vers la hausse.

Il est clair qu’il y a une forte corrélation entre les rangs des dates de ces décisions et les délais de changement de tendance dans les évolutions du CFR pour ces 6 pays.

Les quatre autres pays n’ont pas émis de décisions tranchées. Ceci explique que les formes des évolutions du CFR sont semblables dans ces pays et sans variation brusque.

On peut en déduire que L'utilisation de l'HCQ par l'ensemble d'une population impact directement l’évolution du CFR de ce pays. Notamment, le nombre de décès dépend fortement de la nature des soins. Ces derniers influencent le taux de létalité. Le CFR dépend également du nombre de tests réalisés et de la démographique de la population [16],[17].

A travers notre étude nous souhaitons mettre en lumière l’impact du couple politique/information sur l’opinion publique, sur l’avis des médecins et sur le comportement individuel. Des auteurs précurseurs ont évoqué le couple = risques psychologie/société en périodes de crise [[18], [19], [20]].

Références

- 1.Roussel Y., Raoult D. Influence of conflicts of interest on public positions in the COVID-19 era, the case of Gilead Sciences. New Microbes New Infect. 2020:100710. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2020.100710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hersh E.D., Goldenberg M.N. Democratic and Republican physicians provide different care on politicized health issues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:11811–11816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606609113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grossman G., Kim S., Rexer J., Thirumurthy H. Political Partisanship Influences Behavioral Responses to Governors’ Recommendations for COVID-19 Prevention in the United States. SSRN Electron J. 2020 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3578695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donald J. Trump - Twitter n.d. https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/1241367239900778501

- 5.Lagier J.-C., Million M., Gautret P., Colson P., Cortaredona S., Giraud-Gatineau A. Outcomes of 3,737 COVID-19 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine/azithromycin and other regimens in Marseille, France: A retrospective analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020:101791. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Million M., Lagier J.C., Gautret P., Colson P., Fournier P.E., Amrane S. Early treatment of COVID-19 patients with hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin: A retrospective analysis of 1061 cases in Marseille, France. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;35:101738. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.United States Coronavirus Worldometer n.d. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/us

- 8.Tracking Trump Morning Consult n.d. https://morningconsult.com/tracking-trump-2/

- 9.COVID-19 pandemic n.d. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/covid-19-pandemic

- 10.Republic M of H-A. Instruction N° 05/DGSSRH du 28 mars 2020 relative à la Prise en charge des cas compliqués de l’épidémie COVID-19 n.d.

- 11.CFM condiciona uso de cloroquina e hidroxicloroquina a critério médico e consentimento do paciente n.d. http://portal.cfm.org.br/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=28672:2020-04-23-13-08-36&catid=3

- 12.MBC مصر sur Twitter وزيرة الصحة تكشف تفاصيل البروتوكول العلاجي لكورونا: كل اللي بيتكلموا عليه في فرنسا وأمريكا وأوروبا إحنا بنستخدمه منذ البداية #الحكاية #MBCMASR. https://t.co/iOrVqo7R3Shttps://twitter.com/mbcmasr/status/1243662995999293440

- 13.Décret n° 2020-314 du 25 mars 2020 complétant le décret n° 2020-293 du 23 mars 2020 prescrivant les mesures générales nécessaires pour faire face à l’épidémie de covid-19 dans le cadre de l’état d’urgence sanitaire | Legifrance n.d. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichTexte.do?cidTexte=JORFTEXT000041755775&categorieLien=id

- 14.فلوچارت تشخیص و درمان بیماری COVID-19 در سطوح ارائه خدمات سرپایی و بستری n.d. https://irimc.org/Portals/0/NewsAttachment/.pdf

- 15.Ministry of Health - Kingdom of Morocco. Mise à jour de la définition de cas d’infection par le nouveau coronavirus “SARS-CoV-2” et protocole thérapeutique. n.d. https://www.covidmaroc.ma/Documents/2020/coronavirus/PS/covid-19Définitiondecasd’infection(24 mars2020).pdf (accessed June 25, 2020).

- 16.Stafford N. Covid-19: Why Germany’s case fatality rate seems so low. BMJ. 2020;369:5–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim D.H., Choe Y.J., Jeong J.Y. Understanding and interpretation of case fatality rate of coronavirus disease 2019. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35:1–3. doi: 10.3346/JKMS.2020.35.E137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prentice D.A., Miller D.T., Lightdale J.R. Asymmetries in attachments to groups and to their members: Distinguishing between common-identity and common-bond groups. 2006. [DOI]

- 19.Jost J.T., Sidanius J. Political Psychology. Key Readings. 2004 doi: 10.4135/9781446250556.n11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bennett D.J., Bennett J.D. The Psychology of Social Situations: Selected Readings. 1981. [DOI]

References

- 1.Roussel Y., Raoult D. Influence of conflicts of interest on public positions in the COVID-19 era: the case of Gilead Sciences. New Microbes New Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2020.100710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hersh E.D., Goldenberg M.N. Democratic and Republican physicians provide different care on politicized health issues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:11811–11816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606609113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grossman G., Kim S., Rexer J., Thirumurthy H. Political partisanship influences behavioral responses to governors’ recommendations for COVID-19 prevention in the United States. SSRN Electron J. 2020 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2007835117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trump D.J. HYDROXYCHLOROQUINE & AZITHROMYCIN, taken together, have a real chance to be one of the biggest game changers in the history of medicine. The FDA has moved mountains—thank You! Hopefully they will BOTH (H works better with A. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 21 March 2020 https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/1241367239900778501 (@realDonaldTrump)Twitter. 10:30 AM. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lagier J.C., Million M., Gautret P., Colson P., Cortaredona S., Giraud-Gatineau A. Outcomes of 3,737 COVID-19 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine/azithromycin and other regimens in Marseille, France: a retrospective analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Million M., Lagier J.C., Gautret P., Colson P., Fournier P.E., Amrane S. Early treatment of COVID-19 patients with hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin: a retrospective analysis of 1061 cases in Marseille, France. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;35:101738. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Worldometer . 2020. United States coronavirus cases.https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/us Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morning Consult. Tracking Trump. Available at: https://morningconsult.com/tracking-trump-2/.

- 9.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) 2020. COVID-19 pandemic.https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/covid-19-pandemic Available at: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.République Algérienne Démocratique et Populaire; Ministère de la Santé, de la Population et de la Réforme Hospitalière . 2020. Instruction n° 05/DGSSRH du 28 mars 2020 relative à la Prise en charge des cas compliqués de l’épidémie COVID-19.http://www.sante.gov.dz/images/Prevention/cornavirus/Instruc-5-COVID-Chlolo.PDF Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conselho Federal de Medicina (CFM) (Brasil). CFM condiciona uso de cloroquina e hidroxicloroquina a critério médico e consentimento do paciente, . Available at: https://portal.cfm.org.br/index.php?option=com_content&id=28672

- 12.MBC (@mbcmasr) . 27 March 2020. Covid19 Therapeutic Protocol - Egyptian Health Ministry #MBCMASR.https://twitter.com/mbcmasr/status/1243662995999293440 Twitter. 6:15 PM. [Google Scholar]

- 13.République Francaise; Légifrance . 2020. Décret n° 2020-314 du 25 mars 2020 complétant le décret n° 2020-293 du 23 mars 2020 prescrivant les mesures générales nécessaires pour faire face à l’épidémie de covid-19 dans le cadre de l’état d’urgence sanitaire.https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichTexte.do?cidTexte=JORFTEXT000041755775&categorieLien=id Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medical Council of the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRIMC). COVID 19 therapeutic protocol at outpatient and hospital service levels. Available at: https://irimc.org/Portals/0/NewsAttachment/%20%20%20%20%20%20%20.pdf.

- 15.Ministry of Health; Kingdom of Morocco . 2020. Mise à jour de la définition de cas d’infection par le nouveau coronavirus ‘SARS-CoV-2’ et protocole thérapeutique. Available at: http://www.covidmaroc.ma/Documents/2020/coronavirus/PS/Covid-19Prise%20en%20charge%20th%C3%A9rapeutique%20des%20cas%20confirm%C3%A9s%20(23mars2020).pdf Définition de cas d'infection (24 mars 2020).pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stafford N. COVID-19: why Germany’s case fatality rate seems so low. BMJ. 2020;369:5–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim D.H., Choe Y.J., Jeong J.Y. Understanding and interpretation of case fatality rate of coronavirus disease 2019. J Kor Med Sci. 2020;35:1–3. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prentice D.A., Miller D.T., Lightdale J.R. Asymmetries in attachments to groups and to their members: distinguishing between common-identity and common-bond groups. Personality Soc Psychol Bull. 1994;20:484–493. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jost J.T., Sidanius J., editors. Political psychology: key readings. Psychology Press; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bennett D.J. In: The psychology of social situations: selected readings. Chapter 3 – Making the Scene. Furnham A., Argyle M., editors. Pergamon; London: 1981. pp. 18–25. [Google Scholar]