Highlights

-

•

Developing countries require $2.5 trillion to meet immediate Covid-19 financing needs.

-

•

New data on IMF and regional financial arrangement activities since pandemic onset show the global financial safety net is not meeting these needs.

-

•

IMF and regional financial arrangements provided $90.11 billion in Covid-19 financing in the immediate aftermath of the crisis.

-

•

Datasets available for scholars and analysts to track trends and evaluate the impact of the global financial safety net on development outcomes.

Keywords: Global financial safety net, Global economic governance, International Monetary Fund, Regional financial arrangements, Covid-19

Abstract

Multilateral financial institutions have pledged to do whatever it takes to enable emerging market and developing countries to fill a $2.5 trillion financing gap to combat Covid-19 and subsequent economic crises. In this article, we present new datasets to track the extent to which multilateral financial institutions are meeting these goals, and conduct a preliminary assessment of progress to date. We find that the International Monetary Fund and the principal regional financial arrangements have made relatively trivial amounts of new financing available and have been slow to disburse the financing at their disposal. As of July 31, 2020, these institutions had committed $89.56 billion in loans and $550 million in currency swaps, totaling $90.11 billion—just 12.6% of their current capacity. The new datasets allow scholars, policymakers, and civil society to continue to track these trends, and eventually examine the impact of such financing on health and development outcomes.

1. Introduction

The ongoing global pandemic has been both a health crisis and economic calamity. The United States Federal Reserve swiftly backstopped the dollar system with 14 swap agreements and a repo facility. But these efforts were not extended to all but a handful of Emerging Market and Developing Economies (EMDEs). As a result, investors fled to this new safety for the dollar and the largest-ever capital outflows from EMDEs were recorded, leaving most struggling to defend their currencies, support economic activity, and invest in necessary health and social infrastructures. Both the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development estimate that EMDEs require $2.5tn to meet immediate financing needs (IMF, 2020o, UNCTAD, 2020).

Where can countries turn to receive such support? This is the task of the global financial safety net, a web of ‘financial resources and institutional arrangements that provide a backstop during a financial or economic crisis’ (Hawkins et al., 2014, p. 2). Notably, this includes central banks’ bilateral swap lines and countries’ foreign reserves. The former is only available to a handful of countries. The latter have been dwindling since the onset of the pandemic with attempts by governments to defend their currencies in light of capital outflows. Consequently, countries increasingly have no choice but to seek financial support from the third global financial safety net pillar: multilateral financial institutions. These encompass the IMF and regional financial arrangements (RFAs), like the Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization or Latin American Reserve Fund (Kring & Gallagher, 2019).

This article has two objectives. First, we examine recent policy promises on expanding the global financial safety net and compare these to pre-pandemic available resources. Second, we present data that offer an initial look into what the IMF and RFAs have been doing: which countries have benefited, what level of financing has been approved, and under what terms? To meet these objectives, we rely on official pronouncements of these institutions and on newly-developed datasets of lending activities. We only cover multilateral liquidity finance and not longer-term development financing, such as that provided by the World Bank and regional development banks, as coverage of these issues is available elsewhere (e.g., Duggan & Sandefur, 2020).

2. The global financial safety net since the onset of the pandemic

In March 2020, the G20 declared that ‘We commit to do whatever it takes and to use all available policy tools to minimize the economic and social damage from the pandemic, restore global growth, maintain market stability, and strengthen resilience’ (Wintour & Rankin, 2020, emphasis added). To date, these words have not been met with equally bold action. At time of writing, the IMF and all major RFAs have virtually the same lending capacity as they did in 2018, although conditions of access have occasionally changed. This section examines the evolution of global financial safety net activities since the onset of the pandemic, drawing on official pronouncements from the IMF and RFAs.

2.1. The International Monetary Fund

Member-countries can access IMF lending facilities on either concessional or non-concessional terms.1 Non-concessional financing is accessed through the General Resources Account: half of it is funded by a quota system that reflects countries’ relative position in the world economy (e.g., the United States quota is 17.45% while Burundi’s is 0.03%); the rest is funded through resource commitments from member-countries and institutions via the New Arrangements to Borrow scheme and Bilateral Borrowing Agreements (IMF, 2020k). The IMF’s oft-advertised ‘one-trillion firepower’ (IMF, 2020b), or about $970bn, are the joint resources available through these three elements. Yet, up to July 2020, EMDEs could access only about 40% of these resources, or $388.5bn (Gallagher et al., 2020), since each country’s access is governed by an annual limit of 145% of the quota and a cumulative limit of 435%.2 Accessing these funds typically requires an IMF program, disbursed in tranches over a period of up to four years following successive staff progress reviews linked to policy conditions (Stubbs & Kentikelenis, 2018).3 The only General Resources Account financing window that does not require a fully-fledged program is the Rapid Financing Instrument, but—prior to the pandemic—annual access limits to condition-free financing was lower, at 50% of quota.

Concessional financing is accessed through a series of Trust Accounts available to members that qualify, primarily on low-income criteria. First, the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust provides both a rapid access loan—the Rapid Credit Facility—and tranche-based loans subject to conditionality programs. It is funded predominantly via voluntary contributions from member-countries rather than quota subscriptions, and, in 2018, could support annual average lending of $1.7bn (IMF, 2020h). Prior to the pandemic, the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust had an annual access limit of 100% and cumulative limit of 300% of the quota, while the annual limit to the Rapid Credit Facility was 50% of quota. Second, the Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust provides debt-flow relief on debt service owed to the IMF to countries impacted by health or environmental emergencies for up to two years (IMF, 2020c). Initially financed with amounts left over from the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative, it was used to assist Ebola-afflicted countries with $100mil in 2015, leaving $200mil remaining in the trust (IMF, 2020m). Third, the Trust for Special Poverty and Growth Operations for the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries provides loans or grants with the ostensible aim of reducing debt levels under the Heavily Indebted Poor Country Initiative. It is financed through donors’ grant contributions, borrowings, or from transfers from other IMF accounts, and currently contains $339mil (IMF, 2019).

On March 2, 2020, IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva issued a joint statement with World Bank President David Malpass announcing that they would help address challenges posed by Covid-19 ‘with special attention to poor countries … us[ing] our available instruments to the fullest extent possible’ (IMF, 2020l). The IMF has since expanded facilities and introduced different types of support. First, it temporarily doubled annual access limits to the Rapid Financing Instrument and Rapid Credit Facility to 100% of quota, to meet expected demand of $100bn (IMF, 2020e). It then temporarily raised overall annual access limits on the General Resources Account to 245% and Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust to 150% of quota, and suspended limits to the number of disbursements allowed under the Rapid Credit Facility (IMF, 2020i). These changes do not represent an increase in the overall resource pool in the General Resources Account or even the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust. If eligible countries for the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust all used their increased access, lendable resources would reach their limits, leaving little left for further concessional financing—hence the IMF’s appeal for ‘expedited and ambitious fundraising efforts’ to replenish the Trust (IMF, 2020e). Second, the IMF revamped and expanded the Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust so that it could be used for debt relief, thereby releasing domestic finances to address the adverse economic impact of Covid-19 (IMF, 2020n). It launched a fundraiser to replenish the trust aiming to reach $1.4bn (IMF, 2020c); thus far, the UK pledged $185mil and Japan $100mil, and so can provide about $500mil total. These funds will be used to cover the short-term debt relief that the IMF offered low-income countries in April (IMF, 2020q). Even so, this may not constitute a net increase on financing available for EMDEs if donors are diverting their existing official development assistance budgets (Munevar, 2020). Third, the IMF approved a new tranche-based instrument from the General Resources Account, the Short-Term Liquidity Line, for countries with ‘very strong policies and fundamentals’ (IMF, 2020p), but—again—this does not represent an increase to the underlying resource pool.4

Taken together, adjustments to the IMF’s financial architecture since the Covid-19 joint statement—the temporarily increased access limits, the new Short-Term Liquidity Line, and revamped Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust—are underwhelming. The only genuinely fresh funding is the $285mil committed to the Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust, a mere fraction of existing lending firepower and far short of the acknowledged $2.5tn need.

2.2. Regional financial arrangements

For over three decades, the IMF was the only international institution providing short-term crisis finance. However, RFAs have recently grown to become a major component of the global financial safety net, boasting a combined lending capacity that rivals the IMF’s—at roughly $1tn (Gallagher et al., 2020, Mühlich et al., 2020). RFAs provide member-countries with either loans from paid-in capital or currency swaps, the majority of which are multilateralized.5 In the case of loans, maximum potential borrowing amounts and repayment timetables are determined by country quotas and a borrowing multiple.6 Prior to the pandemic, about one-third of this lending capacity was available to EMDEs (Kring et al., 2020), mainly via seven RFAs: $201.6bn from Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization; $100.0bn from Contingent Reserve Arrangement; $9.0bn from North American Framework Agreement; $5.4bn from Eurasian Fund for Stabilization and Development; $4.8bn from Arab Monetary Fund; $6.8bn from Latin American Reserve Fund; and $2.0bn from South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation.

The IMF and RFAs have formally engaged on an annual multilateral basis since 2016, presenting an opportunity to enhance the global response to the pandemic. On April 21, 2020, several RFAs and IMF Managing Director Georgieva issued a joint statement on cooperation efforts to mitigate the economic impact of Covid-19.7 No specific commitments were made as a group, only a non-binding commitment on ‘working together closely’ to exchange information on the needs of member-countries, to coordinate assistance across regions, and to co-finance wherever appropriate and feasible (IMF, 2020r). While the Fund’s adjustments to Covid-19 were marginal, public commitments and efforts undertaken by RFAs are even less so. Their initiatives since the beginning of the crisis are summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1.

RFA activities (1 February—31 July 2020).

| Regional Financial Arrangement | Members | Policies or initiatives | EMDEs share ($ billion) | Approved or disbursed financing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization | Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Japan, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand, Vietnam | Intensified regional surveillance efforts to provide timely risk assessments and policy advice | 201.6 | None |

| Contingent Reserve Arrangement | Brazil, China, India, Russia, South Africa | None | 100.0 | None |

| North American Framework Agreement | Canada, Mexico, United States | None | 9.0 | None |

| Eurasian Fund for Stabilization and Development | Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Russia, Tajikistan | Developing an ad-hoc emergency lending instrument and proposing $3mil in health-related grants to member-countries for Covid-19-related hospitals and medical equipment | 5.4* |

|

| Arab Monetary Fund | Algeria, Bahrain, Comoros, Djibouti, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, Yemen | Issued general guidelines for central banks to deal with Covid-19 | 4.8 |

|

| Latin American Reserve Fund | Bolivia, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, Venezuela | Developing an alternative instrument to its current credit lines for pandemics and natural disasters | 6.8 |

|

| South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation | Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka | Finalized swap arrangements for Maldives and Sri Lanka | 2.0 |

|

| TOTAL | $329.6bn | $2.03bn |

* Russian share excluded because it acts strictly as a donor to the Eurasian Fund for Stabilization and Development.

The ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office—the secretariat-cum-surveillance unit of the Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization—noted it had intensified regional surveillance efforts to provide ‘timely risk assessments and policy advice’ and committed to continue working with member-country authorities to ‘enhance the operational readiness of the CMIM [Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization]’ (AMRO, 2020). Nevertheless, although operational preparedness efforts had been undertaken, including test-runs for both IMF-linked and delinked funds, ASEAN+3 member-countries have neither publicly declared Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization active nor signaled its preparedness to assist member-countries in a time of crisis.

The Eurasian Fund for Stabilization and Development is developing an ad-hoc emergency lending instrument that will be similar in nature to the IMF’s Rapid Financing Instrument.8 In addition, the Fund’s Council is currently reviewing a proposal for several health-related grants to member-states to fund hospitals and medical equipment.9

The Arab Monetary Fund also provided policy advice as their response to Covid-19, publishing a set of advisory principles for central banks to promote economic activity and foster financial stability (AMF, 2020a). Additionally, the Fund is receiving requests for member-country financing—on top of new loans for Egypt, Morocco, and Tunisia described in Section 3—and “processing the requests through expeditious procedures” (AMF, 2020d).

The Latin American Reserve Fund publicly committed to mobilizing its capital to combat Covid-19′s economic effects, and is also seeking to enroll new members to grow its resource base (Uribe, 2020). Most notably, the Fund will leverage its Aa2 credit rating to issue up to $4.35bn in bonds “to fund loans to central banks in the region” that face balance of payments problems due to the impact of Covid-19 (Fieser, 2020), and could tap credit markets within two months. The Fund is also exploring the potential to create a new credit line, similar to the IMF’s Rapid Financing Instrument, to help member-countries combat Covid-19. In addition, Ecuador has solicited a $418mil loan from the Latin American Reserve Fund, described in Section 3.

Finally, the remaining RFAs provided little guidance or commitments with respect to their pandemic response, aside from the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation successfully activating currency swaps described in Section 3. Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi emphasized the importance of the Contingent Reserve Arrangement, but was vague on its specific role vis-à-vis the crisis (Government of China, 2020).

Overall, adjustments to the RFA’s financial architecture and commitments are varied, yet minimal. The Latin American Reserve Fund’s desire to increase its resources and membership base and the Eurasian Fund for Stabilization and Development's proposed grants are bright spots. However, the Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization seems to still be an aspirational—as opposed to operational—RFA at the present juncture.

3. The global financial safety net response to the Covid-19 crisis

Since the joint statement in March, the IMF has approved financing requests for 84 countries totaling $88.1bn, of which $36.2bn has been disbursed.10 RFAs have committed just eight loans totaling $1.48bn, activated one currency swap for $150mil, and formalized an additional swap arrangement for $400mil.

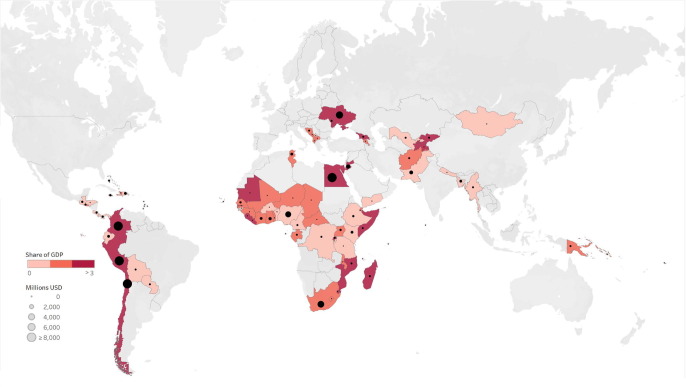

In Fig. 1 , we present countries’ IMF financing approved between 2 March and 31 July 2020, as a share of GDP (color-shaded) and in absolute amount (dotted). Of the countries with approved requests, 27 received less than 1% of GDP, but 10 received over 3%.11 In nominal terms, Chile obtained the largest loan ($23.9bn), followed by Peru ($11.0bn) and Colombia ($10.8bn); Egypt, Ukraine, South Africa, Nigeria, Jordan, Pakistan and Ghana also had loans of over $1bn approved. The majority of approved requests were for Sub-Saharan African countries, where a total of 35 countries had financing approved from 64 facilities. To develop a first-hand understanding of how this money was put into use, Box 1 presents initial evidence from Ghana—one of the countries that received financial support soon after the onset of the pandemic.

Box 1. IMF support for Ghana.

Prior to the Covid-19 crisis, Ghana was assessed as being at high risk of debt distress—with government debt at 63.2% of GDP at end-2019 (IMF, 2020f, p. 11). The pandemic affected the economy even before the country’s first confirmed case on March 12, via lower commodity prices, supply chain disruptions with China, and declines in tourism, trade, and foreign investment. As the virus spread through the country and the government planned mitigation efforts, a $1.33bn financing gap emerged: total external financing requirements stood at $6.18bn—including $1.09bn in debt service owed to private creditors (World Bank, 2020)—with only $4.85bn available (IMF, 2020f, p. 19). On April 6, Ghanaian officials requested IMF assistance of $1bn from the Rapid Credit Facility to address the gap (and approached the World Bank and African Development Bank for the remaining $0.33bn), which the IMF approved on April 13 and disbursed three days later (IMF, 2020f). This assistance funded an emergency Covid-19 spending package of $266mil (0.4% of GDP), composed of $100mil in extra health expenditures and a $166mil Coronavirus Alleviation Program to support the Ghanaian economy. But it is unclear how the remaining financing has been used. Because the Rapid Credit Facility was disbursed as budget support, and debt repayments draw from the same pool of resources, it has prompted criticism by civil society that the IMF is bailing out private lenders (Jubilee Debt Campaign, 2020).

Fig. 1.

IMF approved financing, 2 March—31 July 2020.

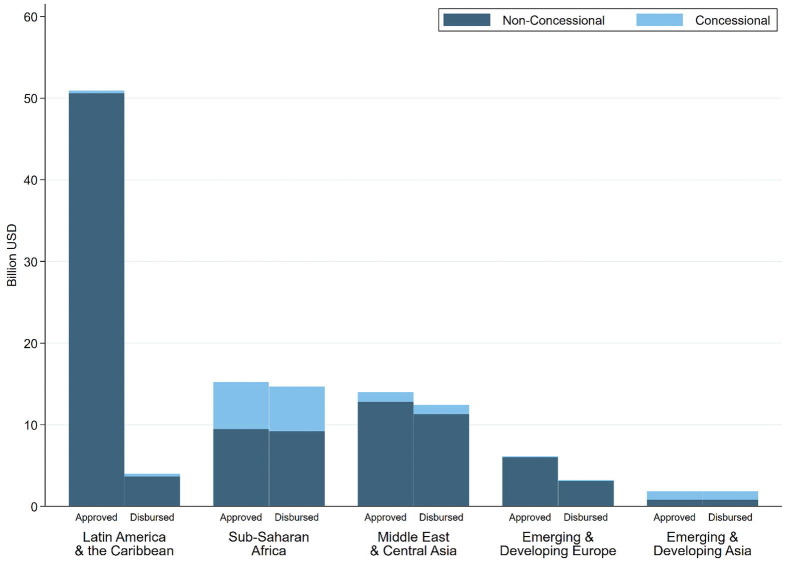

As shown in Fig. 2 , $79.8bn funds approved since March were non-concessional compared to $8.3bn concessional. By region, Latin America and the Caribbean had the most financing approved, primarily non-concessional, but less than 10% has been disbursed. Sub-Saharan Africa had the next-most financing approved, with comparable amounts in concessional and non-concessional funding, almost all of which has been disbursed.

Fig. 2.

IMF concessional versus non-concessional financing by region, 2 March—31 July 2020.

Financing approvals and disbursements are summarized by facility in Table 2 . By frequency, greatest use is being made from the three facilities revamped for the pandemic: the Rapid Financing Instrument, Rapid Credit Facility, and Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust, approving 38, 47, and 28 requests respectively. However, 36 countries have now reached 100% of the quota, so they are coming up against the access limits for rapid disbursement facilities. In contrast, there were no approvals for the new Short-Term Liquidity Line. In terms of total resources approved, over half is accounted for by the Flexible Credit Line, approved for Chile, Colombia, and Peru, but none of this has been disbursed. We return to these issues in the conclusion.

Table 2.

IMF approved funding by facility to EMDEs (2 March—31 July 2020).

| Facility | Mode of delivery | Number approved* | Total approved ($ billion) | Total disbursed ($ billion)** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Concessional Facilities | ||||

| Rapid Financing Instrument | Rapid | 38 | 21.72 | 20.09 |

| Short-Term Liquidity Line | Tranched | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Precautionary and Liquidity Line | Tranched | 0 | 0 | 2.93† |

| Flexible Credit Line | Tranched | 3 | 45.73 | 0 |

| Stand-By Arrangement | Tranched | 4 | 10.51 | 4.60 |

| Extended Fund Facility | Tranched | 4 | 1.82 | 0.55 |

| Total non-concessional | 49 | 79.78 | 28.17 | |

| Concessional Facilities | ||||

| Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust | Rapid | 28 | 0.25 | 0.24 |

| Rapid Credit Facility | Rapid | 47 | 7.36 | 7.05 |

| Extended Credit Facility | Tranched | 5 | 0.59 | 0.60† |

| Standby Credit Facility | Tranched | 1 | 0.09 | 0.13† |

| Total concessional | 81 | 8.29 | 8.02 | |

| TOTAL | 130 | $88.08bn | $36.18bn | |

Notes:

*Total approved financing requests includes new agreements and augmentations of pre-existing programs. Countries received funds from more than one facility.

**Total disbursed financing includes disbursements on new agreements and on pre-existing programs.

†Disbursed financing is greater than approved financing for Precautionary and Liquidity Line, Extended Credit Facility, and Standby Credit Facility rows because disbursements also pertain to programs approved prior to 2 March 2020.

The IMF has provided non-debt creating flows through the Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust, the only facility that shows a net increase of available funds to EMDEs since the pandemic began. Although significant for the countries involved, the size of the Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust approved financing is trivial in global terms: $251mil. These funds return to the IMF, as they can only be used for IMF debt service relief.

Since February 1, 2020, there have been six new loans by RFAs to member-countries to mitigate Covid-19’s economic effects, two disbursements on loans that predate the crisis, and two swap arrangements activated. In total, RFAs have committed $2.03bn of $329.6bn in available resources, or only 0.62%.

The Arab Monetary Fund issued new loans in May to Morocco for $127mil and Tunisia for $59mil in order to ‘stimulate the economy and provide liquidity in order to contain the negative effects of the virus outbreak’ (AMF, 2020b, AMF, 2020c). The Arab Monetary Fund also disbursed second tranches of pre-existing arrangements to Jordan ($38mil) and Sudan ($45mil), with their corresponding press releases including similar statements on Covid-19 support. Additionally, in July, the Arab Monetary Fund issued a new loan to Egypt for $639mil to combat the effects of the crisis (AMF, 2020d).

At the Latin American Reserve Fund, Ecuador requested a loan for $418mil as a liquidity facility direct to the central bank, submitted in parallel to the IMF Rapid Financing Instrument request. While the negotiations began in March 2020, and Ecuador’s central bank claims that the request pre-dated the public health emergency, the effects of the global economic slowdown due to Covid-19 were clearly already impacting the country (Silva, 2020). Unlike previous Latin American Reserve Fund loans, Ecuador was negotiating in parallel with the IMF and both institutions shared non-confidential information. Ecuador’s central bank is awaiting final approval, which the Latin American Reserve Fund will sign-off on once they receive information on internal procedures to receive the disbursement. In Box 2, we describe how Ecuador will use this funding.

Box 2. IMF and RFA support for Ecuador.

Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, Ecuador was facing significant economic turmoil due to mass protests against the government, the impact of fiscal consolidation measures, and contracting domestic demand (IMF, 2020d, p. 5). The economic effects of Covid-19 exacerbated Ecuador’s precarious economic position due to a significant drop in oil prices and a projected financing gap of $8.38bn (IMF, 2020d, p. 13). In March, Ecuador approached the IMF for $644mil under the Rapid Financing Instrument, approved in May, which covered approximately 8% of Ecuador’s projected financing gap (IMF, 2020d, p. 21). The IMF noted Ecuador will need to increase public spending by $600mil (0.6% of GDP)—$350mil for healthcare spending and $250mil for social assistance (IMF, 2020d, p. 8)—but also advocated “continued commitment to ambitious, yet credible, fiscal consolidation after pressures from the crisis subsides” (IMF, 2020d, p. 15). IMF financing catalyzed funds from other multilaterals and facilitated negotiations with external creditors. In July, Ecuador reached a deal with half its bondholders to restructure $17.4bn in sovereign debt, saving the country over $1.5bn (Long & Smith, 2020). Ecuador also obtained a $506mil loan from the World Bank in May and an additional $260mil in July. Finally, Ecuador negotiated a Latin American Reserve Fund loan of $418mil pending final approval, which will be used to strengthen reserves and increase liquid resources, either to meet the demand for cash and transfers abroad, or for operations of the central bank such as credit letters (Silva, 2020). Even so, the global financial safety net is yet to bridge the total financing gap, and additional resources for healthcare and social assistance are minimal.

The Eurasian Fund for Stabilization and Development approved two official borrowing requests from member-countries since February 1, 2020, Kyrgyz Republic ($100mil) and Tajikistan ($50mil). The loans are for 20 years, include a 10-year grace period, and have a 1% interest rate (EFSD, 2020a, EFSD, 2020b).

In terms of currency swaps, as part of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation, the Maldives recently drew $150mil from a swap agreement and Sri Lanka secured a $400mil swap facility, both with the Reserve Bank of India (Press Trust of India, 2020a, Press Trust of India, 2020b). Above and beyond existing arrangements, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York entered into a temporary swap arrangement with Banco de Mexico. While not officially part of the North American Framework Agreement, the additional funds add $60bn in a liquidity swap line to the existing $9bn swap line between Mexico and the United States (New York Fed, 2020).

4. Conclusions

It is widely acknowledged that EMDEs need a rapid $2.5tn to meet their liquidity needs. According to the data presented here, the institutions of the global financial safety net fell short in approving and disbursing liquidity so that EMDEs could fight the virus, protect the vulnerable, and mount a recovery—providing just over $89.56bn in loans and two currency swaps totaling $550mil. These outlays represent only 12.6% of available financing for EMDEs across these institutions.12 Our accompanying datasets enable tracking the extent to which such financing is forthcoming: available for the IMF in the supplementary appendix to this article and at www.imfmonitor.org, and for RFAs at www.gfsntracker.com. Moreover, these datasets will allow scholars and analysts to examine the extent to which there are causal relationships between this financing and development outcomes.

The need for rapid financial support in developing countries is far greater than the amounts available. The amounts disbursed are also significantly less than what is available, and take predominantly the form of IMF loans. Without addressing growing debt burdens, and with the acknowledgement that many of the countries with approved financing will graduate to fully-fledged programs with policy conditions (IMF, 2020e), the IMF’s terms of support might create further problems down the line: under current restrictions on cumulative use, the rapid low-conditionality loans will need to be repaid within 3 to 10 years (IMF, 2020j, IMF, 2020g).

Not only were 25 loans approved to countries evaluated by the IMF as at high risk or in debt distress, they were done so under assumptions of a bounce-back in economic growth and expenditure-reducing fiscal consolidation. The great uncertainty surrounding the scale of pandemic-induced economic dislocations raise concerns about the ability of the IMF to conduct debt sustainability assessments in this period (Gelpern et al., 2020, Rediker and Crebo-Rediker, 2020).

Concessional financing facilities are limited and would run out if all eligible countries were to seek full access under the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust. Once access limits on rapid facilities are exhausted, countries will still need liquidity support. With EMDEs facing limited use of RFAs, the financing may come through the IMF’s regular programs, which include ample and strict conditions which have been shown to have adverse socio-economic effects (Forster et al., 2019a; Oberdabernig, 2013), including for health systems and population health (Forster et al., 2019b; Stubbs et al., 2017).

Over half of all approved IMF non-concessional financing has not been disbursed, almost all under the Flexible Credit Line, a two-year program without ex post policy conditions. A likely explanation for why countries requested financing they do not intend to use is to signal policy credibility and boost investor confidence in the economy (Chapman et al., 2017, Stubbs et al., 2016). Meanwhile, the absence of approvals under the new Short-Term Liquidity Line is because of stringent ex ante conditions that most countries do not fulfil.

The historical record thus far indicates that the global financial safety net primarily consists of IMF loans approved in an era of great uncertainty. The only certainty is that countries will end up heavily indebted to the IMF, at a time when the cost of addressing the pandemic will only have increased, and—short of successful fundraising from high-income countries—limited concessional facilities will be available.

At this early stage, data unavailability precludes us from offering a systematic analysis of how new financing is being used. Nonetheless, our case studies of Ghana and Ecuador provide an early indication. They show that only a fraction of these resources are contributing to additional healthcare spending and social assistance, with most of it being spent elsewhere, such as covering debt repayments to private creditors. There is also some indication that, beyond the initial pandemic response, the IMF continues to include fiscal consolidation as a policy condition for regular programs. For example, in a Stand-By Arrangement with Egypt, the IMF set a floor on the cumulative primary fiscal balance of about $940mil in surplus (15bn Egyptian pounds) by March 2021 (IMF, 2020a, p. 38)—at a time when governments around the world are engaging in extensive public spending to halt the spread of the pandemic. Future research can explore these issues in greater depth.

This article is far from the last word on these questions, but has developed a tracking system to evaluate the magnitude of these loans. If our preliminary conclusions are correct, multilateral financial institutions will have to meet this financing gap through other means. Those could include an increase in the base capital of the IMF and RFAs, the issuance of Special Drawing Rights at the IMF, and significant debt relief (Gallagher et al., 2020). Until such measures are considered and come to fruition, the world community is failing to deliver its own assessment of current gaps and is falling far short of doing ‘whatever it takes.’

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Access is not guaranteed, and relies—among other elements—on debt sustainability requirements (Lang & Presbitero, 2018).

This access limit does not set an absolute ceiling on financing a member can obtain. Rather, it serves as a threshold beyond which a set of procedural requirements are triggered under an exceptional access framework (IMF, 2016), as was the case with Argentina in 2018.

The Flexible Credit Line does not carry conditions but countries must meet stringent qualification criteria. Countries must still complete a review to access the resource for a second year.

A new IMF lending facility has been mooted since after the 2008 financial crisis. The crisis revealed that United States Fed Swaps were largely unavailable to EMDEs, so they pushed for a multilateral currency swap facility at the IMF. Potential schemes were elaborate on by IMF staff (IMF, 2017), but a proposal for a swap facility was eventually rejected by the IMF Executive Board.

Multilateralized currency swaps are a network of bilateral currency swap agreements converted into a single multilateral agreement, which acts as a currency pool where decisions on disbursements are made collectively among member-countries (Grabel, 2019).

Various instruments and RFAs allow countries to borrow at varying multiples of their paid-in and/or quota resources.

The RFAs that signed the joint statement were the European Stability Mechanism, ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office, Latin American Reserve Fund, Eurasian Fund for Stabilization and Development, and Arab Monetary Fund.

Author interview with Eurasian Fund for Stabilization and Development official.

Author interview with Eurasian Fund for Stabilization and Development official.

This value includes disbursements of $4.2bn under programs approved prior to the pandemic.

Countries that had IMF financing approved of more than 3% of GDP include Chile (8.1%), Somalia (8.0%), Peru (4.8%), Gambia (4.0%), Jordan (3.8%), Sierra Leone (3.8%), São Tomé and Príncipe (3.4%), Ukraine (3.3%), Jamaica (3.3%), and Colombia (3.3%).

The EMDE portion of IMF funds available is $388.5bn and of RFAs is $329.6bn. Combined loans and swaps to date are $90.11bn, or 12.6%, of the total available liquidity to EMDEs from the IMF and RFAs.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105171.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- AMF. (2020). Arab Monetary Fund general guidelines for central banks to deal with COVID-19 implications on financial stability. Abu Dhabi.

- AMF. (2020, May 20). Arab Monetary Fund extends a new automatic loan to the Kingdom of Morocco, with an amount of Arab Accounting Dinar 30.844 million, the equilvalent of approximately USD 127 million, in the face of current circumstances. AMF Press Release. https://www.amf.org.ae/en/content/arab-monetary-fund-extends-new-automatic-loan-kingdom-morocco-amount-arab-accounting-dinar.

- AMF. (2020, June 5). The Arab Monetary Fund extends to the Republic of Tunisia a new loan, within the framework of the Structural Adjustment Facility, with an amount of Arab Accounting Dinar 23.968 million, the equivalent of approximately USD 98 million, to support a reform. AMF Press Release. https://www.amf.org.ae/en/content/arab-monetary-fund-extends-republic-tunisia-new-loan-within-framework-structural-adjustment.

- AMF. (2020, July 29). The Arab Monetary Fund extends to the Arab Republic of Egypt a new loan, within the framework of the Structural Adjustment Facility, with an amount of Arab Accounting Dinar 153.475 million, the equivalent of approximately USD 639 million. AMF Press Release. https://www.amf.org.ae/en/content/arab-monetary-fund-extends-arab-republic-egypt-new-loan-within-framework-structural.

- AMRO. (2020, May 8). Speech by Mr. Toshinori Doi, Director, ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office (AMRO) at the launch of the Boao Forum Asia 2020 flagship report & symposium on Asian development prospects & challenges under the pandemic. https://www.amro-asia.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Speech-by-AMRO-Director-at-BFA-Symposium-on-Asia-Prospects-and-Challenges.pdf.

- Chapman T., Fang S., Li X., Stone R.W. Mixed signals: IMF lending and capital markets. British Journal of Political Science. 2017;47(2):329–349. doi: 10.1017/S0007123415000216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan, J., & Sandefur, J. (2020, April 14). Tracking the World Bank’s response to COVID-19. Center for Global Development. https://www.cgdev.org/blog/tracking-world-banks-response-covid-19.

- EFSD. (2020a, August 3). The EFSD to provide a financial credit to Tajikistan and grants for health projects. EFSD Press Release. https://eabr.org/en/press/news/the-efsd-to-provide-a-financial-credit-to-tajikistan-and-grants-for-health-projects/.

- EFSD. (2020b, August 7). The EFSD to provide US $100 million to the Kyrgyz Republic to fight the consequences of the pandemic. EFSD Press Release. https://eabr.org/en/press/news/the-efsd-to-provide-us-100-million-to-the-kyrgyz-republic-to-fight-the-consequences-of-the-pandemic/.

- Fieser, E. (2020, July 3). Latin America Fund may provide up to $6.8 billion in support. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-07-02/latin-america-fund-readying-6-8-billion-in-support-amid-crisis.

- Forster T., Kentikelenis A., Reinsberg B., Stubbs T., King L. How structural adjustment programs affect inequality: A disaggregated analysis of IMF conditionality, 1980–2014. Social Science Research. 2019;80:83–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster T., Kentikelenis A., Stubbs T., King L. Globalization and health equity: The impact of structural adjustment programs on developing countries. Social Science & Medicine. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, K. P., Gao, H., Kring, W. N., Ocampo, J. A., & Volz, U. (2020). Safety first: Expanding the global financial safety net in response to COVID-19. GEGI Working Paper (No. 37). Boston, MA.

- Gelpern, A., Hagan, S., & Mazarei, A. (2020, April 7). Debt standstills can help vulnerable governments manage the COVID-19 crisis. PIIE COVID-19 Blog Series. https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues-watch/debt-standstills-can-help-vulnerable-governments-manage-covid.

- Government of China. (2020, April 28). State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi attends the Extraordinary Meeting of BRICS Ministers of Foreign Affairs. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/t1774757.shtml.

- Grabel I. Continuity, discontinuity and incoherence in the Bretton Woods Order: A Hirschmanian reading. Development and Change. 2019;50(1):46–71. doi: 10.1111/dech.12469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, A., Rahman, J., & Williamson, T. (2014). Is the global financial safety net at a tipping point to fragmentation? The Treasury Economic Roundup (Issue 1). Canberra.

- IMF. (2016). Review of access limits and surcharge policies. Washington, DC: IMF Policy Paper.

- IMF. (2017). Adequacy of the global financial safety net—considerations for fund toolkit reform. Washington, DC: IMF Policy Paper.

- IMF. (2019). Financial statements for the quarters ended October 31, 2019, and 2018. Washington, DC.

- IMF. (2020). Arab Republic of Egypt: Request for a 12-month Stand-By Arrangement. Washington, DC.

- IMF. (2020). At a glance: The IMF’s firepower. https://www.imf.org/en/About/infographics/imf-firepower-lending.

- IMF. (2020). Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust. IMF Factsheet. https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/Sheets/2016/08/01/16/49/Catastrophe-Containment-and-Relief-Trust.

- IMF. (2020). Ecuador: Request for purchase under the Rapid Financing Instrument and cancellation of arrangement under the Extended Fund Facility. Washington, DC.

- IMF. (2020). Enhancing the emergency financing toolkit—Responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. Washington, DC: IMF Policy Paper.

- IMF. (2020). Ghana: Request for disbursement under the Rapid Credit Facility. Washington, DC.

- IMF. (2020). IMF Rapid Credit Facility (RCF). IMF Factsheet. https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/Sheets/2016/08/02/21/08/Rapid-Credit-Facility.

- MF. (2020h). IMF support for low-income countries. IMF Factsheet. https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/IMF-Support-for-Low-Income-Countries.

- IMF. (2020i). Temporary modifications to the Fund’s annual access limits. Washington, DC: IMF Policy Paper.

- IMF. (2020). The IMF’s Rapid Financing Instrument (RFI). IMF Factsheet. https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/Sheets/2016/08/02/19/55/Rapid-Financing-Instrument

- IMF. (2020). Where the IMF gets its money. IMF Factsheet. https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/Where-the-IMF-Gets-Its-Money

- IMF. (2020, March 2). Joint Statement from Managing Director, IMF and President, World Bank Group. IMF Press Release. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/03/02/pr2076-joint-statement-from-imf-managing-director-and-wb-president.

- IMF. (2020, March 4). Joint press conference on Covid-19 by IMF Managing Director and World Bank Group President. IMF Transcript. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/03/05/tr030420-imf-wb-joint-press-conference-on-corvid-19

- IMF. (2020, March 27). IMF enhances debt relief trust to enable support for eligible low-income countries in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. IMF Press Release. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/03/27/pr20116-imf-enhances-debt-relief-trust-to-enable-support-for-eligible-lic-in-wake-of-covid-19.

- IMF. (2020, March 27). Transcript of press briefing by Kristalina Georgieva following a conference call of the International Monetary and Financial Committee. IMF Transcript. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/03/27/tr032720-transcript-press-briefing-kristalina-georgieva-following-imfc-conference-call.

- IMF. (2020, April 15). IMF adds liquidity line to strengthen COVID-19 response. IMF Press Release. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/04/15/pr20163-imf-adds-liquidity-line-to-strengthen-covid-19-response.

- IMF. (2020, April 15). IMF Executive Board approves immediate debt service relief for 25 eligible low-income countries. IMF Press Release. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/04/16/pr20165-board-approves-immediate-debt-service-relief-for-25-eligible-low-income-countries.

- IMF. (2020, April 21). The Managing Director of the IMF and the heads of the RFAs emphasize their readiness to cooperate to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on the global economy. IMF Press Release. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/04/21/pr20177-imf-managing-director-heads-rfa-readiness-cooperate-mitigate-impact-covid-19-global-economy.

- Jubilee Debt Campaign. (2020). IMF loans bailing out private lenders during the Covid-19 crisis. London.

- Kring W.N., Gallagher K.P. Strengthening the foundations? Alternative institutions for finance and development. Development and Change. 2019;50(1):3–23. doi: 10.1111/dech.12464. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kring, W. N., Mühlich, L., Fritz, B., Gallagher, K. P., & Pitts, J. D. (2020). Global financial safety net tracker. http://www.gfsntracker.com/.

- Lang V.F., Presbitero A.F. Room for discretion? Biased decision-making in international financial institutions. Journal of Development Economics. 2018;130:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2017.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Long, G., & Smith, C. (2020, August 4). Ecuador clinches $17.4bn debt deal with bondholders. The Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/567d51c2-4410-4fdd-a59b-7227077cb922

- Mühlich, L., Fritz, B., Kring, W. N., & Gallagher, K. P. (2020). The global financial safety net tracker: Lessons for the COVID-19 crisis from a new interactive dataset. GEGI Policy Brief (No. 10). Boston, MA.

- Munevar, D. (2020, April 14). IMF debt relief: Implications for developing countries. European Network on Debt and Development. https://eurodad.org/Entries/view/1547173.

- New York Fed. (2020, March 19). Central Bank swap arrangements. https://www.newyorkfed.org/markets/international-market-operations/central-bank-swap-arrangements.

- Oberdabernig D. Revisiting the effects of IMF programs on poverty and inequality. World Development. 2013;46:113–142. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.01.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Press Trust of India. (2020, April 24). Sri Lanka to seek $400mn debt swap facility from RBI to meet short term financial needs. The Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/finance/sri-lanka-to-seek-400-million-financial-facility-from-rbi-to-meet-short-term-needs/articleshow/75347534.cms.

- Press Trust of India. (2020, April 28). COVID-19: India extends USD 150 million foreign currency swap support to Maldives. The New Indian Express. https://www.newindianexpress.com/world/2020/apr/28/covid-19-india-extends-usd-150-million-foreign-currency-swap-support-to-maldives-2136548.html

- Rediker, D. A., & Crebo-Rediker, H. (2020, April 14). COVID-19 uncertainty and the IMF. Brookings Blog. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2020/04/14/covid-19-uncertainty-and-the-imf/.

- Silva, V. (2020, April 23). El Banco Central gestiona un préstamo con el FLAR por USD 418 millones. El Comercio. https://www.elcomercio.com/actualidad/flar-credito-banco-central-emergencia.html.

- Stubbs T., Kentikelenis A. Conditionality and sovereign debt: An overview of human rights implications. In: Bantekas I., Lumina C., editors. Sovereign debt and human rights. Oxford University Press; 2018. pp. 359–380. [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs T., Kentikelenis A., King L. Catalyzing aid? The IMF and donor behavior in aid allocation. World Development. 2016;78:511–528. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.10.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs T., Kentikelenis A., Stuckler D., McKee M., King L. The impact of IMF conditionality on government health expenditure: A cross-national analysis of 16 West African nations. Social Science & Medicine. 2017;174:220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD. (2020). From the great lockdown to the great meltdown: Developing country debt in the time of Covid-19. Trade and Development Report Update. Geneva.

- Uribe, J. D. (2020, April 20). FLAR ante crisis Covid-19. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FZ1eGLv32Fs.

- Wintour, P., & Rankin, J. (2020, March 26). G20 leaders issue pledge to do “whatever it takes” on coronavirus. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/26/g20-leaders-issue-pledge-to-do-whatever-it-takes-on-coronavirus.

- World Bank. (2020). International Debt Statistics. https://datatopics.worldbank.org/debt/ids/.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.