Abstract

After wide consultation with trainees, trainers, employers and other stakeholders, the new General Surgical Curriculum was approved earlier this year and will be implemented from 4 August 2021. It will be outcome based and will be the biggest change in surgical training since 2007. Trainees can progress at their own rate and complete when they have acquired the capabilities of a Day-1 consultant in general surgery with a special interest. The Multiple Consultant Report (MCR) is new and has been developed as the main assessment tool for this outcomes-based curriculum. Assessment in the MCR will be on progress from the ability to only observe at the start of training, to performance at the level of Day-1 consultant in the complex, integrated skills needed for the day-to-day performance of the role in each of the areas of the job (the Capabilities in Practice). The MCR and trainee self assessment will improve feedback and allow specific and bespoke agreed learning objectives to be more easily developed and delivered, and faster but safe training for many. New training pathways have been developed, emphasizing the commonality of emergency general surgery, but also developing special interests reflecting the needs of patients and the service.

Keywords: Curriculum, feedback, general surgery, self assessment

The Key Changes.

Whatever your role, trainee or trainer, these key changes will affect you.

A truly outcomes based curriculum – training ends when you are ready to be a Day-1 consultant

A new phased training pathway producing a General Surgeon with a special interest

Generic Professional Capabilites must be acquired by all doctors

Capabilites in Practice (cover everything a Day-1 consultant needs to perform that part of the job and integrates knowledge, clinical, professional and technical skills into a functioning whole) are the major areas of development through training.

New assessments include:

The Multiple Consultant Report featuring:

-

•

Generic Professional Capabilities

-

•Capabilities in Practice

- ○ Trainee self assessment

- ○ Progress through supervision levels

- ○ Critical progression points and phases of training

- ○ Critical Conditions and Index Procedures with linking to WBAs

- ○ WBAs according to need rather than number

Ready for a change

Surgeons have been training for hundreds of years, most of the time through apprenticeship, with training ending when the trainee was deemed safe to perform independently. It was not until the last decade of the century that even rudimentary curricula existed. In 2007, with Modernising Medical Careers,1 much more defined curricula and assessment in the work place were introduced. The laudable aim was to improve feedback through repeated small assessments of the performance of various tasks described in the syllabus, across clinical skills, professional skills and technical skills. Some knowledge was examined in the work place, but the main assessment of knowledge remained the formal exam. However, many were initially resistant to the new ways of training, with the introduction perhaps not helped by mandatory minimum numbers of workplace-based assessments (WBAs) in each training year, which very quickly became de facto maximums and submissions of just short of that number were often seen at their Annual Review of Competency Progression (ARCP). Many would see the WBA as a summative, rather than formative, assessment and only ask to be assessed on their best cases, fearing criticism. Criticism was sometimes not constructive, and then at best uninterested and at worst, ‘robust’. Prepopulated assessments sent via The Intercollegiate Surgical Curriculum Programme (ISCP) to be validated by trainers lost the opportunity for feedback, unless it was, as sometimes, a record of the discussion that had taken place after the training event. WBAs were criticised as being ‘touchy feely’ or ‘box ticking exercises’.

When performed well, with enough time and constructive feedback, WBAs do provide, at the very least, a framework for giving feedback on each of these small tasks. However, even when done well, WBAs only assess individual tasks; that operation, done on that patient on that day, and does not mean that, even if done very well on three occasions (say a PBA level 4), a surgeon performs to the same level in different circumstances. Also, performing well in one task does not mean that someone can be a surgeon, a job that requires the subtle integration of a host of professional skills and behaviours as well as a consistently high level of performance in clinical and technical skills. To develop and assess this subtle blend of skills through WBA requires almost infinite sampling of tasks described in the syllabus and therefore constant assessment.

What we currently do is repeat WBAs and place one on top of the other to build up to being a competent new consultant. However, as we go along we find it difficult to check how the building is progressing. Most of the time everything goes according to plan, but sometimes we end up with a ‘wonky house’. It looks a bit like a house in that all the parts are there, but they're not put together well, and it isn't safe and will almost certainly collapse at some point. A series of WBAs, badly done, but ticking the boxes, leaves us with someone at the end of training who looks like a consultant, but is neither ready nor safe on proper inspection.

For these reasons, training and the assessment of training in the workplace has room for improvement.

Rather than build up from the bottom, we can start from the other end and say that someone is ready to be a consultant when they are thought to be ready by their trainers. Being ready involves demonstration of the ability to integrate of all the subtle skills and attitudes with a solid knowledge base for the whole scope of practice of a consultant surgeon. Training is based on outcomes; can you do the job rather than can you do the separate, selected small parts of the job?

The GMC described the generic skills required for any doctor, be they respiratory physician, pathologist or cardiothoracic surgeon, in its Generic Professional Capabilities framework document.2 Also in 2017, it published new standards for postgraduate medical curricula in Excellence by Design3 to help postgraduate medical training programmes re-focus trainee assessment away from an exhaustive list of individual competencies towards fewer broad capabilities required to practice safely as the Day-1 consultant.

As a result, surgical training will become outcomes-based and the end of training will be reached when supervisors agree that a trainee is performing at the level of a Day-1 consultant.

What is a Day-1 consultant in general surgery?

The process for approval of a new curriculum involves two main stages. Approval of the outline of the curriculum by the Curriculum Oversight Group (COG, with input from of representatives of the Statutory Education Bodies, Department of Health, GMC, Shape of Training Steering Group and employers), and then approval of the detail of the curriculum by the Curriculum Advisory Group (CAG). In development of all curricula, there has been widespread consultation with all stakeholders, including trainees, trainers, Schools of Surgery, Specialty Associations, employers, patient and lay representatives, Deans and others.

The development of the outline of all medical curricula were required to satisfy requirements of the Shape of Training Steering Group, laid out in its 2017 report,4 which were that curricula:

-

1.

Take account of and describe how the proposal will better support the needs of patients and service providers.

-

2.

Ensure that the proposed curriculum to CCT equips doctors with the generic skills to participate in the acute unselected take and to provide continuity of care thereafter.

-

3.

Where appropriate, describe how the proposal would better support the delivery of care in the community.

-

4.

Describe how the proposal will support a more flexible∗ approach to training.

-

5.

Describe the role that credentialing will play in delivering the specialist and sub-specialist components of the curriculum.

∗Flexibility refers to how skills can be transferred between training pathways if a trainee chose to change career path, as well as flexibility within a training pathway.

After much consultation, the COG approved purpose statement for General Surgery5 states that the purpose of the General Surgical Curriculum is to:

… produce consultant general surgeons to manage patients presenting with the full range of emergency General Surgery conditions and elective conditions in the generality of General Surgery. Trainees will also be expected to develop a special interest within General Surgery in keeping with service requirements. They will be entrusted to undertake the role of the General Surgery registrar during training and will be qualified to apply for consultant posts in General Surgery in the United Kingdom or Republic of Ireland after successful completion of training.

To reiterate, to fit the needs of patients and service providers, a Day-1 consultant is a general surgeon who can manage the unselected take and is not a consultant in a special interest area, such as coloproctology or endocrine surgery. Further development of scope of practice may or may not happen after appointment to a consultant post, and will depend on local service needs; some will retain a more general scope of practice and some will become much more focussed on a particular small area even within a special interest of general surgery. The curriculum output leaves flexibility for evolution while producing someone fit for purpose.

What's the training pathway to become a Day-1 general surgeon with a special interest?

Trainees will finish training when they have reached the level expected of a Day-1 consultant in General Surgery. Training will now be truly capability based, although there will be indicative times for the length of training in which the great majority of trainees will be expected to complete training. Trainees will be able to progress faster through training if they demonstrate the necessary capabilities.

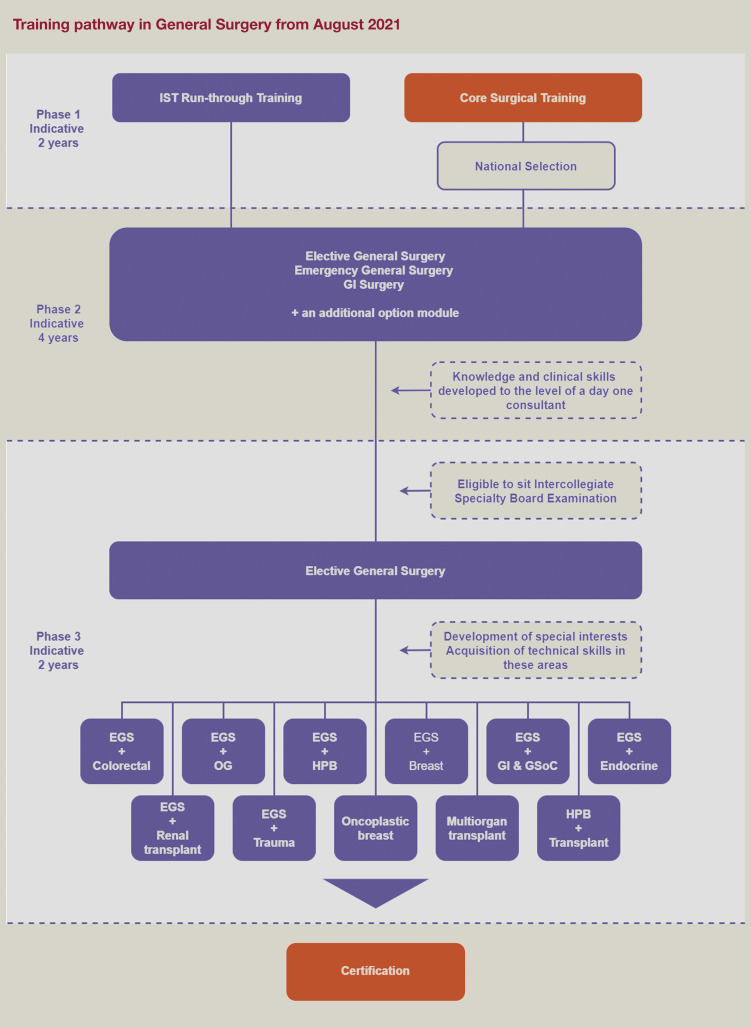

Surgical training will be arranged into three phases, each having a critical progression point at its end, where evidence of acquisition of capability to a level described in the curriculum is necessary for progression to the next phase or for certification (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Phase 1

The outcome is to gain the competencies equivalent to those described in the core surgical training curriculum. The indicative time for phase 1 is 2 years.

Phase 2

The outcome is to gain experience in the breadth of general surgery, including the unselected emergency take. There will be opportunities for early exposure special interests (shown in phase 3 with the availability of an option module in rural and remote surgery to help trainees decide what special interest to pursue later in training. The knowledge, clinical and professional skills will be developed to that required of a Day-1 consultant by the end of phase 2, which will then make trainees then eligible to apply to take the Intercollegiate Specialty Exam in their chosen specialty. Technical skills will be developed throughout the breadth of the specialty, including in emergency cases, but it is recognized that technical skills may develop more slowly than knowledge, clinical and professional skills. They do not, therefore, need to be at the level of a Day-1 consultant by the end of phase 2. The indicative time for phase 2 is 4 years.

Phase 3

The outcome of phase 3 is to have gained all the capabilities necessary for safe practice as a Day-1 consultant in the specialty. As knowledge, clinical and professional skills have been developed to the level of a Day-1 consultant as part of the outcome of phase 2, then phase 3 allows development of technical skills to the level of a Day-1 consultant in the generality of the specialty, emergency care and in any special interest described. Once these capabilities have been achieved an ARCP 6 may be awarded and trainees can apply for CCT.

The central role of emergency general surgery (EGS) in the scope of practice of a general surgeon is emphasized in the special interest area (EGS + special interest). The exceptions to this are those who choose to develop oncoplastic breast surgery as their special interest, reflecting that EGS has not been within the scope of practice of the vast majority oncoplastic breast surgeons in the UK for many years, and those special interests containing multiorgan transplantation or HPB surgery with transplantation, where consultants will take part in their own emergency rotas covering transplantation from Day-1.

The introduction of a gastrointestinal module incorporating general surgery of childhood is in direct response to identified needs of the service in some parts of the UK. The current lack of provision of general surgery of childhood in similar parts of the UK is addressed by enabling trainees to develop these skills in the same module.

A special interest in trauma surgery has been developed, and contains all the syllabus items contained in the resuscitative surgeon portion of the Major Trauma Training Interface Group (TIG) syllabus, and so prepare trainees for a consultant role as a trauma surgeon in a major trauma centre within training.

The existing special interest of upper gastrointestinal surgery has been split into separate special interests, recognizing the increased separation of oesophagogastric and hepatopancreaticobiliary surgery in modern day clinical practice.

Until now, general surgeons wishing to develop a special interest in oncoplastic breast surgery have had to acquire the oncoplastic skills by being appointed to a TIG in oncoplastic breast surgery. As the TIG, running since the early 2000s, has been so successful, the TIG syllabus can now be incorporated into phase 3 training, meaning that breast surgeons will now reach CCT with oncoplastic skills and, over time, patients will be able to access these in any hospital providing breast surgery services. A module allowing the development of EGS alongside a mainly non-reconstructive range of breast skills is described mainly for trainees in the Republic of Ireland, where, in contrast to the UK, the majority of breast surgeons take part in the unselected take.

Thus, a Day-1 consultant with certification in general surgery will have the knowledge and clinical skills to independently manage an unselected emergency general surgical take and all elective general surgery conditions with an elective special interest, giving maximal flexibility to employers while ensuring a safe, high-quality service for patients.

All doctors need to have the competence to be doctors first and specialist later

Generic professional capabilities

The GPC framework2 was developed by the GMC and the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges with the aim of providing a consistent approach to ensuring that all doctors demonstrate an approprizte and mature professional identity. The framework prioritises themes, such as patient safety, quality improvement, safeguarding vulnerable groups, health promotion, leadership, teamworking, and other fundamental aspects of professional behaviour and practice.

The GPCs describe the interdependent essential capabilities that underpin professional medical practice in the UK. They also serve as educational outcomes, carrying equal weight to the capabilities in practice and, are therefore, an integral part of the surgical curriculum, supporting every phase of training.

Satisfactory achievement of the GPCs by trainees will demonstrate that they have the necessary generic professional capabilities needed to provide safe, effective and high-quality medical care in the UK and the Republic of Ireland.

The nine domains of the GPC framework are:

-

1.

Professional knowledge

-

2.

Professional skills

-

3.

Professional values and behaviours

-

4.

Health promotion and illness prevention

-

5.

Leadership and teamworking

-

6.

Patient safety and quality improvement

-

7.

Safeguarding vulnerable groups

-

8.

Education and training

-

9.

Research and scholarship.

What are the high-level outcomes for general surgical training?

The curriculum is outcomes based, specifying the high-level capabilities that must be demonstrated to complete training. The high-level outcomes of the curriculum are expressed as Capabilities in Practice (CiPs). A Capability in Practice covers everything a Day-1 consultant needs to perform that part of the job and integrates knowledge, clinical, professional and technical skills into a functioning whole. Someone can be thought safe to complete training when they have reached the level expected of a Day-1 consultant in each of the CiPs, as well as satisfying the other certification requirements described in the curriculum.

Capabilities in practice are:

-

1.

Managing an out patient clinic

-

2.

Managing in-patients and ward rounds

-

3.

Emergency care

-

4.

Managing an operating list

-

5.

Multi-disciplinary teamworking.

General surgery is not just about operating, and training has to focus on all aspects of the job of a consultant surgeon, represented in the CiPs. Training opportunities in a placement should be balanced to reflect the need for development in each of the CiPs through training.

How are the CiPs going to be assessed?

Capabilities in Practice cannot be assessed using existing WBAs and a new assessment, the Multiple Consultant Report (MCR) has been developed.

The Multiple Consultant Report

The MCR will take place at the mid-point and end-point of each placement and feed into the Learning Agreement. The MCR will involve the professional judgement of the Clinical Supervisors who work with trainees on a day-to-day basis, assessing them against the high-level outcomes of the curriculum; the GPCs and CiPs.

When someone is at the start of training they will need to be supervised more than someone near the end of training in each of the CiPs, until no supervision is needed when the level of a Day-1 consultant has been reached and training can end. To classify how much supervision is required in each CiP at a particular time, supervision levels will be introduced. To allocate a supervision level ask ‘how much supervision is needed in this area of work?’ Supervision level I describes someone who can only observe the task and supervision level IV indicates that someone is displaying competencies at the level of a Day-1 consultant (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Supervision levels describing the level of capability in practice

| Supervision Level I | Able to observe only: no execution |

| Supervision Level IIa | Able and trusted to act with direct supervision: The supervisor needs to be physically present throughout the activity to provide direct supervision |

| Supervision Level IIb | Able and trusted to act with direct supervision: The supervisor needs to guide all aspects of the activity. This guidance may partly be given from another setting but the supervisor will need to be physically present for part of the activity |

| Supervision Level III | Able and trusted to act with indirect supervision: The supervisor does not need to guide all aspects of the activity. For those aspects which do need guidance, this may be given from another setting. The supervisor may be required to be physically present on occasions. |

| Supervision Level IV | Perform at the level of a Day-1 consultant |

| Supervision Level V | Performs beyond the level expected of a Day-1 consultant |

Supervision levels will be recommended by clinical supervisors who work with the trainee in each of the CiP areas on a day-to-day basis via an assessment called the Multiple Consultant Report (MCR).

The place of the MCR in the assessment system

The assessment system is made up of several different types of assessment needed to meet the requirements of the curriculum; workplace-based assessments, examinations at key stages and the ARCP. These together generate the evidence required for global judgements to be made about satisfactory trainee performance, progression in, and at completion of, training. The primary assessment in the workplace is the MCR, which, together with the other assessments, becomes the key component of the AES report, feeding into the information presented to the ARCP. Assessment takes place throughout the training programme to allow trainees to continually gather evidence of learning and to provide formative feedback to the trainee to aid progression.

The main workplace-based assessment in the new outcomes-based curriculum will be theMCR. Clinical supervisors will meet at the midpoint and just before the end of a placement to discuss the supervision level reached by a trainee in each of the CiPs and also whether they are developing GPCs to an appropriate level for the phase of training. If a trainee has not reached supervision level IV or V in a CiP, then the MCR will require trainers to identify areas most in need if development in the next 3–6 months of training in order to develop towards a Day-1 consultant. Trainees will complete the same form as a self-assessment and identify their own supervision level and areas for development. If performance is beyond that expected, then this can be captured too.

A trainer will meet with the trainee to discuss the MCR and the self-assessment and agree how to best to develop in the areas identified. This may involve changing the emphasis of the placement slightly if one CiP seems to falling behind the rate of development in others. The midpoint MCR will provide formative feedback and the end of placement MCR also will provide formative feedback, but will, in addition, provide a summative assessment for consideration by the ARCP panel.

The MCR will also be integrated into the learning agreement. The MCR from the previous placement and its recommendations of areas for development will be available, as well as the self-assessment to facilitate the setting of goals for the new placement. In this way it will be easier to ‘hit the ground running’ in a new placement. Progress towards the objectives set will be reviewed at the midpoint learning agreement meeting along with the formative midpoint MCR and modifications made accordingly. The final review meeting of the learning agreement meeting will consider the end of placement MCR. The AES report will take into consideration progress against objectives as well as the MCR and other portfolio evidence for consideration by the ARCP panel at the end of the training year.

Trainee self-assessment

Trainees will have a corresponding self-assessment to aid their reflection as well as discussion at their feedback sessions. This will allow trainees to identify areas for development in the placement for themselves, perhaps not identified by trainers, and also for supervisors to recognize over, or more often, under confidence in trainees and discuss underlying reasons for the latter and offer support and reassurance. The self-assessment will be a very powerful tool if used openly by trainees and discussed sensitively by supervisors.

The role of WBAs will be less in the new curriculum

In an outcomes-based curriculum that develops integrated capability in the daily tasks of the job of a consultant surgeon, the current set of WBAs are less suited, because they are too granular in their scope. Because of this, and also so as not to add another layer of assessment to training, there will be no requirement to complete a certain number of WBAs per training year. WBAs will remain to provide additional evidence of competence by the completion of training in key areas of the syllabus; the critical conditions and index procedures. They can also be used by trainees to formalize and structure feedback on particular clinical interactions or procedures if they wish. In addition, they can be used to assess progress towards achievement of targeted training.

When will trainees move to the new curriculum?

The vast majority of trainees will begin to follow the new curriculum from 4 August 2021. There are some exceptions to this, including those in less than full time training and those in the final year of training, and full details can be found on the ISCP website.6

How will ISCP change?

ISCP will incorporate all of the above changes and start to have a new, cleaner and easier to navigate look. You can find out more about the changes by clicking on the Surgical Curriculum 2021 box on the ISCP homepage (Figure 2 ) and follow the links to the new General Surgery purpose statement and syllabus and how to try the MCR for yourself (you have to be logged in to try the MCR). You can also see how the new learning agreement will incorporate the MCR and self assessment and make it easier to use feedback to identify areas for development in the next few months of training after August 2021.

Figure 2.

Can I use the MCR now?

The MCR cannot be used as part of formal assessment until the new curriculum is formally introduced in August 2021. However, the MCR can be used to generate high-quality and specific feedback and structured self assessment. Both can be used in discussions around learning agreements to identify training needs in the next few months, and may be invaluable to flag what training is most needed in the COVID-19 recovery phase.

Summary

The General Surgical Curriculum was approved by the GMC earlier this year. Implementation has been postponed until August 2021 because of disruption caused by COVID-19. Changes in the General Surgical Curriculum will produce safe general surgeons with a special interest in areas required by patients and the service. Assessment will move away from granular ‘tick box’ assessments to holistic assessment of performance in the major areas of the working week of a consultant surgeon, reflecting the subtle integration of knowledge with professional, clinical and technical skills required to be a Day-1 consultant. Assessment through the MCR by trainers and self assessment by trainees generate detailed bespoke feedback for all trainees, allowing focus on areas for development most needed in the following months of training. Feedback at the heart of the learning agreement will allow more effective training. Training will no longer be of a fixed time and trainees may finish training when they have reached the level of a Day-1 consultant in General Surgery.

References

- 1.Modernising Medical Careers, Final Report https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200708/cmselect/cmhealth/25/25i.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Generic Professional Capabilities Framework https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/generic-professional-capabilities-framework--0817_pdf-70417127.pdf.

- 3.Excellence by Design https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/Excellence_by_design___standards_for_postgraduate_curricula_0517.pdf_70436125.pdf.

- 4.Report from the UK Shape of Training Steering Group (UKSTSG) https://www.fph.org.uk/media/2788/shape_of_training_final_sct0417353814.pdf.

- 5.General Surgery Curriculum purpose statement https://www.iscp.ac.uk/media/1032/general-surgery-purpose-statement-2020_3.pdf.

- 6.Transition to New Curricula https://www.iscp.ac.uk/iscp/content/articles/curriculum-update01/#heading_3.