Abstract

Objective

Since the outbreak of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in December of 2019 in China, estimating the pandemic’s case fatality rate (CFR) has been the focus and interest of many stakeholders. In this manuscript, we prove that the method of using the cumulative CFR is static and does not reflect the trend according to the daily change per unit of time.

Methods

A proportion meta-analysis was carried out on the CFR in every country reporting COVID-19 cases. Based on these results, we performed a meta-analysis for a global COVID-19 CFR. Each analysis was performed using two different calculations of CFR: according to the calendar date and according to the days since the outbreak of the first confirmed case. We thus explored an innovative and original calculation of CFR, concurrently based on the date of the first confirmed case as well as on a daily basis.

Results

For the first time, we showed that using meta-analyses according to the calendar date and days since the outbreak of the first confirmed case, were different.

Conclusion

We propose that a CFR according to days since the outbreak of the first confirmed case might be a better predictor of the current CFR of COVID-19 and its kinetics.

Keywords: COVID-19, Case fatality rate, Proportion meta-analysis, Calendar date, Days since the first confirmed case

Introduction

Since the outbreak of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in December of 2019 in China, COVID-19 has spread worldwide (WHO, 2020; Zhu et al., 2020). As of August 19, 2020, 21,938,207 confirmed cases with 775,582 deaths were reported across the 216 affected countries, territories, or areas (WHO, 2020). Among other clinical and epidemiologic features of the virus, predicting the estimates of mortality of this pandemic is vital and indispensable.

The estimate of the case fatality rate (CFR) is defined as the number of deaths from COVID-19 divided by the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases. CFR was developed to understand the mortality and epidemiological features of emerging infectious diseases (Porta, 2008, Battegay et al., 2020), such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-coronavirus (SARS, CFR 9.6% on a global scale) (Donnelly et al., 2003) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome-coronavirus (MERS, CFR 34.5%) (Fisman et al., 2014). To date, there have been many attempts to estimate the underlying “true CFR” of COVID-19 (Baud et al., 2020, Wilson et al., 2020, Rajgor et al., 2020, Kim and Goel, 2020, Spychalski et al., 2020, Lipsitch, 2020). However, these published CFR are not without limitations. These estimates need to be treated with extreme caution because each region of the world is experiencing a different stage of the pandemic. Also, CFR is contingent on many other factors, including the extensiveness, detection and testing efficiency, local health and pandemic response policies, and the condition and inclusiveness of the already existing health systems. Failure to consider these former factors and simply dividing the cumulative deaths from COVID-19 by cumulative confirmed cases based on the latest global statistics available will inevitably distort the CFR in each stage of COVID-19 in an unknown direction, let alone fail to reveal the true dynamics of the CFR of this disease. In addition, previously published papers (Yang et al., 2020, Öztoprak, 2020) suggested models using CFR should be based on the cumulative confirmed cases and deaths with a simple linear regression analysis. However, this method of using the cumulative number is static and does not reflect the trend according to the daily change per unit of time. Additionally, it prevents an exact estimation of the CFR because the number of the confirmed cases and the onset time of the first case vary by country, and even within regions of the same country.

Therefore, to get as close as possible to a real estimate, we calculated the CFR of each country, concurrently based on the date of the first confirmed case as well as on a daily basis.

Materials & methods

Proportion meta-analyses were performed to obtain the average CFR for each day, commencing from the date of the first confirmed case to the present, stratified by each country. Therefore, we present unique CFR dynamics obtained by correcting and theoretically circumventing the bias created by the fact that each country is facing different stages of the pandemic. This approach to the CFR provides a new insight that lays the foundation for a proper analysis of CFR. One caveat that we acknowledge is that many potential positive cases that were not tested might present possible confounding variables, skewing our results in a specific direction. At this point, it is impossible to account for the totality of the COVID-19 cases (tested and not tested), and this calculation is out of the scope of this study.

Global data of COVID-19 confirmed cases and deaths from COVID-19 were collected from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC, https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/geographical-distribution-2019-ncov-cases), which showed each country’s data from December 31, 2019, to August 12, 2020. The CFR was defined as follows:

Important to note, our analysis of CFR included only cases confirmed by molecular or serological testing. The data had blanks since the reports from each country were not continuous on a daily basis, especially during the early stages of the epidemic, secondary to under-testing and under-reporting of cases. After multiple rounds of discussions, for calculation simplicity, the blanks were filled and processed as the number of cases in the most recent report before the blank, rather than splitting the number of cases equally among the missing days. We stratified the confirmed cases and deaths from COVID-19 for each country, according to the number of days since this country reported its first confirmed case of COVID-19.

A proportion meta-analysis was then carried out on CFR in every country reporting COVID-19 cases. Based on the results, we performed a meta-analysis for a global COVID-19 CFR. Each analysis was performed on two different calculations of CFR: according to the cases' calendar date and according to days since the outbreak of the first confirmed case. Every analysis was based on reports until August 12, 2020.

For a meta-analysis of the CFR of COVID-19, MedCalc version 19.2.1 software (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium, trial version) was used to analyze the summary effects with a 95% confidence interval (CI) and between-study heterogeneity. We performed a proportion-meta-analysis to estimate the summary effects. The summary effects obtained by the proportion meta-analysis of the CFR under the fixed- and random-effect model for each data over time were presented as figures, and the 95% CI are summarized in the Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. As we mentioned, we used MedCalc for the proportion of meta-analysis of the COVID-19 CFR. MedCalc uses a Freeman-Tukey transformation to calculate weighted summary proportions and the default random-effects model is DerSimonian and Laird. The procedure suggested by DerSimonian and Laird is the most commonly used method for fitting the random-effects model for meta-analysis. This meta‐analytical method was used to pool CFR proportions. The calculated fixed effect and random effects meta-analysis methods were used to combine single proportions. Prior to that, proportions were transformed using the Freeman‐Tukey double arcsine transformations. To determine the extent of variation between the studies, we did heterogeneity tests with Higgins’ I2 statistic (Higgins, 2003). An I2 value below 50% represented low or moderate heterogeneity, while I2 >50% represented high heterogeneity (Higgins, 2003). For graphing the patterns of CFR in all countries, RStudio version 1.3.1073 was used. We used a weighted average to ensure the precision of the overall estimates, i.e., having the smallest possible variance and standard variation. Our study used the inverse variance weights of our data to give less weight to the noisier and less relevant data. The weight for each size estimate was proportional to the inverse of its variance, ensuring that larger countries with a high number of infections and mortality will have more weight compared to those countries with few cases and noisy data.

Results

The new dynamics of CFR revealed after the meta-analyses

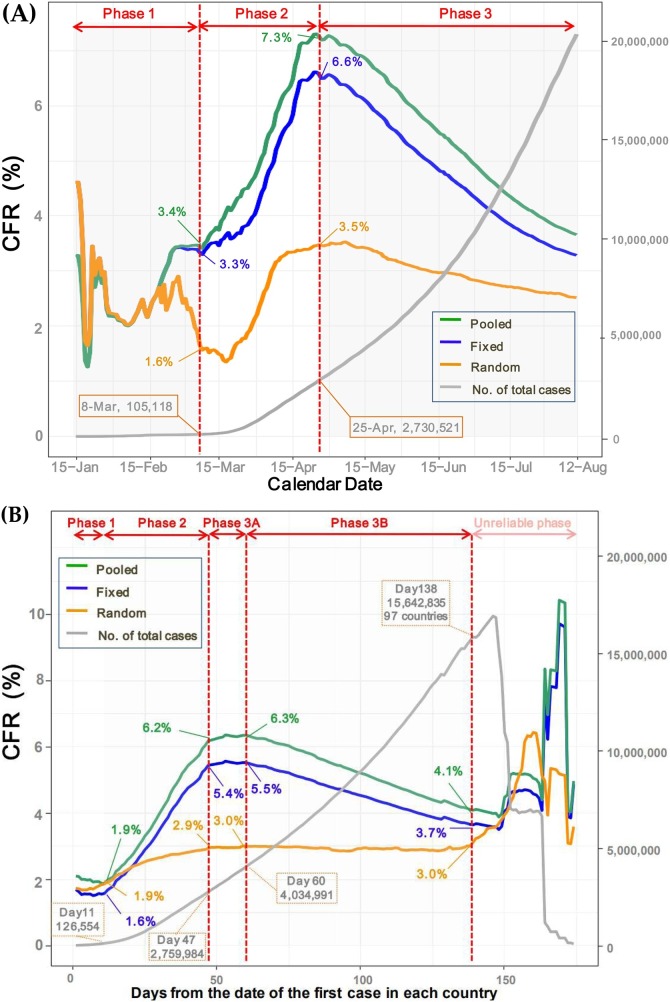

Figure 1A and B present the following data over time: the fixed- and the random-model results of the meta-analysis, the pooled estimate, and the number of total cases included in each analysis.

Figure 1.

Timeline of CFR worldwide among countries with COVID-19 reports until August 12, 2020: (A) According to date and (B) According to days since the first confirmed case.

COVID-19: Coronavirus 2019, CFR: case fatality rate, Fixed: fixed-effect model, Random: random-effect model, Pooled: calculated CFR based on incidence and mortality data, N: number.

By comparing the figures that show the time trend of CFR stratified by the two methods, it was visually observed that the CFRs calculated by each sorting method had different trends over time: Figure 1A (CFR stratified by calendar date) vs. Figure 1B (CFR stratified by days since the first confirmed case). In both figures, results from the random- and the fixed-effect model were almost identical; however, after they diverge, the fixed-effect model was similar to the pooled estimates while the random-effect model estimates were smaller. One possible explanation for the fact that random CFR estimates were lower than the fixed estimate is that less weight is given to countries with a small number of confirmed cases than countries with a high number of cases. For example, the United States has 5,141,207 confirmed cases and 164,537 deaths in contrast to South Korea, with 14,714 confirmed cases and 305 deaths.

Similar to Figure 1A, in Figure 1B, the initial phase (phase 1), phase 2 in which pooled and fixed estimates increase rapidly, and the random estimates increase slowly; phase 3A where pooled and fixed estimates remain high, and phase 3B in which the pooled and fixed estimates gradually decrease. There is also “the unreliable phase,” where the countries that have been enrolled later are dropping out as the day gets longer, making it difficult to interpret. It should be noted that during phases 3A and 3B, the random estimates remains constant, slightly below 3.0%. When we analyzed this data in May 2020, we could not see trends after phase 3A. From the point of view at that time, pooled and fixed estimates tended to be quite similar, while random estimates were taken as far apart. As the data until August 12, 2020, was updated, a long phase 3B appeared, and the pooled and fixed estimates at the end of phase 3B became more similar to the random estimates, which had been constant for an extended period of time, narrowing the gap considerably. In this analysis, I2 is more than 70% over the entire period from day 1 to day 174, suggesting that the random estimate is more reliable.

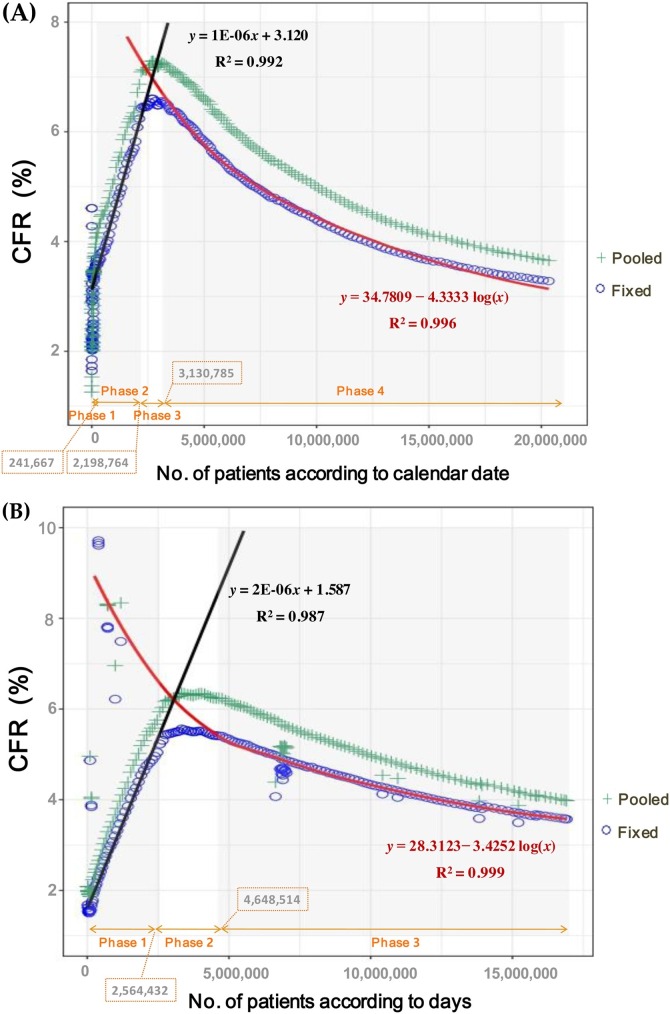

Figure 2 presents the trend of patients with COVID-19 according to date and according to days. We obtained the time trend of CFR by calculating pooled estimates, fixed- and random- effect estimates from meta-analyses by the calendar date and by days since the first confirmed case.

Figure 2.

The trend of patients with COVID-19: (A) According to date and (B) According to days.

COVID-19: Coronavirus 2019, CFR: case fatality rate, No.: number, Fixed: fixed-effect model, Pooled: calculated CFR based on incidence and mortality data.

We analyzed the CFR trend by placing the number of confirmed cases on the x-axis in Figure 2A. There are two contrasting phases, one of which is the earlier phase (phase 2) in which the pooled and fixed estimates rapidly increase until the number of cases reaches 2,198,764. After that, when the number of cases exceeds 3,130,785, the later phase (phase 4) which the pooled and fixed estimates gradually decrease in the form of a logarithmic function appears. Besides, the initial phase (phase 1) a lack of regularity and the short plateau phase (phase 3) are also observed. A similar trend appears in the analysis according to the number of days from the date of the first confirmed case in each country (Figure 2B); however, in this figure, the length of the plateau phase between the two contrasting phases 2 and 4 is longer than that of Figure 2A. Using the regression equation for phase 4 obtained in Figure 2B, even if the number of confirmed cases increases significantly up to 30 million, the fixed estimate CFR is expected to remain at 2.7%.

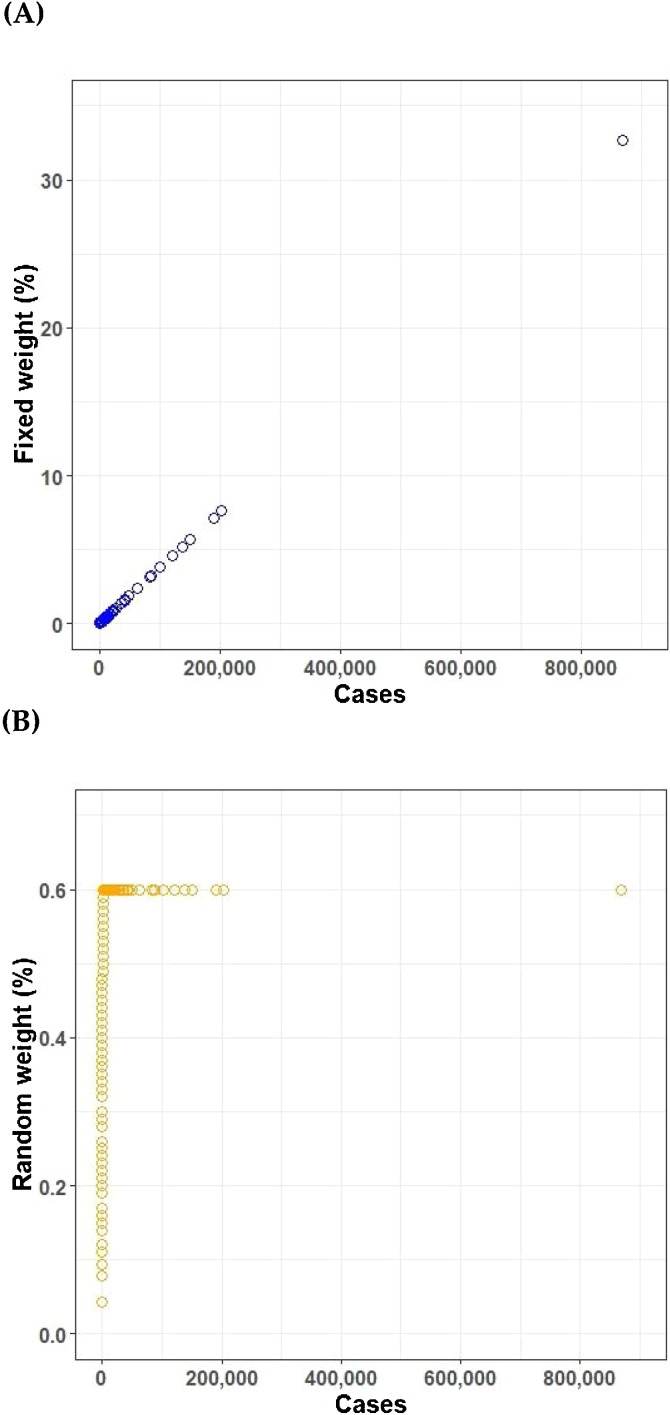

We set the cut off to 100 confirmed COVID-19 cases to reasonably reduce the noise in our statistical analyses. We focused on the distribution of fixed and random weights on analyzing the data from April 24, 2020, where the difference between fixed and random effects was the largest. In the fixed estimate, as the number of confirmed cases increases, a weight that increases proportionally is given (Figure 3 A). On the other hand, in random meta-analyses, the weight was 0.6% for all countries or territories with greater than or equal to 1,981 confirmed COVID-19 cases (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Differences in weight between (A) Fixed and (B) Random meta-analyses,calculated to the number of patients at one point as an example 205 countries, April 24, 2020.

Random weight: Weight in random meta-analyses, Fixed weight: Weight in fixed meta-analyses.

Namely, a higher weight is given to countries with a large number of confirmed cases in the random estimate. On the other hand, lower weight is given to countries with a low number of cases in the fixed estimate (Figure 3A and B). Extrapolating from our previous results, the cutoff date for the CFR chosen was March 20, 2020. This date guarantees a relative homogeneity of the data analyzed. We discovered that most countries would have entered the observed “second phase” of the pandemic, that is, after March 20, 2020, the fixed and random meta-analyses are divergent for all countries, and their weight-adjustment would guarantee consistency of the observed outcomes.

We identified four distinct phases based on our results. Figure 1A, phase 1 contains data from January 15 to March 15, 2020, phase 2 included data from March 16 to April 25, and phase 3 was from April 26 to August 12. In phase 1, all CFRs ranged between 1% and 3.4%. However, from March 16 to April 25 (phase 2), both fixed and pooled CFRs increased rapidly from 3.3% to 6.6% for fixed-effect CFR and 3.4% to 7.3% for pooled CFR. From April 25, with 2,730,521 confirmed patients to May 16, both fixed and pooled CFRs remained at 6%p and 7%, respectively (phase 3). Note that in phase 3, we observed that the CFR starts to decrease even though the number of confirmed patients per date continues to rise after the total of 2,730,521 was reached. As our results demonstrated, Figure 2A did not show a similar pattern as Figure 1A. In phase 2 of Figure 1A, we observed a rise in the pooled and fixed model; however, the random model does not increase steeply. This trend was not observed in Figure 2A. This further supports our hypothesis that CFR is not a dynamic indicator and should not be analyzed solely using the traditional mathematical equation based primarily on the cumulative number of patients. The trends in Figure 2A are established using the number of confirmed cases according to the calendar date. Therefore, its trend is a better representation of the established healthcare systems, the testing ability, and socioeconomic factors of the respective countries.

Figure 2B shows a similar trend with the characteristic phases 1 to 3, parallel to those in Figure 1. It showed an exploding increase from Day 1 to Day 45 when the number of confirmed patients per day reached 2,564,432 (phase 1). As the number of confirmed patients increased to 4,648,514 on Day 66, the fixed CFR remained at 5.4%, and the pooled CFR remained at 6.2%, despite the fact that the number of confirmed patients increased rapidly.

Comparing Figure 1A and B, we found that both pooled and fixed CFRs increased approximately 1% after adjusting the CFR standard to the days since the first confirmed case (7.09% to 8.20%, 6.40% to 7.40%, respectively). Therefore, the CFR in the plateau phase was approximately 1% higher in the meta-analyses by days since the first confirmed patient compared to the meta-analyses by date. This might be explained by the “noise” in the data from the early days of each country's epidemic. Analogous comparison of Figure 2A and B revealed a similar 1% approximate increase in phase 3, the plateau phase, between CFR by days since the first confirmed patient compared to the meta-analyses by date.

An additional phase emerged in Figure 1B since countries with newly emerging COVID-19 moved to the front of the onset period as they were sorted by days (Supplementary Figure 2, see Appendix). Similarly, the I2 value earlier reached above 50% representing high heterogeneity at Day 15 and showed a plateau pattern since Day 50 according to number of days (Supplementary Figure 1B) than the calendar date. It reached above 50% on February 25, 2020 and a marked plateau since April 12, 2020 according to the calendar date (Supplementary Figure 1A). The heterogeneity that we observed is actually directly related to the stage of the pandemic each country experienced at the time we analyzed the data. That is, at the start of the pandemic, almost all confirmed cases and associated mortality were originating and reported exclusively from China. This is why the heterogeneity was at 0% as expected. As the pandemic unfolded and many more countries started experiencing it, confirmed cases and mortality began to be reported from countries around the globe, in addition to those coming from China. This was manifested by an expected increase in the study’s heterogeneity.

Figure 1B identifies the time period of day 15 when the fixed- and random- model estimates split, and the estimates of fixed-model proceeds in a similar direction to the pooled model estimates.

Correlations between the number of confirmed patients and CFR

Based on Figure 1, we also investigated the relationship between CFR and the number of confirmed COVID-19 patients (Figure 2). Figure 2A was devised using the number of patients according to the calendar date rather than the cumulative number of patients. This figure revealed that CFRs linearly correlated with the number of confirmed cases; the more the number of confirmed cases, the higher the CFR. On the other hand, when the number of patients was adjusted by days since the first confirmed case, as shown in Figure 2B, the CFR increases, as shown in Figure 1B, until the number of confirmed patients per day reaches 1.0 million. Following this phase, the CFR then rapidly increases between 1.0 million and 1.5 million cases. After 2.0 million cases, a plateau pattern continues.

In Figure 2B, the blurry dots represent CFRs in the “unreliable phase.” In this phase, CFR decreases when the number of confirmed patients falls below 2 million. The unreliable phase could potentially represent a new phase, a decreasing phase. The model according to calendar date (Figure 2A), may have underestimated the CFR; this might be because of countries being in different stages and thus phases of the disease.

Discussion

The estimation of the COVID-19 pandemic’s CFR has been the focus and interest of many stakeholders as it plays a key role in understanding this pandemic and guides appropriate responses and efficient mitigation strategies. We propose that CFR is not a fixed, static rate. It is rather dynamic, continually fluctuating with time, location, and population, as confirmed in Figure 1A and B. In this context, it is important to view CFR as a function of time, rather than presenting CFR as a single and absolute value. Stratifying CFR by days since the first confirmed case is a novel and innovative attempt to uncover CFR dynamics as the epidemic unfolds. We believe that a CFR stratified only by calendar date does not reflect each country's true epidemic situation.

Our analysis revealed a CFR trend consisting of four distinctive phases. Based on our results, we carefully propose that the slope of the epidemic model will proceed to the next four stages as follows: phase 1 or initial phase, phase 2 or rapid increase phase, phase 3 or plateau phase, and phase 4 or decreasing phase. Based on this statistical trend, it is estimated that the pandemic's global situation will slow down from the time all countries reach phase 3, and it can be improved when the situation has reached the end of the phase. However, as mentioned above and analyzing the data of 100 days so far, the world may remain in phase 3 as of May 2020 for an undetermined amount of time, and the CFR may not have yet reached phase 4. It may take a considerable amount of time to enter this final phase.

The method of calculating the CFR needs to be treated cautiously, and its limitations acknowledged. The numerator and the denominator of the CFR should be composed of patients infected at the same time as those who died, to accurately represent the CFR. To overcome this restraint, Baud et al. (2020) and Wilson et al. (2020) proposed a time delay-adjusted CFR to correct the delay between confirmation and death. They adjusted the CFR's denominator as the number of confirmed cases 13-14 days before the measured date to calculate the number of confirmed cases infected concurrently to those who died. Based on these articles, researchers at Oxford University used their global COVID-19 CFR model according to the date since the outbreak in Jan 2020 (The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, 2020). However, Oxford's calculation is also flawed since 13 to 14 days before the date of test confirmation is not necessarily the date when a subject is infected (Spychalski et al., 2020). Moreover, some cases show test positivity even after recovery. Additionally, the stretching and overwhelming of healthcare systems creates a delay between testing and receiving the results, thus confirming the case. As this adjusted time-delay CFR leads the estimate to an unknown bias (Spychalski et al., 2020, Lipsitch, 2020), we used the conventional method to calculate CFR.

The numerator of the CFR is the number of deaths from COVID-19. We should be aware that this number is imperfect and may include deaths not directly caused by COVID-19, such as fatal comorbid diseases. This may lead to an overestimation of the number relative to its true value.

In the present study, we observed unusually exaggerated estimates from our meta-analyses in the early phase (Phase 1) of the epidemic, both in a CFR based on the calendar date and based on days since the first confirmed case. This is thought to be a statistical bias, as many groups and countries with small numbers were included. The studies included in the early phase of the epidemic are mostly a bundle of data in which deaths sporadically occurred in small group sizes. Such data distribution may have severely exaggerated the meta-analyses results. Therefore, we believe that we should aim for a more standardized and homogenous analysis of the numbers. One method would be to observe the results from the time when the number of confirmed cases in each country has reached a certain distinct level. As a measure of when the results of meta-analyses become meaningful (the starting period of Phase 2), we presented the time when the fixed-effect model and random-effect model coincided. In the time-trend graph of every meta-analysis, the initial estimates of the random-model and the fixed-model almost coincide; they diverge at a certain point of time, which is, interestingly, Day 15 from the first case in each country.

There are inevitable errors that arise because actual confirmed cases, or COVID-19 deaths, are not properly reflected due to differences in the medical system capabilities and the response to the pandemic in each country. Moreover, the number of screening tests for COVID-19 differs by the diverse screening criteria of each country. The rapid spread of COVID-19 means that there are cases and deaths not accounted for and, consequently, not recorded in the reported statistics. The screening criteria may have changed and evolved as COVID-19 spreads in a country. For example, South Korea had initially limited the screening tests to people with fever (37.5 °C or above), respiratory symptoms who had contacts with a person returning from China, or confirmed symptomatic cases within the last 14 days (Medicine TKAoI, 2020). But as the disease spread, South Korea widened the screening criteria to anyone who needed to be hospitalized based on a physician's decision due to pneumonia from an unknown source (Medicine TKAoI, 2020).

The capability and efficiency of healthcare systems and the testing ability of COVID-19 are also important. When the overall testing capability for COVID-19 is limited to the most severe cases hospitalized with severe illness, the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases with mild symptoms and easily recoverable cases will be underrepresented, resulting in artificially inflated CFRs. The capability of healthcare systems is central because, in practice, there are many examples where COVID-19 patients are concentrated in one geographical location. Cases of the disease in Italy spread fast, especially in the North, with an overwhelming proportion of individuals in need of intensive care units (University of Tokyo Health Service Center, 2020; Speciale and Kresge, 2020).

Other published studies have performed a meta-analysis of observational COVID-19 studies and reported pooled incidence of mortality. Zhao found a pooled CFR of 3.1% after analyzing 30 studies with 53000 patients (Zhao et al., 2020). Similarly, our CFR meta-analysis calculated from the first confirmed case; we set new standards for observing CFR and suggested the four phases of an epidemic pattern. From these results, the overall estimated CFR in this pandemic is expected to be at 2.9% to 3.0% in random estimates (Figure 1B). Because the pandemic is still in progress, however, future studies and discussions are needed to fulfill the unmet need for consensus regarding the definition of each phase. It would also be interesting to explore the relation between the CFR and the number of tests performed. Specifically, it would be of great added value to explore if a higher number of tests and availability is associated with a lower CFR. When the CFR is estimated by day since the first confirmed case, the estimates could be more representative of “the true kinetics” of COVID-19 CFR by time in a country. The stages of the epidemic should be classified by setting appropriate standards based on reliable global data, and a discussion of setting these standards is necessary. It is noteworthy to say that since COVID-19 is an ongoing and unfolding pandemic, we caution that the CFR time trend according to calendar days since the first confirmed case cannot be used to predict future CFRs. The CFR analysis based on the calendar date is subject to bias. The data that the analysis was based on are dynamic and updated in real-time; however, this information is subject to many variables. The phases that we observed when the CFR according to calendar date is analyzed, are contingent on the reporting of deaths in different and non-homogeneous ways. It also depends on the testing abilities and capabilities of each country. This is why, as we have discussed before, the model that analyzed the CFR according to the day of the first reported infection is a better and a more representative model.

Our analysis was based mainly on a single source, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Although this is a well-respected reference commonly used by the scientific community for its accuracy, data transparency, and updated information, this might have created some sampling bias. Capturing all the cases of the COVID-19 pandemic globally is a challenging and laborious process. Multiple resources have provided researchers with data related to the daily unfolding mortality and morbidity of the disease, such as the John Hopkins University Dashboard. We did not perform a comparison between these different data sources in our manuscript because of time constraints. However, future COVID-19 related projects should aim at doing so, to ensure the utmost accuracy and validity of the information.

Conclusion

This report highlights that the CFR is not a fixed value; rather, it is a dynamic value. Therefore, we strongly urge caution when dealing with CFR values, especially in an ongoing epidemic. Estimating the global CFR of COVID-19, we initially showed that the CFR meta-analyses differed according to the calendar date and days since the outbreak of the first confirmed case. We propose that a CFR according to days since the outbreak of the first confirmed case might be a better predictor of the current CFR of COVID-19 and its kinetics.

Funding

This work was not supported by any agency or grant. No financial compensation was provided to any of these individuals.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest directly applicable to this research.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ramy Abou Ghayda: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization, Supervision. Keum Hwa Lee: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration. Young Joo Han: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization. Seohyun Ryu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization. Sung Hwi Hong: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization. Sojung Yoon: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization. Gwang Hun Jeong: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization. Jinhee Lee: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization. Jun Young Lee: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization. Jae Won Yang: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization. Maria Effenberger: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization. Michael Eisenhut: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization. Andreas Kronbichler: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization. Marco Solmi: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization. Han Li: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization. Louis Jacob: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization. Ai Koyanagi: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization. Joaquim Radua: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization. Jae Il Shin: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Supervision, Project administration. Lee Smith: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.08.065.

Appendix B. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Baud D., Qi X., Nielsen-Saines K., Musso D., Pomar L., Favre G. Real estimates of mortality following COVID-19 infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(7):773. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30195-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battegay M., Kuehl R., Tschudin-Sutter S., Hirsch H.H., Widmer A.F., Neher R.A. 2019-novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV): estimating the case fatality rate – a word of caution. Swiss Med Wkly. 2020;150:w20203. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30195-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly A., Azra G., Gabriel L., Hedley A.J., Fraser C., Riley S. Epidemiological determinants of spread of causal agent of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. Lancet. 2003;361(9371):1761–1766. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13410-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisman D., Rivers C., Lofgren E., Majumder M.S. Estimation of MERS-coronavirus reproductive number and case fatality rate for the Spring 2014 Saudi Arabia Outbreak: insights from publicly available data. PLoS Curr. 2014;6 doi: 10.1371/currents.outbreaks.98d2f8f3382d84f390736cd5f5fe133c. ecurrents.outbreaks.98d2f8f3382d84f390736cd5f5fe133c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.D., Goel A. Estimating case fatality rates of COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(7):773–774. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30234-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J.P. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsitch M. Estimating case fatality rates of COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(7):775. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30245-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicine TKAoI . 2020. Version February 18, 2020.https://www.kaim.or.kr/bbs/index.html?code=corona&category=&gubun=&page=1&number=12025&mode=view&keyfield=&key= [Google Scholar]

- Öztoprak F. Case fatality rate estimation of COVID-19 for European Countries: Turkey’s current scenario amidst a global pandemic; comparison of outbreaks with European countries. EJMO. 2020;4(2):149–159. doi: 10.14744/ejmo.2020.60998. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Porta M. 5th ed. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2008. A dictionary of epidemiology. [Google Scholar]

- Rajgor D.D., Lee M.H., Archuleta S., Bagdasarian N., Quek S.C. The many estimates of the COVID-19 case fatality rate. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(7):776–777. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30244-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speciale A., Kresge N. vol. 2020. Bloomberg; 2020. (Virus spread pushes Italian hospitals toward breaking point). [Google Scholar]

- Spychalski P., Błażyńska-Spychalska A., Kobiela J. Estimating case fatality rates of COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(7):774–775. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30246-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine . 2020. Global Covid-19 case fatality rates — updated May 15.https://www.cebm.net/covid-19/global-covid-19-case-fatality-rates/ [Assessed 17 May 2020] [Google Scholar]

- The University of Tokyo Health Service Center . vol. 2020. 2020. https://www.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/general/COVID-19.html (Novel Coronavirus related illness (COVID-19)). [Google Scholar]

- Wilson N., Kvalsvig A., Barnard L.T., Baker M.G. Case-fatality risk estimates for COVID-19 calculated by using a lag time for fatality. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(6):1339–1441. doi: 10.3201/eid2606.200320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. [Accessed 19 Aug 2020] https://covid19.who.int/ [Google Scholar]

- Yang S., Cao P., Du P., Wu Z., Zhuang Z., Yang L. Early estimation of the case fatality rate of COVID-19 in mainland China: a data-driven analysis. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(4):128. doi: 10.21037/atm.2020.02.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Zhang B., Li P., Ma C., Gu J., Hou P. Incidence, clinical characteristics and prognostic factor of patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.17.20037572. 2020.03.17.20037572. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.