Abstract

Although direct detection of SARS-CoV2 in symptomatic or asymptomatic individuals is the ideal epidemiological tool for determining the burden of disease, the lack of availability of testing can preclude its wider implementation as a robust surveillance system. We correlated the use of the derivative influenza-negative influenza-like illness (fnILI) z-score from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as a proxy for incident cases and disease-specific deaths. For every unit increase of fnILI z-score, the number of cases increased by 376.5 (95% CI [202.5, 550.5]) and number of deaths increased by 10.2 (95% CI [5.4, 15.0]). FnILI data may serve as an accurate outcome measurement to track the spread of COVID-19 infection and disease, and allow for informed and timely decision-making on public health interventions.

Keywords: COVID-19, ILI, CDC, Influenza

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has spread exponentially since December 2019, transforming from a localized outbreak in Wuhan, China to a global pandemic.

As of August 22, 2020, 22.8 million cases of COVID-19 have been reported, with 5.5 million cases reported in the United States alone, and new hotspots continuing to emerge.1 The cumulative hospitalization rate in the US is estimated at 151.7 per 100,000, a rate which varies by age group; the all age case fatality rate is currently estimated at 6%, with similar discrepancies among age groups.2 , 3

As the number of individuals infected rapidly climbs, the testing capacity has been outpaced by the need for such tests. In the United States, this has posed a challenge to physicians and public health professionals at large, particularly as it relates to accurately tracking the spread of disease. Assessing the intensity of the epidemic nationally in a given region is the backbone of allocating resources at the federal and state level and informs the implementation or relaxing of public health restrictions (e.g. initiating or easing a lockdown).

Given the rapid increase in cases in the previous weeks without parallel expansion in testing capacity and unclear specificity/sensitivity, this problem will only continue to be exacerbated until a nationwide program is made available and further validation studies have been completed.4 In the interim, there is an urgent need to identify proxies for disease incidence that are routinely collected through the available infrastructure in the United States in order to guide the evolving public health response in this country.5

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) centrally collates data using the U.S. Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network (ILINet) and the National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System (NREVSS).6 We believe that combining both sources of this publicly-available, routinely collected data may serve as a reliable proxy for SARS-CoV-2 incidence and mortality. In this study, we used influenza-negative ILI (fnILI) z-scores and compared them against the reported COVID-19 cases and deaths by week, documenting trends over time.

Materials and methods

We downloaded flu negative influenza-like illness (fnILI) data derived from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention's ILINet and NREVSS data for states.6 , 7 ILINet consists of records from outpatient healthcare providers in all 50 states and reported 60 million patient visits in the 2018–2019 season. Weekly, approximately 2600 outpatient healthcare providers around the country report the total number of patients as well as those with influenza-like illness, defined as patients with a temperature of 100°F or greater alongside a cough and/or sore throat. Regional baselines are also reported. These data are weighted by state population, and the percentage of flu-positive influenza-like illness is compared to regional estimates and a historical nationwide baseline of 2.4%. NREVSS provides virologic surveillance data weekly from approximately 100 public health and over 300 clinical laboratories throughout the United States, including the total number of respiratory specimens tested for influenza, the number positive for influenza viruses, and the percent positive by influenza virus type. Some states may have limited data or have delays in reporting that may not make this information immediately available.

Reich et al.7 reviewed twenty-three seasons of influenza data beginning in 1997 and ten seasons of statewide data beginning in 2010 to calculate fnILI from the CDC.6 fnILI was determined using weighted influenza-like illness (wILI) from ILINet – which represents the percentage of doctor's office visits with a primary complaint of fever and one additional influenza-like symptoms – and percentages of positive influenza specimens from NREVSS data as compared to a baseline calculated from prior seasons of data extracted as described above. fnILI was calculated as:

These data included a z-score that represents the degree to which a given fnILI observation was significantly lower or higher than expected based on past trends at similar times during prior years. Z-score was calculated as:

with as the average weekly observations for the past nine years with one week on either side and sdfnILI as the associated standard deviation.

We merged this dataset with the CDC-reported SARS-CoV-2 cases and disease-specific deaths, and graphically represented the median fnILI z-score, cumulative cases, and cumulative deaths for the contiguous U.S for the month of July 2020. We used a mixed effects linear model accounting for clustering at the state level using random effects to determine the relationship between weekly case counts or deaths and fnILI z-score, and a lag term to account for delay between onset of symptoms and confirmation of diagnosis. The model with the lowest Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC)8 while maintaining statistical significance was selected. Median fnILI z-score across all states were determined by week and plotted against total nationwide cases and/or deaths per week. All data was analyzed using Stata v15.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Results

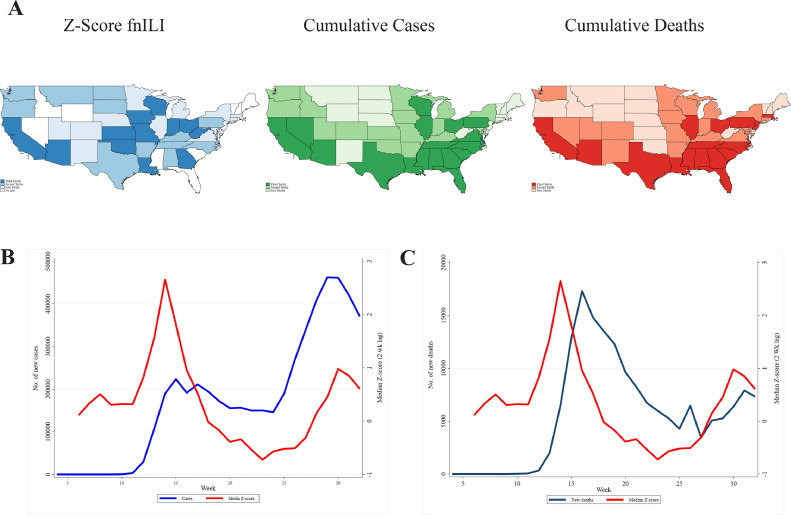

fnILI data was available for all states except Florida, New Hampshire, New Jersey, and Rhode Island. Over the course of the study period, January 19th, 2020 to August 9th, 2020, there were 4,999,815 reported COVID-19 cases and 161,547 deaths, representing a case-fatality rate of 3.2%. This rencompasses 31,576,019 unique patient visits across the US with an average of 2650 providers nationwide per week. The flu specimen positivity proportion across the study period was 18.4%, and the average flu positive baseline across the country was 1.3%. There is an apparent tracking between fnILI z-score and cases or deaths by state over the course of the study period as seen when comparing these indices during the month of July 2020 (Fig. 1 (A)).

Fig. 1.

Overall state-specific and median nationwide fnILI Z-Score versus COVID-19 cases or deaths. (A) Media fnILI z-scores and cumulative cases/deaths for individual states in the month of July 2020. (B) Nationwide weekly median fnILI z-scores versus new cases nationwide. (C) Nationwide weekly median fnILI z-scores versus deaths nationwide.

When assessing the correlation over time between fnILI z-score and either new cases or deaths, we observed a z-score peak prior to an increase in cases or deaths. Therefore, we used a lag variable of two weeks for incidence and mortality to better fit the model (Table 1 ). On the mixed effects linear model accounting for clustering at the state level using random effects, we found that for every unit increase of fnILI z-score two weeks prior, the number of cases increased by 376.5 (95% CI [202.5, 550.5]). Similarly, we found that for every unit increase of fnILI z-score two weeks prior, the number of deaths increased by 10.2 (95% CI [5.4, 15.0]), also when correcting for regional effects. When plotting the median nationwide z-score two week prior versus new cases (Fig. 1(B)) or deaths (Fig. 1(C)), the two measures tracked.

Table 1.

Possible models for fnILI Z-score and incidence or mortality.

| Incidence | Lag | Coef. | 95% CI |

p | AIC | BIC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| None | 268.4 | 108.8 | 428.0 | <0.01 | 24584.5 | 24604.9 | |

| 1 Week | 364.1 | 196.3 | 531.9 | <0.01 | 23945.6 | 23965.9 | |

| 2 Week | 376.5 | 202.5 | 550.5 | <0.01 | 23205.6 | 23225.8 | |

| Mortality | None | −4.8 | −9.2 | −0.3 | 0.04 | 15885.7 | 15906.1 |

| 1 Week | 2.3 | −2.4 | 6.9 | 0.34 | 15480.1 | 15500.9 | |

| 2 Week | 10.2 | 5.4 | 15.0 | <0.01 | 14990.1 | 15010.3 | |

Discussion

Early delays in delivery of COVID-19 diagnostic tests combined with dramatic demand and administrative hurdles slowed initial testing rates, leading to underreporting of cases.9 , 10 Despite rising capacity, demand for testing in the US has consistently outpaced supply well into May and June, and despite improvements, emerging hotspots in July have led to reduced capacity in hard hit areas.11 , 12 Analyses of reported death numbers have found that less than 2 percent of COVID-19 cases were reported, pointing to extreme underreporting of cases,13 necessitating alternative methods to accurately assess these trends over time. Our results suggest that the fnILI z-score data can be used as a proxy for the trajectory of disease incidence and mortality in the United States. In the context of limited resources in a rapidly changing field, it becomes increasingly necessary to innovatively utilize available infrastructure to tackle the apparent gaps in knowledge quickly. To our knowledge, this is the first academic study to use fnILI z-scores from ILINet and NVRESS data in order to model and potentially predict the burden of COVID-19 over time.

This report demonstrates the important potential of such a proxy and validates its correlation with incidence and mortality. Importantly, we present the optimal model for such a prediction by building in a lag term. This two week lag term is likely necessary for incidence and mortality due to the known incubation period of this disease and because of a delay in testing.14

The median incubation period of COVID-19 is estimated at around 5 to 6 days overall, with a longer incubation time in the older populations that make up the bulk of cases.15 , 16 Despite improvements in numbers of tests, a recent survey found that around 18% of tests are were found to have long delays, and 10% reported a delay of up to 10 days.17 , 18

Many tests are still restricted to those with symptoms, with higher wait times among those who are disproportionately affected by disease.17 Our two-week lag term provides a sufficiently robust estimate, factoring in variability in incubation times and testing delays. These lag terms also may allow our model to function as an early warning system for rise in cases, similar to ILINet.

As there is a robust infrastructure in place to collect these data, validating the use of such data is extremely valuable, especially in the setting of limited testing capacity. fnILI provides a good proxy in the absence of testing to evaluate the results of public health interventions and make timely decisions to change course.

Acknowledgments

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interests to disclose.

Funding/support

This study was funded by the Yale Institute for Global Health.

Statement of prior presentation

This information has not been previously presented.

References

- 1.WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. Retrieved2020, fromhttps://covid19.who.int

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020. COVIDView, key updates for week 33.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/covidview/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pormohammad A., Ghorbani S., Baradaran B., Khatami A., Turner R., Mansournia M.A., Kyriacou D.N., Idrovo J.-.P., Bahr N.C. Clinical characteristics, laboratory findings, radiographic signs and outcomes of 61,742 patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Microb Pathog. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Gennaro F., Pizzol D., Marotta C., Antunes M., Racalbuto V., Veronese N. Coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) current status and future perspectives: a narrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet] 2020;17(8):2690. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082690. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/8/2690 Available from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ienca M., Vayena E. On the responsible use of digital data to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat Med. 2020;26(4) doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0832-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020. U.S. influenza surveillance system: purpose and methods.https://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/overview.htm [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reich N.G., Ray E.L., Gibson G.C., Cramer E R.C. Looking for evidence of a high burden of COVID-19 in the United States from influenza-like illness data. Github. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Konishi S., Kitagawa G (Genshiro) Springer; 2007. Information criteria and statistical modeling. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pitzer V.E., Chitwood M., Havumaki J., Menzies N.A., Perniciaro S., Warren J.L., Weinberger D.M., Cohen T. The impact of changes in diagnostic testing practices on estimates of COVID-19 transmission in the United States. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1093/aje/kwab089. 2020.04.20.20073338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bendavid E., Mulaney B., Sood N., Shah S., Ling E., Bromley-Dulfano R. COVID-19 antibody seroprevalence in santa Clara county, California. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyab010. 2020.04.14.20062463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NPR. Despite early warnings, U.S. took months to expand swab production for COVID-19 test. NPR. Retrieved August 23, 2020, fromhttps://www.npr.org/2020/05/12/853930147/despite-early-warnings-u-s-took-months-to-expand-swab-production-for-covid-19-te

- 12.Feuer W. U.S. coronavirus response still crippled by lack of testing, Dr. Scott Gottlieb says. CNBC. 2020 https://www.cnbc.com/2020/07/06/us-coronavirus-response-still-crippled-by-lack-of-testing-dr-scott-gottlieb-says.html [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lau H., Khosrawipour T., Kocbach P., Ichii H., Bania J., Khosrawipour V. Evaluating the massive underreporting and undertesting of COVID-19 cases in multiple global epicenters. Pulmonology. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.pulmoe.2020.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guan W., Ni Z., Hu Y., Liang W., Ou C., He J. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khalili M., Karamouzian M., Nasiri N., Javadi S., Mirzazadeh A., Sharifi H. Epidemiological characteristics of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol. Infect. 2020;148:e130. doi: 10.1017/S0950268820001430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kong T.-.K. Longer incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in older adults. Aging Med. 2020;3(2):102–109. doi: 10.1002/agm2.12114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ognyanova, K., Lazer, D., & Baum, M. (n.d.). The state of the nation: a 50-state COVID 19 survey. 7.

- 18.Mervosh S., Fernandez M. ‘It's like having no testing’: coronavirus test results are still delayed. The New York Times. 2020 [Google Scholar]