Abstract

Background and aims

Coronavirus pandemic is currently a global public health emergency with no definitive treatment guidelines. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature evaluating the efficacy of hydroxychloroquine and its related formulations in COVID-19 patients.

Methods

A systematic search of PubMed, Scopus, MedRxiv data and Cochrane Central Register of Clinical Trials for published articles that reported the outcomes of COVID-19 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine or its compounds was done. We identified 1071 published studies and 7 studies were included in the analysis.

Results

The study population consisted of a total of 4984 patients, of which 1721 (34.5%) received hydroxychloroquine or its congeners (HCQ group) while 3091 (62.01%) received standard of care or had included antiviral medication (control group). The pooled estimate of successful treatment in the hydroxychloroquine group and the control group was 77.45% and 77.87% respectively, which indicated similar clinical outcomes in patients treated with hydroxychloroquine compared to the control group. The odds ratio of a favourable outcome with hydroxychloroquine was 1.11 (95 CI 0.72 to 1.69) (p = 0.20). The pooled risk difference of favourable outcome with hydroxychloroquine versus control group was 0.00 (95 CI -0.03 to 0.03) which was statistically not significant (p = 0.10).

Conclusions: The present evidence shows no benefit of hydroxychloroquine in patients affected by mild to moderate COVID-19 disease. However, now several trials on HCQ are ongoing and hopefully more data will be available soon. Hence, the management of COVID-19 is set to change for better in the future.

Keywords: Chloroquine, Hydroxychloroquine, COVID-19, Mortality, SARS-CoV-2 infection

Highlights

-

•

This meta-analysis includes only randomised controlled trials, with systematic review of recently published data.

-

•

Hydroxychloroquine has no benefit in treatment of mild to moderate COVID-19 disease.

-

•

Large size multi-centre studies are required for further evaluation.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 is the worst pandemic with more than 17 million cases and more than 670 thousand deaths so far [1]. The rapid spread of the disease around the globe affecting most of the countries in a short period prompted the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare a global health emergency on January 31 and the disease was recognized as a pandemic on March 11 [2]. The earliest evidence regarding the impending outbreak due to human-to-human transmission of 2019-nCoV was reported by Wang and colleagues [3], leading to drastic containment measures to limit the spread of the virus. However, despite such severe measures the number of cases continues to rise exponentially causing significant morbidity and mortality.

There is no specific pharmacological treatment that is proven effective in controlling the SARS-CoV-2 infection or its spread. Specific drugs to treat the infection might take several years to develop. At present, the mainstay of the clinical management of severely ill COVID-19 patients involves intensive monitoring of the clinical status with systemic support. The mortality rate in COVID-19 is observed to be highest among the elderly patients which might be due to the age-related immune dysfunction complicated with the associated comorbidities [[4], [5], [6]]. With no effective drug available against the SARS-CoV-2 infection, the focus is on identifying existing drugs that may be effective against the virus [7,8]. The experiences in the past outbreaks with other strains of coronavirus, i.e. SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, have identified chloroquine and its congeners as the possible target drugs which are now under extensive research in clinical trials.

The antiviral activity of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine was initially studied during the SARS-CoV-1 outbreak in 2003 [9]. A number of mechanisms have been reported in the literature. Some data show that the potential broad-spectrum antiviral activity of these drugs is due to the inhibition of various stages of viral infection like the entry, transport, and post-entry stages of SARS-CoV-2 [10]. The evidence in the literature suggests hydroxychloroquine is better than chloroquine in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 in vitro [11]. Recently, many publications have shown the possible benefit of hydroxychloroquine as monotherapy or as a part of combination therapy for the treatment and prevention of SARS-CoV-2 infection but few have shown no benefits.

We conducted a systematic review of the available studies and meta-analysis of the comparative studies to analyze the efficacy and safety of hydroxychloroquine and its related formulations in patients with COVID-19.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy and selection criteria

An extensive search of the literature in PubMed, Scopus, MedRxiv data, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials database was performed on July 28, 2020, to extract published articles that reported the outcomes effects of hydroxychloroquine or its compounds in treating COVID-19. The search string used for the literature search was as follows: (hydroxychloroquine) and (COVID-19). The search was broadened to include all the possible relevant studies. We did not place any restrictions on the date of publication.

After preliminary screening of the results, duplicates were eliminated. The remaining abstracts were subjected to independent review by the two authors of the study (SKP and PT) and the full text of articles regarded as potentially eligible for further consideration was extracted for further analysis. Thereafter, eligible articles were selected for final analysis according to predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. All articles which compared chloroquine and chloroquine-related formulations with the control group for COVID-19 were included. We included only comparative trials involving human subjects with clearly defined clinical outcome measures. The exclusion criteria included animal studies; in vitro studies; absence of a comparison group; absence or unclear reporting of clinical outcome measures. As much of the data on COVID-19 is from China and Europe, no language restrictions were imposed. We used the SYSTRAN language translator for the translation of non-English articles.

3. Data analysis

The following information was extracted from included studies in the systematic review: The first author, publication date, type of study, total patients, and characteristics of the experimental and control group, outcome measures, complications were extracted from the included studies. The outcome included in the current study is clinical improvement or negative RT-PCR test as successful treatment and need for mechanical ventilation or death as failure. The Cochrane Collaboration and the Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses guidelines were followed during the meta-analysis. The publication bias of the included studies for meta-analysis was calculated with funnel plot analysis and Egger’s regression asymmetry test. A p-value of less than 0.05 level was considered statistically significant. For each study, we calculated the odds ratio (OR), risk difference (RD), and relative risk (RR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Heterogeneity between comparable studies was tested with the chi-square and Higgins I2 test. P-value of less than 0.1 or an I2 value higher than 50% meant significant heterogeneity and a random-effects model should be applied. The random-effect model was used to estimate the odds ratio (OR) for comparing favourable outcomes of hydroxychloroquine and control group. All analyses were performed using STATA version 14.0 software (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) and R studio desktop v1.2.50 (RStudio, Inc, Boston).

Role of the funding source

There was no funding source for this study. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

4. Results

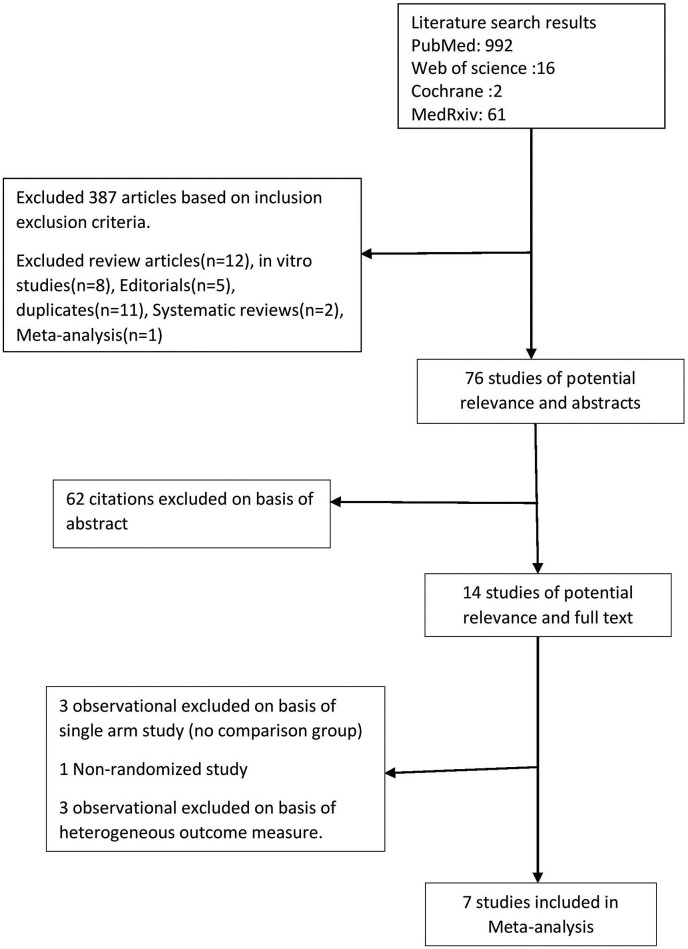

992 articles were identified from PubMed, 16 from Web of Science, 2 from Cochrane and 61 from MedRxiv after the initial search. 76 studies of potential relevance reviewed. 62 citations were excluded on the basis of title and abstract review. The remaining 14 papers were reviewed on the basis of their full-texts. Of these, 3 were excluded as it lacked a comparison group, one was excluded as it was non randomized and 3 were excluded due to non-uniformity in outcome measure. We finally selected 7 articles for the meta-analysis (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Algorithm for database search and article selection.

5. Demographic and treatment characteristics results

The study population consisted of a total of 4984 patients, of which 1721 (34.53%) were treated with hydroxychloroquine or its congeners (HCQ group) while 3091 (62.01%) were managed with standard of care (control group) while the remaining 172 patients were excluded from the final analysis as they received azithromycin along with hydroxychloroquine (Table 1 ). The mean age of patients in experimental group was 45.8 years, and in the control group patients was 47.3 years (p = 0.61). Mean duration of symptoms before initiating the treatment was 5.21 days for patients in experimental group and 5.76 days in control group (Table 2 ).

Table 1.

Sample size of selected studies and treatment details.

| Authors | Year | Country | Type of study | Total patients | Treatment Group (HCQs) | Control group | Experimental group intervention | Control group intervention | Outcomes measure for metanalysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen J et al.23 | March 2020 | China | RCT | 30 | 15 | 15 | HCQs 400 mg/day for 5 days | SOC | RT-PCR for nasopharyngeal swab |

| Chen Z et al.24 | March 2020 | China | RCT | 62 | 31 | 31 | HCQs 400 mg/day for 5 days | SOC | Time to clinical recovery Clinical characteristics Radiological results |

| Huang et al.25 | April 2020 | China | RCT | 22 | 10 | 12 | CQ 500 mg twice daily for 10 days | Lopinavir/ritonavir (400/100 mg) and SOC | RT-PCR Lung CT Length of hospitalization |

| W Tang et al.26b | May 2020 | China | RCT | 150 | 70 | 80 | HCQs (loading dose of 1200 mg daily for three days followed by a maintenance dose of 800 mg daily)Total duration:2–3 weeks | SOC | RT-PCR |

| Cavalcanti et al.28 | July 2020 | Brazil | RCT | 504a | 159 | 173 | HCQs at a dose of 400 mg twice daily for 7 days | SOC | Need for mechanical ventilation or Death at 15 days |

| Oriol et al.29 | July 2020 | Spain | RCT | 293 | 136 | 157 | HCQs 800 mg on day 1 followed by 400 mg once daily for 6 days | SOC | Need for mechanical ventilation or Death at 7 days |

| Horby P et al.27 | July 2020 | UK | RCT | 4716 | 1561 | 3155 | HCQs 800 mg on day 1 followed by 400 mg twice daily for 9 days or until discharge | SOC | Need for mechanical ventilation or Death |

172 patients were excluded as they received Azithromycin in addition to Hydroxychloroquine.

Concomitant treatment such as antiviral agents, antibiotics, and systemic glucocorticoid therapy was given to both groups.

Table 2.

Summary of demographics data and duration of symptoms from the included studies.

| Study | Age ± SD (Years) |

Sex (Male/Female) |

Duration of Symptoms± SD (Days) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Control | Treatment | Control | Treatment | Control | |

| Chen J et al. | 50.5 ± 3.8 | 46.7 ± 3.6 | 9/6 | 12/3 | 6.6 ± 3.9 | 5.9 ± 4.1 |

| Chen Z et al. | 44.1 | 45.2 | 14/17 | 15/16 | 3.2 | 3.2 |

| Huang et al. | 41.5 | 53.0 | 7/3 | 6/6 | 2.5 | 6.5 |

| W Tang et al. | NR | NR | NR | NR | 16.6 ± 10.5 | 16.6 ± 10.5 |

| Cavalcanti et al. | 51.3 | 49.9 | NR | NR | 7 | 7 |

| Oriol et al. | 41.6 | 41.7 | 38/98 | 54/103 | 3 | 3 |

| Horby P et al. | NR | NR | 961/600 | 1974/1181 | 9 | 9 |

SD Standard Deviation, NR Not reported.

6. Outcome results

The pooled estimate of successful treatment in the HCQ group was 77.45% and that in the control group was 77.87% indicating similar clinical outcomes in patients treated with hydroxychloroquine compared to the control group.

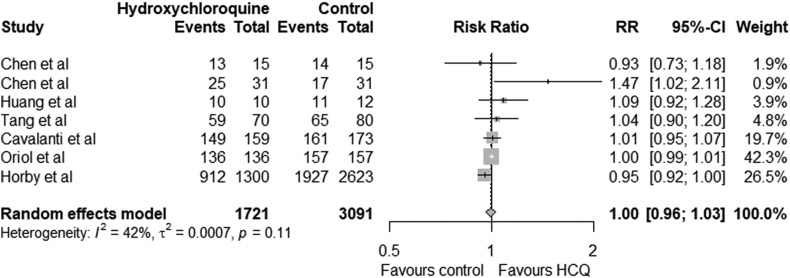

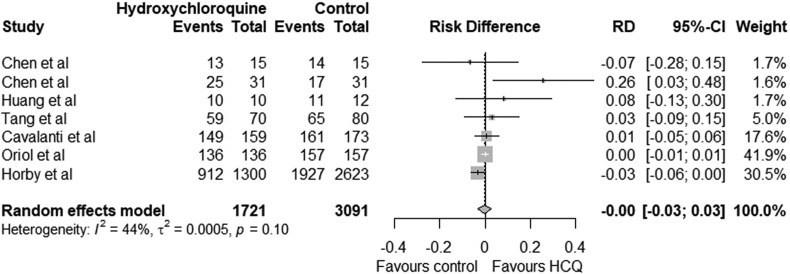

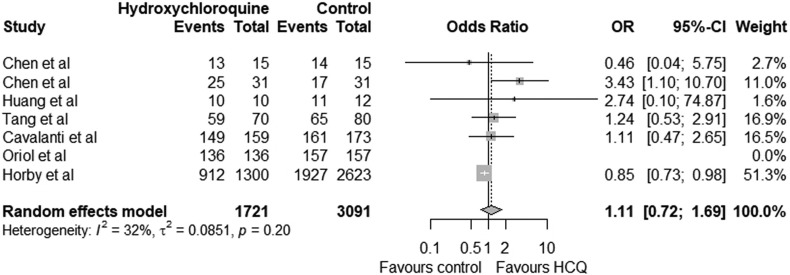

The pooled relative risk for favourable outcome with hydroxychloroquine was 1.00 (95% CI 0.96–1.03) which was statistically not significant (p = 0.11). The lower limit of confidence interval is less than 1 indicating hydroxychloroquine may not have significant benefit (Fig. 2 ). The pooled risk difference of favourable outcome with hydroxychloroquine compared to the control group was 0.00 (95 CI -0.03 to 0.03) which was statistically not significant (p = 0.10) (Fig. 3 ). The use of hydroxychloroquine was associated with an equivocal favourable outcome. The odds ratio of favourable outcome with hydroxychloroquine was 1.11 (95 CI 0.72 to 1.69) (p = 0.20) (Fig. 4 ). Six of the seven included studies reported adverse effects in treatment and control group which is summarised in Table 3 .

Fig. 2.

Forest plot illustrating the relative risk (RR) for favourable outcome between Treatment group (hydroxychloroquine) and control group in COVID-19 patients.

Fig. 3.

Risk differences (RD) with 95% confidence interval for favourable outcome between Treatment group (hydroxychloroquine) and control group in COVID-19 patients.

Fig. 4.

Odds ratio (OR)with 95% confidence interval for successful outcome of Treatment group (hydroxychloroquine) and control group in COVID-19 patients.

Table 3.

Summary of reported adverse effects in both the groups of all seven studies.

| Study | Patients in Treatment group (n) | Adverse effect in Treatment group(n) | Patients in Control group(n) | Adverse effect in Control group(n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen J et al. | 15 | Diarrhea (2) Disease progression (1) Elevated AST (1) |

15 | Elevated ALT (1) Elevated creatinine (1) Anemia (1) |

| Chen Z et al. | 31 | Rash (1) Headache (1) |

31 | None |

| Huang et al. | 10 | NR | 12 | NR |

| W Tang et al. | 70 | Serious adverse effects (2) Disease progression (1) Upper respiratory infection (1) Non serious adverse effects (19) Diarrhea (7) Vomiting (2) Other mild adverse effects (10) |

80 | Serious adverse effects (0) Non serious adverse effects (7) |

| Cavalcanti et al. | 159 | QTc prolongation (13) Arrythmia (3) Bradycardia (1) Supraventricular tachycardia (2) Pulmonary Embolism (1) Nausea (9) Bloodstream infection (1) Anemia (14) Elevated ALT or AST level (17) Hypoglycemia (1) Elevated bilirubin level (5) Leukopenia (3) |

173 | QTc prolongation (1) Arrythmia (1) Bradycardia (1) Brochospasm (1) Nausea (2) Vomiting (1) Anemia (11) Elevated ALT or AST level (6) Elevated bilirubin level (2) Leukopenia (3) |

| Oriol et al. | 136 | Gastrointestinal disorders (7), Nervous system disorders (3), Infections (12) Metabolism and Nutritional disorders (1) General disorders (1) |

157 | Gastrointestinal disorders (148) Ear and Labrynth disorders (5) Eye disorders (5) Infections (9) Metabolism and Nutritional disorders (2) General disorders (30) Injury, poisoning and procedural complications (1) Metabolism and nutrition disorders (2) Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders (1) Nervous system disorders (63) Psychiatric disorders (2) Renal and urinary disorders (1) Reproductive system and breast disorders (1) Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders (11) Vascular disorders (1) |

| Horby P et al. | 1561 | Cardiac Arrythmia (698) Supraventriclar tachycardia (48) Ventricular tachycardia (6) Atrioventricular block (6) Torsades de Pointes (1)∖ |

3155 | Cardiac Arrythmia (1357) Supraventriclar tachycardia (80) Ventricular tachycardia (9) Atrioventricular block (13) |

NR Not reported, ALT Alanine aminotransferase, AST Aspartate aminotransferase.

7. Discussion

To best of our knowledge, this would be a meta-analysis in which assessment was performed of studies which had a total of more than four thousand nine hundred patients with COVID-19. In the current meta-analysis, we included 14 published studies with study population consisted of a total of 4984 patients, of which 34.53% were treated with hydroxychloroquine or its congeners (HCQ group) while 62% were managed with standard of care (control group). The use of HCQ does not show any significant benefit in patients affected by COVID-19 disease.

Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) and its congeners have long been used in the treatment of malaria. In the past, hydroxychloroquine has been evaluated in many in-vitro studies for its antiviral activity against a wide range of viruses including SARS-CoV-1 and MERS [9,[12], [13], [14]]. Hydroxychloroquine was found to be effective against SARS-CoV-2 in various studies conducted in the early weeks of the COVID-19 outbreak. The studies initially emerged from China, the epicenter of the outbreak. Wang and colleagues had demonstrated the antiviral efficacy of chloroquine on SARS-CoV-2 in VeroE6 cell culture [15]. Subsequently, Yao et al. [11] reported that the hydroxychloroquine was more potent than chloroquine in inhibiting the viral growth on Vero cell culture. Simultaneously, similar reports emerged which indicated satisfactory antiviral activity of hydroxychloroquine in-vitro [9,16,17]. These reports formed the basis for further clinical trials. However, recently several clinical trials have published the results, which have been incorporated in our present analysis. At the latest, the clinical trials registry had 467 clinical trials in different stages of completion however few of the trials have been prematurely stopped after the preliminary results of RECOVERY trial which showed no clinical benefit from the use of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 disease [18].

There was growing advocacy for the use of hydroxychloroquine in pre-and post-exposure prophylaxis by governments across the world. In the mid-February Chinese trials found chloroquine to be effective in patients with COVID -19, leading to a panel recommendation of its use in china for COVID-19 [19]. An advisory by the government of India recommended hydroxychloroquine 400 mg once a week after an initial loading dose of 400 mg twice on Day 1 for healthcare workers and those asymptomatic household contacts of COVID-19 patients [20]. On March 28, 2020, The US Food and Drug Administration issued an emergency use authorization for hydroxychloroquine for patients with COVID-19, however, the recommendation was withdrawn on June 15, 2020 [21].

The evidence emerging from the analysis of a limited number of clinical studies available in the literature suggests that the use of hydroxychloroquine has the potential to help in early clinical recovery in patients affected by novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19). The earliest reports of clinical benefits of hydroxychloroquine were reported by Gao and colleagues in the in COVID-19 pneumonia [22]. Later, Chen et al. [23] found no significant benefit in the virologic clearance with chloroquine. However, a larger study by the same author [24] had established that chloroquine had a significant early time-to-clinical-recovery (TTCR) and better resolution of pneumonia on chest CT images. Huang et al. [25] in their study involving 22 patients reported early virologic clearance and subsequently better rates of discharge from the hospital over the lopinavir/ritonavir combination. However, Wei Tang et al. [26], reported that the clinical benefit of hydroxychloroquine was no better compared to the standard of care alone in patients with mild to moderate COVID-19. On the contrary, hydroxychloroquine had resulted in increased adverse events. In a recent randomised control trial with 4716 patients, the authors found higher risk of mechanical ventilation or death in patients treated with hydroxychloroquine compared to control (risk ratio 1.12, 95CI 1.01 to 1.25), however no significant difference in 28-day mortality was found between the groups [27]. In a study by Cavalanti et al. [28], the authors reported that the odds of clinical improvement were not significantly different with hydroxychloroquine or standard of care. On the other hand, there was an increase in the cardiac and hepatic adverse events with hydroxychloroquine. Oriol Mitjà et al. [29] in a study involving 293 patients, found hydroxychloroquine to be no better than standard care. A meta-analysis of the reported trials by Sarma et al. [30] had included three studies [23,24,31] for the analysis (two of those have been included in the present analysis as well). They had reported clinical benefit of the hydroxychloroquine in terms of a lower number of cases deteriorating clinically or radiologically without much increase in adverse events. However, our analysis shows hydroxychloroquine of no benefit in mild to moderate cases which concurs with results reported by Singh et al. [32].

We also reviewed non randomised and other single-arm observational studies involving hydroxychloroquine (Table 4 ) (Table 5 ). Gautret et al. [31] had reported successful virologic clearance in 57.1% (8/14) patients who had received hydroxychloroquine, which increased to 100% (6/6) if azithromycin was added to the treatment. In another study [33] lead by the same author, authors had reported clinical improvements with viral cultures turning negative within 5 days in 97.5% of the patients treated with a combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin. The nasopharyngeal viral load also showed a rapid decline as measured by qPCR with 93% patients turning negative on Day 8. In another study, Molina et al. [34] had followed an aggressive treatment regimen (hydroxychloroquine plus azithromycin) as followed by Gautret et al. in 11 patients. They reported no evidence of aggressive virologic clearance demonstrated in the earlier studies. A retrospective study by Million and colleagues [35], involving 1061 patients reported good clinical outcome and virologic cure in 91.7% (n = 973) patients receiving HCQ and the reported death rate in the group was 0.75% (n = 8). Recently, Geleris [36] and his colleagues from New York, in an observational study had included 1446 patients. They reported no effect of HCQ on decreasing or increasing the risks of the evaluated points (i.e. intubation or death) with a hazard ratio of 1.04 (95% confidence interval, 0.82 to 1.32). Mahévas et al. [37] studied the effect of HCQ in 181 patients on ICU transfer rate and overall survival, both indirect indicator of clinical deterioration. The reported weighted hazard ratio was 0.9 (95% confidence interval 0.4 to 2.1), indicating no effect on either decreasing the ICU transfer or overall survival with HCQ therapy compared to the control group of the patients. In a retrospective analysis by Bo Yu [38] et al. of 550 patients, 48 had received HCQS. They reported significantly less fatalities in HCQ group, 18.8% (9/48)] compared to 47.4% (238/502) in control group. The results of our meta-analysis shows that hydroxychloroquine has equivocal results as compared to the control group. The odds ratio of 1.11, and a wide range of confidence interval (95 CI 0.72 to 1.69) indicate no significant benefit of hydroxychloroquine in clinical improvement of mild to moderate COVID-19 disease.

Table 4.

Details of non randomised trials comparing hydroxychloroquine to standard of care.

| Authors | Type of study | Total patients | Treatment Group (HCQ) | Control group | Experimental group intervention | Control group intervention | Addition of Azithromycin | Outcomes measured |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mahévas et al.37 | Non-RCT | 173 | 92 | 89 | HCQ 600 mg/day | Standard of care | No | Primary: ICU transfer, Secondary: Overall survival, survival without acute respiratory distress syndrome, weaning from oxygen, and discharge from hospital |

| Geleris et al.36 | Non-RCT | 1376 | 811 | 565 | HCQ (600 mg twice on day 1, then 400 mg daily for a median of 5 days | Standard of care | No | Time -to -event analysis of intubation or death |

| Gautret et al.31 | Non-RCT | 36a | 14 | 16 | Hydroxychloroquine 200 mg thrice daily for 10 days | Standard of care | Yes(6 patients in HCQ group) | RT-PCR and clinical improvement. |

Six patients were excluded as they received Azithromycin in addition to Hydroxychloroquine.

Table 5.

Details of studies with hydroxychloroquine and no control group (Single arm studies).

| Study | Type of Study | Total patients | Favourable outcome | Dose of Hydroxychloroquine | Azithromycin | Outcome measured |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gautret et al. | Prospective Observational | 80 | 65 (81.25%) | Hydroxychloroquine 200 mg thrice daily for 10 days | Yes | Viral Load at Day 7 Viral Cultures at Day 5 Chest CT |

| Molina et al. | Prospective Observational | 11 | 0 (0%) | Hydroxychloroquine 600 mg/d for 10 days | Yes | Qualitative PCR of nasopharyngeal swab |

| Million et al. | Retrospective | 1061 | 973 (91.7%) | Hydroxychloroquine 200 mg thrice daily for 10 days | Yes | Death, clinical worsening (transfer to ICU, and >10 day hospitalization), viral shedding persistence (>10 days) |

The efforts are also directed to study the efficacy of chloroquine, a congener of hydroxychloroquine. Both these drugs are thought to have similar antiviral activity. Borba et al. [39] in a randomised trial reported a viral clearance of only 22.2% in respiratory secretions on day 4 of treatment with chloroquine. There are reports of enhancing the antiviral activity of the hydroxychloroquine by additives like zinc [40] which can have synergistic action, however their role is still uncertain.

Hydroxychloroquine is a derivative of chloroquine with well-known safety profile. However, recently reports of life-threatening adverse effects have emerged from patients with COVID-19. The concern of QT prolongation, especially when combined with azithromycin has been discussed extensively in the literature [41]. In the present analysis, Gautret et al. [31] has shown that the combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin is more effective in clearing the nasopharyngeal carriage of SARS-CoV-19 at day 6 of treatment. However, the study could not establish the effect of the combination on QT prolongation. There is also the concern of drug-induced hepatotoxicity, which might affect the outcome in patients with comorbidities [42]. The pilot study by Chen.et al. [23] on 30 patients in 2 groups did not find any significant effect of hydroxychloroquine in virologic clearance on day 7. The incidence of reported adverse events in both groups were similar. They had not commented on effect on QT-interval. Mahevas et al. [37] reported 8 patients needing discontinuation of treatment due to cardiovascular adverse effects reported. Molina et al. [34] reported a case of QTc prolongation with hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin combination which needed discontinuation of the treatment. Although increased duration of treatment and concomitant usage of anti-epileptics, anti-psychotics, moxifloxacin and azithromycin can increase the risk of QT interval prolongation it should also be noted that there is concern for QTc prolongation and torsades de pointes with even short-term use of hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19 [28,43].

Another aspect to consider while addressing the question of adverse reactions is the optimum dose required for the adequate activity. Hydroxychloroquine requires administration of a loading dose followed by a maintenance dose. However, there is difference in the doses administered across the studies which attempt to balance the antiviral activity against the adverse events [44]. Studies conducted in China reported using a lower dose (400 mg/day for 5 days) [23,24] compared to the studies in those from France where an aggressive treatment strategy (200mgx 3times/day x 10days) has been followed [31,33]. These studies also represent a dilemma in responses of different nations across the world to recommend appropriate dosing regimens. An expert panel in China recommended the use of chloroquine 500 mg twice a day regimen [19]. However Borba et aL recommended against use of higher dose of chloroquine in severely ill COVID-19 patients, in view of increased lethality and prolonged QTc intervals with high doses. However, it is to be noted that the authors had also included azithromycin in the treatment protocol which may have accentuated the cardiac effects of chloroquine [39]. Salunke et al. had proposed a ABCD score which may help to classify patients according to severity of disease and this may help to medically manage patients with COVID-19 [45]. This may help to categorize and treat patients with COVID-19 infection.

8. Limitations of this study

The limitations of current metaanalysis were that an inherent bias could exist, particularly in terms of patient selection, heterogeneous medical treatment regimens in the selected studies. Secondly the study population and dosage of HCQ drug varies in the included studies.

The results need to be concluded with caution since judgment criteria between severe and non-severe patients were not uniform. Another fact that some patients can have multiple comorbidities that can produce their added effect on serious events and HCQ drug may have not been effective due to multiple reasons. We do note that the available evidence from these studies requires further validation by larger well-structured RCT’s. Most of the studies conducted in early part of the outbreak suffered from lack of adequate power, inadequate randomisation, improper reporting of the outcomes. However, now several trials are ongoing and hopefully more data will be available soon. Simultaneously, there are parallel attempts being made to develop an effective drug and a vaccine. Hence, the management of COVID-19 is set to change for better in the days to come.

9. Conclusion

Hydroxychloroquine is inexpensive, readily available drug but the present evidence does not show any significant benefit in patients affected by COVID-19 disease. However, now several trials on HCQ are ongoing and hopefully more data will be available soon. Hence, the management of COVID-19 is set to change for better in the future.

Respected editor

We intend to publish an article entitled “No Benefit of Hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19: Results of Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials” in your esteemed journal.

On behalf of all the contributors I will act and guarantor and will correspond with the journal from this point onward.

AZT Azithromycin, RT-PCR Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, HCQs Hydroxychloroquine, CQ Chloroquine, SOC Standard of Care.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None.

References

- 1.WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard n.d.

- 2.WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 n.d.

- 3.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in wuhan, China. J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/JAMA.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh A., Shaikh A., Singh R., Singh A.K. COVID-19: from bench to bed side. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2020;14:277–281. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nandy K., Salunke A., Pathak S.K., Pandey A., Doctor C., Puj K. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the impact of various comorbidities on serious events. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2020;14:1017–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.06.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salunke A.A., Nandy K., Pathak S.K., Shah J., Kamani M., Kotakotta V. Impact of COVID -19 in cancer patients on severity of disease and fatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh A.K., Singh A., Singh R., Misra A. Remdesivir in COVID-19: a critical review of pharmacology, pre-clinical and clinical studies. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2020;14:641–648. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai Q., Yang M., Liu D., Chen J., Shu D., Xia J. 2020. Experimental treatment with favipiravir for COVID-19: an open-label control study. Engineering. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keyaerts E., Vijgen L., Maes P., Neyts J., Ranst M Van. In vitro inhibition of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus by chloroquine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;323:264–268. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.08.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Savarino A., Boelaert J.R., Cassone A., Majori G., Cauda R. Effects of chloroquine on viral infections: an old drug against today’s diseases? Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:722–727. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00806-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yao X., Ye F., Zhang M., Cui C., Huang B., Niu P. In vitro antiviral activity and projection of optimized dosing design of hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paton N.I., Lee L., Xu Y., Ooi E.E., Cheung Y.B., Archuleta S. Chloroquine for influenza prevention: a randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:677–683. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farias K.J.S., Machado P.R.L., de Almeida Junior R.F., de Aquino A.A., da Fonseca B.A.L. Chloroquine interferes with dengue-2 virus replication in U937 cells. Microbiol Immunol. 2014;58:318–326. doi: 10.1111/1348-0421.12154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Wilde A.H., Jochmans D., Posthuma C.C., Zevenhoven-Dobbe J.C., Van Nieuwkoop S., Bestebroer T.M. Screening of an FDA-approved compound library identifies four small-molecule inhibitors of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus replication in cell culture. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:4875–4884. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03011-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang M., Cao R., Zhang L., Yang X., Liu J., Xu M. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30:269–271. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu J., Cao R., Xu M., Wang X., Zhang H., Hu H. Hydroxychloroquine, a less toxic derivative of chloroquine, is effective in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro. Cell Discov. 2020;6:16. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-0156-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vincent M.J., Bergeron E., Benjannet S., Erickson B.R., Rollin P.E., Ksiazek T.G. Chloroquine is a potent inhibitor of SARS coronavirus infection and spread. Virol J. 2005;2 doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-2-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.No clinical benefit from use of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalised patients with COVID-19 — RECOVERY Trial. https://www.recoverytrial.net/news/statement-from-the-chief-investigators-of-the-randomised-evaluation-of-covid-19-therapy-recovery-trial-on-hydroxychloroquine-5-june-2020-no-clinical-benefit-from-use-of-hydroxychloroquine-in-hospitalised-patients-with-co n.d.

- 19.Multicenter collaboration group of Department of Science and Technology of Guangdong Province and Health Commission of Guangdong Province for chloroquine in the treatment of novel coronavirus pneumonia. [Expert consensus on chloroquine phosphate for the treatment of novel coronavirus pneumonia] Zhonghua Jiehe He Huxi Zazhi. 2020;43:185–188. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-0939.2020.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Indian Council of Medical Research. Advisory on the use of Hydroxychloroquine as prophylaxis for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Minist Heal Fam Welfare, Gov India n.d. https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/AdvisoryontheuseofHydroxychloroquinasprophylaxisforSARSCoV2infection.pdf (accessed April 28, 2020).

- 21.Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update FDA revokes emergency use authorization for chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine | FDA n.d. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-revokes-emergency-use-authorization-chloroquine-and accessed June 22, 2020.

- 22.Gao J., Tian Z., Yang X. Breakthrough: chloroquine phosphate has shown apparent efficacy in treatment of COVID-19 associated pneumonia in clinical studies. Biosci Trends. 2020;14:72–73. doi: 10.5582/bst.2020.01047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen J., Liu D., Liu L., Al E. A pilot study of hydroxychloroquine in treatment of patients with common coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) J Zhejiang Univ. 2020;49:1–10. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2020.03.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Z., Hu J., Zhang Z., Jiang S., Han S., Yan D. Efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in patients with COVID-19: results of a randomized clinical trial. MedRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.22.20040758. 2020.03.22.20040758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang M, Tang T, Pang P, Li M, Ma R, Lu J, et al. Treating COVID-19 with Chloroquine. J Mol Cell Biol n.d. 10.1093/JMCB/MJAA014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Tang W., Cao Z., Han M., Wang Z., Chen J., Sun W. Hydroxychloroquine in patients with mainly mild to moderate coronavirus disease 2019: open label, randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2020;369:m1849. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horby P., Mafham M., Linsell L., Bell J.L., Staplin N., Emberson J.R. Effect of Hydroxychloroquine in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19: preliminary results from a multi-centre, randomized, controlled trial. MedRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.07.15.20151852. 2020.07.15.20151852. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cavalcanti A.B., Zampieri F.G., Rosa R.G., Azevedo L.C.P., Veiga V.C., Avezum A. Hydroxychloroquine with or without azithromycin in mild-to-moderate covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2019014. NEJMoa2019014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitjà O, Corbacho-Monné MB, Ubals MB, Tebe C, Peñafiel J, Tobias A, et al. Hydroxychloroquine for early treatment of adults with mild covid-19: a randomized-controlled trial. n.d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Sarma P., Kaur H., Kumar H., Mahendru D., Avti P., Bhattacharyya A. Virological and clinical cure in COVID-19 patients treated with hydroxychloroquine: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol. 2020;92:776–785. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gautret P., Lagier J.-C.J., Parola P., Al E., Hoang V.T., Meddeb L. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020:105949. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 32.Singh A.K., Singh A., Singh R., Misra A. Hydroxychloroquine in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2020;14:589–596. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gautret P., Lagier J.-C., Parola P., Hoang V.T., Meddeb L., Sevestre J. Clinical and microbiological effect of a combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in 80 COVID-19 patients with at least a six-day follow up: a pilot observational study. Trav Med Infect Dis. 2020:101663. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Molina J.M., Delaugerre C., Le Goff J., Mela-Lima B., Ponscarme D., Goldwirt L. No evidence of rapid antiviral clearance or clinical benefit with the combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in patients with severe COVID-19 infection. Med Maladies Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2020.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Million M., Lagier J.-C., Gautret P., Colson P., Fournier P.-E., Amrane S. Full-length title: early treatment of COVID-19 patients with hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin: a retrospective analysis of 1061 cases in Marseille, France. Trav Med Infect Dis. 2020:101738. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Geleris J., Sun Y., Platt J., Zucker J., Baldwin M., Hripcsak G. Observational study of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2012410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mahévas M., Tran V.-T., Roumier M., Chabrol A., Paule R., Guillaud C. Clinical efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in patients with covid-19 pneumonia who require oxygen: observational comparative study using routine care data. BMJ. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1844. m1844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu B., Li C., Chen P., Zhou N., Wang L., Li J. Sci China life sci. 2020. Low dose of hydroxychloroquine reduces fatality of critically ill patients with COVID-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Borba M.G.S., Val F.F.A., Sampaio V.S., Alexandre M.A.A., Melo G.C., Brito M. Effect of high vs low doses of chloroquine diphosphate as adjunctive therapy for patients hospitalized with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mo S., Oi A. Improving the efficacy of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine against SARS-CoV-2 may require zinc additives - a better synergy for future COVID-19 clinical trials. Infezioni Med Le. 2020;28 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chorin E., Dai M., Shulman E., Wadhwani L., Bar-Cohen R., Barbhaiya C. The QT interval in patients with COVID-19 treated with hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin. Nat Med. 2020:1–2. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0888-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Falcão M.B., Pamplona de Góes Cavalcanti L., Filgueiras Filho N.M., Antunes de Brito C.A. Case report: hepatotoxicity associated with the use of hydroxychloroquine in a patient with novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020 doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Giudicessi J.R., Noseworthy P.A., Friedman P.A., Ackerman M.J. Urgent guidance for navigating and circumventing the QTc-prolonging and torsadogenic potential of possible pharmacotherapies for coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) Mayo Clin Proc. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Singh A.K., Singh A., Shaikh A., Singh R., Misra A. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19 with or without diabetes: a systematic search and a narrative review with a special reference to India and other developing countries. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2020;14:241–246. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salunke Abhijeet Ashok. A proposed ABCD scoring system for patient’s self assessment and at emergency department with symptoms of COVID-19, Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2020;14(5):1495–1501. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.07.053. ISSN 1871-4021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]