Abstract

Purpose

Health systems have increased telemedicine use during the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak to limit in-person contact. We used time-driven activity-based costing to evaluate the change in resource use associated with transitioning to telemedicine in a radiation oncology department.

Methods and Materials

Using a patient undergoing 28-fraction treatment as an example, process maps for traditional in-person and telemedicine-based workflows consisting of discrete steps were created. Physicians/physicists/dosimetrists and nurses were assumed to work remotely 3 days and 1 day per week, respectively. Mapping was informed by interviews and surveys of personnel, with cost estimates obtained from the department’s financial officer.

Results

Transitioning to telemedicine reduced provider costs by $586 compared with traditional workflow: $47 at consultation, $280 during treatment planning, $237 during on-treatment visits, and $22 during the follow-up visit. Overall, cost savings were $347 for space/equipment and $239 for personnel. From an employee perspective, the total amount saved each year by not commuting was $36,718 for physicians (7243 minutes), $19,380 for physicists (7243 minutes), $17,286 for dosimetrists (7210 minutes), and $5599 for nurses (2249 minutes). Patients saved $170 per treatment course.

Conclusions

A modified workflow incorporating telemedicine visits and work-from-home capability conferred savings to a department as well as significant time and costs to health care workers and patients alike.

Introduction

Since its initial detection, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has spread rapidly worldwide.1 Given the imperative to limit in-person contact, health systems have increased the use of telemedicine to reduce viral transmission,2 supported in part by sweeping changes in regulation and reimbursement policies.3 , 4 However, as the pandemic evolves, it remains unclear what changes to clinic processes should be sustained, especially in regard to telemedicine efforts.

Time-driven activity-based costing (TDABC) is a tool for cost accounting, in which the continuum of care is mapped, with time spent and resource use (ie, personnel, space, equipment, and materials) associated with each step precisely quantified.5 In this study, using a patient undergoing a 28-fraction treatment course as an example, we used TDABC to evaluate the overall change in resource use associated with transitioning to telemedicine in a radiation oncology department. TDABC was conducted from the departmental perspective with additional benefits to patients and employees calculated separately.

Methods and Materials

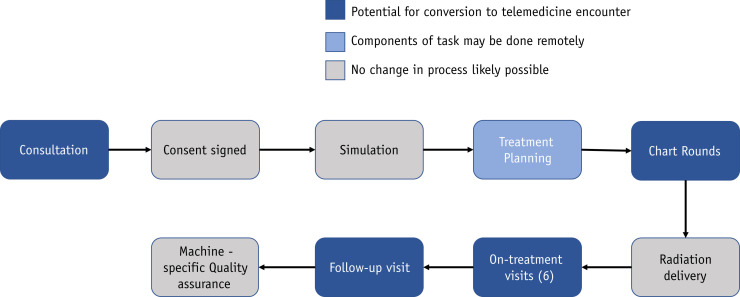

In response to the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak, faculty and staff in a radiation oncology department at a large academic institution were encouraged to work from home, with physicians, physicists, and dosimetrists working remotely 3 days per week and nurses working remotely 1 day per week. The majority of new patient consultations, follow-up visits, and on-treatment visits (OTVs) were converted from in-person visits to telemedicine encounters. To inform TDABC analysis, process maps were created for traditional in-person and telemedicine-based workflow processes to delineate differential care pathways and resource use (Fig. 1 ). Maps consisting of discrete steps were created for each phase of the care cycle, with mapping informed by interviews and surveys of personnel.

Fig. 1.

Overview of care delivery process map. Colors represent the degree to which a step may be modified with telemedicine.

Equipment costs, space capacity, materials costs, and personnel costs were obtained from the department’s financial officer. The capacity cost rate of each resource was determined by dividing the total annual cost for each personnel or piece of equipment by the practical capacity of the resource. Personnel costs included salary, bonus, and fringe benefits but did not incorporate an employee’s commute; therefore, in the telemedicine model, employee time saved by not commuting to work was assumed to solely benefit the employee. For processes completed remotely, the space was defined as a personal office with no associated space costs to the department; however, the equipment costs associated with purchase and installation of remote workstations were included in the employee’s personal office. Given a fixed-fee contract already set in place with the videoconferencing vendor, additional use of telemedicine services through this platform were not included in the analysis.

Costs of personal protective equipment and SARS-CoV-2 testing, specific to a global pandemic, were additionally excluded from this analysis, which focused on generally comparing resources used between traditional versus telehealth workflows.

Results

Several steps in the traditional workflow were no longer necessary in a telemedicine workflow. During consultation and follow-up, telemedicine workflow no longer required a front office staff member to physically check in a patient (10 and 3 minutes during consultation and follow-up, respectively) or a nurse to print an after-visit summary (2 minutes). During each OTV, telemedicine workflow no longer required a medical assistant to obtain vitals/weight (4 minutes) or a nurse on the last visit to print an after-visit summary (2 minutes).

Telemedicine workflow facilitated several steps to be performed remotely. For consultation and follow-up visits, patient interactions with nurses and physicians took place via telemedicine. OTV encounters consisted of a telemedicine visit with the physician alone unless the patient was symptomatic or seen at physician request (∼20%), in which both nurse and physician saw the patient in person. During treatment planning, except for the patient’s plan being physically delivered to the phantom, all steps were converted to a remote workflow.

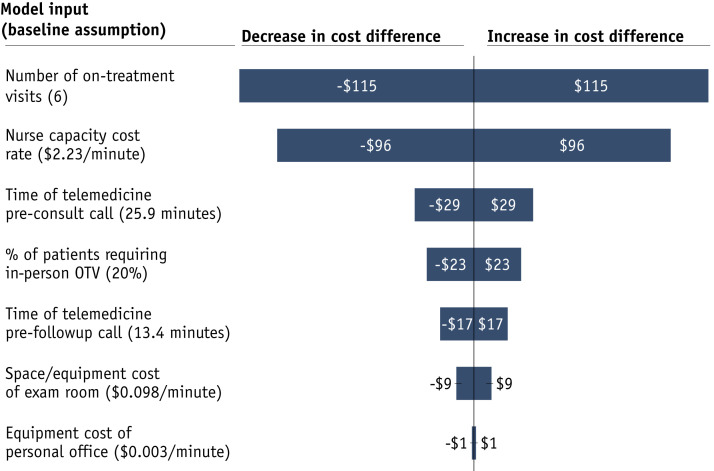

In a survey of 10 nurses, average time spent in traditional in-person encounters during consultation, OTV, and follow-up was 25.2, 16.2, and 13.9 minutes, respectively. In the telemedicine setting, average time spent during consultation and follow-up was 25.9 and 10.7 minutes, respectively. For each patient undergoing 28-fraction treatment, 6 OTVs, and 1 follow-up visit, transitioning to telemedicine workflow reduced provider costs by $586 compared with the traditional workflow (Table 1 )—comprising space/equipment ($347) and personnel ($239). The effect of modifying key model inputs, such as number of OTVs and cost of nursing time, on savings from telehealth workflow is shown in Figure 2 .

Table 1.

Difference in cost between telemedicine and traditional workflow

| Map | Process step | Personnel | Space + equipment | Materials | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | New patient | –$12 | –$36 | $0 | –$47 |

| 2 | Simulation | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| 3 | Treatment planning | –$10 | –$270 | $0 | –$280 |

| 4 | Treatment (total) | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| 5 | On-treatment visit (total) | –$203 | –$34 | $0 | –$237 |

| 6 | Follow-up visit (total) | –$14 | –$7 | $0 | –$22 |

| 7 | Machine-specific QA | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Total | –$239 | –$347 | $0 | –$586 |

Negative numbers represent savings with telemedicine.

Abbreviation: QA = quality assurance.

Fig. 2.

Sensitivity analysis reflecting change in annual savings to provider with modification of key model inputs (±50%). Abbreviation: OTV = on-treatment visit.

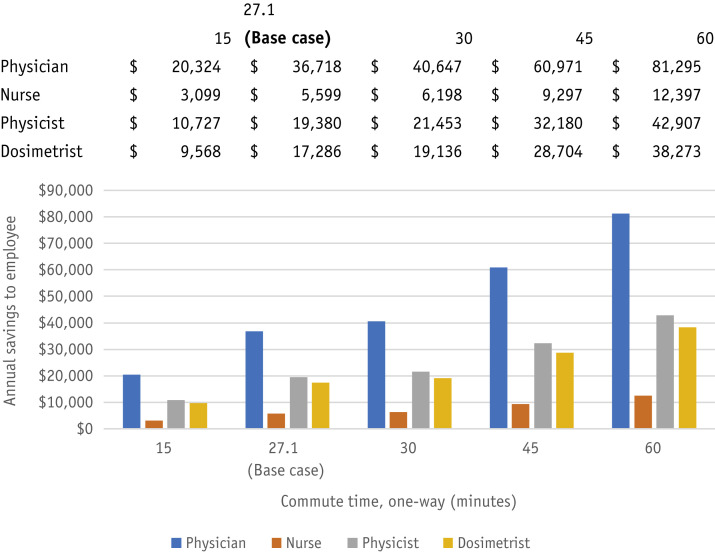

From an employee perspective, assuming a 1-way commute of 27.1 minutes6 to travel approximately 15 miles, the ability to work remotely for physicians/physicists/dosimetrists (3 days per week) and nurses (1 day per week) saves 7243, 7243, 7210, and 2249 minutes per year for each physician, physicist, dosimetrist, and nurse, respectively. Considering each personnel type’s capacity cost rate and a standard mileage allowance for vehicle wear/tear ($0.575/mile),7 the annual amount saved was $36,718 per physician, $19,380 per physicist, $17,286 per dosimetrist, and $5599 per nurse (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Savings to employee by working from home (3 d/wk for physicians, physicists, and dosimetrists; 1 d/wk for nurses) as a function of commute time.

From a patient’s perspective—including 2 fewer roundtrips to the department (given telemedicine consultation visit and follow-up visits)—232 minutes are saved throughout the entire course of treatment. Accounting for vehicle wear/tear,7 estimated parking expense ($10 per day), and lost wages ($30.01 per hour),8 the telemedicine workflow saves patients on average $170 per course of treatment.

Discussion

Because simulation and treatment require in-person interaction, most opportunities within radiation oncology to adapt to SARS-CoV-2 involve transitioning patient visits to telemedicine encounters and enabling work-from-home solutions for employees. Additional processes that have facilitated this change include increased use of patient portals to communicate with patients pre-encounter, training front office staff to educate patients on how to set up telemedicine on their devices, and replacing a paper-based survey on patient symptoms with electronic surveys.

Beyond the notable economic benefits generated from modified workflow, telemedicine touts benefits not explicitly included in this analysis. For employees, time saved may be reinvested in research or used for improved well-being. Diminished waiting times associated with telemedicine visits are likely to improve provider and patient satisfaction alike.9 Allowing personnel to work remotely is expected to reduce the risk of infection for health care workers.2 Additionally, this revised telemedicine workflow allows for a more flexible work environment, especially relevant to those caring for others at home.

Potential downsides of transitioning clinic visits to telemedicine encounters include being able to perform in-person clinical assessments less frequently and have less familiar physicians assessing patients in acute settings. This, however, may be mitigated by carefully deciding which patients during treatment are symptomatic enough to warrant face-to-face evaluation. Due to a telemedicine encounter’s dependence on Internet connection, there are technical and privacy risks that must be addressed. Lastly, efforts to ensure equity for vulnerable populations are required to ensure widespread implementation of telemedicine does not worsen health disparities.10

This study has several limitations that warrant consideration. First, this study is based on processes/estimates of a single institution; consideration must be given to each institution’s specific personnel, processes, and cost structure when incorporating this analysis. Second, given limited long-term outcome data surrounding telemedicine use in radiation oncology, this study solely assesses resource use and not the effectiveness of such an approach.

Conclusion

Compared with a traditional workflow involving in-person visits, a modified workflow incorporating telemedicine visits and work-from-home capability confers provider savings of $586/patient, with number of OTVs and cost of nursing time as the most important model inputs in the specific amount saved. Additionally, this approach confers significant time/value saved by health care workers and patients, all while lowering the risk of infectious transmission in the clinic.

Footnotes

Disclosures: A.U.K. reports honoraria and consulting fees from Varian, honoraria from ViewRay, serving on the Janssen advisory board, and consulting fees from Intelligent Automation Inc. M.L.S. reports honoraria from ViewRay and consulting fees from Vision RT. A.C.R. reports consulting fees from Intelligent Automation Inc, honoraria from Varian Medical System Inc, consulting fees/honoraria/in-kind donations from Clarity PSO/RO-ILS RO-HAC, honoraria from California Technology Assessment Forum, consulting fees and honoraria from Rectal Cancer Panel Member, grants from ViewRay Inc, and serving on the NCCN EHR Advisory Group.

Research data are stored in an institutional repository and will be shared upon request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 Available at:

- 2.Hollander J.E., Carr B.G. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1679–1681. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2003539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Trump administration issues second round of sweeping changes to support U.S. healthcare system during COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/trump-administration-issues-second-round-sweeping-changes-support-us-healthcare-system-during-covid Available at:

- 4.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Additional background: Sweeping regulatory changes to help U.S. healthcare system address COVID-19 patient surge. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/additional-backgroundsweeping-regulatory-changes-help-us-healthcare-system-address-covid-19-patient Available at:

- 5.Kaplan R.S., Anderson S.R. Time-driven activity-based costing. Harv Bus Rev. 2004;82:131–138. 150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.United States Census Bureau Average travel time to work in the United States by metro area. https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/interactive/work-travel-time.html Available at:

- 7.Internal Revenue Service IRS issues standard mileage rates for 2020. https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/irs-issues-standard-mileage-rates-for-2020 Available at:

- 8.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Average hourly and weekly earnings of all employees on private nonfarm payrolls by industry sector, seasonally adjusted. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.t19.htm Available at:

- 9.Polinski J.M., Barker T., Gagliano N. Patients’ satisfaction with and preference for telehealth visits. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:269–275. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3489-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nouri S., Khoong E.C., Lyles C.R. Addressing equity in telemedicine for chronic disease management during the Covid-19 pandemic. NEJM Catalyst. May 4, 2020 [Google Scholar]