Highlights

-

•

Exchange rate appreciations squeeze profit margins and reduce export volumes.

-

•

Pass-through results show differentiated goods’ foreign currency prices increase more.

-

•

Differentiated goods producers’ stock prices are less exposed to appreciations.

-

•

Producing knowledge-intensive goods can thus help firms weather appreciations.

Keywords: Differentiated products, Exchange rate pass-through, Exchange rate elasticities

Abstract

Japan has experienced several appreciation episodes. These appreciations may squeeze profit margins and lower export volumes. This paper investigates whether firms can weather appreciation periods by producing differentiated rather than commoditized products. To do this it investigates different sectors within the Japanese transportation equipment industry. Results from estimating pricing-to-market (PTM) coefficients indicate that firms producing differentiated products can pass-through more of exchange rate appreciations into higher foreign currency prices and thus better preserve their profit margins. Results from estimating trade elasticities are consistent with the PTM results and indicate that the automobile industry has exported much less than predicted after the yen depreciated in 2012. Finally, estimates of the stock market exposure across sectors indicates that the profitability of firms producing differentiated products is less exposed to appreciations. Producing differentiated, knowledge-intensive goods can thus help firms to survive endaka periods.

1. Introduction

The Japanese yen has appreciated from 360 yen per dollar in 1971 to 107 yen per dollar in May 2020. There have also been episodes of rapid appreciation. For instance, during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and the Eurozone Crisis, capital inflows and other factors caused the Japanese yen to appreciate by more than 45 percent against the dollar between June 2007 and September 2012. These appreciations can squeeze profit margins if exporters must lower Japanese yen export prices to remain competitive. They may also reduce the volume of exports. How can Japanese firms weather large appreciations? How are they affected if exchange rates subsequently depreciate?

Producing differentiated products may help. Producers of commoditized products can face intense price competition, forcing firms to slash domestic currency export prices and compress profit margins when the exchange rate appreciates. Producers of differentiated products may not only be able to reduce domestic currency prices less during appreciations, they may be able to raise these prices more (price-to-market more) when the exchange rate depreciates (see Chen and Juvenal, 2016).

Ito et al. (2018) reported that, unlike for homogeneous goods, firms exporting differentiated products and firms having a large share of the global market tend to invoice in the exporter’s currency. They surveyed major Japanese exporters to investigate their invoicing decisions. Using probit estimation, they reported that firms are more likely to invoice in yen when they export through Japanese trading companies (Sogo Shosha), when they conduct arm’s length sales, when they face higher hedging costs, and when their products are more differentiated and they have more market power. There are thus several factors that influence Japanese firms’ invoicing decisions.

The Bank of Japan (BoJ) provides detailed data on the invoice currencies of Japanese exports disaggregated by industry. For the Japanese transportation equipment industry, the share of yen invoicing is informative about the degree of product differentiation and market power. These data are presented in column (6) of Table 1 . For passenger cars, only 8 percent of exports over the 2000–2015 period are invoiced in yen. Japanese automakers reported to Ito et al. (2018) that the market for cars in key locations such as the U.S. is so competitive that they must invoice in the importer’s currencies.1 For small cars, which face more competition than regular cars, only 4 percent of exports are invoiced in yen. For commercial vehicles such as buses and trucks, which are more complex than passenger cars, the share of yen invoicing is higher than for cars. Also for engines and auto parts, which Nguyen and Sato (2019) observed are more differentiated than passenger cars, the share of yen invoicing is 0.54. At the other extreme is bicycle parts, with 91 percent of exports invoiced in yen. Lewis and Morizono (2016) observed that Japan’s Shimano Corporation produces 75 percent of the world’s supply of bicycle brakes and gears. Shimano thus exercises market power.

Table 1.

Long run pricing-to-market coefficients for Japanese transportation equipment industries.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sector | Long Run Pricing-to- Market Coefficient | Long Run Pricing-to- Market Coefficient in Exchange Rate Depreciation Periods | Long Run Pricing- to- Market Coefficient in Exchange Rate Appreciation Periods | Probability Value of Null Hypothesis that the PTM Coefficients Are Equal in Appreciation and Depreciation Period | Share of Yen-invoicing | Share of Yen-invoicing During Yen Depreci-ation Periods |

Share of Yen-invoicing During Yen Appreci-ation Periods |

| Small cars | 0.994*** (0.108) | 1.05*** (0.088) | 0.638*** (0.122) | 0.002 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.01 |

| Standard cars | 0.887*** (0.211) | 0.996*** (0.256) | 0.696*** (0.197) | 0.336 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.07 |

| Motorcycles | 0.516*** (0.150) | 0.594*** (0.129) | 0.217 (0.189) | 0.064 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.17 |

| Standard trucks | 0.394*** (0.029) | 0.410*** (0.049) | 0.393*** (0.056) | 0.832 | 0.36 | 0.42 | 0.27 |

| Marine engines | 0.395*** (0.030) | 0.394*** (0.039) | 0.440*** (0.080) | 0.492 | 0.37 | 0.36 | 0.39 |

| Small truck | 0.454*** (0.072) | 0.439*** (0.082) | 0.454*** (0.106) | 0.904 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.38 |

| Auto parts | 0.330*** (0.066) | 0.379*** (0.042) | 0.072 (0.081) | 0.000 | 0.54 | 0.53 | .56 |

| Bus | 0.219*** (0.041) | 0.188*** (0.036) | 0.290*** (0.054) | 0.000 | 0.64 | .68 | .58 |

| Bicycle parts | 0.022 (0.046) | −0.013 (0.056) | 0.096** (0.046) | 0.03 | 0.91 | .91 | .92 |

Note: The long run pricing-to-market (PTM) coefficient in column (2) comes from an autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) regression of the change in the yen export price on the lagged value of the yen export price, the lagged value of the yen/dollar exchange rate, the lagged value of the producer price index, the lagged value of industrial production in OECD countries, and lagged values of the first differences of these variables. The long run PTM coefficients in columns (3) and (4) come from a nonlinear ARDL regression of the change in the yen export price on the lagged value of the yen export price, the lagged value of the producer price index, the lagged value of industrial production in OECD countries, the sum of the change in the yen/dollar rate for all periods up to t-1 when the actual exchange rate was weaker than the value predicted by the Tankan survey, the sum of the change in the yen/dollar rate for all periods up to t-1 when the actual exchange rate was weaker than the value predicted by the Tankan survey, and lagged values of the first differences of all of these variables. Monthly data over the 2000M01-2018M12 period are used. The share of yen invoicing in column (6) represents the share over the January 2000 - December 2015 period and comes from Ito et al. (2016b) who obtained them from the Bank of Japan. The share of yen invoicing during depreciation periods in column (7) is a weighted average of the values from Ito et al where the weights depend on the fraction of time the yen is in a depreciation period. Yen depreciation periods are times when the yen is weaker than forecasted by the BoJ Tankan survey. The shares during appreciation periods in column (8) are calculated in an analogous manner. Heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation consistent standard errors are in parentheses.

*** (**) Denotes significance at the 1 % (5 %) levels.

Source: Bank of Japan, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis FRED database, Ito et al. (2016b), and calculations by the author.

Fig. 1 a shows the relationship between yen export prices and yen costs for Japanese passenger cars and Fig. 1b shows this relationship for Japanese bicycle parts. Fig. 1a shows that yen prices for cars fell logarithmically by 40 percent relative to yen costs (represented by the producer price index for passenger cars) after the yen began appreciating in June 2007. Fig. 1b on the other hand shows that there was little change in yen export prices for bicycle parts relative to yen costs (represented by the producer price index for bicycle parts) during the yen appreciation period from June 2007 to September 2012.

Fig. 1.

(a) The Relationship between Yen Export Prices, Yen Costs, and Exchange Rates for Japanese Passenger Cars.

Source: Bank of Japan and Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis FRED database.

Note: Yen costs are represented by the producer price index for passenger cars.

(b) The Relationship between Yen Export Prices, Yen Costs, and Exchange Rates for Japanese Bicycle Parts.

Source: Bank of Japan and Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis FRED database.

Note: Yen costs are represented by the producer price index for bicycle parts.

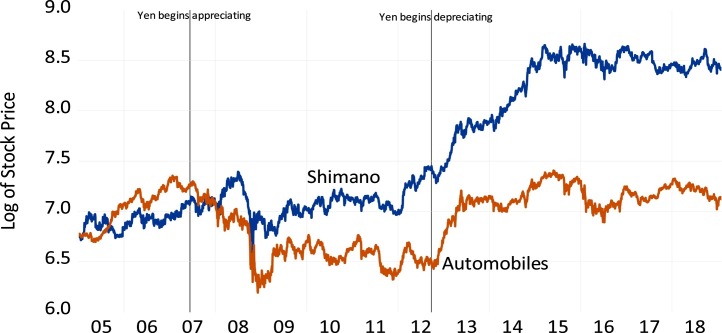

The fact that yen export prices fell so much relative to yen costs for the automobile industry but not for the bicycle parts industry suggests that the profitability of the automobile industry suffered more during the strong yen period from June 2007 to September 2012 than the bicycle parts industry did. Stock prices provide one indicator of profitability, since standard finance models predict that they equal the expected present value of future cash flows. Fig. 2 plots stock prices for the Japanese automobile sector and for Shimano Corporation. It shows that stock prices for automobile producers fell almost 90 percent during the strong yen period and only began recovering in September 2012 as the yen depreciated. On the other hand, stock prices for Shimano increased almost 30 percent during the endaka period.

Fig. 2.

Stock Prices for Japanese Automobile Companies and for Shimano Corporation.

Source: Datastream database.

Note: Shimano Corporation is the leading producer of bicycle parts.

This paper investigates whether Japanese transportation industry exports that are invoiced in yen – where yen invoicing for the transportation industry is informative of whether the product is more differentiated or commands a larger share of the global market – are less exposed to exchange rate changes. Focusing on the transportation industry rather than on all industries reduces variation across other dimensions that might affect pricing such as the skills and knowhow required to produce a certain good.2 The paper examines whether long run exchange rate pass-through is larger (and long run pricing-to-market, PTM, smaller) for goods that are invoiced in yen. The results indicate that, the more firms invoice a product in yen, the more they pass-through exchange rate appreciations into foreign prices. This suggests that firms producing differentiated products or firms possessing more of the market are better able to maintain profit margins in the face of yen appreciations.

The paper then examines export elasticities for the transportation industry. Sectors such as auto parts and motorcycles that pass-through large shares of yen appreciations also have low exchange rate elasticities. The finding that exports in these sectors are not sensitive to exchange rates implies that firms producing these goods have more freedom to raise foreign currency prices when the exchange rate appreciates.

Finally the paper investigates the exposure of Japanese stocks in the transportation industry to exchange rates. Finance models hold that stock prices are the expected present value of future cash flows, so they should reflect profitability. The results indicate that the firms that pass-through more of their exchange rate changes to export prices such as makers of commercial vehicles, trucks, and bicycle parts are also less exposed to exchange rate changes than firms that price-to-market.

Nguyen and Sato (2019) employed a nonlinear autoregressive distributed lag model to investigate the PTM behavior of Japanese exporters. They specified yen appreciation and yen depreciation periods using predicted exchange rates from the BoJ Tankan survey. They reported almost complete PTM behavior in the short run over the 1997–2018 period. In addition, they found high but incomplete PTM in the long run for most industries during yen appreciation periods. They also found high PTM in the long run for competitive industries such as general machinery and transport equipment and lower PTM for less competitive industries such as textiles and chemicals during yen appreciation periods.

Ito et al. (2016a) investigated the exchange rate exposure of Japanese firms and the relationship between exposure and exchange rate risk management practices. They regressed monthly stock returns for 227 companies over the January 2005 to December 2009 period on the percentage change in the yen/dollar exchange rate and the nominal effective exchange rate. In one specification they also included the return on the overall Japanese stock market portfolio as a second independent variable. They found that firms producing transportation equipment, precision instruments, electrical machinery, and general machinery are highly exposed to exchange rate appreciations, indicating that these firms face intense competition from abroad. They also reported that firms with a higher ratio of foreign sales and firms with less yen invoicing are more exposed to appreciations. They did not find a statistically significant relationship between a firm’s exchange rate exposure and its degree of exchange rate pass-through.

Iwaisako and Nakata (2017) used monthly vector autoregressions (VARs) over the January 1977 to September 2014 period to investigate how exchange rates, demand in the rest of the world, and other factors affect Japanese aggregate export. They included the real effective exchange rate, the growth of aggregate exports, two measures of global demand, crude oil prices, and world oil production growth in the VARs. They reported evidence from impulse response functions indicating that a yen appreciation reduces exports. They also reported evidence from variance decompositions indicating that exchange rate shocks explain less of the variance of export growth after 2000. They found that falls in global demand mattered much more than appreciating exchange rates for explaining decreases in exports following the 2008 Lehmann Brothers Crisis. Iwaisako and Nakata (2015) reported that even though the yen had less of an impact on export volumes after 2000, they substantially impacted the profitability of Japanese firms.

Shioji and Uchino (2012) investigated how external shocks affect the Japanese automobile industry. They estimated a monthly vector autoregression (VAR) over the 1980–2008 period. Their VAR included oil prices, the Japanese nominal effective exchange rate, measures of demand in the U.S. and the EU, real Japanese automobile exports, Japanese auto production, and industrial production. They assumed a recursive ordering to the variables and employed a Cholesky decomposition. They reported that over time positive shocks to U.S. demand increase Japanese automobile exports and positive exchange rate shocks (yen appreciations) reduce automobile exports. They also found that their model could not explain the huge fall in automobile exports during the GFC. They thus estimated another model using panel data on automobile production, sales, and inventories that are available by company and type of car. They reported a non-linear response, with Japanese automakers cutting production more quickly in response to accumulated inventories when output is falling rapidly than when output is falling slowly or rising.

Sato et al. (2013) examined how Japanese transport equipment exports responded to rest of the world output and to real exchange rates. They measured rest of the world output as a weighted average of trading partners’ industrial production indices and exchange rates as industry-specific real effective exchange rates for the transport equipment industry. They employed a monthly VAR over the 2001–2013 period and assumed that industrial production in the rest of the world is strictly exogenous and that the exchange rate is not contemporaneously affected by shocks to exports. They reported that a positive shock to world output increases Japanese transport equipment exports in subsequent months and that a positive exchange rate shock (yen appreciation) decreases transport equipment exports. They did not report the exact magnitude of the effect of exchange rate changes on transport equipment exports.

This paper adds to the literature by using disaggregated data for the transportation industry. This allows us to investigate how similar products with different characteristics are affected by exchange rate changes.

The next section investigates the long run pass-through of exchange rates into export prices for goods in the transportation industry. Section 3 estimates exchange rate elasticities for these goods. Section 4 examines their exchange rate exposures. Section 5 concludes.

2. Long run pass-through of exchange rates into export prices

2.1. Data and methodology

Campa and Goldberg (2005) examined the microeconomic foundations of exporters’ pricing behavior. They reported that export prices are a function of exporters’ costs and of demand conditions in importing countries. They modelled export prices as the product of marginal costs and of firms’ markups. Marginal cost depends on the cost of labor and other inputs and on demand in the importing countries. The markup is a function of industry-specific factors and of macroeconomic factors such as the exchange rate and of the prices of import-competing goods in the importing countries.

Ceglowski (2010) used this framework to study the short run pass-through from exchange rates to export prices in Japan. She modeled the first difference of Japanese export prices as a function of current and lagged values of the first difference of foreign prices, domestic costs, economic activity in the destination markets and exchange rates. She employed industry-specific yen-denominated export prices from the BoJ. She obtained the foreign price variable by multiplying the inverse of the BoJ real effective exchange rate series by the product of the nominal effective exchange rate and the Japanese corporate goods price index. She measured economic activity in destination markets by industrial production in industrialized countries. She calculated the exchange rate as the ratio in each industry of the yen-denominated export price to the contract-currency export price

Since this paper uses currency invoicing as an indicator of export competitiveness, it investigates long run exchange rate pass-through. As Ito et al. (2018) observed, over the medium and longer exporters can change prices and thus the choice of invoice currency has less influence on exchange rate pass-through.

Nguyen and Sato (2019) investigated long run pass-through from exchange rates to export prices in Japan. They first employed an autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) model:

| (1) |

where is the yen export price, is the exchange rate, represents production costs, and represents economic activity in the importing markets. The long run PTM coefficient is then given by β2/β1. Bounds tests can be used to test the null hypothesis of no cointegration against the alternative of cointegration.

Nguyen and Sato (2019) also investigated whether exporters’ pricing behavior differed during yen appreciation and yen depreciation periods. They characterized appreciation periods as times when the yen was stronger than forecasted by the BoJ Tankan survey of businesses and depreciations as times when the yen was weaker than forecasted. They then estimated a nonlinear autoregressive distributed lag (NARDL) model:

| (2) |

where is the partial sum of exchange rate changes for depreciation periods, is the partial sum of exchange rate changes during appreciation periods, and the other variables are defined above. The long run PTM coefficient during yen depreciation periods is then given by β2/β1 and the coefficient during yen appreciation periods by β3/β1. The null hypothesis that the PTM coefficient is symmetric between depreciation and appreciation periods can be tested by using Wald tests of the null hypothesis that β2/β1 = β3/β1.

This paper estimates Eqs. (1) and (2) for goods in the transportation industry. To do this it employs data on export prices in yen () and the producer price index in yen () for these goods that come from the BoJ. It also employs data on the nominal yen/dollar exchange rate () that come from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis FRED database. Fig. 1 suggests that there is a tight relationship between the yen/dollar exchange rate and export prices for passenger cars. Finally it uses data on industrial production in OECD countries () that come from the OECD.3

In calculating , the change in the exchange rate is summed for all periods up to t-1 when the actual exchange rate was weaker than the value predicted by the Tankan survey. In calculating , the change in the exchange rate is summed for all period up to t-1 when the actual exchange rate was stronger than the value predicted by the Tankan survey.

Data for the following goods are obtained: bicycle parts, buses, marine engines, motor vehicle parts, motorcycles, small cars, small trucks, standard cars, and standard trucks. The data extend from January 2000 to December 2018.

In almost every case augmented Dickey-Fuller tests indicate that the variables are integrated of order one (I(1)) and Bounds F-tests indicate that the variables are cointegrated. Exploratory analysis using the Schwarz Information Criterion (SIC) point to short lag lengths when estimating Eqs. (1) and (2). The lag lengths in Eqs. (1) and (2) are thus set equal to two.

2.2. Results

Column (2) of Table 1 presents the PTM coefficient from Eq. (1), column (3) the PTM coefficient from Eq. (2) during yen depreciation times, and column (4) the PTM coefficient from Eq. (2) during yen appreciation times. Column (5) presents the probability value from Wald tests of the null hypothesis that the long run PTM coefficients are symmetric across exchange rate depreciation and appreciation periods. Column (6) lists the share of yen invoicing for each good, column (7) lists the share of yen invoicing during depreciation periods and column (8) lists the share of yen invoicing during appreciation periods.4 The table is ordered from the good with the smallest share of yen invoicing (small cars) to the good with the largest share of yen invoicing (bicycle parts).

Most of the PTM coefficients in columns (2), (3), and (4) are statistically significant. For small cars and standard cars, the PTM coefficients are larger during yen depreciation periods than during yen appreciation periods. For small cars but not for standard cars the difference is statistically significant. Nguyen and Sato (2019) also found that the PTM coefficients for passenger cars (i.e., small cars plus standard cars) are larger during yen depreciation periods, although the difference they reported was not statistically significant. For motor vehicle parts and motorcycles, the PTM coefficients are also smaller during yen appreciation times than during yen depreciation times. The PTM coefficients are close to zero for bicycle parts exports during both depreciation and appreciation periods.

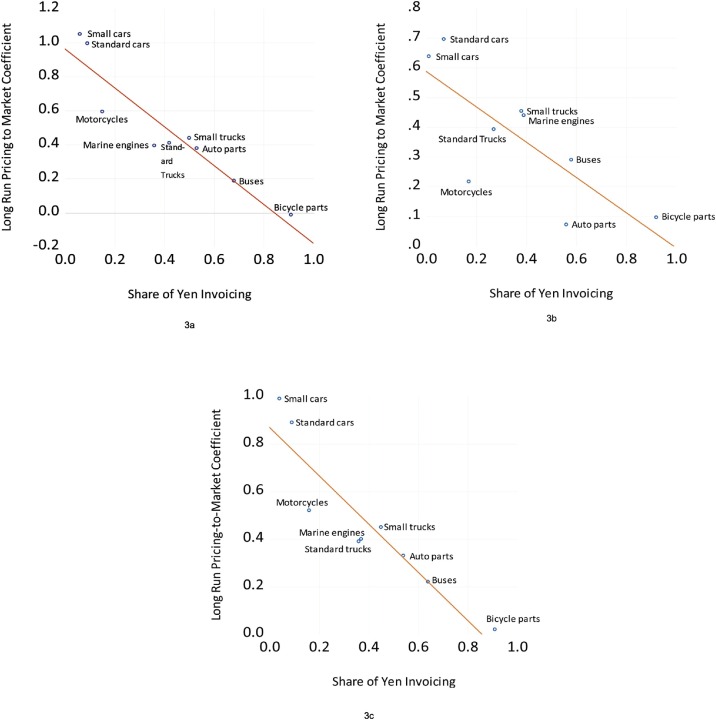

Fig. 3 a plots the relationship between the PTM coefficients and the share of yen invoicing during depreciation periods, Fig. 3b plots the relationship during appreciation periods, and Fig. 3c plots the relationship over the whole sample period. Fig. 3a shows a tight relationship between these two variables, with the t-statistic for the slope coefficient exceeding 7.5 in absolute value. Fig. 3b also shows a tight relationship between the two variables, with the t-statistic for the slope coefficient exceeding 5. Motorcycles and motor vehicle parts are outliers, with producers of these goods lowering Japanese export prices only a little in response to yen appreciations. Fig. 3c shows that there is a close relationship between the two variables over the whole sample, with the t-statistic for the slope coefficient is close to 10.

Fig. 3.

(a) The Relationship between the Long Run Pricing-to-market Coefficient and the Share of Yen invoicing during Yen Depreciation Episodes.

Source: Bank of Japan, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis FRED database, and calculations by the author.

Note: The long run pricing-to-market coefficient comes from a nonlinear autoregressive distributed lag regression of the change in the yen export price on the lagged value of the yen export price, the lagged value of the producer price index, the lagged value of industrial production in OECD countries, the sum of the change in the yen/dollar rate for all periods up to t-1 when the actual exchange rate was weaker than the value predicted by the Tankan survey, the sum of the change in the yen/dollar rate for all periods up to t-1 when the actual exchange rate was weaker than the value predicted by the Tankan survey, and lagged values of the first differences of all of these variables.

(b) The Relationship between the Long Run Pricing-to-market Coefficient and the Share of Yen Invoicing during Yen Appreciation Episodes.

Source: Bank of Japan, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis FRED database, and calculations by the author.

Note: The long run pricing-to-market coefficient comes from a nonlinear autoregressive distributed lag regression of the change in the yen export price on the lagged value of the yen export price, the lagged value of the producer price index, the lagged value of industrial production in OECD countries, the sum of the change in the yen/dollar rate for all periods up to t-1 when the actual exchange rate was weaker than the value predicted by the Tankan survey, the sum of the change in the yen/dollar rate for all periods up to t-1 when the actual exchange rate was weaker than the value predicted by the Tankan survey, and lagged values of the first differences of all of these variables.

(c) The Relationship between the Long Run Pricing-to-market Coefficient and the Share of Yen Invoicing.

Source: Bank of Japan, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis FRED database, Japanese Ministry of Finance, and calculations by the author.

Note: The long run pricing-to-market coefficient comes from an autoregressive distributed lag regression of the change in the yen export price on the lagged value of the yen export price, the lagged value of the yen/dollar exchange rate, the lagged value of the producer price index, the lagged value of industrial production in OECD countries, and lagged values of the first differences of all of these variables.

The important implication of these results is that producers of more competitive goods, where competitiveness is measured by the share of exports that are invoiced in yen, are better able to keep yen prices constant in the face of volatile exchange rates. The next section investigates exchange rate elasticities for exports in the transportation industry, and sheds light on why PTM coefficients during yen appreciation times are low for motorcycles and motor vehicle parts.

3. Estimating export elasticities

3.1. Data and methodology

In theory export demand should depend on the real exchange rate and real GDP in the importing countries. To investigate the relationship between these variables, this section employs Japan’s exports of cars, motorcycles, commercial vehicles (trucks and buses), and motor vehicle parts. For each of these categories, exports to the 20 leading importers over the 1990–2017 period are employed. These countries are listed in the Appendix. Including many countries over a long period of time provides cross sectional and time series variation in the independent variables. This should lead to more precise estimates of the effects of the real exchange rates and real GDP on exports.

Annual data for each of these categories are obtained from the CEPII-CHELEM database. Since these data are measured in U.S. dollars and since Japan’s exports are imports in places like the U.S., exports are deflated using the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) import price deflator for goods from Japan. As a robustness check, exports are also deflated using yen export prices for each category from the BoJ converted to dollars using the yen/dollar exchange rate. 5 Data on bilateral real exchange rates between Japan and each of the importing countries and real GDP in the importing countries are obtained from the CEPII-CHELEM database.

Panel unit root tests and Kao (1999) residual cointegration tests point in some cases to cointegrating relations among the variables. Dynamic ordinary least squares, a technique for estimating cointegrating relations, is thus employed.

The Mark and Sul (2003) weighted dynamic ordinary least squares (DOLS) estimator is used. The model takes the form:

| (3) |

where represents real exports of good i from Japan to country j, represents the bilateral real exchange rate between Japan and importing country j, and represents real GDP in country j. The real exchange rate is defined such that an increase represents an appreciation of the yen. The number of cross-section specific lags and leads is determined by the Schwarz Information Criterion. These variables are included to asymptotically remove endogeneity and serial correlation. Import country-specific time trends and fixed effects are also included.

3.2. Results

Table 2a present the results with exports deflated using the BLS data. Column (2) presents the exchange rate elasticity and column (3) the GDP elasticity. All of the coefficients are of the expected signs and statistically significant. The results indicate that a 10 percent appreciation of the yen would reduce car exports by 7.5 percent, commercial vehicle exports by 6.5 percent, motorcycle exports by 3.0 percent, and motor vehicle parts exports by 1.7 percent. Table 2b indicates that the results are very similar with exports deflated using the BoJ data.

Table 2a.

Panel DOLS estimates of trade elasticities for Japanese transportation equipment exports to 20 countries (exports deflated using data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sector | Exchange Rate Elasticity | GDP Elasticity | Adjusted R-squared | Standard Error of Regression | Number of Observations |

| Cars | −0.75*** (0.08) | 1.84*** (0.29) | 0.954 | 0.269 | 533 |

| Commercial vehicles | −0.65*** (0.16) | 3.70*** (0.69) | 0.842 | 0.660 | 531 |

| Motorcycles | −0.30** (0.12) | 5.00*** (0.50) | 0.865 | 0.453 | 530 |

| Motor vehicle parts | −0.17** (0.08) | 1.43*** (0.23) | 0.961 | 0.223 | 536 |

Note: The coefficients come from a panel dynamic ordinary least squares regression of Japan’s exports in each sector to the 20 leading importing countries. The right hand side variables are the bilateral real exchange rate between Japan and each importing country and real GDP in the importing countries. Import country-specific fixed effects and time trends are included in the regressions. Annual data over the 1990–2017 period are used.

*** (**) Denotes significance at the 1 % (5 %) levels.

Source: CEPII-Chelem database, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, and calculations by the author.

Table 2b.

Panel DOLS estimates of trade elasticities for Japanese transportation equipment exports to 20 countries (exports deflated using data from the Bank of Japan).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sector | Exchange Rate Elasticity | GDP Elasticity | Adjusted R-squared | Standard Error of Regression | Number of Observations |

| Cars | −0.77*** (0.08) | 1.39*** (0.29) | 0.956 | 0.261 | 532 |

| Commercial vehicles | −0.75*** (0.16) | 3.81*** (0.66) | 0.844 | 0.660 | 531 |

| Motorcycles | −0.22 (0.15) | 4.66*** (0.50) | 0.871 | 0.462 | 533 |

| Motor vehicle parts | −0.34*** (0.08) | 1.46*** (0.23) | 0.962 | 0.217 | 534 |

Note: The coefficients come from a panel dynamic ordinary least squares regression of Japan’s exports in each sector to the 20 leading importing countries. The right hand side variables are the bilateral real exchange rate between Japan and each importing country and real GDP in the importing countries. Import country-specific fixed effects and time trends are included in the regressions. Annual data over the 1990–2017 period are used.

*** (**) Denotes significance at the 1 % (5 %) levels.

Source: CEPII-Chelem database, Bank of Japan, and calculations by the author.

The small exchange rate elasticities for motorcycles and motor vehicle parts shed light on the low PTM coefficients for these goods during yen appreciation periods that is evident in Fig. 3b. Even as exchange rate appreciations in these industries are largely passed-through to higher foreign currency prices, the volume of exports does not decline much. Thus exporters of these products have more freedom to pass-through exchange rate appreciations.

Nguyen and Sato (2019) reported that there was a change in exporter pricing behavior after the yen appreciated during the Global Financial Crisis. They found, for instance, that PTM coefficients for passenger cars over the 2010–2108 period became very large during yen appreciation periods. They posited that this low exchange rate pass-through in recent years could explain why the 35 percent depreciation of the Japanese real effective exchange rate that began in September 2012 did not stimulate Japanese net exports.

It is possible to use Eq. (3) to investigate whether car exports increased less than expected after 2012. The model in Table 2a can be re-estimated over the 1990–2012 period, and then actual out-of-sample values of the exchange rate and of GDP in the importing countries can be used to forecast car exports over the 2013–2017 period.

The model forecasts exports of USD 410 billion to the 20 countries over the 2013–2017 period, while actual exports equaled USD 308 billion. The value of exports over this period was thus 30 percent less than predicted.

Some of this shortfall is due to Japanese automobile producers relocating production abroad. However, as Shimizu and Sato (2015) noted, the strong yen in 2011–2012 caused Japanese firms to relocate production of lower end goods abroad and concentrate production of highly differentiated goods in Japan. The PTM coefficients for the higher end cars still produced in Japan should be smaller than the PTM coefficients for the combination of higher end and lower end cars produced in Japan before the offshoring. The evidence that PTM coefficients remained large indicates that exchange rates exert a smaller effect on the foreign currency prices of exports and thus on the volume of exports after 2012. The next section investigates how exchange rates affect stock returns to shed light on how they affect the profitability of goods in the transportation industry.

4. The exposure of transportation industry stocks to exchange rates

4.1. Data and methodology

Dominguez and Tesar (2006); Jaysinghe and Tsui (2008) and others have estimated exchange rate exposure equations to investigate how exchange rates affect profitability. Firm or industry stock returns (Ri,t) are regressed on changes in the log of the exchange rate (Δet) and the return on the country’s aggregate stock market (RM,t). The return on the world stock market (RW,t) is also included here to control for conditions in the rest of the world. The regression estimated is thus:

| Ri,t = αi + βi,yenΔYent + βi,M RM,t + βi,WRW,t + εi,t, | (4) |

where Ri,t is the return on firm or sector of the Japanese transportation industry, ΔYent is the change in the log of the yen/dollar exchange rate, RM,t is the return on the aggregate Japanese stock market, and RW,t is the return on the world stock market index. The data come from the Datastream database.

For Ri,t the stock returns for automobiles, automobile parts, commercial vehicles and trucks, tires, Shimano Corporation, and other individual firms are employed. The sample period extends from 1 September 1993 to 29 August 2019. There are 6782 observations.

4.2. Results

Table 3 presents exchange rate exposures for the sub-sector (and for Shimano Corporation) and Table 4 presents exposures for individual firms. The results for the other variables are available on request. The results are ordered from the sector or firm most exposed to exchange rate appreciations to the sector or firm least exposed.

Table 3.

The exposure of stock returns in the Japanese transportation equipment industry to the yen/dollar exchange rate.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sector or firm | Exchange Rate Elasticity | Standard Error | Adjusted R-squared | Standard Error of Regression | Number of Observations |

| Tires | 0.387*** | 0.042 | 0.401 | 0.0148 | 6782 |

| Automobiles | 0.325*** | 0.027 | 0.669 | 0.0096 | 6782 |

| Automobile parts | 0.241*** | 0.025 | 0.722 | 0.0086 | 6782 |

| Commercial vehicles & trucks | 0.118*** | 0.032 | 0.630 | 0.0117 | 6782 |

| Shimano | 0.007 | 0.051 | 0.000 | 0.0215 | 6782 |

Note: The exchange rate coefficients come from a regression of stock returns in each sector on the change in the yen/dollar exchange rate, the return on the Japanese stock market, and the return on the world stock market. Daily data over the 1 September 1993 to 29 August 2019 are used. There are 6782 observations. Heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation consistent standard errors are reported.

Denotes significance at the 1 % level.

Source: Datastream database, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis FRED database, and calculations by the author.

Table 4.

The exposure of firm stock returns in the Japanese transportation equipment industry to the yen/dollar exchange rate.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firm | Sector | Yen/dollar Exchange Rate Elasticity | Standard Error | Adjusted R-squared | Standard Error of Regression | Number of Observations |

| Subaru Co. | Automobiles | 0.549*** | 0.053 | 0.3792 | 0.01864 | 6782 |

| Mazda Motor Co. | Automobiles | 0.528*** | 0.057 | 0.3677 | 0.02113 | 6782 |

| Honda Motor Co. | Automobiles | 0.500*** | 0.045 | 0.4582 | 0.01546 | 6782 |

| Bridgestone | Tires | 0.411*** | 0.046 | 0.3295 | 0.01697 | 6782 |

| Aisin Seiki | Auto Parts | 0.319*** | 0.046 | 0.3850 | 0.01637 | 6782 |

| Nissan Motor Co. | Automobiles | 0.306*** | 0.044 | 0.3736 | 0.01768 | 6782 |

| Sumitomo Rubber | Tires | 0.301*** | 0.058 | 0.2836 | 0.0182 | 6782 |

| Toyota Motor Co. | Automobiles | 0.268*** | 0.033 | 0.5596 | 0.01193 | 6782 |

| Denso | Auto Parts | 0.266*** | 0.040 | 0.4818 | 0.01480 | 6782 |

| Toyota Industries | Auto Parts | 0.256*** | 0.034 | 0.4752 | 0.01324 | 6782 |

| Toyo Tires | Tires | 0.223*** | 0.055 | 0.2883 | 0.02327 | 6782 |

| Yokohama Rubber | Tires | 0.217*** | 0.049 | 0.3706 | 0.01747 | 6782 |

| Suzuki Motor Co. | Automobiles | 0.214*** | 0.046 | 0.3373 | 0.01788 | 6782 |

| Isuzu Motor Co. | Automobiles | 0.208*** | 0.059 | 0.3474 | 0.02324 | 6782 |

| Sumitomo Electric Industries | Auto Parts | 0.181*** | 0.039 | 0.4595 | 0.01481 | 6782 |

| Hino Motors | Commercial Vehicles & Trucks | 0.159*** | 0.063 | 0.3530 | 0.02148 | 6782 |

| Mitsubishi Motor Co. | Automobiles | 0.140*** | 0.053 | 0.2432 | 0.02222 | 6782 |

Note: The exchange rate coefficients come from a regression of each firm’s stock returns on the change in the yen/dollar exchange rate, the return on the Japanese stock market, and the return on the world stock market. Daily data over the 1 September 1993 to 29 August 2019 are used. Heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation consistent standard errors are reported.

Denotes significance at the 1 % level.

Source: Datastream database, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis FRED database, and calculations by the author.

The most exposed sector in Table 3 is tires. A 1 percent yen appreciation reduces the return on tire stocks by 0.387 percent. Automobiles are next, with a 1 percent appreciation reducing returns by 0.325 percent. For automobile parts, a 1 percent appreciation reduces returns by 0.241 percent and for commercial vehicles and trucks a 1 percent appreciation reduces returns by 0.118 percent. These coefficients are all significant at the 1 percent level.

For Shimano, on the other hand, the exchange rate coefficient is close to zero and not significant. This reflects the fact that Shimano produces differentiated products and is able to pass-through almost all of exchange rate appreciations into foreign currency prices.

Tires are the closest to a pure commodity. This industry is most exposed to appreciations. Automobiles are also highly exposed, reflecting the findings in Section 2 that automobile producers can only pass-through a small portion of exchange rate appreciations into foreign currency prices.

The exposure for automobile parts producers remains high. This might seem puzzling in light of the findings in Section 2 that they can pass-through most of an exchange rate appreciation into foreign currency prices. However, many auto parts makers derive substantial revenues from abroad. Auto parts maker Aisin Seiki reported that 41 percent of their sales take place outside of Japan and Denso reported that half or more of their revenue comes from outside of Japan.6 Exchange rate changes can affect the yen value of repatriated profits and thus stock prices.

The finding that commercial vehicles and truck producers are much less exposed to exchange rates than automobile producers are reflects the findings in Section 2 that bus and truck makers are able to pass-through more of exchange rate appreciations than auto makers can.

This section focuses on the share of yen invoicing as a determinant of exchange rate exposure. Another determinant is the share of exports in total sales. If overseas markets do not matter for a sector, then exchange rates may not affect stock prices.7 However, for tires the Japanese Automobile Tyre Manufacturing Association reported that the largest source of demand for Japanese tires is replacing domestic tires and that only 30 percent of production is for export. For standard passenger cars, standard trucks, and buses over the sample period, the Japanese Automobile Manufacturing Association reported ratios of exports to domestic production of 0.70, 0.74, and 0.97, respectively. For Shimano bicycle parts, more than 96 percent of sales over the last 11 years occurred outside of Japan.8 Based on these data, one would expect Shimano to be the most exposed to exchange rates, followed by commercial vehicles & trucks and then automobiles and lastly tires. The fact that Table 3 exhibits the opposite pattern indicates that producers of commoditized products are highly exposed to exchange rates while producers of differentiated products are not.

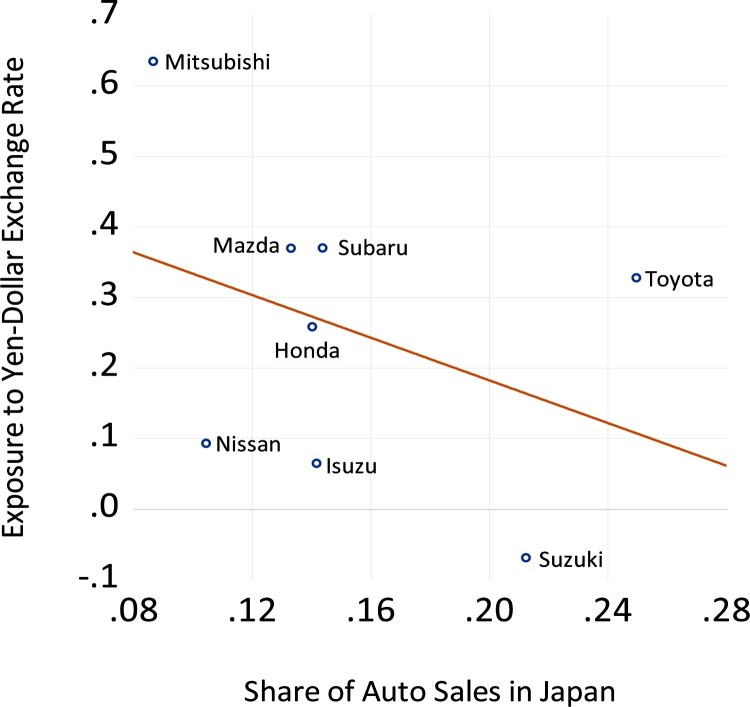

Table 4 indicates that there is substantial cross-firm heterogeneity in firms’ exposure to exchange rates. Is this due to differences in overseas market shares? Fig. 4 examines this question for the automobile industry. It plots the relationship between the share of automobile sales in Japan relative to worldwide sales for Japanese automakers and their exchange rate exposures. The share of sales is for the 2017 and 2018 fiscal years and the data are obtained from automakers’ consolidated financial statements. These two fiscal years are employed because it is possible to obtain consistent data for these two years across all the Japanese automakers. Fiscal year 2019 is not included because it extends to 31 March 2020 and there may be anomalies arising from the 2020 Coronavirus Crisis. The exchange rate exposures in the figure are estimated over the 2017 and 2018 fiscal years (i.e., from 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2019). The figure shows, as expected, that automakers with a greater share of sales in Japan are less exposed to exchange rate changes. The relationship is not tight, though, indicating that other factors are also important for understanding exchange rate exposures. Future research should investigate whether other factors such as global financial management practices or changes in the yen value of foreign factories can help explain the cross-firm differences in exchange rate exposures.

Fig. 4.

The Relationship between Japanese Automakers’ Exposure to the Yen/dollar Exchange Rate and Their Sales in Japan Relative to Their Sales in the World.

Source: Datastream database, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis FRED database, automakers’ consolidated financial reports, and calculations by the author.

Note: The share of auto sales in Japan represents the volume of automobile sales in Japan relative to volume of worldwide sales over the 2018 and 2019 fiscal years. The exposure to the yen-dollar exchange rate comes from a regression of each firm’s stock returns on the change in the yen/dollar exchange rate, the return on the Japanese stock market, and the return on the world stock market. Daily data over the 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2019 are used. There are 530 observations.

5. Conclusion

Since the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates ended in 1971, the Japanese yen has exhibited a secular appreciation trend. The strengthening yen has posed challenges for Japanese exporters. This paper investigates how fluctuations in the yen affect the Japanese transportation equipment industry. The share of yen invoicing provides information about the market power of sub-sectors of the transportation industry. At one extreme, Japanese automakers reported to Ito et al. (2018) that the automobile market in places like the U.S. is so competitive that they must invoice in the importing country’s currency. At the other extreme, Lewis and Morizono (2016) observed that Japan’s Shimano Corporation produces 75 percent of the world’s supply of bicycle brakes and gears and the BoJ reported that more than 90 percent of Japan’s bicycle parts exports are invoiced in yen.

Estimating exchange rate pass-through equations indicates that there is a close relationship between the share of yen invoicing in a subsector and long run exchange rate pass-through. Makers of small and standard cars can pass-through little of exchange rate changes into foreign currency prices while bicycle parts makers can pass-through almost all of the exchange rate changes. Sub-sectors with intermediate levels of yen invoicing such as buses and trucks have long run pass-through coefficients between those for cars and for bicycle parts. Auto parts and motorcycle manufacturers are able to pass-through most of yen appreciations into higher foreign currency prices.

Estimating export elasticities sheds light on why auto parts and motorcycle manufacturers can raise foreign currency prices when the yen appreciates. Price elasticities for these two sectors are small, implying that they can raise foreign currency prices without lowering export volumes much. On the other hand estimated elasticities for automobile exports are large. Nguyen and Sato (2019) reported that exchange rate pass-through for passenger cars after the Global Financial Crisis became smaller. They posited that low exchange rate pass-through in recent years could explain why the yen depreciation that began in September 2012 did not stimulate Japanese exports. This paper investigates whether exchange rates had less impact on automobile exports after 2012 by estimating an export equation over the 1990–2012 period and using out-of-sample values of the exchange rate and other variables to forecast car exports over the 2013–2017 period. Actual exports are 30 percent less than the model predicted, indicating that Japanese auto exports have become less responsive to exchange rates recently.

Estimating stock market exposure equations indicates that firms that pass-through more of their exchange rate changes to export prices such as makers of commercial vehicles, trucks, and bicycle parts are also less exposed to exchange rate changes than firms that price-to-market such as automobiles. Producers of differentiated products such as Shimano are thus better able than producers of commoditized goods to preserve their profitability when the yen appreciates.

For other firms to imitate Shimano and gain market power, they need to innovate. During the Japanese manufacturing revolution that occurred from the 1950s to the 1980s, engineers received a broad liberal arts education in addition to technical training. Sawa (2013) argued that this nurtured creativity, and that removing the humanities from their curriculum reduced their ability to develop world-beating products. Japanese educators should consider again providing technical students in high school and college with an education that includes copious study of literature, philosophy, and history. Also during the post-war period Japanese children received a lot of early childhood input. Heckman (2005) noted how important this is for development and recommended that mothers spend time with their young children.

During the era of rapid growth Japanese firms channeled profits into research and development (R&D) and gave engineers freedom to experiment. For instance, Tomio Wada, who pioneered liquid crystal display (LCD) research at Sharp, said that management supported researchers as they pursued their dreams. Similarly Yoshio Yamazaki, who initiated LCD work at Seiko, said that there were almost no restrictions from the company on his research.9

When the yen is weak, firms should use the extra profitability to support R&D and give researchers a free hand. The Japanese government, to the extent possible given its fiscal constraints, should also facilitate R&D by easing firms’ tax burdens.

Startups can promote entrepreneurship and introduce new products. Japan is supporting startups through programs such as J-Startup. It could also survey startups to learn more about the challenges they face and use this information to improve the business climate.

Berliant and Fujita noted in a series of paper (e.g., Berliant and Fujita, 2012, and Fujita, 2014) that when Japan was catching up to the technology frontier, close interactions among Japanese researchers and engineers was valuable. However, once Japan reached the frontier, they argued that Japanese workers were too homogeneous to lead in the development of cutting edge ideas. They needed to interact with people who had lots of independent ideas. Thus collaboration between Japanese and foreign researchers can play an important role in fostering discoveries. The Japanese government should provide incentives for cross-cultural knowledge generation.

The Japanese yen has faced appreciation pressure over the last 50 years and experienced several sharp appreciation episodes. In the past exchange rate swings caused large changes in the export of goods such as automobiles. After the Global Financial Crisis carmakers have responded to exchange rate appreciations by reducing Japanese yen export prices and squeezing profit margins rather than by reducing export volumes. To thrive in the face of volatile exchange rates and harsh global competition, transportation equipment producers should innovate and develop differentiated, knowledge-intensive goods.

Acknowledgments

I thank two anonymous referees for invaluable comments. I also thank Keiichiro Kobayashi, Masayuki Morikawa, Eiji Ogawa, Kiyotaka Sato, Junko Shimizu, Etsuro Shioji, Yushi Yoshida and other colleagues for helpful suggestions. Finally I thank Kiyotaka Sato for help in finding data. This research is supported by the JSPS Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B, 17H02532). Any errors are my own responsibility.

Footnotes

Nguyen and Sato (2019) also discussed the severe competition in the passenger car market.

Hausmann, Hidalgo, Bustos, Coscia, Simoes, and Yildirim (2014) found that similar skills are required to produce goods in the same industry.

The websites for these databases are, respectively, www.boj.or.jp, www.fred.stlouisfed.ord and www.oecd.org.

Columns (7) and (8) point to more yen invoicing for buses and small and standard cars and trucks during yen depreciation periods. Future research should investigate further how exporters’ invoicing decisions differ between appreciation and depreciation episodes.

These data are obtained from www.bls.gov and www.boj.or.jp. Export price data for motor vehicle parts from the BoJ are not available before 2000. After 2000 this series is closely related to export prices for automobiles. Before 2000, export prices for automobiles are spliced to export prices for motor vehicle parts to create a consistent deflator for motor vehicle parts.

The website for Aisin Seiki is https://www.aisin.com/investors/achievements/ and the website for Denso is https://www.denso.com/global/en/investors/financial/segment/.

I am indebted to an anonymous referee for this point.

The websites containing these data are https://www.jatma.or.jp/english/media/, http://www.jama-english.jp/, and https://www.shimano.com/en/ir/library/cms/financial_reports.html#year2019.

Wada and Yamazaki’s comments are quoted by Johnstone (1999, p. 126).

Appendix A. Importing countries for the dynamic ordinary least squares estimation

| Cars | Commercial vehicles |

Motorcycles | Motor Vehicle Parts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | Australia | Australia | Australia |

| Austria | Canada | Belgium | Belgium |

| Belgium | China, People's Rep. | Canada | Canada |

| Canada | Finland | China, People's Rep. | China, People's Rep. |

| Finland | France | France | France |

| France | Germany | Germany | Germany |

| Germany | Greece | Greece | India |

| Hong Kong | Hong Kong | Hong Kong | Indonesia |

| Ireland | Malaysia | Indonesia | Malaysia |

| Israel | Netherlands | Italy | Mexico |

| Malaysia | New Zealand | Malaysia | Philippines |

| Netherlands | Pakistan | Netherlands | Portugal |

| New Zealand | Philippines | Singapore | Saudi Arabia |

| Norway | Saudi Arabia | Spain | Singapore |

| Saudi Arabia | Singapore | Switzerland | South Korea |

| Sweden | Sweden | Taiwan | Spain |

| Switzerland | Taiwan | Thailand | Taiwan |

| Taiwan | Thailand | United Kingdom | Thailand |

| United Kingdom | United Kingdom | United States | United Kingdom |

| United States | United States | Viet Nam | United States |

References

- Berliant M., Fujita M. Culture and diversity in knowledge creation. Regional Science and Urban Economics. 2012;42:648–662. [Google Scholar]

- Campa J., Goldberg L. Exchange rate pass-through into import prices. The Review of Economics and Statistics. 2005;87:679–690. [Google Scholar]

- Ceglowski J. Has pass-through to export prices risen? Evidence for Japan. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies. 2010;24:86–98. [Google Scholar]

- Chen N., Juvenal L. Quality, trade, and exchange rate pass-through. Journal of International Economics. 2016;2016(C):61–80. [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez K., Tesar L. Exchange rate exposure. Journal of International Economics. 2006;68:188–218. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita M. Evolving spatial economy of Asia-Pacific and the growth strategy. Presentation at the RIETI World KLEMS Symposium. Growth Strategy after the World Financial Crisis; Tokyo May 20; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hausmann R., Hidalgo C., Bustos S., Coscia M., Simoes A., Yildirim M. MIT Press; Boston: 2014. The Atlas of Economic Complexity. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman J. 2005. Emerging Economic Arguments for Investing in the Health of our Children’s Learning.http://www.childrenofthecode.org/interviews/heckman.htm Interview on 24 October. Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Ito T., Koibuchi S., Sato K., Shimizu J. Exchange rate exposure and risk management: the case of Japanese exporting firms. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies. 2016;41:17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ito T., Koibuchi S., Sato K., Shimizu J. Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry; Tokyo: 2016. Choice of Invoice Currency in Japanese Trade: Industry and Commodity Level Analysis. (Working Paper 16-E-031) [Google Scholar]

- Ito T., Koibuchi S., Sato K., Shimizu J. Edward Elgar Publishing; Cheltenham, UK: 2018. Managing Currency Risk. [Google Scholar]

- Iwaisako T., Nakata H. Impact of exchange rate shocks on Japanese economy: quantitative assessment using the structural VAR model (in Japanese; genyu-kakaku, kawase- reito to nihon-keizai) Keizai Kenkyu. 2015;66(4):355–376. [Google Scholar]

- Iwaisako T., Nakata H. Impact of exchange rate shocks on Japanese exports: quantitative assessment using a structural VAR model. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies. 2017;46(December):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Jaysinghe P., Tsui A. Exchange rate exposure of sectoral returns and volatilities: evidence from Japanese industrial sectors. Japan and the World Economy. 2008;20:639–660. [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone B. Basic Books; New York: 1999. We Were Burning: Japanese Entrepreneurs and the Forging of the Electronic Age. [Google Scholar]

- Kao C.D. Spurious regression and residual-based tests for cointegation in panel data. Journal of Econometrics. 1999;90:1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis L., Morizono Y. Financial Times; 2016. Japan’s Hidden Treasure Companies Fear for Their Security. 12 January. [Google Scholar]

- Mark N., Sul D. Cointegration vector estimation by panel DOLS and long‐run money demand. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics. 2003;65:655–680. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T., Sato K. Firm predicted exchange rates and nonlinearities in pricing-to- market. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies. 2019;53:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sato K., Shimizu J., Shrestha N., Zhang S. Industry-specific real effective exchange rates and export price competitiveness. Asia Economic Policy Review. 2013;8:298–325. [Google Scholar]

- Sawa T. The Japan Times; 2013. Lack of Liberal Arts Education is Sapping Japan’s Creativity. 16 September. [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu J., Sato K. Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry; Tokyo: 2015. Abenomics, yen Depreciation, Trade Deficit, and Export Competitiveness. (Working Paper 15-E-020) [Google Scholar]

- Shioji J., Uchino T. Columbia University Center on Japanese Economy and Business, Columbia University; New York: 2012. External Shocks and Japanese Business Cycles: Impact of the “Great Trade Collapse” on the Automobile Industry. (Working Paper 300) [Google Scholar]