Abstract

The current study on the traditional use of medicinal plants was carried out from February 2018 to March 2020, in Gokand Valley, District Buner, Pakistan. The goal was to collect, interpret, and evaluate data on the application of medicinal plants. Along with comprehensive notes on individual plants species, we calculated Use Value (UV), Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC), Use Report (UR), Fidelity Level (FL), Informant Consensus Factor (FCI), as well as Family Importance Value (FIV). During the current study, a total of 109 species belonging to 64 families were reported to be used in the treatment of various ailments. It included three families (four species) of Pteridophytes, 58 families (99 species) of angiosperm, one family (three species) of Gymnosperms, and two families (three species) of fungi. The article highlights the significance of domestic consumption of plant resources to treat human ailments. The UV varied from 0.2 (Acorus calamus L.) to 0.89 (Acacia modesta Wall.). The RFC ranged from 0.059 (Acorus calamus L. and Convolvulus arvensis L.) to 0.285 (Acacia modesta Wall.). The species with 100% FL were Acacia modesta Wall. and the fungus Morchella esculenta Fr., while the FCI was documented from 0 to 0.45 for gastro-intestinal disorders. The conservation ranks of the medicinal plant species revealed that 28 plant species were vulnerable, followed by rare (25 spp.), infrequent (17 spp.), dominant (16 spp.), and 10 species endangered. The traditional use of plants needs conservation strategies and further investigation for better utilization of natural resources.

Keywords: quantitative study, ethnobotanical, indigenous, conservation, Gokand, Pakistan

1. Introduction

The inhabitants of remote regions commonly rely upon traditional knowledge concerning medicinal plants for the treatment of many diseases. Plants also provide shelter, food, forage, lumber, and firewood [1]. Moreover, plants also serve to improve air quality, prevent land erosion, and help water recycling. Medicinal plants and plant-based medicines are extensively used in healthcare systems in many developing countries, and also appreciated in many developed countries [2,3,4,5]. Plants provide 80% of the healthcare needs of the world’s population [6,7,8]. The global community has acknowledged that many ethnic communities depend on natural resources, including medicinal plants. The use of plants as traditional therapeutics provides an actual alternative in the healthcare system in evolving nations, especially for rural populations [9,10,11,12]. The investigation of therapeutic plants through qualitative survey methods has become important in recent decades [13,14,15]. The Himalayan region, including parts of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, Nepal, Myanmar, India and Pakistan is recognized as a hotspot of biodiversity, for medicinal plant species [16,17,18]. Currently, the USA, China, France, Japan, United Kingdom and Italy are considered to be the largest global markets for medicinal plants. Although most countries in Asia harvest medicinal plants for their internal traditional uses, very few, especially China, India, Indonesia, Nepal, Bangladesh, Iran and Pakistan, are capable of producing them in commercial quantity. Pakistan ranks as the 7th producer of medicinal plants in Asia [18,19]. In Pakistan, around 600 species are used as traditional medicine, and more than 75% of the local population relies upon therapeutic herbs for all or the majority of their healthcare needs. The medicinal flora is extensively utilized in the manufacturing of medicines, food, cosmetics, and dietary supplements [20]. Most of the indigenous populations still depend on plant-derived medicines [21,22]. Herbal treatments have an ancient of utilization in East Asia [23], and are believed to have few side effects and high efficiency [24,25].

Viola pilosa Blume, Diospyros lotus L., Morchella esculenta Fr., Trillium govanianum Wall. Ex D. Don are the most important medicinal species produced in Pakistan [26]. The knowledge of medicinal species has mostly been transmitted orally from generation to generation [27]. Cultural practices and local biodiversity are the driving factors of medicinal species are utilization [28,29]. Ethnomedicinal research can serve as the basis for the development of new natural remedies for native plant species [30,31,32,33,34]. In Pakistan, local market systems named “Pansar” specifically deal with medicinal species, including the export of important quantities of plants [16,35]. The utilization of plants as medication varies from 4 to 20% in various nations, and around 2500 species are traded globally [25]. In Pakistan alone, about 50,000 Ayurvedic specialists, tabibs (experts of Unani medicine), and many unregistered health experts are working in far-flung mountainous and urban areas making common use of around 200 plant species in herbal medications [36,37]. Botanical gardens, universities, and the National Council for Tibb, Hamdard, and Qarshi industries help to control and develop the herbal industry in Pakistan. There are over 4000 registered manufacturers of herbal marketable products in the country [38,39,40].

The present study addresses the issue of ethnobotanically important plants as an important source for the treatment of many ailments in the Gokand Valley. Extensive surveys, interviews and interactions with local healers focused on the reliability, efficacy and spectrum of medicinal plant use among local residents, and the economic impact of such use. In our approach, we hypothesized that: (1) Plant use, especially for medicinal purposes, was still highly important in this remote area; (2) local knowledge, although part of a common cultural sphere, would differ from neighboring areas; and (3) pressure on the resources was increasing.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Climate

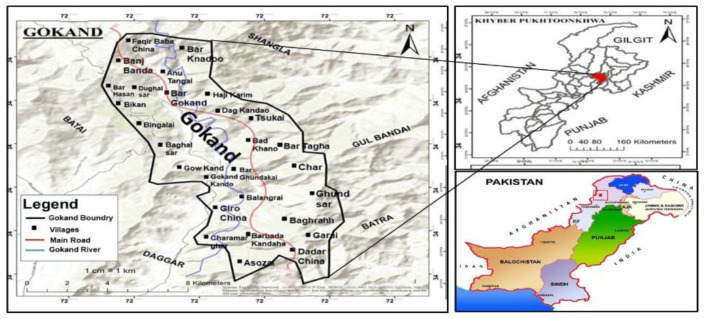

Gokand Valley, District Buner is located in the North of Province Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. It lies between 34°09′ 34°43′ N and 72°10′ 72°47′ E, covering an area of 1760 km2 (Figure 1). The region is surrounded by Swat and Shangla to the North, by Malakand Agency to the west, by Mardan District to the south and by Hazara Division to the east [41]. The climate of the lower regions of the valley is sub-tropical, and the upper regions are temperate. The summer is moderately hot and short while the winter season is cool and extends from October to March [42]. Due to high rainfall people migrate from the upper to the lower regions till the fall in average temperature. River Barandu the largest important water channel passes by the majority of the villages in the area. The maximum rainfall recorded during February and March is 289.1 mm, while 540.6 mm of precipitation falls in the rest of the year [43].

Figure 1.

Map of the research area.

2.2. Data Collection

Ethnomedicinal information was collected from February 2018 to March 2020. A purposive sampling method was used for the selection of informants, with local participants pointing out people they thought had specific medicinal plant knowledge, and information regarding the ethnomedicinal use of plants was collected through semi-structured open-ended interviews with a standard questionnaire. The interviews were carried out face-to-face with individual participants, and also in groups discussions. The respondents were briefed about the aims and objectives of the study, and the prior informed consent of each participant was obtained. The work followed the International Society of Ethnobiology Code of Ethics (International Society of Ethnobiology. International Society of Ethnobiology Code of Ethics (with 2008 additions). 2006; http://www.ethnobiology.net/what-we-do/core-programs/ise-ethics-program/code-of-ethics/code-in-english/). All the interviews were conducted in Pashto, the local language of the communities. The final selection of respondents was primarily based on their knowledge and willingness to share information. The questionnaire included data on; demographic features of the informants, vernacular names of plants, parts used, availability, route of application of plants and diseases treated.

2.3. Demographic Data of Local Participants

In the present study a total of 168 respondents, including 37 farmers, 33 homemakers, and non-professional elders, 29 plants gatherers, 26 shepherds, 14 healers, 15 hunters, 9 dealers, and 5 salespersons, were interviewed using open-ended questionnaires, face to face interviews and group discussions. Respondents of different professions and various age groups were interviewed in various seasons of the year. The age of the informants ranged from less than 20 years to above 60 years. Thirty-three informants were between 21–40 years old, while 62 informants were above 60 years old. Among the four groups of male informants, 11 were less than 20, 22 aged 21–40, 38 between 41–60, and 50 aged above 60 years. Of the female respondents, four were in the age group below 20, 11 in the age group 21–40, 20 in the age group 41–60, and 12 were over 60 years old. The majority of the local population belonged to rural areas (78.57%) and depended mainly on agricultural production (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic details.

| Variables | Categories | Number of Informants | Percentage | Sum of Reports |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender ratio | Men | 47 | 27.976 | 588 |

| Women | 121 | 72.023 | 2709 | |

| Age | <20 | 15 | 8.928 | 107 |

| 21–40 | 33 | 19.642 | 217 | |

| 41–60 | 58 | 34.523 | 409 | |

| >60 | 62 | 36.904 | 2564 | |

| Educational Background |

Illiterate | 67 | 39.88 | 1682 |

| Matric | 53 | 31.547 | 838 | |

| Intermediate | 26 | 15.476 | 352 | |

| Graduate | 17 | 10.119 | 300 | |

| Postgraduate | 5 | 2.976 | 125 | |

| Informant category | Farmer | 37 | 22.023 | 1455 |

| Elder (housewives and non-professional) |

33 | 19.642 | 930 | |

| Profession | Shepherd | 26 | 15.476 | 130 |

| Plant gatherer | 29 | 17.261 | 195 | |

| Healer | 14 | 8.333 | 453 | |

| Hunter | 15 | 8.928 | 85 | |

| Salesperson | 5 | 2.976 | 11 | |

| Dealer | 9 | 5.357 | 38 | |

| Life type | Urban area | 36 | 21.428 | - |

| Hilly area | 132 | 78.571 | - |

2.4. Plant Collection and Identification

Plants species cited for a specific disease in the area were collected, pressed and mounted on herbarium sheets for correct identification. The specimens were identified by taxonomists at the Department of Botany, University of Peshawar, and with the help of the Flora of Pakistan [44,45,46], and deposited in the Herbarium Department of Botany, University of Peshawar.

2.5. Statistical Data Analysis

The data collected were analyzed statistically using various quantitative indices: Use Value (UV), Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC), Use Report (UR), Fidelity Level (FL), Informants Consensus Factor (ICF), and Family Importance Value (FIV).

2.5.1. Use Value

Use value is used to determine the relative importance of plant species. It is calculated using the use-value formula:

| (1) |

where ‘UVi’ is the frequency of citations for species through all respondents and ‘Ni’ the number of respondents [47,48].

2.5.2. Relative Frequency of Citation and Use Reports

Relative Frequency Citation (RFC) was used to record the highest therapeutic medicinal flora of the valley, which is consumed for the treatment of numerous ailments.

| (2) |

RFC shows the importance of each species and is given by the frequency of citation FC, the number of respondents (N) in the survey as used by [48,49].

2.5.3. Fidelity Level

The Fidelity Level is the percentage of respondents who cited the uses of specific plant species to treat a specific disease in the research area. The FL index is calculated as;

| (3) |

where “Np” is the specific Number of citations for a particular ailment, and ‘N’ is the total number of informants mentioned the species for any disease [50].

2.5.4. Informant Consensus Factor

The Factor Consensus Informants (FCI) was used to evaluate the consent of respondents about the use of plant species for the treatment of various ailments categories.

| (4) |

where Nur = number of use reports from informers for a disease category treated by a plant species; Nt = number of species or taxa used for treating that disease category. FIC value ranges from 0 to 1. Where 1 represents the highest value of respondents, and 0 indicates the lowest value [51].

2.5.5. Family Importance Value

Family Importance Value (FIV) was used to determine the relative importance of families. It was calculated by taking the percentage of informants mentioning the family.

| (5) |

where FC is the number of informers revealing the family, while N is the total number of informants participating in the research [48].

2.6. Conservation Status

The Conservation status was reported for species growing wild in the area. The information was recorded and collected for different conservations attributes by following International Union for Conservation and Nature [52]. Plants were classified using International Union for Conservation of nature (IUCN) Criteria, 2001 as displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

IUCN Criteria, 2001 for conservation classes.

| Availability | Collection |

|---|---|

| 0 = Uncommon or very rare | 0 = More than 1000 kg/year |

| 1 = Less common or rare | 1 = Consumed from 500–1000 kg/year |

| 2 = Occasional | 2 = Consumed from 300–500 kg/year |

| 3 = Abundant | 3 = Consumed from 100–200 kg/year |

| Growth | Part used |

| 0 = Regrowth in more 3 years | 0 = Root/Whole |

| 1 = Regrowth within 3 years | 1 = Bark |

| 2 = Regrowth within 2 years | 2 = Seeds, Fruits |

| 3 = Regrowth within 1 year | 3 = Flowers |

| 4 = Regrowth in a season | 4 = Leaves/Gum/Latex |

| Total Score | |

| 0–4 | Endangered |

| 5–8 | Vulnerable |

| 9–12 | Rare |

| 13–14 | Infrequent |

| 15–16 | Dominant |

3. Results

3.1. Medicinal Plant Taxonomy and Growth Forms

During the current study, a total of 109 species belonging to 64 families were reported to be used in the treatment of various ailments. It included three families (four species) of Pteridophytes, 58 families (99 species) of angiosperm, one family (three species) of Gymnosperms, and two families (three species) of fungi. The species reported along with their botanical name, local name, voucher number, family, part used, preparation of remedies, route of administration, medicinal uses, frequency of citation, and relative frequency of citation with their conservation status are presented in (Table 3). The most dominant families in the term of the maximum of reported taxa were Asteraceae (six species), followed by Lamiaceae, Moraceae, and Rosaceae with five species each. The literature confirmed that Asteraceae, Lamiaceae, Moraceae, and Rosaceae were the most widely recognized therapeutic families. The most often-cited taxa were Acacia modesta, Oxalis corniculata, Mentha longifolia, Morchella esculenta, Withania somnifera, and Zanthoxylum armatum, due to their efficiency, accuracy, and easy availability.

Table 3.

Medicinal plant species and fungi in Gokand Valley, Buner, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan.

| Family | Botanical Name Local Name Voucher Number |

Availability | Habit | Part(s) Used | Preparation of Remedies | ROA | Medicinal Uses | FC | RFC | UR | UV | FL | CS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pteridophytes | |||||||||||||

| Dryopteridaceae | Dryopteris juxtaposita Christ. Kwangai B.Sul.059.UOP |

W | H | Young shoot | Juice | O | Bone weakness, dyspepsia | 43 | 0.255 | 22 | 0.51 | 65.11 | E |

| Equisetaceae |

Equisetum arvense L. Bandaky B.Sul.061.UOP |

W | H | Whole plant | Juice | O | Kidney stones | 26 | 0.154 | 11 | 0.42 | 57.69 | V |

| Pteridaceae |

Adiantum capillus-veneris L. Sumbal B.Sul.025.UO |

W | H | Whole plant | Decoction | O | Constipation, pneumonia, scorpion bite | 23 | 0.136 | 15 | 0.65 | 56.52 | E |

|

Adiantum venustum D. Don Parsohan B.Sul.026.UOP |

W | H | Whole plant | Decoction | O | Scorpion bite, constipation | 32 | 0.19 | 18 | 0.56 | 31.25 | V | |

| Angiosperm | |||||||||||||

| Acanthaceae |

Justicia adhatoda L. Bekar B.Sul.071.UOP |

W | S | Leaves | Decoction, poultice | O, top. | Wound, swelling, arthritis, headache | 30 | 0.178 | 13 | 0.43 | 50 | D |

| Acoraceae |

Acorus calamus L. Skha waga B.Sul.024.UOP |

W | H | Rhizome | Decoction | O | Menstrual cycle regularity, dyspepsia | 10 | 0.059 | 2 | 0.2 | 20 | R |

| Amaranthaceae |

Achyranthes aspera L. Ghishkay B.Sul.022.UOP |

W | H | Leaves | Juice | O | Stomachache, arthritis, diarrhea | 15 | 0.089 | 4 | 0.26 | 46.66 | I |

|

Amaranthus viridis L. Chalwery B.Sul.032.UOP |

W | H | Leaves | Juice, poultice, vegetable | O, top. | Urinary diseases, hair tonic | 12 | 0.071 | 5 | 0.41 | 33.33 | D | |

| Amaryllidaceae |

Allium jacquemontii Kunth Oraky B.Sul.031.UOP |

W | H | Leaves | Roast, decoction | O | Blood pressure, abdominal pain | 24 | 0.142 | 12 | 0.5 | 62.5 | R |

|

Narcissus poeticus L. Gul-nargus B.Sul.082.UOP |

W | H | Bulb | Juice | O | Allergy, pimples | 33 | 0.196 | 13 | 0.39 | 54.54 | C | |

| Anacardiaceae |

Pistacia integerrima J.L. Stewart ex Brandis Kharawa B.Sul.094.UOP |

W | T | Bark | Decoction | O | Hepatitis, loss of appetite | 43 | 0.255 | 22 | 0.51 | 65.11 | R |

| Apiaceae |

Pimpinella diversifolia DC. Tarpakai B.Sul.091.UOP |

W | H | Leaves | Decoction | O | Fever, stomachache, emphysema | 28 | 0.166 | 13 | 0.46 | 50 | V |

| Apocynaceae |

Caralluma edulis (Edgew.) Benth. Ex Hook.f. Famanhy B.Sul.046.UOP |

W | H | Whole plant | Decoction, powder | O | Anti-peristalsis, otitis media | 37 | 0.22 | 14 | 0.37 | 51.35 | R |

|

Nerium oleander L. Ganderay B.Sul.084.UOP |

C | S | Leaves | Roast | O | Anti-microbial, tooth ache | 21 | 0.125 | 10 | 0.47 | 66.66 | --- | |

| Araliaceae |

Hedera helix L. Payo zela B.Sul.068.UOP |

W | S | Leaves | Decoction | O | Diabetes, arthritis | 35 | 0.208 | 18 | 0.51 | 51.42 | V |

| Asclepiadaceae |

Calotropis procera (Aiton) Dryand. Spalamy B.Sul.043.UOP |

W | S | Leaves | Powder | O | Digestion, flatulence | 21 | 0.125 | 11 | 0.52 | 66.66 | E |

| Asparagaceae |

Asparagus officinalis L. Tendory B.Sul.035.UOP |

W | S | Root, young shoot | Juice | O | Fever, flatulence, kidney stones | 23 | 0.136 | 10 | 0.43 | 47.82 | V |

|

Asparagus racemosus Willd. Gangra boty B.Sul.036.UOP |

W | H | Leaves | Decoction | O, top. | Arthritis, skin diseases | 19 | 0.113 | 7 | 0.36 | 42.10 | V | |

| Asphodelaceae |

Asphodelus tenuifolius Cav. Ogaky B.Sul.037.UOP |

W | H | Leaves | Decoction | O | Blood pressure, tension | 38 | 0.226 | 17 | 0.44 | 55.26 | R |

| Asteraceae |

Artemisia vulgaris L. Tarkha B.Sul.034.UOP |

W | S | Root, leaves | Poultice | top. | Skin diseases, Intestinal worms | 38 | 0.226 | 18 | 0.47 | 47.36 | E |

|

Cichorium intybus L. Harn B.Sul.051.UOP |

W | S | Leaves | Decoction | O | Asthma, indigestion | 32 | 0.19 | 13 | 0.40 | 56.25 | V | |

|

Senecio chrysanthemoides DC. Sra jaby B.Sul.107.UOP |

W | H | Leaves, rhizome | Poultice | top. | Swelling, wound healing | 27 | 0.16 | 13 | 0.48 | 62.96 | I | |

|

Sonchus asper L. Hill Shodapy B.Sul.110.UOP |

W | H | Leaves | Decoction | O | Stomach problems, antipyretic | 15 | 0.089 | 5 | 0.33 | 40 | R | |

|

Taraxacum officinale F.H. Wigg. Ziar guly B.Sul.114.UOP |

W | H | Leaves, petals | Decoction | O | Cough, yellowness of skin eyes and urine | 18 | 0.107 | 8 | 0.44 | 38.88 | D | |

|

Xanthium strumarium L. Ghishky B.Sul.126.UOP |

W | S | Leaves, seeds | Decoction, Poultice | O, top. | Indigestion, diarrhea, smallpox | 9 | 0.053 | 3 | 0.33 | 22.22 | D | |

| Berberidaceae |

Berberis lycium Royle Kwary B.Sul.039.UOP |

W | S | Leaves, root, bark | Poultice, decoction | O, top. | Diabetic, wound healing, bone fracture, pain, diarrhea | 45 | 0.267 | 35 | 0.77 | 93.33 | V |

| Boraginaceae |

Trichodesma indicum (L.) Lehm. Ghwa jaby B.Sul.118.UOP |

W | H | Root | Poultice | top. | Anti-inflammatory, snake bite | 38 | 0.226 | 17 | 0.44 | 50 | R |

| Brassicaceae |

Capsella bursa-pastoris (L.) Medik. Bambysa B.Sul.045.UOP |

W | H | Leaves, root | Juice | O | Tension, anxiolytic | 33 | 0.196 | 12 | 0.36 | 45.45 | V |

| Nasturtium officinale R.Br. Talmera B.Sul.083.UOP | W | H | Root, young shoot | Juice, vegetable | O | Wound healing, toothache | 26 | 0.154 | 12 | 0.46 | 46.15 | D | |

| Buxaceae | Buxus wallichiana L. Shamshad B.Sul.042.UOP | W | S | Leaves | Powder, decoction | O, top. | Arthritis, bone fracture, purgative | 39 | 0.232 | 19 | 0.48 | 51.28 | V |

| Cactaceae | Opuntia dillenii (Ker Gawl.) Haw. Tohar B.Sul.086.UOP | W | H | Fruit | Juice | O | Anemia | 40 | 0.238 | 21 | 0.52 | 70 | D |

| Caesalpiniaceae | Cassiafistula L. Amaltas B.Sul.047.UOP | W | T | Fruit | Decoction | O | Constipation, skin infection, fever | 42 | 0.25 | 22 | 0.52 | 76.19 | R |

| Cannabaceae | Cannabis sativa L. Bang B.Sul.044.UOP | W | H | Leaves | Smoke, Poultice | Inhale | Sedative, narcotic, ulcer, pain killer | 34 | 0.202 | 16 | 0.47 | 70.58 | D |

| Celtis caucasica L. Tagha B.Sul.049.UOP | W | T | Bark, fruit | Decoction, Poultice | O, top. | Wound healing, burning | 37 | 0.22 | 17 | 0.45 | 54.05 | V | |

| Caryophyllaceae |

Stellaria media L. Vill. Spin goly B.Sul.112.UOP |

W | H | Leaves | Poultice | top. | Bone fracture | 32 | 0.19 | 10 | 0.31 | 40.62 | I |

| Celastraceae |

Gymnosporia royleana Wall. Sor azghay B.Sul.067.UOP |

W | S | Fruit | Direct | O | Blood purifier, gum pain | 28 | 0.166 | 10 | 0.35 | 39.28 | D |

| Chenopodiaceae |

Chenopodium album L. Srmai B.Sul.050.UOP |

W | H | Young shoot | Decoction | O | Hepatitis, constipation | 19 | 0.113 | 10 | 0.52 | 52.63 | R |

| Convolvulaceae |

Convolvulus arvensis L. Prewatai B.Sul.053.UOP |

W | H | Leaves | Powder | O | Pimple, acne, stomach problems | 10 | 0.059 | 4 | 0.4 | 30 | I |

|

Cuscuta reflexa Roxb. Nary zaila B.Sul.054.UOP |

W | H | Young shoot | Juice | O | Arthritis, blood purifier | 13 | 0.077 | 6 | 0.46 | 38.46 | I | |

| Dryopteridaceae | Dryopteris juxtaposita Christ. Kwangai B.Sul.059.UOP |

W | H | Young shoot | Juice | O | Bone weakness, dyspepsia | 43 | 0.255 | 22 | 0.51 | 65.11 | E |

| Equisetaceae |

Equisetum arvense L. Bandaky B.Sul.061.UOP |

W | H | Whole plant | Juice | O | Kidney stones | 26 | 0.154 | 11 | 0.42 | 57.69 | V |

| Ericaceae |

Conandrium arnotaimum L. Sra makha B.Sul.052.UOP |

W | S | Whole plant | Decoction | O | Skin allergy | 30 | 0.178 | 15 | 0.5 | 60 | E |

|

Rhododendron arboreum Sm. Gul-namaire B.Sul.099.UOP |

W | S | Flower | Juice | O | Antipyretic | 27 | 0.16 | 14 | 0.51 | 59.25 | I | |

| Euphorbiaceae |

Euphorbia helioscopia L. Mandanro B.Sul.062.UOP |

W | H | Latex | Powder | O | Kidney stone, cholera | 23 | 0.136 | 12 | 0.52 | 69.56 | D |

|

Euphorbia hirta L. Wrmago B.Sul.063.UOP |

W | H | Latex | Poultice, juice | O, top. | Kidney stone, bronchitis, constipation | 30 | 0.178 | 15 | 0.5 | 60 | I | |

|

Mallotus philippensis (Lam.) Müll.-Arg. Kambela B.Sul.072.UOP |

W | T | Bark, seed | Juice, direct | O | Stomach pain | 16 | 0.095 | 8 | 0.5 | 56.25 | R | |

| Fabaceae |

Acacia modesta Wall. Palosa B.Sul.021.UOP |

W | T | Gum | Direct | O | Relaxant, hepatitis | 48 | 0.285 | 43 | 0.89 | 100 | R |

| Fabaceae |

Indigofera gerardiana Wall Ghoreja B.Sul.069.UOP |

W | S | Root | Direct | O | Stomach ache | 38 | 0.226 | 16 | 0.42 | 47.36 | V |

| Fabaceae |

Robinia pseudoacacia L. Kikar B.Sul.100.UOP |

C | T | Leaves, Inflorescence | Decoction, poultice | O, top. | Spasm, diabetes | 23 | 0.136 | 9 | 0.39 | 47.82 | --- |

| Fagaceae |

Quercus incana Bartram Tor banj B.Sul.098.UOP |

W | T | Bark | Powder, Poultice | O, top. | Bone fracture, urinary disorders | 40 | 0.238 | 20 | 0.5 | 65 | V |

| Fumariaceae |

Fumaria indica (Hausskn.) Pugsley Papra B.Sul.066.UOP |

W | H | Young shoot | Decoction, juice | O | Blood pressure, vomiting, fever, antispasmodic | 41 | 0.244 | 21 | 0.51 | 68.29 | D |

| Juglandaceae |

Juglans regia L. Ghoz B.Sul.070.UOP |

C | T | Bark | Decoction | O | Wound healing, cleaning teeth | 32 | 0.19 | 12 | 0.37 | 53.12 | -- |

| Lamiaceae |

Ajuga bracteosa Wall. Ex Benth. Bote B.Sul.030.UOP |

W | H | Whole plant | Decoction, juice | O | Antipyretic, Blood pressure | 20 | 0.119 | 8 | 0.4 | 30 | E |

|

Mentha longifolia L. Welany B.Sul.074.UOP |

W | H | Leaves | Powder, juice | O | Diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain | 46 | 0.273 | 38 | 0.82 | 95.65 | I | |

|

Mentha piperata Stokes Podina B.Sul.075.UOP |

W | H | Leaves | Powder, juice | O | Abdominal pain, indigestion, diarrhea, nausea | 42 | 0.25 | 21 | 0.5 | 73.80 | D | |

|

Mentha spicata L. Podina B.Sul.076.UOP |

W | H | Leaves | Juice, powder | O | Antipyretic, vomiting, hemorrhoid | 40 | 0.238 | 20 | 0.5 | 65 | I | |

|

Otostegia limbata (Benth.) Boiss. Spin azghai B.Sul.087.UOP |

W | S | Leaves | Direct, powder | O, top. | Teeth ache, wound healing | 12 | 0.071 | 6 | 0.5 | 58.33 | I | |

| Meliaceae |

Azadirachta indica L. Meem B.Sul.038.UOP |

W | T | Leaves | Decoction | O | Hepatitis, vermicide | 45 | 0.267 | 36 | 0.80 | 95.55 | V |

|

Melia azedarach L. Tora bakyana B.Sul.073.UOP |

W | T | Leaves, seeds | Decoction | O | Anti septic, Liver disease, laxative | 17 | 0.101 | 9 | 0.52 | 64.70 | R | |

| Menispermaceae |

Tinospora cordifolia (Willd.) Miers Gelo B.Sul.116.UOP |

W | H | Leaves, seeds | Powder | O | Antipyretic, liver disorders, diuretic | 38 | 0.226 | 19 | 0.5 | 68.42 | V |

| Moraceae |

Broussonetia papyrifera (L.) Vent. Shah toot B.Sul.041.UOP |

Inv | T | Leaves | Powder | O | Diarrhea | 13 | 0.077 | 6 | 0.46 | 38.46 | --- |

|

Ficus carica L. Inza /B.Sul.064.UOP |

W | T | Fruit, latex | Direct | O | Removal of wort, stomach disorders | 21 | 0.125 | 9 | 0.42 | 61.9 | V | |

|

Ficus recemosa L. Ormal B.Sul.065.UOP |

C | T | Latex, fruit | Direct | O, top. | Inflammation due to wasp bites | 35 | 0.208 | 17 | 0.48 | 68.57 | --- | |

|

Morus alba L. Spen toot B.Sul.079.UOP |

C | T | Fruit | Direct | O | Constipation, increase digestion | 30 | 0.178 | 13 | 0.43 | 60 | --- | |

|

Morus nigra L. Tor too B.Sul.080.UOP |

C | T | Fruit | Direct | O | Coughing, laxative, cooling agent | 33 | 0.196 | 16 | 0.48 | 66.66 | --- | |

| Myrsinaceae |

Myrsine africana L. Marlorang B.Sul.081.UOP |

W | S | Leaves, fruit | Direct | O | Against worms, abdominal pain | 29 | 0.172 | 11 | 0.37 | 51.72 | R |

|

Wulfenia amherstiana L. Nar boty B.Sul.125.UOP |

W | H | Leaves | Decoction | O | Hypertension, weakness | 18 | 0.107 | 9 | 0.5 | 61.11 | R | |

| Nitrariaceae |

Peganum harmala L. Spelany B.Sul.090.UOP |

W | H | Leaves | Direct | O | Obesity | 40 | 0.238 | 21 | 0.52 | 70 | V |

| Nyctaginaceae |

Boerhavia diffusa L. nom. Cons. Zakhm boty B.Sul.040.UOP |

W | H | Root | Poultice | top. | Skin inflammation, ulcer | 45 | 0.267 | 32 | 0.71 | 88.88 | R |

| Oleaceae |

Olea ferruginea Wall. Ex Aitch. Khona B.Sul.085.UOP |

W | T | Branches | Direct | Toothbrush | Toothache | 40 | 0.238 | 20 | 0.5 | 67.5 | R |

| Oxalidaceae |

Oxalis corniculata L. Taroky B.Sul.088.UOP |

W | H | Leaves | Juice, Poultice | O, top. | Removal of wort, stomach disorders, skin inflammation | 47 | 0.279 | 40 | 0.85 | 97.87 | D |

| Papaveraceae |

Papaver rhoeas L. Zangaly khaskhash B.Sul.089.UOP |

W | H | Seed | Decoction | O | Stomachache, indigestion | 37 | 0.22 | 19 | 0.51 | 67.56 | V |

| Phyllanthaceae |

Andrachne cordifolia L. Chagzi panra B.Sul.033.UOP |

W | S | Leaves | Decoction | O | Diabetes | 41 | 0.244 | 22 | 0.53 | 60.97 | R |

| Platanaceae |

Platanus orientalis L. Cheenar B.Sul.095.UOP |

C | T | Bark | Decoction | top. | Acne, pimple | 23 | 0.136 | 11 | 0.47 | 47.82 | --- |

| Poaceae |

Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers. Kabal B.Sul.055.UOP |

W | H | Whole plant | Poultice | top. | Wound healing | 16 | 0.095 | 8 | 0.5 | 56.25 | D |

|

Sorghum halepense (L.) Pers. Dadam B.Sul.111.UOP |

W | H | Rhizome | Juice, powder | O, top. | Snake bite, anti-inflammatory | 12 | 0.071 | 3 | 0.25 | 33.33 | D | |

| Polygonaceae | Rumex dentatus L./Shalkhy/B.Sul.104.UOP | W | H | Leaves | Decoction, Poultice, vegetable | O, top. | Skin rash, wound healing | 30 | 0.178 | 15 | 0.5 | 56.66 | I |

|

Rumex hastatus D. Don Taroky B.Sul.105.UOP |

W | H | Leaves | Direct, juice, poultice | O, top. | Skin 1010late10, arthritis, purgative | 38 | 0.226 | 18 | 0.47 | 63.15 | V | |

| Portulacaceae |

Portulaca oleracea L. Warkhary B.Sul.096.UOP |

W | H | Young shoot | Vegetable, Roast | O | Constipation | 29 | 0.172 | 15 | 0.51 | 65.51 | D |

| Ranunculaceae |

Aconitum violaceum Jacquem. Ex Stapf Zahar mora B.Sul.023.UOP |

W | H | Roots | Juice, powder | O | Arthritis | 44 | 0.261 | 30 | 0.68 | 86.36 | E |

| Rhamnaceae |

Sageretia theezans Brongn. Mamana B.Sul.106.UOP |

W | S | Leaves | Juice | O | Jaundice | 43 | 0.225 | 22 | 0.51 | 67.44 | R |

|

Ziziphus nummularia (Burm.f.) Wight and Arn. Ber B.Sul.128.UOP |

W | S | Leaves, fruit | Decoction | O | Ulcer, skin infection | 19 | 0.113 | 8 | 0.42 | 57.89 | R | |

|

Ziziphus oxyphylla Edgew. Elany B.Sul.129.UOP |

W | S | Root, Fruit | Powder, decoction | O | Loss of appetite, constipation, diabetes | 37 | 0.22 | 18 | 0.48 | 64.86 | V | |

| Rosaceae |

Duchesnea indica (Jacks.) Focke Zmaky toot B.Sul.060.UOP |

W | H | Fruit | Decoction, direct | O | Sore throat, coughing | 16 | 0.095 | 7 | 0.43 | 50 | I |

|

Pyrus pashia L. Tangy B.Sul.097.UOP |

C | T | Fruit | Direct | O | Coughing, weakness | 30 | 0.178 | 14 | 0.46 | 56.66 | --- | |

|

Rosa damascena Mill. Palwarai B.Sul.101.UOP |

W | S | Petals | Juice | O | Diabetes | 37 | 0.22 | 19 | 0.51 | 54.05 | V | |

|

Rosa webbiana Wall. Ex Royle Zangaly gulab B.Sul.102.UOP |

W | S | inflorescence | Powder, direct | O | Memory stimulant, antispasmodic | 23 | 0.136 | 10 | 0.43 | 60.86 | I | |

|

Rubus fruticosus G.N. Jones Karwara B.Sul.103.UOP |

W | S | Fruit | Direct | O | Cooling agent | 32 | 0.19 | 12 | 0.37 | 46.87 | R | |

| Rutaceae |

Zanthoxylum armatum DC. Dambara B.Sul.127.UOP |

W | S | Fruit | Direct, powder | O | Gum pain, cooling agent, abdominal pain | 46 | 0.273 | 39 | 0.84 | 95.65 | V |

| Sapindaceae |

Aesculus indica (Wall. Ex Cambess.) Hook. Jawaz B.Sul.027.UOP |

C | T | Bark, seed | Direct, powder | O | Vermifuge | 40 | 0.238 | 23 | 0.57 | 65 | --- |

|

Dodonaea viscosa (L.) Jacq. Ghorasky B.Sul.058.UOP |

W | S | Leaves | Poultice | top. | Bone fracture, sprain, wound healing, | 43 | 0.255 | 26 | 0.60 | 79.06 | D | |

| Scrophulariacea |

Verbascum thapsus L. Kharghogy B.Sul.119.UOP |

W | H | Leaves | Juice | Eardrop | Otitis media | 16 | 0.095 | 8 | 0.5 | 56.25 | R |

| Simaroubaceae |

Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle Spena bakanra B.Sul.029.UOP |

W | T | Bark | Juice | O | Abdominal pain, skin irritation, pimples | 41 | 0.244 | 22 | 0.53 | 51.21 | I |

| Solanaceae |

Datura innoxia Mill. Datora B.Sul.056.UOP |

W | H | Leaves, fruit | Poultice | top. | Pimple, narcotic | 27 | 0.16 | 11 | 0.4 | 44.44 | R |

|

Solanum nigrum L. Kachmachu B.Sul.108.UOP |

W | H | Leaves, fruit | Juice, Poultice | O, top. | Gonorrhea, skin diseases | 41 | 0.244 | 21 | 0.51 | 68.29 | R | |

|

Solanum surattense Burm. Marhaghon B.Sul.109.UOP |

W | H | Root, leaves | Poultice, decoction, direct | O, top. | Bone fracture, bronchitis, antipyretic, | 43 | 0.255 | 25 | 0.58 | 76.74 | V | |

|

Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal Kotelal B.Sul.124.UOP |

W | H | Leaves | Powder, vegetable | O | Pneumonia, diuretic | 46 | 0.273 | 37 | 0.80 | 93.47 | I | |

| Tamaricaceae |

Tamarix aphylla (L.) Karst. Ghaz B.Sul.113.UOP |

C | T | Root, bark | Decoction | O, top. | Toothache, anti-inflammatory | 28 | 0.166 | 13 | 0.46 | 60.71 | --- |

| Taxaceae |

Taxus fuana Nan Li and R.R. Mill Banrya B.Sul.115.UOP |

W | T | Leaves, bark | Powder | O | Diabetes, hepatitis, pneumonia | 31 | 0.184 | 11 | 0.35 | 48.38 | V |

| Urticaceae | Debregeasia saeneb (Forssk.) Hepper Ajlai B.Sul.057.UOP |

W | S | Leaves | Powder | top. | Dry skin, fatigue | 18 | 0.107 | 8 | 0.44 | 50 | R |

| Verbenaceae |

Vitex negundo L. Marwandy B.Sul.123.UOP |

W | S | Young shoot | Juice | O | Cramps, rheumatism | 27 | 0.16 | 13 | 0.48 | 59.25 | I |

| Violaceae |

Viola canescens Wall. Banafsh /B.Sul.120.UOP |

W | H | Leaves, rhizome | Poultice | top. | Arthritis, wound healing | 34 | 0.202 | 17 | 0.5 | 67.64 | V |

|

Viola odorata L. Banafsha B.Sul.121.UOP |

W | H | Leaves | Decoction | O, top. | Emphysema, itchy throat | 31 | 0.184 | 16 | 0.51 | 64.51 | V | |

|

Viola serpens L. Boote B.Sul.122.UOP |

W | H | Root | Juice | O | Jaundice, wound | 37 | 0.22 | 18 | 0.48 | 62.16 | E | |

| Zygophyllaceae |

Tribulus terrestris L. Markundy B.Sul.117.UOP |

W | H | Leaves | Juice | O | Tuberculosis, Sore throat | 13 | 0.077 | 6 | 0.46 | 53.84 | R |

| Gymnosperm | |||||||||||||

| Pinaceae |

Cedrus deodara (Roxb.) G.Don/Ranzro/B.Sul.048.UOP |

W | T | Oil, gum | Direct | O | Refrigerant, anti septic, antipyretic | 20 | 0.119 | 10 | 0.5 | 70 | E |

|

Pinus roxburghii Sarg. Nakhtar B.Sul.092.UOP |

C | T | Bark, resin | Direct, decoction | O, top. | Antipyretic, urinary diseases, wound healing | 17 | 0.101 | 7 | 0.41 | 64.70 | --- | |

|

Pinus wallichiana A.B. Jacks. Pewoch B.Sul.093.UOP |

W | T | Resin, seeds | Direct | top. | Antipyretic, pimples | 13 | 0.077 | 5 | 0.38 | 53.84 | I | |

| Fungi | |||||||||||||

| Agaricaceae |

Agaricus campestris L. Kharyray B.Sul.028.UOP |

W | H | Whole plant | Decoction | O | Stimulant, Nutritive | 43 | 0.255 | 28 | 0.65 | 81.39 | V |

| Morchellaceae |

Morchella deliciosa Fr. Ghuchy B.Sul.077.UOP |

W | H | Whole plant | Decoction | O | Infertility, pain, anti-cholesteric | 42 | 0.25 | 23 | 0.54 | 71.42 | E |

|

Morchella esculenta Fr. Ghuchy B.Sul.078.UOP |

W | H | Whole plant | Decoction | O | Tonic, infertility | 46 | 0.273 | 40 | 0.86 | 100 | V | |

Key to abbreviations: W, wild; C, cultivated; I, invasive; H, herb; S, shrub; T, Tree; ROA, Route of administration; O, oral; top, topical; FC, frequency citation; RFC, relative frequency of citation; UR, use report; UV, use value; FL, fidelity level; CS, Conservation status; D, dominant; E, Endangered; I, infrequent; R, rare; V, vulnerable.

Herbs were the most commonly used life form, with 57 reports (52.29%), followed by shrubs which had 27 reports (24.77%) and trees with 25 reports (22.93%). The common use of wild herbs may be due to their easy accessibility and efficacy in the treatment of various diseases, compared to other life forms.

3.2. Plant Parts Used and Preparation of Remedies

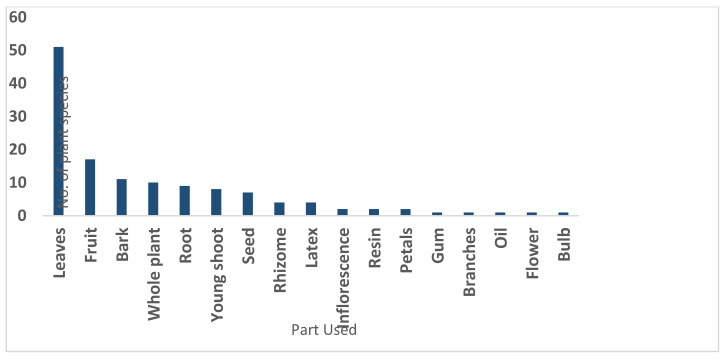

Based on a total of 3297 use reports, the part of the plants most frequently used for treating different diseases were leaves (38.63%), followed by fruit (12.87%), bark (8.33%) and whole plants (7.57%), as shown in Figure 2. The least reported plant part used was gum, bulb, oil, branches and flower, each with 1 percent.

Figure 2.

Plant parts used in the preparation of remedies.

The most commonly used method of preparation was decoction (29%), followed by juice (21%), direct and poultice, each with 16% (Figure 3). The most common method of administration of herbal recipes is decoction in different parts of the world.

Figure 3.

Medicinal plants and fungi with Highest Relative Frequency Citation.

3.3. Availability and Mode of Administration

During the collection of data, most participants said that therapeutic flora were commonly collected from various kinds of habitats, such as forests, deserts, and hilly areas. The most common route of administration of remedies was oral (66%), followed by both oral and topical (20%), topical (11%) and 1% each as toothbrush, inhaled and eardrop.

3.4. Quantitative Ethnomedicinal Data Analysis

The present work was the first ever study to record quantitative data of the medicinal flora of the region, including Relative Frequency of Citation, Use Value, Use Report, Fidelity Level, Informant Consensus Factor and Family Importance Value.

3.4.1. Use Value

The UV of the encountered plant species ranged from 0.2 to 0.89. The highest UV was found for Acacia modesta, while lowest was for Acorus calamus. Other important plant species with high use value were Morchella esculenta (0.86), Oxalis corniculata (0.85), Zanthoxylum armatum (0.84), Mentha longifolia (0.82), Withania somnifera (0.80), Azadirachta indica (0.80), Berberis lycium (0.77), Aconitum violaceum (0.68), Agaricus campestris (0.65), Adiantum capillus-veneris (0.65), Dodonaea viscosa (0.60) and Solanum surattense (0.58). It was also observed that the highest use values were due to the high number of use reports in the study area.

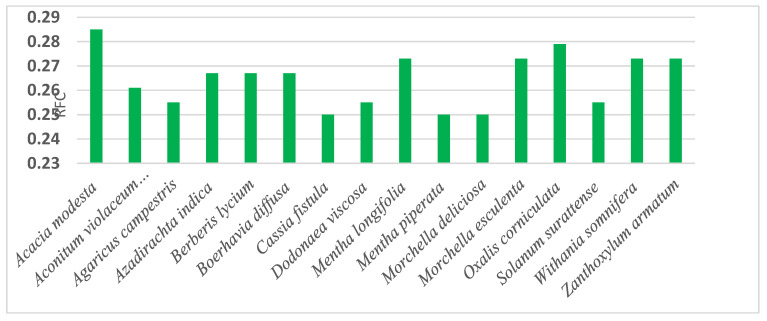

3.4.2. Relative Frequency of Citation and Use Report

The RFC value ranged from 0.059% to 0.285% for healing uses of the medicinal plants. The majority of the respondents reported a total of 16 plant species for different treatment purposes. The highest value of RFC was recorded for Acacia modesta (0.285%), followed by Oxalis corniculata (0.279%), Mentha longifolia, Morchella esculenta, Withania somnifera and Zanthoxylum armatum (0.273%) each. The gum of Acacia modesta was used for the treatment of hepatitis and as muscle relaxant. The next highest RFC was calculated for Oxalis corniculata with medical indications, such as stomach disorders, skin inflammation, and for removal of warts. Among the remaining four plants, Mentha longifolia is used for diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain; Morchella esculenta for infertility and as a tonic; Withania somnifera for Pneumonia and as diuretic; and Zanthoxylum armatum for gum pain, abdominal pain and as cooling agent. The lowest RFC value was 0.059%, recorded for Acorus calamus and Convolvulus arvensis.

In the present study, Use report value varied from 2 to 43. Acacia modesta, Mentha longifolia, Oxalis corniculata, Morchella esculenta, Withania somnifera, Zanthoxylum armatum, Azadirachta indica, Berberis lycium, Aconitum violaceum, Agaricus campestris, Dodonaea viscosa and Solanum surattense were the most used plant species.

3.4.3. Fidelity Level

Fidelity level highlights the medicinal flora, Medicinal plants with maximum curative properties have the highest fidelity level, i.e., 100%. In the present investigation, the FL varied from 20 to 100%. The plant species most commonly utilized in the research area with 100% fidelity levels were Acacia modesta and Morchella esculenta, which were used to treat hepatitis and infertility, respectively. The FL determined for, Oxalis corniculata (stomach disorders), Mentha longifolia (Diarrhea), Zanthoxylum armatum (abdominal pain), Azadirachta indica (Hepatitis), Withania somnifera (Pneumonia), Berberis lycium14 (Diabetes), and Aconitum violaceum (Arthritis) were 97.87, 95.65, 95.65, 95.55, 93.47, 93.33 and 86.36% respectively.

3.4.4. Informant Consensus Factor

The inhabitants used medicinal plants in the treatment of 64 health disorders. The important disorders were hepatitis, diabetes, diarrhea, dysentery, hypertension, anemia, arthritis, infertility and ulcer. To determine the informant consensus factor (FCI), all the reported ailments were first grouped into 15 different disease categories on the basis of their use reports (Table 4). The uppermost FCI value is reported for gastro-intestinal disorders (0.45), followed by respiratory disorders, glandular disorders (0.44) and cardiovascular disorders (0.43). Amongst the four major disease categories, gastro-intestinal disorders dominated with 137 use-reports, followed by respiratory disorders, glandular disorders, and cardiovascular disorders (110, 104, and 82 use reports, respectively) as mentioned in Table 4. About 68.8% plants were used to treat gastro-intestinal disorders, followed by respiratory disorders (56.88%), glandular disorders (53.21%), cardiovascular disorders (43.11%) analgesic, antipyretic, and refrigerant (32.11%), Dermatological disorders (29.35%), hepatic disorders (24.77%), body energizers (23.85%), and urologic disorders (20.18%). These results show that gastro-intestinal and respiratory disorders were especially common in the study area.

Table 4.

Informant consensus factor (FCI) by categories of ailments in the study area.

| Ailments Category | Nur. | % of Use Reports | Nt. | % of Species | Nur-Nt. | Nur-1 | FCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastro-intestinal disorder | 137 | 18.792 | 75 | 68.8 | 62 | 136 | 0.45 |

| Respiratory disorders | 110 | 15.089 | 62 | 56.88 | 48 | 109 | 0.44 |

| Glandular disorders | 104 | 14.266 | 58 | 53.21 | 46 | 103 | 0.44 |

| Cardiovascular disorders | 82 | 11.248 | 47 | 43.11 | 35 | 81 | 0.43 |

| Analgesic, Antipyretic and Refrigerant | 51 | 6.995 | 35 | 32.11 | 16 | 50 | 0.32 |

| Dermatological disorders | 40 | 5.486 | 32 | 29.35 | 8 | 39 | 0.20 |

| Hepatic disorders | 33 | 4.526 | 27 | 24.77 | 6 | 32 | 0.18 |

| Body energizers | 30 | 4.115 | 26 | 23.85 | 4 | 29 | 0.13 |

| Urologic disorders | 27 | 3.703 | 22 | 20.18 | 5 | 26 | 0.19 |

| Nervous disorders | 25 | 3.429 | 20 | 18.34 | 5 | 24 | 0.20 |

| Muscles and Skeletal disorders | 22 | 3.017 | 19 | 17.43 | 3 | 21 | 0.14 |

| Cancer | 21 | 2.88 | 21 | 19.26 | 0 | 20 | 0.00 |

| Ophthalmic disorders | 19 | 2.606 | 17 | 15.59 | 2 | 18 | 0.11 |

| Sexual diseases | 17 | 2.331 | 16 | 14.67 | 1 | 16 | 0.06 |

| Acoustic disorders | 11 | 1.508 | 10 | 9.17 | 1 | 10 | 0.10 |

| Mean FCI | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.226 |

Nur, Total use report; Nt, Total number of species used in a disease category; FCI, Informant consensus factor.

3.4.5. Family Importance Value (FIV)

The importance of a plant family increases with the increase in the frequency of citations of all species. Figure 4 represents 11 plant families with maximum FIV, amongst which Lamiaceae was the leading family (95.23%), followed by Solanaceae (93.45%), Asteraceae (82.73%), and Rosaceae (82.14%). Acoraceae has the lowest family importance value, with 5.95% (Table 5).

Figure 4.

Family Importance Values.

Table 5.

Family wise distribution of medicinal plants and fungi in the study area.

| Family | No. of Genera | % of Etycontribution | No. of Species | % of Contribution | FIV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asteraceae | 6 | 6.38 | 6 | 5.50 | 82.73 |

| Rosaceae | 4 | 4.25 | 5 | 4.58 | 82.14 |

| Lamiaceae | 3 | 3.19 | 5 | 4.58 | 95.23 |

| Moraceae | 3 | 3.19 | 5 | 4.58 | 78.57 |

| Solanaceae | 3 | 3.19 | 4 | 3.66 | 93.45 |

| Fabaceae | 3 | 3.19 | 3 | 2.75 | 64.87 |

| Pinaceae | 2 | 2.12 | 3 | 2.75 | 29.76 |

| Euphorbiaceae | 2 | 2.12 | 3 | 2.75 | 41.07 |

| Rhamnaceae | 2 | 2.12 | 3 | 2.75 | 58.92 |

| Violaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 3 | 2.75 | 60.71 |

| Amaranthaceae | 2 | 2.12 | 2 | 1.83 | 16.07 |

| Amaryllidaceae | 2 | 2.12 | 2 | 1.83 | 33.92 |

| Apocynaceae | 2 | 2.12 | 2 | 1.83 | 34.52 |

| Brassicaceae | 2 | 2.12 | 2 | 1.83 | 35.11 |

| Cannabaceae | 2 | 2.12 | 2 | 1.83 | 42.26 |

| Convolvulaceae | 2 | 2.12 | 2 | 1.83 | 13.69 |

| Ericaceae | 2 | 2.12 | 2 | 1.83 | 33.92 |

| Meliaceae | 2 | 2.12 | 2 | 1.83 | 36.9 |

| Myrsinaceae | 2 | 2.12 | 2 | 1.83 | 27.97 |

| Poaceae | 2 | 2.12 | 2 | 1.83 | 16.66 |

| Sapindaceae | 2 | 2.12 | 2 | 1.83 | 49.4 |

| Asparagaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 2 | 1.83 | 25 |

| Morchellaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 2 | 1.83 | 52.38 |

| Polygonaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 2 | 1.83 | 40.47 |

| Pteridaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 2 | 1.83 | 32.73 |

| Acanthaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 17.85 |

| Acoraceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 5.95 |

| Agaricaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 25.59 |

| Anacardiaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 25.59 |

| Apiaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 16.66 |

| Araliaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 20.83 |

| Asclepiadaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 12.5 |

| Asphodelaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 22.61 |

| Berberidaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 26.78 |

| Boraginaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 22.61 |

| Buxaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 23.21 |

| Cactaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 23.8 |

| Caesalpiniaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 25 |

| Caryophyllaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 19.04 |

| Celastraceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 16.66 |

| Chenopodiaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 11.3 |

| Dryopteridaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 25.59 |

| Equisetaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 15.47 |

| Fagaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 23.8 |

| Fumariaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 24.4 |

| Juglandaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 19.04 |

| Menispermaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 22.61 |

| Nitrariaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 23.80 |

| Nyctaginaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 26.78 |

| Oleaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 23.8 |

| Oxalidaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 27.97 |

| Papaveraceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 22.02 |

| Phyllanthaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 24.4 |

| Platanaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 13.69 |

| Portulacaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 17.26 |

| Ranunculaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 26.19 |

| Rutaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 27.38 |

| Scrophulariaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 9.52 |

| Simaroubaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 24.4 |

| Tamaricaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 16.66 |

| Taxaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 18.45 |

| Urticaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 10.71 |

| Verbenaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 16.07 |

| Zygophyllaceae | 1 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.91 | 7.73 |

| Total | 94 | 100 | 109 | 100 | - |

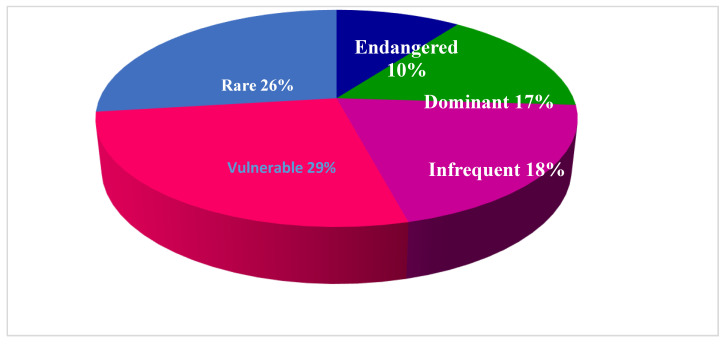

3.5. Conservation Status of the Medicinal Flora

In recent times, global conservation of threatened plant diversity has gradually increased, and governments around the world have been working on this issue. Climate change, human-caused habitat change, and the introduction of exotic plants are considered among the main drivers for habitat loss and species extinction. Therefore, ex-situ conservation is recommended for endangered species. The same holds true for the study area, but until now no project has been started for the conservation of forests or vegetation. Consistent with IUCN Red List Criteria (2001) the conservation status of the 96 wild medicinal species encountered was assessed, and 28 species were found to be vulnerable followed by 25 that were rare, 17 infrequent and 16 dominant, respectively, as shown in Figure 5. We found that 10 species were endangered in the study area, due to urbanization, small size population, anthropogenic activities, much collection, marble mining and adverse climatic conditions. The remaining 11 plants were cultivated, and 1 plant (Broussonetia papyrifera) was invasive. The lack of suitable habitat and unsustainable use have already affected their regeneration and put them into the endangered category. Indigenous knowledge can also contribute to sustainable use and conservation of important medicinal plant species.

Figure 5.

Conservation status of medicinal plants.

4. Discussion

Medicinal plant research in Asia continues to receive significant national and international attention, particularly with regard to its multiple roles in poverty alleviation and health care support. Nine countries (China, Korea, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Vietnam) have already published their National Monographs for herbal drugs, while official herbal pharmacopeias exist in Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Vietnam. In general, there is increased interest by practitioners to implement medicinal plant management and usage practices. Traditional treatments are often a gender-based occupation which both men and women perform [53]. Medicinal knowledge is still mostly passed on from one generation to another with time [54]. This suggests an urgent need for scientific investigations of these process. It is clear that comprehensive information on (formal and informal) is important for establishing sound guidelines for medicinal plants production, use, commercialization and management [18,19]. In the surrounding areas of Gokand Valley, i.e., Malakand and Swat, medicinal plants have already been documented in detail [55,56], and like in our study area, medicinal plant species were extensively used. In such earlier studies, leaves were also favored in traditional approaches [36,57,58]. In general, herbal medicines were prepared from a single plant species [10,14]. However, in some cases, more than one plant species was used in traditional recipes [59]. Around 80% of the people in emerging economies depend on therapeutic plants to treat ailments [60,61]. Indigenous healers are vital to meet the basic health requirements of local populations, not only in the study area. The medicinal plants with maximum UV required protection for sustaining biodiversity in the investigation region. However, no program or project for the maintenance and conservation of flora and vegetation is functioning in the study area, urbanization, marble mining, overharvesting and grazing were detected as the main threats to therapeutic plant species.

4.1. Ethnopharmacological Relevance

People have long histories in the uses of traditional medicinal and aromatic plants for medical purposes in the world, and currently, this use is often actively promoted. The medicinal significance of these plants can be authenticated through ethnomedicinal research, and a variety of studies have confirmed the use of medicinal species. Justicia adhatoda leaf extract is used for injuries and in joint pain [25]. Artemisia vulgaris is used against intestinal worms and for cardiac problems [25]. Leaves, roots and bark of Berberis lycium are used for diabetes, muscle growth, broken bones, and diarrhea [19,62]. Traditionally, Aconitum violaceum helps to remedy cough, asthma, neural disorders and heart disorders, as well as for treatment of joint pain and sciatica [63]. Cichorium intybus is used against gastro-intestinal problems, asthma, and gall stones [64]. Ethnobotanical research in neighboring countries also supported our research findings. Tribulus terrestris is used as a blood purifier, Nerium oleander for toothache, and scorpion stings [8,65]. The above ethnomedicinal information and similarities with other regions confirm the importance of the described plants. Broussonetia papyrifera has long been used for the treatment of inflammation in Chinese medicine, particularly to treat respiratory inflammation [66]. The extract of Mentha longifolia is used against infertility, Dyspepsia and Diarrhea because of the existence of Alkaloids, Tannins and Flavonoids [67]. The ethanolic extract of Mentha piperata is used to treat nausea, indigestion and anorexia [68]. Tribulus terrestris extracts are commercially marketed and use for the development of muscles, sore throat, mental stimulation, relaxing the period of uncontrolled climacteric in women, and digestion disorders [69]. Withania somnifera contains Withanolide A and Withaferin A and appears to possess various therapeutic activities against diseases like Alzheimer’s, cancer, fluid retention, Parkinson’s disease and diabetes [70]. Cannabis sativa contains Cannabidiol, which is used as an antipsychotic, schizophrenic agent and anxiolytic [71]. The pure leaf extract of Olea ferruginea has special inhibitory effects on fungal and bacterial pathogens [72]. Ethanolic leaves extract of Acacia modesta showed significant activity against E. coli, Proteus mirabilis, S. aureus, K. pneumonia, P. aeruginosa, S. typhi, B. cereus and B. subtilis and Streptococcus pneumonia [73]. This shows that further research on the reported ethnomedicinal plant species can lead to the recognition of novel agents with useful properties.

4.2. Novelty and Future Impacts

The comparison of our study with the ethnomedicinal literature indicated that neighboring areas [41,42,43], while the more distant areas had comparatively fewer similarities, due to cultural and traditional differences—thus, confirming our respective hypothesis. The comparative study between previously reported medicinal plants showed that six plant species, Aconitum violaceum, Broussonetia papyrifera, Cedrus deodara, Celtis caucasica, Conandrium arnotaimum, and Pinus wallichiana, were not previously documented in this area for their medicinal values. The newly reported plants (and their uses) were Aconitum violaceum (arthritis), Broussonetia papyrifera (diarrhea), Cedrus deodara (cooling and antipyretic), Celtis caucasica (wound healing), Conandrium arnotaimum (skin allergy), and Pinus wallichiana (antipyretic). These plant species might provide leads for pharmacological activities and detection of bioactive compounds in search of new drugs. The study also highlighted nine species of antipyretic plants, such as Ajuga bracteosa, Cedrus deodara, Mentha spicata, Pinus roxburghii, Pinus wallichiana, Rhododendron arboretum, Solanum surattense, Sonchus asper, and Tinospora cordifolia and nine plant species to treat arthritis, such as Achyranthes aspera, Aconitum violaceum, Asparagus racemosus, Buxus wallichiana, Cuscuta reflexa, Hedera helix, Justicia adhatoda, Rumex hastatus, and Viola canescens. Such a large number of plant species for antipyretics and arthritis pain had not previously reported anywhere in Pakistan. Sadly, many ethnobotanical studies reveal either a dramatic or gradual loss of traditional knowledge and practices [72].

5. Conclusions

The current study showed that the area has a substantial diversity of medicinal plants; utilization of medicinal plants and plant-based remedies is abundant in the area. Total of 109 medicinal species, from 64 families were documented for the treatment of 64 various ailments. Aconitum violaceum, Broussonetia papyrifera, Cedrus deodara, Celtis caucasica, Conandrium arnotaimum, and Pinus wallichiana, were reported for the first time from the study area for the treatment of arthritis, diarrhea, torridity (cooling agent), wound healing, skin allergy, and as antipyretic, respectively. This confirmed our first hypothesis—that plants used especially for medicinal purposes are still highly important in this remote area. The people of the study area are economically very deprived, and their main occupation is agriculture, work as laborers, home-run shops and engaged in livestock rearing. The terrain of Gokand valley is hilly, and most of the villages of the region are cut off from frequent visits to town and inhabitants of the area still depend on the medicinal plants for the basic health requirements. In the surrounding areas of Gokand Valley, i.e., Malakand and Swat, medicinal plants have already been documented in detail; but in current study, medicinal plant species were reported with different uses. This confirmed our second hypothesis, that the local knowledge in the research area would show distinct differences to surrounding areas. Around 80% of the people in emerging economies depend on therapeutic plants to treat ailments. Indigenous healers are vital to meet the basic health requirements of local populations. The medicinal plants with maximum UV required protection for sustaining biodiversity in the investigation region. Anthropogenic activities, such as urbanization, marble mining, overharvesting, and grazing, were detected as the main threats to local biodiversity, and this, together with increasing market demand, puts increased pressure on plant resources, as we assumed in our third hypothesis. The projects of cultivation of medicinal plants must be implemented to eliminate their extinction in the area under study.

Acknowledgments

The authors also acknowledge the participants for providing their precious information. Special thanks to the School of Computational Science KIAS South Korea, for financial support.

Author Contributions

S., S.K. and S.S., accomplished the assortment of field data and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. R.W.B. designed the project and helped in the revision of the manuscript. D.H. and M.A. helped in data analysis. D.H. acquired funds for the project, structured the contents, improved this manuscript by reviewing and editing. W.H. supervised the project. All the authors approved the final manuscript after revision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Korea Institute for Advanced Study (KIAS), 85 Hoegiro Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul, 02455, South Korea.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Abbas W., Hussain W., Hussain W., Badshah L., Hussain K., Pieroni A. Traditional wild vegetables gathered by four religious groups in Kurram District, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, North-West Pakistan. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2020;67:1521–1536. doi: 10.1007/s10722-020-00926-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asase A., Kadera M. Herbal medicines for child healthcare from Ghana. J. Herb. Med. 2014;4:24–36. doi: 10.1016/j.hermed.2013.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giday K., Lenaerts L., Gebrehiwot K., Yirga G., Verbist B., Muys B.X. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants from degraded dry afromontane forest in northern Ethiopia: Species, uses and conservation challenges. J. Herb. Med. 2017;6:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.hermed.2016.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hussain W., Hussain J., Ali R., Khan I., Shinwari Z.K., Nascimento I.A. Tradable and conservation status of medicinal plants of Kurram Valley. Parachinar, Pakistan. J. Appl. Pharmac. Sci. 2012;2:66–70. doi: 10.7324/JAPS.2012.21013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kpodar M.S., Lawson-Evi P., Bakoma B., Eklu-Gadegbeku P., Agbonon A., Aklikokou A., Gbeassor M. Ethnopharmacological survey of plants used in the treatment of diabetes mellitus in south of Togo (Maritime Region) J. Herb. Med. 2015;5:147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.hermed.2015.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hao D.-C., Xiao P.-G. Pharmaceutical resource discovery from traditional medicinal plants: Pharmacophy- logeny and pharmacophylogenomics. Chin. Herb. Med. 2020;9:11. doi: 10.1016/j.chmed.2020.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wagh V.V., Jain A.K. Ethnopharmacological survey of plants used by the Bhil and Bhilala ethnic community in dermatological disorders in Western Madhya Pradesh, India. J. Herb. Med. 2020;19:100234. doi: 10.1016/j.hermed.2018.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adeniyi A., Asase A., Ekpe P.K., Asitoakor B.K., Adu-Gyamfi A., Avekor P.Y. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants from Ghana; confirmation of ethnobotanical uses, and review of biological and toxicological studies on medicinal plants used in Apra Hills Sacred Grove. J. Herb. Med. 2018;14:76–87. doi: 10.1016/j.hermed.2018.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayta S., Polat R., Selvi S. Traditional uses of medicinal plants in Elazığ (Turkey) J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014;155:171–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Umair M., Altaf M., Abbasi A.M. An ethnobotanical survey of indigenous medicinal plants in Hafizabad district, Punjab-Pakistan. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0177912. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ekor M. The growing use of herbal medicines: Issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Front. Pharmacol. 2014;7:1–10. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2013.00177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahomoodally F., Suroowan S., Sreekeessoon U. Adverse reactions of herbal medicine a quantitative assessment of severity in Mauritius. J. Herb. Med. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.hermed.2018.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kayani S., Ahmad M., Zafar M., Sultana S., Khan M.P.Z., Ashraf M.A., Hussain J., Yaseen G. Ethnobotanical uses of medicinal plants for respiratory disorders among the inhabitants of Gallies–Abbottabad, Northern Pakistan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014;156:47–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmad K.S., Hamid A., Nawaz F., Hameed M., Ahmad F., Deng J., Akhtar N., Wazarat A., Mahroof S. Ethnopharmacological studies of indigenous plants in Kel village, Neelum Valley, Azad Kashmir, Pakistan. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2017;13:68. doi: 10.1186/s13002-017-0196-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ong H.G., Kim Y.D. Quantitative ethnobotanical study of the medicinal plants used by the Ati Negrito indigenous group in Guimaras Island, Philippines. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014;157:228–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rashid N., Gbedomon R.C., Ahmad M., Salako V.K., Zafar M., Malik K. Traditional knowledge on herbal drinks among indigenous communities in Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan. J. Ehnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018;14:16. doi: 10.1186/s13002-018-0217-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shinwari Z.K., Qaisar M. Efforts on conservation and sustainable use of medicinal plants of Pakistan. Pak. J. Bot. 2011;43:5–10. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hussain S., Malik F., Khalid N., Qayyum M.A., Riaz H. A Compendium of Essays on Alternative Therapy. InTech; London, UK: 2012. Alternative and traditional medicines systems in Pakistan: History, Regulation, Trends, Usefulness, Challenges, Prospects and Limitations; p. 67. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanwal H., Sherazi B.A. Herbal medicine: Trend of practice, perspective, and limitations in Pakistan. Asian Pac. J. Health Sci. 2017;4:6–8. doi: 10.21276/apjhs.2017.4.4.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petrakoua K., Iatroub G., Lamari F.N. Ethnopharmacological survey of medicinal plants traded in herbal markets in the Peloponnisos, Greece. J. Herb. Med. 2020;19:100305. doi: 10.1016/j.hermed.2019.100305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farooq A., Amjad M.S., Ahmad K., Altaf M., Umair M., Abbasi M.A. Ethnomedicinal knowledge of the rural communities of Dhirkot, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019;15:45. doi: 10.1186/s13002-019-0323-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hussain W., Badshah L., Ullah M., Ali M., Ali A., Hussain F. Quantitative study of medicinal plants used by the communities residing in Koh-e-Safaid Range, northern Pakistani-Afghan borders. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018;14:30. doi: 10.1186/s13002-018-0229-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kangl A., Moon S.K., Cho S.Y., Park S.U., Jung W.S., Park J.M., Ko C.N., Cho K.H., Kwon S. Herbal medicine treatments for essential tremor: A retrospective chart review study. J. Herb. Med. 2020;19:100295. doi: 10.1016/j.hermed.2019.100295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eddouks M., Bidi A., El-Bouhali B., Hajji L., Zeggwagh N.A. Antidiabetic plants improving insulin sensitivity. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2014;66:1197–1214. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malik K., Ahmad M., Zafar M., Ullah R., Mahmood H.M., Parveen B., Rashid N., Sultana S., Shah S.N. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used to treat skin diseases in northern Pakistan. BMC Compl. Altern. Medici. 2019;19:210. doi: 10.1186/s12906-019-2605-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sher H., Aldosari A., Ali A., De Boer H.J. Economic benefits of high value medicinal plants to Pakistani communities: An analysis of current practice and potential. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2014;10:71. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-10-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fatima A., Ahmad M., Zafar M., Yaseen G., Khan M.P.Z., Butt M.A., Sultana S. Ethnopharmacological relevance of medicinal plants used for the treatment of oral diseases in Central Punjab-Pakistan. J. Herb. Med. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.hermed.2017.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kasilo O.M., Trapsida J.M., Ngenda M.C., Lusamba-Dikassa P.S. World Health Organization. An overview of the traditional medicine situation in the African region. Afr. Health Monit. 2010;4:7–15. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mwangia V.I., Mumob R.M., Nyachieoa A., Onkoba N. Herbal medicine in the treatment of poverty associated parasitic diseases: A case of sub-Saharan Africa. J. Herb. Med. 2017;10:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.hermed.2017.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hussain W., Ullah M., Dastagir G., Badshah L. Quantitative ethnobotanical appraisal of medicinal plants used by inhabitants of lower Kurram, Kurram agency, Pakistan. [(accessed on 22 February 2020)];Avic. J. Phyt. 2018 8:313. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6204146/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahmood A., Malik R.N., Shinwari Z.K. Indigenous knowledge of medicinal plants from Gujranwala district, Pakistan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013;148:714–723. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haq F., Ahmad H., Alam M. Traditional uses of medicinal plants of Nandiar Khuwarr catchment (district Battagram), Pakistan. J. Med. Plants Res. 2011;5:39–48. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aziz M.A., Khan A.H., Adnan M., Ullah H. Traditional uses of medicinal plants used by Indigenous communities for veterinary practices at Bajaur Agency, Pakistan. J. Ehnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018;14:11. doi: 10.1186/s13002-018-0212-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dilshad S.M.R., Rehman N.U., Ahmad N., Iqbal A. Documentation of ethnoveterinary practices for mastitis in dairy animals in Pakistan. Pak. Vet. J. 2010;30:167–171. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shaheen S., Ramzan S., Haroon N., Hussain K. Ethnopharmacological and systematic studies of selected medicinal plants of Pakistan. [(accessed on 14 April 2020)];Pak. J. Sci. 2014 66:175–180. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263451852. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Umair M., Altaf M., Bussmann R.W., Abbasi A.M. Ethnomedicinal uses of the local flora in Chenab riverine area, Punjab province Pakistan. J. Ehnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019;15:7. doi: 10.1186/s13002-019-0285-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ullah N. Medicinal Plants of Pakistan: Challenges and Opportunities. Int. J. Complement. Alt. Med. 2017;6:00193. doi: 10.15406/ijcam.2017.06.00193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shinwari Z.K. Medicinal plants research in Pakistan. J. Med. Plants Res. 2010;4:161–176. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Usman ghani K. Reshaping of Eastern Medicine in Pakistan. RADS J. Pharm. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2017;5:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shah A.H., Khan S.M., Shah A.H., Mehmood A., Rehman I.U., Ahmad H. Cultural usesof plants among Basikhel tribe of District Tor Ghar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Pak. J. Bot. 2015;47:23–41. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zaman S.U., Ali K., Khan W., Ali M., Jan T., Nisar M. Ethno-botanical and geo-referenced profiling of medicinal plants of Nawagai Valley, District Buner (Pakistan) Biosyst. Divers. 2018;26:56–61. doi: 10.15421/011809. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hamayun M. Ethnobotanical studies of some useful shrubs and trees of District Buner, NWFP, Pakistan. [(accessed on 24 March 2020)];Ethnobot. Leafl. 2003 2003:12. Available online: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/ebl/vol2005/iss1/43. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khan A., Gilani S.S., Hussain F., Durrani M.J. Ethnobotany of Gokand valley, District Buner, Pakistan. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2003;6:363–369. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2003.363.369. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ali S.I., Nasir Y.J., editors. 1989–1992. Flora of Pakistan. No. 191-193. Islamabad, Karcahi

- 45.Ali S.I., Qaiser M., editors. 1993–2015. Flora of Pakistan. No. 194-221. Islamabad, Karachi

- 46.Nasir E., Ali S.I., editors. 1970–1989. Flora of West Pakistan. No. 1-131. Islamabad, Karachi

- 47.Ferreira F.S., Brito S.V., Ribeiro S.C., Almeido W.O., Alves R.R.N. Zootherapeutics utilized by residents of the community Poco Dantas, Crato-CE, Brazil. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2009;5:21. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-5-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vitalini S., Iriti M., Puricelli C., Ciuchi D., Segale A., Fico G. Traditional knowledge on medicinal and food plants used in Val San Giacomo (Sondrio, Italy)—An alpine ethnobotanical study. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013;145:517–529. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yaseen G., Ahmad M., Sultana S., Alharrasi A.S., Hussain J., Zafar M. Ethnobotany of medicinal plants in the Thar Desert (Sindh) of Pakistan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015;163:43–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Idm’hand E., Msanda F., Cherifi K. Ethnobotanical study and biodiversity of medicinal plants used in the Tarfaya Province, Morocco. Acta Ecol. Sinica. 2020;40:134–144. doi: 10.1016/j.chnaes.2020.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heinrich M., Ankli A., Frei B., Weimann C., Sticher O. Medicinal plants in Mexico: Healers’ consensus and cultural importance. Soc. Sci. Med. 1998;47:1859–1871. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anonymous. IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria: Version 3.1. IUCN Species Survival Commission IUCN; Gland, Switzerland: Cambridge, UK: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oliver S.J. The role of traditional medicine practice in primary health care within aboriginal Australia: A review of the literature. J. Ehnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013;9:46. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kamalebo H.M., Malale H.N.S.W., Ndabaga C.M., Degreef J., Kesel A.D. Uses and importance of wild fungi: Traditional knowledge from the Tshopo province in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. J. Ehnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018;14:13. doi: 10.1186/s13002-017-0203-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barkatullah I.M., Rauf A., Hadda T.B., Mubarak M.S., Patel S. Quantitative ethnobotanical survey of medicinal flora thriving in Malakand Pass Hills, Khyber PakhtunKhwa, Pakistan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015;169:335–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.04.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shah S.A., Shah N.A., Ullah S., Alam M.M., Badshah H., Ullah S., Mumtaz A.S. Documenting the indigenous knowledge on medicinal flora from communities residing near Swat River (Suvastu) and in high mountainous areas in Swat-Pakistan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016;182:67–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kidane L., Gebremedhin G., Beyene T. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Ganta Afeshum District, Eastern Zone of Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018;14:64. doi: 10.1186/s13002-018-0266-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nguyen X.-M.-A., Bun S.-S., Ollivier E., Dang T.-P.-T. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by K’Ho-Cil people for treatment of diarrhea in Lam Dong Province, Vietnam. J. Herb. Med. 2020;19:10032. doi: 10.1016/j.hermed.2019.100320. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abbasi A.M., Shah M.H., Khan M.A. Wild Edible Vegetables of Lesser Himalayas: Ethnobotanical and Nutraceutical Aspects. Volume 1 Springer; Cham, Switzerland: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tuasha N., Petros B., Asfaw Z. Medicinal plants used by traditional healers to treat malignancies and other human ailments in Dalle District, Sidama Zone, Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018;14:15. doi: 10.1186/s13002-018-0213-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ouelbani R., Bensari S., Mouas T.N., Khelifi D. Ethnobotanical investigations on plants used in folk medicine in the regions of Constantine and Mila (North-East of Algeria) J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016;194:196–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ahmad M., Zafar M., Shahzadi N., Yaseen G., Murphey T.M., Sultana S. Ethnobotanical importance of medicinal plants traded in Herbal markets of Rawalpindi-Pakistan. J. Herb. Med. 2017;11:78–89. doi: 10.1016/j.hermed.2017.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sabir S., Arshad M., Hussain M., Sadaf H.M., Imran M., Yasmeen F., Chaudhari S.K. A probe into biochemical potential of Aconitum violaceum: A medicinal plant from Himalaya. Asi. Pacific J. Trop. Dis. 2016;6:502–504. doi: 10.1016/S2222-1808(16)61076-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Abbas Z., Khan S.M., Abbasi A.M., Pieroni A., Ullah Z., Iqbal M., Ahmad Z. Ethnobotany of the Balti community, Tormik valley, Karakorum range, Baltistan, Pakistan. J. Ehnobiol. Ethnomed. 2016;12:38. doi: 10.1186/s13002-016-0114-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Günes S., Savran A., Paksoy M.Y., Kosar M., Cakılcıoglu U. Ethnopharmacological survey of medicinal plants in Karaisalı and its surrounding (Adana-Turkey) J. Herbal Med. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.hermed.2017.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ko H.J., Oh S.K., Jin J.H., Son K.H., Kim H.P. Inhibition of Experimental Systemic Inflammation (Septic Inflammation) and Chronic Bronchitis by New Phytoformula BL Containing Broussonetia papyrifera and Lonicera japonica. Biomol. Ther. 2012;21:66–71. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2012.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Asghari G., Akbari M., Asadi-Samani M. Phytochemical analysis of some plants from Lamiaceae family frequently used in folk medicine in Aligudarz region of Lorestan province. Marmara Pharmaceut. J. 2017;21:506–514. doi: 10.12991/marupj.311815. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mehmood A., Murtaza G. Phenolic contents, antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of Olea ferruginea Royle (Oleaceae) BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2018;18:173. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2239-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Semerdjieva I.B., Zheljazkov V.D. Chemical Constituents, Biological Properties, and Uses of Tribulus terrestris: A Review. Natur. Prod. Communi. 2019;14:1934578X19868394. doi: 10.1177/1934578X19868394. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nair A.R., Praveen N. Biochemical and phytochemical variations during the growth phase of Withania somnifera (L.) Dunal. J. Pharmaco. Phytoch. 2019;8:1930–1937. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Asati A.K., Sahoo H.B., Sahu S., Dwivedi A. Phytochemical and pharmacological profile of Cannabis sativa L. Int. J. Ind. Herbs Drugs. 2017;2:37–45. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sarwar W. Pharmacological and phytochemical studies on Acacia modesta Wall; A review. J. Phytopharmac. 2016;5:160–166. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yeşil Y., İnal İ. Traditional knowledge of wild edible plants in Hasankeyf (Batman Province, Turkey) Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2019;88:3633. doi: 10.5586/asbp.3633. [DOI] [Google Scholar]