Abstract

Background

Studies suggest that dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers may be associated with reduced risk for Parkinson disease (PD).

Objective

To assess the effect of isradipine, a dihydropyridine calcium-channel blocker, on the rate of clinical progression of PD.

Design

Multicenter, randomized, parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02168842)

Setting

57 Parkinson Study Group sites in North America.

Participants

Patients with early-stage PD (duration <3 years) who were not taking dopaminergic medications at enrollment.

Intervention

5 mg of immediate-release isradipine twice daily or placebo for 36 months.

Measurements

The primary outcome was change in the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) parts I to III score measured in the antiparkinson medication “ON” state between baseline and 36 months. Secondary outcomes included time to initiation and use of antiparkinson medications, time to onset of motor complications, change in nonmotor disability, and quality- of-life measures.

Results

336 patients were randomly assigned (mean age, 62 years [SD, 9]; 68% men; disease duration, 0.9 year [SD, 0.7]; mean UPDRS part I to III score, 23.1 [SD, 8.6]); 95% of patients completed the study. Adjusted least-squares mean changes in total UPDRS score in the antiparkinson medication ON state over 36 months for isradipine and placebo recipients were 2.99 (95% CI, 0.95 to 5.03) points versus 3.26 (CI, 1.25 to 5.26) points, respectively, with a treatment effect of —0.27 (CI, —3.02 to 2.48) point (P = 0.85). Statistical adjustment for antiparkinson medication use did not change the findings. Secondary outcomes showed no effect of isradipine treatment. The most common adverse effects of isradipine were edema and dizziness.

Limitation

The isradipine dose may have been insufficient to engage the target calcium channels associated with neuroprotective effects.

Conclusion

Long-term treatment with immediate-release isradipine did not slow the clinical progression of early-stage PD.

Primary Funding Source

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Parkinson disease (PD) is a significant and increasing public health problem. It is the second most common chronic neurodegenerative disease, after Alzheimer disease, and affects nearly 1% of the population older than 65 years (1). The prevalence of PD is expected to double in the next 20 years in the world’s most populous nations (2). The economic burden of PD is estimated to be $23 billion annually in the United States and is projected to increase to $50 billion by 2040 (3). Disease progression leads to increased disability and caregiver burden and decreased productivity and quality of life, culminating in nursing home placement and death (4). Despite several prior studies, there are no proven strategies for slowing the progression of PD, and this is a major unmet need (5).

Isradipine, a dihydropyridine calcium-channel blocker approved for the treatment of hypertension, has been shown to be neuroprotective in animal models of PD (6–8). The neuroprotective effect is mediated by inhibition of plasma membrane CAV-1 L-type calcium channels, which trigger mitochondrial oxidant stress and turnover (7, 8). Neuroprotective effects were achieved at plasma concentrations within a dose range approved for humans, consistent with the tolerable dose identified in a prior phase 2 study of isradipine in PD (8–10). Of note, several epidemiologic studies have demonstrated a reduced risk for PD in persons receiving dihydropyridines compared with other antihypertensive agents (11–13). Therefore, convergent data support is- radipine’s potential to slow the progression of PD. We report the results of a phase 3 study of the efficacy of isradipine in early-stage PD (STEADY-PD III [Safety, Tolerability, and Efficacy Assessment of Isradipine for PD]). The study was designed to evaluate the effect of isradipine on clinical progression in previously untreated patients with early-stage PD.

Methods

Design Overview

This was a 36-month, multicenter, randomized, parallel-group, placebo-controlled trial. Patients were randomly assigned in 1:1 allocation to active treatment or placebo. Patients and investigators were blinded to treatment assignment. Recruitment was done from November 2014 through November 2015, and the last patient completed the study in November 2018. The trial design has been previously published (14). The protocol was approved by the ethics committee at the University of Rochester, which served as the study coordination center, and at each participating site. All patients provided written informed consent. The trial was done in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. An independent data and safety monitoring board appointed by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) reviewed blinded and unblinded data on a regular basis. Because of the rapidity of enrollment and at the recommendation of the data and safety monitoring board, a planned interim analysis for futility and efficacy was not done. The authors attest to adherence to the protocol and accuracy and completeness of the data and analysis.

Setting and Patients

Patients were recruited from 57 Parkinson Study Group sites. The Parkinson Study Group is a nonprofit consortium of expert Parkinson centers in North America. Patients were eligible to participate in the trial if they received a diagnosis of PD within the previous 3 years that was confirmed by the site investigator on the basis of the established diagnostic criteria (15), were aged 30 years or older, had Hoehn and Yahr stage 2 disease or lower (16), and had insufficient disability to warrant initiation of use of dopaminergic antiparkinson medications (levodopa, dopamine agonist, or monoamine oxidase B inhibitors) at the time of recruitment and for at least 3 months from the baseline visit. Use of amantadine or anticholinergics at stable doses before enrollment was allowed. Patients were excluded if they had a diagnosis of an atypical parkinsonism, prior exposure to dopaminergic antiparkinson medications, history or presence of orthostatic hypotension at screening, bradycardia, congestive heart failure, cognitive dysfunction, or clinically significant depression.

Randomization and Interventions

After a baseline assessment, eligible patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio by a central Web- based program to receive either 5 mg of immediate- release isradipine twice daily or matching placebo. Is- radipine (2.5 mg) was purchased through a wholesale pharmacy and delivered to the University of Rochester Clinical Materials Services Unit, which overencapsulated isradipine (2.5 mg), manufactured matching placebo, did dissolution and stability testing, implemented the randomization assignment, and delivered study drug kits to the participating sites. Randomization, done by the Biostatistics Center at the University of Rochester, was stratified by site and used permuted blocks of size 4.

Dosages were titrated to the 5-mg twice-daily dosage during a period of 4 to 12 weeks, and patients were then followed prospectively and systematically during a maintenance period over the remaining 36 months after enrollment. This was followed by a 3-day titration off the study drug and a 2-week final safety visit. Temporary study drug suspensions and rechallenges were allowed at the discretion of the site investigator, and patients who permanently discontinued use of the study drug were encouraged to remain in the study. Patients requiring antiparkinson medications were seen for a scheduled or unscheduled visit before treatment initiation. Study visits took place every 3 months during the first year and every 6 months thereafter.

Outcomes and Follow-up

The primary outcome was the change in Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) parts I to III score from baseline to 36 months. The UPDRS includes subscales for mental function (part I), activities of daily living (part II), and motor function (part III); scores range from 0 to 176, with higher scores indicating greater disability (17). The scale is sensitive to the effect of antiparkinson medications. In patients receiving antiparkinson therapy, the scale is routinely administered in the defined medication “OFF” state (≥12 hours after the last dose) to assess disability without the benefit of antiparkinson medications and in the “ON” state (approximately 1 hour after a dose) to assess the effect of these medications. In patients who started antiparkinson therapy, the primary outcome measure was assessed in the medication ON state, but OFF scores were collected and assessed as a secondary outcome measure. Assessments of patients not receiving antiparkinson medications were included in both the ON and OFF state analyses.

Secondary outcomes were prespecified in the statistical analysis plan. Before data collection, the following secondary outcomes were identified as “key” in response to a request from the data and safety monitoring board: time to initiation of antiparkinson therapy; time to onset and severity of motor complications (motor fluctuations, dyskinesia) for patients receiving antiparkinson medications, as assessed by part IV of the UPDRS; the difference in use of antiparkinson medications, calculated as the levodopa equivalent doses between treatment groups (18); and the change in the Movement Disorder Society UPDRS (19) parts I (nonmotor experiences of daily living) and II (motor experiences of daily living) scores from baseline to 36 months in the medication ON state. A full list of secondary analyses listed in the protocol and the statistical analysis plan is included in the Supplement (available at Annals.org).

Plasma pharmacokinetic samples were collected at the screening and the 3- or 6-month visits as a measure of adherence and for an interim analysis to ensure that predose mean trough concentrations were not below a predefined limit (0.2 ng/mL). Full analysis of the pharmacokinetic data will be reported separately. Blood DNA and plasma samples collected at screening and study completion were stored for future unspecified research.

Information on adverse events was collected at every visit through open-ended questions, and the investigator rated severity and causality. A serious adverse drug event was defined as any adverse event that occurred at any dose and resulted in death, a life- threatening adverse event, inpatient hospitalization or prolongation of an existing hospitalization, persistent or significant disability or incapacity, or a congenital anomaly. Trial monitoring and data management were done in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice Guideline.

Statistical Analysis

We aimed to detect a 4-point difference between the treatment groups in the change in total UPDRS score at 36 months. This change was estimated to be approximately 25% of the disease worsening that would have occurred over 36 months without antiparkinson medication, as estimated from prior studies (20, 21). A residual SD of 12 units around the primary analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model was assumed (2022). We estimated that a total sample of 286 patients would be required to detect this difference between groups, with 80% power and a 2-sided a of 0.05. Accounting for a total dropout rate of 15% over 3 years yielded a total sample size of 336 patients.

The primary statistical analyses used ANCOVA, with the change from baseline to the 36-month visit in the total UPDRS score measured in the defined ON state as the outcome variable, the baseline value of the total UPDRS score as a continuous covariate, and the enrolling site and assigned treatment entered as categorical predictors. The 7 sites enrolling fewer than 4 participants were grouped together. A 2-step sensitivity analysis was done to adjust for the possible effect of treatment with antiparkinson medications on the primary comparison. The first step, done before unblinding of treatment assignments, used a mixed-model analysis of aggregated data from all patient visits to estimate the effect on the total UPDRS score at each visit of the current and cumulative (at and up to that visit) exposure to antiparkinson medications, measured in levodopa equivalent doses. By using patients as their own controls, this analysis avoided artifacts due to variable rates of disease progression, with more rapid worsening resulting in increased medication use (23). In the second step, the results from the first step were used to project the total UPDRS score at 36 months that would have been seen had the patient not received antiparkinson therapy. This was done by applying the 2 coefficients estimated from the first step to each patient’s end-of-study dose and cumulative use of antiparkinson medications. The ANCOVA was then repeated to assess the effect of the randomized treatment on these projected values. In addition to these prespecified analyses, a post hoc longitudinal analysis using mixed models was done.

Analyses of the secondary outcome measures were done in similar manner to the primary analysis. Times to need for antiparkinson medications and to onset and severity of motor fluctuations and dyskinesia were compared using a proportional hazards model, with stratification by site and low-enrolling sites grouped together. Exploratory analyses to detect possible differences in effectiveness of isradipine by sex, race/ethnicity, age, disease severity, and presentation at baseline (24) were done by fitting separate models within each dichotomized subgroup and testing the interaction between subgroup and assigned treatment in a combined 4-group model. Analyses were done using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute), specifically PROC GLM and PROC MIXED for continuous outcomes and PROC PHREG and PROC LIFETEST for the time-to-event outcomes. Full details, including the reasons for this choice of analytic approach, and the computer code for the prespecified and post hoc analyses are provided in the Supplement.

Role of the Funding Source

This study was funded by NINDS. Research officers (W.R.G. and C.L.) at NINDS were involved in the study design, interpretation of results, review or revision of this manuscript, and the decision to submit this manuscript for publication and are listed as authors. There was no industry involvement in the trial.

Results

Patients

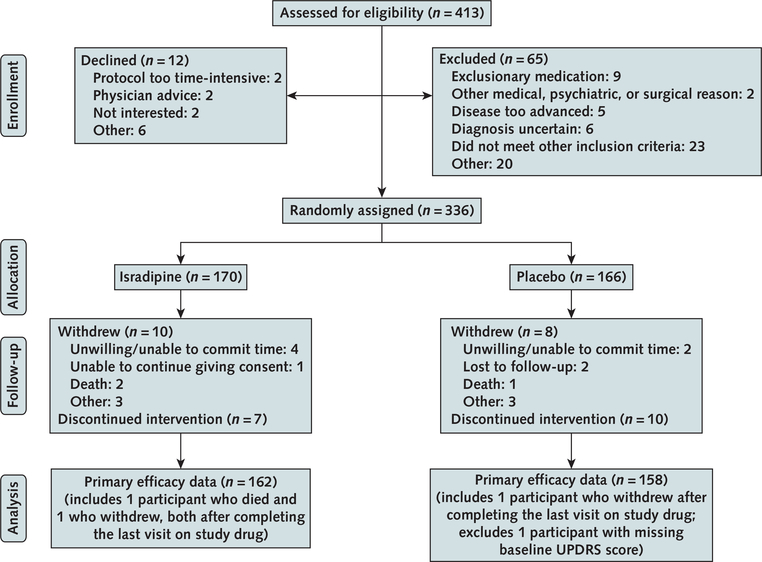

Of 413 patients screened for eligibility, 336 were enrolled and randomly assigned (170 to isradipine and 166 to placebo). Reasons for exclusion are listed in Figure 1. Baseline characteristics of the enrolled cohort are detailed in Table 1. Mean age was 62.1 (SD, 8.7) and 61.6 (SD, 9.3) years and mean disease duration from diagnosis was 9.9 (SD, 8.1) and 10.6 (SD, 9.4) months in the isradipine and placebo groups, respectively. The groups were generally well balanced, but UPDRS part III (motor) and Hoehn and Yahr stage scores were slightly higher (worse) and 39- item Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire scores were lower (better) in the isradipine group than the placebo group (Table 1). A total of 162 patients in the isradipine group and 158 in the placebo group completed both baseline and final evaluations on the study drug at month 36, with 137 (87%) patients in the isradipine group and 141 (89%) in the placebo group receiving the 10-mg dose. Among patients randomly assigned to isradipine, mean plasma trough isradipine concentration at 3 months was 0.68 (median, 0.57 ng/mL [range, 0.12 to 4.14 ng/ mL]) (n = 158). Thirteen (8%) of these patients had a plasma trough concentration less than 0.2 ng/mL. At month 36, a total of 145 patients in the isradipine group and 147 in the placebo group had started use of antiparkinson medications.

Figure 1. Study flow diagram.

Patients were included in the primary analysis if they received a total score on parts I to III of the UPDRS in the “ON” state at both the baseline visit and the last visit on the study drug at 3 y. UPDRS = Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Disease Characteristics

| Characteristic | Isradipine (n = 170) | Placebo (n = 166) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD), y | 62.1 (8.7) | 61.6 (9.3) |

| Men, n (%) | 122 (71.8) | 108 (65.1) |

| Non-Hispanic white race, n (%) | 156 (91.8) | 146 (88.0) |

| Mean disease duration from diagnosis (SD), mo | 9.9 (8.1) | 10.6 (9.3) |

| Family history of PD (first-degree relatives), n (%) | 30 (17.6) | 35 (21.1) |

| Left-handed, n (%) | 20 (11.8) | 19 (11.4) |

| Receiving symptomatic therapy, n (%) | ||

| Amantadine | 15 (8.8) | 11 (6.6) |

| Anticholinergics | 3 (1.8) | 2 (1.2) |

| Mean UPDRS score (SD) | ||

| Total | 23.7 (8.6) | 22.6 (8.5) |

| Part I (mental) | 0.6 (0.9) | 0.8 (1.2) |

| Part II (ADL) | 5.0 (2.9) | 5.4 (3.3) |

| Part III (motor) | 18.1 (7.3) | 16.3 (6.5) |

| PIGD | 0.2 (0.2) | 0.2 (0.2) |

| Tremor | 0.5 (0.3) | 0.5 (0.3) |

| Mean Hoehn and Yahr stage (SD) | 1.7 (0.5) | 1.6 (0.5) |

| Mean Schwab and England ADL scale score (SD) | 94.4 (5.2) | 94.0 (6.8) |

| Mean modified Rankin score (SD) | 1.1 (0.3) | 1.1 (0.3) |

| Mean Montreal Cognitive Assessment score (SD) | 28.1 (1.4) | 28.0 (1.3) |

| Mean Beck Depression Inventory total score (SD) | 4.1 (3.7) | 4.8 (4.3) |

| Mean PDQ-39 total score (SD) | 7.1 (6.1) | 9.1 (8.5) |

| Mean systolic blood pressure (SD), mm Hg* | 128.1 (17.2) | 127.7 (14.6) |

| Mean diastolic blood pressure (SD), mm Hg* | 76.5 (9.7) | 77.8 (8.5) |

ADL = activities of daily living; PD = Parkinson disease; PDQ-39 = 39-item Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire; PIGD = postural instability and gait disorder; UPDRS = Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale.

Measured while patient was seated.

Outcomes

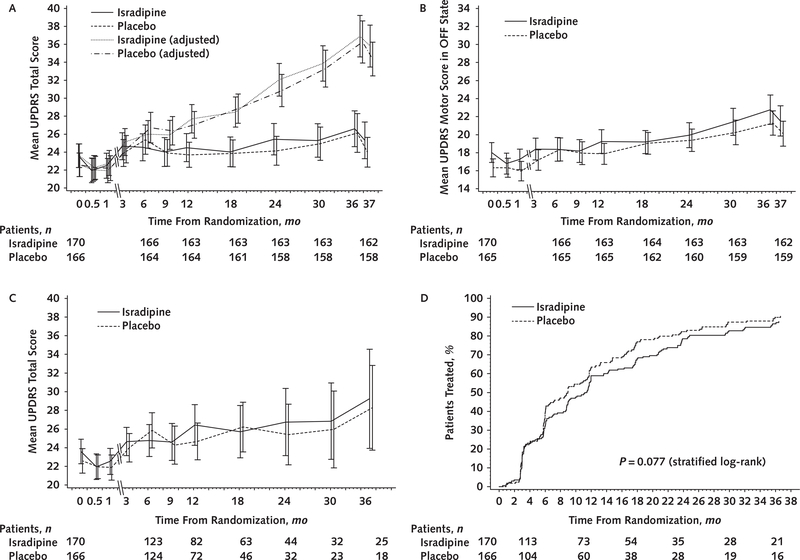

The estimated least-squares mean changes from baseline to 3 years in the primary outcome-total UPDRS score-were 2.99 (95% CI, 0.95 to 5.03) points in the isradipine group and 3.26 (CI, 1.25 to 5.26) points in the placebo group (Table 2). The estimated treatment effect of — 0.27 (CI, —3.02 to 2.48) point was small, and the CI excluded the hypothesized 4-point benefit. Antiparkinson medication use at 3 years was similar between groups, and the sensitivity analysis found no effect of medication use on the primary comparison. Figure 2 (A) shows the means and 95% CIs for total UPDRS score at each visit, both the observed values and those adjusted for antiparkinson medication use. The post hoc mixed-model analysis also showed similar rates of worsening in the isradipine and placebo groups (Supplement). Subgroup analyses (not shown) found no differential effects of isradipine on the primary outcome by age, sex, race/ethnicity, or baseline disease severity.

Table 2.

Changes in Primary and Secondary Measures From Baseline to the 3-Year Visit

| Measure | Isradipine |

Placebo |

LSM Adjusted Difference (95% CI) | P Value* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | Mean Observed Change (SD) | LSM Adjusted Change (95% CI) | Patients, n | Mean Observed Change (SD) | LSM Adjusted Change (95% CI) | |||

| Primary | ||||||||

| UPDRS total score† | 162 | 3.21 (12.57) | 2.99 (0.95 to 5.03) | 158 | 3.71 (13.73) | 3.26 (1.25 to 5.26) | −0.27 (−3.02 to 2.48) | 0.85 |

| Adjusted UPDRS score‡ | 162 | 13.52 (13.23) | 13.49 (11.32 to 15.66) | 158 | 13.84 (13.82) | 13.85 (11.72 to 15.98) | −0.36 (−3.28 to 2.56) | 0.81 |

| Key secondary | ||||||||

| Levodopa equivalent dose§ | 162 | 376 (378) | 389 (337 to 441) | 159 | 361 (273) | 375 (325 to 426) | 14 (−55 to 83) | 0.69 |

| Cumulative levodopa equivalent dose∥ | 162 | 656 (602) | 676 (588 to 765) | 159 | 667 (531) | 697 (611 to 784) | −21 (−140 to 98) | 0.73 |

| UPDRS part IV score (complications of therapy)¶ | 134 | 1.12 (1.74) | 1.18 (0.90 to 1.46) | 140 | 0.94 (1.45) | 1.07 (0.80 to 1.33) | 0.11 (−0.26 to 0.48) | 0.55 |

| MDS-UPDRS nonmotor EDL score | 162 | 1.96 (3.86) | 1.93 (1.28 to 2.59) | 158 | 1.51 (4.41) | 1.76 (1.13 to 2.40) | 0.17 (−0.72 to 1.05) | 0.71 |

| MDS-UPDRS motor EDL score | 161 | 2.54 (4.61) | 2.32 (1.52 to 3.12) | 159 | 2.66 (5.55) | 2.57 (1.78 to 3.35) | −0.24 (−1.32 to 0.84) | 0.66 |

| Secondary | ||||||||

| UPDRS part II score (ADL) | 162 | 2.68 (4.01) | 2.30 (1.63 to 2.97) | 158 | 2.67 (4.53) | 2.50 (1.83 to 3.16) | −0.20 (−1.11 to 0.71) | 0.67 |

| UPDRS part III OFF score (motor)** | 129 | 3.91 (8.84) | 4.60 (3.05 to 6.14) | 133 | 5.02 (8.77) | 4.50 (3.02 to 5.98) | 0.09 (−1.97 to 2.16) | 0.93 |

| Schwab and England ADL scale score | 162 | −4.35 (6.59) | −4.14 (−5.30 to −2.98) | 159 | −4.53 (8.29) | −4.41 (−5.54 to −3.27) | 0.27 (−1.29 to 1.83) | 0.73 |

| Modified Rankin score†† | 163 | 0.20 (0.73) | 0.18 (0.07 to 0.28) | 160 | 0.30 (0.66) | 0.29 (0.18 to 0.39) | −0.11 (−0.26 to 0.04) | 0.136 |

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment score | 162 | −0.11 (2.09) | −0.04 (−0.36 to 0.28) | 158 | −0.11 (1.88) | −0.07 (−0.39 to 0.25) | 0.03 (−0.40 to 0.46) | 0.89 |

| PDQ-39 total score | 158 | 3.15 (7.65) | 2.80 (1.42 to 4.18) | 155 | 3.23 (9.38) | 3.42 (2.07 to 4.77) | −0.61 (−2.47 to 1.24) | 0.52 |

| Ambulatory capacity | 162 | 0.60 (1.63) | 0.59 (0.34 to 0.85) | 158 | 0.51 (1.67) | 0.50 (0.25 to 0.75) | 0.09 (−0.25 to 0.44) | 0.60 |

ADL = activities of daily living; EDL = experiences of daily living; LSM = least-squares mean; MDS = Movement Disorder Society; PDQ-39 = 39-item Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire; UPDRS = Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale.

For comparisons of LSMs (not adjusted for multiple comparisons).

Primary outcome measure.

Adjusted for current and cumulative use of antiparkinson therapy.

Levodopa equivalent dose in milligrams at the 3-y visit.

Cumulative levodopa equivalent dose in milligram-years through the 3-y visit.

Sum of parts A and B (dyskinesias and clinical fluctuations).

All participants with separate pre- and postdose forms at the 3-y visit (n = 262).

Scores for the 3 deceased participants reset to 5.

Figure 2. Primary and key secondary outcomes.

UPDRS = Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale. A. Mean UPDRS parts I to III score calculated in the ON state for patients receiving antiparkinson medications, by study visit. The baseline, 2-wk, and 1-mo visits are separated for clarity. The plot shows observed means and 95% CIs. Adjusted values were adjusted for current and cumulative levodopa equivalent doses. B. Mean UPDRS part III score for all patients. The plot shows observed means and 95% CIs. Patients receiving antiparkinson therapy at any visit were evaluated in the OFF state at that visit. C. Mean total UPDRS score for all patients before initiation of antiparkinson therapy. The plot shows observed means and 95% CIs. Data from patients receiving antiparkinson therapy at any visit were excluded in the calculations for that visit. D. Time to antiparkinson therapy, calculated in days from enrollment but shown in months. The P value was calculated using the log-rank test with stratification by site.

Analyses of the key secondary outcome measures and all other secondary outcomes, including the UPDRS part III OFF scores and the change in total UPDRS score before initiation of antiparkinson therapy, also found no differences between groups (Table 2; Figure 2, B to D). There were no marked differences between groups in the numbers who initiated antiparkinson therapy (145 in the isradipine group vs. 147 in the placebo group), had dyskinesia (24 vs. 19, respectively), or had fluctuations (57 vs. 64, respectively) or in the time to first occurrence of initiation of antiparkinson therapy (hazard ratio, 0.79 [CI, 0.61 to 1.03]; P = 0.077) (Figure 2, D), dyskinesia (hazard ratio, 1.53 [CI, 0.78 to 3.01]; P = 0.21), or fluctuations (hazard ratio, 0.83 [CI, 0.56 to 1.22]; P = 0.35).

There were 68 serious adverse events (Appendix Table 1, available at Annals.org), 6 of which were deemed to be possibly related to the study intervention-4 in the isradipine group (bradycardia, spinal fracture, syncope, and transient ischemic attack) and 2 in the placebo group (stress cardiomyopathy and syncope). The 3 fatal events (sepsis and ischemic stroke in the isradipine group and basal ganglia hemorrhage in the placebo group) were all judged to be unrelated to the study medication. Adverse events reported by 5% or more of patients are listed in Table 3. Among these, 2 were more frequent in the isradipine group than in the placebo group: dizziness (24.7% vs. 15.7%; risk difference, 9.0 percentage points [CI, 0.5 to 17.6 percentage points]) and peripheral edema (18.2% vs. 5.4%; risk difference, 12.8 percentage points [CI, 6.1 to 19.6 percentage points]). Ten adverse events (7 in the isradipine group and 3 in the placebo group) led to discontinuation of treatment (Table 3). There were sustained decreases of 7 mm Hg in mean systolic blood pressure and 4 mm Hg in mean diastolic blood pressure in the isradipine group over 36 months compared with the placebo group (Appendix Table 2, available at Annals.org), but these did not lead to a higher dropout rate.

Table 3.

Adverse Events*

| Adverse Event | Isradipine (n = 170) | Placebo (n = 166) |

|---|---|---|

| Any adverse event | 163 (95.9) | 156 (94.0) |

| Any serious adverse event† | 27 (15.9) | 28 (16.9) |

| Death | 2 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Discontinuation due to adverse event | 7 (4.1)‡ | 3 (1.8)§ |

| Adverse events occurring in ≥5% of patients | ||

| Dizziness | 42 (24.7) | 26 (15.7) |

| Nausea | 26 (15.3) | 32 (19.3) |

| Headache | 28 (16.5) | 17 (10.2) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 23 (13.5) | 22 (13.3) |

| Constipation | 23 (13.5) | 21 (12.7) |

| Fatigue | 23 (13.5) | 20 (12.0) |

| Edema | 31 (18.2) | 9 (5.4) |

| Arthralgia | 17 (10.0) | 21 (12.7) |

| Insomnia | 19 (11.2) | 19 (11.4) |

| Back pain | 18 (10.6) | 16 (9.6) |

| Anxiety | 20 (11.8) | 13 (7.8) |

| Depression | 20 (11.8) | 13 (7.8) |

| Musculoskeletal pain | 12 (7.1) | 15 (9.0) |

| Muscle spasms | 11 (6.5) | 13 (7.8) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 12 (7.1) | 11 (6.6) |

| Fall | 7 (4.1) | 15 (9.0) |

| Pain in extremity | 11 (6.5) | 9 (5.4) |

| Sinusitis | 7 (4.1) | 13 (7.8) |

| Joint swelling | 12 (7.1) | 7 (4.2) |

| Cough | 9 (5.3) | 9 (5.4) |

| Somnolence | 10 (5.9) | 8 (4.8) |

| Sleep disorder | 9 (5.3) | 8 (4.8) |

Values are presented as numbers (percentages) of participants experiencing the event at least once.

Defined as any adverse event that occurred at any dose and resulted in death, a life-threatening adverse event, inpatient hospitalization or prolongation of an existing hospitalization, persistent or significant disability/incapacity, or a congenital anomaly.

Fatigue, leg edema (n = 2), muscle weakness, joint swelling, spinal fracture, and muscle spasm.

Myocardial infarction, orthostatic hypotension, and gastroesophageal reflux.

Discussion

This randomized trial showed no significant difference in the change in UPDRS scores over 36 months in patients receiving 5 mg of immediate-release isradipine twice daily versus those receiving placebo. None of the secondary outcome measures demonstrated benefit of isradipine. Hence, these results do not support the hypothesis that isradipine, at this dose, slows the progression of early-stage PD.

The study was appropriately designed and powered to address the primary objectives. Retention was much better than hypothesized, but the rate of clinical progression in both groups was lower than in previous studies, likely because of the use of antiparkinson medications (25, 26). In our power calculations, we hypothesized that use of these medications would reduce the 3-year change in total UPDRS score from 16 to 4 points, which accorded well with the actual results of the mixed-model analysis. Our choice of ANCOVA using only the baseline and final evaluations for the primary analysis, rather than a mixed- model longitudinal data analysis of trajectories in UPDRS score using data from all study visits, was motivated by concern about the interpretation of data from the intermediate visits, when varying proportions of patients would be receiving antiparkinson medications. However, the post hoc analyses of the full longitudinal data had results similar to those of the prespecified primary analysis. Exploratory analyses, not reported here, suggested that once patients started antiparkinson therapy, their total UPDRS score remained essentially constant for the remainder of the study, presumably because their doses were increased to maintain their function.

Compared with other recent studies of putative disease-modifying agents in early-stage PD, STEADY-PD III was unusual in extending follow-up to 3 years and assessing the primary outcome at 36 months, a time when most patients were receiving antiparkinson medications. We selected a 3-year study duration to test the hypothesis that if isradipine was effective, its effect would persist beyond the early stages of the disease, and we chose to test efficacy in the antiparkinson medication ON state to reflect the real-life scenario in which most patients with PD initiate antiparkinson therapy within the first year of diagnosis. We also posited that this real-world scenario would help to improve recruitment and retention. Although we considered alternative study designs, including delayed start, prolonged washout, and a “simple, long-duration” design, these would have required a substantially larger sample and have their own limitations (25–27). Finally, we do not believe that the choice of the primary outcome affected the study results because no secondary outcome measures showed a difference between groups.

Our study has several limitations. The dose was selected on the basis of the tolerability threshold established in the phase 2 study and may have been too low to provide the necessary inhibition of the targeted caveolin-1 calcium channels. Furthermore, a method for directly measuring target calcium-channel engagement with systemic isradipine administration in humans does not exist, raising the possibility that its brain bioavailability was lower in humans than in the preclinical models. It is also possible that by the time of clinical PD diagnosis in patients, the mechanisms driving progression are no longer being adequately modeled in animals. Indeed, epidemiologic studies of dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers demonstrated on average a 30% reduction in the risk for a new diagnosis of PD, and only 1 study showed a reduced rate of disease progression (11–13, 28). Thus, it is possible that treatment during the prodromal phase of the disease, before the development of motor disability, would be more effective (5).

We conclude that treatment with 5 mg of immediate- release isradipine twice daily did not slow the clinical progression of early-stage PD, as measured by the change in the UPDRS score and various other measures and instruments. Whether other interventions are able to achieve more effective inhibition of the caveolin-1 calcium channels in the brain or initiation of the treatment at earlier prodromal stages of the disease will be effective in slowing progression of PD may warrant further study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: By grants U01NS080818 and U01NS080840 from NINDS.

Appendix: Members of the Parkinson Study Group STEADY-PDIII

Investigators

Members of the Parkinson Study Group STEADY-PD III Investigators who authored this work are:

Steering Committee

Tanya Simuni, MD (Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois); David Oakes, PhD (University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, New York); Kevin Biglan, MD (Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, Indiana); Wendy R. Galpern, MD (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland); Robert Hauser, MD (University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida); Karen Hodgeman, BA (University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, New York); Elise Kayson, MS (University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, New York); Daniel Kinel, JD (Harter Secrest & Emery LLP, Rochester, New York); Anthony Lang, MD (Toronto Western Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada); Codrin Lungu, MD (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health, Rockville, Maryland); Saloni Sharma, MD (University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, New York); Ira Shoulson, MD (University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, New York); Christopher G. Tarolli, MD (University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, New York); Dalton J. Surmeier, PhD (Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois); Charles Venuto, PharmD (University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, New York); Robert Holloway, MD (University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, New York).

Members ofthe Parkinson Study Group STEADY-PD III Investigators who contributed to this work but did not author it

Clinical Investigators

Katie Kompoliti, MD, Rush University Medical Center; Irene Richard, MD, University of Rochester Medical Center; Ruth Schneider, MD, University of Rochester Medical Center; Marian Evatt, MD, Emory University School of Medicine; Vanessa Hinson, MD, PhD, Medial College of South Carolina; Alok Sahay, MD, University of Cincinnati/Cincinnati Children’s Hospital; Irene Lit- van, MD, University of California, San Diego; Eris S. Farbman, MD, University of Nevada School of Medicine; Brad Racette, MD, Washington University; Karen Blindauer, MD, Medical College of Wisconsin; Karen Thomas, DO, Sentara Neurology Specialists; Cheryl Water, MD, Columbia University Medical Center; Connie Marras, Toronto Western Hospital, University Health Network; Corneliu C. Luca, MD, PhD, University of Miami; Albert Hung, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital; Andre Deik, MD, University of Pennsylvania; Deborah Burke, MD, University of South Florida; Cindy Zadikoff, MD, Northwestern University; Michel Panisset, MD, CHUM-Hospital Notre-Dame; Marcie Rabin, MD, Atlantic Neuroscience Institute, Overlook Medical Center; Matthew Brodsky, MD, Oregon Health & Science University; Kelly Mills, MD, MHS, Johns Hopkins University; Alexander Shtilbans, MD, PhD, Weill Cornell Medicine; Era Hanspal, MD, Albany Medical Center; Chadwick W. Christine, MD, University of California, San Francisco; Thyagarajan Subramanian, MD, Penn State College of Medicine; Mya Caryn Schiess, MD, University of Texas McGovern Medical School; Rajeev Kumar, MD, Rocky Mountain Movement Disorders Center; Kelvin L. Chou, MD, University of Michigan; Binit Shah, MD, University of Virginia; Mark Guttman, MD, The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health; Holly Shill, MD, Banner Research Institute; John Slevin, MD, University of Kentucky Medical Center; John L. Goudreau, DO, PhD, Michigan State University; Ariane Park, MD, MPH, Ohio State University; John Bertoni, MD, PhD, University of Nebraska; Marie H. Saint-Hilaire, MD, Boston University; Natividad Stover, MD, University of Alabama; Camila Aquino, MD, University of Utah; David Shprecher, DO, University of Utah; Anwar Ahmed, MD, Cleveland Clinic; Lisa Shulman, MD, University of Maryland School of Medicine; Sotirios A. Parashos, MD, PhD, Struthers Parkinson’s Center; Stephen Lee, MD, PhD, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center; Paul Tuite, MD, University of Minnesota; Melanie Langlois, MD, CHU de Quebec - Hospital Enfant-Jesus; Fabio Danisi, MD, Health Quest Medical Practice; Pinky Agarwal, MD, Booth Garden Parkinson’s Care Center; Tiago Mestre, MD, Ottawa Hospital Civic Site; David Russell, MD, PhD, Institute for Neurodegenerative Disorders; Daniel Truong, MD, The Parkinson’s & Movement Disorder Institute; Neal Hermanowicz, MD, University of California, Irvine; Richard Zweig, MD, LSU Health Science Center Shreveport; Oksana Suchowersky, MD, University of Alberta Hospital; Justyna R. Sarna, MD, PhD, University of Calgary; G. Webster Ross, MD, Veterans Affairs/Pacific Health Research and Education Institute.

Clinical Coordinators

Lucia Blasucci, Rush University Medical Center; Carol Zimmerman, University of Rochester Medical Center; Shonna Jenkins, Medical College of South Carolina; Erin Neefus, University of Cincinnati/Cincinnati Children’s Hospital; Mary Pecoraro, Washington University; Lynn Wheeler, Medical College of Wisconsin; Lisa Richardson, Sentara Neurology Specialist; Amber Ratel, Columbia University Medical Center; Julie Racioppa, Toronto Western Hospital, University Health Network; Grace Bwala, Massachusetts General Hospital; Suzanne Reichwein, University of Pennsylvania; Claudia Rocha, University of South Florida; Karen Williams, Northwestern University; Kelli Keith, Oregon Health & Science University; Emily Carman, Johns Hopkins University; Sharon Evans, Albany Medical Center; Aaron Daley, University of California, San Francisco; Kala Venkiteswaran, Penn State Medical College; Vicki Ephron, University of Texas McGovern Medical School; Karen Ortiz, Rocky Mountain Movement Disorders Center; Angela Stovall, University of Michigan; Molly Goddard, Banner Research Institute; Renee Wagner, University of Kentucky Medical Center; Katherine Ambrogi, Ohio State University; Carolyn Peterson, University of Nebraska; Cathi A. Thomas, Boston University; Michelle Cines, University of Maryland School of Medicine; Patricia Ede, Struthers’s Parkinson’s Center; Pauline LeBlanc, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center; Susan Ro- landelli, University of Minnesota; Bryan Lewis, Health Quest Medical Practice Division of Neurology; Anna Fierro, Booth Garden Parkinson’s Care Center; Breanna Chew, University of California, Irvine; Jeanne McGee, LSU Health Science Center Shreveport; Paul McCann, University of Alberta Hospital; Michael Matwichyna, Veterans Affairs/Pacific Health Research and Education Institute.

Biostatistics (Data Analysis)

Arthur Watts, BS, Biostatistics, University of Rochester Medical Center; Michael McDermott, PhD, Biostatistics, University of Rochester Medical Center; Shirley Eberly, MS, Biostatistics, University of Rochester Medical Center.

Project Management (Data Acquisition and Study Coordination)

Brittany Greco, BS, CCRA, University of Rochester Medical Center; Susan Henderson, AAS, University of Rochester Medical Center; Jillian Lowell, BS, University of Rochester Medical Center.

Data and Safety Monitoring Board

Andrew Siderowf, MD, MSCE (chair, medical director); Rick Chappell, PhD (board member); Jay Phillips (board member); Kapil D. Sethi, MD (board member); William B. White, MD (board member).

Appendix Table 1.

Serious Adverse Events*

| Serious Adverse Event | Isradipine (n = 170), n | Placebo (n = 166), n |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiac | ||

| Bradycardia | 1† | 0 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 | 1 |

| Stress cardiomyopathy | 0 | 1† |

| Congenital | ||

| Spina bifida | 1 | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal | ||

| Appendiceal mucocele | 1 | 0 |

| Dysphagia | 0 | 1 |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 1 | 1 |

| Small-bowel obstruction | 1 | 0 |

| General | ||

| Chest discomfort | 1 | 0 |

| Infections | ||

| Appendicitis | 0 | 1 |

| Perforated appendicitis | 0 | 1 |

| Bronchiolitis | 0 | 1 |

| Viral gastroenteritis | 1 | 0 |

| Meningitis | 0 | 1 |

| Pneumonia | 0 | 1 |

| Acute pyelonephritis | 0 | 1 |

| Sepsis | 2‡ | 0 |

| Urinary tract infection | 1 | 0 |

| Injury | ||

| Humerus fracture | 0 | 1 |

| Spinal fracture | 1† | 0 |

| Stress fracture | 2 | 0 |

| Upper limb fracture | 1 | 1 |

| Wristfracture | 0 | 1 |

| Metabolism | ||

| Dehydration | 0 | 1 |

| Musculoskeletal | ||

| Arthralgia | 0 | 1 |

| Arthritis | 1 | 1 |

| Back pain | 1 | 1 |

| Osteoarthritis | 4§ | 1 |

| Neoplasms | ||

| B-cell lymphoma | 0 | 1 |

| Breast cancer | 0 | 1 |

| Choroid melanoma | 1 | 0 |

| Colon cancer | 2 | 0 |

| Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma | 0 | 1 |

| Pancreatic neoplasm | 1 | 0 |

| Pituitary tumor | 0 | 1 |

| Prostate cancer | 2 | 0 |

| Rectal cancer | 0 | 1 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 0 | 1 |

| Throat cancer | 1 | 0 |

| Nervous system | ||

| Aphasia | 0 | 1 |

| Basal ganglia hemorrhage | 0 | 1‡ |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 0 | 1 |

| Hypertensive encephalopathy | 0 | 1 |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage | 1 | 0 |

| Ischemic stroke | 1‡ | 0 |

| Syncope | 1† | 1† |

| Transient ischemic attack | 2† | 0 |

| Psychiatric | ||

| Visual hallucination | 0 | 1 |

| Suicidal ideation | 0 | 1 |

| Renal | ||

| Nephrolithiasis | 1 | 0 |

| Urine retention | 1 | 0 |

| Reproductive | ||

| Menorrhagia | 0 | 1 |

| Respiratory | ||

| Dyspnea | 1 | 0 |

| Aspiration pneumonia | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 36 | 32 |

Defined as any adverse event that occurred at any dose and resulted in death, a life-threatening adverse event, inpatient hospitalization or prolongation of an existing hospitalization, persistent or significant disability/incapacity, or a congenital anomaly. Values are presented as numbers (percentages) of participants experiencing the event at least once.

Judged to possibly be related to treatment. Only 1 of the 2 transient ischemic attacks was judged to be possibly related.

Deaths (1 of the 2 patients with sepsis died).

In 3 patients.

Appendix Table 2.

Changes in Other Measures From Baseline to the 3-Year Visit

| Measure | Isradipine |

Placebo |

LSM Adjusted Difference (95% CI) | P Value* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | Mean Observed Change (SD) | LSM Adjusted Change (95% CI) | Patients, n | Mean Observed Change (SD) | LSM Adjusted Change (95% CI) | |||

| Total UPDRS score to 1 y† | 169 | 4.75 (6.80) | 4.65 (3.59 to 5.70) | 165 | 5.42 (7.28) | 5.30 (4.25 to 6.35) | −0.66 (−2.09 to 0.77) | 0.37 |

| UPDRS PIGD score | 162 | 0.12 (0.33) | 0.12 (0.07 to 0.17) | 158 | 0.10 (0.33) | 0.10 (0.05 to 0.15) | 0.02 (−0.05 to 0.09) | 0.60 |

| UPDRS tremor score | 162 | 0.01 (0.34) | 0.00 (−0.05 to 0.05) | 158 | 0.02 (0.34) | 0.01 (−0.03 to 0.06) | −0.01 (−0.08 to 0.05) | 0.74 |

| Hoehn and Yahr stage | 162 | 0.11 (0.47) | 0.15 (0.09 to 0.22) | 159 | 0.24 (0.55) | 0.21 (0.15 to 0.28) | −0.06 (−0.15 to 0.03) | 0.195 |

| Beck Depression Inventory total score | 161 | 0.85 (3.91) | 0.77 (0.05 to 1.49) | 159 | 1.26 (5.09) | 1.34 (0.63 to 2.04) | −0.57 (−1.54 to 0.40) | 0.25 |

| Levodopa‡ | 162 | 298 (347) | 307 (257 to 356) | 159 | 296 (272) | 307 (259 to 355) | −0.20 (−66 to 66) | 0.99 |

| Cumulative levodopa‡ | 162 | 461 (542) | 471 (388 to 555) | 159 | 489 (510) | 508 (426 to 590) | −37 (−149 to 75) | 0.52 |

| Systolic blood pressure (SD), mm Hg§ | 162 | −6.01 (15.70) | −6.11 (−8.28 to −3.95) | 159 | 1.66 (15.33) | 1.03 (−1.10 to 3.15) | −7.14 (−10.05 to −4.23) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (SD), mm Hg§ | 162 | −4.04 (9.23) | −4.64 (−5.93 to −3.36) | 159 | −0.50 (9.30) | −0.71 (−1.96 to 0.55) | −3.94 (−5.66 to −2.22) | <0.001 |

LSM = least-squares mean; PIGD = postural instability and gait disorder; UPDRS = Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale.

For comparisons of LSMs (not adjusted for multiple comparisons).

Changes from baseline to the earlier of the 1-y visit or the determination of need for antiparkinson therapy.

Levodopa dose in milligrams at the 3-y visit. Cumulative levodopa dose in milligram-years through the 3-y visit.

Measured while patient was seated.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Disclosure forms from the Steering Committee for the Parkinson Study Group STEADY-PD III Investigators (who authored this work) can be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors/icmje/ConflictOfInterestForms.do?msNum=M19-2534.

Data Sharing Statement: The following data will be made available: complete deidentified study data set has been uploaded to NINDS clinical trial repository (www.ninds.nih.gov/Current-Research/Research-Funded-NINDS/Clinical-Research/Archived-Clinical-Research-Datasets).

Current author addresses and author contributions are available at Annals.org.

References

- 1.de Lau LM, Breteler MM. Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:525–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dorsey ER, Constantinescu R, Thompson JP, et al. Projected number of people with Parkinson disease in the most populous nations, 2005 through 2030. Neurology. 2007;68:384–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dodel RC, Singer M, Köhne-Volland R, et al. The economic impact of Parkinson’s disease: an estimation based on a 3-month prospective analysis. Pharmacoeconomics. 1998;14:299–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huse DM, Schulman K, Orsini L, et al. Burden of illness in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2005;20:1449–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lang AE, Espay AJ. Disease modification in Parkinson’s disease: current approaches, challenges, and future considerations. Mov Disord. 2018;33:660–77. doi: 10.1002/mds.27360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan CS, Guzman JN, Ilijic E, et al. ‘Rejuvenation’ protects neurons in mouse models of Parkinson’s disease. Nature. 2007;447:1081–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guzman JN, Sanchez-Padilla J, Wokosin D, et al. Oxidant stress evoked by pacemaking in dopaminergic neurons is attenuated by DJ-1. Nature. 2010;468:696–700. doi: 10.1038/nature09536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ilijic E, Guzman JN, Surmeier DJ. The L-type channel antagonist isradipine is neuroprotective in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;43:364–71. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parkinson Study Group. Phase II safety, tolerability, and dose selection study of isradipine as a potential disease-modifying intervention in early Parkinson’s disease (STEADY-PD). Mov Disord. 2013;28: 1823–31. doi: 10.1002/mds.25639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anekonda TS, Quinn JF. Calcium channel blocking as a therapeutic strategy for Alzheimer’s disease: the case for isradipine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1812:1584–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.08.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Becker C, Jick SS, Meier CR. Use of antihypertensives and the risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2008;70:1438–44. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000303818.38960.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pasternak B, Svanstrom H, Nielsen NM, et al. Use of calcium channel blockers and Parkinson’s disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2012; 175:627–35. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ritz B, Rhodes SL, Qian L, et al. L-type calcium channel blockers and Parkinson disease in Denmark. Ann Neurol. 2010;67:600–6. doi: 10.1002/ana.21937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biglan KM, Oakes D, Lang AE, et al. ; Parkinson Study Group STEADY-PD III Investigators. A novel design of a phase III trial of isradipine in early Parkinson disease (STEADY-PD III). Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2017;4:360–8. doi: 10.1002/acn3.412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hughes AJ, Ben-Shlomo Y, Daniel SE, et al. What features improve the accuracy of clinical diagnosis in Parkinson’s disease: a clinicopathologic study. Neurology. 1992;42:1142–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoehn MM, Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology. 1967;17:427–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fahn S, Elton R, Members of the UPDRS Development Committee. Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale In: Fahn S, Marsden CD, Calne DB, et al. , eds. Recent Developments in Parkinson’s Disease, Volume 2 Florham Park, NJ: Macmillan; 1987:153–64, 293304. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tomlinson CL, Stowe R, Patel S, et al. Systematic review of levodopa dose equivalency reporting in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2010;25:2649–53. doi: 10.1002/mds.23429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goetz CG. Movement Disorder Society-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): a new scale for the evaluation of Parkinson’s disease [Editorial]. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2010;166:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2009.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holloway RG, Shoulson I, Fahn S, et al. ; Parkinson Study Group. Pramipexole vs levodopa as initial treatment for Parkinson disease: a 4-year randomized controlled trial. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:1044–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pålhagen S, Heinonen E, Hagglund J, et al. ; Swedish Parkinson Study Group. Selegiline slows the progression of the symptoms of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2006;66:1200–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parkinson Study Group PRECEPT Investigators. Mixed lineage kinase inhibitor CEP-1347 fails to delay disability in early Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2007;69:1480–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White IR, Bamias C, Hardy P, et al. Randomized clinical trials with added rescue medication: some approaches to their analysis and interpretation. Stat Med. 2001;20:2995–3008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jankovic J, McDermott M, Carter J, et al. Variable expression of Parkinson’s disease: a base-line analysis of the DATATOP cohort. The Parkinson Study Group. Neurology. 1990;40:1529–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elm JJ, Goetz CG, Ravina B, et al. ; NET-PD Investigators. A responsive outcome for Parkinson’s disease neuroprotection futility studies. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hart RG, Pearce LA, Ravina BM, et al. Neuroprotection trials in Parkinson’s disease: systematic review. Mov Disord. 2009;24:647–54. doi: 10.1002/mds.22432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elm JJ; NINDS NET-PD Investigators. Design innovations and baseline findings in a long-term Parkinson’s trial: the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Exploratory Trials in Parkinson’s Disease Long-Term Study-1. Mov Disord. 2012;27:1513–21. doi: 10.1002/mds.25175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marras C, Gruneir A, Rochon P, et al. Dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers and the progression of parkinsonism. Ann Neurol. 2012;71:362–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.22616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.