Abstract

The aim of this review is to provide an overview of different functional cardiac CT techniques which can be used to supplement assessment of the coronary arteries to establish the significance of coronary artery stenoses. We focus on cine-CT, CT-FFR, CT-myocardial perfusion and how developments in machine learning can supplement these techniques.

Introduction

Cardiac CT is a highly accurate test to detect the presence of coronary atherosclerosis and to precisely quantify coronary plaque burden. 30 years ago, Agatston et al published the now eponymous and famous method to quantify the presence and amount of coronary calcium,1 and many studies have conclusively shown the strong relationship between the presence of coronary calcium and the risk for future coronary events.2,3 Since the early years of this millennium, aided by the development of multidetector row CT scanners, researchers have widened the focus to also visualize the coronary artery lumen and non-calcified coronary plaque using various coronary CT angiography (CCTA) techniques.4 In the past decade, CCTA has further matured and state of the art scanners with which the heart and coronary tree can be precisely depicted in a single short breath hold are now available from all major hardware vendors.

At the same time, it has also become clear that the presence of coronary plaque, even when there is substantial luminal narrowing, does not necessarily imply the presence of a significant pressure gradient or flow limitation5 and by extension, the need for invasive intervention. Even in patients with proven moderate-to-severe ischemia and stable chest pain, the indication for invasive intervention has recently been questioned.6 The inability of CCTA to precisely judge the hemodynamic significance of coronary artery stenoses using the degree of luminal narrowing alone has sparked the search for alternative methods to improve this assessment. Approaches to bridge this gap range from taking into account the type of coronary plaque to examining myocardial contrast enhancement using the principles of tracer kinetics, and more recently, assessment of cardiac motion and application of advanced computational fluid dynamics modeling as well as machine learning (ML) techniques. Below we summarize these efforts and review their clinical potential.

Functional CT – overview of different techniques

In this review, we will consider three different functional cardiac CT techniques: 1) cine CT to assess cardiac motion; 2) estimation of pressure gradients across coronary stenoses using computational fluid dynamics or other methods; and 3) CT myocardial perfusion. We will not focus on coronary plaque assessment, as this has been covered elsewhere in this special issue by Bing et al.7

Cine CT

Since its introduction, retrospectively ECG-gated CT has allowed for evaluation of the heart over the entire cardiac cycle. This multiphasic acquisition technique provides dynamic views (i.e., cine-CT or 4D-CT) for functional analyses during both systole and diastole. In patients with chest pain, retrospectively gated CCTA can provide additional information regarding cardiac function without the use of additional contrast medium, radiation dose or additional tests. CT may also provide functional information in symptomatic patients with (relative) contraindication for cardiac MRI (CMR). A disadvantage of multiphasic CT is the radiation dose, which can range between 6 and 15 mSv depending on the CT acquisition protocol (e.g., use of dose modulation or low tube voltage).8

Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) is the most universal tool to evaluate left ventricular function and has been used as diagnostic and prognostic marker for treatment decision-making. CMR provides high spatial and temporal resolution and is the gold standard for LVEF assessment. Nevertheless, over the last years, multiple studies have proven feasibility and accuracy of both CT-derived LVEF9,10 and right ventricular ejection fraction (RVEF),9–12 in (acceptable) accordance with CMR results.

Assessment of regional LV function by CT in acute chest pain showed increased sensitivity and improved detection of acute coronary syndrome compared to CCTA alone in a subanalysis of the ROMICAT trial.13 Cine CT provides information on wall motion, as reconstructed cine-loop images can visualize myocardial contraction and relaxation throughout the cardiac cycle. In patients with ischemic heart disease, CT can be used as alternative tool to assess global and regional wall motion abnormalities.14,15 Likewise, the combination of CCTA and functional information may be helpful in patients without chest pain but increased risk for coronary artery disease (CAD) and LV dysfunction, such as in oncologic patients with suspected cardiotoxicity or radiation-induced CAD.16–18 With further improvement of CT acquisition techniques, ventricular diastolic dysfunction and atrial function may potentially be depicted as well.19–21

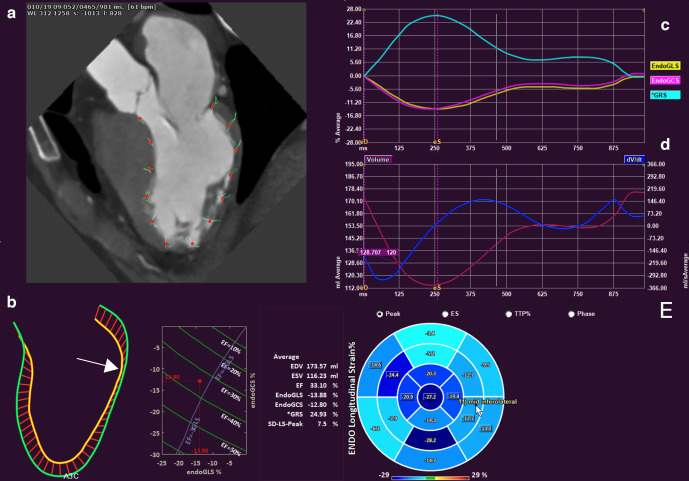

Cine-CT can provide information on myocardial mass, wall thickness and wall motion, by delineation and tracking of the endocardial and epicardial boundaries throughout the cardiac cycle.22 Furthermore, myocardial strain has emerged as valuable parameter for assessment of global LV function and has shown to be a valuable diagnostic and prognostic tool.23,24 Myocardial strain represents the deformation of the myocardial fibers over the cardiac cycle produced by stress and can be measured with cine-CT (Figure 1). Typically, three main spatial directions are evaluated: longitudinal, circumferential and radial strain. Global longitudinal strain (LGS) has shown to be the most consistent strain measure.25 Whereas echocardiography and CMR are gold standard for strain imaging, CT has shown good correlation with 2D-echocardiography for left atrium26 and left ventricle strain assessment26–28 and moderate-good correlation with CMR.29 To the best of our knowledge, no studies have been published on the incremental value of CT-derived strain for evaluation of patients with suspected or known CAD using FFR as the reference standard. In early TAVR studies, CT strain was a predictor for mortality and composite outcome after TAVR in patients with normal LVEF.30 In few other clinical studies, CT-strain was evaluated in patients with myocardial infarction31 and congestive heart failure.32 Since CT-strain is a relatively new tool and clinically studied in only a selected group of patients, reference values are needed.33,34 Furthermore, different techniques to measure strain have been published and their clinical impact has yet to be evaluated.35–37

Figure 1.

Cardiac strain analysis based on multidetector row CT feature tracking (QStrain, Medis BV, Leiden, The Netherlands). The patient had suffered a lateral wall infarct. Upper left panel shows features tracked over the cardiac cycle (a). The lower left panel (b) shows the excursion of the endocardial contour over the cardiac cycle with pink denoting end-diastole and yellow denoting end-systole. Note lack of motion of the lateral wall (arrow). The line plot enables simultaneous visualization of longitudinal and circumferential strain as well as ejection fraction. A normally functioning heart would be positioned in the lower left corner of the graph. Upper right panel (c) shows the global longitudinal (EndoGLS), circumferential (EndoGCS) and radial (*GRS) strain curves over the cardiac cycle. The middle right panel (d) shows the volume of the left ventricle over the cardiac cycle (purple curve) as well its derivative (blue curve). The lower right panel shows a bullseye plot of the peak endocardial longitudinal strain per cardiac segment. See Supplementary Video 1 for a cine loop video of the beating heart. Data are courtesy of DrErasmo de la Pena-Almaguer, Tecnologico de Monterrey, Mexico.

Fractional flow reserve CT

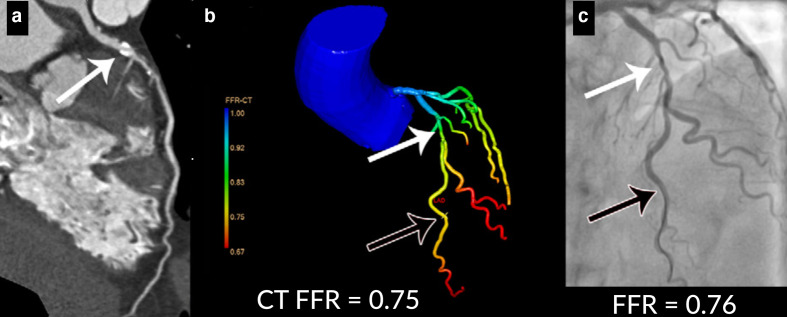

Whereas CCTA has high diagnostic performance for ruling out epicardial CAD in low and intermediate risk patients, grading the severity of coronary stenosis and assessing hemodynamic significance based on anatomical information alone is challenging. In patients with stable chest pain, it has been shown that even severe coronary artery obstruction results in functional obstruction and myocardial ischemia in only a subset of patients.38 Hence, additional assessment of hemodynamic significance of coronary artery stenosis may be required in patients with known CAD and/or stable chest pain. The standard of reference for assessment of hemodynamic significance of coronary stenosis is invasive fractional flow reserve (FFR) pressure wire measurement during invasive coronary angiography (ICA) studies. Invasive FFR is an index of the functional severity of a coronary stenosis and is defined as the ratio between the mean distal coronary pressure and the mean aortic pressure at hyperemia and represents the fraction of maximal blood flow despite the stenosis.39 FFR-guided revascularization procedures have shown to reduce the rate of (MACE) events and revascularization therapies and costs.40,41 Recent advances in computational flow dynamics (CFD) have enabled non-invasive detection of hemodynamic significant stenosis using anatomical CT data only. With CT-derived fractional flow reserve (FFR-CT), CFD techniques are applied to simulate coronary blood flow and obtain functional information.42,43 Several elemental components are needed to run these simulations, including accurate anatomical segmentation, setting boundary conditions and modeling (micro)vascular resistance and compliance. Various FFR-CT algorithms have been investigated. HeartFlow Inc. (Redwood City, California, United States of America) was first to present commercially available FFR-CT for CAD evaluation, showing improved diagnostic accuracy in the detection of hemodynamic significant CAD in the DISCOVER-FLOW, DEFACTO and NXT trails.44–46 HeartFlow is an offsite segmentation and analysis platform, which operates on complete three-dimensional flow simulations of the coronary artery system, requiring extreme computational power and time. Additional drawbacks are that only high-quality CCTA images without motion or step-artefacts can be used for precise anatomic modeling, in addition to costs.47 The initial HeartFlow trials were followed by publications on FFRCT algorithms developed by Siemens Healthineers (cFFR, Siemens HealthineersGmbH, Forchheim, Germany), who employ slightly altered CFD methods allowing time-reduced, onsite evaluation using regular workstations.48–51 Subsequently, other vendors including Canon Medical Systems (formerly Toshiba Medical Systems Corp.),52–55 PhilipsHealthcare56–59 and various research groups60–70 presented onsite FFR-CT algorithms (Figure 2). A recent meta-analysis showed similar performance for offsite and onsite FFR-CT CFD algorithms.5 An overview of studies addressing the diagnostic accuracy of CT-derived FFR and CT perfusion is presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Figure 2.

Example of CT angiography-derived fractional flow reserve (CT FFR) analysis (FFR-CT, IntelliSpace Portal, version 9.0.1.20490; Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands). In panel (a), a curved multiplanar reformation of the CT scan is shown with a 50–69% stenosis in the LAD (white arrow). In (b), a anatomic model of the coronary tree is shown with a 50–69% stenosis in the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery (white arrow) leading to a calculated FFR value of 0.75 (black arrow). In panel (c), the corresponding invasive coronary angiogram is shown, which confirmed the presence of moderate stenosis (white arrow) with a significant pressure drop distal to the stenosis resulting in an FFR value of 0.76 (black arrow).

Overall, FFR-CT showed high diagnostic accuracy for hemodynamic significant coronary stenosis, particularly when combined with CTA.5,71 At vessel level, pooled sensitivity and specificity were 0.85 and 0.78 (FFR-CT) and 0.76 and 0.80 (FFR-CT and CTA), respectively.5 At patient level, pooled sensitivity and specificity were 0.89 and 0.76 (FFR-CT), considerably higher than CTA alone. Another meta-analysis presented a pooled FFR-CT sensitivity and specificity of 0.89 and 0.71 for patient, and 0.85 and 0.82 for vessel level.71 In patients with three-vessel disease, FFR-CT resulted in reclassification to a lower risk category in up to 30% of patients.72 It is also important to take into account the degree of coronary calcifications, as this may influence diagnostic accuracy.73 In addition, it is important to consider the absolute value of the FFR-CT result, because the diagnostic accuracy of FFR-CT varies markedly across the spectrum of disease, as was shown in a recent systematic review by Cook et al.74

At present, several trials in patients with suspected stable chest pain and intermediate degrees of stenosis have shown FFR-CT-guided treatment decisions to result in lower rates of negative ICA studies and lower costs,75–78 with no major adverse clinical events within 90 days in patients with FFR-CT ≥0.80 in the ADVANCE registry.78 The clinical impact of FFR-CT-guided treatment decisions in patients with multivessel disease has yet to be investigated. Preliminary results have been presented on the HeartFlow Planner, a novel FFR-CT tool that allows for geometric modeling, which could aid in predicting the expected effect of percutaneous coronary interventions in significant coronary stenosis.79

CT myocardial perfusion

As discussed, the presence of atherosclerotic CAD does not necessarily imply functional coronary artery obstruction or myocardial ischemia. In patients with intermediate risk and/or indeterminate hemodynamic significance of coronary stenosis functional testing is indicated. Several non-invasive imaging techniques have become routine for the evaluation of patients with chronic chest pain to detect presence or absence of myocardial ischemia. As stated in recent ESC guidelines, the appropriate diagnostic test should be selected based on the clinical likelihood of obstructive CAD.80 Possible imaging modalities include stress-echocardiography, single-photon emission CT (SPECT), PET or CMR. ICA (with or without FFR) should be reserved for patients with high event risk or for those with contradictory or inconclusive non-invasive imaging results.

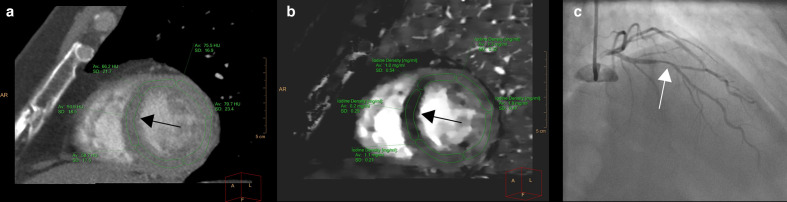

Myocardial CT perfusion (CTP) is a relatively novel clinical imaging technique based on visualizing and quantifying the presence of iodinated contrast medium in the myocardium in rest and under pharmacologic stress conditions. The distribution of contrast bolus can be visualized either at a single point in time (‘static’ CTP), or, analogous to CMR perfusion, followed over time to show relative hypoperfusion in areas of ischemia or infarction. CTP images can be acquired either during one cardiac phase (static) or during multiple phases (dynamic). Most frequently, static CTP is used and an advantage of this method is the low radiation dose (3–10 mSv),81 whereas disadvantages include the need for precise contrast bolus timing, and restrictions to qualitative or semi-quantitative perfusion analysis only. An infrequently used static CTP technique to obtain perfusion information using CT is dual energy CT (DECT) perfusion. Acquisitions are generally performed with protocols similar to static perfusion. With DECT systems, image contrast can be increased by virtual monochromatic reconstructions at low keV, and likewise, image noise can be reduced at high keV reconstructions. Furthermore, reconstructed iodine maps – based on material decomposition features – can potentially be used to differentiate between normal and ischemic/infarcted myocardium (Figure 3).82,83 The advantages and disadvantages of the different CT perfusion techniques are summarized in Table 1. The reported sensitivity and specificity of static CTP in comparison with invasive FFR ranged between 71–95% and 84–95%, respectively. For DECT perfusion, reported sensitivity and specificity in comparison with ICA ranged between 67–95% and 50–95%, respectively.84 Dynamic CTP allows for qualitative, semi-quantitative or fully quantitative analysis with reconstruction of time attenuation curves (TAC). In contrast to static CTP, complete quantitative analysis with dynamic CTP may detect balanced or microvascular ischemia.85,86 Reduced diagnostic image quality in presence of beam hardening artifacts can affect both static and dynamic CTP but multiphase acquisitions often provide the opportunity to select images with reduced (beam hardening) artifacts, although dynamic imaging in general is more prone to motion artifacts. Important drawbacks of dynamic CTP are not only higher radiation dose with conventional CT settings (typically between 10 and 18 mSv81) but also the more challenging acquisition protocols and complex analysis techniques.5,84,87 In order to save dose, a resting CTP acquisition is often omitted. Although results are promising, dynamic CTP is still mostly limited to expert centers and a handful of clinical institutions in Asia.

Figure 3.

Example of spectral CT for improved detection of myocardial perfusion defect. Left panel shows conventional Hounsfield unit (HU) reconstruction in the short-axis orientation with slightly decreased HU values in the septum (black arrow). The iodine density reconstructions (b) show the perfusion defect much more clearly (black arrow) by plotting the iodine concentration in the different parts of the myocardium. Note the fivefold to ninefold lower iodine concentration in the septum. Invasive evaluation confirmed the presence of a 50–69% stenosis in the proximal left anterior descending coronary arrow (white arrow). The invasively measured FFR value was 0.72.

Table 1.

Summary of the advantages and disadvantages of different CT perfusion techniques

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|

| Static CT perfusion | Low radiation dose | Timing of contrast bolus essential |

| Clinically available – most experience | Susceptible to beam hardening artifacts | |

| Can be derived from same dataset as CCTA | Only qualitative or semi-quantitative perfusion analysis | |

| Dynamic CT perfusion | Qualitative, semi-quantitative or fully quantitative analysis measurements possible | Prone to motion artifacts (caused by motion of the patient or the heart) |

| Able to detect balanced or microvascular ischemia | Higher radiation dose | |

| Opportunity to select images with reduced (beam hardening) artifacts | More challenging acquisition protocols and complex analysis techniques | |

| Mostly used for research purposes | ||

| Dual-energy CT perfusion | Possibility to increase image contrast by virtual monochromatic reconstructions | Challenging acquisition protocols and complex analysis techniques |

| Image noise can be reduced | Only used for research purposes | |

| Reconstructed iodine maps can be used to differentiate between normal and ischemic/infarcted myocardium | ||

| Improves tissue characterization |

Improves tissue characterization

CTP acquisition protocols are dependent on available CT systems, related spatial and temporal resolution and software. Static CTP can be acquired during systole or diastole, although most studies have been performed in diastole, as with regular CCTA.84 No consensus or guideline exists stating whether rest or stress imaging should be performed first. The order of acquisition may depend on the clinical indication for functional imaging, the clinical likelihood of obstructive CAD and/or the result of coronary calcium study, typically preceding CTA/CTP. In patients without obstructive CAD on rest imaging, stress CTP could be omitted. A potential drawback of performing rest imaging first is the (often) need for administration of beta-blockers to reduce heart rates, particularly with static CTP. This may result in underestimation of hypo-perfused segments, especially when contrast medium residue from rest CTP is still present in the myocardium. Therefore, sufficient time (at least 10–20 min) should be scheduled between rest and stress acquisitions. Stress perfusion is performed by administration of pharmacologic agents (typically adenosine or regadenoson), which requires a dedicated team, proper patient selection and study preparation (e.g., ECG studies and monitoring). Scheduled delay between rest and stress imaging will also reduce the risk of hypotension induced by nitroglycerine (administered at rest CTA/CTP) and stress agents for stress CTP.84

Multiple clinical studies have been published on the diagnostic performance of either static or dynamic CTP for the detection of hemodynamic significant CAD in comparison with SPECT, CMR or ICA. A selection of CTP studies using invasive FFR as reference test showed a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 0.81 and 0.85 on vessel level, respectively.5 For CTP complementary to CTA, this increased to 0.82 and 0.88, respectively. On patient level, pooled sensitivity and specificity were 0.83 and 0.79 (CTP) and 0.89 and 0.81 (CTP and CTA), respectively. In patients with coronary stents, CTP in addition to CCTA has shown to increase the diagnostic performance for evaluation of in-stent stenosis.88 An overview of the diagnostic studies performed on CTP can be found in Supplementary Table 2. First results on the use of CTA in combination with CTP in patients with acute onset chest pain showed a reduction of ICA and revascularization rates compared with CTA alone, without significant differences for composite endpoints at 1.5 years.89

Complementary role of functional CT over morphological assessment

Several studies have demonstrated the high negative predictive of CCTA. It can be used to safely rule out CAD in low and intermediate risk patients with stable angina and suspected chronic coronary syndrome.90 Nevertheless, the correlation between the morphological assessment on CCTA and functional significance as assessed by invasive FFR is moderate.91 The reference standards for functional assessment according to the guidelines are stress-ECG, SPECT and PET, although none of these tests is capable of assessing all relevant functional and anatomical features simultaneously.80,92 A combined strategy in which both anatomical as well as functional features are assessed with CT might fill this gap and improve the workflow for diagnosing CAD. If obstructive CAD is not detected by CCTA, no further functional assessment is needed, whereas functional assessment can be performed when obstructive or non-evaluable lesions are observed. In general, these strategies improve the positive predictive value without decreasing the NPV and increase the specificity while maintaining the sensitivity.5,71,93–97 These results imply that a combined strategy improves the diagnostic workup and management of CAD. To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies that have compared combined assessment with CT-FFR and CTP to anatomical evaluation alone.

Guideline recommendations

The European Society for Cardiology (ESC) recently renewed their guideline for chronic coronary syndrome in 2019 in which CCTA has a more prominent role as first-line test to diagnose CAD in symptomatic patients (I-B recommendation).80 Functional imaging is recommended if CCTA has shown CAD or is non-conclusive. No specific recommendations are made regarding the preferred functional tests. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline98 suggests, in addition to the recommendations in the ESC-guideline, that HeartFlow FFR-CT can be used as functional test since it is safe, has high diagnostic accuracy and may avoid the need for invasive diagnostics.

The role of machine learning in advancing functional CT of the heart

In the past few years, the field of machine learning (ML) has made enormous progress. Fueled by the availability of cheap graphics processing unit (GPU) hardware as well as open source programming tools, a host of studies have been published that show the potential of ML to improve assessment of CAD.

An interesting proof-of-concept study by Mannil and co-workers found that combining non-contrast CT myocardial texture analysis with ML enabled identification of patients with acute or chronic MI from controls.99 ML can also aid in the identification of flow-limiting coronary artery stenoses. Coenen and co-workers found that a proprietary on-site workstation ML approach that applies a combination of pattern recognition and computational learning to derive FFR100 improved assessment of the hemodynamic severity of coronary stenosis compared to a prior hybrid CFD approach that couples a reduced-order model for non-stenotic vessel sections with a dedicated stenosis model for the narrowed regions. Both on a per-vessel and per-patient level, the diagnostic accuracy and positive predictive value of CTA improved by adding ML-based FFR-CT.101 A more recent study by Li et al compared the same ML algorithm to dynamic CTP in 86 patients with stable angina and found that CTP was more accurate.102 Zreik et al used a DL approach to determine the functional significance of coronary stenosis in resting CCTA by employing deep learning analysis of the LV myocardium alone. The results demonstrate that automatic DL analysis of the LV myocardium in a single CCTA scan acquired at rest, without assessment of the anatomy of the coronary arteries, can be used to identify patients with functionally significant coronary artery stenosis with reasonable accuracy.103,104 This approach was extended in subsequent work with an integrated DL solution for fully automated coronary artery segmentation, identification of coronary plaques and determination of the hemodynamic significance of coronary stenoses using a multitask recurrent convolutional neural network. For detection of stenosis and determination of its anatomical significance, the method achieved an accuracy of 0.80.103 Furthermore, several studies are ongoing in which the ability of ML to improve CT myocardial perfusion analysis are being investigated.105,106

Challenges and ongoing trials

Overall, the evidence for functional CT techniques seems promising but some challenges and limitations need to be addressed. Although cine-CT provides useful information, to the best of our knowledge no studies have been published linking CT abnormalities as detected with cine-CT strain analysis to the presence of invasively proven significant CAD. This represents an important knowledge gap and should be investigated. Clinically, however, the use of cine CT will be limited to patients who cannot undergo prospectively triggered CCTA because of irregular or high heart rates or equipment limitations.

For FFR-CT, there is a substantial body of evidence regarding its efficacy, but most of the published studies suffered from selection bias. Patients with co-morbidities were excluded from analysis as well as lesions in vein grafts or stents. This has resulted in an overestimation of the diagnostic performance and in limitations on the generalizability. Second, all studies performed so far were observational studies. No randomized controlled trials have been published comparing the conventional diagnostic workflow vs (additional) FFR–CT for clinical endpoints such as MACE. Observational FFR-CT studies, however, showed low adverse event rates in patients deferred from invasive FFR and revascularization therapy, supporting its safety to stratify patients.75,76,78,107 Third, the diagnostic performance of FFR-CT strongly depends on the image quality (IQ). Despite most studies followed dedicated acquisition protocols, suboptimal IQ resulted in exclusion rates varying between 10 and 25%.44–46,78,108 The impact of IQ alterations on the diagnostic performance of FFR-CT has not been assessed. Fourth, no information is yet available on the cost-effectiveness of FFR-CT-based treatment strategies. For this, two, currently active, randomized controlled trials have been designed: the FORECAST trial (Fractional Flow Reserve Derived from Computed Tomography Coronary Angiography in the Assessment and Management of Stable Chest Pain, NCT03187639) and the PRECISE trial (Prospective Randomized Trial of the Optimal Evaluation of Cardiac Symptoms and Revascularization, NCT03702244). Both of these trials are supported by the FFR-CT vendor HeartFlow and explicitly do not include alternative methods for the determination of FFR. Therefore, these trials are inherently biased and do not represent the choices available to healthcare practitioners in clinical routine. No clinical trials assessing FFR-CT by other vendors could be identified. Clinically, application of FFR-CT will be limited to countries with established reimbursement or hospitals participating in clinical trials.

With regard to CTP, we discussed the increased radiation dose for dynamic protocols as a significant hurdle toward clinical deployment. The benefits and drawbacks of CTP from multiple different perspectives will be investigated by two randomized clinical trials: The CTP-PRO study (Impact of Stress CT Myocardial Perfusion on Downstream Resources and Prognosisin Patients With Suspected or Known Coronary Artery Disease, NCT03976921) and the PERFUSE RCT (Prospective Evaluation of Myocardial Perfusion Computed Tomography Trial, NCT02208388). 2000 intermediate and high-risk patients will be included in the CTP-PRO trial to evaluate a combined CTP and CCTA approach for suspected CAD, and the decision to perform static stress CTP or dynamic stress CTP will be based on local practice and technology.106 The impact of CTP will be measured in terms of clinical decision-making, resource utilization and outcomes in a broad variety of geographic areas and patient subgroups. The PERFUSE RCT aims to evaluate the impact of CTP-guided revascularization on MACE at 1 year in 1000 patients with suspected stable CAD. Another issue that needs to be addressed when using CTP is the variability in the quantification approach (type of tracer kinetic model, hybrid approach etc.) and the variety in population used for research. These issues need to be settled before the technique will be applied in clinical practice on a routine basis.

Another important question concerns the role of ML. Rather than being used as a stand-alone technique, it is likely that ML can complement the approaches listed above and improve accuracy of CT-FFR as well as CTP approaches. This will be investigated in the ongoing CLARITY study.105

Recently, the ISCHEMIA trial (International Study of Comparative Health Effectiveness with Medical and Invasive Approaches) found no reduction in major cardiac events with invasive coronary revascularization therapy compared with medical therapy in patients with stable chest pain and moderate-to-severe ischemia.6 The MR-INFORM trial (Myocardial Perfusion CMR vs Angiography and FFR to Guide the Management of Patients with Stable Coronary Artery Disease) showed a reduction in invasive coronary revascularization and non-inferiority to invasive FFR for major cardiac events.109 Cost-effectiveness studies will provide more guidance on optimal diagnostic test combinations and treatment strategies.

Conclusions

Several cardiac CT techniques can complement analysis of coronary calcium and assessment of the presence and degree of coronary stenosis. Cardiac cine-CT, non-invasive estimation of FFR with various approaches as well as CT myocardial perfusion are all promising approaches for improved identification of patients with flow-limiting CAD. Application of machine learning will improve all of these techniques further.

Contributor Information

Joyce Peper, Email: j.peper@antoniusziekenhuis.nl.

Dominika Suchá, Email: d.sucha@umcutrecht.nl.

Martin Swaans, Email: m.swaans@antoniusziekenhuis.nl.

Tim Leiner, Email: t.leiner@umcutrecht.nl.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, Zusmer NR, Viamonte M, Detrano R. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 1990; 15: 827–32. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90282-T [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xie X, Zhao Y, De Bock GH, De Jong PA, Mali WP, Oudkerk M, et al. Validation and prognosis of coronary artery calcium scoring in nontriggered thoracic computed tomography: systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2013; 6: 514–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaikriangkrai K. Palamaner Subash Shantha G, Jhun HY, Ungprasert P, Sigurdsson G, Nabi F, et al. prognostic value of coronary artery calcium score in acute chest pain patients without known coronary artery disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med 2016; 68: 659–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meinel FG, Bayer II RR, Zwerner PL, De Cecco CN, Schoepf UJ, Bamberg F. Coronary computed tomographic angiography in clinical practice. Radiol Clin North Am 2015; 53: 287–96. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2014.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Celeng C, Leiner T, Maurovich-Horvat P, Merkely B, de Jong P, Dankbaar JW, et al. Anatomical and Functional Computed Tomography for Diagnosing Hemodynamically Significant Coronary Artery Disease. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 2019; 12: 1316–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2018.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maron DJ, Hochman JS, Reynolds HR, Bangalore S, O’Brien SM, Boden WE, et al. Initial invasive or conservative strategy for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1395–407. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bing R, Loganath K, Adamson P, Newby D, Moss A. Imaging patients with stable chest pain special feature : Review Article Vulnerable plaque imaging using 18 F- sodium fluoride positron emission tomography. Br J Radiol 2019; 92(September). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alkadhi H, Leschka S. Radiation dose of cardiac computed tomography – what has been achieved and what needs to be done. Eur Radiol 2011; 21: 505–9. doi: 10.1007/s00330-010-1984-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maffei E, Messalli G, Martini C, Nieman K, Catalano O, Rossi A, et al. Left and right ventricle assessment with cardiac CT: validation study vs. cardiac Mr. Eur Radiol 2012; 22: 1041–9. 2012/01/25. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2345-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takx RAP, Moscariello A, Schoepf UJ, Barraza JM, Nance JW, Bastarrika G, et al. Quantification of left and right ventricular function and myocardial mass: comparison of low-radiation dose 2nd generation dual-source CT and cardiac MRI. Eur J Radiol 2012; 81: e598–604. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu H, Wang X, Diao K, Huang S, Liu H, Gao Y, et al. Ct compared to MRI for functional evaluation of the right ventricle: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radiol 2019; 29: 6816–28. 2019/05/28. doi: 10.1007/s00330-019-06228-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamasaki Y, Nagao M, Yamamura K, Yonezawa M, Matsuo Y, Kawanami S, et al. Quantitative assessment of right ventricular function and pulmonary regurgitation in surgically repaired tetralogy of Fallot using 256-slice CT: comparison with 3-tesla MRI. Eur Radiol 2014; 24: 3289–99. 2014/08/13. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3344-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seneviratne SK, Truong QA, Bamberg F, Rogers IS, Shapiro MD, Schlett CL, et al. Incremental diagnostic value of regional left ventricular function over coronary assessment by cardiac computed tomography for the detection of acute coronary syndrome in patients with acute chest pain. Circulation 2010; 3: 375–83. 2010/05/21. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.109.892638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cury RC, Nieman K, Shapiro MD, Butler J, Nomura CH, Ferencik M, et al. Comprehensive assessment of myocardial perfusion defects, regional wall motion, and left ventricular function by using 64-section multidetector CT. Radiology 2008; 248: 466–75. 2008/07/22. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2482071478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.SM K, Kim YJ, Park JH, Choi NM. Assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction and regional wall motion with 64-slice multidetector CT: a comparison with two-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography. Br J Radiol. 2010; 83: 28–34. 2009/06/24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Layoun ME, Yang EH, Herrmann J, Iliescu CA, Lopez-Mattei JC, Marmagkiolis K, et al. Applications of cardiac computed tomography in the Cardio-Oncology population. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2019; 20: 47. 2019/05/06. doi: 10.1007/s11864-019-0645-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Leeuwen-Segarceanu EM, Bos W-JW, Dorresteijn LDA, Rensing BJWM, der Heyden JASvan, Vogels OJM, et al. Screening Hodgkin lymphoma survivors for radiotherapy induced cardiovascular disease. Cancer Treat Rev 2011; 37: 391–403. 2011/02/22. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lancellotti P, Nkomo VT, Badano LP, Bergler-Klein J, Bogaert J, Davin L, et al. Expert consensus for multi-modality imaging evaluation of cardiovascular complications of radiotherapy in adults: a report from the European association of cardiovascular imaging and the American Society of echocardiography. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2013; 14: 721–40. 2013/07/13. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jet123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yun C-H, Sun J-Y, Templin B, Lin S-H, Chen K-M, Wu T-H, et al. Improvements in left ventricular diastolic mechanics after Parachute device implantation in patients with ischemia heart failure: a cardiac computerized tomographic study. J Card Fail 2017; 23: 455–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2017.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wen Z, Ma H, Zhao Y, Fan Z, Zhang Z, Choi SI, et al. Left ventricular diastolic dysfunction assessment with Dual-Source CT. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0127289. 2015/05/21. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boogers MJ, van Werkhoven JM, Schuijf JD, Delgado V, El-Naggar HM, Boersma E, et al. Feasibility of diastolic function assessment with cardiac CT: feasibility study in comparison with tissue Doppler imaging. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011; 4: 246–56. 2011/03/19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Truong QA, Szymonifka J, Picard MH, Thai W-ee, Wai B, Cheung JW, et al. Utility of dual-source computed tomography in cardiac resynchronization therapy—DIRECT study. Heart Rhythm 2018; 15: 1206–13. 2018/03/25. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.03.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalam K, Otahal P, Marwick TH. Prognostic implications of global LV dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of global longitudinal strain and ejection fraction. Heart 2014; 100: 1673–80. 2014/05/27. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-305538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Voigt J-U, Cvijic M. 2- and 3-dimensional myocardial strain in cardiac health and disease. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 2019; 12: 1849–63. 2019/09/07. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2019.01.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amzulescu MS, De Craene M, Langet H, Pasquet A, Vancraeynest D, Pouleur AC, et al. Myocardial strain imaging: review of general principles, validation, and sources of discrepancies. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2019; 20: 605–19. 2019/03/25. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jez041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szilveszter B, Nagy AI, Vattay B, Apor A, Kolossváry M, Bartykowszki A, et al. Left ventricular and atrial strain imaging with cardiac computed tomography: validation against echocardiography. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2019;. 2019/12/21. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2019.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ammon F, Bittner D, Hell M, Mansour H, Achenbach S, Arnold M, et al. CT-derived left ventricular global strain: a head-to-head comparison with speckle tracking echocardiography. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2019; 35: 1701–7. 2019/04/07. doi: 10.1007/s10554-019-01596-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marwan M, Ammon F, Bittner D, Röther J, Mekkhala N, Hell M, et al. CT-derived left ventricular global strain in aortic valve stenosis patients: a comparative analysis pre and post transcatheter aortic valve implantation. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2018; 12: 240–4. 2018/03/03. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2018.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miskinyte E, Bucius P, Erley J, Zamani SM, Tanacli R, Stehning C, et al. Assessment of global longitudinal and circumferential strain using computed tomography feature tracking: intra-individual comparison with CMR feature tracking and myocardial tagging in patients with severe aortic stenosis. JCM 2019; 8: 1423. 2019/09/13. doi: 10.3390/jcm8091423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fukui M, Xu J, Thoma F, Sultan I, Mulukutla S, Elzomor H, et al. Baseline global longitudinal strain by computed tomography is associated with post transcatheter aortic valve replacement outcomes. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2019;. 2019/12/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanabe Y, Kido T, Kurata A, Sawada S, Suekuni H, Kido T, et al. Three-Dimensional maximum principal strain using cardiac computed tomography for identification of myocardial infarction. Eur Radiol 2017; 27: 1667–75. 2016/08/20. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4550-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buss SJ, Schulz F, Mereles D, Hosch W, Galuschky C, Schummers G, et al.;2013/12/26 Quantitative analysis of left ventricular strain using cardiac computed tomography. Eur J Radiol 2014; 83: e123–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.11.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peled Z, Lamash Y, Carasso S, Fischer A, Agmon Y, Mutlak D, et al. Automated 4-dimensional regional myocardial strain evaluation using cardiac computed tomography. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2020; 36: 149–59. doi: 10.1007/s10554-019-01696-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cho YH, Kang J-W, Choi SH, Yang DH, Anh TTX, Shin E-S, et al. Reference parameters for left ventricular wall thickness, thickening, and motion in stress myocardial perfusion CT: global and regional assessment. Clin Imaging 2019; 56(February): 81–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2019.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gupta V, Lantz J, Henriksson L, Engvall J, Karlsson M, Persson A, et al. Automated three-dimensional tracking of the left ventricular myocardium in time-resolved and dose-modulated cardiac CT images using deformable image registration. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2018; 12: 139–48. 2018/02/07. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2018.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lamash Y, Fischer A, Carasso S, Lessick J. Strain analysis from 4-d cardiac CT image data. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2015; 62: 511–21. 2014/09/25. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2014.2359244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tavakoli V, Sahba N. Cardiac motion and strain detection using 4D CT images: comparison with tagged MRI, and echocardiography. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2014; 30: 175–84. 2013/10/10. doi: 10.1007/s10554-013-0305-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meijboom WB, Van Mieghem CA, van Pelt N, Weustink A, Pugliese F, Mollet NR, et al. Comprehensive assessment of coronary artery stenoses: computed tomography coronary angiography versus conventional coronary angiography and correlation with fractional flow reserve in patients with stable angina. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008; 52: 636–43. 2008/08/16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pijls NHJ, de Bruyne B, Peels K, van der Voort PH, Bonnier HJRM, Bartunek J, et al. Measurement of fractional flow reserve to assess the functional severity of coronary-artery stenoses. N Engl J Med 1996; 334: 1703–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199606273342604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fearon WF, Bornschein B, Tonino PAL, Gothe RM, Bruyne BD, Pijls NHJ, et al. Economic evaluation of fractional flow Reserve–Guided percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with multivessel disease. Circulation 2010; 122: 2545–50. 2010/12/04. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.925396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tonino PAL, De Bruyne B, Pijls NHJ, Siebert U, Ikeno F, van `t Veer M, et al. Fractional flow reserve versus angiography for guiding percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med 2009; 360: 213–24. 2009/01/16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morris PD, Narracott A, von Tengg-Kobligk H, Silva Soto DA, Hsiao S, Lungu A, et al. Computational fluid dynamics modelling in cardiovascular medicine. Heart 2016; 102: 18–28. 2015/10/30. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taylor CA, Fonte TA, Min JK. Computational fluid dynamics applied to cardiac computed tomography for noninvasive quantification of fractional flow reserve. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 61: 2233–41. 2013/04/09. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koo BK, Erglis A, Doh JH, Daniels D V, Jegere S, Kim HS, et al. Diagnosis of ischemia-causing coronary stenoses by noninvasive fractional flow reserve computed from coronary computed tomographic angiograms. results from the prospective multicenter DISCOVER-FLOW (diagnosis of Ischemia-Causing stenoses obtained via noni. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58: 1989–97. 2011/10/29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Min JK, Leipsic J, Pencina MJ, Berman DS, Koo B-K, van Mieghem C, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of fractional flow reserve from anatomic CT angiography. JAMA 2012; 308: 1237–45. 2012/08/28. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Norgaard BL, Leipsic J, Gaur S, Seneviratne S, BS K, Ito H, et al. Diagnostic performance of noninvasive fractional flow reserve derived from coronary computed tomography angiography in suspected coronary artery disease: the NXT trial (analysis of coronary blood flow using CT angiography: next steps. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014; 63: 1145–55. 2014/02/04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leiner T, Takx RAP. Predicting the need for revascularization in stable coronary artery disease: protons or photons? JACC Cardiovasc Imaging - Artic Press. 2019;. 2019/10/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Coenen A, Lubbers MM, Kurata A, Kono A, Dedic A, Chelu RG, et al. Fractional flow reserve computed from noninvasive CT angiography data: diagnostic performance of an on-site clinician-operated computational fluid dynamics algorithm. Radiology 2015; 274: 674–83. 2014/10/17. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14140992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Renker M, Schoepf UJ, Wang R, Meinel FG, Rier JD, Bayer RR, et al. Comparison of diagnostic value of a novel noninvasive coronary computed tomography angiography method versus standard coronary angiography for assessing fractional flow reserve. Am J Cardiol 2014; 114: 1303–8. 2014/09/11. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.07.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kruk M, Wardziak Łukasz, Demkow M, Pleban W, Pręgowski J, Dzielińska Z, et al. Workstation-Based calculation of CTA-Based FFR for intermediate stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2016; 9: 690–9. 2016/02/22. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.De Geer J, Sandstedt M, Björkholm A, Alfredsson J, Janzon M, Engvall J, et al. Software-based on-site estimation of fractional flow reserve using standard coronary CT angiography data. Acta radiol 2016; 57: 1186–92. 2015/12/23. doi: 10.1177/0284185115622075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.BS K, Cameron JD, Munnur RK, Wong D, Fujisawa Y, Sakaguchi T, et al. Noninvasive CT-Derived FFR based on structural and fluid analysis: a comparison with invasive FFR for detection of functionally significant stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017; 10: 663–73. 2016/10/25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ihdayhid AR, Sakaguchi T, Linde JJ, Sørgaard MH, Kofoed KF, Fujisawa Y, et al. Performance of computed tomography-derived fractional flow reserve using reduced-order modelling and static computed tomography stress myocardial perfusion imaging for detection of haemodynamically significant coronary stenosis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2018; 19: 1234–43. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jey114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fujimoto S, Kawasaki T, Kumamaru KK, Kawaguchi Y, Dohi T, Okonogi T, et al. Diagnostic performance of on-site computed CT-fractional flow reserve based on fluid structure interactions: comparison with invasive fractional flow reserve and instantaneous wave-free ratio. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2019; 20: 343–52. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jey104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kato E, Fujimoto S, Kumamaru KK, Kawaguchi YO, Dohi T, Aoshima C, et al. Adjustment of CT-fractional flow reserve based on fluid–structure interaction underestimation to minimize 1-year cardiac events. Heart Vessels 2020; 35: 162–9. doi: 10.1007/s00380-019-01480-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Donnelly PM, Kolossváry M, Karády J, Ball PA, Kelly S, Fitzsimons D, et al. Experience with an on-site coronary computed Tomography-Derived fractional flow reserve algorithm for the assessment of intermediate coronary stenoses. Am J Cardiol 2018; 121: 9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van Hamersvelt RW, Voskuil M, de Jong PA, Willemink MJ, Išgum I, Leiner T. Diagnostic performance of on-site coronary CT angiography–derived fractional flow reserve based on patient-specific lumped parameter models. Radiology 2019; 1: e190036. doi: 10.1148/ryct.2019190036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Freiman M, Nickisch H, Schmitt H, Maurovich-Horvat P, Donnelly PM, Vembar M, et al. A functionally personalized boundary condition model to improve estimates of fractional flow reserve with CT (CT-FFR. Med Phys 2018; 45: 1170–7. doi: 10.1002/mp.12753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nickisch H, Lamash Y, Prevrhal S, Freiman M, Vembar M, Goshen L, et al. Learning patient-specific lumped models for interactive coronary blood flow simulations. Vol. 9350, Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention - MICCAI 2015. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer 2015;: 433–41. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chung J-H, Lee KE, Nam C-W, Doh J-H, Kim HI, Kwon S-S, et al. Diagnostic performance of a novel method for fractional flow reserve computed from noninvasive computed tomography angiography (NOVEL-FLOW study. Am J Cardiol 2017; 120: 362–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.04.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shi C, Zhang D, Cao K, Zhang T, Luo L, Liu X, et al. A study of noninvasive fractional flow reserve derived from a simplified method based on coronary computed tomography angiography in suspected coronary artery disease. Biomed Eng Online 2017; 16: 1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12938-017-0330-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang L, Xu L, He J, Wang Z, Sun Z, Fan Z, et al. Diagnostic performance of a fast non-invasive fractional flow reserve derived from coronary CT angiography: an initial validation study. Clin Radiol 2019; 74: 973.e1–973.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2019.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Giannopoulos AA, Tang A, Ge Y, Cheezum MK, Steigner ML, Fujimoto S, et al. Diagnostic performance of a lattice Boltzmann-based method for CT-based fractional flow reserve. EuroIntervention 2018; 13: 1696–704. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-17-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Han H, Bae YG, Hwang ST, Kim H-Y, Park I, Kim S-M, H-YY K, S-MM K, et al. Computationally simulated fractional flow reserve from coronary computed tomography angiography based on fractional myocardial mass. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2019; 35: 185–93. doi: 10.1007/s10554-018-1432-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Siogkas PK, Anagnostopoulos CD, Liga R, Exarchos TP, Sakellarios AI, Rigas G, et al. Noninvasive CT-based hemodynamic assessment of coronary lesions derived from fast computational analysis: a comparison against fractional flow reserve. Eur Radiol 2019; 29: 2117–26. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5781-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu X, Wang Y, Zhang H, Yin Y, Cao K, Gao Z, et al. Evaluation of fractional flow reserve in patients with stable angina: can CT compete with angiography? Eur Radiol 2019; 29: 3669–77. doi: 10.1007/s00330-019-06023-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang Z-Q, Zhou Y-J, Zhao Y-X, Shi D-M, Liu Y-Y, Liu W, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of a deep learning approach to calculate FFR from coronary CT angiography. J Geriatr Cardiol 2019; 16: 42–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tang CX, Wang YN, Zhou F, Schoepf UJ, Assen Mvan, Stroud RE, et al. Diagnostic performance of fractional flow reserve derived from coronary CT angiography for detection of lesion-specific ischemia: a multi-center study and meta-analysis. Eur J Radiol 2019; 116: 90–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2019.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kumamaru KK, Fujimoto S, Otsuka Y, Kawasaki T, Kawaguchi Y, Kato E, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of 3D deep-learning-based fully automated estimation of patient-level minimum fractional flow reserve from coronary computed tomography angiography. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2019; 0: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yoshikawa Y, Nakamoto M, Nakamura M, Hoshi T, Yamamoto E, Imai S, et al. On-Site evaluation of CT-based fractional flow reserve using simple boundary conditions for computational fluid dynamics. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2020; 36: 337–46. doi: 10.1007/s10554-019-01709-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhuang B, Wang S, Zhao S, Lu M. Computed tomography angiography-derived fractional flow reserve (CT-FFR) for the detection of myocardial ischemia with invasive fractional flow reserve as reference: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radiol 2020; 30: 712–25. 2019/11/07. doi: 10.1007/s00330-019-06470-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Collet C, Miyazaki Y, Ryan N, Asano T, Tenekecioglu E, Sonck J, et al. Fractional flow reserve derived from computed tomographic angiography in patients with multivessel CAD. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 71: 2756–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tesche C, Otani K, De Cecco CN, Coenen A, De Geer J, Kruk M, et al. Influence of coronary calcium on diagnostic performance of machine learning CT-FFR: results from machine registry. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2019;Aug. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cook CM, Petraco R, Shun-Shin MJ, Ahmad Y, Nijjer S, Al-Lamee R, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of computed Tomography–Derived fractional flow reserve. JAMA Cardiol 2017; 2: 803–10. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.1314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Douglas PS, Pontone G, Hlatky MA, Patel MR, Norgaard BL, Byrne RA, et al. Clinical outcomes of fractional flow reserve by computed tomographic angiography-guided diagnostic strategies vs. usual care in patients with suspected coronary artery disease: the prospective longitudinal trial of FFR CT : outcome and resource impacts study. Eur Heart J 2015; 36: 3359–67. 2015/09/04. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Douglas PS, De Bruyne B, Pontone G, Patel MR, Norgaard BL, Byrne RA, et al. 1-Year outcomes of FFR CT -guided care in patients with suspected coronary disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016; 68: 435–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.05.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jensen JM, Bøtker HE, Mathiassen ON, Grove EL, Øvrehus KA, Pedersen KB, Møller Jensen J, Erik Bøtker H, Norling Mathiassen O, Lerkevang Grove E, Altern Øvrehus K, Bech Pedersen K, et al. Computed tomography derived fractional flow reserve testing in stable patients with typical angina pectoris: influence on downstream rate of invasive coronary angiography. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2018; 19: 405–14. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jex068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fairbairn TA, Nieman K, Akasaka T, Nørgaard BL, Berman DS, Raff G, et al. Real-World clinical utility and impact on clinical decision-making of coronary computed tomography angiography-derived fractional flow reserve: lessons from the advance registry. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 3701–11. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Modi BN, Sankaran S, Kim HJ, Ellis H, Rogers C, Taylor CA, et al. Predicting the physiological effect of revascularization in serially diseased coronary arteries. Circulation 2019; 12: e007577. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.118.007577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, Capodanno D, Barbato E, Funck-Brentano C, et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J 2020;. ; 41: 407–77. 2019/09/112020. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Conte E, Sonck J, Mushtaq S, Collet C, Mizukami T, Barbato E, et al. FFRCT and CT perfusion: a review on the evaluation of functional impact of coronary artery stenosis by cardiac CT. Int J Cardiol 2020; 300: 289–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Delgado Sánchez-Gracián C, Oca Pernas R, Trinidad López C, Santos Armentia E, Vaamonde Liste A, Vázquez Caamaño M, et al. Quantitative myocardial perfusion with stress dual-energy CT: iodine concentration differences between normal and ischemic or necrotic myocardium. initial experience. Eur Radiol 2016; 26: 3199–207. 2015/12/25. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-4128-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ruzsics B, Schwarz F, Schoepf UJ, Lee YS, Bastarrika G, Chiaramida SA, et al. Comparison of dual-energy computed tomography of the heart with single photon emission computed tomography for assessment of coronary artery stenosis and of the myocardial blood supply. Am J Cardiol 2009; 104: 318–26. 2009/07/21. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.03.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Patel AR, Bamberg F, Branch K, Carrascosa P, Chen M, Cury RC, et al. Society of cardiovascular computed tomography expert consensus document on myocardial computed tomography perfusion imaging. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2020; 14: 87–100. 2020/03/04. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2019.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Liu A, Wijesurendra RS, Liu JM, Forfar JC, Channon KM, Jerosch-Herold M, et al. Diagnosis of microvascular angina using cardiac magnetic resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 71: 969–79. 2018/03/03. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.12.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 86.Taqueti VR, Hachamovitch R, Murthy VL, Naya M, Foster CR, Hainer J, et al. Global coronary flow reserve is associated with adverse cardiovascular events independently of luminal angiographic severity and modifies the effect of early revascularization. Circulation 2015; 131: 19–27. 2014/11/18. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Danad I, Szymonifka J, Schulman-Marcus J, Min JK. Static and dynamic assessment of myocardial perfusion by computed tomography. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2016; 17: 836–44. 2016/03/26. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jew044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rief M, Zimmermann E, Stenzel F, Martus P, Stangl K, Greupner J, et al. Computed tomography angiography and myocardial computed tomography perfusion in patients with coronary stents: prospective Intraindividual comparison with conventional coronary angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 62: 1476–85. 2013/06/25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sørgaard MH, Linde JJ, Kühl JT, Kelbæk H, Hove JD, Fornitz GG, et al. Value of Myocardial Perfusion Assessment With Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography in Patients With Recent Acute-Onset Chest Pain. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 2018; 11: 1611–21. 2017/12/19. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Litt HI, Gatsonis C, Snyder B, Singh H, Miller CD, Entrikin DW, et al. Ct angiography for safe discharge of patients with possible acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 1393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1201163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rossi A, Papadopoulou SL, Pugliese F, Russo B, Dharampal AS, Dedic A, et al. Quantitative computed tomographic coronary angiography: does it predict functionally significant coronary stenoses? Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2014; 7: 43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fihn SD, Blankenship JC, Alexander KP, Bittl JA, Byrne JG, Fletcher BJ, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS focused update of the Guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease. Circulation 2014; 130: 1749–67. 2014 Jul 29. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rochitte CE, George RT, Chen MY, Arbab-Zadeh A, Dewey M, Miller JM, et al. Computed tomography angiography and perfusion to assess coronary artery stenosis causing perfusion defects by single photon emission computed tomography: the CORE320 study. Eur Heart J 2014; 35: 1120–30. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.SM K, Choi JW, Hwang HK, Song MG, Shin JK, Chee HK. Diagnostic performance of combined noninvasive anatomic and functional assessment with dual-source CT and adenosine- induced stress dual-energy CT for detection of significant coronary stenosis. Am J Roentgenol 2012; 198: 512–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.De Cecco CN, Harris BS, Schoepf UJ, Silverman JR, McWhite CB, Krazinski AW, et al. Incremental value of pharmacological stress cardiac dual-energy CT over coronary CT angiography alone for the assessment of coronary artery disease in a high-risk population. American Journal of Roentgenology 2014; 203: W70–7. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pontone G, Andreini D, Guaricci AI, Baggiano A, Fazzari F, Guglielmo M, et al. Incremental Diagnostic Value of Stress Computed Tomography Myocardial Perfusion With Whole-Heart Coverage CT Scanner in Intermediate- to High-Risk Symptomatic Patients Suspected of Coronary Artery Disease. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 2019; 12: 338–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nakamura S, Kitagawa K, Goto Y, Omori T, Kurita T, Yamada A, et al. Incremental Prognostic Value of Myocardial Blood Flow Quantified With Stress Dynamic Computed Tomography Perfusion Imaging. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging 2019; 12: 1379–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2018.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Moss AJ, Williams MC, Newby DE, Nicol ED. The updated NICE guidelines: cardiac CT as the first-line test for coronary artery disease. Curr Cardiovasc Imaging Rep 2017; 10: 15. doi: 10.1007/s12410-017-9412-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mannil M, von Spiczak J, Manka R, Alkadhi H. Texture analysis and machine learning for detecting myocardial infarction in noncontrast low-dose computed tomography. Invest Radiol 2018; 53: 338–43. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Itu L, Sharma P, Mihalef V, Kamen A, Suciu C, Comaniciu D. A patient-specific reduced-order model for coronary circulation. In: 2012 9th IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI. Barcelona; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Coenen A, Kim Y-H, Kruk M, Tesche C, De Geer J, Kurata A, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of a Machine-Learning approach to coronary computed tomographic Angiography–Based fractional flow reserve. Circulation 2018; 11: e007217. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.117.007217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Li Y, Yu M, Dai X, Lu Z, Shen C, Wang Y, et al. Detection of hemodynamically significant coronary stenosis: CT myocardial perfusion versus machine learning CT fractional flow reserve. Radiology 2019; 293: 305–14. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019190098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zreik M, Lessmann N, van Hamersvelt RW, Wolterink JM, Voskuil M, Viergever MA, et al. Deep learning analysis of the myocardium in coronary CT angiography for identification of patients with functionally significant coronary artery stenosis. Med Image Anal 2018; 44: 72–85. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2017.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.van Hamersvelt RW, Zreik M, Voskuil M, Viergever MA, Išgum I, Leiner T, et al. Deep learning analysis of left ventricular myocardium in CT angiographic intermediate-degree coronary stenosis improves the diagnostic accuracy for identification of functionally significant stenosis. Eur Radiol 2019; 29: 2350–9. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5822-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.van Hamersvelt RW, Išgum I, de Jong PA, Cramer MJM, Leenders GEH, Willemink MJ, et al. Application of spectral compuTed tomographY to impRove specIficity of cardiac compuTed tomographY (clarity study): rationale and design. BMJ Open 2019; 9: e025793. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pontone G, De Cecco C, Baggiano A, Guaricci AI, Guglielmo M, Leiner T, et al. Design of CTP-PRO study (impact of stress cardiac computed tomography myocardial perfusion on downstream resources and prognosis in patients with suspected or known coronary artery disease: a multicenter international study. Int J Cardiol 2019; 292: 253–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Patel MR, Nørgaard BL, Fairbairn TA, Nieman K, Akasaka T, Berman DS, et al. 1-Year Impact on Medical Practice and Clinical Outcomes of FFRCT: The ADVANCE Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2020; 13: 97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2019.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Driessen RS, Danad I, Stuijfzand WJ, Raijmakers PG, Schumacher SP, van Diemen PA, et al. Comparison of Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography, Fractional Flow Reserve, and Perfusion Imaging for Ischemia Diagnosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019; 73: 161–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.10.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Nagel E, Greenwood JP, McCann GP, Bettencourt N, Shah AM, Hussain ST, et al. Magnetic resonance perfusion or fractional flow reserve in coronary disease. N Engl J Med 2019; 380: 2418–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.