Abstract

Chagas disease is caused by the flagellate protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi. Cardiomyopathy and damage to gastrointestinal tissue are the main disease manifestations. There are data suggesting that the immune response to T. cruzi depends on the intestinal microbiota. We hypothesized that Chagas disease is associated with an altered gut microbiome and that these changes are related to the disease phenotype. The stool microbiome from 104 individuals, 73 with Chagas disease (30 with the cardiac, 11 with the digestive, and 32 with the indeterminate form), and 31 healthy controls was characterized using 16S rRNA amplification and sequencing. The QIIME (Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology) platform was used to analyze the data. Alpha and beta diversity indexes did not indicate differences between the groups. However, the relative abundance of Verrucomicrobia, represented primarily by the genus Akkermansia, was significantly lower in the Chagas disease groups, especially the cardiac group, compared to the controls. Furthermore, differences in the relative abundances of Alistipes, Bilophila, and Dialister were observed between the groups. We conclude that T. cruzi infection results in changes in the gut microbiome that may play a role in the myocardial and intestinal inflammation seen in Chagas disease.

Keywords: Chagas disease, microbiome, 16S rRNA sequencing, gut, dysbiosis

Introduction

Chagas disease is an anthropozoonosis found primarily in Central and South America. Six to eight million people are infected, and 65–100 million live in areas at risk of infection (Engels and Savioli, 2006; Schofield et al., 2006; WHO, 2015; PAHO, 2016). The causative agent is the flagellate protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi, which in recent decades has been a major public health concern, not only in Latin America but also in non-endemic areas due to migration. A period of 2–4 months following initial infection is referred to as the acute phase and is characterized by high parasite levels in the peripheral blood. This gives way to chronic asymptomatic infection, termed the indeterminate phase. Approximately 30–40% of patients will present with a determinate form (cardiac or digestive) over a period of 20–30 years after the initial infection, while the remaining group does not develop the clinically apparent disease (Rassi et al., 2010).

The pathophysiology of Chagas disease is complex and probably represents an imbalanced immunological response to the parasite, leading to inflammation, oxidative stress, microvascular damage, and fibrosis (Rassi et al., 2010). The severity of myocardial inflammation does not correlate with the number of parasites present in the heart (Teixeira et al., 2006; Girones et al., 2007). This suggests that the immunological response together with the genetic background is key in the development of cardiac disease (Cunha-Neto and Chevillard, 2014).

Previous data suggest that the gut may play a role, not only in the digestive form (megacolon) of Chagas disease but also in the development of cardiomyopathy. Experiments using bioluminescent T. cruzi have shown it to circulate from the gut to cardiac tissue (Lewis et al., 2014, 2016). Furthermore, the gut may act as a reservoir of T. cruzi in recrudescent infections (Francisco et al., 2015).

The gut microbiome appears to be involved in the host response to parasites. A high abundance of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium in the gut microbiota has been associated with resistance to malaria in animal models. This resistance was transmissible through fecal transplants from malaria-resistant to germ-free mice (Villarino et al., 2016). Moreover, in a murine model of Chagas disease, the gut microbial composition was affected by parasite burden. The concentration of fecal linoleic acid and its derivatives, which can alter the gut immune response, was associated with T. cruzi infection, as was the abundance of Ruminococcaceae and Lachnospiraceae (McCall et al., 2018).

The purpose of this study was to further understand the role of the gut microbiome in the different Chagas disease phenotypes. We evaluated the fecal microbiome in patients with different forms of the disease cardiac, gastrointestinal, and indeterminate and compared the results to healthy controls.

Materials and Methods

Study Population and Sample Collection

Patients with Chagas disease and diagnosed with the cardiac (n = 30) or indeterminate (n = 32) forms were selected from a group of 93 patients previously enrolled in a Brazilian cohort (REDS II—Natural History of Chagas' disease) held between 2008 and 2010 in São Paulo, Brazil (Sabino et al., 2013). Eleven patients with the digestive form (megacolon) under follow-up at the Hospital das Clínicas, University of São Paulo and the Institute of Infectology Emílio Ribas both in São Paulo, Brazil, were also enrolled. Thirty-one T. cruzi-seronegative blood donors from the Fundação Pró-Sangue were enrolled as controls. Stool samples were obtained between October 2014 and December 2015. Samples were collected in sterile tubes containing 12 mL of 6 M guanidine HCL/0.2 M EDTA solution. We used a questionnaire to collect demographic variables and information on bowel habits. The exclusion criteria were previous treatment with benznidazole, antibiotic use in the 3 months prior to sample collection, or a body mass index of 40 or over.

DNA Extraction

Genomic DNA was extracted from 20 g of feces using the Power Soil DNA Isolation Kit® (MoBio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA) with modifications as described by the Human Microbiome Project (McInnes and Cutting, 2010). The amount and purity of the extracted DNA were determined fluorometrically using the Qubit® BR dsDNA Assay Kit with the aid of a Qubit® Fluorometer 2.0 (Invitrogen Co., Carlsbad, CA).

Library Preparation and 16S Sequencing

The 16S rRNA V4 variable region was amplified using the 515/806 primer set (Caporaso et al., 2011) with a barcode on the forward primer and sequenced using an Ion Torrent™ Personal Genome Machine (Life Technologies, Waltham, MA) with an Ion 318TM chip kit v2 using 400-base chemistry.

Data Analysis

Sequences were filtered by length (>280 pb), quality score (Q = 30), and minimum expected error (0.1) using the USEARCH tool (Edgar, 2010). Single-end reads were assembled using PEAR software (Zhang et al., 2014). Sequences were clustered at 97% similarity using USEARCH (Edgar, 2010) against the Greengenes 16S reference database (13_8 version) (DeSantis et al., 2006). Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) with singletons (n = 1) were removed. Taxonomy was assigned to each OTU by performing BLAST searches against the Greengenes database (13_8 version). Sequences were filtered for bacterial phylotypes for further analyses using the Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology (QIIME2) plugin (Bolyen et al., 2019). Alpha-diversity measurements, including species richness, evenness, and Simpson and Shannon's diversity index, were calculated based on the rarefied OTU tables using 37,868 sequences per sample. Differences between taxonomic profiles were identified using the ANCOM test (Mandal et al., 2015) with biom tables collapsed to the genus level as the input file.

Phylogenetic beta-diversity (weighted and unweighted UniFrac) (Lozupone et al., 2011) and non-phylogenetic (Bray–Curtis and Jaccard) methods were calculated using cumulative-sum-scaled (CSS) normalized distance matrices. These matrices were employed to generate ordination plots using principal coordinate analysis (PCoA). All sequencing raw reads have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under the project accession number PRJNA471615.

Statistical Analysis

Variable distributions were assessed graphically and with the Shapiro–Wilk test. Continuous variables were not normally distributed and consequently, and we used non-parametric hypothesis tests such as the Kruskal–Wallis test.

Differences between groups in demographic characteristics and bowel habits were assessed with Kruskal–Wallis and chi-square test, respectively, using the statistical software package GraphPad Prism 6. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical significance of differences in relative abundance between the groups (control, cardiac, indeterminate, and megacolon) at different taxonomic levels was determined using the Kruskal–Wallis and Mann–Whitney U tests in the QIIME v1.8 software package. A p < 0.05 after Bonferroni correction was considered statistically significant. The Kruskal–Wallis H test was applied to compare all alpha diversity parameters between groups. PERMANOVA (vegan::adonis) was performed to determine if the separation of sample groups in beta diversity was significant.

Results

Participants' Demographics

Participant's demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. There was no difference between groups in age, weight, or height. However, the megacolon group was composed only of women, whereas the patients with cardiac and indeterminate forms were primarily men (p = 0.0005). The reported bowel habits in the control group differed slightly from the Chagas disease patients, independent of disease phenotype (p < 0.0001; Table 1).

Table 1.

Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 73 participants with three different Chagas disease phenotypes, cardiac, indeterminate, and megacolon, and 31 controls.

| Characteristics | Cardiac (n = 30) | Indeterminate (n = 32) | Megacolon (n = 11) | Control (n = 31) | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 59 ± 7 | 58 ± 9 | 55 ± 11 | 62 ± 9 | 0.099 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 20 (66%) | 22 (73%) | 0% | 17 (57%) | 0.0005 |

| Height (m), mean ± SD | 1.64 ± 0.31 | 1.64 ± 0.08 | 1.60 ± 0.07 | 1.66 ± 0.08 | 0.168 |

| Weight (kg), mean ± SD | 71.1± 19.07 | 72.7 ± 10 | 66.5 ± 11.5 | 79.2 ± 22.5 | 0.321 |

| Body mass index, mean ± SD | 27 ± 4 | 27 ± 3 | 26 ± 4 | 29 ± 8 | 0.549 |

| Bowel habit, n (%) | |||||

| Once or more times/day | 24 (80%) | 29 (91%) | 4 (36%) | 31 (100%) | |

| Once every 2 to 3 days | 5 (17%) | 2 (6%) | 4 (36%) | 0 | <0.0001** |

| Once a week or less | 1 (3%)0 | 1 (3%) | 3 (27%) | 0 |

Kruskal–Wallis -test, p < 0.05 as the threshold for significance.

Chi-square test, p < 0.05 as the threshold for significance.

Sequencing Metrics

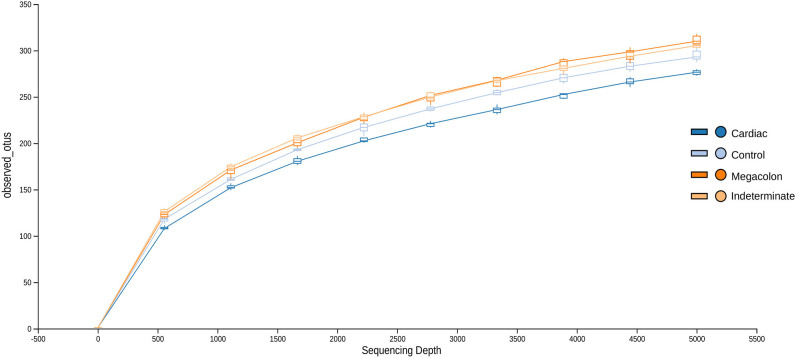

After applying the Torrent Browser software filters, 28,418,519 classifiable sequences, representing 1866 species-level OTUs (median: 1566–1866 OTUs/sample; range: 90–498), were obtained from 104 stool samples. Rarefaction curves showed that the number of observed OTUs plateaued after 37,868 reads (Figure 1). No significant differences were observed in the evaluated alpha diversity indexes (Shannon, Simpson, Chao1, and number of observed species between the groups (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Rarefaction curves demonstrating the estimated number of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) in the microbiome of stool samples of the control group and Chagas disease groups (indeterminate, cardiac, and megacolon phenotypes) as a function of the sequencing effort generated through the QIIME (Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology) platform.

Table 2.

Alpha diversity analyses of the fecal microbiome in Chagas disease phenotypes (indeterminate, cardiac, and megacolon) and controls.

| Control | Indeterminate | Cardiac | Megacolon | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chao1 richness estimate | 1881.4 | 1880.0 | 1809.9 | 1617.3 | 0.577 |

| Shannon index | 7.1 | 7.5 | 7.1 | 7.2 | 0.301 |

| Simpson's diversity index | 0.973 | 0.983 | 0.974 | 0.980 | 0.333 |

| Number of observed species | 1866 | 1848 | 1741 | 1566 | 0.751 |

Kruskal–Wallis H-test, p < 0.05 as the threshold for significance.

Furthermore, the beta diversity index visualized by PCoA of weighted and unweighted UniFrac distance matrices revealed that the microbial composition of stool samples from the controls and Chagas disease patients were not clustered according to their bacterial composition, with p-values of 0.110 and 0.103, respectively, according to the Permanova test (Supplementary Figure 1).

Characterization of the Microbiota of Clinical Forms

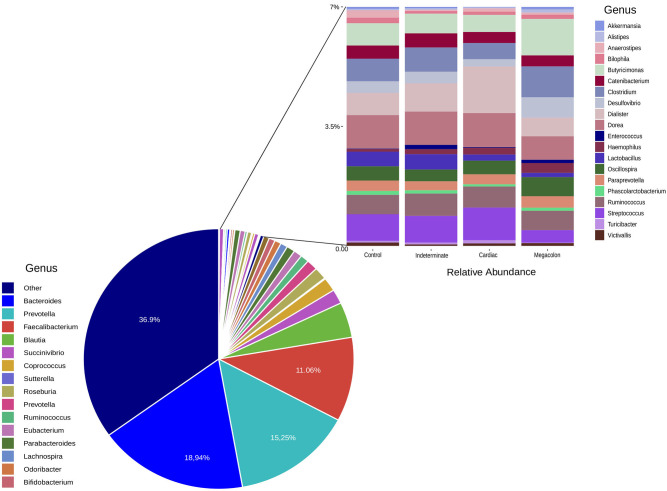

Comparing the sequencing results of patients with clinical forms of Chagas disease (cardiac, indeterminate, and megacolon) with the control group, was possible to observe the characterization of important microbiota present in this study population.

The microbiota composition included three predominant genus: Bacteroides, Prevotella, and Faecalibacterium. The most abundant taxa was Bacteroides in control (25.96%), indeterminate (14.30%), and megacolon (19.04%), respectively. The cardiac group was dominated by Prevotella (20.15%) (Supplementary Table 2).

At the phylum level, the only difference between the groups was in the abundance of Verrucomicrobia, although it was only present at a low proportion (<0.1%). This phylum was more abundant in the healthy controls than in patients with the cardiac form (p = 0.045) (Table 3). The ANCOM test confirmed these results, demonstrating significant differences between groups at every taxonomic level. This was particularly marked for the Akkermansia genus, which was less abundant in the fecal microbiomes of the cardiac phenotype group than in the healthy controls. Figure 2 shows the fecal bacterial abundances at the genus level for the three Chagas disease groups and control subjects (also see Table 4).

Table 3.

Abundance of organisms in the fecal microbiome of the cardiac phenotype of Chagas disease and control group.

| Control * (%) | Cardiac * (%) | FDR_P | p-value¬ | p-value Bonferroni correction ¬ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phylum | Verrucomicrobia | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.045 | 0.003 | 0.045 |

| Class | Verrucomicrobia | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.062 | 0.002 | 0.062 |

| Family | Verrucomicrobiaceae | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.188 | 0.002 | 0.188 |

| Genus | Akkermansia | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.477 | 0.003 | 0.572 |

Data are expressed as means.

Mann–Whitney U-test, p < 0.05 were considered significant. FDR_P—false discovery rate.

Figure 2.

Genera relative abundance (%) based plots. The left plot represents the average relative abundance detected in the stool samples of all the groups (control, indeterminate, cardiac, and megacolon) and the right least abundant genus (<7%).

Table 4.

Differences in the fecal microbiome taxonomic profiles in the Chagas disease phenotypes (indeterminate, cardiac, and megacolon) vs. controls.

| Phylum | Class | Family | Genus | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control × cardiac* | Verrucomicrobia (W 3) | Verrucomicrobia (W 11) | Verrucomicrobiaceae (W 31) | Akkermansia (W 23) |

| Control × megacolon** | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Control × indeterminate** | NS | NS | NS | NS |

Data are expressed as W values using ANCOM test.

NS—no significant differences were observed.

After Bonferroni correction, the comparisons of relative abundances at the other taxonomic levels did not reach statistical significance. However, some differences, albeit not statistically significant, are important to note. At the class level, Alphaproteobacteria and Betaproteobacteria were less abundant in the cardiac and megacolon groups (Alphaproteobacteria: 0.02, 0.13, and 0.53%; Betaproteobacteria: 1.53, 1.21, and 2.27%, in the cardiac, megacolon, and control groups, respectively). The relative abundances of the bacteria that differed between groups at the family and genus levels are shown in Supplementary Tables 1, 2, respectively.

Patients with Chagas megacolon had higher relative abundances of Rikenellaceae and Odoribacteraceae than the other groups. The abundance of Rikenellaceae was 0.39, 0.87, 0.82, and 0.31% in the cardiac, megacolon, indeterminate, and control samples, respectively, while the abundance of Odoribacteraceae was 0.99, 1.65, 1.18, and 1.48%. There were significant differences in the relative abundances of members of Rikenellaceae (genus Alistipes: 0.07, 0.02, 0.04, and 0.02%), Desulfovibrionaceae (genus Bilophila: 0.11, 0.07, 0.07, and 0.11%), and Veillonellaceae (genus Dialister: 0.32, 1.02, 0.53, and 0.50%) among the megacolon, cardiac, indeterminate, and control groups (Kruskal–Wallis, p < 0.05).

Discussion

Chagas disease has heterogeneous clinical manifestations, including gastrointestinal disease. The relationship between the resident microbiota and Chagas disease phenotypes is still poorly understood. This is the first study that has sought to describe the fecal microbiome of adult patients with the various Chagas disease phenotypes using next-generation sequencing technology.

Robello et al. (2019) observed a difference in the microbiota between children infected with T. cruzi and controls. In the study, children aged 5–15 years with Chagas disease had higher fecal Firmicutes (Streptococcus, Roseburia, Butyrivibrio, and Blautia), and lower Bacteroides. After being treated with benznidazole, the fecal microbiota was normalized in comparison with control children (Robello et al., 2019).

We have shown that the diversity of the gut microbiome in patients with the cardiac form of Chagas disease differed from the other Chagas phenotypes and the control group. These differences were mostly due to a lower abundance of the phylum Verrucomicrobia in the Chagas disease groups. In particular, there was a lower abundance of the genus Akkermansia, especially among cardiac patients.

The abundance of Akkermansia, a butyrate-producing bacteria, has been associated with a healthy gut and decreased inflammation in several animals (Everard et al., 2013; Li et al., 2019) and clinical (Collaboration, 2016) studies. Interestingly, the use of prebiotics that increases the abundance of Akkermansia in the gut has been associated with reduced endotoxemia and insulin resistance (Everard et al., 2013). Increased abundance of Akkermansia has been linked with the beneficial effects of a low-protein/high-carbohydrate diet for maintaining gut health (Li et al., 2019). This microorganism has also been associated with a positive clinical response to therapy in patients with cancer. In addition, as a probiotic in mice with unfavorable microbiota, it induces the production of interleukin (IL)-12, favoring an antitumor response (Routy et al., 2018). Interestingly, IL-12 is also involved in the immune response to T. cruzi (Marin-Neto et al., 2007), and our data support a role for Akkermansia in maintaining a healthy gut.

We have also demonstrated differences in the proportion of a number of bacterial groups when comparing T. cruzi-infected subjects to non-infected individuals. However, these findings were not significant after Bonferroni correction. Notably, the cardiac phenotype of Chagas disease was associated with fecal enrichment of Alistipes and Bilophila, when compared to the other Chagas disease groups. Both Alistipes and Bilophila are bile-tolerant microorganisms associated with an animal-based diet in humans (David et al., 2014; Wan et al., 2019). Alistipes has previously been associated with other diseases, such as diabetes (Qin et al., 2012), colon cancer (Fenner et al., 2007), and gut inflammation (Saulnier et al., 2011). Therefore, future studies should address the role of diet and these genera in gut dysbiosis in the different phenotypes of Chagas disease.

The abundance of Dialister, a genus of the Veillonellaceae family, was increased in the cardiac patients compared to controls and the other Chagas disease groups. Increased Dialister abundance in the gut microbiome has been previously associated with diabetes (Ciubotaru et al., 2015) and its complications (Sanchez-Alcoholado et al., 2017) as well as with inflammatory bowel syndromes (Lopetuso et al., 2018), suggesting its pathogenic potential.

Our findings suggest that infection with T. cruzi results in a shift in the gut microbiome toward a dysbiotic community, with lower levels of health-associated microorganisms such as Akkermansia, especially in the cardiac form of the disease. These data should be interpreted considering the limitations of this cross-sectional study. Comparisons with other work are limited due to a lack of standardized protocols among different studies of the gut microbiome (Costea et al., 2017; Panek et al., 2018). Furthermore, the progression of Chagas disease from the indeterminate form to the life-threatening cardiac form has previously been associated with a multitude of factors. Future studies to identify biomarkers of Chagas disease progression should be longitudinal in nature. The relationship between microbial composition and other variables involved with the microbiome and disease evolution should be investigated, including serum inflammatory mediators (Keating et al., 2015; Gomez-Olarte et al., 2019; Medeiros et al., 2019), diet (Nagajyothi et al., 2014), serum vitamin D levels (Oliveira Junior et al., 2019), gene polymorphisms (Reis et al., 2017; Carvalho et al., 2019), and habits such as exercise (Geraix et al., 2007; Alves et al., 2019). Other studies relating the gut parasite Blastocystis and microbiome also show that the genus Akkermansia plays a role in human gastrointestinal health. In this study, they observed an inverse correlation of the Blastocystis subtypes 3 and 4, suggesting differential associations of subtypes with host health (Tito et al., 2019).

The association between altered gut microbiome and the different phenotypes of Chagas disease suggests that it may play a role in the pathogenesis. This would be in addition to other possible multifactorial mechanisms, such as tissue parasite-driven damage, immune response, and microvascular and neuronal disturbances. However, it is unknown whether an already altered gut microbiome predisposes a T. cruzi-infected subject to disease progression, or if the established disease alters the gut microbiome. Further studies are needed to determine the mechanisms underlying the association between T. cruzi infection and the gut microbiome in Chagas disease. However, our results do suggest that manipulation of the gut microbiome could be an additional strategy for controlling the pathogenic potential of T. cruzi in infected subjects.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study can be found in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), PRJNA471615.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by The Internal Review Board of the University of São Paulo (CAPPesq number 1.174.958). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: MS-B, MM, and ES. Formal analysis: RR, MS-B, CM, RM, DF, and PA. Funding acquisition: ES. Investigation: MS-B and LO. Methodology: MS-B, RR, LO, CM, and RM. Supervision: MM and ES. Visualization: MS-B, LO, CM, RM, MM, and ES. Writing—original draft: MS-B. Writing—review and editing: All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. Foundation of Medicine Faculty, National Council supported this work for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), through the Cooperation Research Grant 467043/2014-0, and National Institutes of Health, through the Cooperation Research Grant 5U19AI098461. MS-B has received a Ph.D. scholarship from Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES), Brazil and PA has received a Ph.D. scholarship from São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2020.00402/full#supplementary-material

Beta diversity plots for non-phylogenetic (Bray-Curtis and Jaccard) and phylogenetic (weighted and unweighted UniFrac) methods in control and the Chagas disease phenotypes (indeterminate, cardiac and megacolon).

References

- Alves R. L., Cardoso B. R. L., Ramos I. P. R., Oliveira B. D. S., Dos Santos M. L., de Miranda A. S., et al. (2019). Physical training improves exercise tolerance, cardiac function and promotes changes in neurotrophins levels in chagasic mice. Life Sci. 232, 116629. 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.116629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolyen E., Rideout J. R., Dillon M. R., Bokulich N. A., Abnet C. C., Al-Ghalith G. A., et al. (2019). Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 852–857. 10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso J. G., Lauber C. L., Walters W. A., Berg-Lyons D., Lozupone C. A., Turnbaugh P. J., et al. (2011). Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 4516–4522. 10.1073/pnas.1000080107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho T. B., Padovani C. R., de Oliveira Junior L. R., Latini A. C. P., Kurokawa C. S., Pereira P. C. M., et al. (2019). ACAT-1 gene rs1044925 SNP and its relation with different clinical forms of chronic Chagas disease. Parasitol. Res. 118, 2343–2351. 10.1007/s00436-019-06377-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciubotaru I., Green S. J., Kukreja S., Barengolts E. (2015). Significant differences in fecal microbiota are associated with various tages of glucose tolerance in African American male veterans. Transl. Res. 166, 401–411. 10.1016/j.trsl.2015.06.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaboration NCDRF. (2016). Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19.2 million participants. Lancet 387, 1377–1396. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30054-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costea P. I., Zeller G., Sunagawa S., Pelletier E., Alberti A., Levenez F., et al. (2017). Towards standards for human fecal sample processing in metagenomic studies. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 1069–1076. 10.1038/nbt.3960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha-Neto E., Chevillard C. (2014). Chagas disease cardiomyopathy: immunopathology and genetics. Mediators Inflamm. 2014:683230. 10.1155/2014/683230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David L. A., Maurice C. F., Carmody R. N., Gootenberg D. B., Button J. E., Wolfe B. E., et al. (2014). Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 505, 559–563. 10.1038/nature12820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSantis T. Z., Hugenholtz P., Larsen N., Rojas M., Brodie E. L., Keller K., et al. (2006). Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 5069–5072. 10.1128/AEM.03006-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. (2010). Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26, 2460–2461. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels D., Savioli L. (2006). Reconsidering the underestimated burden caused by neglected tropical diseases. Trends Parasitol. 22, 363–366. 10.1016/j.pt.2006.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everard A., Belzer C., Geurts L., Ouwerkerk J. P., Druart C., Bindels L. B., et al. (2013). Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 9066–9071. 10.1073/pnas.1219451110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenner L., Roux V., Ananian P., Raoult D. (2007). Alistipes finegoldii in blood cultures from colon cancer patients. Emerging Infect. Dis. 13, 1260–1262. 10.3201/eid1308.060662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francisco A. F., Lewis M. D., Jayawardhana S., Taylor M. C., Chatelain E., Kelly J. M. (2015). Limited ability of posaconazole to cure both acute and chronic trypanosoma cruzi infections revealed by highly sensitive in vivo imaging. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59, 4653–4661. 10.1128/AAC.00520-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraix J., Ardisson L. P., Marcondes-Machado J., Pereira P. C. (2007). Clinical and nutritional profile of individuals with Chagas disease. Braz. J. Infect. Dis 11, 411–414. 10.1590/s1413-86702007000400008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girones N., Carrasco-Marin E., Cuervo H., Guerrero N. A., Sanoja C., John S., et al. (2007). Role of Trypanosoma cruzi autoreactive T cells in the generation of cardiac pathology. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1107, 434–444. 10.1196/annals.1381.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Olarte S., Bolanos N. I., Echeverry M., Rodriguez A. N., Cuellar A., Puerta C. J., et al. (2019). Intermediate monocytes and cytokine production associated with severe forms of chagas disease. Front. Immunol. 10:1671. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating S. M., Deng X., Fernandes F., Cunha-Neto E., Ribeiro A. L., Adesina B., et al. (2015). Inflammatory and cardiac biomarkers are differentially expressed in clinical stages of Chagas disease. Int. J. Cardiol. 199, 451–459. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.07.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M. D., Fortes Francisco A., Taylor M. C., Burrell-Saward H., McLatchie A. P., Miles M. A., et al. (2014). Bioluminescence imaging of chronic Trypanosoma cruzi infections reveals tissue-specific parasite dynamics and heart disease in the absence of locally persistent infection. Cell. Microbiol. 16, 1285–1300. 10.1111/cmi.12297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M. D., Francisco A. F., Taylor M. C., Jayawardhana S., Kelly J. M. (2016). Host and parasite genetics shape a link between Trypanosoma cruzi infection dynamics and chronic cardiomyopathy. Cell. Microbiol. 18, 1429–1443. 10.1111/cmi.12584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Rasmussen T. S., Rasmussen M. L., Li J., Henriquez Olguin C., Kot W., et al. (2019). The gut microbiome on a periodized low-protein diet is associated with improved metabolic health. Front. Microbiol. 10:709. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopetuso L. R., Petito V., Graziani C., Schiavoni E., Paroni Sterbini F., Poscia A., et al. (2018). Gut microbiota in health, diverticular disease, irritable bowel syndrome, and inflammatory bowel diseases: time for microbial marker of gastrointestinal disorders. Dig. Dis. 36, 56–65. 10.1159/000477205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozupone C., Lladser M. E., Knights D., Stombaugh J., Knight R. (2011). UniFrac: an effective distance metric for microbial community comparison. ISME J. 5, 169–172. 10.1038/ismej.2010.133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal S., Van Treuren W., White R. A., Eggesbo M., Knight R., Peddada S. D. (2015). Analysis of composition of microbiomes: a novel method for studying microbial composition. Microb. Ecol. Health. Dis. 26:27663. 10.3402/mehd.v26.27663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin-Neto J. A., Cunha-Neto E., Maciel B. C., Simoes M. V. (2007). Pathogenesis of chronic Chagas heart disease. Circulation 115, 1109–1123. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.624296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall L. I., Tripathi A., Vargas F., Knight R., Dorrestein P. C., Siqueira-Neto J. L. (2018). Experimental Chagas disease-induced perturbations of the fecal microbiome and metabolome. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 12:e0006344. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McInnes P., Cutting M. (2010). Manual of Procedures for Human Microbiome Project. Core microbiome sampling protocol A, HMP protocol # 07-001 [Online]. Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gap/cgi-bin/GetPdf.cgi?id=phd003190.2 (Accessed November 6, 2018).

- Medeiros N. I., Gomes J. A. S., Fiuza J. A., Sousa G. R., Almeida E. F., Novaes R. O., et al. (2019). MMP-2 and MMP-9 plasma levels are potential biomarkers for indeterminate and cardiac clinical forms progression in chronic Chagas disease. Sci. Rep. 9:14170. 10.1038/s41598-019-50791-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagajyothi F., Weiss L. M., Zhao D., Koba W., Jelicks L. A., Cui M. H., et al. (2014). High fat diet modulates Trypanosoma cruzi infection associated myocarditis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 8:e3118. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira Junior L. R., Carvalho T. B., Santos R. M. D., Costa E., Pereira P. C. M., Kurokawa C. S. (2019). Association of vitamin D3, VDR gene polymorphisms, and LL-37 with a clinical form of Chagas Disease. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 52:e20190133. 10.1590/0037-8682-0133-2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAHO (2016). “General Information - Chagas Disease: PAHO/WHO Sub-regional Initiatives,” in Pan American Health Organization. Available online at: https://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=5856:2011-informacion-general-enfermedad-chagas&Itemid=40370&lang=en

- Panek M., Cipcic Paljetak H., Baresic A., Peric M., Matijasic M., Lojkic I., et al. (2018). Methodology challenges in studying human gut microbiota - effects of collection, storage, DNA extraction and next generation sequencing technologies. Sci. Rep. 8:5143. 10.1038/s41598-018-23296-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin J., Li Y., Cai Z., Li S., Zhu J., Zhang F., et al. (2012). A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature 490, 55–60. 10.1038/nature11450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassi A., Jr., Rassi A., Marin-Neto J. A. (2010). Chagas disease. Lancet 375, 1388–1402. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60061-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis P. G., Ayo C. M., de Mattos L. C., Brandao de Mattos C. C., Sakita K. M., de Moraes A. G., et al. (2017). Genetic Polymorphisms of IL17 and Chagas Disease in the South and Southeast of Brazil. J. Immunol. Res. 2017:1017621. 10.1155/2017/1017621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robello C., Maldonado D. P., Hevia A., Hoashi M., Frattaroli P., Montacutti V., et al. (2019). The fecal, oral, and skin microbiota of children with Chagas disease treated with benznidazole. PLoS ONE 14:e0212593 10.1371/journal.pone.0212593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Routy B., Le Chatelier E., Derosa L., Duong C. P. M., Alou M. T., Daillere R., et al. (2018). Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science 359, 91–97. 10.1126/science.aan3706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabino E. C., Lee T. H., Montalvo L., Nguyen M. L., Leiby D. A., Carrick D. M., et al. (2013). Antibody levels correlate with detection of Trypanosoma cruzi DNA by sensitive polymerase chain reaction assays in seropositive blood donors and possible resolution of infection over time. Transfusion 53, 1257–1265. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2012.03902.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Alcoholado L., Castellano-Castillo D., Jordan-Martinez L., Moreno-Indias I., Cardila-Cruz P., Elena D., et al. (2017). Role of gut microbiota on cardio-metabolic parameters and immunity in coronary artery disease patients with and without type-2 diabetes mellitus. Front. Microbiol. 8:1936. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saulnier D. M., Riehle K., Mistretta T. A., Diaz M. A., Mandal D., Raza S., et al. (2011). Gastrointestinal microbiome signatures of pediatric patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 141, 1782–1791. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield C. J., Jannin J., Salvatella R. (2006). The future of Chagas disease control. Trends Parasitol. 22, 583–588. 10.1016/j.pt.2006.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira A. R., Nascimento R. J., Sturm N. R. (2006). Evolution and pathology in chagas disease–a review. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 101, 463–491. 10.1590/s0074-02762006000500001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tito R. Y., Chaffron S., Caenepeel C., Lima-Mendez G., Wang J., Vieira-Silva S., et al. (2019). Population-level analysis of Blastocystis subtype prevalence and variation in the human gut microbiota. Gut 68, 1180–1189. 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villarino N. F., LeCleir G. R., Denny J. E., Dearth S. P., Harding C. L., Sloan S. S., et al. (2016). Composition of the gut microbiota modulates the severity of malaria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 2235–2240. 10.1073/pnas.1504887113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Y., Wang F., Yuan J., Li J., Jiang D., Zhang J., et al. (2019). Effects of dietary fat on gut microbiota and faecal metabolites, and their relationship with cardiometabolic risk factors: a 6-month randomised controlled-feeding trial. Gut 68, 1417–1429. 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2015). Chagas disease in Latin America: an epidemiological update based on 2010 estimates. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 90, 33–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Kobert K., Flouri T., Stamatakis A. (2014). PEAR: a fast and accurate Illumina Paired-End reAd mergeR. Bioinformatics 30, 614–620. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Beta diversity plots for non-phylogenetic (Bray-Curtis and Jaccard) and phylogenetic (weighted and unweighted UniFrac) methods in control and the Chagas disease phenotypes (indeterminate, cardiac and megacolon).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study can be found in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), PRJNA471615.