Abstract

In this study we developed a brief, English/Spanish bilingual parent-reported scale of perceived community autism spectrum disorder (ASD) stigma and tested it in a multi-site sample of Latino and non-Latino white parents of children with ASD. Confirmatory factor analysis of the scale supported a single factor solution with 8 items showing good internal consistency. Regression modeling suggested that stigma score was associated with unmet ASD care needs but not therapy hours or therapy types. Child public insurance, parent nativity, number of children with ASD in the household, parent-reported ASD severity, and family structure, were associated with higher stigma score. The scale and the scale’s associations with service use may be useful to those attempting to measure or reduce ASD stigma.

Keywords: Autism Spectrum Disorder, Stigma, Mental Health Services, Developmental Disability, Healthcare Disparities, Health Care Surveys

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is associated with high family stress (Zuckerman et al. 2014a; Schieve et al. 2007), and most children with ASD do not receive all of the health and educational services that might benefit them (Zuckerman et al. 2017). One reason for family stress and low rates of service use may be parent or caregiver perceptions of stigma associated with ASD.

Stigma describes prejudicial attitudes, negative stereotypes, and discrimination targeting a subgroup (Corrigan 2000; Mukolo et al. 2010). This targeted group often experiences, to varying degrees, the process of labeling, stereotyping, separation, emotional reaction, status loss, and discrimination (Green et al. 2005; Link and Phelan 2001). Various forms of stigma have been identified in the medical and sociological literature. Public stigma is defined as stigma of the general public toward the affected person directly (Corrigan et al. 2012), and has well-documented negative effects on the individual, such as poor employment outcomes ( Link 1982) and lack of access to mental health services (Corrigan 2004). Relatedly, the perception of stigma from others, also known as “perceived stigma” or “perceived public stigma”, has also been shown to have a negative effect on mental health care seeking, both for individuals (Pedersen and Paves 2014; Vogel et al. 2007; Golberstein et al. 2008), and from parents of children with chronic mental or behavioral conditions (Gray 1993; dosReis et al. 2010). Perceived stigma is important, because it can lead to both social censure (Phelan et al. 1998) and internalization of public stigma (sometimes called “affiliate stigma” or “courtesy stigma”) (Mak and Cheung 2008; Mak and Kwok 2010). For instance, stigma directed toward children with developmental disabilities has been shown to be associated with parental stress and lack of well-being (Ali et al. 2012).

Among families of children with ASD, several studies have confirmed that experiences of public and affiliate stigma are common (Gray 1993; Kinnear et al. 2016; Mak and Kwok 2010; Gray 2002), and may have negative effects on both affected children and their caregivers (Kinnear et al. 2016; Gray 1993). As Gray was first to note, some of these stigmatizing experiences may be particular to ASD because core ASD symptoms (e.g. repetitive behaviors, lack of social awareness) can be disruptive in nature; however, children often show a normal physical appearance (Gray 1993). Additionally, though public knowledge about ASD has increased (Dillenburger et al. 2013), the general public often lacks information needed to recognize disruptive behaviors as signs of ASD, which makes stigmatizing experiences more likely for families. This hypothesis was supported by a 2015 study in which Werner and colleagues found that affiliate stigma was higher among families of children with ASD compared to families of children with intellectual disabilities (ID) or physical disabilities (Werner and Shulman 2015). Child and family factors shown to be associated with perceived stigma among children with ASD include older caregiver age, having a caregiver with older children (Chiu et al. 2013; Mak and Kwok 2010), the child being more severely affected by ASD (e.g., moderate or severe ASD, dual diagnosis of ID and ASD, more aggression), and younger child age (Gray 1993; Mak and Cheung 2008; Mak and Kwok 2010). Other factors also may influence perceived stigma, such as family race/ethnicity, educational attainment social context, family education about mental health specifically and history interpersonal contact with members of a stigmatized group (Corrigan et al. 2012; P.W. Corrigan and Watson 2007; Ng 1997); however these factors have not been studied for ASD particularly.

A limitation of the existing research on stigma in ASD is that most studies have either been qualitative or have taken place in non-English speaking countries, both of which pose generalizability problems for US samples. In particular, though mental health stigma may be present in all societies, its specific manifestations may vary by culture (Abdullah and Brown 2011), so specific studies in US samples are needed. Only one quantitative study of parent-perceived ASD stigma has been conducted in the US (Kinnear et al. 2016). This study, which investigated the effects of stigma on parents of children with ASD, used a multi-site sample of 502 US families from the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative Simons Simplex Collection. This study showed that nearly all (95%) parents in the sample felt stigmatized by their child’s ASD, and that stigma played a significant role in parents’ perceptions regarding the difficulty of raising a child with ASD.

Current Study

This current study sets out to fill several gaps in the literature about perceived stigma among families of children with ASD. First, most studies of parent-perceived stigma in ASD have focused on the effects of stigma on parenting and family well-being (i.e., courtesy and/or affiliate stigma). However, perceived ASD stigma may also be an important determinant of health services use for ASD. The Kinnear study (2016) suggested that ASD-related stigma was a major factor that “made caregivers’ lives more difficult,” and this difficulty may extend into service access for children – for instance, a parent may be less likely to seek out ASD services for their child if they feel the diagnosis is stigmatized (Zuckerman et al. 2014b). Parents who experience stigma may also experience difficulty engaging their child in ASD-related services if the diagnosis is stigmatized by the community in general. However, our knowledge, there are no studies linking the stigma perceived by families to ASD-related service use in children. Second, the study by Kinnear and colleagues is the only large-scale US study of ASD stigma, but it had over 80% non-Latino white participants. As the experience of ASD stigma may vary by language and culture (Mak and Kwok 2010), additional research is needed to characterize stigma in culturally and linguistically diverse US samples. Relatedly, few validated measures of parent-perceived ASD stigma exist, and none of the available stigma measures are brief (i.e., less than 20 items), written at a low reading level, and validated in Spanish. Such an instrument is needed for more routine measurement of ASD stigma in US research studies.

This study’s aims were three-fold. First, we sought to develop and test the validity of a brief, English and Spanish measure of stigma perceived by parents of US children with ASD. Such an effort would be helpful to researchers and clinicians seeking to methodically measure perceived ASD stigma. Second, we sought to assess variation in ASD stigma by child and family demographics. Understanding how perceived stigma varies by culture could help target resources toward those subgroups that experience the most stigma. Third, we sought to measure the association of perceived ASD stigma with ASD services use and unmet ASD service need among children with ASD. Such associations, if present, would suggest that parent-perceived stigma could be a target for future interventions to improve access to ASD services.

METHODS

Study Sample and Design

This project was part of a larger multi-site survey of Latino and non-Latino white parents of children with confirmed ASD. The survey took place in 2014 and 2015 at three ASD specialty clinics in Los Angeles, California; Denver, Colorado; and Portland, Oregon. All clinics were current or former members of the Autism Speaks Autism Treatment Network, and thus they had similar ASD diagnostic processes. The study design and enrollment process has been previously described (Zuckerman et al., 2017). The primary focus of the overall survey was on barriers to early ASD identification in non-Latino white and Latino families.

To be included in the study, the participant had to be the parent of a child age 2-10 years, who was seen for a visit at one of the three specialty clinics, and who had an ASD diagnosis confirmed in the last five years with a multidisciplinary ASD evaluation (including use of the Autism Diagnostic Observational Schedule and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM]-IV-TR or DSM-V criteria). Because this survey was part of a larger study on autism among Latinos, inclusion criteria also required children identifying as Latino or non-Latino white. As more potential participants existed than were required for the initial study, a random sample of medical records was selected at each site. Families were subsequently excluded if their child had a significant comorbid developmental syndrome (e.g., Down syndrome, Tuberous Sclerosis), if the child was in foster care, if the mother was younger than 18, or if families spoke neither English nor Spanish. Eligible families (n=489) were mailed a survey in English or Spanish. Participants who did not complete written surveys were offered telephone administration with a bilingual research assistant. Each site’s Institutional Review Board independently approved the study protocol; consent was implied by written or oral survey completion.

Survey Development

If available, validated and previously used measures were used in developing the survey. All demographic items were adapted from the 2009-10 National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs (National Center for Health Statistics 2013) and the US Census American Community Survey (United States Census Bureau 2015). Since there existed no validated measures of parent-perceived ASD stigma suitable to the study population, new items about stigma were developed by the study team based on themes generated during English- and Spanish-language focus groups of parents of children with ASD that the research team conducted the same year (Zuckerman et al., 2017). The survey was translated into Spanish by a bilingual/bicultural professional translator, and then reviewed by two other bilingual/bicultural translators of different national origins. Once the initial survey was developed, English and Spanish language cognitive interviews (Fowler 1995) with parents of children with ASD allowed the team, which included a bilingual/bicultural research assistant, to iteratively refine question wording, clarify response options, and assess survey design. Autism Parent Advisory Committees at two sites provided additional feedback on survey wording. The Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level Test was used to adjust the whole survey to a sixth-grade reading level in English and Spanish. The final survey instrument consisted of 34 structured items assessing perceptions of community barriers to ASD diagnosis, ASD stigma, current therapy use, and demographic information. This analysis only examined the latter three survey domains.

Measures

Parent-perceived ASD stigma.

Eleven items addressed parents’ perceptions of ASD stigma in their communities. Each item was prefaced with “These questions are about the views that people in your community have about ASD.” Participants were asked to rate positively- and negatively-phrased statements on a four-point Likert scale ranging from definitely no to definitely yes. Participants were informed that the statements were not meant to represent parents’ personal views or the views of the research team, and were directed to define their community as “people you see or talk to often.” We chose this definition of community so that parents had flexibility to define it as the individuals whose views were important to them. Scale items included negative statements, such as “People in my community think ASD is a result of bad parenting or lack of discipline,” and “People in my community are uncomfortable around my child with ASD,” as well as positive statements such as “People in my community want to learn about ASD.” For full list of scale items see Supplemental Table 1.

Child and family sociodemographic factors.

Child-level characteristic variables included factors known to modify ASD service access (Thomas et al. 2007; Zablotsky et al. 2015) including child age at data collection, child age at the time of diagnosis, child gender, child health insurance type (public health insurance only versus any private health insurance), and parent-reported ASD severity. Family-level factors included ethnicity and parent English proficiency, the respondent’s relationship to child, children with and without ASD per household, family structure, parent educational attainment, and parent employment status.

ASD services use.

We used three measures of ASD service need or use, to take into account the amount, type, and appropriateness of current services a child was receiving. The first measure was the child’s current weekly ASD treatment dose. Participants were asked “How many total hours of home or school therapy services does your child usually receive per week?” Participants could respond in categories ranging from “none” to “more than 20 hours per week.” Since few participants (n = 28 or 8.1%) had more than 20 hours per week of treatment, responses were dichotomized at “10 or fewer hours per week” and “more than 10 hours per week.”

The second measure was of unmet need for ASD-related services. Participants were asked “Does your child receive all the therapy services he/she needs?” Parents could reply “definitely no”, “somewhat no”, “somewhat yes”, or “definitely yes.” Parents who answered “somewhat no” or “definitely no” were defined as having an unmet need for ASD services.

The third measure was of number of types of ASD-related treatments used, including speech and language therapy, social skills training, occupational therapy, behavioral therapy (including applied behavioral analysis), special education/resource room, complementary health approaches, and prescription or over-the counter medications. A median split was used to dichotomize responses as “3 or more treatment types” or “less than 3 treatment types.”

Statistical Analyses

Sample.

Descriptive statistics were first computed for all variables of interest to determine their distributional properties and summarize participant characteristics (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study Sample Characteristics

| Overall % or Mean (SD) (n = 352) |

|

|---|---|

| Child characteristics | |

| Child age, y (n = 343) | |

| Mean (SD) | 5.75 (2.00) |

| Age at time of ASD diagnosis (n = 346) | |

| Mean (SD) | 3.47 (1.42) |

| Gender | |

| Male (n = 291) | 83.6 |

| Female (n = 57) | 16.4 |

| Child health insurance | |

| Public health insurance only (n = 210) | 60.5 |

| Any private health insurance (n = 137) | 39.5 |

| Child ASD severity | |

| Mild (n = 162) | 47.1 |

| Moderate or severe (n = 182) | 52.9 |

| Family characteristics | |

| Family ethnicity and language | |

| Non-Latino, English proficient (n = 163) | 46.3 |

| Latino, English proficient (n = 95) | 27.0 |

| Latino, limited English proficiency (n = 94) | 26.7 |

| Respondent's relationship to child | |

| Mother (n = 316 ) | 90.0 |

| Other (n = 35) | 10.0 |

| Children per household (n = 346) | |

| Mean (SD) | 2.14 (1.09) |

| Children with ASD per household (n = 342) | |

| Mean (SD) | 1.14 (0.44) |

| Family structure | |

| Married or living with partner (n = 278) | 79.2 |

| Single (n = 32) | 9.1 |

| Other (n = 41) | 11.7 |

| Parent education, y (n = 345) | |

| Mean (SD) | 13.65 (3.91) |

| Median | 14.0 |

| Range | 0-25 |

| Parent employment | |

| Unemployed (n = 178) | 50.6 |

| Employed (n = 174) | 49.4 |

| Site | |

| Site 1 (n = 110) | 31.3 |

| Site 2 (n = 114) | 32.4 |

| Site 3 (n = 128) | 36.4 |

Abbreviations: ASD, autism spectrum disorder; L-EP, Latino, English proficient; L-LEP, Latino limited English proficiency; NLW, non-Latino, white, English proficient; SD, standard deviation; y, years.

Scale validity testing.

Internal consistency, as well as item test and item retest correlations were initially computed using all 11 ASD stigma items. Three of the 11 items with low item-test and item-retest correlations were omitted from subsequent analyses (i.e., “People in my community say the child with ASD will grow out of it,” “People in my community say ASD is a medical condition,” and “People in my community think children with ASD have special abilities”). Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with oblique rotation was then performed to help determine the structure of the latent ASD stigma factor using the remaining eight ASD stigma items. EFA results suggested a single factor solution would best fit the data. For this reason, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) model with a single factor solution was then fit. Both EFA and CFA models were fit using the robust diagonally weighted least squares estimator in Mplus 7.3. In the final CFA model, the measurement residuals of the items “People in my community want to learn about ASD” and “People in my community try to help my child and our family” were correlated because these two items both had potentially positive implications regarding ASD relative to the other six ASD stigma items.

Because the data fit the CFA model with a single factor, suggesting one unidimensional latent variable of ASD stigma is reflected by the eight ASD stigma items, we used the row mean of the eight items in the subsequent analyses intended to better understand associations of child and family factors with ASD stigma, as well as the scale’s concurrent validity with respect to its correlations with ASD services use. For the row mean of ASD stigma, positively phrased items (e.g., “People in my community want to learn about ASD”) were reverse-scored (Supplemental Table 1). Lower scores indicated less ASD stigma, and higher scale scores indicated more ASD stigma.

Associations of child and family sociodemographic factors with ASD stigma.

Wilcoxon rank sum and Kruskal Wallis tests were used to examine variation in mean stigma score by child and family factors and site (Table 2). A multivariable linear regression model was then fit to determine associations of child and family factors as well as site with ASD stigma (Table 3). In this model, the stigma score was the dependent variable and all of the child and family factors in Table 2 with at least marginally significant associations (p<0.10) were included as model covariates. The model was also adjusted for study site.

Table 2.

Mean Community ASD Stigma, by Child , Family, and Site Characteristics (N = 352)

| Mean (SD)a | |

|---|---|

| Overall | 2.31 (0.60) |

| Child characteristics | |

| Child age | |

| Six years or older (n =174) | 2.28 (0.61) |

| Younger than six years (n = 166) | 2.34 (0.60) |

| p-value | 0.39 |

| Age at time of ASD diagnosis | |

| Three years or younger (n = 187) | 2.35 (0.60) |

| Older than 3 years (n = 156) | 2.28 (0.61) |

| p-value | 0.33 |

| Gender | |

| Male (n = 288) | 2.29 (0.59) |

| Female (n = 57) | 2.41 (0.65) |

| p-value | 0.23 |

| Child health insurance | |

| Public health insurance only (n = 209) | 2.45 (0.61) |

| Any private health insurance (n = 135) | 2.10 (0.55) |

| p-value | <0.001 |

| Child ASD severity | |

| Mild (n = 160) | 2.16 (0.56) |

| Moderate or severe (n = 181) | 2.45 (0.60) |

| p-value | <0.001 |

| Family Characteristics | |

| Family ethnicity and language | |

| Non-Latino, white, English proficient (n = 163) | 2.24 (0.62) |

| Latino, English proficient (n = 95) | 2.25 (0.59) |

| Latino, limited English proficiency (n = 94) | 2.51 (0.56) |

| p-value | <0.001 |

| Respondent's relationship to child | |

| Mother (n = 313) | 2.34 (0.61) |

| Other (n = 35) | 2.10 (0.54) |

| p-value | 0.03 |

| Children per household | |

| 1-2 children (n = 246) | 2.28 (0.62) |

| > 2 children (n = 97) | 2.40 (0.58) |

| p-value | 0.09 |

| Children with ASD per household (n = 339) | |

| One child with ASD (n = 300) | 2.27 (0.60) |

| Two or more children with ASD (n = 39) | 2.70 (0.54) |

| p-value | <0.001 |

| Parent nativity | |

| Always lived in U.S. (n = 226) | 2.23 (0.61) |

| Lived outside the U.S. (n = 123) | 2.48 (0.56) |

| p-value | <0.001 |

| Years lived in the U.S. | |

| >15 years (n = 50) | 2.36 (0.49) |

| Fifteen years or less (n = 73) | 2.55 (0.59) |

| p-value | 0.07 |

| Family structure | |

| Married or living with partner (n = 275) | 2.26 (0.58) |

| Single (n = 32) | 2.42 (0.67) |

| Other (n = 41) | 2.57 (0.64) |

| p-value | 0.005 |

| Parent education | |

| More than 12 years (n = 197) | 2.26 (0.62) |

| 12 years or less (n = 145) | 2.39 (0.58) |

| p-value | 0.034 |

| Parent employment | |

| Employed (n = 172) | 2.22 (0.59) |

| Unemployed (n = 177) | 2.40 (0.60) |

| p-value | 0.004 |

| Site | |

| Site 1 (n = 115) | 2.23 (0.57) |

| Site 2 (n = 120) | 2.29 (0.62) |

| Site 3 (n = 135) | 2.40 (0.61) |

| p-value | 0.08 |

Abbreviations: ASD, autism spectrum disorder; SD, standard deviation.

Differences in the distribution of community stigma by binary variables determined using a Wilcoxon rank sum test and differences in the distribution of community stigma by nominal variables determined using a Kruskall Wallis test.

Bolded p-values indicate variables included in multivariable models.

Table 3.

Child, Family, and Site Associations with ASD Stigma Score: Multiple Linear Regression Model Results (n = 352)

| Adjusted Beta Coefficients |

|

|---|---|

| Constant (intercept) | 1.81 (1.30, 2.32)b |

| Child characteristics | |

| Child health insurance | |

| Public health insurance only (n = 209) | ref |

| Any private health insurance (n = 135) | −0.25 (−0.41, −0.09)a |

| Child ASD severity | |

| Mild (n = 160) | ref |

| Moderate or severe (n = 181) | 0.18 (0.04, 0.33)a |

| Family characteristics | |

| Family ethnicity and language | |

| Non-Latino, white, English proficient (n = 163) | ref |

| Latino, English proficient (n = 95) | −0.01 (−0.17, 0.15) |

| Latino, limited English proficiency (n = 94) | −0.05 (−0.32, 0.23) |

| Respondent's relationship to child | |

| Mother (n = 313) | ref |

| Other (n = 35) | −0.19 (−0.41, 0.04) |

| Children per household (n = 343) | 0.01 (−0.06, 0.08) |

| Children with ASD per household (n = 339) | 0.25 (0.08, 0.42)a |

| Parent nativity | |

| Always lived in U.S. (n = 226) | ref |

| Lived outside the U.S. (n = 123) | 0.22 (0.002, 0.44) |

| Family structure | |

| Married or living with partner (n = 275) | ref |

| Single (n = 32) | 0.07 (−0.18, 0.32) |

| Other (n = 41) | 0.28 (0.08, 0.49)a |

| Parent education, years (n = 342) | 0.01 (−0.02, 0.03) |

| Parent employment | |

| Employed (n = 172) | ref |

| Unemployed (n = 177) | 0.04 (−0.10, 0.18) |

| Site | |

| Site 1 (n = 115) | ref |

| Site 2 (n = 120) | 0.01 (−0.16, 0.18) |

| Site 3 (n = 135) | 0.02 (−-.15, 0.20) |

Abbreviations: ASD, autism spectrum disorder; CI, confidence interval Bold denotes the value is significant at P<0.05.

P<0.01

P<0.001

Only variables that had a significant association (P<.10) at bivariate level were included in the model.

Associations of ASD stigma with ASD services use and need.

Bivariate and multivariable logistic regression models were fit to determine associations of perceived ASD stigma with ASD services use, including 11 or more weekly treatment hours, any unmet need for ASD services, and use of three or more service modalities. In multivariable models, each service use variable was the dependent variable, the stigma score was the primary independent variable, and all child or family factors that had marginally significant associations with community stigma along with site were also included. Finally, to understand unmet need in the context of service use, a logistic regression model for unmet need for ASD care was created that also included treatment types and treatment hours as covariates. All descriptive and regression analyses were performed with Stata 14.0.

RESULTS

Study Sample

Of the 489 participants contacted, 380 completed the survey yielding a response rate of 76.2% (American Association for Public Opinion Research). Consistent with epidemiological studies of ASD’s gender distribution (Christensen et al. 2016), 84.0% of participants had a male child with ASD. Mean child age at the time of data collection was 5.8 years (standard deviation [SD]=2.0), and mean child age at the time of ASD diagnosis was 3.5 years (SD=1.4). Most children (60.6%) had public health insurance only. About half (52.8%) of participants reported their child’s ASD severity as moderate or severe (Table 1).

Per the study design, about half of participants were non-Latino, white, and English proficient (46.3%). Latino participants were divided between those with English proficiency (27.0%) and those with limited English proficiency (26.7%). A majority of Latinos were of Mexican origin/heritage (78.7%). Most participants were mothers (89.3%), US-natives (64.8%), and married or living with a partner (79.3%). Mean parent education was 13.7 years (SD=3.9). Half of participants were unemployed (50.6%).

Scale Properties

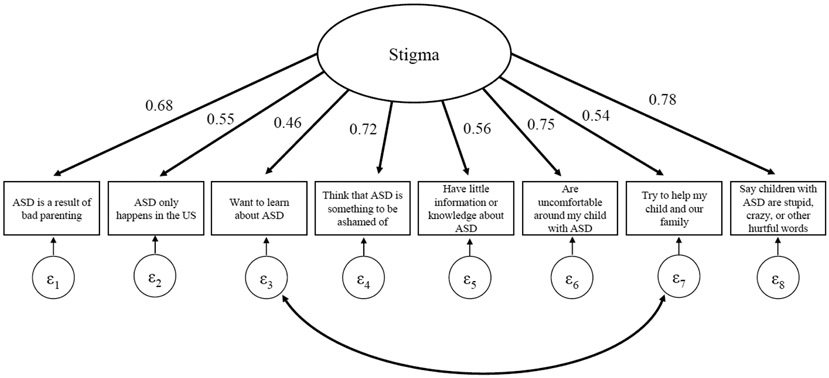

Supplemental Table 1 shows the distribution for each candidate scale item. The most frequently endorsed items (agree or definitely agree) were “People in my community have little information or knowledge about ASD,” (83.2% stating somewhat or definitely yes) and “People in my community are uncomfortable around my child with ASD” (55.2% saying somewhat or definitely yes). EFA results supported a single factor solution with eight of the ASD stigma items; these eight items demonstrated high internal consistency (α=0.80). The CFA model fit the data well: χ2 (19)=56.36, p < .001; RMSEA=0.075; CFI=0.944, TLI=0.917 (Figure 1, Supplemental Table 2).

Figure 1.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis Model Results: Single Factor Solution for 8 Community ASD Stigma Items (n = 352)

Model Fit Statistics: χ2(19) = 67.28, p < .001; RMSEA = 0.083; CFI = 0.967, TLI = 0.951; α = 0.7965

All factor loadings standardized and statistically significant, p < .001.

Associations of child and family factors with perceived ASD stigma

The mean stigma score for the entire sample was 2.31 out of a maximum score of 4.00. This demonstrates that a majority of families were responding “somewhat yes” or “definitely” yes to one or more items indicating ASD stigma. On biviarate analysis, higher scores were associated with child public insurance (p<0.001), mother respondent (p=0.03), higher parent-reported severity (p<0.001), number of children with ASD per household (p<0.001), Latino, limited English proficient ethnic/language category (p<0.001), non-US parent nativity (p<0.001), lower parent educational attainment (p=0.03), “other” family structure (p=0.005) and parental unemployment (p =0.004). On multivariable analysis, positive associations with stigma persisted for the factors public insurance status, parent-reported severity, number of children with ASD per household, non-US parent nativity, and “other” family structure (Table 3).

Associations of ASD stigma with ASD service use

Overall 21.2% of parents were using 11 or more treatment hours for ASD, 30.0% were using 3 or more types of ASD services, and 49.0% of parents reported unmet needs for ASD care. On bivariate and multivariable analysis there was no statistically significant association between stigma score and receipt of 11 or more treatment hours for ASD. Likewise, there was no statistically significant association of ASD stigma with the use of three or more treatment types. However, there was a significant positive association between stigma score and unmet need for ASD treatment on both bivariate and multivariable analyses (Adjusted Odds Ratio [aOR] 3.59, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.17-5.91). In the multivariable model in which unmet need for ASD treatment was adjusted for receipt of 11 or more treatment hours and types of ASD services, a strong association between unmet need and stigma score persisted (Table 4).

Table 4.

Service use associations with ASD Stigma: Logistic regression model results

| Unadjusted association with ASD Stigma (Odds Ratio with 95% Confidence Interval) |

Adjusted association with ASD Stigmab (Adjusted Odds Ratio with 95% Confidence Interval) |

|

|---|---|---|

| ASD-related treatment | ||

| 11 or more treatment hours | 0.76 (0.49–1.16) | 0.71 (0.41–1.22) |

| More than 3 treatment types | 1.07 (0.76-1.51) | 0.89 (0.58-1.18) |

| Any unmet need for ASD treatment | 2.73 (1.89–4.00)a | 3.59 (2.17–5.91)a |

| Adjusted OR Unmet need for ASD treatment (includes treatment hours and treatment types as covariates) | -- | 3.44 (2.07-5.71)a |

P<0.001

Adjusted models include all child and family factors with p<0.10 in Table 2 and site.

DISCUSSION

The goals of this analysis were to develop and validate a scale of parent-perceived stigma among US children with ASD, to examine socio-demographic variation in stigma, and to examine the relationship between parent-perceived stigma and need for and use of ASD-related services. The scale that we developed is brief, has a low reading level, and can be used in English or Spanish by parents of children with ASD. Given the survey’s high response rate, the scale was acceptable to families. This scale can be used by researchers intending to measure the effect of community stigma on ASD outcomes. The scale also has potential clinical use in assessing how much stigma parents of children with ASD perceive, so that practitioners could seek to address it.

The scale has 11 items, 8 of which can be used to generate a mean stigma score. A higher mean score on the scale can be seen to reflect higher levels of parent-perceived ASD community stigma. Our study shows that higher scores are associated with unmet need for ASD care but not current treatment hours for ASD. Although three items do not contribute to the scoring algorithm, we recommend that all 11 items be included, because the three non-scoring items (“people in my community tell me that my child with ASD will grow out of it,” “…think that ASD is a medical condition,” and “…think children with ASD have special abilities”) are some of the more positively phrased items; eliminating them may reduce acceptability to families.

Our study showed that ASD stigma score, as measured by this scale, shows socio-demographic variation. In particular, families from traditionally marginalized groups (e.g., publicly-insured families, families with lower parental education, non-US native parents, Latino parents with limited English proficiency) were more likely to have higher stigma scores on bivariate and/or multivariable analysis. These findings are consistent with prior literature on stigma; as Hatzenbuehler and colleagues have observed (2013), stigma and social determinants of health may have a reciprocal relationship: parents who are from marginalized backgrounds may be experiencing more stigma, both from their child’s ASD and from being associated with a marginalized group themselves (e.g., immigrant, low-income); this stigma may be further preventing them from obtaining needed resources to improve their child’s health and functioning, which might reduce disability-related stigma. Such a finding is also consistent with observations we made in the preliminary focus groups with Latino parents, where they reported many experiences of mental health and disability stigma, particularly from less-acculturated community members, and that parents view this stigma as one cause for delayed care-seeking for their child (Zuckerman 2014b). In addition, we found that families who had children with moderate to severe ASD, or who had more children with ASD per household, also perceived more stigma. These findings are consonant with Kinnear’s findings that parents experience higher rates of stigma when their children display high rates of autism-related behaviors (Kinnear 2016).

The finding that parent-perceived stigma was associated with unmet needs for ASD care, regardless of current treatment hours, or number of types of treatments used, also raises important questions that could be answered in future research. The findings suggest that perhaps stigma is more strongly associated with decreases in perceived or actual quality of care than it is with type or amount of care per se. That is, parents who experience stigma may be experiencing more unmet needs for care, even when the amount and types of care their child is getting is similar to parents who do not experience stigma. Since many groups who experienced the most stigma in the US (e.g., immigrants, families with lower education) are also groups that generally receive less care and lower-quality care for ASD (Leigh et al. 2016; Durkin et al. 2010; Liptak et al. 2008; Magaña et al. 2012), the study’s findings suggest that intervening to reduce stigma in these groups could potentially reduce unmet care needs, even if the actual amount of care does not increase or change. Conversely, it also could be that if families’ care needs are met, they will feel less stigma as a result of their child’s ASD. However, since the survey was cross-sectional, and measures of type and dose of care were limited, we cannot be certain for the reasons why stigma was associated with unmet care need.

This study had a number of strengths. It used a large, multi-site sample of children and families with ASD, and had a strong response rate among both white non-Latino and Latino families. The study is also the first to look at the relationship between parent-perceived stigma and child service use for ASD, a topic that is frequently raised in the area of ASD disparities, but which is rarely measured. However, given that this is the first study to use this scale and examine its associations, results should be interpreted with caution.

The most significant limitation of this study is that no data were collected from families who were not Latino or non-Latino white, due to the structure of the larger study from which these data were drawn. Though this allowed for strong socio-demographic comparisons between Latino and non-Latino white parents, and among Latino subgroups, study findings cannot be generalized to other groups. Still, non-Latino white and Latino children together comprise more than 75% of the the US child population (Childstats.gov Forum on Child and Family Statistics 2016), so the scale is generalizable to a broad portion of US children. However, further research is needed to understand how the scale functions in other racial/ethnic groups, particularly Asian Americans and African Americans. Furthermore, because the study sample was comprised of families living in the US, using the measure with similar populations in other countries (e.g., Latinos living in Latin America) also warrants additional research. The survey’s sample size (380), and sampling from only 3 health care settings also limits precision and generalizability.

An additional limitation is that service use characteristics were parent-reported, which may impact the accuracy and precision of service use estimates. For instance, children in this study were reported to use autism services at relatively low rates, which may underestimate actual service use rates, since parents may not be aware of all of the services a child gets in the school setting. On the other hand, these numbers could also be overestimates of national use patterns, since the sample was drawn from children seen for care at autism referral center. Another limitation is that completing a survey about stigma may in itself be stigmatizing; thus, the study as a whole may have been subject to positivity bias. We sought out parent input throughout this research project in order to make the survey as acceptable as possible to parents; we feel that the survey’s high response rate suggests that acceptability was adequate. Likewise, though the survey had a high response rate, it is possible that non-responders had different experiences of stigma in their community, so non-response bias is a concern. Finally, since all stigma items started with “people in my community” some participants may have had trouble identifying their “community,” or may have varied in their conception of their community, which would lead to unmeasured variation in response patterns.

Conclusions

In this multi-site study, parent-perceived stigma was common for families of children with ASD, and was measurable using a standardized scale. Latino immigrant families, publicly insured families, families of more severely affected children, and families with multiple children having ASD experienced the most perceived stigma. Stigma was found to be associated with unmet needs for ASD care. More research is needed to elucidate the mechanisms through which perceived stigma may impact parents’ needs for ASD care. Future research is also needed to better understand whether addressing stigma might reduce ASD disparities and improve ASD care quality.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This grant was funded by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Footnotes

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. As the project was deemed minimal risk, the IRB allowed an information sheet to serve as the consent document, and consent was implied by completion of the survey.

REFERENCES

- Abdullah T, & Brown TL (2011). Mental illness stigma and ethnocultural beliefs, values, and norms: An integrative review. Clinical psychology review, 31(6), 934–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali A, Hassiotis A, Strydom A, & King M (2012). Self stigma in people with intellectual disabilities and courtesy stigma in family carers: A systematic review. Research in developmental disabilities, 33(6), 2122–2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Association for Public Opinion Research Response rate--An overview. http://www.aapor.org/Response_Rates_An_Overview1.htm. Accessed December 2016.

- Childstats.gov Forum on Child and Family Statistics (2016). Pop3 Race and Hispanic origin composition: Percentage of U.S. Children ages 0–17 by race and hispanic origin, 1980–2016 and projected 2017–2050. https://www.childstats.gov/americaschildren/tables/pop3.asp. Accessed November 2017.

- Chiu MY, Yang X, Wong F, Li J, & Li J (2013). Caregiving of children with intellectual disabilities in China–an examination of affiliate stigma and the cultural thesis. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 57(12), 1117–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen DL, Baio J, Braun KV, Bilder D, Charles J, Constantino JN, et al. (2016). Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years - Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Surveillance Summaries, 65(3), 1–23, doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6503a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW (2000). Mental health stigma as social attribution: Implications for research methods and attitude change. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 7(1), 48–67. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW (2004). How stigma interferes with mental health care. American Psychologist, 59(7), 614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Morris SB, Michaels PJ, Rafacz JD, & Rüsch N (2012). Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: a meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatric Services, 63(10), 963–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, & Watson AC (2007). The stigma of psychiatric disorders and the gender, ethnicity, and education of the perceiver. Community mental health journal, 43(5), 439–458, doi: 10.1007/s10597-007-9084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillenburger K, Jordan JA, McKerr L, Devine P, & Keenan M (2013). Awareness and knowledge of autism and autism interventions: A general population survey. Research in autism spectrum disorders, 7(12), 1558–1567, doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2013.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- dosReis S, Barksdale CL, Sherman A, Maloney K, & Charach A (2010). Stigmatizing experiences of parents of children with a new diagnosis of ADHD. Psychiatric Services, 61(8), 811–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkin MS, Maenner MJ, Meaney FJ, Levy SE, DiGuiseppi C, Nicholas JS, et al. (2010). Socioeconomic inequality in the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder: evidence from a U.S. cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE, 5(7), e11551, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler FJ (1995). Improving survey questions. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Golberstein E, Eisenberg D, & Gollust SE (2008). Perceived stigma and mental health care seeking. Psychiatric Services, 59(4), 392–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray DE (1993). Perceptions of stigma: The parents of autistic children. Sociology of Health & Illness, 15(1), 102–120. [Google Scholar]

- Gray DE (2002). ‘Everybody just freezes. Everybody is just embarrassed’: Felt and enacted stigma among parents of children with high functioning autism. Sociology of Health & Illness, 24(6), 734–749. [Google Scholar]

- Green S, Davis C, Karshmer E, Marsh P, & Straight B (2005). Living stigma: The impact of labeling, stereotyping, separation, status loss, and discrimination in the lives of individuals with disabilities and their families. Sociological Inquiry, 75(2), 197–215, doi: 10.1111/j.1475-682X.2005.00119.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, & Link BG (2013). Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 813–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnear SH, Link BG, Ballan MS, & Fischbach RL (2016). Understanding the experience of stigma for parents of children with autism spectrum disorder and the role stigma plays in families’ lives. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(3), 942–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh JP, Grosse SD, Cassady D, Melnikow J, & Hertz-Picciotto I (2016). Spending by California’s Department of Developmental Services for persons with autism across demographic and expenditure categories. PLoS ONE, 11(3), e0151970, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link B (1982). Mental patient status, work, and income: An examination of the effects of a psychiatric label. American Sociological Review, 202–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, & Phelan JC (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual review of Sociology, 27(1), 363–385. [Google Scholar]

- Liptak GS, Benzoni LB, Mruzek DW, Nolan KW, Thingvoll MA, Wade CM, et al. (2008). Disparities in diagnosis and access to health services for children with autism: data from the National Survey of Children’s Health. Journal of developmental and behavioral pediatrics : JDBP, 29(3), 152–160, doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318165c7a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magaña S, Parish SL, Rose RA, Timberlake M, & Swaine JG (2012). Racial and ethnic disparities in quality of health care among children with autism and other developmental disabilities. Intellectual and developmental disabilities, 50(4), 287–299, doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-50.4.287; 10.1352/1934-9556-50.4.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak WW, & Cheung RY (2008). Affiliate stigma among caregivers of people with intellectual disability or mental illness. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 21(6), 532–545. [Google Scholar]

- Mak WW, & Kwok YT (2010). Internalization of stigma for parents of children with autism spectrum disorder in Hong Kong. Social science & medicine, 70(12), 2045–2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukolo A, Heflinger CA, & Wallston KA (2010). The stigma of childhood mental disorders: A conceptual framework. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(2), 92–103, doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics (2013). 2009–10 National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/slaits/NS_CSHCN_Questionnaire_09_10.pdf. Accessed November 2017.

- Ng CH (1997). The stigma of mental illness in Asian cultures. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 31(3), 382–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ER, & Paves AP (2014). Comparing perceived public stigma and personal stigma of mental health treatment seeking in a young adult sample. Psychiatry Research, 219(1), 143–150, doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan JC, Bromet EJ, & Link BG (1998). Psychiatric illness and family stigma. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 24(1), 115–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieve LA, Blumberg SJ, Rice C, Visser SN, & Boyle C (2007). The relationship between autism and parenting stress. Pediatrics, 119 Suppl 1, S114–121, doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2089Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas KC, Ellis AR, McLaurin C, Daniels J, & Morrissey JP (2007). Access to care for autism-related services. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(10), 1902–1912, doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0323-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau (2015). U.S. Census American Communities Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/. Accessed June 2017.

- Vogel DL, Wade NG, & Hackler AH (2007). Perceived public stigma and the willingness to seek counseling: The mediating roles of self-stigma and attitudes toward counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54(1), 40. [Google Scholar]

- Werner S, & Shulman C (2015). Does type of disability make a difference in affiliate stigma among family caregivers of individuals with autism, intellectual disability or physical disability? Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 59(3), 272–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zablotsky B, Pringle BA, Colpe LJ, Kogan MD, Rice C, & Blumberg SJ (2015). Service and treatment use among children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics : JDBP, 36(2), 98–105, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman KE, Friedman NDB, Shui AM, Chavez AE, & Kuhlthau KA (2017). Parent-reported severity and health/educational services use among U.S. children with autism: Results from a national survey. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics: JDBP, 38(4), 260–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman KE, Lindly O, Reyes N, Chavez AE, Macias K Smith KN, et al. (2017). Disparities in diagnosis and treatmen of autism in Latino and non-Latino white families. Pediatrics, 139(5), 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman KE, Lindly OJ, Bethell CD, & Kuhlthau K (2014a). Family impacts among children with autism spectrum disorder: the role of health care quality. Academic Pediatrics, 14(4), 398–407, doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman KE, Sinche B, Mejia A, Cobian M, Becker T, & Nicolaidis C (2014b). Latino parents’ perspectives on barriers to autism diagnosis. Academic Pediatrics, 14(3), 301–308, doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2013.12.004 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.