Abstract

Using a longitudinal, cross-lagged design, this study examined the bidirectional relations between mothers’ and fathers’ sensitivity and children’s externalizing (EXT) and internalizing (INT) behavior from middle childhood into adolescence. The subsample comprised families (N=578) in which the mother and father cohabitated from the study’s first time point (child age 54 months) through age 15 in the longitudinal NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development. Study results revealed differential patterns for mother-child and father-child relations in the full sample and separately for males and females. The full cross-lagged models revealed that child EXT behavior predicted maternal sensitivity but not vice-versa, and. father’s sensitivity and child behavior were reciprocally interrelated. There was a significant indirect pathway from early paternal sensitivity to later EXT in males and from early maternal sensitivity to INT in females. The results point to the important roles fathers play in child INT and EXT behaviors and important differences between males and females.

Keywords: fathering, mothering, internalizing behavior, externalizing behavior, cross-lagged design, longitudinal models

Common forms of child psychopathology are frequently divided into two broad categories: internalizing (INT) and externalizing (EXT) symptomatology (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1978). INT symptomatology includes mood and anxiety disorders and is characterized by negative emotionality (Achenbach, Howell, Quay, Conners, 1991; Bornstein, Hahn, Haynes, 2010). Children and adolescents with high levels of INT symptoms are characterized by anxious, shy, withdrawn and depressed behavior and are at risk for a range of psychosocial difficulties, including impaired personal relationships and poor school performance. The rates for INT symptoms among young children in the US range from 5 to 15% for children (Egger & Angold, 2006) and 5 to 22% for adolescents (Merikangas, He, Burstein, Swanson, Avenevoli, Cui, & Swendsen, 2010). Much of the research on INT symptoms focused on early adolescence and emerging adulthood (Angold Erkanli, Silberg, Eaves, & Costello, 2002). More recently, studies with both epidemiological and community samples have suggested that INT symptomatology is moderately stable across childhood but increases steadily during adolescence (Kessler, Petukhova, Sampson, Zaslavsky, & Wittchen, 2015; Bongers, Koot, van der Ende, & Verhulst, 2003). There is additional evidence to suggest that INT varies by sex, with girls showing higher mean increases in INT symptoms from childhood onward when compared to boys (Angold et al., 2002).

EXT symptomatology includes disruptive behavior that is characterized by disinhibition (Iacono, Malone, & McGue, 2008), and is linked to academic problems, peer rejection, delinquency, and substance abuse (Campbell, 2002). Although young children occasionally display minor physical aggression (e.g., pushing, hitting), defiance (e.g., saying “no,” refusing to follow parental directions), and temper tantrums, these behaviors decline in frequency as children mature and develop better emotional and behavioral regulation skills that are tied to increases in problem-solving abilities and appropriate coping skills (see Campbell, 1995, for a review). In contrast, as children get older, no decline in these behaviors or an increase in problematic behaviors may become crystallized patterns of antisocial behavior by late childhood and early adolescence, which may begin a trajectory of escalating academic problems, substance abuse, delinquency, and violence (Loeber & Farrington, 2000).

Research examining the developmental course of EXT behavior has yielded mixed results. Early work using longitudinal data found significant stability of EXT symptoms across developmental periods that persisted into adolescence (Campbell, 2002). In contrast, in a large-scale study examining normative developmental trajectories of EXT behavior, Bongers and colleagues (2003) found a decline in mother-reported EXT behaviors for both boys and girls between ages 4 and 18 in a representative sample of over 2,000 Dutch children. However, despite evidence of sex differences in INT and EXT problems (e.g., Angold et al., 2002), the majority of studies focusing on parenting and behavioral problems did not differentiate between boys and girls (see review by Hoeve, Dubas, Eichelsheim, Van Der Laan, Smeenk, & Gerris, 2009), and research would benefit from longitudinal data designed to specifically examine child sex in the associations between child behavior and parenting over time.

Although the aforementioned evidence suggests that INT and EXT psychopathology are distinctive, there is also evidence of high co-occurrence between these symptomologies (Fanti & Henrich, 2010). On the surface, the association between INT and EXT symptoms is unexpected given the dissimilarities in symptoms characterizing each. However, recent findings suggest that comorbidity of INT and EXT may have greater detrimental consequences than either disorder alone (Keiley, Lofthouse, Bates, Dodge, & Pettit, 2003), with additional findings suggesting a reciprocal nature between the two pathologies (Klostermann, Connell, & Stormshak, 2014) such that INT and EXT symptoms appear to reinforce one another across development ( Measelle, Stice, & Hogansen, 2006).

Family systems theory emphasizes the importance of considering the dynamic interplay between the multiple relationships in the family to better understand child development. According to family systems theory, each family relationship (e.g., mother-child) is embedded in a network of other family relationships (e.g., mother-father), and a better understanding of the functioning of any given system in the family can be gained by considering the interdependence of these relationships and their mutual influence (Cox & Paley, 2003). From this perspective, individuals affect one another through their own personal resources and stresses (risk factors) and through the quality of their relationships.

The ways in which parents interact with their children has been linked to child adjustment in multiple domains of functioning as well as in the development and maintenance of psychopathology (Cassidy, 2008). Reviews of the childrearing literature have identified the parent’s ability to provide emotional nurturance and warmth, referred to as parent sensitivity, as a key mediating process linking parenting behavior to child adjustment (**blinded**; Cox & Harter, 2003; Grolnick, Gurland, DeCourcey, & Jacob, 2002). Parenting sensitivity is the ability to recognize and respond both effectively and promptly to the distress and needs of one’s child (Cox & Harter, 2003), and has been linked to behavioral outcomes during childhood and adolescence (Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, & Juffer, 2003; Teti & Candelaria, 2002).

Numerous studies document an association between parenting behavior and INT and EXT symptoms in children and adolescents. Findings from these studies suggest that warm responsive parenting is inversely related to INT symptoms (Elgar, Mills, McGrath, Waschbusch, & Brownridge, 2007; Bean, Barber, & Crane, 2006) and EXT symptoms (Miner and Clarke-Stewart, 2008; and Hoeve, et al., s, 2009). For example, Bayer, Sanson, & Hemphill (2010) reported that the children of parents that scored low on parental warmth showed higher levels of INT symptoms over time. Similarly, studies examining parenting behavior as a potential contributor to EXT problems in offspring have typically identified parenting behavior characterized as nonresponsive or low in warmth as a predictor of subsequent EXT problems across development in both males and females (Hoeve, Dubas, Eichelsheim, Van Der Laan, Smeenk, & Gerris, 2009). These reports provide evidence that sensitivity promotes emotion regulation, thus allowing children to face stressors with a greater sense of efficacy and safety and supporting the development of coping strategies (Gilissen, Koolstra, Van IJzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Van der Veer, 2007). The scaffolding nature of sensitivity is likely to provide children with opportunities to learn behavioral and emotional self-regulation strategies for dealing with social conflicts in constructive ways (Graziano, Keane, & Calkins, 2010).

Whereas most research on parent sensitivity and INT and EXT behaviors focused on the mother’s parenting behaviors (Cabrera, Tamis-LeMonda, Bradley, Hofferth, & Lamb, 2000; TamisLeMonda & Cabrera, 2002), research involving both parents indicates that father’s caregiving may have a unique influence on children independent of mother’s caregiving. Wang & Kenny (2014) reported that fathers’ discipline at age 13 predicted an increase in adolescent conduct problems and depressive symptoms between ages 13 and 14, independent of mother’s discipline. Lansford, Laird, Pettit, Bates, & Dodge (2014) reported that fathers’ parenting, but not mothers’ parenting, was a unique predictor of adolescents’ INT and EXT problems.

Contemporary theories of parenting and family processes increasingly conceptualize children as taking an active role in shaping parents’ behavior (Kuczynski, Pitman, & Mitchell, 2009). This perspective is supported by a number of studies positing that parenting behavior in the parent-child relationship may in part be a response to children’s behavior (e.g., Kerr & Stattin, 2003; Huh, Tristan, Wade, & Stice, 2006; Burke, Pardini, & Loeber, 2008; Wang, Christ, Mills-Koonce, Garrett-Peters, & Cox, 2013). Although a parent may be the dominant force in shaping children’s behavior in early childhood, a bidirectional relationship would suggest that as children’s social and cognitive capacities increase, they play a stronger role in their own development (Bell 1968; Cox et al., 2010; Sroufe et al., 2005). According to such models, not only would the sensitivity be related to child INT and EXT symptoms, child problem behaviors may in turn elicit less sensitivity. Indeed, several recent studies provide support for this view. Burke et al., (2008) reported that there was greater influence of child behaviors on parenting behaviors than vice versa from childhood to late adolescence. Huh et al. (2006) found that problem behavior was a more consistent predictor of parenting than parenting was of problem behavior. Given that the bidirectional influences in parent-child relationships are best understood in the context of intimate, long-term relationships (Kuczynski and Parkin, 2006), the scarcity of longitudinal research on the independent effects of maternal and paternal sensitivity across childhood and early adolescence diminishes our ability to identify adjustment risk factors.

Moreover, although bidirectional parent and child influences have been incorporated into theoretical models pertaining to the development of INT and EXT behaviors, few studies have examined these effects across childhood and early adolescence (Pardini, 2008). Further, the reciprocal nature of father-child relationships across childhood have not been well-examined, leaving several important research questions unanswered as to the nature of bidirectional parent-child relations across development and how mothers’ and fathers’ parenting behaviors may be differentially related to adolescent psychopathology.

Importantly, mothers’ and fathers’ parenting behaviors may also have differential influence across developmental stages. In a meta-analytic study of maternal and paternal psychopathology and children’s problem behavior, when predicting INT problems, Connell and Goodman (2002) found that effect sizes for maternal factors were significantly higher (p < .05) than those for paternal factors during early and middle childhood (r = .19 for mothers and r = .09 for fathers during early childhood; and r = .17 for mothers and r = .13 for fathers during middle childhood). However, the reverse was true for adolescent INT problems (r = .13 for mothers, r = .23 for fathers). These findings provide evidence that paternal behavior may become more salient for children later in development (Goodman, 2002). This possibility has been largely unexplored in the context of child behavior. The present study addresses this limitation in the literature by examining the bidirectional relations between mothers’ and fathers’ sensitivity and child INT and EXT behavior across middle childhood and early adolescence.

The Current Study

In the present study, we examined reciprocal relations between sensitivity and INT and EXT behavior problems across childhood and adolescence. We included observational assessments of both mother’s and father’s sensitivity behavior in order to determine the differential effects of maternal and paternal sensitivity across time. Using the same measures from grade 1 (G1) through age 15, we modeled the cross-lagged effect between maternal and paternal sensitivity and INT and EXT behaviors so that bidirectional associations between maternal and paternal sensitivity and EXT and INT behaviors were estimated simultaneously. In so doing, we were able to test for maternal, paternal, and child effects starting from middle childhood to early adolescence. By simultaneously examining both parents in the same analysis (e.g., Bean, Barber, & Crane, 2006), we extended previous research to determine whether mothering and fathering are unique predictors of behavior problems. Including multiple family members in research is consistent with a family system approach emphasizing that behaviors of family members occur in a broader family context and are influenced, in part, by the behaviors of other members of the family system.

Given that most research examining maternal and paternal caregiving and child behavior problems has been conducted with infants and toddlers (Macoby & Martin, 1983; Wang et al., 2013), the current study addresses a gap in the literature by examining the relations between parenting and child behavior in middle childhood through the transition to adolescence. Using a large sample of children who coresided with both biological parents (n=578) from age six to fifteen, we examined the bidirectional nature of parent and child behavior from G1 through the transition to adolescence. We began our analysis at G1 as children are transitioning to formal schooling, as they must navigate new relationships with teachers and peers and adjust to the demands of classroom routines (Pianta et al., 2007), through the transition to adolescence. Both transitions may be stressful for children and make them more vulnerable to behavior problems. The transition to adolescence is especially a time of vulnerability for antisocial behavior (Bornstein et al., 2010). Therefore, understanding family factors that may be related to adolescent behavior problems will help to identify entry points for intervention.

Based on extant literature linking individual- and family-level factors to child INT and EXT behaviors (Cassidy, 2008), we hypothesized that (1) there would be significant cross-lagged effects indicating reciprocal feedback between maternal and paternal sensitivity and child behavior across childhood and early adolescence, that (2) given previous reports (e.g., Wang et al., 2013; Burke et al., 2008) suggesting that across time, child behavior has a greater effect on mother’s parenting than the reverse, we posited that children’s behavior problems would have a stronger influence on mothers’ sensitivity than the reverse, and that (3) there would be a unique reciprocal effect between father’s sensitivity and children’s behavior problems above and beyond the effects of maternal sensitivity.

Method

Sample

Data for this study came from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (SECCYD). Briefly, the NICHD SECCYD began in 1991 with enrollment at 10 sites across the United States of 1,364 families at the birth of their healthy, full-term infant. Participants were selected to ensure socioeconomic and ethnic diversity and based on the mother’s work intentions. Exclusion criteria included mothers < 18 years old, the mother’s inability to communicate in English, the family’s intention to move outside of the study area within 3 years, or the newborn having obvious disability or requiring a hospital stay of more than 1 week. Children and their families enrolled in the SECCYD have been followed from birth into adolescence through regular assessments that included direct observations and personal interviews with parents, children, caregivers, and teachers using procedures standardized across sites. The subsample for the present analysis included a subset of families (N=578) in which the mother and father cohabitated from the study’s first time point through at least the age 15- time point. As this paper reports a secondary data analysis using de-identified data, the Institutional Review Board (IRB) determined that this study was exempt from IRB review.

Measures

EXT and INT behavior.

At G1, grade 3 (G3), and grade 5 (G5) and age 15, mothers completed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991, 1992). The CBCL assess problem behaviors and social skills in children 4–18 years old (Achenbach, 1991a), and has been standardized and validated in large samples of children in the United States and abroad. Behaviors are rated on 3-point scales from 0 (not true of the child) to 2 (very true of the child). Cronbach’s alphas for our subsample for G1, G3, G5, and age 15 were 0.71, 0.73, 0.73, and 0.76 for INT behavior and 0.77, 0.77, 0.76, 0.82 for EXT behavior, respectively.

Parent sensitivity.

Parent sensitivity was determined using observational assessments in separate mother-child and father-child interactions at G1, G3, G5, and age 15. These interactions were recorded for later coding by groups of trained coders. Briefly, at the G1 visit, the tasks included cooperatively drawing a picture on an Etch-A-Sketch with each person controlling one of the knobs (mother-child and father-child pairs were assigned different pictures), using different shaped parquet pattern blocks to fill in three geometric cutout frames, and playing a card game that is competitive but developmentally appropriate for a 7-year-old. For the G3 visit, parents and children were engaged in a rules discussion task with three types of topics (i.e., kid rules, parent rules, and difficult decisions) printed on colored cards for selection and an errand planning task in which both parties work together to determine the optimal route for the completion of 11 errands using a town map (e.g., take laundry to Laundromat). For the 5th grade parent-child interactions, parents and children were asked to participate in a discussion task in which the dyad was presented a set of 22 cards each labeled with a topic of potential parent-child disagreement (e.g., after-school activities). Mother-child and father-child dyads were asked to mutually decide on three cards representing disagreements that they had and spend 7 minutes discussing all three of these issues in an attempt to make progress towards a resolution. The 15-year parent-adolescent interaction task was designed to assess the qualities of parent-adolescent interaction during an 8 minute (minimum of 5 minutes) discussion of one or more (typically two) areas of disagreement between the adolescent and the parent (e.g., chores, homework, use of free time) selected by the adolescent (Allen, Hall, Insabella, Land, Marsh, & Porter, 2003).

The videotaped interactions from the 10 research sites were coded at a central location using 7-point rating scales. The coders were blind to all other information about the dyads. At the first three time points (G1- G5), maternal sensitivity behaviors were rated using four global rating scales: supportive presence, respect for autonomy, hostility, and stimulation of cognitive development. Factor analyses with an oblique rotation (i.e., promax) guided the creation of a sensitivity composite comprised of the mean of supportive presence, respect for autonomy, and hostility (reflected) to obtain overall sensitivity. At age 15, seven rating scales were used: queries for information seeking, validation/agreement, engagement, inhibiting relatedness (reflected), hostility/devaluing (reflected), respect for autonomy, and valuing/warmth. All seven scales were included in the sensitivity composite used in the present analyses. Higher scores on the sensitivity composite reflect parenting behaviors that are child-centered, engaged, warm, and stimulating. In contrast, lower scores on the sensitivity composite reflect parenting behaviors where the parent rarely responds appropriately to the child’s cues and does not manifest an awareness of the child’s needs. Inter-rater reliability was monitored throughout the coding period with intraclass correlations ranging from 0.82 to 0.87 for the maternal sensitivity composite and 0.79 – 0.83 for the paternal sensitivity composite.

Control variables.

The family’s income-to-needs ratio, maternal age, parental education, and race were included as covariates in the original model as they have been identified as important correlates of parenting (see Conger, Conger, & Martin, 2010, for a review). Maternal age and parental education did not add explanatory power to the model and therefore were removed for parsimony. The overall model results were not changed with their removal. The income-to-needs ratio is an estimate of total household income that is computed by dividing the household income by the federal poverty threshold adjusted for number of persons in the home. An income-to-need ratio of 1.00 or below indicates family income at or below the poverty level, adjusted for family size.

Further, child temperament was included as a control variable given previous reports that document an association with INT and EXT behavior and temperament (Leve, Kim, & Pears, 2006). When children were 54 months old, mothers completed a modified version of the Children’s Behavior Questionnaire (Rothbart, Ahadi, Hershey, and Fisher, 2001) that included 80 items and 8 scales: Activity Level, Anger/Frustration, Approach/Anticipation, Attentional Focusing, Fear, Inhibitory Control, Sadness, and Shyness (Cronbach’s α = 0.81). Ratings were made on a Likert-type scale, with scores ranging from 1 (extremely untrue) to 7 (extremely true). Inhibitory control was included in the present analyses due to its well-established link to socioemotional adjustment (Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Sessa, Avenevoli, & Essex, 2002).

Analysis Plan

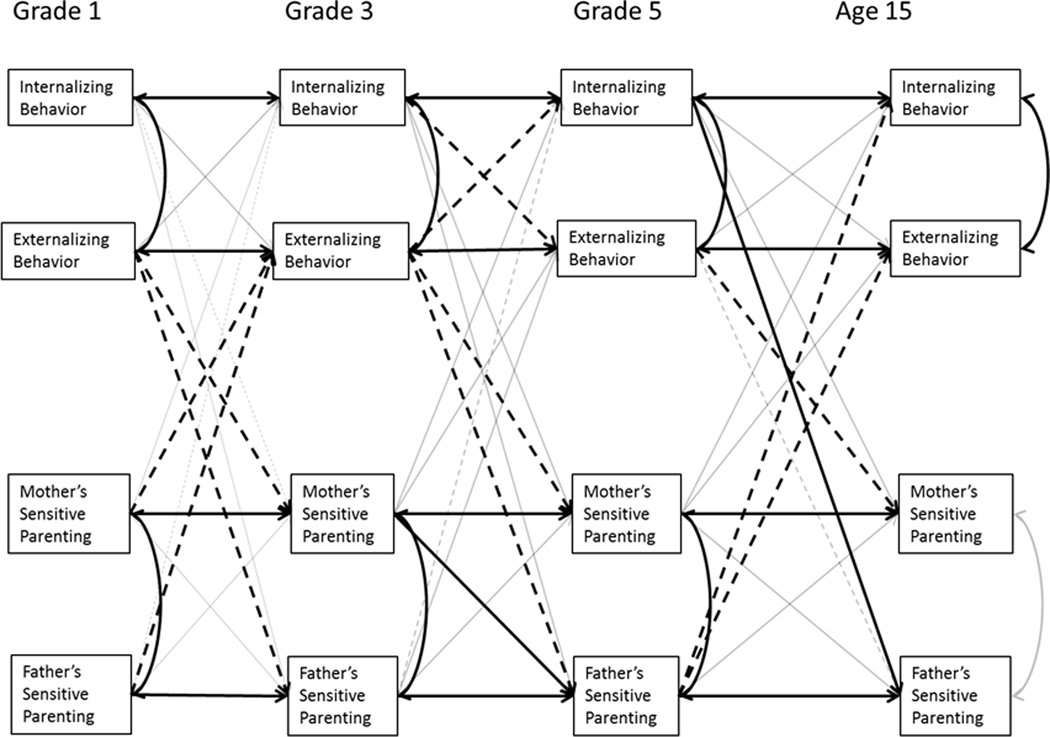

In the current study, we used a cross-lagged model to examine the direction of associations between maternal and paternal parenting and child INT and EXT behavior. The cross-lagged model is depicted in all figures with significant associations bolded and nonsignificant associations faded. Each time point was estimated by all behavior and parenting variables from the previous time point (e.g., G3 was predicted by G1 variables), and concurrent behavior and concurrent parenting were allowed to covary.

Model estimation was performed using MPlus version 7.11 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2011). Control variables were first chosen based on correlations and theoretical interest. Model fit was assessed using the Chi-Square statistic, the comparative fit index (CFI; Bentler, 1990), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI; Tucker & Lewis, 1973), the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA; Browne & Cudeck, 1993), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR, Hu & Bentler, 1999). CFI and TLI values above .90 and RMSEA and SMR below 0.05 are considered indicators of good fit. The Wald test of parameter constraints was used to compare the model divided by sex, and 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for all significant indirect pathways.

Results

Descriptive statistics and Pearson’s correlations are shown in Table 1. The children included were evenly divided between males (49.59%) and females (50.41%) and were primarily white, non-Hispanic (90.51%). The mean income-to-needs ratio at the 54-month visit was 17.63 (SD = 16.76, median = 14.42). The income-to-needs ratio was skewed with 70% of the sample having an income-to-needs ratio below 20. The average maternal education in our sample was 15 years (range = 8–21 years) with 30% having completed a college degree. The average paternal education was 15 years (range = 6–21 years) with 27.8% having a college degree. The mean age of the mothers was 30.16 years at the G1 time point (SD = 4.97, range = 18–46 years).

Table 1:

Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations (n=578)

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1. Maternal Sensitive Parenting | 17.49 | 2.58 | |||||||||||||||

| 2. Paternal Sensitive Parenting | 17.24 | 2.51 | 0.31*** | ||||||||||||||

| 3. INT Behavior | 4.63 | 4.24 | 0.01 | 0.04 | |||||||||||||

| 4. EXT Behavior | 7.18 | 5.77 | −0.08 | −0.05 | 0.54*** | ||||||||||||

| Grade 3 | |||||||||||||||||

| 5. Mother’s Sensitive Parenting | 16.33 | 3.59 | 0.27*** | 0.15** | −0.07 | −0.13** | |||||||||||

| 6. Father’s Sensitive Parenting | 16.95 | 3.48 | 0.17** | 0.27*** | 0.04 | −0.07 | 0.28*** | ||||||||||

| 7. INT Behavior | 4.19 | 4.35 | −0.05 | −0.02 | 0.67*** | 0.42*** | −0.08 | 0.03 | |||||||||

| 8. EXT Behavior | 8.13 | 6.13 | −0.12* | −0.12* | 0.49*** | 0.74*** | −0.18*** | −0.08 | 0.61*** | ||||||||

| Grade 5 | |||||||||||||||||

| 9. Mother’s Sensitive Parenting | 17.92 | 6.34 | 0.09* | 0.11* | −0.01 | −0.1* | 0.18*** | 0.09* | −0.02 | −0.11* | |||||||

| 10. Father’s Sensitive Parenting | 19.34 | 4.18 | 0.14** | 0.21*** | −0.07 | −0.11* | 0.18*** | 0.19*** | −0.002 | −0.09* | 0.15** | ||||||

| 11.INT Behavior | 4.93 | 4.89 | −0.002 | 0.01 | 0.65*** | 0.41*** | −0.04 | −0.01 | 0.55*** | 0.43*** | −0.03 | −0.08 | |||||

| 12.EXT Behavior | 5.56 | 5.42 | −0.11* | −0.11* | 0.4*** | 0.66*** | −0.1* | −0.05 | 0.37*** | 0.63*** | −0.08* | −0.12* | 0.58*** | ||||

| Age 15 | |||||||||||||||||

| 13. Mother’s Sensitive Parenting | 28.39 | 6.08 | 0.13** | 0.09 | −0.03 | −0.09* | 0.07 | 0.07 | −0.02 | −0.06 | 0.16** | 0.09* | −0.01 | −0.09* | |||

| 14. Father’s Sensitive Parenting | 29.41 | 4.66 | 0.16** | 0.21*** | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.1* | 0.17** | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.09 | 0.16** | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.1* | ||

| 15.INT Behavior | 4.91 | 5.25 | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.48*** | 0.34*** | −0.14** | −0.12* | 0.43*** | 0.38*** | 0.06 | −0.11* | 0.62*** | 0.43*** | −0.04 | 0.02 | |

| 16.EXT Behavior | 4.5 | 5.86 | −0.13** | −0.12* | 0.27*** | 0.49*** | −0.14** | −0.18*** | 0.23*** | 0.45*** | −0.09* | −0.14** | 0.35*** | 0.56*** | −0.12* | −0.04 | 0.63*** |

Note:

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001;

INT: Internalizing, EXT: Externalizing.

Full Model

The results of the full model are shown in Figure 1. The model fit was good, χ2 (107) = 203.41, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.04, SMR = 0.04. The results demonstrated that there were reciprocal relations between parenting and child behavior across time from G1 to age 15. There was high stability of behavior and parenting across time (e.g., G1 INT behavior predicted G3 INT behavior). G3 INT behavior predicted G5 EXT behavior (β = −0.2, p < 0.001), and G3 EXT behavior predicted G5 INT behavior (β = −0.2, p < 0.01), but otherwise INT and EXT behaviors did not predict each other across time. Maternal sensitivity at G3 predicted paternal sensitivity at G5 (β = 0.14, p < 0.01), but otherwise maternal and paternal sensitivity did not predict each other across time. Concurrent behavior significantly covaried from G1 to age 15, and concurrent parenting significantly covaried from G1 to G5. Table 2 shows the overall stability of behavior and parenting across time.

Figure 1.

Full model results. Significant associations are shown with bolded lines. Faded lines were modeled but not significant. Solid lines indicate positive associations, and dashed lines indicate negative associations. Standardized coefficients are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Stability of behavior and parenting from grade 1 to age 15.

| Full Model - Between Time Points | β for behavior Internalizing | Externalizing | β for parenting Maternal | Paternal |

| Grade 1 – Grade 3 | 0.78** | 0.95*** | 0.23*** | 0.24*** |

| Grade 3 – Grade 5 | 1.06*** | 0.98*** | 0.15** | 0.15** |

| Grade 5 – Age 15 | 0.57*** | 0.53*** | 0.15** | 0.16** |

| Full Model - Concurrent Effects | β for behavior | β for parenting | ||

| Grade 1 | 0.53*** | 0.3*** | ||

| Grade 3 | 0.34*** | 0.23*** | ||

| Grade 5 | 0.24*** | 0.1* | ||

| Age 15 | 0.58*** | 0.09 | ||

| Males – Between Time Points | β for behavior Internalizing | Externalizing | β for parenting Maternal | Paternal |

| Grade 1 – Grade 3 | −1.54 | 1.25*** | 0.22*** | 0.26*** |

| Grade 3 – Grade 5 | 1.08*** | 0.92*** | 0.24*** | 0.16* |

| Grade 5 – Age 15 | 0.68*** | 0.5*** | 0.11 | 0.18* |

| Males – Concurrent Effects | β for behavior | β for parenting | ||

| Grade 1 | 0.49*** | 0.29*** | ||

| Grade 3 | 0.39** | 0.04 | ||

| Grade 5 | 0.2*** | 0.06 | ||

| Age 15 | 0.48*** | 0.13 | ||

| Females – Between Time Points | β for behavior Internalizing | Externalizing | β for parenting Maternal | Paternal |

| Grade 1 – Grade 3 | 1.57 | 0.69*** | 0.24*** | 0.22** |

| Grade 3 – Grade 5 | 0.93*** | 1.08*** | 0.08 | 0.18* |

| Grade 5 – Age 15 | 0.46*** | 0.55*** | 0.21** | 0.16* |

| Females – Concurrent Effects | β for behavior | β for parenting | ||

| Grade 1 | 0.57*** | 0.31*** | ||

| Grade 3 | 0.31 | 0.41*** | ||

| Grade 5 | 0.28** | 0.13* | ||

| Age 15 | 0.65*** | 0.03 | ||

Note:

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001

With regards to mothers, the cross effects of parenting predicting child behavior were not consistent across time. As hypothesized, child behavior more consistently affected maternal sensitivity than maternal sensitivity affected child behavior (Table 3). Only maternal sensitivity at G1 predicted EXT behavior at G3 (β = −0.06, p < 0.05). However, previous EXT behavior consistently predicted later maternal sensitivity from G1 through age 15 (EXT behavior at G1 → mother’s sensitivity at G3 (β = −0.1, p < 0.05); EXT behavior at G3 → mother’s sensitivity at G5 (β = −0.13, p < 0.05); EXT behavior at G5 → mother’s sensitivity at age 15 (β = −0.12, p < 0.05)).

Table 3.

Cross effects among parental sensitivity and child behavior.

| Full Model | |||||

| Cross Effects Internalizing Behavior | β for Maternal Sensitive Parenting | β for Paternal Sensitive Parenting | Cross Effects Maternal Sensitive Parenting | β for Internalizing Behavior | β for Externalizing Behavior |

| Grade 1 – Grade 3 | −0.03 | −0.02 | Grade 1 – Grade 3 | −0.02 | −0.1* |

| Grade 3 – Grade 5 | 0.05 | −0.04 | Grade 3 – Grade 5 | 0.05 | −0.13* |

| Grade 5 – Age 15 | −0.2 | −0.09* | Grade 5 – Age 15 | 0.07 | −0.11* |

| Externalizing Behavior | Paternal Sensitive Parenting | ||||

| Grade 1 – Grade 3 | −0.06* | −0.07* | Grade 1 – Grade 3 | 0.07 | −0.11* |

| Grade 3 – Grade 5 | 0.04 | 0.02 | Grade 3 – Grade 5 | 0.08 | −0.12* |

| Grade 5 – Age 15 | −0.03 | −0.1* | Grade 5 – Age 15 | 0.13* | −0.1 |

| Males | |||||

| Cross Effects Internalizing Behavior | β for Maternal Sensitive Parenting | β for Paternal Sensitive Parenting | Cross Effects Maternal Sensitive Parenting | β for Internalizing Behavior | β for Externalizing Behavior |

| Grade 1 – Grade 3 | −0.06 | −0.01 | Grade 1 – Grade 3 | −0.09 | −0.04 |

| Grade 3 – Grade 5 | −0.05 | −0.04 | Grade 3 – Grade 5 | 0.05 | −0.07 |

| Grade 5 – Age 15 | 0.002 | −0.14** | Grade 5 – Age 15 | 0.03 | −0.13 |

| Externalizing Behavior | Paternal Sensitive Parenting | ||||

| Grade 1 – Grade 3 | −0.08 | −0.12** | Grade 1 – Grade 3 | 0.03 | −0.08 |

| Grade 3 – Grade 5 | −0.02 | 0.06 | Grade 3 – Grade 5 | 0.03 | −0.14 |

| Grade 5 – Age 15 | 0.04 | −0.14* | Grade 5 – Age 15 | 0.13 | −0.06 |

| Females | |||||

| Cross Effects Internalizing Behavior | β for Maternal Sensitive Parenting | β for Paternal Sensitive Parenting | Cross Effects Maternal Sensitive Parenting | β for Internalizing Behavior | β for Externalizing Behavior |

| Grade 1 – Grade 3 | −0.003 | −0.01 | Grade 1 – Grade 3 | 0.04 | −0.16* |

| Grade 3 – Grade 5 | 0.17** | −0.07 | Grade 3 – Grade 5 | 0.07 | −0.19* |

| Grade 5 – Age 15 | −0.03 | −0.05 | Grade 5 – Age 15 | 0.08 | −0.05 |

| Externalizing Behavior | Paternal Sensitive Parenting | ||||

| Grade 1 – Grade 3 | −0.04 | −0.01 | Grade 1 – Grade 3 | 0.1 | −0.13 |

| Grade 3 – Grade 5 | 0.1* | −0.06 | Grade 3 – Grade 5 | 0.13 | −0.13 |

| Grade 5 – Age 15 | −0.07 | −0.08 | Grade 5 – Age 15 | 0.14 | −0.14 |

Note:

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01.

The pattern of effects differed for fathers such that reciprocal effects were greater at the youngest and oldest ages (Table 3), and father’s sensitivity had more effect on behavior than mother’s sensitivity. We found a reciprocal pathway from early paternal sensitivity through later child behavior. Paternal sensitivity at G1 predicted EXT behavior at G3 (β = −0.07, p < 0.05), EXT behavior at G3 predicted father’s sensitivity at G5 (β = −0.12, p < 0.05), and finally father’s sensitivity at G5 predicted both INT (β = −0.09, p < 0.05) and EXT behavior at age 15 (β = −0.1, p < 0.05). The indirect pathway from G1 paternal sensitivity through age 15 EXT behavior was significant (−0.07, p < 0.05, 95% CI: −0.065, −0.011), with greater paternal sensitivity predicting reduced EXT behaviors, highlighting the importance of early father-child relationships.

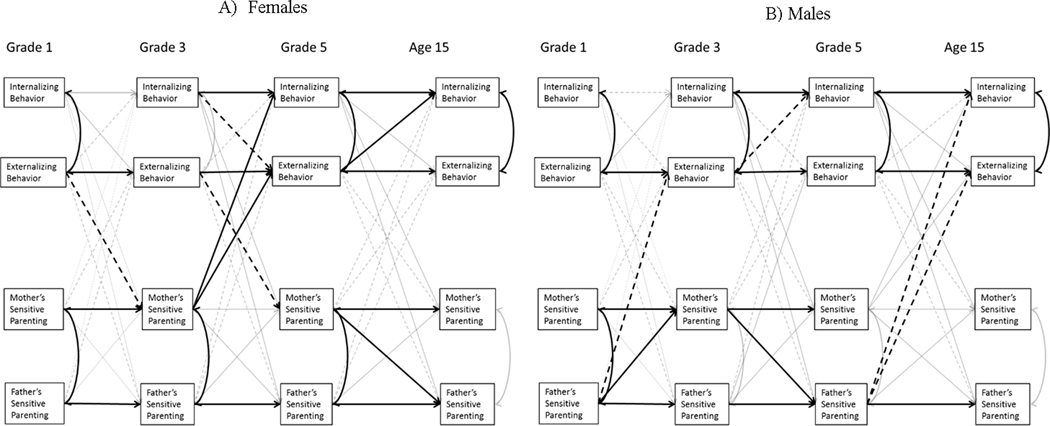

Model by Sex

Due to the well-documented differences in the prevalence of INT and EXT among males and females, and the fact that sex directly predicted paternal sensitivity, maternal sensitivity, and INT behavior at G1 in the present study, the model was also run after grouping by sex and constraining the paths across males and females to examine possible sex differences. The Wald test of parameter constraints was significant, indicating that the models for males and females were significantly different, χ2 (29) = 76.04, p < 0.05). The patterns of significant effects for males and females can be seen in Figure 2, and the coefficients for modeled effects can be seen in Tables 2 (stability across time) and 3 (cross effects). First, the overall model by sex fit the data moderately well, χ2 (188) = 309.31, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.05, SMR = 0.04, with females contributing more to the χ2 (193.32) than males. The model for females, like the full model, was largely stable across time with previous behavior predicting later behavior, and previous parenting predicting later parenting. INT and EXT behavior changed in the direction of the effect across time for females. Greater EXT behavior predicted reduced INT behavior from G3 to G5, but greater EXT behavior predicted greater INT behavior from G5 to age 15 (same pattern for INT behavior predicting EXT behavior). Females also had largely stable concurrent effects with INT and EXT behavior significantly, positively covarying at all time points except G3 (β = 0.31, p > 0.05), and maternal and paternal sensitivity significantly, positively covarying at all time points except Age 15 (β = 0.03, p > 0.05). The model with males was also largely stable across time for both parenting and behavior, but there were few significant concurrent effects between maternal and paternal sensitivity (only G1, β = 0.29, p < 0.05). INT and EXT behavior significantly, positively covaried at all time points for males, but early behavior rarely predicted later behavior.

Figure 2.

Results for models by sex. A) Model with only females. B) Model with only males. Bolded lines are significant associations. Faded lines were modeled but not significant. Solid lines indicate positive associations, and dashed lines indicate negative associations. Standardized coefficients are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

There were few reciprocal relations across time for males. Greater paternal sensitivity at G1 predicted reduced EXT behavior at G3 (β = −0.12, p < 0.05), and greater paternal sensitivity predicted reduced EXT and INT behaviors at age 15 (EXT: β = −0.14, p < 0.05; INT: β = −0.14, p < 0.05). However, child behavior did not predict parenting at any time point. There was a significant indirect pathway from G1 paternal sensitivity through G3, G5, and age 15 EXT behavior (−0.035, p < 0.05, 95% CI: −0.18, −0.05), with greater paternal sensitivity predicting reduced EXT behavior, indicating the importance of early father’s parenting on later child behavior in males.

There were few significant reciprocal relations across time for females. Maternal sensitivity and EXT behavior exhibited a reciprocal relation through G5, with greater G1 EXT behavior predicting reduced maternal sensitivity at G3 (β = −0.16, p < 0.05), and reduced maternal sensitivity at G3 predicting reduced INT and EXT behaviors at G5 (INT: β = 0.17, p < 0.05; EXT: β = 0.1, p < 0.05). Additionally, greater EXT behaviors at G3 predicted reduced maternal sensitivity at G5 (β = −0.19, p < 0.05). There was a significant indirect pathway from G1 and G3 mother’s sensitivity through G5 and age 15 INT behaviors (0.018, p < 0.05, 95% CI: 0.01, 0.06), with greater maternal sensitivity predicting greater INT behaviors,

Discussion

A central theme of research on child and adolescent psychopathology is the influence of the parent-child relationship on the child’s behavioral development. Though studies of the impact of parents on children are essential, a growing body of work emphasizes the importance of examining the influence of the child’s behavior problems on the parent-child relationship. In the current study, we sought to investigate the reciprocal relations between maternal and paternal sensitivity and INT and EXT behavior across childhood and adolescence. The strengths of this study include the longitudinal design, examining both maternal and paternal effects, and the use of observational assessments of parent-child relationships. Parenting observations offer the advantage of recording overt behavior, which may be less open to differing interpretations than are items on a self-report (Gardner, 2000).

The results from the full model and models by sex indicate the importance of considering father’s parenting and including reciprocal interactions between parenting and behavior. The overall results support all three hypotheses, but the models by sex indicate distinct differences between males and females. We found evidence of (1) significant cross-lagged effects between maternal and paternal sensitivity and child behavior across childhood and early adolescence in the full model, but limited cross-lagged effects in the models by sex, and that, (2) children’s behavior problems more consistently predicted mothers’ sensitivity than mother’s sensitivity predicted children’s behavior problems in all models, although the model with males found no significant role of maternal sensitivity above and beyond child behavior and father’s sensitivity. Finally, we found evidence of (3) unique reciprocal effects between father’s sensitivity and children’s behavior problems above and beyond the effects of maternal sensitivity, and that father’s sensitivity may play an especially important role for males. The indirect pathways indicated consistent effects starting with early parenting through later child behavior. In this study, we demonstrated that reciprocal relations between children and parents are important predictors of child psychopathology and may operate in an additive fashion. There is some indication that the parents’ and children’s responses build across time. Less paternal sensitivity at G1 predicted more EXT behavior at G3, more EXT at G3 predicted less paternal sensitivity at G5, and less paternal sensitivity at G5 predicted greater EXT and INT behavior at age 15.

We further found that the cross effects of parenting on child behavior were not consistent across time. However, child behavior consistently predicted parenting across time in the full model and the models by sex. This finding is in keeping with previous reports documenting that child behavior had a greater effect on parenting than the reverse (e.g., Wang et al., 2013; Kerr & Stattin, 2003). For example, in a study using the same data, the EXT behavior of 4-year-olds was predictive of reduced maternal sensitivity at 7 years of age (Wang et al., 2013). Burke et al., (2008) reported child-only effects in the association between oppositional defiant disorder and parental communication and involvement and between conduct disorder and parental control among boys age 7 to 17. Furthermore, Huh et al. (2006) reported a child-only effect in the transaction between adolescent girls’ EXT behavior and perceived maternal support and control.

Consistent with other reports of child effects on maternal caregiving, we noted child-driven effects on mothers’ sensitivity, particularly for EXT behaviors, but not the reverse (Burke et al., 2008; Huh et al., 2006). These findings suggest that as children grow and their social and cognitive capacities increase, they may play a stronger role in their own development (Bell 1968; Cox et al., 2010; Sroufe et al., 2005). These growing abilities are likely to equip children to more actively influence their own environments and may be reflected in their behavior having a greater effect on the behavior of their parents over time. Given that interventions aimed at decreasing INT and EXT problems in youth typically focus on parenting behavior (burke et al., 2008), the findings from this study would suggest that programs that include parents and children may be more fruitful.

Additionally, the present study found distinct differences between males and females that highlight important avenues for future research. First, father’s early sensitivity was particularly important for later child behavior in males, and mother’s early sensitivity was particularly important for behavior in females. These results may reflect increased socialization with the same sex parent across development (Hoeve, 2009; Shearer, Crouter, & McHale, 2005). In females, mother’s and father’s sensitivity covaried significantly from G1 through G5. In males, mother’s and father’s sensitivity only covaried significantly at G1. It is unclear if mother’s and father’s parent girls more similarly than they parent boys, or if one parent is taking cues from the other with regards to girls (i.e., fathers follow the mother’s lead in parenting girls). In contrast, fathers may feel more autonomous parenting boys, and subsequently have unique effects on boy’s development. Prior research suggests that mothers’ and fathers’ parenting may become more differentiated and complex over time (Sroufe & Jacobvitz, 1989), but this issue has not been well studied. Degnan, Almas, and Fox (2010) noted that for some children, maternal sensitivity may unintentionally serve to maintain or increase children’s internalizing behavior. Given developmental theories that posit that the primary tasks of adolescence include identity consolidation and increasing independence from parents, it may be that the transition from childhood to early adolescence represents a stress-challenge point for mothers and daughters. Although discordant with much of the literature on maternal sensitivity, girls seeking autonomy may find the highly responsive nature of sensitivity prevents them from exploration and novel experiences, consequently inhibiting the development of independent coping skills. Future research will need to examine if girls in the transition to adolescence perceive novel or complex experiences as beyond coping capacity in the context of sensitive caregiving. Furthermore, in keeping with previous research (Moffitt, Caspi, Rutter, Silva, 2001), the results from this study suggest a comorbid nature of INT and EXT over time for females, such that greater EXT behavior predicted greater INT behavior from grade 5 to age 15 (and vice versa). Future research investigating specific mechanisms that lead to sex differences in the developmental course of comorbid problems would be beneficial. The current study makes a unique contribution to the literature by extending earlier findings with the inclusion of fathers’ concurrent sensitivity. Finding a statistically significant indirect path from G1 paternal sensitivity through age 15 EXT behavior (−0.07, p < 0.05) highlights the importance of early father’s parenting to later child behavior problems above and beyond the effects of mother-child relationships, and contributes to current theories on the dynamic relations between the behaviors of multiple family members. The reciprocal nature of the father-child relationship between G5 and age 15 suggests that for fathers, children’s behavior over time may initiate feedback loops consisting of reciprocal negative influences of fathers and children upon one another, resulting in deteriorating parent-child relationships and increasing child INT and EXT in adolescence. This finding also implies that early childhood may provide an optimal opportunity for intervention by disrupting this cycle in the early elementary school years before it can escalate into a negative coercive cycle later in development (Patterson, 1982). These findings also highlight the importance of early parenting for males and females, although mothers and fathers may have distinct and separate effects on males and females that require further research.

Limitations

Despite the strengths of this study, limitations must be addressed. In the current study, parenting and child behavior were assessed at varying time points ranging from 2 (i.e., G1 and G3 assessments) to 5 years apart (G5 and age 15), which could be viewed as rather long periods given the significant developmental changes that occur during middle and late childhood and early adolescence. Given the dynamic nature of family relationships (Thelen & Smith, 1998, p. 56; Granic, Hollenstein, Dishion, & Patterson, 2003), it will be important in future research to examine even shorter windows of time to more fully explore the developmental progression of these reciprocal relations. Although we controlled for a wide array of child and family factors, we were only able to control for whether the child coresided with both biological parents from 54 months of age onward and not from infancy onward. Future research will need to address how patterns from infancy and early childhood may impact bidirectional models of mother-child and father-child relationships at later stages of development. It is important to emphasize that the associations we found are not necessarily causal despite the use of a cross-lagged path model that infers causality between exogenous variables predicting endogenous variables. In order to determine causality, we would need to be able to test all possible confounders, and we would need to manipulate performance on both constructs. Further, although the sample was diverse geographically, the study sample was not constructed to be nationally representative. The present analyses were conducted on a subset of two-parent households that were on average wealthy, additionally limiting generalizability to similar households. Despite these limitations, the current study makes a significant contribution to the understanding of reciprocal nature of proximal relationships underlying children’s adjustment across middle childhood and early adolescence.

References

- Achenbach TM, & Edelbrock CS (1978). The classification of child psychopathology: a review and analysis of empirical efforts. Psychological Bulletin, 85(6), 1275–1301. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.85.6.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. (1991a). Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL/4–18, YRS and TRF profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Howell CT, Quay HC, Conners CK. National survey of problems and competencies among four to sixteen-year-olds. (1991). Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 56(3):1–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.1991.tb01174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Hall FD, Insabella GM, Land DJ, Marsh PA, & Porter MR (2003). Supportive behavior task coding manual. Unpublished manuscript, University of Virginia, Charlottesville. [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Erkanli A, Silberg J, Eaves L, & Costello EJ (2002). Depression scale scores in 8–17‐year‐olds: effects of age and gender. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 43(8), 1052–1063. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van Ijzendoorn MH, & Juffer F. (2003). Less is more: meta-analyses of sensitivity and attachment interventions in early childhood. Psychological Bulletin, 129(2), 195–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer JK, Hastings PD, Sanson AV, Ukoumunne OC, & Rubin KH (2010). Predicting mid-childhood internalizing symptoms: A longitudinal community study. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 12(1), 5–17. doi: 10.1080/14623730.2010.9721802 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bean RA, Barber BK, & Crane DR (2006). Parental support, behavioral control, and psychological control among African American youth: The relationships to academic grades, delinquency, and depression. Journal of Family Issues, 27(10), 1335–1355. doi: 10.1177/0192513X06289649. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RQ (1968). A reinterpretation of the direction of effects in studies of socialization. Psychological Review, 75, 81–95. doi: 10.1037/h0025583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongers IL, Koot HM, Van der Ende J, & Verhulst FC (2003). The normative development of child and adolescent problem behavior. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112(2), 179–192. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.2.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Hahn CS, Haynes OM (2010). Social competence, externalizing, and internalizing behavioral adjustment from early childhood through early adolescence: Developmental cascades. Development and Psychopathology, 22, 717–735. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, & Cudeck R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit In Bollen KA, & Long JS (Eds.), Testing Structural Equation Models (pp. 136–162). Newbury Park, CA: Sage Focus Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Burke JD, Pardini DA, & Loeber R. (2008). Reciprocal relationships between parenting behavior and disruptive psychopathology from childhood through adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(5), 679–692.doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9219-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera N, Tamis‐LeMonda CS, Bradley RH, Hofferth S, & Lamb ME (2000). Fatherhood in the twenty‐first century. Child Development, 71(1), 127–136. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Spieker S, Burchinal M, Poe MD, & NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. (2006). Trajectories of aggression from toddlerhood to age 9 predict academic and social functioning through age 12. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 791–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J. (2008). The nature of the child’s ties In Cassidy J & Shaver P/R(Eds), Handbook of attachment, Second Edition (pp 3–22). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Connell AM, & Goodman SH (2002). The association between psychopathology in fathers versus mothers and children’s internalizing and externalizing behavior problems: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 5, 746–773. Doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.5.746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Harter KSM. (2003). Parent-child relationships In Bornstein MH, Davidson L, Keyes CLM, Moore KA (Eds.). Well-being: Positive development across the life course. (pp. 191–204). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Mills-Koonce R, Propper C, & Gariepy J. (2010). Systems theory and cascades in developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 22, 497–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Paley B. (1997). Families as systems. Annual Review of Psychology, 48,243–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel E, Madigan S, & Jenkins J. (2016). Paternal and maternal warmth and the development of prosociality among preschoolers. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(1), 114–124. doi: 10.1037/fam0000120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger HL, & Angold A. (2006). Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: presentation, nosology, and epidemiology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(3‐4), 313–337. Doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanti KA, & Henrich CC (2010). Trajectories of pure and co-occurring internalizing and externalizing problems from age 2 to age 12: Findings from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Study of Early Child Care. Developmental Psychology, 46(5), 1159–1175. Doi: 10.1037/a0020659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner F. (2000). Methodological issues in the direct observation of parent-child interaction: Do observational findings reflect the natural behavior of participants? Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 3(3), 185–198. Doi: 10.1023/A:1009503409699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilissen R, Koolstra CM, van IJzendoorn MH, Bakermans‐Kranenburg MJ, & van der Veer R. (2007). Physiological reactions of preschoolers to fear‐inducing film clips: effects of temperamental fearfulness and quality of the parent-child relationship. Developmental Psychobiology, 49(2), 187–195. Doi: 10.1002/dev.20188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziano PA, Calkins SD, & Keane SP (2010). Toddler self-regulation skills predict risk for pediatric obesity. International Journal of Obesity, 34(4), 633–641.doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grolnick WS, Gurland ST, DeCourcey W, & Jacob K. (2002). Antecedents and consequences of mothers’ autonomy support: an experimental investigation. Developmental Psychology, 38(1), 143–155. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.38.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeve M, Dubas JS, Eichelsheim VI, Van Der Laan PH, Smeenk W, & Gerris JR (2009). The relationship between parenting and delinquency: A meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(6), 749–775.doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9310-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huh D, Tristan J, Wade E, & Stice E. (2006). Does problem behavior elicit poor parenting? A prospective study of adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescent Research, 21(2), 185–204.doi: 10.1177/0743558405285462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Malone SM, McGue M. (2008). Behavioral disinhibition and the development of early-onset addiction: Common and specific influences. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 4, 325–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M, & Stattin H. (2003). Parenting of adolescents: Action or reaction? In Crouter AC & Booth A (Eds.). Children’s influence on family dynamics: The neglected side of family relationships (pp. 121–151). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Klostermann S, Connell A, & Stormshak EA (2016). Gender differences in the developmental links between conduct problems and depression across early adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 26(1), 76–89. Doi: 10.1111/jora.12170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Markon KE, Patrick CJ, Benning SD, & Kramer MD (2007). Linking antisocial behavior, substance use, and personality: an integrative quantitative model of the adult externalizing spectrum. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116(4), 645–666. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.4.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczynski L & Parkin M. (2006). Agency and bidirectionality in socialization: Interactions, transactions, and relational dialectics In Grusec JE and Hastings PD (Eds). Handbook of socialization: Theory and research. (pp. 259–283). New York, NY, US: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kuczynski L, Pitman R, & Mitchell M. (2009). Dialectics and transactional models: Conceptualizing antecedents, processes, and consequences of change in parent-child relationships In Mancini J & Roberto K (Eds.). Pathways of human development: Explorations of change. (pp. 151–170). Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Laird RD, Pettit GS, Bates JE, & Dodge KA (2014). Mothers’ and fathers’ autonomy-relevant parenting: Longitudinal links with adolescents’ externalizing and internalizing behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(11), 1877–1889. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0079-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Kim HK, & Pears KC (2005). Childhood temperament and family environment as predictors of internalizing and externalizing trajectories from ages 5 to 17. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33, 505–520.doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-6734-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, & Farrington DP (2000). Young children who commit crime: Epidemiology, developmental origins, risk factors, early interventions, and policy implications. Development and Psychopathology, 12(4), 737–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE, & Martin JA (1983). Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction In Mussen PH (Series Ed.) & Hetherington EM (Vol. Ed.). Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 4 Socialization, personality, and social development, 4th ed. (pp. 1–101). New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- McKee L, Roland E, Coffelt N, Olson AL, Forehand R, Massari C, ... & Zens MS (2007). Harsh discipline and child problem behaviors: The roles of positive parenting and gender. Journal of Family Violence, 22(4), 187–196. doi: 10.1007/s10896-007-9070-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Measelle JR, Stice E, & Hogansen JM (2006). Developmental trajectories of co-occurring depressive, eating, antisocial, and substance abuse problems in female adolescents. Journal of abnormal psychology, 115(3), 524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Nakamura EF, & Kessler RC (2009). Epidemiology of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 11(1), 7–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner JL, & Clarke-Stewart KA (2008). Trajectories of externalizing behavior from age 2 to age 9: relations with gender, temperament, ethnicity, parenting, and rater. Developmental Psychology, 44(3), 771–786. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Rutter M, & Silva PA (2001). Sex differences in antisocial behavior: conduct disorder, delinquency, and violence in the Dunedin longitudinal study. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Sessa FM, Avenevoli S, & Essex MJ (2002). Temperamental vulnerability and negative parenting as interacting predictors of child adjustment. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(2), 461–471.doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00461.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK & Muthén BO. (1998 - 2010). Mplus user’s guide, 6th edition Los Angeles, CA: [Google Scholar]

- Pardini DA (2008). Novel insights into longstanding theories of bidirectional parent-child influences: Introduction to the special section. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(5), 627–631. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9231-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, Cox MJ, & Snow KL (2007). School readiness and the transition to kindergarten in the era of accoundability, Baltimore, MD: Paul Brookes Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Hershey KL, & Fisher P. (2001). Investigations of temperament at 3–7 years: The Children’s Behavior Questionnaire. Child Development, 72, 1394–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearer CL, Crouter AC, & McHale SM (2005). Parents’ perceptions of changes in mother-child and father-child relationships during adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Research, 20(6), 662–684.doi: 10.1177/0743558405275086 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Egeland B, Carlson EA, & Collins WA (2005). The development of the person. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Teti DM, & Candelaria M. (2002). Parenting competence In Bornstein MH (Eds.). Handbook of parenting: Social conditions and applied parenting, (pp. 149–180). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Thelen E, & Smith LB (1998). Dynamic systems theories. Handbook of child psychology. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker LR & Lewis C. (1973). A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika, 38(1), 1–10. doi: 10.1007/BF02291170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MT & Kenny S. (2014). Longitudinal links between fathers’ and mothers’ harsh verbal discipline and adolescents’ conduct problems and depressive symptoms. Child Development, 85(3), 908–923. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Christ SL, Mills-Koonce WR, Garrett-Peters P, & Cox MJ (2013). Association between maternal sensitivity and externalizing behavior from preschool to preadolescence. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 34(2), 89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]