Abstract

Background:

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is a major cause of mortality in developing countries such as India. Most cardiac arrests happen outside the hospital and are associated with poor survival rates due to delay in recognition and in performing early cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). Community CPR training and telephone CPR (T-CPR) in the dispatch centers have been shown to increase bystander CPR rates and survival.

Objectives:

The aim of this study is to identify the significance of T-CPR in OHCA and to discuss its implementation in the health system to improve OHCA outcomes in India.

Materials and Methods:

A descriptive research study methodology was adopted following a literature search.

Results:

The search criterion “Cardiovascular diseases” resulted in 162, “Out-side hospital cardiac arrest” in 50; For a comprehensive overview, these publications were evaluated looking for data on T-CPR incidence, criteria for detecting OHCA by emergency medical dispatchers, sensitivity and specificity, and BCPR.

Conclusion:

This current research stresses the scale and seriousness of the implementation of T-CPR in OHCA in India.

Keywords: Bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, dispatcher-assisted instructions, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, prehospital care, telephone cardiopulmonary resuscitation

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) are the major cause of mortality globally, as well as in India accounting for almost 17 million deaths annually or 30% of all global mortality.[1] The Global Burden of Disease study estimate of age-standardized CVD death rate of 272/100,000 population in India is higher than the global average of 235/100,000 population.[2] According to the World Health Report; CVD will be the largest cause of death and disability by 2020 in India. In 2020, 2.6 million Indians are predicted to die due to coronary heart disease which constitutes 54.1% of all CVD deaths. Nearly half of these deaths are likely to occur in young- and middle-aged individuals (30–69 years).[3] The global incidence of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is 62/100,000. Estimated survival to hospital discharge is 8% (8% of 62/100.000 = 5/100.000) and not much has changed for many years. When sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) happens, the person collapses, becomes unresponsive, and is not breathing normally. Survival depends on the quick actions of people nearby to activate Emergency Medical Services (EMS) and to start cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), and if available, use an automated external defibrillator (AED) as soon as possible. About half of the cases are witnessed.[4] Successful resuscitation requires a synchronized set of interdependent rescuer actions (the “chain of survival”), of which the initial links are immediate recognition of cardiac arrest and activation of the emergency response system, early resuscitation (CPR) with an emphasis on chest compressions, and rapid defibrillation.[5] Bystander CPR (BCPR) has been shown to double or even triple survival from OHCA.[6,7,8,9,10] BCPR is a key link in the chain of survival for OHCA.[5,11,12,13,14]

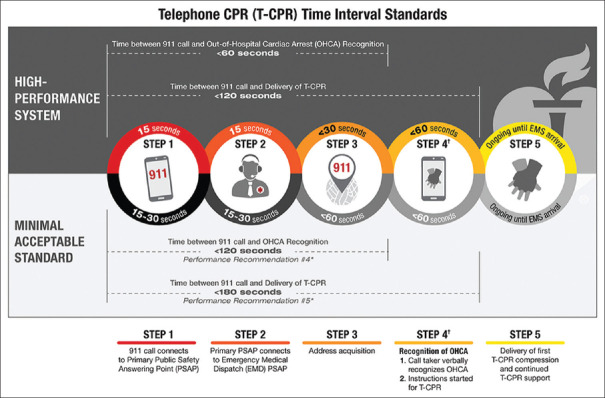

To improve the survival rates resuscitation council from all over the globe on June 6–7, 2015 at the Utstein Abbey near Stavanger, Norway, 36 EMS leaders, researchers, and experts from throughout the world convened to address the challenge of how to increase community cardiac arrest survival and how to achieve implementation of best practices and worthwhile programs. The attendees called for the establishment of a Global Resuscitation Alliance (GRA) and issued a report laying out ten programs to improve survival and ten steps to achieve successful implementation. The GRA (formally established in 2016 at the EMS 2016 Conference) expands internationally the reach and utility of the Resuscitation Academy concept developed in King County, Seattle since 2008. Such a global effort will promote best practices and offer help with implementation to countless communities. The Utstein style is a standardized reporting format for OHCA [Figure 1].[15]

Figure 1.

The Utstein formula for survival[15]

Indian Resuscitation Council (IRC) suggested that the rescuer should call from his mobile, with speakerphone on, and continue following the steps of Compression-Only Life Support (COLS).[16] The rescuer should call to 108 has been proposed as the pan-India emergency contact number, and it has been accepted by many states of India.

Evolution of telephone cardiopulmonary resuscitation

In 1960, Kouwenhoven et al.[17] described combined chest compression and rescue breathing as basic life support CPR for the first time. In 1974, the first recommendations for CPR[18] were issued and since then international CPR guidelines have been published at regular intervals. Instructions on CPR through telephone through a dispatcher (T-CPR) were proven to be an effective and reasonable method to improve the rate and quality of bystander-performed resuscitation. T-CPR is most effective in communities where people have already trained CPR.[19]

International awareness of telephone cardiopulmonary resuscitation

The Resuscitation Academy since its inception in 2008, has actively promoted T-CPR as an effective step in improving community survival rates. In 2015, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommended the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration take the lead to promote T-CPR and in 2017, the American Heart Association (AHA) issued T-CPR program guidelines and performance goals. Recently, authorities in the USA and Norway issued national recommendations on T-CPR training in the dispatch centers.[6]

In the United States, the AHA has committed to doubling OHCA survival by 2020 by implementing a concept called T-CPR.[20,21,22,23,24]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study adopted a descriptive research methodology, and a literature search was performed with PubMed and Google Scholar using the keywords “sudden cardiac death,” “India” and a combination of “Cardiovascular diseases,” “sudden death” causes or cardiovascular diseases, DACPR, T-CPR, AHA guidelines on OHCA, and T-CPR. Only English language articles were included in the literature review.

RESULTS

The search criterion “Cardiovascular diseases” resulted in 162, “Out-side hospital cardiac arrest” in 50, for a comprehensive overview, these publications were evaluated looking for data on T-CPR incidence, criteria for detecting OHCA by emergency medical dispatchers, sensitivity and specificity, and BCPR. Another 62 publications were considered for further analyses.

Studies conducted at GVK Emergency Management and Research Institute (GVK EMRI) 108 ambulance services with chief complaints Cardiac/Chest Pain, the following were observed: (a) in 2009, over seven continuous days data were collected and 585 patients were enrolled. The mean patient age was 48.5 years and 56% had CVD risk factors. Mortality ratios before hospital arrival were 13.8%, at 48 h, 19.3%, and at 30 days 23.2%.[25] (b) in 2015, all reported cases of cardiac emergencies to “108 services” data were analyzed in 11 states, India. Often (82.8%) people called 108 > 6 h of symptom onset. At 48 h, there were 2,675 (1.1%) reported deaths.[26] (c) T-CPR or dispatch-assisted CPR by Emergency Response Officer at 108 call center, a pilot study conducted for the first time at GVK EMRI in the state of Telangana, India in the year 2017–2018. A total 599 cases were given instructions to perform CPR to the bystanders of the victim with out-of-hospital-cardiac-arrest cases. Of 599, 117, (20%) did CPR, 482, (80%) did not performed CPR.[27]

DISCUSSION

Situation in India

OHCA is one of the leading causes of death in India due to cardiovascular diseases. Around 98% of Indians are not provided with basic life-saving techniques of CPR at the time of SCA. The chain of survival, with its four prehospitals links of early access, early CPR, early defibrillation, early advanced care, and illustrates the most critical elements of addressing SCA. The lack of knowledge of CPR skills and training among bystanders in the community is the main reason why most OHCA patients in India do not get appropriate and timely CPR. Hence, the outcome of OHCA in India is poor, as compared to other countries, where EMS systems are an integral part of the health-care system, which routinely provides CPR to every victim of cardiac arrest. However, still many of them are not getting help on time due to a lack of awareness on when to respond. IRC also recommends COLS for the management of the victim with cardiopulmonary arrest in adults increases the optimal outcome of the victim outside the hospital by untrained laypersons.

In other countries, EMS utilizes telecommunicators as first responders as a critical link in the cardiac arrest chain of survival. The telecommunicator, in partnership with the caller, will identify if a patient is in cardiac arrest and provides the initial level of care by delivering T-CPR instructions and quickly dispatches the ambulance. India now has the second-largest telecom network in the world, next only to China, crossed the landmark of one billion telephone subscribers in the year 2015–2016. The overall teledensity in India stands at 93.74% as of August 2017. Hence, India has a very good technology for communication and can be utilized in saving lives.

Telecom Regulatory Authority of India recommends 112 as all-in-one emergency number for India

The Telecom Regulatory Authority of India has released a recommendation article on the implementation of “Single Number based Integrated Emergency Communication and Response System.” A single number “112” can be used for all emergency phone calls across the country, including for police, fire, and ambulance. The government integrated all existing emergency numbers such as 100, 101, 102, and 108 into the proposed “112” helpline number.

Increasing survival rates worldwide

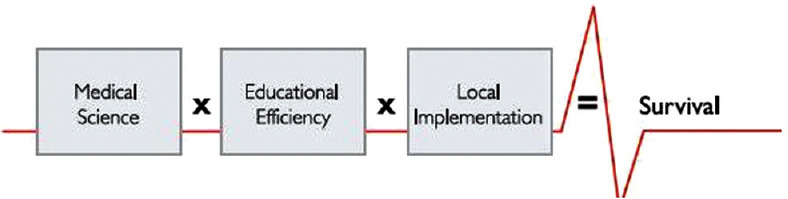

EMS systems worldwide show improvements. In Singapore, BCPR and survival remained low for many years. Following the implementation of dispatcher training in T-CPR and teaching CPR in the community, CPR provision before ambulance arrival has improved from around 20% to almost 60%.[13] In Korea, national implementation of T-CPR combined with massive increase in community CPR training has increased CPR before ambulance arrival. According to the results of a study published in Annals of Emergency Medicine, the total BCPR rate increased from 30.9% in the first quarter of 2012 to 55.7% in the fourth quarter of 2014. In Denmark, a combined strategy of community CPR training and T-CPR tripled CPR before ambulance arrival and tripled survival. National Organizations, such as the AHA and the IOM strongly endorse T-CPR. These organizations recognize the need for specific training in how to recognize cardiac arrest over the phone and how to rapidly provide quality instructions as well as the need for a robust and ongoing quality improvement program. Initiatives to train large numbers of community bystanders through schools or voluntary organizations have been successful in many countries (including the United States, Norway, Sweden, Singapore, Korea, the United Kingdom, and Denmark) as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Improvement in survival among health systems that combine community cardio pulmonary resuscitation training with telephone cardio pulmonary resuscitation support. Source: CPR & First Aid Emergency Cardiovascular Care. May 2018 < https://cpr.heart.org/AHAECC/CPRAndECC/ResuscitationScience/TelephoneCPR/RecommendationsPerformanceMeasures/UCM_477526_Telephone- CPR-T-CPR-Program-Recommendations-and-Performance-Measures.jsp>

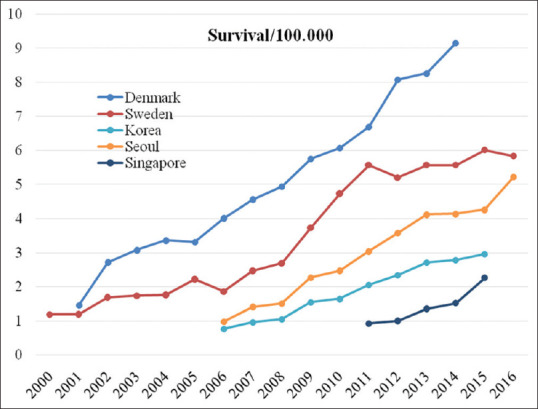

Based on the above studies, our strong recommendation is to implement T-CPR in the dispatch centers and to create awareness in the community by CPR training with the help of local government support. The awareness should be emphasized by the appropriate education system to motivate people. Time is very crucial for patients suffering from a cardiac arrest, only difference is of having a golden hour and having golden seconds to save a life. Timely intervention is very important in saving life of the patient, which can happen only through public education. Hence, community CPR training should be encouraged and provided at all levels, starting in the school. We will see not only an increase in the number of cardiac arrest survivors worldwide but also the social benefits of enthusiastic and positive young people. Good Samaritan Law offers legal protection to people who give reasonable assistance to those who are injured, ill, in peril, or otherwise incapacitated. The Ministry of Road Transport and Highways recognized the problem and issued the Good Samaritan Guidelines in 2015.[26] The Supreme Court of India then gave these guidelines the force of law in the year 2016. All Indian citizens are protected under it. According to the World Health Organization, bystanders can help in the absence of established EMS, and hence that a bystander in our country will be a Good Samaritan. This kind of initiative from the government is required to protect the dispatcher and bystander to save more lives, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Telephone cardiopulmonary resuscitation time interval standards. Source: CPR and First Aid Emergency Cardiovascular Care. May 2018 <https://cpr.heart.org/AHAECC/CPRAndECC/ResuscitationScience/TelephoneCPR/RecommendationsPerformanceMeasures/UCM_477526_Telephone- CPR-T-CPR-Program-Recommendations-and-Performance-Measures.jsp>

T-CPR program is safe to implement in India. One of the studies (circulation, Journal of the American Heart Association) revealed that 247 patients received CPR, not in cardiac arrest, 4% suffered some injury or fracture, and no patients suffered visceral organ injury.

Survival data are to be managed and saved for future growth and improvements that can be done in the form of registry model which already exist and is followed by the GRA. The 2015 Guidelines, the GRA recommendation, and the latest evidence are a solid foundation for implementing T-CPR in India. Cardiac registry is already maintained in GVK EMRI since December 2015.

T-CPR is a modern and promising concept within the emergency process. T-CPR is initiated in 108 GVK EMRI, Hyderabad. The pilot phase results have shown the feasibility of T-CPR in India. The following are urgently needed and important to improve the chain of survival: preparation and publishing of universal key recommendations for T-CPR, establishment of interprofessional cooperation and networks, and performing high-quality studies to point out strengths and weaknesses of T-CPR. This will require the cooperation and commitment of public health sectors, clinicians, interested laypersons, the legal community, makers of public policy, and government.

One more method to implement the T-CPR or to create public awareness about CPR, the concept of telemedicine has become increasingly useful in the health-care sector, particularly, to reach out to rural and remote regions where direct health-care delivery is hard to access. Telemedicine helps combat the problem by assisting health-care providers in addressing cardiac arrests until help arrives. By utilizing the technology, the mobile application to alert the cardiac arrest and which notifies trained citizens of nearby cardiac emergencies and the location of the nearest AED until the advance help arrives can also improve the survival rate.

CONCLUSION

India, as a developing country, has all the necessary components in place such as health system, EMS system, and telecommunication system. By involving all systems together, training the communities and dispatch centers with lifesaving technique called CPR and creating awareness in the community about When to Act, Why to Act, and How to Act definitely can improve patient outcome and survival rate in OHCA. Most of the people are unaware of the right way to do CPR during emergencies. There is an urgent need to implement T-CPR in EMS dispatch systems and to introduce the knowledge on T-CPR and community CPR training in schools and colleges and even at the community level, and hence that family members can give immediate medical assistance in times of emergency when the breathing or heartbeats stop. T-CPR has been recognized as an integral component of an emergency medical system response to OHCA and holds enormous potential to increase bystander response and thus survival from cardiac arrest.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gupta R, Panniyammakkal J, Chaturvedi V, Prabhakaran D, Srinath Reddy K. National Cardiovascular Disease Database. Report. India: Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India and World Health Organization. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prabhakaran D, Jeemon P, Roy A. Cardiovascular Diseases in India: Current Epidemiology and Future Directions. [Last accessed on 2019 Apr 10];Circulation. 2016 133:1605–20. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.008729. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.008729 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajeswari K, Vaithiyanathan V, Neelakantan TR. Feature Selection in Ischemic Heart Disease identification using feed forward neural networks. [Last accessed on 2019 Mar 12];Procedia Engineering. 2012 41(Iris):1818–23. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2012.08.109 . [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kleinman ME, Brennan EE, Goldberger ZD, Swor RA, Terry M, Bobrow BJ, et al. Part 5: Adult Basic Life Support and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Quality: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2015;132:S414–35. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sasson C, Rogers MA, Dahl J, Kellermann AL. Predictors of survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:63–81. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.889576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rea TD, Eisenberg MS, Becker LJ, Murray JA, Hearne T. Temporal trends in sudden cardiac arrest: A 25-year emergency medical services perspective. [Last accessed on 2019 Mar 08];Circulation. 2003 107:2780–5. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000070950.17208.2A. Available from: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/rapporter/sammen-redder-vi-liv-strategidokument . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rea TD, Eisenberg MS, Becker LJ, Murray JA, Hearne T. Temporal trends in sudden cardiac arrest: A 25-year emergency medical services perspective. Circulation. 2003;107:2780–5. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000070950.17208.2A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malta Hansen C, Kragholm K, Pearson DA, Tyson C, Monk L, Myers B, et al. Association of bystander and first-responder intervention with survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in North Carolina, 2010-2013. JAMA. 2015;314:255–64. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.7938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Avalli L, Mauri T, Citerio G, Migliari M, Coppo A, Caresani M, et al. New treatment bundles improve survival in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients: A historical comparison. Resuscitation. 2014;85:1240–4. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Travers AH, Rea TD, Bobrow BJ, Edelson DP, Berg RA, Sayre MR, et al. Part 4: CPR overview: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010;122:S676–84. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herlitz J, Svensson L, Holmberg S, Angquist KA, Young M. Efficacy of bystander CPR: Intervention by lay people and by health care professionals. Resuscitation. 2005;66:291–5. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McNally B, Robb R, Mehta M, Vellano K, Valderrama AL, Yoon PW, et al. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest surveillance – Cardiac arrest registry to enhance survival (CARES), United States, October 1, 2005-December 31, 2010. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2011;60:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaillancourt C, Stiell IG, Wells GA. Understanding and improving low bystander CPR rates: A systematic review of the literature. CJEM. 2008;10:51–65. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500010010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graham R, McCoy MA, Schultz AM. Committee on the Treatment of Cardiac Arrest: Current Status and Future Directions, Board on Health Sciences Policy, Institute of Medicine. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eisenberg M, Lippert FK, Castren M, Moore F, Ong M, Rea T, et al. Improving Survival from Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: Case Report. Utstein Abbey: Global Resuscitation Alliance; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Field JM, Hazinski MF, Sayre MR, Chameides L, Schexnayder SM, Hemphill R, et al. Part 1: Executive summary: 2010 American heart association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2010;122:S640–56. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kouwenhoven WB, Jude JR, Knickerbocker GG. Closed-chest cardiac massage. JAMA. 1960;173:1064–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.1960.03020280004002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carveth S. Editorial: Standards for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiac care. JAMA. 1974;227:796–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.1974.03230200054012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasselqvist-Ax I, Riva G, Herlitz J, Rosenqvist M, Hollenberg J, Nordberg P, et al. Early cardiopulmonary resuscitation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2307–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1405796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanaka Y, Taniguchi J, Wato Y, Yoshida Y, Inaba H. The continuous quality improvement project for telephone-assisted instruction of cardiopulmonary resuscitation increased the incidence of bystander CPR and improved the outcomes of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests. Resuscitation. 2012;83:1235–41. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song KJ, Shin SD, Park CB, Kim JY, Kim DK, Kim CH, et al. Dispatcher-assisted bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a metropolitan city: A before-after population-based study. Resuscitation. 2014;85:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bobrow BJ, Spaite DW, Vadeboncoeur TF, Hu C, Mullins T, Tormala W, et al. Implementation of a Regional Telephone Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Program and Outcomes After Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1:294–302. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.0251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wissenberg M, Lippert FK, Folke F, Weeke P, Hansen CM, Christensen EF, et al. Association of national initiatives to improve cardiac arrest management with rates of bystander intervention and patient survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2013;310:1377–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Study on Impact of Good Samaritan Law. November, 2018. Save Life Foundation. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wen J, Chang J, Strehlow M. Characteristics and Outcomes of pre Hospital Chest Pain Patients in India. 2010 Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2010:63. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramana Rao GV, Rajanarsing Rao HV, Kesav Reddy G, Prasad MN. Epidemiological study on cardiac emergencies in Indian states having GVK emergency management and research institute services. J Soc Health Diabetes. 2016;4:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janumpally R, Gimkala A, Ramana Rao GV. Telephone CPR – An Evidence Based Cost-Effective Solution for out of Hospital Cardiac Arrest (OHCA) in India – A Successful Pilot at 108 GVK EMRI, Hyderabad.20th Annual Conference of Society for Emergency Medicine India (SEMI) – EMCON 2018. Bengaluru. 2018:255. [Google Scholar]