ABSTRACT

D-penicillamine (DPA) is an amino-thiol that has been established as a copper chelating agent for the treatment of Wilson’s disease. DPA reacts with metals to form complexes and/or chelates. Here, we investigated the survival rate extension capacity and modulatory role of DPA on Cu2+-induced toxicity in Drosophila melanogaster. Adult Wild type (Harwich strain) flies were exposed to Cu2+ (1 mM) and/or DPA (50 μM) in the diet for 7 days. Additionally, flies were exposed to acute Cu2+ (10 mM) for 24 h, followed by DPA (50 μM) treatment for 4 days. Thereafter, the antioxidant status [total thiol (T-SH) and glutathione (GSH) levels and glutathione S-transferase and catalase activities] as well as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) level and acetylcholinesterase activity were evaluated. The results showed that DPA treatment prolongs the survival rate of D. melanogaster by protecting against Cu2+-induced lethality. Further, DPA restored Cu2+-induced depletion of T-SH level compared to the control (P < 0.05). DPA also protected against Cu2+ (1 mM)-induced inhibition of catalase activity. In addition, DPA ameliorated Cu2+-induced elevation of acetylcholinesterase activity in the flies. The study may therefore have health implications in neurodegenerative diseases involving oxidative stress such as Alzheimer’s disease.

Keywords: Copper, Oxidative stress, D-Penicillamine, Drosophila melanogaster

Introduction

Copper is a transition metal strategic to cellular metabolism especially in the brain.1 Copper tissue levels in the human brain and in the liver are about 5 μg/g, while 0.3–0.5 μM copper concentration is found in the cerebrospinal fluid.2,3 Copper exists in two oxidation states making it an essential component of key enzymes involved in various biological processes including oxidative phosphorylation, modulation of neurotransmission etc.4,5 In such enzymes, copper is found as prosthetic groups or bound to enhance activity as seen in superoxide dismutase (Cu-Zn-SOD), dopamine–β-hydroxylase, ceruloplasmin and cytochrome oxidase.6,7 Importantly, free copper concentrations is tightly regulated in healthy cells especially at very low levels4; however, copper can be deleterious at high concentrations seemingly due to its ability to transit between oxidation states (Cu+ to Cu2+).8–10 Sources of unrestrained intake of copper include foods such as liver, seafood, nuts, whole grains and dried fruits. Residues of pesticides in contaminated soils and drinking water as well as leaching of copper from corroded water pipes also increase the immoderate consumption of copper.11–13

Copper is transported via a coordinated assembly of proteins such as copper transporter 1 (CTr1) and nonspecific divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1).14 The efflux of copper is in turn mediated by copper ATPases, such as copper transport protein alpha (ATP7A) and beta (ATP7B).15 Other mediators of copper transport include copper chaperones such as Atx1p/Atox1 which enhance the delivery of copper to ATPpase copper requiring proteins, and Cox 17 which transports copper to the mitochondrial enzyme cytochrome c oxidase.16–18

Copper dysmetabolism has been associated with toxic effects believed to be caused by oxidative stress and has been implicated in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders such as Wilson’s disease (WD), Menkes disease, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.19

Oxidative stress and damage are implicated in the pathogenesis and progression of AD20; however, several controversies and speculations have been made on the precise role of Aβ peptide and copper ions.21,22 In some spheres, adductions that Aβ toxicity is due to reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation in the presence of the Aβ-Cu (II) complex were made, while others debated an antioxidant role for Aβ.23,24 Given the neurotoxic potential of copper and the associated interactions, strategies that disrupt the Cu–Ab interaction by using chelators was proposed as a therapeutic strategy, which is an emerging trend in current research. Hence, there is immense need to develop such a suitable copper chelator that could prevent amyloid-β aggregation by effectively sequestering extra Cu2+ ions. Similar effects may suffice in other neurodegenerative diseases.

D-Penicillamine (DPA; β-β-dimethylcysteine or 3-mercapto-D-valine) is a sulfhydryl-containing amino acid and a degradation product of penicillin (Fig. 1). DPA is used mainly as a chelating agent in copper poisoning and in the treatment of WD.25 DPA has the ability to function as either a mono-, bi- or tridentate ligand. The thiol of DPA binds to Cu (I) and eliminates it through urine both in normal people and in patients with WD.26,27 Despite the fact that DPA has been reported to efficiently reduce excess Cu in the system,28 other authors found that in the process of Cu chelation by DPA, Cu (II) is reduced to its Cu (I) form, which leads to the generation of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and other ROS.28–30 We therefore envision that investigating the chelating property of DPA in different animal model such as invertebrates like Drosophila melanogaster may shed more light on the protective ability of DPA in copper-induced toxicity.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of D-penicillamine (A) and D-penicillamine disulfide (B).

Drosophila melanogaster is a nonmammalian model that has been extensively employed as an in vivo model system to characterize the effects of environmental neurotoxic metals.31–36 Also, the fly expresses proteins involved in the metabolism of biometals such as ferritin,37 transferrin,38 iron regulatory proteins,38 DMT139 and DmATP740,41 similar to human. Consequently, we investigated the protective potential of DPA on copper-induced toxicity in D. melanogaster.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

The 1-chloro-2, 4-dinitrobenzene, 5,5′-dithiobis (2-nitrobenzoic acid), acetylthiocholine iodide, were purchased from Sigma (USA). Copper sulfate and DPA were procured from A K Scientific, 30023 Ahern Ave, Union City, CA 94587, USA. Other reagents were commercial products of the highest analytical grade.

Drosophila melanogaster stock and culture

Drosophila melanogaster wild-type (Harwich strain) flies were obtained from the National Species Stock Center (Bowling Green, OH, USA). The flies were maintained and reared in Biochemistry Department, University of Ibadan, Nigeria on cornmeal medium containing 1% w/v brewer’s yeast, 2% w/v sucrose, 1% w/v powdered milk, 1% w/v agar and 0.08% v/w nipagin at constant temperature and humidity (22–24°C; 60–70% relative humidity) under 12 h dark/light cycle conditions.

Cu2+acute and chronic exposures and DPA treatment

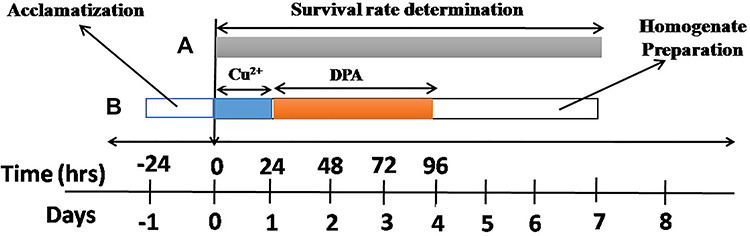

Copper sulfate (CuSO4) and DPA were added into the medium at a final concentration of Cu2+ 1 mM and/or DPA 50 μM, respectively. Wild type D. melanogaster of both genders of 1–3 days old were divided into four groups with 50 flies/vial: (1) Control; (2) DPA (50 μM); (3) Cu2+ (1 mM); (4) Cu2+(1 mM) plus DPA (50 μM) for 7 days. Further, flies were divided into three groups (n = 5) for acute Cu2+ study: (1) control; (2) Cu2+ (10 mM); (3) Cu2+(10 mM) plus DPA (50 μM). Here, flies were first exposed to Cu2+ (10 mM) for 24 hrs followed with DPA (50 μM) treatment for 4 days. The choice of 1 mM Cu2+ was informed by a study carried out by Halmenschelager and Rocha42, Abolaji et al.43 and 50 μM DPA from Bonilla-Ramirez et al.44 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Treatment regimen and duration of Cu2+ and DPA treatments. (A): Flies were exposed to DPA and/or Cu2+ for 7 days for the determination of survival rate and biochemical assays. (B): Flies were first exposed to Cu2+ for 24 hr followed with DPA treamtment for 4 days.

In vivo assays

Survival rates determination

The survival rate was determined daily by counting the number of living flies until the end of each experimental period (7 days). A total of 200 flies per group were included in the survival data (40 flies/vial, n = 5) as previously reported.45

Ex vivo assays

Preparation of samples for biochemical assays

For the biochemical assays, flies were anaesthetized once, weighed, homogenized in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 (1: 10 (flies/volume (μL)), and centrifuged at 10 000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was separated from the pellets into Eppendorf tubes, kept at −20°C and used to determine acetylcholinesterase (AChE), catalase and glutathione S-transferase (GST) activities as well as T-SH and H2O2 levels. Notably, all the assays were carried out in duplicates for each of the five replicates of copper sulfate and the DPA concentrations.

Determination of selected oxidative stress indices and AChE activity

We determined protein concentration using the method described by Lowry et al.46 Total thiol content was carried out with the method of Ellman.47 GST activity was determined according to the method of Habig and Jakoby.48The activity of catalase was determined using the method of Aebi.49 We evaluated AChE activity using the method of Ellman et al.50 Hydrogen peroxide level was determined according to the method of Wolff.51

Statistical analysis

The Kaplan–Meier’s method was used to analyze the survival rate and comparisons were made with the log-rank tests. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM. A One-way Analysis of variance was used to assess the significant differences among multiple groups followed by Dunett’s post hoc test. Statistically significant differences indicated at P < 0.05, using the GraphPad Prism 5.0 software.

Results

Survival rates of flies exposed to Cu2+ and DPA

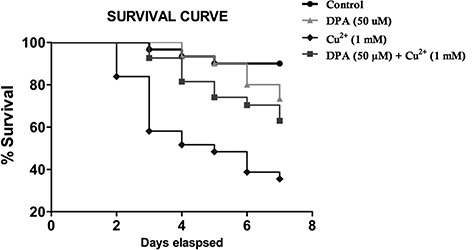

Cu2+ (1 mM) exposure resulted in a significant dose-dependent decrease in survival of flies compared with the control groups (P < 0.05). The Cu2+-induced mortality was ameliorated significantly by DPA (Fig. 3), indicating DPA’s ability to prolong survival and protect against Cu2+-induced mortality.

Figure 3.

Effect of DPA and Cu2+ on survival of Drosophila melanogaster. This was to investigate the ability of DPA to prolong survival. The p values (log-rank tests) for each group include: Ctrl versus DPA 50 μM (P = 0.1214), Cu2+ 1 mM (P < 0.05), DPA50 μM + Cu2+ 1 mM (P < 0.05). The maximum lifespan in each group represents the percentage of surviving flies.

DPA modulates chronic Cu2+-induced accumulation of H2O2 level, depletion of T-SH and inhibition of catalase activity in D. melanogaster

The exposure of D. melanogaster to Cu2+ (1 mM) and DPA for 7 days indicated that DPA had no effect on Cu2+-induced inhibition of GST activity (Fig. 4C, P < 0.05) in the flies. However, DPA restored Cu2+-induced depletion of total thiol level (Fig. 4A) and ameliorated Cu2+-based inhibition of catalase activity (Fig. 4E) in D. melanogaster (P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Effects of DPA and chronic Cu2+ exposure on oxidative stress parameters. Total thiol level (A), glutathione level (B), glutathione S-transferase activity (C), hydrogen peroxide level (D), catalase activity (E) in Drosophila melanogaster. Values are expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (n = 5). Significant differences from the control are indicated by asterisk (P < 0.05). Significant differences from the Cu2+-treated group are indicated by hash (P < 0.05).

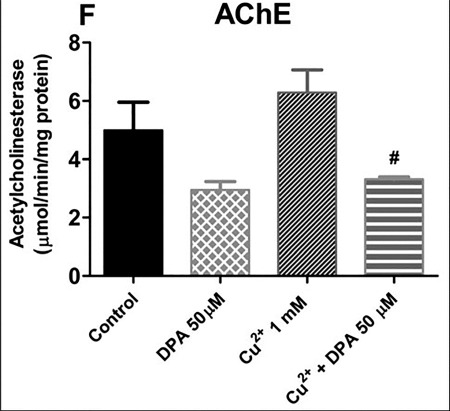

DPA effect on AChE activity in D. melanogaster

We noted that, Cu2+ (1 mM) caused a marked elevation in AChE activity in flies, while flies co-treated with 50 μM DPA had AChE activity restored to level comparable to DPA-treated group (P < 0.05; Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Effect of DPA and chronic Cu2+ exposure on acetylcholinesterase activity. Effect of curcumin on Cu2+-induced toxicity in treated flies. AChE activity in flies after treatment for 7 days. Values are expressed as mean ± standard error of mean. Significant differences from the control are indicated by asterisk (P < 0.05). Significant differences from the Cu2+-treated group are indicated by hash (P < 0.05).

DPA moderates acute Cu2+-induced depletion of T-SH in D. melanogaster

We observed significant depletion of total thiol level (Fig. 6A, P < 0.05) in Cu2+-exposed flies along with significant inhibition of catalase activity (Fig. 6E, P < 0.05) when compared with the control group. However, cotreatment with DPA only augmented total thiol level without ameliorating Cu2+ (10 mM)-induced inhibition of catalase and GST activities as well as reduction of GSH (Fig. 6B) and elevation of H2O2 (Fig. 6D) levels and increased catalase activity (Fig. 6E) in the flies.

Figure 6.

Effects of DPA and Cu2+ on oxidative stress and antioxidant parameters. Total thiol level (A), glutathione level (B), activity (C), hydrogen peroxide level (D) and catalase activity (E) in Drosophila melanogaster. Values are expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (n = 5). Significant differences from the control are indicated by asterisk (P < 0.05). Significant differences from the Cu2+-treated group are indicated by hash (P < 0.05).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that exposure of D. melanogaster to Cu2+ increased mortality and induced oxidative stress. Comparable to xenobiotic-induced neurotoxicity as observed in rotenone,52paraquat53 and MPTP54 in Drosophila, metals can promote neuronal loss of the dopaminergic neurons. Specifically, elevated copper levels resulted in the generation of ROS, eliciting oxidative damage.55 The molecular mechanisms responsible for the uptake, efflux, distribution and regulation of metals are conserved in D. melanogaster.55–58 Thus, this study was carried out to understand if DPA, a notable copper chelator, could protect D. melanogaster against Cu2+-induced toxicity.

Although, previous studies have highlighted the role of DPA in reducing serum oxidative stress in AD patients,59 improving antioxidant capacity in WD60 and depleting body copper load,61 these studies have not addressed the possible implications of copper toxicity or likely exposure of patients to copper. Our study addressed copper-induced toxicity in an invertebrate model whose metabolic networks are capable of genetic manipulation.

Flies exposed to Cu2+ showed decreased survival rate during the 7-day exposure period, while cotreatment of Cu2+ with DPA ameliorated Cu2+-induced lethality. This result indicated a possible antioxidant potential of DPA that possibly decreased the observed premature mortality of D. melanogaster exposed to Cu2+.62

We observed that DPA did not ameliorate Cu2+-induced accumulation of H2O2 and inhibition of catalase activity in the acute study in D. melanogaster. This observation may be due to the reported interaction between DPA and copper resulting in the formation of multivalent DPA-copper complex (Cu8ICu6II (DPA)12Cl)5−,63 which partly explains the cause for the overproduction of H2O2.63 Catalase is a heme-containing enzyme that catalyzes the dismutation of H2O2 to molecular oxygen and water in order to minimize oxidative stress-mediated toxicity.64 One limitation of the present study was that we did not carry out the level of copper in the flies. Nevertheless, the H2O2 accumulation from the direct effect of copper redox state transitions was not detoxified by catalase, due to Cu2+(10 mM)-induced inhibition of its activity in the acute study.

Furthermore, DPA did not ameliorate Cu2+-induced inhibition of GST activity. GSTs are enzymes with cysteine-rich domains64,65 involved in the elimination of reactive molecules via conjugation with GSH. Thus, the observation that Cu2+ inhibited GST activity is as a result of copper-mediated oxidation of its thiol groups, thus modifying its native structure and conformation resulting in reduced activity. Further evidence indicated that copper interacts with GSH and forms Cu(I)-[GSH](2) complex, which reduces molecular oxygen into superoxide.65 However, DPA forestalled Cu2+-induced depletion of T-SH presumably due to the buffering capacity of other thiol-containing proteins in the system.

Moreover, DPA attenuated Cu2+ (1 mM)-induced elevation of AChE activity. AChE is an enzyme that participates in cholinergic neurotransmission by hydrolyzing acetylcholine to acetate and choline. It plays important role in learning, memory and locomotor activities. Cognitive deficits and behavioral functions can be easily modulated by cholinergic signaling and this has been shown to be altered by Cu2+.66–68 Thus, DPA may modulate locomotor activity and cognitive deficits in D. melanogaster.

Conclusion

In summary, we report that Cu2+ exposure significantly abrogated survival and increased oxidative stress in D. melanogaster. We also showed that Cu2+ impacted the cellular antioxidant status negatively by generation of oxidative stress. However, DPA, via its chelating potential, ameliorated Cu2+ (1 mM)-induced toxicity, but partially lessened Cu2+ (10 mM)-induced toxicity in D. melanogaster. Further studies that aim to evaluate the expression of notable copper transporters ATP7A and CTR1 so as to estimate transportation activity of copper in D. melanogaster as well as studies quantifying the magnitude and effects of the copper-DPA complex are called for. Also, studies that aim at assessing the effect of DPA in Drosophila transgenic models of WD are also warranted. This study may thus be of public health significance as it provided further insights on DPA’s protective mechanisms against copper-induced toxicity.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Choi BS, Zheng W. Copper transport to the brain by the blood-brain barrier and blood CSF barrier. Brain Res 2009;1248:14–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Capo C, Arciello R, Squitti M et al. Features of ceruloplasmin in the cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer’s disease patients. BioMetals 2008;21:367–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nischwitz V, Bethele A, Michalke B. Speciation analysis of selected metals and determination of their total contents in paired serum and cerebrospinal fluid samples: an approach to investigate the permeability of the human blood-cerebrospinal fluid-barrier. Anal Chim Acta 2008;627:258–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Popescu BF, Robinson CA, Rajput A et al. Iron, copper, and zinc distribution of the cerebellum. Cerebellum 2009;8:74–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gaggelli E, Kozlowski H, Valensin D et al. Copper homeostasis and neurodegenerative disorders (Alzheimer’s disease, prion, and Parkinson’s diseases and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis). Chem Rev 2006;106:1995–2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Montes S, Rivera-Mancia S, Diaz-ruiz A, et al. Copper and copper proteins in Parkinson’s disease. Oxidative Med Cell Longev 2014;147251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Osredkar J, Sustar N. Copper and zinc, biological role and significance of copper/zinc imbalance. J Clinic Toxicol 2011;S3:001. doi: 10.4172/2161-0495.S3-001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Klimaczewski CV, Ecker A, Piccoli B et al. Peumus boldus attenuates copper-induced toxicity in Drosophila melanogaster. Biomed Pharmacother 2018;97:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mercer S W, Wang J, Burke R, In vivo modeling of the pathogenic effect of copper transporter mutations that cause Menkes and Wilson diseases, motor neuropathy, and susceptibility to Alzheimer’s disease. J Biol Chem, 2017, 292(10), 4113–4122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schlichting D, Sommerfeld C, Müller-Graf C, et al. Copper and zinc content in wild game shot with lead or non-lead ammunition–implications for consumer health protection. PLoS One, 201712(9), e0184946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. WHO Copper in Drinking-Water. Background Document for Preparation of WHO Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality. Geneva: World Health Organization., 2003, WHO/SDE/WSH/03.04/88. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cockell KA, Bertinato J, LÁbbé MR. Regulatory frameworks for copper considering chronic exposures of the population. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;88:863–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brewer GJ. Metals in the causation and treatment of Wilson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease, and copper lowering therapy in medicine. Inorg Chim Acta 2012;393:135–41. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tandy S, Williams M, Leggett A et al. NRAMP2 expression is associated with pH dependent iron uptake across the apical membrane of human intestinal Caco-2 cells. J BiolChem 2000;275:1023–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lutsenko S, Efremov RG, Tsivkovskii R, Walker JM. Human copper-transporting ATPase ATP7B (the Wilson’s disease protein): biochemical properties and regulation. J Bioenerg Biomembr 2002;34:351–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Balamamurugan K, Egli D, Hua H, et al. Copper homeostasis in Drosophila by complex interplay of import, storage and behavioral avoidance. EMBO J, 2007, 26(4), 1035–1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Markossian KA, Kurganov BI, Copper chaperones, intracellular copper trafficking proteins. Function, structure, and mechanism of action. Biochem Mosc, 2003, 68(8), 827–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hua H, Günter V, Georgiev O. Distorted copper homeostasiswith decreased sensitivity to cisplatin upon chaperone Atox1 deletion in Drosophila. Biometals 2011;24:445–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Giampietro R, Spinelli F, Contino M, Colabufo NA, The pivotal role of copper in neurodegeneration: a new strategy for the therapy of neurodegenerative disorders, Mol Pharm ,2018, 15(3), 808–820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Butterfield D.A., Reed T., Newman S. F., Sultana R., Roles of amyloid β-peptide-associated oxidative stress and brain protein modifications in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Free Radic Bio Med, 2007, 43(5), 658–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Opazo C., Huang X., Cherny R.A. et al. , Metalloenzyme-like activity of Alzheimer’s disease β-amyloid: Cu-dependent catalytic conversion of dopamine, cholesterol, and biological reducing agents to neurotoxic H2O2, J Bio Chem, 2002, 277(43) 40302–40308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Eskici G., Axelsen P.H., Copper and oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease, Biochem, 2012, 51(32), 6289–6311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hureau C. and Faller P., Aβ-mediated ROS production by Cu ions: structural insights, mechanisms and relevance to Alzheimer’s disease, Biochimie, 2009, 91(10), 1212–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Barnham KJ, Masters CL, Bush AI. Neurodegenerative diseases and oxidative stress. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2004;3:205–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roussaeux CG, MacNabb LG. Oral administration of D-pencillamine causes neonatal mortality without morphological defects in CD-1 mice. J Appl Toxicol 1992;12:35–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Walshe J. Penicillamine, a new oral therapy for Wilson’s disease. Am J Med 1956;21:487–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Weigert WM, Offermanns H, Degussa PS. D-Penicillamine—production and properties. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 1975;14:330–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Winterbourn CC, Metodiewa D. Reactivity of biologically important thiol compounds with superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. Free Rad Biol Med 1999;27:322–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wadhwa S, Mumper RJ. D-penicillamine and other low molecular weight thiols: review of anticancer effects and related mechanisms. Cancer Lett 2013;337:8–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Starkebaum G, Root R. D-Penicillamine: analysis of the mechanism of copper-catalyzed hydrogen peroxide generation. J Immunol 1985;134:3371–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Spadoni F., Stefani A., Morello M., et al. Selective vulnerability of pallidal neurons in the early phases of manganese intoxication, Exp Brain Res, 2000, 135(4), 544–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yu W.R., Jiang H., Wang J., Xie J.X., Copper (Cu2+) induces degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the nigrostriatal system of rats, Neurosci Bull, 2008, 24(2), 73–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hosamani R. Muralidhara, Neuroprotective efficacy of Bacopa monnieri against rotenone induced oxidative stress and neurotoxicity in Drosophila melanogaster. Neurotoxicology 2009;30:977–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ortega-Arellano HF, Jimenez-Del-Rio M, Velez-Pardo C. Life span and locomotor activity modification by glucose and polyphenols in Drosophila melanogaster chronically exposed to oxidative stress-stimuli: implications in Parkinson’s disease. Neurochem Res 2011;36:1073–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dinis-Oliveira RJ, Remião F, Carmo H et al. Paraquat exposure as an etiological factor of Parkinson’s disease. Neurotoxicology 2006;27:1110–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Spivey A. Rotenone and paraquat linked to Parkinson’s disease: human exposure study supports years of animal studies. 2011;119:A259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Missirlis F., Holmberg S., Georgieva T. et al. Characterization of mitochondrial ferritin in Drosophila, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2006, 103(15), 5893–5898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Muckenthaler M., Gunkel N., Frishman D., et al. Iron-regulatory protein-1 (IRP-1) is highly conserved in two invertebrate species—characterization of IRP-1 homologues in Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans, Eur J Biochem, 1998, 254(2),230–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Au C., Benedetto A., Aschner M., Manganese transport in eukaryotes: the role of DMT1. Neurotoxicology, 2008, 29(4), 569–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Burke R., Commons E., Camakaris J, Expression and localisation of the essential copper transporter DmATP7 in Drosophila neuronal and intestinal tissues, Int J Biochem Cell Biol, 2008, 40(9),1850–1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bahadorani S., Bahadorani P., Marcon E., et al. A Drosophila model of Menkes disease reveals a role for DmATP7 in copper absorption and neurodevelopment, Dis Model Mech 2010, 3(1–2), 884–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Halmenschelager PT, Rocha JBT. Biochemical CuSO4Toxicity in Drosophila melanogaster depends on sex and developmental stage of exposure. Biol Trace Elem Res 2018;189(2):574–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Abolaji AO, Fasae KD, Iwezor CE et al. Curcumin attenuates copper-induced oxidative stress and neurotoxicity in Drosophila melanogaster. Toxicol Rep 2020;7:261–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bonilla-Ramirez L, Jimenez-Del-Rio M, Velez-Pardo C. Acute and chronic metal exposure impairs locomotion activity in Drosophila melanogaster: a model to study parkinsonism. Biometals 2011;24:1045–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Farombi EO, Abolaji AO, Farombi TH et al. Garcina kola seeds biflavonoid fraction (Kolaviron), increases longevity and attenuates rotenone induced toxicity in Drosophila melanogaster. Pestic Biochem Physiol 2018;145:39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem 1951;193:265–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ellman GL. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch Biochem Biophys 1959;82:70–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Habig WH, Jakoby WB. Assays for differentiation of glutathione-S-transferases. Methods Enzymol 1981;77:398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Aebi H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol 1984;105:121–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ellman GL, Courtney KD, Andres V, Feathers-Stone RM. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem Pharmacol 1961;7:88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wolff SP. Ferrous ion oxidation in presence of ferric ion indicator xylenol orange for measurement of hydroperoxides. Methods Enzymol 1994;233:182–9. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Coulom H., Birman S., Chronic exposure to rotenone models sporadic Parkinson’s disease in Drosophila melanogaster, J Neurosci 2004, 24(48),10993–10998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chaudhuri A., Bowling K., Funderburk C. et al. Interaction of genetic and environmental factors in a Drosophila Parkinsonism model, J Neurosci 2007, 27(10), 2457–2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Abolaji AO, Adedara AO, Adie MA et al. Resveratrol prolongs lifespan and improves 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridineinduced oxidative damage and behavioural deficits in Drosophila melanogaster. Biochem Bioph Resear Comm 2018;1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Desai V., Kaler S.G., Role of copper in human neurological disorders, Am J Clin Nutr 2008, 88(3), 855–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kaler S.G., ATP 7A-related copper transport diseases emerging concepts and future trends, Nat Rev Neurol 2011, 7(1), 15–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Southon A., Palstra N., Veldhuis N., et al. Conservation of copper-transporting P(IB)-type ATPase function, Biometals, 2010, 23(4), 681–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tiklova K.´, Senti K.A., Wang S. et al.Epithelial septate junction assembly relies on melanotransferrin iron binding and endocytosis in Drosophila, Nat Cell Biol 2010, 12(11), 1071–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Squitti R., Rossini P. M., Cassetta E., et al. D-penicillamine reduces serum oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease patients, Eur J Clin Investig 2002, 32, 51–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Grazyna G, Agata K, Adam P et al. Treatment with D-penicillamine or zinc sulphate affects copper metabolism and improves but not normalizes antioxidant capacity parameters in Wilson disease. Biometals 2014;27:207–15. doi: 10.1007/s10534-013-9694-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Quamar S, Kumar J, Mishra A, Flora SJS. Oxidative stress and neurobehavioural changes in rats following copper exposure and their response to MiADMSA and D-penicillamine. Toxicol Res Appl 2019;3:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kachur AV, Koch CJ, Biaglow JE. Mechanism of copper-catalyzed autoxidation of cysteine. Free Rad Biol Med 1999;31:23–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ghezzi P., Oxidoreduction of protein thiols in redox regulation, Biochem Soc Trans, 2005, 33(6), 1378–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hatem E, Veronique B, Michele D et al. Glutathione is essential to preserve nuclear function and cell survival under oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med 2014;67:103–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Speisky H, Go’mez M, Burgos-Bravo F et al. Generation of superoxide radicals by copper-glutathione complexes: redox consequences associated with their interaction with reduced glutathione. Bioorg Med Chem 2009;17:1803–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Haverroth GMB, Welang C, Mocelin RN et al. Copper acutely impairs behavioral function and muscle acetylcholinesterase activity in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2015;122:440–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lima D, Roque GM, De Almeida EA. In vitro and in vivo inhibition of acetylcholinesterase and carboxylesterase by metals in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Mar Environ Res 2013;91:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Nunes B. The use of cholinesterases in ecotoxicology. Rev Environ Contam Toxicol 2011;212:29–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]