Abstract

Introduction

This retrospective cohort study evaluated the impact of endometriosis on the risks of work loss events and salary/growth over a 5-year period.

Methods

Women aged 18–49 years with ≥ 1 endometriosis diagnosis were identified in a claims database and matched 1:1 to women without endometriosis (controls). The index date was the first endometriosis diagnosis date (endometriosis cohort) or a random date during the period of continuous eligibility (controls). Baseline characteristics were compared between cohorts descriptively. Average annual salaries were compared over the 5 years post-index using generalized estimating equations accounting for matching. Time-to-event analyses assessed risk of short-term disability, long-term disability, leave of absence, early retirement, and any event of leaving the workforce (Kaplan-Meier curves with log-rank tests).

Results

A total of 6851 matched pairs (mean age at index date: 38.7 years) were included in the salary growth analysis, with a subset of 1981 pairs in the risk of leaving the workforce analysis. In year 1, the endometriosis cohort had a lower average annual salary ($61,322) than controls ($64,720); salaries were lower in years 2–5 by $3697–$6600 (all p < 0.01). The endometriosis cohort experienced smaller salary growth than controls in all years, ranging from $438 vs. $1058 in year 1 to $4906 vs. $7074 in year 5 (all p < 0.05). In the Kaplan-Meier analyses, patients with endometriosis were significantly more likely than controls to leave the workforce for any reason, take a leave of absence, and use short-term disability (all log-rank tests p < 0.001). Additionally, the median number of years to each of these events was lower for the endometriosis cohort relative to the matched controls. Sensitivity analyses among patients with moderate-to-severe endometriosis and by salary brackets confirmed the primary analyses.

Conclusions

Patients with endometriosis experienced lower annual salary and salary growth, as well as higher risks of work loss events, compared with matched controls.

Electronic Supplementary Material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12325-020-01280-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Claims database analysis, Endometriosis, Gynecology, Real-world study, Salary, Workforce attrition, Women's Health

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Approximately 6.1% of women in the USA (2012) have endometriosis, which is associated with potentially painful symptoms, significant healthcare costs, work absenteeism, and decreased productivity. |

| This retrospective claims database analysis evaluated the long-term indirect costs and risks of work loss incurred by women with endometriosis compared with matched controls without endometriosis. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| Compared with controls, women with endometriosis were significantly more likely to experience any work loss event, including a leave of absence and short-term disability, as well as lower salary and salary growth in the 5 years after diagnosis. |

| This study provides real-world evidence that endometriosis is associated with a considerable indirect burden, confirmed across multiple outcomes and robust in sensitivity analyses. |

Introduction

Endometriosis is a complex gynecologic disease characterized by the presence of endometrial gland tissue and stroma outside the uterine cavity [1]. The lesions typically present in the pelvic region but can also be located in the bowel, diaphragm, and other sites, although there is a poor correlation with symptoms and the severity of disease [2]. Women with endometriosis often experience symptoms before diagnosis including menstrual or non-menstrual pelvic pain/cramping, infertility, and dyspareunia [1, 3]. In addition, women with endometriosis are at greater risk for adverse obstetric and neonatal outcomes [4, 5]. The prevalence of diagnosed endometriosis was estimated at 6.1% in the USA in 2012, or approximately 4 million women of reproductive age [1]. However, because the symptoms of endometriosis may be nonspecific, the true prevalence of endometriosis is difficult to approximate and estimates vary widely, with some studies estimating that up to six of every ten patients with the disease are undiagnosed [6].

In addition to potentially painful symptoms and significant healthcare costs [7, 8], endometriosis is associated with increased work absenteeism and decreased productivity [9]. A Danish survey study compared 610 employed patients with endometriosis with 751 control patients and reported that those with endometriosis had significantly more sick days, work disturbance due to symptoms, and lower work ability (attributed to pain and tiredness) [10]. A global, multicenter study of 1418 women (aged 18–45 years) with endometriosis reported that each woman lost an average of 10.8 h of work weekly because of lower work productivity [11]. However, treatment of symptoms can positively impact the work life of patients. A recent post-hoc analysis from the Phase 3 ELARIS I and II trials of elagolix among women (aged 18–49) with moderate-to-severe endometriosis reported that treated patients gained > 2–4 h of work per week and experienced between $1500 to > $3300 costs savings over 6 months compared with those treated with placebo [12]. However, the long-term indirect costs and risks of work loss incurred by patients with endometriosis are understudied areas of the literature.

To better understand this important question, this study assessed the longitudinal impact of endometriosis on patients’ salaries as well as the risk of leaving the workforce using a case-control study design and data from a claims database.

Methods

Data Source

Data for this study were derived from the OptumHealth Reporting and Insight claims database (Q1 1999 through Q1 2017). This database includes administrative claims for > 19.9 million privately insured individuals covered by 84 self-insured Fortune 500 companies with nationwide locations in the US. These companies have operations in a broad array of industries and job classifications (i.e., financial services, manufacturing, telecommunications, energy, and food and beverage). Medical and drug claims as well as eligibility data are available for all beneficiaries (i.e., employees, spouses, dependents, and retirees). This study used a subset of the database from 42 of the 84 companies, which provided work loss-related data for their employees (approximately 4.4 million beneficiaries), including information on short- and long-term disability, leave of absence, and early retirement. The data were de-identified and complied with the patient confidentiality requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. As a result, no institutional review board approval was required. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Study Design and Study Population

A case-control cohort design was used whereby newly diagnosed patients with endometriosis and control patients without endometriosis were selected and placed into two cohorts to help evaluate the cumulative impact of endometriosis diagnosis over time on salary growth. A second sample was created from a subset of this data containing patients with work loss data available during the baseline and study periods defined below. This sample was used to evaluate the cumulative impact of endometriosis diagnosis on the risk of leaving the workforce.

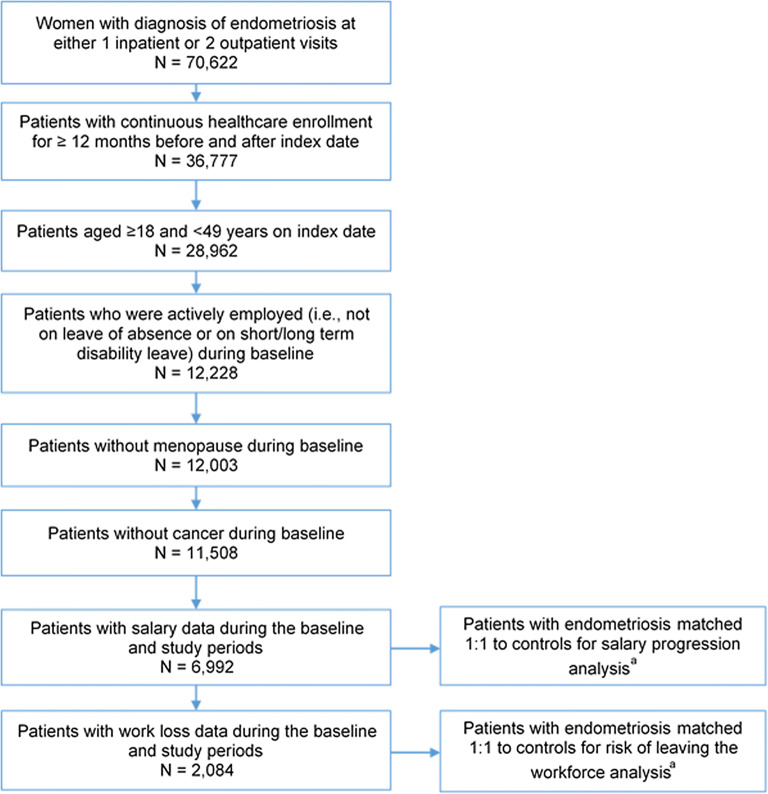

The endometriosis cohort included women with an endometriosis diagnosis [International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) code 617.X or ICD-10 code of N80.X] at either one inpatient visit or two distinct outpatient visits. The control cohort included women who did not have an endometriosis diagnosis throughout their entire claims history. Women in both cohorts were also required to have had continuous enrollment in a healthcare plan for at least 12 months before (baseline period) and after their index date, be ≥ 18 and < 49 years old at their index date, be actively employed during the baseline period and on the index date, and have salary data available during the baseline and study periods. Women with a diagnosis of menopause or cancer during the baseline period were excluded from the study population. All patients in the work loss subset were additionally required to have work loss data available during the baseline and study periods. Women with endometriosis were exactly matched 1:1 to women without endometriosis on index date year, birth year, industry type, and region (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Sample selection for patients with endometriosis and matched controls. aBoth the cohort of patients with endometriosis and the control cohort had the same reported sample size

The index date was defined as the first date of endometriosis diagnosis for the endometriosis cohort and as a randomly selected date that met the continuous healthcare enrollment criterion for the control cohort. For all patients, the study period ran from the index date to the earliest event among healthcare plan disenrollment, end of data, end of employment, patients turning 65 years old, and 5 years after the index date.

Statistical Analyses

Summary and Comparison of Baseline Characteristics

Baseline characteristics were summarized and compared between the endometriosis cohort and matched controls. Patient characteristics collected included demographics (age, region, and type of health insurance), financial status (annual salary and industry type), prior use of relevant medications, prior endometriosis-related surgeries, endometriosis-related comorbidities, and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) scores. Means and standard deviations were calculated for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages were calculated for categorical variables. Statistical comparisons were conducted using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for continuous variables and McNemar tests for dichotomous variables. For mutually exclusive categorical variables with more than two categories, statistical comparisons were conducted using Bowker's test for symmetry. A p value of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. The software SAS enterprise guide 7.1 was used for the analyses.

Comparison of Observed Annual Salary for Each Year During the 5-Year Study Period

Employer-reported annual salary was summarized and compared between cohorts for each year of the 5-year study period beginning with the index year. Annual salary for each follow-up year was calculated as the average of the monthly reported annualized salary during each follow-up year. If a patient left the work force less than a year following the index date, the available salary data before leaving the work force were annualized. Salary was adjusted for inflation to 2018 US dollars (USD) using the all-items component of the Consumer Price Index from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Summary statistics and comparisons were restricted to matched pairs that both had salary data in a given year. Unadjusted and adjusted comparisons of observed annual salary between cohorts were conducted using generalized estimating equations (GEE) with a normal distribution for annual salary, which accounted for the correlation in salary between patients with endometriosis and their matched controls. Adjusted comparisons controlled for CCI scores during the baseline period.

Comparison of Annual Salary Change from Baseline Over the Study Period

A linear model was used to compare the longitudinal trajectory of change in salary from baseline between endometriosis and control cohorts. A GEE was used to account for correlation among repeated salary measures. The variables used to match the two cohorts were adjusted for to account for the correlation between the patients with endometriosis and their matched controls. Additionally, baseline CCI and baseline salary were adjusted for in the model. An interaction term between cohort and follow-up year was used in the model to assess the statistical significance of the incremental change in annual salary over time in the two cohorts. Salary for each year during the study period was calculated as described for annual observed salary. A separate GEE model, using the same specifications as those used in the analysis of annual salary change from baseline, was also conducted comparing percent salary change from baseline between endometriosis patients and controls.

Comparison of Risk of Leaving the Workforce

Time-to-event analyses assessed risk of leaving the workforce events, including short-term disability, long-term disability, leave of absence, early retirement, and any event of leaving the workforce. For short- and long-term disability, time to event was calculated as the time from the index date to the first day of a claim for the work loss event. For leave of absence and early retirement, time to event was calculated as the time from the index date to the first day of the first month in which the patient’s employee status indicated a work loss event. However, for events of leave of absence or early retirement that took place during the index month, time to leave of absence or early retirement was calculated as the time from the index date to the last day of the index month. In part, this was because the data source only had month-level leave of absence and early retirement data. Patients without a work loss event during the study period were censored at their last day of follow-up. Risk of leaving the workforce was compared between patients with endometriosis and their matched controls for each of these five events in separate Kaplan-Meier curves using log-rank tests. Cox proportional hazards models were also used to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of each work loss event for patients with endometriosis compared with controls after adjustment for baseline CCI. The Cox models also employed robust sandwich covariance matrix estimates, which accounted for the correlation between patients with endometriosis and their matched controls.

Sensitivity Analyses

Salary and risk of leaving the workforce analyses were repeated for a subgroup of moderate-to-severe patients with endometriosis. These patients were identified by their use of a second-line drug [gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists, progestin, or danazol] any time from the beginning of the baseline period through 1 month post-index date or an endometriosis-related surgery (e.g., laparoscopy, hysterectomy, oophorectomy, and salpingectomy) any time from the index date to 1 month post-index date. Endometriosis-related surgeries were required to have an associated endometriosis diagnosis code in a medical claim on the same date.

Sensitivity analyses estimating the trajectories of salary growth by classifying patients into low and high baseline salary brackets were also conducted to consider the wide range of remuneration among patients. Using the median baseline salary from the two cohorts [median salary: $49,446 (endometriosis) and $50,361 (control)], patients were classified into low (under the median) and high (above the median) baseline salary subgroups. Salary growth analyses using the GEE models were repeated for both the low and high baseline salary groups to project the trajectories of salary growth over time. Model specifications were the same as those used in the primary analysis of annual salary change from baseline.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

In total, 6851 patients with endometriosis were included in the endometriosis cohort and were matched 1:1 with control patients for the analysis of salary growth over time. A subset of 1981 patients in each cohort provided data for the risk of leaving the workforce analyses. The selection of patients is illustrated in a flowchart (Fig. 1), and the baseline characteristics of both cohorts are listed in Table 1. The mean age of patients in both cohorts was 38.7 years. Compared with controls, patients with endometriosis had significantly lower average annual salary ($60,080 vs. $64,081, respectively) and higher CCI (0.16 vs. 0.12) (both p < 0.01). More patients with endometriosis used nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), opioids, and second-line therapies for endometriosis during the baseline period compared with controls. Health insurance types also varied between the cohorts.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Baseline comparison | Endometriosis cohort (N = 6851) | Control cohort (N = 6851) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age at index date (years), mean ± SD | 38.65 ± 6.51 | 38.65 ± 6.51 | – |

| Region, N (%) | – | ||

| Northeast | 831 (12.13%) | 831 (12.13%) | |

| Midwest | 1633 (23.84%) | 1633 (23.84%) | |

| South | 3255 (47.51%) | 3255 (47.51%) | |

| West | 1132 (16.52%) | 1132 (16.52%) | |

| Health insurance type, N (%) | < 0.01* | ||

| Preferred provider organization | 3882 (56.66%) | 3931 (57.38%) | |

| Point of service | 1603 (23.40%) | 1376 (20.08%) | |

| Othera | 1366 (19.94%) | 1544 (22.54%) | |

| Financial status | |||

| Annual salary (2018 USD), mean ± SD | 60,079.66 ± 54,779.4 | 64,080.65 ± 55,580.2 | < 0.01* |

| 25th percentile | 34,215.46 | 33,754.41 | |

| Median | 49,446.27 | 50,361.54 | |

| 75th percentile | 72,590.34 | 78,737.13 | |

| Industry type, N (%) | – | ||

| Manufacturing industry | 583 (8.51%) | 583 (8.51%) | |

| Service industry | 5236 (76.43%) | 5236 (76.43%) | |

| Healthcare industry | 768 (11.21%) | 768 (11.21%) | |

| Other industry | 264 (3.85%) | 264 (3.85%) | |

| Medication useb, N (%) | |||

| Combined oral contraceptives | 1378 (20.11%) | 1386 (20.23%) | 0.86 |

| NSAIDs | 2221 (32.42%) | 1393 (20.33%) | < 0.01* |

| Opioids | 3057 (44.62%) | 1784 (26.04%) | < 0.01* |

| Non-opioidsc | 179 (2.61%) | 113 (1.65%) | < 0.01* |

| Leuprolide | 213 (3.11%) | 17 (0.25%) | < 0.01* |

| GnRH agonists other than leuprolide | 3 (< 0.1%) | 0 (0.00%) | > 0.99 |

| DMPA | 149 (2.17%) | 91 (1.33%) | < 0.01* |

| Progestin other than DMPA | 837 (12.22%) | 355 (5.18%) | < 0.01* |

| Danazol | 4 (< 0.1%) | 0 (0.00%) | > 0.99 |

| Surgeries, N (%) | |||

| Laparoscopy | 209 (3.05%) | 56 (0.82%) | < 0.01* |

| Hysterectomy | 44 (0.64%) | 40 (0.58%) | 0.66 |

| Laparotomy | 24 (0.35%) | 5 (< 0.1%) | < 0.01* |

| Oophorectomy | 11 (0.16%) | 1 (< 0.1%) | < 0.01* |

| Salpingectomy | 3 (< 0.1%) | 2 (< 0.1%) | 0.65 |

| Other surgeries | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) | > 0.99 |

| Conditions and symptoms, N (%) | |||

| Abdominal pain | 2247 (32.80%) | 781 (11.40%) | < 0.01* |

| Pelvic pain | 2480 (36.20%) | 325 (4.74%) | < 0.01* |

| Dysmenorrhea | 1282 (18.71%) | 109 (1.59%) | < 0.01* |

| Excessive or frequent menstruationd | 2171 (31.69%) | 300 (4.38%) | < 0.01* |

| Infertility | 615 (8.98%) | 129 (1.88%) | < 0.01* |

| Ovarian cysts | 1774 (25.89%) | 206 (3.01%) | < 0.01* |

| Vaginitis | 748 (10.92%) | 485 (7.08%) | < 0.01* |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)e, mean ± SD | 0.16 ± 0.49 | 0.12 ± 0.40 | < 0.01* |

DMPA depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate, GnRH gonadotropin-releasing hormone, NSAIDs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, SD standard deviation, USD United States dollars

*p < 0.05

a"Other" health insurance types included indemnity, health maintenance organization, independent practice organization, lock-in, exclusive provider organization, pharmacy network plans, unknown, and no coverage

bUse of relevant medications was identified by the General Product Identifier or Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code associated with a medication

cAll non-opioid drugs listed are also non-narcotics

dExcessive or frequent menstruation included menometrorrhagia, menorrhagia, and metrorrhagia

eThe 17 conditions included in the CCI were identified using International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, versions 9 or 10 (ICD-9 and ICD-10) diagnosis codes reported by Quan et al. [16]

Observed Annual Salary and Salary Changes from Baseline Over a 5-Year Follow-Up

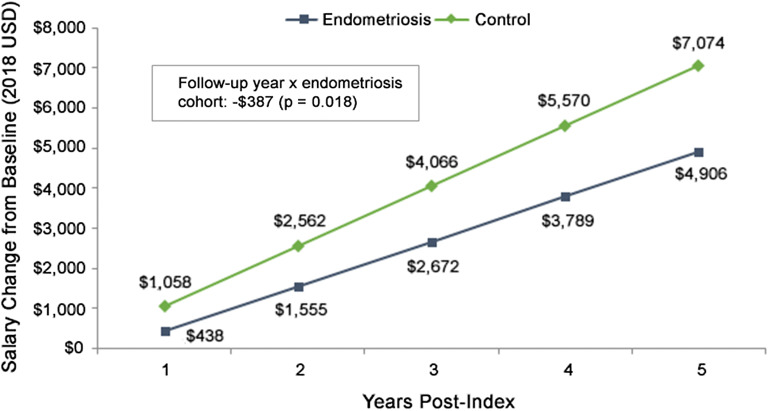

Among the matched pairs in the salary analyses, patients with endometriosis had significantly lower observed annual salary than controls in each of the 5 years after the index date (Table 2). This difference in observed annual salary between cohorts increased in each subsequent year after year 1 from $3398 in year 1 to $6600 in year 5 (p for all years < 0.05). These differences remained statistically significant after controlling for baseline CCI. With regard to the longitudinal model that assessed salary growth over time, the results showed that patients with endometriosis had significantly smaller salary growth than controls over the 5-year follow-up period after controlling for baseline CCI, salary, and the variables used to match cohorts (Fig. 2). In the first year after endometriosis diagnosis, salary growth for the endometriosis cohort was $620 less than the control cohort. On average, the salary growth for endometriosis cohort was $387 less per year compared with the control cohort (p = 0.018). After 5 years, cumulative salary growth for the endometriosis cohort was $2168 less than for controls ($4906 vs. $7074, respectively). In addition, in the analysis of percent change in salary growth from baseline during the 5-year follow-up period, the endometriosis cohort experienced a significantly lower growth rate relative to that of controls (p = 0.023). The largest difference in the cumulative percent salary growth was seen after 5 years (endometriosis cohort: 10% vs. control cohort: 14%, Supplemental Figure 1), consistent with the trend observed in the salary growth analysis.

Table 2.

Observed annual salary during the baseline and study periods

| Observed annual salary (2018 USD), mean ± SD | Mean difference in salary | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endometriosis cohort [A] | Control cohort [B] | [A] − [B] | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |

| Baseline | $60,080 ± 54,779 | $64,081 ± 55,580 | − $4001 | < 0.001* | < 0.001* |

| Year 1 | $61,322 ± 50,061 | $64,720 ± 48,785 | − $3398 | < 0.001* | < 0.001* |

| Year 2 | $62,527 ± 41,343 | $66,224 ± 48,946 | − $3697 | < 0.001* | < 0.001* |

| Year 3 | $64,504 ± 41,767 | $69,603 ± 49,575 | − $5099 | < 0.001* | < 0.001* |

| Year 4 | $66,571 ± 45,434 | $72,857 ± 53,003 | − $6286 | < 0.001* | < 0.001* |

| Year 5 | $68,781 ± 46,055 | $75,381 ± 59,315 | − $6600 | 0.007* | 0.009* |

SD standard deviation, USD United States dollars

*p < 0.05

Fig. 2.

Regression-adjusted salary change from baseline for patients with endometriosis vs. matched controls. USD United States dollars

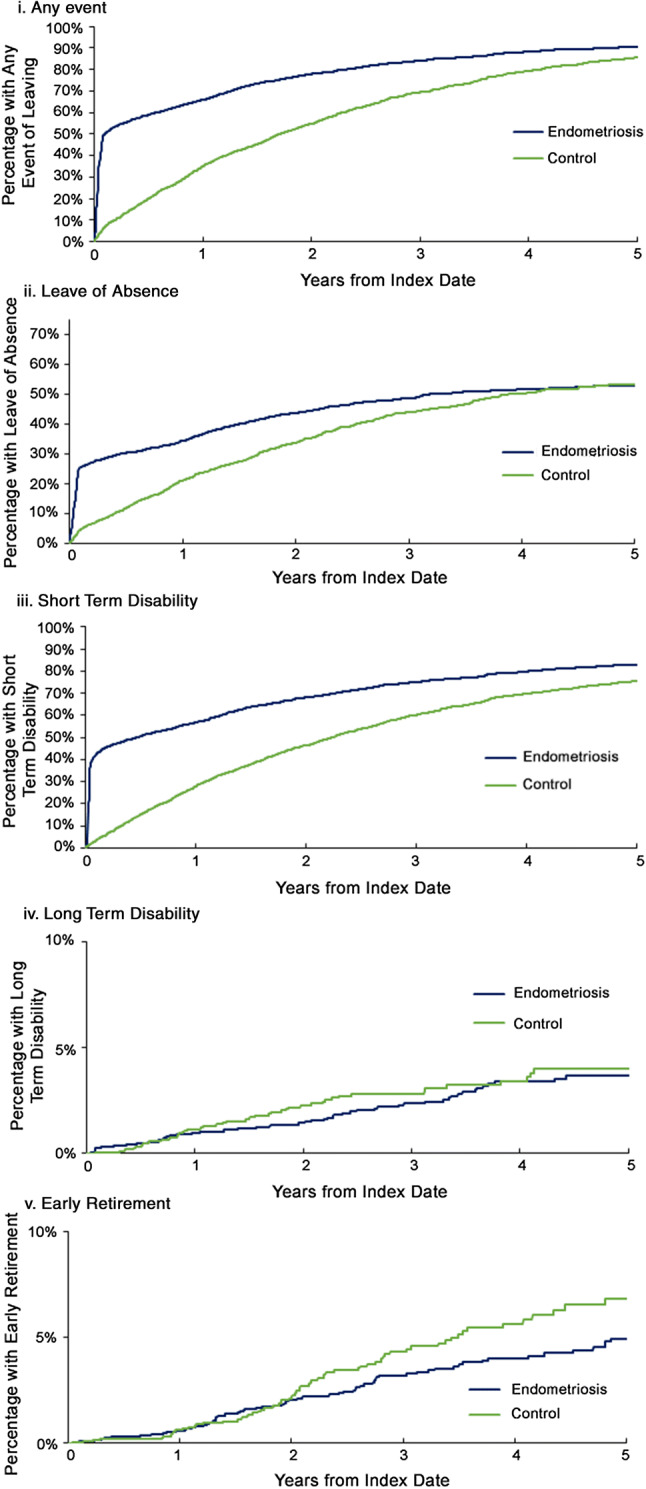

Risk of Leaving the Workforce

Among the matched pairs in the risk of leaving the workforce analyses, the median follow-up times were 3.7 years for the endometriosis cohort and 2.5 years for the control cohort. In the Kaplan-Meier analyses, patients with endometriosis were significantly more likely than controls to leave the workforce for any reason (Fig. 3a), take a leave of absence (Fig. 3b), and use short-term disability (Fig. 3c) (all log rank tests p < 0.001). Additionally, the median number of years to each of those events was lower for the endometriosis cohort relative to the matched controls. However, for these three outcomes, the differences in event rates between cohorts were highest during the first year, particularly immediately after diagnosis, and subsequently declined over time (Fig. 3a–c).

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier analysis for risk of leaving the workforce in the endometriosis and control cohorts

Both cohorts had few long-term disability (Fig. 3d) and early retirement (Fig. 3e) events. Similar rates of long-term disability over time were observed for the cohorts. The rates for a long-term disability event among patients with endometriosis vs. controls were 1.0% vs. 1.1%, respectively, in the first year, 1.4% vs. 2.3% in the second year, 2.4% vs. 2.8% in the third year, 3.4% vs. 3.4% in the fourth year, and 3.6% vs. 4.0% in the fifth year. Starting in the second year, lower rates of early retirement were observed in patients with endometriosis relative to controls, and the differences in these rates increased over time. The rates of early retirement for patients with endometriosis vs controls were 2.0% vs. 2.1% in the second year, 3.2% vs. 4.3% in the third year, 4.0% vs. 5.6% in the fourth year, and 4.9% vs. 6.8% in the fifth year.

The results of the multivariate Cox models, which adjusted for baseline CCI, were consistent with the unadjusted Kaplan-Meier analyses (Table 3). Compared with control patients, patients with endometriosis were significantly more likely to experience any work loss event [HR (95% CI) 2.0 (1.9–2.2)], including a leave of absence [1.3 (1.2–1.5)] and short-term disability [1.9 (1.7–2.0)] (all p < 0.001). There were no significant differences in rates of long-term disability (p = 0.383) or early retirement (p = 0.06) between the cohorts.

Table 3.

Cox proportional hazard models for risk of leaving the workforce associated with endometriosis

| Events | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Any event | 2.01 (1.87, 2.16) | < 0.001* |

| Leave of absence | 1.32 (1.20, 1.45) | < 0.001* |

| Short-term disability | 1.88 (1.74, 2.03) | < 0.001* |

| Long-term disabilitya | 0.84 (0.58, 1.24) | 0.383 |

| Early retirement | 0.75 (0.55, 1.01) | 0.060 |

CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio

*p < 0.05

aThe proportional hazards model assumption was violated for this outcome

Sensitivity Analyses

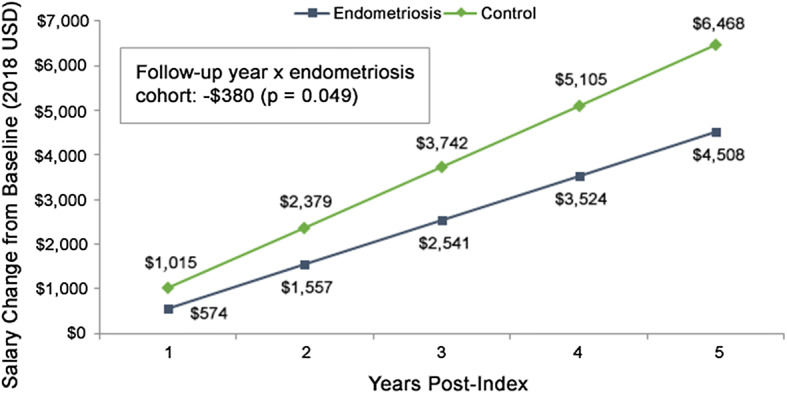

There were 5093 patients identified as having moderate-to-severe endometriosis, who were included in the sensitivity analyses. Consistent with the findings in the primary analyses of all patients with endometriosis, patients with moderate-to-severe endometriosis had lower annual salary (p for all years < 0.05) and slower salary growth compared with their matched controls (Table 4 and Fig. 4). On average, the salary growth for the moderate-to-severe endometriosis cohort was $380 less per year compared with controls (p = 0.049) (Fig. 4).

Table 4.

Observed annual salary for patients with moderate-to-severe endometriosis and controls during the baseline and study periods

| Observed annual salary (2018 USD), mean ± SD | Mean difference in salary | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endometriosis cohort [A] | Control cohort [B] | [A] − [B] | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |

| Baseline | $57,865 ± 46,462 | $62,746 ± 54,654 | -− $4881 | < 0.001* | < 0.001* |

| Year 1 | $59,316 ± 45,893 | $63,277 ± 46,229 | − $3961 | < 0.001* | < 0.001* |

| Year 2 | $60,195 ± 38,799 | $64,771 ± 47,191 | − $4576 | < 0.001* | < 0.001* |

| Year 3 | $61,971 ± 39,363 | $67,824 ± 47,131 | − $5853 | < 0.001* | < 0.001* |

| Year 4 | $63,375 ± 42,507 | $70,468 ± 49,168 | − $7093 | < 0.001* | < 0.001* |

| Year 5 | $66,768 ± 44,825 | $73,428 ± 53,528 | − $6660 | 0.014* | 0.018* |

SD standard deviation, USD United States dollars

*p < 0.05

Fig. 4.

Regression-adjusted salary change from baseline for patients with moderate-to-severe endometriosis vs. matched controls. USD United States dollars

Similarly, patients with moderate-to-severe endometriosis were more likely to leave the workforce compared with their matched controls throughout the baseline and 5-year study periods (Table 5). The results of the multivariate Cox models showed that patients with moderate-to-severe endometriosis were significantly more likely to experience any work loss event [HR (95% CI) 2.3 (2.1–2.4)], including a leave of absence [1.4 (1.2–1.5)] and short-term disability [2.1 (1.9–2.3)] (all p < 0.001) (Table 5). Similar to the main analysis, there were no significant differences in rates of long-term disability (p = 0.591) or early retirement (p = 0.107) between the cohorts.

Table 5.

Cox proportional hazard models for risk of leaving the workforce associated with moderate-to-severe endometriosis

| Events | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Any event | 2.25 (2.07, 2.44) | < 0.001* |

| Leave of absence | 1.38 (1.24, 1.53) | < 0.001* |

| Short-term disability | 2.08 (1.91, 2.27) | < 0.001* |

| Long-term disabilitya | 0.89 (0.57, 1.38) | 0.591 |

| Early retirement | 0.77 (0.57, 1.06) | 0.107 |

CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio

*p < 0.05

aThe proportional hazards model assumption was violated for this outcome

In the analysis of low and high baseline salary groups (N = 3425 and 3426 per salary groups, respectively), a smaller salary growth was observed among patients with endometriosis compared with controls in both groups. However, the differences in growth were under the threshold for significance [p = 0.07 (low), Supplemental Figure 2; p = 0.066 (high), Supplemental Figure 3].

Discussion

Endometriosis affects women of reproductive age both physically and mentally, and, as such, the societal burden of this disease is expected to be substantial. At present, the long-term burden of endometriosis on the careers and incomes of patients has not been well characterized in the published literature. To address this knowledge gap, the current study assessed the longitudinal impact of endometriosis on patients’ salary growth and risk of leaving the workforce, covering a 5-year period, using real-world data. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to comprehensively assess the long-term indirect burden of privately insured women with endometriosis in the US.

Various components of the indirect burden of endometriosis were assessed in this study, including salary, salary growth, and risk of leaving the workforce from the perspective of newly diagnosed patients. Both matching and adjusted analyses were used to mitigate the differences between the endometriosis patients and their matched controls. While this study matched patients on several characteristics to ensure that comparisons were made among cohorts with balanced baseline characteristics, patients with endometriosis still had lower average annual salary (by about $4000), higher relevant medication use, and a higher CCI compared with controls at baseline. This suggests that the impact of endometriosis could have preceded a formal diagnosis, similar to observations by a claims database analysis of women with endometriosis conducted by Fuldeore et al. [13]. That study reported that annual healthcare utilization and costs were significantly higher among women with endometriosis compared with matched controls in the year before and 5 years after a formal diagnosis, and were most pronounced in the first year ($13,199 vs. $3747, respectively).

Thus, the financial burden of endometriosis is long-lasting and may be particularly impactful in terms of limiting salary growth. The present results indicated that patients with endometriosis had significantly lower salary, experienced slower salary growth, and were more likely to leave the workforce than matched controls. In addition, patients with endometriosis were more likely to take a leave of absence and use short-term disability soon after diagnosis than matched controls, which is likely partially related to having endometriosis-related surgeries. The results of the sensitivity analyses among patients with moderate-to-severe endometriosis were consistent with these findings from the primary analyses and showed a slightly larger effect size than that of the entire endometriosis cohort. This suggests that the impact of endometriosis on the risk of work loss may be more profound among those with more severe disease. While patients with endometriosis were more likely than controls to leave the workforce for any reason, fewer experienced early retirement than controls although the difference was not statistically significant. This may be related to the financial burden incurred by the increasing medical costs for endometriosis therapies and reduced salary in patients with endometriosis compared with their matched controls. It may also be related to the need to maintain health insurance, as 56% of Americans receive health insurance through their employer [14]. Notably, the control cohort, which consisted of women of reproductive age, exhibited higher rates of short-term disability and leaves of absence than the general population. These high rates may be attributable to pregnancy-related leave, although the database did not have information related to the reason for the leaves. When separating the cohort by high and low salary brackets (based on the median salary at baseline), the same trend of lower salary growth was observed for patients with endometriosis. However, the results were not significant likely because of the lower numbers of patients analyzed.

Very few published analyses have assessed the impact of endometriosis on patients’ work lives. A 2016 systematic literature review of the economic impact of endometriosis identified five studies assessing endometriosis-related indirect costs due to absenteeism and loss of productivity within 12–24 months after being diagnosed with endometriosis [15]. Endometriosis-related absenteeism and loss of work productivity is a common metric used to quantify the related indirect costs. However, the findings were variable because of a lack of consensus on the definitions of indirect costs, the components to be considered in the estimates, the reliance on patient recall, and the variable valuation of productivity. No study in that literature review reported on the long-term burden of endometriosis in terms of annual salary and salary growth. A retrospective cohort study published in 2018 that evaluated the economic burden of endometriosis in the US found that two-thirds of patients underwent an endometriosis-related surgical procedure within the first 12 months after being diagnosed [7]. This is consistent with the Kaplan-Meier results of this study, which showed a rapid, increasing rate of leave of absence and short-term disability use within the first month post-index (post-diagnosis).

Limitations

This study is subject to limitations, some of which are common to observational studies based on healthcare claims data such as data omissions or coding errors. For instance, it is possible some patients had missing income values in the data despite being actively employed. The decision to apply an age restriction and exclude patients with a diagnosis of menopause at baseline aimed to exclude individuals that experienced menopause before the index date. This is because symptoms of endometriosis diminish after menopause. However, as the ICD codes used to identify these patients only capture menopause-related symptoms, not all patients reaching menopause would be excluded. As such, the inclusion of such patients may reduce the estimated indirect burden for the endometriosis cohort relative to their matched controls.

Additionally, because women employed by small- and medium-sized enterprises or insured by public health insurance plans were not captured in the current study, its generalizability beyond the study population may be limited. This too is a common limitation to observational studies relying on healthcare claims data in the US given the splintered nature of the country’s healthcare insurance networks. Finally, the median follow-up times were 3.7 and 2.5 years for the endometriosis control cohorts, respectively. It is unknown whether this difference between follow-up times is due to random chance or a specific reason (i.e., patients with endometriosis staying in the workforce longer for insurance needs).

Conclusions

This study provides real-world evidence that endometriosis is associated with a considerable indirect burden including lower annual salary, smaller salary growth, and higher risk of leaving the workforce. A more acute indirect burden was found among patients with moderate-to-severe endometriosis compared with the overall patient population with endometriosis. The consistent results across multiple indirect burden outcomes strengthened the study findings and depicted a clear sense of the overall indirect burden of endometriosis on patients’ professional lives. As endometriosis may impact the life course of patients and have long-lasting effects, future studies are needed on the associated indirect costs of leaving the workforce and the impact of treatments for endometriosis on the risk of leaving the workforce.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Sponsorship for this study and the Rapid Service Fee were funded by AbbVie, Inc. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. This study was funded by AbbVie Inc. AbbVie sponsored the study; contributed to the design; participated in collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; and in writing, reviewing, and approval of the final version.

Editorial Assistance

Editorial assistance in the preparation of this article was provided by Shelley Batts, PhD, an employee of Analysis Group, Inc. Support for this assistance was provided by AbbVie, Inc. The authors would also like to thank Christopher Carley and Maya Mahin from Analysis Group, Inc. for analytical support.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Hongbo Yang, Jessie Wang, and Jonathan Freimark are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., which has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Inc. Ahmed M. Soliman is an employee of AbbVie, Inc., and owns stock/options. Stephanie J. Estes is a paid consultant for AbbVie and has also provided research support to AbbVie, Obseva, and Ferring Pharmaceuticals.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The data were de-identified and complied with the patient confidentiality requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. As a result, no institutional review board approval was required. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to data agreements with the claims database provider.

Footnotes

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11872167.

References

- 1.Fuldeore MJ, Soliman AM. Prevalence and symptomatic burden of diagnosed endometriosis in the United States: national estimates from a cross-sectional survey of 59,411 women. Gynecol Obstet Investig. 2017;82(5):453–461. doi: 10.1159/000452660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agarwal SK, Chapron C, Giudice LC, Laufer MR, Leyland N, Missmer SA, et al. Clinical diagnosis of endometriosis: a call to action. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(4):354. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor HS, Giudice LC, Lessey BA, Abrao MS, Kotarski J, Archer DF, et al. Treatment of endometriosis-associated pain with elagolix, an oral GnRH antagonist. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):28–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1700089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zullo F, Spagnolo E, Saccone G, Acunzo M, Xodo S, Ceccaroni M, et al. Endometriosis and obstetrics complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(4):667–725. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen I, Lalani S, Xie RH, Shen M, Singh SS, Wen SW. Association between surgically diagnosed endometriosis and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Fertil Steril. 2018;109(1):142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morassutto C, Monasta L, Ricci G, Barbone F, Ronfani L. Incidence and estimated prevalence of endometriosis and adenomyosis in northeast Italy: a data linkage study. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(4):e0154227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soliman AM, Surrey E, Bonafede M, Nelson JK, Castelli-Haley J. Real-world evaluation of direct and indirect economic burden among endometriosis patients in the United States. Adv Ther. 2018;35(3):408–423. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0667-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao X, Outley J, Botteman M, Spalding J, Simon JA, Pashos CL. Economic burden of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(6):1561–1572. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soliman AM, Coyne KS, Gries KS, Castelli-Haley J, Snabes MC, Surrey ES. The effect of endometriosis symptoms on absenteeism and presenteeism in the workplace and at home. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(7):745–754. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.7.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansen KE, Kesmodel US, Baldursson EB, Schultz R, Forman A. The influence of endometriosis-related symptoms on work life and work ability: a study of Danish endometriosis patients in employment. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;169(2):331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nnoaham KE, Hummelshoj L, Webster P, d'Hooghe T, de Cicco Nardone F, de Cicco Nardone C, et al. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: a multicenter study across ten countries. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(2):366–373. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.05.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pokrzywinski RM, Soliman AM, Chen J, Snabes M, Diamond MP, Surrey E, et al. Impact of elagolix on work loss due to endometriosis-associated pain: estimates based on the results of two phase III clinical trials. Fertil Steril. 2019;112(3):545–551. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuldeore M, Yang H, Du EX, Soliman AM, Wu EQ, Winkel C. Healthcare utilization and costs in women diagnosed with endometriosis before and after diagnosis: a longitudinal analysis of claims databases. Fertil Steril. 2015;103(1):163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.United States Census Bureau. Health insurance coverage in the United States: 2017. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2018/demo/p60-264.html. Accessed 16 Oct 2019.

- 15.Soliman AM, Yang H, Du EX, Kelley C, Winkel C. The direct and indirect costs associated with endometriosis: a systematic literature review. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(4):712–722. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi JC, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130–1139. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to data agreements with the claims database provider.