Summary box.

The COVID-19 outbreak among migrant workers in Singapore has publicly revealed their health disparities compared with the general population.

Market system changes modify interactions between the supporting functions and rules of health markets for the long-term inclusion of vulnerable populations in the health market.

Novel market system changes in the delivery and payment of migrant workers’ healthcare can facilitate their long-term inclusion in the health market.

The new-found stakeholders’ interest in migrant workers’ welfare and public solidarity emerging from the COVID-19 outbreak could be aligned and harnessed such that private healthcare providers are engaged to supply increased postpandemic demand for healthcare, migrant workers are empowered to participate in the health market, and donor and migrant resources are mobilised to sustain affordable services.

Continued stakeholder discussion of the strategies introduced in this paper may bring us a step closer to achieving health equity for migrant workers in Singapore and possibly the Southeast Asian region.

Introduction

The COVID-19 outbreak among migrant workers in Singapore has revealed the health disparities of migrant workers due to suboptimal living conditions and poor access to ambulatory healthcare. This has given Singapore the impetus to start discussions on migrant workers’ health concerns so that they will no longer be ignored. We propose consideration of a novel postpandemic health services delivery and financing strategy that aligns the interests of migrant workers and stakeholders, including the government, healthcare providers (HCPs) and the public to bring about a systemic change in Singapore’s health market for migrant workers.1

Health disparities of Singapore’s migrant workers

Migrant workers have existed on the periphery of Singapore society in terms of living conditions and access to Singapore’s high standards of healthcare. Up till March 2020, Singapore was praised internationally for its response to the COVID-19 pandemic.2 The outbreak control measures implemented then were focused on the general population. Subsequently, alarming rates of infection among dormitory-dwelling migrant workers, mainly originating from Bangladesh, India, China and Myanmar, led to Singapore having one of the largest numbers of reported cases in Southeast Asia. In June 2020, dormitory-dwelling migrant workers accounted for 94% of infections but only 6% of the population at risk.3

This pandemic highlights the determinants of poor health among migrant workers: crammed living environments incompatible with social distancing, language barriers resulting in discriminate care and limited access to health information, an aversion to seeking medical treatment when symptomatic due to fear of losing jobs or wages, and expensive ambulatory healthcare not covered by existing insurance.4 Although it is mandatory for employers to purchase healthcare insurance for migrant workers that assures coverage of SGD15 000 (US$10 500) per year, this is for inpatient expenditure only.5 There is variable compliance of employers in honouring their responsibility or allowing a right to sick leave. Up to 27% and 8% of migrant workers have reported withholding and deducting of daily wages, respectively, when ill despite receiving a medical certificate from a licensed doctor.4

The need for market systems changes

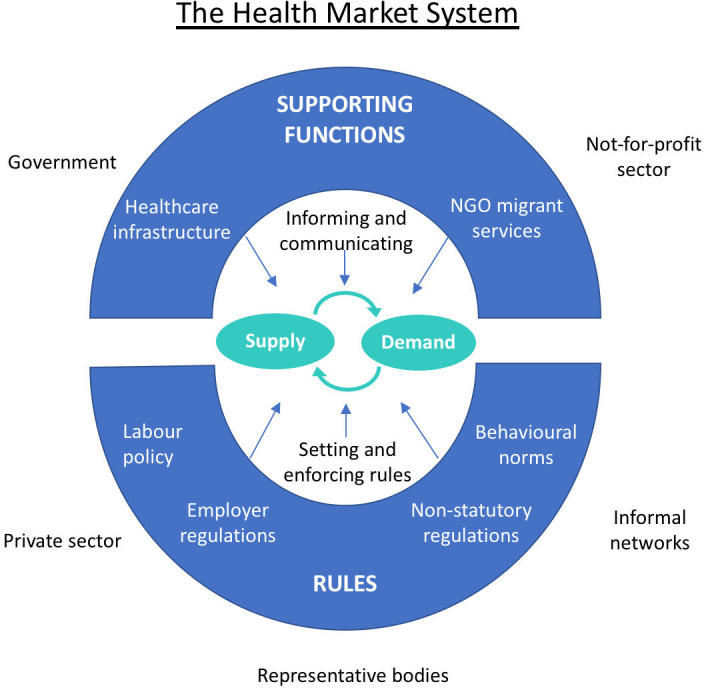

Extraordinary government resources have been deployed in this pandemic. Medical teams are sent to migrant worker facilities to triage and actively test for COVID-19 infection. All Singaporeans and migrant workers who tested positive are admitted for free-of-charge treatment. Those who are clinically stable receive medical care in rapidly repurposed facilities. Government subsidies are given to employers to continue paying wages throughout the crisis. However, there has been little public discussion on the allocation of resources for migrant workers’ health postpandemic. Public financing of migrant workers’ healthcare is expectedly constrained after four government stimulus packages worth SGD93 billion. For standard healthcare to be accessible to migrant workers postpandemic, we suggest market system changes in the delivery and payment of migrant workers’ healthcare to facilitate their long-term inclusion in the healthcare market.1 6 Market system changes modify interactions between the supporting functions and rules of health markets (figure 1).1 New migrant worker healthcare policy that supports the innovative engagement of migrant workers, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and private HCPs with a novel health financing mechanism may stimulate the desired change in the behaviour of market stakeholders for the lasting benefit of migrant workers in Singapore.1 6

Figure 1.

A diagram of the health market system (adapted from The Springfield Centre[1]).

Innovative market systems changes

Engaging private HCPs to meet the increasing demand for migrant workers’ healthcare

The demand for regular migrant worker-friendly outpatient care for chronic diseases is expected to increase. Recent admissions of migrant workers for COVID-19 have uncovered previously undiagnosed chronic diseases, including hypertension and diabetes mellitus. Local NGOs, such as HealthServe, or a selected few private for-profit general practitioner (GP) clinics are preferred by migrant workers to public polyclinics as these HCPs speak migrant workers’ native languages. Also, NGOs and GPs charge lower user fees relative to public polyclinics where migrant workers, as non-locals, do not enjoy subsidised rates. However, NGOs’ ability to sustainably provide care for a large population of migrant workers is limited by low user fees and its dependence on volunteers.

Social franchising, operated by NGOs through the contracting of private HCPs for social goals, is an efficient and effective way to increase the supply of healthcare services for migrant workers.7 Reputable NGOs with oversight over the dynamic health service demands are in an ideal position to contract existing private HCPs to facilitate rapid scaling up of service delivery points. Private HCPs have greater flexibility in lowering fees for migrant workers and higher capacity to provide more services—2200 GP clinics (vs 20 polyclinics) provide 80% of primary care.8 This is an opportunity for clinics to distinguish themselves from the competition or develop their corporate social responsibility portfolio.

Empowering migrant workers to participate in the healthcare market

This pandemic has exacerbated information asymmetry for migrant workers living in Singapore. It was previously reported that only 61% of migrant workers were aware of their mandatory inpatient health insurance and 32% informed in their native language.4 Now, they are keen to maintain health and resume work but fear being repatriated on short notice. They face uncertainty regarding their accommodation, job and health status with the ongoing pandemic.

Migrant workers’ access to important health information and their health literacy can be improved with new manpower regulations that mandate translated communications aids and government–employer–NGO collaboration. Focus group discussions, and health knowledge, attitudes and perspective surveys that characterise determinants of health-seeking behaviour and willingness-to-pay for health, can be organised to determine appropriate community health interventions to educate and empower migrant workers on healthcare utilisation. Recent awareness of their vulnerability to diseases may increase their willingness-to-pay for health, including supplementary health insurance, if available and affordable.

Resource mobilisation to sustain affordable services

As migrant worker user fees are limited by low wages, alternative sources of funds are required to ensure the sustainability of care, especially for chronic diseases. Although migrant rights’ advocates aspire for a Bismarck model of insurance where employers cofinance employees’ healthcare, pressuring employers may not be to migrant workers’ benefit. Mandating employers to pay for more insurance to include outpatient care may ultimately decrease migrant workers’ take-home wages.9 In community-based health insurance (CBHI), individuals excluded from mainstream coverage pay low premiums to a pool that is supplemented by donors and receive modest but meaningful payouts. It may improve health outcomes, prevent impoverishment and promote social inclusion for migrant workers who otherwise have no access to health coverage. It mobilises funds for migrant workers’ HCPs and can be a long-term solution to finance ambulatory care of migrant workers.10–12 Although premiums need to be kept low, coverage can be kept sustainable by specifying reimbursements for outpatient primary care only, and in so doing supplement existing inpatient coverage. For CBHI to work, sufficient donor funds and the government’s endorsement are necessary.

Harnessing public solidarity

This is a good time to harness public and government support for migrant workers’ health financing due to increased public interest in migrant workers’ welfare. There was nation-wide empathy for ‘COVID-19 Case 42’, the first Bangladeshi migrant worker to contract the virus, with whom the country shared the bittersweet joy of celebrating the birth of his child while in the intensive care unit. The now common narrative that Singapore should do better for the migrant workers who build its skyscrapers, provide domestic care and work in essential services has allowed the advocacy work of established NGOs to reach a larger audience. Public outrage over the plight of migrant workers has led to an unprecedented show of support financially or in the form of donations of essential items and hot meals to quarantine facilities. Postpandemic, these contributions could be directed to finance healthcare services. Potential long-term donors include businesses that are stakeholders in the migrant worker economy, such as remittance agencies.

Given the current focus on migrant workers’ health and well-being, it should be of interest to the government to consider a form of CBHI, an integral part of which is asserting the individual’s responsibility for healthcare through regular payment of premiums. This resonates with the core value of Singapore’s health financing policy.13

Implementation concerns

As CBHI has traditionally been implemented in low or middle-income countries, implementation in Singapore requires pilot testing, close monitoring of intended and unintended consequences, evaluation and revision to mitigate inappropriate use and adverse selection.11 Insufficient subscription of migrant workers into a voluntary pooling system that may lead to adverse selection can be countered by health education, encouraging group membership and leveraging on migrant workers’ sense of solidarity. The technical design of CBHI needs to be based on studies of migrant workers’ burden of chronic disease, health behaviour, perspectives, willingness-to-pay, actuarial science and regular engagements with stakeholders. Weak quality control mechanisms in contracting private HCPs that can lead to inappropriate care, exploitation of CBHI funds and misplacement of migrant workers’ trust must be pre-empted and actively avoided.

Conclusion

We recognise it is difficult to prioritise migrant workers’ health needs and allocate resources in the face of competing national demands. Yet solutions should still be sought to uphold health equity.14 We hope this commentary serves as a catalyst for further constructive discussion and action. There is no better time than now to build momentum to garner community-wide support to change migrant worker healthcare policy. We hope that this will be the first of many steps that lead to equitable healthcare financing for migrant workers not only in Singapore but, if proven successful, also in other countries in Southeast Asia.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: OQG conceived, wrote and edited the final manuscript. AMI, JCWL and W-CC contributed to and edited the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article.

References

- 1.Centre S. The operational guide for the making markets work for the poor (M4P) approach, 2008. Available: http://www.springfieldcentre.com/publications/sp0806.pdf

- 2.News UN. ‘Working night and day’, UN health agency seeks to prevent global coronavirus crisis. Available: https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/02/1057611 [Accessed 26 Apr 2020].

- 3.Ministy of Health COVID-19 situation report. Available: https://covidsitrep.moh.gov.sg/ [Accessed 26 Apr 2020].

- 4.Ang JW, Chia C, Koh CJ, et al. Healthcare-seeking behaviour, barriers and mental health of non-domestic migrant workers in Singapore. BMJ Glob Health 2017;2:e000213. 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Manpower Medical insurance requirements for foreign worker. Available: https://www.mom.gov.sg/passes-and-permits/work-permit-for-foreign-worker/sector-specific-rules/medical-insurance [Accessed 14 Jun 2020].

- 6.Bloom G, Champion C, Lucas H, et al. Health marketes and future health systems: innovation for equity. Glob Forum Update Res Health;5:30–3. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montagu D, Goodman C, Berman P, et al. Recent trends in working with the private sector to improve basic healthcare: a review of evidence and interventions. Health Policy Plan 2016;31:1117–32. 10.1093/heapol/czw018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Commonwealth Fund Singapore. Available: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/international-health-policy-center/countries/singapore [Accessed 14 Jun 2020].

- 9.Sommers BD. Who really pays for health insurance? the incidence of employer-provided health insurance with sticky nominal wages. Int J Health Care Finance Econ 2005;5:89–118. 10.1007/s10754-005-6603-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jakab M, Krishnan C. Community involvement in health care financing: a survey of the literature on the impact, strengths and weaknesses, 2001. Available: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/852961468780563982/Community-involvement-in-health-care-financing-a-survey-of-the-literature-on-the-impact-strengths-and-weaknesses [Accessed 26 Apr 2020].

- 11.Pudpong N, Durier N, Julchoo S, et al. Assessment of a voluntary non-profit health insurance scheme for migrants along the Thai–Myanmar border: a case study of the migrant fund in Thailand. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:2581 10.3390/ijerph16142581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spiegel P, Chanis R, Trujillo A. Innovative health financing for refugees. BMC Med 2018;16:90. 10.1186/s12916-018-1068-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lim J. Myth or magic - the Singapore healthcare system, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calabresi G, Bobbitt P. Tragic choices, 1978. Available: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/books/83