Abstract

Chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder (CKD–MBD) is one of the many important complications associated with CKD and may at least partially explain the extremely high morbidity and mortality among CKD patients. The 2009 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Clinical Practice Guideline document was based on the best information available at that time and was designed not only to provide information but also to assist in decision-making. In addition to the international KDIGO Work Group, which included worldwide experts, an independent Evidence Review Team was assembled to ensure rigorous review and grading of the existing evidence. Based on the evidence from new clinical trials, an updated Clinical Practice Guideline was published in 2017. In this review, we focus on the conceptual and practical evolution of clinical guidelines (from eMinence-based medicine to eVidence-based medicine and ‘living’ guidelines), highlight some of the current important CKD–MBD-related changes, and underline the poor or extremely poor level of evidence present in those guidelines (as well as in other areas of nephrology). Finally, we emphasize the importance of individualization of treatments and shared decision-making (based on important ethical considerations and the ‘best available evidence’), which may prove useful in the face of the uncertainty over the decision whether ‘to treat’ or ‘to wait’.

Keywords: CKD, CKD–MBD, EBM, evidence-based medicine, KDIGO

INTRODUCTION

A new definition and classification of chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder (CKD–MBD) was proposed in 2005 [1] and later adopted in 2009 in a guideline publication from the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) initiative entitled ‘KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, Prevention and Treatment of CKD–MBD’ [2]. These steps constituted recognition that CKD–MBD is one of the many important complications associated with CKD. As is already well known, CKD–MBD represents a ‘systemic’ condition manifested by either one or a combination of laboratory abnormalities [calcium, phosphate, parathyroid hormone (PTH) or vitamin D metabolism], bone abnormalities (turnover, mineralization, volume, linear growth or strength) and vascular and/or other soft tissue calcifications [1–3]. By linking kidney, bone disease (evolution of the ‘old’ concept of ‘renal osteodystrophy’, now restricted to histomorphometric analysis) [1] and cardiovascular disease, the CKD–MBD complex represents an attempt to explain, at least in part, the extremely high morbidity and mortality of CKD patients [4, 5].

The 2009 KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline document was based on the best information available at that time and was designed not only to provide information but also to assist in decision-making [2]. It was not intended to define a standard of care, and it was clearly stated that ‘it should not be construed as one, nor should it be interpreted as prescribing an exclusive course of management’ [2]. The KDIGO guidelines were created as a ‘global’ initiative, and it was recognized that variations in practice would inevitably and appropriately occur as clinicians take into account the needs of individual patients, available resources and limitations unique to an institution or type of practice [2].

Not only did the international KDIGO Work Group include worldwide experts but in addition, an independent Evidence Review Team was assembled to ensure a rigorous review and appraisal of the existing evidence. Briefly, the process included refining questions, developing the literature search strategy, extracting data and critically appraising the literature, summarizing the evidence, revising the recommendation statements, and grading evidence quality and the strength of recommendations using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach [2, 6]. Therefore, each recommendation was accompanied by the strength of the recommendation and an evidence grade. Guideline statements that provided general advice or guidance (and thus were not based on systematic review) were designated as ‘not graded’. The guideline development process concluded with an external public review to ensure widespread input from patients, experts, industry and national organizations. After the initial publication [2], several national societies and/or organizations followed-up with commentaries, interpretations, updates and local adaptations [7–9]. Based on the evidence from new clinical trials, an updated Clinical Practice Guideline was published in 2017 after the Madrid 2013 KDIGO Controversies Conference determined that there was sufficient new evidence to support updating some of the previous CKD–MBD recommendations [10, 11]. This systematic update process finally resulted in 21 updated recommendations/suggestions, and several societies have already commented on this update, drawing attention to remaining critical issues and points relevant to correct interpretation [11–14] (J. V. Torregrosa et al., submitted for publication in the Spanish Society of Nephrology journal “Nefrologia”). In this review, we will examine the conceptual/practical evolution of clinical guidelines, highlight some of the important CKD–MBD-related changes and underline some ethical considerations that may prove of importance in the face of uncertainty.

EVIDENCE-BASED MEDICINE VERSUS EMINENCE-BASED MEDICINE

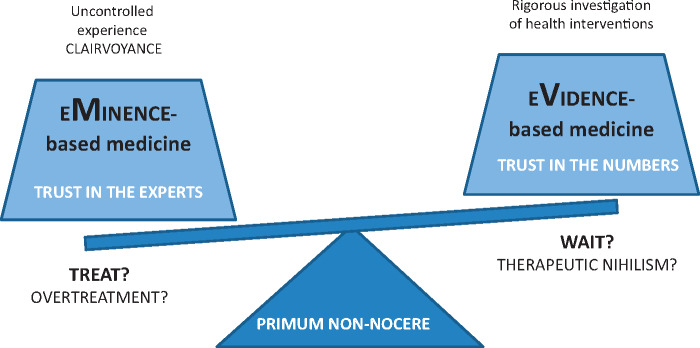

Since the time of Hippocrates, as Djulbegovic and Guyatt recently remarked in The Lancet [15], medicine has struggled to balance the uncontrolled experience of ‘healers’ with observations obtained by rigorous investigation of claims regarding the effects of health interventions. Dr Guyatt first coined the term ‘eVidence-based medicine’ (EBM) in 1991 [16], contending that although there is a role for all empirical observations, randomized controlled clinical trials (RCTs), systematic reviews and meta-analyses provide more trustworthy evidence than do unsystematic, uncontrolled observations, case reports, biological experiments and the experiences of individual clinicians or experts (‘eMinence-based medicine’ or, even worst, ‘eLoquence-based medicine’, ‘eLegance-based medicine’ or ‘vehemence-based medicine’ [17, 18]) (Figure 1). The practice of medicine should be based on systematic reviews that summarize the ‘best “available” evidence’, even though uncontrolled clinical experience and incomplete or fragmented physiological reasoning have maintained a dominant position as drivers of usual clinical practice. As a matter of fact, past inadequate research led to fatal bone marrow transplantation for women with breast cancer, prophylactic antiarrhythmic therapy in patients with myocardial infarction and the prescription of hormone replacement therapy in millions of healthy women on the basis of a hypothetical cardiovascular risk reduction [15, 19–21]. Moreover, evidence should be evaluated in totality rather than focusing on a selection of evidence that favours a particular claim. ‘Anchoring’ is a fact, i.e. once we adopt a belief regarding a concept, when confronted with new data we tend, on average, not to move as far from our accustomed position as we should [22]. If the new data are positive, then the ‘believers’ accept the data, whereas ‘non-believers’ find some reason to discredit them (e.g. because data derive from different races, countries or continents or because of variation and/or validity of different endpoints) [22]. Similarly, we tend to remember and refer to studies that confirm our views and ignore those that do not (and this is a problem when heterogeneity is common) [22]. In any case, we have to remember that well-conducted systematic reviews can summarize not only RCTs but also cohort studies, case–control studies and even case reports [15]. Nevertheless, results from different systematic reviews and meta-analyses may also differ substantially [23–28].

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of eMinence-based medicine vs eVidence-based medicine.

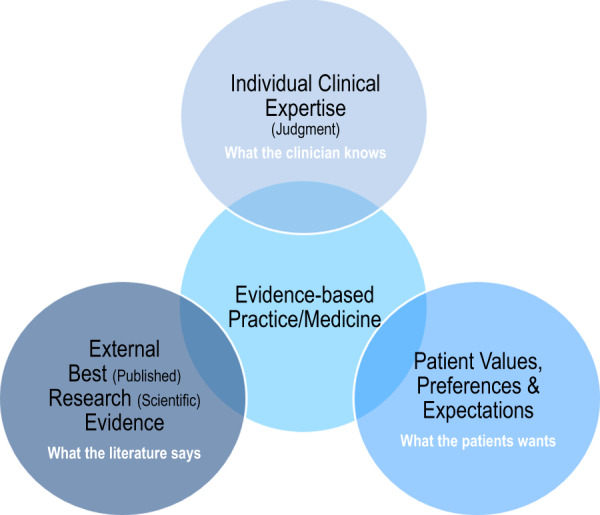

EBM integrates the best published scientific evidence (what the literature says) with clinical expertise (clinical judgment or what the clinician knows) and patient values, preferences or expectations (what the patient wants) (Figure 2). An extension of EBM methodology that is more relevant today is evidence-based clinical practice, which takes into account the healthcare setting and circumstances in which we practice. On the other hand, the GRADE system, first published in 2004 [31], provides a much more refined hierarchy of evidence, and its use in the KDIGO Clinical Practice Guidelines for CKD–MBD represented a very important step forward as compared with previous mineral metabolism guidelines [32, 33]. GRADE also addresses the process of moving from evidence to recommendations (Grade 1 = strong evidence = right for all or almost all patients; Grade 2 = weak evidence = right for most but not all patients, requiring presentation of evidence that facilitates shared decision-making) (Table 1). Note that the need to consider patients’ values and preferences is acknowledged [15]. Consequently, although not all evidence-based practices are alike [34, 35], GRADE has been adopted by >100 organizations, including the Cochrane Collaboration, National Institutes of Health, World Health Organization (WHO) and, obviously, KDIGO.

FIGURE 2.

Schematic representation of evidence-based practice/medicine (adapted from references [29, 30]).

Table 1.

| Implications | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| GRADE a | Patients | Clinicians | Policy |

| Level 1 ‘We recommend’ | Most people in your situation would want the recommended course of action, and only a small proportion would not | Most patients should receive the recommended course of action | The recommendation can be evaluated as a candidate for developing a policy or a performance measure |

| Level 2 ‘We suggest’ | The majority of people in your situation would want the recommended course of action, but many would not | Different choices will be appropriate for different patients. Each patient needs helps to arrive at a management decision consistent with her or his values and preferences | The recommendation is likely to require substantial debate and involvement of stakeholders before policy can be determined |

|

| |||

| GRADE | Quality of evidence | Meaning | |

|

| |||

| A | High | We are confident that the true effect lies close to the estimate of the effect | |

| B | Moderate | The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different | |

| C | Low | The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect | |

| D | Very low | The estimate of the effect is very uncertain, and often will be far from the truth | |

The additional category ‘not graded’ is typically used to provide guidance based on common sense or when the topic does not allow adequate application of evidence. The ungraded recommendations are generally written as simple declarative statements, but are not meant to be interpreted as being stronger recommendations than level 1 or 2 recommendations. Within each recommendation the strength of recommendation is indicated as Levels 1,2, or ‘not graded’, and the quality of the supporting evidence is shown as A,B,C or D.

KDIGO CKD–MBD GUIDELINES

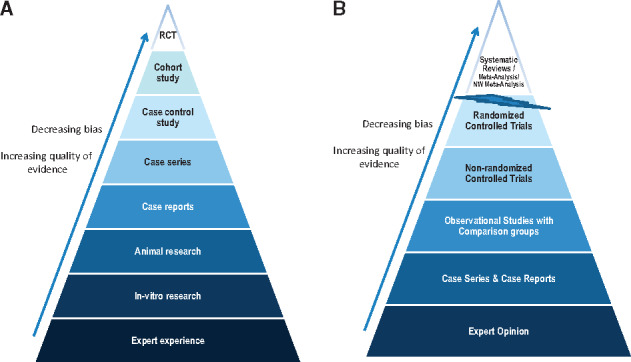

KDIGO CKD–MBD guidelines (from both 2009 and 2017) represent the most important academic work on the subject to date (and a major effort in terms of precise use of grammar!), but given their worldwide potential implications for health authorities, and also their political, economic and even legal consequences, it was rather disappointing to see a lack of strong clinical evidence in almost all areas. This definitely highlights the need for rigorous RCTs in this field (as well as others) and for most of us offers a lesson in the need for humility. Humans are ‘informavores’ [36], and in an era in which we have moved from ignorance to infoxication [37, 38], an increasingly sophisticated hierarchy of evidence and systematic summaries of the best evidence to guide care are of the utmost importance (Figure 3). However, in the case of CKD–MBD (and most areas of nephrology), the level of evidence is poor or extremely poor; nevertheless, we are required to act [42–44].

FIGURE 3.

Traditional (A) and new (B) evidence-based medicine hierarchies of evidence (adapted from references [15, 39–41]). Note that systematic reviews are ‘chopped-off’ from the pyramid since a meta-analysis of well-conducted RCTs at low risk of bias cannot be equated with a meta-analysis of observational studies at higher risk of bias [41]. Some recent reports suggest that lines separating the study designs should be wavy instead of straight [41]. NW, Network.

Not many things really changed in 2017 [11–13, 45]. The new guidelines are mostly graded as suggestions (Level 2) or are ‘not graded’ at all. Moreover, the quality of supporting evidence is mainly low (Grade C). Thus, among all current [‘old’ 2009 (no update needed) and ‘new’ (updated 2017)] recommendations for ‘adults’, only one (old) is graded as Level 1 A evidence (Guideline 4.3.1), namely the ‘recommendation’ that patients with CKD Stages 1 and 2 with osteoporosis and/or high risk of fracture, as identified by WHO criteria, should be managed as for the general population. Two guidelines (old) are graded as 1B: one recommends that clinical laboratories should inform clinicians of the actual assay method in use and report any changes in methods, sample source and handling specifications (Guideline 3.1.6) and the other recommends measuring serum calcium and phosphate at least weekly, until stable, during the immediate post-kidney transplant period (Guideline 5.1). Three more revisited guidelines (old) are graded as 1C and recommend: (i) monitoring serum levels of calcium, phosphate, PTH and alkaline phosphatase activity, beginning in CKD Stage 3A; (ii) basing therapeutic decisions on ‘trends’ rather than a single laboratory value; and (iii) avoiding the long-term use of aluminium-containing phosphate binders and dialysate aluminium contamination (Guidelines 3.1.1, 3.1.4 and 4.1.7, respectively). An additional guideline (old) is graded 2A (3.3.2) and ‘suggests’ that patients with known vascular or valvular calcification should be considered at the highest vascular risk. Six others [two old and (at last!) four new] are graded as 2B: Guidelines 3.2.1, 3.2.3, 4.1.6, 4.2.4, 4.2.5 and 4.3.2. These relate to (i and ii) bone mineral density (BMD) testing to assess fracture risk and suggested circumstances to treat CKD patients with CKD Stages 3A and 3B; (iii) measurements of PTH and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase to evaluate bone disease (predictors of bone turnover); (iv) the use of calcimimetics, calcitriol or vitamin D analogues (or combinations thereof) in dialysis patients requiring PTH-lowering therapy (written in alphabetical order); (v) parathyroidectomy for those who fail to respond to medical treatment; and (vi) restriction of the dose of calcium-based phosphate binders in adult patients receiving phosphate-lowering treatment (importantly, the evidence grade for this statement has increased from 2C to 2B since the 2009 guidelines). It should be underlined that the 2009 KDIGO guidelines recommended that the dose of calcium-based phosphate binders be restricted in the presence of persistent or recurrent hypercalcaemia (1B) and/or adynamic bone disease (2C) and/or persistently low serum PTH levels (2C), as well as in the presence of arterial calcification (2C). Actually, the last remark represented a step forward since the earlier 2003 National Kidney Foundation Kidney Disease Outcomes QUality Initiative (NKF KDOQI) guidelines stated that non-calcium-containing phosphate binders were preferred in dialysis patients with ‘SEVERE’ vascular and/or other soft tissue calcifications [33]. The evidence grade for use of a dialysate calcium concentration between 1.25 and 1.50 mmol/L (2.5 and 3.0 mEq/L) (Guideline 4.1.4) was also upgraded (to 2C from 2D) [2, 11].

The new guidelines included a very important change of paradigm in respect of BMD testing. In 2009, it had been suggested that, in patients with CKD Stages 3–5D, BMD testing should ‘NOT’ be performed routinely because BMD does ‘NOT’ predict fracture risk as it does in the general population, and BMD does NOT predict the type of renal osteodystrophy (2B). However, new evidence from several RCTs now suggests that in such patients, BMD testing SHOULD BE performed to assess fracture risk ‘if’ results will impact clinical decisions (Guideline 3.2.1; evidence again graded as 2B despite the very significant change). This guideline is related to Guideline 4.3.2, which suggests treatment as for the general population in patients with CKD Stages 3A and 3B with PTH in the ‘normal’ range and osteoporosis and/or high risk of fracture as identified by WHO criteria (2B). Consequently, there is currently an important debate over the extent to which these changes represent an important diagnostic and therapeutic challenge for nephrologists (in the absence of clear-cut treatment evidence) [46, 47], additionally considering that the inability to perform a bone biopsy may not justify withholding antiresorptive therapy from patients at high risk of fracture [11, 48]. This new guideline also begs many questions with respect to implementation. For example, what exactly are ‘risk factors for osteoporosis’ in CKD patients when CKD itself, among others, is clearly such a risk? What is the accuracy of the diagnosis of the underlying bone phenotype? What is the ‘normal’ range for serum PTH in CKD patients? [12].

It is also worth mentioning that statements in the chapters devoted to the treatment of CKD–MBD, targeted at lowering high serum phosphate levels and maintaining serum calcium, and the treatment of abnormal PTH levels, are mostly graded as 2C or not graded, with the ‘obvious’ clear exceptions mentioned above. Optimal PTH goals in the non-dialysis CKD setting are not known; therefore, beyond the avoidance of hypercalcaemia (Guideline 4.1.3; evidence upgraded to 2C from 2D), the lowering of elevated phosphate levels ‘towards’ the normal range now in all CKD stages (2C) and the avoidance of ‘preventive’ phosphate-lowering treatment, the guidelines only suggest that, in dialysis patients, intact serum PTH levels should be maintained in the range of approximately two to nine times the upper normal limit for the assay (2C), and that marked and consistent changes in PTH in either direction even within this range should prompt initiation of or change in therapy to avoid progression to values outside of this range (2C) (the so-called extremes of risk). While the implementation of the guidelines is not an easy task and misinterpretations or shortcuts are possible [leading to over- or under-diagnosis and over- or under-treatments (‘therapeutic nihilism’)], it has been documented that mean serum PTH levels have increased in most countries since the 2009 KDIGO publication [49].

A further suggestion in the guidelines is that calcitriol and vitamin D analogues should NOT BE routinely used in adult patients with CKD Stages 3A–5 who are not on dialysis (2C). This suggestion is based on the results of the Paricalcitol Capsule Benefits in Renal Failure-Induced Cardiac Morbidity (PRIMO) and Effect of paricalcitol on left ventricular mass and function in CKD (OPERA) studies and some meta-analyses that included studies performed at a time when a certain degree of hypercalcaemia was considered useful, in accordance with the previously available drug armamentarium. The PRIMO and OPERA studies were negative regarding the primary endpoint (reduction of left ventricular hypertrophy but NOT the control of secondary hyperparathyroidism). Thus, these patients were treated with relatively very high doses of paricalcitol, especially taking into account the fact that most patients had only minor or mild elevations of PTH levels [50, 51]. However, somewhat surprisingly, in the new guidelines, it is considered reasonable to reserve the use of calcitriol and vitamin D analogues for patients with CKD Stages 4 and 5 who have ‘severe’ and progressive hyperparathyroidism. Although this statement is ‘not graded’, vitamin D is a classic ‘preventive’ and therapeutic manoeuvre that we have been employing (even enforcing!) for many years [32, 33]. This new guideline calls attention to the suggestion that a ‘passive’ attitude (with non-native forms of vitamin D) should be adopted until ‘something’ becomes sufficiently ‘severe’ to warrant the initiation of treatment. Moreover, the perception of ‘severity’ remains at the discretion of the practitioner despite active surveillance. Of note, it is still unknown what the optimal serum PTH level is in these patients. A different reasonable approach is suggested by some (J. V. Torregrosa et al., submitted for publication in the Spanish Society of Nephrology journal “Nefrologia”) to avoid an induced and probably inadequate normalization of serum PTH levels in these patients without the need for passive ‘waiting’ until something becomes sufficiently ‘severe’ to consider treatment. Actually, some degree of secondary hyperparathyroidism may be beneficial in CKD patients (PTH is a phosphaturic hormone and is necessary for a normal bone formation rate) due to the presence of PTH hyporesponsiveness (PTH resistance) in CKD [52, 53]. Whether these 2017 KDIGO changes will result in a greater number of patients reaching later PTH extremes of risk or real improvement in patient-level outcomes remains to be seen.

The rationale for all these KDIGO-suggested interventions is based, with very few exceptions, on our evolving understanding of the complex CKD–MBD pathophysiology, the assumed biological plausibility for a treatment effect, epidemiological studies and other considerations [45]. We are used to achieving a desired target value for an ion or hormone mainly on the basis of retrospective studies; however, it is becoming clear not only that the achievement of these artificial goals is difficult [54, 55] (there are many interactions among biomarkers and among treatments), but also that the evidence base for them is of limited value—since, as mentioned before, most are graded as 2C. This is so even if in some studies (mainly retrospective, post hoc or using predefined but nominally significant ‘secondary’ outcomes) it seems that the mortality rates are reduced by the achievement of certain targets or the use of certain drugs [56–61]. Therefore, the benefit of achieving the difficult KDOQI or the more recent KDIGO targets [54, 55], in terms of improvements in hard outcomes or survival, remains to be confirmed in long-term prospective RCTs [54]. As nicely stated by Drs Chen and Bushinsky, it would be desirable for us, ‘as a nephrology community’, to ‘focus our investigative efforts on testing hypotheses in RCTs with clinically important endpoints such as CKD progression, cardiovascular events, fractures or mortality, which will enable stronger recommendations to be made in the next revision of the KDIGO CKD–MBD guidelines’ [45].

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Very significant gaps remain in our knowledge and there is a danger that the consequences of a ‘misunderstood’ EBM will be ‘therapeutic nihilism’, especially under financial pressure. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence (argumentum ad ignorantiam) [62]. While clinical experience and expert opinion can, of course, be criticized and must be analysed, we greatly believe that their significance cannot be completely dismissed [63]. For instance, in the absence of clear evidence in some areas (such as antithrombotic therapy in end-stage renal disease), expert opinion is still very welcome so that nephrologists are not left alone when facing difficult and sometimes risky clinical and therapeutic decisions for which supporting evidence is lacking [44]. All these ethical/philosophical/practical dilemmas actually extend to most areas within general nephrology (Table 2), causing nephrologists to struggle to choose between passivity (adopting a ‘wait and see’ approach and deciding to act only when Level 1 evidence becomes available) and an exceedingly proactive attitude based on long-lasting ‘beliefs’ that sometimes are not confirmed [66, 67]. For many reasons, including the frequent loss of patients (e.g. due to renal transplantation) and the complex nature of uraemia and dialysis, RCTs in nephrology are and probably will remain extremely scarce [60, 61]. A variety of additional problems have been described with respect to the guidelines and/or EBM [15], including delays in updating new relevant evidence when it becomes available (Table 3). ‘Living’ systematic reviews and ‘living’ guideline recommendations [68, 69] may help solving this last problem. However, unawareness or infoxication, difficulty in the achievement of goals, limited adherence, disbelief in current recommendations, sometimes induced by continuously changing recommendations or significant differences among different societies that are more or less conservative, misinterpretation by non-experts and ‘shortcutting’ have been described as additional difficulties in guidelines [37, 44, 54, 55, 70–73]. In any case, the methodical analysis of one’s own decision-making is mandatory. While ‘precision medicine’ in nephrology is still far away [74] and big data will transform our clinical decision-making [75] (some consider that the role of the physician will be enhanced, not diminished, as evidence and data grow) [76], the main ethical principles (Table 4) [77] should be seriously taken into account. In this context, we believe that both ‘individualization’ of treatments (applying the principles of non-maleficence and beneficence) and, especially, ‘shared’ decision-making (respecting the patient’s autonomy and social justice) should help in resolving difficult dilemmas between ‘treating’ or ‘waiting’ in any particular situation.

Table 2.

Summary of evidence grades in the 2012 KDIGO glomerulonephritis and 2009 transplant recipient guideline statements compared with the 2017 CKD–MBD guidelines [ 64, 65]

| Evidence grades | Statements (glomerular), n (%) | Statements (transplant), n (%) | Statements (CKD–MBD), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1A | 6 (3.1) | 3 (1.2) | 1 (2.2) |

| 1B | 22 (11.5) | 15 (6.2) | 2 (4.3) |

| 1C | 17 (8.9) | 18 (7.5) | 3 (6.5) |

| 1D | 0 | 15 (6.2) | 0 |

| Total GRADE 1 (recommendations) | 45 (23.5) | 51 (21.1) | 6 (13) |

| 2A | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 1 (2.2) |

| 2B | 10 (5.2) | 11 (4.6) | 6 (13) |

| 2C | 51 (26.6) | 59 (24.5) | 17 (37) |

| 2D | 60 (31.3) | 76 (31.5) | 4 (8.7) |

| Total GRADE 2 (suggestions) | 121 (63.1) | 147 (61) | 28 (60.9) |

| Not graded | 26 (13.5) | 43 (17.8) | 12 (26.1) |

| Total number of statements | 192 (100) | 241 (100) | 46 (100) |

Note that the number of statements in CKD–MBD guidelines is (obviously) lower as is the percentage of Grade 1 evidence statements, whereas ‘not graded’ evidence is more frequent. Regarding the percentage of Grade 2 evidence statements (similar percentage in all guidelines and more frequent than Grade 1), CKD–MBD guidelines include a higher percentage of 2A–2C statements versus 2D statements (which are more frequent in the other guidelines).

Table 3.

Summary of contributions (pros) and criticisms (cons) of Evidence Based Medicine (discussed in references [15, 68, 69])

| Pros: contributions | Cons: criticisms |

|---|---|

|

|

Table 4.

Main ethical principles (adapted from reference [77])

| Principle | Definition |

|---|---|

| Non-maleficence | Duty to avoid causing harm and to minimize harm to the patient |

| Respect for autonomy | Duty to respect a patient’s right of self-governance |

| Beneficence | Duty to maximize benefits and to enhance the patient’s well-being |

| Justice | Duty to treat patients fairly and equitably |

We should all ‘go to the balcony’ and recognize that, from that wider perspective, guidelines assist in the provision of recommendations at the individual personalized (shared!) patient-level, where straightforward ethical principles may be of valuable help (Table 4). As a matter of fact, the most significant change in the current update is a move towards a more articulated pragmatic and personalized approach to management for each patient [12, 13]. The attached guideline expert research recommendations are also extremely valuable in enabling the detection of major flaws in current data. As Nicolaus Copernicus nicely put it ‘to know that we know what we know, and to know that we do not know what we do not know, that is true knowledge’. However, while the history of medicine has sometimes made fools of physicians [20–22], including those extreme advocates of EBM as very nicely reported in the systematic review of the parachute gravitational challenge [78], comparison of the current status of our CKD population with that in earlier decades clearly suggests that much progress has been made in all our fields (before and after EBM) and that the forward momentum will be maintained by following the best available evidence.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

J.B. belongs to the Spanish ‘Red Nacional RedinRen’ (RD06/0016/0001 and RD12/0021/0033) and the ‘Red de Biobancos Nacional Española’ (RD09/0076/00064), as well as to the Catalan ‘Grupo Catalán de Investigación’ (AGAUR, Agència de Gestió d'Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca) (2009 SGR-1116). Collaborations with the Fundación Renal Iñigo Alvarez de Toledo (FRIAT) have also been arranged. We also thank Mr Ricardo Pellejero for his priceless bibliographic assistance and Dr Sergi Sabaté, Dr Ana Vila, Dr Raul Alejandro Quiroga, Dr Verónica Coll and Dr Jackson Ochoa for their valuable contributions to this review.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

J.B. declares advisory, lecture fees, and/or travel funding from Amgen, Abbvie, Sanofi-Genzyme, Shire, Vifor-Fresenius-Pharma, and Sanifit. P.U.T. declares advisory, lecture fees and/or travel funding from Abbvie, Amgen, Astellas, Medici, Sanofi, Vifor-Pharma, Fresenius Medical Care, and Hemotech. I.dS. declares lecture and/or travel funding fees from Vifor-Fresenius-Pharma and Alexion. M.C. declares advisory, lecture fees and/or travel funding from Amgen, Abbvie, Sanofi-Genzyme, Shire, Vifor-Fresenius-Pharma, and Baxter.

REFERENCES

- 1. Moe S, Drüeke T, Cunningham J. et al. Definition, evaluation, and classification of renal osteodystrophy: a position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int 2006; 69: 1945–1953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl 2009; 113: S1–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cozzolino M, Ureña-Torres P, Vervloet MG. et al. Is chronic kidney disease-mineral bone disorder (CKD-MBD) really a syndrome? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2014; 29: 1815–1820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vervloet MG, Massy ZA, Brandenburg VM. et al. Bone: a new endocrine organ at the heart of chronic kidney disease and mineral and bone disorders. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014; 2: 427–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Covic A, Vervloet M, Massy ZA. et al. Bone and mineral disorders in chronic kidney disease: implications for cardiovascular health and ageing in the general population. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2018; 6: 319–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kidney Disease Initiative Global Outcomes. Methods for guideline development. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 2012; 2: 317–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Torregrosa JV, Bover J, Cannata Andía J. et al. Spanish Society of Nephrology recommendations for controlling mineral and bone disorder in chronic kidney disease patients (S.E.N.-M.B.D). Nefrologia 2011; 31 (Suppl 1): 3–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Uhlig K, Berns JS, Kestenbaum B. et al. KDOQI US commentary on the 2009 KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of CKD-mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Am J Kidney Dis 2010; 55: 773–799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Goldsmith DJ, Covic A, Fouque D. et al. Endorsement of the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Chronic Kidney Disease-Mineral and Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD) Guidelines: a European Renal Best Practice (ERBP) commentary statement. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010; 25: 3823–3831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ketteler M, Elder GJ, Evenepoel P. et al. Revisiting KDIGO clinical practice guideline on chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder: a commentary from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes controversies conference. Kidney Int 2015; 87: 502–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.KDIGO 2017 Clinical Practice Guideline Update for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, Prevention, and Treatment of Chronic Kidney Disease–Mineral and Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 2017; 7: 1–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Burton JO, Goldsmith DJ, Ruddock N. et al. Renal association commentary on the KDIGO (2017) clinical practice guideline update for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of CKD-MBD. BMC Nephrol 2018; 19: 240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pasquali M, Bellasi A, Cianciolo G. et al. A nome del GdS Elementi Traccia e Metabolismo Minerale della Società Italiana di Nefrologia. Update 2017 of the KDIGO guidelines on Chronic Kidney Disease-Mineral and Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD). What are the real changes? G Ital Nefrol 2018; 35: pii [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Isakova T, Nickolas TL, Denburg M. et al. KDOQI US Commentary on the 2017 KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline Update for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, Prevention, and Treatment of chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Am J Kidney Dis 2017; 70: 737–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Djulbegovic B, Guyatt GH.. Progress in evidence-based medicine: a quarter century on. Lancet 2017; 390: 415–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Guyatt GH. Evidence-based medicine. ACP J Club 1991; 114: A–16 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Szajewska H. Clinical practice guidelines: based on eminence or evidence? Ann Nutr Metab 2014; 64: 325–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pincus T, Tugwell P.. Shouldn't standard rheumatology clinical care be evidence-based rather than eminence-based, eloquence-based, or elegance-based? J Rheumatol 2007; 34: 1–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rettig RA, Jacobson PD, Farquhar CM. et al. False Hope: Bone Marrow Transplantation for Breast Cancer. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moore TJ. Deadly Medicine. New York, NY: Simon & Shuster, 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL. et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002; 288: 321–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Craig JC, Tong A, Strippoli GF.. New approaches to trials in glomerulonephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2017; 32: i1–i6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Palmer SC, McGregor DO, Macaskill P. et al. Meta-analysis: vitamin D compounds in chronic kidney disease. Ann Intern Med 2007; 147: 840–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Palmer SC, McGregor DO, Craig JC. et al. Vitamin D compounds for people with chronic kidney disease not requiring dialysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; 4: CD008175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Palmer SC, McGregor DO, Craig JC. et al. Vitamin D compounds for people with chronic kidney disease requiring dialysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; 4: CD005633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sekercioglu N, Thabane L, Díaz Martínez JP. et al. Comparative effectiveness of phosphate binders in patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0156891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Habbous S, Przech S, Acedillo R. et al. The efficacy and safety of sevelamer and lanthanum versus calcium-containing and iron-based binders in treating hyperphosphatemia in patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2017; 32: 111–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jamal SA, Vandermeer B, Raggi P. et al. Effect of calcium-based versus non-calcium-based phosphate binders on mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2013; 382: 1268–1277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schmillen H. What is Evidence-Based Practice and Evidence-Based Medicine https://libguides.library.ohio.edu/evidence (20 September 2019, date last accessed)

- 30. Sacket DL, Rosenberg WMC, Gray JAM. et al. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't. BMJ 1996; 312: 71–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA. et al. ; GRADE Working Group. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2004; 328: 1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cannata-Andia J, Passlick-Deejen J, Ritz E.. Management of the renal patient: experts’ recommendation and clinical algorithms on renal osteodystrophy and cardiovascular risk factors. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2000; 15: 39–57 [Google Scholar]

- 33. National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for bone metabolism and disease in chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 2003; 42 (Suppl 3): S1–201 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Upshur RE. Are all evidence-based practices alike? Problems in the ranking of evidence. CMAJ 2003; 169: 672–673 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schünemann HJ, Best D, Vist G. et al. ; GRADE Working Group. Letters, numbers, symbols and words: how to communicate grades of evidence and recommendations. CMAJ 2003; 169: 677–680 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pirolli P, Card S.. Information foraging. Psychol Rev 1999; 106: 643–675 [Google Scholar]

- 37. D Agostino M, Mejía FM, Martí M. et al. Infoxication in health. Health information overload on the Internet and the risk of important information becoming invisible. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2018; 41: e115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ortiz-Herbener F, Bover J, Gracia S. et al. Nefrología e Internet: del desconocimiento a la infoxicación. Dial Traspl 2004; 25: 203–214 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Guyatt GH, Sackett DL, Sinclair JC. et al. Users' guides to the medical literature. IX. A method for grading health care recommendations. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA 1995; 274: 1800–1804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Golden SH, Bass EB.. Validity of meta-analysis in diabetes: meta-analysis is an indispensable tool in evidence synthesis. Diabetes Care 2013; 36: 3368–3373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Murad MH, Asi N, Alsawas M. et al. New evidence pyramid. Evid Based Med 2016; 21: 125–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bover J, Ureña-Torres P, Lloret MJ. et al. Integral pharmacological management of bone mineral disorders in chronic kidney disease (part I): from treatment of phosphate imbalance to control of PTH and prevention of progression of cardiovascular calcification. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2016; 17: 1247–1258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bover J, Ureña-Torres P, Lloret MJ. et al. Integral pharmacological management of bone mineral disorders in chronic kidney disease (part II): from treatment of phosphate imbalance to control of PTH and prevention of progression of cardiovascular calcification. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2016; 17: 1363–1373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Burlacu A, Genovesi S, Ortiz A. et al. Pros and cons of antithrombotic therapy in end-stage kidney disease: a 2019 update. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2019; 34: 923–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chen W, Bushinsky DA.. Chronic kidney disease: KDIGO CKD-MBD guideline update: evolution in the face of uncertainty. Nat Rev Nephrol 2017; 13: 600–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wilson LM, Rebholz CM, Jirru E. et al. Benefits and harms of osteoporosis medications in patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2017; 166: 649–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bover J, Ureña-Torres P, Laiz Alonso AM. et al. Osteoporosis, bone mineral density and CKD-MBD (II): therapeutic implications. Nefrologia 2019; 39: 227–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Moe SM, Nickolas TL.. Fractures in patients with CKD: time for action. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016; 11: 1929–1931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tentori F, Wang M, Bieber BA. et al. Recent changes in therapeutic approaches and association with outcomes among patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism on chronic hemodialysis: the DOPPS study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2015; 10: 98–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Thadhani R, Appelbaum E, Pritchett Y. et al. Vitamin D therapy and cardiac structure and function in patients with chronic kidney disease: the PRIMO randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2012; 307: 674–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang AY, Fang F, Chan J. et al. Effect of paricalcitol on left ventricular mass and function in CKD–the OPERA trial. J Am Soc Nephrol 2014; 25: 175–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Evenepoel P, Bover J, Ureña Torres P. et al. Parathyroid hormone metabolism and signaling in health and chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2016; 90: 1184–1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bover J, Ureña P, Evenepoel P. et al. PTH receptors and skeletal resistance to PTH action In: Ureña P, Covic A (eds). Parathyroid Glands in CKD. Springer; (In press) [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cozzolino M. CKD-MBD KDIGO guidelines: how difficult is reaching the ‘target’? Clin Kidney J 2018; 11: 70–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Fernández E. Are the K/DOQI objectives for bone mineral alterations in stage 3-5 chronic kidney disease patients unreachable or inadequate? Nefrologia 2013; 33: 1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Block GA, Klassen PS, Lazarus JM. et al. Mineral metabolism, mortality, and morbidity in maintenance hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2004; 15: 2208–2218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Fernández-Martín JL, Martínez-Camblor P, Dionisi MP. et al. Improvement of mineral and bone metabolism markers is associated with better survival in haemodialysis patients: the COSMOS study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015; 30: 1542–1551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Danese MD, Halperin M, Lowe KA. et al. Refining the definition of clinically important mineral and bone disorder in hemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015; 30: 1336–1344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Teng M, Wolf M, Lowrie E. et al. Survival of patients undergoing hemodialysis with paricalcitol or calcitriol therapy. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 446–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Suki WN, Zabaneh R, Cangiano JL. et al. Effects of sevelamer and calcium-based phosphate binders on mortality in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 2007; 72: 1130–1137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Chertow GM, Block GA, Correa-Rotter R. et al. ; EVOLVE Trial Investigators. Effect of cinacalcet on cardiovascular disease in patients undergoing dialysis. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 2482–2494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Altman DG, Bland JM.. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. BMJ 1995; 311: 485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Yee J. Eminence-based medicine: the King is dead. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2012; 19: 1–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int Suppl 2012; 2: 139–274 [Google Scholar]

- 65. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for the Care of Kidney Transplant Recipients. Am J Transplant 2009; 9: S1–S157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lv J, Zhang H, Wong MG. et al. ; TESTING Study Group. Effect of oral methylprednisolone on clinical outcomes in patients with IgA nephropathy: the testing randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017; 318: 432–442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Fried LF, Emanuele N, Zhang JH. et al. ; VA NEPHRON-D Investigators. Combined angiotensin inhibition for the treatment of diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 1892–1903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Elliott JH, Turner T, Clavisi O. et al. Living systematic reviews: an emerging opportunity to narrow the evidence-practice gap. PLoS Med 2014; 11: e1001603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Akl EA, Meerpohl JJ, Elliott J. et al. ; on behalf of the Living Systematic Review Network. Living systematic reviews: 4. Living guideline recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol 2017; 91: 47–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Bover J, Górriz JL, Martín de Francisco AL. et al. ; Grupo de Estudio OSERCE de la Sociedad Española de Nefrología. [Unawareness of the K/DOQI guidelines for bone and mineral metabolism in predialysis chronic kidney disease: results of the OSERCE Spanish multicenter-study survey]. Nefrologia 2008; 28: 637–634 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Roetker NS, Peng Y, Ashfaq A. et al. Adherence to kidney disease: improving global outcomes mineral and bone guidelines for monitoring biochemical parameters. Am J Nephrol 2019; 49: 225–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Skolnik N. Reexamining recommendations for treatment of hypercholesterolemia in older adults. JAMA 2019; 321: 1249–1250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Dowell D, Haegerich T, Chou R.. No shortcuts to safer opioid prescribing. N Engl J Med 2019; 380: 2285–2287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hunter DJ, Longo DL.. The precision of evidence needed to practice “precision medicine”. N Engl J Med 2019; 380: 2472–2474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Harari YN. 21 Lessons for the 21st Century. Spiegel & Grau, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 76. Williams RD. Of Eminence-Based and Evidence-Based Medicine https://www.aao.org/eyenet/article/of-eminence-based-and-evidence-based-medicine (20 September 2019, date last accessed).

- 77. Jalaly J, Dineen K, Gronowski AM.. A 30-year-old patient who refuses to be drug tested. Clin Chem 2016; 62: 807–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Smith GCS, Pell JP.. Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2003; 327: 1459–1461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]