Campaign persuasion operates with notable consistency across political parties, message tone, and information environment.

Abstract

Evidence across social science indicates that average effects of persuasive messages are small. One commonly offered explanation for these small effects is heterogeneity: Persuasion may only work well in specific circumstances. To evaluate heterogeneity, we repeated an experiment weekly in real time using 2016 U.S. presidential election campaign advertisements. We tested 49 political advertisements in 59 unique experiments on 34,000 people. We investigate heterogeneous effects by sender (candidates or groups), receiver (subject partisanship), content (attack or promotional), and context (battleground versus non-battleground, primary versus general election, and early versus late). We find small average effects on candidate favorability and vote. These small effects, however, do not mask substantial heterogeneity even where theory from political science suggests that we should find it. During the primary and general election, in battleground states, for Democrats, Republicans, and Independents, effects are similarly small. Heterogeneity with large offsetting effects is not the source of small average effects.

INTRODUCTION

Efforts by one actor to influence the choices of others pervade the social world. Political campaigns aim to persuade voters, firms aim to persuade consumers, and public service groups and governments aim to persuade citizens. Because persuasion is attempted in so many settings, the conditions for effective persuasion have been studied by scholars across many fields. The resulting set of theories and evidence points in the same direction: Study by study, social scientists have reported that persuasive influence tends to be small on average but have theorized that those small average effects mask large differences in responsiveness.

While the details vary across disciplines, persuasion is thought to require a specific mix of message content and environmental context, along with a special match of features of the sender with features of the receiver. In other words, persuasion is presumed to be conditional on who says what to whom and when, and getting this recipe right is thought to be critical for changing minds.

Across fields, scholars have elaborated different elements of this mixture. Psychologists laid out an initial model of attitude change (1) and demonstrated how characteristics of people (2) and pathways of thought (3) affect acceptance of messages and, therefore, persuasion. Contemporary work in psychology has taken context seriously, suggesting that culture, habit, social networks, and the framing of messages affect the magnitude of persuasion (4, 5). In marketing and consumer research, persuasive success has been shown to increase with shared social or ethnic identities among senders and receivers (6) and to depend on receiver experience with promotional appeals (7) and sender level of expertise (8). Work in management science shows similar heterogeneity: Successful transfers of information within firms depend on the capacity of the recipient to absorb information, the ambiguity of the causal process at issue, and the personal relations between the speaker and the audience (9). In economics, the magnitude and effectiveness of persuasion are argued to vary with the preferences of the speaker and the prior beliefs of the audience (10).

In our discipline of political science, a large body of work focuses on how much campaigns affect voter preferences (11–21). Recent work has focused on the relatively small size of the persuasive effects of campaign advertisements and the rapid decay of these effects (22, 23). Persuasion is generally believed to vary by characteristics of the messages such as advertising content (17, 24, 25), identity of the sender (26, 27), differences across receivers like partisanship or knowledge about the topic at hand (28), and contextual factors, including whether competing information is present (28, 29).

Synthesizing results across fields into a coherent theory of heterogeneity in persuasive effects is frustrated by difficult-to-overcome challenges of research design. For example, to understand the relative importance of message content, context, sender, and receiver, we need a design that allows each of the features to vary independently while holding others constant at the same levels each time. Typically, experiments vary one feature and hold all others constant at an idiosyncratic level in a single setting. When subsequent experiments turn to investigate a different attribute, the other features of the experiment become fixed at their own idiosyncratic levels—most likely different levels than in previous experiments. Furthermore, owing to the decades that have been spent researching persuasion, not only do studies investigate different targets and types of persuasion while holding other factors constant at varying levels, they do so with different designs, instruments, and sampling methods. Aggregating results from this set of studies—executed in largely uncoordinated ways—is challenging. Adding to the difficulty of forming a coherent theory of heterogeneity is the fact that publication and career incentives reward evidence of difference more highly than evidence of similarity (30, 31). As a result, the empirical record may overemphasize findings of treatment effect heterogeneity.

We have designed a series of unique tests spanning 8 months in which the sample, design, instrument, and analysis are all held constant. We measure the effects of 49 unique presidential advertisements made by professional ad makers during the 2016 presidential election among large, nationally representative samples using randomized experiments (we tested some of the 49 unique advertisements in multiple weeks). This design allows us to examine possible differences in persuasion related to message, context, sender, and receiver.

The summary finding from our study is that, at least in hard-fought campaigns for the presidency, substantial heterogeneities in the size of treatment effects are not hiding behind small average effects. Attack and promotional advertisements appear to work similarly well. Effects are not substantially different depending on which campaign produced the advertisements or in what electoral context they were presented. Subjects living in different states or who hold different partisan attachments appear to respond to the advertisements by similar degrees.

While we do not claim absolute homogeneity in treatment effects, our estimates of heterogeneity are substantively small. We estimate an average treatment effect of presidential advertising on candidate favorability of 0.05 scale points on a five-point scale, with an SD across experiments of 0.07 scale points. On vote choice, the average effect is 0.7 percentage points with an SD of 2 points. Advertising effects do vary around small average effects, but the distribution of advertising effects in our experiments excludes large persuasive effects. These results suggest that scholars may want to revisit previous findings and re-evaluate whether current beliefs about heterogeneity in persuasion rest on heterogeneity of studies and designs rather than an essential conditionality of persuasion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Our experiments were fielded from March to November (Election Day) in 2016, covering the primary elections of both major American political parties and the general election. Each week for 29 (not always consecutive) weeks, a representative sample of Americans was divided at random into groups and assigned to watch campaign advertisements or a placebo advertisement before answering a short survey. This sample period strengthened our design because it covered both the primary election, when voters lacked information about candidates or strong partisan cues, and the general election, when information about the two major party candidates was more easily available.

Our subjects were recruited by YouGov, which furnished samples of exactly 1000 (or 2000, depending on the week) complete responses. Participants were part of YouGov’s ongoing survey research panel and were invited to this particular survey after agreeing to take surveys for YouGov generally. This process was approved by the University of California, Los Angeles Institutional Review Board (IRB#16-000691). Some subjects (42%, on average) started the survey but did not finish, which can cause bias away from our inferential target, the U.S. population average treatment effect. We rely on YouGov’s poststratification weights to address the problem that some kinds of people are more likely to finish the survey than others. A second source of bias is the possibility that our treatments caused subjects to stop taking the survey. Using information on the full set of respondents who began each survey, we find no evidence of differential attrition by treatment condition. Specifically, we conduct separate χ2 tests of the dependence between response and treatment assignment within each week of the study. Of the 29 tests, three return unadjusted P values that are statistically significant. When we adjust for multiple comparisons using the Holm or Benjamini-Hochberg corrections (32, 33), none of the tests remain significant. Although this analysis does not prove that the missingness is independent of assignment, we proceed under that assumption.

We chose treatment advertisements from the set of advertisements released each week during the 2016 campaign by candidates, parties, or groups. We picked advertisements to test on the basis of real-time ad-buy data from Kantar Media and news coverage of each week’s most important advertisements. See the Supplemental Materials for more information about the treatments, including transcripts, date of testing, and the advertisements themselves. In total, we tested 30 advertisements attacking Republican candidate Donald Trump, 11 attacking Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton, 8 promoting Clinton, and 3 promoting Trump. The remainder were promotional advertisements for other primary candidates fielded before the general election.

The design of each weekly experiment was consistent. During the primaries (14 March to 6 June), 1000 respondents were randomly assigned to one of four conditions: watch either one of two campaign advertisements, both, or neither. Subjects who saw neither treatment advertisement were shown a placebo advertisement for car insurance. Subjects who saw two advertisements sometimes saw pairs of advertisements with competing messages and sometimes saw advertisements with reinforcing messages. We also showed some advertisements in multiple weeks to estimate whether the effect of the same advertisement varies with changing context. In analyses reported in the Supplementary Materials, we find no significant differences in effectiveness over time: The same advertisement works approximately equally as well, regardless of when during the campaign we test it.

During the period surrounding the conventions before the traditional start of the general election campaign (20 June to 15 August), 2000 respondents were recruited every other week. These subjects could be assigned to control or one of the two video conditions, but we removed the “both” condition during this period. In the fall, we returned to 1000 respondents a week and re-introduced the “both” condition on 26 September. We used the Bernoulli random assignment to allocate subjects to treatment conditions with equal probabilities. We are confident that treatments were delivered as intended: Tiny fractions of the control groups claimed to have seen campaign advertisements (2 to 4%) compared with large majorities of the treatment groups (92 to 95%).

After watching the videos, subjects took a brief survey, the full text of which is available in the Supplementary Materials. Here, we focus on two main outcome variables: subjects’ favorability rating of the target candidates on a five-point scale and their general election vote intention. Favorability and vote intention can be thought of as two points along a spectrum of candidate evaluation running from more to less pliable. If advertisements are effective at all, they should move candidate favorability before choice (34). Vote choice (as measured by vote intention) is the more consequential political outcome but may be more difficult to change via persuasive appeal. Our design allows us to measure whether advertisements move one, the other, both, or neither of these outcomes.

We estimate treatment effects separately for each week’s experiment using ordinary least squares (OLS) and robust SEs. OLS is a consistent estimator of the average treatmen effect (ATE) under our design (35). To increase precision (36), we control for the following covariates measured before treatment: seven-point party identification, five-point ideological self-placement, voter registration status, gender, age, race, income, education, region, and a pretreatment question about whether the country was on the right track.

The treatment effects in any single 1000-person study are estimated with a fair amount of sampling variability, but pooling across weeks via random-effects meta-analysis allows us to sharpen the estimates considerably. Random-effects meta-analysis allows us to directly estimate the extent of heterogeneity with respect to features of the persuasive environment.

RESULTS

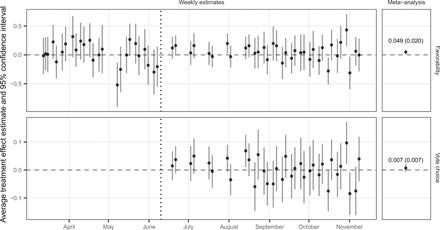

In Figure 1, we plot average treatment effect estimates (and 95% confidence intervals) for each of our 59 experimental comparisons for our two dependent variables. The top facet presents ATE estimates on candidate favorability, and the bottom facet presents ATE estimates on vote intention. The x axis represents calendar time to show when each experiment happened over the course of the campaign. Each point is one ATE estimated by OLS. To the right of each time series, we plot the meta-analytic estimate. On average, the advertisements moved target candidate favorability 0.049 scale points (1 to 5 scale) in the “correct” direction—the analysis is scaled such that the treatment effect of promotional advertisements is in the direction of favorability and that of attack advertisements is in the opposite direction. This estimate, though small, is statistically significant owing to the large size of our study. The effect on target candidate vote choice is also small at 0.7 percentage points, but is not statistically significant.

Fig. 1. Average treatment effect of advertising on candidate vote choice and favorability.

Figure 1 also provides a first indication of our main finding of low treatment effect heterogeneity. While ATE estimates vary from advertisement to advertisement, this variability is no greater than what would be expected from sampling variability. Using formal tests, we fail to reject the null of homogeneity in both cases (favorability, P = 0.09; vote choice, P = 0.07). As we discuss below, other statistical tests for large (nonsampling) variability generate similarly weak evidence.

We pause here to reflect on what Fig. 1 would mean if experimental results were subject to a statistical significance publication filter. Imagine that Fig. 1 represents the sampling distribution of persuasive treatment effects. If only statistically significant results were published, then we would be left with one large negative result (nearly −0.5 points on favorability in early May), one large positive result toward the end of the campaign in October (more than +0.5 points), and two other negative results in October. If the remaining experiments were not published, then one could imagine theorists hypothesizing that the effects depend on specific features of the content of these advertisements, the context of the campaign on these dates, or something about the senders and receivers in these experiments.

Our research design of repeated experiments provides context for these estimates. The main story of the graph is that treatment effects are similarly small over time, but sample sizes of 1000 or 2000 generate week-to-week sampling variability. Without multiple experiments, or much larger experiments, publication bias could lead to a distorted view of the heterogeneity in persuasive effectiveness, which, in turn, could lead to overfit theories of persuasion.

Conditionality of persuasive effects

We now more directly evaluate whether treatment effects are conditional on theoretically posited drivers of difference across message, context, sender, and receiver. In Table 1, we regress conditional average treatment estimates (conditioning on subject partisanship and battleground state residence) on a set of predictors of heterogeneity common to political science studies of campaigns. Altogether, we consider seven sources of heterogeneity, one feature of the receiver (respondent partisanship), three features of context (time to election day, whether the advertisement was aired during the primary or the general, and battleground state residency), and three features of message or sender [whether the advertisement was attack or promotional, if sponsored by a campaign versus an outside group Political Action Committee (PAC), and the target candidate].

Table 1. Meta-analysis of average treatment effects of advertisements on target candidate favorability and vote choice.

Observations are CATE estimates for each advertisement, conditional on subject partisanship and battleground residency. The signs of the outcomes are scaled with respect to the valence of the advertisement: Higher values indicate that promotional advertisements had positive effects on target candidate favorability or vote choice and that attack advertisements had negative effects. All meta-regressors have been demeaned so the intercept always refers to the estimate of the average treatment effect, but the coefficients still refer to the average difference in the effectiveness of the advertisement associated with a unit change in the regressor relative to the omitted category.

| Candidate favorability | Vote choice | |||

| Average effect | 0.056* | 0.062* | 0.007 | 0.008 |

| (0.020) | (0.020) | (0.007) | (0.007) | |

| Democratic respondent (versus Republican) |

0.035 | 0.022 | 0.011 | 0.006 |

| (0.035) | (0.036) | (0.010) | (0.011) | |

| Independent respondent (versus Republican) |

0.023 | 0.015 | 0.009 | 0.007 |

| (0.051) | (0.052) | (0.020) | (0.020) | |

| Battleground state (versus non-battleground) |

−0.00 | −0.007 | −0.017 | −0.017 |

| (0.033) | (0.033) | (0.010) | (0.010) | |

| PAC sponsor (versus campaign sponsor) |

−0.012 | 0.026 | −0.023 | −0.016 |

| (0.043) | (0.047) | (0.013) | (0.014) | |

| Time (scaled in months) | −0.023 | 0.005 | −0.009* | −0.008 |

| (0.014) | (0.010) | (0.004) | (0.004) | |

| Attack advertisement (versus promotional advertisement) |

−0.017 | 0.028 | ||

| (0.046) | (0.016) | |||

| General election (versus primary election) |

0.123 | |||

| (0.067) | ||||

| Pro-Trump advertisement (versus pro-Clinton advertisement) |

−0.124 | −0.016 | ||

| (0.101) | (0.034) | |||

| Anti-Clinton advertisement (versus pro-Clinton advertisement) |

−0.105 | 0.012 | ||

| (0.070) | (0.023) | |||

| Anti-Trump advertisement (versus pro-Clinton advertisement) |

−0.041 | 0.026 | ||

| (0.058) | (0.021) | |||

| Pro-Sanders advertisement (versus pro-Clinton advertisement) |

−0.075 | |||

| (0.089) | ||||

| Pro-Cruz advertisement (versus pro-Clinton advertisement) |

0.047 | |||

| (0.116) | ||||

| Pro-Kasich advertisement (versus pro-Clinton advertisement) |

−0.182 | |||

| (0.145) | ||||

| Number of observations | 354 | 354 | 204 | 204 |

*P < 0.05.

Turning first to features of receiver, we see that the differences in treatment response across Democrats, Independents, and Republicans are small, with SEs greater than coefficients. Independents do not appear to be more malleable than partisans, and neither partisan group is more responsive than the other. We consider below if partisanship of respondent interacts with partisanship of sender.

Of the three features of context, the slope with respect to the timing of the advertisement is negative in three of four specifications and statistically distinct from zero in one. The estimate in the third column suggests that effects do decline as the campaign progresses. Difference in effectiveness for subjects who do and do not live in battleground states is 0.008 scale points. On average, general election advertisements move candidate favorability by 0.121 scale points more than primary advertisements, although the estimate is not precise enough to achieve statistical significance. Even though this point estimate is large compared with the others in the table, it remains substantively small. The upper bound of the 95% confidence interval for the average difference between primary and general election advertisements is about 0.25 scale points on a five-point favorability scale. If there is heterogeneity by election phase, it is not of large political importance.

Characteristics of the advertisements themselves do not correlate strongly with estimated effects. We find that attack advertisements are about as effective in achieving their goals as promotional advertisements and that PAC- or SuperPAC-sponsored advertisements are no more effective than those sponsored by candidates. While pro-Clinton advertisements tended to be more effective than advertisements in support of or in opposition to other candidates, these differences cannot be distinguished from zero. Overall, there is little evidence that the magnitude of persuasion is conditional on the moderators that we evaluate motivated by political science theory.

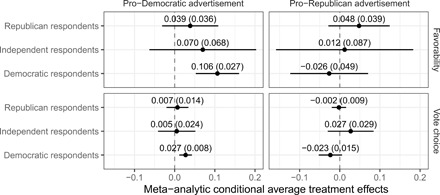

Table 1 estimates average differences in response by features of the subjects and the advertisements separately, but it is possible that effectiveness depends instead on the interaction of receiver and message, as argued by some existing theories of persuasion. For example, some theories posit that partisan respondents will view in-party messages more favorably than out-party messages, or more generally, that treatments need to “match” subjects on important dimensions to be effective. Figure 2 provides partial support for the “partisan match” theory: Democratic subjects respond more strongly to pro-Democratic advertisements than to pro-Republican advertisements. However, we do not observe a corresponding pattern among Republican respondents: Both pro-Democratic and pro-Republican advertisements have approximately the same small, positive, nonsignificant effect.

Fig. 2. Average effects of advertisements on favorability and vote choice, conditional on subject partisanship and advertisement target.

Table S2 presents formal tests of homogeneity of treatment effects across experiments and across subgroups. For the sample average treatment effects (SATEs) across experiments, P values from tests against the null of treatment effect homogeneity are 0.09 for favorability and 0.07 for vote choice. For the set of conditional average treatment effects (CATEs), P values are 0.0002 and 0.96.

While we fail to reject the null hypothesis of treatment effect homogeneity in three of four opportunities, we do not affirm that null. Instead, we rely on the direct measure of treatment effect heterogeneity provided by the random-effects estimator. The square root of the τ2 statistic is an estimate of the true SD of the treatment effects. We estimate this value to be 0.07 (SATEs) and 0.15 (CATEs) for favorability on a five-point scale and 0.02 and 0.02 for the vote choice. Since most estimates can be expected to fall within 2 SDs of the average, this analysis suggests small substantive effects even for the largest of CATEs. Across our many experiments that vary content, context, sender, and receiver, we find very little evidence that large persuasive effects occur even under a specific mix of features.

DISCUSSION

Across social science fields, a common pattern has emerged: Persuasive attempts tend to produce small average effects. Our 59 experiments demonstrate this. A persistent worry is that these small average effects mask large and offsetting conditional effects. Scholars from many traditions have forwarded theories to predict the circumstances under which such conditionality will obtain. Theories of heterogeneity have tended to outpace empirical demonstrations and confirmations of such heterogeneity due to basic constraints of research design. We need fine control over the many features presumed to cause heterogeneity, large sample sizes to measure small variations in response, and repeated experiments to confirm generality.

The present study is unusual in its size (34,000 nationally representative subjects) and breadth of treatments (a purposive sample of 49 of the highest-profile presidential advertisements fielded in the midst of the 2016 presidential election), allowing us to systematically investigate how variations in message, context, sender, or receiver condition persuasive effects—while holding all other tools of the research design constant.

We do not find strong evidence of heterogeneity. The magnitude of the effects of campaign advertisements on candidate favorability and vote choice does not appear to depend greatly on characteristics of the advertisement like tone, sponsor, or target; characteristics of the information environment such as timing throughout the election year or battleground state residency; or characteristics of actors such as partisanship.

Of course, we have not tested all potential sources of heterogeneity. There may well be a mix of message features and subject characteristics that generates politically important persuasion. We have not considered here some hypothesized moderators such as need for cognition, need for evaluation, need for cognitive closure, moral foundations, personality type, or interest in politics for the main reason that we allocated our budget to many shorter surveys rather than fewer longer surveys that could have measured these possible sources of variation in treatment response. However, even if we had measured these and found that they did not predict heterogeneity, we still would not affirm complete homogeneity because future scholarship could always discover as-yet unknown and unmeasured sources of variation. All that said, we have tested many of the key theoretical ideas from political science in the context of a presidential campaign and found little evidence of large differences.

Despite these small effects, campaign advertising may still play a large role in election outcomes. Our intervention delivers one additional ad in the heart of a marked presidential campaign that aired hundreds of thousands of such advertisements. This promotes external validity, but we are measuring the marginal effect of one additional advertisement. We do not measure the impact of an entire advertising campaign. If effectiveness were to increase linearly in advertisements viewed (or if the marginal returns diminished slowly enough), then these small effects could be highly consequential, consistent with the observed level of spending by candidates on advertising. Our data cannot speak to this question of scale, although the result in Table 1 that effects do not vary by battleground status (where people see many more advertisements than those who live in non-battleground states) suggests that marginal effectiveness may not depend on ambient levels of advertising.

How should scholars add our evidence to the science of political persuasion and to persuasion more generally? We suggest two conclusions. First, the marginal effect of advertising is small but detectable; thus, candidates and campaigns may not be wrong to allocate scarce resources to television advertising because, in a close election, these small effects could be the difference between winning and losing. Second, the expensive efforts to target or tailor advertisements to specific audiences require careful consideration. The evidence from our study shows that the effectiveness of advertisements does not vary greatly from person to person or from advertisement to advertisement.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank seminar audiences at Princeton University, NYU, the University of Michigan, the University of Texas, Vanderbilt University, Stanford University, and Columbia University—and particularly D. Green—for helpful feedback and engagement. Funding: We are grateful for financial support from the Andrew F. Carnegie Foundation and from J. G. Geer of Vanderbilt University. Shawn Patterson provided excellent research assistance throughout. J. Williams at YouGov helped make this project a success. A.C. acknowledges the support of the UCLA Marvin Hoffenberg Fellowship. The data collection and research presented in this manuscript was funded, in part, by The Andrew F. Carnegie Corporation as part of an Andrew F. Carnegie Fellowship in the Humanities and Social Sciences awarded to L.V. in 2015, and by UCLA’s Marvin Hoffenberg Chair in American Politics and Public Policy. Portions of the data collection were supported by J. G. Geer, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, Vanderbilt University. Author contributions: Funding for the project was secured by L.V. L.V. and S.J.H. designed the project. L.V. contracted, fielded, and executed the data collection and weekly experiments. A.C. performed data analyses and produced visualizations. All authors participated in writing and editing the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors. The replication archive for this study is available from the Harvard Dataverse (DOI https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/TN7KWR).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/36/eabc4046/DC1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.C. I. Hovland, I. L. Janis, H. H. Kelley, Communication and Persuasion (Yale Univ. Press, 1953). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fishbein M., Ajzen I., Attitudes and opinions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 23, 487–544 (1972). [Google Scholar]

- 3.R. E. Petty, J. T. Cacioppo, Communication and Persuasion: The Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion (Springer, 1986). [Google Scholar]

- 4.R. B. Cialdini, Influence: Science and Practice (Pearson, ed. 5, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tversky A., Kahneman D., Loss aversion in riskless choice: A reference-dependent model. Q. J. Econ. 106, 1039–1061 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deshpandé R., Stayman D. M., A tale of two cities: Distinctiveness theory and advertising effectiveness. J. Mark. Res. 31, 57–64 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friestad M., Wright P., The persuasion knowledge model: How people cope with persuasion attempts. J. Consum. Res. 21, 1–31 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson E. J., Sherrell D. L., Source effects in communication and persuasion research: A meta-analysis of effect size. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 21, 101–112 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Szulanski G., Exploring internal stickiness: Impediments to the transfer of best practice within the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 17, 27–43 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamenica E., Gentzkow M., Bayesian persuasion. Am. Econ. Rev. 101, 2590–2615 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahn K. F., Geer J., Creating impressions: An experimental investigation of political advertising on television. Polit. Behav. 16, 93–116 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- 12.T. M. Holbrook, Do Campaigns Matter? (Sage Publications, Inc., 1996). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finkel S. E., Geer J. G., A spot check: Casting doubt on the demobilizing effect of attack advertising. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 42, 573–595 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaw D. R., The effect of tv ads and candidate appearances on statewide presidential votes, 1988-96. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 93, 345–361 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 15.R. Johnston, M. G. Hagen, K. H. Jamieson, The 2000 Presidential Election and the Foundations of Party Politics (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- 16.D. R. Shaw, The Race to 270: The Electoral College and the Campagin Strategies of 2000 and 2004 (University of Chicago Press, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 17.L. Vavreck, The Message Matters: The Economy and Presidential Campaigns (Princeton Univ. Press, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franz M. M., Ridout T. N., Political advertising and persuasion in the 2004 and 2008 presidential elections. Am. Politics Res. 38, 303–329 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 19.J. Sides, L. Vavreck, The Gamble: Choice and Chance in the 2012 Presidential Election (Princeton Univ. Press, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Broockman D. E., Green D. P., Do online advertisements increase political candidates’ name recognition or favorability? Evidence from randomized field experiments. Polit. Behav. 36, 263–289 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 21.J. Sides, M. Tesler, L. Vavreck, Identity Crisis: The 2016 Presidential Election and the Battle for the Meaning of America (Princeton Univ. Press, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerber A. S., Gimpel J. S., Green D. P., Shaw D. R., How large and long-lasting are the persuasive effects of televised campaign ads? Results from a randomized field experiment. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 105, 135–150 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hill S. J., Lo J., Vavreck L., Zaller J., How quickly we forget: The duration of persuasion effects from mass communication. Polit. Commun. 30, 521–547 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 24.S. Ansolabehere, S. Iyengar, Going Negative: How Attack Ads Shrink and Polarize the Electorate (Free Press, 1995). [Google Scholar]

- 25.E. F. Fowler, M. M. Franz, T. N. Ridout, Political Advertising in the United States (Westview Press, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rahn W. M., The role of partisan stereotypes in information processing about political candidates. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 37, 472–496 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Broockman D., Kalla J., Durably reducing transphobia: A field experiment on door-to-door canvassing. Science 352, 220–224 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.J. Zaller, The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1992). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Druckman J. N., On the limits of framing: Who can frame? J. Polit. 63, 1041–1066 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Open Science Collaboration , Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science 349, aac4716 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gelman A., Loken E., The statistical crisis in science: Data-dependent analysis—a “garden of forking paths”—explains why many statistically significant comparisons don’t hold up. Am. Sci. 102, 460–465 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holm S., A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand. J. Stat. 6, 65–70 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y., Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. B. Methodol. 57, 289–300 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 34.D. R. Shaw, The Race to 270: The Electoral College and the Campaign Strategies of 2000 and 2004 (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin W., Agnostic notes on regression adjustments to experimental data: Reexamining Freedman’s critique. Ann. Appl. Stat. 7, 295–318 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 36.A. S. Gerber, D. P. Green, Field Experiments: Design, Analysis, and Interpretation (W.W. Norton, 2012).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/36/eabc4046/DC1